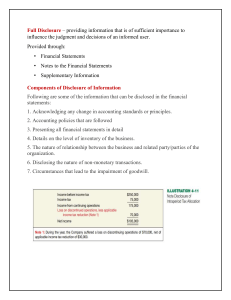

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/0967-5426.htm Future-oriented disclosure and corporate value: the role of an emerging economy corporate governance Kameleddine Benameur Gulf University for Science and Technology, Mishref, Kuwait Ahmed Hassanein Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait Received 4 January 2021 Revised 24 August 2021 4 February 2022 Accepted 20 February 2022 Gulf University for Science and Technology, Mishref, Kuwait and Accounting Department, Faculty of Commerce, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt Mohsen Ebied A.Y. Azzam Faculty of Commerce, Menoufia University, Shebin El-Kom, Egypt, and Hany Elzahar Arab Open University Kuwait Branch, Al-Farwaniya, Kuwait and Accounting Department, Faculty of Commerce, Damietta University, Damietta, Egypt Abstract Purpose – Kuwait has taken significant steps to reform its corporate governance (CG) by introducing the New Company Law (NCL) in 2013. This study investigates how this reform of CG mechanisms affects the disclosure of future-oriented information. Likewise, it explores how CG mechanisms affect the informativeness of this disclosure. Design/methodology/approach – The sample comprises the nonfinancial firms listed on the Boursa Kuwait from 2014 to 2018. The study uses an automated textual analysis to measure the level of future-oriented disclosure in the annual reports of these firms. The informativeness of disclosure is proxied by firm value at three months of the date of the annual report. Findings – The study finds that Kuwaiti firms with larger board sizes and substantial ownership by institutional investors are less likely to disseminate future-oriented information. Conversely, firms with more independent directors and larger audit committees are more inclined to provide future-oriented disclosure. Furthermore, the disclosure of future-oriented information carries contents that enhance investors’ valuations of Kuwaiti firms, especially in firms with fewer institutional ownership and more prominent audit committees. Research limitations/implications – It focuses on management decisions to disclose information in the annual reports. Examining other channels of disseminating information, such as social media disclosure, provides avenues for future research. Practical implications – Policy setters in Kuwait should consider the importance of some CG mechanisms to improve the transparency of Kuwaiti firms, as suggested by the NCL. Likewise, investors should rely on such specific CG mechanisms to build their prospects about the firm’s value. Originality/value – Apart from developed countries, the current study is the first evidence on how CG mechanisms could affect the informativeness of future-oriented disclosure in a developing economy. It is also the first to investigate the new CG mechanism introduced by Kuwait NCL in 2013. Keywords Future-oriented disclosure, Corporate governance, Corporate value, Automated textual analysis, Developing country, Gulf country, New Company Law, Kuwait Paper type Research paper The authors would like to thank the Research & Development Office at Gulf University for Science and Technology (GUST), Kuwait, for funding this research project. Journal of Applied Accounting Research © Emerald Publishing Limited 0967-5426 DOI 10.1108/JAAR-01-2021-0002 JAAR 1. Introduction Firms’ reporting requirements and practices evolve, and narrative disclosure has become a substantial part of the annual report. Narrative information provides textual analyses of a company through its board of directors (Merkley, 2014). Notably, it helps market participants to bridge the gap between financial information and the economic reality of a firm (Feldman et al., 2010). The International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) recommends that firms have a future orientation to their analysis and discussion in the narrative sections. It states that “management should include forward-looking information. Such information should focus on the extent to which the entity’s financial position, liquidity, and performance may change in the future. Management should provide forward-looking information through narrative explanations or through quantified data”. Such information helps investors and different market participants understand a firm and predict its future earnings (Hussainey et al., 2003; Muslu et al., 2015). Despite the usefulness of future-oriented information, firms may avoid disclosing it due to its sensitivity. Price Waterhouse Coopers states that “Many companies fear the increasing demand for forward-looking information will force them to disclose competitively-sensitive information, make profit forecasts or expose themselves to the threat of litigation”. Given that disclosing future-oriented information is at the discretion of corporate management, this role may lead to an information asymmetry issue that may adversely affect corporate resource allocations (Healy and Palepu, 2001). In response, corporate governance (henceforth, CG), through its monitoring role, can act as a mechanism to reduce information asymmetry and increase the relevance of information (Hassanein et al., 2019). The aim of the study is twofold. First, it investigates the extent to which the CG mechanisms affect the disclosure of future-oriented information in the annual reports of Kuwaiti firms. In particular, we investigate the effectiveness of the following observable mechanisms in the Kuwait New Company Law (NCL): the size of the board and its independence; the role duality of the CEO and chairman; existence of audit committee; together with the institutional ownership, which is the common form of ownership in Kuwaiti firms. Second, it explores the effect of CG mechanisms on the informativeness of disclosures of future-oriented information. Specifically, we explore how CG mechanisms affect the association between this disclosure and corporate values in Kuwait. This research is motivated by several considerations. First, most studies on futureoriented information focus heavily on developed countries (Hassanein et al., 2019; Li, 2010; Muslu et al., 2015; Hassanein and Hussainey, 2015). Nevertheless, there is relatively limited research on Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and none on Kuwait. Considering that each country has its specificities and there is no optimal CG model that fits all countries (Abdallah and Ismail, 2017), this induces the research on how CG affects the future-oriented disclosure in Kuwait. Second, unlike developed countries, there is no standardized format for the contents of the annual reports of Kuwaiti firms. Besides, the future-oriented disclosure in developing economies is more likely to be qualitative rather than quantitative forecasts. This lack gives flexibility to corporate managers about the contents of reporting. Consequently, significant variations exist between Kuwaiti firms about their practices of future-oriented disclosure. This may also create an information asymmetry issue leading to the inefficient allocation of firm resources (Buertey and Pae, 2021; Alazzani et al., 2017). The CG, in turn, helps to solve this issue and enhance the transparency level (Hassanein and Elsayed, 2021). Third, Boursa Kuwait has many differences from the major stock markets such as the US, the UK and the European Union such as its size, number of investors, number of listed firms, CG systems and ownership structures of firms. Kuwait’s degree of investor protection and capital markets are still at the early stages of development compared to developed economies (Alfraih and Almutawa, 2017). There is a concern about the transparency and accountability of Kuwaiti firms, and enhancing the corporate credibility of reporting in Kuwait is challenging (Dawd and Charfeddine, 2019). In sync with the New Kuwait 2035 strategic plan, this study is essential for Boursa Kuwait to assess the newly issued CG system’s effectiveness, a key feature sought after to attract investors to Kuwait. The study contributes to the literature by being the first Kuwait-based evidence on how CG mechanisms shape the disclosure of future-oriented information. It complements prior research in developed economies such as the UK (Hassanein et al., 2019; Hassanein and Hussainey, 2015) and the US (Li, 2010; Muslu et al., 2015). Our empirical results show that Kuwaiti firms with larger board sizes and more significant institutional ownership provide a low level of futureoriented information. Conversely, firms with more independent directors and larger audit committees are more inclined to disclose future-oriented information. These results provide implications for policy setters in Kuwait to consider the importance of some CG mechanisms to improve the transparency of Kuwaiti firms, as suggested in the NCL. Second, prior studies on the usefulness of future-oriented disclosure focus on developed countries such as the UK (Hassanein et al., 2019) and the US (Li, 2010; Muslu et al., 2015). Nevertheless, research on the informativeness of future-oriented disclosure in developing economies is scarce. This study enriches the existing literature by investigating this empirical issue in a developing economy (i.e. Kuwait). The results suggest that future-oriented disclosure of Kuwaiti firms with fewer institutional ownership or/and larger audit committees are likely to enhance the corporate values. These results are helpful for policymakers and investors and in developing economies in general and Kuwait in particular. Hence, Kuwaiti investors might be well-served to depend on such specific CG mechanisms (e.g. firms with less institutional ownership or/and larger audit committees) to develop their expectations about the firm’s value. The rest of the study is structured as follows. Section 2 is dedicated to the background about Kuwait context and develops the hypotheses. Section 3 details the research design to measure the disclosure of future-oriented information and empirical modeling. Section 4 outlines the sample and its descriptive statistics. Section 5 presents the empirical results. Section 6 presents further analyses. Section 7 provides concluding remarks. 2. Background and hypotheses 2.1 Corporate governance in Kuwait Kuwait, an oil-rich civil law country, has taken significant steps to reform its CG system, developed in 2009. In 2013, it introduced the New Companies Law (NCL), which is intended to strengthen CG principles to Kuwaiti-listed firms through a set of 11 rules. It was effectively applied in 2014. The NCL encourages Kuwaiti firms to provide full disclosure and more transparency (Rules #4 and 7). It also requires firms to increase the number of qualified board members (Rule #3) and recommends more non-executive and independent board members (Rule #1). Furthermore, it requires firms to avoid the practice where the same person is the chairman of the board and chief executive officer (Rule #2). Also, firms are required to form internal audit committees (Rule #5). In connection with the NCL, the Kuwait Capital Markets Authority (CMA) has issued a uniform CG framework for the firms it regulates. The CG mechanisms are in the early stages of adoption and implementation, and Kuwait has not developed many of them (Al-Shammari et al., 2008). For example, takeover policies are infinitesimal, few directors are non-Kuwaiti, and few firms have organized audit committees. Furthermore, Kuwaiti firms have low levels of disclosure despite complying with the rules and regulations, resulting in weak transparency and accountability. Based on the NCL rules, many studies (e.g. Al-Saidi and Al-Shammari, 2014; Al-Shammari and Al-Sultan, 2010; Al-Shammari et al., 2008) characterize the CG system in Kuwait as follows. First, the boards of directors include at least three directors appointed for a minimum of 3 years. The NCL requires firms to have at least five directors. The directors must be qualified and have no criminal record involving negligence, fraudulent bankruptcy, or breach of trust. They Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait JAAR should own shares at least worth no less than the equivalent of 23,000 US dollars. Second, the boards of directors are primarily family-controlled or dominated by large shareholders. However, the new CG rules recommend including non-executives and independent members on the corporate board. In most companies, a director acts as a CEO that reflects the issue of duality. For family-controlled listed firms, the formal is for the father to be the chairman and the son, or another family member, to be the CEO, or any similar combination. Most firms have nonexecutive directors and financial stakeholders represented on the board of directors. However, they do not have enough influence on board decisions. The shareholder ownership of Kuwaiti firms is concentrated in a few, which could be perceived as insider ownership and is most commonly institutional or governmental ownership. The ownership structure in Kuwait has many distinctive characteristics that are different from developed countries, such as the significant institutional ownership, the stability of the ownership structure in most Kuwaiti firms and the relatively small managerial ownership. 2.2 Theories, literature and hypotheses This subsection develops hypotheses based on the relation between the disclosure of futureoriented information and the following CG mechanisms: the board’s size and independence along with its CEO duality, institutional ownership and audit committee. We, then, develop the hypotheses about the influence of CG on the association between future-oriented information and corporate values. 2.2.1 Board size and future-oriented information. The quality of the board in the decisionmaking process is an inverse function of its size (Jensen and Meckling, 2012). This is because board size reduces the practical cooperation and communication among board members (Buertey and Pae, 2021; Hassanein and Kokel, 2019). In larger boards, some members do not criticize management decisions (Akhtar et al., 2018). At the same time, other studies find that a larger board has a diversity of experiences and subsequently has better quality monitoring that is more effective than smaller ones (Klein, 2002). The literature has mixed findings on how board size impacts voluntary disclosure. It finds positive (Wang and Hussainey, 2013), negative (Elgammal et al., 2018) and insignificant (Karamanou and Vafeas, 2005; Lakhal, 2005) associations between the two variables. The NCL recommends that the board of directors of Kuwaiti firms be at least three members allowing firms to select an appropriate size for their boards. Therefore, we may expect firms with larger boards to gain greater diversity of experiences that enhance the quality of their monitoring. Besides, the larger board is more representative of a broad group of stakeholders (Alfraih and Almutawa, 2017), affecting the disclosure policies. Subsequently, we predict a positive association between board size and future-oriented information. Nevertheless, we predict an inverse relationship for the following: First, CG in Kuwait is still in its early development stage, resulting in board members not capturing the importance of more disclosure and being satisfied with low levels of information. Second, since insiders dominate Kuwaiti corporate boards, they may be unwilling or less inclined to share information with outsiders. The literature consistently documents negative relation between board size and disclosure of voluntary information in Kuwait (Alfraih and Almutawa, 2017) and Qatar (Elgammal et al., 2018). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis: H1. Board size inversely influences the disclosure of future-oriented information in the annual reports of Kuwaiti firms. 2.2.2 Board independence and future-oriented information. The agency theory avers that independent directors take an active monitoring role than other board members, leading to more control over the opportunistic behavior of corporate managers (Jensen and Meckling, 2012). Subsequently, independent board members improve firm performance, decrease opportunism, lead to better quality earnings, and protect minority shareholders’ rights (Kim et al., 2007). Furthermore, they reduce the information asymmetry issue (Goh et al., 2016). Yuen et al. (2009) argue that independent directors balance corporate managers’ power and decrease the likelihood of information withholdings. Empirically, studies find significantly positive (Buertey and Pae, 2021), negative (Haniffa and Cooke, 2005) and insignificant (Hoitash et al., 2009) effects of board independence on voluntary disclosure. Similarly, some studies find mixed results for disclosing future-oriented information in the UK (Hussainey and Al-Najjar, 2011; Wang and Hussainey, 2013) and France (Lakhal, 2005). In Kuwait, the NCL is absent regarding the representative percent of independent directors on the board. However, we expect firms with more independent directors to be unwilling to support the management blindly. In turn, these firms would be willing to disclosure more future-oriented information. Moreover, if independent board members are the majority of the board, they may have enough clout and power to disclose future-oriented information. Thus, we test the following hypothesis: H2. Independent board members positively influence the disclosure of future-oriented information in the annual reports of Kuwaiti firms. 2.2.3 CEO duality and future-oriented information. The CEO duality is a situation leading to the dominance of the board of directors and management by one person. This situation harms the control of the board of directors. The CEO’s duality leads to the absence of separation of management and control decisions. As a result, this increases the opportunistic behavior of a firm CEO (Krause et al., 2014). Despite these points, CEO duality may have a positive side to it. The CEO should make relevant and timely decisions since they better know the firm, resulting in a strong leadership style. Notably, the Kuwait NCL advises firms to avoid the duality of the CEO. The literature argues that CEO duality may lead to less inclination to share corporate information with outsiders due to the desire for self-entrenchment (Brockmann et al., 2004). This literature indicates either a significantly negative (Lakhal, 2005; Wang and Hussainey, 2013) or an insignificant (Elgammal et al., 2018) nexus between the two variables. To the best of our knowledge, no study finds a positive association between CEO duality and voluntary disclosure. Because of these findings combined with the fact that a firm director in Kuwait acts as its CEO, we predict that CEO duality inversely affects the disclosure of future-oriented information in Kuwait. This prediction leads to the following hypothesis: H3. The CEO duality inversely influences the disclosure of future-oriented information in the annual reports of Kuwaiti firms. 2.2.4 Institutional investor ownership and future-oriented information. There are two opposing views in terms of institutional investors. Some studies find that they are active in monitoring management performance (Jensen and Meckling, 2012). They significantly influence corporate decisions and play a key role in CG by using their voting rights to steer the board of directors’ decisions or influence the general shareholders’ meetings (Buertey and Pae, 2021; Chung et al., 2019). Contrarily, some studies view them as myopic investors and are less likely to engage with their investee firms (Hassanein et al., 2021a). Empirically, the research finds no clear direction for the effect of institutional investors’ ownership on the disclosure of voluntary information. The US firms are likely to issue more management earnings forecasts when institutional investors own more significant shares (Karamanou and Vafeas, 2005). However, a negative association is found between institutional ownership and disclosing future-oriented information in the UK (Wang and Hussainey, 2013). In Kuwait, a large proportion of corporate ownership is controlled by institutional investors. Alfraih and Almutawa (2017) argue that Kuwaiti firms with significant family ownership are unwilling to disclose information voluntarily. They further Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait JAAR explain that these firms can communicate information directly with family members. Conversely, direct dissemination of future-oriented information with institutional investors is costly. Thus, disclosing future information in firm annual reports is an efficient way to share this information with various institutional investors. As a result, firms with more institutional investors ownership would be willing to provide future-oriented information in their annual reports. Thus, we test the following hypothesis: H4. Institutional investors ownership positively influences the disclosure of futureoriented information in the annual reports of Kuwaiti firms. 2.2.5 Audit committee and future-oriented information. The audit committee enhances the reliability of corporate reporting because it oversees the reporting process and monitors the firm’s internal controls (Klein, 2002). It is claimed that an influential audit committee consists of three to six members (Wallace and Zinkin, 2005). A smaller audit committee has limited knowledge and expertise that can result in ineffective monitoring and control of the activities of the agents (Cohen et al., 2014). However, a large audit committee has the advantage of accessing a larger pool of knowledge and expertise, which increases the quality of the monitoring process (Karamanou and Vafeas, 2005). Nevertheless, if the audit committee becomes too large, its effectiveness will likely be affected because its members may dilute their sense of responsibility, resulting in inadequate quality monitoring. The research finds that firms with a larger audit committee size provide more voluntary disclosure (Barako et al., 2006; Yuen et al., 2009; Al-Shammari and Al-Sultan, 2010). Notwithstanding, other studies find that it harms voluntary disclosure (Klein, 2002). In Kuwait, the CG system is characterized by a few audit committees. Thus, given the influence of larger audit committees, we predict that Kuwaiti firms with larger audit committees have more knowledge and expertise, which improves corporate reporting. Abad and Bravo (2018) reveal that US firms with knowledgeable audit committees disseminate future-oriented information. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated: H5. The size of audit committees positively influences the disclosure of future-oriented information in the annual reports of Kuwaiti firms. 2.2.6 Future-oriented information, corporate governance and firm value. Disclosure is likely to affect the investors’ views about firms which are reflected in their valuations (Hassanein, 2022). Future-oriented disclosure facilitates investors to develop prospects about corporate future cash flows that affect their valuation about it (Hassanein and Hussainey, 2015). Furthermore, it decreases the information asymmetry issue, as averred by the agency theory. As a result, as the uncertainty linked to a firm’s future performance lessens, the disclosure positively affects the share price, thus the firm’s value. The agency theory also views the CG mechanisms as effective means regulating the managers’ opportunistic behavior, hence mitigating the conflicts between corporate managers and investors (Jensen and Meckling, 2012). Consequently, firm value is more likely to be enhanced (Hassanein et al., 2019). Empirical research documents a positive influence of CG on the value of a firm (e.g. Bennouri et al., 2018). Literature reports a value relevance for the future-oriented disclosure. For instance, Kim and Shi (2011) reveal that cost of equity capital is decreased with the disclosure of management earnings forecasts by US firms. In addition, other studies find that disclosing this information helps expect earnings in the UK (Hussainey et al., 2003). Recently, Hassanein et al. (2019) found that UK firms with more future-oriented information are higher in their values. Moreover, their results show that future-oriented information is perceived as value relevant for big four clients and low-performance firms. Therefore, we expect future-oriented disclosure of Kuwaiti firms to have value relevance to Kuwaiti investors and affect their corporate valuations. Rare are the studies on the effect of CG on the value relevance of future-oriented information. The research findings indicate that UK firms with sound CG systems disclose future-oriented information containing relevant information for investors (Wang and Hussainey, 2013). Recently, Hassanein and Elsayed (2021) found that UK firms with sound CG systems provide informative risk information to their investors. Research on how CG could affect the value relevance of future-oriented information in Kuwaiti firms is absent. Hence, we fill this research gap by investigating how well-governed Kuwait firms’ future-oriented information affects their values. We expect disclosure of future-oriented information of well-governed firms to be informative about their values. Therefore, we develop the following: H6. The disclosure of future-oriented information by better-governed firms is more likely to enhance their values. 3. Research design 3.1 Measuring future-oriented information The computer-based content analysis technique is utilized to measure future-oriented information in the annual reports of Kuwaiti-listed firms. The research has used this technique (e.g. Hassanein, 2022; Hassanein et al., 2019; Hassanein and Hussainey, 2015; Li, 2010) since it helps code a large sample of reports that facilitate the generalization of the results and increases the reliability of the inferences made. Our study uses a sentence rather than a word as the unit of coding analysis as it results in a reliable, complete, and meaningful focus on a specific aspect of the data set (Hassanein, 2022). We follow Hassanein and Hussainey (2015) and use 33 future-related keywords, including “aim, anticipate, believe, coming, estimate, eventual, expect, following, forecast, forthcoming, future, hope, incoming, intend, intention, likely, look-ahead, look-forward, next, plan, predict, project, prospect, seek, shortly, soon, subsequent, unlikely, upcoming, well-placed, well-positioned, will, and yearahead.” Further, the QSR coding software package is used to develop a more restricted structure for the keywords. First, we use more complex forms for the keywords. For instance, instead of only searching for the word “expect,” the search includes: “expect,” “expects,” “is expecting,” “are expecting,” “is expected” and “are expected.” This approach reduces the likelihood of misinterpreting statements as future-oriented when they are not. Second, as per research (e.g. Muslu et al., 2015), adjectives, such as “next, coming, incoming, upcoming, forthcoming, following, and subsequent”, are linked with time indicators such as “fiscal, month(s), quarter(s), year(s), period(s), and six months or 12 months.” Third, we use verb conjugations to limit the possibility of capturing noun forms of the verbs mentioned earlier. For example, instead of searching for the word “plan,” we search for “we expect to plan” or/and “we are planning to.” Finally, numerical time references are added to the search; for example, 2018 or 2019 is added to the search of annual reports preceding that year (i.e. 2017). A random sample of five annual reports from each year is selected to evaluate the score’s reliability for future-oriented information. The scores for future-oriented information are calculated for the random sample manually by a research assistant and computerized through the QSR coding software package. The Pearson correlation assesses the correlation between manual and automated codings scores. The Pearson coefficient of 0.926 indicates that the scores are significantly correlated at a 0.01 level. Hence, the computer-generated score of future-oriented information is reliable. 3.2 Empirical modeling 3.2.1 Corporate governance’s effect on future-oriented information. We control for variables that may affect voluntary disclosure/future-oriented information. The literature shows either Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait JAAR no relation (Karamanou and Vafeas, 2005) or a positive relation (Menicucci, 2018; Lakhal, 2005) between firm size and voluntary disclosure. Besides, prior research reports in-significant (Barako et al., 2006), negative (Menicucci, 2018; Hoitash et al., 2009) or positive (Haniffa and Cooke, 2005) relation between firm profitability voluntary disclosure. In addition, previous studies find a positive relation between firm liquidity and voluntary disclosure (Mahboub, 2019). Furthermore, firm leverage has either a negative (Gul and Leung, 2004) or a positive (O’Sullivan et al., 2008) effect on future-oriented disclosure. Research also documents a positive relationship between firm dividends and future-oriented disclosure (Hussainey and Al-Najjar, 2011). The following Model is used to test H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5. Future DISit ¼ β0 þ β1 BSit þ β2 BIN %it þ β3 CEO Dulit þ β4 INST%it þ β5 AUDITit þ β6 FSizeit þ β7 FProfit þ β8 FLiqit þ β9 FLevit þ β10 FDivit þ Year FE þ Industry FE þ ε (1) The Future DISit is the dependent variable, representing the score of future-oriented information for firm i in year t measured as explained in Section 3.1. The independent variables comprise CG and control variables. The CG variables are the board size (BS), board independence (BIN%), CEO duality (CEO_Dul), institutional ownership (INST%) and audit committee size (AUDIT). The control variables are firm size (FSIZE), profitability level Variable Symbol Definition Future-oriented disclosure Future_DIS Firm value F_TQ The score of each Kuwaiti firm is the natural logarithm of the total frequency of future-oriented sentences in its annual report. Details of measuring the Future_ DIS is presented in Section 3.1 The Tobin’s Q ratio of Kuwaiti firm at three months after its annual report date The industry medium adjusted Tobin’s Q ratio, which is the Tobin’s Q ratio of the Kuwaiti firm after excluding the median Tobin’s Q of its industry in the observation year The market value of firm equity to its book value at three months after the annual report date The number of directors on of the firm at the end of each year The number of independent directors divided by the total number of directors in a firm board of directors Dummy variable with a value of 1 if the chairman and CEO is the same and 0 otherwise The number of outstanding shares owned by institutional investors divided by the total outstanding shares of a company at the end of each year The number of members in a firm audit committee at the end of each year The natural logarithm of a total firm asset at the end of each year The return on equity ratio of a firm at the end of each year The current ratio of a firm at the end of each year The ratio of a firm debt to its equity at the end of each year The dividend yield ratio of a firm at the end of each year The growth rate in revenue of a firm at the end of each year The ratio of firm capital expenditure to its assets at the end of each year IA_TQ MK-BV Table 1. Definitions of variables Board size Board independence BS BIN% CEO duality CEO_Dul Institutional investors’ ownership INST% Audit committee AUDIT Firm size Profitability Liquidity Leverage Dividend Growth rate Capital expenditure FSize FProf FLiq FLev FDiv FGrth FCapEx (FProf), liquidity (FLiq), leverage (FLev) and dividend (FDiv). Table 1 presents the measurements of all variables. 3.2.2 Future-oriented information, corporate governance and firm value. To assess how CG and disclosing future-oriented information separately and jointly affect firm value, we control for the variables affecting the value of a firm. Prior research findings indicate positive (Liu et al., 2012) and negative (Ammann et al., 2011) relations between the size of a firm and its value. In addition, research indicates a positive impact of firm profitability on its value (Hassan et al., 2009). Likewise, liquidity enhances firm value (Liu et al., 2012). Furthermore, firm leverage may impact the firm value negatively (Ammann et al., 2011). Moreover, research suggests that firm dividends enhance its value (Arnott and Asness, 2003). Similarly, the growth of a firm increases its value (Henry, 2008). We also control for capital expenditure as it may have either a positive (Weir et al., 2002) or a negative (Mangena et al., 2012) effect on firm value. To explore the effect of future-oriented information and CG mechanisms separately and jointly on firm value, we first develop Model (2) by regressing firm value on future-oriented information and control variables without considering the effect on CG mechanisms as follows: F TQit ¼β0 þ β1 Future DISit þ β2 FSizeit þ β3 FProfit þ β4 FLiqit þ β5 FLevit þ β6 FDivit þ β7 FGRTHit þ β8 CapExit þ Year FE þ Industry FE þ ε (2) The dependent variables in the F TQit representing the value of firm i at year t that is measured by as a natural logarithm of the ratio of Tobin’s Q at three months after the annual report release date. The independent variables are firm size (FSIZE), profitability level (FProf), liquidity (FLiq), leverage (FLev) and dividend (FDiv). Second, we develop Model (3) by adding the CG mechanisms to examine the effect of both future-oriented information and CG on the value of a firm, as follows: F TQit ¼ β0 þ β1 Future DISit þ β2 BSit þ β3 BIN %it þ β4 CEO Dulit þ β5 INST%it þ β6 AUDITit þ β7 FSizeit þ β8 FProfit þ β9 FLiqit þ β10 FLevit þ β11 FDivit þ β12 FGrthit þ β13 CapExit þ Year FE þ Industry FE þ ε (3) Third, we develop Model (4) to depict how the future-oriented information of a firm with good governance mechanisms can affect its value. Model (4) introduces interaction variables between CG mechanisms and future-oriented information. F TQit ¼ β0 þ β1 Future DISit þ β2 BSit þ β3 BIN %it þ β4 CEO Dulit þ β5 INST%it þ β6 AUDITit þ β7 BSit 3 Future DISit þ β8 BIN %it 3 Future DISit þ β9 CEO Dulit 3 Future DISit þ β10 INST%it 3 Future DISit þ β11 AUDITit 3 Ffuture DISit þ β12 FSizeit þ β13 FProfit þ β14 FLiqit þ β15 FLevit þ β16 FDivit þ β17 FGrthit þ β18 CapExit þ Year FE þ Industry FE þ ε (4) where BSit 3 FL DISit is the interaction variable between board size and future-oriented information; BIN %it 3 FL DISit is the interaction between board independence and futureoriented information; CEO Dulit 3 FL DISit is the interaction between CEO duality and future-oriented information; INST%it 3 FL DISit is the interaction between institutional Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait JAAR ownership and future-oriented information; AUDITit 3 FL DISit is the interaction between audit committee size and future-oriented information. The models’ parameters are estimated using an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression while controlling for year and industry fixed effects. The CG and future-oriented information variables are centralized before developing the interactional variables. The extreme values, above and below two standard deviations, have been eliminated from the analyses. 4. Sample and descriptive statistics The sample comprises the non-financial Kuwaiti firms listed on the Boursa Kuwait from 2014 through 2018. It starts in 2014 because the NCL is effective for annual reports for 2014 and ends with the most available annual reports. The primary sample consists of 870 firm-year observations (174 firms). We then exclude financial firms [1] (305 firm-year observations) from the analysis because of their unique regulations. Likewise, we exclude ten firm-year observations as their annual reports could not be converted into a text file that the QSR N6 coding software can read. We also exclude 21 observations due to missing CG and financial data. Hence, the final sample includes 534 observations. The corporate annual reports are downloaded from the official websites of the listed firms. The CG and financial data are collected from the Eikon DataStream. The descriptive statistics are shown in Table 2. The score of future-oriented information ranges from 4 [2.7182818^1.416] to 41 [2.7182818^3.724], with a mean value of 12 [2.7182818^2.485] statements. This range indicates a relatively low level of future-oriented disclosure of Kuwaiti-listed companies. This could be because the CG system in Kuwait is still in its early development and implementation stages, which do not fully capture the importance of disclosing information. The Table also shows that the average corporate value is 6.864, its minimum value is 8.543, and its maximum value is 47.876, indicating potentially significant variations in the corporate values of Kuwaiti firms. Table 2 also reveals that a corporate board’s average size is 8 (7.69), ranging from 4 to 14 directors. This is above the average board size as per the studies of the GCC (Alfraih and Almutawa, 2017) and indicates that firms are taking steps to increase their board sizes as suggested by the NCL. The mean value of independent directors is 31%, with values ranging from 0 to 47.5%. This is a strong indicator of the absence of independent board members in several listed Kuwaiti firms. In addition, Table 2 shows that 58% of the CEOs in the sampled Kuwaiti firms have dual roles. Although this percentage is relatively Table 2. Descriptive statistics Future_DIS F_TQ BS BIN% CEO_Dul INST% AUDIT FSize FProf FLiq FLev FDiv FGrth FCapEx Mean Standard deviation Minimum 25% Median 75% Maximum 2.485 6.864 7.69 0.314 0.58 0.361 2.642 6.937 30.479 2.440 69.228 2.901 8.244 0.046 0.863 3.284 2.414 0.965 0.705 0.704 0.873 0.576 12.413 1.238 31.905 1.723 2.159 0.043 1.416 8.543 4.00 0.00 0.000 0.000 1.000 5.594 10.730 0.210 44.470 0.000 12.620 0.000 1.492 2.3371 6.00 0.250 0.000 0.184 1.162 6.501 9.575 1.770 29.578 1.830 7.945 0.015 2.168 10.735 9.00 0.375 1.000 0.298 2.862 6.883 17.015 3.130 57.685 2.800 17.460 0.034 2.793 26.941 12.00 0.415 1.000 0.382 4.762 7.370 28.830 7.593 120.608 4.010 26.348 0.063 3.724 47.876 14.00 0.475 1.000 0.463 6.000 8.482 76.850 12.310 208.910 8.250 37.820 0.372 below that reported by Alfraih and Almutawa (2017), CEO duality is still common practice in Kuwaiti firms. Institutional investors own, on average, 36% of the outstanding shares of the Kuwaiti-listed firms. The average size of an audit committee is 3 (2.642) members, and it ranges from 1 to 6. Having an audit committee was optional before introducing the new CG in 2013, which prioritized the presence of audit committees from 2014 and onwards. Table 3 shows a significant correlation between the future-oriented information and some mechanisms of CG. The Future_DIS is positively associated with independent directors (BIN%) and the size of the audit committee (AUDIT). On the other hand, it is adversely correlated with a board size (BS) and institutional investors (INST%). Furthermore, the score is positively correlated with the firm value (F_TQ). This correlation conveys that firms disclosing more future-oriented information have higher values. Also, Future_DIS is significantly associated positively with the firm’s size (FSize), profitability (FProf), dividends (FDiv) and growth rate in sales (FGrth). However, it is adversely correlated with liquidity (FLiq). These results strengthen the validity of the Future_DIS measure, as indicated in the research (Brown and Tucker, 2011; Hassanein et al., 2019). Notably, the Pearson coefficients are below 0.80, suggesting an absence of multicollinearity issue (Gujarati and Porter, 2009). 5. Empirical results 5.1 Corporate governance’s effect on future-oriented information In Table 4, we present the results of Model (1). In panel [1], we show the results of regressing the future-oriented information on the control variables only without considering the effects of the CG mechanism. Panel [2] shows the results for the five CG mechanisms individually. Panel [3] shows the results by incorporating all mechanisms in one Model. The Model has a significance level of 1% (p < 0.01) in all panels. The adjusted R-squared value is 35% in Panel [1], and it ranges from 35.931% to 40.769 46% in Panel [2] based on the mechanism of CG. It becomes 46.429% when we add all CG mechanisms to one Model, as shown in Panel [3]. These results indicate a good fit for the Model in all panels that CG mechanisms explain variations in Kuwaiti listed firms’ level of future-oriented information. The coefficient for the CG mechanisms in Panel [2] varies from statistically insignificant (Bs & CEO_Dul) to significantly positive (BIN% & AUDIT) and to significantly negative (INST%). The variations in the results become even more pronounced when we add all mechanisms to one regression model, as shown in Panel [3]. We consider Panel [3] as our main results, as explained next. The coefficient for BS is 0.828 (t 5 1.738), meaning that firms with larger boards disclose low levels of future-oriented information, which supports H1. It confirms the view of the agency theory that larger boards lack effectiveness in decision-making (Jensen and Meckling, 2012). Moreover, it confirms the perception that insiders dominate corporate boards in Kuwait, and they are less willing to disclose information to outsiders. The result complements the research in Kuwait that finds that board size adversely affects the level of voluntary disclosure (Alfraih and Almutawa, 2017). Conversely, the coefficient for IND% is 1.359 (t 5 2.841), indicating that independent directors positively influence the disclosure of future-oriented information. The result supports H2. It supports the perspective that independent directors reduce the information asymmetry issue and subsequently enhance the levels of disclosure (Goh et al., 2016). It is consistent with the research findings of the UK (Hussainey and Al-Najjar, 2011; Wang and Hussainey, 2013) and France (Lakhal, 2005). However, the CEO_Dul does not have a statistically significant relation with Future_ Dis (β 5 0.091, t 5 0.663). Thus, we reject H3. This result does not align with the agency theory argument that having one person dominate the board of directors reduces its effective control Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) 1 0.406*** 1 (0.000) (3) BS 0.271** 0.062 1 (0.022) (0.359) (4) BIN% 0.143*** 0.189*** 0.281** 1 (0.003) (0.000) (0.037) (5) CEO_Dul 0.030 0.013 0.052 0.002 1 (0.543) (0.787) (0.268) (0.972) (6) INST% 0.198*** 0.098* 0.129*** 0.205*** 0.058 1 (0.000) (0.065) (0.005) (0.000) (0.214) (7) AUDIT 0.183** 0.140* 0.379*** 0.451*** 0.134*** 0.118* 1 (0.027) (0.073) (0.000) (0.000) (0.004) (0.051) (8) FSize 0.425*** 0.475** 0.517*** 0.583*** 0.053 0.216*** 0.304*** (0.000) (0.000) (0.000) (0.000) (0.261) (0.000) (0.000) 0.017 0.014 0.019 (9) FProf 0.275*** 0.103*** 0.038 0.004 (0.930) (0.726) (0.763) (0.692) (0.000) (0.005) (0.428) (10) FLiq 0.136*** 0.105** 0.192*** 0.178*** 0.021 0.006 0.158*** (0.005) (0.014) (0.000) (0.000) (0.655) (0.896) (0.001) (11) FLev 0.015 0.069 0.105* 0.042 0.022 0.035 0.034 (0.608) (0.138) (0.065) (0.375) (0.644) (0.456) (0.464) (12) FDiv 0.127** 0.102* 0.199** 0.233*** 0.084 0.053 0.137*** (0.037) (0.058) (0.038) (0.000) (0.085) (0.274) (0.005) 0.176*** 0.107* 0.068 0.074 (13) FGrth 0.021* 0.160*** 0.162*** (0.001) (0.000) (0.052) (0.144) (0.110) (0.069) (0.000) (14) FCapEx 0.063 0.137** 0.648* 0.293 0.220 0.292 0.640** (0.246) (0.019) (0.073) (0.355) (0.492) (0.357) (0.025) Note(s): *, **, *** means correlation between variables is significant at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively Table 3. Correlation analysis (1) Future_DIS (2) F_TQ (1) 0.026 (0.589) 0.141*** (0.002) 0.090 (0.054) 0.525*** (0.000) 0.091* (0.054) 0.409 (0.187) 1 (8) 0.034 (0.473) 0.049 (0.307) 0.010 (0.846) 0.066 (0.164) 0.414 (0.206) 1 (9) 0.063 (0.178) 0.383*** (0.000) 0.088* (0.063) 0.304 (0.337) 1 (10) 0.144*** (0.003) 0.011 (0.812) 0.377 (0.227) 1 (11) 0.008 (0.868) 0.401 (0.197) 1 (12) 0.424 (0.169) 1 (13) 1 (14) JAAR Coefficients (t-statistics) Coefficients (t-statistics) BS 0.157 (1.428) BIN% þ 1.548*** (3.236) CEO_Dul INST% þ AUDIT þ FSize þ 2.819*** (3.217) 3.138*** (5.137) 2.261*** (4.174) FProf þ/ 2.486*** (3.016) 1.473 (1.213) 2.832*** (3.435) FLiq þ/ 0.988 (0.505) 1.380 (0.738) 1.125 (0.475) FLev þ/ 0.726 (1.152) 1.014* (1.679) 0.827 (1.312) FDiv þ/ 1.583** (2.030) 2.251*** (2.836) 1.803** (2.312) Intercept 3.487*** (3.910) 4.871*** (5.462) 3.972*** (4.453) Year-FE Yes Yes Yes Industry-FE Yes Yes Yes F-test 6.375*** 8.916*** 7.261*** Adjusted R-Squared 34.751 36.147 39.581 Tolerance 0.528 0.538 0.501 Observation 534 534 534 Note(s): *, **, *** means coefficient is significant at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively Pred. Sign (1) Coefficients (t-statistics) 3.307*** (4.153) 1.916** (2.318) 1.159 (0.592) 0.852 (1.351) 1.257 (1.381) 4.093*** (4.586) Yes Yes 7.478*** 35.963 0.519 534 0.107 (0.778) (2) Coefficients (t-statistics) 3.174*** (4.182) 3.326*** (4.035) 1.322 (0.671) 0.971 (1.541) 2.164** (2.216) 4.618*** (5.232) Yes Yes 8.531*** 40.197 0.506 534 1.379*** (3.094) Coefficients (t-statistics) 1.147** (2.093) 2.628*** (3.843) 3.274*** (3.972) 1.301 (0.695) 0.956 (1.517) 2.085** (2.374) 4.592*** (5.149) Yes Yes 8.396*** 40.769 0.595 534 Coefficients (t-statistics) 0.828* (1.738) 1.359** (2.841) 0.091 (0.663) 1.031** (2.275) 1.618*** (3.485) 3.582*** (4.739) 2.083*** (3.451) 0.727 (0.336) 0.817 (0.916) 1.126** (2.281) 2.819*** (3.161) Yes Yes 7.291*** 46.429 0.573 534 (3) Coefficients (t-statistics) Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait Table 4. Impact of CG mechanisms on Future_ DIS JAAR (Jensen and Meckling, 2012). Furthermore, the INST% coefficient is 1.031 (t 5 2.275), indicating that firms with greater ownership by institutional investors are unwilling to disclose future-oriented information. Thus, we reject H4. The result supports institutional investors’ myopic and short-term views (Hassanein et al., 2021a). This short-term view induces firm managers in Kuwait to disclose less future-oriented information, particularly in higher institutional ownership. This result is different from prior studies in the UK, which find insignificant between the two variables (Wang and Hussainey, 2013). Finally, the coefficient for AUDIT is 1.618 (t 5 3.485), supporting the H5. The result is in sync with the proposition that a large audit committee is expected to have diversified knowledge and expertise, improving the quality of the monitoring process (Karamanou and Vafeas, 2005) and enhancing the disclosure of voluntary information (Barako et al., 2006). Regarding control variables, the results are consistent with the previous studies. Our results show that larger Kuwaiti firms disclose more future-oriented information, supporting previous research (Wang and Hussainey, 2013). Besides, firms with higher profitability disclose more future-oriented information, as evidenced in previous research (Haniffa and Cooke, 2005). Moreover, firm dividends positively affect the disclosure of future-oriented information, which supports the literature (Hussainey and Al-Najjar, 2011). Pred. Sign Table 5. Future_DIS, CG and firm value (1) Model [2] Coefficients (t-statistics) (2) Model [3] Coefficients (t-statistics) (3) Model [4] Coefficients (t-statistics) Future_DIS þ 1.349*** (2.741) 2.158*** (3.179) 1.537*** (2.619) BS þ 0.114 (1.105) 0.085 (0.972) BIN% þ 0.886** (2.049) 0.835** (2.014) CEO_Dul þ 0.058 (0.621) 0.042 (0.546) INST% þ 0.853** (2.091) 0.631** (1.974) AUDIT þ 1.431*** (2.674) 1.285*** (2.652) FL_DIS 3 BS þ 0.018 (1.039) FL_DIS 3 BIN% þ 0.014 (1.153) FL_DIS 3 CEO_Dul þ 0.010 (0.372) FL_DIS 3 INST% þ 0.096** (2.463) FL_DIS 3 AUDIT þ 0.138*** (2.738) FSize þ 2.315*** (3.948) 2.418*** (3.635) 2.357*** (3.497) FProf þ/ 1.937*** (3.198) 1.503*** (3.029) 1.815*** (3.104) FLiq þ/ 0.283 (0.437) 0.286 (0.264) 0.203 (0.232) 0.630** (2.318) 1.094*** (2.817) 0.793** (2.437) FLev þ/ FDiv þ/ 0.843** (2.610) 1.193*** (3.202) 0.865** (2.516) FGrth þ/ 1.109*** (3.198) 1.089* (1.657) 1.352*** (3.216) FCapEx þ/ 0.553 (1.231) 0.978 (1.362) 0.709 (1.198) Intercept 2.765*** (3.172) 3.184*** (3.914) 2.597*** (3.486) Year-FE Yes Yes Yes Industry-FE Yes Yes Yes F-test 13.385*** 14.518*** 12.738*** Adjusted R-Squared 23.641 26.513 28.639 Tolerance 0.539 0.513 0.486 Observation 534 534 534 Note(s): *, **, *** means coefficient is significant at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively 5.2 Future-oriented information, corporate governance and firm value Table 5 reports the estimation results for the associations between future-oriented information, CG mechanisms and firm value. Panel (1) presents the estimation of Model [2] in which we regress the Future_DIS on F_TQ without considering the effects of CG mechanisms, while Panel (2) shows the results from Model [3] in which we additionally consider the effects of CG mechanisms. Panel (3) reveals the results for Model [3], which includes the interaction variables between Future_DIS and CG mechanisms. The models are significant (p < 0.01). The R-squared is 23.641% in Panel (1), 26.513% in Panel (2) and 28.639% in Panel (3), which indicates a good overall fit for all models in explaining the variations in the values of Kuwaiti listed firms. The coefficient for Future_DIS is 1.349 (t 5 2.741) in Model [2] and is increased to 2.158 (t 5 3.179) after adding CG mechanisms to Model [3]. It then becomes 1.537 (t 5 2.619) after adding interaction variables in Model [4]. These values indicate that disclosures of futureoriented information increase the values of Kuwaiti firms. This is because future-oriented information alleviates information asymmetry and helps investors formulate views about the company’s future cash flows. As a result, the ambiguity linked to the company’s future performance is diminished, affecting the share price positively, thus the company’s value. It adds to UK research on future-oriented information and firm value (Hassanein et al., 2019; Hassanein and Hussainey, 2015). The effects of CG mechanisms on the firm value are shown in Models [3] and [4]. The results are qualitatively similar in both models. They show that board independence (BIN%) and the size of the audit committee (AUDIT) positively affect the value of a firm. However, they provide evidence that firm value is an inverse function of institutional investors’ ownership (INST%). On the other hand, their results indicate that both board size (BS) and CEO role duality (CEO_Dul) do not affect Kuwaiti firms’ value. The results go in the same line with empirical research documenting substantial effects of some CG on corporate values (e.g. Bennouri et al., 2018). Panel (3) presents Model [4] results, including the interaction variables between futureoriented information and CG mechanisms. It shows that the coefficients for Future_DIS 3 BS (β 5 0.018; t 5 1.039), FL_DIS 3 BIN% (β 5 0.014; t 5 1.153) and FL_DIS 3 CEO_Dul (β 5 0.010; t 5 0.372) are not statistically significant. These results reveal that the board’s size, independence, and CEO duality do not affect the positive association between futureoriented information and the values of Kuwaiti firms. On the other hand, the coefficient for FL_DIS 3 INST% is significant at the 5% level (β 5 0.096; t 5 2.463), which indicates institutional investors’ ownership decreases the positive relation between future-oriented information and firm value. This supports the myopic and short-term view of institutional investors in Kuwait. Moreover, the coefficient for FL_DIS 3 AUDIT is significant at the 1% level (β 5 0.138; t 5 2.738), indicating that the size of the audit committee increases the positive relation between future-oriented information and the value of Kuwaiti firms. This confirms that larger audit committees in Kuwait have the advantages of their members’ diversified knowledge and skillsets, which improve the quality of information. The results for H6 confirm the findings of the UK study by Wang and Hussainey (2013) in which the FL_DIS of well-governed firms contains value-relevant information for investors. 6. Additional analyses 6.1 Sensitivity analysis test Studies have argued that the value of a firm varies significantly over industries (Hassanein and Hussainey, 2015). In response, we calculate an industry medium adjusted Tobin’s Q (IA_TQ) as a proxy for firm value. This measure reduces the industry bias (Hassanein and Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait JAAR Hussainey, 2015). Table 1 details the calculation of IA_TQ. We, additionally, employed the ratio of market to book value of firm equity (MK-BV) as a proxy for firm value as per literature (Hassan et al., 2009). We re-estimate Model [4] using the IA_TQ and MK-BV as dependent variables. Table 6 shows that the Model is significant (p < 0.01), and the adjusted R-Squared values reveal that variations in the values of Kuwaiti firms can be explained by Model [4]. The loadings on the future-oriented information, CG mechanism, and interaction variables provide qualitatively similar results to that reported in the primary analyses, as shown in Table 5. 6.2 Endogeneity test The presence of endogeneity among variables reduces the validity of regression results, as indicated in the disclosure literature (e.g. Nikolaev and van Lent, 2005). It occurs for two reasons, omitted variable bias and simultaneity. It is suggested that the control variables and fixed effects in the regression model reduce the omitted variable bias (Brown et al., 2011; Li, 2010). We have added the control variables to the empirical models of this study. In Model [1], we have added the firm-specific characteristics that may affect the disclosure of futureoriented information [FSize, FProf, FLiq, FLev, & FDiv]. In addition, in Models [2, 3, & 4], we have added the factors influencing corporate value [FSize, FProf, FLiq, FLev, FDiv, FGrth, & FCapEx]. Furthermore, we have used the year and industry fixed effects. Model [4] Dependent variable Pred. Sign Table 6. Sensitivity analysis results IA_TQ Coefficients (t-statistics) MK-BV Coefficients (t-statistics) Future_DIS þ 1.213** (2.281) 1.519** (2.352) BS þ 0.067 (0.771) 0.083 (0.911) BIN% þ 0.609* (1.759) 0.726* (1.892) CEO_Dul þ 0.035 (0.433) 0.046 (0.512) INST% þ 0.394* (1.714) 0.468* (1.852) AUDIT þ 1.105*** (2.607) 1.261*** (2.941) FL_DIS 3 BS þ 0.016 (0.824) 0.012 (0.574) FL_DIS 3 BIN% þ 0.011 (0.814) 0.013 (1.003) FL_DIS 3 CEO_Dul þ 0.001 (0.295) 0.001 (0.349) FL_DIS 3 INST% þ 0.053** (2.053) 0.061** (2.308) FL_DIS 3 AUDIT þ 0.102** (2.171) 0.117** (2.536) FSize þ 1.869*** (2.735) 2.209*** (2.946) FProf þ/ 1.839*** (2.761) 2.701*** (3.208) FLiq þ/ 0.164 (0.184) 0.190 (0.217) FLev þ/ 0.629** (2.006) 0.743** (2.371) FDiv þ/ 0.659** (2.293) 0.813** (2.438) FGrth þ/ 0.719** (2.308) 1.031*** (3.013) FCapEx þ/ 0.463 (0.950) 0.619 (1.123) Intercept 4.059*** (2.764) 5.453*** (3.261) Year FE Yes Yes Industry FE No Yes F-test 10.194*** 11.936*** R squared 22.751 24.835 Tolerance 0.473 0.509 Observation 534 534 Note(s): *, **, *** means coefficient is significant at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively Endogeneity can also arise due to simultaneity, where a bi-directional relation exists between variables (Lopes and de Alencar, 2010). Lagged variables help reduce this issue (Derouiche et al., 2020; Weir et al., 2002). We re-run Model [1] by regressing future-oriented information score in year t on the CG mechanisms and control variables in year t-1. Similarly, we re-estimate Model [4] by regressing the firm value proxy (F_TQ) in year t on the futureoriented information score, CG mechanisms, and the control variables in year t-1. The results for Models [1] and [4] are demonstrated in Table 7 in Panels A and B, separately. The coefficients for the lagged values in Panel A indicate qualitatively similar findings to the main results of Table 4. Furthermore, the lagged results in Panel B are consistent with the primary results displayed in Table 5. They provide supporting evidence that the disclosure of future-oriented information enhances the values of Kuwaiti firms, especially in firms with less institutional ownership and larger audit committees. Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait 7. Conclusion Kuwait has taken significant steps to reform its CG system by introducing the NCL in 2013. The current study has examined the effect of the observable reform of CG on the disclosure of future-oriented information. Likewise, it has explored how CG mechanisms affect the informativeness of this information. We have used a sample of Kuwaiti-listed non-financial firms over five years from 2014 to 2018. The results indicate that Kuwaiti non-financial firms disclose low levels of future-oriented information in their annual reports, and different CG mechanisms influence this level of disclosure. The empirical results support H1 and find that Model [1] Dependent variable: Future_DIS Coefficient (t-statistics) BS BIN% CEO_Dul INST% AUDIT FSize FProf FLiq FLev FDiv Intercept Model [4] Dependent variable: F_TQ Coefficient (t-statistics) 0.594* (1.683) 1.253** (2.416) 0.085 (0.621) 0.962** (2.132) 1.149*** (2.975) 3.316*** (4.042) 1.952*** (3.238) 0.681 (0.115) 0.718 (0.853) 1.741** (2.137) 2.641*** (4.163) Future_DIS 1.348** (2.019) BS 0.074 (0.896) BIN% 0.608* (1.852) CEO_Dul 0.035 (0.483) INST% 0.538* (1.719) AUDIT 0.916** (2.473) FL_DIS 3 BS 0.012 (0.502) FL_DIS 3 BIN% 0.013 (0.837) FL_DIS 3 CEO_Dul 0.003 (0.305) FL_DIS 3 INST% 0.059** (2.017) FL_DIS 3 AUDIT 0.107*** (2.916) FSize 2.431*** (6.135) FProf 2.169*** (4.806) FLiq 0.106 (0.194) 0.649** (2.072) FLev FDiv 0.751** (2.249) FGrth 1.149*** (3.083) FCapEx 0.138 (0.864) Intercept 3.149*** (6.853) Year-FE Yes Year FE Yes Industry-FE Yes Industry FE Yes F-test 6.832*** F-test 10.472*** Adjusted R-Squared % 41.504 R-squared 21.706 Tolerance 0.539 Tolerance 0.574 Observation 432 Observation 432 Note(s): *, **, *** means coefficient is significant at 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively Table 7. Lagged values results JAAR the board size of Kuwaiti firms inversely influences the disclosure of future-oriented information in the annual reports. Thus, policymakers should consider this point and reform the NCL to reflect suggestions for an optimal level of board size. The results confirm H2 and reveal that independent board members positively impact future-oriented information. This supports the view that they reduce information asymmetry and subsequently increase the levels of disclosure (Goh et al., 2016). However, the results do not find an effect of role duality of a firm CEO on the disclosure of future-oriented information leading to rejection of H3. Besides, they do not confirm H4; however, they support the myopic and short-term view of institutional investors in Kuwait that they induce firm managers to disclose less futureoriented information. The results are in sync with H5 that Kuwaiti firms with larger audit committees disclose more future-oriented information supporting the idea that audit committees are essential in alleviating conflicts of interest between shareholders and managers. Finally, the results partially support H6 and show that future-oriented information enhances the values of Kuwaiti firms with less institutional ownership and larger audit committees. The results add to the agency theory whereby corporate managers disclose relevant voluntarily information which sequentially would be reflected in the enhancement of firm values. These findings provide implications for investors and policymakers in Kuwait. First, policymakers in Kuwait should consider the vital role of CG to improve the transparency of disclosure as a system to mitigate the agency problem. Hence, Kuwait investors looking for more transparent firms would likely be inclined to invest in firms with specific CG mechanisms, including smaller boards, more independent members, fewer institutional investors and more prominent audit committees. Given the economic growth in Kuwait, firms should prioritize the quality of their corporate reporting and their governance mechanisms to fall in line with the authorities’ vision of Kuwait 2035. Second, the results provide a better understanding of how future-oriented information promotes the value of Kuwaiti firms. Hence, policymakers may urge managers to provide more future-oriented information to enhance the value relevance of information available in the annual reports. Subsequently, through investor decisions, they can improve the market valuations of Kuwaiti firms. Finally, Kuwaiti investors may appreciate these findings, as they indicate that fewer institutional investors and larger audit committees strengthen the association between future-oriented information and firm values. Investors might rely on such mechanisms to shape views about corporate value. Overall, the research results support the view that future-oriented information is credible in the Kuwaiti context, though still at low levels. The study has limitations that may be the trigger for future research. The sample is limited to firms listed in Boursa Kuwait. Expanding our research design to include other stock markets in the GCC region can be an area for future research that helps undertake crosscountry analyses for determinants and consequences of future-oriented information. Furthermore, this study focuses on management decisions to disclose future-oriented information in the annual reports. Examining other managerial decisions such as the Research and Development (R&D) spending (Hassanein et al., 2021a, 2022) and other channels of disseminating information such as social media disclosure (Hassanein et al., 2021b) provide avenues for future research. Furthermore, investigating whether futureoriented disclosure in the annual report leads to an information overloading issue (e.g. Alm El-Din et al., 2022) could be an area for future research. Note 1. Financial firms are all firms belongs to the following sectors: banks, insurance, financial services and real estate. References Abad, C. and Bravo, F. (2018), “Audit committee accounting expertise and forward-looking disclosures A study of the US companies”, Management Research Review, Vol. 41 No. 2, pp. 166-185. Abdallah, A.A.N. and Ismail, A.K. (2017), “Corporate governance practices, ownership structure, and corporate performance in the GCC countries”, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, Vol. 4, pp. 98-115. Akhtar, T., Tareq, M.A., Sakti, M.R.P. and Khan, A.A. (2018), “Corporate governance and cash holdings: the way forward”, Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 152-170. Alm El-Din, M.M., El-Awam, A.M., Ibrahim, F.M. and Hassanein, A. (2022), “Voluntary disclosure and complexity of reporting in Egypt: the roles of profitability and earnings management”, Journal of Applied Accounting Research, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 480-508, doi: 10.1108/JAAR-09-2020-0186. Al-Saidi, M. and Al-Shammari, B. (2014), “Corporate governance in Kuwait: an analysis in terms of grounded theory”, International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, Vol. 11, pp. 128-160. Al-Shammari, B. and Al-Sultan, W. (2010), “Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in Kuwait”, International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, Vol. 7, pp. 262-280. Al-Shammari, B., Brown, P. and Tarca, A. (2008), “An investigation of compliance with international accounting standards by listed companies in the Gulf Co-Operation Council member states”, International Journal of Accounting, Vol. 43 No. 4, pp. 425-447. Alazzani, A., Hassanein, A. and Aljanadi, Y. (2017), “Impact of gender diversity on social and environmental performance: evidence from Malaysia”, Corporate Governance, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 266-283. Alfraih, M.M. and Almutawa, A.M. (2017), “Voluntary disclosure and corporate governance: empirical evidence from Kuwait”, International Journal of Law and Management, Vol. 59 No. 2, pp. 217-236. Ammann, M., Oesch, D. and Schmid, M.M. (2011), “Corporate governance and firm value: international evidence”, Journal of Empirical Finance, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 36-55. Arnott, R.D. and Asness, C.S. (2003), “Surprise! Higher dividends 5Higher earnings growth”, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 59 No. 1, pp. 70-87. Barako, D.G., Hancock, P. and Izan, H.Y. (2006), “Factors influencing voluntary corporate disclosure by Kenyan companies”, Corporate Governance: An International Review, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 107-125. Bennouri, M., Chtioui, T., Nagati, H. and Nekhili, M. (2018), “Female board directorship and firm performance: what really matters?”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 88, pp. 267-291. Brockmann, E.N., Hoffman, J.J., Dawley, D.D. and Fornaciari, C.J. (2004), “The impact of CEO duality and prestige on a Bankrupt Organization”, Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 178-196. Brown, S.V. and Tucker, J.W. (2011), “Large-sample evidence on firms’ year-over-year MD&A modifications”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 49 No. 2, pp. 309-346. Brown, P., Beekes, W. and Verhoeven, P. (2011), “Corporate governance, accounting and finance: a review”, Accounting and Finance, Vol. 51 No. 1, pp. 96-172. Buertey, S. and Pae, H. (2021), “Corporate governance and forward- looking information disclosure: evidence from a developing country”, Journal of African Business, Vol. 22 No. 3, pp. 293-308. Chung, C.Y., Cho, S.J., Ryu, D. and Ryu, D. (2019), “Institutional blockholders and corporate social responsibility”, Asian Business and Management, Vol. 18, pp. 143-186. Cohen, J.R., Hoitash, U., Krishnamoorthy, G. and Wright, A.M. (2014), “The effect of audit committee industry expertise on monitoring the financial reporting process”, Accounting Review, Vol. 89 No. 1, pp. 243-273. Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait JAAR Dawd, I. and Charfeddine, L. (2019), “Effect of aggregate, mandatory and voluntary disclosure on firm performance in a developing market: the case of Kuwait”, International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 31-56. Derouiche, I., Muessig, A. and Weber, V. (2020), “The effect of risk disclosure on analyst following”, European Journal of Finance, Vol. 14, pp. 1355-1376. Elgammal, M.M., Hussainey, K. and Ahmed, F. (2018), “Corporate governance and voluntary risk and forward-looking disclosures”, Journal of Applied Accounting Research, Vol. 19 No. 4, pp. 592-607. Feldman, R., Govindaraj, S., Livnat, J. and Segal, B. (2010), “Management’s tone change, post earnings announcement drift and accruals”, Review of Accounting Studies, Vol. 15, pp. 915-953. Goh, B.W., Lee, J., Ng, J. and Ow Yong, K. (2016), “The effect of board independence on information asymmetry”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 155-182. Gujarati, D.N. and Porter, D.C. (2009), Basic Econometrics, 5th ed., McGraw Hill, New York. Gul, F.A. and Leung, S. (2004), “Board leadership, outside directors’ expertise and voluntary corporate disclosures”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 351-379. Haniffa, R.M. and Cooke, T.E. (2005), “The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol. 24 No. 5, pp. 391-430. Hassan, O.A.G., Romilly, P., Giorgioni, G. and Power, D. (2009), “The value relevance of disclosure: evidence from the emerging capital market of Egypt”, International Journal of Accounting, Vol. 44 No. 1, pp. 79-102. Hassanein, A. (2022), “Risk reporting and stock return in the UK: does market competition Matter?”, The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, Vol. 59, p. 101574. Hassanein, A. and Elsayed, N. (2021), “Voluntary risk disclosure and values of FTSE350 firms: the role of an industry-based litigation risk”, International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 110-132. Hassanein, A. and Hussainey, K. (2015), “Is forward-looking financial disclosure really informative? Evidence from UK narrative statements”, International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 41, pp. 52-61. Hassanein, A. and Kokel, A. (2019), “Corporate cash hoarding and corporate governance mechanisms: evidence from Borsa Istanbul”, Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting and Economics, pp. 1-18. Hassanein, A., Zalata, A. and Hussainey, K. (2019), “Do forward-looking narratives affect investors’ valuation of UK FTSE all-shares firms?”, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, Vol. 52, pp. 493-519. Hassanein, A., Marzouk, M. and Azzam, M. (2021a), “How does ownership by corporate managers affect R&D in the UK?”, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, Forthcoming, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print, doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-03-2020-0121. Hassanein, A., Moustafa, M.M., Benameur, K. and Al-Khasawneh, J. (2021b), “How do big markets react to investors’ sentiments on firm tweets?”, Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, Ahead-of-print, pp. 1-23, doi: 10.1080/20430795.2021.1949198. Hassanein, A., Al-Khasawneh, J.A. and Elzahar, H. (2022), “R&D expenditure and managerial ownership: evidence from firms of high-vs-low R&D intensity”, Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print, doi: 10.1108/JFRA-07-2021-0205. Healy, P.M. and Palepu, K.G. (2001), “Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: a review of the empirical disclosure literature”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 31 Nos 1-3, pp. 405-440. Henry, D. (2008), “Corporate governance structure and the valuation of Australian firms: is there value in ticking the boxes?”, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, Vol. 35 Nos 7-8, pp. 912-942. Hoitash, U., Hoitash, R. and Bedard, J.C. (2009), “Corporate governance and internal control over financial reporting: a comparison of regulatory regimes”, Accounting Review, Vol. 84 No. 3, pp. 839-867. Hussainey, K. and Al-Najjar, B. (2011), “Future-oriented narrative reporting: determinants and use”, Journal of Applied Accounting Research, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 123-138. Hussainey, K., Schleicher, T. and Walker, M. (2003), “Undertaking large-scale disclosure studies when AIMR-FAF ratings are not available: the case of prices leading earnings”, Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 275-294. Jensen, M.C. and Meckling, W.H. (2012), “Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 305-360. Karamanou, I. and Vafeas, N. (2005), “The association between corporate boards, audit committees, and management earnings forecasts: an empirical analysis”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 43 No. 3, pp. 453-486. Kim, J.W. and Shi, Y. (2011), “Voluntary disclosure and the cost of equity capital: evidence from management earnings forecasts”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 348-366. Kim, K.A., Kitsabunnarat-Chatjuthamard, P. and Nofsinger, J.R. (2007), “Large shareholders, board independence, and minority shareholder rights: evidence from Europe”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 13 No. 5, pp. 859-880. Klein, A. (2002), “Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 33 No. 3, pp. 375-400. Krause, R., Semadeni, M. and Cannella, A. (2014), “CEO duality a review and research agenda”, Journal of Management, Vol. 40 No. 1, pp. 256-286. Lakhal, F. (2005), “Voluntary earnings disclosures and corporate governance: evidence from France”, Review of Accounting and Finance, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 64-85. Li, F. (2010), “The information content of forward- looking statements in corporate filings-A naı€ve bayesian machine learning approach”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 48 No. 5, pp. 1049-1102. Liu, C., Uchida, K. and Yang, Y. (2012), “Corporate governance and firm value during the global financial crisis: evidence from China”, International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 21, pp. 70-80. Lopes, A.B. and de Alencar, R.C. (2010), “Disclosure and cost of equity capital in emerging markets: the Brazilian case”, International Journal of Accounting, Vol. 45 No. 4, pp. 443-464. Mahboub, R.M. (2019), “The determinants of forward-looking information disclosure in annual reports of Lebanese commercial banks”, Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, Vol. 23 No. 4, pp. 1-18. Mangena, M., Tauringana, V. and Chamisa, E. (2012), “Corporate boards, ownership structure and firm performance in an environment of severe political and economic crisis”, British Journal of Management, Vol. 23 No. S1, pp. S23-S41. Menicucci, E. (2018), “Exploring forward-looking information in integrated reporting: a multidimensional analysis”, Journal of Applied Accounting Research, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 102-121. Merkley, K.J. (2014), “Narrative disclosure and earnings performance: evidence from R&D disclosures”, Accounting Review, Vol. 89 No. 2, pp. 725-757. Muslu, V., Radhakrishnan, S., Subramanyam, K.R. and Lim, D. (2015), “Forward-looking MD&A disclosures and the information environment”, Management Science, Vol. 61 No. 5, pp. 931-1196. Nikolaev, V. and van Lent, L. (2005), “The endogeneity bias in the relation between cost-of-debt capital and corporate disclosure policy”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 677-724. O’Sullivan, M., Percy, M. and Stewart, J. (2008), “Australian evidence on corporate governance attributes and their association with forward-looking information in the annual report”, Journal of Management and Governance, Vol. 12, pp. 5-35. Wallace, P. and Zinkin, J. (2005), Corporate Governance, Mastering Business in Asia, John Wiley & Sons, Singapore. Futureoriented disclosure in Kuwait JAAR Wang, M. and Hussainey, K. (2013), “Voluntary forward-looking statements driven by corporate governance and their value relevance”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol. 32 No. 3, pp. 26-49. Weir, C., Laing, D. and Mcknight, P.J. (2002), “Internal and external governance mechanisms: their impact on the performance of large UK public companies”, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, Vol. 29 Nos 5-6, pp. 579-611. Yuen, D.C.Y., Liu, M. and Zhang, X. (2009), “A case study of voluntary disclosure by Chinese enterprises”, Asian Journal of Finance and Accounting, Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 118-145. Corresponding author Ahmed Hassanein can be contacted at: Hassanein.a@gust.edu.kw; Ahmeda1@mans.edu.eg For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com