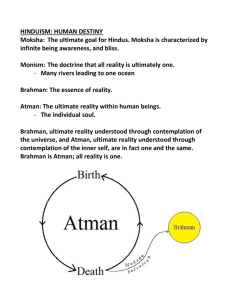

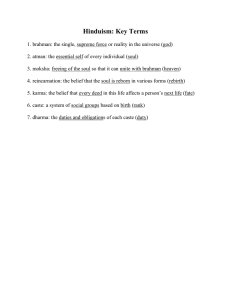

Hindu Schools of Thought The term “Hinduism” refers to religions and philosophies native to India. There are nine Hindu schools of thought, and they are broken into two groups: the astika (orthodox) and the nastika (heterodox). Astika schools believe that the Vedas, ancient Hindu scriptures, are completely valid and infallible, while the nastika schools disagree with at least part of the Vedas. The Vedas conclude with a collection of texts called the Upanishads, which means “to listen to the teacher.” The Nyaya school is astika. Nyaya scholars believe that moksha, which is liberation of the atman (eternal self) from samsara (the cycle of reincarnation), can be brought about through correct knowledge of the material world. Nyaya scholars argue that proper forms of logic will free the atman from consciousness and bring it into an unconscious state called apavarga. The acquisition of false knowledge leads to the accumulation of karma, which loosely translates to “the sum of a person’s actions” (Oxford) and furthers the samsara cycle. Nyaya scholars believe in dharma, or the “eternal and inherent nature of reality” (Oxford), and an ishvara, which is a god-like coordinating force that organizes the universe (Rukmani). They do not believe in the ideas of purusha and prakti, and emphasize the use of logic to attain moksha while not focusing on yoga or meditation. The Vaisheshika school is astika, and its followers believe that moksha is achieved “through a comprehensive analysis of nature” (Sarma, 141), which is similar to the ideas of Nyaya. They also believe in karma, samsara, the atman, dharma, and ishvara. Vaisheshika scholars do not believe in purusha or prakti, and emphasize the use of logic to attain moksha while not focusing on yoga or meditation. The Samkhya school is astika, and focuses on the concepts of purusha (consciousness) and prakti (materiality). Once “the individual properly discerns the duality between purusha and prakti” (Sarma, 167), they will achieve moksha and escape samsara. This school also believes in karma, the atman, and dharma. The school has a history of focusing on meditation and yoga while not placing heavy emphasis on logic. It rejects the concept of ishvara. The Yoga school is astika, and is the only other school that believes in purusha and prakti. Yoga scholars also believe that moksha is achieved through the discernment of purusha and prakti, as well as in the concepts of karma, samsara, the atman, dharma, and ishvara. This school places heavy emphasis on postures and breathing exercises; Yoga scholars argue that the “Eight Limbs” (or eight practices) of Yoga will lead to moksha. This school does not emphasize the use of logic. The Mimasa school is astika, and focuses on the proper interpretation of the Vedas and prioritizes Vedic rituals and meditation over logic and yoga. They believe that moksha is achieved when one lives in perfect harmony with one’s dharma, which this school defines as one’s destiny or purpose. Mimasa scholars also support the ideas of karma, samsara, the atman, and Vedic deities as a form of ishvara; they do not believe in purusha or prakti. The Vedanta school is astika, and argues that moksha is obtained when one is aware of the oneness of the universe and then “exhibits the appropriate bhakti (devotion) and follows the path of prapatti (self-surrender)” (Sarma, 214). This school argues that the atman is not an independent entity, and is rather a facet of the entire universe. Vedanta scholars also support the concepts of karma, samsara, dharma, and ishvara; they reject the concepts of purusha and prakti. Vedanta scholars place heavy emphasis on logic to deduce the oneness of the universe, and do not emphasize meditation or yoga. The Charvaka school is nastika, and believes that matter is the only reality. It rejects the concepts of karma, moksha, samsara, the atman, jiva, anekantavada, ahimsa, nirvana, dukka, and anicca. Charvaka scholars believe that the only reliable source of knowledge is perception, and that inferences are not reliable; smoke does not always mean fire. All proper logic, according to Charvaka, is based on perception. Buddhism is nastika, and Buddhists believe in nirvana, which is a state of enlightenment that liberates one from samsara. Buddhists also support the ideas of karma, dukka (suffering, which is the reason for samsara) and anicca (impermanence). They reject the idea of the atman, as they believe that all things are impermanent and there can be no permanent self. They also do not argue in favor of the jiva, anekantavada, ahimsa, or moksha. They emphasize the use of logic to conclude the impermanent nature of reality and the validity of the Four Noble Truths, and argue that inference and perception are both reliable sources of knowledge. Jainism is nastika, and Jains believe that moksha (or kevala) is achieved by getting rid of karma by following Jain principles. One of these principles is ahimsa, or nonviolence to all living things. Jains believe that all living things are jiva, or omniscient, pure, and sentient beings. When karma accumulates, it clouds the jiva and prevents kevala. Jains also support the ideas of samsara, the atman, anekantavada (the idea that each thing has an infinite number of characteristics due to differing perceptions) and the reliability of inference and perception. Jains reject the ideas of nirvana, dukka, and anicca. Works Cited Rukmani, T S. “God/Isvara in Indian Philosophy.” Encyclopedia.com, Encyclopedia.com, Sept. 2005, https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcriptsand-maps/godisvara-indian-philosophy. Ruzsa, Ferenc. “Sankya.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://iep.utm.edu/sankhya/. Sarma, Deepak. Classical Indian Philosophy: A Reader. Columbia University Press, 2011. "art, n.1." OED Online. Oxford University Press, September 2022. Web. 25 September 2022.