Thematic Analysis Guide for Learning and Teaching Research

advertisement

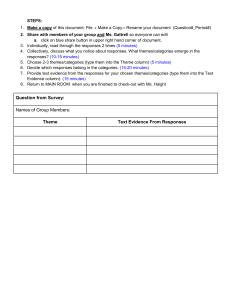

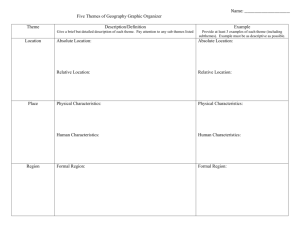

AISHE-J Volume , Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 3351 Doing a Thematic Analysis: A Practical, Step-by-Step Guide for Learning and Teaching Scholars. * Moira Maguire & Brid Delahunt Dundalk Institute of Technology. Abstract Data analysis is central to credible qualitative research. Indeed the qualitative researcher is often described as the research instrument insofar as his or her ability to understand, describe and interpret experiences and perceptions is key to uncovering meaning in particular circumstances and contexts. While much has been written about qualitative analysis from a theoretical perspective we noticed that often novice, and even more experienced researchers, grapple with the ‘how’ of qualitative analysis. Here we draw on Braun and Clarke’s (2006) framework and apply it in a systematic manner to describe and explain the process of analysis within the context of learning and teaching research. We illustrate the process using a worked example based on (with permission) a short extract from a focus group interview, conducted with undergraduate students. Key words: Thematic analysis, qualitative methods. Acknowledgements. We gratefully acknowledge the support of National Digital Learning Repository (NDLR) local funding at DkIT in the initial development of this work. *URL: http://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335 AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 3352 1. Background. Qualitative methods are widely used in learning and teaching research and scholarship (Divan, Ludwig, Matthews, Motley & Tomlienovic-Berube, 2017). While the epistemologies and theoretical assumptions can be unfamiliar and sometimes challenging to those from, for example, science and engineering backgrounds (Rowland & Myatt, 2014), there is wide appreciation of the value of these methods (e.g. Rosenthal, 2016). There are many, often excellent, texts and resources on qualitative approaches, however these tend to focus on assumptions, design and data collection rather than the analysis process per se. More and more it is recognised that clear guidance is needed on the practical aspects of how to do qualitative analysis (Clarke & Braun, 2013). As Nowell, Norris, White and Moules (2017) explain, the lack of focus on rigorous and relevant thematic analysis has implications in terms of the credibility of the research process. This article offers a practical guide to doing a thematic analysis using a worked example drawn from learning and teaching research. It is based on a resource we developed to meet the needs of our own students and we have used it successfully for a number of years. It was initially developed with local funding from[Irish] National Digital Learning Repository (NDLR) and then shared via the NDLR until this closed in 2014. In response to subsequent requests for access to it we decided to revise and develop this as an article focused more specifically on the learning and teaching context. Following Clarke & Braun’s (2013) recommendations, we use relevant primary data, include a worked example and refer readers to examples of good practice. 2. Thematic Analysis. Thematic analysis is the process of identifying patterns or themes within qualitative data. Braun & Clarke (2006) suggest that it is the first qualitative method that should be learned as ‘..it provides core skills that will be useful for conducting many other kinds of analysis’ (p.78). A further advantage, particularly from the perspective of learning and teaching, is that it is a method rather than a methodology (Braun & Clarke 2006; Clarke & Braun, 2013). This means that, unlike many qualitative methodologies, it is not tied to a particular epistemological or theoretical perspective. This makes it a very flexible method, a considerable advantage given the diversity of work in learning and teaching. AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 3353 There are many different ways to approach thematic analysis (e.g. Alhojailan, 2012; Boyatzis,1998; Javadi & Zarea, 2016). However, this variety means there is also some confusion about the nature of thematic analysis, including how it is distinct from a qualitative content analysis1 (Vaismoradi, Turunen & Bonda, 2013). In this example, we follow Braun & Clarke’s (2006) 6-step framework. This is arguably the most influential approach, in the social sciences at least, probably because it offers such a clear and usable framework for doing thematic analysis. The goal of a thematic analysis is to identify themes, i.e. patterns in the data that are important or interesting, and use these themes to address the research or say something about an issue. This is much more than simply summarising the data; a good thematic analysis interprets and makes sense of it. A common pitfall is to use the main interview questions as the themes (Clarke & Braun, 2013). Typically, this reflects the fact that the data have been summarised and organised, rather than analysed. Braun & Clarke (2006) distinguish between two levels of themes: semantic and latent. Semantic themes ‘…within the explicit or surface meanings of the data and the analyst is not looking for anything beyond what a participant has said or what has been written.’ (p.84). The analysis in this worked example identifies themes at the semantic level and is representative of much learning and teaching work. We hope you can see that analysis moves beyond describing what is said to focus on interpreting and explaining it. In contrast, the latent level looks beyond what has been said and ‘…starts to identify or examine the underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualisations – and ideologies - that are theorised as shaping or informing the semantic content of the data’ (p.84). 3. The Research Question And The Data. The data used in this example is an extract from one of a series of 8 focus groups involving 40 undergraduate student volunteers. The full study involved 8 focus-groups lasting about 40 minutes. These were then transcribed verbatim. The research explored the ways in which students make sense of and use feedback. Discussions focused on what students thought about the feedback they had received over the course of their studies: how they understood it; the extent to which they engaged with it and if and how they used it. The study was ethically approved by the Dundalk Institute of Technology School of Health and Science Ethics Committee. All of those who participated in the focus group from which the extract is taken 1 See O’Cathain & Thomas (2004) for a useful guide to using content analysis on responses to openended survey questions. AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 3354 also gave permission for the transcript extract to be used in this way. The original research questions were realist ones – we were interested in students’ own accounts of their experiences and points of view. This of course determined the interview questions and management as well the analysis. Braun & Clarke (2006) distinguish between a top-down or theoretical thematic analysis, that is driven by the specific research question(s) and/or the analyst’s focus, and a bottom-up or inductive one that is more driven by the data itself. Our analysis was driven by the research question and was more top-down than bottom up. The worked example given is based on an extract (approx. 15 mins) from a single focus group interview. Obviously this is a very limited data corpus so the analysis shown here is necessarily quite basic and limited. Where appropriate we do make reference to our full analysis however our aim was to create a clear and straightforward example that can be used as an accessible guide to analysing qualitative data. 3.1 Getting started. The extract: This is taken from a real focus-group (group-interview) that was conducted with students as part of a study that explored student perspectives on academic feedback. The extract covers about 15 minutes of the interview and is available in Appendix 1. Research question: For the purposes of this exercise we will be working with a very broad, straightforward research question: What are students’ perceptions of feedback? 3.2 Doing the analysis. Braun & Clarke (2006) provide a six-phase guide which is a very useful framework for conducting this kind of analysis (see Table 1). We recommend that you read this paper in conjunction with our worked example. In our short example we move from one step to the next, however, the phases are not necessarily linear. You may move forward and back between them, perhaps many times, particularly if dealing with a lot of complex data. Step 1: Become familiar with the data, Step 4: Review themes, Step 2: Generate initial codes, Step 5: Define themes, Step 3: Search for themes, Step 6: Write-up. Table 1: Braun & Clarke’s six-phase framework for doing a thematic analysis AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 3355 3.3 Step 1: Become familiar with the data. The first step in any qualitative analysis is reading, and re-reading the transcripts. The interview extract that forms this example can be found in Appendix 1. You should be very familiar with your entire body of data or data corpus (i.e. all the interviews and any other data you may be using) before you go any further. At this stage, it is useful to make notes and jot down early impressions. Below are some early, rough notes made on the extract: The students do seem to think that feedback is important but don’t always find it useful. There’s a sense that the whole assessment process, including feedback, can be seen as threatening and is not always understood. The students are very clear that they want very specific feedback that tells them how to improve in a personalised way. They want to be able to discuss their work on a one-to-one basis with lecturers, as this is more personal and also private. The emotional impact of feedback is important. 3.4 Step 2: Generate initial codes. In this phase we start to organise our data in a meaningful and systematic way. Coding reduces lots of data into small chunks of meaning. There are different ways to code and the method will be determined by your perspective and research questions. We were concerned with addressing specific research questions and analysed the data with this in mind – so this was a theoretical thematic analysis rather than an inductive one. Given this, we coded each segment of data that was relevant to or captured something interesting about our research question. We did not code every piece of text. However, if we had been doing a more inductive analysis we might have used line-by-line coding to code every single line. We used open coding; that means we did not have pre-set codes, but developed and modified the codes as we worked through the coding process. We had initial ideas about codes when we finished Step 1. For example, wanting to discuss feedback on a one-to one basis with tutors was an issue that kept coming up (in all the interviews, not just this extract) and was very relevant to our research question. We discussed these and developed some preliminary ideas about codes. Then each of us set about coding a transcript separately. We worked through each transcript coding every segment of text that seemed to be relevant to or specifically address our research question. When we finished we compared our codes, discussed them and modified them before moving on to the rest of the transcripts. As we worked through them we generated new codes and sometimes modified AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 3356 existing ones. We did this by hand initially, working through hardcopies of the transcripts with pens and highlighters. Qualitative data analytic software (e.g. ATLAS, Nvivo etc.), if you have access to it, can be very useful, particularly with large data sets. Other tools can be effective also; for example, Bree & Gallagher (2016) explain how to use Microsoft Excel to code and help identify themes. While it is very useful to have two (or more) people working on the coding it is not essential. In Appendix 2 you will find the extract with our codes in the margins. 3.5 Step 3: Search for themes. As defined earlier, a theme is a pattern that captures something significant or interesting about the data and/or research question. As Braun & Clarke (2006) explain, there are no hard and fast rules about what makes a theme. A theme is characterised by its significance. If you have a very small data set (e.g. one short focus-group) there may be considerable overlap between the coding stage and this stage of identifying preliminary themes. In this case we examined the codes and some of them clearly fitted together into a theme. For example, we had several codes that related to perceptions of good practice and what students wanted from feedback. We collated these into an initial theme called The purpose of feedback. At the end of this step the codes had been organised into broader themes that seemed to say something specific about this research question. Our themes were predominately descriptive, i.e. they described patterns in the data relevant to the research question. Table 2 shows all the preliminary themes that are identified in Extract 1, along with the codes that are associated with them. Most codes are associated with one theme although some, are associated with more than one (these are highlighted in Table 2). In this example, all of the codes fit into one or more themes but this is not always the case and you might use a ‘miscellaneous’ theme to manage these codes at this point. AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) Theme : The purpose of Theme: Lecturers. feedback. Codes Codes Ask some Ls, Help to learn what you’re doing Some Ls more approachable, wrong, 3357 Theme: Reasons for using feedback (or not). Codes To improve grade, Limited feedback, Didn’t understand fdbk, U n a b l e t o j u d g e w h e t h e r Some Ls give better advice, question has been answered, Reluctance to admit difficulties to L,Fear Fdbk focused on grade , of unspecified disadvantage, Use to improve grade, U n a b l e t o j u d g e w h e t h e r Unlikely to approach L to discuss fdbk, Distinguish purpose and use, question interpreted Lecturer variability in framing fdbk, Unlikely to approach L to discuss fdbk, properly, Unlikely to make a repeated attempt, Improving structure improves grade, Distinguish purpose and use, Have discussed with tutor, Can’t separate grade and learning, Improving grade, Example: Wrong frame of mind New priorities take precedence = forget about Improving structure feedback Theme: How feedback is used T h e m e : E m o t i o n a l r e s p o n s e t o Theme: What students want from feedback. (or not). feedback. Codes Codes Codes Usable fdbk explains grade and how to improve, Read fdbk, Like to get fdbk, Want fdbk to explain grade, Usually read fdbk, Don’t want to get fdbk if haven’t done Example- uninformative fdbk, well, Refer to fdbk if doing Very specific guidance wanted, Reluctance to hear criticism, same subject, Reluctance to hear criticism (even if More fdbk wanted, Not sure fdbk is used, constructive), Want dialogue with L, Used fdbk to improve Fear of possible criticism, Dialogue means more, referencing, Experience: unrealistic fear of criticism, Dialogue more personalised/ individual, Example: using fdbk to Fdbk taken personally initially, Dialogue more time consuming but better, improve referencing, Fdbk has an emotional impact, Want dedicated class for grades and fdbk, Refer back to example Difficult for L to predict impact, Compulsory fdbk class, that ‘went right’, Student variability in response to fdbk, Structured option to get fdbk, Forget about fdbk until Want fdbk in L’s office as emotional Fdbk should be constructive, response difficult to manage in public, next assignment, Fdbk should be about the work and not the Wording doesn’t make much difference, Fdbk applicable to similar person, Lecturer variability in framing fdbk, assignments, Experience – fdbk is about the work, Negative fdbk can be constructive, Fdbk on referencing Difficulties judging own work, Negative fdbk can be framed in a widely applicable, Want fdbk to explain what went right, supportive way. Experience: fdbk focused Fdbk should focus on understanding, on referencing, Improving understanding improves grade. Generic fdbk widely Want fdbk in Ls office as emotional response difficult to manage in public. applicable. Table 2: Preliminary themes (* fdbk = feedback; L = lecturers) AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 3358 3.6 Step 4: Review themes. During this phase we review, modify and develop the preliminary themes that we identified in Step 3. Do they make sense? At this point it is useful to gather together all the data that is relevant to each theme. You can easily do this using the ‘cut and paste’ function in any word processing package, by taking a scissors to your transcripts or using something like Microsoft Excel (see Bree & Gallagher, 2016). Again, access to qualitative data analysis software can make this process much quicker and easier, but it is not essential. Appendix 3 shows how the data associated with each theme was identified in our worked example. The data associated with each theme is colour-coded. We read the data associated with each theme and considered whether the data really did support it. The next step is to think about whether the themes work in the context of the entire data set. In this example, the data set is one extract but usually you will have more than this and will have to consider how the themes work both within a single interview and across all the interviews. Themes should be coherent and they should be distinct from each other. Things to think about include: • Do the themes make sense? • Does the data support the themes? • Am I trying to fit too much into a theme? • If themes overlap, are they really separate themes? • Are there themes within themes (subthemes)? • Are there other themes within the data? For example, we felt that the preliminary theme, Purpose of Feedback ,did not really work as a theme in this example. There is not much data to support it and it overlaps with Reasons for using feedback(or not) considerably. Some of the codes included here (‘Unable to judge whether question has been answered/interpreted properly’) seem to relate to a separate issue of student understanding of academic expectations and assessment criteria. We felt that the Lecturers theme did not really work. This related to perceptions of lecturers and interactions with them and we felt that it captured an aspect of the academic environment. We created a new theme Academic Environment that had two subthemes: Understanding AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 3359 Academic Expectations and Perceptions of Lecturers. To us, this seemed to better capture what our participants were saying in this extract. See if you agree. The themes, Reasons for using feedback (or not), and How is feedback used (or not) ,did not seem to be distinct enough (on the basis of the limited data here) to be considered two separate themes. Rather we felt they reflected different aspects of using feedback. We combined these into a new theme Use of feedback, with two subthemes, Why? and How? Again, see what you think. When we reviewed the theme Emotional Response to Feedback we felt that there was at least 1 distinct sub-theme within this. Many of the codes related to perceptions of feedback as a potential threat, particularly to self-esteem and we felt that this did capture something important about the data. It is interesting that while the students’ own experiences were quite positive the perception of feedback as potentially threatening remained. So, to summarise, we made a number of changes at this stage: • We eliminated the Purpose of Feedback theme, • We created a new theme Academic Environment that had two subthemes: Understanding Academic Expectations and Perceptions of Lecturers, • We collapsed Purpose of Feedback, Why feedback is (not)used and How feedback is (not) used into a new theme, Use of feedback, • We identified Feedback as potentially threatening as a subtheme within the broader theme Emotional Response to feedback. These changes are shown in Table 3 below. It is also important to look at the themes with respect to the entire data set. As we are just using a single extract for illustration we have not considered this here, but see Braun & Clarke (2006, p 91-92) for further detail. Depending on your research question, you might also be interested in the prevalence of themes, i.e. how often they occur. Braun & Clarke (2006) discuss different ways in which this can be addressed (p.82-82). AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) T h e m e : A c a d e m i c Theme: Use of feedback. Context. Subtheme: Reasons for using Subtheme: Academic fdbk (or not). expectations. Help to learn what you’re doing Unable to judge whether wrong, question has been Improving grade Improving answered, structure, Unable to judge whether q u e s t i o n i n t e r p r e t e d To improve grade, properly, Limited feedback, Difficulties judging own Didn’t understand fdbk, work. Fdbk focused on grade, Subtheme: Perceptions of lecturers , Use to improve grade, Ask some Ls, Distinguish purpose and use, Some Ls approachable, T h e m e : E m o t i o n a l Theme: What students want response to feedback. from feedback. Like to get fdbk, Usable fdbk explains grade and how to improve, Difficult for L to predict impact, Example- uninformative fdbk, Very specific guidance wanted, Student variability in response to fdbk, More fdbk wanted, S u b t h e m e : F e e d b a c k Want dialogue with L, potentially threatening. Dialogue means more, Don’t want to get fdbk if Dialogue more personalised/ haven’t done well, individual, Reluctance to hear criticism, Dialogue more time consuming Reluctance to hear criticism but better, (even if constructive), Want dedicated class for Fear of possible criticism, grades and fdbk, m o r e Improving structure improves grade, Experience: fear of potential S o m e L s g i v e b e t t e r C a n ’ t s e p a r a t e g r a d e a n d criticism, advice, learning, Fdbk taken personally R e l u c t a n c e t o a d m i t New priorities take precedence = initially, difficulties to L, forget about feedback. Fdbk has an emotional F e a r o f u n s p e c i f i e d Subtheme: How fdbk is used impact, disadvantage, (or not). Want fdbk in L’s office as emotional response difficult Unlikely to approach L to Read fdbk/Usually read fdbk, to manage in public, discuss fdbk, Refer to fdbk if doing same Wording doesn’t make much U n l i k e l y t o m a k e a subject, difference, repeated attempt, Not sure fdbk is used, 33510 Compulsory fdbk class, Structured option to get fdbk, Fdbk should be constructive , Fdbk should be about the work and not the person, Experience – fdbk is about the work, Want fdbk to explain grade, Want fdbk to explain what went right, Negative fdbk can be Fdbk should focus on Used fdbk to improve referencing, constructive, understanding, Example: Wrong frame of Negative fdbk can be framed mind, Example: using fdbk to improve Improving understanding in a supportive way. referencing, improves grade, Lecturer variability in framing fdbk. Refer back to example that ‘went Want fdbk in L’s office as right’, emotional response difficult to manage in public. Forget about fdbk until next assignment, Have discussed with tutor, Fdbk applicable to similar assignments, Fdbk on referencing widely applicable, Experience: fdbk focused on referencing, Generic fdbk widely applicable. Table 3: Themes at end of Step 4 AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 33511 3.7 Step 5: Define themes. This is the final refinement of the themes and the aim is to ‘..identify the ‘essence’ of what each theme is about.’.(Braun & Clarke, 2006, p.92). What is the theme saying? If there are subthemes, how do they interact and relate to the main theme? How do the themes relate to each other? In this analysis, What students want from feedback is an overarching theme that is rooted in the other themes. Figure 1 is a final thematic map that illustrates the relationships between themes and we have included the narrative for What students want from feedback below. Emotional response What students want from feedback Potential threat Academic Environment Perceptions of Ls Understanding expectations Use of feedback Why? How? Figure 1: Thematic map. What students want from feedback. Students are clear and consistent about what constitutes effective feedback and made concrete suggestions about how current practices could be improved. What students want from feedback is rooted in the challenges; understanding assessment criteria, judging their own work, needing more specific guidance and perceiving feedback as potentially threatening. Students want feedback that both explains their grades and offers very specific guidance on how to improve their work. They conceptualised these as inextricably linked as they felt that improving understanding would have a positive impact on grades. Students identified that they not only had difficulties in judging their own work but also how or why the grade was awarded. They wanted feedback that would help them to evaluate their own work. AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 33512 ‘Actually if you had to tell me how I got a 60 or 67, how I got that grade, because I know every time I'm due to get my result for an assignment, I kind of go ‘oh I did so bad, I was expecting to get maybe 40 or 50’, and then you go in and you get in the high 60s or 70s. It's like how did I get that? What am I doing right in this piece of work?’ (F1, lines 669-672). Participants felt that they needed specific, concrete suggestions for improvement that they could use in future work. They acknowledged that they received useful feedback on referencing but that other feedback was not always specific enough to be usable. ‘The referencing thing I’ve tried to, that’s the only… that’s really the only feedback we have gotten back ,I have tried to improve, but everything else it’s just kind of been ‘well done’, I don’t… hasn’t really told us much.’ (F1, lines 389-392). Significantly, it emerged that students want opportunities for both verbal and written feedback from lecturers. The main reason identified for wanting more formal verbal feedback is that it facilitates dialogue on issues that may be difficult to capture on paper. Moreover, it seems that feedback enables more specific comments on strengths and limitations of submitted work. However, it is also clear that verbal feedback is valued as the perception that lecturers are taking an interest in individual students is perceived to ‘mean more’. ‘I think also the thing that, you know… the fact that someone has sat down and taken the time to actually tell you this is probably, it gives you an incentive to do it (overspeaking). It does mean a bit more ‘ (M1, lines 456-458). For these participants, the ideal situation was to receive feedback on a one-to-one basis in the lecturer’s office. Privacy is seen as important as students do find feedback potentially threatening and are concerned about managing their reactions in public. For these students, it was difficult to proactively access feedback, largely because the demands of new work limited their capacity to focus on completed work. Given this, they wanted feedback sessions to be formally scheduled. 3.8 Step 6: Writing-up. Usually the end-point of research is some kind of report, often a journal article or dissertation. Table 4 includes a range of examples of articles, broadly in the area of learning and teaching, that we feel do a good job of reporting a thematic analysis. Table 4: Some examples of articles reporting thematic analysis. AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 33513 Gagnon, L.L. & Roberge, G. (2012). Dissecting the journey: Nursing student experiences with collaboration during the group work process. Nurse Education Today, 32(8), 945-950. Karlsen, M-M. W., Wallander; Gabrielsen, A.K., Falch, A.L. & Stubberud, D.G. (2017). Intensive care nursing students’ perceptions of simulation for learning confirming communication skills: A descriptive qualitative study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 42, 97-104. Lehtomäki, E., Moate, J. & Posti-Ahokas, H. (2016). Global connectedness in higher education: student voices on the value of crosscultural learning dialogue. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (11), 2011-2027. Polous, A. & Mahony, M-J. (2008). Effectiveness of feedback: the students' perspectives. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(2), 143-154. 4. Concluding Comments. Analysing qualitative data can present challenges, not least for inexperienced researchers. In order to make explicit the ‘how’ of analysis, we applied Braun and Clarke (2006) thematic analysis framework to data drawn from learning and teaching research. We hope this has helped to illustrate the work involved in getting from transcript(s) to themes. We hope that you find their guidance as useful as we continue to do when conducting our own research. 5. References. Alholjailan, M.I. (2012). Thematic Analysis: A critical review of its process and evaluation. West East Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1), 39-47. Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Sage. Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. Bree, R. & Gallagher, G. (2016). Using Microsoft Excel to code and thematically analyse qualitative data: a simple, cost-effective approach. All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (AISHE-J), 8(2), 2811-28114. AISHE-J Volume 8, Number 3 (Autumn 2017) 33514 Clarke, V. & Braun, V. (2013) Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120-123. Divan, A., Ludwig, L., Matthews, K., Motley, P. & Tomlienovic-Berube, A. (2017). A survey of research approaches utilised in The Scholarship of Learning and Teaching publications. Teaching & Learning Inquiry,[online] 5(2), 16. Javadi, M. & Zarea, M. (2016). Understanding Thematic Analysis and its Pitfalls. Journal Of Client Care, 1 (1) , 33-39. Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16 (1), 1-13. O’Cathain, A., & Thomas, K. J. (2004). “Any other comments?” Open questions on questionnaires – a bane or a bonus to research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 4, 25. Rosenthal, M. (2016). Qualitative research methods: Why, when, and how to conduct interviews and focus groups in pharmacy research. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 8(4), 509-516. Rowland, S.L. & Myatt, P.M. (2014). Getting started in the scholarship of teaching and learning: a "how to" guide for science academics. Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Education, 42(1), 6-14. Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H. & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405.