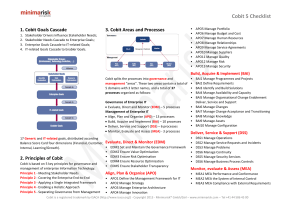

COBIT 5: Enterprise IT Governance and Management Framework

advertisement