The Economist Guide To Financial Markets Why they exist and how they work Economist Guides 7th Edition

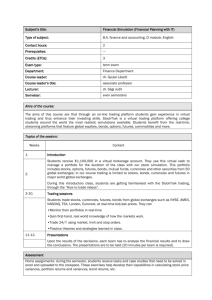

advertisement