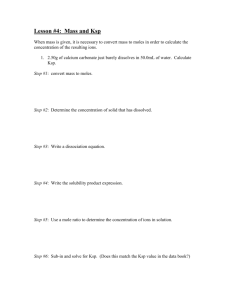

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/1366-5626.htm JWL 30,1 Impacts of organizational knowledge sharing practices on employees’ job satisfaction 2 Mediating roles of learning commitment and interpersonal adaptability Received 30 May 2016 Revised 12 November 2016 5 May 2017 25 July 2017 Accepted 31 August 2017 Muhammad Shaukat Malik Institute of Banking and Finance, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan, and Maria Kanwal Institute of Management Sciences, The Women University Multan, Multan, Pakistan Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to investigate empirically impacts of organizational knowledge-sharing practices (KSP) on employees’ job satisfaction (JS), interpersonal adaptability (IA) and learning commitment (LC). Indirect effects of KSP on JS are also confirmed through mediating factors (LC and IA). Design/methodology/approach – Self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. Knowledge workers from service sector organizations were taken as population of study. Therefore, three types of institutes (banks, insurance and telecom companies) from services sector of Pakistan were selected for sampling purpose. A sample size of 435 employees, comprising 145 employees from each type of institute, was selected. Linear regression analysis and mediation analyses were performed for statistical analysis. Findings – Organizational support for knowledge sharing fosters learning commitment (LC), and interpersonal adaptability (IA) among workforce that ultimately grounds employees’ job satisfaction. Therefore, in our findings, the mediating role of IA is greater than the mediating effect of LC. Research limitations/implications – This study presents a firm reasoning to decision makers for implementation of KSP in the organizations. Findings of study offer several subjects for discussion in the field of KS by academics and research. Present research is limited to test the composite effect of KSP for some selected employee outcomes only. Originality/value – This research attempts to provide empirical evidence about impacts of KSP on employee outcomes. Research work on such issues was lacking in Pakistani context. Therefore, this paper supplies ample of theoretical base for future research as well as management decision makers to maximize the benefits of implementing KSP at their organizations. Keywords Job satisfaction, Interpersonal adaptability, Knowledge sharing practices, Learning commitment Paper type Research paper Journal of Workplace Learning Vol. 30 No. 1, 2018 pp. 2-17 © Emerald Publishing Limited 1366-5626 DOI 10.1108/JWL-05-2016-0044 1. Introduction Knowledge is a significant resource for achievement and sustainability of competitive advantage in businesses (Drucker, 2001). Knowledge management and knowledge sharing (KS) at workplace have turn out to be a topic of great interest for organizations (Ozlati, 2012). Organizations are committed to create, expand and apply both quality and quantity of knowledge within organizational boundaries. This magnitude is even obvious for the firms which trade in knowledge itself and have a high proportion of qualified staff (Blackler, 1995). Alvesson (1995) referred such organizations as “knowledge-intensive firms”. Knowledge as a strategic resource empowers individuals and organizations to achieve several benefits as improved learning, innovation and decision-making. Almahamid et al. (2010) suggested that KS improves an individual’s competencies and satisfaction. KS is defined as an exchange of experiences, facts, knowledge and skills all through the organization (Nonaka and Krogh, 2009). Organization’s ability for the use of knowledge as a resource is extremely dependent on its individuals (Ipe, 2003). Danish et al. (2014) suggested KS as an opportunity for employees to learn from each other and promote organizational learning. Lin (2006) viewed KS as a source of innovation for organizations. It is a source for development of new business possibilities and improvement in work processes (Yi, 2009). Revolutions in business activities and the workplace diversity demonstrate a need for the use of organizational KSP to improve learning by the staff (Almahamid et al., 2010). Training and development opportunities improve individual’s self-efficacy levels (Cabrera and Cabrera, 2005). Abdul Rahman (2011, p.207) established four contributing factors toward KS “environment and infrastructure, management support, culture and technology”. Organizational flow of knowledge (Malhotra and Majchrzak, 2004), procedural veracity or equality among workforce (Bock et al., 2005), development of organizational citizenship behavior and organizational commitment (Skyrme, 2002) are some important organizational aspects for support of KS. Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal (2014) suggested that KS systems support the communication of explicit and tacit knowledge to other individuals by exchange and socialization. Hsu (2008) suggested that KSP include socialization in workgroups, IT systems for communication, training and development and rewards for KS. Socialization mechanisms include discussion groups that facilitate exchange of knowledge and experiences among group members (Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2014). Mechanisms that smooth the progress of exchange include letters, manuals, memos and presentations. Becerra-Fernandez et al. (2004) proposed some employee benefits by knowledge-sharing practices (KSP). Purpose of present research is to investigate empirically impacts of KSP on employees’ job satisfaction (JS). Mediating roles of interpersonal adaptability and learning commitment (LC) are also established in the scope of this research. 2. Literature review Knowledge management literature conferred “Knowledge” in numerous ways. In the views of Lee (2009), knowledge is taken as what a person knows. Davenport and Prusak (1998) discussed knowledge as a mix of experiences, values, background evidence and expert vision, whereas organizational knowledge tends to be ambiguous in nature and absolutely attached to the people who keep it (Nonaka, 1994). Data, information and knowledge are not exchangeable concepts (Wiig, 2012). Knowledge tends to be subjective in nature and is extremely rigid to be codified (Lee, 2009), as it is difficult to imitate knowledge, so individuals’ information transfer has ideal significance (Reychav and Weisberg, 2010). Information has sense, but it is just like a message for which meanings are dependent on the perceptions of its sender and receiver, whereas knowledge is a mixture of different elements that range from contextual information, individual experiences to values and insights of a knowledgeable person (Davenport and Prusak, 1998). Nonaka and Krogh (2009, p. 638) identified that “knowledge alternates between tacit knowledge that may give rise to new explicit knowledge and vice versa”. Tacit knowledge is Organizational knowledge sharing practices 3 JWL 30,1 4 implicit or unarticulated and based on senses, intuition, perceptions or implied rules of thumb. In contrast, the explicit knowledge is expressed and detained in illustrations and writings. Organizations must encourage a know-how culture for sharing to promote transfer of tacit knowledge (Cumberland and Githens, 2012), which is more vital than any technical expansion (Seng et al., 2002). KS is an action of making knowledge accessible for others within or outside the institute (Ipe, 2003). Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal (2014, p. 61) defined KS as “the process through which explicit or tacit knowledge is communicated to other individuals”. AbdulJalal et al. (2013) established KS aptitude as essential for organizational achievement. KS is a course of action where people mutually exchange their knowledge by “donating” and “collecting” knowledge (Hooff and Hendrix, 2005). Sharing of codified records in electronic form, though, saves time but did not improve performance (Haas and Hansen, 2007). Morris (2001) suggested a drastic shift in corporate culture for execution of KS activities. A general corporate belief that “information is power” (Hannabuss, 2002) needs to be replaced by “shared knowledge fabricate power”. Existing literature identifies three factors as enablers for KS. This includes individual factors (Lee and Choi, 2003), organizational factors (Lin, 2007) and technology factors (Taylor and Wright, 2004). Individual and organizational factors considerably control KS processes. It demands willingness of an individual or group of individuals to contribute in sharing for mutual benefits and learning (Sharifuddin et al., 2004). Individual’s motivational behavior either intrinsic or extrinsic is considered as complementary for KS behaviors (Gold et al., 2001). Wang and Noe (2010) developed a framework of research in KS literature which included organizational and cultural perspectives, interpersonal and team aspects along with individual motivational factors. Organizational factors that encourage sharing include ambiance (Hooff and De Ridder, 2004), procedural integrity or staff equality (Bock et al., 2005) and organization’s dedication toward sharing (Skyrme, 2002). Koh and Kim (2004) identified information technology and communication channels as technology factors within organization. Bartol and Srivastava (2002) considered management support and rewards as organizational factors, whereas Lin (2006) concluded that management support in contrary to rewards more effectively motivate employees. Holsapple (2004) suggested that KS involves organizational members for voluntarily contributing their knowledge toward organizational memory. Organizational KS is examined by individual’s formal and informal exchange of knowledge (Bircham, 2003). Dalkir (2005, p. 186) proposed: A knowledge-sharing culture is one where knowledge sharing is the norm, not the exception, where people are encouraged to work together, to collaborate and share, and where they are rewarded for doing so. Introduction of KS systems requires a consideration for cultural needs and culture-specific hurdles to the exchange of knowledge in organization (Ardichvili et al., 2006). It is not possible to arbitrary force employees for KS. Therefore, encouraging members of groups to share knowledge is a significant and challenging issue (Staples and Webster, 2008). Choi et al. (2008) revealed trust and reward systems, as social enablers more significantly smooth KS process as compared to technical support. Holsapple (2004) discussed some influence classes within organizations that effect sharing. Managerial influences include leadership (responsible for development of trust in KS), coordination (development of incentives and reward systems that encourage flow of knowledge) and control (administration of the contents and channels used for KS). An ideal culture for KS is one where communication and synchronization among groups are emphasized (Dalkir, 2005). Exchange of job-related ideas and experiences among team members is termed as KS in teams (Schwarzer, 2014). Organizations smooth the exchange of information in team members, facilitate problem-solving and encourage team work and decision-making (Trivellasa et al., 2015). Both individual and group incentives also smooth the development of cooperative behaviors within workgroups (Siemsen et al., 2007). Information technology is an important factor for KS (Bhatt, 2001). Conventional associations, support and intensity for use of information technology drastically shape KS behaviors (Olatokun and Nneamaka, 2013). Training programs improve an employee’s knowledge, experiences and skills (Nadeem, 2010). Organizations adapt, innovate and compete through training and development opportunities offered to its workforce (Salas et al., 2012). Existing literature revealed two kinds of KS implications: organizational competitive advantages and benefits to the employees (Becerra-Fernandez et al., 2004). KSP offer an agreement for organization’s novelty through socialization, exchange and learning practices (Lin, 2006). Individuals possess diverse knowledge, expertise and capabilities that deviate across organization. Effective coordination and guidance for sharing are essential to use this knowledge for improvement in organizational performance (Almahamid et al., 2010). Adaptability is discussed in literature in provisions of learning for uncertainty in interpersonal, cultural, and work stress-related magnitudes. (Ployhart and Bliese, 2006). Work-related management of emergencies, job stress and uncertain situations is also discussed in the studies of adaptability by Pulakos et al. (2000). Ployhart and Bliese (2006) conceptualized eight dimensions of individual’s adaptive performance, which include IA as a significant aspect of individual’s adaptive performance. IA is an ability to adjust with interpersonal approach to attain a goal (Hartline and Ferrell, 1996). Paulhus and Martin (1988) discussed it as flexibility in behaviors to adjust with a new team, colleague or patrons. A shift from industrialization to service orientation of businesses made it essential for employees to become adaptive interpersonally. IA is inevitable in project teams as well (Schneider, 1994). Employees’ motivation to expand knowledge and their commitment to learn new comprehensions and skills foster enduring success for the business by improving an organization’s competitive gains (Tsai et al., 2007). Learning and attainment of skills are possible only through sharing and deployment of knowledge (Gould, 2009). Personal motivation to revolutionize and learn is a strong base for organizational learning. So, to secure competitive advantage, organizations motivate employees to attain and share knowledge (Senge, 2003). Willingness and ability of individuals to share their experiences are vital for individual’s learning (Lehesvirta, 2004). Meantime sharing opportunities and support for learning at workplace also develop employees’ learning (Li et al., 2009). JS is an expression of individual’s behavior (Schmidt, 2007), tied with an individual’s contentment from physical as well as psychological and emotional perspectives (Hsu, 2009). JS is an outcome of employee’s insight and assessment of his job which take influence by individual’s exclusive needs, ideals and expectations (Sempane et al., 2002). 3. Research model and hypothesis Present research is an attempt to empirically investigate proposed relations among KS and employee benefits by Becerra-Fernandez et al. (2004) in the context of service sector of Pakistan. At first, impacts of KSP (independent variable) are hypothesized for JS, LC and IA as dependent variables. Second, IA and LC are proposed as mediating variables that mediate impacts of KSP on JS. Hypothesized research model of the study is illustrated in Figure 1. Organizational knowledge sharing practices 5 JWL 30,1 M1* Learning Commitment-(LC) H4 6 H2 Organizational Knowledge Sharing Practices--(KSP) Job Satisfaction-((JS) H1 H3 H5 M2* Interpersonal Adaptability-(IA) Figure 1. Hypothesized research model Notes: Black line represents direct paths, whereas green dotted line represents the indirect paths; M1* = indirect effect of KSP on JS through LC (H4); M2* = indirect effect of KSP on JS through IA (H5) Ambition and fascination to share knowledge are associated with employee’s JS (DeVries et al., 2006). Organizational support for the fulfillment of employees’ socioemotional requirements creates positive job attitudes and satisfaction (Cullen et al., 2014). Management support for exchange of ideas among workers promotes employees’ performance (Fernandez, 2008). Strength of the social relations is crucial for KS in teams (Burke, 2011). Positive relations among team work and JS as well as organizational commitment have been identified by Karia and Asaari (2006), whereas informative training opportunities also play considerable role in employee’s overall JS (Schmidt, 2007). Training and learning opportunities improve workers’ level of satisfaction (Lowry et al., 2002). Cross and Cummings (2004) identified strong relations between KS potentials and individual’s outcomes in knowledge-centered businesses. Teh and Sun (2012) discovered positive relations among JS and KS opportunities. Therefore, for present study, first hypothesis is derived as: H1. Organizational KSP are positively related to JS of employees. Socialization practice in organizations helps employees to obtain knowledge and develop skills (Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2014). Almahamid et al. (2010) discovered positive relations among KSP and LC. Hegazy and Ghorab (2014) found positive associations between KS and individual’s learning. Employees’ LCs in the construct of JS take much influence from interpersonal relationships (Tsai et al., 2007), whereas “team learning depends on each member’s individual ability to acquire knowledge, skills, and abilities as well as his or her ability to collectively share that information with teammates” (Day et al., 2004, p. 870). Exchange of knowledge among individuals positively contributes to both individual and organizational learning (Andrews and Delahaye, 2000). Thus, second hypothesis of this study is derived as: H2. Organizational KSP and employees’ LC are positively related. IA depends on individual’s willingness to interact with each other, and KS possibilities available to them (Burke et al., 2006). Pulakos et al. (2006) suggested that KS smooths the progress of individual’s adaptability. Innovation-oriented organizations share knowledge about successes and failures across disciplines, which allows for faster innovation (Krogh et al., 2001). Findings of Tuominen et al. (2004) indicated strong relations between organizational adaptability and innovativeness. When employees get opportunities to interact with others in the organization, they anticipate change, persistently expand knowledge and consequently become more adaptive (Becerra-Fernandez et al., 2004). Hence, third hypothesis of present study is: H3. Organizational KSP significantly impact employees’ IA. Assessment of literature in this study illustrates that KSP have positive relations with employees’ LC and IA same as for JS. At the same time, employees’ LC and IA are positively related with JS. Based on above findings, this study proposed a mediating role of employees’ IA and LC in fourth and fifth hypotheses as: H4. Employees’ LC mediates the relationship between KSP and JS. H5. Employees’ IA mediates the relationship between KSP and JS. 4. Research methodology This research was based on deductive method. To validate the associations among variables, a positivistic approach and quantitative research strategy were used. 4.1 Population and study sample Service sector plays very important role in development of overall economy of a country, and Pakistan is no exemption from this scenario. So, focus for the study was service sector of Pakistan. Therefore, for industry selection, it was primarily concerned with two criteria: first, the industry which considers knowledge management practices as imperative; second, the industry which had developed proper information technology-based infrastructures for sharing of knowledge among workforce (Kim and Lee, 2006). Thus, employees serving in telecom, banking and insurance companies operating all over Pakistan were taken as population of this study. A reason to select these organizations from service sector was knowledge orientation of the tasks performed in such organizations along with the use of up-to-date IT-based infrastructure, which obligates employees for sharing of knowledge with each other. Stratified convenience sampling method was used to make the research purposeful and to get it completed within limited time span. Therefore, the criterion adopted to select sample subjects for this study was that respondents must be holding at least first-line managerial position in the organization. Organizational knowledge sharing practices 7 JWL 30,1 Primary data for the study were collected with the help of survey method. Practically, 540 questionnaires were floated in banks, insurance and telecom companies, out of which 450 responses were received, and among these, 15 questionnaires were incomplete and so rejected from study analysis. Therefore, a sample of 435 knowledge workers was engaged for study, taking 145 respondents from each stratum. Response rate for the study is 81.00 per cent. 8 4.2 Data collection and instrumentation Primary data were collected with the help of a structured questionnaire and assembled based on prior tested and validated instruments in the published literature. Minor adjustments incorporated, so that prior measures suit in the present study context. Participants of the study were requested to rate every item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from (1) as strongly disagree SD to (5) as strongly agree SA. Organizational KSP was measured by seven items from Hsu (2008). The composite reliability of items as reported by Hsu (2008) for this measure is 0.91, whereas reliability tested by Cronbach’s alpha for this research was 0.80. Sample items are “My company offers incentives to encourage knowledge sharing” and “My company offers a variety of training and development programs”. Learning commitment: Five items to measure LC were taken from Tsai et al. (2007) reporting reliability as 0.94. Its reliability for present study was 0.75. Sample statements are “I am willing to spend extra time taking part in the internal and external training courses provided by the firm” and “To me, being able to learn constantly is very important”. Interpersonal adaptability: Individual adaptability measure constructed by Ployhart and Bliese (2006) was used to measure IA. Cronbach’s alpha reported reliability of this measure was 0.80 for this research. Sample items from this measure include the statements as “I am an open- minded person in dealing with others” and “My insights help me to work effectively with others”. Job satisfaction: The measures for JS were used from a shortened version of Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss et al., 1967). This consists of 20 items with reliability as 0.90. Teh and Sun (2012) used 7 out of these 20 items and come up with composite reliability value as 0.912 and convergent validity value as 0.598. Reliability of these items for our study was 0.80. This measure includes the statements as “the chance to make use of my abilities and skills at job” and “the chance to be ‘somebody’ in the community”. 4.3 Data analysis Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 was used for statistical analysis of primary data. Descriptive statistics, correlation coefficients and construct reliability were calculated to check measures of study. To test hypothesis, both simple linear regression analysis and mediation analysis were performed. 5. Results 5.1 Sample descriptions Demographic analysis performed by cross-tabulation is detailed in Table I, sample consisting of 435 respondents involving 145 employees from each type of selected institute comprising 73 per cent male and 27 per cent female respondents. Respondents from an age group of 20-30 years were 45 per cent of total sample, and only 15.4 per cent respondents belong to an age group of 41-50 years. Maximum number of respondents (40.7 per cent) was from less than five years job experience group. In sample group, 35.2 per cent male and 15.6 per cent female respondents Variables Category Male (%) Females (%) Total (%) Age group 20-30 31-40 41-50 126 (28.97) 127 (29.19) 64 (14.71) 317 (72.87) 106 (24.37) 105 (24.14) 106 (24.37) 317 (72.87) 126 (28.97) 127 (29.19) 64 (14.71) 317 (72.87) 116 (26.67) 108 (24.83) 93 (21.38) 317 (72.87) 69 (15.86) 46 (10.57) 3 (0.69) 118 (27.13) 39 (8.97) 40(9.20) 39 (8.97) 118 (27.13) 68 (15.63) 46 (10.58) 4 (0.92) 118 (27.13) 61 (14.02) 51 (11.72) 6 (1.38) 118 (27.13) 195 (44.83) 173 (39.77) 67 (15.40) 435 (100) 145 (33.33) 145 (33.33) 145 (33.33) 435 (100) 194 (44.60) 173 (39.77) 68 (15.63) 435(100) 177 (40.69) 159 (36.55) 99 (22.76) 435 (100) Institution type Managerial position Job experience Total Bank Insurance Telecom Total First-line manager Middle manager Top manager Total <5 5-10 >10 Total Organizational knowledge sharing practices 9 Table I. Sample demographics hold the first-line managerial position, whereas 10.1 per cent male and only 0.9 per cent female respondents have top management positions. 5.2 Construct reliability and correlations As shown in Table II, Cronbach’s alpha for all constructs ranges from 0.75 to 0.81, which is greater than the threshold level of 0.60 set by Kaiser (1974). This establishes reliability of the construct items used to measure variables of study. Pearson correlations in Table II present that no bivariate correlation exists among variables (maximum correlation is 0.557). Moreover, as in a self-report investigation survey, the reliability of construct’s relations is susceptible to the flaw of “common method variance”. To check such variance, Harman’s one-factor analysis was conducted. Our analysis confirmed that common method bias is not a main concern in this study, as only 45 per cent variance was explained by one factor which is less than the 50 per cent cutoff point (Mat Roni, 2014). 5.3 Statistical analysis and hypothesis testing Linear regression analysis was executed three times to test first three hypotheses of study. Findings of model summary, relationship coefficients and regression analysis of variance are presented in Table III. KSP served as predictor for employee’s JS, LC and IA. Model 1 demonstrates a reasonable coefficient of determination. Variance in JS is substantially explained by KSP (R2 = 0.300). Path coefficient (0.496) for KSP and JS is statistically significant (p < 0.01). These findings support first hypothesis of study. Construct KSP LC IA JS KSP LC 1 0.393** 0.498** 0.548** 1 0.545** 0.308** Notes: N = 435; **p < 0.01 IA 1 0.557** JS Mean SD Cronbach’s alpha 1 3.978 4.231 4.205 4.113 0.631 0.607 0.535 0.572 0.80 0.75 0.80 0.81 Table II. Correlation matrix, descriptive statistics and reliability JWL 30,1 10 Model 2 shows that variance in learning commitment is less explained by KSP (R2 = 0.154). Therefore, path coefficient (0.378) for KSP and LC is statistically significant (p < 0.01) supporting second hypothesis of research. Model 3 provides a coefficient of determination for variance in interpersonal adaptability as explained by KSP (R2 = 0.248). Path coefficient (0.423) is statistically significant (p < 0.01) substantiating third hypothesis of research. Regression analysis was conducted separately for three types of institutes presented in Table IV. Findings from telecom suggest that path coefficients for JS (0.594), LC (0.387) and IA (0.422) are statistically significant (p < 0.01). Coefficient of determination for JS (R2 = 0.404) is more than the coefficient of determination calculated for service sector as one cluster in Table III (R2 = 0.300). Variance in LC by KSP (R2 = 0.167) is marginally increased in comparison to (R2 = 0.154) in Table III. Variance in IA of telecom employees is significantly explained by KSP (R2 = 0.303) improved in comparison to (R2 = 0.248) in Table III. Findings from bank data in Table IV also confirm that path coefficients for JS (0.375), LC (0.258) and IA (0.405) are statistically significant (p < 0.01). Variance in JS is partially explained by KSP (R2 = 0.160) in comparison to (R2 = 0.300) in Table III for service sector. Variance in LC (R2 = 0.068) is decreased in comparison to (R2 = 0.154) in Table III. Variance in IA is (R2 = 0.168) decreased in comparison to (R2 = 0.248) in Table III. Regression analysis for insurance companies in Table IV presents that path coefficients for JS (0.505), LC (0.434) and IA (0.418) are statistically significant (p < 0.01). Variance in JS (R2 = 0.345) is more than the one calculated for service sector (R2 = 0.300) in Table III. Variance in LC (R2 = 0.216) is also increased from (R2 = 0.154) in Table III. Variance in IA by KSP (R2 = 0.273) is greater than (R2 = 0.248) in Table III for service sector. 5.4 Mediation analysis Mediation analysis was performed to confirm the mediating effects of IA and LC among the dependency relations of JS and KSP. “Simple mediation model” (Model Number 4) in Table III. Regression analysis for services sector (bank þ insurance þ telecom) Constant KSP R2 F-value Model 1 JS Model 2 LC Model 3 IA 2.139** 0.496** 0.300 185.553** 2.728** 0.378** 0.154 79.001** 2.524** 0.423** 0.248 143.105** Notes: N = 435; **p < 0.01 JS Telecom LC IA JS Banks LC IA Insurance companies JS LC IA Constant 1.658** 2.782** 2.600** 2.663** 3.162** 3.162** 2.143** 2.452** 2.505** KSP 0.594** 0.387** 0.422** 0.375** 0.258** 0.405** 0.505** 0.434** 0.418** 0.404 0.167 0.303 0.160 0.068 0.168 0.345 0.216 0.273 R2 F-value 96.863** 28.626** 62.163** 27.717** 10.365** 28.934** 75.455** 39.367** 53.755** Table IV. Separate regression analysis for each unit Note: **p < 0.01 PROCESS bootstrap approach introduced by Hayes (2013) was used for analysis. Present study proposed two mediating variables: LC (M1) and IA (M2). Mediation model in PROCESS bootstrap was applied two times independently for each mediating variable. Findings of mediation analysis are presented in Table V. “Total effect model” with LC (M1) confirms that KSP positively predicts JS (coefficient = 0.457, p = <0.01, R2 = 0.310) and positive significant relation of LC with JS (coefficient = 0.103, p = <0.05). Total effect of KSP on JS is (0.496), whereas direct effect of KSP (0.457) and indirect effect with M1 is (0.039). It is a small effect size with respect to power of mediation discussed by Kenny (2016). Confidence interval for an indirect effect (BootLLCI: 0.006, BootULCI: 0.084) confirms the significance of effect, as it does not include 0 (Kenny, 2016). These findings support fourth hypothesis of this study. “Total effect model” with IA (M2) as presented in Table V confirms positive significant relation of IA with JS (coefficient = 0.404, p = <0.01) and that KSP predicts JS (coefficient = 0.326, p = <0.01, R2 = 0.407). Total effect of KSP on JS is (0.496), whereas direct effect of KSP (0.326) and indirect effect with M2 is (0.171). It is a medium size significant effect, as confidence interval (BootLLCI: 0.117, BootULCI: 0.242) does not include 0 (Kenny, 2016). These findings validate fifth hypothesis of this study. Organizational knowledge sharing practices 11 6. Discussion Emphasis of present research was to evaluate the impacts of organization’s KSP on its workforce, whereas another vital aspect proposed in this research was to check the interrelations of employee’s outcome variables. Therefore, an attempt has been made to check the mediating effects of IA and LC among the relation of KSP and JS. However, such researches have been formerly reported, but the proposed mediation effects are not investigated in previous studies. Almahamid et al. (2010) empirically substantiated relations among KSP, LC, JS and all kinds of employee adaptability in manufacturing companies at Jordan. Hegazy and Ghorab (2014) in a study on UAE university academic and administrative staff discovered positive associations among KS by means of a corporate Constant LC (M1) IA (M2) KSP R R2 F-value Total effect Direct effect Indirect effect Partially standardized indirect effect Completely standardized indirect effect Ratio of indirect-to-total effect Ratio of indirect-to-direct effect R2 mediation effect size Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 JS-(M1) JS-(M2) 1.858** 0.103* 0.457** 0.557 0.310** 97.084** 0.496** 0.457** 1.119** 0.404** 0.326** 0.638 0.407** 148.449** 0.496** 0.326** 0.039 0.068 0.043 0.079 0.085 0.085 BootLLCI BootULCI 0.006 0.084 0.008 0.141 0.005 0.092 0.012 0.166 0.012 0.199 0.039 0.164 0.171 0.298 0.188 0.344 0.524 0.203 BootLLCI BootULCI 0.117 0.242 0.206 0.402 0.131 0.259 0.242 0.478 0.318 0.917 0.136 0.284 Table V. Mediation analysis (direct and indirect effects of mediators) JWL 30,1 12 portal and individual’s learning and adaptability. Hussain et al. (2016) identified impacts of KS behavior of teams on service novelty and performance in Malaysia. Therefore, no empirical evidence is available from service sector to check such relations. Moreover, this study is first of its kind in the context of service sector of Pakistan. Present study engaged employees of banking, insurance and telecom companies serving in various cities of Punjab province of Pakistan for collection of primary data. Proposed impacts of KSP on JS, LC and IA were empirically tested. Findings of this empirical investigation proved the proposed employee benefits by Becerra-Fernandez et al. (2004) and determine that KSP in organizations positively impact employees’ outcomes, including IA, JS and LC. Logical relations among KSP and employee outcomes confirmed in the study are also in line with the empirical findings of previous studies (Almahamid et al., 2010; Hegazy and Ghorab, 2014). Major outcomes embrace that KS practices are implemented in all three types of institutes under investigation from service sector of Pakistan. KS supported by organizations has significant positive effect on JS directly as well as indirectly through LC and IA as mediators. Research findings from mediation analysis proved the study hypothesis; IA cultivates among workforce because of organizational focus toward KS which in turn improves JS. Same as for LC which results by organizational support for KS and improves the satisfaction level on the job. Mediation analysis results indicate that IA has a medium size mediation effect (indirect effect = 0.171), whereas LC has a small size mediation effect (indirect effect = 0.039). 6.1 Academic and practical implications of the study In Pakistan, there has been little research in the field of knowledge management and KS. Furthermore, no empirical evidence is available from service sector to check impacts of KSP and workforce benefits. This study is first of its nature that discusses impacts of organizational KSP on employees’ IA, LC and JS in the context of service sector of Pakistan. This study contributes to the literature from a theoretical standpoint, as scope of this research embraces an investigation about mediating roles of LC and IA. Han et al. (2016) suggested that KS is a subject in the domain of professional development and workplace learning. Findings of this research also support the need for KSP for workforce learning, IA and JS. Hence, the outcomes serve as a pathway for scholastic persons to advance research on KS issues in relations with employee outcomes. The strategy and findings of this study offer several subjects of discussion for academics as well as research and practice. Practically, this study presents a firm reasoning to decision makers for implementation of KSP in the organizations, as it empirically proves significant positive relation among KSP, JS and IA of service sector employees. KS is critical for effective performance in knowledge-intensive organizations, particularly in service sector all over the world. Presence of positive relations between KSP and IA presents likelihood that employing extroverted individuals intensifies the benefits of KSP; therefore, the study offers a superior decision-making support for organizations in their staffing and recruitment activities. 6.2 Study limitations and directions for future research This study extends the theoretical observations of Becerra-Fernandez et al. (2004) through an empirical investigation in the context of service sector of Pakistan. Scope of this research was limited with regard to some design aspects. These limitations provide directions for future studies in this field. Outcomes of this research are limited to investigate only three types of institutes (bank, insurance and telecom) among service sector of Pakistan. A comparative study among these three or some other service sector institutes to check the role of KSP in JS of employees is a future possibility for research. Second, this study is limited to test the effects of KSP for just three kinds of employee outcomes, i.e. LC, IA and JS. In future, additional impacts of KS approaches need to be investigated empirically. Finally, a composite impact for all KSP on employee outcomes is measured in present study which instigates a strong need to check impacts of each type of KS activity separately in relation to employee outcomes. References Abdul-Jalal, H., Toulson, P. and Tweed, D. (2013), “Knowledge sharing success for sustaining organizational competitive advantage”, Procedia Economics and Finance, Vol. 7, pp. 150-157. Abdul Rahman, R. (2011), “Knowledge sharing practices: a case study at Malaysia’s healthcare research institutes”, The International Information & Library Review, Vol. 43 No. 4, pp. 207-214. Almahamid, S., McAdams, A.C. and Kalaldeh, T. (2010), “The relationships among organizational knowledge sharing practices, employees’ learning commitments, employees’ adaptability, and employees’ job satisfaction: an empirical investigation of the listed manufacturing companies in Jordan”, Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management, Vol. 5, pp. 328-356. Alvesson, M. (1995), “Management of knowledge-intensive companies”, Walter De Gruyter, Vol. 16. Andrews, K.M. and Delahaye, B.L. (2000), “Influences on knowledge processes in organizational learning: the psychosocial filter”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 37 No. 6, pp. 797-810. Ardichvili, A., Maurer, M., Li, W., Wentling, T. and Stuedemann, R. (2006), “Cultural influences on knowledge sharing through online communities of practice”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 94-107. Bartol, K.M. and Srivastava, A. (2002), “Encouraging knowledge sharing: the role of organizational reward systems”, Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 64-76. Becerra-Fernandez, I. and Sabherwal, R. (2014), Knowledge Management: Systems and Processes, Routledge, New York, NY. Becerra-Fernandez, I., González, A.J. and Sabherwal, R. (2004), Knowledge Management: Challenges, Solutions, and Technologies, Pearson/Prentice Hall, New York, NY. Bhatt, G.D. (2001), “Knowledge management in organizations: examining the interaction between technologies, techniques, and people”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 68-75. Bircham, H. (2003), “The impact of question structure when sharing knowledge”, Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 17-24. Blackler, F. (1995), “Knowledge, knowledge work and organizations: an overview and interpretation”, Organization Studies, Vol. 16 No. 6, pp. 1021-1046. Bock, G.W., Zmud, R.W., Kim, Y.G. and Lee, J.N. (2005), “Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate”, Mis Quarterly, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 87-111. Burke, C.S., Pierce, L.G. and Salas, E. (2006), Understanding Adaptability: A Prerequisite for Effective Performance within Complex Environments, Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, Vol. 6. Burke, M.E. (2011), “Knowledge sharing in emerging economies”, Library Review, Vol. 60 No. 1, pp. 5-14. Cabrera, E.F. and Cabrera, A. (2005), “Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 16 No. 5, pp. 720-735. Organizational knowledge sharing practices 13 JWL 30,1 14 Choi, S.Y., Kang, Y.S. and Lee, H. (2008), “The effects of socio-technical enablers on knowledge sharing: an exploratory examination”, Journal of Information Science, Vol. 34 No. 5. Cross, R. and Cummings, J.N. (2004), “Tie and network correlates of individual performance in knowledge-intensive work”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47 No. 6, pp. 928-937. Cullen, K.L., Edwards, B.D., Casper, W.C. and Gue, K.R. (2014), “Employees’ adaptability and perceptions of change-related uncertainty: implications for perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and performance”, Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 269-280. Cumberland, D. and Githens, R. (2012), “Tacit knowledge barriers in franchising: Practical solutions”, Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 48-58. Dalkir, K. (2005), Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice, Elsvier, London. Danish, R., Khan, M., Nawaz, M., Munir, Y. and Nisar, S. (2014), “Impact of knowledge sharing and transformational leadership on organizational learning in service sector of Pakistan”, Journal of Quality and Technology Management, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 59-67. Davenport, T.H. and Prusak, L. (1998), Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know, Harvard Business Press, Boston. Day, D.V., Gronn, P. and Salas, E. (2004), “Leadership capacity in teams”, The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 15 No. 6, pp. 857-880. DeVries, R.E., Hooff, B.V.D. and DeRidder, J.A. (2006), “Explaining knowledge sharing the role of team communication styles, job satisfaction, and performance beliefs”, Communication Research, Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 115-135. Drucker, P. (2001), “The next society”, The Economist, Vol. 52. Fernandez, S. (2008), “Examining the effects of leadership behavior on employee perceptions of performance and job satisfaction”, Public Performance & Management Review, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 175-205. Gold, A.H., Malhotra, A. and Segars, A.H. (2001), “Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective”, Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 185-214. Gould, J.M. (2009). “Understanding Organizations as Learning Systems”, Strategic Learning in a Knowledge Economy. Haas, M.R. and Hansen, M.T. (2007), “Different knowledge, different benefits: toward a productivity perspective on knowledge sharing in organizations”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 28 No. 11, pp. 1133-1153. Han, S.H., Seo, G., Yoon, S.W. and Yoon, D.-Y. (2016), “Transformational leadership and knowledge sharing: Mediating ROLES of employee’s empowerment, commitment, and citizenship behaviors”, Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 130-149. Hannabuss, S. (2002), “Competing with knowledge: the information professional in the knowledge management age”, Library Review, Vol. 51 No. 1, pp. 45-59. Hartline, M.D. and Ferrell, O.C. (1996), “The management of customer-contact service employees: an empirical investigation”, The Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60 No. 4, pp. 52-70. Hayes, A.F. (2013), Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 1st ed., Guilford Press, New York, NY. Hegazy, F.M. and Ghorab, K.E. (2014), “The influence of knowledge management on organizational business processes’ and employees’ benefits”, International Journal of Business and Social Science, Vol. 5 No. 1. Holsapple, C. (2004), Handbook on Knowledge Management 1: Knowledge Matters, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg. Hooff, B.V.D. and De Ridder, J.A. (2004), “Knowledge sharing in context: the influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and cmc use on knowledge sharing”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 8 No. 6, pp. 117-130. Hooff, B.V.D. and Hendrix, L. (2005). “Eagerness and willingness to share: The relevance of different attitudes towards knowledge sharing”, OKLC, available at: www.researchgate.net/publication/ 239918834_EAGERNESS_AND_WILLINGNESS_TO_SHARE_E_RELEVANCE_OF_DIFFE RENT_ATTITUDES_TOWARDS_KNOWLEDGE_SHARING Hsu, H.Y. (2009), Organizational Learning Culture’s Influence on Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Turnover Intention among R&D Professionals in Taiwan during an Economic Downturn, University of Minnesota, Minnesota. Hsu, I.C. (2008), “Knowledge sharing practices as a facilitating factor for improving organizational performance through human Capital: a preliminary test”, Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 35 No. 3, pp. 1316-1326. Hussain, K., Konar, R. and Ali, F. (2016), “Measuring service innovation performance through team culture and knowledge sharing behaviour in hotel services: a PLS approach”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 224, pp. 35-43. Ipe, M. (2003), “Knowledge sharing in organizations: a conceptual framework”, Human Resource Development Review, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 337-359. Kaiser, H.F. (1974), “An index of factorial simplicity”, Psychometrika, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 31-36. Karia, N. and Asaari, M.H.A.H. (2006), “The effects of total quality management practices on employees’ work-related attitudes”, The TQM Magazine, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 30-43. Kenny, D.A. (2016), “Power analsis app MedPower”, Power, available at: www.davidakenny.net/cm/ mediate.htm Kim, S. and Lee, H. (2006), “The impact of organizational context and information technology on employee knowledge-sharing capabilities”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 66 No. 3, pp. 370-385. Koh, J. and Kim, Y.G. (2004), “Knowledge sharing in virtual communities: an e-business perspective”, Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 155-166. Krogh, G.V., Nonaka, I. and Aben, M. (2001), “Making the most of your company’s knowledge: a strategic framework”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 34 No. 4, pp. 421-439. Lee, C.S.E. (2009). “The impact of knowledge management practices in improving student learning outcomes”, Durham E-Theses, Durham University, Durham, available at: http://etheses.dur.ac. uk/242/ Lee, H. and Choi, B. (2003), “Knowledge management enablers, processes, and organizational performance: an integrative view and empirical examination”, Journal of management information systems, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 179-228. Lehesvirta, T. (2004), “Learning processes in a work organization: from individual to collective and/or vice versa?”, Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 16 Nos 1/2, pp. 92-100. Li, J., Brake, G., Champion, A., Fuller, T., Gabel, S. and Hatcher-Busch, L. (2009), “Workplace learning: the roles of knowledge accessibility and management”, Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 347-364. Lin, H.F. (2006), “Impact of organizational support on organizational intention to facilitate knowledge sharing”, Knowledge Management Research & Practice, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 26-35. Lin, H.F. (2007), “Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: an empirical study”, International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 28 Nos 3/4, pp. 315-332. Lowry, D.S., Simon, A. and Kimberley, N. (2002), “Toward improved employment relations practices of casual employees in the new South Wales registered clubs industry”, Human Resource Development Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 53-70. Organizational knowledge sharing practices 15 JWL 30,1 16 Malhotra, A. and Majchrzak, A. (2004), “Enabling knowledge creation in far-flung teams: Best practices for it support and knowledge sharing”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 75-88. Mat Roni, S. (2014), Introduction to SPSS, Edith Cowan University, SOAR Centre, Joondalup. Morris, A. (2001), “Competing with knowledge: the information professional in the knowledge management age”, The Electronic Library, Vol. 19 No. 4, pp. 261-265. Nadeem, M. (2010), “Role of training in determining the employee corporate behavior with respect to organizational productivity: Developing and proposing a conceptual model”, International Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 5 No. 12. Nonaka, I. (1994), “A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation”, Organization Science, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 14-37. Nonaka, I. and Krogh, G.V. (2009), “Perspective-tacit knowledge and knowledge conversion: Controversy and advancement in organizational knowledge creation theory”, Organization Science, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 635-652. Olatokun, W.M. and Nneamaka, E.I. (2013), “Analysing lawyers’ attitude towards knowledge sharing: original research”, South African Journal of Information Management, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 1-11. Ozlati, S. (2012). “Motivation, trust, leadership, and technology: predictors of knowledge sharing behavior in the workplace”, Theses & Dissertations, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont. Paulhus, D.L. and Martin, C.L. (1988), “Functional flexibility: a new conception of interpersonal flexibility”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 55 No. 1, p. 88. Ployhart, R.E. and Bliese, P.D. (2006), “Individual Adaptability (I-Adapt) Theory: Conceptualizing the Antecedents, Consequences, and Measurement of Individual Differences in Adaptability”, in Burke, C.S., Pierce, L.G. and Salas, E. (Eds), Understanding Adaptability: A Prerequisite for Effective Performance within Complex Environments, Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, p. 287. Pulakos, E.D., Arad, S., Donovan, M.A. and Plamondon, K.E. (2000), “Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 85 No. 4, p. 612. Pulakos, E.D., Dorsey, D.W. and White, S.S. (2006), “Adaptability in the workplace: Selecting an adaptive workforce”, Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research, Vol. 6. Reychav, I. and Weisberg, J. (2010), “Bridging intention and behavior of knowledge sharing”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 285-300. Salas, E., Tannenbaum, S.I., Kraiger, K. and Smith-Jentsch, K.A. (2012), “The science of training and development in organizations: What matters in practice”, Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 74-101. Schmidt, S.W. (2007), “The relationship between satisfaction with workplace training and overall job satisfaction”, Human Resource Development Quarterly, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 481-498. Schneider, B. (1994), “HRM-a service perspective: towards a customer-focused HRM”, International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 64-76. Schwarzer, R. (2014), Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action, Taylor & Francis, Abingdon. Sempane, M., Roodt, G. and Rieger, H. (2002), “Job satisfaction in relation to organisational culture”, SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 23-30. Seng, C.V., Zannes, E. and Wayne, R.P. (2002), “The contributions of knowledge management to workplace learning”, Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 138-147. Senge, P.M. (2003), “Taking personal change seriously: the impact of” organizational learning” on management practice”, Academy of Management Executive), Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 47-50. Sharifuddin, S.O., Ikhsan, S. and Rowland, F. (2004), “Knowledge management in a public organization: a study on the relationship between organizational elements and the performance of knowledge transfer”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 95-111. Siemsen, E., Balasubramanian, S. and Roth, A.V. (2007), “Incentives that induce task-related effort, helping, and knowledge sharing in workgroups”, Management Science, Vol. 53 No. 10, pp. 1533-1550. Skyrme, D.J. (2002). “The 3cs of knowledge sharing: culture, co-opetition and commitment”, Entovation International News. Staples, D.S. and Webster, J. (2008), “Exploring the effects of trust, task interdependence and virtualness on knowledge sharing in teams”, Information Systems Journal, Vol. 18 No. 6, pp. 617-640. Taylor, W.A. and Wright, G.H. (2004), “Organizational readiness for successful knowledge sharing: Challenges for public sector managers”, Information Resources Management Journal ( Journal), Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 22-37. Teh, P.L. and Sun, H. (2012), “Knowledge sharing, job attitudes and organisational citizenship behaviour”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 112 No. 1, pp. 64-82. Trivellasa, P., Akrivoulib, Z., Tsiforab, E. and Tsoutsab, P. (2015). “The impact of knowledge sharing culture on job satisfaction in accounting firms: the mediating effect of general competencies”, Procedia Economics and Finance, Athens, pp. 238-247. Tsai, P.C.F., Yen, Y.F., Huang, L.C. and Huang, I.C. (2007), “A study on motivating employees’ learning commitment in the post-downsizing era: job satisfaction perspective”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 42 No. 2, pp. 157-169. Tuominen, M., Rajala, A. and Möller, K. (2004), “How does adaptability drive firm innovativeness?”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 57 No. 5, pp. 495-506. Wang, S. and Noe, R.A. (2010), “Knowledge sharing: a review and directions for future research”, Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 115-131. Weiss, D.J., Dawis, R.V. and England, G.W. (1967). “Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire”, Minnesota studies in vocational rehabilitation. Wiig, K. (2012), People-Focused Knowledge Management, Routledge, New York, NY. Yi, J. (2009), “A measure of knowledge sharing behavior: scale development and validation”, Knowledge Management Research & Practice, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 65-81. Corresponding author Maria Kanwal can be contacted at: maria.kanwal@wum.edu.pk For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com Organizational knowledge sharing practices 17 Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.