A TOOLKIT ON

Designing For

Behavior Change

Stephen Wendel

June 2020

Practical materials to help you

apply techniques from the book,

Designing for Behavior Change

Introduction

1

Designing for Behavior Change at a Glance

Decisions and Behaviors

2

How we CREATE Action

3

DECIDE on Behavioral Interventions

5

Notes

6

Practical Exercises

2

Define the Problem: The Behavioral Project Brief

7

Define the Problem: A Hypothesis for Behavior Change

8

Explore the Context: The Behavioral Plan

9

Explore the Context: CREATE a Micro-Behavior

10

Explore the Context: Refine the Action and Action {Optional}

11

Craft the Intervention: Ways to Start an Action

14

Craft the Intervention: Ways to Stop an Action

15

Craft the Intervention: Evaluate Interventions with CREATE

16

Implement the Intervention: Design a Simple Email

17

Implement the Intervention: Ethical Checklist

18

Determine the Impact: Design the Experiment

20

Evaluate Next Steps: Visualize the Funnel

22

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

Introduction

You have a job to do. Perhaps you’re developing a brand-new product to help people to sleep better

or to learn a language. Or your boss has asked you to increase uptake or usage of your app. Or

maybe you just look around you and see something that doesn’t make sense—from people hurting

the environment, to failing to spend time with their families—and you want to make a difference.

There are traditional ways to do this: Scope out products that are

already out there to solve this problem; Ask your users what else

they are looking for.

The challenge is that these approaches are based on faulty

assumptions about people and how their minds work. Their

assumptions aren’t wrong, but they are incomplete. They assume

that people make careful plans and then thoughtfully execute them.

They assume people know what they’ll do in the future, and why

they’ll do it. Sometimes people do. But often, the reality of user

behavior is just much more complicated than that.

This toolkit will help you design products and communications that

change user behavior, to help your users do something they want to

do, but struggle with. It’s a companion to my book, Designing for

Behavior Change. The book offers a detailed look at why these

assumptions are wrong, how people really make decisions, and

what that means for product development. This guide extracts the

main practical exercises from the book, and puts them in one place:

to help you put those ideas into practice.

In particular, this guide is meant to help you design or refine a product, feature or communication.

It’ll help your users where they struggle to start or stop a key behavior: from exercising regularly, to

getting the most out of your product. It’s not about how to persuade them to do something; here, we

assume user interest, and build up from there.

In this toolkit, I’ve tried to create a short, simple presentation of main themes from the book, although

necessarily I had to drop some important details. These materials are drawn from worksheets I’ve

used with my own teams at Morningstar and HelloWallet.

If you’d like to learn more about this approach, please check out the full book on Amazon or Oreilly.com.

You can also reach out to me anytime at steve@behavioraltechnology.co. I’d love to hear about the

behavioral products you’re working on!

Stephen Wendel

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

1

2

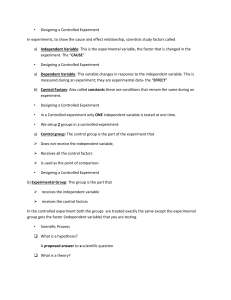

Designing for Behavior Change at a Glance

Decisions and Behaviors

If we were to put decades of behavioral research into a few paragraphs (please forgive me, my fellow

researchers!), it would be these:

We’re limited beings: we have limited attention, time, willpower, etc. For example, there is a

nearly an infinite number of things that your users could be paying attention to at any moment. They

could be paying attention to the person who is trying to speak to them, the interesting conversation

someone else is having near them, or the report on their desktop that’s overdue, or the notification

on your app. Unfortunately, researchers have shown again and again that people’s conscious minds

can really only pay proper attention to one thing at a time.

Our minds use shortcuts to economize and make quick decisions, because of our limitations. Your

users have a myriad of shortcuts (aka heuristics), that help them sort through the range of options

they face on a day-to-day basis, and make rapid, reasonable decisions about what to do. For example,

if they don’t know what to do in a situation, they may look to what other people are doing and try to

do the same (a.k.a. descriptive norms). Similarly, habits are a powerful way in which people’s minds

economize and allow them to act quickly: by immediately triggering a behavior based on a cue.

Unfortunately, these shortcuts can go awry: with ingrained and self-destructive habits (overdrinking) or heuristics that are applied in the wrong context (like herd behavior). Misapplied

heuristics are one cause of biases: negative tendencies in behavior or decision making (differing from

an objective standard of “good”). Often because of these biases, there’s a significant gap between

people’s intentions and their actions.

We’re of two minds: what we decide, and what we do, depends on both conscious thought and

nonconscious reactions like habits. This means that your users are often not “thinking” when they

act; or at least, they’re not choosing consciously. Most of their daily behavior is governed by

nonconscious reactions. Unfortunately, their conscious minds believe that they are in charge all the

time, even when they aren’t. We’re all “strangers to ourselves”: we don’t know the causes of our

own behavior and decisions. Thus your users’ self-reported comments about a problem in your

product or what they plan to do in the future aren’t necessarily accurate.

Decision and behavior are deeply affected by context, worsening or ameliorating our biases and

our intention-action gap. What your users do is shaped by our contextual environment in obvious

ways, like when the architecture of a site directs them to a central home page or to a dashboard. It’s

also shaped by non-obvious ways influences, like the people they talk and listen to (the social

environment), by what they see and interact with (their physical environment), and the habits and

responses they’ve learned over time (their mental environment).

We can cleverly and thoughtfully design a context to improve people’s decision-making and

lessen the intention-action gap. And that is the goal of Designing for Behavior Change and this toolkit.

2

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

Designing for Behavior Change at a Glance

2

How we CREATE Action

From moment to moment, why would you users undertake one action and not another? Six factors

must align, at the same time, before someone will take conscious action. Behavior change products

help people close the intention-action gap by influencing one or more of the following preconditions:

cue, reaction, evaluation, ability, timing, and experience. For ease of remembering them, they spell

CREATE: because that is what’s needed to create

action.

To illustrate these six factors, let’s say your user is

sitting on the couch, watching TV. Your app that

helps him plan and prepare healthy meals for his

family is on his phone; he downloaded last week.

When, and why, would he suddenly get up, find

his mobile phone, and start using the app?

We don’t often think about user behavior in this

way—we usually assume that somehow our

users find us, love what we’re doing, and come

back whenever they want to. But, researchers

have learned that there’s more to it than that,

because of the mind’s limitations and wiring. So,

again imagine your user is watching TV. What

needs to happen for him to use the meal planning

app right now?

1. Cue. The possibility of using the app needs to somehow cross his mind. Something needs to

cue him to think about it: maybe he’s hungry or he sees a commercial about healthy food on

TV.

2. Reaction. He’ll intuitively react to the idea of using the app in a fraction of a second. Is

using the app interesting? Are other people he knows using it? What other options come to

mind, and how does he feel about them?

3. Evaluation. He might briefly think about it consciously, evaluating the costs and benefits.

What will he get out of it? What value does the app provide to him? Is it worth the effort of

getting up and working through some meal plans?

4. Ability. He’ll check whether it’s actually feasible to use the app now. Does he know where

his mobile phone is? Does he have his username and password? If not, he’ll need to solve those

logistical problems first, and then use the app.

5. Timing. He’d gauge when he should take the action. Is it worth doing now, or after the TV

show is over? Is it urgent? Is there a better time? This may occur before or after checking for

the ability to act. Both have to happen though.

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

3

2

Designing for Behavior Change at a Glance

6. Experience. Even if logically using the app is worth the effort, and makes sense to use it

now, he’d be loath to try again if he’d tried the app before (or something like it) and it made

him feel inadequate or frustrated. Idiosyncratic personal experiences can overwhelm any

‘normal’ reaction a person might have.

These six mental processes are gates that can block or facilitate action. You can think of them as

“tests” that any action must pass: Your user must complete them successfully in order for him to

consciously, intentionally, engage in the target action. And, they all have to come together at the

same time. For example, if he doesn’t have the urgency to stop watching TV and act now, he could

certainly do it later. But when “later” comes, he’ll still face these six tests. He’ll reassess whether the

action is urgent at that point (or whether something else, like walking the dog, takes precedence). Or

maybe the cue to act will be gone and he’ll forget about the app altogether for a while.

So, products that encourage people to take a particular action have to somehow cue their users to

think about the action, avoid negative intuitive reactions to it, convince their conscious minds that

there’s value in the action, convince them to do it now, and ensure that they can actually take the

action. We can think about these factors as a funnel: at each step, people could drop off, get

distracted, or do something else. The most common outcome in behavior change work, and the one

we should expect, is the status quo. We seek to nudge that status quo into something new.

If someone already has a habit in place, and the challenge is merely to execute that habit, the process

is mercifully shorter. The first two steps (cue and reaction) are the most important ones, and, of

course, the action still needs to be feasible. Evaluation, timing and experience can play a role, but a

lesser one, because the conscious mind is on autopilot.

4

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

Designing for Behavior Change at a Glance

2

DECIDE on Behavioral Interventions

Behavioral science helps us understand how our environments profoundly shape our decisions and

our behavior. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that a technique that was tested in one setting (often in a

laboratory) doesn’t affect people in the same way in real life. To be effective at designing for behavior

change, we need more than an understanding of the mind: we need a process that helps us find the

right intervention and the right technique for a specific audience and situation.

What does this process look like? I like to think about it as six steps, which we can remember with the

acronym ‘DECIDE’: That’s how we decide on behavior-changing interventions in our products.

Define the

Problem

Explore the

Context

Craft the

Intervention

Implement

the Solution

Determine

the Impact

Evaluate Next

Steps

We start by defining the problem we’re trying to solve. Specifically, we

define the audience we’re working with and the outcome we’re trying to

drive for them. Then as we explore the context, we’ll gather all the

qualitative and quantitative data we can about the audience and their

environment, and see if we can reimagine the action to make it more

feasible and more palatable for the user even before we build anything.

From there, it’s time for crafting the intervention and implementing it in

a product or communication. We’ll talk about how to design the decisionmaking environment—both the product itself and the surrounding

context that the person is in—to support action. We’ll also talk about how

to prepare users to take action with the product. We’ll use the process for

both the conceptual design (figuring out what the product should do) and

the interface design (figuring out how the product should look).

Finally, we’ll test our new design in the field to determine its impact: did

it move the needle or did it flop? Based on that assessment, we’ll evaluate

what do to next. Is it good enough? Because nothing is perfect the first

time, we’ll often need to iteratively refine it. This process also focuses on

three concepts: assessing the current impact on our users, developing

insights and ideas to further improve the product, and then iteratively

changing and measuring the product or communication until it’s served its

purpose (or other priorities intervene).

It’s important to emphasize that the process is inherently iterative. That’s

because human behavior is complicated, and this stuff is hard! If one could

simply wave a magic wand and other people would act differently, we

wouldn’t need a detailed process for designing for behavior change (and

that would be very disturbing). Instead, there’s an iterative process of

learning about our users and their needs, and refining the product if it

misses the mark. The most overlooked, yet the most essential part of the

process isn’t great ideas and nifty behavioral science tricks: It’s careful

measurement of where our efforts go awry, and the wiliness and tools to

learn from those mistakes.

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

5

2

6

Notes

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

3

Practical Exercises: Define the Problem

In this section, you’ll find a series of exercises to use with your team to Design for Behavior Change: using DECIDE and

CREATE. You’ll also see examples of how to fill them out, based on an app that helps people exercise regularly.

The Behavioral Project Brief

Project:

(E.g. Flash, the Exercise App)

________________________________________

New product, feature, or communication?

Change to existing product, feature, or comm.?

VISION Briefly describe why you want to change behavior, and how this product fits in.

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

OUTCOME

What do you hope to achieve with the product? Consider both the company’s objective, as well as the

real-world measurable change that users will see and value. Then, drill down and define a rough metric

that your team can use to evaluate the product, and an idea of what success looks like, in numbers.

Company Objective

Real-world Outcome

E.g. Increase revenue from B2B wellness clients.

E.g. Less pain (back, neck, etc.)

Performance Metric

Definition of Success

E.g. Doctor and Physical Therapy visits

E.g. 50% decrease in Doctor/PT visits

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

7

3

Practical Exercises: Define the Problem

ACTOR

Who is the specific user (or other person involved in the product) who causes the outcome?

___________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

{E.g., sedentary white-collar workers}

USER

If product’s user isn’t the actor, describe the user and how they are supposed to influence the actor.

________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

{E.g., Same}

ACTION

What does the actor do/stop doing to accomplish the outcome? This an initial idea; we’ll refine it later.

_____________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

{E.g., Go to the gym twice a week}

A HYPOTHESIS FOR BEHAVIOR CHANGE

Alternatively, you can write out this information as an explicit hypothesis: to remind the team that,

nothing is for certain, and that you’ll need to test that hypothesis in practice through the product.

By helping {actor}____________________________________ [ ] start [ ] stop doing

{action} _________________________________________________________________,

we will accomplish {outcome}______________________________________________.

SPACE FOR MORE

As you continue the process of Designing for Behavior Change, you may want to update the project

brief with what you discover along the way: the Behavioral Diagnosis, your proposed intervention, etc.

There are worksheets for each of them, but it may be useful for you team to have that info in one place.

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

8

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

Practical Exercises: Explore the Context

3

The Behavioral Plan

START

On the left side of this page, describe each small micro-behavior the user needs to take to move from inaction to

action. Then, on the right, ask whether the six CREATE preconditions for action are in place at each step. Check

existing preconditions off of the list and describe briefly, for reference. Where one is missing, think about how you can

restructure the action, change the environment, or educate the user to help move him or her through the process.

WHAT IS THE USER’S INITIAL STATE?

E.g. Sedentary, does not normally exercise

WHAT DOES THE USER DO FIRST?

E.g. Opens email inviting him or her to download the app

WHAT DOES THE USER DO NEXT?

E.g. Installs app using employee ID and unique password

WHAT DOES THE USER DO NEXT?

E.g. Enters information into app to inform personalized recommendations

FINI

USER TAKES ACTION!

E.g. Goes to a class at the gym!

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

9

Ffff

3

Practical Exercises: Explore the Context

CREATE a Micro-behavior

Select one of the micro-behaviors in your behavioral plan that appears to be a problem – from talking with

users or from the data you’ve gathered. Analyze the CREATE factors for that specific micro-behavior.

When you seek to start a behavior, missing CREATE factor(s) are obstacles. When seeking to stop

a behavior, just document it for now: each factor can be changed to become an obstacle.

Condition

Current Status?

Obstacle? (Y or N)

Cue to think about

taking action

E.g. Relevance of email is unclear.

E.g. Yes

E.g. Aiming for positive.

E.g. No

E.g. Long, multi-step sign-up process.

E.g. Yes

E.g. Ensure all users feel capable

E.g. No

E.g. No urgency or commitment

E.g. Yes

E.g. Varied

E.g. Not sure

Emotional

Reaction

Conscious

Evaluation of costs

and benefits

Ability to act

(resources, logistics,

self-efficacy)

Timing and urgency

to act

Prior Experience

taking action

The Behavioral Diagnosis

Look over your behavioral plan, and CREATE analysis. Steps with major obstacles are where you’ll devote

your attention for the next stage in DECIDE: crafting interventions. The obstacles form a behavioral diagnosis.

We believe that {Actor}____________________________ does not [ ] start [ ] stop doing

{action} ____________________________________, because when it comes time to

{micro-behavior} ________________________________________________________,

{CREATE obstacle} ______________________________________________________.

10

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

Practical Exercises: Explore the Context

3

Refine the Actor and Action {Optional}

For some products, especially existing ones, the actor and action are obvious and not in doubt. In that

case, skip this exercise. However, as you explore the context you may learn more about your users and

their situation, and realize that your initial assumptions were incorrect. If you think the product might

appeal to or help another group, or that your team is offering the same tired solutions that haven’t

worked in the past, this worksheet can help you revisit and refine them.

ACTION

Brainstorm four very different actions that people can take to achieve your target outcome because

of your product or communication. When thinking through possible actions, keep these

points in mind:

•

The obstacles people currently face to achieving the outcome

•

What needs to happen right before the outcome

•

How your company is uniquely positioned to help people achieve the outcome

•

What people who currently achieve the action are doing

Action 1

Action 2

E.g. Solo run 2x per week, starting with 2 miles

E.g. Write down exercise goals

Action 3

Action 4

E.g. Get a personal trainer at the gym

E.g. Participate in an in-person workplace fitness program

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

11

3

Ffff

Practical Exercises: Explore the Context

ACTORS

Create descriptions of the specific people who will take action because of your product. Usually, the

actor is your user – but not always. For example, with B2B products, the person who first engages with

your company may be a corporate buyer, who gives access to the product to users within the company.

For the sake of simplicity though, we’ll refer to the actor as the user here.

Does this user ...

12

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

3

Practical Exercises: Explore the Context

Now, think of a group that is VERY different from the obvious persona.

EVALUATE

Now that you’ve come up with four different actions people can take to achieve the targeted outcome,

evaluate each according to how well it meets the needs of your company and users. Ideally, you’d do this for

each of the 3 personas listed above. To start, though, pick one.

For each action place a scale of 1 through 5 the degree you agree or disagree with the following:

Impact: Taking the action will directly lead to the targeted outcome among the user base.

Ease: Taking the action will not require a lot of resources from users (time, money, etc.)

Cost: Building the new product is a cost-effective use of your company’s resources.

Fit: Supporting the action makes sense for your company’s larger goals and culture.

Score each action across each of the criteria using the table below. Compare total and individual scores to

select the action your team should target. Even though we have attached numbers, there is no hard-andfast rule here: your final decision will depend on the priorities and constraints of your company.

1 - Strongly Disagree

2 - Disagree

3 - Neutral

Action 1

Action 2

Name

E.g. Run 2 miles solo 2x/week.

E.g. Write down exercise goals.

4 - Agree

Action 3

E.g. Get a personal trainer at the gym.

5 - Strongly Agree

Action 4

E.g. Participate in workplace program.

Impact

Ease

Cost

Fit

Total

If you’ve decided on a new target actor or action, update the behavioral brief, and re-do your behavioral plan.

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

13

3

Ffff

Practical Exercises: Craft the Intervention

Craft the Intervention: Ways to Start an Action

For your reference, and to spur ideas for interventions, here are the main techniques described in

Designing for Behavior Change to help your users start taking a conscious action. They are

organized by the primary behavioral obstacle (CREATE) that they help your user overcome.

Component

To Do This

Try This

Cue

Create a cue

Tell the user what the action is

Create a cue

Relabel a cue

Create a cue

Use reminders

Increase power of cue

Make it clear where to act

Increase power of cue

Remove distractions

Target a cue

Go where the attention is

Target a cue

Align with people’s time

Elicit positive feeling

Narrate the past

Elicit positive feeling

Associate with the positive

Increase social motivation

Deploy social proof

Increase social motivation

Use peer comparisons

Increase trust

Display strong authority

Increase trust

Be authentic and personal

Increase trust

Make it professional & beautiful

Economics 101

Make sure the incentives are right

Highlight and support existing motivations

Leverage existing motivations

Highlight and support existing motivations

Avoid direct payments

Highlight and support existing motivations

Test out different types of motivators

Increase motivation

Leverage loss aversion

Increase motivation

Use Commitment Contracts

Increase motivation

Pull future motivations into the present

Increase motivation

Use competition

Support conscious decision making

Make sure it’s understandable

Support conscious decision making

Avoid cognitive overhead

Support conscious decision making

Avoid choice overload

Remove Friction

Remove unnecessary decision points

Remove Friction

Default everything

Remove Friction

Elicit implementation intentions

Increase sense of feasibility (self-efficacy)

Deploy (positive) peer comparisons

Increase sense of feasibility (self-efficacy)

Help them know they’ll succeed

Remove physical barriers

Look for physical barriers

Increase urgency

Frame text to avoid temporal myopia

Increase urgency

Remind of prior commitment to act

Increase urgency

Make commitments to friends

Increase urgency

Make a reward scarce

Reaction

Evaluation

Ability

Timing

14

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

3

Practical Exercises: Craft the Intervention

Experience

Break free of the past

Use Fresh Starts

Break free of the past

Use Story Editing

Break free of the past

Use Slow-down techniques

Avoid the past

Make it intentionally unfamiliar

Keep up with changing experiences

Check back in with users

Ways to Stop an Action

Similarly, here are the main techniques described in Designing for Behavior Change to help your

users stop an unwanted action. They are organized by the type of behavioral obstacle that they create.

Component

To Start

To Stop

Cue

Relabel something as a cue

Unlink the action from other behaviors that flow into

it

Use reminders

Remove reminders

Make it clear where to act

Make the cue more difficult to see or notice

Remove distractions

Add distractions and more interesting actions

Align with people’s time

Move the cue to a time the person is busy, or make the

person busy at the existing time

Narrate the past

Narrate the past to highlight prior successes at

resisting the action

Associate with the positive

Associate with action with negative things the person

doesn’t like

Deploy social proof

Deploy social disproof (show that other people shun

it) and social support for change (AA meetings)

Use peer comparisons

Use negative peer comparisons (show that most other

people resist it, don’t do it)

Be authentic and personal

Be authentic and personal in your appeal to stop

Make it professional & beautiful

Make the surroundings ugly or unprofessional

Make sure the incentives are right

Increase the costs, decrease the benefits

Leverage existing motivations

Unlink the action from existing motivations

Test out different types of motivators

Test out different types of motivators to stop (don’t

assume ‘because it’s good for you’ will work)

Leverage loss aversion

Leverage loss aversion (same!)

Use Commitment Contracts

Use Commitment Contracts (same!)

Pull future motivations into the present

Increase motivation

Use competition

Use competition to stop (e.g. Quit competitions, AA

chips, Biggest Loser)

Avoid cognitive overhead

Add to cognitive overhead

Avoid choice overload

Add to choice overload

Reaction

Evaluation

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

15

3

Ffff

Practical Exercises: Craft the Intervention

Ability

Timing

Experience

Remove unnecessary decision points

Add small pauses and frictions

Default everything

Require choices, remove defaults

Elicit implementation intentions

Elicit implementation intentions (on how to avoid

temping situations)

Deploy (positive) peer comparisons

Deploy positive peer comparisons – examples of other

succeeding at stopping (same!)

Help them know they’ll succeed

Help them know they’ll succeed (same!)

Look for physical barriers

Add physical barriers (no keys to the car, etc.)

Frame text to avoid temporal myopia

Frame text to avoid temporal myopia (same – for the

benefits of stopping)

Remind of prior commitment to act

Remind of prior commitment to act (same, for a

commitment to stop)

Make commitments to friends

Make commitments to friends (same, to stop)

Use Fresh Starts

Use Fresh Starts

Use Story Editing

Use Story Editing

Use Slow-down techniques

Use Slow-down techniques

Evaluate Multiple Interventions with CREATE

When your team is evaluating alternative interventions for a particular micro-behavior or step on the

behavioral plan, you can quickly assess the strengths and weaknesses (from a behavioral perspective)

of each using a checklist like this:

Condition

Current

State

With

Intervention # 1

With

Intervention #2

E.g. Current state w/r to

installing the Flash app

E.g. Invitation email that touts the

benefits of the app

E.g. Invitation email that employs

social proof

Cue to think about taking action

Emotional Reaction

Conscious Evaluation of costs and benefits

Ability to act (resources, logistics, self-efficacy)

Timing and urgency to act

Prior Experience taking action

16

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

Design a Simple Email Announcing Your Product

Here, we’ll design a simple email about the product, building on the behavioral questions you’d ask when

working on the full architecture and layout of the product itself. Take a look at your behavioral plan

— what are the riskiest or more difficult pieces? Use the table on page 14 to select specific techniques to

employ in this email (like scarcity, social proof, etc.) to help users overcome those obstacles.

Start the New Year off Right!

3

1

Start the New Year off Right!

1. Subject Line:

2. Send Day & Time:

3. Short Description:

4. Link Text:

5. Image:

6. Detailed Description:

6 This year, give yourself the most valuable gift of all – a healthy mind and

body. The Flash app can help you do just that. Our certified trainers will

work with you to streamline your routine so reaching your wellness goals is

easier than ever. Not only will you increase your strength and flexibility, but

a healthier you can add another year or more to your life.

Flash is available through your employer, for free! When you join, you’ll

have unlimited access to all of our classes at your local gym, so you can

create a schedule that fits into your life.

To get the Flash App today, visit www.flashapp.com to learn more about

the program, and identify appropriate classes and trainers at your local

gym. You can also call 1-800-123-4567 to speak with our team.

Flash recommends consulting your doctor before starting any new

exercise program. If you have any questions, contact one of our staff

members at trainers@flashapp.com

Ok, that’s a good start. Now, what about this email do you want to test?

ELEMENT TO CHANGE

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

NEW VERSION TO TEST

17

3

Practical Exercises: Implement the Intervention

Implement the Intervention: Ethical Checklist

If your organization has an Institutional Review Board (IRB), or has a process modeled on the IRB, then you

should use the templates and processes from that review board. If you don’t have an IRB, here is a worksheet to

get you started, modeled on tools we’ve starting using on my team. Some fields can be copied directly from the

project brief, or the project brief can be attached for reference.

Practitioner: _______________________ Project: ____________________________ Date: _____________

DESCRIPTION AND PURPOSE

1. Please describe the product, feature, or communication (henceforth: “product”) to be developed.

____________________________________________________________________________

2. What specific behavior (action) does the project seek to change, and does it support or hinder it?

____________________________________________________________________________

3. What behavioral intervention(s) does the product use to support that change?

____________________________________________________________________________

4. Who is the target population (actor)?

____________________________________________________________________________

5. How, if at all, will this benefit that population (user outcome)?

____________________________________________________________________________

6. In what ways might this intervention cause notable harm to the individual, in the short term, or in

the long term (e.g., products that seek to addict their users to its use)

____________________________________________________________________________

7. How will this benefit your organization or team?

____________________________________________________________________________

8. What financial or personal interest do you have in this project succeeding?

___________________________________________________________________________

TRANSPARENCY AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE

1. Does the target audience want to accomplish the outcome? Do they want to change the behavior?

____________________________________________________________________________

2. Does the target audience know that you are seeking to change their behavior? And, if not, will

they be upset when they become aware of it?

____________________________________________________________________________

18

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

Practical Exercises: Implement the Intervention

3

3. Is the user defaulted-out, defaulted-in, or is it a condition of use for the product to interact with

these interventions? Can the user opt-out in a straightforward and transparent manner?

____________________________________________________________________________

4. What steps will be taken to minimize the possibility of coercion?

____________________________________________________________________________

DATA HANDLING AND PRIVACY

If data privacy issues are not already addressed elsewhere in the company’s standard product development

process, this is a good place to cover those issues. If they are covered, skip these.

1. What personal information does this product gather?

____________________________________________________________________________

2. How are those data handled to ensure privacy of the users?

____________________________________________________________________________

FINAL REVIEW

This project been independently reviewed and approved by

___________________________________________________ {name of review body for the company}

on ____________________________________________ ____{date}.

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

19

3

Practical Exercises: Determine the Impact

Design the Experiment

Experiments (e.g., A/B Tests) are often the best way to assess whether your product is having the

desired effect. This worksheet will walk you through the process of designing one.

STEP 1: WHAT’S BEING TESTED?

Control:

Do Nothing

Existing Version

E.g. Do Nothing (Control group not sent an email reminder.)

Variation 1:

E.g. Email reminder, inviting people to sign up for the Flash app, focused on creating peer comparisons and competition.

Variation 2 (if any):

E.g. Email reminder, inviting people to sign up for the Flash app, focused on reaching individual goals, investing in yourself.

What’s the outcome metric?

E.g. Number of signups for the app (short-term outcome of the email campaign); Decreased physical therapy visits (long-term outcome of the app) .

Is it measured the same way for both versions?

Yes [Continue to Step 2]

No/Not Sure [Stop!]

STEP 2: WHAT ARE THE EXTREME OUTCOMES?

What’s the baseline value? (What should the control group have?)

BASELINE:

E.g. 35% of target population (employees of wellness client companies) are currently signed up for the Flash app, based on existing outreach efforts.

What’s the Minimum Meaningful Effect (MME)?

(I.e. the smallest change in the outcome that means you’ve been successful) No idea? Enter the smallest delta seen before.

MME:

E.g. 2.5% increase in enrollment among the target population.

What’s the Largest Viable Effect (LVE)?

(I.e. the largest change in the outcome that you’d expect to have) No idea? Enter 2x the largest delta seen before.

LVE:

E.g. 10% increase in enrollment through the new email campaign.

20

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

STEP 3: CALCULATE SAMPLE SIZE AT THE EXTREMES

For the MME and LVE:

IF THE OUTCOME IS A

PERCENTAGE (CLICKS, SIGNUPS)

AVERAGE (AUM)

Use a power calculation tool for

proportions. You’ll need the Baseline

Percentage and Effect

Size (MME, LVE)

Use a power calculation tool for

continuous values. You’ll need the

Baseline Value, Baseline Standard

Deviation, and Effect

Size (MME, LVE)

You’ll get a sample size

for each one: the MME

Size and LVE Size.

* See BehavioralTechnology.co for links to sample tools. Use 0.9 for “power” and .95 for “alpha”

STEP 4: HOW MANY PEOPLE COULD YOU INCLUDE IN THE TEST?

Do you have a fixed list of people?

Yes (Use the list size.)

No, I have a stream of people over time (What’s your timeline? Calculate how many people you’d see by then.)

NUMBER OF PEOPLE AVAILABLE:

STEP 5: HOW MANY PEOPLE SHOULD BE IN EACH GROUP?

Divide the number of people you have (step 4) by the number of variations (step 1) to calculate the number of

people (sample size) per version. NUMBER OF PEOPLE PER VERSION:

STEP 6: DO YOU HAVE WHAT YOU NEED?

SAMPLE SIZE

DECISION

NEXT STEPS

Stop!

• Move on to other tests

Don’t bother running the test, it can’t

tell you anything.

Less than LVE

More than LVE, Less than MME

More than MME

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

Think carefully!

• Decrease the number of variations

The test might show an impact, but if

it doesn’t, you can’t conclude that the

approach failed.

• Take the risk and go for it

Go for it!

• Go for it, run the test!

You can (relatively) conclusively see if

your approach works or doesn’t work.

• Decrease the number of people,

down to the MME size

• Get more people

• Look for other, clearer tests

• Add variations until each one is

the MME size

21

3

Practical Exercises: Evaluate Next Steps

Visualize Where Users Leak Out of Your Conversion Funnel

In order to understand why an intervention (a communication, feature, or product) did not drive an

intended action, it is important to know where users dropped off. First, use the conversion funnel below

to map out each step that a user must take to move from action to inaction. Then, go back and estimate

what percentage of your population is likely to have dropped off at each step.

Notes:

22

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

4

Contact

Please email Steve with any comments or

suggestions about this workbook:

steve@behavioraltechnology.co

The second edition of Designing for Behavior Change was published

in June 2020 and is available on Amazon.com and Oreilly.com.

A Toolkit for Designing for Behavior Change

23