ProgressiiiCfiess

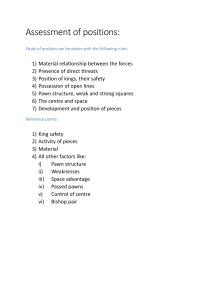

Volume 7 of the ongoing series

Editorial board

GM Victor Korchnoi

GM Helmut Pfleger

GM Nigel Short

GM Rudolf Teschner

2003

EDITION OLMS

m

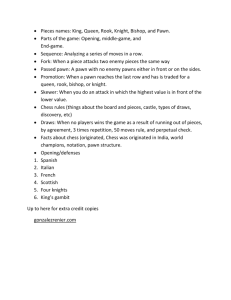

Mark Dvoretsky

Endgame Analysis

School of Chess Excellence l

Edited and translated

by Ken Neat

2003

EDITION OLMS

m

Avolloble by Mak

Dvoretsl<y:

School of Chess Excellence l Endgame Analysis

3-283-00416-1

(Germon Edition: Geheimnlsse gezleffen Schochtrolnings

3-283-00254-1)

School of Chess Excellence 2 Tocflcol Play

3-283-00417-X

(Germon Edition: 11//oderne Schochtoktfk

3-283-00278-9)

School of Chess Excellence 3 Stro1egic Play

3-283-00418-8

(Germon Edition: Gehelmnlsse der Schochstrotegle

3-283-00362-9)

School of Chess Excellence 4 Opening Developments

3-283-00419-6

(Germon Edifion: Theorie und Proxls der Schochportfe

3-283-00379-3)

r

,,

Bibliogrophc i'lformation published by

Die Deutsche Bibliothek

Die Deutsche Blbliothek lists this publication in the

Deutsche Nationalbibliogrofie;

detoil<>ri bibliographic

data is available in the interr'

�.

First edition 2001

Second edition 2003

Copyright © 200 l Edition Oh.

Breitlenstr. l l

·

CH-8634 Ho mbrec111111.011t£urich, Switzerland

All rights reserved. This book Is sold subject to the condition that It shall no t, by way

of trade or otherwise. be lent. re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition

including this condition being mposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed in Germany

Editor and translator: Ken Neat

Typeset: Ar no Nickel·· Edition Marco. 0- l 0551 B erlin

Printed by: Druckerei Frledr. Schmucker GmbH, D-49624 Loningen

Cover: Prof. Poul Konig, D-31137 Hildesheim

ISBN 3-283-00416-1

Contents

Fro m the au thor

....... ........... .................................................................................................

7

Part one

The analysis of adjourned p osit ions ........ ...................................... .............................. 1 O

An adjou rnment sessio n that deci ded a match ..

.

.

...

. .. ... .

. . . . .. 1 1

Don't hi nder o ne ano ther! ... . .. . . . ...... ... . ... . . . . . . ....... . ... . ........ . . . .. . .. . . . ... 1 4

Trap s fou nd i n anal ysis . .

. . . . . . ..... . . . ... .

. . . . . .. .. . . ... ... .

18

Prize for the b est ending

.

.. .

.

.

.

.. .

..

. 21

A stu dy generated by m istake

.

.

. .

.. . .

25

I c hoose a p lan that is not the strongest!

.

.

.

28

Ho w h ard it is to wi n a wo n position!

.. .

.

. .

. .

.

. .

33

An i ncomp lete analysis

..

.

.

.

. .

39

Give me an envelop e, p lease

.... .... .

. ...... ..

.

.

43

Even grandmasters make mistakes . ... . .. ... . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . ................ . . . .

. 48

Flipp ancy is pu ni shed! ....... .. ............ ... . .. . .. . . .. .. . ... . ... . . . . . . . . .

52

Is it p os�ib le to be ex cessively seri ou s? ... . . . . . .. . ... . . .. . . . . . . .. . .. .... . . . . .. 60

The b enefit o f ' ab stract' knowledge . . .. .. . ..

..

. . ... . . .. .

. . ....

64

A diffi cu lt analysis ..

.

.

68

Exerci ses fo r analysi s . . . . ...... .......... .. . .. . .. . . ...

.. ....... ....... .. ... ... ... .. ... . . . .... ...... 73

.

. .

. ..... ..

. . .... .

...

..

.... .....

. . ...

........ ...............

........ ....... ....

......... .

...

. ..

. .

..

... ...

........ . . . .

.

. ...

. .

.....

.

....

. ............ .............. ......... ....

....

.

.

. ...

............. ............ ................ . ......................

..

.

.

.. ....

.

...

.

.

. ........

................. .

.. . . ..............

....... ....... ............... .........................................

.........

.......................

............

.

....

...

.

.

. .... ........ . ............... ... ...... ...... .... ............

...... ...................................... ...... ..... . ...............

.. ................................ ...

.

....

.

...

.. ....

. ..... .

. ... .

...

.... ..

.. .

..........

.

... . ..

. ....

. .

...... .... .

. ......

.

..

...... ........ ......

. .

.....

.. ..

..... .

. . . . .

..

.... .. . . .

..

.. .. .. ....

.

. .. . . ..

... ......

.

..........

...................................... .......................................... .........................

... .

..

. ..

.......

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

Part two

The endgame ..., ............................................................................................................... 76

The king establishes a record

.. .. .... .

Commentari es withou t variations .. .. ........

Mi ned squ ares ... . . . . .. . ........ .. .

My first analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

The transiti o n i nto a p awn endgame . .

T h e fortress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The reward fo r tenaciou s defence . . . . .

The p ri nciple of two weaknesses . . . . . .

Twin endi ngs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Defence b y frontal attack .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Rook against p awns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A great master of the endgame . . ......

The strongest piece is the rook! . .. .. . . ..

............

..

. . .....

.. . . .

.

.

.. .

.

...

.

.

.

.

...................................

...........

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

5

.

.

. .

. . . . . .... . . ...... ....

. . . . . . . . . . ..... ... . . .

77

83

87

90

96

. . . ........ . . . . . . . . 102

.. ............ . . . .. . . 1 1 3

. . . . ......... . . . ... 120

. .. . . .............. 124

. . . . . . . . . . . ... . . . .. 1 28

.. . . . . . . . . . . . . ..... 1 33

................... 1 38

. . ................. 141

........ .. .. ......

.

. ..... ............ .......... ..........

............

.... .............

················ ·····

------

L ike-co lou r b ishops

Opposite-colou r b ishops

What remain ed off-stage

An amaz in g coin ciden ce

Aerobatics

Exercises fo r an alysis

�------

..........................................................................................................

.......................... ........................................................................

............................ ......................................................................

..................................................................................................

........................................................................................................................

......................................................................................................

1 46

1 49

1 56

1 61

1 67

1 72

P art three

Studies

176

............................................................................................................................

L et trainin g commence!

Deep calcu lation

Stu dies by g ran dmasters

Stu dy i deas in practice

P laying ex ercises

Recipro cal p laying

Ex actly as in a stu dy

The 'brilliance an d poverty' of stu dies

Ex ercises fo r an alysis

...................................................................................................

..................................................... .........................................................

.................................................................................................

1 77

1 85

1 90

1 93

1 96

200

203

207

21 O

........................ .............................................................................

.............................................................................................................

............................................................................................................

......................................................................... ...............................

.............................................................................

......................................................................................................

Solutions to exercl ses

....................... . ......... . ...................... . . ................ ... . .....................

215

App en dix

Index b y material

Ind ex o f ex erci ses by thin kin g skills an d typ es o f prob lems to be so lved

In dex of pl ayers an d an alysts

.............................................................................................................

.......................

255

256

258

..........................................................................................

'.6-_

------

�------

From the Author

Develop ment of the stron g aspects of

p lay, an d the creation of a p erson al style,

with the defin ite elimin ation o f weakn esses.

Max i mu m activity an d in depen den ce,

an d a creative appro ach to an y p rob lems

b ein g solved.

Con stan t train in g, the solvin g o f sp ecial

ex ercises, aimed at develop in g n ecessary

thin kin g skills.

I mp rovement in an alytical mastery, in

p articu lar a thorou gh an alysis o f on e' s own

games.

C omp etitiven ess .. .

The correctn ess of theo retical views can

on ly be checked in practice. The resu lts

came un exp ectedly qu ickly. I b egan serious

train in g wo rk in 1 972, an d alre ady in 1 975

Valery Chekhov became world jun ior cham­

p ion . S oon this title was also won by Artu r

Yu sup ov an d Sergey Dolmatov, an d Alyo sha

Dreev twice won the world ' cadet' champ i­

ons hip .

T he youn g p layers grew up , an d b e­

came gran dmasters. In 1 986 Yusupov was

a fin alist in the candidates comp etition for

the world champ i onship . But I also did som e

work at this level even earlier. Fou r years of

wo rk with Nana Alexan dria were crown ed

b y her match again st the women's wo rld

champ ion Maya Chib urdan idz e, which

en ded in a d raw. And sub sequen tly Sergey

Dolmatov, Alex ei Dreev, Alexan der Chem in

an d Vadim Zviagin tsev also comp eted in

the world champ ionship can didates even ts.

The life of a train er con sists of con tinu­

ou s travels with his pupils: to train in g

session s, an d competition s. We con stan tly

stu died an d an alysed so methin g, an d at

tim es we obtain ed very in tere stin g resu lts.

Ou r searchin gs an d fin ds in the openin g

A gran dmaster ann otates a game. He gives

COITl> licated variation s, but does n o t always

exp lain how they were foun d, or what ideas

an d laws are con cealed b ehin d them. This

is un derstan dab le: exp erien ced p layers

sen se certain thin gs intu itively, an d regard

mu ch as going withou t sayin g. Bu t for a

trainer it is the 'co mmon tru ths' that are the

most imp ortan t.

On e day I rea lised that I n o w no lon ger

loo k at chess as I u sed to do , bu t with

di fferen t eyes from when I was a practical

player. N o , I still value var iati on s an d

p recise an alysis. Withou t them an y gen eral

con siderati on s b eco me un defen ded an d

unproven , and are left han gin g in the air.

But I can no lon ger avoid seekin g the

essen ce of the position that is con cealed

b ehin d the variation s, the secret forces that

direct the p lay. M o reo ver, n o t on ly the

pu rely chess ideas an d techn iqu es, bu t also

the ru les of thin kin g, an d the p rin cp les of

the ration al searchin g for an d takin g of

decision s.

Train in g wo rk attracted me at an early

age. Gradu ally I gave up p layin g, without

even man agin g to b eco me a gran dmaster

(for a p layer with a ratin g of 2540 in the

seven ties, this was a qu ite realisab le aim ). I

was immediately ab le to formu late the main

p rinciples, which form the b asis o f a system

of p reparation for youn g p layers. Here are

some of these p rincip les:

The all-roun d develop ment o f p erson al­

ity, an d a battle not on ly with chess

deficien cies, bu t also human on es.

Rej ee tion of the con cen tration of effo rts

on the op enin g alone" , which, alas is typ ical

of ou r day; all-roun d p rep aration , an d chess

eru d ition .

7.

and the middlegame are a separate theme.

training is essential, by solving exercises on

In this book I should like to acquaint the

the

topic

in

question.

The

outstanding

readers with the most interesting analyses,

mathematician and teacher George Polya

pieces (adjourned positions, endings and

cal skill, like swimming, skiing or playing the

relating to positions with a small number of

wrote: 'The solving of problems is a practi­

studies). To remember how these analyses

piano; it can be learned only by imitating a .

were carried out, and to show what is

good example and by constantly practis­

hidden behind the variations found. After

ing'. It is hardly advisable to trustingly play

reading the book, you will, I hope, agree that

through the book, variation by variation. It is

player without learning to analyse deeply

actively in

it is impossible to become a good chess

far more useful and

and accurately. To see how attractively

to join

find something

yourself, and try to refute certain conclu­

(although also not easily) the secrets of a

position were deciphered. To learn

interesting

the analysis,

sions of the author. In this you will be helped

the

by the tests for independent solving (in your

finally, to increase and consolidate your

sis (moving the pieces on the board), which

methods and techniques of analysis. And

head, without moving the pieces) or analy­

knowledge in the field of the endgame.

are offered in the book. They are divided

At the present time, high-ranking com­

into 'questions' (signified by a letter

petitions have begun to be held under new

'Q'

followed by the section of the book and the

regulations - now games are hardly ever

number of the question), replies to which

adjourned. In view of this, the first part of the

constitute the subsequent text, and 'exer­

book. devoted to adjourned positions, may

cises' (signified by a letter

'E')

with replies at

seem obsolete. Nevertheless, I have de­

the end of the book.

(restricting myself only to purely chess

'solving' and 'analysis' is, of course, arbi­

cided

to leave it in its previous form

The boundary between problems for

corrections) for the following reasons:

1)

trary, and depends on the level of your

Many of the principles of analysing

mastery. It is useful first to try and solve

book, are essentially general principles of

possibly you will successfully cope with this.

adjourned positions, as described in the

exercises

chess analysis. And without improvement in

for

analysis

in

your

head -

But in difficult problems 'for solving' you

analysis, as already mentioned, it is impos­

should move the pieces on the board - in

sible to become a genuine master.

this way you will gain practice in analysis.

2)

The adjournment of games and their

You will also encounter questions, the

subsequent analysis is a large and very

replies to which are almost impossible to

interesting part of the real life of a chess

calculate precisely, and can only be guessed.

, The book is aimed at players of high

They are designed to develop your positional

feeling, or intuition.

player, and we should not forget our history.

standard - many of the examples described

And the third part of the book describes

are very difficult. But I think that the less

another

skilled reader will also find in it pages that

are accessible and interesting to him.

by

of

training,

one

that

is

aithough it is

extremely effective - the playing of posi­

tions.

For the development and consolidation

of the thinking skills needed

form

comparatively little-known,

a chess

At the end of the book there are two

player, and also with the aim of soundly

thematic indexes. The first index groups

positions by material. If you wish to delve

mastering and consolidating any material

(not only in chess, but in chess especially!),

into some particular type of endgame, you

8

authors, this number is trivially small, but

will easily pick out all the endings of the

given type.

even so it is pleasant to eliminate them.

by the skills which they are designed to

life of an author has become much simpler.

With the appearance of computers, the

The second index groups the exercises

If you want to improve the text. correct

develop, by the type of problems to be

commentaries,

solved. If you tend constantly to underesti­

remove

an

unsuccessful

example, or add another chapter - you

mate your opponent's resources, or if you

switch on the computer, make the desired

are not always able to judge correctly who is

favoured by an exchange, you will be able

changes, and you have a new, improved

exercises from the corresponding section.

making such corrections over a period of

version of the book. I have been constantly

to try and solve, one after another, all the

many years, and the results of them are

The list of skills is, of course, incomplete,

and should not be taken as a precise

now before you.

instrument, which I use in classes.

feedback. A trainer gives to his pupils, but

classification.

This is merely a working

Teaching

is

always

a

process

with

also gains much from his contact with them,

From the moment when· the first edition

of this book was published, many years

and constantly learns himself. This book

games have been played and instructive

active creative participation of my friends

should like to acquaint the readers. The

priate) Artur Yusupov, Sergey Dolmatov,

would have been impossible without the

have passed. During this time interesting

(the word 'pupil' is now somehow inappro­

analyses have been made, with which I

Nana Alexandria and many others. They

new edition gives me the opportunity to

are the main heroes of the book,

include fresh fragments and even entire

chapters.

In

addition,

colleagues

and

effectively its co-authors. The friendship

have

and joint work with them has comprised the

pointed out to me some two to three dozen

analytical inaccuracies and mistakes. For a

main meaning of my life, and has made me

happy. To all of them I am sincerely grateful.

work in which there are no examples at all

that have been copied from books by other

9

------- ----�-· --------Part One

The Analysis of Adjourned Position�

The gong ha s sounde d - the game is

adjour ne d. The se cre t moved is sea le d, the

cl ocks stoppe d, and the score sheets con­

ceale d in the enve lope. The adjour ne d

position i s now lodge d i n your thoughts a nd

will not give you any peace until it is

resu me d.

I m me dia tel y a ma ss of pr oblems ar ises.

There is never su ff icient time for a na lysis.

Sometime s you a ga in ha ve to sit down at

the boar d with in two to three hour s, and

dur ing the break you al so have to find time

to ea t. With one hand you h old your for k,

and with the other you move the p ieces on

your pocket se t. It is not much easier even

when there are special days set aside for

a djour nmen ts. You have to prepare for your

ne xt few ga me s, pla y them, and final ly,

simpl y re lax. Can you find mu ch time for the

a djour ne d position? There is an eter na l

dile mma at a tour na me nt: sleep or ana lysis.

10

A p la yer is oblige d to be a ble to ana lyse

his ad jour ned games independe ntly, bu t

sometimes he al so ha s to wor k in a tea m.

Y our fr ie nd or tra iner joins in the stu dy of the

p osition, or perhap s you your se lf per for m

the role of trainer . In team competitions it

often happens that se veral people simulta­

neously ta ke par t in the ana lysis. Joint wor k

must be wel l arra nge d.

Dur ing my year s of p la ying and tra ining

wor k I have accumulated e xper ience of

solving both these 'or ganisa tional ' prob­

le ms, as weM as creative , purely chess

pr oblems. I shou ld now like to share th is

e xper ience . After master ing the technique

of ana lysis, and the pr inciple s of its or gani­

sation and implementation, you will be a ble

to r educe to the minimu m th ose u np lanne d

losses a n d increasingly often enjoy unex­

pected ga ins dur ing the resu mp tion.

An Adjo u rnment Session that

Decided a Match

If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts; but if he

will be content to begin with doubts, he shall end in certainties.

Francis Bacon

For the moment the standa rd of women's

pl ay is in ferior to men' s, but on the other

han d the intensity of the stru ggle in wom­

en's competitions is very high, and short

draws are extremely rare. Many games are

adjou rned, so that their trainers have a hard

time of it. I came to realise this when I

helped gran dmaster Nana Alexan dria in the

ln terzonal Tou rnament of 1979 , in the

Candidates Matches a year later, an d

fin ally, in the match for the world champ ion ­

ship against Maya Chibu rdanidze. As an

example, in the quarter-final match Alexan­

dri a-A khmylovskaya ou t of nine games no

less than eight(!) were adjourned.

It is no secret that, in events at su ch high

level, the players (male or female) rarely

have only one help er. In the 19 80 can di­

dates semi-final match, those working with

N ana, ap art from the au thor of these lines,

were Viktor Gavrikov and David Dzhanoev.

Her opp onent Marta Litinskaya was helped

by the master p layers Zhelyandinov, Sher

and Bu tu rin . Towards the end of the match

gran dmaster A drian Mikhalchishin was also

su mmoned to help Litinskaya.

Ten games - the 'n ormal time' of the

match- did not brin g an advantage to either

of the opp onents: 5-5. Two additional

games were stipulated. The first of these

took an extremely tense course, an d was of

course adjourned.

Alexandria - Litinskaya

Women's Can di dates Match

1 1 th game, Vilnius 1980

There was no particu lar dou bt about Litin s­

kaya's sealed move.

41

:b2!

Black cuts off the enemy kin g and intends

42 . . . .i. d5 with the threats of 43 . l:t g2+ or

43 . @ as and 44 . . l:t fbS.

..

..

.

Q 1 -1 . C alculate 2 f5.*

•

Remember that replies to tests signified by a

letter 'Q' ('question') are given in the subse­

quent text. You are recommended to put the

book to one side for the moment, to try and

answer the question yourself, and only then to

read further.

The atte mpt to play for a passe d e-pa wn

doe s not succee d: 42 f5?! exf5 43 i.xf5

i. d51? (threatenin g 43 . . . J: e 2) 44 e6 i. xe 61

45 i. xe 6 J:t b6 46 J:t d7 J:t f6. However, the

position whe re Bla ck is the e xchange u p ,

a risin g after 47 i. d5 J:t fxd6 4 8 l:1 xd6 .!:[ xd6

49 i. f3, is drawn, accordin g to the ory. As

grandma ste r J oe l Lau tie r pointe d out, the

same drawn position also arise s after

43 . . . i::t g81? (instea d of 43 . . . i. d5) 44 i::t xg8+

i. xg8 45 e6 i. xe 6 46 he6 J:t b6.

In the e vent of 42 i. f7 Bla ck doe s not pla y

42 . . . i. d5? becau se o f 4 3 f5, and not

42 . . . @ c7? (hopin g for 43 i. xe 6+?1 @ c6)

43 i.e B +!, when the king ha s to return to

b8, but 42 . . J:t dB!, when the threat . of

. . . i::t d7-c7 is highly unplea sant.

i. e41

42

White prevents 42 . . . i. d5 (43 i. xd5 e xd5

44 e 6), but in return a llows . . . h6-h5-h4.

42

h51

Now 43 i::t h7 is n o t good in vie w of

43 . . . : g8. After join tly lookin g at the natural

continua tion 43 i.f3 l:l h8 and e sta blishin g

tha t White' s position wa s prefera ble , al­

though the opponent apparently ha s a

draw, we split u p to go and have a re st.

G randmaster Andrei U/lenthal recom­

mended beginning the analysis of such

po sitions by answering the question:

'D o I have a secure draw?'. Re me mbe rin g

this a dvice , I de cide d to che ck more

carefu lly the varia tion 43 i. f3 h4 44 gxh4.

Obviously, 44 . . . l:t xf4? is not possible on

account of 45 l:t g8+ @ c7 46 l:t c8+ @d7

(46 . . . @ b6 47 l:t b8+ and 48 l:t xb2) 47

i.c6+ @e7 48 i::t e8 ma te . But on the other

hand there is 44 . . i::t b3! , an d on ly if 45 @ g2

(or 45 i. g2) 45 . . . l bf4. N ow the black rook

is defende d an d 46 l:t g8+ @ c7 47 l:t c8+

@ b6 is no longe r dange rous. He re White

probably sti ll ha s to fight for e qua lity, since

the bla ck rooks are active, an d in case of

ne ce ssity the passe d h-pawn can be

stoppe d by the bishop from b 1 .

.

.12

I wante d to find some thin g more re lia ble . I

re turne d to the start of the varia tion an d

soon discovere d a rathe r unexpecte d, a l­

thou gh also not difficult idea .

Q 1-2. What is this ide a?.

Since 43 i.f3 doe s not force 43 . . . l:t h8, it

ha s n o particular point.

i.c61

43

White intends to weave a ma ting ne t by

playing 44 tll b5!

2

Now after 43 . . . h4 it is possible to force a

dra w: 44 tll b5 i::t xb5 (force d) 45 i. xb5

hxg3 46 l:t xg3 l:t xf4 47 i.c6. If instead

43 . . . : b6 (with the ai m of preventing

44 tll b5), then 44 i. b5, an d the rook is

trapped. However, after 44 . . . h4 (44 ... i. d5

45 @ h2 h4 46 g4!? l:txf4 47 @ h3 i. c6 is

also possible ) 45 gxh4 l:t xf4 46 h5 l:t h4

47 l:t g8+ @a 7 48 tll c8+ @ b7 49 tll xb6

@ xb6 it wouk:I seem that White cannot

convert his pawn advanta ge .

This idea guarantee s White a ga in st de feat,

but, unfortunate ly, a lso doe s not promise

any winnin g chance s. Ne ve rthele ss, when

from the opponent' s 'hea dqua rters' came a

te le phone call with the offer of a draw, the

peace initiative was turne d down. After a ll,

Bla ck might not have sea le d the be st move

(before the re sumption we se riou sly

------

�

studie d, for e xample , 41 .. . : cs followe d by

42 . . . � dS or 42 . . . J: c7). In a ddition , up till·

then in the match the a dvantage in a djourn­

ment analysis ha d been on our side , an d we

realise d that the reje ction of the draw would

a ssist the growth of uncertainty in the

opponent' s ca mp.

When the game wa s resu me d, the diagram

position was reache d. After 43 � c6 Litins­

ka ya thought for se vera l minutes . . .

l:h 8??

43

It is clear tha t White' s idea came as an

unplea sant su rprise to the opponent. Tire d

out by the lengthy and, as it tu rne d out,

fruitle ss home ana lysis, at the board she

fa ile d to see the ma ting threat. Litin skaya

was le t down by the fact that against 43 �f3

she and he r trainers ha d prepare d not

43 . . . h41, but the more modest 43 . . . : h8?!

(a s Mikha lchishin la ter expla ine d, they

instinctively feare d the passe d h-pa wn). In

the new situa tion Litin ska ya a ims for the

plan se lecte d in analysis, but here it proves

to be a se rious m istake.

44

45

lll b5

�xb5

l:xb5

.i.d5?

Black is 'groggy' . 45 . . . h4 wa s e ssentia l, and

if 46 g4 l:lfB. Howe ver, after 46 � c6 hxg3

47 @ g2l (but not 47 l: b7+ @ ca 48 l:a7

be cause of 48 . . . : h2) White has a sign ifi­

cant a dvantage .

.i.d71

h4

46

:ta

47

g4

48

49

f5

gxf 5

An d White soon won.

exf5

-------

Su ch a fa ilu re at a decisive moment of the

match is difficu lt to endure even for a

ha rdene d fighter. It was not su rprising that

in the la st game Alexandria (with Black)

gaine d an ea sy victory and won the ma tch

7-5.

Wha t conclu sions can be drawn from this

story?

1. The quality of home analysis often has

a decisive Influence on the outcome of a

game and even of an entire event.

2. An unexpected Idea, prepared fot' the

resumption, may have a great practical

effect. When choosing between several

roughly equivalent possibilities, con­

sider which of them the opponent will

least exp ect.

3. Be fore delving Into a maz e of varl•

tlons, you should look carefully fot' new

possibilities fot' yourself and fot' the

opponent In the very first moves. It Is

sometimes also wort h return ing to this

examination during the c ourse of subse­

quent analysis. An omission In the Initial

moves usually proves much more seri­

ous, and Influe nces more strongly the

outcome of the game, than an lnco�

pleteness somewhere at the end of a

lengthy variation.

I shou ld like a lso to draw the attention of the

readers (not at a ll throu gh a de sire to boast)

to a by no means a ccidental fa ct: the

decisive idea was not found du rin g the

collective study of the a djourne d position .

The important prin ciple , associa te d with

this, of organising collective ana lysis, will be

d iscussed in the ne xt chapter.

------

�------

Don 't Hinder One Another!

In a dark room it is hard to catch a black cat,

especially if it is not there.

Confucius

Dolmatov - P etursson

European Junior Championship

Groningen 1 978/79

3.

We began analysing 44 l:t a3. We soon saw

that here things were difficult for White.

Then I tried a couple of times to switch to the

analysis of the rook ending, but did not

succeed. Sergey quickly found new chances

in the 44 l:t a3 variation, and we began

checking them together. As a result, by the

resumption we had not in fact learned

anything about the rook ending, whereas

the other way had been analysed exactly,

as far as . . . a win for Black.

44 l:t a3 °f#d4 45 a5 l:t d3 46 .l:.xd3 cxd3

47 a6 (47 °f#f2 'ff c3 48 'ff e3 'f#c2 49 °ff e4

°ff d 1 is also hopeless) 47 . . . d2 48 a7 (48

'f# d1 'f# e3+).

4

The turn to move and the advantage are

with Black: his king is more securely

covered, and his pieces are more actively

placed. There were less than two hours to

go before the start of the resumption, and,

understandably, over dinner Dolmatov and I

were glued to our pocket set.

We quickly established that it was only the

advance of the c-pawn that had to be

seriously feared. After 42 . . . cs 43 a4 harm­

less is 43 . . . i:t a2 44 i:t d31 'tVxf3+ 45 @xf3

l:t.xa4 46 i:t dB ! , when the black king is

unable to take part in the play. But how to

reply to 43 . . . c4 ? Exchanging queens at d5

would seem dangerous, since the opponent

acquires two connected passed pawns.

48 . . . d1 °ff ! 49 aB'ff (49 'f#xd1 'ff xd1 50

aB'ff '@'g4+) 49 . . . 'ff e 1 + 50 @h3 °ff h 1 + 51

@g3 'f#dg1 ! , and Black wins.

Q 1 -3. E valuate 48 .'ir xa 7 (instead of

48...d1'ir).

••

�

We assumed that the capture of the pawn

would thrown away the win: 48 . . . 'ftxa7 49

'ftd3 'fta2 SO 'it>f3 'ftb2 (or SO ...'ftdS+ S 1

'ftxdS exdS S 2 'it>e2 with a draw) S 1 'it>e3!

d1 ._. S2 'ftxd1 'ftxg2 S3 'it'd8 with a drawn

queen ending. However, later it transpired

that here too Black wins with the cunning

check S1 . .. 'irb6+! (instead of S1 . . . d 1 'ft) S2

'it>f3 (S2 'it>xd2 'ftf2+; 52 'it>e2 'ftg 1 )

S 2...'ftc6+ S3 'it>f2 'ftc1 . I t i s well known that

long backwards piece moves are often

overlooked by a player.

What would you have done in our place?

Gone in for a precisely analysed, but losing

continuation, in the hope of a mistake by the

opponent, or played a rook ending about

which nothing was known and which might

also be hopeless?

Incidentally, later I nevertheless looked at

the rook ending. After 42 c5 43 a4 c4 44

'ftxd51 exd5 neither 4S l:t a3 d4 46 as c3

47 a6 l:t d3+! 48 'it>f2 c2 nor 45 l:t bS c3 46

l:t cs d4 47 as c2 48 a6 l:t d3+ 49 'it>f2 l:t c3

will do. 45 l:t b71 is essential, when after

4S .. . 'it>fB White gains an important tempo

for the defence: 46 l:t c7 l:td3+ 47 'it>f2 c3

48 as d4 49 a6 l:t d2+ so 'it>f3 l:t a2 (SO . . .c2

S1 a7) S1 'it>e4 or S1 a7.

45 ... c31 is more dangerous, but here too, by

playing 46 e6, White can hold the position.

43 'ftxdS (instead of 43 a4) 43 . . . exdS 44

l:t b7 also came into consideration.

Clearly we made irrational use of that short

time which we had for analysis, by studying

together only one of two possible branches.

I should have asked Dolmatov to check

independently the 44 J: a3 variation, when

he would not have diverted me from the

rook ending.

And how did Margeir Petursson cope with

the analysis? Even worse than us, as it

turned out. Fortunately for us, the Icelandic

player had been helped (it would be more

correct to say - hindered) by other partici­

pants in the tournament. There can be no

question of any normal analysis, when

•••

---

there are simultaneously several peopl e

sitting at the board. Variations quickly

flash by, with a mass of oversights being

made, especially in the initial moves. The

analysis quickly ends up somewhere far

away, in positions which, though perhaps

interesting, are unlikely to occur.

42

43

1i'e3

44

.l:l.c3

45

<i>h21

1i'd4?1

1i'a4

It was not yet too late to revert to the plan of

advancing the c-pawn: 43 ... 'ftdSI 44 'ftf3

cs.

Black had aimed for this position, thinking it

to be won. At the board Dolmatov easily

discovered· a simple defence that the

opponent had overlooked.

.l:l.e2

And now it is possible to go into the drawn

rook ending which we had examined in our

analysis.

l:txe3

.l:l.c1 1

46

.l:l.xd1

J:txa3

47

48

.!:I.dBi

48 c5 49.:tca .:tc3 50.l:l.dB .:tc4 51 'itg3

.J: c3+ 52 <;tf2 J:I. c1 53 l:t ca l:!. c2+. Draw

•••

Alexandria - Litinskaya

Women's Candidates Match

8th game, Vilnius 1 980

s

==

Traps Fou nd i n Analysis

I do not like a fatal outcome. I will never tire of life.

Vladimir Vysotsky

The objective evaluation of an adjourned

position will often be unfavourable for us.

We establish that with correct play the

opponent is bound to convert his advan­

tage (or save the game - in an inferior

position). In such instances it is very

important to help him to go wrong. Even a

simple trap may succeed, if It comes as

a surprise to th e opponent. But if he sees

through it, you should not be distressed.

Perhaps the next time you will be luckier.

Romanishin - Dvoretsky

USSR Championship Semi-Final,

Odessa 1 972

8

48

.

48

49

50

51

Oleg Romanishin sealed the obvious check

with his queen.

'ifh7+

There could be no doubt that in reply to

48 . . @ea White would not 11ab the pawn

(49 'l!lxh6? '!We2+ so @gs '!We3+ S1 @g6

'!Wxg3+), but would first play 49 '!Wg6+!, in

order after 49 . . . @d8(e7) SO '!Wxh6 '!We2+

S1 @gs '!We3+ S2 @g6 �xg3+ to block with

the queen at gs with check. And if Black

does not take the g3 pawn, then, as it is

easy to see, the white king escapes from

the pursuit, and the two extra pawns

remain.

There was no point in going along t o the

resumption in order to check Romanishin's

technique in such a simple situation. If

Black decided not to resign, he would have

to find a continuation that promised at least

some practical chance, however weak.

'ilt'g6+1

'ifxh6

�h51

�ea

�7

'ilt'e4+1 ?

Black resigned. He would have also have

had to capitulate after S1 �f4!, whereas in

the event of S1 @gs? the game wQuld have

unexpectedly ended in perpetual check:

SL. �dS+! S2 @g6 '!Wf7+ or S2 @g4

'!Wd1 +.

The trap, of course, was a very naive one,

but there was no other chance. Besides, as

Romanishin admitted after the game, he did

not see what he was being lured into, which

means that some probability, however slight,

of the opponent making a mistake never­

theless existed.

------

Schubert - Dolmatov

European Junior Championship,

Groningen 1 977/78

9

�-----This resource had not been seen by

Christian Schubert in his analysis. Before

the next time control he still had to make six

moves, and he had little time left: some 5-7

minutes (he had had to 'take on' too much

time when the game was adjourned).

10

White sealed his move. The safest way to

draw is 48 g4!, in order to answer 48 . . . .: c2+

with 49 'it>g3, and 48 . . . 'it>f4 with 49 .: ts . . Q 1 �. Where should the king move? I n

Also possible is 48 'it>Q2 with the same idea

replying to the question, tr y to imagine that

- not to allow the king to be pushed back

you are in the same degree of time trouble .

onto the 1 st rank. But Dolmatov and I also as the young German player was.

studied carefully the less good move 48 c6,

Dolmatov's opponent instinctively wanted

which was in fact sealed.

to avoid the mating threats resulting from

An opponent wh o Is tired after a diffi cult the opposition of the kings, but 51 'it>e1 I

game often does not seal th e strongest was the correct decision. After all, 51 . . . .I: g2

move. Therefore you should carefully 52 c;t>t1 n xg3 53 .: ta would have led to an

analyse all possibi lities, no worryi ng immediate draw.

th at, In th e event of th e correct move

51

�c1 ?

l:td&I

being sealed, your analysis will be In

52

c7

l:td71

vain.

If the rook moves, then the c7 pawn is

48

c&?I

l:tc2+

captured with check, and meanwhile Black

49

�e1

�e3

is planning simply to strengthen his position

50

�d1

( . . .e5-e4, . . . 'it>f2 etc.). White has to move

Now 50 ... .: c5 51 c 7 e4 suggests itself, but

his king onto the b-file, but from there it can

after 52 g4! (52 .: ta is also possible)

no longer manage to return for the battle

52 . . . .:c6 53 .: ts .:xc7 54 .:xt6 White with the passed e-pawn.

gains a draw without difficulty.

53

�b2

e4

Things can be made more difficult for the

l:tf8

54

opponent by setting a little trap.

If 54 g4 there follows 54 . . . .I: f7! (or 54 . . .

50

l:td2+1

.: e71); weaker i s 5 4. . . 'it>f4 55 g5!

54

55

56

had already studied rook endings, and he, of

course, would not have fallen into the trap .

.J:l.xc7

.J:l.g7

.J:l.xf6

.J:l.c6?

56

57

58

.J:l.xg3

�f4

l:ld3

l:tc3+

.J:l.c8

White was obliged to try his last chance: 56

@c21 If 56 . . . .J:l.xg3? (56 ... @e21 wins), then

57 .J:I. e61 with a draw, e.g. 57 . . . .J:I. g2+ 58

@ d 1 .J:l.g 1+ 59 @c2 @f3 60 @d21 (not

allowing the advance of the e-pawn; now

the point of 57 l:t e61 is clear), or 59 ... l:t e 1

(intending 6 0 . . . @f21) 6 0 .l: h 6 ! However, all

this is well known in theory, Dolmatov and I

And now I should like to offer a few positions

in which the reader himself has to try and

complicate matters for the opponent, by

setting him a trap.

E 1 -1

E 1 3

Black to move

Black to move

E 1 -2

E 1 ·4

Black to move

Black to move

White resigns.

-

11

13

12

14

20

Prize for the Best Ending

With the years, with the gaining o f experience, the quality of analysis does not deteriorate,

but improves. I know this from my own experience: work on adjourned positions becomes

more sensible and more rational, fewer inaccuracies are committed, and even fewer

superficial, premature judgements of the type 'the rest is obvious'. Lev Polugayevsky

As we have already seen, the analysis of

adjourned positions is not purely a chess

problem, but a problem of chess and

psychology. This is felt especially when

either the position is too complicated for an

exhaustive chess analysis, or else th ere is

simply insufficient time for it. I n such

instances it is im port ant to guess the most

probable course of the coming play, and to

concentrate your analytical effort s h this

direction. After all, a mistake in the 'main

direction' will definitely tell on the result of

the game, whereas an omission in some

side v ariation will not influence anything.

The only thing is: how do you decide which

v ariations are the main ones, and which are

sidelines?

Dolmatov - Machulsky

USSR Young Masters Championship,

Vilnius 1 978

15

21·

Q 1 -7. What move would you have sealed

in Machuls ky's place?

To draw, it is simple st for Black immediately

(otherwise it will no longer be allowed) to

exchange a pair of pawns on the kingside:

46 f&I 4 7 gxf& 'itxf& 48 l:l h1 . Now he

needs to exchange pawns on the q ueenside,

but not immediately: 48 ... b6? 49 l:l h6+

rj/; e7 (49 . . . rj/; g7 50 rj/; e5) 50 rj/; e5 l:lc6 in

v iew of the spectacular breakthrough found

by Ken Neat: 51 c4!! dxc4 (51 ... l:l xc4 52

l:l xe6+ rj/; d7 53 l:l xb6) 52 d5. Correct is

48 l:lc&l 49 .:thB (49 l:l h6+ rj; g7) 49 ... b& ·

•••

•••

50 l:!.f8+ 'ite7 51 l:lb8 bxa5 52 'ite5 a4 53

l:l b7+ 'itd8 followed by . . . a4-a3.

If you are defending an Inferior ending,

try to exchange as many pawns as

possible/ The above plan of defence is fully

in accordance with this principle.

I hav e to admit that Dolmatov and I hardly

looked at 46 .. .f61, considering it to be

unli kely, and concentrated on only one of

the possible sealed moves - 46 . . . l: c6. The

opponent could hav e played . . . f7-f6 a long

time ago, but he had not done so. Consider­

ing (and quite justifiably) the position to be

absolutely drawn, Anatoly Machulsky had

been playing am ost without thinking; he

also sealed his secret mov e fairly quickly.

Without particular necessity, players usually

do not change the pattern of the position,

the pawn structure, just before the adjourn­

ment. Why make a choice at the board

between 46 . . . f6, 46 .. . b6 and 46 . . . b5 (sup­

pose it turns out that a pawn sh ould not be

-------

�

moved at all?), if, by playing 46 . . . J:l c6, one

can retain all or nearly all of these possibili­

ties and take a decision only after home

analysis? This logic is normal and generally

acce pted, and it was very probable that this

was what Black had been guided by.

�

47

�e51

J:lc6?1

It turns out that the position is not so

inoffensiv e. White has two imperceptible,

but weighty a dv antages. First, his king is

closer to the centre. Second, White can

attack the f7 pawn, the base of the

opponenrs pawn chain, whereas it is much

more difficult for Black to approach the

supporting b2 pawn. 48 J:l f 1 is threat ened,

then 49 : f6+ @ g7 SO g6. Bad is 47 ... @ xgS?

48 J:l g 1 + and 49 @ f6 (or 49 J:l g7). Only the

adv ance of the b-pawn can giv e Black

counterplay.

L et us first examine 47 . .. b6. In our analysis

Dolmatov and I found this v ariation:

4 8 J:l f 1 ! bxas 49 J:l f6+ @ xgS (49 . . . @ g7?

SO g6) SO J: xf7 J:l b6 (if SO ... a4, then S1

J:l g7+ and S2 J: e7 is strong) S 1 J:l g7+

@ h4 S2 J:l g 1 ! (S2 J:l g2 a4; S2 J: e7 J:l xb2

S3 : xe6 J:l e2+) S2 . . . J: xb2 S3 @ xe6 J:l bS

(after S3 ... J:l c2 S4 J:l a1 J:l xc3 SS J: xaS

Black loses due to the remoteness of his

king) S4 c41 dxc4 SS dS l: b3 S6 d6 J:l e3 +

S7 @ d71 (only not S7 @ dS? : d3 + S8 @c6

c3 S9 d 7 c2 or S9 J:l c1 @ g4 60 d7 @ f4 61

@ c7 @ e3 ) S7. . .c3 S8 J:l c1 a4 (S8 . . . @ g 4 S9

@ c7 @ f4 60 d7) S9 @ c7 a3 60 d7 : d3 61

d8°fk + J:l xd8 62 @ xd8 a2 63 @ d7 @ g4 64

@ d6 @ f4 6S @ dS and wins.

Later grandmaster Grigory K aidanov dem­

onstrated the correct plan of defen ce,

beginning with S 1 ... @ hS! To us it seemed

less accurate than S1 . . . @ h4, since after S2

J:l g 1 J: xb2 S3 @ xe6 J:l c2 White, apart

from S4 : a1 , can now also win more

simply: S4 J:l g3 ct> h4 SS J:l d3 a4 S6 @ xdS

a3 S7 c4 a2 58 : a3 . Howev er, instead of

S2 ... l1 xb2?, stronger is S2 . . . a41 S3 l:l a1

@ g61 S4 : xa4 @ f7 with a probable draw.

.22

------

The fact that Dolmatov and I overlooked

this defence was annoying, but excusable

from the v iewpoint of a practic al player.

After all, our objectiv e was to find and

analyse the possibilities for White wh ich

promised him the be�t chances of success.

To determine the optimal defence for _the

opponent is also important, of course, but

only to the extent to which it influences our

choice, our decisions. In the given instance

we al l the same did not have anything

better, and the search for a sav ing line for

Black is, so to speak, his problem.

As for Machulsky, in his analysis he was

simply obliged to find a forced draw (one

senses that there is one, and K aidanov 's

v ariation convinc ingly demonstrates it). But

apparently he did not sense the danger that

was threatening him.

47

b5?1

It would hardly hav e been any better to play

this a mov e earlier instead of �- .. l:l c6. To

46 . . . bS White would hav e replied 47 : h 1 ,

and if, for example, 4 7. . . J:l d8, t hen 48

J:l h6+ @ g7 49 @ es l: b8 (49 . .. b4 so cx b4

l:l b8 S1 l:t f6 :t xb4 S2 g6) SO J:l f6 J:l h81?

S 1 @ d6! J:l h2 S2 @ e7! l:X b2 S3 J: xf7+

@ g6 54 J:l f81

48

:n

l:c71

Black has parried the threat of 49 : f6+, on

which he now has 49 . . . � xgS. Completely

bad was 48 ... b4? 49 cxb4 J:l c4 SO bS lh4

(SO . . . axbS S1 J:l a 1) S1 b61 J: xas_ S2 @ d6

J:l bS S3 @ c7 J:l xb2 S4 b7.

49

�d&

:ca

50

51

%tf6+

J:lf311

'it.>g7

49 ... J:l c4 so J:l f6+ @ g7 s 1 @ es b4 S2 g6

fxg6 S3 cxb4 : xb4 S4 : xe6 would hav e

immediately l e d t o a position, which in the

game White would stil l have had to try and

obtain.

Pointless is S 1 @ es : h8!, when S2 g6?? is

not possible because of S2 . . . J:l hS+. The

subtle rook mov e creates the threat of S2

@ d7 (S2 ... J:l c4?? S3 b3). It also has a

-----

�·----If 55 ... J: xb4 there follows 56 J: f6+ @ g7

(56 ... @ xg5? loses to 57 l:t xf7 J: xb2 58

@ xe6 followed by 59 J: f5+ and 60 J: xd5)

57 g6 fxg6 58 J: xe6 J: xb2 59 l:t xa6. For

the moment we will stop here and state with

regre t that it is difficult to say definitely

whether it is a draw or a loss.

The second possibility occurred in the

game.

second aim - to reduce the strength of

. . . b5-b4, which Black is now bound to play.

S1

S2

S3

b41

.l:l. b8

.1:1.bS

cxb4

.l:l.b31

54 b5 was threatened.

S4

�es

Zugzwangl Black has to play his king to g6,

making it easier for the opponent to carry

out n s main plan: J: f3 -f6 and g5-g6.

S4

SS

SS

S6

S7

·�g6

.J:l.f3

.1:1.f6+

bSI

J:b7

<li>xgS

J:xbS

Of course, unattractiv e is 57 ... axb5 58 b4

folowed by 59 l: f1 and a comparativ ely

straightforward win.

16

S8

.l:l.xf 7

J:xas

The v ariation 58 ... .l:l. xb2 59 @ xe6 has

already been assessed as favouring White,

in v iew of the threat of 60 l:t f5+ and 6 1

J: xd5. B u t no w Black is hoping for 5 9 @ xe6

J:t b5 with an obvious draw.

S9

60

·

Q 1 -8. Try making the difficult choice

between S4 l:txb4 and S4 l:tb7.

• • •

•.•

How in such situations does one take a

decision? First of all, in both variations

we find the moves that are forced and

easily calculated. It is possible that in

one of the branches they lead to a clearly

drawn position. Or, on the contrary, it

may transpire that after one of the initial

moves we lose by force, whereupon by

the method of elimination we should

chose the other. It is more complicated if

in both cases the positions arising are

not completely clear - then what is

required is a lengthy and difficult calcu­

lation of variations or an intuitive choice

of one of the possible continuations.

29

.l:l.g7+

.l:l.b711

<li>h6

This elegant resource should have been

found by Machulsky when he took his

decision on mov e 55 (or better still - in the

course of his home analysis!) - then he

would not hav e played 55 . . . J:t b7? The rook

is now crippled (60 ... J:t a4 61 b3). White

wins both of the central pawns, and after

them the game.

.

60 �gs 61 �xe6 �f4 62 b4 J:a4 63

�xdS as 64 b5 �e3 65 J:t a 7 J:txd4+ 66

.•.

�cS

J:tc7

J:tb2

�a 7

J:ta4 67 �b6 J:t h4 68 � xaS �d4 69

�dS 70 b6 �d6 71 J:tc 1 J: h2 72 b7

73 �a6 :a2+ 74 �b6 l:tb2+ 7S

l:t a2+ 76 �b8 l:t h2 n l:ta1 . Black

resigns.

Now it is clear that, good or bad, Black

should hav e gone in for 55 . . . J:t xb4!

56 .l:l. f6+ @ g7 57 g6 fxg6 58 J:t xe6 J:t xb2

59 J:t xa6, and looked for a sav ing line here.

Before the resumption Dolmatov assessed

this position (and also his chances of

winning in general) v ery optimistically on

the basis of the following v ariations:

.

lll ·IM

l 1111-lilmm1 ...

l •acu

!l !Wi�!.t.!Sl£11:1Gftl!Ql

llll

lll

l ll

!!l!ll!

'!l!

ll

lll

llli:iMllM llll

--

�

1) S9 . . . gS 60 J:[ b6 l: a2 61 a6 g4 62 'Ot f4

J: a4 63 'Ot xg4 J: xd4+ 64 'Ot gS! 'Ot f7

6S 'Ot ts 'Ot e7 66 'Ot es l:t a4 67 l: b7+ 'Ot d8

68 a7;

2) S9 . . . l:a2 60 J: a7+ 'Ot h6 61 J: a8 'Ot g7!

62 a6 J: as 63 'Ot e6 J: a1 (63 . . . gs 64 'Ot fS)

64 'Ot xdS gS 6S 'Ot e4 g4 66 dS!

After the game I had the time to check the

rook en din g more carefu lly. It tran spired that

Black can gain a draw in both variations.

In the first - by cutting off the kin g from the

passed g-pawn: 60 . . . J:[ f2! (in stead of

60 . . . l:. a2?) 61 a6 g4 62 a7 ll a2, or

62 'Ot xdS 'Ot f7! (but not 62 . . . g3? 63 ll b3 g2

64 J: g3+ 'Ot f7 65 a7 J: a2 66 ll x g2 l:t xa7

67 J: e2! and wins).

In the second - by playin g 63 . . . ll a2!

(instead of 63 ... l: a1?; 63 . . . l:t a3! is even

simpler) 64 'Ot xdS gS! 65 'Ot e4 (6S 'Ot es g4

66 'Ot b6 l:t b2+ 67 @a7 g3 68 J: e8 g2

69 J: e1 'Ot f7 70 dS J: e2) 6S . . . g4 66 'Ot f4

(66 dS g3) 66 . . . l: a4 67 @ xg4 l:t xd4+

68 @ts l: d6! (a typical and very impor­

tant procedure against a rook's pawn:

the white rook, tied to the defence of the

pawn, cannot move from aS, and the

24

"SM!!BMft

M •Ts

•

king, if it approaches the pawn, will have

no shelter against the horizontal checks)

69 'Ot es J:t b6 70 @ ds J: f6 71 c;tcs J:t ts+

72 'Ot d4 J:t f6! etc.

When he adjourned the game, Machu lsky

was sure that he had an easy draw, and he

did not bother to make a thorough analysis

of the position . A zero in the tou rn amen t

table was a ju st pun ishmen t for his careless

an alysis. Dolmatov's poin t, and also the

prize 'for the best en din g' awarded to him at

the closin g ceremony, were a reward for his

ten acious search for resources in a seem­

in gly equal en din g.

It is useful for a chess player to train

himself into thinking that there is no

sueh thing as an absolutely drawn or an

absolutely hopeless position. He must

learn both in analysis, and at the board,

to seek and find the slightest practical

chances, capable of changing the appar­

ently comp letely determined course of

the game. However, we have already

spoken al.lout this in the precedin g chapter.

A Study Generated by M istake

In establishing a thinking procedure, one should proceed with the

aim of possibly shortening the number and length of variations.

Beniamin Blumenfe ld

I rrational thinking (both in the analysis of an

adjourned positio n, and in calcu lating varia­

tions direcUy at the board) is in itself a

serious mistake. The consequ ence is that

time and effort are spent in vain, leading to

purely chess oversights.

Dolmatov - Baree v

Sochi 1 988

·

17

After 42. . . :Z. d8+ 43 @ e5! a4 44 J:t xb6 l:t aa

passive defence is hopeless: 45 J:t b2? a3

46 J: a2 @ e 7. The only correct continuation

is 45 l:t b7! a3 46 J:t f7+ @ g8 (46 . . . @ eB

47 J:t xg7) 47 l:t f1 a2 48 e7, and with the

black king cu t off from the e-pawn, White's

position is not worse.

The best move is 42 �eSI If now White

harasses the rook - 43 @ c7? J:t a8!

44 @ b7 l:t d B (and if 45 J:t dS there is 45 . . .

@ e7), th en his king gets stuck somewhere

to one side; Black gives up his passed

pawns and decides the game on the

kingside.

The more cu nning 43 J:t d5?! ju stifies itself

in the event of 43 . . . a4 44 @ c7 J:t aa 45

@ b7 J:t as 46 @ xb6 l: xdS 47 exd5 a3 48

@c7 a2 49 d6 a1'ft so d7+ @ e7 51 dB'ft+

@ xe6 52 'ir d6+ @ f7 (52 . . . @ fS 53 'f6° f4+

@ g6 54 'ti' e4+) 53 'ft dS+ with perpetual

check. However, Black has the subtle reply

43 . . . : a8! with the idea bf 44 @ c7 @ e7!

43 l: f51 b51 44 l: f7 (not 44 e7? in view of

44 . . . l: b6+) 44 b 4 Now White has to

choose between 45 l: xg7 and 45 l: e7+. •

A 45 J:xg 7 l: b6+ 46 c;t>e5 b3. Now the

obvious 47 @ f6 is pointless because of

47 . . . @ d8. Take note of this position: it is

very important that the e-pawn is pinned

and is not able to advance either immedi­

ately, or after, say, 48 l: d7+ @ ca 49 l: d1

(49 @ f7 J: xe6 50 @ xe6 b2 51 l: d1 a4)

49 . . . b2 so : b1 a4.

47 l: a7! b2 48 :as+ c;t> e7 49 :Z.a7+ @d8.

After 49 . . . @ f8 50 l: a8+ @ g7? 51 e7 b1'f6°

52 l:t g8+! 'it>h7 53 l: h8+! 'it>xh8 54 eB'ti'+

...

••.

I f Black should hu rry with the pawn advance

41 . . .a4, then 42 e7 @ f7 (42 . . .a3 43 l:t xb6)

43 @ d6 g6! 44 J:t b2 followed by 45 J:t f2+ is

unpleasant. So there was no doubt abou t

his sealed move.

�fB

41

How shou l d White reply? Of course,

42 @ d6, renewing the threat of 43 e7+.

Q 1 -9. E valuate 42 J:td8+.

•••

.

-------

�

'iti> g7 SS ._ d7+! the black king camot avoid

perpetual check. This means that it m ust

head to the other side.

50 l:. a8+ rt;c7 51 e7 b1._ 52 e8W'.

18

------

placing the rook in front of them - is

doomed to failure: 47 l:. f1 b3 48 e7 a4 49

l:. b 1 l: a8 SO 'iti> d7 a3 ! S1 l:. xb3 a2 S2 It a3

l:X a3 S3 e8 '5' + <b h7. The white pawn has

queened first, but on the next move (or after

the preliminary S4 . . . l:. a7+) a black queen

will also appear on the board.

Let us try to bring the rook behind the black

pawns - 47 .J:[f5, intend ing 48 e7 followed

by the diverting move .J:[ bS.

19

Black begins, checks, and i n all probability,

soon gives mate. It is not worth continuing

the analysis, if only out of sympathy f or the

white king, especially as in reserve there is

another unstudied continuation.

(I should ment ion in parentheses that when

later, i n Moscow, Dolmatov showed me his

g ame with Bareev, we checked this position

and, strangely enough, did not find a mate.

Even so, Sergey was correct to terminate

the analysis here. First he had to look for a

more reliable way to draw , and only if things

were completely hopeless, again return

here.)

B. 45 l:.e7+. I should mention, incidentally,

that Black could not have avoided this

check by transposing moves - 44 . . . l:t b6+

45 @ es b4 - in view of 46 l:. a7! Checks by

the rook are threatened; 46 . . . l:. b8 47 l:t xg7

l:. bS+ 48 <b f6 will not do, as the rook is no

longer pinning the e-pawn. This means that

all the same Black has to play 46 . . . l:t bS+!

47 <b d6 l:. b8.

45. .. <bfB 46 l:.f7+ @g8. Now passive

defence - the attempt to halt the pawns by

26

Q 1-10. Can White save himself here?

As in a good study, here at f irst sight it is not

clear what, strictly speaking, the problem is.

After all, if 47. . . b3 there follows 48 e7 a4

(48 . . . b2 49 .J:[ bS; 48 . . . @ h7 49 l:. f8) 49

l:. bS l: a8 SO l:. a5 . Surely the opponent will

not allow the white pawn to queen with

check! After all, before promoti ng, the black

pawns still have to make several lengthy

steps. But let us nevertheless check this!

so . . . l:t xas S1 e8 't!I + 'iti> h7. It turns out that

al is not so simple. It is pointless attacking

the rook -S2 't!l d8 l:t a6+, and 52 't!l b8

loses to 52 . . . a3 S3 't!l xb3 a2 S4 es l:t a6+

and SS . . . a 1 't!I . Even so we find the correct

plan: S2 't!l c6(c8)! b2 (S2 . . .a3 S3 eS) S3

't!l c2! a3 54 es+, and this fascinating battle

ends in perpetual check.

It appears that everything is alright!

However, this last variation, in which the

rook and pawns nearly overcame the white

queen, put Dolmatov on his guard. And he

found the true solution of the study - he

realised that Black could after all win. Let us

return to the last diagram. It turns out that,

strangely enough, it is the other, less

advanced pawn, that Black should be

aiming to queen!

47 a411 48 e7 a3 49 l: bS. I n the event of

49 : as b3 so l ha3 both so . . b2 s1 : b3

: xb3 and SO . . . @ f7 are decisive.

49 : aa so : as. No better is so ll xb4

@ f7 (of course, not so . . . a2? S1 : a4) S1 es

(S1 l2 b 1 is met by the same reply)

S 1 . . . @ e8! S2 l2 f4 l2 a6+.

SO ... ! baSI S1 eB� + @ h7. A paradoxical

situation: here the queen is completely

powerless.

•.•

.

•.•

S2 �c& a2 S3 es l2 a7 1 S4 �c2+ g&.

out taking the variations to the end, and

checked how obligatory they were, and

whether there were not some other

possibilities.

We should not regret that this was how he

acted - then we would not have seen a

pretty study. But Dolmatov had cause to

regret - there was no time left for him to

analyse the strongest continuation.

42

:b1 1

bS

After making this move, Evgeny Bareev

ottered a draw, and Dolmatov accepted. He

simply did not have tine to readjust, and

realise that now it was not him, but his

opponent who was faced with achieving a

draw. By playing 43 l:t f1 +, he should have

set Bareev a problem, which I now invite the

readers to solve.

20

Surely the adjourned position wasn't lost? !

It couldn't be! Why in general should White

stand worse with his active king and

menacing pawn at e6? After thinking in this

way, Dolmatov took a fresh look at the

position and finally realised that the very

first, seemingly so natural move 42 @ d6?

was a mistake.

Of course, Sergey committed a bad meth­

odological mistake. He should have Imme­

diately determined all the candidate

moves. And If his attention was gripped

by one of them, the most natural (this

happens very often), then much earlier,

after problems arose with 42 ..P d6?, he

should have stopped the analysis with-

27

E 1 -S. Where should the king move to?

.llll'""· �"'ml.litiaaid!illlillll'llfii'ii;.1'W�iililili!Timrrr:mmvmili:ilrm-•••

�

•••••-•-••••-

I C hoose a Pla n that is not the Strongest!

Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here ?

That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.

Lewis Carroll

Zakharian - Dvoretsky

qu ickly discovered that the natural move

41 . . . axb5 was not obligatory. Serious con­

sideration should be given to 41 . . . e3!?, the

aim �f which is not to allow the white rook

on to the 1 st rank and for Black himself to

seize this important lin e .

USSR Spartakiad, Riga 1 975

21

Q 1 -1 1 . How should Black reply to 42

ll xa& ?

I thought that 42 ll xa6 lost by force to

42. . . •xf2+ 43 'tfxf2 ll d1 + 44 •11 e2. In

fact this is merely a cunn in g false trail White has a pretty defence (foun d by

g randmaster S.Kin d ermann ): 45 • e1 ! ! The

rook en din g arisin g after 45 . . . ll xe 1 + 46

@f2 ll b1 47 @ xe2 l:t xb2+ 48 �e3 l:t xb5

49 ll xe6 is drawish, e.g. 49 . . . l:t c5 (other­

wise 50 �e4) 50 @ d3 @g8 (50 . . . h5 51 c4

in tendin g l:t b6-b5) 51 l:t e7 @ ta 52 l: b7

l:t c6 5 3 c4 l:t g6 54 c5 @ea 55 @e4, and

White's position is not worse.

42 . . . J:[ d1 + 43 •xd1 • xt2+ 44 @ h2 e2

does not work in view of 45 • d3+. Also,

nothin g is achieved by 42 ... exf2+ 43 @ f1

: dB (with the threat of 44 ... J:[ f8; if 43. . . J:[ d7

44 J:[ a4!) 44 J:[ a 1 ! (but n ot 44 J:[ a4 @ g8!).

Now 45 •xt2 is threatened, an d if 44... J:f8

there follows 45 • f3.

After 42 ... • b 1 + ! 43 @ h2 the lin e 43 ... exf2

44 •xf2 l:t d 1 45 l:t xe6 l:t h 1 + 46 @ g3

suggests itself, bu t if 46 ... • e4 there is the

pretty defence 47 • d4! However, b y con­

tinuing 46 . . . J:[ h5!, Black retain s a very

dangerous attack.

43 . . . l:t d1 ! is apparen tly stron ger, e.g.: 44

'il xe3 l:t h1 + 45 �g3 • gs+ 46 @f3 : h4!

47 • xe5 (47 g3 • g4+) 47 . . . • d3+, or 44

White's sealed move is obvious.

41

axb5

The followin g variation looks forced: 41 . . .

axb5 4 2 ll a 1 ! (with the threats o f 4 3 • xb5

or 43 ll e 1 ) 42 . . . ll d3! 43 ll e1 e3 44 fxe3

e4. Black has retained his extra pawn, and

subsequ ently he will attack by advancin g

h i s kin gside pawns. Unfortunately, in the

process the position of his kin g will become

less secure an d the opponent will gain

defin ite tactical coun ter-chances. Even so,

o bjectively Black has every reason to hope

for su ccess.

We already know that the first moves of the

an alysis should be checked especial ly

carefu lly. Do we (or the oppon ent) have an y

other, more promisin g poss ibilities? After

lookin g at the position from this viewpoint, I

2e

-------

�

fxe3 l:l. h 1 + 45 'it> g3 ... e4!? 46 ... g4 (46

'it>f2 ... h4+; 46 l:l. xe6 h5!) 46 . . . ...xe3+ 47

...f3 ... e1 + 48 'tff2 ...e4, and Black wins.

White must choose between 42 fxe3 and 42

... xe3 .

1 ) 42 fxe3 ... b 1 + 43 'it> h2 l:I. d 1 . Now the

counterattack 44 ... g4? does not work in

view of 44 . . . l:l. h 1 + 45 'it> g3 ... e1 + 46 \ttf3

l:l. f1 + 47 'it>e4 l:l. f4+!

Does Black have any serious threats? Let

us check 44 b6 l:I. h 1 + 45 'it> g3 . Now

45 . . . 'tfe4? is incorrect: 46 ... g4! ... xe3 + 47

...f3 ... e 1 + 48 'tff2 .., e4 49 'tff6! and Black

has to give perpetual check. He mu st

deprive the qu een of the g4 squ are, by

playing 45 . . . h S! Here are some possible

variations:

46 b7 ... e4 47 'it> f2 ... h4+ 48 g3 l:l. h2+ (or

48 . . . ... h2+ 49 'it> f3 e4+ 50 'it> xe4 'ir xe2 51

b8 'ir 'if g2+ with a rapid mate) 49 'it> f1

... h3 +;

46 l:t d7 ...g6+ 47 r;i;> f2 e4! ;

4 6 e 4 h4+ (46 . . . 'tf c 1 i s also strong, e . g . 47

l:l. f7 'it> g6! 48 b7 h4+ 49 'it> f2 ... g1 + 50 'it> f3

.l:. h3 +!) 47 'it> g4 (47 'it> f2 'if g 1 + 48 �f3

l:t h3 +! 49 'it> g4 l:I. g3 + 50 'it> h5 l:I. xg2)

47 . . . l:t e 1 48 ...f3 l:l. xe4+ 49 'it>h5 (49 'it> g5

'tf c1 +) 49 ... l:l. f4 .

T h e best defence is 44 'it> g3 ! Black does

not have time for 44 . . . axbS in view of 45

... g4. The attempt to attack e3 does not

work: 44. . . ... c1 45 b6 e4 46 b7 l:l. e 1 47

b8 'ir IZ. xe2 48 l:t xg7+! 'it> xg7 49 ... es+.

There only remains 44 . . . l:t h 1! 45 l:l. d7!

axb5 4 6 ... d3 + ... xd3 47 l:t xd3 . However,

after 47 . . . 'it> g6! it is not easy for White to

defend, since 48 l:l. d6 is strongly met by

48 . . . l:l. b1 !

2) 42 ...xe3 l:l. d 1 + 43 � h2. Now nothing is

given by either 43 ... 'ir b1 ? 44 'tfxe5 or

43 . . . l:t d3 ? 44 ... e2 axb5 45 l:l. f7! This

means that 43 . . . axb5 mu st be played.

White can take play into a rook ending in

which, despite being a pawn down, he can

hope for a draw: 44 ... g3 ! ... h5+ 45 'irh3

...xh3 + (weaker is 45 . . . ...g6 46 : b7 l:I. d2

-------

47 l: xb5 l:l. xf2 48 l:l. xe5 :t xb2 4 9 c4!, bu t

not 49 .l:. xe6? l:l. xg2+! 50 W xg2 ... xe6 with

winning chances for Black in the qu een

ending) 46 'it> xh3 l:l. d2 47 l: e7 .l:. xf2 48

l: xe6 l:t xb2 49 l:t xe5 'it> g6 .

Analysis showed that if, being afraid of the

rook ending a pawn down, White does not

hu rry to exchange queens, he encounters

mu ch more difficult problems. Thus if 44 f3 ?

Black has the very strong reply 44 . . . l:t b 1! ,

e.g. 45 b 4 ... h5+ 4 6 'it> g3 W g6+ 47 'it> h2

l:t b2 .

Q 1 -1 2. How should Black reply to 44

l:t b7 ?

22

·

:2 9

The refutation of this move was found by

Yuri Balashov (the game was played in a

team competition, and I showed my prelimi­

nary analysis to my team colleagu es).

Ju mping ahead, I should mention that on

the resu mption it was this variation that

occu rred.

After completing my study of the adjourned

position, I faced a dilemma: which path to

chose, 41 . . . axbS or 41 . . . e3 ? It was clear

that the first continuation was objectively

stronger, bu t it was not this one to which

preference was given (as the reader will

have guessed . long ago, of course - from

the chapter heading). Why?

-------

�

First, 41 . . . e3 could have been missed by

my opponent i1 his analysis, and we already

known how important it is to use the effect of

surprise.

Second , after 4 1 . . . axbS the conv ersion of

the advantage was still very difficult, and

much time and effort would hav e had to be

spent. Whereas 41 . . . e3 had been analysed

in detail, and the slightest inaccuracy by my

opponent would enable him to be defeated

easily and quickly - by my home analysis.

A player who was more principled and

confident in his.powers would possibly have

taken a different decision. It is pointless

arguing who is right here - there is no

simple answer. The choice depends on

your style of play and chess tastes, and

also on attendant circumstances con­

nected with your tournament position,

the personality of your opponent, your

reserve of energy and so on. It Is very

Important to learn to weigh up objec­

tively or evaluate Intuitively the whole

sum of competitive and psychological

factors. Then you will act In the way that

Is the most uncomfortable for your

opponent and the safest for yourself,

and you will achieve results that on a

superficial glance may even seem not

attogether deserved.

And what happened on the resumption?

41

42

e31?

'ifxe3

Zakharian thought for twenty minutes on

this mov e. This means that Black, as he had

hoped, had immediately managed to per­

plex his opponent.

42

43

44

45

�h2

:b7?

'ife2

l:td1 +

axb5

l:td31

If 4S g4!? Black replies 4S . . . 'fi' g6 46 'ft' e2

(46 '@' xeS 'fi' xg4) 46 ... e4 47 l:t xbS l:t f3 48

l:t es 'fi' xg4 (48. .. l:t f4 49 @ g3 ) 49 'fi' xe4+

'fi' xe4 SO l be4 l:t xf2+ S1 @g3 l:t xb2 S2

l:t xe6 l:t c2 S3 l:t c6 hS! followed by . . . g7-

..-----

g6 and . . . @h6 with a won rook ending.

45

'iff4+

4S . . . e4 is also good, e.g. 46 @ g 1 'fi' dS! 47

l:t f7 l:t d1+ 48 @ h2 l:t d2 49 'fi' g4 'fi es+.

46

47

48

g3

gxf4

l:txb5

l:td21

l:txe2

exf41

A simple check shows that the black pawns

adv ance towards the queening square

much more q u ickly than the opponent's.

49

50

51

52

53

54

g5

l:te1

�g6

es

e4+

f3+

�g2

�f3

b4

l:tb8

b5

�g2

This whole series of moves by Black was

planned at home. The outcome is now

clear.

�h2

:m

ss

55 ... e3 S6 @ g3 g4! is also strong.

56

�g3

l:tg1 +

57

�h2

l:tg2+

�h5

58

�h3

White resigns.

Zald

-

Yusupov

Qualifying Tou rnament for the World

Junior Championship, Leningrad 1 977

23

------

42

� ------

�8

24

The sealed move. White's position is diffi­

cult: his kingside pawns are broken, and

Black has the advantage of the two bishops

(in an open position this is indeed a serious

advantage). However, as was shown by the

brief (the game was resumed that same

evening) joint analysis by Artur and myself,

against accurate defence if is not easy for

Black to convert his advantage - there are

too few pawns remaining on the board.

43

b41

Completely correct! When defending an

inferior ending, one should aim for pawn

exchanges. Now Black has to make a

difficult choice between 43 . . . '3;e7 and

43 . . . axb4.

After 43 . . . @ e 7 44 bxaS bxaS 45 ltl cs i. dS

46 i. d31 there is no clear way of further

strengthening Black's position. 46 . . . i.c3 47

ltle4 does not work. If 46 . . . i. b2, then 47

i.e4 (47 . . . @ d6? 48 ltl b7+). n the event of

46 . . . � d6 47 ltl e4+ @ es the ending with

like-colour bishops after 48 ltlxf6?1 �xf6 is

probably won in view of the weakness of the

white pawns. However, by playing 48 tli d21

(with the threat of 49 tli c4+), White drives

back the enemy pieces. It is clear that in the

43 . . . @ e7 variation Black must gear himself

up for a lengthy manoeuvring battle, and

initially without a clear plan.

A quite different situation arises after the

exchange of pawns on b4.

43

44

tlixb4

see next ciagam

axb4

�e7

Q 1 -1 3. How should White continue?

In the event of any 'normal' move, 4S @ f2 .

for example, after 4S . . . � d6 the situation is

much more favourable for Black than in the

variations given above. If this position is

assessed as lost for White (and this

assessment is correct), one immediately

has a strong desire to try 45 a51 bxas 46

/t)c6+. That is what should be played, if, of

course, a calculation of the variations does

not show a forced win for Black. Let us

check!

46... � d6. The ending with opposite-colour

bishops results in a straightforward draw:

46 . . . .b c6 47 i.xc6 i.a1 48 @ f2 � d6 49

i.eS f6 so @e2 @ cs s1 @ d3, or 47 . . . @ d6

·

48 i. e8 @ cs 49 � f2 @ b4 so i. xf7 a4 S1

i.xe6 a3 S2 @ f3 @ c3 S3 @ e4 @ b2 S4

@ ts i. d8 SS e4 a2 S6 i. xa2 @ xa2 S7 es

@b3 S8 @e61 @ c4 S9 @d7 @ dSI 60 e6

i.f6 61 e7 i.xe7 62 @ xe7 @ e41

47 ltlxa5 .� d5. White has exchanged

another pair of pawns, but his knight is in

danger. 48 tlic4+? @ cs is not possible, of

course, and also bad is 48 i.c4? i.c31 49

i. xdS @ xdS SO ltl b3 @ c4 S1 ltl c1 i. d2 S2

ltle2 i.xe3+.

48 Jl.d31 �cs 49 � f21 The hasty 49 e4? is

incorrect: 49 . . . i. a8 so � b3+ @ b4 S1 tli c1

@ c3 with an easy win.

Now, however, in reply to any natural move

the counterblow e3-e4! saves White. For

example: 49 . . . @b4 50 e4! i.aa (50 . . . i.a2

51 e5!) 51 lbc4, or 49 . . . i.c3 50 e4! i.a8 51

'Li b3+! Wb4 52 tllc1 i.d4+ 53 @ e2 @ c3

54 tlla 2+ @b3 55 tll c 1 + @ b2 56 W d2, or

49 . . . i.da 50 e4! i.aa 51 tll c4 (51 'Li b3+