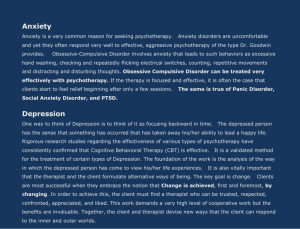

An Introduction to Modern CBT Psychological Solutions to Mental Health Problems ( PDFDrive.com )

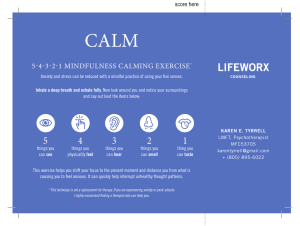

advertisement