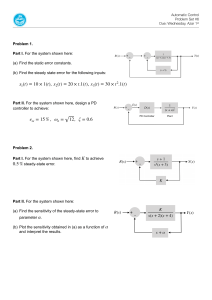

Design Examples and Design Problems (DP)

CHAPTER I

PAGE

Example Hybrid Fuel Vehicles

21

22

Example Wind Power

Example Embedded Computers

23

25

Example Rotating Disk Speed Control

27

Example Insulin Delivery Control System

Example Disk Drive Read System

28

38

CDP1.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

Automobile Noise Control

38

DP1.1

38

DP 1.2

Automobile Cruise Control

Dairy Farm Automation

38

DP 1.3

Welder Control

38

DPI.4

38

Automobile Traction Control

DP1.5

39

Hubble Telescope Vibration

DP1.6

Nanorobotics in Medicine

39

DPI.7

CHAPTER 2

Example Fluid Flow Modeling

Example Electric Traction Motor Control

Example Mechanical Accelerometer

Example Laboratory Robot

Example Low-Pass Filter

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP2.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP2.1

Selection of Transfer Functions

DP2.2

Television Beam Circuit

DP2.3

Transfer Function Determination

DP2.4

Op Amp Differentiating Circuit

CHAPTER 3

Example Modeling the Orientation of a

Space Station

Example Printer Bell Drive

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP3.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP3.1

Shock Absorber for Motorcycle

DP3.2

Diagonal Matrix Differential

Equation

DP3.3

Aircraft Arresting Gear

DP3.4

Bungi Jumping System

DP3.5

State Variable Feedback

CHAPTER 4

Example English Channel Boring

Machines

Example Mars Rover Vehicle

Example Blood Pressure Control

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP4.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

83

93

95

98

99

117

139

139

139

139

139

176

183

192

21)8

208

209

209

209

209

232

235

237

251

270

DP4.1

DP4.2

DP4.3

DP4.4

DP4.5

DP4.6

Speed Control System

Airplane Roll Angle Control

Velocity Control System

Laser Eye Surgery

Pulse Generating Op Amp

Hvdrobot

270

271

271

271

272

272

CHAPTER 5

Example Hubble Telescope Pointing

Example Attitude Control of an Airplane

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP5.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP5.1

Jet Fighter Roll Angle Control

DP5.2

Welding Arm Position Control

DP5.3

Automobile Active Suspension

DP5.4

Satellite Orientation Control

DP5.5

De-burring Robot for Machined

Parts

DP5.6

DC Motor Position Control

350

351

CHAPTER 6

Example Tracked Vehicle Turning

Example Robot-Controlled Motorcycle

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP6.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP6.1

Automobile Ignition Control

DP6.2

Mars Guided Vehicle Control

DP6.3

Parameter Selection

DP6.4

Space Shuttle Rocket

DP6.5

Traffic Control System

DP6.6

State Variable Feedback

DP6/7

Inner and Outer Loop Control

DP6.8

PD Controller Design

373

375

390

402

402

403

403

403

403

403

404

404

CHAPTER 7

Example Laser Manipulator Control

Example Robot Control System

Example Automobile Velocity Control

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP7.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP7.1

Pitch Rate Aircraft Control

DP7.2

Helicopter Velocity Control

DP7.3

Mars Rover

DP7.4

Remotely Controlled Welder

DP7.5 ' High-Performancc Jet Aircraft

DP7.6

Control of Walking Motion

DP7.7

OP Amp Control System

DP7.8

Robot Arm Elbow Joint

Actuator

DP7.9

Four-Wheel-Steered Automobile

316

319

333

349

349

349

349

350

447

448

452

463

485

485

485

486

486

486

486

487

487

487

DP7.10

DP7.11

DP7.12

DP7.13

Pilot Crane Control

Planetary Rover Vehicle

Roll Angle Aircraft Autopilot

PD Control of a Marginally

Stable Process

CHAPTER 8

Example Engraving Machine Control

Example Control of a Six-Legged Robot

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP8.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP8.1

Automobile Steering System

DP8.2

Autonomous Planetary

Explorer-Ambler

DP8.3

Vial Position Control Under a

Dispenser

DP8.4

Automatic Anesthesia Control

DP8.5

Black Box Control

DP8.6

State Variable System Design

CHAPTER 9

Example Remotely Controlled

Reconnaissance Vehicle

Example Hot Ingot Robot Control

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP9.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP9.1

Mobile Robot for Toxic Waste

Cleanup

DP9.2

Control of a Flexible Arm

DP9.3

Blood Pressure Regulator

DP9.4

Robot Tennis Player

DP9.5

Electrohydraulic Actuator

DP9.6

Steel Strip-Rolling Mill

DP9.7

Lunar Vehicle Control

DP9.8

High-Speed Steel-Rolling Mill

DP9.9

Two-Tank Temperature Control

DP9.10 State Variable Feedback Control

CHAPTER 10

Example Rotor Winder Control System

Example The X-Y Plotter

Example Milling Machine Control System

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP10.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP10.1 Two Cooperating Robots

DPI 0.2 Heading Control of a Bi-Wing

Aircraft

DP10.3 Mast Flight System

DP10.4 Robot Control Using Vision

DP10.5 High-Speed Train Tilt Control

DP10.6 Large Antenna Control

DPI 0.7 Tape Transport Speed Control

DP10,8 Automobile Engine Control

DP10.9 Aircraft Roll Angle Control

488

488

489

DP10.10 Windmill Radiometer

DP10.11 Control with Time Delay

DP10.12 Loop Shaping

751

752

752

489

CHAPTER 11

Example Automatic Test System

Example Diesel Electric Locomotive

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP11.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DPI LI Levitation of a Steel Ball

DPI 1.2 Automobile Carburetor

DPI 1.3 Sta te Variable Compensation

DP11.4 Helicopter Control

DP1L5 Manufacturing of Paper

DPI 1.6 Coupled-Drive Control

DPI 1.7 Tracking a Reference Input

795

798

810

821

821

821

821

822

822

823

823

523

526

540

561

561

561

561

561

563

563

607

610

629

659

659

659

659

659

659

659

662

662

663

707

711

714

726

747

747

747

747

749

749

749

750

750

751

CHAPTER 12

Example Aircraft Autopilot

Example Space Telescope Control

Example Robust Bobbin Drive

Example Ultra-Precision Diamond

Turning Machine

Example Digital Audio Tape Controller

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP12.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP12.1 Turntable Position Control

DP12.2 Robust Parameter Design

DP12.3 Dexterous Hand Master

DP12.4 Microscope Control

DP12.5 Microscope Control

DP12.6 Artificial Control of Leg

Articulation

DP 12.7 Elevator Position Control

DP12.8 Electric Ventricular Assist

Device

DP12.9 Space Robot Control

DP12.10 Solar Panel Pointing Control

DP12.11 Magnetically Levitated Train

DP12,12 Mars Guided Vehicle Control

DP12.13 Benchmark Mass-Spring

CHAPTER 13

Example Worktable Motion Control

Example Fly-by-wire Aircraft Control

Example Disk Drive Read System

CDP13.1 Traction Drive Motor Control

DP13.1 Temperature Control System

DP13.2 Disk Drive Read-Write HeadPositioning System

DP13.3 Vehicle Traction Control

DP13.4 Machine-Tool System

DP13.5 Polymer Extruder Control

DP13.6 Sampled-Data System

853

853

856

858

861

876

891

891

891

891

892

893

893

894

894

895

896

896

896

896

926

928

940

947

947

947

947

948

948

948

Modern

Control Systems

ELEVENTH EDITION

Richard C. Dorf

University of California, Davis

Robert H. Bishop

The University of Texas at Austin

Pearson Education International

If you purchased this book within the United States or Canada you should be aware that it has been wrongfully

imported without the approval of the Publisher or the Author.

Vice President and Editorial Director, ECS: Marcia L Horton

Acquistions Editor: Michael McDonald

Senior Managing Editor: Scott Disanno

Senior Production Editor: Irwin Zucker

Art Editor: Greg Dulles

Manufacturing Manager: Alexis Heydt-Long

Manufacturing Buyer: Lisa McDowell

Senior Marketing Manager: Tim Galligan

© 2008 Pearson Education, Inc.

Pearson Prentice Hall

Pearson Education, Inc.

Upper Saddle River, NJ 07458

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

Pearson Prentice Hall® is a trademark of Pearson Education, Ina

MATLAB is a registered trademark of The Math Works, Inc., 24 Prime Park Way, Natick, MA 01760-1520

The author and publisher of this book have used their best efforts in preparing this book. These efforts include the

development, research, and testing of the theories and programs to determine their effectiveness. The author and

publisher make no warranty of any kind, expressed or implied, with regard to these programs or the documentation contained in this book. The author and publisher shall not be liable in any event for incidental or consequential damages in connection with, or arising out of, the furnishing, performance, or use of these programs.

Printed in Singapore

10

ISBN

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

0-13-20L710-2

^-0-13-201,710-2

Pearson Education Ltd., London

Pearson Education Australia Pty. Ltd., Sydney

Pearson Education Singapore, Pte. Ltd.

Pearson Education North Asia Ltd., Hong Kong

Pearson Education Canada, Inc., Toronto

Pearson Educacion de Mexico, S.A. de C.V.

Pearson Education—Japan, Tokyo

Pearson Education Malaysia, Pte. Ltd.

Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey

Of the greater teachers—

when they are gone,

their students will say:

we did it ourselves.

Dedicated to

Lynda Ferrera Bishop

and

Joy MacDonald Dorf

In grateful appreciation

Contents

Preface xiii

About the Authors

CHAPTER

1

Introduction to Control Systems

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

1-7

1.8

1.9

1.10

CHAPTER

2

xxv

1

Introduction 2

Brief History of Automatic Control 4

Examples of Control Systems 8

Engineering Design 16

Control System Design 17

Mechatronic Systems 20

The Future Evolution of Control Systems 24

Design Examples 25

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 28

Summary 30

Exercises 30

Problems 31

Advanced Problems 36

Design Problems 38

Terms and Concepts 39

Mathematical Models of Systems 41

2.1

2.2

2.3

2.4

2.5

2.6

2.7

2.8

2.9

2.10

2.11

Introduction 42

Differential Equations of Physical Systems 42

Linear Approximations of Physical Systems 47

The Laplace Transform 50

The Transfer Function of Linear Systems 57

Block Diagram Models 71

Signal-Flow Graph Models 76

Design Examples 82

The Simulation of Systems Using Control Design Software 102

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 117

Summary 119

Exercises 120

Problems 126

Advanced Problems 137

Design Problems 139

Computer Problems 140

Terms and Concepts 142

v

vi

CHAPTER

Contents

3

State Variable Models

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

3.5

3.6

3.7

3.8

3.9

3.10

3.11

CHAPTER

4

5

Introduction 145

The State Variables of a Dynamic System 145

The State Differential Equation 149

Signal-Flow Graph and Block Diagram Models 154

Alternative Signal-Flow Graph and Block Diagram Models 165

The Transfer Function from the State Equation 170

The Time Response and the State Transition Matrix 172

Design Examples 176

Analysis of State Variable Models Using Control Design Software

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 192

Summary 196

Exercises 197

Problems 199

Advanced Problems 207

Design Problems 208

Computer Problems 210

Terms and Concepts 211

189

Feedback Control System Characteristics 212

41

4.2

4.3

4.4

4.5

4.6

4.7

4.8

4.9

4.10

4.11

CHAPTER

144

Introduction 213

Error Signal Analysis 215

Sensitivity of Control Systems to Parameter Variations 217

Disturbance Signals in a Feedback Control System 220

Control of the Transient Response 225

Steady-State Error 228

The Cost of Feedback 231

Design Examples 232

Control System Characteristics Using Control Design Software 246

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 251

Summary 255

Exercises 257

Problems 261

Advanced Problems 267

Design Problems 270

Computer Problems 273

Terms and Concepts 276

The Performance of Feedback Control Systems

5.1

5.2

5.3

Introduction 278

Test Input Signals 278

Performance of Second-Order Systems 281

277

Contents

5.4

5.5

5.6

5*7

5.8

5.9

5.10

5.11

5.12

CHAPTER

6

Effects of a Third Pole and a Zero on the Second-Order System

Response 287

The s-Plane Root Location and the Transient Response 293

The Steady-State Error of Feedback Control Systems 295

Performance Indices 303

The Simplification of Linear Systems 312

Design Examples 315

System Performance Using Control Design Software 329

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 333

Summary 337

Exercises 337

Problems 341

Advanced Problems 346

Design Problems 348

Computer Problems 350

Terms and Concepts 353

The Stability of Linear Feedback Systems

6.1

6.2

6.3

6.4

6.5

6.6

6.7

6.8

CHAPTER

VII

The Concept of Stability 356

The Routh-Hurwitz Stability Criterion 360

The Relative Stability of Feedback Control Systems 368

The Stability of State Variable Systems 370

Design Examples 373

System Stability Using Control Design Software 382

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 390

Summary 393

Exercises 394

Problems 396

Advanced Problems 400

Design Problems 402

Computer Problems 404

Terms and Concepts 406

The Root Locus Method

7.1

7.2

7.3

7.4

7.5

7.6

7.7

7.8

7.9

355

407

Introduction 408

The Root Locus Concept 408

The Root Locus Procedure 413

Parameter Design by the Root Locus Method 431

Sensitivity and the Root Locus 437

Three-Term (PID) Controllers 444

Design Examples 447

The Root Locus Using Control Design Software 458

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 463

viii

Contents

7*10

CHAPTER

8

Frequency Response Methods

8.1

8.2

83

8.4

8.5

8.6

8.7

8.8

8.9

CHAPTER

9

Summary 465

Exercises 469

Problems 472

Advanced Problems 482

Design Problems 485

Computer Problems 490

Terms and Concepts 492

493

Introduction 494

Frequency Response Plots 496

Frequency Response Measurements 517

Performance Specifications in the Frequency Domain 519

Log Magnitude and Phase Diagrams 522

Design Examples 523

Frequency Response Methods Using Control Design Software

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 540

Summary 541

Exercises 546

Problems 549

Advanced Problems 558

Design Problems 560

Computer Problems 564

Terms and Concepts 566

Stability in the Frequency Domain

9.1

9.2

9.3

9.4

9.5

9.6

9.7

9.8

9.9

9.10

9.11

9.12

534

567

Introduction 568

Mapping Contours in the s-Plane 569

The Nyquist Criterion 575

Relative Stability and the Nyquist Criterion 586

Time-Domain Performance Criteria in the Frequency Domain 594

System Bandwidth 601

The Stability of Control Systems with Time Delays 601

Design Examples 606

PID Controllers in the Frequency Domain 620

Stability in the Frequency Domain Using Control Design Software 621

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 629

Summary 632

Exercises 640

Problems 646

Advanced Problems 656

Design Problems 659

Computer Problems 664

Terms and Concepts 665

Contents

CHAPTER

1 0 The Design of Feedback Control Systems

10.1

10.2

103

10.4

10*5

10.6

10.7

10.8

10.9

10.10

10.11

10.12

10.13

10.14

10.15

CHAPTER

IX

667

Introduction 668

Approaches to System Design 669

Cascade Compensation Networks 671

Phase-Lead Design Using the Bode Diagram 675

Phase-Lead Design Using the Root Locus 681

System Design Using Integration Networks 688

Phase-Lag Design Using the Root Locus 691

Phase-Lag Design Using the Bode Diagram 696

Design on the Bode Diagram Using Analytical Methods 700

Systems with a Prefilter 702

Design for Deadbeat Response 705

Design Examples 707

System Design Using Control Design Software 720

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 726

Summary 728

Exercises 730

Problems 734

Advanced Problems 744

Design Problems 747

Computer Problems 752

Terms and Concepts 754

11 The Design of State Variable Feedback

Systems 756

11.1

11.2

11.3

1L4

11.5

11.6

11.7

11.8

11.9

11.10

11.11

11.12

Introduction 757

Controllability and Observability 757

Full-State Feedback Control Design 763

Observer Design 769

Integrated Full-State Feedback and Observer 773

Reference Inputs 779

Optimal Control Systems 781

Internal Model Design 791

Design Examples 795

State Variable Design Using Control Design Software 804

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 810

Summary 812

Exercises 812

Problems 814

Advanced Problems 818

Design Problems 821

Computer Problems 824

Terms and Concepts 826

X

CHAPTER

Contents

1 2 Robust Control Systems

12.1

12.2

12.3

12.4

12.5

12.6

12.7

12.8

12.9

12.10

12*11

12.12

CHAPTER

828

Introduction 829

Robust Control Systems and System Sensitivity 830

Analysis of Robustness 834

Systems with Uncertain Parameters 836

The Design of Robust Control Systems 838

The Design of Robust PID-Controlled Systems 844

The Robust Internal Model Control System 850

Design Examples 853

The Pseudo-Quantitative Feedback System 870

Robust Control Systems Using Control Design Software 871

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 876

Summary 878

Exercises 879

Problems 881

Advanced Problems 887

Design Problems 891

Computer Problems 897

Terms and Concepts 899

1 3 Digital Control Systems 901

13.1

13.2

13.3

13.4

13.5

13.6

13.7

13.8

13.9

13.10

13.11

13.12

13.13

Introduction 902

Digital Computer Control System Applications 902

Sampled-Data Systems 904

The z-Transform 907

Closed-Loop Feedback Sampled-Data Systems 912

Performance of a Sampled-Data, Second-Order System 916

Closed-Loop Systems with Digital Computer Compensation 918

The Root Locus of Digital Control Systems 921

Implementation of Digital Controllers 925

Design Examples 926

Digital Control Systems Using Control Design Software 935

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System 940

Summary 942

Exercises 942

Problems 945

Advanced Problems 946

Design Problems 947

Computer Problems 949

Terms and Concepts 950

Contents

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX

B

XI

MATLAB Basics

953

MathScript Basics

971

<j£W WEB RESOURCES

APPENDIX C

Symbols, Units, and Conversion Factors

APPENDIX

D

Laplace Transform Pairs

APPENDIX

E

An Introduction to Matrix Algebra

APPENDIX

F

Decibel Conversion

APPENDIX

G

Complex Numbers

APPENDIX

H

z-Transform Pairs Preface

APPENDIX

I

Discrete-Time Evaluation of the Time Response

References 993

Index

1007

Preface

MODERN CONTROL SYSTEMS—THE BOOK

The Mars Exploration Rover (MER-A), also known as Spirit, was launched on a

Delta II rocket, in June 2003 to Mars, the Red Planet. Spirit entered the Martian

atmosphere seven months later in January, 2004. When the spacecraft entered the

Martian atmosphere it was traveling 19,300 kilometers per hour. For about four

minutes in the upper atmosphere, the spacecraft aeroshell decelerated the vehicle to

a velocity of 1,600 kilometers per hour. Then a parachute was deployed to slow the

spacecraft to about 300 kilometers per hour. At an altitude of about 100 meters.

retrorockets slowed the descent and airbags were inflated to cushion the shock of

landing. The Spirit struck the Martian ground at around 50 km/hr and bounced and

rolled until it stopped near the target point in the Gusev Crater. The target landing

site was chosen because it looks like a crater lakebed. The Spirit mobile rover has

reached interesting places in the Gusev Crater to perform in-situ tests to help scientists answer many of the lingering questions about the history of our neighbor planet.

In fact, Spirit discovered evidence of an ancient volcanic explosion near the landing

site in Gusev Crater. The successful entry, descent, and landing of Spirit is an astonishing illustration of the power of control systems. Given the large distances to Mars,

it is not possible for a spacecraft to fly through the atmosphere while under ground

control—the entry, descent, and landing must be controlled autonomously on-board

the spacecraft. Designing systems capable of performing planetary entry is one of

the great challenges facing control system engineers.

The precursor NASA Mars mission, known as the Mars Pathfinder, also journeyed to the Red Planet and landed on July 4,1997. The Pathfinder mission, one of

the first of the NASA Discovery-class missions, was the first mission to land on Mars

since the successful Viking spacecraft in the 1970s. Pathfinder deployed the firstever autonomous rover vehicle, known as the Sojourner, to explore the landing site

area. The mobile Sojourner had a mass of 10.5 kilograms and traveled a total of 100

meters (never straying more than 12 meters or so from the lander) in its 30-day mission. By comparison, the Spirit rover has a mass of 180 kilograms and is designed to

roam about 40 meters per day. Spirit has spent four years exploring Mars and has

driven over 7 kilometers. The fast pace of development of more capable planetary

rovers is evident. Plans for the Mars Science Laboratory planetary rover (scheduled

for launch in 2009) call for a 1000-kilogram rover with a mission duration of 500

days and the capability to traverse 30 kilometers over the mission lifetime.

Control engineers play a critical role in the success of the planetary exploration

program.The role of autonomous vehicle spacecraft control systems will continue to

increase as flight computer hardware and operating systems improve. Pathfinder

used a commercially produced, multitasking computer operating system hosted in a

32-bit radiation-hardened workstation with 1-gigabyte storage, programmable in C.

xiii

Preface

This was quite an advancement over the Apollo computers, which had a fixed (readonly) memory of 36,864 words (one word was 16 bits) together with an erasable

memory of 2,048 words. The Apollo "programming language" was a pseudocode notation encoded and stored as a list of data words "interpreted" and translated into a

sequence of subroutine links^The M E R computer in the Spirit rover utilizes a 32bit Rad 6000 microprocessor operating at a speed of 20 million instructions per second. This is a radiation-hardened version of the PowerPC chip used in many

Macintosh computers. The on-board memory includes 128 megabytes of random access memory, 256 megabytes of flash memory, and smaller amounts of other nonvolatile memory t o protect against power-off cycles so that data will not be

unintentionally erased. The total memory and power of the MER computers is approximately the equivalent memory of a typical powerful laptop. As with all space

mission computers, the Spirit computer contains special memory to tolerate the

extreme radiation environment from space. Interesting real-world problems, such as

planetary mobile rovers like Spirit and Sojourner, are used as illustrative examples

throughout the b o o k . For example, a mobile rover design problem is discussed in

the Design Example in Section 4.8.

Control engineering is an exciting and a challenging field. By its very nature,

control engineering is a multidisciphnary subject, and it has taken its place as a

core course in the engineering curriculum. It is reasonable to expect different

approaches to mastering and practicing the art of control engineering. Since the

subject has a strong mathematical foundation, we might approach it from a strictly

theoretical point of view, emphasizing theorems and proofs. On the other hand,

since the ultimate objective is to implement controllers in real systems, we might

take an ad hoc approach relying only on intuition and hands-on experience when

designing feedback control systems. Our approach is to present a control engineering methodology that, while based on mathematical fundamentals, stresses

physical system modeling and practical control system designs with realistic system

specifications.

We believe that the most important and productive approach to learning is for

each of us to rediscover and re-create anew the answers and methods of the past.

Thus, the ideal is to present the student with a series of problems and questions and

point to some of the answers that have been obtained over the past decades.The traditional method—to confront the student not with the problem but with the finished

solution—is to deprive the student of all excitement, to shut off the creative

impulse, to reduce t h e adventure of humankind to a dusty heap of theorems. The

issue, then, is to present some of the unanswered and important problems that we

continue to confront, for it may be asserted that what we have truly learned and

understood, we discovered ourselves.

The purpose of this book is to present the structure of feedback control theory

and to provide a sequence of exciting discoveries as we proceed through the text

and problems. If this book is able to assist the student in discovering feedback control system theory a n d practice, it will have succeeded.

!

For further reading on the Apollo guidance, navigation, and control system, see R. H. Battin, An Introduction to the Mathematics and Methods of Astrodynamics, AIAA Education Series, J. S. Pzemieniecki/Series

Editor-in-Chief, 1987.

Preface

xv

THE AUDIENCE

This text is designed for an introductory undergraduate course in control systems for

engineering students. There is very little demarcation between aerospace, chemical,

electrical, industrial, and mechanical engineering in control system practice; therefore, this text is written without any conscious bias toward one discipline. Thus, it is

hoped that this book will be equally useful for all engineering disciplines and, perhaps, will assist in illustrating the utility of control engineering. The numerous problems and examples represent all fields, and the examples of the sociological,

biological, ecological, and economic control systems are intended to provide the

reader with an awareness of the general applicability of control theory to many

facets of life. We believe that exposing students of one discipline to examples and

problems from other disciplines will provide them with the ability to see beyond

their own field of study. Many students pursue careers in engineering fields other

than their own. For example, many electrical and mechanical engineers find themselves in the aerospace industry working alongside aerospace engineers. We hope this

introduction to control engineering will give students a broader understanding of

control system design and analysis.

In its first ten editions, Modern Control. Systems has been used in senior-level

courses for engineering students at more than 400 colleges and universities. It also

has been used in courses for engineering graduate students with no previous background in control engineering.

THE ELEVENTH EDITION

A companion website is available to students and faculty using the eleventh edition.

The website contains practice exercises, all the m-files in the book, Laplace and

z-transform tables, written materials on matrix algebra, complex numbers, and symbols, units, and conversion factors. An icon will appear in the book margin whenever

there is additional related material on the website. Also, since the website provides

a mechanism for continuously updating and adding control-related materials of

interest to students and professors, it is advisable to visit the website regularly during the semester or quarter when taking the course. The MCS website address is

http://www.prenhall.com/dorf.

With the eleventh edition, we continue to evolve the design emphasis that historically has characterized Modem Control Systems. Using the real-world engineering

problems associated with designing a controller for a disk drive read system, we present the Sequential Design Example (identified by an arrow icon in the text), which is

considered sequentially in each chapter using the methods and concepts in that chapter. Disk drives are used in computers of all sizes and they represent an important application of control engineering. Various aspects of the design of controllers for the disk

drive read system are considered in each chapter. For example, in Chapter 1 we identify

the control goals, identify the variables to be controlled, write the control specifications,

and establish the preliminary system configuration for the disk drive.Then, in Chapter 2,

we obtain models of the process, sensors, and actuators. In the remaining chapters, we

continue the design process, stressing the main points of the chapters.

xvi

Preface

Rotation

of arm

Spindle

Track a

Track b

Head slider

<7J

In the same spirit as the Sequential Design Example, we present a design problem that we call the Continuous Design Problem (identified by a triple arrow icon in

the text) to give students the opportunity to build upon a design problem from

chapter to chapter. High-precision machinery places stringent demands on table

slide systems. In the Continuous Design Problem, students apply the techniques and

tools presented in each chapter to the development of a design solution that meets

the specified requirements.

Table

The computer-aided design and analysis component of the book continues to

evolve and improve. The end-of-chapter computer problem set is identified by the

graphical icon in the text. Also, many of the solutions to various components of

the Sequential Design Example utilize m-files with corresponding scripts included

in the figures.

PEDAGOGY

The book is organized around the concepts of control system theory as they have

been developed in the frequency and time domains. An attempt has been made to

make the selection of topics, as well as the systems discussed in the examples and

Preface

XVII

problems, modern in the best sense. Therefore, this book includes discussions on

robust control systems and system sensitivity, state variable models, controllability

and observability, computer control systems, internal model control, robust PID controllers, and computer-aided design and analysis, to name a few. However, the classical topics of control theory that have proved to be so very useful in practice have

been retained and expanded.

Building Basic Principles: From Classical to Modern. Our goal is to present a clear

exposition of the basic principles of frequency- and time-domain design techniques.

The classical methods of control engineering are thoroughly covered: Laplace transforms and transfer functions; root locus design; Routh-Hurwitz stability analysis;

frequency response methods, including Bode, Nyquist, and Nichols; steady-state

error for standard test signals; second-order system approximations; and phase and

gain margin and bandwidth. In addition, coverage of the state variable method is

significant. Fundamental notions of controllability and observability for state variable models are discussed. Full state feedback design with Ackermann's formula for

pole placement is presented, along with a discussion on the limitations of state variable feedback. Observers are introduced as a means to provide state estimates when

the complete state is not measured.

Upon this strong foundation of basic principles, the book provides many opportunities to explore topics beyond the traditional. Advances in robust control theory

are introduced in Chapter 12. The implementation of digital computer control systems is discussed in Chapter 13. Each chapter (but the first) introduces the student

to the notion of computer-aided design and analysis. The book concludes with an

extensive references section, divided by chapter, to guide the student to further

sources of information on control engineering.

Progressive Development of Problem-Solving Skills. Reading the chapters, attending

lectures and taking notes, and working through the illustrated examples are all part of

the learning process. But the real test comes at the end of the chapter with the problems. The book takes the issue of problem solving seriously. In each chapter, there are

five problem types:

U

_1

G

G

•

Exercises

Problems

Advanced Problems

Design Problems

Computer Problems

For example, the problem set for The Root Locus Method, Chapter 7 (see page

407) includes 27 exercises, 39 problems, 13 advanced problems, 13 design problems,

and 9 computer-based problems. The exercises permit the students to readily utilize

the concepts and methods introduced in each chapter by solving relatively straightforward exercises before attempting the more complex problems. Answers to onethird of the exercises are provided. The problems require an extension of the

concepts of the chapter to new situations. The advanced problems represent problems of increasing complexity. The design problems emphasize the design task; the

'

XViii

Preface

computer-based problems give the student practice with problem solving using

computers. In total, the book contains more than 800 problems. Also, the MCS website contains practice exercises that are instantly graded, so they provide quick feedback for students. The abundance of problems of increasing complexity gives

students confidence in their problem-solving ability as they work their way from the

exercises to the design and computer-based problems. A complete instructor manual,

available for all adopters of the text for course use, contains complete solutions to

all end-of-chapter problems.

A set of m-files, the Modern Control Systems Toolbox, has been developed by

the authors to supplement the text. The m-files contain the scripts from each computer-based example in the text. You may retrieve the m-files from Prentice Hall at

http://www.prenhall.com/dorf.

Design Emphasis without Compromising Basic Principles. The all-important topic

of design of real-world, complex control systems is a major theme throughout the

text. Emphasis on design for real-world applications addresses interest in design by

ABET and industry.

The design process consists of seven main building blocks which we arrange

into three groups:

1. Establishment of goals and variables to be controlled, and definition of

specifications (metrics) against which to measure performance

2. System definition and modeling

3. Control system design and integrated system simulation and analysis

In each chapter of this book, we highlight the connection between the design

process and the main topics of that chapter. The objective is to demonstrate different aspects of the design process through illustrative examples. Various aspects of

the control system design process are illustrated in detail in the following examples:

J

insulin delivery control system (Section 1.8, page 27)

•

fluid flow modeling (Section 2.8, page 83)

•

space station orientation modeling (Section 3.8, page 176)

J

blood pressure control during anesthesia (Section 4.8, page 237)

D

attitude control o f an airplane (Section 5.9,page 319)

3

robot-controlled motorcycle (Section 6.5, page 375)

3

automobile velocity control (Section 7.7, page 452)

_1

control of one l e g of a six-legged robot (Section 8.6, page 526)

•

hot ingot robot control (Section 9.8,page 610)

U

milling machine control system (Section 10.12, page 714)

_1

diesel electric locomotive control (Section 11.9, page 798)

U

digital audio t a p e controller (Section 12.8, page 861)

i_l

fly-by-wire aircraft control surface (Section 13.10, page 928)

Preface

XIX

In this column remarks

relate the design topics on

the left to specific sections,

figures, equations, and tables

in the example.

Topics emphasized in this example

Establish the control goals

Shading indicates the -"""^

topics that are emphasized

in each chapter. Some chapters

will have many shaded blocks,

and other chapters will emphasize

just one or two topics.

Identify the variables to be controlled

(1) Establishment of goals,

variables to be controlled,

and specifications.

Write the specifications

1

h

i

W

Establish (he system configuration

(2) System definition

and modeling.

i

Obtain a model of the process, the

actuator, and the sensor

•

•

Describe a controller and select key

parameters to be adjusted

(3) Control system design,

simulation, and analysis.

*r

Optimize the parameters and

analyze the performance

If the performance does not meet the

specifications, then iterate the configuration.

1

If the performance meets the specifications,

then finalize the design.

Each chapter includes a section to assist students in utilizing computer-aided

design and analysis concepts and rework many of the design examples. In Chapter 5,

the Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System is analyzed using computerbased methods. An m-fjle script that can be used to analyze the design is presented in

Figure 5.47, p. 335. In general, each script is annotated with comment boxes that

highlight important aspects of the script. The accompanying output of the script

(generally a graph) also contains comment boxes pointing out significant elements.

The scripts can also be utilized with modifications as the foundation for solving

other related problems.

XX

Preface

Select K„.

Ka=30; •*

H0:0.01:1];

nc=[Ka*5];dc=[1 ]; sysc=tf(nc,dc);

ng=[1];dg=[1 20 0]; sysg=tf(r,g,dg);

sysl =series(sysc,sysg);

sys=feedback(sys1, [1 ]);

y=step(sys,t);

plot(t,y), grid

xlabel(Time (s)')

ylabel('y(t)')

Compute the

closed-loop

transfer function.

(a)

1.2

^^CT~ & = 60.

1

pN^

1

1

0.8

\/

JL

]

i

1

Ka = 30.

0.6

/i

/

.

1

/

0.4

1

0.2

1

1

n

j/

0

i

L

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

Time (s)

0.7

0.3

0.9

(b)

Learning Enhancement. Each chapter begins with a chapter preview describing

the topics the student can expect to encounter. The chapters conclude with an

end-of-chapter summary, as well as terms and concepts. These sections reinforce

the important concepts introduced in the chapter and serve as a reference for

later use.

A second color is used to add emphasis when needed and to make the graphs

and figures easier to interpret. Design Problem 4.4, page 217, asks the student to determine the value of K of the controller so that the response, denoted by Y(.v), to a

step change in the position, denoted by R(s), is satisfactory and the effect of the disturbance, denoted by Td(s), is minimized.The associated Figure DP4.4, p. 272, assists

the student with (a) visualizing the problem and (b) taking the next step to develop

the transfer function model and to complete the design.

Preface

XXI

Controller <

Ophthalmologist

Argon laser »

position

(b)

THE ORGANIZATION

Chapter 1 Introduction to Control Systems. Chapter 1 provides an introduction to

the basic history of control theory and practice. The purpose of this chapter is to

describe the general approach to designing and building a control system.

Chapter 2 Mathematical Models of Systems. Mathematical models of physical systems in input-output or transfer function form are developed in Chapter 2. A wide

range of systems (including mechanical, electrical, and fluid) are considered.

Chapter 3 State Variable Models. Mathematical models of systems in state variable form are developed in Chapter 3. Using matrix methods, the transient response

of control systems and the performance of these systems are examined.

Chapter 4 Feedback Control System Characteristics. The characteristics of feedback control systems are described in Chapter 4. The advantages of feedback are

discussed, and the concept of the system error signal is introduced.

XXii

Preface

Chapter 5 The Performance of Feedback Control Systems. In Chapter 5, the performance of control systems is examined. The performance of a control system is

correlated with the s-plane location of the poles and zeros of the transfer function of

the system.

Chapter 6 The Stability of Linear Feedback Systems. The stability of feedback systems is investigated in Chapter 6. The relationship of system stability to the characteristic equation of the system transfer function is studied. The Routh-Hurwitz

stability criterion is introduced.

Chapter 7 The Root Locus Method. Chapter 7 deals with the motion of the

roots of the characteristic equation in the s-plane as one or two parameters are varied. The locus of roots in the s-plane is determined by a graphical method. We also

introduce the popular PTD controller.

Chapter 8 Frequency Response Methods. In Chapter 8, a steady-state sinusoid

input signal is utilized to examine the steady-state response of the system as the frequency of the sinusoid is varied. The development of the frequency response plot,

called the Bode plot, is considered.

Chapter 9 Stability in the Frequency Domain. System stability utilizing frequency

response methods is investigated in Chapter 9. Relative stability and the Nyquist

criterion are discussed.

Chapter 10 The Design of Feedback Control Systems. Several approaches to designing and compensating a control system are described and developed in Chapter

10. Various candidates for service as compensators are presented and it is shown

how they help to achieve improved performance.

Chapter 11 The Design of State Variable Feedback Systems. The main topic of

Chapter 11 is the design of control systems using state variable models. Full-state

feedback design and observer design methods based on pole placement are discussed. Tests for controllability and observability are presented, and the concept of

an internal model design is discussed.

Chapter 12 Robust Control Systems. Chapter 12 deals with the design of highly

accurate control systems in the presence of significant uncertainty. Five methods for

robust design are discussed, including root locus, frequency response, ITAE methods for robust PID controllers, internal models, and pseudo-quantitative feedback.

Chapter 13 Digital Control Systems. Methods for describing and analyzing the

performance of computer control systems are described in Chapter 13. The stability

and performance of sampled-data systems are discussed.

Appendixes. The appendixes are as follows:

A MATLAB Basics

B MathScript Basics

Preface

xxiii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to express our sincere appreciation to the following individuals who have

assisted us with the development of this eleventh edition, as well as all previous editions: Mahmoud A. Abdallah, Central Sate University (OH); John N. Chiasson, University of Pittsburgh; Samy El-Sawah, California State Polytechnic University,

Pomona; Peter .1. Gorder, Kansas State University; Duane Uanselman, University of

Maine; Ashok Iyer, University of Nevada, Las Vegas; Leslie R. Koval, University of

Missouri-Rolla; L. G. Kraft, University of New Hampshire; Thomas Kurfess, Georgia Institute of Technology; Julio C. Mandojana, Mankato State University; Jure

Medanic, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Eduardo A. Misawa, Oklahoma State University; Medhat M. Morcos, Kansas State University; Mark Nagurka,

Marquette University; Carla Schwartz, The Math Works, Inc.; D. Subbaram Naidu,

Idaho State University; Ron Perez, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Murat

Tanyel, Dordt College; Hal Tharp, University of Arizona; John Valasek, Texas A & M

LIniversity; Paul P Wang, Duke University; and Ravi Warrier, GMI Engineering and

Management Institute.

OPEN LINES OF COMMUNICATION

The authors would like to establish a line of communication with the users of

Modern Control Systems. We encourage all readers to send comments and suggestions for this and future editions. By doing this, we can keep you informed of an)?

general-interest news regarding the textbook and pass along interesting comments

of other users.

Keep in touch!

Richard C. Dorf

Robert H. Bishop

dorf@ece.ucdavis.edu

rhbishop@mail.utexas.edu

About the Authors

Richard C. Dorf is a Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of California, Davis. Known as an instructor who is highly concerned with

the discipline of electrical engineering and its application to social and economic

needs, Professor Dorf has written and edited several successful engineering textbooks and handbooks, including the best selling Engineering Handbook, second

edition and the third edition of the Electrical Engineering Handbook. Professor

Dorf is also co-author of Technology Ventures, a leading textbook on technology

entrepreneurship. Professor Dorf is a Fellow of the IEEE and a Fellow of the

ASF.E. He is active in the fields of control system design and robotics. Dr. Doif

holds a patent for the PIDA controller.

Robert H. Bishop is the Chairman of the Department of Aerospace Engineering

and Engineering Mechanics at The University of Texas at Austin. He holds the Joe J.

King Professorship and in 2002 was inducted into the UT Academy of Distinguished Teachers. A talented educator, Professor Bishop has been recognized for his

contributions in the classroom with the coveted Lockheed Martin Tactical Aircraft

Systems Award for Excellence in Engineering Teaching. He received the John Leland

Atwood Award from the American Society of Engineering Educators and the

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, which is periodically given to

"a leader who has made lasting and significant contributions to aerospace engineering education." Professor Bishop is a Fellow of AIAA and is active in the IEEE and

ASEE. He is a distinguished researcher with an interest in guidance, navigation, and

control of aerospace vehicles.

XXV

Introduction to Control

Systems

1

1.1

Introduction

2

1.2

Brief History of Automatic Control

1.3

Examples of Control Systems

1.4

Engineering Design

1.5

Control System Design

4

8

16

17

1.6

Mechatronic Systems

1.7

The Future Evolution of Control Systems

20

1.8

Design Examples

1.9

Sequential Design Example: Disk Drive Read System

1.10

Summary

24

25

28

30

PREVIEW

In this chapter, we discuss open- and closed-loop feedback control systems. A control system consists of interconnected components to achieve a desired purpose. We

examine examples of control systems through the course of history. These early systems incorporated many of the same ideas of feedback that are employed in modern

manufacturing processes, alternative energy, complex hybrid automobiles, and sophisticated robots. A design process is presented that encompasses the establishment of goals and variables to be controlled, definition of specifications, system

definition, modeling, and analysis. The iterative nature of design allows us to handle

the design gap effectively while accomplishing necessary trade-offs in complexity,

performance, and cost. Finally, we introduce the Sequential Design Example: Disk

Drive Read System. This example will be considered sequentially in each chapter of

this book. It represents a very important and practical control system design problem

while simultaneously serving as a useful learning tool.

DESIRED OUTCOMES

Upon completion of Chapter 1, students should:

•

Possess a basic understanding of control system engineering and be able to offer

some illustrative examples and their relationship to key contemporary issues.

3

Be able to recount a brief history of control systems and tiieir role in society.

U

Be capable of discussing the future of controls in the context of their evolutionary pathways.

Recognize the elements of control system design and possess an appreciation of

controls in the context of engineering design.

3

1

2

Chapter 1

Introduction to Control Systems

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Engineering is concerned with understanding and controlling the materials and

forces of nature for the benefit of humankind. Control system engineers are concerned with understanding and controlling segments of their environment, often

called systems, to provide useful economic products for society. The twin goals of

understanding and controlling are complementary because effective systems control requires that the systems be understood and modeled. Furthermore, control engineering must often consider the control of poorly understood systems such as

chemical process systems. The present challenge to control engineers is the modeling and control of modern, complex, interrelated systems such as traffic control systems, chemical processes, and robotic systems. Simultaneously, the fortunate

engineer has the opportunity to control many useful and interesting industrial automation systems. Perhaps the most characteristic quality of control engineering is

the opportunity to control machines and industrial and economic processes for the

benefit of society.

Control engineering is based on the foundations of feedback theory and linear

system analysis, and it integrates the concepts of network theory and communication theory. Therefore control engineering is not limited to any engineering discipline but is equally applicable to aeronautical, chemical, mechanical, environmental,

civil, and electrical engineering. For example, a control system often includes electrical, mechanical, a n d chemical components. Furthermore, as the understanding of

the dynamics of business, social, and political systems increases, the ability to control

these systems will also increase.

A control system is an interconnection of components forming a system configuration that will provide a desired system response. The basis for analysis of a system

is the foundation provided by linear system theory, which assumes a cause-effect relationship for the components of a system. Therefore a component or process to be

controlled can be represented by a block, as shown in Figure 1.1. The input-output

relationship represents the cause-and-effect relationship of the process, which in turn

represents a processing of the input signal to provide an output signal variable, often

with a power amplification. An open-loop control system uses a controller and an actuator to obtain the desired response, as shown in Figure 1.2. An open loop system is

a system without feedback.

An open-loop control system utilizes an actuating device to control the process

directly without using feedback.

FIGURE 1.1

Process to be

controlled.

FIGURE 1.2

Open-loop control

system (without

feedback).

Input

Desired output

response

Outpui

Process

CJontroller

Actuator

Process

Output

Section 1.1

Desired output

response

FIGURE 1.3

Closed-loop

feedback control

system (with

feedback).

3

Introduction

Controller

Measurement output

Actuator

Sensor

outpu;

Feedback

In contrast to an open-loop control system, a closed-loop control system utilizes

an additional measure of the actual output to compare the actual output with the

desired output response. The measure of the output is called the feedback signal. A

simple closed-loop feedback control .system is shown in Figure 1.3. A feedback control system is a control system that tends to maintain a prescribed relationship of

one system variable to another by comparing functions of these variables and using

the difference as a means of control. With an accurate sensor, the measured output

is a good approximation of the actual output of the system.

A feedback control system often uses a function of a prescribed relationship between the output and reference input to control the process. Often the difference

between the output of the process under control and the reference input is amplified

and used to control the process so that the difference is continually reduced. In general, the difference between the desired output and the actual output is equal to the

error, which is then adjusted by the controller. The output of the controller causes the

actuator to modulate the process in order to reduce the error. The sequence is such,

for instance, that if a ship is heading incorrectly to the right, the rudder is actuated to

direct the ship to the left. The system shown in Figure 1.3 is a negative feedback control system, because the output is subtracted from the input and the difference is

used as the input signal to the controller. The feedback concept has been the foundation for control system analysis and design.

A closed-loop control system uses a measurement of the output and feedback of

this signal to compare it with the desired output (reference or command).

Due to the increasing complexity of the system under control and the interest in

achieving optimum performance, the importance of control system engineering has

grown in the past decade. Furthermore, as the systems become more complex, the interrelationship of many controlled variables must be considered in the control

scheme. A block diagram depicting a multivariable control system is shown in

Figure 1.4.

A common example of an open-loop control system is a microwave oven set to

operate for a fixed time. An example of a closed-loop control system is a person

steering an automobile (assuming his or her eyes are open) by looking at the auto's

location on the road and making the appropriate adjustments.

The introduction of feedback enables us to control a desired output and can improve accuracy, but it requires attention to the issue of stability of response.

4

Chapter 1

Introduction to Control Systems

Error

Desired "

*

Comparison

Con trailer

Actuator

Process

response , , ^

.

Actual

output

i

Sensor

Measurement output

FIGURE 1,4

Feedback

Multivariate control system.

1.2 BRIEF HISTORY OF A U T O M A T I C CONTROL

The use of feedback to control a system has a fascinating history. The first applications of

feedback control appeared in the development of float regulator mechanisms in Greece

in the period 300 t o I R.C. [1,2,3]. The water clock of Ktesibios used a float regulator

(refer to Problem 1.11). An oil lamp devised by Philon in approximately 250 B.C. used a

float regulator in a n oil lamp for maintaining a constant level of fuel oil. Heron of

Alexandria, who lived in the first century A.D., published a book entitled Pneumatica,

which outlined several forms of water-level mechanisms using float regulators [1].

The first feedback system to be invented in modern Europe was the temperature regulator of Cornells Drebbel (1572-1633) of Holland [1]. Dennis Papin

(1647-1712) invented the first pressure regulator for steam boilers in 1681. Papin's

pressure regulator "was a form of safety regulator similar to a pressure-cooker valve.

The first automatic feedback controller used in an industrial process is generally agreed to be Tames Watt's flyball governor, developed in 1769 for controlling

the speed of a steam engine [1,2]. The all-mechanical device, shown in Figure 1.5,

Shaft axis

"Measured

Boiler

Metal

ball

Output

shaft

Engine

FIGURE 1.5

Watt's flyball

governor.

Section 1.2

Brief History of Automatic Control

Water

Float

FIGURE 1.6

Water-level float

regulator.

Valve

measured the speed of the output shaft and utilized the movement of the flyball to

control the steam valve and therefore the amount of steam entering the engine. As

depicted in Figure 1.5, the governor shaft axis is connected via mechanical linkages and beveled gears to the output shaft of the steam engine. As the steam engine output shaft speed increases, the ball weights rise and move away from the

shaft axis and through mechanical linkages the steam valve closes and the engine

slows down.

The first historical feedback system, claimed by Russia, is the water-level float

regulator said to have been invented by I. Polzunov in 1765 [4). The level regulator

system is shown in Figure 1.6. The float detects the water level and controls the valve

that covers the water inlet in the boiler.

The next century was characterized by the development of automatic control

systems through intuition and invention. Efforts to increase the accuracy of the

control system led to slower attenuation of the transient oscillations and even to

unstable systems. It then became imperative to develop a theory of automatic control. In 1868, J.C. Maxwell formulated a mathematical theory related to control theory using a differential equation model of a governor [5]. Maxwell's study was

concerned with the effect various system parameters had on the system performance. During the same period, I. A. Vyshnegradskii formulated a mathematical

theory of regulators [6].

Prior to World War II, control theory and practice developed differently in the

United States and western Europe than in Russia and eastern Europe. The main impetus for the use of feedback in the United States was the development of the telephone system and electronic feedback amplifiers by Bode, Nyquist, and Black at

Bell Telephone Laboratories [7-10,12].

Harold S. Black graduated from Worcester Polytechnic Institute in 1921 and

joined Bell Laboratories of American Telegraph and Telephone (AT&T). In 1921,

the major task confronting Bell Laboratories was the improvement of the telephone

system and the design of improved signal amplifiers. Black was assigned the task of

linearizing, stabilizing, and improving the amplifiers that were used hi tandem to

carry conversations over distances of several thousand miles.

6

Chapter 1

Introduction to Control Systems

Black reports [8]:

Then came the morning of Tuesday, August 2,1927, when the concept of the negative

feedback amplifier came to me in a flash while I was crossing the Hudson River on the

Lackawanna Ferry, on my way to work. For more than 50 years I have pondered how

and why the idea came, and I can"t say any more today than I could that morning. All 1

know is that after several years of hard work on the problem, I suddenly realized that if

1 fed the amplifier output back to the input, in reverse phase, and kept the device from

oscillating (singing, as we called it then), I would have exactly what I wanted: a means

of canceling out t h e distortion in the output. I opened my morning newspaper and on a

page of The New York Times 1 sketched a simple canonical diagram of a negative feedback amplifier plus the equations for the amplification with feedback. I signed the

sketch, and 20 minutes later, when I reached the laboratory at 463 West Street, it was

witnessed, understood, and signed by the late Earl C. Blessing.

i envisioned this circuit as leading to extremely linear amplifiers (40 to 50 dB of

negative feedback), but an important question is: How did I know I could avoid selfoscillations over very wide frequency bands when many people doubted such circuits

would be stable? My confidence stemmed from work that I had done two years earlier

on certain novel oscillator circuits and three years earlier in designing the terminal circuits, including t h e filters, and developing the mathematics for a carrier telephone system

for short toll circuits.

The frequency d o m a i n was used primarily to describe the operation of the feedback amplifiers in t e r m s of bandwidth and other frequency variables. In contrast,

the eminent mathematicians and applied mechanicians in the former Soviet Union

inspired and dominated the field of control theory. Tlierefore, the Russian theory

tended to utilize a time-domain formulation using differential equations.

The control of a n industrial process (manufacturing, production, and so on) by

automatic rather than manual means is often called automation. Automation is

prevalent in the chemical, electric power, paper, automobile, and steel industries,

among others. The concept of automation is central to our industrial society. Automatic machines are used to increase the production of a plant per worker in order to

offset rising wages and inflationary costs. Thus industries are concerned with the

productivity per worker of their plants. Productivity is defined as the ratio of physical output to physical input [26]. In this case, we are referring to labor productivity,

which is real output per hour of work.

The transformation of the U.S. labor force in the country's brief history follows

the progressive mechanization of work that attended the evolution of the agrarian

republic into an industrial world power. In 1820, more than 70 percent of the labor

force worked on the farm. By 1900, less than 40 percent were engaged in agriculture.

Today, less than 5 percent works in agriculture [15].

In 1925, some 588.000 people—about 1.3 percent of the nation's labor force—

were needed to mine 520 million tons of bituminous coal and lignite, almost all of it

from underground. By 1980, production was up to 774 million tons, but the work

force had been reduced to 208,000. Furthermore, only 136,000 of that number were

employed in underground mining operations. The highly mechanized and highly

productive surface mines, with just 72,000 workers, produced 482 million tons, or 62

percent of the total [27].

A large impetus to the theory and practice of automatic control occurred during

World War II when it became necessary to design and construct automatic airplane

Section 1.2

Brief History of Automatic Control

7

piloting, gun-positioning systems, radar antenna control systems, and other military

systems based on the feedback control approach. The complexity and expected performance of these military systems necessitated an extension of the available control techniques and fostered interest in control systems and the development of new

insights and methods. Prior to 1940, for most cases, the design of control systems was

an art involving a trial-and-error approach. During the 1940s, mathematical and analytical methods increased in number and utility, and control engineering became an

engineering discipline in its own right [10-12].

Another example of the discovery of an engineering solution to a control system

problem was the creation of a gun director by David B. Parkinson of Bell Telephone

Laboratories. In the spring of 1940, Parkinson was a 29-year-old engineer intent on

improving the automatic level recorder, an instrument that used strip-chart paper to

plot the record of a voltage. A critical component was a small potentiometer used to

control the pen of the recorder through an actuator.

Parkinson had a dream about an antiaircraft gun that was successfully felling

airplanes. Parkinson described the situation [13]:

After three or four shots one of the men in the crew smiled at me and beckoned me to

come closer to the gun. When I drew near he pointed to the exposed end of the left

trunnion. Mounted there was the control potentiometer of my level recorder!

The next morning Parkinson realized the significance of his dream:

If my potentiometer could control the pen on the recorder, something similar could,

with suitable engineering, control an antiaircraft gun.

After considerable effort, an engineering model was delivered for testing to the

U.S. Army on December 1,1941. Production models were available by early 1943,

and eventually 3000 gun controllers were delivered. Input to the controller was provided by radar, and the gun was aimed by taking the data of the airplane's present

position and calculating the target's future position.

Frequency-domain techniques continued to dominate the field of control following World War II with the increased use of the Laplace transform and the complex frequency plane. During the 1950s, the emphasis in control engineering theory was on the

development and use of the i'-plane methods and, particularly, the root locus approach. Furthermore, during the 1980s, the use of digital computers for control components became routine. The technology of these new control elements to perform

accurate and rapid calculations was formerly unavailable to control engineers. There

are now over 400,000 digital process control computers installed in the United States

[14, 27]. These computers are employed especially for process control systems in

which many variables are measured and controlled simultaneously by the computer.

With the advent of Sputnik and the space age, another new impetus was imparted to control engineering. It became necessary to design complex, highly accurate

control systems for missiles and space probes. Furthermore, the necessity to minimize the weight of satellites and to control them very accurately has spawned the

important field of optimal control. Due to these requirements, the time-domain

methods developed by Liapunov, Minorsky, and others have been met with great interest in the last two decades. Recent theories of optimal control developed by L. S.

Pontryagin in the former Soviet Union and R. Bellman in the United States, as well

Chapter 1 Introduction to Control Systems

Table 1.1

1769

1800

1868

1913

1927

1932

1941

1952

1954

1957

1960

1970

1980

1983

1990

1994

1997

1998-2003

Selected Historical Developments of Control Systems

James Watt's steam engine and governor developed. The Watt steam engine

is often used to mark the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Great

Britain. During the Industrial Revolution, great strides were made in Lhe

development of mechanization, a technology preceding automation.

Eli Whitney's concept of interchangeable parts manufacturing demonstrated

in t h e production of muskets. Whitney's development is often considered

to b e the beginning of mass production.

J. C. Maxwell formulates a mathematical model for a governor control of a

s t e a m engine.

H e n r y Ford's mechanized assembly machine introduced for automobile

production.

H. S. Black conceives of the negative feedback amplifier and H. W. Bode

analyzes feedback amplifiers.

H. Ny-quist develops a method for analyzing the stability of systems.

Creation of first antiaircraft gun with active control.

Numerical control (NC) developed at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

for control of machine-tool axes.

G e o r g e Devol develops "programmed article transfer." considered to be the

first industrial robot design.

Sputnik launches the space age leading, in time, to miniaturization of

computers and advances in automatic control theory.

First U n i m a t e robot introduced, based on Devol's designs. Unimate

insta lied in 1961 for tending die-casting machines.

State-variable models and optimal control developed.

R o b u s t control system design widely studied.

Introduction of the personal computer (and control design software soon

thereafter) brought the tools of design to the engineer's desktop.

Expojt t-orienled manufacturing companies emphasize automation.

Feedback control widely used in automobiles. Reliable, robust systems

d e m a n d e d in manufacturing.

First e v e r autonomous rover vehicle, known as Sojourner, explores the

M a r t i a n surface.

A d v a n c e s in micro- and nanotechnology. First intelligent micromachincs

are d e v e l o p e d and functioning nanomachines are created.

as recent studies of robust systems, have contributed to the interest in time-domain

methods. It now is clear that control engineering must consider both the time-domain and the frequency-domain approaches simultaneously in the analysis and design of control systems.

A selected history of control system development is summarized in Table 1.1.

1.3 EXAMPLES OF CONTROL S V S T E M S

Control engineering is concerned with the analysis and design of goal-oriented systems. Therefore the mechanization of goal-oriented policies has grown into a hierarchy

of goal-oriented control systems. Modern control theory is concerned with systems

that have self-organizing, adaptive, robust, learning, and optimum qualities.

Section 1.3

9

Examples of Control Systems

Feedback control is a fundamental fact of modern industry and society. Driving

an automobile is a pleasant task when the auto responds rapidly to the driver's commands. Many cars have power steering and brakes, which utilize hydraulic amplifiers for amplification of the force to the brakes or the steering wheel. A simple

block diagram of an automobile steering control system is shown in Figure 1.7(a).

The desired course is compared with a measurement of the actual course in order to

generate a measure of the error, as shown in Figure 1.7(b). This measurement is obtained by visual and tactile (body movement) feedback, as provided by the feel of

the steering wheel by the hand (sensor). This feedback system is a familiar version

of the steering control system in an ocean liner or the flight controls in a large airplane. A typical direction-of-travel response is shown in Figure 1.7(c).

Desired

course

of travel

~v Error

Driver

,

Steering

mechanism

Automobile

Measurement.

and tactile

V isual

(a)

Actual

direction

of travel

(b)

FIGURE 1.7

(a) Automobile

steering control

system, (b) The

driver uses the

difference between

the actual and the

desired direction of

travel to generate a

controlled

adjustment of the

steering wheel.

(c) Typical directionof-travel response.

Desired direction of travel

Actual direction of travel

I

Time, t

(ci

Desired

direction

of travel

Actual

course

of travel

10

Chapter 1

Introduction to Control Systems

A basic, manually controlled closed-loop system for regulating the level of fluid

in a tank is shown in Figure 1.8.The input is a reference level of fluid that the operator is instructed t o maintain. (This reference is memorized by the operator.) The

power amplifier is t h e operator, and the sensor is visual. The operator compares the

actual level with t h e desired level and opens or closes the valve (actuator), adjusting

the fluid flow out, t o maintain the desired level.

Other familiar control systems have the same basic elements as the system

shown in Figure 1.3. A refrigerator has a temperature setting or desired temperature,

a thermostat to measure the actual temperature and the error, and a compressor

motor for power amplification. Other examples in the home are the oven, furnace,

and water heater. I n industry, there are many examples, including speed controls;

process temperature and pressure controls; and position, thickness, composition, and

quality controls [14,17,18].

In its modern usage, automation can be defined as a technology that uses programmed commands to operate a given process, combined with feedback of information to determine that the commands have been properly executed. Automation

is often used for processes that were previously operated by humans. When automated, the process can operate without human assistance or interference. In fact,