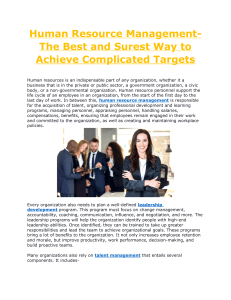

le 8 Developing talent DEVELOPING TALENT AT KONE With more than US$11 billion in sales and 60 000 employees in more than 60 countries, Finland-based KONE is one of the leading players in the global elevator and escalator industry. The biggest growth opportunities are in China, and despite being a latecomer, KONE is the market leader there. Talent management has played an important role in KONE’s international expansion.' At the heart of the global talent management system is an annual Leadership and Talent Review (LTR), which covers all businesses and areas. The Executive Board sets annual targets for the LTR, including gender and regional diversity goals, recruitment targets (e.g. proportion of hires outside of the elevator and escalator industry), and talent development actions (e.g. proportion undergoing job rotation including cross-functional and international moves). The talent identification part of the LTR involves the identification of “Emerging Leaders”. Areas and business units nominate 1-5 percent of their employees above a certain level as Emerging Leaders. Initially, the same criteria applied in all countries. However, after several promising candidates missed out on being identified due to insufficient English language skills or unwillingness to be internationally mobile, KONE created a separate category: Local Emerging Leaders.* The new category is particularly important in China, where many candidates may fail to meet the global emerging leader language and mobility criteria and where KONE faces stiff competition for talent. The succession planning part of the LTR is designed to ensure that there are internal candidates to address any gaps or changes in leadership. KONE creates succession plans for all positions above a certain level and proposes successor candidates. The objectives of the yearly LTR workshops are to share talent needs and gaps, facilitate cross-border moves and rotations of current management team members and successors, review the emerging leaders, discuss the successor candidates in terms of readiness using “traffic light” indicators, and review the development actions taken. KONE also holds managers accountable for talent development. In addition to engaging in informal discussions and providing feedback on an ongoing basis, managers are expected to create high-quality individual development plans with all their emerging leaders. Leadership development plans are based on the 70-20-10 philosophy, whereby 70 percent of the development actions are based on on-the-job experiences such as new roles and stretch assignments, 20 percent on learning from and with others through coaching, mentoring and networking, and 10 percent on formal development interventions such as virtual and face-to-face training. Based on the firm belief that leaders cannot lead and help others to grow unless they can manage themselves, KONE emphasizes self-awareness and self-leadership. One of its key development actions is mobility. Global and country HR managers, together with @ THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE the employees and their superiors, are responsible for discussing the next career steps and organizing the moves. The aim is also to build a coaching culture throughout the firm. In some global leadership programs, participants are assigned an internal coach, and all emerging leaders are assigned a mentor. External as well as internal mentors are used, and virtual mentoring training is arranged for all managers. In China, KONE has decided that a more tailored leadership development program is needed, including the roll-out of a formal training program run in Chinese. In recent years, KONE has ramped up efforts at managing retention. As part of the talent reviews, all staff employees are evaluated in terms of the risk of them leaving the firm and their “loss impact’—the impact the departure of that employee would have. Data are fed into the system that allows KONE to track “Critical Talent”, employees above a certain level whose loss impact is significant and whose performance is consistently strong. These individuals are discussed during the LTR workshops in order to agree on retention actions and ensure a succession pipeline. This involves discussions with employees about meeting career and development needs. If necessary, they may also be offered monetary incentives to stay in the firm. Nonetheless, how to retain key talent remains a challenge in China and elsewhere. OVERVIEW The quality of current and future leadership is invariably an area of top management concern at global companies like KONE. Moreover, multinational firms need to invest in the broader upskilling in the workforce to respond to the competence gaps created by digitalization and related changes in the strategy of the corporation. In this chapter, we start by discussing leadership in the context of the multinational firm, highlighting the challenges in identifying potential leaders, such as understanding leadership behavior across countries and defining the required global leadership competencies. We then explore some of the dilemmas around leadership development practices. Subsequently we examine the development of the workforce more generally to meet the needs brought about by technological changes and shifts in corporate strategy. The chapter concludes with a discussion on what multinationals can do to enhance the engagement of their employees and to improve retention rates. LEADERSHIP IN THE GLOBAL CONTEXT Before discussing the particular features of leadership in the context of international firms like KONE, it is useful to pause for a moment to first briefly reflect on what we mean when referring to leadership in general and how the notion of (good) leadership has changed over time. For the purpose of this book, we view leadership as the processes and actions through which an individual influences internal and external stakeholders.’ It is important to distinguish between the “leader” as a role, someone occupying a position of authority, and “leadership” as DEVELOPING TALENT © behaviors—our focus is on the latter. People who are not necessarily in formal leader roles may display strong leadership behaviors, and intuitively we think of these as high potential people. Conversely, some people may occupy leader positions but display no leadership. The notion of good leadership has changed over time and varies across countries and cultures.* In today’s flatter organizations, managers and executives need to be participative but at the same time provide clear direction and purpose. A major recent research project on leadership with data from more than 120 countries found that some leadership behaviors are eroding, some are enduring, while others are gaining importance. Important emerging leadership behaviors include being purpose-driven, making data-driven decisions, and demonstrating authenticity.’ Although many traditional leadership behaviors remain important—such as creating a clear vision, focusing on performance, and leading by example—there are strong calls for managers and executives to engage more in coaching their team members than in micro-managing their subordinates and exercising strong command and control,’ Managers are encouraged to use dialogue to help their subordinates arrive at their own solutions. Rather than “tell and sell”, managers are encouraged to “ask and listen”.’ Leadership behaviors across countries There is a long history of research into the differences and similarities in leadership behaviors across nations.” The most extensive study to date is the GLOBE project"? (described in Chapter 2). In this project, the researchers identified a number of leadership traits that were viewed as acceptable across countries, others that were universally unacceptable, and some that were seen as acceptable in some cultures but not in others. Developing a vision, inspiring others, and demonstrating integrity and decisiveness were perceived as being positive leadership attributes in all countries. Likewise, being egocentric, asocial, and dictatorial were uniformly condemned. However, other qualities—such as being enthusiastic, risk-taking, sincere, and compassionate—were viewed positively in some countries but negatively in others." The results of this and other comparative leadership studies have several implications. First, the national context influences what is typical leadership behavior. Second, the context has an impact on expectations and evaluations of people in positions where leadership is expected—individuals whose behaviors fit with those of the country in question are perceived to be more effective. So managers should be aware of this and may try to adapt their behavior to the local environment. Third, when managers have subordinates from different cultures, they may be evaluated differently depending on the background of the followers. Finally, in the context of the multinational enterprise, evaluating whether somebody has the potential to do well as a leader across countries is difficult: to what extent can one rely on local input when assessing whether or not a manager has the potential to become a future global leader for the corporation? © THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE Global leadership competencies The belief that leadership in global settings requires different skills from “domestic” leadership is widely shared. When David Whitwam, then CEO of Whirlpool, was steering the company’s transition from a domestic US player to a global firm, he commented: I've often said that there’s only one thing that wakes me up in the middle of the night. It’s not our financial performance or economic issues in general. It’s worrying about whether or not we have the right skills and capabilities to pull the strategy off ... It is a simple and inescapable fact that the skills and capabilities required to manage a global company are different from those required for a domestic company.” While there is agreement that leading a global company requires a particular skill set, there is no accepted definition of global leadership or established body of tested theory.” Still, a substantial body of literature has addressed the question of what competencies global managers need and how these can be developed."* Many global leadership competencies have been singled out and these can be viewed as a pyramid, as shown in Figure 8.1, At the base is the global knowledge and understanding that comes, above all, through contact with people of different backgrounds while working and living abroad, as well as through education and experience. Then certain threshold leadership traits are required—we discuss openness to challenge and learning agility later in this chapter. The next three layers form the core global competencies, including attitudes and interpersonal and systemic skills. Many of these competencies have been mentioned in other chapters, but we see four as particularly important for global leadership. Global leaders need a high tolerance for ambiguity, along with the ability to work with the contradictions that are at the heart of a global mindset. It is also clear that leaders need strong interpersonal skills to build relationships with people of widely diverging backgrounds, including emotional self-control and the ability to handle conflict. Finally, as discussed in Chapter 4, the ability to exercise influence without authority is essential for effective lateral coordination in multinational enterprises. Some people would like to believe that such global skills can be learned at home by working with a diverse workforce. However, the prevailing view is that the experience of living and working overseas is indispensable for the development of over half of all significant global competencies.’* Indeed, individuals who have lived abroad, either for personal or career-related reasons, tend to show heightened levels of creativity and integrative complexity (flexible thinking). Further, research indicates that the more individuals strive to understand and successfully adapt to the local culture, the higher the competence development benefits for creativity and flexibility.° Intense multicultural experience has also been found to be positively related with a global mindset and effectiveness in global leadership roles.!” While managers and executives can learn many important business lessons at home, they will best embrace those deep lessons, ones that go beyond simple intellectual understanding, through international mobility. DEVELOPING TALENT /\ © Ky, / / i ‘ / j ff if \ \\ / Systemic \, f skills = \, ‘Making ethical decisions \ * Influencing \ stakeholders / Leading change Spanning Building cohesion eo : \, \ boundaries \ Interpersonal skills i pf - / Influencing / without authority — / y \ - Cognitive complexity Integrity ° \ Global mindset / Source; . Multinational lationship building ———_-_— Attitudes and orjentations 7 / Creating and building trust i \ Tolerance for ambiguity Threshold traits Openness to challenge \ Learning agility Global knowledge through sacial networks ee ' \\ ° Resilience \\ _— ee Adapted from Bird and Osland (2004). Figure 8.1 The pyramid model of global leadership Leadership transitions One of the limits to the idea of mapping out global leadership competencies is that the leadership skills needed in one position in the multinational firm are different from those needed in another. A long tradition of research, gaining momentum in the last decade, has explored this notion of leadership “intransitivity”, the recognition of which goes back more than 50 years to the humorous “Peter Principle”.'* The challenges of transitioning to a new managerial role that to some extent requires different behaviors have been explored by many researchers—people tend to use the behaviors that led them to be successful in the past.’ The concept of leadership as a “pipeline” captures this, a series of 3-5 transitions requiring different skills from those needed at the previous level.”° This intransitivity has important implications for global leadership development. It has been argued that in the fast-moving global competitive environment, the operating managers heading up business units and subsidiaries need to be bold entrepreneurs, creating and pursuing new business opportunities, as well as attracting and developing resources, including people. In contrast, the senior managers heading up businesses and countries/regions need to be integrative coaches with strong skills in lateral coordination, able to cope with the complexity of holding vertical and horizontal responsibilities simultaneously. They must be able to stretch and at the same time to support the local units; they must facilitate cross-border learning, building strategy out of entrepreneurial initiatives. Finally, top managers need to be institutional leaders with a longer time horizon, nurturing strategic development © THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE opportunities, managing organizational cohesion through global processes and normative integration, and creating an overarching sense of purpose and ambition.” Many people who perform well in entrepreneurial leadership roles at the operating level will find it difficult to adjust to more ambiguous roles as lateral coordinators in business areas or regions. Companies must identify individuals with the potential to master such a transition and provide appropriate developmental experiences to build these new skills. While the ability to make a particular known transition is important, the ability to cope with transitions in general is an important overarching competence for leaders—hence, the importance of learning agility, to which we return later. IDENTIFYING AND ASSESSING LEADERSHIP POTENTIAL As outlined in Chapter 6 and exemplified in the KONE opening case, talent management embraces all the key people management practices: recruiting and selecting talented people, managing their performance, paying attention to diversity and inclusion, developing them, and then retaining such people in whom a considerable investment may have been made. Developing global leaders starts off with the question of who to develop. Who should scarce resources be focused on? Who should get the challenging jobs that are vital to strategic success? In other words, who has global leadership potential? The ways of selecting people for leadership roles—of identifying potential—vary from company to company and nation to nation. Some multinationals have developed comprehensive leadership and assessment programs that are rolled out globally. PepsiCo’s Leadership and Development Program operates in 11 languages and contains different means of assessment for four different hierarchical levels. The first level, the Potential Leader program, is offered globally to thousands of employees who meet certain performance thresholds. The assessments for Potential Leader are all done online, containing a suite of tools covering cognitive, personality, situational judgment, and biographical information. All participants receive developmental feedback and coaching from managers as part of the process.” We discussed in Chapter 6 the different regional heritages in when leadership potential is identified. The prevailing pattern today is that local units recruit and develop professionals for functional jobs, and individuals from within these ranks are subsequently identified as High Potentials (HiPO)—or “emerging leaders”, as in KONE—using assessments of their performance and potential.’ One survey found that 60 percent of large corporations used this approach, asking local affiliates to identify talent that can be moved into corporate development programs.” This assessment typically is part of an annual or periodic review, such as KONE’s LTR. At the core of such reviews is an assessment of the persons across two or more dimensions, traditionally often in the shape of what is known as a nine-box assessment. Figure 8.2 shows the framework pioneered by GE and used since by the pharmaceutical giant Novartis and many other corporations.” Performance evaluations represent one dimension of the framework. The definition of the second dimension, which we summarize as “potential”, varies from firm to firm. In some, DEVELOPING TALENT © ative Performance objectives | will as or Exceeded ition expectations cope , the Fully met : aap expectations ones Benaiey Good fesuits/ unsatisfactory heRavior i | Superior results/ good behavior — recognized as tale , model Strong performer | (fully acceptable level of - _ performance) Partially met . expectations Unsatisfactory performer : Gud Be yavied unsatisfactory rformer pe Fartially met nent ople, 1e€m, expectations Source: tegic rom hen‘and nent ered 5eSStive, ceive ial is nals ‘d as their _this ‘lopX. At tra- 3 the Fully met expectations . aero behavior/ good results Superior behavior/ : unsatisfactory performer Exceeded expectations Values/ behaviors Chua et al. (2005). Figure 8.2 ould Exceptional performer and Example of a nine-box assessment tool potential is gauged by whether someone demonstrates the key values and behavio rs that the company looks for in its future leaders—whether their identity, values and motives connect with the purpose of the corporation; we argue in Chapter 14 that this is particularly important to promote sustainability. The review process should not only focus on identifying and then developing individuals in the top right-hand box of Figure 8.2, who are strong on both dimensions, but also those in all four corner boxes, It is worth emphasizing that Shell, and other companies that depend on the quality of their technical and functional talent, focus a great deal of attention on the development of people who are likely to pursue careers only within their functions. And deep questions need to be asked about those who are seen as having high potential but are current ly underperforming. Are they misfits? Are they being constrained by difficult bosses? Finally, most companies want to identify the underperforming people with low petential—to turn them around or to turn them out. Recently Novartis and many other multinationals have gone beyond examining only two dimensions when evaluating leadership potential.** In KONE, the framework for reviewing emerging leaders has four sets of criteria: Basic Requirements (English language skills, minimum 6 months’ tenure in KONE, and being mobile”’), Perform ance (strong past performance and behavior in line with corporate values), Enablers (learning focus, collaboration & inclusion, energy & resilience, and achievable level/growth capacity ), and Motivation (aspiration to become a leader, motivation to stretch beyond current responsi bility, and engagement). The ability to learn fast and well is one of the most important of these qualities. iany Assessing learning capacity f the Individuals vary in their ability to handle big challenges and to learn from their experiences. me, Some people seek out feedback proactively, consult with others, and in effect organize their THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE @ own coaching; others do not, preferring to do what has worked well for them before. As the box titled “How fast do you learn?” outlines, learning agility is an important element of leadership potential, HOW FAST DO YOU LEARN? People’s learning speeds vary. One study of 838 managers in six multinational corporations’ explored the individual characteristics that distinguished successful global leaders from solid performers who lacked leadership potential. Eleven characteristics differentiated the two groups, and factor analysis showed that there were two different underlying dimensions, as shown below. The first dimension, encompassing characteristics like the courage to take risks, captures the willingness to assume challenges. The second dimen- sion, with characteristics like seeking out feedback and learning from mistakes as well as criticism, expresses learning agility. ELEVEN CHARACTERISTICS DISTINGUISHING HIGH-POTENTIAL LEADERS FROM SOLID PERFORMERS IN SIX INTERNATIONAL CORPORATIONS” Factor 1: (Willingness to take on challenges) e ¢ ° Seeks opportunities to learn; Iscommitted to make a difference; Has the courage to take risks. Factor 2: (Learning agility) e e e Adapts to cultural differences; Is insightful: sees things from new angles; Seeks and uses feedback; e Is open to criticism. e Learns from mistakes; Other Characteristics e Acts with integrity; « Brings out the best in people, e Seeks broad business knowledge; The importance of learning agility for leadership development has long been recognized, both by corporations and in academic studies. Indeed, it has been described as an important meta-competence for managers” and the overall relationship between learning agility and leadership success is well established.” Infosys recruits professionals at entry level for “learnability”. Learnability is defined as the consistent ability to derive generic knowledge from specific instances. Potential leaders are tested for how quickly they can learn new concepts and then apply them to unfamiliar situations.” DEVELOPING TALENT © Dilemmas in the global leadership selection and review process The process of identifying global leadership talent and deciding who should get the most rewarding developmental opportunities is fraught with questions. We focus below on dilemmas that are particularly salient to the multinational setting. When to identify potential? A lot of career politics is associated with getting visibility early on in the eyes of top man- agement in order to secure good development opportunities. However, there are dilemmas associated with the age at which potential should be identified—early or late? For example, Japanese companies have historically identified potential at the time of graduate recruitment, leading to an extended developmental trial period. This makes sense in a culture where individuals pursue lifelong careers in the same firm—indeed it is still not common for Japanese firms to recruit from outside. In Anglo-Saxon countries, however, other firms are likely to poach HiPOs (high potentials), especially if the enterprise has a reputation for excellence in selection and development. This happened to P&G back in the past when it developed a reputation as a top-notch incubator, feeding the management ranks of competitors in the fast-moving consumer products industry. Alternatively, one could argue for the late identification of talent, by which time experience and track record enable one to make good judgments on potential. However, this strategy is similarly problematic since top talent may get frustrated and leave the firm if they are not singled out as talent early, Moreover, there is less time for high payoff developmental actions such as international moves and project work.” If talented international employees are identified much later than those in the home country, their leadership prospects will be compromised for these reasons. Indeed, this may be a factor explaining why GE was less successful in developing leaders from their Asian operations. Talented individuals in the US were spotted much earlier than their counterparts in Asia in part because until recently GE had few regional corporate offices outside the US that could take on the task of identifying and developing regional talent. This example points to the importance of having a truly global approach to talent identification in multinational corporations. How much transparency? A key challenge in talent identification is fairness, known as procedural justice,* and multi- nationals should try to ensure that the evaluation of performance and potential is undertaken on a globally consistent basis. However, once a judgment has been made about who has potential, there are often dilemmas concerning the appropriate degree of transparency about the decision. As in KONE, multinational firms from egalitarian cultures wrestle with the issue of whether °F not to inform HiPOs about their status after talent reviews. The differential treatment of such employees in terms of developmental support or compensation can be a sensitive Matter. If the HiPO status is not visible, this can lead to frustration and turnover among high Performers who do not feel adequately recognized. Being formally recognized as a member @ THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE of the talent pool is found to increase willingness to accept challenging assignments in the future.* However, if a company openly communicates HiPO status, they face two possible corresponding negative outcomes: first, good performers who were not identified as HiPOs are likely to lose motivation and leave; and second, unrealistic expectations about advancement might be expected among those identified as having potential. The former is unavoidable, endemic to any “quota” process, and one can argue that keeping people in the dark about their career progress in the hope that they will stay in the firm is shortsighted, if not unethical. As for the second fear, if one accepts that people develop through challenge, then one consequence of being identified as HiPO is an expectation of stretch. It is both difficult and ill-advised to hide this designation, though most companies choose to communicate it with a certain amount of discretion. Indeed, some firms have recently changed their policies and today inform HiPOs about their talent status. Some companies have responded to these dilemmas by encouraging self-nomination instead of top-down identification, for example, by submitting a list of peers and superiors who will be asked to provide references, similar to the process of tenure review in the academic world.” Ensuring that judgments on potential are reviewed regularly can mitigate some of the risks associated with transparency. Those who are not yet identified as HiPOs then have an incen- tive to work their way into the designated talent pool, while those that are labeled as HiPOs realize that they need to continue to prove themselves to progress in their careers. The quality of these periodic reviews is arguably one of the most important aspects of talent management.” Who should be responsible for identifying talent? Multinational corporations coming from a heritage of local responsiveness face a major challenge in this arena: how to get the local company to pay attention to identifying HiPOs when they are at early career stages? In a tightly run, cost-conscious local operation, there may not be much room for high potential people with advanced degrees and high expectations but little hands-on experience. Given that the skill requirements at one level of responsibility are different from those at the next hierarchical level, the process of identification and development of high potential individuals should be managed carefully to ensure the mobility and support (what we in the next section call “people risk management”) that is vital for development.*® Some firms are explicit about this: those individuals become what many multinationals call, formally or informally, “corporate property”. A widespread obstacle to leadership identification in multinationals is the natural tendency of subsidiary managers to act in their own interests and hide their best people.” The more one praises an indispensable individual, the more likely the person is to be moved elsewhere under the banner of leadership development. A survey of HR executives from multinational firms singled out this problem as one of the major challenges in talent management.” Consequently, chief executives such as A.G. Laffley, who used to head up P&G, are adamant about the importance of releasing talent, since talent development is a corporate value on a par with financial performance.” For them, hiding talent is an act of corporate disloyalty. Haier is among the DEVELOPING TALENT © many multinationals that include the leadership development of others as a performance criterion. In the past one might have expected loyal expatriates, representing the corporate perspective, to combat such silo tendencies; but in many markets the senior ranks are increasingly local. This is why identifying and nurturing talent becomes a key responsibility of regional management or of an experienced HR manager who works with subsidiaries across the region. KONE and several other multinationals have global talent managers who support all units, Schlumberger navigates this issue by re-engineering the whole process, In countries where local management is operationally focused and strongly technical in orientation, the corporate or regional HR function recruits individuals with perceived high potential, who are then placed in entry-level functional jobs in a third country that has a reputation as a talent incubator. When these recruits have successfully mastered the core operational roles, they are repatriated to their home country for the next step as engineering or service managers—subsequently moving again if they progress further. How to avoid bias in global talent reviews? The purpose of differentiating between people, for example, on two dimensions as in nine-box reviews, is not just to place people’s names in boxes, but to ensure that an open dialogue takes place about their performance, potential, and career aspirations as well as the development implications. However, too often talent reviews are nothing more than formal rituals performed by a quasi-representative committee of stakeholders defending their favorite candidates, Local bosses are often reluctant to differentiate among their managers. At a KONE talent review in Asia, a country head rated all his managers as “exceeding expectations”, At the meeting the regional executive told him that, “if you rate them all as excellent you prevent them from growing”—and it was a light bulb moment for that country manager. One pitfall is that leadership potential reviews are often biased against managers who are far away and who do not have personal relationships with key decision-makers at headquarters. The head office people with power may give an individual who locals see as talented only token consideration. Consciously or unconsciously, they do not trust local inputs and ratings, and they give, at best, a formal stamp of approval to the person. Moreover, there is an inevitable halo effect—candidates who share certain similarities with the evaluators are judged as having higher potential.“ Local units learn that their views are not taken into account, so they start taking the process lightly—the makings of a self-fulfilling prophecy. The consequence will often be that the best local employees will look for opportunities outside the firm. To minimize such risks, companies should make sure their senior executives get to know local talent. An important consequence is the loss of procedural justice and the diminished credibility of both the review and the appointment-making process in the eyes of managers and potential future leaders around the world. The quality of information, candid dialogue among line executives, and professional preparation by both line and HR should lie at the heart of the talent review. ® THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE How to move beyond identification? The purpose of formally identifying and reviewing people with leadership potential is to ensure what we term “unnatural acts”—value-added actions that would not happen unless attention has been paid to fair assessment of potential. An example of such an action would be ensuring that local nationals who do not have an impressive education but who demonstrate high potential come to the attention of senior management, and that they are provided with special coaching to accompany a challenging assignment that would otherwise have been given to an employee of the home country of the corporation. In this respect, many multinational firms fall into the trap of engaging in excessive identification and assessment of potential, at the expense of development action. This is partly because the identification side of leadership development involves work that can be facilitated by the HR function, increasingly using globally standardized tools and processes. On the other hand, HR cannot undertake much on the development side without the commitment of the business managers—apart from sending someone on a corporate training program or assigning them a mentor or coach. This has important implications. First, companies may be advised to be selective, even conservative, in their judgments about who is of high potential, because it is preferable to under-forecast rather than over-forecast future needs. Undertaking rigorous reviews is time-consuming, and not worth doing unless it is done well. And if the catch net is too wide, it will dilute the attention line managers give it. At KONE no more than 5 percent of the work- force can be considered as emerging leaders, in line with the practice of other multinationals with proven track records in leadership development. Second, senior line managers in the business or functional units must adopt a talent development mindset and take ownership of leadership identification and reviews.* The HR function has to undertake important groundwork, but it is the attention of line managers and those at the top of the organization that matters most. The former CEO of P&G, cited above, commented: “I spend a third to half of my time on leadership development [...] Nothing I do will have a more enduring impact on P&G’s long-term success than helping to develop other leaders.””’ THE PRINCIPLES GUIDING GLOBAL LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT We start our assessment of the principles and tools for steering global leadership development with an overview of the experiences that successful global executives identify as contributing most to their own development. Researchers interviewed 101 senior executives from 36 countries, covering all major regions of the world.” Major line assignments, particularly those involving managing change, figured prominently on the list of important development experiences, as did special projects and consulting roles. Also high on the list were mobility and transition experiences that led to a deep change in perspective, such as culture shocks and career shifts, Above all, people were found to develop through challenging assignments and experiences. DEVELOPING TALENT @ Challenge is the starting point We often take managers back to basics by asking them, “How do you develop people?” They quickly come up with a number of responses: through feedback, coaching, mentoring; setting goals, assigning responsibility; encouraging learning from mistakes, training, and so forth. Some people emphasize that development happens on the job. But they often miss the most central point: at the heart of development is the simple principle that people learn most by doing things they have not done before.” People develop above all through challenge, by venturing outside their comfort zones. Test this yourself. Ask others to tell you about the experiences that were most valuable for their development. Surprisingly enough, people hardly ever mention training and education. Some may talk about a relationship with a significant mentor or role model. But the vast majority will describe some stretching challenge that they worked through, often succeeding but sometimes failing, often in professional life but sometimes in private life, sometimes planned but equally often by chance. Indeed, a common denominator we found in our research on leaders who make a difference, in technical or managerial positions, is that they respond more positively than other people to challenge, seeing opportunities where others perceive threats. The most important question in talent development is probably, “Who gets the important experiences?” Challenging jobs should above all go to people with the potential to grow. However, being identified as high potential is only the beginning—unless the corporation ascertains that they also get stretching developmental assignments and sufficient support, few changes are likely to take place in the composition of the senior management team. Cross-boundary mobility as a key tool Although the concept of leadership varies with culture and context, there is more agreement on how to develop leadership skills. Mobility—the movement from one function or geographic location to another*'—is the critical lever. Through the transition to new challenges outside their expertise, people learn how to lead as opposed to relying on their authority of expertise or formal position. People who pursue careers in business typically start by developing their talents within a particular function or discipline. A capable person will move up into supervisory and managerial responsibilities, developing knowledge and skills in people management, goal setting, planning, and budgeting. There are various transitions to be mastered during this upward path, notably the transition from being an individual contributor to being a people manager, although many people still rely on their expertise, falling into the trap of excessively telling people what to do.” If the company feels that someone has strong leadership potential, it might put that person in a position where s/he has to learn to lead—by removing their expertise. It is an uncomfortable, challenging but potentially rich learning experience. Moving to another function or across borders to another culture removes prior experience and expertise, placing people in challenging positions where they have to learn integrative leadership skills of setting direction © THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE and aligning people, while focusing on strategic development. The box titled “Unexpected route to the top” provides a powerful example of both. UNEXPECTED ROUTE TO THE TOP The most important tools for leadership development are not assessment techniques or MBA programs, or any other form of training, It is challenge through mobility— experience in a job outside one’s expertise or home culture where one has to learn how to deliver results through the expertise of others who are different from oneself, The story of a senior executive in a major multinational corporation illustrates this point. When we interviewed him a number of years ago, he was president of an important subsidiary in Asia, had an excellent record of leadership success, and had deep skills in the management of people. He told us: What led me to this position? It is quite simple. I was trained as a geologist and spent the first seven years of my career trying to discover oil. One day when I was heading an exploration assignment, they called me to the headquarters and told me that they wanted me to take over the responsibility for a troubled department of 40 maintenance engineers on the other side of the world. Geology is the noble elite, and maintenance engineering is somewhere between here-and-hell in the value system. I didn’t want the job—in fact my first thought was that they were punishing me for some mistake I had made—and I told them that I knew nothing about maintenance engineering. “We're not sending you there to learn about engineering,” they said. “We are sending you there to learn about leadership.” With a lot of doubts, I took the job, and I was there for just over four years. And I learned practically everything I know about management and leadership in that job—all I’ve done since is refine what I picked up there. Mind you, it was the most stressful job ’'ve ever had—it nearly cost me my marriage! Fortunately, they sent me on a management training program during the first three months, and that helped me to understand what was happening and how to adjust— otherwise I might not have survived. Afterwards I returned into a more senior position in oil exploration, but I'd completely changed as a result of that experience with the maintenance engineers. Later, this executive became CEO of one of the largest multinational corporations in the world. Functional mobility entails moving outside one’s area of expertise. Another type of mobility is geographic. Both types foster situational skills—the ability to handle context. Mobility fosters the “helicopter” ability to see the context and big picture and yet to zoom in on the details,” and most companies acknowledge that international experience is desirable if not essential for leadership of a multinational corporation. Multicultural experience is positively related to creative performance (learning from insights, idea generation, and remote association) as well as the ability to exploit unconventional knowledge and creative ideas. DEVELOPING TALENT © Take the “haute couture” fashion sector, Research has shown that the longer creative direc- ed tors of global fashion houses have worked abroad (the depth of their international experience) and the more foreign countries they have worked in (the breadth of their exposure), the more creative they are.” Karl Lagerfeld, one of the most influential persons in fashion, is an example, a German who was based in Paris after first having worked in Tokyo and New York. Learning how to work vertically and horizontally at the same time As we have shown throughout this book, many tasks in today’s multidimensional firms require the capacity to take horizontal leadership initiatives while assuming responsibility for results in one’s own job. Therefore, important tools of leadership development are cross-boundary project assignments—what we in Chapter 4 referred to as working in split egg ways. According to a survey of 12 000 business leaders around the world, special projects within the job that allow cross-functional exposure, the honing of project management skills, and fostering business acumen were at the top of the list of tools for effective leadership development. When working in split egg ways, traditional conceptual differences between management and leadership start breaking down. The individual is expected to be both an effective manager—doing things right in the operational role—and an effective leader—doing the right things in the project role. The former involves operational performance management; the latter requires leadership initiative, guided by the purpose and long-term strategic priorities of the firm. Split egg assignments are necessary for developing the pyramid of skills for global leadership (mentioned earlier in this chapter), skills such as: @ is TS 53 ial to ell Leadership without authority: Much of the work as a leader in the multidimensional firm requires influencing people in other parts of the firm, without having any formal authority over them. These skills become more and more important as managers move up the organization; involvement in top-of-the-egg initiatives fosters such skills, @ People management: How do you free up 20 or 30 percent of your time for project initiatives when you are also responsible for delivering on tough operational targets? Having good people to whom you can delegate becomes a matter of personal success. Managers in split egg roles learn to pay rigorous attention to staffing—getting the right people into the right places—as well as to negotiating performance objectives and coaching subordinates. © Teamwork mastery: Various team skills are vital in today’s multinationals—building trust and respect, managing conflict and contention, negotiating clear goals on complex and ambiguous tasks, learning to build relationships, balancing the internal focus on team cohesion with the external focus on managing stakeholders.” Work on cross-boundary projects fosters development of these and related teamwork skills. © Adept virtual work and teamwork: Since much of the work on cross-boundary projects will by necessity be done virtually, this know-how is also honed in this way. This includes knowing how to blend face-to-face and virtual communication effectively, building a rhythm in distributed work, and preventing obstacles from becoming self-fulfilling problems, THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE @ @ Dualistic thinking and global mindset: Working in split egg or matrix ways builds performance a dualistic sense of responsibility for both short- and long-term results, for is and innovation, and for local and regional or global results. This kind of experience manone of the key ways of developing a strategic global mindset in the most talented agers in a firm. a position One can safely argue that no one in a multinational organization should move into ch also of leadership responsibility without proven ability in cross-boundary teamwork—whi means accountability for getting results. People risk management the bigger the The flipside to the argument that people develop most through challenge is that go through career tranchallenge, the greater the risk of making costly mistakes. When people naturally rely on sitions, like the first move abroad or outside their area of expertise, they will overstressed, and skills and know-how they acquired in the past. They make mistakes, become the risk of burnout and make more mistakes. Taking on significant challenges also increases management—the second negative effects on personal lives. So what is needed is people risk g, mentoring, feedback, element of development—referring to support in the shape of coachin assessment, and training. expressed as the 70-20-10 In KONE, Nike, L’Oréal and numerous other companies, this is through feedback, coachprinciple: 70 percent of development happens on the job, 20 percent training. However, the last ing, and relationships with others, while 10 percent occurs through 30 percent makes a big difference! Training to minimize the risk of From the firm’s perspective, an important aim of transition training is to the challenge costly mistakes. This means that training has to be synchronous, closely linked people are available, of the new assignment or project. All too often, training takes place when Training that is even though this may be the worst time from the value-added perspective. other. Bosch, IBM, Shell, not linked to current experience largely goes in one ear and out the training. Toyota, and many other multinationals try to supply the necessary “just-in-time” scene—courses are Such “promote-and-then-develop” practices are changing the training designed and delivered shorter, and enrollments are decided at shorter notice. Often, they are job, and e-learning by outside contractors as modular programs that fit around the new also give people the may replace or support classroom training. Synchronous training may support. When people courage to take measured risks as they trust that they receive necessary there are usually move into new jobs, they often have a sense of what should be done, but Timely training can obstacles—a boss who will not back the change, peers who are hostile. boost an individual’s confidence to tackle these obstacles. annual spending on Leadership training is big business. US estimates have indicated that the But even well-designed leadership development and training may be as high as $50 billion.®* and educated training has its own risk. Many firms fear that with increased visibility, trained against investing in employees can easily be poached. Indeed, some economists even warn DEVELOPING TALENT @ cp generalized skills training and executive development programs because these increase an individual’s market value and ability to negotiate a higher salary. The consequence of this logic may be declining investments in internal development, with detrimental long-range consequences.” By way of contrast, research shows that investment in general-purpose skills may have a beneficial firm-specific effect by reinforcing employee commitment to the firm. This is clearly a difficult balancing act to manage. te Action learning Action learning is an explicit attempt to couple work on an important strategic challenge, typically a team project with members from different countries, with tailored support, training, and coaching for the team. There is usually a double aim—to tackle some important cross-boundary challenge and to develop the global leadership skills of high potential individuals. Action learning projects will usually report to high-level sponsors in senior management. Action learning differs from split egg team projects in that learning, rather than (only) the —_—_ Se quality of task delivery, is equally important. Framing the challenge as a “real” project intended to lead to tangible results helps both to support the learning on the part of the participants and the value of the project for the sponsoring unit. For instance, the task of a multinational team could be to improve the productivity of a local factory applying best practices from around the world, or even, as in LEGO, developing a new global leadership model.” A majority of company-specific training programs, whether in-company or outsourced to a business school, involve some degree of action learning. This requires training providers to have sophisticated skills in program design, blending classroom and action learning methods, including coaching and 360° assessment. It also requires proper buy-in from top managers involved in identifying suitable strategic challenges for action learning. ea _- = to Oo We — Coaching and mentoring One of the most important sources of development is relationships with other people—the positive and negative role models of good and bad bosses, internal or external coaches, and mentors.® Coaching often refers to the activities of an external professional who assists an individual or team in professional and personal development in a non-directive way, sometimes in connection with a formal training program. The experience of leading business schools is that the competence of good professional coaches comes from a combination of Management experience, training in psychological processes, personal insight, and acute sensitivity to others’ needs. The term “coaching” also describes a particular supervisory style that facilitates risk Management. As coaching has emerged as a key element in the kind of leadership behavior expected of superiors in many corporations, it is increasingly also seen as an integrated part of how firms approach performance management.“ With the right coach, this is potentially a good way of providing just-in-time risk management. Mentoring is sometimes grouped with coaching, although it is conceptually distinct. In mentoring, an experienced leader or professional is paired with a high potential person in a longer-term reciprocal relationship, as is the case at KONE. It is practiced widely and informally in professional service firms in the transition to the role of partner. However, it @ THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE can be difficult to organize formal mentoring relationships, partly because of the personal and emotional nature of such relationships and partly because the mentor’s contribution may not be visible. Professional organizations can encourage and reward mentoring by asking middle-level associates to identify mentors. This information is then publicized to highlight the contribution of those who are playing this important developmental role. Mentoring and “buddying” systems can take myriad shapes and forms. Companies where close links between technological and business skills are important sometime buddy up a HiPO duo for mutual development, where one person has a strong technical background and the other is commercially oriented. Cisco hooks up company veterans with managers from emerging markets who participate in talent acceleration programs.” Another multinational we know pairs up key sales managers in local countries with R&D managers at the headquarters, each acting as a host to the other. The relationship provides local sales managers with insight into the technical pipeline and allows R&D managers to scope and test out opportunities. IBM has long used shadowing (watching experienced managers at work and sharing their day-by-day tasks) as a way of grooming talented individuals. A survey of how 25 multinationals go about developing local leadership also shows widespread use of mentoring, with nearly two-thirds commonly using mentors—ideally more senior local people rather than expatriates.* Similarly, having a local mentor contributes significantly to expatriate success and knowledge sharing.” Feedback Providing timely, constructive, all-round feedback is one of the most useful facets of people risk management. Long standard practice in many firms, 360° feedback systems have typically been linked to development but are sometimes incorporated into performance management practices.” In the past, people argued that such feedback systems were culturally bound and would not function in, for example, an Asian setting. As discussed in Chapter 7, while cultural issues concerning feedback are important, our experience and research findings suggest that 360° approaches do work well there, as long as they are undertaken in a professional way and with strict adherence to the principles of anonymity.” PepsiCo uses 360° feedback as an integrated part of its Leadership and Development Program. The feedback tool is based on PepsiCo’s leadership competency model. Building on learning agility and self-awareness, its competencies include strategic mindset, smart innovation, talent development, global acumen, inclusive culture, collaboration beyond boundaries, and delivering the right results.” Hardship experiences Taking coaching and mentoring to an extreme may, however, effectively minimize any risk of failure so that people never learn to stand on their own feet and face up to tough situations. This leads us to a third element of development, dealing with business failures and mistakes or hardship experiences: learning to handle one’s feelings when faced with emotional traumas, building emotional resilience to deal with situations that are outside the comfort zone. While the risks of challenge must be managed, the real risk of failure must remain—a delicate duality. ~~ oS Ee DEVELOPING TALENT © Jensen Huang, co-founder and CEO of Nvidia—the US-based highly profitable maker of graphics chips—stresses the importance of the firm having an organizational culture of risk taking and learning from failure. But this is also an important feature when assessing candidates for leadership positions. He came to this viewpoint after working in a restaurant waiting tables. The job taught him how to deal with the chaos and the mistakes made when serving demanding customers during rush hours. When asked how he chooses individuals for leadership responsibility, never having experienced failure or hardship. Such HiPOs move so rapidly from one challenging assignment to another that they have to master only one part of the job—starting off new initiatives. There may be so much coaching and training that the risk of any failure is minimized. When such individuals ultimately move into the leadership post for which they have been groomed, for the first time they have to live with the consequences of whatever happens during implementation. And sometimes they experience a sense of failure or paralyzing uncertainty for the first time in their lives. Their training has never anticipated this, never equipped them to cope with failure. Some fall apart, experiencing a phenomenon that has been called “derailment”. The dark side of others’ personalities comes to the fore—the decisive leader who has learned to consult with others becomes a tyrannical autocrat, the cautious individual becomes compulsive on detail. Or arrogance fostered by past success leads them into undue risk.”4 Challenging assignments accompanied by risk management, together with the experience of coping with hardship experiences, are three basic elements of talent development. eas DEVELOPING POTENTIAL ae ae CO muy me Ee, OQ wn demanding positions, he explains: “I'll ask you about your greatest failures... What happened? How'd you deal with it?””? Sometimes being “high potential” is sufficient to guarantee a meteoric rise to a position of In the past, a simple logic guided the development of leadership potential in many leading multinational organizations: candidates for top positions should have experience in the home country, an established market abroad, and an emerging market. They should lead a manage- ment turnaround project to provide change management experience, as well as have experience in a headquarters staff role (often the most frustrating position) and in multiple business areas within the firm. But consider the implications. If potential was identified when employees were in their late twenties, and if these people were to move successfully into senior management no later than their mid-forties, this implied less than two years in each position. The consequence, as we discuss later in this section, was that people developed skills in starting things off but not in oy deep execution and the management of change. Today, firms are more selective in the way they frame the necessary development experiences. In its leadership principles, the beverage firm Anheuser-Busch InBev explicitly says that the type of challenges people experience is more significant than the function in which they © THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE experience them. AB InBev sees the best development experiences as coming from the following categories of challenging roles and activities: @ ® @ @ Assignments outside an individual’s own Commercial customer-facing experience, competencies deemed essential in its beer Roles in which leaders acquire experience of diverse people. Challenging expertise roles.” area of expertise. regarded as vital for developing brand-related business. in supervising and developing large numbers While in principle it is relatively easy to identity the kinds of tasks that would serve as good development opportunities for the individual HiPO, firms face a range of dilemmas in their leadership development activities. What underlies many of them is how to optimize both short-term performance and long-term development, seen clearly in challenges around decision-making on promotions and assignments. Blending demand-driven and learning-driven assignments When planning appointments, there are often real trade-offs between immediate performance, which argues for appointing a manager with the skills and experience required, and learning and development, which will mean nominating a HiPO individual who will learn from the experience. This is similar to the distinction between demand- and learning-driven international mobility discussed in Chapter 9. When a key position opens up in a unit, there will typically be a local functional candidate with many years of experience, a loyal and low-risk person who is sure to perform solidly. Anc there may be another candidate from the regional talent pool, an outsider to local operation: with less experience but who might bring new ideas and extraordinary results that would rock the boat, developing into a higher-level executive. Who should get the position? There are nc standard answers, though the preference of local management is usually clear. Unless there is a countervailing force in the shape of a strong regional HR manager who has the backing o: senior line management, the conclusion is foregone. Some observers describe (only partly ir jest), multinational leadership development as “guerrilla warfare”.”° Companies often find it particularly difficult to find positions abroad for learning-driver development. Headquarters may have the clout and legitimacy to find such assignments fo! home country employees with high potential—building on the traditions of expatriation However, finding developmental jobs in the US or Europe for talented staff from emergins countries is often difficult. ABB has dealt with this through norms of swapping—if you wan to send someone abroad, you have to be prepared to take in someone from outside. Focusing on A-positions as well as individuals Sustainable competitive advantage comes from building strong organizational capabilities tha are hard for others to imitate. Leadership development should therefore ensure that futur leaders acquire experience in domains regarded as key capabilities. For a beer company lik: DEVELOPING TALENT © AB InBev, this domain is brand management. This means that talent reviews should not only focus on the individuals—the so-called A-players—but also on the A-positions, the “strategic” jobs that are critical to a firm’s competitive advantage, as discussed in Chapter 6,” ted ers od \eir In tightly networked multinationals such as Nestlé, 3M, Unilever, and Japanese trading companies like Mitsubishi, the career of a HiPO oth ind Achieving the right amount of mobility or- Mobility is a powerful tool for ers will pursue careers within But there is a danger of taking mobility will compromise the ind arn 7en ate and ons ack no eis t of rin ven for ing ant employee will consist of a series of such A-positions, accentuating the development of firm-specific skills as well as generalist leadership—mastering networks, understanding the complex value chain, and confronting specific business and organizational challenges.” The flipside of this firm-specificity is that these individuals have fewer options at the same level of responsibility outside the firm should it become clear that their future inside is limited. Functional expertise travels well from firm to firm, but firm-specific, generalist experience has limited market value. leadership development, though bear in mind that most managfunctions, never moving outside them or their home countries. mobility and the associated learning to extremes. Too frequent ability to implement new initiatives—there is little that can be executed thoroughly in 18-24 months, especially at middle and senior management levels. After all, it is not (only) strategy and plans that count, but the quality of their execution. This is the reason why one should talk of mobility rather than “job rotation”. Especially in emerging markets with many career opportunities, rapidity of movement in some companies becomes a quasi-indicator of potential. This creates a zigzag Management pattern where newly appointed leaders of local units seek out initiatives that respond to the strategic intentions of senior management. Just as their local actions are taking hold, the individual is promoted and moved. If successors are cut from the same cloth, they will take their units off on different initiatives, since there are few rewards for implementing changes started by others. The consequence is that the front-line units go through periodic campaigns—cost cutting, customer orientation, time to market, and so forth—but never develop deep capabilities in any of these domains. Instead, the key to achieving the right amount of mobility should be to ensure that there is a clear link between accountability and tenure when planning assignments. If the assignment is learning driven, aimed at building experience, it is unlikely that the individual will be responsible for performance and capability building—the assignment can be of short duration, But if the assignment is demand driven and the individual is responsible for performance, then those assignments should be of longer duration, depending on the time it takes to ensure effective implementation. Succession planning or talent pools? hat ure like Succession planning consists of developing a plan to fill key positions as they become vacant. Succession planning is widely practiced in Europe, but less so in the US except at the most @ THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE senior levels; in Asia succession planning has mostly been used at operational levels because of the severe talent shortages that companies experienced during the boom years.” Succession planning has come under attack for being excessively mechanical. In reality, the decision about who gets the job is often made through informal discussion without consulting the succession plan, which is sometimes viewed by line managers as little more than a ritual of the HR function. Indeed, in flat organizational hierarchies, the decision to indicate person X as a likely successor for position Y may be somewhat arbitrary. Also, the requirements for a role may change after the original plan was agreed, or a new CEO may have different criteria for leadership appointments. When only some of the moves occur as planned, this may spill over into skepticism about the whole process of leadership development. In fact, in the US a majority of companies have abandoned all pretenses of succession planning,” Often, it has been replaced by designating talent pools, reservoirs of people with skills linked to critical organizational capabilities who can, in principle, be deployed across functions, businesses, and geographies. The typical scenario in many multinational firms today is that the local business unit is expected to engage in succession planning in its own interest, while the region or corporate level controls a talent pool of HiPOs. When a position becomes vacant, the local unit will propose its own successor, while corporate HR will consult the talent pool to see if there is a suitable individual who would benefit from the role and contribute to it. This leads to a review of who is the most appropriate candidate. Balancing top-down and bottom-up The approach to managing leadership development in multinationals needs to be at least partly top-down because of the “unnatural acts” that leadership development involves. But open-market, individual-driven, bottom-up approaches to talent management have been spreading over the last twenty years, often known as “open-job resourcing”. Multinational firms will have to pay increasing attention to striking the right balance between the two approaches, which we would argue are not mutually exclusive. Some major corporations, like Carrefour and Honda, did not have a corporate HR function until a relatively late stage in their history, when it was created to manage global leadership development. Honda’s founder, Honda Soichiro, believed that people management and marketing were so important that he did not wish to compromise line management’s responsibility by functionalizing them. However, Honda found it had to make an exception for leadership development. Without a dedicated role, functions and countries took local perspectives with too short a time horizon; leadership development took place within silos and without the necessary mobility. Until recently, leadership development in most multinationals was largely managed in a top-down manner. However, bottom-up elements are becoming more central to how many multinationals operate. Accelerated by the global standardization of HR processes and the development of e-HR technology, bottom-up approaches help deploy talented people and ideas across borders more effectively, rapidly, and cheaply than with conventional top-down DEVELOPING TALENT se of .the ting methods. The organization takes the prime responsibility for managing the careers of its stra- tegic talent through some form of talent management system. @ ‘son eria spill US has ical and it is tate will iere 3 to IBM, pioneer in this approach, created an e-platform that provides self-help in learning, networking, mentoring, tual . for @ ® career track management, and other elements of traditional top-down career management. The firm completely changed its former secrecy about its work strategy to one of internal transparency. Cisco’s internal job market worldwide is built around a “jobs can find you” principle, according to which people are expected continuously to look for job openings that correspond to their aspirations. These openings and the underlying strategy are transparent within the corporation, and people worldwide can apply for openings that most closely match their aspirations. In spite of the arguments in favor of a bottom-up approach, there are major obstacles to realizing these benefits. One of the far-reaching implications of open-job resourcing is that the responsibility for career development shifts from the company to the individual. But are the “right” individuals seeking out the available development opportunities? We witnessed one major multinational that abandoned its well-honed top-down management development processes that were correctly seen as somewhat ethnocentric, replacing them with global open-job resourcing. The outcome was predictable—few young talents volunteered for challenging assignments outside their areas of expertise, leading a decade later to appointments of untested leaders to positions with significant responsibility. Some passed, but others failed —with major cost to the business. Recently, the company corrected course— rast But 2en nal wo ion hip arrilup ith learning how to mix the top-down and bottom-up approaches to global talent management effectively. One additional reason why leadership development will continue in some degree to be top-down in multinational firms is that it is a powerful vehicle for global coordination. To facilitate a bottom-up approach, the coordination requirements must be explicitly built into career norms that are then rigorously followed. Let’s take an example of how this may work in practice. The firm specifies publicly that no one will get onto the management team in the commercial division unless they have proven themselves in at least one middle-level position for a reasonable period of time in the operations division—and vice versa, What are the consequences? First, the consequent mobility will develop a better quality of leadership since managers are obliged to hone their leadership skills via cross-functional moves. Second, it ensures that the leaders at the top have broad perspectives, the “matrix in the mind” that comes from assuming the responsibility for results in another discipline. Third, it builds social relationships between key people in the two disciplines, with the trust that will allow them to work through inevitable differences in functional priorities, And fourth, young professionals who want to move into leadership positions quickly learn that it is vital to be professionally competent in one’s base discipline, but also important to build networks and collaborate with other functions. Ifa company is to find and develop international talent for key corporate positions, talented locals need experience in challenging positions at the headquarters that will provide them with the relationships, the corporate perspectives, and the global mindset that will equip them for senior leadership positions. Without corporate-wide processes, the path to a truly @ THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE international supply of individuals for the most senior positions as well as “global- AND-local” organizational development will be inevitably slow—or non-existent. DEVELOPING THE WORKFORCE TO COPE WITH NEW CHALLENGES So far in this chapter we have focused on leadership development. This is of obvious importance to multinationals and to the individuals whose leadership skills are being honed. However, for societies, companies, and the single employee alike, a much broader perspective on employee development is needed. In a world where robots and algorithms are becoming central to how multinationals operate, there is a need for both upskilling (learning new skills, notably digital, that are necessary to improve performance) and reskilling (learning new skills for entirely new kinds of jobs) of significant parts of the workforce. In a 2020 survey of 119 000 HR and business leaders in 119 countries, 53 percent of the respondents said that between half and all of their workforce will need to change their skills and capabilities in the next three years to keep pace with digital and technology change.*! The case for re- and upskilling It has become fashionable to present prophecies of how many jobs will disappear and how many employees will have to be retrained in order to have the skills needed in the future. There are multiple causes of such skills imbalances. Given rapid technological change, the educational infrastructure in many countries cannot cope with the development of the needed skills. There are also impediments to the migration of talent from abroad that might compensate for demographic shortages—sectors of the population such as women are sometimes (at least partly) outside the talent pool; labor laws in some countries make it so difficult to fire people that employers are unduly cautious about hiring people; and especially where there is a shortage of digital skills, some firms may be reluctant to invest in training for fear that people will take those skills elsewhere to increase their pay. All of these together have a major impact on the competitiveness of countries, industries, and even individual firms, The box titled “Reskilling China” presents some central findings from a report published by the McKinsey Global Institute in 2021 on how the Chinese workforce will need to be transformed to meet future demands. After China opened up to the world in the late 1970s, the country transformed itself into an industrial powerhouse. During the last three decades, labor productivity has increased by 10 times and GDP by 13 times. During this period, the educational system has undergone a radical transformation. In 1978, two-thirds of children received compulsory edu- cation; today all children do. Enrollment in secondary education increased from 41 to 95 percent during the same time period. And college admissions increased from 3.7 million in 2000 to 9,1 million in 2019. However, the country is facing new challenges. Digitalization and automation are DEVELOPING TALENT cal” © reducing the demand for both repetitive manufacturing jobs and service jobs that require simple cognitive skills like data entry and validation. According to one estimate, 220 million Chinese workers may need to transition to another occupation by 2030. Going forward, there will be increased demand for jobs requiring higher cognitive skills, social and emotional skills, and technical skills. To date, education and training have largely relied on traditional face-to-face methods. Yet, China has an excellent chance of quickly increasing the use of digital learning tools, ored. ive ing Ils, ills )00 ialf The country is a forerunner in the use of many mobile applications, and Internet access is widely available. Large investments have recently been made in China’s educational technology sector; during 2019, China reportedly represented 56 percent of the global venture capital investment in EdTech, In spite of the recent crackdown on online teaching in China,” digital training solutions are likely to play important roles in the competence development that we will see taking place in China over the next decade, potentially reaching more than 900 million individuals through technology-enabled learning platforms. With the continuous evolution in digital technology, lifelong learning becomes an imperative, in China and elsewhere throughout the globe. ars ow re. che led n(at ire is dle ict Governmental action is needed both in developed and developing countries to ensure an appropriate supply of skills. But this takes time and may not always be directly targeted to specific business needs. Skills shortages are best dealt with when business develops partnerships with educational institutions and government or local authorities.“* Corporations can play an important role in both vocational and university education, being involved in the design of the content of the educational programs, contributing to the actual training by supplying experts as teachers, supplying concrete projects on which students can work, and offering internships for participants. Such programs can be made available both to students and to individuals who already are part of the labor market. Countries worldwide are increasingly aware of the need to invest in lifelong learning. Singapore has been a forerunner, with citizens being offered vouchers to spend on training courses that support skills development. The range of courses on offer is wide, and there is a range of providers, from educational institutions such as local universities, polytechnics and vocational schools as well as online course providers.® Corporate approaches to competence development 1S- Making sure that employees have the competencies needed firm successfully has always been a central element of a well strategy. New digital business models and the digitalization all industries have further increased the need to make sure to implement the strategy of the thought-out people management of work taking place in virtually employees have the right compe- tencies. If not, they will be unable to implement the transformations that most multinationals will have to go through in order to compete with more digitally savvy rivals. And the pandemic that hit the world in 2020 further accentuated the demand for broad skills development across large parts of the workforce. Most large multinationals have a separate unit within the global HR function responsible for its learning and development activities. The formal training activities and content are @ THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE delivered both face-to-face and online, through a combination of in-house and externally sourced content, and ranging from extensive management development programs running over several months to a rapidly increased number of brief e-based modules on specific topics that employees can carry out on an as-needed basis on their mobile devices. For instance, in 2018 Siemens had over a million participants enrolled in formal training, ranging from 3 650 graduates from 89 countries in its “Core Learning Programs”, 60 000 participants in standard classroom training offerings, to 835, participants in “E-Learning Rollouts”.* Corporations need to place strategy, and the capabilities needed to carry it out, at the core of their learning and development efforts. When Novartis developed its new strategy “to build a leading, focused, medicines company powered by advanced therapy platforms and data science”,” it identified five strategic priorities and pledged to invest US$100 million in learning and development over a five-year period. The stated aim was that all employees would spend 5 percent of their time on relevant learning, The professional services firm PwC, in turn, launched a US$3 billion investment in 2019 with a focus on digital upskilling. As a part of this initiative, all 276 000 employees worldwide underwent a two-day digital training session. Further, the firm initiated a variety of projects to digitalize processes and improve performance across the global organization.® So in the fast-changing world of the foreseeable future, companies need strong learning and development capabilities, especially if they count on the loyalty and commitment of the workforce—it is difficult to lay off staff in major countries where they operate; key labor markets are tight so people with the new required skills are either not available or are excessively expensive; and the failure to respond rapidly to technological and market shifts can threaten their future. With respect to upskilling, the capabilities rest on two pillars. One is the ability to assess proficiency and new requirements in key skill areas, such as the many facets of digitalization (virtual selling, digital marketing, business analytics, etc.). The second is the ability to design and roll out learning journeys customized to thousands of individuals around the world. These learning journeys will typically involve blended learning—combining online self-study with training programs supplied by alternative providers (corporate, external on-line providers, academic/vocational educational institutions), seminars and conferences, as well as govern- ment programs, all linked to on-the-job learning. Indeed, if the learning is not linked to the job, it will quickly be forgotten, as mentioned earlier. MANAGING RETENTION The major reason why many companies are reluctant to invest in the training and development of their people is that this increases their value—and the likelihood that they may leave.” Therefore, retention must be an integral part of people management. Firms that do a good job of recruitment and development but who manage retention poorly will have borne all the costs of people development, while letting other firms capture the benefits. Unfortunately, it is typically the most talented people, who firms can least afford to lose, who leave for higher pay and bigger opportunities elsewhere. DEVELOPING TALENT @ The effect of employee turnover is obviously more severe when the individual is central to the performance of the corporation. Firms like KONE have therefore introduced a set of indi- cators to identify, monitor and react to retention risks. There have also been efforts to develop models predicting the likelihood of somebody resigning from the company. Why do people leave and what can be done about it? The scholarly research on turnover and retention suggests that there are multiple reasons for attrition,” and there is a large body of practitioner literature on the reasons why people leave a firm.”’ With this in mind, let us review some of the implications for managing retention. 1, Compensation: When asked in an exit interview about the reasons for leaving the organ- ization, most people will say that they are getting a higher wage packet in their new job. But this does not necessarily mean that higher compensation is the solution to retention. Experienced HR professionals will someone to look outside in the first of clear development opportunities, if talented individuals are prepared point out that typically it is not money that leads place but some other cause for disgruntlement—lack a difficult boss, or problems in work-life balance. And to change jobs and organizations, they will invariably gain an increase in compensation. Raising salaries across the board to solve retention would only price the company out of business. It is important to consider all aspects of the employee value proposition (as discussed in Chapter 6), of which compensation is only one element. Nonetheless, compensation still matters and there is also some research evidence suggesting that pay has become a stronger predictor of voluntary turnover.” To retain strategic talent using compensation as a carrot, it is vital to know how employees view the local job market opportunities in comparison with the global salaries of HiPOs (see Chapter 7). Stock options and retention bonuses may be effective in boosting retention in countries where it is possible. People may leave after their options are exercised, but this, at least, is predictable. Financial penalties can sometimes be used to discourage unilateral resignations. For example, employment contracts that include retention bonds are widely used by the public sector in Singapore to retain employees who have benefited from education or training support from the government or the employer. The aim is to ensure that they remain with the sponsoring organization for a prescribed period of time to secure a return on the development investment. In the private sector, such contracts, while not uncommon, are 2. difficult to enforce. The quality of the relationship with the boss: Line managers are responsible for many areas of potential dissatisfaction contributing to turnover, associated with coaching, providing feedback, giving recognition, and offering growth opportunities. The boss also plays a critical role in other dimensions of retention management, such as work-life balance, where the superior typically has considerable discretion, regardless of corporate policy and practice. Indeed, much of the problem of turnover lies in the hands of the direct supervisor. A popular way of expressing this is the aphorism that “people don’t leave companies, they quit bosses”. This is one reason why multinationals invest in supervisory training—the benefits of improved retention as well as employee engagement typically more than outweigh the cost. @ THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE One of the contentious issues in retention management is that line managers may see it as the responsibility of the HR function, with its role in compensation and benefits, while HR professionals want line managers to take the prime responsibility for retention. However, creating a talent mindset where line managers accept that they must pay attention to sub- ordinates can be difficult. This is true even in North America, where it is now common that senior managers at least have retention objectives among their key performance indicators. If the firm has an internal job market that allows employees to apply freely for other internal positions, the boss is obliged to pay attention to actions, such as listening to staff, that will increase the engagement and loyalty of key subordinates. Half of companies in the US allow employees to apply for another internal position without permission from the boss.” But creating this talent mindset can be more challenging in the environment of 3. emerging countries, like China, where bosses often have an eye on the door themselves and are not used to considering people management as part of their role. Indeed, they may take their best performers with them when they leave! Work-life balance: The biggest source of work dissatisfaction suggested by the opinion surveys of many leading multinationals is poor balance between professional and private life, often voiced by the millennial generation of young professionals. One caveat to note here is highlighted in the research of one of the authors, based on 14 000 predominantly male managers across the globe, which showed that perceived work-life imbalance may hide other problems, notably different types of mismatch between the job or company and the individual.” In contrast, individuals who thrive on their jobs and work environments will often live with their work-life dissatisfaction for protracted periods of time. In order to retain talent, companies respond with a range of work-life programs to juggle work and family commitments, as well as child-friendly working practices. Infosys successfully tackles retention with a group of workplace initiatives—including family involvement—that mimic the best aspects of university life> Much of the work within multinationals was virtual already before the COVID-19 pandemic, with obvious challenges such as how to find time for meetings among project members located across widely different time zones. Thoughtless practices—such as Friday afternoon conference calls, New York time, which compromise the weekend for those in Asia—should be eliminated. 4, Personal growth opportunities: In rapidly growing markets, such as China or India, outside career opportunities that offer not only better compensation but also a significant increase in responsibility are a major cause of turnover. Often, talented employees can move quickly from local or regional jobs to positions with global responsibilities—for example, with aspiring local multinationals. A temporary remedy may be an opportunity to participate in a significant global project, or adding coordinating responsibilities that provide visibility with senior management. Coaching and mentoring are other tools to counter this inevitable problem. 5. Talent development: In the long term, people will only stay if they feel the organization has no “glass or bamboo”” ceilings and that they get a fair chance to prove (and enhance) their skills. Therefore, a transparent structure for talent development that is clearly based on performance and potential is a critical tool for combating attrition. In multinational firms, this means establishing positive role models for local staff. The perceived lack of development and career opportunities contributes greatly to attrition, especially among talented local individuals, If local employees are unsure of their future in the firm, particularly when they see senior jobs going first and foremost to expatriates, they will naturally DEVELOPING TALENT 6. @ keep a close eye on outside opportunities. But this is also true of firms in the US, where senior positions are often filled by outsiders. Location: It may be easier to recruit people in talent cluster locations like the San Francisco area for the IT industry, the north of Italy for the fashion industry, or in urban conurba- tions such as Shanghai and Sao Paulo. But it is also easier for other firms to poach talent in such places. The people management strategy of software firm SAS focuses on providing generous employee benefits and a highly congenial flexible work environment—but it is located in North Carolina, far from the technology hub on the Pacific coast. Their attri- tion rate is low in an otherwise volatile industry and this stability gives SAS a competitive advantage over its competitors, where many members of software development teams are either learning the ropes or looking for opportunities elsewhere. Companies may be able to choose secondary locations where it is easier to socialize and retain talented individuals (such as Vietnam rather than China). Overall, there is no simple recipe for employee retention in all contexts, which is why this matter must be high on the agenda of talent reviews focused on technical as well as managerial leadership in all regions of the multinational enterprise. Multinationals who do a poor job in retaining talent will not only see their global investments in human capital walk out of the door, but also suffer in terms of their ability to coordinate and develop their cross-border operations. As discussed throughout this book, it takes time to build the soft human capabilities that facilitate coordination, along with innovation and agility. TAKEAWAYS 1. Tolerance for ambiguity, the ability to work with contradictions, strong interpersonal skills, and the ability to exercise leadership without authority are key global leadership competencies. Yet, leadership is intransitive—the best performer at one level is not necessarily the best performer at the next. 2. At the heart of the traditional top-down approach to leadership development are rigorous reviews of talent in different parts of the firm, typically based on past performance and potential. A key element of potential is learning agility—the ability to learn fast and well from challenging experiences; and purpose-driven behaviors are becoming vital for sustainability, as explored in Chapter 14. 3. Central dilemmas in leadership assessment and development are: how to identify talent regardless of location, whether potential should be identified early or late, and how transparent should firms be about their assessments? 4. Above all, leaders develop through challenging opportunities and assignments, such as those that involve mobility across countries and functions and split egg type cross-boundary 5. 6. projects. Challenges have to go hand in hand with people risk management—coaching, mentoring, feedback, and training to minimize both the risk of mistakes and to help people recover from them, In managing leadership development, firms should focus on the key strategic A-positions as well as on the A-players, striving to match the two. THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE 7. 8. Facilitated by e-technology, there is a trend to push the responsibility for development to the individuals themselves, supported by internal job markets. But a key purpose of potential identification is to ensure that HiPOs undertake challenging assignments, something that often would not happen without top-down intervention. Re- and upskilling of multinational workforces is a key part of a comprehensive people management strategy and also prepares people for lifelong learning. 9, Attrition occurs due to people leaving for higher pay, but they are often spurred to leave by poor relationships with the boss, work-life imbalance, and perceived lack of development opportunities. 10. Mobility, split egg assignments, coaching and other developmental actions can be undermined if careful attention is not paid to retention management. NOTES The case description is based on Smale and Bjorkman (2020). As is common in firms in the Nordic countries, Emerging Leaders and successor candidates at KONE are told about the LTR process, but corporate policy has for a long time been that they are not officially informed about the outcome of the workshops in terms of their status as an identified Emerging Leader or successor. However, this information has been shared with an employee if they submit an official personal data request. Our definition is similar to the definition of global leadership presented by Reiche et al. (2017a). There are numerous views of what constitutes traditional leadership behaviors, For instance, the model of leadership used by INSEAD’s International Global Leadership Centre is built around four leadership behaviors: Directing (Where are we going?); Enabling (How are we going to get there?); Motivating (Dealing with obstacles underway); and Coaching (Developing others and oneself). Ready et al, (2020). Ready et al. (2020), The paramount importance of purpose-driven leadership with appropriate values is vital for sustainability, as discussed in Chapter 14. Ibarra and Scoular (2019). Ibarra and Scoular (2019). Bird and Mendenhall (2016). 10. Osland (2018). 11. Dorfman et al. (2012). 12. Maruca (1994, p. 142). 13, Mendenhall et al. (2012). 14, For reviews of this literature on global leadership competencies, see McCall and Hollenbeck (2002); Caligiuri and Tarique (2012); Bird (2018). For a broad overview of the global leadership literature, see the volume edited by Mendenhall et al. (2018). 15, Hollenbeck and McCall (2001). 16. Maddux and Galinsky (2009); Maddux et al. (2009). This is discussed further in Chapter 10. 17. Javidan et al. (2021). 18. The Peter Principle suggested that employees will rise in a hierarchy until they reach their level of incompetence (Peter and Hull, 1969). It is a notion today captured popularly in Dilbert cartoons.