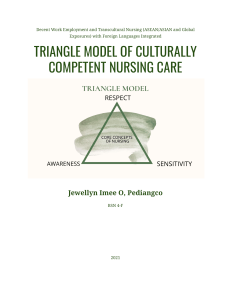

Culturally Competent Health Care: Global Guidelines

advertisement