Statutory Interpretation in Zambia: Mischief Rule & Purposeful Approach

advertisement

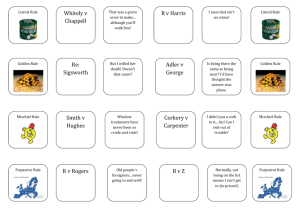

Mischief Rule and the Purposeful Approach to statutory interpretation in Zambia by Michael Mauzeni INTRODUCTION The purpose of this essay is to critically discuss the notion that it is trite law that the primary rule of interpretation is that words should be given their ordinary, grammatical and natural meaning. It is only if there is ambiguity in the natural meaning of the words used by the legislature that recourse can be had to the other principles of interpretation. To begin with, a basic description of statutory interpretation shall be given, followed by an analysis of the rules to statutory interpretation. Based on the points raised, a conclusion shall be made. STATUTORY INTERPRETATION THE DIFFERENCE WITH AN ILLUSTRATION OF AID OF DECIDED CASES AND HOW THE TWO RULES OF STATUTORY INTERPRETATION HAVE BEEN APPLIED IN ZAMBIA AND OTHER COUNTRIES. In fulfilling their task of applying the law to the facts before them, the courts frequently have to interpret (i.e. decide the meaning of) statutes through a process referred to as statutory interpretation.1 “Statute law is the will of the legislature; and the object of all judicial interpretation of it is to determine what intention is either expressly or by implication conveyed by the language used”2. There are a number of rules relating to statutory interpretation, however, these rules cannot be applied simultaneously. According to the literal rule, statues should be understood in there plain, natural or ordinary meaning of words. Judges normally bind themselves by the words of the statutes when these words clearly govern the situation before the court as words are applied with nothing neither 1 M. Woodley, Osborn’s Concise Law Dictionary (10th ed.), London: Sweet and Maxwell, at 382 (2005). 2 P. B. Maxwell, The Interpretation of Statutes (6thed), London: Sweet and Maxwell, at 1 (1969) 1 added nor subtracted3. As noted by Tindal CJ in theSussex Peerage case4, if words are precise and unambiguous, then they must be construed in their natural or ordinary meaning in accordance with the intent of the legislature who passed the act. Advocates of the literal rule claim that it results in quick decision making, respects parliamentary supremacy because a judge’s function is to apply the words of Parliament and not to make law and most notably it prevents courts from taking sides in legislative or political issues as Judges are afraid of being accused of making political judgments at variance with the purpose of Parliament when it passed the Act. For example, Mambilima, J. applied the literal interpretation in making her judgment regarding provisions of Article 71 (2) (c) of the 1991 Zambian Constitution regarding floor crossing in order to refrain from taking sides.5 Despite being the first rule to statutory interpretation, this seemingly uncomplicated principle may be very difficult to apply in practice as it is liable to lead to difficulties. For instance, use of the literal rule may defeat the intention of the legislature. As the literal rule does not take into account the consequences of a literal interpretation, only whether words have a clear meaning that makes sense within that context. In Whiteley v. Chappel6, the appellant was charged with impersonating a dead man to obtain an additional vote in an election. The court held that despite the relevant legislation making it an offence to impersonate any person entitled to vote. Since a dead man wasn't entitled to vote, impersonating him couldn't be an offence, hence, the defendant could not be convicted. Furthermore, a difficulty in this rule may arise largely due to lack of linguistic clarity as some words have several meanings and this opens the possibility of alternative interpretations like that in R v Maginnis7, the defendant was found by police to have a prohibited drug, cannabis, in his car. He claimed that the package had been left in his car by a friend for collection later. Problems were caused by the word supply, as did temporarily holding drugs on someone else's behalf' to return them later amount to an intent to supply as proposed by the relevant statute. In some circumstances, even if a word does have a precise explanation, strict observance to its 3 4 5 6 7 M. M. Munalula, Legal process: Zambian cases, legislation and commentaries. Lusaka: UNZA Press, at 166 (2004) (1844) 11 CI & Fin 85 Attorney General and Movement for Multiparty Democracy v AkashambatwaMbikusitaLewanika and others SCZ Judgment No: 2 (1994) (1868) LR 4 QB 147 (1987) 1 All ER 907 2 literal meaning may lead to a contradictory outcome. In R v Harris,8 the defendant bit her friend, the prosecution alleged the bite was included in stab, cut or wound. But the Court held that it was evidently the intention of the legislature, according to the words of the statute, that the wounding be inflicted with some instrument, and not by the hands or teeth; hence the defendant was not guilty. When the application of the literal rule proves unsuitable the court may decide to resort to use another, the golden rule. The basis of this principle is founded in the expression of Baron Parke in Grey v Pearson9, "the ordinary sense of the words is to be adhered to, unless it would lead to absurdity, when the ordinary sense may be modified to avoid the absurdity but no further." Therefore, the golden rule requires that the literal rule should be applied to the statute in the first instance, but that if the literal rule results in an ambiguity or absurdity the court should try to interpret it in another manner so as to avoid the ambiguity or absurdity. 10In Attorney General and Movement for Multiparty Democracy v AkashambatwaMbikusitaLewanika and others,11 as a result of applying the literal rule in interpreting Article 71 (2) of the Zambian Constitution, the High Court protected floor crossing of the particular situation at hand. On the other hand, the Supreme Court established that there was a void in that article which did not cover the situation which was deemed not only to be unfair and unreasonable but also to be against Article 23 which prohibited discrimination. As a result, the Supreme Courts judgment was subject to interpretation based on the golden rule in line with the words of Lord Denning who proposed that “Whenever strict interpretation of a statute gives rise to absurdity and unjust situation, the judges can and should use their good sense to remedy it by reading words in, if necessary so as to do what parliament would have done had they had the situation in mind”12. However, application of this rule is subject to the difficulties that have been end”. The golden rule permits the court to select the meaning which would led to the most rational result in circumstances where both the sensible and absurd meaning are linguistically possible which does not really contravene with the literal rule. As illustrated in R v Allen13, the court noted that there were two primary connotations of the word marry. The first involved a legal 8 (1836) 7 C & P 446 (1857) 6 HL Cas 1 M. M. Munalula, Legal process: Zambian cases, legislation and commentaries. Lusaka: UNZA Press, at 176, (2004). 11 SCZ Judgment No. 2 of 1994 12 Nothman v Barnett Council (1979) 1 HLR 220 13 (1872) LR 1 CCR 367 9 10 3 commitment to another person while the other referred to involvement in a ceremony. It was noted by the judges that the first meaning would create an ambiguity since the second marriage would be void, it would be not possible to commit bigamy in a criminal sense. Therefore, the court was prepared to read marry as to go through a ceremony of marriage. In contrast, when the meaning of a word would result in a ridiculous or repugnant outcome, the court will use a broader view. In Re Sigsworth14, the court was asked to consider whether a son who murdered his mother could inherit her property. MrsSigsworth did not leave a will but her son was entitled to the inheritance by virtue of Section 46 of the Administration of Estates Act 1925. However, the courts were not prepared to allow this to happen, application of this rule made it possible for the court to decide that murderers should not be permitted to inherit from their victims. Consequently, the golden rule has been suggested to be a “little more than a safety-valve to permit the courts to escape from some of the more unpalatable effects of the literal rule. It cannot be regarded as a sound basis for judicial decision-making.”15 Therefore, in avoiding absurdities by modifying existing law, the courts tend to challenge the supremacy of the legislature, that is, parliament, by amending laws. Another alternative used by courts to make decisions of sound basis is the mischief rule. This approach allows them to look at the common law before the act followed by the mischief that the statute was intended to remedy. Therefore, the Act is then to be construed in such a way as to suppress the mischief and advance the remedy.16 This rule otherwise known as rule based on Heydons case17focuses on the social and political climate in which legislation came into existence and pays less attention to the literary meaning of the text. Based on which Judges should make such constructions on the Act to suppress the mischief and subtle inventions and evasions for continuance of the mischief, according to the true intent of the makers of the act. As exhibited in Smith v Hughes18, the defendant, a prostitute, solicited her clients from balconies and windows in order to evade prosecution contrary to the 14 (1935) Ch 89 M. Zander, The Law Making Process (6th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (1994). 16 M. M. Munalula, Legal process: Zambian cases, legislation and commentaries. Lusaka: UNZA Press, at 167 (2004). 17 (1584) 3 Co. Rep 7 15 18 (1960) 2 All ER 859. 4 law. The court held that the purpose of the legislation was to reduce prostitution and to protect the public; consequently, soliciting from balconies, doorways or windows was held unlawful. But in contrast to the aforementioned case, in DPP V Bull19, The court held that the word prostitute was limited to female prostitutes and therefore was not applicable to a man who had been charged with loitering or soliciting in a street or public place for the purpose of prostitution, as a result, the defendant was not convicted. Despite the mischief, that is, prostitution, being similar in both cases, the outcomes were totally parallel, which is a revelation that the mischief rule may at times be contradictory in itself. Furthermore, from the aforementioned case, it can be noted that correspondingly to the golden rule, despite having the intention to act in accordance with the intention of parliament, application of the mischief rule by judges may cause them to deviate from what the law actually requires. The court erred in its judgment by ruling that a prostitute was limited to females as opposed to males. However, application of the mischief rule is not always guaranteed even when the mischief is clear, and it would be plainly sensible to do so. In Fisher V Bell20, the prosecution of a shopkeeper for displaying flick-knives for sale failed because of the wording in the Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act of 1959 which used the term offer for sale. Displaying goods in a shop is widely understood not to form an offer for sale in such terms as it is merely an invitation to treat. The court could not find according to the clear intention of Parliament, and rejected to apply the mischief rule. A difficulty that arises from the literal rule is that despite words having a fixed meaning, some words have several meanings and this opens the possibility of alternative interpretations.21 Hence, the Fringe Meaning rule is applied. In Attorney General V Stephen Luguru22, after his request to buy a government house (as he was a sitting tenant) was rejected, the respondent a Tanzanian national employed in the Zambian civil service, brought an action in the lands tribunal which succeeded ordered the sale of the house a decision which was appealed. The court held that despite being a sitting tenant, the respondent was not entitled to the house as the intention of the Government was to empower Zambians to own real property through the Civil Service Home 19 (1994) 4 ALL ER 411 [1961] 1 QB 394 21 M. M. Munalula, Legal process: Zambian cases, legislation and commentaries. Lusaka: UNZA Press, at.166 (2004). 22 SCZ Judgment No. 2 of 2001 20 5 Ownership Scheme as declared in the preamble of the handbook. Hence in this instance, the meaning of the sitting tenant was pointed out to mean a Zambian. Conversely, this rule has been criticized in light of circumstances such as one illustrated in the aforementioned case, as judges involuntarily become legislators23 as they bind themselves to words either by narrowing or broadening the extent of application which may undermine the supremacy of parliament but also at certain circumstances deviate from the intention of the legislative body. Another alternative to statutory interpretation is the context rule. This rule based on the latin maxim, noscitur a sociis, that is, a word is known by the company it keeps24. This suggests that words of a statute are to be construed in the light of their context. Furthermore, judges should give effect to the ordinary (or technical where appropriate) meaning of words in context of statute by determining extent of words by the context of the act. As demonstrated in Mudenda v Attorney General25, the appellant was detained under the Preservation of Public Security Regulations for trafficking in illicit minerals ‘like emeralds’. However, it was contended by the appellant that the grounds for detention was unlawful as the words ‘like emeralds’ were too general, vague and imprecise. However, the court ruled that the context of the word like referred to ‘same as’ or ‘similar to’, hence, the usage of like emeralds could only refer to emeralds and diamonds which were illegal; for this reason, the detention order was warranted. Consequently, as proposed in several other rules, the context rule may be inadequate as the courts may deviate from the intention made by the legislature. Furthermore, by trying to establish the intention of the legislature, the court may apart from considering the act in whole to understand the context in which a word or expression is viewed, may also examine other aids such as parliamentary debates, reports and many others. Hence this may delay the delivering of judgment as illustrated in R V G and another26, where in trying to establish in what context did parliament refer to when using the word ‘reckless’, the House of Lords extensively explored the context in which the word was used. 23 M. M. Munalula, Legal process: Zambian cases, legislation and commentaries. Lusaka: UNZA Press, at 166 (2004). M. Woodley, Osborn’s Concise Law Dictionary (10th ed.), London: Sweet and Maxwell, at P. 279 (2005) 25 (1979) ZR 245 26 (2003) HL 50 24 6 Additionally, statutory interpretation permits the application of certain presumptions which are restrictive and negative in character. It is further suggested that the presumptions are the legal principles that were the standard upon which parliament used in making the law and in which the act must be viewed without being actually explicitly stated27. The use of presumptions was demonstrated in The People v Bright Mwape and Fred Mmembe28, where it was disputed that Section 6929 of the Penal Code in relation to defamation of the president was unconstitutional as it contravened with Article 20 and 23 of the Zambian constitution which the court ruled against. CONCLUSION, The legislature drafts acts in such a way to minimize the amount of interpretation that is necessary by the courts of law. However, in circumstances where there is uncertainty, judges are to act freely in an objective manner to make decisions in accordance with the intention of parliament. Where the meaning of words is plain and unambiguous, they are not allowed to select the most convenient rule of statutory interpretation, they must apply first the literally rule and only if this leads to illogical consequences, then judges can consider the purpose of the legislation as the court utilizes whichever of the rules which produces a result that is satisfactory in regards to the case before it as it may be impossible to predict with certainty which approach to adopt. 27 M. M. Munalula, Legal process: Zambian cases, legislation and commentaries. Lusaka: UNZA Press, at 194 (2004) 28 SCZ Judgment No. 4 of 1996 29 Section 39.(1) Where any person is convicted of an offence by a court and at the date of such conviction he has not been sentenced under a prior conviction or his sentence under a prior conviction has not expired, then any sentence imposed by the said court, other than a sentence of death or corporal punishment, shall be executed after the expiration of the sentence imposed under the prior conviction, unless the said court otherwise directs. 7 REFERENCES Maxwell, P. B. The Interpretation of Statutes(12st ed.), London: Sweet & Maxwell, (1969). Munalula, M. M.Legal Process: Zambian cases, legislation and commentaries, Lusaka: UNZA Press, (2004). Woodley, M., Osborn’s Concise Law Dictionary, (10th ed.), London: Sweet & Maxwell, (2005). Zander, M., The Law Making Process, (6th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (1994). STATUTES The Criminal Procedure Code Act Chapter 88 Of The Laws Of Zambia The Penal Code Act Chapter 87 Of The Laws Of ZambiaMinistry Of Legal Affairs, Government Of The Republic Of Zambia Constitution of Zambia 1991(As amended by Act No. 17 of 1991) CASES Attorney General v Steven Luguru SCZ Judgment No. 2 of 2001 Attorney General and Movement for Multiparty Democracy AkashambatwaMbikusitaLewanika and others, SCZ Judgment No. 2 of 1994 DPP v Bull (1994) 4 ALL ER 411 8 v Fisher V Bell (1961) 1 QB 394 Grey v Pearson (1857) 6 HL Cas 61 Heydons case (1584) 3 Co. Rep 7 Mudenda v Attorney General (1979) ZR 245 Nothman v Barnett Council (1979) 1 HLR 220 R v Allen (1872) LR 1 CCR 367 R V G and another (2003) HL 50 R v Harris (1836) 7 C & P 446 Re Sigworths (1935) Ch 89 Smith v Hughes (1960) 2 All ER 859 The People v Bright Mwape and Fred Mmembe SCZ Judgment No. 4 of 1996 The Sussex Peerage Case (1844) 11 CI & Fin 85 Whiteley v Chappell (1868) LR 4 QB 147 9