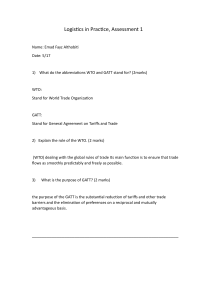

History and Development of the WTO Here is the timeline of the development of the WTO Place/Name Year Geneva Annecy Torquay Geneva Dillon Round Kennedy Round 1947 1949 1951 1956 1960-1961 1964-1967 Tokyo Round 1973-1979 Uruguay Round 1986-1994 Aim Participating Countries Tariffs 23 Tariffs 13 Tariffs 38 Tariffs 26 Tariffs 26 Tariffs, Anti Dumping 62 Measures Tariffs, Non Tariff 102 Measure, “Framework Agreements” Tariffs, Non Tariff 123 Measures, Rules, Services, Intellectual Property, Dispute Settlement, Textiles, Agriculture October 1947 – Signing of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), came into force on January 1948: This was an indication of attempting to give a boost to trade liberalization, especially after many countries suffered severe economic damage from the conclusion of World War 2. This first round of negotiations resulted in a package of trade rules and 45,000 tariff concessions affecting $10 billion of trade, about one fifth of the world’s total. It was a multilateral agreement regulating international trade amongst the 23 participating countries. According to its preamble, its purpose was the "substantial reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers and the elimination of preferences, on a reciprocal and mutually advantageous basis." Though GATT was being formed, most of the participating countries were also in negotiations to create an International Trade Organisation (ITO) charter, as the vision was for this body to effectively carry out and implement the rules surrounding trade which was the aim of GATT. The draft ITO Charter was ambitious. It extended beyond world trade disciplines, to include rules on employment, commodity agreements, restrictive business practices, international investment, and services. Though the initial response of the ITO (signed in 1948 – Havana) was overwhelming supportive, its actual implementation created a major standing block, as ratification of it proved difficult for domestic laws to accommodate. Another issue occurred with the US being the driving force was unable to even implement the charter in its domestic jurisdiction. Therefore, GATT remained the only multinational organization that dealt with international trade, that it until the establishment of the WTO in 1995. Though GATT remained the principal organization that governed the relationship of international trade amongst said nations, there were rounds that were negotiated to potentially improve the conditions and strength of GATT. For almost half a century, the GATT’s basic legal principles remained much as they were in 1948. There were additions in the form of a section on development added in the 1960s and “plurilateral” agreements (i.e. with voluntary membership) in the 1970s, and efforts to reduce tariffs further continued. Much of this was achieved through a series of multilateral negotiations known as “trade rounds” — the biggest leaps forward in international trade liberalization have come through these rounds which were held under GATT’s auspices. In the early years, the GATT trade rounds concentrated on further reducing tariffs. Those rounds were: Annecy (1949): Second GATT round of trade talks held at Annecy, France, where countries exchanged some 5,000 tariff concessions. Torquay (1951): Third GATT round held in Torquay, England, where countries exchanged some 8,700 tariff concessions, cutting the 1948 tariff levels by 25% Geneva (1956): The next trade round completed in May 1956, resulting in $2.5bn in tariff reductions. Dillon Round (1960-61): Fifth Gatt round named in honour of US Under Secretary of State Douglas Dillon who proposed the negotiations. It yielded tariff concessions worth $4.9bn of world trade and involved negotiations related to the creation of the European Economic Community. Such rounds were further negotiations into reducing tariffs states imposed on export and imports. The idea of trade liberalization was slowly taking place, but cultural, economical and general social unwillingness stymied its prominence. GATT was useful for now, but its criticisms emanated from its failure to purely reflect the growth of trade, and what mechanisms should be enforced to reflect changing attitudes of trade. The Kennedy Round (1964-1967) in the mid-sixties brought about negotiations in reducing tariffs, but was known for its GATT anti-dumping Agreement and a section on development. The Kennedy Round, named in honour of the late US president, achieves tariff cuts worth $40bn of world trade. Moreover, the objects of such were to slash tariffs by half with of course minimum exceptions, breaking down farm trade restrictions, removal of non-trade barriers and assisting developing countries. The effect of such was a success for developing nations, as assistance in technology and investment was endorsed in actuality (Caribbean, Africa). A “Trade and Development” section was added to the GATT charter; its most significant feature was excepting developing nations from the rule of reciprocity (states that favours, benefits, or penalties that are granted by one state to the citizens or legal entities of another, should be returned in kind. Reciprocity has been used in the reduction of tariffs, the grant of copyrights to foreign authors, the mutual recognition and enforcement of judgments, and the relaxation of travel restrictions and visa requirements). It also called for the stabilization of raw material prices. Further, the agricultural grains arrangement provided for higher minimum trading prices as well as a food aid program to developing countries. The criticisms of this round surrounded its initiation as a means of political agenda. Economically liberal critics believed that it did not achieve as liberal of goals as the tariff cuts suggest and instead, out of political fears, erected non-tariff barriers to protect domestic industries from the negative effects of trade. The Tokyo Round (1973-1979) during the seventies was the first major attempt to tackle trade barriers that didn’t take the form of tariffs. It aimed at improving the system, adopting a series of agreements on non-tariff barriers, which in some cases interpreted existing GATT rules, and in others broke entirely new ground. The Ministerial declaration setting out the ambit for the negotiations foresaw work aimed at: (a) Tariff negotiations using the formula method, (b) Reducing or eliminating non-tariff measures, (c) Examining the possibility of reducing or eliminating all barriers in selected sectors, (d) Examining the adequacy of the multilateral safeguard system, (e) Negotiations in agriculture, taking into account the special characteristics and problems in this sector, and (f) Treating tropical products as a special and priority sector. GATT had reached an agreement to start reducing not only tariffs but trade barriers as well, such as subsidies and import licensing. Tariff reductions worth more than $300bn dollars achieved. Because plurilateral agreements (voluntary membership) were not accepted by the full GATT membership, they were often informally called "codes". Several of these codes were amended in the Uruguay Round, and turned into multilateral commitments accepted by all WTO members. The Uruguay Round (1986-1994): GATT trade ministers launch the Uruguay Round in Punta Del Este, Uruguay, embarking on the most ambitious and far-reaching trade round so far. The round extended the range of trade negotiations, leading to major reductions in agricultural subsidies, an agreement to allow full access for textiles and clothing from developing countries, and an extension of intellectual property rights. In 1994, trade ministers met for the final time under GATT auspices at Marrakesh, Morocco to establish the World Trade Organization (WTO) and complete the Uruguay Round. This round is considered significant because it has reached a positive outcome on the abolition of quantitative restrictions on imports, not only to regulate trade in goods, but also included trade in services and intellectual property rights, and produced new mechanisms related to settling commercial disputes, and has lasted for more than seven years. The objectives of the Uruguay Round were to reduce agricultural subsidies to lift restrictions on foreign investment to begin the process of opening trade in services like banking and insurance. They also wanted to draft a code to deal with copyright violation and other forms of intellectual property rights. Criticisms of the Uruguay Round - Groups such as Oxfam have criticized the Uruguay Round for paying insufficient attention to the special needs of developing countries, especially agricultural concerns As with the WTO in general, non-governmental organizations(NGOs) such as Health Gap and Global Trade Watch also criticize what was negotiated in the Round on intellectual property and industrial tariffs as setting up too many constraints on policymaking and human needs. An article asserts that the developing countries’ lack of experience in WTO negotiations and lack of knowledge of how the developing economies would be affected by what the industrial countries wanted in the WTO new areas; the intensified mercantilist attitude of the GATT/WTO’s major power, the US.; the structure of the WTO that made the GATT tradition of decision by consensus ineffective, so that a country would not preserve the status quo, were the reasons for this imbalance. The most recent “Round” is the Doha Round. Doha Round This is the current Round. The Round was officially launched at the WTO’s Fourth Ministerial Conference in Doha, Qatar, in November 2001. The Doha Ministerial Declaration provided the mandate for the negotiations, including on agriculture, services and an intellectual property topic, which began earlier. The Round is also known semi-officially as the Doha Development Agenda as a fundamental objective is to improve the trading prospects of developing countries. Its aim is to achieve major reform of the international trading system through the introduction of lower trade barriers and revised trade rules. The work programme covers about 20 areas of trade. In Doha, ministers also approved a decision on how to address the problems developing countries face implementing the current WTO agreements. The aims of the Doha Round are: Agriculture: More market access, eliminating export subsidies, reducing distorting domestic support, sorting out a range of developing country issues, and dealing with nontrade concerns such as food security and rural development. Balance between agriculture and non-agricultural market access (NAMA): To reduce or as appropriate eliminate tariffs, including the reduction or elimination of high tariffs, tariff peaks and tariff escalation (higher tariffs protecting processing, lower tariffs on raw materials) as well as non-tariff barriers, in particular on products of export interest to developing countries”. Services: To improve market access and to strengthen the rules. Each government has the right to decide which sectors it wants to open to foreign companies and to what extent, including any restrictions on foreign ownership. Unlike in agriculture and NAMA, the services negotiations are not based on a “modalities” text. They are being conducted essentially on two tracks: (1) bilateral and/or plurilateral (involving only some WTO members) negotiations and (2) multilateral negotiations among all WTO members to establish any necessary rules and disciplines. Trade facilitation: To ease customs procedures and to facilitate the movement, release and clearance of goods. This is an important addition to the overall negotiation since it would cut bureaucracy and corruption in customs procedures and would speed up trade and make it cheaper. Rules: These cover anti-dumping, subsidies and countervailing measures, fisheries subsidies, and regional trade agreements. The aim is “Clarifying and improving disciplines” under the Anti-Dumping and Subsidies agreements; and to “clarify and improve WTO disciplines on fisheries subsidies, taking into account the importance of this sector to developing countries. The Environment: These are the first significant negotiations on trade and the environment in the GATT/ WTO. They have two key components: o o Freer trade in environmental goods. Products that WTO members have proposed include: wind turbines, carbon capture and storage technologies, solar panels. Environmental agreements. Improving collaboration with the secretariats of multilateral environmental agreements and establishing more coherence between trade and environmental rules. o Geographical indications: multilateral register for wines and spirits: This is the only intellectual property issue that is definitely part of the Doha negotiations. The objective is to “facilitate” the protection of wines and spirits in participating countries. The talks began in 1997 and were built into the Doha Round in 2001. Other intellectual property issues (TRIPPS): Some members want negotiations on two other subjects and to link these to the register for wines and spirits. Other members disagree. These two topics are discussed in consultations chaired by the WTO DirectorGeneral (sometimes a deputy): GI “extension”.(1) Extending the higher level of protection for geographical indications beyond wines and spirits. (2) Biopiracy, benefit sharing and traditional knowledge Dispute settlement: To improve and clarify the Dispute Settlement Understanding, the WTO agreement dealing with legal disputes. These negotiations take place in special sessions of the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB). Exceptionally, they are not part of the “single undertaking” of the Doha Round. General Observation of GATT GATT has made over 47 years a great success in promoting and ensuring a large part of the liberalization of world trade, and helped reductions in customs duties and ensured the growth of trade and production, it has made a lot of achievements and contributions in the field of liberation of some sectors of the international trade and growth. Though it had success in terms of liberalization of international trade, enhancement of the world productivity and reduce tariffs, it was unable to achieve the interests of developing countries and to cope with international changes. Nonetheless, GATT has had its fair share of criticisms and has such opened avenues where economists and scholars alike had discovered its weakness Weakness of GATT - GATT by itself was only the set of rules and multilateral agreements and has no - constituent bases, it was only interested in trade in goods without paying attention to services and intellectual property rights, the role of the commission of disputes of the GATT was slow in resolving disputes and it was being subjected to a degree of disruption. One of the main reasons behind the collapse of the GATT was that the organization was in favor of the industrial countries, and lost confidence among the developing countries the existence of legal problems, particularly in the areas of agriculture and textiles. For example, it can be noted that the United States was not able to convince Japan and China within the framework of the GATT to open its markets to U.S. goods. The absence of an international mechanism to resolve disputes in international trade only made matters worse, as states didn’t have any remedy per se, if they felt aggrieved. The World Trade Organisation Functions What does the WTO do? The World Trade Organisation provides forums whereby states can negotiate agreements centered around reducing trading obstacles that hamper international trade, so that there can be somewhat of a level playing field for trade between member states, which will encourage economic growth and development. Moreover, the WTO has instilled mechanisms, both institutional and legal parameters to monitor and enforce such agreements, and sanctions or methods or settling disputes that will arise from its interpretation and application. Such agreements are both multilateral (16 in all), that is between member states and they are atleast 2 plurilateral agreements, which include some of the member states. Functions of the WTO - negotiating the reduction or elimination of obstacles to trade (import tariffs, other barriers - to trade) and agreeing on rules governing the conduct of international trade (antidumping, subsidies, product standards) administering and monitoring the application of the WTO’s agreed rules for trade in goods, trade in services, and trade-related intellectual property rights administering and monitoring the application of WTO’s rules agreed upon that concerns trading of goods and services, and general trade related to intellectual property rights monitoring and reviewing the trade policies of our members, as well as ensuring transparency of regional and bilateral trade agreements settling disputes through the interpretation and application of the agreements building capacity of developing country government officials in international trade matters assisting the process of accession of some 30 countries who aren’t members of the organization conducting economic research, collecting and disseminating trade data in support of the WTO’s main activities explaining and educating the public about the WTO The WTO was established in 1995, but recognition must be given to GATT for instituting a robust and prosperous international solid trading system, designed to engineer international economical growth. Given GATT’s membership began to increase as more states began to familiarize themselves with its goals, the WTO has presently 153 members, with the majority being developing countries. The Secretariat, located in Geneva comprises of closely to 700 members heads all of its activities. Decisions are instituted by the agreement of all member states The two major bodies that run the administrations of the WTO are: - the Ministerial conference: The topmost decision-making body of the WTO is the - Ministerial Conference, which usually meets every two years. It brings together all members of the WTO, all of which are countries or customs unions. The Ministerial Conference can take decisions on all matters under any of the multilateral trade agreements. General Council: is the WTO’s highest-level decision-making body in Geneva, meeting regularly to carry out the functions of the WTO. It has representatives (usually ambassadors or equivalent) from all member governments and has the authority to act on behalf of the ministerial conference which only meets about every two years. Principles of the WTO - Pursuit of Open Borders - Non discriminatory treatment by and among members - Commitment to transparence in the conduct of activities - Opening of national markets to international trade - The guarantee of most favoured nation principle Key Reporting to General Council (or a subsidiary) Reporting to Dispute Settlement Body Plurilateral committees inform the General Council or Goods Council of their activities, although these agreements are not signed by all WTO members Trade Negotiations Committee reports to General Council Criticisms of the WTO – Consensus Voting An article written by the CIDSE (International Co-operation for Development and Solidarity) titled “A hearing in the WTO for all Members – Guidelines for improving the WTO negotiating process” in May, 2005 was written to emphasize on the unfortunate bleak representation developing nations are subjected to whenever the conference meets to make decisions. Since the WTO’s membership grew, the consensus system which is still utilized has resulted in stymie yet pain staking decision making processes. The consensus voting system is a group decisionmaking process that seeks the consent of all participants. It aims for a “voice” for all member states to have during the decision making process, as such promotes democracy. How so? democracy is promoted as states are given equal representation and the purpose of the WTO is given effect, as it promotes trade development in both developed and developing countries. Though, this consensus system reinforces the WTO being one of the most democratic international institutions, the Seattle Ministerial (1999) prove that even a democratic system can be vulnerable to manipulation by elite nations. The article further went to evaluate the validity of the consensus system in 3 main brackets: - inclusive consensus – will look at how exclusionary processes undermine consensus - - decision making vested interests among officeholders and guidelines for democratizing the negotiating process – will identify how various office holders, particularly the Secretariat and Ministerial functionaries are perceived as being subservient to vested interests guidelines for democratizing the negotiating process – CIDSE’s ideas that can be implemented to encourage more representation and general inclusiveness of developing nations in the ministerials Inclusive Consensus Balancing organizational efficiency with inclusiveness remains the most prominent challenge the WTO is confronted with. Inclusive consensus symbolizes the idea of having an agreement based on the collectivity of approval by all member states. Informals, “Green rooms,” small group meetings, consultations all characterize the process behind WTO negotiations but remain the most criticized aspect of the WTO negotiation process. Non-inclusive meetings which involve some member states discussing negotiations to reach a common position, suffers from not having those established mechanisms needed for decision making, as it is seemingly avoided and as such is consequently, labeled as a parallel decision making authority (meaning) Many of these meetings have caused severe discontent amongst developing nations, as it is labeled as undemocratic, non-transparent and a violation of the consensus principle, the WTO surrounds itself with. E.g. the Seattle Ministerial had so many disagreements that it collapsed owing to the non-transparency of ideas shared in the decision making process. Moreover, there was the criticism that by sacrificing inclusiveness for expediency (the quality of being convenient and practical despite possibly being improper or immoral; convenience) it would caused suspicion and general complaints amongst those excluding leading to questions surrounding the foundation of how the WTO would be governed. Other criticisms drawn by CIDSE on the decision making process of the WTO were: - the representation of developing nations in small group meetings is subject to review, as - they hardly are entertained in discussions. Moreover, these meetings exert pressure on developing nations to agree to some policy, even if the policy is non-transparent and adverse to them a lack of transparency in the decision making process surrounds such meetings as their status is often unclear NB: Many non-governmental organizations, such as the World Federalist Movement, are calling for the creation of a WTO parliamentary assembly to allow for more democratic participation in WTO decision making. Dr Caroline Lucas recommended that such an assembly "have a more prominent role to play in the form of parliamentary scrutiny, and also in the wider efforts to reform the WTO processes, and its rules". However, Dr Raoul Marc Jennar argues that a consultative parliamentary assembly would be ineffective for the following reasons: It does not resolve the problem of "informal meetings" whereby industrialized countries negotiate the most important decisions; It does not reduce the de facto inequality which exists between countries with regards to an effective and efficient participation to all activities within all WTO bodies; It does not rectify the multiple violations of the general principles of law which affect the dispute settlement mechanism. Recommendations: - The article stated that many member states had considered that the WTO should implement an Advisory Group or some sort of Consultative body. Here, this body can assist in narrowing out differences in the preparation of negotiations. Moreover, it can encourage developing nations to give their opinions on a particular matter. Instead of developing nations being forced to organize cohesive groups, they can submit responses to such body Vested Interest Among Officeholders Since the WTO is a membership organization, there are officeholders and most importantly, the Secretariat responsible for delivering assistance and facilitate negotiations amongst member states. The secretariat which comprises of about 600 members is described as relatively small in comparison to other international institutions. Moreover, the report from the Consultative Board noted that the relationship between delegates and staff was tumultuous. The report places emphasis on the relationships of workers but doesn’t provide study evidence of how the Secretariat may be utilized to do the bidding of specific members rather than fulfilling its duty in ensuring the WTO functions as to deliver its mandates. The most senior office in the Secretariat is the Director General yet its role isn’t defined in the Marrakesh Agreement (mark the culmination of the Rounds and established the WTO). Establishing its powers, role, functions, duties, conditions of service and terms of office has never been fully developed. The Consultative Report also found that the Conference’s Chairperson executive decision to appoint friends of the chair to expedite progress within negotiations. The issues and interest of members that are in need of addressing internal institutional reform measures had dissipated since the Cancum post mortems. These issues remain unresolved as such there is a threat that negotiation the decision will remain complicate. The DG was also criticized especially when the Cancum Ministerial concluded. The problems in this Ministerial conference were: - One pressing issue that angered the larger Developed Nations was the unwillingness of - many developing countries to completely open their markets for free trade Too much on the agenda for the amount of time they had, a lack of clear organization for the debates and lectures, and too many countries trying to participate while constantly realigning themselves solely to seek a better outcome for their countries. No one had the intentions to try and strike deals with each other as a whole, rather there were many back door deals throughout the conference as countries tried to swindle around everyone. NB: Since 1986, the membership of this conference has risen by 90 participants to a total of 146 members. This has caused a large dilemma of satisfying all countries’ needs. As many of the earlier participants have already satisfied many of the open trade requirements in their countries, many of the newer countries are reluctant from abiding to the tariff abolition and free trade encouragement. Guidelines for Democratising the Negotiating Process In the article by CIDSE, it concluded by suggesting guidelines to probably be taken into consideration to improve the WTO’s negotiating process. - Members who are excluded from these mini-ministerials should have the benefit of knowing what is going on, as such they should have some status and clarity regarding country participation. - WTO needs to portray democracy, and this can be done by implementing a working - group that invites members to submit various responses from the Advisory Group, as such can offer an impartial report that isn’t motivated by bias (issue of bribery still loams) Green rooms are not decision making forums, so the General Committee doesn’t have to present by should for the conferences The Director General’s powers, roles, functions, appointment should be clearly defined The issue of the Executive Board inviting its friends to sit on the Conference should be addressed also. Member states should have a say in such appointments Decision making must be more transparent as such the system itself should involve from participation from civil society. Can mirror the involvement of the ECOSOC in the UN