Supply Chain Management Textbook: Strategy, Planning, Operation

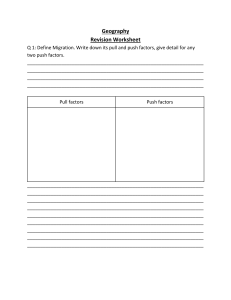

advertisement