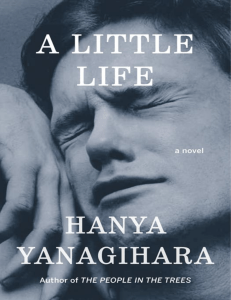

A Li%le Life by Hanya Yanagihara: Have we finally suffered enough? By Haziq Alias The book opens up with a scene where four college friends, JB, a painter, Malcolm, an architect, Willem, an actor, and Jude, a litigator, are having lunch on a bright sunny afternoon in New York City. They are laughing, bantering, and eating like all other friends, but as you move up in the story, the breezy life of attending parties, finding apartments, going on dates, and gossip diminishes. A Li%le Life by Hanya Yanagihara The writer has very intelligently made you comfortable in your reader seat only to stir discomfort in the book’s latter pages. The prose is written in an eternal present day by scrubbing away references to any historical events. The effect is that it brings the character’s emotional lives to the foreground rendering the political and cultural Zeitgeist into vague scenery. As the pages turn, the ensemble recedes; with it, Jude comes to the fore and remains at the center. Jude, who’s 16 when he arrives at an affluent New England college with only a backpack of baggy clothes, parentless and horribly scarred. His legs disfigured in an incident whose details he guards as closely as everything else about his past, he’s profoundly aware of his “extreme otherness.” The book slowly discloses luridly gothic episodes from his life before college. “You were made for this, Jude,” he’s told by the only adult he loves, a monk who betrays his trust. Consequently, Jude comes to believe that his suffering is the result of his abandonment “He had been born, and left, and found, and used as he had been intended to be used.” The book is scaled to the intensity of Jude’s inner life. The cutting becomes a leitmotif. Every fifty pages or so, we get a scene in which Jude mutilates his own flesh with a razor blade. It forces the reader to squirm with a queasy experience of the brutal world. Jude’s suffering is so extensively documented because it is the foundation of his character. His sense of self comes in waves of elaborating metaphors: he is “a scrap of bloodied, muddied cloth,” “a blank, faceless prairie under whose yellow surface earthworms and beetles wriggled,” “a scooped out husk.” His memories are “hyenas,” his fear, “a flock of flapping bats,” his selfhatred a “beast.” “A Little Life” keeps the queer suffering at the heart of the book. It uses the middle-class trappings of naturalistic fiction to deliver an unsettling meditation on abandonment, horrifying physical and sexual abuse, prostitution, abduction, and the difficulties of recovery. The collective traumas like sickness and discrimination, which have deeply shaped the modern gay identity, are approached obliquely. The writer has avoided the conventional narrative of coming out or the AIDS issues. For Jude, the relief comes in the form of career success and friendship. In addition to his law degree, Jude pursues a master’s in pure mathematics. At one point, he explains to his friends that he is drawn to math because it offers the possibility of “a wholly provable, unshakable absolute in a constructed world with very few unshakable absolutes.” Yanagihara has balanced ruthlessness by swashing us with the warmth and sunshine of friendship. Each friend of Jude’s tries to make innumerable accommodations to his daily needs. Malcolm, by designing spaces that will accommodate his disability; JB by painting kinder portraits that the eye alone would see; Willem by being the one person to whom he can tell his entire history. Willem and Jude invent their own type of relationship, which isn’t officially recognized or immortalized through words, but is truer and less constraining than legalized ones. “Why wasn’t friendship as good as a relationship? Why wasn’t it even better? It was two people who remained together, day after day, bound not by sex or physical attraction or money or children or property, but only by the shared agreement to keep going, the mutual dedication to a union that could never be codified.” The prose beautifully depicts how friendship can be the primary relationship for some people. I loved how the book portrays the lives that are rarely depicted in popular art – a life without marriage and children. How, in periods of crisis, Jude’s friends monitor him like hawks, taking turns to feed him and keep a close eye on his self-harm. For Jude, his friends are his only refuge and saviour in this toxic world. Yet the ending makes you realize that in the end, you are really left on your own. Even though so many friends come in and out of Jude’s life, nobody is really able to save him. And that part is a very accurate reflection of, lot of adult lives.