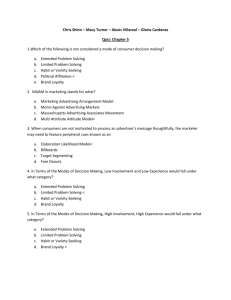

![[solomon] 11th edition Consumer Behaviour Book (1)](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/027427141_1-beb3160555ac01cb54c507f8629e106e-768x994.png)