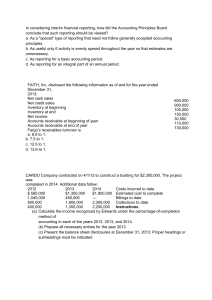

Not-For-Profit Strategy Case Study The Urban Rehab Project This case was prepared for the JDC West 2012 Organizing Committee by The Martello Group. Questions about the case can be sent to info@martellogroup.com. The situation described in this case is based on a real event and key identifying details have been disguised. The JDC West Business Competition holds the copyright for this case and the case cannot be reproduced without express permission from the JDC West Business Competition. To order copies or inquire about permission to reproduce this case, please contact info@jdcwest.com. 1 INTRODUCTION The room fell silent as Alex Molina, newly-appointed CEO of The Urban Rehab Project (the Project) opened the door and took his seat at the table. Sitting in a second room conference floor with windows facing a busy street near Weston and St. Clair, the Project’s four early childhood education specialists looked slightly nervous. “I’m glad you’re able to meet with me given your busy schedule”, said Molina, easing into his introduction, which he had given several times over the past three days. It was Thursday, March 10th, 2011 and Molina had been brought into the Project to revive the not-for-profit organization. “What I’d like to do today is to learn a little bit more about what you do here, and what we can do, in Cabbagetown, to help you.” Cabbagetown was one of the Project’s four locations and its head office. “We’ve had two difficult years and I don’t think we’re out of he woods yet,” Molina added. The four women shifted uneasily in their seats. Molina, sensing that they were afraid he had come to close down the childcare facility, added: We won’t be making any decisions about the organization’s future until I get a chance to hear from all of you. But as you have heard, some changes have to be made to ensure that the Project continues to exist. I can’t make any promises other than to say that we value your commitment and passion for our mission, and we take our people into account when deciding what next to do. Molina asked each specialist to introduce herself and her role in the organization, as a prelude to his presentation and questions. In a few days, Molina would have to look at the entire picture and chart a path forward. For now, he was glad to have the opportunity to continue meeting his new colleagues, and learning more about the organization he had just joined. THE URBAN REHAB PROJECT In 1992, in the midst of a recession, Phillip Kalitsounakis started a youth employment program to help teenagers around Toronto’s Cabbagetown neighborhood – in the Carleton St. and Parliament area - find jobs after high school. The side project, which was taking up Kalitsounakis’s weekends soon morphed into something larger when a wealthy donor, who owned a chain of restaurants in the Danforth area, donated $2 million to help Kalitsounakis start a new not-for-profit organization, The Urban Youth Program. 2 Half of the funds were used to purchase an old building in the Cabbagetown area and hire two full-time employees. Demand for the program, which focused on helping urban youth find meaningful full-time employment, started to grow as connections were made to local colleges and employers. What set the Urban Youth Program apart from other charities and not-for-profit organizations was that it charged a nominal fee ($5 in 1995) to teenagers wanting to participate in its training programs. The rationale behind this, Kalitsounakis explained, was that the payment of a fee – even a small one – increased the odds that participants would be committed to the program. Kalitsounakis, who was a director of health program services in the Ontario provincial government, was a committed advocate of the Urban Youth Program, and he oversaw the expansion of its services into other areas and geographic locations. He used his connections to secure government grants and solicit large donations to bolster programs. By 2000, the Urban Youth Program had been renamed the Urban Rehab Project and was focused on improving life in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Toronto. Kalitsounakis saw that many working families in these neighborhoods spent long hours away from the house and often could not afford childcare costs. In addition, about 60% of the families that were the target group in the Project’s service areas were new immigrants who were employed below their skill level. For example, former high school teachers and engineers were working in construction and as taxi drivers to make ends meet. Last, there was a need for employment-focused programs for youths growing up in these families, who needed assistance with career advice and employment leads. Kalitsounakis was able to raise a total of $12.5 million in donations by 2001, creating an endowment trust, separate from the Project, to hold and disburse the funds. In 2007, Kalitsounakis passed away after a serious medical condition. It was fortunate for Project that he had attracted a few committed individuals to sit on the Project’s Board of Directors, and had left a management team in place. In 2010, the Project operated from four locations, known inside the organization by their neighborhood locations: Cabbagetown; St. Clair-Weston; DavenportOssington; and Woodbine-Danforth. The locations were chosen because they were situated in or near to the most economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Toronto, where the working population mix had a disproportionate number of families living under the poverty line, about $22,000 in income per household. Exhibit 1 provides an overview of Toronto neighborhoods by income and shows 3 the Project’s four locations. Each location had been purchased by endowment funds and was mortgage-free. Depending on the need for services by neighborhood, the Project offered a range of programs including childcare and childhood education, adult education, youth programs, seniors’ programs, employment preparation, and financial literacy. Running these programs was a mix of employees and volunteers, with each location operating autonomously from the others, in keeping with the “local” angle of the organization. The Project’s head office was a series of six offices on the second floor of its Cabbagetown commercial building. It employed 82 people in total, with 71 of them directly involved in program delivery. Its senior management team included a CEO, a CFO, an Operations Manager, and a Director of Human Resources. The Project’s Programs With the mission of building a social improvement network in each neighborhood, the Project’s programs were focused on providing opportunities otherwise unavailable to economically disadvantaged families. Childcare and Childhood Education While it had started out as an initiative to help youth find employment, the Project’s largest program, available in all four locations, was childcare and childhood education. The Project had purchased locations that were often three or four stories high, providing ample space to run a substantial child daycare program in each location. A team of 36 staff in total looked after 110 children in each location per day, and the Project charged parents a fee of between $5 to $7 per child per day, or about a tenth of the cost of an equivalent program delivered by an individual provider or a profit-oriented organization. “When childcare is made affordable,” explained Dewey Sinclair, the Project’s Operations Manager, “parents can take the time to find work and attend school. Our daycare program, in terms of service delivery, is comparable to the higher end daycares in the city because our staff and volunteers are passionate about our cause.” Adult Education The Project’s Adult Education services had counselors and tutors who assisted men and women in obtaining their high school or tertiary degrees. While Adult Education did not deliver any credit courses, its 8 instructors helped individuals 4 with skills such as computer literacy, tutoring (especially for individuals who had English as a second language), and class preparation advice. Youth Programs The core of the Project’s programs, Kalitsounakis’s youth employment program continued to link youth from economically disadvantaged families with local employers. The staff of 11 helped youth learn about potential careers and develop plans to achieve their goals. About half of staff’s time was spent visiting local employers, forging links between the organizations. Seniors’ Programs The Project ran seniors’ programs from three of its four locations. Seniors’ Programs included recreational activities such as walking, targeted at seniors who continued to live in multi-generational households and who could benefit from social interaction with others. Many of these seniors were new immigrants and had not had the time to create a network of friends in their new country. The Project also offered computer literacy and other courses of interest to seniors, such as “Life in Canada”, and “Living a Healthy Life”. Sinclair estimated that over half of the Project’s current group of volunteers was seniors who had first taken a course or participated in a program at the Project. In addition, threequarters of the annual donations (in the $50 to $100 range) and legacy donations ($5,000 and higher) came from the same group of seniors. Employment Preparation The Project had seven specialists who assisted clients who wishing to switch or find jobs. The services included resume advice, interview skills, skills assessment, and academic planning advice. Many of the clients participating in this program were well-trained in their home countries and were looking for ways to get back into their former professions. Financial Literacy In response to demand for financial literacy classes after the economic downturn of 2008-2009, an instructor was hired in the Davenport-Ossington location to run classes on basic financial topics such as budgeting, understanding credit and credit cards, and how banking products worked. The latter part of the course focused on understanding financial investments. 5 LOCATIONS AND PROGRAM DELIVERY The Project’s typical location was a commercial building, located on a busy street, with three or four floors. The buildings had been purchased between 1995 and 2002 during a period of time when real estate prices were at multi-decade lows. Sinclair estimated the value of the various sites in Table 1: Table 1: The Project’s Program Sites – Purchase Price and Value in 2011 Location Cabbagetown St. Clair-Weston Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Purchase Price $1.5 million $2.2 million $1.6 million $2.5 million Value in 2011 $6.0 million $3.9 million $3.7 million $4.3 million In 2010, the four locations had 135,600 “Program Person Days Delivered” (Program Days). Program Days was the Project’s metric to estimate the volume of services it delivered. For example if a child was enrolled in a daycare program for a full year, or 200 days, then that child “consumed” 200 Program Days of services. It was typical for the childcare program to be completely full (and with a waiting list twice the size of the available slots). The other programs varied in duration from one day to 30 days or more. Delivering these programs required combination of staff involvement and volunteer participation. The programs were not designed for full cost-recovery – they were heavily-subsidized by annual donations and, if there were to be any shortfall in revenues, the trustees of the Endowment Fund could elect to cover the difference with a transfer from the Endowment Fund. It was important to note that the Endowment Fund was a separate entity from the Project and the Endowment Fund trustees – who were a combination of two social activists, three civil servants, and three business people – were tasked with managing the Endowment Funds as they saw fit, with the same objective in mind of renewing urban social infrastructure. To be clear, the CEO – or any other executives who worked at the Project, did not have the right to demand that shortfalls had to be covered by withdrawals from the Endowment Fund. The Project had a two-person marketing team in its Support Staff which took charge of eliciting donations. They were a self-managed team and maintained a list of potential donors and “worked” the list throughout the year. There had been 6 a donation brochure developed and sent out in 2008 and 2009 but, due to cost reasons, the brochures were not funded in 2010. The average donation amount had risen from $1,120 in 2008 to $2,102 in 2010. From 2008 to 2010, the number of Program Days had increased 15% per year to 135,600 in 2010, even as fee revenues fell. The Project’s managers had made a decision, during the financial crisis, to forgive some of the fees owed to it from users who were unable to come up with the money. An across the board reduction in fees – by about $2 a program - was implemented at the end of 2009. The decision to lower and forgive fees had a direct impact on the organization’s bottom line. In 2010, the Board of Directors tried to work with the Project’s former CEO to find a way to turn the organization’s financial situation around. The Project’s shrinking revenues prompted the Endowment Fund trustees to approve a total transfer of $2.8 million from the Endowment Fund in 2010. Despite the fact that confidence in the former CEO was eroding rapidly, the Board of Directors was still willing to work with the former CEO to fix the Project’s issues. When it became clear that the former CEO was unable (or unwilling) to make a decision on a new strategy, the Board asked for his resignation. The Board of Directors fired the previous CEO and announced a search for a new CEO. Alex Molina was hired at the start of March 2011. ALEX MOLINA Molina began his career in the not-for-profit sector when he worked for March of Dimes Canada, an organization dedicated to helping rehabilitate people with physical disabilities. After 10 years with the organization, Molina joined the Ontario Ministry of Health, working as a program auditor. It was during this time that he met Kalitsounakis and was introduced to the Project. He sat on the Project’s Board of Directors from 2006 to 2008 until his term was up. Prior to being recruited to the CEO’s post at the Project, Molina was a senior executive at United Way Toronto, a charitable organization. Molina begins work at the Project When he accepted his new post, Molina was well-briefed of the situation he would be walking into. Here was an organization that had grown rapidly and, by all accounts, was having a positive impact on the communities it served. Yet, if it did not find a solution to its current problems, it could be insolvent in a few years. 7 The Project’s Endowment Fund, which stood at $7 million in 2007, was worth just over $3 million at the start of 2011. The funds were kept in cashable investments – money market funds – at the Royal Bank of Canada. On his first day on the job, Molina took a look at the organization chart (see Exhibit 2 and an overview of each location and the services it offered. He was informed that, in the past two years, employee groups in a few locations had joined local union chapters (see Exhibit 3). Molina was told that the reason why the unionization drives had been successful was that these employees had feared for their jobs during the recent recession. He asked for detailed information by program and location, and received a series of tables (seen in Exhibits 4 and 5). These tables outlined the Program Days by program by location, staffing levels, and even revenues and personnel expenses. The last sheet he received was a simplified income and expense statement for the years 2008 to 2010. Molina spent the next three days interviewing staff and volunteers – and even a few clients – at each of the Project’s four locations. He saved the Cabbagetown location as the last facility he would visit. Taking an overall assessment Molina’s interviews gave him a clearer picture of the Project’s operations. It seemed as if each location, operating independently from the others, was doing the best they could to market and deliver the program services each offered. What was happening, however, was that the make-ups of the neighborhoods were changing over the years. For example, the Woodbine and Danforth area was seeing more youth participation in their programs than any other location, due to the increasing numbers of families in the area. Molina discovered that a rising number of Woodbine and Danforth’s youth clientele could be described as coming from lower middle and middle income families, as opposed to the lowincome families the Project wanted to serve. Woodbine and Danforth’s enrollment numbers were expected to be similar in 2011. Similarly, the type of clients at Cabbagetown was changing as well. Enrollment in its youth programs and childcare had fallen by 30% in the last two years. The program manager at Cabbagetown believed that the decrease was temporary and that enrollment would rise again in the future. Sinclair did not concur with the 8 assessment, thinking that overall enrollment at Cabbagetown was going to decline another 10% in 2011. The Davenport and Ossington location had the largest seniors’ program in the organization and was the only centre with a financial literacy program. Overall numbers at Davenport and Ossington were expected to climb 5% in 2011. Of the four locations, St. Clair and Weston was expected to have the greatest increase in enrollment in 2011, rising by 15% due to an unusually high number of new Canadian families in the area. Sinclair believed that there would not be a need to increase in staffing levels at St. Clair and Weston to cope with the higher demand. In fact, Sinclair believed that the utilization rate of each facility could still be improved: Cabbagetown was at 45%; St. Clair-Weston at 80%; DavenportOssington at 75%; and Woodbine-Danforth at 70%. There were no program cutbacks in progress and, at least for the unionized locations, cutbacks would be politically tricky to carry out. Molina referred back to the Project’s mission of “improving life in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Toronto.” It was clear to him that the neighborhoods themselves were changing over time, and that it might be necessary to align the Project’s strategy with it. None of the four locations had a mortgage attached to it, and Molina thought about whether borrowing against the properties – at a mortgage rate of about 4.4% per annum, to cover any shortfall in 2011, made sense. Another option was to kick-start a donations campaign in an effort to bring funds in before the end of 2011. Building up a strong donations campaign required a donations strategy and team, and Molina suspected that it would cost the organization another $200,000 to accomplish this. A strong campaign could, potentially, increase donations per capita by 20-30%, and could increase the number of donors by 20% this year. However, he wondered about the optics of spending money when the organization as a whole was in the red. Molina considered raising the fees charged by a small amount, maybe $3 or $4 per day, in order to boost revenues. He did not want to make a decision on this matter before considering the impact the fee increase would have on the Project’s clientele. “There’s always a struggle to balance “mission” versus “margin”, said the Project’s CFO to Molina, in a conversation on his second day on the job. “It’s a tough decision to make sometimes.” 9 On his tour of the locations, Molina noticed that none of the facilities had been refurbished since they were purchased in the 1990s and the early 2000s. He estimated that $2 million would be to renovate the four locations. A more drastic move – to raise funds - would be to shut down operations at Cabbagetown and sell the facility. This would raise much needed capital to cover at least some of the shortfall in 2011 and invest in facility improvements. If he were to close Cabbagetown – or any other location – he estimated that the Project would incur costs during the shutdown, including severance pay, of roughly one year’s salary for every staff member employed at that location. Instead of closing an entire facility, Molina could recommend a less drastic move, such as reducing the number of programs run at that facility (but still keeping it open and within the Project’s control). But he wondered how to best compare the societal benefits of providing daycare versus adult education versus youth programs or employment preparation. Perhaps there was a way to rank the various programs – from the highest impact to the lowest impact – and cut the less important programs. But, if he were to head in this direction, how should – or could – he select the criteria? Molina makes up his mind Back in the conference room, after each of the four women described the type of work they did and how proud they were to see progress in the children they looked after, Molina held a general question & answer session with them. One of the women spoke up: You mentioned that we’re facing financial pressures and that there is a possibility that some programs may be cut. I’m not an executive, but I wanted you to know I, and many of the Project’s employees, have worked here for more than a few years and we could most definitely be making more money elsewhere. So I wouldn’t want you to think we’re scared for our jobs because of the money. The real reason, and my colleagues will back me up on this, is that we fear for the children – or clients - for whom we care. We’re a lifeline in our communities and we wouldn’t want anyone to forget that. 10 Molina listened intently but said nothing. He had a long few days in front of him to weigh all of the factors and come to a recommendation on how to effect a turnaround at the Project. 11 Exhibit 1 Toronto Poverty by Neighborhood, and The Project’s Locations Woodbine and Danforth Weston and St Clair Davenport and Ossington Cabbagetown Source: www.toronto.ca/demographics/.../pollutionwatch_toronto_fact_sheet 12 Exhibit 2 The Project – Organization Chart Board of Directors URP Endowment Fund CEO Operations Manager CFO Director of Human Resources Support Staff St. Clair-Weston Program Manager Davenport-Ossington Program Manager Cabbagetown Program Manager Woodbine-Danforth Program Manager Childcare and Childhood Education Childcare and Childhood Education Childcare and Childhood Education Childcare and Childhood Education Adult Education Adult Education Seniors’ Programs Adult Education Youth Programs Seniors’ Programs Employment Preparation Youth Programs Employment Preparation Financial Literacy Seniors’ Programs 13 Exhibit 3 The Project – Services by Location Locations Cabbagetown St. Clair-Weston Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Program size Not offered Small Medium Large Unionized Childcare and Childhood Education Adult Education Youth Programs Seniors' Programs Employment Preparation Financial Literacy X X X X X X X X X X Exhibit 4 14 The Project – Services by Location Average daily enrollment by program and location in 2010 Childcare and Adult Childhood Education Education 65 20 Cabbagetown 80 40 St. Clair-Weston 125 X Davenport-Ossington 110 40 Woodbine-Danforth Youth Programs 30 X X 85 Employment Financial Preparation Literacy X X 29 X 4 5 X X Seniors' Programs X 10 25 10 Program Person Days Delivered (Program Days) in 2010 Childcare and Adult Childhood Education Education 13,000 4,000 Cabbagetown 8,000 16,000 St. Clair-Weston X 25,000 Davenport-Ossington 8,000 22,000 Woodbine-Danforth Youth Programs 6,000 X X 17,000 Seniors' Programs X 2,000 5,000 2,000 Employment Financial Preparation Literacy X X 5,800 X 1,000 800 X X Average Daily Number of Volunteers in 2010 Cabbagetown St. Clair-Weston Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Childcare and Childhood Education 0 4 0 4 Adult Education 2 0 X 0 Youth Programs Seniors' Programs Employment Preparation Financial Literacy 0 X X 5 X 5 10 5 X 2 7 X X X 8 X 15 Exhibit 5 The Project – Staff, Revenues and Expenses by Location Number of Full-Time Equivalent Staff in 2010 Cabbagetown St. Clair-Weston Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Cabbagetown St. Clair-Weston Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Childcare and Childhood Education 10 8 10 8 Adult Education 2 3 0 3 Youth Programs 5 0 0 6 Seniors' Programs 0 2 4 2 Employment Preparation 0 5 2 0 Financial Literacy 0 0 1 0 Childcare and Childhood Education 65,000 112,000 150,000 154,000 Program Revenues in 2010 Youth Seniors' Adult Education Programs Programs 20,000 X 36,000 40,000 X 0 X X 0 40,000 102,000 0 Employment Preparation X 0 0 X Financial Literacy X X 8,000 X Program Expenses – Personnel - in 2010 Cabbagetown St. Clair-Weston Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Childcare and Adult Childhood Education Education 450,000 76,000 280,000 114,000 450,000 0 129,000 288,000 Youth Programs 205,000 0 0 210,000 Seniors' Programs 0 62,000 120,000 60,000 Employment Preparation 0 220,000 70,000 0 Financial Literacy 0 0 35,000 0 16 Exhibit 6 The Project – Simplified Statement of Income and Expense Statement For the years ended December 31st Fee revenues Cabbagetown St. Clair-Weston Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Total 2008 251,000 139,000 135,000 256,000 781,000 2009 145,000 151,000 165,000 275,000 736,000 2010 121,000 152,000 158,000 296,000 727,000 Total expenses Cabbagetown St. Clair-Weston Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Total 2008 875,000 875,000 985,000 985,000 3,720,000 2009 1,005,000 985,000 1,100,250 1,120,000 4,210,250 2010 1,462,000 1,352,000 1,350,000 1,374,000 5,538,000 Operating surplus (deficit) Cabbagetown Davenport-Ossington Woodbine-Danforth Total 2008 2009 (624,000) (860,000) (834,000) (736,000) (850,000) (935,250) (729,000) (845,000) (2,939,000) (3,474,250) 2010 (1,341,000) (1,200,000) (1,192,000) (1,078,000) (4,811,000) Total donations, net 2,800,352 2,568,452 1,985,875 138,648 905,798 2,825,125 St. Clair-Weston Funds from Trust 17