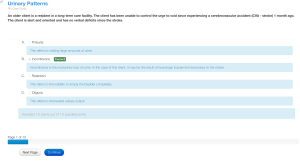

CONTINUED PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Dr Peter du Toit Travelling Fleet Supervisor – Medical Services Cell: +39 3490875696 Email: peter.dutoit@msccruisesonboard.com NEUROLOGICAL EMERGENCIES. PART 2- STROKE ASSESSMENT The World Health Organization (WHO) defines stroke as the rapid development of clinical signs indicating focal (or global) disturbance of cerebral function, persisting for more than 24 hours or resulting in death, with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin. Sudden neurological damage occurs due to one of the following two pathological processes: either hemorrhage or ischemia. Hemorrhage involves an excess of blood within the closed cranial cavity, while ischemia is characterized by insufficient blood supply, leading to inadequate oxygen and nutrient delivery to a specific part of the brain. Managing a patient with a suspected stroke onboard a cruise ship is extraordinarily difficult. Much like the management of Acute Coronary Syndrome, the possible interventions and ultimate outcome for the patient is time sensitive. In PART 2- STROKE ASSESSMENT we will focus on the etiology, classification, epidemiology and early assessment of stroke patients. In PART 3 we will examine the management of a stroke patient onboard a vessel, either in port or at sea. Please allocate sufficient time to review the articles and engage with the educational videos. Developing a comprehensive understanding of the management and risk stratification of high-risk neurological cases is essential. Please review the following references: 1. UPTODATE: Overview of the evaluation of stroke Overview of the evaluation of stroke - UpToDate 2. Royal College of Emergency Medicine’s (RCEM) Stroke in the ED Stroke in the ED - RCEMLearning 3. UPTODATE: Initial assessment and management of acute stroke Initial assessment and management of acute stroke - UpToDate 4. UPTODATE: Clinical diagnosis of stroke subtypes Clinical diagnosis of stroke subtypes - UpToDate Certain passages and algorithms in the reference material will be highlighted in blue and author comments in gray. ** The attached UPTODATE articles are the main source of reference for this CPD** **Please allow your Team access to these articles** 1 STROKE: ETIOLOGY, CLASSIFICATION, AND EPIDEMIOLOGY (UPTODATE) DEFINITIONS Stroke is classified into two major types: • Brain ischemia due to thrombosis, embolism, or systemic hypoperfusion • Brain hemorrhage due to intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) BRAIN ISCHEMIA There are three main subtypes of brain ischemia: • Thrombosis o Thrombotic strokes are those in which the pathologic process giving rise to thrombus formation in an artery produces a stroke either by reduced blood flow distally (low flow) or by an embolic fragment that breaks off and travels to a more distant vessel (artery-to-artery embolism). o Thrombotic strokes can be divided into either large or small vessel disease. o These two subtypes of thrombosis are worth distinguishing since the causes, outcomes, and treatments are different. ▪ Large vessel disease • Large vessels include both the extracranial and intracranial arterial system. • Identification of the specific focal vascular lesion, including its nature, severity, and localization, is important for treatment since local therapy may be effective (e.g., surgery, angioplasty, intra-arterial thrombolysis). • In patients with thrombosis, the neurologic symptoms often fluctuate, regress, or progress in a stuttering fashion. ▪ Small vessel disease • Small vessel disease affects the intracerebral arterial system, specifically penetrating arteries that arise from the distal vertebral artery, the basilar artery, the middle cerebral artery stem, and the arteries of the circle of Willis. • Penetrating artery occlusions usually cause symptoms that develop during a short period of time, hours or at most a few days, compared with large artery-related brain ischemia, which can evolve over a longer period. • Embolism o The symptoms depend upon the region of brain rendered ischemic. o The embolus suddenly blocks the recipient site so that the onset of symptoms is abrupt and usually maximal at the start. o Unlike thrombosis, multiple sites within different vascular territories may be affected when the source is the heart (e.g., left atrial appendage or left ventricular thrombus) or aorta. o Treatment will depend upon the source and composition of the embolus. o Cardioembolic strokes usually occur abruptly, although they occasionally present with stuttering or fluctuating symptoms. o The symptoms may clear entirely since emboli can migrate and lyse, particularly those composed of thrombus. 2 • Systemic hypoperfusion o Reduced blood flow is more global in patients with systemic hypoperfusion and does not affect isolated regions. o The reduced perfusion can be due to cardiac pump failure caused by cardiac arrest or arrhythmia, or to reduced cardiac output related to acute myocardial ischemia, pulmonary embolism, pericardial effusion, or bleeding. o Hypoxemia may further reduce the amount of oxygen carried to the brain. o Symptoms of brain dysfunction typically are diffuse and nonfocal in contrast to the other two categories of ischemia. o Most affected patients have other evidence of circulatory compromise and hypotension such as pallor, sweating, tachycardia or severe bradycardia, and low blood pressure. o The neurologic signs are typically bilateral, although they may be asymmetric when there is preexisting asymmetrical craniocerebral vascular occlusive disease. COMMENT: • For those that prefer to listen to a lecture, here is a short YouTube video regarding Acute Ischemic Stroke. o Acute Ischemic Stroke - Signs and Symptoms (Stroke Syndromes) | Causes & Mechanisms | Treatment - YouTube 3 BRAIN HEMORRHAGE There are two main subtypes of brain hemorrhage: • Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) o Refers to bleeding directly into the brain parenchyma. o Bleeding in ICH is usually derived from arterioles or small arteries. o The bleeding is directly into the brain, forming a localized hematoma that spreads along white matter pathways. o Accumulation of blood occurs over minutes or hours; the hematoma gradually enlarges by adding blood at its periphery like a snowball rolling downhill. o The hematoma continues to grow until the pressure surrounding it increases enough to limit its spread or until the hemorrhage decompresses itself by emptying into the ventricular system or into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on the pial surface of the brain. o The most common causes of ICH are hypertension, trauma, bleeding diatheses, amyloid angiopathy, illicit drug use (mostly amphetamines and cocaine), and vascular malformations. o The earliest symptoms of ICH relate to dysfunction of the portion of the brain that contains the hemorrhage. o The neurologic symptoms usually increase gradually over minutes or a few hours. o In contrast to brain embolism and SAH, the neurologic symptoms related to ICH may not begin abruptly and are not maximal at onset. o Headache, vomiting, and a decreased level of consciousness develop if the hematoma becomes large enough to increase intracranial pressure or cause shifts in intracranial contents. o These symptoms are absent with small hemorrhages; the clinical presentation in this setting is that of a gradually progressing stroke. • Subarachnoid hemorrhage o Refers to bleeding into the cerebrospinal fluid within the subarachnoid space that surrounds the brain. o The two major causes of SAH are rupture of arterial aneurysms that lie at the base of the brain and bleeding from vascular malformations that lie near the pial surface. o Symptoms of SAH begin abruptly in contrast to the more gradual onset of ICH. o The sudden increase in pressure causes a cessation of activity (e.g., loss of memory or focus or knees buckling). o A headache is an invariable symptom and is typically instantly severe and widespread; the pain may radiate into the neck or even down the back into the legs. o Vomiting occurs soon after onset. o There are usually no important focal neurologic signs unless bleeding occurs into the brain and CSF at the same time (meningocerebral hemorrhage). o Onset headache is more common than in ICH, and the combination of onset headache and vomiting is infrequent in ischemic stroke. o Approximately 30 percent of patients have a minor hemorrhage manifested only by sudden and severe headache (the so-called sentinel headache) that precedes a major SAH. o The complaint of the sudden onset of severe headache is sufficiently characteristic that SAH should always be considered. 4 COMMENT: • For those that prefer to listen to a lecture, here is a short YouTube video regarding Acute Hemorrhagic Stroke. o Hemorrhagic Stroke - Intracerebral Hemorrhage & Subarachnoid Hemorrhage | Management - YouTube COMMENT: Stroke: Etiology, classification, and epidemiology - UpToDate • Globally, ischemia accounts for 62%, intracerebral hemorrhage 28%, and subarachnoid hemorrhage 10% of all strokes, reflecting a higher incidence of hemorrhagic stroke in low- and middle-income countries. • In the United States, the proportion of all strokes due to ischemia, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage is 87%, 10%, and 3%, respectively. • • • Guests: Ischemic strokes will be far more common as they are predominantly older and originate from high income countries. Crew: Ischemic strokes will still exhibit a higher incidence but considering the younger demographic and the potential presence of individuals from lower-income countries among the crew, a heightened suspicion for intracerebral hemorrhage is warranted. It is not possible to make a definitive diagnosis of stroke type without imaging studies, however the below table highlights certain characteristics of each stroke subtype to help you differentiate between them to make a presumptive diagnosis. 5 6 IDENTIFYING STROKE MIMICS IN THE ED - EMOTTAWA BLOG Brain Anatomy • Since strokes symptoms occur within the vascular distribution area of the affected artery, it is important to have a basic understanding of brain anatomy to make an appropriate diagnosis. The brain is supplied by 3 main arteries: the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries. By super-imposing the above 2 images, you can infer which parts of the body will be affected during an ischemic event. • From an ED physician perspective, motor and sensory deficits are grossly along the same distribution. • The anterior cerebral artery (ACA) supplies the basal and medial aspects of the cerebral hemispheres and extends to the anterior two-thirds of the parietal lobe. • The middle cerebral artery (MCA) feeds the lenticulostriate branches that supply the putamen, part of the anterior limb of the internal capsule, the lentiform nucleus, and the external capsule. The main cortical branches of the middle cerebral artery supply the lateral surfaces of the cerebral cortex from the anterior portion of the frontal lobe to the posterolateral occipital lobe. • The posterior circulation is smaller and supplies only 20% of the brain. It supplies the brainstem (which is critical for normal consciousness, movement, and sensation), cerebellum, thalamus, auditory and vestibular centers of the ear, medial temporal lobe, and visual occipital cortex. Anterior Cerebral Artery Stroke Occlusion of the ACA is uncommon, but when a unilateral occlusion occurs, it can result in: • Altered mental activity, impaired judgment and insight. • Paralysis and hypoesthesia of the lower limb contralateral to the lesion • Leg weakness is more pronounced than arm weakness. • Apraxia or clumsiness in the patient’s gait • Presence of primitive grasp and suck reflexes on physical examination • Bowel and bladder incontinence • 7 Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke The MCA is the most commonly involved vessel in stroke, and presentation can be quite variable, depending on where the lesion is located, and which brain hemisphere is dominant. Remember, in most people, the left hemisphere is dominant). MCA strokes typically present as: • Contralateral motor and sensory symptoms, usually worse in the arm and the face • Facioplegia • If the dominant hemisphere is involved, can have expressive or receptive aphasia. • If the non-dominant hemisphere is involved, can have hemineglect. • Homonymous hemianopsia and gaze preference toward the affected side may also be seen, regardless of the side of the infarction Posterior Cerebral Artery Stroke PCA infarcts cause the widest variety of symptoms and can be the most difficult to diagnose. The most common presenting complaint is a unilateral headache. PCA stokes can present with: • Homonymous hemianopsia • Visual field defects • Memory loss, alexia, inability to recognize objects or colors. • Vertiginous symptoms 8 9 COMMENT: • The one symptoms of a Stroke that is worth highlighting is HEADACHES. • It is a common presentation complaint amongst both guests and crew. • Around 2% of emergency department (ED) visits involve patients with non-trauma-related headaches, though certain studies propose a rate as elevated as 4%. • Identifying the small subset of individuals with life-threatening headaches from the vast majority experiencing benign primary headaches (such as migraine, tension, or cluster) poses a significant challenge in the ED, but even more for ship’s doctors without access to imaging options. • Overlooking a severe headache can result in grave consequences, including enduring neurological impairments, vision loss, and even fatalities. • Some terminology to be aware of: o Sentinel headache. ▪ A sentinel headache is an episode of headache similar to that accompanying subarachnoid hemorrhage but occurring days to weeks prior to aneurysm rupture. Sentinel headaches develop over seconds and reach maximal intensity within minutes; features of subarachnoid hemorrhage, such as stiff neck, altered consciousness, and focal neurologic symptoms and signs, are absent. o Thunderclap Headache. ▪ Is a very severe headache that begins abruptly and reaches maximum intensity within one minute or less of onset. ▪ The following features are associated with increased odds of subarachnoid hemorrhage in a patient with • Neck stiffness • Nausea, vomiting • Exertion or Valsalva immediately preceding onset of TCH • Elevated blood pressure • Occipital headache • History of smoking • Review the association with headache and vomiting and notice the that nearly 100% of SAH present with headaches. 10 • • • • • When examining a patient with a headache, proactively search for signs and symptoms indicative of a Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH). Document the absence of these findings in your clinical notes, demonstrating that a thorough assessment has been conducted to rule out SAH. Review the following articles at your leisure: o Overview of thunderclap headache - UpToDate SAH is not the only life threating headache. Review the following article at your leisure to update your clinical knowledge on headaches associated with serious pathology. o Evaluation of the adult with nontraumatic headache in the emergency department UpToDate 11 COMMENT: PRE-HOSPITAL ASSESSMENT OF STROKE • In the majority of stroke cases, the initial point of contact for patients is through the medical emergency line, connecting them with a FIRST RESPONDER. • On board our vessels, this role may be fulfilled by a paramedic, nurse, or doctor answering and managing that crucial call. • According to: Stroke and transient ischemic attack | Topic | NICE • Rapid recognition of symptoms and diagnosis • Use a validated tool, such as FAST (Face Arm Speech Test), outside hospital to screen people with sudden onset of neurological symptoms for a diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). 12 COMMENT: FIRST RESPONSE: INITIAL RESPONSE • Telephonic triage poses a challenge on our vessels due to the diverse languages spoken by guests and crew. • Discrepancies between the information the First Responders receive from the Guest Services Agent and actual events are not uncommon. • Where possible, direct communication with the patient or bystander helps the First Responder accurately assess the situation. • If a significant language barrier exists between the caller and First Responder, then the Guest Services Agent normally serves as the sole means of translation. • The First Responder must recognize that time is of the essence in life-threatening medical emergencies. o The necessity for urgency extends beyond the immediate success of emergency interventions; the absence of urgency also brings potential legal implications. o Delays in response correlate with increased risk of unfavorable outcomes and heightened likelihood of incident-related consequences. o Our response time begins the moment the First Responder receives the medical emergency call. • Upon receiving a call related to a possible stroke, the FIRST RESPONDER takes charge of initiating the appropriate response. • Each emergency call presents unique variables, ensuring no two cases are identical. • Below some examples of First Responder responses to consider: • URGENCY OF RESPONSE: o TRIAGE CATEGORY: EMERGENT ▪ Critical incidents where the First Responder is made aware of a guest or a crew member who is unconscious, not moving, not breathing, or not talking should warrant an immediate Mike Echo activation. ▪ The First Responder can obtain this information from the Guest Services Agent or by speaking directly to a family member or a bystander witnessing the event. o TRIAGE CATEGORY: URGENT ▪ Responsive patients with a suspected stroke should result in the on-duty Team assessing the patient at the scene. • PERSONNEL: o Vessels with Paramedics. ▪ TRIAGE CATEGORY: URGENT ▪ Paramedics will likely respond to the scene themselves. ▪ Vessels without Paramedics ▪ TRIAGE CATEGORY: URGENT ▪ In cases where the First Responder is the duty nurse, the duty doctor may accompany the duty nurse to the scene. • Non-medical personnel: NOTE: it is not acceptable for unaccompanied non-medical personnel to respond to the scene or transfer patients to the medical centre. • EQUIPMENT: o First Response equipment will be standardized fleet-wide. This will include a First Response bag and a more advanced bag to respond to Mike Echo’s. o TRIAGE CATEGORY: EMERGENT ▪ All emergency bags, including O2, Suction, Manual defibrillator, and Emergency trolley (Barella) are to be taken to the scene. o TRIAGE CATEGORY: URGENT ▪ First Response bag to scene. If not available at least ensure the following is included in your response: a wheelchair, equipment to check vitals including BP, O2 sats and Blood sugar. 13 LET ME ILLUSTRATE A COUPLE OF SCENARIOS TO FURTHER EXPLAIN THE DIFFERING RESPONSES: SCENARIO 1 • TRIAGE CATEGORY: EMERGENT • 7:30 am. Guest Services receives a 115 call from Cabin 11456. • The husband makes the call on behalf of his wife. He requests immediate medical care, reporting his wife not moving with noisy breathing upon waking. • 7:32 The First Responder is contacted by Guest Services Agent and advised of the request. • 7:35 The First Responder contacts the cabin and speaks directly to the husband. o Mr. Smith confirms that his 75-year-old wife, Mrs. Smith, was fine at 9 pm last night before going to bed but is now unresponsive with noisy breathing. o The First Responder assures Mr. Smith that help is on the way and activates a Mike Echo to Cabin 11456. • 7:40: First responder arrives at scene and starts assessing ABC’s. • 7:45: Rest of the Team arrive with emergency medical equipment. o Assessment: ▪ Airway: Noisy breathing, signs of obstruction • Basic airway maneuvers initiated: chin lift successfully applied. • Suction under vision to remove sputum in front of mouth. • Airway adjuncts considered; concern raised regarded airway patency. ▪ Breathing: • Slow breathing. Rate 5-6 breaths per minute • O2 saturations 85%. Non-Rebreathing face (reservoir) mask placed on face and attached to O2. Improved to O2 saturation of 90% • However, due to slow respiratory rate, bag-valve-mask ventilation started and O2 saturation improves to 95% ▪ Circulation: • Pulse rate: 45 regular, Capillary refill time < 3s, BP 180/110 • IV access gained. ▪ Disability: • Blood sugar: 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) • AVPU - Responds to Painful stimuli. • GCS: 8 E(2) V(2) M(4) • Pupils: Equal and reactive ▪ Exposure: • Temp 37.2ºC, No sign of any trauma It should be obvious that a simple SCOOP AND RUN, i.e., placing her onto a scoop stretcher and immediately transferring her to the MEDICAL CENTRE is NOT acceptable practice. Patients that require medical attention pre-hospital (i.e., not in the medical centre) first need to be assessed (i.e., ABCDE’s) and then it needs to be determined how to safely transfer them to the medical centre. This patient has an AIRWAY, BREATHING and DISABILITY problem. She will need to be stabilized before she is safe to transfer. This is why ALL the emergency equipment; emergency bags and the emergency trolley are brought to the scene during a Mike Echo. A Rapid Sequence Induction can be considered, but this intervention remains controversial in a prehospital setting with stroke patients as some of the data suggests a worse outcome. If you are able to achieve reasonable oxygenation and ventilation, then consider airway adjuncts, NRB facemask or BVM until the patient is in the medical centre. Once in a more controlled environment, then the need for intubation can be reassessed. OBVIOUSLY in a patient with a GCS ≤8 or less where you are unable to maintain the airway or unable to ventilate, then a pre-hospital RSI can be considered. THE SCOOP STRETCHER should NOT be used to transport medical patients to the Medical Centre. 14 SCENARIO 2: TRIAGE CATEGORY: URGENT • 10:30 Guest Services receives a 115 call from Cabin 10145 o The husband made the call on behalf of his wife. He requests medical care, reporting his wife can’t move her arm and is talking strangely. • 10:32 The First Responder is contacted and advised of request. • 10:35 The First Responder contacts the cabin and speaks directly to the husband. o Mr. Jones confirms that his 55-year-old wife, Mrs. Jones, is awake and talking. She is unable to lift her right arm and is slurring her words. o The First Responder assures Mr. Jones that help is on the way. • 10:40 First responder in clinic and asks duty doctor to accompany her to the cabin. o A Mike Echo was not considered appropriate at this moment as the patient is awake and talking. • 10:45 The doctor and nurse arrive at the cabin. o They have brought with them: wheelchair, first response bag and oxygen. o The doctor introduces himself and while taking a history requests the nurse to start taking vitals and blood sugar. o ABCDE assessed. • 11:00 Airway and Breathing OK o Circulation 160/90, Pulse rate 110 o Disability: Blood sugar: 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL), GCS 15/15, Pupils equal and reactive ▪ Left side weakness with affected speech. o Exposure: Temp: 37.1ºC, No sign of any trauma o The duty team have made a presumptive diagnosis of Left sided stroke with Right Hemiparesis and speech impairment. o A risk assessment was made, and the patient deemed safe to be transferred to the Medical Center in a wheelchair. o As she had been lying down in bed, it would be prudent to first sit her up and then swing her legs over the edge of the bed. Repeat the blood pressure and if no significant changes, then she can be helped into the wheelchair and transferred to the Medical Center. If the patient had low blood pressure, then it would not be safe to transfer her by wheelchair. Sitting the patient up and placing her in a wheelchair would result in a further drop in blood pressure leading to less perfusion of the brain and possibly worsen the outcome. A patient with a suspected stroke and low BP needs to be stabilized before transfer and transferred sitting up in a trolley, not flat on their back on a scoop stretcher. Historical transport Modern transport 15 SCENARIO 3: TRIAGE CATEGORY: URGENT • 9:30 am. Guest Services receives a 115 call from Cabin 8133 o The wife made the call on behalf of her husband. She requests medical care, reporting her husband came in late last night. She states that when he woke up this morning, he had been acting strange and had slurred speech. She knows about the FAST signs is concerned that he has had a stroke. • 9:32 The duty Paramedic is contacted and advised of request. • 9:35 The duty Paramedic contacts the cabin and speaks directly to the wife. o Mrs. Walker confirms that his 45-year-old husband, is awake and talking. o He is, however, slurring his speech and acting strangely. o The First Responder assures Mrs. Walker that help is on the way. • 9:40 o The duty Paramedic arrives at the cabin. o He has brought with him: wheelchair, first response bag and oxygen. o The duty Paramedic introduces himself and while taking a history, he also starts taking the patient’s vitals and a blood sugar. o A: Talking, airway patent o B: Respiratory rate 12, O2 sats 98% on air o C: BP 110/60, Pulse rate: 120bpm, Cap refill 3s o Disability: Blood sugar: 3.0 mmol/L. (54 mg/dL), Pupils equal, ▪ GCS 14/15 (E:4, V:4, M:6) slightly confused. o E: No signs of trauma. Temperature 37.4ºC The paramedic diagnosed HYPOGLYCEMIA. Oral glucose is successfully administered and there was no need for IM Glucagon. Further slow acting carbohydrates were taken by the patient, and he made a quick full recovery. Repeat vitals were normal with blood sugar now: 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) and GCS 15/15. Mr. Walker admitted to overindulging in alcohol the night before. Mrs. and Mrs. Walker declined any further medical treatment and were deemed safe to be left alone by the Paramedic. This is an important message when dealing with any patient with neurological deficit. Checking the blood sugar should be one of the very first actions to consider. In the Irish Clinical Practice Guidelines for Paramedics, Stroke section, you will notice how high up the Glucose check is when dealing with a patient with acute neurological symptoms. 2021 edition CPGs (phecit.ie) 16 COMMENT: ASSESSMENT OF STROKE • The overwhelming majority of patients will arrive in the medical centre via the first responders. • However, if a patient presents directly to the medical centre with any FAST signs, they should immediately be taken to the Resuscitation Ward and the duty doctor contacted. • Stroke constitutes a medical emergency, and the care delivered within the initial hours significantly influences patients' long-term recovery and prognosis. • Most Emergency Rooms (ER) ashore will have Stroke Protocols/ Code Stroke alert systems to quickly identify patients eligible for thrombolysis and or mechanical thrombectomy. • Example: Triage, Treatment, and Transfer | Stroke (ahajournals.org) o Code Stroke alerts including ▪ (1) prenotification: ambulance to the ED or directly to stroke team and ED notification to stroke team, ▪ (2) rapid assessment of airway, breathing, circulation, and disability, with assignment of triage category to be seen in <10 min, ▪ (3) rapid patient registration or use of a preregistration alias, ▪ (4) priority use of CT scanner, ▪ (5) immediate intravenous access, with blood drawn for standard laboratory tests, ▪ (6) immediate transfer to CT directly from ambulance after obtaining a brief but thorough history including time last seen normal, anticoagulant use, and medical–surgical history pertinent to thrombolysis risks, ▪ (7) rapid imaging interpretation by stroke team and completion of the NIHSS, ▪ (8) rapid control of arterial blood pressure as indicated by r-tPA treatment criteria, with infusion kit brought to CT to expedite treatment, and ▪ (9) r-tPA bolus and infusion initiated on CT scanning bed when possible o As urgent administration of thrombolysis provided ≤4.5 hours from symptom onset is one of the few proven interventions for stroke, the aim of rapid triage is to commence immediate assessment of suitability for this treatment. • • • • • • • • The primary goal of rapid triage, immediate assessment, and imaging is to determine whether the patient is eligible for thrombolysis. Part of that assessment is the use of a non-contrast computed tomography (CT) to differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Without stating the obvious, currently we cannot perform CT scans onboard the vessel. Therefore. we are unable to differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Therefore, we are unable to safely administer IV thrombolysis to a suspected stroke patient. The reason thrombolysis and CT scans are mentioned in this CPD is that the vessel could be in a port where these facilities are available. It is therefore imperative that while you are in port, you manage these cases with the same attention to speed that a land-based ER would. When in port, all attempts should be made to contact the local emergency services and IMMEDIATELY disembark the patient. WE WILL NOW FOCUS ON THE STEP-BY-STEP ASSESSMENT OF A SUSPECTED STROKE PATIENT. 17 ACCORDING TO STROKE IN THE ED - RCEMLEARNING THE AIMS OF ACUTE MANAGEMENT ARE: • • • • Restoration of brain perfusion to reduce the effects of the primary insult and prevent secondary brain injury. Thrombolysis. Patients presenting within a few hours of symptom onset may benefit from administration of the thrombolytic agent tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA). The patient should, therefore, have a focused medical history, including exact time of onset of symptoms, and be urgently assessed for the inclusion and exclusion criteria of stroke thrombolysis. The evidence base for thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke indicates benefit if delivered within 4.5 hours. ABC • All patients will benefit from appropriate management of their airway, breathing and circulation. Close control of temperature and glucose levels can reduce stroke-associated morbidity. • Airway protection and Breathing • o o o o o • A comatose patient may need careful positioning, and even intubation, if unable to maintain or protect an airway. A patient with significant weakness can slump on the trolley, partially obstructing their airway, so reducing the effectiveness of their breathing. Secondary brain injury due to hypoxia must be avoided. In general, patients with acute stroke without respiratory co-morbidities may be permitted to adopt any body position that they find most comfortable, while those with respiratory compromise should be positioned as upright as possible, avoiding slouched or supine positions to optimize oxygenation. This must be balanced against the improved cerebral blood flow seen if a patient is lying flat. Supplementary oxygen should not be administered routinely. It should only be given if required to achieve an oxygen saturation of 94-98% (88-92% for patients with coexisting risk of COPD or other risk of respiratory acidosis). Stroke patients should be nil by mouth until their ability to swallow (and therefore avoid aspiration) has been properly assessed. Circulation o o o o o Patients are often dehydrated following a stroke. A patient may have been on the floor all night or may have swallowing difficulties. Poorer outcomes occur if systolic BP is less than 100mmHg or diastolic is less than 70mmHg. Hydration should be assessed, and hypovolemia treated with fluid boluses of 250-500ml of normal saline. Fluid overload should also be avoided as it will exacerbate cerebral oedema – a cause of further brain injury in stroke. The aim is euvolemia. Other causes of hypotension, such as sepsis or acute myocardial infarction, should be considered. Hypertension should very rarely be treated in the acute phase. In patients being considered for thrombolysis, a blood pressure target of less than 185/110 mmHg should be achieved. 18 • Pyrexia o Pyrexia after stroke onset is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality. o No trial has been done to show whether treating the fever improves outcome, but it seems reasonable to give antipyretics, and look for signs of infection such as urinary tract infection. o Line insertion and urinary catheter placement in the ED, should follow infection control principles, but should, as far as possible, be avoided. • Hyperglycemia o Studies have shown that hyperglycemia is associated with poor outcomes after ischemic stroke, including in those patients treated with thrombolytic agents. There is an increased intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) rate. o The effects of hyperglycemia on long-term outcome are similar to those seen after acute myocardial infarction. Known diabetic patients also have poorer outcomes. o The evidence for improved outcome with treatment of hyperglycemia is not so clear. Current consensus seems to be that patients with acute stroke should be treated, to maintain a glucose concentration between 5 and 15mmol/l (previously 4-11mmol/l), while being careful to avoid hypoglycaemia. This may require the use of an insulin sliding scale and glucose, or the patient’s own oral hypoglycemic agents, if the patient can swallow. • Focused Neurological Examination o In order to determine the functional severity of a stroke and allow objective assessment of a patient’s progress, use of a standardized stroke scoring tool is essential. o The most widely adopted tool is the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, first described in 1989 and modified subsequently. o Although the decision to thrombolyse is not made solely on the basis of this scoring system, it is used in thrombolysis protocols to provide an objective baseline assessment of the neurological deficit against which improvement, or deterioration, can be judged. COMMENT: • Another good website to review the ABCD approach is: STROKE | ACUTE MANAGEMENT | ABCDE | GEEKY MEDICS 19 COMMENT: ASSESSMENT OF STROKE MIMICS • • During the initial assessment of a suspected stroke patient, ensure you are actively looking for stroke mimics. Up to 30% of patients are misdiagnosed with a stroke and are suffering from a stroke mimic. ACCORDING TO STROKE IN THE ED - RCEMLEARNING ED PROCEDURES • In the ED, the initial priorities are a rapid structured assessment, and exclusion of hypoglycaemia. • One tool developed for use in the ED aimed at improving upon the sensitivity and specificity of the FACE assessment is ‘recognition of stroke in the emergency room’ (ROSIER). RECOGNITION OF STROKE IN THE EMERGENCY ROOM’ (ROSIER) Finding Points Yes -1 Loss of consciousness or syncope No 0 Yes -1 No 0 New, acute onset (or upon awaking from sleep) finding of any of the following: Yes +1 Asymmetric facial weakness No 0 Yes +1 Asymmetric arm weakness No 0 Yes +1 Asymmetric leg weakness No 0 Yes +1 Speech disturbance No 0 Yes +1 Visual field defect No 0 Seizure activity • • A score of 1 or above makes stroke more likely (PPV 90% (CI 85-95%) NPV 88% (CI 83-93%). If the score is negative, another diagnosis should be considered: a stroke mimic. STROKE MIMICS • In one study of consecutive patients thought to have had a stroke and presenting to an urban teaching hospital ED, about 30% actually had a different pathology/diagnosis. • The chart shows the percentage incidence of stroke mimic pathologies. • This study found eight features independently predicted the diagnosis. • The patient with a previous stroke event is particularly difficult to assess. The ability to distinguish true stroke from stroke mimics is an essential skill in the management of stroke patients that cannot be replaced by imaging alone. 20 STROKE MIMICS CLINICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN A STROKE AND THE MIMIC Often associated with an aura: a ‘positive’ symptom. A stroke involves loss of neurological function i.e., ‘negative symptoms’. Migraine Note: Headache is not a feature of ischemic stroke but is often associated with intracerebral hemorrhage. Seizure Seizures may be a complication of an acute stroke or may develop in someone with a history of stroke. However, presentation with a seizure is shown to reduce the odds ratio of the patient having a stroke (OR 0.28) Brain tumor, spaceoccupying lesion or sub dural Usually more gradual onset, though features may be the same. This will be rapidly distinguished on brain imaging Sepsis The patient usually has systemic symptoms of sepsis such as fever. Severe sepsis associated with systemic hypoperfusion may cause watershed area neurological dysfunction Syncope Stroke rarely presents with syncope alone Toxic metabolic states Hyperglycemia and hyponatremia can present with focal neurology. Confusion and slurred speech may be present CN VII nerve palsy A peripheral VIIth cranial nerve palsy is a lower motor neuron lesion, and so the whole of one side of the face is weak. In an upper motor neuron lesion from a stroke (MCA territory), only the lower two-thirds of the face is weak COMMENT: STROKE MIMICS • Stroke mimics can make up to 30% of patients initially diagnosed with a stroke in a teaching hospital. • Consequently, it's not unreasonable to anticipate that we might overlook a few as well. • This holds significance because a suspected stroke patient onboard a vessel requires urgent attention, and considerable resources will be mobilized to transfer the patient to a shoreside facility. • Expending these resources on a patient with potentially reversible conditions like hypoglycemia or intoxications would not be ideal. • Identifying Diseases that Mimic Strokes - JEMS: EMS, Emergency Medical Services - Training, Paramedic, EMT News o A mnemonic to help keep stroke mimics in mind is HEMI: hypoglycemia (and hyperglycemia), epilepsy, multiple sclerosis (and hemiplegic migraine) and intracranial tumors (or infections, such as meningitis, encephalitis and abscesses). • Therefore, be aware of the common mimics and try to exclude them during your history taking, examination and special investigations. 21 INITIAL ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE STROKE – HISTORY STROKE AND TIA HISTORY TAKING | OSCE GUIDE | GEEKY MEDICS HISTORY OF PRESENTING COMPLAINT Due to the nature of Strokes, it can be useful to first ask some simple questions, such as the patient’s age, the month and what they believe your job role to be. This can enable you to quickly establish: • if the patient is orientated • if the patient is able to understand you • if you are able to understand the patient A collateral history is often very valuable in the context of suspected stroke or TIA, particularly when the patient is unable to communicate effectively. • Onset o The time at which the patient’s symptoms developed is very important as this helps to both differentiate between a TIA and stroke as well as informing management options (e.g., thrombolysis window). o Establish the onset time of the patient’s symptoms: ▪ “When did you first notice the symptom(s)?” ▪ “How long have the symptom(s) been present?” o If a patient has woken up with symptoms (but had none before going to sleep) the onset time is assumed to be when they went to sleep. o Make sure to ask the patient if they got up in the night for any reason (e.g., toilet) and if they noticed symptoms at that time, as this may make the difference between whether they are within the thrombolysis window or not. • Severity o Explore the severity of the patient’s symptoms: ▪ Weakness: subtle (e.g., clumsy hand), moderate or complete paralysis. ▪ Sensory disturbance: paresthesia or complete loss of sensation. ▪ Visual disturbance: roughly quantify how much of the visual field is affected. ▪ Expressive dysphasia: clarify if the patient was able to speak at all. ▪ Receptive dysphasia: clarify if the patient is able to understand any communication. ▪ Dysarthria: ask if the patient’s speech was mildly slurred or incomprehensible. • Course o Explore how the patient’s symptoms have evolved since their onset: ▪ “Have the symptoms improved since they first began?” ▪ “When were your symptoms at their worst?” ▪ “Are the symptoms coming and going?” • Precipitating factors o Try to identify if there was an obvious trigger for the symptoms: ▪ “What were you doing at the time that the symptoms developed?” • Associated features. o Ask about other associated symptoms including: ▪ Headache, nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness: associated with raised intracranial pressure (e.g., malignant middle cerebral artery syndrome), subarachnoid hemorrhage and bacterial meningitis. ▪ Unilateral headache: suggestive of migraine which can present with neurological symptoms that mimic stroke (e.g., hemiplegic migraine). ▪ Fevers: may indicate infective etiology such as septic emboli in infective endocarditis 22 Nausea, vomiting and dizziness: associated with posterior circulation strokes. Palpitations: associated with atrial fibrillation which may be the underlying embolic source. Previous episodes o Ask if the patient has experienced similar symptoms previously: ▪ “Have you ever experienced anything like this before?” ▪ “How many times have you experienced these symptoms?” ▪ “How long did they take to resolve previously?” ▪ “When was the last episode?” o Patients presenting with a stroke may have experienced TIAs in the preceding days, weeks or months. Dominant hand o Ask the patient what their dominant hand is: ▪ “What’s your dominant hand?” ▪ It is useful to know this prior to performing clinical examination. ▪ ▪ • • STROKE SYMPTOMS Once you have completed exploring the history of presenting complaint, you need to move on to more focused questioning relating to the symptoms associated with stroke and TIA. • • • • Weakness o Ask the patient if they have noticed any weakness: ▪ “Have you noticed any new weakness?” o Gather more details about the weakness: ▪ Distribution of the weakness (e.g., right arm, leg and face) ▪ Severity of the weakness (e.g., subtle, struggling with holding a cup, completely flaccid) ▪ Onset and duration of the weakness ▪ Course of the weakness (i.e., improving, fluctuating, worsening) Sensory disturbance o Ask the patient if they have noticed any changes in sensation: ▪ “Have you noticed any changes in the sensation of your arms, legs or face?” o Gather more details about the sensory disturbance: ▪ Distribution of the sensory disturbance ▪ Severity of the sensory disturbance (e.g., completely numb, tingling, feeling slightly different) ▪ Onset and duration of the sensory disturbance Visual disturbance o Ask the patient if they have noticed any changes to their vision: ▪ “Have you noticed any recent changes to your vision?” o Gather more details about the visual disturbance: ▪ Type of visual disturbance (e.g. vertigo, hemianopia, quadrantanopia, amaurosis fugax) ▪ Severity of the visual disturbance (e.g., blurred vision, complete loss of vision) ▪ Onset and duration of the visual disturbance Ataxia o Ask the patient if they have noticed any problems with their balance or coordination: ▪ “Have you noticed any difficulties with balancing or problems with coordinating the movement of your arms or legs?” 23 Gather more details about the ataxia including: ▪ Impact on the patient’s ability to walk and use their limbs to carry out tasks. ▪ Presence of associated symptoms suggestive of a posterior circulation stroke (e.g., vertigo, nausea). Speech disturbance o Ask the patient if they have noticed any changes to their speech: ▪ “Have you noticed any changes to your speech, such as slurring, problems getting your words out or issues understanding others?” o Clarify the type of speech disturbance: ▪ Expressive dysphasia: “I knew what I wanted to say, but I couldn’t get it out.” ▪ Receptive dysphasia: “I wasn’t able to understand anyone, they were speaking gibberish.” ▪ Dysarthria: “My speech was really slurred, it sounded like I was drunk” Dysphagia o Ask the patient if they have noticed any dysphagia: ▪ “Have you experienced any difficulties when trying to swallow food or liquids?” o Gather more details about the dysphagia including: ▪ Solid foods: “Are you able to manage solid foods?” “Does it feel like they get stuck in your gullet?” ▪ Liquids: “Do you struggle to drink liquids?” “Do you find yourself coughing after drinking liquids?” o Dysphagia is common in stroke and if not recognized early it can lead to aspiration pneumonia and choking episodes. Reduced level of consciousness o If a collateral history is possible ask about the patient’s reduced level of consciousness: ▪ “When did the patient begin to become more drowsy?” o Gather more details about the reduced level of consciousness including: ▪ History of head trauma ▪ Associated symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting and jerking movements. Pain o Ask the patient if they have any pain: ▪ “Do you have any pain at the moment?” o Explore the pain further using the SOCRATES acronym. o • • • • STROKE/TIA RISK FACTORS When taking a stroke/TIA history it’s essential that you identify stroke and TIA risk factors (e.g., past medical history, family history, social history). • Important stroke/TIA risk factors include: o Ischemic heart disease o Hypercoagulable disease (e.g., sickle o Hypertension cell anemia, polycythemia vera) o Atrial fibrillation o Prosthetic heart valves o Hypercholesterolemia o Carotid stenosis o Diabetes o Poor ventricular function o Previous stroke or TIA o Migraine with aura o Smoking o Combined oral contraceptive pill. o Excessive alcohol intake o Family history of stroke in first-degree relatives 24 PAST MEDICAL HISTORY • Ask if the patient has any medical conditions: o “Do you have any medical conditions?” o “Are you currently seeing a doctor or specialist regularly?” • Allergies o Ask if the patient has any allergies and if so, clarify what kind of reaction they had to the substance (e.g., mild rash vs anaphylaxis). DRUG HISTORY • Ask if the patient is currently taking any prescribed medications or over-the-counter remedies: o “Are you currently taking any prescribed medications or over-the-counter treatments?” FAMILY HISTORY • Ask the patient if there is any family history of stroke or TIA: o “Do any of your parents or siblings have a history of strokes or TIAs?” SOCIAL HISTORY • Explore the patient’s social history to both understand their social context and identify potential cardiovascular/cerebrovascular risk factors. o Smoking o Alcohol o Recreational drug use COMMENT: STROKE ASSESSMENT: HISTORY • Structured history is an important part of not only making a presumptive diagnosis of stroke but can also help identify subtypes and stroke territory. • The use of family members, bystanders and first responder recollection are important to create a picture of the preceding events and hopefully more information regarding past medical history. • It is also not too uncommon to have elderly guests cruising by themselves and not being able to provide any information. • This necessitates contacting their next of kin, especially if they have children. • Sometimes they will also have the contact details of their local family physician who could potentially help by providing further medical information. • TIME OF ONSET: o Establishing the time of ischemic stroke symptom onset is critical because it is the main determinant of eligibility for treatment with intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy. • WAKE-UP STROKE o A wake-up stroke is a stroke that occurs during sleep. In these cases, the person goes to bed feeling normal but wakes up with symptoms of a stroke. o Last-Known-Normal (LKN) or Last-Known-Well time (LKW) is a term used in stroke care to indicate the time the patient was last known to be without the signs and symptoms of the current stroke or at his or her prior baseline. • THERAPEUTIC TIMES TO BE AWARE OFF: o Intravenous thrombolysis improves functional outcome for patients with acute ischemic stroke, provided that treatment is initiated within 4.5 hours of clearly defined symptom onset time or within 4.5 hrs. of the time the patient was last known to be well. o Mechanical thrombectomy is indicated for patients with acute ischemic stroke due to a large artery occlusion in the anterior circulation who can be treated within 24 hours of the time last known to be well (i.e., at neurologic baseline), regardless of whether they receive intravenous thrombolysis for the same ischemic stroke event 25 COMMENT: STROKE ASSESSMENT: HISTORY • Another important aspect of the history is the level of pre-morbid functioning of the patient. • The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) is used in determining eligibility for mechanical thrombectomy but will also be a consideration in determining the nature of the response while the vessel is at sea. • The modified Rankin Scale (mRS), is a 7-level, clinician-reported, measure of global disability. o mRS score 0: A running figure represents the highest, symptom-free functional level. o mRS score1: A walking figure carrying a briefcase represents having symptoms but able to work. o mRS score 2: A figure standing still represents being able to live independently. o mRS score 3: A bent figure with a cane represents more severe impairment causing dependency but not loss of ambulation without assistance on another person. o mRS score 4: A figure using a walker being helped by a caregiver represents loss of ambulation without assistance of another person and/or loss of ability to perform bodily self-care. o mRS score 5: A bedridden figure represents needing continuous care. o mRS score 6: A gravestone represent fatal outcome. Standardized Nomenclature for Modified Rankin Scale Global Disability Outcomes: Consensus Recommendations From Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable XI | Stroke (ahajournals.org) 26 INITIAL ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE STROKE (UPTODATE) THE PHYSICAL EXAMINATION • The physical examination should include careful evaluation of the neck and retroorbital regions for vascular bruits, and palpation of pulses in the neck, arms, and legs to assess for their absence, asymmetry, or irregular rate. • The heart should be auscultated for murmurs. • The lungs should be assessed for abnormal breath sounds, bronchospasm, fluid overload, or stridor. • The skin should be examined for signs of endocarditis, cholesterol emboli, purpura, ecchymoses, or evidence of recent surgery or other invasive procedures, particularly if reliable history is not forthcoming. • The funduscopic examination may be helpful if there are cholesterol emboli or papilledema. • The head should be examined for signs of trauma. • A tongue laceration may suggest a seizure. • In cases where there is a report or suspicion of a fall, the neck should be immobilized until evaluated radiographically for evidence of serious trauma. • Examination of the extremities is important to look for evidence of systemic arterial emboli, distal ischemic, cellulitis, and deep vein thrombosis; the latter should raise the possibility that the patient is receiving anticoagulant treatment. NEUROLOGIC EVALUATION • The neurologic examination should attempt to confirm the findings from the history and provide a quantifiable examination for further assessment over time. • The patient's account of his or her neurologic symptoms and the neurologic signs found on examination talk more about the location of the process in the brain than the particular stroke subtype. • Nevertheless, some constellations of symptoms and signs occasionally suggest a specific process: o Weakness of the face, arm, and leg on one side of the body unaccompanied by sensory, visual, or cognitive abnormalities (pure motor stroke) favors the presence of a thrombotic stroke involving penetrating arteries or a small ICH. o Large focal neurologic deficits that begin abruptly or progress quickly are characteristic of embolism or ICH. o Abnormalities of language suggest anterior circulation disease, as does the presence of motor and sensory signs on the same side of the body. o Vertigo, staggering, diplopia, deafness, crossed symptoms (one side of the face and other side of the body), bilateral motor and/or sensory signs, and hemianopia or bilateral visual field loss suggest involvement of the posterior circulation. o The sudden onset of impaired consciousness in the absence of focal neurologic signs is characteristic of SAH. • Many scales are available that provide a structured, quantifiable neurologic examination. • One of the most widely used and validated scales is the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), composed of 11 items, adding up to a total score of 0 to 42. • Defined cut points for mild, moderate, and severe stroke are not well established, but cut-points of NIHSS score <5 for mild, 5 to 9 for moderate, and ≥10 for severe stroke may be reasonable. 27 COMMENT: STROKE ASSESSMENT: EXAMINATION • The neurological examination of a patient is an important step in the diagnosis of a stroke. • In the initial stages of the assessment, a rapid neurological assessment is needed to confirm whether you are dealing with a stroke. • Below is an excellent example of a rapid neurological examination where time is of the essence: Assessing the stroke patient - YouTube • • • • An example where this rapid assessment would be used in our setting would be the following: o In Port. Husband contacts 115 and states his wife is awake but can’t move her right arm and leg. o Paramedic is contacted and calls the cabin and speaks to the husband to confirms history and goes to scene with emergency response bags, wheelchair and 02. o On arrival ABCDE’s and glucose within normal o Above rapid neurological examination confirms right hemiplegia. o Weakness started 1 ½ hours ago… o You have 3 hours to get her off the vessel, into a local ER, complete the CT scan, assess for contra-indications before she can receive IV Thrombolytics. SO….. o Call duty doctor, advise suspected stoke, confirm weakness in the leg. o Duty doctor should immediately call local shoreside emergency services and start medical disembark (either via Bridge or Port agents depending on local protocols) o Paramedic asks husband to get wallets, passports, travel documents, insurance and all medications and accompany them down to Medical Center. o Transfer to Medical centre in wheelchair. o Medical Team awaiting arrival. ▪ Registration into SeaCare already started. ▪ ICU bed readied • Delegate: Vitals and continuous monitoring • Delegate: IV access and bloods • Delegate: 12 lead ECG • Delegate: Note keeping ▪ Duty doctor takes focused history and repeats rapid examination. o Local emergency medical service arrives 20 minutes later and the patient was transferred to awaiting ambulance with husband. o Patient received IV Thrombolysis 2 ½ hours later with ½ hour to spare. o Luggage offloaded to local hotel. This is simply an example of what we can achieve if we work as a Team, knowing that the patient only has a short window of opportunity. Stroke scenarios should be practiced, similar to Cardiac emergencies. 28 • • • • • • • • By advising the duty doctor early and preparing the medical centre to receive the patient, the Team gave the patient the best opportunity to receive thrombolysis in time. If the vessel is at sea, the rapid neurological assessment is still of value during the initial assessment. However, a more structured and complete neurological assessment is needed when discussing the case for a possible disembarkation. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is commonly used as it is a quantifiable neurologic examination. It is important to become familiar with this Stroke Scale as it will be come a major determinant in the response. Below the link to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke o NIH Stroke Scale | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Training: o NIH Stroke Scale - ACLS Medical Training o Free training program: ▪ https://www.healthcarepoint.com/sign-up-home-page/ ▪ Basic membership ▪ FREE - NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH STROKE SCALE (NIHSS—3.0 CMES/CES) On-line calculators: o NIH Stroke Scale/Score (NIHSS) (mdcalc.com) o NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) - NeurologyToolKit (neurotoolkit.com) 29 INITIAL ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE STROKE IMMEDIATE LABORATORY STUDIES • All patients with suspected stroke should have the following studies urgently as part of the acute stroke evaluation: o Finger stick blood glucose o Oxygen saturation • Other immediate tests for the evaluation include the following: o Electrocardiogram (this should not delay the noncontrast brain CT) o Complete blood count including platelets. o Troponin o Prothrombin time and international normalized ratio (INR) o Activated partial thromboplastin time. o Ecarin clotting time, thrombin time, or appropriate direct factor Xa activity assay if known or suspected that the patient is taking direct thrombin inhibitor or direct factor Xa inhibitor and is otherwise a candidate for intravenous thrombolytic therapy. • The following laboratory studies may be appropriate in selected patients: o Serum electrolytes, urea nitrogen, creatinine o Liver function tests o Toxicology screen o Blood alcohol level o Pregnancy test in women of childbearing potential o Arterial blood gas if hypoxia is suspected. o Chest radiograph if lung disease is suspected o Lumbar puncture if subarachnoid hemorrhage is suspected and head CT scan is negative for blood; note that lumbar puncture will preclude administration of intravenous thrombolysis, though thrombolysis should not be given if there is suspicion for subarachnoid hemorrhage as the cause of the symptoms o Electroencephalogram if seizures are suspected o Chest radiography, urinalysis and blood cultures are indicated if fever is present. We also suggest blood for type and cross match in case fresh frozen plasma is needed to reverse a coagulopathy if ICH is present. • In order to limit medication dosage errors, particularly with the use of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase or tenecteplase, an accurate body weight should be obtained early during the urgent evaluation. CARDIAC STUDIES • Electrocardiography (ECG) is important for detecting signs of concomitant acute cardiac ischemia. • This test is particularly important in the setting of stroke, as patients with ischemic stroke frequently harbor coronary artery disease but may not be able to report chest pain. • Stroke alone can be associated with ECG changes. The sympathetic response to stroke can lead to demand-induced myocardial ischemia. In large strokes, especially subarachnoid hemorrhage, there are centrally mediated changes in the ECG. • The ECG and cardiac monitoring are important for the detection of chronic or intermittent arrhythmias that predispose to embolic events (e.g., atrial fibrillation) and for detecting indirect evidence of atrial/ventricular enlargement that may predispose to thrombus formation. • Current guidelines recommend cardiac monitoring for at least the first 24 hours after the onset of ischemic stroke to look for atrial fibrillation (AF) or atrial flutter. 30 COMMENTS: INVESTIGATIONS • • • • Obviously, we can’t complete all the above recommended imaging or laboratory testing. If in port, the single most important test is the blood glucose. o Do not delay disembarkation to await further results if the patient has obvious signs of a stroke. If at sea, it is important to be more thorough with your investigations as the patient will remain admitted to the Medical Centre until disembarkation. Further investigations are needed to rule out stroke mimics and manage concomitant medical conditions and should include: o Electrocardiogram o Serum electrolytes, urea nitrogen, creatinine o Complete blood count including platelets o Liver function tests o Troponin o Pregnancy test in women of childbearing potential o If indicated: ▪ Arterial blood gas if hypoxia is suspected ▪ Chest radiograph if lung disease is suspected ▪ Toxicology screen ▪ Blood alcohol level CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF STROKE SUBTYPES – UPTODATE DISTINGUISHING STROKE SUBTYPES • Many findings of the history and physical examination suggest certain stroke subtypes. • This presumptive clinical diagnosis requires confirmation by brain and vascular imaging. CLINICAL COURSE OF SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS • The most important historical item for differentiating stroke subtypes is the pace and course of the symptoms and signs and their clearing. • Each subtype has a characteristic course. o Embolic strokes most often occur suddenly. ▪ The deficits indicate focal loss of brain function that is usually maximal at onset. ▪ Rapid recovery also favors embolism. o Thrombosis-related symptoms often fluctuate, varying between normal and abnormal or progressing in a stepwise or stuttering fashion with some periods of improvement. o Penetrating artery occlusions usually cause symptoms that develop during a short period of time, hours or at most a few days, compared with large artery-related brain ischemia, which can evolve over a longer period. o Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) does not improve during the early period; it progresses gradually during minutes or a few hours. o Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage develops in an instant. Focal brain dysfunction is less common. • Patients often do not give a specific history regarding the course of neurologic symptoms. It is useful to ask if the patient could walk, talk, use the phone, use the hand, etc., as the events developed after the first symptoms occurred. 31 COMMENTS: • • • • Although we don’t have CT imaging onboard, it is still possible to make a presumptive diagnosis. Using your knowledge of the various clinical presentations, vascular territories together with the patient’s history and your examination, it is possible to make a presumptive diagnosis. BRAIN HEMORRHAGE o INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE (ICH) o SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE (SAH) ISCHEMIC STROKE o This will be the most common stroke by far. o According to: STROKE CLASSIFICATION | BAMFORD | OXFORD | GEEKY MEDICS o BAMFORD CLASSIFICATION OF ISCHEMIC STROKE ▪ The most commonly used classification system for ischemic stroke is the Bamford classification system (also known as the Oxford classification system). ▪ This system categorizes stroke based on the initial presenting symptoms and clinical signs. ▪ This system does not require imaging to classify the stroke, instead, it is based on clinical findings alone. o TOTAL ANTERIOR CIRCULATION STROKE (TACS) ▪ A total anterior circulation stroke (TACS) is a large cortical stroke affecting the areas of the brain supplied by both the middle and anterior cerebral arteries. ▪ All three of the following need to be present for a diagnosis of a TACS: ▪ Unilateral weakness (and/or sensory deficit) of the face, arm and leg ▪ Homonymous hemianopia ▪ Higher cerebral dysfunction (dysphasia, visuospatial disorder) o PARTIAL ANTERIOR CIRCULATION STROKE (PACS) ▪ A partial anterior circulation stroke (PACS) is a less severe form of TACS, in which only part of the anterior circulation has been compromised. ▪ Two of the following need to be present for a diagnosis of a PACS: ▪ Unilateral weakness (and/or sensory deficit) of the face, arm and leg ▪ Homonymous hemianopia ▪ Higher cerebral dysfunction (dysphasia, visuospatial disorder) * ▪ *Higher cerebral dysfunction alone is also classified as PACS. o POSTERIOR CIRCULATION SYNDROME (POCS) ▪ A posterior circulation syndrome (POCS) involves damage to the area of the brain supplied by the posterior circulation (e.g., cerebellum and brainstem). ▪ One of the following need to be present for a diagnosis of a POCS: ▪ Cranial nerve palsy and a contralateral motor/sensory deficit ▪ Bilateral motor/sensory deficit ▪ Conjugate eye movement disorder (e.g., horizontal gaze palsy) ▪ Cerebellar dysfunction (e.g., vertigo, nystagmus, ataxia) ▪ Isolated homonymous hemianopia o LACUNAR STROKE (LACS) ▪ A lacunar stroke (LACS) is a subcortical stroke that occurs secondary to small vessel disease. There is no loss of higher cerebral functions (e.g., dysphasia). ▪ One of the following needs to be present for a diagnosis of a LACS: ▪ Pure sensory stroke ▪ Pure motor stroke ▪ Sensori-motor stroke ▪ Ataxic hemiparesis 32 LESSONS LEARNED AND PITFALLS • In each CPD module we will discuss LESSONS LEARNED and highlight potential PITFALLS LESSONS LEARNED • An incident involved a guest diagnosed with a stroke while the vessel was at sea. The attending physician made a presumptive diagnosis of an ischemic stroke and administered IV thrombolysis, resulting in significant morbidity. Despite Ischemic strokes being more prevalent, it is imperative to recognize the inability to definitively rule out a hemorrhagic stroke based solely on history and examination. Consequently, the administration of IV thrombolysis should be deferred until the patient is ashore and can undergo CT imaging. • An incident involved a guest diagnosed with a stroke while the vessel was at sea. Although the vessel reached a port, it took an additional 3 hours before the patient underwent medical disembarkation. Given the time-sensitive nature of strokes, every action from the initial 115 call until the patient reaches a local Stroke centre is scrutinized. Even if the 4.5-hour IV thrombolysis window has elapsed, there remains the possibility of the patient being within the 24-hour thrombectomy window. Additionally, if the stroke is hemorrhagic (ICH or SAH), swift surgical intervention could potentially enhance the outcome. Therefore, during the vessel's time in port or upon arrival, time remains a critical factor in decision-making. Every minute the patient stays onboard the vessel without reaching a local facility has the potential to exacerbate the patient's outcome. PITFALLS: • Headaches. This has already been addressed earlier, but it is worth stressing again. Simple benign headaches are common, but you must always consider the signs and symptoms or more serious causes when managing a patient presenting with a headache. o Document pertinent negative findings: ▪ Pain similar to previous headaches ▪ Gradual onset ▪ No neck stiffness ▪ No photophobia ▪ No rash ▪ Not occipital ▪ No history of trauma • Migraines are one of the common stroke mimics. They can present with significant headaches, visual disturbance, nausea, vomiting and even motor weakness. o Generally, migraine tends to come on gradually and feature ‘positive’ symptoms (this means added sensations) such as flashes in vision or tingling. o Strokes tend to feature ‘negative’ symptoms (loss of sensation) such as loss of vision in one eye or loss of feeling in one of your hands. o Patients presenting with migraines normally have a history of previous migraines. o When managing a patient with a concerning headache, have a low threshold to admit and observe the patient. o Always work your way through the Red Flag sign and symptoms, actively excluding each • Lastly, it's crucial to consistently follow up with patients who have presented with headaches. Whether they are seen in the clinic or admitted for observation, a review at the next clinic visits and preferably again the following day is recommended. Conditions like strokes and other serious causes of headaches can exhibit a fluctuating course, with periods of improvement followed by potential worsening. 33 FINAL COMMENT: • • • • • • In this CPD we have reviewed the different types of strokes, their clinical presentations, the vascular territories involved, the early assessment of a stroke patient and ultimately making an early presumptive diagnosis. We have also learned that you cannot diagnose a stroke without imaging capabilities and that is why these patients need to be medically disembarked. TIME is critical. • Time of onset of symptoms, or time last known to be well • IV thrombolysis needs to be administered within 4.5 hours and mechanical thrombectomy can be considered within 24 hours of onset time or LKW time. Below a summary of the important aspects of the initial assessment. • Pre-hospital ▪ FAST stoke signs ▪ Assess at scene ▪ ABCDE + Glucose + GCS ▪ History • Onset of symptoms • Wake up stroke- last known well ▪ Assessment of safe transfer to MC • Medical Center ▪ Prepare for stroke patient “all hands on deck” ▪ Review/repeat ABCDE + Glucose + GCS ▪ ROSIER scale ▪ History • Structured • Onset of symptoms o Wake up stroke- last known well • Modified Rankin score ▪ Examination • Focused neurological examination • Detailed neurological examination • NIHSS score ▪ Special investigations ▪ Rule out Mimics ▪ Presumptive Diagnosis • Ischemic stroke o Bamford classification of ischemic stroke • Hemorrhagic stroke o ICB o SAH The next CPD topic will concentrate on both the management of stroke patients onboard and the subsequent disposition, specifically the medical disembarkation of the patient. Additionally, a companion document dedicated to stroke management will be developed, offering step-by-step considerations for the comprehensive care of stroke patients. WHEN IN DOUBT, ERR ON THE SIDE OF CAUTION 34