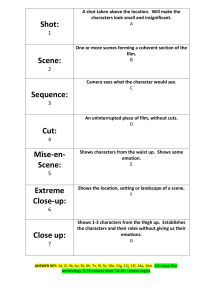

Basic Film Production Matthew T. Jones Film as a Medium Supplementary Notes Production Phases There are three phases of production common to most professionally produced motion pictures. These are: • Preproduction phase • Production phase • Postproduction phase Preproduction Phase In general, the preproduction phase encompasses all aspects of preparation that are performed before the camera starts to roll. Some aspects of preproduction include: • • • • • • • • • • Screenwriting Storyboarding Funding Assembling a crew Casting Costume Design Location Scouting Set Design Properties (“props”) Scheduling Preproduction Phase Screenplay/Script: The screenplay supplies the general plan for the production of a film. There are two types: • The “spec” script • The “shooting” script Preproduction Phase The “Spec” (Speculation) Script is the version of a screenplay that writers distribute to producers in the hope that it will be “optioned” (i.e. considered for production). It primarily contains: • • • Slug-Line (brief description of the setting, e.g. “INT. ROOM – DAY” which means the interior of a room during the day) Business (descriptions of characters/action) Dialog (the lines intended to be spoken by the actors) Preproduction Phase The Shooting Script is a much more detailed version of the spec script that includes numbered scenes, specific camera angles and other technical information. An example of a page from a shooting script (from the film Pieces by Andrew Halasz shot here at William Paterson) can be seen on the next slide. Preproduction Phase Writing a screenplay and analyzing a film narrative require an awareness of similar concepts: • Character • Conflict • Action • Story • Plot Preproduction Phase Character • Agent of physical and social action • Subject to physical and social action • Subject to needs and desires • Subject to social norms, mores, and laws Preproduction Phase In an instructional book on screenwriting, Syd Field (1979) divides character into interior and exterior aspects. Viewers of a film don’t have access to the character’s interior life and so it must be expressed in the exterior life through actions taken in professional, personal, and private contexts. One pursuit of narrative analysis is the interpretation of character motives based on action. Preproduction Phase Preproduction Phase Conflict • The source of narrative conflict is the needs and desires of the character when they are met with oppositional forces. There are three basic types of narrative conflict: • Character versus Nature (i.e. the physical world) • Character versus Character • Character versus Self Preproduction Phase Action • In a film narrative, a character is expressed through his/her actions in responding to a conflict. Two overlapping types of character action are: • Social Action (e.g. dialog, communicative behavior) • Physical Action (e.g. stunts, athletic behavior) Preproduction Phase Storyboarding: A storyboard is a series of drawings intended to represent how the film will be shot, including how each frame will be composed and how subject and camera motion will occur. • The storyboard articulates the mise-en-scene of the film. • Mise-en-scene: All of the elements that compose the shot. Preproduction Phase Funding: Films are generally expensive to produce. Even small independent productions with unknown actors can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Because of the level of investment involved, most films rely on either production companies (“Hollywood” films) or independent investors (“Independent” films). Preproduction Phase Assembling a Crew: A crew is the group of workers on a film set who are responsible for facilitating production (as opposed to acting). Although large productions may employ many crew members in many different departments, there are only a few basic positions which are detailed later in the production phase. Preproduction Phase Casting: Choosing actors to play roles. Costume Design: Choosing or designing the clothing/costumes that the actors wear. Location Scouting: Choosing the locations where the film will be shot. Set Design: Constructing sets where the film will be shot. Preproduction Phase Properties (“Props”): Choosing the tools and objects used in the film. Scheduling: Coordinating all aspects necessary to the production. Production Phase The production phase refers to the period of time when the film is actually being shot. Some aspects of production include: • • • • • Direction Camera operation Lighting Sound recording Acting Production Phase During production, these roles are usually delegated to the production departments listed on the next two slides. Production Phase Production Departments • • • Direction • • Director (oversees all aspects of the production) Assistant Director (works closely with the actors) Camera • • • Cinematographer (oversees camera operation and lighting plan) Camera Operator (operates the camera) Assistant Camera (loads camera, pulls focus) Lighting • • • Cinematographer (oversees camera operation and lighting plan) Gaffer (head electrician) Grip (sets up lights) Production Phase Production Departments (continued) • Sound • Talent • Miscellaneous • Sound Mixer (records the sound) • Boom operator (positions the microphone) • Clapper (displays the clap slate for the camera) • Actors (perform before the camera) • Production Coordinator (scheduling) • Continuity “script girl” (watch for continuity errors) • Make-up Artist (apply make-up to actors) • Production Assistant (various jobs) Production Phase All of the departments and positions described on the last two slides serve one goal: to capture the sound and image necessary to tell the story. Although going into every detail of production is far beyond the scope of this course, let’s consider the “nuts and bolts” that go into filmmaking. Production Phase How does the camera work? • When we are watching a motion picture, we • are actually watching a rapid series of still images that are projected in rapid succession on the screen. We are able to perceive motion in a film because of the cognitive/perceptual phenomenon known as persistence of vision. Production Phase How does the camera work? • The motion picture camera is a tool used to rapidly expose a continuous series of film frames to light that is reflected off of objects and focused onto the film by the camera’s lens. The following three slides display diagrams of the inside of a basic motion picture camera. Production Phase How does the camera work? • As you can see, the film makes its way from the spool into the loop and through the gate. The aperture in the gate is a small square hole that allows light to pass from the lens onto the focal plane of the film. This process is represented in the diagram on the left of the next slide. Production Phase How does the camera work? • Once light has been focused by the lens, the camera shutter opens. The shutter is shaped like a revolving disc and it’s function is to allow a single frame of film to be exposed to light ONLY when it is completely motionless inside the gate. This normally occurs 24 times per second. See the following slide for shutter operation. Production Phase How does the film record the image? • In the instant that the shutter opens and closes, exposing the film frame to light, a chemical reaction takes place on the surface of the film. The coating of emulsion, which is composed of light-sensitive silver halide, is burned away in various degrees (depending on the intensity of the light) leaving behind a “latent image” that is revealed once the film has been processed. The following two slide illustrates this. Production Phase Shot / Mastershot The 180 degree rule. Production Phase Now that we understand the basic mechanism, let’s consider some of the ways that it can be manipulated during production: • Types of shots • Types of angles • Lens choice • Movement • Lighting Production Phase Types of Shots • There are four basic shot types that are based on the apparent proximity of the subject. • Long shot • Full Shot • Medium shot • Close up shot Production Phase Types of Shots • The Long Shot (a.k.a. Establishing Shot) • In the most pragmatic sense, long shots can be used to establish a location, acquainting the viewer with the onscreen space so that the sequence of shots that follow is not disorienting. • Long shots can also be used to suggest a wide variety of meanings such as isolation, loneliness, freedom, emotional distance, and more. (Note that interpreting any particular shot or sequence of shots is dependent upon the context of the film.) Production Phase Types of Shots • Full and Medium Shots • Full shots include the entire body of a subject from top to bottom while medium shots generally include the body from the waist up. • Full and medium shots tend to mimic our point of view when we are engaged in a social encounters. Production Phase Types of Shots • The Close-Up Shot • Close-up shots capture a single object, or feature within the frame. They are commonly used to reveal subtleties and/or create a sense of engagement or intensity. Production Phase Types of Angles • There are three basic types of angles which refer to the position of the frame with respect to the subject within the frame. • High Angle • Low Angle • Straight-On Angle Production Phase Types of Angles • High Angle • A high angle shot refers to a camera position where the lens aims down at the subject from above. An extreme high angle is sometimes referred to as “bird’s eye view.” • High angles can be used to reveal the layout of a room or to make a subject appear weak and small. As mentioned previously, however, the context of the scene and the larger film must be taken into account prior to interpretation. Production Phase Types of Angles • Low Angle • A low angle shot refers to a camera position where the lens aims up at the subject from below. • As opposed to the high angle shot, the low angle tends to make the subject appear intimidating and powerful. Again, the larger context of the film must be accounted for. Production Phase Types of Angles • Straight-On Angle • A Straight-On shot refers to a camera position where the lens is aimed directly at the subject. • Especially when used in conjunction with the full or medium shot, this angle mimics our point of view in a social encounter. Production Phase Lens Choice • • The only function of a lens is to focus the light that is either projected or reflected from the surrounding environment onto the focal plane of the film. However, lenses come in a variety of focal-lengths which make the depicted scene appear at different distances. There are three basic types of lenses: • Telephoto lens (a “long” lens) • Wide angle lens (a “short” lens) • Normal lens • Zoom lens The image on the next slide shows the basic function of a lens. Production Phase Lens Choice • Lens choice is guided by two primary and strongly related factors: • Focal Length: The distance perspective of the lens. • Depth of Field: The range of distance that can focused in front of the lens. Production Phase Lens Choice • Telephoto Lens • The focal length of a “telephoto” lens results in a magnified perspective, not unlike a telescope, which makes objects appear closer than they actually are when viewed with the naked eye. The telephoto lens has a relatively shallow depth of field, meaning that only a narrow range of space before the lens can be put into focus. It also tends to compress the foreground and background of the field, making images look flat or two-dimensional. Production Phase Lens Choice • Wide Angle Lens • In direct opposition to the telephoto lens, the focal length of the wide angle results in a distanced perspective, which makes things appear further away than they actually are when viewed with the naked eye. The wide angle lens has a relatively deep field, meaning that a vast distance of space before the lens can be put into focus. It also tends to create a more three dimensional effect. An extreme wide angle lens is sometimes referred to as a “fish eye” lens. Production Phase Lens Choice • Normal Lens • The focal length of the “normal” lens is similar to the actual distance of objects in the field of view when viewed with the naked eye. • Zoom Lens • The focal length of the “zoom” lens is able to be manipulated while in use, and can range from telephoto focal lengths to wide-angle focal lengths. Production Phase Camera Movement • Camera movement guides the perspective of the spectator and causes him/her to attend to those events and features which are most important to the narrative and aesthetic of the film. There are five basic forms of camera movement: • Panning • Tilting • Tracking • Trucking • Booming • Crane • Hand-Held Production Phase Camera Movement • Panning • Panning refers to the left to right or right to left movement of the camera as it remains on a single axis. This is demonstrated graphically on the following slide. • Tilting • Tilting refers to the down to up or up to down movement of a camera while it remains on a single axis. Production Phase Camera Movement • Tracking • Tracking refers to the sideways movement of the camera as it captures a scene. • Trucking • Trucking refers to the forwards or backwards movement of the camera as it captures a scene. • (These are demonstrated graphically on the following two slides.) Production Phase Camera Movement • Booming • Booming refers to the vertical movement of the camera as it captures a scene. • Craning • Crane shots permit a wide range of sweeping motion and height in capturing a shot. This is demonstrated graphically on the next slide. Production Phase Camera Movement • Hand-Held • Just as the name indicates, hand-held camera • movement is performed without the assistance of a dolly or tripod. Hand held shots tend to have convey the subjective point of view of a character since they imitate a first-person perspective. Hand held shots are commonly used in “slasher” films to create a feeling of panic. Steadicam: A steadicam is camera mount that is attached to the operator’s body. It serves to reduce jerky movements and create the sense of a steady flow through space. Production Phase Lighting • Lighting refers to how a scene is lit, and, to a large extent, how it is exposed on film. It is among the most complex and important aspects of production and can be divided into two categories based on location and two categories based on style. • Location (Indoor versus Outdoor lighting) • Lighting Scheme (High Key versus Low Key lighting) Production Phase Lighting • Location • Indoor lighting • Indoor lighting is generally achieved through the use of specialized lamps with varying characteristics of directionality (focus), throw (distance), and intensity (brightness). There are three lights in a basic lighting setup (also see the next slide): • Key Light (provides the primary source of illumination) • Fill Light (illuminates the shadows left by the key light) • Back Light (separates the foreground from the background) Production Phase Lighting • Location • Outdoor Lighting • Outdoor lighting is generally done with large, • powerful lamps known as HMIs. In addition to lamps, other devices such as reflectors, flags, and neutral density gel may be used to increase or reduce the intensity of sunlight on various parts of the scene. Production Phase Lighting • Lighting Scheme • High Key • High key lighting is a style in which the ratio of the key light to the fill light is high and, thus, fills in most of the shadows in the scene resulting in a bright, evenly lit image. High key lighting is often used in light-hearted comedies and dramas. Production Phase Lighting • Lighting Scheme • Low Key • In opposition to high key, low key lighting refers to a low ratio of fill to key light, which results in a darker image with more “contrast” and shadows. This scheme is most often associated with film noire crime stories of the 1940s but is also frequently used in horror films and early German expressionist work. Production Phase It is the job of the director and cinematographer to coordinate these elements into a strategy for capturing the action on film. One common and efficient strategy is referred to as Shot / Mastershot or Shooting for Coverage. This technique involves shooting a full shot of the entire scene before moving in closer on a re-shoot to capture more specific cutaway shots that can later be coordinated with the master. (Continued on the next slide.) Production Phase Another strategy that is commonly employed in directing a scene is the 180° rule, which posits that the camera should take angles on only one side of the axis of action. The reason for this is that shooting on both sides of the action changes the background and may disorient the spectator. Adding an establishing shot or tracking the camera across the axis of action can prevent this. Production Phase Sound Recording • Sound recording is treated separately here because, in traditional film production, it is recorded completely independently from the image. This is known as “double system” sound recording. Generally speaking, there are at least four soundtracks in any feature length narrative film: • 1 – the sound effects track. • 2 – the music track. • 3 – the room tone track. • 4 – the dialog track. Production Phase Sound Recording • Sound Effects • For the most part, sound effects are obtained separately • by a “foley” artist who coordinates sound effects in synchronization with the onscreen action through a process known as “looping” – where a portion of the film is repeatedly played to perfect the timing of the sound effects. This is considered to be part of post-production which we will cover next. Alternatively, for low-budget productions, libraries of prerecorded sound effects can be used or sounds can be recorded during production by the sound mixer and boom operator. Production Phase Sound Recording • Music • Film music is either purchased (if it is not in the “public domain”) or scored specifically for the production. • Music that is scored is done in similar fashion to foley sound in the sense that film is playing during the recording session to enhance timing. Production Phase Sound Recording • Room Tone • Room tone is recorded silence. • Normally, once all of the dialog is recorded, the sound mixer asks for about a minute of quiet to record the sound of silence in the particular setting. The reason for recording room tone is that all recordings have a low level of “noise” in the background and, during the editing process it is sometimes necessary to fill in gaps so that there is not an abrupt change in the tone of the background noise. Production Phase Sound Recording • Dialog • In order to record dialog in “double system” film • production, it is necessary to synchronize the movement of lips with the sound of voices. Simple as this may seem, achieving it requires precision instrumentation. Most modern film sound is recorded digitally, but earlier films made use of a “crystal” synchronized analog tape recorded referred to as a “Nagra” (manufacturer’s name) which kept the speed of the tape constant so that no “drifting” occurred between the picture and the sound track. Production Phase Sound Recording • Dialog (Continued) • The function of the “clap slate” or “sticks” (see the slide after next) is to supply a marking point for when the synchronization between picture and audio begins, allowing the editor to accurately align picture with sound later during post production. • The first film credited with synchronized sound is The Jazz Singer (1927). Production Phase Sound Recording • Dialog • There are a series of steps that are taken on a film set in order to ensure the proper coordination of picture and sound track: • • • • • • • • • 1: The director says “quiet on the set” and “roll sound.” 2: The sound mixer says “sound speed” when the tape is running at the correct speed for recording synchronized sound. 3: The director calls out “roll camera.” 4: The camera operator says “speed” when the film is running at sound speed (24 frames per second). 5: The director calls out “slate.” 6: The clap slate indicating roll, scene, and take is placed before the camera and read out loud (e.g. “Roll 1, Scene 1, Take 1”). 7: The director says “mark.” 8: The slate is clapped and removed. 9: Finally, the director calls “action” to cue the actors. Postproduction Phase The postproduction phase refers to the period of time after the film is shot, but before it is released in its final form. Postproduction includes: Processing and printing of film. Transferring sound to “mag stock” – audiotape with sprocket holes. Synchronizing picture and sound track. Creating an assemblage. Creating a “rough cut.” Creating a “fine cut” and final audio mix. Conforming the original negative (A/B rolling). Adding optical effects and transitions. Creating a “married” print (joining A/B roll and sound into one final print). Postproduction Phase Processing, Printing, and Transferring. • The first few steps of postproduction are routine, requiring more technical knowledge than creative decision making: • Processing: Developing the camera negative. • Printing: Creating a “work print” for the editor to rearrange. • Transferring: Rerecording the original audio onto magnetic tape stock so that it can be manipulated and rearranged along with the picture. Postproduction Phase Synchronizing and Assembling. • Synchronizing • Because the information for synchronization on the • slate is stored at the beginning (“head”) of each take on the picture and sound track, the first task of the edit is to synchronize these before any cuts are made. This cannot be done later because, if cuts are made first, the labels will be lost separated from what they refer to. When synchronizing picture with sound, the editor simply aligns the beginning of the sound for a given take with the beginning of the picture, using the sight and sound of the clap slate for a reference point. Postproduction Phase Synchronizing and Assembling. • Assembling • Following the synchronization of the picture and dialog track, the rolls of film are divided up into individual shots and wound onto cores where they are placed in a rough sequence referred to as an “assemblage.” Postproduction Phase Rough Cut to Fine Cut and Final Audio Mix. • Between the rough cut and the fine cut is where all of the creative decisions are made. • Rough Cut: Places the film in rough sequence from • beginning to end according to the screenplay. Dialog is in place, but sound effects, and music are incomplete. Fine Cut: All of the final editing decisions and the final soundtrack mix are complete. The film is ready for laboratory work (negative cutting, effects, married printing). Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Editing is the arrangement of imagery and • sounds into a sequence that tells the story of the film. An editor may arrange based on different aesthetic styles depending upon the needs of the story. For example: • Invisible editing. • Montage editing. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • Invisible editing is sometimes referred to as “classical editing” and refers to a style that downplays the transitions between shots and keeps the focus of attention on the flow of events in the story. This form of editing works in conjunction with the Master Shot / Cutaway shooting strategy. • Transitions • Cut • Dissolve • Wipe • Fade Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • Transitions • Cut • The cut is the most basic form of a transition and refers to the abrupt ending of one shot that is simultaneous with the beginning of the next shot. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • “Hiding” the cut. • • Cutaway: The master shot orients the viewer to the onscreen environment so that the cutaway shot doesn’t appear abrupt or confusing. The viewer recognizes the cutaway as a portion of the larger environment that should be attended to because it contains story information. Reaction Shot: The reaction shot transitions from an event to a character’s response to the event. Because we, as spectators, are focused on the event itself and the character’s response to it, we are less concerned with the discontinuity of the cut. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • “Hiding” the cut (continued). • Shot/Countershot: The Shot/Countershot technique hides the cut by following the flow of events within the scene, transitioning at a particular point based on the spectator’s need for more information. For example, when editing a conversation, the transition between speakers occurs at the conclusion of a statement. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • “Hiding” the cut (continued). • Cutting on the action: In a sequence of actions, the cut can be made as the action occurs, overlapping between the outgoing and incoming shot, focusing spectator attention on the event itself rather than the way it progresses. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • Transitions • Dissolves, Wipes, & Fades. • A dissolve is the gradual replacement of one shot by the next, in which both shots appear overlapping and blended for a brief period. Dissolves can be created “in camera” by double exposing film, but they are more commonly produced by double exposure during printing. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • Transitions • Dissolves, Wipes, & Fades (Continued). • Wipes also replace one image with another, but they do so “directionally,” by scrolling over one image with another. Wipes can be either vertical or horizontal. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • Transitions • Dissolves, Wipes, & Fades (Continued). • Fades gradually obliterate the image by overexposing or underexposing until either black or white remains on the screen. Production Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • Transitions • Dissolves, Wipes, & Fades (Continued). • Unlike the “cut” which, strategically placed, can draw attention away from the transition, dissolves, wipes and fades function as conventions to convey narrative information such as the passage of time, memory, and/or emotion. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Invisible Editing. • In general, invisible editing works because it takes advantage of the fact that the cognitive resources we devote to attention are limited and our focus on the form/style of a film can easily be diverted to content. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Montage Editing. • Pioneered by Soviet filmmakers of the 1920s, montage is a style of editing in which a series of independent images are juxtaposed to create a new context for interpretation. Russian filmmaker, Sergei Eisenstein’s concept of montage resembles the Gestalt Psychology concept that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Transitions in montage editing can be guided by multiple strategies including; • • • • Rhythm (Pacing) Shape (Graphic Matching) Color Expectations (Trajectory) Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Montage Editing. • Strategies • “Rhythm” or “pacing” refers to the time intervals between shots and can be manipulated to effect spectator’s subjective sense of time. For example, the final sequence in Birth of a Nation (1915) created a sense of suspense and urgency by accelerating the pace of editing. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Montage Editing. • Strategies • Shape & Color: Abstract qualities of the image such as shape and color can link together otherwise disparate images. The “graphic match” is a technique that connects adjacent images in a montage sequence based on the characteristics of their shape. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Montage Editing. • Strategies • Expectations: Because film is a medium that portrays motion, the speed and direction of motion in a particular shot creates expectations for motion in the next shot. Mentally, we are aware of the “trajectory” of motion and carry through the expectation of that trajectory into the next shot. Thus, instead of cutting on the action and meeting those expectations completely (as in “invisible” editing), a montage transition maintains the motion, but may change the context of that motion. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • Montage Editing. • Alternatively, a common narrative usage of montage editing is to compress a portion of the larger narrative into a form that conveys elapsing time. Postproduction Phase Getting from Rough Cut to Fine Cut. • It is important to note that, although invisible editing and montage editing have been separated into two categories for the sake of analysis, they are no firm boundaries between them. Narrative films make use of both “invisible” and montage transition strategies to achieve the goals of the story. Postproduction Phase Conforming the original negative. • Once all of the editing decisions have been made, the original “camera” negative is brought to a “negative cutter” who uses cement splices and A/B rolling in order to conform the negative based on the decisions of the final cut of the workprint. Postproduction Phase Creating a married print. • Once the negative has been conformed to an • A/B roll, a married print is created and joined with the final audio mix which is inscribed at the edge of the film optically. For the purposes of distribution, an “internegative” is then created from the married print for the sake of striking positive “release” prints that are shipped to theaters. FIN