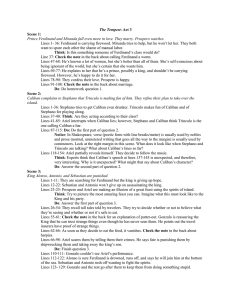

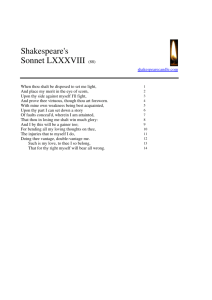

1 of 8 Exam 1 (Feb 22) Marks: 100 Weightage in overall grade: 20% Time: 1h 30 min Format and expectations: Two of the passages below will appear in Exam 1. Of these two options, you will have to write an essay of 450-600 words on any one of them. You will be expected to do a close reading of the given passage in your answer. A close reading is an in-depth analysis of a text and in your response you will be expected to demonstrate knowledge of not just what is happening in the passage, but also how this passage fits in the context of the work as a whole. Your answer should not be a mere summary of the plot! Instead, you should analyse themes, imagery, language, characterisation or any other relevant aspects of the work. Keeping the word length of the response in mind, it is better to write a focused answer in which you show deep engagement with a few key aspects of the text, rather than jumping from one point to another. Resources on close reading: ● https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/closereading/ ● https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/classicswrites/where-begin-and-strategies ● https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/c.php?g=130967&p=4938496 Study guides for the two texts: ● https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/heart-of-darkness/ ● https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/tempest/ ● https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/heart-of-darkness/ ● https://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/tempest/ General essay writing resources: ● https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/quoliterature/ ● https://students.ubc.ca/ubclife/5-tips-writing-class-essay ● https://wts.indiana.edu/writing-guides/paragraphs-and-topic-sentences.html 2 of 8 Grading Rubric (25 marks per assessment objective): 1. Language and organisation: Meaning of sentences is fully clear and the student makes use of correct vocabulary. Response is organised into at least three paragraphs and connections between ideas are clear. 2. Knowledge of text: The response provides context for the passage and is able to connect action or descriptions from the chosen passage with other parts of the play/novella. Response also pays attention to formal/stylistic details such as imagery, tone, metaphors, point-of-view, and so on. 3. Use of evidence: Response refers closely to the given passage to provide relevant evidence for points. Direct quotations are formatted correctly and, on the whole, do not exceed 20% of the response. Student also know how to use partial direct quotations and paraphrasing appropriately. 4. Depth of analysis: Response provides careful analysis of the passage and shows deep understanding of the text's themes, characters, and literary devices. Observations go beyond merely summarising plot points or obvious character traits. OPTION 1 STEPHANO Four legs and two voices—a most delicate monster! His forward voice now is to speak well of his friend. His backward voice is to utter foul speeches and to detract. If all the wine in my bottle will recover him, I will help his ague. Come. [Caliban drinks.] Amen! I will pour some in thy other mouth. TRINCULO Stephano! STEPHANO Doth thy other mouth call me? Mercy, mercy, this is a devil, and no monster! I will leave him; I have no long spoon. TRINCULO Stephano! If thou be’st Stephano, touch me and speak to me, for I am Trinculo—be not afeard—thy good friend Trinculo. 3 of 8 STEPHANO If thou be’st Trinculo, come forth. I’ll pull thee by the lesser legs. If any be Trinculo’s legs, these are they. [He pulls him out from under Caliban’s cloak.] Thou art very Trinculo indeed. How cam’st thou to be the siege of this mooncalf? Can he vent Trinculos? TRINCULO I took him to be killed with a thunderstroke. But art thou not drowned, Stephano? I hope now thou art not drowned. Is the storm overblown? I hid me under the dead mooncalf’s gaberdine for fear of the storm. And art thou living, Stephano? O Stephano, two Neapolitans scaped! STEPHANO Prithee, do not turn me about. My stomach is not constant. CALIBAN [aside] These be fine things, an if they be not sprites. That’s a brave god and bears celestial liquor. I will kneel to him. [He crawls out from under the cloak.] STEPHANO [to Trinculo] How didst thou scape? How cam’st thou hither? Swear by this bottle how thou cam’st hither—I escaped upon a butt of sack, which the sailors heaved o’erboard—by this bottle, which I made of the bark of a tree with mine own hands, since I was cast ashore. CALIBAN I’ll swear upon that bottle to be thy true subject, for the liquor is not earthly. STEPHANO [to Trinculo] Here. Swear then how thou Escapedst. TRINCULO Swum ashore, man, like a duck. I can swim like a duck, I’ll be sworn. STEPHANO Here, kiss the book. [Trinculo drinks.] Though thou canst swim like a duck, thou art made like a goose. TRINCULO O Stephano, hast any more of this? STEPHANO The whole butt, man. My cellar is in a rock by th’ seaside, where my wine is hid.—How now, mooncalf, how does thine ague? 4 of 8 CALIBAN Hast thou not dropp'd from heaven? STEPHANO Out o' the moon, I do assure thee: I was the man i' the moon when time was. CALIBAN I have seen thee in her and I do adore thee: My mistress show'd me thee and thy dog and thy bush. STEPHANO Come, swear to that; kiss the book: I will furnish it anon with new contents swear. TRINCULO By this good light, this is a very shallow monster! I afeard of him! A very weak monster! The man i' the moon! A most poor credulous monster! Well drawn, monster, in good sooth! CALIBAN I'll show thee every fertile inch o' th' island; And I will kiss thy foot: I prithee, be my god. TRINCULO By this light, a most perfidious and drunken monster! when's god's asleep, he'll rob his bottle. CALIBAN I'll kiss thy foot; I'll swear myself thy subject. STEPHANO Come on then; down, and swear. TRINCULO I shall laugh myself to death at this puppy-headed monster. A most scurvy monster! I could find in my heart to beat him,-STEPHANO Come, kiss. TRINCULO But that the poor monster's in drink: an abominable monster! CALIBAN I'll show thee the best springs; I'll pluck thee berries; I'll fish for thee and get thee wood enough. A plague upon the tyrant that I serve! I'll bear him no more sticks, but follow thee, Thou wondrous man. TRINCULO A most ridiculous monster, to make a wonder of a Poor drunkard! CALIBAN I prithee, let me bring thee where crabs grow; And I with my long nails will dig thee pignuts; 5 of 8 Show thee a jay's nest and instruct thee how To snare the nimble marmoset; I'll bring thee To clustering filberts and sometimes I'll get thee Young scamels from the rock. Wilt thou go with me? STEPHANO I prithee now, lead the way without any more talking. Trinculo, the king and all our company else being drowned, we will inherit here: here; bear my bottle: fellow Trinculo, we'll fill him by and by again. CALIBAN [Sings drunkenly] Farewell master; farewell, farewell! TRINCULO A howling monster: a drunken monster! CALIBAN No more dams I'll make for fish Nor fetch in firing At requiring; Nor scrape trencher, nor wash dish 'Ban, 'Ban, Cacaliban Has a new master: get a new man. Freedom, hey-day! hey-day, freedom! Freedom, hey-day, freedom! STEPHANO O brave monster! Lead the way. OPTION 2 “The old doctor felt my pulse, evidently thinking of something else the while. ‘Good, good for there,’ he mumbled, and then with a certain eagerness asked me whether I would let him measure my head. Rather surprised, I said Yes, when he produced a thing like calipers and got the dimensions back and front and every way, taking notes carefully. He was an unshaven little man in a threadbare coat like a gaberdine, with his feet in slippers, and I thought him a harmless fool. ‘I always ask leave, in the interests of science, to measure the crania of those going out there,’ he said. ‘And when they come back, too?’ I asked. ‘Oh, I never see them,’ he remarked; ‘and, 6 of 8 moreover, the changes take place inside, you know.’ He smiled, as if at some quiet joke. ‘So you are going out there. Famous. Interesting, too.’ He gave me a searching glance, and made another note. ‘Ever any madness in your family?’ he asked, in a matter-of-fact tone. I felt very annoyed. ‘Is that question in the interests of science, too?’ ‘It would be,’ he said, without taking notice of my irritation, ‘interesting for science to watch the mental changes of individuals, on the spot, but...’ ‘Are you an alienist?’ I interrupted. ‘Every doctor should be—a little,’ answered that original, imperturbably. ‘I have a little theory which you messieurs who go out there must help me to prove. This is my share in the advantages my country shall reap from the possession of such a magnificent dependency. The mere wealth I leave to others. Pardon my questions, but you are the first Englishman coming under my observation...’ I hastened to assure him I was not in the least typical. ‘If I were,’ said I, ‘I wouldn’t be talking like this with you.’ ‘What you say is rather profound, and probably erroneous,’ he said, with a laugh. ‘Avoid irritation more than exposure to the sun. Adieu. How do you English say, eh? Good-bye. Ah! Good-bye. Adieu. In the tropics one must before everything keep calm.’... He lifted a warning forefinger.... ‘Du calme, du calme.’ “One thing more remained to do—say good-bye to my excellent aunt. I found her triumphant. I had a cup of tea—the last decent cup of tea for many days—and in a room that most soothingly looked just as you would expect a lady’s drawing-room to look, we had a long quiet chat by the fireside. In the course of these confidences it became quite plain to me I had been represented to the wife of the high dignitary, and goodness knows to how many more people besides, as an exceptional and gifted creature—a piece of good fortune for the Company—a man you don’t get hold of every day. Good heavens! and I was going to take charge of a two-penny-half-penny river-steamboat with a penny whistle attached! It appeared, however, I was also one of the Workers, with a capital—you know. Something like an emissary of light, something like a lower sort of apostle. There had been a lot of such rot let loose in print and talk just about that time, and the excellent woman, living right in the rush of all that humbug, got carried off her feet. She talked about ‘weaning those ignorant millions from their horrid ways,’ till, upon my word, she made me quite uncomfortable. I ventured to hint that the Company was run for profit. 7 of 8 OPTION 3 … Then, glancing down, I saw a face near my hand. The black bones reclined at full length with one shoulder against the tree, and slowly the eyelids rose and the sunken eyes looked up at me, enormous and vacant, a kind of blind, white flicker in the depths of the orbs, which died out slowly. The man seemed young—almost a boy—but you know with them it’s hard to tell. I found nothing else to do but to offer him one of my good Swede’s ship’s biscuits I had in my pocket. The fingers closed slowly on it and held—there was no other movement and no other glance. He had tied a bit of white worsted round his neck—Why? Where did he get it? Was it a badge—an ornament—a charm—a propitiatory act? Was there any idea at all connected with it? It looked startling round his black neck, this bit of white thread from beyond the seas. “Near the same tree two more bundles of acute angles sat with their legs drawn up. One, with his chin propped on his knees, stared at nothing, in an intolerable and appalling manner: his brother phantom rested its forehead, as if overcome with a great weariness; and all about others were scattered in every pose of contorted collapse, as in some picture of a massacre or a pestilence. While I stood horror-struck, one of these creatures rose to his hands and knees, and went off on all-fours towards the river to drink. He lapped out of his hand, then sat up in the sunlight, crossing his shins in front of him, and after a time let his woolly head fall on his breastbone. “I didn’t want any more loitering in the shade, and I made haste towards the station. When near the buildings I met a white man, in such an unexpected elegance of get-up that in the first moment I took him for a sort of vision. I saw a high starched collar, white cuffs, a light alpaca jacket, snowy trousers, a clean necktie, and varnished boots. No hat. Hair parted, brushed, oiled, under a green-lined parasol held in a big white hand. He was amazing, and had a penholder behind his ear. “I shook hands with this miracle, and I learned he was the Company’s chief accountant, and that all the book-keeping was done at this station. He had come out for a moment, he said, ‘to get a breath of fresh air. The expression sounded wonderfully odd, with its suggestion of sedentary desk-life. I wouldn’t have mentioned the fellow to you at all, only it was from his lips that I first heard the name of the man who is so indissolubly connected with the memories of that 8 of 8 time. Moreover, I respected the fellow. Yes; I respected his collars, his vast cuffs, his brushed hair. His appearance was certainly that of a hairdresser’s dummy; but in the great demoralization of the land he kept up his appearance. That’s backbone. His starched collars and got-up shirt-fronts were achievements of character. He had been out nearly three years; and, later, I could not help asking him how he managed to sport such linen. He had just the faintest blush, and said modestly, ‘I’ve been teaching one of the native women about the station. It was difficult. She had a distaste for the work.’ Thus this man had verily accomplished something. And he was devoted to his books, which were in apple-pie order.