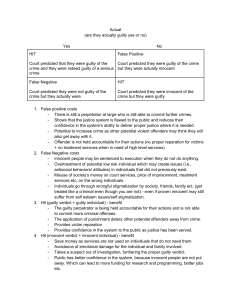

Reflection Piece #1 May’s Theorem Staring Upon Reasonable Doubt May’s theorem states that the fulfillment of universal domain, anonymity, neutrality and positive responsiveness implies a majority rule, furthermore, a majority rule implies the fulfillment of these four principles. In this essay I will navigate through possible rationale to deviate from the majority rule by violating one or more of the principles previously stated. To do so, I will focus on the case of the unanimity rule applied to reaching a verdict in criminal cases (for a jury of twelve, all twelve jurors must vote to convict for a guilty verdict to be the unique outcome). First, I will discuss the ways in which the rule violates neutrality, but follows universal domain, positive responsiveness and anonymity; and then I will introduce reasonable doubt and why it leads to a rational deviation from majority rule. For a rule to be neutral it must satisfy two conditions: in case of equal number of individuals preferring a and b, the rule should specify ab and, if x number of individuals prefer a and y individuals prefer b, the winning alternative in position (x,y) must be either the opposite of the winning alternative of (y,x) or ab in both cases. This rule is easy to view graphically. The first condition of the rule tells us that the anti-diagonal should be ab and that the graph should be symmetrical along the anti-diagonal. Let’s go back to the unanimity rule in a twelve juror situation. The graph above depicts the winning alternative under all preferences of jurors. It is easy to see that this rule is not neutral as the anti-diagonal establishes an innocent verdict and it is not symmetric with respect to the anti-diagonal. But what does this really mean? What the graph is telling us is that ties will always lead to a winner (in this case innocent), and also, that if we switch around the number of votes for both alternatives, the opposite alternative will not win in all cases. For example when neutrality holds, if 7 jurors vote innocent, 5 vote guilty and the verdict is innocent, when we flip the votes around, the verdict should also flip. So, if 7 jurors vote guilty and 5 vote innocent, the verdict should be guilty, however, that is not the case. Now that we have established that the unanimity rule violates neutrality let’s look at why the other three properties hold. Universal domain requires a rule to establish a definite outcome in every possible scenario of individual preferences. Once again, it is easy to see this in the graph, as there is a clear winner for every case of juror votes. In the case of the jury there are three possible options: a majority of jurors vote guilty, a majority votes innocent or there are equal amounts of votes for both options. The unanimity rule determines an alternative in all three cases. Unless all twelve jurors vote guilty, the verdict will be innocent. Similarly anonymity is easy to analyze, as each juror is treated equally and their names have no significance. If we shuffle the names and preferences around, the graph will remain the same. Finally we must look at positive responsiveness. Graphically this is also easy to see. To the south-east of all cases where the verdict is innocent, the verdict is also innocent, and since there is nothing north-west of the only case where the verdict is guilty the principle is satisfied. Thus, as votes increase in favor of the winning verdict, innocent or guilty, (while the votes for the other alternative remain the same), the verdict will still be the previous. Finally, let’s see why there is rationality behind the violation of one of these principles. I believe it is critical to first establish what constitutes a criminal case. This varies from state to state in the United States. For purposes of this essay I will solely focus on New York City legislation. In new York City, there can only be a jury for class “A” misdemeanors (the most serious type of misdemeanor where punishment can be up to one year of jail) and felonies (most serious types of crime including: murder, rape, robbery, arson etc, where punishments are of at least a year in jail and up to life imprisonment). As you can see, the punishments in these types of cases are severe and are not solely limited to the sentence itself. For example, a criminal record can impede you from getting housing or a job. It is here where Blackstone’s Formulation comes into play. William Blackstone was an English jurist who believed, “It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer”. He formulated that the punishments stated above are so harmful that the protection of innocence is a priority. Here is born one of the most important foundations of criminal law in the United States, “everyone is innocent until proven otherwise”. During criminal cases in the United States, the prosecution must prove that the defendant is guilty beyond “reasonable doubt” not the other way around . In case of reasonable doubt the defendant must be allowed to walk free. It is important to highlight the difference between what a juror believes happened and what they are certain happened, we must also take into account that according to the sixth amendment of the Bill of Rights, the jury must be impartial. If there is no sufficient evidence for a juror to be certain the defendant is guilty, there is still “reasonable doubt”, or in other words, a possibility of convicting an innocent person which would be somewhat a crime in of itself. When first coming across Blackstone’s formulation I was ethically conflicted as I was unsure in terms of looking at a society as a whole, if it is better to convict the innocent or to let the guilty walk. However, I then looked at the issue from a legal perspective. The right of liberty is repeatedly mentioned in important founding documents. The declaration of independence states, “ that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”. The constitution of the United States declares, “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” The sixth amendment of the Bill of Rights states, “nor shall any person be deprived .... of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. ” In addition to the unanimity rule being an ethical discussion, it is also one of the law. As shown above, this country was founded upon the idea that the government is present to protect the unalienable rights mentioned in the constitution, including liberty. Applying the unanimity rule to the criminal cases discussed in the previous paragraph ensures that the supreme law of this country is followed. In addition, to think of changing the rule, implies the plausibility of an innocent person’s rights being violated, and is going against the institutions of this country. In both theory and practice, the unanimity rule is the most secure way to protect innocent people and ensure the realization of the United States constitution. I feel we have no choice to conclude that the unanimity rule is the only rule that ensures a society’s rights are fully safeguarded, and is also the one that is most cemented in the laws that this specific society has been abiding by since 1787. The violation of the neutrality rule, in this case, is substantiated by just one innocent person. The presence of disagreement among a jury is not sufficient to crumble an innocent person’s life to pieces, thus, May’s theorem fails when being pitted against one of our most important rights, liberty.