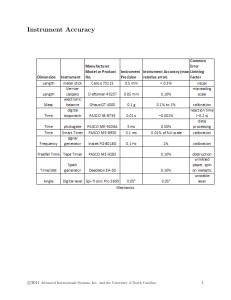

■ POLI CY & LEADERSH I P BY CHRISTOPHER MOERSCH Levels of Technology Implementation (LoTi): A Framework for Measuring Classroom Technology Use Since the introduction of the Apple IIe computer in the early1980s, theterm“technology” hasrepresenteda broadrangeof interestsandhas been the subject of numerous interpretations. In school systems nationwide, technologyhas been the focus of curriculumrenewal projects and school funding debates. It has been the rallying cry for leading many school districts into the 21st century. Our fascination with technologystems, in large degree, fromits ambiguitywithinexistingparadigms. Doestechnologyrepresent things, like computers, modems, pencils, microscopes, andtelevisions; wordsorideas, like “progress” and“change”; processes, like animal breeding andvoting; or deliverysystems, likeexpert systemsandnovicesystems?Eachperspective on technologyhas its unique attributes andleads the individual to different conclusions andimplementation strategies. Attempts in the early 1980s to bring technology into education involved the creation of computer literacy classes at the elementary and secondarylevels. Fromregion to region, these courses were quite similar in their offerings—theytaught studentsabout thepartsof thecomputer, keyboarding fundamentals, wordprocessing, drill-and-practice applications, andintroductoryprogramming. Evenwiththeexponential advances in electronic technology, their legacycan still befoundtodayin theguise of integrated learning systems and central word processing and remediation labs. As one observes the current uses of computer technologynationwide, a fewdistinct patterns emerge. • Staff development opportunities for teachers to explore the potential of computer technologyare oftentimes insufficient andmisdirected. • Most computer technologyisusedfor isolatedactivitiesunrelatedtoa central instructional theme, concept, or topic. • Theuseof thecomputer isoftenonestepremovedfromtheclassroom teacher. 40 Le a rning a nd Le a ding Wit h T e c hnology • Technologyis usedto sustain the existingcurricula rather than serve as a catalyst for change. • The majority of district or site technology plans do not establish a significant link between the need for technology and identifiable instructional priorities(e.g., emphasizinghigherorderthinkingskills or restructuring the science andmathematics curriculum). Instead, theyemphasize a needto meet a vaguelydefinedcomputer/student ratio or establish districtwide local area networks. At best, the role of technology has complemented the conventional instructional curriculumandits corresponding emphasis on expository teaching, traditional verbal activities, sequential instructional materials, andevaluation practicescharacterizedbymultiple-choice, short-answer, andtrue-or-false responses. When planningstaff development targetingclassroomintegration of technology(e.g., spreadsheets, graphing, telecommunications), twofundamental assumptions are often made about the educational practitioners attendingsuch sessions: • Participants are easily able to make connections between the technologytheyhave available andtheir instructional curricula. • Participants are ready and willing to initiate changes in their instructional practices. Oftentimes, neither assumptionisvalid. Thesestaff development sessions often leadto nonuse or lowlevels of use of the technologybyclassroom teachers because the technology-based intervention neither reflects the instructional level of the teacher (Moersch, 1994) nor addresses fundamental self-efficacyissues. Self-efficacytheorysuggests that individuals with a lowlevel of selfefficacywill often choose a level of innovation that theybelieve theycan handle, which mayor maynot be the best or most effective option. Con- November 1995 © 1998, International Society for Technology in Education, 800.336.5191, cust_svc@ccmail.uoregon.edu, www.iste.org. Reprinted with permission. versely, thoseindividualswithhighlevelsof self-efficacyaremost inclined toaccept change andchoose the best option. Olivier andShapiro(1993) identifiedself-efficacyas a major predictor of adoption of innovation. Levels of Technology Implementation We have attemptedto create a conceptual framework that measures levels of technology implementation, or LoTi™, so that we can assist school districts in restructuringtheir staff’s curricula toinclude concept/ process-basedinstruction, authentic uses of technology, andqualitative assessment. LoTi is alignedconceptuallywith the work of Hall, Loucks, Rutherford, andNewlove(1975); ThomasandKnezek(1991); andDwyer, Ringstaff, andSandholtz(1992). In the LoTi framework, we propose seven discrete implementation levels teachers can demonstrate, rangingfromNonuse (Level 0) to Refinement (Level 6). As a teacher progresses fromone level tothe next, a series of changes to the instructional curriculum is observed. The instructional focus shifts from being teacher-centered to being learnercentered. Computer technologyis employedas a tool that supports and extendsstudents’ understandingof thepertinent concepts, processes, and themes involvedwhen using databases, telecommunications, multimedia, spreadsheets, andgraphingapplications. Traditional verbal activities are graduallyreplacedbyauthentic hands-on inquiryrelatedto a problem, issue, or theme. Heavyreliance on textbookandsequential instructional materials is replacedbyuse of extensive anddiversifiedresources determinedbytheproblemareasunderstudy.Traditional evaluationpractices are supplantedbymultiple assessment strategies that utilize portfolios, open-endedquestions, self-analysis, andpeer review.Adetailed description of the LoTi framework is given in the Sidebar on page 42. Implications for District Technology Expansion AsDavidDwyer(1992) hasnoted, “Theuseoftechnologydoesnotguarantee fundamental change in the teaching-learning process and consequentlyin learning outcomes.” Other variables, including organizational leadershipandstructure, theteacher’sroleintherestructuringprocess, and the curriculum itself, impact the entire school restructuring process, includinginstructional usesof technology(Thomas&Knezek, 1991). As school districts prepare their technologyexpansion plans, we offer some basic recommendations based on our work with the LoTi framework. District planningfor technologyshould: • Emphasize staff development because of the incremental andpersonal natureofinnovationadoptions. Existingallocationsforstaffdevelopment are insufficient for districtwide changes in teachers’ instructional curricula tomaximizethecapabilitiesof thenewtechnologies. • Emphasizefront-endanalysisdirectedat linkingproposedtechnology expansion with long-range instructional priorities. • Use technologyto restructure science andmathematics curricula to reflect Benchmarks for Science Literacy andthe NCTMStandards. The abilityfor technologyto cut across curriculumbarriers through the seamless integration of telecommunications, multimedia, and relatedtechnology-basedtoolshelpsdissolveexistingboundariesthat define the existingcurricula (Thomas &Knezek, 1991). © 1998, International Society for Technology in Education, 800.336.5191, cust_svc@ccmail.uoregon.edu, www.iste.org. Reprinted with permission. • Incorporate a variety of measures to justify the money spent on technology from sources such as bond levies, state and federal Eisenhower allocations, and district funds. Such measures might includeLoTi, school dropout rates, student attitudesabout school, test scores, and student achievement in areas seldom assessed by conventional means. Theseareasmightincludecomputeruse, effective communication, social awareness and confidence, independence, problemsolving, andcivic responsibility(Dwyer, 1992). • Include inservice opportunities for site administrators to develop annual technology plans consistent with district priorities for technology implementation and student performance standards. Researchhasdocumentedthat theactionsandinterestsofthebuilding principal have made a significant difference between effective and ineffective implementation of program change (Berman & McLaughlin, 1977; McLaughlin &Marsh, 1978). The LoTi framework is currently being field-tested throughout the UnitedStates. In its current form, the framework can provide a fair approximation of teacher behaviors relatedtotechnologyimplementation. Documenting such behaviors can aidin designing future interventions that support the expandeduse of technologyas well as concept/processbasedinstruction andqualitative assessment practices. ■ [Christopher Moersch, National Business Education Alliance, POBox 61, Corvallis, OR 97339] November 1995 Le a rning a nd Le a ding Wit h T e c hnology 41 References Berman, Paul, &McLaughlin, MilbreyWallin. (1978). Federal programs supporting educational change. Vol. VIII: Implementing and sustaining innovations. Santa Monica, CA:The RandCorporation. Dwyer, DavidC. (1992). Comments for the national education goals panel. Apple Classrooms of Tomorrow. Dwyer, DavidC., Ringstaff, Cathy,&Sandholtz, JudithHaymore. (1992). The evolution of teachers’ instructional beliefs and practices in highaccess-to-technology classrooms, first–fourth year findings. AppleClassrooms of Tomorrow. Hall, Gene E., Loucks, Susan F., Rutherford, William L., & Newlove, Beulah, W.(1975). Levelsof useof theinnovation: Aframeworkfor analyzinginnovation adoption. Journal of Teacher Education, 26(1), 52–56. McLaughlin, MilbreyWallin, &Marsh, DavidD. (1978). Staff development andschool change. Teachers College Record, 80(1), 69–93. Moersch, Christopher. (1994). Labs for learning: An experientialbased action model. National Business Education Alliance. Olivier, TerryA., &Shapiro, Faye. (1993). Self-efficacyandcomputers. Journal of Computer-Based Instruction, 20(3), 81–85. Thomas, LajeaneG., &Knezek, Don. (1991). Facilitatingrestructured learning experiences with technology. The Computing Teacher, 18(6), 49–53. The LoTi Framework 42 Level Category Description 0 Nonuse Aperceivedlackof access to technology-basedtools or a lackof time to pursue electronic technology implementation. Existingtechnologyispredominatelytext-based(e.g., dittosheets, chalkboard, overheadprojector). 1 Awareness The use of computers is generallyone stepremovedfromthe classroomteacher (e.g., integrated learningsystemlabs, special computer-basedpullout programs, computer literacyclasses, central wordprocessinglabs). Computer-basedapplications have little or no relevance to the individual teacher’s instructional program. 2 Exploration Technology-basedtools serve as a supplement to existinginstructional program(e.g., tutorials, educational games, simulations). The electronic technologyis employedeither as extension activities or as enrichment exercises to the instructional program. 3 Infusion Technology-basedtools, includingdatabases, spreadsheets, graphingpackages, probes, calculators, multimediaapplications, desktoppublishingapplications, andtelecommunicationsapplications, augment isolatedinstructional events (e.g., a science-kit experiment usingspreadsheets/graphs to analyze results or a telecommunications activityinvolvingdata-sharingamongschools). 4 Integration Technology-basedtools are integratedin a manner that provides a rich context for students’ understandingof the pertinent concepts, themes, andprocesses. Technology(e.g., multimedia, telecommunications, databases, spreadsheets, wordprocessors) is perceivedas a tool to identifyandsolve authentic problems relatingto an overall theme/concept. 5 Expansion Technologyaccess is extendedbeyondthe classroom. Classroomteachers activelyelicit technology applicationsandnetworkingfrombusinessenterprises, governmental agencies(e.g., contactingNASA to establish a linkto an orbitingspace shuttle via the Internet), research institutions, anduniversities to expandstudent experiences directedat problemsolving, issues resolution, andstudent activismsurroundinga major theme/concept. 6 Refinement Technologyis perceivedas a process, product (e.g., invention, patent, newsoftware design), andtool to helpstudents solve authentic problems relatedto an identifiedreal-worldproblemor issue. Technology, inthiscontext, providesa seamlessmediumfor informationqueries, problemsolving, and/or product development. Students have readyaccess to anda complete understandingof a vast arrayof technology-basedtools. Le a rning a nd Le a ding Wit h T e c hnology November 1995 © 1998, International Society for Technology in Education, 800.336.5191, cust_svc@ccmail.uoregon.edu, www.iste.org. Reprinted with permission.