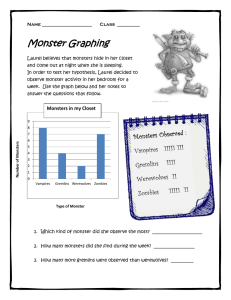

TOOLS AND GUIDES TO BUILD, CUSTOMIZE, AND RUN FANTASTIC MONSTERS IN YOUR 5E FANTASY GAMES ´ • SCOTT FITZGERALD GRAY • MICHAEL E. SHEA TEOS ABADIA by Teos Abadía, Scott Fitzgerald Gray, and Michael E. Shea Design by Teos Abadía, Scott Fitzgerald Gray, and Michael E. Shea Mechanical Development by Teos Abadía and Michael E. Shea Editing by Scott Fitzgerald Gray Proofreading by Marcie Wood, Christine J. Cabalo, Aaron Houillon Cultural Consulting by James Mendez Hodes Front and Back Cover Art by Jack Kaiser Interior Art by Zoe Badini, Allie Briggs, Nikki Dawes, Carlos Eulefí, Jack Kaiser, Víctor Leza, Matt Morrow, Jackie Musto, Fabian Parente, Brian Patterson, Danny Pavlov Logo and Page Design by Rich Lescouflair Layout by Scott Fitzgerald Gray Thanks to our Kickstarter backers for supporting this project! Copyright © 2023 by Teos Abadía, Scott Fitzgerald Gray, and Michael E. Shea Art copyright © 2022–2023 by the individual artists This work includes material taken from the System Reference Document 5.1 (“SRD 5.1”) by Wizards of the Coast LLC and available at https://dnd.wizards.com/resources/systems-reference-document. The SRD 5.1 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. Dungeons & Dragons, D&D, Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master’s Guide, and Monster Manual are registered trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC ISBN 979-8-9859421-3-2 Printed in Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS MONSTER TOOLKITS Building a Quick Monster............................................4 Monsters and the Tiers of Play................................ 74 General-Use Combat Stat Blocks........................... 13 Building Engaging Encounters............................... 76 Monster Powers............................................................ 15 Building Engaging Environments.......................... 79 Monster Roles............................................................... 22 Assessing a Published Encounter.......................... 83 Monster Difficulty Dials............................................. 27 Building Challenging High-Level Encounters................................................................ 86 Building and Running Legendary Monsters.............................................. 28 Building and Running Boss Monsters.................. 31 Building Spellcasting Monsters.............................. 34 Creating Lair Actions.................................................. 36 MONSTER TIPS AND TRICKS On Encounters per Day............................................. 93 MONSTER DISCUSSION AND PHILOSOPHY The History of Challenge.......................................... 97 Lazy Tricks for Running Monsters.......................... 38 What Are Challenge Ratings?.................................. 99 Running Monsters for New Gamemasters........................................................... 40 What Makes a Great Monster?..............................100 Understanding the Action Economy.................... 42 Defining Challenge Level........................................105 Lightning Rods............................................................. 44 Balancing Mechanics and Story...........................109 Modifying Monsters Before and During Play................................................................ 45 Building the Story to Fit the Monster.................110 Running Monsters in the Theater of the Mind............................................... 47 Romancing Monsters...............................................115 Reading the Monster Stat Block...........................102 Choosing Monsters Based on the Story............113 Roleplaying Monsters................................................ 48 There Be Monsters.....................................................117 Reskinning Monsters.................................................. 50 Anticolonial Play........................................................119 The Relative Weakness of High-CR Monsters................................................... 53 Running Easy Monsters...........................................124 Running Minions and Hordes................................. 54 Running Spellcasting Monsters.............................. 58 Using NPC Stat Blocks................................................ 60 Bosses and Minions.................................................... 61 Evolving Monsters....................................................... 62 BUILDING ENCOUNTERS The Combat Encounter Checklist.......................... 65 Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge........................................................ 67 The Lazy Encounter Benchmark............................. 70 Monsters by Adventure Location.......................... 72 2 Exit Strategies............................................................... 91 On Morale and Running Away..............................125 DIFFERENT PATHS This book has been crafted and shaped as a collaboration between Teos, Scott, and Mike, with each acting as lead on specific sections that all three of us then workshopped and refined over more than a year of design and development. This creative partnership approach means that Forge of Foes generally doesn’t offer only single viewpoints. Rather, you’ll find a range of choices in these pages—different paths you can take as you conceptualize, create, modify, and run monsters in your games. In the many places in the book where two approaches offer different advice on the same issue, that’s a feature, not a bug. Think about and try out whichever approaches appeal to you, determine which ones work well for you and your group, and set aside those that don’t. INTRODUCTION Thousands of years before anyone ever rolled a twentysided die, monsters fueled people’s imaginations and filled us with tales of high adventure. Nearly every culture known to humanity has its own stories of creatures fantastic and horrifying, and of the heroes who face them. We love monsters. We love them because they exist outside our world and yet feel real to us. We love how strange they can be. We love the sense of danger that arises when we talk about them. We love how they live in our imaginations. And when monsters come to life in our imaginations, we love to face and defeat them. We battle dragons and demons and undead—and conquer them in tales we’ll remember all our lives. Within the Forge of Foes, we build these monsters. Here in the forge, we’ll modify creatures, giving them new attacks and strange new abilities. We’ll harden their scales and sharpen their claws. We’ll create entirely new creatures from our boundless collective imagination, then watch them crawl into the stories of high adventure we share with our friends. We’ll also talk about monsters, including how to run boss monsters, how to run hordes of monsters, and how to choose the right monsters for our adventures and for the fun of our gaming groups. Let us delve into deep caves, beneath rotted and forgotten crypts, and into unholy temple chambers sweet with the iron scent of blood to see what monsters lie within. WHAT IS A FOE? Within the context of this book, a foe is any physically hostile creature. It might be a statue ready to magically animate where it guards an undiscovered tomb. It might be a knight challenging the characters to a duel. It might be cultists seeking victims for a terrible ritual. It might be the dragon of the frozen mountains, newly awakened and now seeking the treasures acquired by neighboring miners. Not all foes are monsters, however, and we need to take care while throwing around that label lest we apply it to those undeserving of the title. Many beings and creatures commonly labeled as “monsters” can ultimately be dealt with through negotiation, even as many normal-looking NPCs might be secret—or not-so-secret—monsters in their own lives. The cultists cited above might not be monsters at all in their own minds, but only a secluded sect pushed to usher in a new age of enlightenment. That awakened dragon might have been driven to violence by suffering—with the characters potentially asked to help solve the dragon’s woes. Forge of Foes often uses the words “foe,” “creature,” and “monster” synonymously. But it does so with the understanding that there might be many ways to deal with these foes outside of straight-up combat, and that some apparent monsters might be anything but. ABOUT THIS BOOK Created by Teos Abadía, Scott Fitzgerald Gray, and Mike Shea (see “About the Authors” on page 128), this book isn’t a typical collection of foes. There are already many wonderful books of predesigned monsters that Gamemasters can use for D&D and other fifth edition fantasy roleplaying games. Instead, this book gives GMs the tools to build their own foes and modify foes from other sources. Forge of Foes works alongside your other books of 5e monsters, but it also works well on its own to help you make the monsters you need for your games. Though part of the Lazy Dungeon Master series, this book stands on its own. Forge of Foes focuses on monsters—how to make them, how to modify them, and how to run them. The concepts presented here work with those found in Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master, The Lazy DM’s Workbook, and The Lazy DM’s Companion, but you don’t need those books to get value out of this one. Like the other books from the Lazy Dungeon Master series, this book aims to help you more easily run great games. You’re busy. You have friends coming to your table tonight. You have monsters you need to throw into your game right now. Forge of Foes can help you build or modify those monsters quickly and easily, with all the details, tactics, and flavor you desire. WHO IS THIS BOOK FOR? This book assumes you’re familiar with the core rules of Dungeons & Dragons or another 5e RPG. You don’t need significant experience running 5e games to make use of this book. But the more experience you have, the more value you’ll get out of it. This book isn’t a substitute for reading any set of 5e core books, however. Take the time to read and absorb the material found in those books to get the most use out of this book and improve your games. HOW TO USE THIS BOOK This book can serve you in three ways. First, you can use Forge of Foes to quickly build monsters from scratch, and to make those monsters as simple or as complex as you want. Starting with baseline statistics, you can add on templates and features to fill out a monster’s mechanics as you desire, and as best fits the story of the monster. Second, you can use the statistics, templates, and features in this book to modify existing monsters. Doing so can provide you with endless variants of monsters from products you already own. Third, you can absorb the advice and discussions in this book to think differently about how you prepare and run monsters in your own games. So whether you run monsters straight from your favorite monster book, customize published monsters yourself, or build monsters from scratch, Forge of Foes has you covered. 3 BUILDING A QUICK MONSTER Sometimes you need a monster right now but you don’t have the right one handy. Maybe the creature you’re imagining doesn’t exist in any given book of published monsters, or you simply don’t have the time to look it up. Maybe you’re in the middle of your game and want some quick statistics for a creature you didn’t think you’d need. For all these problems, this section offers solutions. The core tool for building a quick monster for a 5e game is the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table on page 6, which offers you a set of statistics that can be used to build and run a quick monster of any challenge rating (CR). You then have two paths for customizing a monster built from these baseline statistics—with flavor and description during the game, or with a refinement of the creature’s mechanics. It’s worth your time to review and understand how this table works before you start using it in your game. Read the column descriptions. Understand the relationship between a monster’s challenge rating and equivalent character level. Once you’ve internalized how this table works, you can use it in seconds to build a monster and throw that foe into your game. This table works hand-in-hand with Forge of Foes’ options for building encounters, including “Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” (page 67) and “Building Challenging High-Level Encounters” (page 86). It also works alongside further customization options, such as the monster type templates and powers presented later in this section, and the additional powers in “Monster Powers” (page 15) and “Monster Roles” (page 22), letting you make your chosen creature more tactically interesting or a better fit for their place in the story and the game. COLUMN DESCRIPTIONS The table includes the following columns, which will become more familiar to you as you build your monsters. Monster CR. The challenge ratings presented in the CR column are the baseline measure to determine the relative difficulty of a monster in combat. You’ll almost always reference this column first when building a quick monster. Equivalent Character Level. This column describes the roughly equivalent level of a single character facing a single monster of this challenge rating in a hard encounter. This gives you a quick way to determine how difficult this monster will be when facing characters of a particular level. As you can see from the table, matching character level to challenge rating isn’t a simple mathematical process. There are a number of character levels missing from the table where certain challenge ratings represent a large jump in how tough a monster is. AC/DC. This column indicates the typical Armor Class of a monster of the indicated challenge rating. It also 4 describes the typical Difficulty Class if this monster uses a DC for any of their attacks or other features. Hit Points. This column offers the baseline hit points of a monster of a given challenge rating. Feel free to add or subtract hit points within the suggested range based on the monster’s in-world features or physiology, or the pacing you want to maintain during a battle. Proficient Ability Bonus. This column gives the expected bonus for abilities with which the monster is proficient, adding the monster’s ability score modifier and proficiency bonus together. This number can be used as an attack bonus, or as a bonus for proficient saving throws and ability checks. (Ability-based modifiers without proficiency are fixed values between −2 and +4, based on the monster’s story.) Damage per Round. This column contains the total expected damage that a monster can deal in a round. Higher-CR monsters typically split this total damage among a number of attacks, instead of doing one big attack that either deals a tremendous amount of damage or misses completely. If a single effect targets two or more characters, such as a fiery breath weapon, the damage for that effect should be half the indicated number. Number of Attacks. This column notes the number of attacks a monster of a particular challenge rating typically makes per round. The damage per round from the previous column is divided among these multiple attacks in the following column. Damage per Attack. This column shows the baseline amount of damage a monster deals per attack when using the default number of attacks in the previous column. It includes both average damage and a dice equation. Example Monsters. This column offers example monsters for each challenge rating. This can help you gauge where your monster fits among a sampling of existing 5e monsters. BUILDING A MONSTER With the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table at hand, you can use the following quick steps to build a custom monster from scratch. The first four steps alone let you easily create a monster ready to run in your game. The optional steps that follow then let you fill out the monster’s details and custom mechanics as desired. STEP 1: DETERMINE CHALLENGE RATING Begin by determining the challenge rating for your quick monster based on that creature’s fiction in the world. When considering the challenge rating of a custom monster, you might compare them to existing creatures on the table. If the in-world power of your monster compares well to a skeleton, the monster might have a challenge rating of 1/4. If they’re more like a fire giant, they might have a challenge rating of 9. Look at the list of example monsters and ask yourself which monster makes the best comparison to yours. Then assign your creature that monster’s challenge rating. ALTERNATIVELY, WHAT CHALLENGE RATING DO YOU NEED? You might also want to choose a challenge rating based on the level of the characters, using the Equivalent Character Level column of the table. If you want an encounter with four monsters who are roughly equal in power to four characters, this column lets you figure out those monsters’ statistics. It also helps you build NPCs—knights, mages, thieves, and so forth—intended to be a match for characters of a particular level. STEP 2: WRITE DOWN THE BASELINE STATISTICS Once you’ve determined a challenge rating for your monster, write down their statistics. You might jot them on an index card, in a text editor on your computer, or wherever you keep notes for your adventures and campaigns. You might end up customizing those statistics, though, so be ready to change them. STEP 3: DETERMINE PROFICIENT ABILITIES Next, determine which abilities—Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Intelligence, Wisdom, or Charisma—a monster is proficient in, using the Proficient Ability Bonus column on the table. This sets up the bonus a monster has when using any ability with which they’re proficient, and is largely based on the monster’s story. A big, beefy monster might be proficient in skills or saving throws involving Strength and Constitution. A mastermind monster might be proficient in Wisdom- and Intelligencebased skills and saving throws. A fast monster might be proficient in Dexterity (Acrobatics) checks and Dexterity saving throws, while an otherworldly monster might be proficient in Charisma-based skills and saves. The bonus indicated in the table is what the monster uses to make saving throws and ability checks with those proficient abilities. Just remember that the number on the table already includes a monster’s proficiency bonus, in addition to their ability score modifier. STEP 4: DETERMINE REMAINING ABILITIES Next, you can determine the modifier (either a penalty or a bonus) that a monster uses for their nonproficient abilities. This is for all the ability checks and saving throws a monster isn’t great at, and can be determined by asking yourself how strong a monster feels in those abilities. The bonus can range anywhere from −2 to +4, and is independent of a monster’s challenge rating. Even a high-challenge monster might have a lousy Dexterity saving throw. When in doubt, or to speed things up, use a modifier of +0 for these nonproficient abilities. You can always change this during the game if a higher or lower number makes sense. A creature’s Dexterity modifier is also used to determine their initiative modifier. Or you can skip your improvised creature’s initiative roll and use a static initiative of 12. YOU’RE READY TO GO At this point, you have enough information on hand to run your monster in a game, with little else needed. However, you can also continue with a few more quick steps to further customize your monster, making them more distinct. OPTIONAL STEP: CONSIDER ARMOR CLASS Though the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table offers a value for Armor Class that increases with challenge rating, you can modify a monster’s Armor Class further based on their story. A big beefy titan set up as a CR 16 monster might still be easy to hit—maybe with an Armor Class of 14. It’s easiest to think of Armor Class on a scale of 10 to 20, with 10 being the equivalent of an unarmored opponent with no Dexterity bonus, and 20 being an opponent wearing plate armor with a shield. (Armor Class can go above 20 or below 10, though.) Keep in mind that missing an opponent isn’t much fun for a player. Lower-AC opponents, even those with more hit points, are often more fun to fight than high-AC opponents with fewer hit points. OPTIONAL STEP: CUSTOMIZE ATTACKS The table includes a recommended number of attacks for a monster, an attack bonus, and the amount of damage those attacks should deal. If desired, tailor this damage to fit the monster’s story. Choose a creature’s damage type, such as fire for a flaming Greatsword attack, or necrotic for a Death Blast attack. You can also mix up multiple damage types, so that a CR 10 hell knight might have a Longsword attack dealing both slashing and fire damage. Consider the ranged attacks a monster might have as well. You can use the same attack bonus, number of attacks, and damage. Or you could give a creature weaker ranged attacks (attacking once instead of twice, for example). Depending on the creature’s story, the flavor of those attacks might be physical (hurling javelins or rocks) or arcane (firing energy blasts). To further customize a monster, you can divide up their total damage per round into a different number of attacks than indicated on the table, if that makes sense for the monster’s story. (As noted above, for attacks that target two or more opponents, use half the indicated damage.) OPTIONAL STEP: FURTHER MODIFY STATISTICS Depending on the story of your monster, you can make general adjustments to their baseline statistics however you see fit. For example, you might lower a monster’s hit points and increase the damage they deal to create a dangerous foe who drops out of the fight quickly. 5 MONSTER STATISTICS BY CHALLENGE RATING CR Equivalent Character Level AC/ DC Hit Points Proficient Ability Damage Bonus per Round Damage per Attack Example 5e Monsters 0 <1 10 3 (2–4) +2 2 1 2 (1d4) Commoner, rat, spider 1/8 <1 11 9 (7–11) +3 3 1 4 (1d6 + 1) Bandit, cultist, giant rat 1/4 1 11 13 (10–16) +3 5 1 5 (1d6 + 2) Acolyte, skeleton, wolf 1/2 2 12 22 (17–28) +4 8 2 4 (1d4 + 2) Black bear, scout, shadow 1 3 12 33 (25–41) +5 12 2 6 (1d8 + 2) Dire wolf, specter, spy 2 5 13 45 (34–56) +5 17 2 9 (2d6 + 2) Ghast, ogre, priest 3 7 13 65 (49–81) +5 23 2 12 (2d8 + 3) Knight, mummy, werewolf 4 9 14 84 (64–106) +6 28 2 14 (3d8 + 1) Ettin, ghost 5 10 15 95 (71–119) +7 35 3 12 (3d6 + 2) Elemental, gladiator, vampire spawn 6 11 15 112 (84–140) +7 41 3 14 (3d6 + 4) Mage, medusa, wyvern 7 12 15 130 (98–162) +7 47 3 16 (3d8 + 3) Stone giant, young black dragon 8 13 15 136 (102–170) +7 53 3 18 (3d10 + 2) Assassin, frost giant 9 15 16 145 (109–181) +8 59 3 22 (3d12 + 3) Bone devil, fire giant, young blue dragon 10 16 17 155 (116–194) +9 65 4 16 (3d8 + 3) Stone golem, young red dragon 11 17 17 165 (124–206) +9 71 4 18 (3d10 + 2) Djinni, efreeti, horned devil 12 18 17 175 (131–219) +9 77 4 19 (3d10 + 3) Archmage, erinyes 13 19 18 184 (138–230) +10 83 4 21 (4d8 + 3) Adult white dragon, storm giant, vampire 14 20 19 196 (147–245) +11 89 4 22 (4d10) 15 > 20 19 210 (158–263) +11 95 5 19 (3d10 + 3) Adult green dragon, mummy lord, purple worm 16 > 20 19 229 (172–286) +11 101 5 21 (4d8 + 3) Adult blue dragon, iron golem, marilith 17 > 20 20 246 (185–308) +12 107 5 22 (3d12 + 3) Adult red dragon 18 > 20 21 266 (200–333) +13 113 5 23 (4d10 + 1) Demilich 19 > 20 21 285 (214–356) +13 119 5 24 (4d10 + 2) Balor 20 > 20 21 300 (225–375) +13 132 5 26 (4d12) Ancient white dragon, pit fiend 21 > 20 22 325 (244–406) +14 150 5 30 (4d12 + 4) Ancient black dragon, lich, solar 22 > 20 23 350 (263–438) +15 168 5 34 (4d12 + 8) Ancient green dragon 23 > 20 23 375 (281–469) +15 186 5 37 (6d10 + 4) Ancient blue dragon, kraken 24 > 20 23 400 (300–500) +15 204 5 41 (6d10 + 8) Ancient red dragon 25 > 20 24 430 (323–538) +16 222 5 44 (6d10 + 11) 26 > 20 25 460 (345–575) +17 240 5 48 (6d10 + 15) 27 > 20 25 490 (368–613) +17 258 5 52 (6d10 + 19) 28 > 20 25 540 (405–675) +17 276 5 55 (6d10 + 22) 29 > 20 26 600 (450–750) +18 294 5 59 (6d10 + 26) 30 > 20 27 666 (500–833) +19 312 5 62 (6d10 + 29) Tarrasque However, always consider whether such changes make a combat encounter more fun to play. It might make sense to create a monster with high hit points and a higher Armor Class who deals less damage, thinking that those two things balance out. But fighting such a monster can easily become a slog. Likewise, a monster with significantly fewer hit points that deals high damage might end up being inadvertently deadly if too many characters roll low on attacks, or could feel pointless if the monster is killed too quickly. OPTIONAL STEP: ADD QUICK TYPES AND FEATURES 6 Number of Attacks The “Common Monster Type Templates” section on the following page includes a number of monster types you can apply when creating a quick monster. Each monster Adult black dragon, ice devil type includes the most important features of that type, whether corporeal undead, elemental, fiend, and so forth. That section also includes a number of useful monster powers you can add to a foe, or you can select from additional features, traits, and attacks in “Monster Powers” (page 15) and “Monster Roles” (page 22). USING THE TABLE WITH PUBLISHED MONSTERS While the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table is intended to let you build monsters from scratch, it can easily be used as a reference to better understand how a published monster might act in combat. If a published CR 4 monster has 30 hit points but deals 35 damage per round, you can see from the table that their hit points are low but their damage is high compared to the creature’s baseline challenge rating. Such a monster hits hard for their challenge rating, but when they’re hit in turn, they go down fast. COMMON MONSTER TYPE TEMPLATES This section offers a sampling of monster type templates whose traits you can apply to your quick-build monster, new powers tied to specific monster types (including actions, bonus actions, reactions, and additional traits), and advice on how to use those powers. Some templates use the challenge rating of the creature you’re creating to calculate saving throw DCs, damage, and other variables. You can find additional monster type templates and guidance for using them in “Monster Powers” on page 15, and still more templates and powers in “Monster Roles” on page 22. ABERRATION Aberrations generally have high Intelligence, Wisdom, and Charisma scores, as well as darkvision with either a 60- or 120-foot range. An aberration speaks a language such as Deep Speech, or communicates telepathically. Senses darkvision 120 ft. Languages Deep Speech, telepathy 120 ft. You can further represent an aberration’s nature by giving them any of the following powers. Grasping Tentacles (Reaction). When this creature hits with an attack, they sprout a tentacle that grasps the target. In addition to the attack’s normal effects, the target is grappled (escape DC = 11 + 1/2 CR) and restrained. Until the grapple ends, this creature can’t use the grappling tentacle against another target. This creature can sprout 1d4 tentacles. This reaction is a fun way to surprise your players. Describe how the tentacles emerge from the foe’s limb or body to grasp a character. You can roll for the number of tentacles or choose a number that reflects the creature’s desired challenge rating. BRIAN PATTERSON Dominating Gaze (Action, Recharge 4–6). If this creature has the Multiattack action, Dominating Gaze can take the place of one of the attacks used in that action. This creature chooses a target they can see within 60 feet of them. The target must succeed on a Charisma saving throw (DC = 12 + 1/2 CR) or be forced to immediately use their most effective weapon attack, magical attack, or at-will spell against another target chosen by this creature. This action communicates the foe’s otherworldly nature. The momentary domination could come in the form of mind control, changing what the target sees, or confusing them. Describing horrid whispers of the beauty of the stars waking to devour the world is optional. BEAST Beasts might have low ability scores if they are mundane creatures, with their strongest scores in either Strength or Dexterity. They might also have medium to high Constitution or Wisdom to represent hardiness and cunning. Beasts typically have darkvision with a 60-foot range, and they don’t speak a language. Beasts often have the ability to climb, swim, or fly, and they might be proficient in the Athletics, Perception, or Survival skills. You can customize a quick-build beast using one of the powers below, or a power from the “Monstrosity” section. Hit and Run (Action). As part of this action, this creature first takes one of their other actions. After that action is completed, this creature can move 30 feet without provoking opportunity attacks. If the creature ends their movement behind cover or in an obscured area, they can make a Dexterity (Stealth) check to hide. This action allows a beast to act as a predator, attacking and repositioning themself for maximum effect. Empowered by Carnage (Reaction). When this creature hits another creature with a melee attack and the damage from the attack either reduces the target to below half their hit point maximum or reduces them to 0 hit points, this creature can immediately move up to their speed and repeat the melee attack against another target. This reaction captures the ferocious nature of the beast, motivated by seeing prey take a grievous wound or meet their end. CELESTIAL As divine beings of the Outer Planes, celestials have high ability scores. Charisma is usually especially high to represent a celestial’s leadership qualities, eloquence, and beauty. Celestials often have resistance to radiant damage. They might also have resistance to damage from nonmagical attacks, and immunity to the charmed and frightened conditions, and to exhaustion. The mightiest 7 celestials possess truesight with a range of 120 feet, speak and understand all languages, and communicate telepathically. Damage Resistances radiant; bludgeoning, piercing, and slashing from nonmagical attacks Condition Immunities charmed, exhaustion, frightened Senses darkvision 120 ft. Languages all, telepathy 120 ft. You can also select one or both of the powers below to further enhance a creature’s celestial nature. Winged (Trait). This creature has a flying speed equal to their best speed, and can hover. Glorious celestial wings might be shaped of feathers, ice, or radiant energy. You can increase the flying speed if you wish the celestial to have more mobility. Mirrored Judgment (Reaction). When this creature is the sole target of an attack or spell, they can choose another valid target to also be targeted by the attack or spell. A celestial might change their face or armor to become reflective like a mirror, so that an attacking creature can contemplate their actions. CONSTRUCT A construct’s strongest ability scores are usually Strength and Constitution, though a construct built for agility might also have a high Dexterity. Constructs typically also have either blindsight or darkvision, and a selection of damage immunities and condition immunities to reflect their nonliving nature. They usually can’t speak, but might understand one or more languages. Damage Immunities poison, psychic Condition Immunities blinded, charmed, deafened, exhaustion, frightened, paralyzed, petrified, poisoned Senses blindsight 60 ft. (blind beyond this radius) or darkvision 60 ft. Languages understands certain languages but can’t speak You can further enhance a construct with one of the following features. Armor Plating (Trait). This creature has a +2 bonus to Armor Class. Each time the creature’s hit points are reduced by one-quarter of their maximum, this bonus decreases by 1, to a maximum penalty to Armor Class of −2. The high Armor Class of a construct might feel initially frustrating, but as you describe the pieces of armor plating being torn off, players will sense the tide turning. When the bonus to Armor Class becomes a penalty, describe how the rents in the armor allow characters access to the construct’s inner workings, speeding up the foe’s demise! Sentinel (Trait). This creature can make opportunity attacks without using a reaction. 8 This simple feature really shines when you describe the construct’s sharp eyes zeroing in on the characters, or how the construct swivels part of their body to make an opportunity attack. DRAGON Draconic creatures have high Strength, Dexterity, and Constitution scores, as well as high Charisma scores. A dragon has immunity to any damage type used for their breath weapon, has blindsight and darkvision, and speaks Draconic. They often have proficiency in Perception, and in one or more other skills reflecting their interests or nature. Damage Immunities damage type associated with the dragon’s breath weapon Senses blindsight 60 ft., darkvision 120 ft. Languages Common, Draconic A true dragon or a closely related draconic creature has a breath weapon that is fearsome to behold. You can adjust the damage or area of effect depending on how powerful your draconic creature is meant to be. Dragon’s Breath (Action, Recharge 5–6). This creature breathes to deal poison, cold, or fire damage in a 30-foot cone, or breathes to deal acid or lightning damage in a 60-foot line that is 5 feet wide. Each creature in the area of the exhalation must make a Dexterity saving throw against a line or a Constitution saving throw against a cone (DC = 12 + 1/2 CR), taking 4 × CR damage of the appropriate type on a failed save, or half as much damage on a successful one. You might also wish to provide a dragon or draconic creature with an additional power to reflect their nature. Dragon’s Gaze (Bonus Action, Recharge 6). One creature within 60 feet of the dragon must make a Wisdom saving throw (DC = 13 + 1/2 CR) or become frightened of the dragon. While frightened in this way, each time the target takes damage, they take an extra 1/2 CR damage. The target can repeat the saving throw at the end of each of their turns, ending the effect on themself on a success. Dragon’s Gaze puts the pressure on a character, and goes well with threats a dragon makes as they promise that the heroes are about to meet their doom. Draconic Retaliation (Trait). When this creature is reduced to half their hit points or fewer, they can immediately use either their breath weapon or their Multiattack action. If the creature is incapacitated or otherwise unable to use this trait, they can use it when they are next able to. This trait showcases a dragon’s might and fury, just as the characters appear to gain the upper hand. For a particularly fearsome foe—or particularly strong characters—you can use this trait again when the dragon is reduced to one quarter of their hit points or fewer. ELEMENTAL Elementals generally have strong physical ability scores. They have resistance to damage of the type they are associated with (acid, bludgeoning, cold, fire, lightning, or thunder), and might have immunity to that damage if wholly created from elemental energy. An elemental usually has immunity to poison damage and certain conditions, depending on their nature. They have darkvision and speak the language associated with their element. Damage Resistances damage type the creature is associated with, if appropriate; bludgeoning, piercing, and slashing from nonmagical attacks Damage Immunities damage type the creature is associated with, if appropriate; poison Condition Immunities exhaustion, grappled, paralyzed, petrified, poisoned, prone, restrained, unconscious Senses darkvision 60 ft. An elemental can be further enhanced with one of the following features. Elemental Attacks (Trait). This creature’s weapons or limbs are infused with energy of the type they are associated with (acid, bludgeoning, cold, fire, lightning, or thunder), dealing that damage type instead of their normal type. Senses darkvision 60 ft. Languages Common, Elvish, Sylvan A fey creature can be further enhanced with one of the following features. Teleporting Step (Bonus Action). This creature teleports a number of feet up to their walking speed to an unoccupied space they can see. This option makes a fey creature a master of mobility, which you can richly describe in a number of ways. Does the creature summon, then step through portals? Vanish into shadow? Move from one plant to another? Transform into wind and appear in another location? Beguiling Aura (Trait). An enemy of this creature who moves within 25 feet of them for the first time on a turn or starts their turn there must succeed on a Wisdom saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) or be charmed by this creature until the end of their turn. Representing the enigmatic and compelling nature of many fey, this aura can force a character to change their tactics during their turn. It’s especially effective on a foe you wish to protect, making it harder for melee characters to engage that foe, and incentivizing those characters to pick other targets first. You can vary the nature of the charm effect, whether the fey is adorned in the finest clothing, can change their appearance to look like a friend, or weaves ancient words to beguile their enemies. FIEND This is a basic feature to communicate the nature of an elemental monster. Reinforce this through roleplaying, describing the foe’s form and appearance. Are they a being of fire? Are they wielding weapons that they ignite with fire? Ability scores for fiends favor their physical characteristics, though many also have moderate or higher Charisma scores. Devils hoping to entice mortals into deals also often have proficiency in the Deception skill. Fiends typically have resistance to nonmagical attacks, and might have one or more elemental resistances. Demons speak Abyssal, while devils speak Infernal. Both usually have telepathy up to 120 feet. Elemental Aura (Trait). This creature radiates an aura of elemental energy of the type they are associated with (acid, bludgeoning, cold, fire, lightning, or thunder). Any creature who moves within 10 feet of this creature for the first time on a turn or starts their turn there takes 5 damage of the selected energy type (10 damage if this creature is CR 12 or higher). Damage Resistances elemental resistances; bludgeoning, piercing, and slashing from nonmagical attacks Damage Immunities poison Condition Immunities poisoned Senses darkvision 120 ft. Languages Abyssal or Infernal, telepathy 120 ft. Does your elemental monster radiate extreme cold? Do sparks fly from them, or does a cloud of stones encircle them? An elemental aura communicates a creature’s nature clearly, and presents a tactical challenge for meleefocused characters. For an alternative approach, have this trait activate only when the creature drops below half their hit points, as their elemental essence leaks out of their body. BRIAN PATTERSON Sylvan or Elvish in addition to Common, and many speak Giant. Most fey have darkvision, and proficiency in the Deception, Perception, or Persuasion skills. FEY Fey creatures can vary greatly in their traits and actions, but often have high Charisma and Dexterity scores and moderate-to-high Wisdom scores. Fey usually speak In addition, you can add any of the following features to enhance the fiendish capabilities of a foe. Empowered by Death (Trait). When a creature within 30 feet of this creature dies, this creature regains 2 × CR hit points. What makes this feature interesting is that the foe’s allies dying also triggers it. Give this trait to a fiendish boss so that they can gain hit points as their minions die. They might even kill one off just for fun. Relish Your Failure (Trait). When a creature within 50 feet of this creature fails a saving throw, this creature gains 1/2 CR temporary hit points. If this creature already has temporary 9 hit points, they instead regain 1/2 CR hit points, up to their hit point maximum. The fiend calls out any character’s failure, mocking them and drawing strength from their inadequacy. This trait works best for foes who have actions or spells requiring saving throws. GIANT Giants have Strength and Constitution scores as formidable as their size, but their Dexterity scores are typically lower. Some giants speak only Giant, while others might speak Common, Goblin, or other languages. Forceful Blow (Reaction, Recharge 4–6). When this creature hits a target with a weapon attack, roll 1d4 + 1. The target is pushed 5 times that many feet away from this creature. You can alter the size of the die to reflect the type of giant, or assign a fixed value for the distance if you feel that would work better. Sending characters flying is rewarding. Try not to enjoy it too much. Shove Allies (Action). This creature can shove any allied creatures who are within 5 feet of this creature and are smaller in size. Each shoved ally moves up to 15 feet away from this creature, and can make a melee weapon attack if they end that movement and have a viable target within their reach. Roleplay the giant as they shove smaller creatures around them, forcing them to fight for their lives. Players might enjoy the tactical nature of this approach, since defeating enough of the giant’s smaller allies makes this trait less effective. HUMANOID Ability scores for humanoids can reflect both their role and their ancestry. The wide variety of humanoid types and the range of standard NPC stat blocks that can represent humanoids makes it difficult to create templates for specifically humanoid features. Instead, you can select from the powers found in the “Common Monster Powers” section on the next page, choosing those that enable your specific concept. MONSTROSITY Monstrosities often have high Constitution and either high Strength or Dexterity. Their Intelligence and Charisma are often low. Many monstrosities lack a language, and they might have skill proficiency in Athletics, Perception, or Stealth. A burrowing, climbing, or swimming speed might be appropriate. The following powers can be used to show off a truly monstrous monstrosity. For monstrosities such as centaurs and doppelgangers who are decidedly less monstrous in their appearance and outlook, you can use the powers in “Common Monster Powers” instead. Devour Ally (Bonus Action). This creature swallows an allied creature who is within 5 feet of this creature and is smaller. This creature regains 3 × CR hit points and the devoured ally is reduced to 0 hit points. 10 This power works well for a massive monstrosity paired with smaller, weaker creatures who they can slay at will—or even swallow whole. This forces the characters to choose between focusing on the larger foe or killing off the weaker ones to prevent the boss from healing. Lingering Wound (Reaction, Recharge 6). When this creature hits a target with an attack and deals damage, the target takes a lingering wound. At the start of each of their turns, a target with a lingering wound takes the same damage dealt by the original attack. The target can attempt a DC 10 Constitution saving throw at the end of each of their turns, ending the effect on themself on a success. A successful DC 10 Wisdom (Medicine) check made as an action by the target or a creature within 5 feet of them also ends the target’s lingering wound. The effect of this power can be described as blood loss from jagged fangs or claws, heightening a monstrosity’s terrible nature. OOZE Oozes almost always have low mental ability scores, and they often have either low Strength or Dexterity scores based on their nature. Oozes might be proficient in the Stealth skill if they sneak up on opponents, or if they have transparent bodies or forms that blend into their environment. Oozes typically lack a language, and rely on blindsense to sense creatures in close proximity. They often have immunity to multiple conditions. Condition Immunities blinded, charmed, deafened, exhaustion, frightened, prone Senses blindsight 60 ft. (blind beyond this radius) Many oozes have the ability to slip through small openings, which can be represented by the following trait. Malleable Form (Trait). This creature has advantage on checks to begin or escape a grapple, and can move through a space as if they were two sizes smaller than their size without squeezing. You can alter the malleable trait to reflect just how small a space an ooze creature can move through, with some oozes able to move through a space as small as 1 inch wide without squeezing. Additionally, you can choose any of the following powers to represent a creature’s ooze nature. Oozing Passage (Trait). This creature can move through the space of other creatures of their size or smaller without provoking opportunity attacks. When they do so, each creature whose space this creature moves through must succeed on a Strength saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) or be restrained until the end of their next turn. It can be fun to describe the moment when an ooze passes over and around a character. This can be a strong feature if the ooze moves through several characters, so you might alter tactics as needed to reflect the desired challenge rating. You can also remove the restrained effect to simply provide an interesting form of mobility. Elongating Limbs (Trait). This creature can increase the length of their limbs or other appendages at will, increasing their reach by 5 feet. A creature moving out of this creature’s reach or within their reach provokes an opportunity attack. This trait is the surprise that keeps surprising. A monster can lengthen a limb to attack a character, then use it later for a reaction attack. Describe the way the limb elongates in as grotesque a way as desired. PLANT Plant creatures have extremely low mental attributes and low Dexterity scores. Many are stationary, or might have a slow walking speed of anywhere from 5 to 20 feet. Some plant creatures have darkvision, while others have blindsight out to a range of 30 or 60 feet. Some have resistance to bludgeoning and piercing damage, or resistance to cold, fire, or poison damage. Some have immunity to conditions such as blinded, deafened, and prone, and to exhaustion. A few plants have vulnerability to fire. You can add any of the following powers to a creature with a plantlike nature. Poison Thorns (Bonus Action, Recharge 5–6). The next time this creature hits a target with an attack and deals damage, the attack deals extra poison damage equal to half the damage originally dealt, and the target gains the poisoned condition until the end of their next turn. You can describe the thorns growing along the plant creature’s appendages when they take this bonus action. Those thorns might be a bold color such as bright red or blue, and could drip poison. Grasping Roots (Trait). When a creature attempts to leave a space within 5 feet of this creature, the moving creature must succeed on a Strength saving throw (DC = 12 + 1/2 CR) or be restrained until the start of their next turn. You can surprise players with this power, which reveals itself as a network of roots surrounding the plant, hidden beneath the soil or spreading along the cracks of a stone floor. When a character attempts to move away from or around the plant, the roots emerge and try to hold them fast. UNDEAD Undead creatures typically have immunity to poison damage and the poisoned condition, and they do not need to eat or breathe. Some undead have immunity to the charmed condition and to exhaustion, and skeletal undead might have vulnerability to bludgeoning damage. Although some intelligent undead can speak, many undead lack the ability to speak even if they can understand language. Damage Immunities poison Condition Immunities exhaustion, poisoned Senses darkvision 60 ft. Languages understands all languages they knew in life but can’t speak You can also add any of the following powers to an undead creature. Undead Resilience (Trait). If damage reduces this creature to 0 hit points, they must make a Constitution saving throw with a DC of 2 + the damage taken, unless the damage is radiant or from a critical hit. On a success, this creature drops to 1 hit point instead. Add this trait to undead creatures who can withstand blows that would kill a living creature. Describe a successful save as the undead creature getting back up or refusing to fall, despite missing body parts or other terrible wounds. Stench of Death (Trait). Any creature who starts their turn within 10 feet of this creature must succeed on a Constitution saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) or become poisoned until the start of their next turn. On a successful saving throw, the targeted creature is immune to this creature’s stench for 24 hours. You can alter the effect’s radius based on the … uh, flavor you wish to impart. COMMON MONSTER POWERS This section offers a selection of common monster powers you can apply to any quick-build monster to give them a stronger mechanical flavor, make them more tactically interesting, or reinforce their behavior in the story of your game. Damaging Aura (Trait). Any creature who moves within 10 feet of this creature or who starts their turn there takes CR damage of a type appropriate for this creature. Reskin this aura to meet your needs based on the damage type. A fire elemental can radiate an aura of fire, while an undead might radiate necrotic damage. You can also describe this effect as a magical aura dealing force damage or a holy aura dealing radiant damage, or even have a many-armed creature wielding swords to create an aura of slashing damage. Damaging Weapon (Trait). This creature’s melee weapon attacks deal an extra CR damage of a type appropriate for the creature. As with Damaging Aura, this trait can be customized for many types of creatures by choosing a thematic damage type. A warrior might wield a greatsword that deals extra fire or lightning damage as a boon bestowed by their god. A mini-boss undead could deal necrotic or cold damage to represent their innate supernatural power. Defender (Reaction). When an ally within 5 feet of this creature is targeted by an attack or spell, this creature can make themself the intended target of the attack. This is an excellent feature for minions who can intercept damage intended for a boss, or for a highhit-point monster who can act as a defender of more strategically important monsters. Delights in Suffering (Trait). When attacking a target whose current hit points are below half their hit point maximum, this creature has advantage on attack rolls and deals an extra CR damage when they hit. This trait makes a monster extremely dangerous in a tough fight, and encourages the characters to use healing resources. Frenzy (Trait). At the start of their turn, this creature can gain advantage on all melee weapon attack rolls made during this turn, but attack rolls against them have advantage until the start of their next turn. 11 In addition to providing a combat boost for a foe, this trait can help accelerate a fight that’s gone on long enough, by letting the characters hit the last remaining foes more often. Goes Down Fighting (Reaction). When this creature is reduced to 0 hit points, they can immediately make one melee or ranged weapon attack before they fall unconscious. Your monsters can get one last attack in when they have this trait. Improvised Ranged Attack (Action). This creature can make one or more ranged weapon attacks—firing a bow or crossbow, hurling a spear or javelin, throwing rocks, and so forth. These attacks have an attack modifier and damage appropriate for the creature’s challenge rating (see the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table), and a range of 45/90 feet or as appropriate to the weapon. With this attack, any melee combatant becomes an effective threat at range. Arcane Blast (Action). This creature can make one or more ranged spell attacks, dealing acid, cold, fire, force, lightning, necrotic, poison, psychic, or radiant damage as appropriate to the creature. These attacks have an attack modifier and damage appropriate for the creature’s challenge rating (see the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table), and a range of 60 or 120 feet. This attack lets you add a touch of arcane fury to any combatant. Lethal (Trait). This creature has a +CR bonus to damage rolls, and scores a critical hit on an unmodified attack roll of 18–20. This simple trait is a default you can use to increase the damage dealt by any monster. Mark the Target (Trait, Recharge 3–6). When this creature hits a target with a ranged attack, allies of this creature who can see the target have advantage on attack rolls against the target until the start of this creature’s next turn. Let a monster apply pressure to a specific target with this power, especially if that target is wounded or in a vulnerable position. Make the foe’s action obvious, so that the players know to react to it and can help the targeted character survive the ensuing focused fire. Not Dead Yet (Trait, 1/Day). When this creature is reduced to 0 hit points, they drop prone and are indistinguishable from a dead creature. At the start of their next turn, this creature stands up without using any movement and has 2 × CR hit points. They can then take their turn normally. This trait can represent a clever combatant playing dead, a warrior with incredible resolve, or a creature such as an undead or an ooze who refuses to die. Parry and Riposte (Reaction, Recharge 6). This creature adds +3 to their Armor Class against one melee attack that would hit them. If the attack misses, this creature can immediately make a weapon attack against the creature making the parried attack. This power works well for clever foes, especially those who are experts in the use of the weapons they wield. 12 Quick Recovery (Trait). At the start of this creature’s turn, they can attempt a saving throw against any effect on them that can be ended by a successful saving throw. This power can protect vulnerable combatants and bosses from being shut down by spells. It can represent magical mastery, divine favor, luck, or a specific quality of the creature. As a variant, using this trait could require the foe to take 2 × CR damage if the new saving throw is successful, representing the exertion made to overcome the effect. Refuse to Surrender (Trait). When this creature’s current hit points are below half their hit point maximum, the creature deals CR extra damage with each of their attacks. This trait works best when given to a single important foe, and when you describe the monster’s refusal to surrender despite their many wounds. This lets the players know they can focus fire to finish the creature off, minimizing their damage potential. Reposition (Bonus Action, 1/Day). Each ally within 60 feet of this creature who can see and hear them can immediately move their speed without provoking opportunity attacks. Place this trait on a boss monster to allow their minions to quickly reposition, especially when it’s useful for those minions to move through characters ready to attack. Sneaky (Trait). This creature has advantage on Dexterity (Stealth) checks. Foes fighting in obscured areas or behind cover can benefit from this trait, which can represent natural camouflage or well-practiced skill. Spell Fuel (Reaction). When a target this creature can see (including themself) either succeeds or fails on a saving throw against a spell or other magical effect, this creature can expend a spell slot to force the target to reroll the saving throw. Appropriate for a powerful spellcaster, this power represents mastery over magical forces in its ability to enhance or weaken a spell’s effect. Telekinetic Grasp (Action). This creature chooses one creature they can see within 100 feet of them weighing less than 400 pounds. The target must succeed on a Strength saving throw (DC = 11 + 1/2 CR) or be pulled up to 80 feet directly toward this creature. When characters like to hang back from the action, this power can draw them right into the heart of combat. It can represent psionic ability, a spell, or mastery over wind and air. You can also adjust the power to be a teleportation effect if that fits a monster’s concept. Vanish (Bonus Action). This creature can use the Disengage action, then can use the Hide action if they have cover (no action required). Creatures accustomed to fighting from cover gain a formidable edge with this power. Consider pairing Vanish with the Sneaky trait (above) to create an unstoppable ambusher. GENERAL-USE COMBAT STAT BLOCKS This section contains several general-use stat blocks specifically built for reskinning into whatever monsters you need for your combat encounters. Each is fully usable on its own, but you can improvise adjustments to them during play, or customize them with attacks and traits from “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), or “Monster Roles” (page 22). Each stat block uses d8 Hit Dice, but can be used for creatures in a range of sizes. Each focuses on a primary ability score, but you can shift abilities as needed to better fit the story of the creature the stat block represents. Swap Strength and Intelligence to run a spellcaster instead of a melee combatant, or switch Dexterity and Strength to turn a shifty rogue into a powerful fighter. A stat block’s attack lets you choose the most appropriate type of damage for a creature, and you can easily increase an attack’s reach or range. Ranges for attacks are given as a single number indicating maximum range, but you can modify that range or replace it with the normal and long range of a specific weapon as you wish. The spread of challenge ratings of these stat blocks provides options for weak, moderate, and strong foes at any character level. Each stat block description includes comparisons between the stat block and characters of different levels, providing guidelines for when a stat block can serve as a boss, an elite foe (suitable for two characters against one creature), or a one-on-one combatant, or in larger groups of two to four monsters per character. All these setups are geared toward a hard encounter (see “Defining Challenge Level” on page 105), but one that the characters should definitely be able to win. MINION (CR 1/8) The low-CR minions represented by this stat block might include ravenous rats, weak skeletons, shifty bandits, or low-ranking cultists. A minion can serve as a one-on-one combatant against 1st-level characters, or can be deployed in large groups at 4th level or above. This stat block focuses on Dexterity as its primary ability. MINION Armor Class 11 Hit Points 9 (2d8) Speed 30 ft. DEX 12 (+1) Representing seasoned guards, trained soldiers, powerful bandits, murderous humanoids, or armed undead, the soldier stat block works well as a boss at 1st level, an elite foe for two 2nd-level characters, or one-on-one combatants at 4th level, or in large groups at 6th level and above. Strength is this stat block’s primary ability. SOLDIER Medium Creature Armor Class 12 (leather armor or natural armor) Hit Points 22 (4d8 + 4) Speed 30 ft. STR 14 (+2) DEX 12 (+1) CON 12 (+1) INT 10 (+0) Senses passive Perception 10 Challenge 1/2 (100 XP) WIS 10 (+0) CHA 10 (+0) Proficiency Bonus +2 ACTIONS Attack. Melee or Ranged Weapon Attack: +4 to hit, reach 5 ft. or range 60 ft., one target. Hit: 8 (1d12 + 2) damage. BRUTE (CR 2) Heavy-hitting veterans, capable bodyguards, low-ranking demons or devils, dangerous monsters in the wild, and powerful humanoids can all be represented by this stat block. A brute can serve as a boss against 2nd-level characters, an elite foe against two 4th-level characters, or a one-on-one opponent at 5th level, or in large groups at 10th level. This stat block relies on Strength. BRUTE Medium or Large Creature Armor Class 13 (studded leather or natural armor) Hit Points 45 (7d8 + 14) Speed 30 ft. STR 16 (+3) DEX 12 (+1) CON 14 (+2) Saving Throws Con +4 Skills Athletics +5 Senses passive Perception 10 Challenge 2 (450 XP) Small or Medium Creature STR 10 (+0) SOLDIER (CR 1/2) INT 10 (+0) WIS 10 (+0) CHA 8 (−1) Proficiency Bonus +2 Actions CON 10 (+0) Senses passive Perception 11 Challenge 1/8 (25 XP) INT 10 (+0) WIS 12 (+1) CHA 10 (+0) Multiattack. The brute makes two attacks. Attack. Melee or Ranged Weapon Attack: +5 to hit, reach 5 ft. or range 60 ft., one target. Hit: 9 (1d12 + 3) damage. Proficiency Bonus +2 Actions Attack. Melee or Ranged Weapon Attack: +3 to hit, reach 5 ft. or range 60 ft., one target. Hit: 4 (1d6 + 1) damage. 13 SPECIALIST (CR 4) SENTINEL (CR 11) This stat block can represent spies, assassins, hunters, and trained elite forces. The specialist serves as a boss for 4th-level characters, an elite opponent versus two 5th-level characters, or a one-on-one combatant for 10th-level characters, or in large groups against 16th-level characters. Dexterity is this stat block’s primary ability. This stat block is a good fit for strong, often-otherworldly creatures such as demons, devils, impressive beings of the Outer Planes, guardian constructs, or powerful undead. The sentinel can serve as a boss for 7th-level characters, an elite foe against two 12th-level characters, or can stand one-on-one against 16th-level characters. This stat block focuses on Strength. SPECIALIST SENTINEL Medium Creature Medium, Large, or Huge Creature Armor Class 14 Hit Points 84 (13d8 + 26) Speed 30 ft. STR 12 (+1) DEX 18 (+4) CON 14 (+2) INT 10 (+0) WIS 14 (+2) CHA 12 (+1) Saving Throws Dex +6, Wis +4 Skills Acrobatics +6, Perception +4, Stealth +6 Senses passive Perception 14 Challenge 4 (1,100 XP) Proficiency Bonus +2 Actions Attack. Melee or Ranged Weapon Attack: +6 to hit, reach 5 ft. or range 60 ft., one target. Hit: 14 (3d6 + 4) damage. MYRMIDON (CR 7) Powerful elite bodyguards, high priests, wizards, warlocks, sorcerers, demons, and devils can all be represented by this stat block. A myrmidon can serve as a boss monster for 5th-level characters, an elite combatant against two characters of 7th level, or a one-on-one combatant against 14th-level characters, or in large groups against 20th-level characters. This stat block focuses on Intelligence. MYRMIDON CON 16 (+3) INT 10 (+0) Saving Throws Str +9, Dex +7 Skills Perception +6 Senses passive Perception 16 Challenge 11 (7,200 XP) WIS 14 (+2) CHA 10 (+0) Proficiency Bonus +4 Multiattack. The sentinel makes four attacks. Attack. Melee or Ranged Weapon Attack: +9 to hit, reach 5 ft. or range 60 ft., one target. Hit: 18 (3d8 + 5) damage. CHAMPION (CR 15) Representing greater demons, devils, vampires, liches, or powerful spellcasters, the champion serves as a boss for 11th-level characters, an elite foe for two 15th-level characters, or a one-on-one challenge against 17th-level characters. This stat block focuses on Charisma. CHAMPION Armor Class 19 (natural armor or magical protection) Hit Points 212 (25d8 + 100) Speed 30 ft. Armor Class 15 (chain shirt or natural armor) Hit Points 130 (20d8 + 40) Speed 30 ft. CON 14 (+2) Saving Throws Dex +5, Wis +5 Skills Perception +5 Senses passive Perception 15 Challenge 7 (2,900 XP) INT 18 (+4) WIS 14 (+2) CHA 10 (+0) Proficiency Bonus +3 Actions Multiattack. The myrmidon makes three attacks. Attack. Melee or Ranged Weapon Attack: +7 to hit, reach 5 ft. or range 60 ft., one target. Hit: 17 (3d8 + 4) damage. 14 DEX 16 (+3) Medium, Large, or Huge Creature Medium or Large creature DEX 14 (+2) STR 20 (+5) Actions Multiattack. The specialist makes two attacks. STR 10 (+0) Armor Class 17 (natural armor or magical protection) Hit Points 165 (22d8 + 66) Speed 30 ft. STR 10 (+0) DEX 12 (+1) CON 18 (+4) Saving Throws Wis +8, Cha +11 Skills Perception +8 Senses passive Perception 18 Challenge 15 (13,000 XP) INT 12 (+1) WIS 16 (+3) CHA 22 (+6) Proficiency Bonus +5 Actions Multiattack. The champion makes four attacks. Attack. Melee or Ranged Weapon Attack: +11 to hit, reach 5 ft. or range 60 ft., one target. Hit: 24 (4d8 + 6) damage. MONSTER POWERS A monster power is a discrete trait or action that can be quickly assigned to a monster to give them an extra edge in combat. As a GM, you can pick from the nearly forty monster powers in this section, all of which are organized by theme, adding powers that fit the type of creature and the story you’re trying to convey. Additional monster powers can also be found in “Building a Quick Monster” on page 4, and “Monster Roles” on page 22. Adding new powers to existing monster stat blocks lets you improve upon creatures who feel too simple, or who might have become familiar to your players. A creature primarily focused on a single attack can be transformed into something far more evocative with a fiery weapon that burns its target, a pinning blow that restrains an enemy, or other exciting options. Monster powers can also add features that a monster lacks, such as a ranged attack, a means of getting away from pesky heroes, or an aura to dissuade too many characters from surrounding a creature. Monster powers can let foes deal stronger damage, or can provide a more flexible means of dealing damage for an exciting encounter. ADDING MONSTER POWERS Monster powers function like any other trait or action a creature already has in their stat block, and are written up in much the same way as those existing traits and actions. POWERS BASED ON CHALLENGE RATING Monster powers sometimes make use of challenge rating to calculate attack bonuses, damage, saving throw DCs, or similar values. This requires some quick math, but allows powers to be used at almost any CR. The one small fix to keep in mind is that when using monsters below CR 1, any final result (such as a bonus to damage rolls) should have a minimum value of 1. It’s recommended that you note the final value for any monster power incorporating CR in your session notes. For example, to give a mummy (CR 3) the Poisonous Demise trait that has a DC of 10 + 1/2 CR and deals 2 + CR poison damage, you would note: “Mummy (Poisonous Demise = DC 11, 5 poison damage).” If you prefer, you can set the attack rolls, save DCs, or damage of monster powers according to the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table (page 6 in “Building a Quick Monster”). In some cases, this can give a monster power’s math greater accuracy. For example, the aberrant power Erase Memory has a DC of 13 + 1/2 CR, or DC 18 for a CR 10 creature. Looking up CR 10 on the table provides a suggested DC of 17. Regardless of what approach you use, final values for powers are always something you should feel free to change to fit your play style and your group’s capabilities. WHEN TO ADJUST CHALLENGE RATING In most cases, you’ll add monster powers because you want a creature to be stronger than a typical creature of the same challenge rating, and you don’t want to rebalance the encounter. If you’re deliberately making an encounter a bit stronger, don’t worry about adjusting CR. If you’re adding monster powers to make creatures more interesting but you don’t want the encounter to be harder, you’ll want to assess whether those powers significantly affect a creature’s CR. When a monster power offers an option a creature doesn’t have (for example, a ranged attack to a melee-focused foe) this generally won’t change challenge rating. But if a power grants a creature additional actions or no-action damage (for example, a damaging aura or a bonus-action attack), the increase in the creature’s overall damage can increase CR. Increasing a creature’s CR by 1 is generally sufficient, or you can use the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table to assess whether extra damage or a boost to AC changes the expected challenge rating. If you reward XP for defeating foes in your game, consider having a creature with one or more monster powers provide the XP of a monster with a challenge rating 1 higher than the baseline monster, to represent the lessons learned from fighting this interesting creature. HOW MANY POWERS? It’s generally recommended to choose one monster power for a normal creature you want to enhance. For creatures playing a particularly important role in the encounter, including boss and solo monsters, choose two or three powers. In combat, most foes will last 2 to 5 rounds before being defeated. The foes who drop most quickly are often the weakest creatures in the encounter, but might also be those foes important enough to attract the characters’ immediate attention. Because of this, most monsters shouldn’t have more than three or four action options, including any added monster powers, unless the flexibility of many actions is needed. Features and actions tell a story. If you have too many, the story becomes muddled. You want characters to react to a creature’s fiery aura as they enter it, but the players might not even remember that aura if it’s part of a list of several other things that happen. You want to pick a few elements and make them important to the encounter. Likewise, the more features and actions your foes have, the harder they can be to run. Monster tactics are usually more effective if you focus on using a few capabilities well. GROUPS OF MONSTERS As a rule of thumb, an encounter is easier to manage when we assign a monster power to all creatures of the same name and type. In a fight with hobgoblin and goblin mercenaries, you might give one power to the hobgoblins to reinforce their role as leaders, even if you then reflavor 15 how the power manifests in each individual. For example, describing the same ranged monster power differently can establish the story of how each hobgoblin sergeant excels with a different weapon. Assigning the power to all hobgoblins is easier to remember than if some hobgoblins have the power and others don’t. An exception to this is when you want to make a single member of a group feel exceptional—for example, a trio of skeletons fighting the party, with one of them on fire. By choosing one creature to be different, you make it easy to make that creature memorable. Adding a different monster power to each of the skeletons would also be memorable, but harder to track. WHAT DO POWERS REPRESENT? It’s up to you to decide whether a monster power is magical (and thus can be shut down in an antimagic field, or dispelled with dispel magic if you treat it as a spell effect), or whether it is natural (representing physical capabilities or training). Thinking through the nature of the powers you add to creatures also helps you lean into the fiction when you use those powers. MONSTER POWERS BY THEME The rest of this section contains monster powers you can use to enhance foes. Powers are organized by themes or types, though each of those themes is merely a suggestion touching on the most obvious flavor associated with a group of powers. Reskinning monster powers is very much encouraged, so that you can use them on any type of creature. A power like Repulsion (below) might represent a magical wave of force, a repulsive smell, a charm or fear effect, roots grabbing the characters, or anything else that fits a monster and the encounter they’re part of. ABERRANT Aberrant powers help to establish a creature as unimaginably alien or steeped in horror. Erase Memory (Bonus Action). The next time this creature hits a target with an attack, the attack’s damage becomes psychic damage and this creature becomes invisible to the target. The target can make an Intelligence saving throw (DC = 13 + 1/2 CR) as an action or at the end of each of their turns, ending the invisibility on a success. A target who succeeds on the saving throw is immune to this effect for 5 minutes. This power can easily be reskinned as an illusionary effect usable by spellcasters, fey, or other magical creatures. A foe can use this power to prevent a specific creature from being able to see them (and perhaps forget they ever existed), forcing the characters to change tactics. Repulsion (Action, 1/Encounter). This creature targets up to eight creatures they can see within 50 feet of them. Each target must succeed on a Charisma saving throw (DC = 13 + 1/2 CR) or immediately move their speed away from this creature, avoiding hazards or dangerous terrain if possible. On a failed save, a target creature can’t move closer to this creature. An 16 affected target can repeat the saving throw at the end of each of their turns, ending the effect on themself on a success. Repulsion is an excellent way to keep characters away from an otherwise vulnerable foe. Even if only a few characters fail their saving throws, the number of characters who can fight the foe in melee is reduced. This is a powerful action to add to a monster acting as a guardian to other vulnerable creatures. You can explicitly make this a fear effect and use the frightened condition if doing so fits the foe and the situation. Displace Enemies (Bonus Action). Each enemy within 30 feet of this creature must succeed on an Intelligence saving throw (DC = 11 + 1/2 CR) or be teleported up to 20 feet to an unoccupied space of this creature’s choice that this creature can see. As an alternative to Repulsion, this power can be used to move targets away from a vulnerable foe. But it can also be used to place heroes over pits (allowing a DC 10 Dexterity saving throw to grab the edge), move characters next to dangerous foes, lift them up and drop them, and explore other devious tactics. If you change the power to target all creatures or target allies instead of enemies, it could be used to move companion creatures out of danger (with those creatures allowed to intentionally fail their saving throws). Adhesive Skin (Trait). When this creature is hit by a melee weapon attack, the weapon becomes stuck to them. A creature can remove a stuck weapon with an action and a successful DC 14 Strength (Athletics) check. All items stuck to this creature become unstuck when the creature dies. Sure to surprise your players, this power should be given only to a single creature to avoid frustration. It can lead to different tactics, or to characters drawing one weapon after another to keep attacking in melee. Enjoy describing the gross skin the monster has to enable this trait! BESTIAL Bestial powers underscore the ferocious and wild nature of beasts and other feral creatures. Earthshaking Demise (Trait). This creature must be size Huge or larger. When this creature dies, they topple to the ground, forcing each smaller creature within 20 feet of this creature to succeed on a DC 15 Strength saving throw or be knocked prone. This power reminds players of the considerable size and weight of creatures such as dinosaurs. It works best when several creatures all have this trait, so that as each one falls, the characters feel the effect impact the battle. Beyond bestial creatures, this trait works well for constructs, dragons, and other physically mighty foes. Retaliation (Reaction). When this creature is hit by a creature they can see, they can make an opportunity attack against the attacker. A beast that bites back feels feral and dangerous. This is also an effective power for other creature types, especially boss monsters who can benefit from an off-turn attack. MAKE THESE POWERS YOURS Though all these monster powers can be used exactly as written, they’re meant to be starting points that you can alter to fit your particular needs. For example, Displace Enemies is a strong effect, allowing a creature to rearrange the battlefield as a bonus action each turn. But for some encounters, it might be appropriate to limit this power with a recharge so it comes up less frequently. A power such as Armor of Frost is a reaction by default, limiting it to being used once per round by a draconic creature. But if you decide that power would work well for an ice elemental, you can represent that creature’s icy nature by lowering the damage but making the power a trait that triggers every time the elemental is attacked. For an ice titan, you might keep the power as a reaction but increase the damage, to represent the titan’s elemental might. It’s a great power to improvise, applying it to any foe when you want them to appear more dangerous and to surprise the characters. Some boss monsters might have multiple reactions, which also works well with this power. CHARM OR FEY Compulsion powers wielded by fey creatures and others with a penchant for enchantment demonstrate a supernatural capability to influence characters. These powers should be used sparingly, so as to present an interesting challenge without becoming frustrating or repeatedly removing the sense of agency that players enjoy. Words of Treachery (Action). This creature speaks deceitful words at a target within 20 feet of them who can see and hear them. The target must succeed on a Charisma saving throw (DC = 12 + 1/2 CR) or immediately use their reaction to move up to 10 feet and make a melee or ranged weapon attack against a target of this creature’s choice. The compelled target uses an attack they would typically make against a foe. This power works well when you roleplay what the creature says, then have the player attempt their saving throw and roleplay the outcome. Turning a character into an ally in combat can be a powerful option for a foe, as many characters deal more damage with their actions than monsters do. You can alter the power to work without spending the target’s reaction if you feel that losing a reaction might lessen a player’s fun. You can also decide whether a creature immune to the charmed condition is immune to this effect, or if it channels a different type of compulsion. Charming Words (Action, Recharge 5–6). This creature chooses any number of targets within 60 feet of them who can hear them. Each target must succeed on a Charisma saving throw (DC = 11 + 1/2 CR) or be charmed by this creature until the end of their next turn. This area-of-effect compulsion can keep a monster alive by preventing some or all of the characters from attacking them. It’s best used when a fight has other potential targets, so characters can attack a different creature and stay engaged. CONSTRUCT Powers that suggest precision and programming work well for golems, clockwork creatures, and other constructs. Improved Critical Range (Trait). This creature’s attacks score a critical hit on a roll of 17–20. This power works particularly well for multiple lowthreat creatures, creating a better chance that one or more will score a crit. You can alter the critical hit range based on the story you’re telling. For example, low-CR constructs with a critical range of 15–20 could be a lot of fun, hitting surprisingly hard but dying quickly. You can also use this power with nearly any other creature type, representing preternatural acuity or battle training. Be careful with giving formidable foes this trait, and consider reducing the range if you do—especially at low levels of play where critical hits can have a big impact on play and easily result in character death. But, yes, a vorpal tyrannosaurus does sound awesome. Erratic Gears (Trait). At the start of each of this creature’s turns, roll a d6 to determine what they do: 1: The creature’s internal mechanism stops working and they do nothing this turn. 2: The creature acts normally. 3–5: The creature has a surge of power that causes them to deal an extra CR damage on each attack this turn. 6: The creature speeds up, letting them use two actions this turn. The chaotic nature of this power lends itself to constructs experiencing malfunctions or not under the direction of a creator. It works best if given to several creatures, so that on average, they will still be effective and engaging. This power is meant to be as much evocative as effective, but you can alter the effects to change that. DRACONIC Ancient and awe-inspiring creatures, dragons might grant powers to any other creatures who serve them. Creatures might also seek to steal a dragon’s essence or emulate their capabilities. The powers below are tied to specific dragon types, but can be easily reskinned by changing damage types or effects to represent other dragons. Acidic Weapon (Trait). The first time on a turn that this creature hits with a weapon attack, the attack deals an extra 2 + CR acid damage, and the target takes a cumulative –1 penalty to AC (to a maximum −3 penalty) until the end of the encounter. Armor of Frost (Reaction). When this creature is hit by a melee weapon attack, the attacking creature takes 4 + CR cold damage and their speed is halved until the end of their next turn. Electrified Armor (Reaction). When this creature is hit by a melee weapon attack, the attacking creature takes 4 + CR lightning damage and has disadvantage on their next attack roll. Flaming Weapon (Trait). The first time on a turn that this creature hits with a weapon attack, the attack deals an extra 17 4 + CR fire damage and the target’s armor or skin begins to smolder. While smoldering, the target has vulnerability to fire damage. The target can make a Constitution saving throw (DC = 11 + 1/2 CR) at the end of each of their turns, ending the effect on themself on a success. Poison Strike (Trait). The first time on a turn this creature hits with a weapon attack, the attack deals an extra 2 + CR poison damage and the target takes 2 + CR poison damage at the start of each of their turns. The target can make a Constitution saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) at the end of each of their turns, ending the effect on themself on a success. These powers can be given to humanoids or other creatures serving dragons, or can be reskinned to work as elemental powers or to represent beasts or monstrosities tied to elemental forces. For example, a massive winter wolf might have a hide that radiates cold, represented by the Armor of Frost power. The Acidic Weapon power is assumed to harm armor in a way that is easily repaired. However, you might decide that the penalty lasts until the target can repair their armor during a short or long rest. ELEMENTAL The following powers can be modified to reflect a particular type of elemental creature. Adding these powers to elementals not only strengthens them, but can help better portray their elemental nature. These powers can also be used with other creature types, reflecting the creature’s association with an environment tied to a particular element or some other factor that has imbued them with elemental energy. Elemental Shroud (Reaction, 1/Encounter). When this creature is hit by a melee attack, their body is shrouded with energy of the type they are associated with (acid, bludgeoning, cold, fire, lightning, or thunder) until the start of their next turn. While this creature is shrouded, any creature who touches this creature or hits them with a melee attack while within 5 feet of them (including the triggering attacker) takes 5 + CR damage of the associated type. Characters can choose to keep attacking a foe with this power, but will take damage when doing so. This can be an excellent way to convince characters to take other actions, such as interacting with important noncombat elements of an encounter. The short duration for this power makes it significantly different from similar shield auras, but it can deal a lot of damage while it lasts. You can raise the number of times per encounter the power can be used, or even tie its use to an object or mechanism in the encounter so that the characters can disable the mechanism to turn the power off. If you want the shroud to function as a shield and really dissuade characters from attacking, it could provide temporary hit points to the foe as well. Elemental Seepage (Trait). Whenever this creature is below half their hit point maximum, they radiate an aura of elemental energy of the type they are associated with (acid, bludgeoning, cold, fire, lightning, or thunder). Any creature who moves within 10 feet of this creature for the first time on a turn or starts their turn there takes 5 damage (10 damage if this creature is CR 12 or higher) of the associated type. When present on several creatures in an encounter, this power encourages characters to focus fire so as to face fewer auras. You can contract or enlarge the aura to change its lethality and the number of characters who’ll be impacted tactically by it. The power’s relatively low damage means it works well for multiple creatures, but if given to only one or two creatures, the damage could be equal to CR or even 5 + CR. LEADERSHIP Leadership powers work best on a monster acting as a boss to other creatures, showcasing how they command or bolster their underlings. Commander (Trait). While this creature is at half their hit point maximum or above, each ally within 30 feet of them has a +2 bonus to attack and damage rolls. Roleplay the instructions a creature with this trait gives out to underlings, directing their attacks and lifting their morale. Establishing that the commander looking healthy is inspiring their troops can clue the players in to the need to focus fire to end the benefit. For a stronger effect, the +2 attack bonus could be replaced with advantage. Fanaticism (Trait). While this creature is below half their hit point maximum, whenever they take damage and an ally is within 5 feet of them, this creature takes half the damage and the chosen ally takes the remaining damage. Additionally, while this creature is below half their hit point maximum, each ally within 30 feet of them has advantage on attack rolls. 18 This power paints a different story in combat than the Commander power, showing a leader whose desperation fuels the fury and devotion of their foolish followers. Inspire Troops (Reaction). When this creature succeeds on a saving throw or when an attack roll against them misses, one ally who can see this creature gains 5 + 1/2 CR temporary hit points. You can make this power a trait if you want it to be the centerpiece of an encounter. Smart characters will attack other creatures instead, but that might also work in the leader’s favor. MAGIC Magic powers can represent spells and eldritch energy, but might also connect to divine blessings, magic items or artifacts, and the ability to tap into powerful sources of otherworldly energy. Many creature stat blocks feature attack options that resemble spells but aren’t explicitly called out as being so. The default intention in this section is that magic monster powers should work equally well with a spell or an attack that resembles a spell. So simply replace wording such as “casts a spell” with “casts a spell or uses an action that resembles a spell” to meet your intention. Similarly, some creatures have traditional spell slots, while others may have a number of uses of certain spells per day. This section considers those two approaches to spellcasting interchangeable, though you can adjust that to your preference. Careful Sorcery (Trait). When this creature casts a spell that forces one or more creatures to make a saving throw, they can choose up to three of those creatures. Each chosen creature is immune to the effects of the spell. Careful Sorcery allows a spellcaster to use powerful area-of-effect spells and exclude some or all of their companions. This can be a fun surprise during a combat in a small room. Dual Concentration (Trait). This creature can concentrate on up to two spells simultaneously. When making a concentration check, the creature makes a separate check for each spell upon which they are concentrating. Many spellcasting creatures have an abundance of spells requiring concentration. This lets such creatures employ two of those spells at a time, which can be explained as the creature being uncommonly powerful, by the use of a magic item, or by an expendable focus being used to cast the second spell. BRIAN PATTERSON Spell Shield (Reaction). When this creature is the target of an attack, they can expend a spell slot or one use of a spell or magical attack (other than an at-will magical attack) to add +4 to their AC until the start of their next turn. Many spellcasting creatures have more spell slots than they can use in a fight, so this power turns extra slots into a powerful asset. You can modify this power to instead grant a bonus to attack rolls or damage for 1 round if that better fits the monster concept. Quickening (Trait, 2/Day). When this creature casts a spell that has a casting time of 1 action, they can change the casting time to 1 bonus action for this casting. The creature can cast up to two spells this turn, including two spells that aren’t cantrips. Most spellcasting monsters and NPCs can cast only a few spells before being defeated, making them not much of a challenge. Allowing a spellcaster to have 2 rounds where they cast any two spells makes them far more challenging. You can roleplay or describe the effort a spellcasting foe makes to accomplish this, so the players know the creature can’t do so every single round. NECROMANTIC Wielding power over death adds an aspect of horror to any foes, or enables necromancers or undead to better showcase their capabilities. Aura of Demise (Trait). Each enemy within 30 feet of this creature who makes a death saving throw does so with disadvantage. Seeing any character drop to 0 hit points while near a creature with this power will have all the players on the edge of their seats. Aura of Destruction (Trait). Each creature who ends their turn within 5 feet of this creature (or within 10 feet of this creature if this creature is CR 12 or higher) must make a death saving throw, regardless of their current hit points. With three successes, a creature no longer needs to make death saves against this effect. With three failures, a creature dies. Having to make a death saving throw for standing next to a creature? Your players won’t expect that. Truly cruel GMs can combine this and Aura of Demise for a nailbiting challenge. Alternatively, you can soften this power by having three failures reduce an affected creature to 0 hit points—at which point they begin making death saves again as normal. 19 Undying Allies (Trait). When an ally who can see this creature is reduced to 0 hit points, that ally immediately becomes a zombie (retaining their original stat block but gaining the undead type), and stands up with 1 hit point. From that point on, if damage reduces the zombie to 0 hit points, they must make a Constitution saving throw with a DC of 5 + the damage taken, unless the damage is radiant or from a critical hit. On a success, the zombie drops to 1 hit point instead. Any ally who becomes an undead from this trait is destroyed if this creature dies or is destroyed. Roleplay the necromancer with this power urging their fallen allies to rise up and strike down the heroes. This places an urgency on defeating the necromancer rather than their allies, since killing allies only results in more undead. Withering Blow (Bonus Action, Recharge 4–6). The next time this creature hits with an attack, the target takes 5 + CR necrotic damage at the start of each of their turns. The target can make a Constitution saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) at the end of each of their turns, ending the effect on themself on a success. The effect also ends if this creature dies or is destroyed. For maximum effect, describe how this blow causes a character’s flesh to wither, shrivel, and take on the gray color of undead flesh. For even greater effect, you could have the extra damage from this power also reduce the target’s hit point maximum. But that’s probably too evil. Probably. PLANT AND POISON These powers work equally well for plant creatures, reptiles, and other foes who might be poisonous or venomous. Poisonous Demise (Trait). When this creature is reduced to 0 hit points, they release a spray of poison. Each creature within 30 feet of this creature must succeed on a Dexterity saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) or take 2 + CR poison damage. This trait can be reskinned for other types of creatures, such as elementals and undead, by changing the damage type. You can likewise change the area of effect to better reflect your monster or the desired challenge. The default distance is based on a single monster having this power. If multiple creatures in an encounter have it, reducing the distance to 5 or 10 feet works well. Virulent Poison (Trait). This creature’s attacks that deal poison damage ignore a target’s resistance to poison damage. If a target has immunity to poison damage, that target instead has resistance to poison damage against this creature’s attacks. Additionally, the first time each turn that this creature deals poison damage to a target, that target is poisoned until the end of their next turn. 20 Poison is a common damage type for characters to resist, which can reduce the challenge of poisonous or venomous foes. You can simplify this power and reduce its potency by removing the poisoned condition, or you can strike a balance by providing a Constitution saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) against that condition. ROGUE Sneaky or skirmishing creatures can all benefit from these rogue-type powers. Impersonate (Bonus Action, Recharge 6). Until the start of their next turn, this creature changes their appearance to look exactly like another creature who is within 5 feet of them and is no more than one size smaller or larger than this creature. Other creatures must each make a Wisdom (Perception) check (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) each time they make an attack against this creature or the impersonated creature. On a failure, the attack is made against the wrong target. This power can be narratively rendered as shapeshifting ability, an illusion effect, beguiling words from a fey, or a confusing effect caused by an aberration. Nimble Reaction (Reaction, Recharge 4–6). When this creature is the only target of a melee attack, they can immediately move up to their speed without provoking opportunity attacks. If this movement leaves this creature outside the attacking creature’s reach, this creature avoids the attack. This reaction lets a foe avoid taking damage while also conveying the feel of a nimble combatant capable of escaping certain danger. You can alter the recharge to reflect just how nimble a creature is. SOLO Solo powers work well when a single creature is used in an encounter, or when one creature is the obvious target and needs to survive focused fire. Bloody Legendary Resistance (Trait). If this creature fails a saving throw, they can choose to succeed instead. Each time they use this trait, this creature takes 4 + CR damage. This power provides an alternative to the Legendary Resistance trait, with the hit point cost making it more rewarding for characters to cast spells and use features that require a saving throw, knowing that having a foe succeed on those saves carries a different cost. At the same time, a monster can use this power more often than Legendary Resistance, protecting them from the repetitive uses of features that can hinder a solo creature’s ability to be effective. For an alternative approach, replace the damage dealt with the creature losing the ability to use one of their actions or traits until the end of their next turn. Magic Resistance (Trait). This monster has advantage on saving throws against spells and other magical effects. A great option when building solo monsters is to give them the ability to shrug off spells and magical effects, common in most legendary or highly magical monsters. Magic Resilience (Trait). Whenever this creature is subjected to a spell or other magical effect that does not grant a saving throw, the creature can make a DC 15 Charisma saving throw, avoiding the effect on a success. This trait lets you build an even more potent magicdefiant foe. You can change the ability score used for the saving throw to reflect the nature of a particular creature, or base it on the type of effect being avoided. Things will get interesting for the characters when a boss monster unexpectedly breaks the walls shaped by a forcecage spell or overcomes some equally powerful effect. Use this power sparingly, though—and don’t give your players our email addresses. challenged. A challenged creature has disadvantage on attack rolls against any creature other than the challenging creature. At the end of each of their turns, a challenged creature can make a Charisma saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR), ending the challenge on themself on a success. Perfect for a monster with the defender role (see “Monster Roles” on page 22), this power incentivizes characters to engage with a formidable foe rather than go after weaker targets. Pack Tactics (Trait). This creature has advantage on an attack roll against a target if at least one of this creature’s allies is within 5 feet of this creature and the ally isn’t incapacitated. A superb trait, Pack Tactics allows monsters to work together in an obvious tactical fashion to gain advantage. This trait can be used for many types of monsters, representing the cunning tactics they employ. Pinning Shot (Trait). When this creature hits with a ranged weapon attack, the target must succeed on a Strength saving throw (DC = 9 + 1/2 CR) or have their speed reduced to 0. An affected creature can repeat the saving throw at the end of each of their turns, ending the effect on themself on a success. Just one or two combatants with this trait can force the characters to adjust tactics as some of them are pinned in place. To make this power stronger, it can impose the restrained condition instead of just reducing speed. Either way, be careful not to overuse this power and frustrate the players. Ultimate Resolve (Trait). If this creature takes damage while incapacitated, paralyzed, or stunned, they gain an extra attack the next time they use the Attack action. This trait can grant a maximum of one extra attack if the creature is CR 6 or lower, two extra attacks if they are from CR 7 to CR 12, and three extra attacks if they are CR 13 or above. This is an excellent power for boss or solo monsters likely to be denied actions by the characters’ tactics. That action denial still takes place, but the creature has a chance to make up for it. WARRIOR BRIAN PATTERSON Warrior powers represent tactics and capabilities honed through battle. Challenge Foe (Bonus Action, Recharge 4–6). The next time this creature hits a target, in addition to the regular effect of the attack, that target is 21 MONSTER ROLES Thinking about the roles that creatures play in combat helps to create better encounters. A monster who has tons of hit points can stand up front, soaking up damage while the more vulnerable evil wizard launches devastating spells from behind cover. Skirmisher monsters can dart in from the sides and back away, forcing the characters to spread out and leaving them open to an ambusher. Foes of different roles complement each other, creating an effective team. Monsters in 5e don’t have defined roles with connections to specific mechanics and tactics, as the creatures in some fantasy RPGs do. However, many 5e foes either already fit a specific role or are flexible enough to allow us to assign roles to them. For example, a harpy is a highly effective controller, and a spy is an excellent skirmisher or ambusher. We can also modify monsters to enable them to play a role. By assigning a role to a foe, you enable a specific set of tactics that allow you to challenge the characters more effectively. DEFINING ROLES The following roles capture the most important tactical concepts in 5e combat, and cover virtually all the foes you might make use of in a 5e game. AMBUSHER Ambushers have special features that allow them to hide, dart out of danger, render targets senseless, or otherwise prevent characters from attacking them easily. An ambusher often deals more damage when hidden, and might engage in a pattern of hiding, attacking, and hiding again. Ambusher foes are often less effective when they can’t hide, which incentivizes characters to force them into the open. Many ambushers have low hit points. When to Use Them. Because ambushers can result in longer, drawn-out fights, you want to use them sparingly. However, they can be a good choice for a villain who needs to get away. Ambushers are likewise an excellent choice if a combat encounter is preceded by a free-form roleplaying or social encounter, with foes hiding in plain sight before the fight breaks out. Placement and Tactics. An ambusher is usually most effective when they start out hidden, revealing themself only when they attack. Some ambushers start out in the open, then disappear and reposition once characters have moved toward them. Example Ambushers. Dust mephit, ghost, mimic, phase spider, spy. ARTILLERY Artillery typically have a high attack bonus and deal good damage at range, but have lower hit points or AC than other foes. Sacrificing survivability can be fun, allowing these monsters to hit hard and die quickly. This creates 22 tension and pressure early in an encounter, followed by increasing confidence as the heroes reach the artillery and quickly defeat them. Artillery creatures might strike at single targets or an area, and their high accuracy lets them deal consistent damage. Because they operate at range, you might focus the attacks of artillery foes on characters who usually stay out of trouble, using the flexibility of range to put them in peril. Alternatively, you can put their accuracy to use against the characters with the highest defenses. When to Use Them. Artillery creatures work well in most encounters. Because of their placement at range, they draw attention away from other important targets such as controllers, leaders, or bosses. Artillery foes encourage characters to use resources to reach them, finish them off, and heal from their long-range damage. Placement and Tactics. Artillery creatures seek cover and elevation from which to rain down destruction. They stand behind other monsters and blocking terrain so that characters can’t easily get to them. They might also be placed without cover and to the sides of the battle, forcing characters who want to attack them to spread out—so that ambushers or skirmishers can pick those characters off. Place artillery closer to the action when you want them to be easy to reach and to draw attention deliberately away from other foes. Artillery creatures like to focus fire and group up on one target when possible. However, you want to change up that tactic if you start rolling too well, which can make artillery creatures extremely dangerous even in relatively easy encounters. Make sure getting to artillery foes is fun and not frustrating. A good rule of thumb is that characters shouldn’t need to spend more than 1 round of movement to engage an artillery creature. Example Artillery. Hill giant, mage, manticore, scout, solar. Of all the roles, artillery creatures are generally the least represented in the 5e Monster Manual and other books, but you can easily build artillery with additional monster powers (see “Reinforcing Roles with Powers” later in this section). BRUISER A bruiser foe deals higher-than-average melee damage, bringing the pain up close. But that focus on damage often comes with lower AC, lower attack accuracy, or lower hit points. Bruisers draw attention with their damage, and make fun opponents because they’re often easy to hit, or die quickly. When a bruiser has low accuracy, a battle often feels swingy, with a sense of impending doom as each attack roll creates tension. Even when an attack misses, the players are usually watching that roll and wincing as they think about what would have happened if it hit. When to Use Them. Bruisers should be used in most encounters, surprising players with their impressive CONTROLLER DANNY PAVLOV damage. However, they should be used with care in encounters against 1st-level characters, who are particularly susceptible to being dropped with a single lucky blow. Like artillery, bruisers can be used to draw attention away from other important targets such as controllers, leaders, and bosses. Bruisers encourage characters to use resources, first to finish off the bruiser more quickly, then to heal up in the aftermath. Placement and Tactics. Melee bruisers should be in the front lines, where they can deal damage as soon as possible. They might come out of side passages or otherwise surprise characters in the rear ranks, but bruisers seldom switch targets unless a different target is obviously easier to kill. Bruisers like to focus fire and group up on one target when possible, so keep an eye on their damage output to ensure that a few lucky attack rolls don’t push the challenge level of an encounter too high. Example Bruisers. Ettin, flesh golem, owlbear, shambling mound, wolf. Controller creatures use their attacks and features to impose conditions or otherwise impede characters from being their most effective. This role covers many different types of foes, and the extent of their control can vary. Some controller creatures grapple, swallow, or otherwise lock down targets, preventing movement. They might impose disadvantage on attacks through conditions such as poisoned or restrained, or use magic such as the confusion or hold person spells to limit actions. When to Use Them. Controllers create dilemmas for a party to contend with. How do the characters change tactics when the fighter is poisoned and the cleric is inside a creature’s gullet? These situations can be exciting and challenging, forcing characters to expend resources and think of clever solutions. However, used too often, too extensively, or too effectively, controller foes can feel like punishment. Be wary of a character rendered ineffective for several rounds, or of more than a couple of characters being ineffective for longer than 1 round. When a control effect feels clearly frustrating, try to change targets over the course of combat so that the same character isn’t being controlled round after round. Placement and Tactics. Controllers should be placed where they can’t be easily reached, but close to prospective targets based on the range of their powers. Spellcaster controllers might be careful to always start farther than 60 feet from the characters—beyond the range of counterspell. A controller pairs well with a defender whose job is to keep the controller safe, or with skirmishers who can easily move around controlled characters. Controllers usually have trouble defeating characters one-on-one, due to their lower damage, but they work well with bruisers and artillery who can deal high damage to controlled characters. Example Controllers. Black pudding, cockatrice, ettercap, harpy. DEFENDER Defender foes soak up hits and damage. They might deal lower-than-average damage or be less accurate with attacks, but have higher AC, saving throws, and hit points. They often look big and imposing, drawing attention to themselves by issuing challenges and making threats. Some defenders have attacks or features that pin characters in place—often referred to as “sticky” features that make the defender hard to get away from once engaged. Stickiness can also take the form of imposing penalties to attack any creatures other than the defender, or similar features that help the defender soak up the heroes’ attacks. When to Use Them. Defenders should be used sparingly, as too many defenders in an encounter or too many encounters featuring defenders can make combats longer and less interesting. Use them in fights where other vulnerable foes need assistance to prevent being taken 23 down too quickly. Defenders work well with skirmishers or ambushers, who can surprise characters focused on the defender. They excel at protecting key villains, especially artillery or controller spellcasters. Placement and Tactics. Defenders are often placed in the front lines to tie down characters. However, you can also place them farther back, closer to another creature they defend. Make sure defenders won’t lock down all the characters at once, though. Combat works best when most characters can move around the encounter area and discover all it has to offer. You don’t want to design an amazing encounter and then have the characters spend all their time locked down in specific locations. Example Defenders. Animated armor, chuul, gelatinous cube, knight, shambling mound. LEADER A leader has features that help other creatures. They might heal, boost statistics such as attack modifiers or saving throws, or move other creatures, and they often have lower-than-average hit points, damage output, or accuracy. When to Use Them. Leaders are most interesting when used sparingly, though they can be used more often when they are of different types. For example, a hobgoblin priest NPC focused on healing feels different from a duergar war priest who boosts their allies’ attacks. Placement and Tactics. Leaders can be placed according to the focus of their useful features, letting them help as many of their allies as possible. Because the characters often want to target them, leaders operate best in the center or slightly back from the center of the encounter area. Leaders make good bosses, or can act as lieutenants for bosses. Be careful when using them with skirmishers and ambushers, though, since characters moving to pursue those foes might go after the leader instead. A good default setup is to have one or two defenders protecting a leader. Example Leaders. Couatl, knight, priest. SKIRMISHER Skirmishers dance around the battlefield, using high mobility to dart in for an attack and then get away. They might have lower AC or hit points than other foes, but possess features that let them evade blows, retreat, or counterattack. Skirmishers are usually accurate, having a high attack bonus, and their damage might be especially high when using their mobility features. When to Use Them. Use skirmishers to liven up battles. They can draw characters farther into an area of combat, making good use of areas that have dividing features such as interior walls, side chambers, or more than one level. Placement and Tactics. Skirmishers should usually start far enough from the characters to show off their ability to move in and then move back out, forcing characters to reposition themselves. Skirmishers with high speed or 24 supernatural movement can avoid or surpass terrain that challenges pursuing characters, who might trigger traps or spread out so other foes can surround them. Example Skirmishers. Bulette, copper dragon, goblin, spy, wraith. ADDITIONAL ROLES Beyond the broad categories that define a creature’s role in combat, many monsters also have a role shaped by how weak or tough they are relative to other foes. BOSS A boss monster stands out because they are clearly stronger than the creatures around them, most commonly because they have a higher challenge rating than those creatures. You can also make a boss stand out by providing them with either a high AC to make them harder to hit, or with high hit points to keep them in the fight right to the end. Adding a unique monster power (see below) can also help distinguish a boss, particularly if that power allows them to bolster or command a lieutenant and other monsters. Lieutenants can be thought of in much the same way as bosses, but have a lower CR and fewer features than a main boss. “Building and Running Boss Monsters” (page 31) and “Bosses and Minions” (page 61) has more thoughts on this topic. “Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” (page 67) offers up suggestions for how to build encounters with a boss. SOLO When a creature is the only foe in an encounter, they will be a higher challenge rating than most creatures the characters encounter. But because of the action economy of the game, CR alone isn’t enough to make a solo creature effective. Legendary actions and lair actions help a monster act more often, keeping the pressure high in combat and reducing the chance of a round where a solo foe accomplishes nothing. You can also add monster powers to help the creature stand out. “Building and Running Legendary Monsters” (page 28) and “Understanding the Action Economy” (page 42) offer guidance on solos. “Creating Lair Actions” (page 36) has additional tips for a solo creature who has a strong connection to their lair. MINIONS AND UNDERLINGS As talked about in “Bosses and Minions,” we sometimes want a boss or a main monster to be accompanied by several weak foes. These minions and underlings can swarm a party, but are fun for the characters to easily defeat. Low-CR creatures make good underlings, which you can run using the advice in “Running Minions and Hordes” (page 54). But you can also make use of the following quick minion concepts, built around the CHOOSE TWO TYPES Mike has a simple hack for making combat encounters more engaging without getting too complicated in their design— choose just two types of monsters. Two types of monsters offer enough variance to make a combat encounter tactically interesting without forcing you to spend a lot of time thinking about monster roles overall. Ideally, these two types come from opposite ends of the monster spectrum. Melee bruisers paired with sneaky ambushers. Powerful defenders protecting weaker artillery. Controllers shaping the battlefield to the advantage of skirmishers. You can often simplify this concept down to: “Big dudes up front and weaker damage dealers in the back.” It’s also worth remembering that not every battle needs to be a mix of different monster types. Sometimes the characters just want to blow up a horde of skeletons, and sometimes the pacing works best when five 7th-level heroes run into a pair of bandits throwing dice. (“Running Easy Monsters” on page 124 talks more on that topic.) minions of the 4e game who could survive only one solid hit. For these minions, you use all of a monster’s normal statistics, but you ignore their normal hit points and use one of the following mechanics instead. One-Quarter Health. A minion has one quarter of the hit points they would normally have, taking them out of the fight quickly. A minion of this sort is worth one sixth of their usual XP value if you use XP for encounter building. Save or Die. Each time a minion would take damage, they must attempt a DC 20 Constitution saving throw. On a success, the minion survives, and on a failure, they die. Each time a creature is hit after the first, the DC increases by 10. This allows for even creatures of high challenge rating to function as minions, with a failed save coming eventually. You can alter this DC or the increase to change a foe’s survivability. A minion of this sort is worth one quarter of their usual XP value for encounter building. Even Odds. Each time a minion would take damage, they must roll a die. If an even number is rolled, the minion dies. This is a variant of the save-or-die approach, with a flat 50 percent chance to survive with each hit, and making no adjustment for a monster’s CR. A minion of this sort is worth one quarter of their usual XP value for encounter building. One Hit Point. A minion has just 1 hit point, but is only affected by damaging effects that target that specific minion. The first time such minions are targeted by effects that deal damage to multiple creatures in an area, the minions are immune. But those minions die when targeted a second time with damaging area effects. This approach allows greater tactical choices for those using damaging spells or other effects that target an area. A minion of this sort is worth one sixth of their XP value for encounter building, though you can reduce this if the characters can easily target multiple minions. REINFORCING ROLES WITH POWERS In addition to determining what role a monster might play in combat based on their existing statistics and attacks, we can also treat roles as a template, adding features that reinforce a particular role. Any of the monster powers in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4) or “Monster Powers” (page 15) might help a creature fulfill a specific role, but this section presents additional powers specifically tied to each monster role, as well as advice for adjusting statistics to help a creature fulfill a role. “Monster Powers” talks in detail about the format and use of powers. AMBUSHER To build an ambusher, reduce AC by 2 or reduce hit points by 20 percent. An ambusher gains proficiency in Stealth and uses double their proficiency bonus for Dexterity (Stealth) checks. Then give the ambusher one or more of the following powers: Distracting Attack (Trait). When this creature hits with an attack, they can become invisible until the start of their next turn. Shadowy Movement (Trait). This creature can attempt to hide in dim light or lightly obscured terrain. When this creature moves, they can make a Dexterity (Stealth) check to hide as part of that movement. Elusive (Bonus Action). This creature takes the Dash, Disengage, or Hide action. Duck and Cover (Trait). When this creature hits a target with an attack and has advantage on the attack roll, they deal CR + 2 extra damage. The Nimble Reaction power in “Monster Powers” is also a good fit for an ambusher foe. ARTILLERY To turn a stat block into an artillery foe, increase the creature’s attack bonuses by 2, or increase attack bonuses by 1 and increase the damage of all attack actions by 1 for each damage die rolled for the attack (so that 2d8 damage gains a +2, 3d6 damage gains a +3, and so on). Then either decrease hit points by 20 percent or decrease AC by 2. You can then give the creature any of the following powers: Ricochet (Reaction). When this creature misses with a ranged attack, they can reroll that attack. Quick Step (Reaction). When this creature would make a ranged attack, they can first move 5 feet without provoking opportunity attacks. 25 BRUISER To build a bruiser, either decrease attack bonuses by 2, decrease hit points by 10 percent and attack bonuses by 1, or decrease AC by 2. Then increase the damage of all attack actions by 2 for each damage die rolled for the attack. You can alternatively let each attack deal an extra CR damage. (At low challenge ratings, for specific powerful actions, or to provide a higher challenge, this additional damage can be increased to 3 × CR.) You can then give the creature any of the following powers: Opportunist (Trait). This creature can make an opportunity attack when any creature moves within their reach, even if that movement would not normally trigger an opportunity attack. Offense over Defense (Bonus Action). Until the end of their turn, this creature deals an extra CR damage on attacks but reduces their AC by 2. You might also consider the Goes Down Fighting power in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4) or the Improved Critical Range power in “Monster Powers” (page 15) for a bruiser foe. CONTROLLER To create a controller creature, reduce the damage of each of the creature’s attack actions by 1 for each damage die rolled for the attack. Then increase the saving throw DCs for each of their non-damage-dealing attacks and features by 2. You can then give the creature any of the following powers: Controlling Attacks (Trait). When this creature hits a target with an attack, they impose one of the following conditions, based on the creature concept: blinded, charmed, frightened, grappled, poisoned, prone, or restrained. The condition lasts until the end of the target’s next turn. Controlling Spells (Trait). Choose up to two of the following spells: blindness/deafness, command, entangle, grease, gust of wind, hideous laughter, hold person, levitate, ray of enfeeblement, silence, suggestion, or web. This creature can cast any of the chosen spells as an action. If this creature does not yet have a spell save DC, the save DC for these spells is 10 + 1/2 CR. Once chosen, the spells cannot be changed for this creature. Advanced Controlling Spells (Trait). Choose one spell from the Controlling Spells trait that this creature can cast. This creature gains one of the following benefits: • The spell can be cast as a bonus action. • The spell can be cast as a reaction to taking damage from an enemy. • If the spell normally targets one creature, it can instead target two creatures within its normal range. For a ranged controller, consider the Pinning Shot power in “Monster Powers” (page 15). DEFENDER To make a creature into a defender, increase their AC by 3 or increase their hit points by 30 percent. Grant them a +2 26 bonus to saving throws, increasing to +5 if the characters are 11th level or higher. Then decrease their attack roll bonuses by 2, or reduce their attack roll bonuses by 1 and reduce the damage of all attack actions by 1 for each damage die rolled for the attack. You can then give the creature any of the following powers: Stick with Me (Trait). When this creature hits with an attack, the target has disadvantage on attack rolls against any creature other than this one until the end of the target’s next turn. For a slightly more complex version of the Stick with Me power, see the Challenge Foe power in “Monster Powers” (page 15). Blocker (Trait). Any creature starting their turn next to this creature has their speed reduced by half until the end of the affected creature’s turn. You might also wish to consider the Defender power in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4). LEADER To turn a foe into a leader, either reduce that foe’s attack bonuses by 2, reduce their hit points by 20 percent, or reduce the damage of all attack actions by 1 for each damage die rolled for the attack. Then give the creature any of the following powers: Shout Orders (Bonus Action, Recharge 4). This creature chooses up to six creatures who can see and hear them. Those creatures can immediately either move their speed or take an action. Heal Ally (Bonus Action). This creature can choose another creature they can see and hear within 50 feet of them. The chosen creature regains hit points equal to 25 percent of their hit point maximum. Lead by Example (Trait). When this creature hits a target with an attack, any ally of this creature who can see the target has advantage on attack rolls against the target until the start of this creature’s next turn. SKIRMISHER To create a skirmisher foe, reduce a creature’s AC by 2 or reduce their hit points by 20 percent. Each of the creature’s speeds increases by 20 feet. Then give the creature any of the following powers: Nimble (Trait). This creature ignores difficult terrain. Careful Steps (Bonus Action). This creature’s movement does not provoke opportunity attacks until the end of their turn. Knock Back (Trait). When this creature hits a target with an attack, they can choose to push the target 5 feet away from them. If this creature is CR 4 or higher, the target must also succeed on a Strength saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) or be knocked prone. You might also wish to consider the Quick Step power found in the artillery section above. MONSTER DIFFICULTY DIALS Balancing combat encounters is notoriously difficult. Different groups of characters can bring very different capabilities to each battle, even at the same level. However, because monsters as they are typically presented are the average of their type, you can adjust the averages to subtly or dramatically change the difficulty of a given monster or group of monsters. By turning these “difficulty dials” for monsters, you can easily shift the tone of combat even in the middle of a battle. “HIT POINT” DIAL Hit points given for monsters are the average of their Hit Dice. This means you can adjust hit points within the minimum and maximum of a monster’s Hit Dice formula based on the individual story for that particular monster, the current pacing of the battle, or both. For example, an average ogre has 59 hit points from 7d10 + 21 Hit Dice. This means a weak ogre might have as few as 28 hit points, while a particularly strong ogre might have 91. This lets you easily set up fights in which minion ogres might have fewer hit points while boss ogres have more. (As an even lazier rule of thumb, you can halve or double a monster’s average hit points to give you a weaker or stronger version of that monster.) You can turn this dial before a battle begins or even during the battle. If a battle drags, reduce the hit points of a monster to get them out of the fight earlier. If a battle feels as if it will be over too quickly, increase the monster’s hit points to make them hold up longer. Start with average hit points, and then turn the hit point dial one way or the other whenever doing so can make the game more fun. “NUMBER OF MONSTERS” DIAL The “number of monsters in a battle” dial alters combat challenge the most dramatically of all the dials—but because it’s so clearly visible to players, this dial is also sometimes difficult to change during a fight. If circumstances allow for it, some monsters might flee or automatically fall depending on the events of a fight. Undead might break if their necromancer master is killed, and many creatures know to flee a fight they can’t win. Other times, more monsters might enter the fray in a second wave if the first wave isn’t standing up to the characters. (“Building and Running Boss Monsters” on page 31 talks more about running monsters in waves.) When developing a combat encounter in which you think you might turn this dial, consider beforehand how monsters might leave the battle or how other monsters might join the fight as reinforcements in a realistic way. “DAMAGE” DIAL Increasing the amount of damage a monster deals on each attack increases the monster’s threat and can make a dull fight more fun. In the same way, decreasing monster damage can help prevent a fight from becoming overwhelming if the characters are having trouble. The static damage value noted in a monster’s stat block represents the average of the damage formula for the monster’s attack. If you use average damage, you can adjust the damage based on that formula. For example, an ogre deals 13 (2d8 + 4) bludgeoning damage with their Greatclub attack, so you can set this damage at anywhere from 6 to 20 and still be within the range of what you might roll. If you’re a DM who rolls for damage, you can also turn the damage dial up by adding one or more additional damage dice. If you like, you can have an in-game reason for this increase. Perhaps an ogre sets their club on fire to deal an extra 4 (1d8) or 7 (2d6) fire damage. Or a particularly dangerous vampire with an unholy longsword might deal an extra 27 (6d8) necrotic damage if you so choose. Adding these kinds of effects to a monster’s attack is an excellent way of increasing a monster’s threat in a way the players can clearly understand—and it has no upper limit. “NUMBER OF ATTACKS” DIAL Increasing or decreasing the number of attacks a monster makes has a larger effect on their threat than increasing their damage. You can increase a monster’s number of attacks if they’re badly threatened by the characters, just as you can reduce their attacks if the characters are having a hard time. An angry ogre left alone after their friends have fallen to the heroes might start swinging their club twice per Attack action instead of once. Single creatures facing an entire party of adventurers often benefit from increasing their number of attacks. MIX AND MATCH You can turn any or all of these dials to tune a combat encounter and bring the most excitement to your game. Don’t turn the dials just to make every battle harder, though. Sometimes cutting through great swaths of easy monsters is exactly the sort of situation players love. Turning several dials together can change combat dramatically, helping to keep things feeling fresh. For example, a group of starving ogres might be weakened (lowering the hit point dial) but also frenzied in combat (turning up the attack dial). By adjusting these dials when designing encounters and during your game, you can keep the pacing of combat exciting and fun. (This section originally appeared in The Lazy DM’s Companion.) 27 BUILDING AND RUNNING LEGENDARY MONSTERS The overlap between legendary monsters and boss monsters (talked about in “Building and Running Boss Monsters,” page 31) is extensive. At anywhere above roughly challenge rating 10, legendary creatures become the most prominent bosses, able to defend themselves against any group of characters of higher than 5th level. This section provides tools for GMs to build or improvise legendary monsters, giving foes the ability to survive and thrive in battle against powerful characters. BEST ABOVE 5TH LEVEL Typically, legendary monsters aren’t needed when facing characters of 1st to 4th level. The capabilities of legendary foes only start to matter when characters get access to spells and features that can take out a creature with one failed saving throw, and that grant multiple attacks in a single turn. Against such higher-challenge player character opponents, legendary monsters need extra offturn actions and resistances to feel like a significant threat. CORE COMPONENTS OF A LEGENDARY MONSTER Legendary monsters typically have two components that separate them from normal monsters: the Legendary Resistance trait, and legendary actions. Legendary Resistance helps a creature avoid situations where a single failed saving throw takes them out of the fight. Legendary actions help a single monster better manage the action economy against multiple opponents. (See “Understanding the Action Economy,” page 42, for more on that topic.) The sections below talk about ways to utilize Legendary Resistance and legendary actions. But you can use those ideas to build a quick and easy legendary monster in just two steps. First, give a creature one to three uses of Legendary Resistance: Legendary Resistance. If this creature fails a saving throw, they can choose to succeed instead. Second, give the creature three legendary actions. You can build legendary actions yourself (including advanced legendary actions, talked about below), borrow them from other legendary monsters, or use the following basic legendary actions: 28 Quick Movement. This creature can move their speed without provoking opportunity attacks. Legendary Attack. This creature makes one melee or ranged attack using their lowest-damage attack option. Blast (Costs 2 Actions). This creature can target up to three creatures within a 20-foot radius, a 60-foot cone, or a 100-foot line that is 5 feet wide. Each target must make a Dexterity, Constitution, or Wisdom saving throw (your choice; DC = 12 + 1/2 CR), taking 4 × CR damage of a type appropriate for this creature on a failed save, or half as much damage on a successful one. Any of these basic legendary actions can help a foe hit harder than they do with their regular stat block, letting them hold their own as a single combatant against a group of characters. LAIR ACTIONS AND REGIONAL EFFECTS Some legendary monsters also have lair actions they can use if fought in their lair, and might have regional effects they can use in the area around their lair. “Creating Lair Actions,” page 36, talks more about that topic, and regional effects can be easily improvised based on a particular monster’s story. LEGENDARY RESISTANCE The Legendary Resistance trait gives legendary monsters a way to deal with a single instance of a “save or suck” feature—any attack by a character that can take a foe out of a fight with a failed saving throw. Legendary Resistance is like a countdown timer for the players, who can pick away at that resistance by threatening to impose debilitating effects that force a foe to burn their resistance to avoid those effects. For this reason, making it clear how many uses of Legendary Resistance a creature has, and how many are expended, can help the players see another path to victory other than beating down a foe’s hit points. Most legendary monsters have three uses of Legendary Resistance. Assuming that a creature has a 50/50 chance of succeeding on a saving throw, the characters might need to use four to eight spells or effects requiring a save before one lands with full effect. As such, if you want the characters to have a better chance of burning a legendary monster down, you might give that monster only one or two uses of Legendary Resistance. TRACKING LEGENDARY RESISTANCE Adding an in-world description that represents a creature’s ability to make use of Legendary Resistance can also be useful, as it lets the players easily track how many uses a foe has left. A powerful wizard might have three unique Ioun stones floating around their head, which they can sacrifice one by one to succeed on a failed saving throw. A demon might have three fiery brands on their chest, each one losing its red-hot glow as the fiend expends their Legendary Resistance. If you want to make things a little more interesting, the devices channeling Legendary Resistance might be objects the characters can target. If a demon prince is protected by four pillars imbued with magical power, shattering those pillars removes those protections. This still reduces the risk of the characters burning down a boss in 1 round, even as it gives them clear actions they can take to break through the boss’s defenses. attacks. To thwart this, a beholder might employ guards who don’t need to see to attack, whether they have the blindsight trait or make use of magic. Movement is likewise a great defense against features and magic that can pin a legendary monster down. The monster might teleport (which has a chance to bypass forcecage) or move without provoking opportunity attacks. (As noted above, such movement works well as a legendary action.) FRIENDS ARE THE BEST DEFENSE ALTERNATIVES TO LEGENDARY RESISTANCE If you’re not a fan of Legendary Resistance, you might instead allow a foe to take psychic damage to remove debilitating conditions and other effects—perhaps a number of d6s equal to one-half the foe’s CR. Alternatively, you can make the concept of Legendary Resistance more interesting by having each successful saving throw impose a cost on a creature. For example, each time a foe uses Legendary Resistance, they might lose one use of a legendary action in the current round. The Bloody Legendary Resistance trait in “Monster Powers” (page 15) has a similar theme. Just make sure it’s clear to the players what’s going on so they can see and understand the price the boss monster is paying for shaking off the characters’ attacks. ZOE BADINI WHAT LEGENDARY RESISTANCE DOESN’T PROTECT AGAINST Not all “save or suck” effects can be avoided with Legendary Resistance. Even legendary monsters might get physically pinned down by features and effects that don’t allow for a saving throw, or by effects that change the combat environment. Hindering the senses of a creature with spells such as darkness or fog cloud can make them much less effective in a fight. Other features like the forcecage spell or the monk’s Stunning Strike attack can bypass or burn through Legendary Resistance quickly. It’s worth considering other ways that a legendary creature can deal with such features and magic. For example, a beholder relies on eye rays to target creatures with their formidable magic. So if a beholder is engulfed in magical darkness—or if the creatures they want to target with their eye rays are—they can’t use those potent Any single monster, legendary or not, finds themself at a disadvantage against a group of characters. As such, one of the best defenses for a legendary foe is the presence of other foes fighting the characters. If a legendary dragon gets taken out with a maze spell, for example, their stone golem servant can punch the caster of maze in the face until their concentration breaks. Good synergistic allies can help legendary monsters offensively as well, by locking down the characters or threatening backline attackers while their legendary leader finds a better position. Adding more monsters can complicate a fight, however, so be prepared for a longer battle the more creatures the battle involves. Adding more monsters is typically important when building encounters for five or more characters of higher levels. BALANCING LEGENDARY ACTIONS Legendary actions give a monster a boost in the action economy of a fight (see “Understanding the Action Economy” on page 42), letting them deal more consistent damage. Instead of acting only on their turn, a legendary monster can act up to three times between other creatures’ turns with specific legendary actions. Sometimes these actions are just single attacks. Other times, they involve movement or big area effects. By design, legendary monsters aren’t meant to deal more damage than their nonlegendary counterparts at the same challenge rating. The damage a legendary creature can do is divided up among the actions they take on their turn and their legendary actions, but it’s the same overall damage per round. But because legendary monsters are intended to be something special, doing just the appropriate damage for their challenge rating might not be enough. This is because even with legendary actions and Legendary Resistance, a single big boss monster is still at a disadvantage against a group of characters who pour their wrath out against that boss before targeting any other foes. If you’re designing or improvising a legendary monster, don’t worry if their overall damage output goes above the standard for their challenge rating—as they likely need the help. For example, you might want to create a legendary barbed devil, giving them three legendary 29 action Claw attacks built on their standard-action attack. Normally, you’d think about reducing the damage output for the Claw attack so that the devil’s overall damage per round stays the same. But you’re probably better off not worrying about rebalancing damage across all the creature’s actions and legendary actions. Your barbed devil boss’s damage output will go beyond their challenge rating, but that extra damage gives them a needed edge. ADVANCED LEGENDARY ACTIONS In addition to the legendary actions in the Monster Manual and other books that you can use or draw inspiration from, you can create and customize more advanced legendary actions that fit a foe’s theme and tactics. When default actions focused on simply moving and attacking might not fit the story of a monster, advanced legendary actions can focus on how a boss fight unfolds, factoring in how characters typically behave and how the situation escalates. Three of the following advanced legendary action setups are drawn from the “action-oriented monster” concepts introduced by Matt Colville on his YouTube series “Running the Game,” and as seen in monsters published by MCDM Productions. Specific features suitable for some of the other setups here can be found in the monster powers presented in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22). AURA CONTROL As talked about in “Understanding the Action Economy” on page 42, auras are an incredibly powerful way to scale up any creature based on the number of opponents they face. Using legendary actions to alter and shift an aura is an excellent way to shake up a battle against a legendary creature. An aura might increase the amount of damage it deals at certain points in the fight, scaling up as the battle goes longer. A legendary creature might extend the effect of their aura, making it larger and threatening more characters as a result. Or a boss might change the shape of an aura, creating a donut-shaped ring that leaves characters at its center within the boss’s melee reach, and characters outside being shredded by the aura’s power. COMMANDING ALLIES A legendary monster who operates with minions can make great use of legendary actions that help those minions get into positions and make free attacks. Alternatively, a legendary boss might cause their minions to explode or make one final sacrificial blow. Commanding bosses are all about giving their minions a free move, a free attack, or both. EXPLODING Near the end of a fight, the characters often have the upper hand. The boss monster’s hit points are down. Their 30 big attacks are spent. This is the perfect point to reveal a legendary monster’s final action—the explosion. The explosion is a single big damaging move. It might be a dragon recharging their breath weapon and getting to use it for free. It might be a mage hurling fire in a massive ring to burn everyone around them. It might be a fast and furious sword wielder making a final charge across the battlefield to score a big hit against every target they pass. The explosion is a legendary monster’s final, desperate blow. It’s their ticking time bomb. Often, this sort of final attack takes two or three legendary actions. INITIAL POSITIONING At the start of a fight, an advanced legendary action might help a monster move into an optimal initial position. Characters sometimes find ways to get into advantageous or defensive positions early in the battle, meaning a legendary monster likewise needs a boon when it comes to initial positioning. This might be the standard legendary action providing an extra move that doesn’t provoke opportunity attacks. Or it might be something more magical like teleportation. The key is that the action lets a foe get into a position where they can be effective at doing what they’re intended to do. Getting into position usually requires only one legendary action. REPOSITIONING Even if they have optimal initial positioning, a legendary monster eventually needs a way to reposition once a battle has commenced. In the middle of a fight, the characters might have a boss pinned down with melee attackers surrounding them and ranged attackers at a safe distance. The characters have the boss under control—but that isn’t much fun for a dynamic and dangerous fight. So you can give a legendary monster a way to circumvent that control in fun and dangerous ways. For example, a legendary monster might quickly shift to switch places with one of their minions. They might burrow beneath the ground, leaving a dangerous sinkhole behind. They might sweep their wings, knocking any nearby characters prone, then fly to a new position. They might teleport, leaving behind a blast of fire in their wake. A legendary action focused on repositioning should be more than the standard move without provoking opportunity attacks. It’s a move plus a kick to the face on the way out. This kind of repositioning should take one or two legendary actions. TRANSFORMATION When it makes sense for their story, some legendary monsters transform. A humanoid might take on their werewolf form at some point during a battle, then transform again into a huge wolf. A vampire might start off as a humanoid, become a swarm of bats, and finally take the form of a towering batlike monstrosity. Each of these transformations can include new features and attacks based on the new form. “Evolving Monsters” on page 62 has more thoughts and ideas on this topic. BUILDING AND RUNNING BOSS MONSTERS When thinking about combat against boss monsters, we often think about what we see in movies, read in books, or watch on TV. During staged climactic encounters, the tide of battle turns one way, then the other, then back again. The hero gets a strong start, then suddenly loses ground, then gains the upper hand, then loses it again. Suddenly they’re on their back, a sword at their throat, and it feels as though all is lost—until the protagonist gets that final surge, knocks the blade aside, and finishes off the villain with a masterful flourish. Tabletop RPGs seldom follow this model. Instead, characters see the boss monster, wait for about half a line of monologue, then unleash every single class feature, magic item, and spell they possess to destroy the boss as fast as possible. They use every “save or suck” spell they can cast. They use every single stunning strike they can inflict. Anything to get that boss down fast. Without careful planning on the GM’s part, these kinds of all-in attacks usually work. Sometimes this is great fun. The players love it, we laugh about it, and we move on. But sometimes such spiked victories feel hollow. They miss the pacing and feeling we’d hoped for. When you spend your entire campaign building up to the final encounter with the vampire mastermind, only for the characters to pin that mastermind down in a beam of sunlight and smite them to death without a single counterattack, it can feel as though all that work was for nothing. Even the players who chose to have their characters pin the boss down might feel as if they were robbed. As such, it’s worth paying attention to boss fights in your games, to ensure they meet the intention of the story and the pacing you want. THE ONE ENCOUNTER WORTH FULLY PREPARING As GMs, we can often get away without preparing individual combat encounters for most of an adventure or campaign, building our encounters during the game based on the locations and situation in an adventure. (“Choosing Monsters Based on the Story,” page 113, talks about one approach to this kind of encounter design). Boss fights, however, are worth the time and effort it takes to prepare them. Boss battles are often the final peak of an adventure, or of an entire campaign. We want our games to have those peaks and valleys—the upward and downward beats that make play interesting and fun. But without careful preparation, even legendary monsters can go down before they’ve had a chance to threaten the characters, turning what should be a major high point into something much flatter. RISING DIFFICULTY When thinking about getting the most out of boss monsters and boss battles in your 5e games, the first thing to understand is that protecting bosses typically only starts to be a problem at 5th level and above. From 1st to 4th level in 5e, characters rarely have the capability and resources to destroy or incapacitate bosses as quickly as they do at higher levels. The higher the level of the characters, the easier it is for them to pin down or destroy bosses with ease, negating the full challenge the boss is intended to represent. Though some of the following techniques might prove useful at all levels, GMs typically don’t need to worry about them when the characters are just starting out. RESOURCE ATTRITION Many GMs are used to the idea of running the characters through numerous battles before they face the boss, ensuring that they’ve burned down their spells, Hit Dice, and limited-use class features before the final battle. This approach can help ensure that the heroes don’t come into the fight fully ready to unleash their most powerful combat features in the first round. But it can also rob the players of enjoying the full range of their capabilities the one time they’d love to have everything on hand. As such, be careful not to weaken the characters so much that their favorite features are long gone before the climactic fight begins. RUNNING WAVES OF COMBATANTS Whenever a boss reveals themself, particularly if they make themself vulnerable at the start of combat, the characters most likely aim everything they have on the boss first. This can be easily prevented by ensuring that the boss simply isn’t there, or at least isn’t reachable when combat begins. Instead of starting a battle with the boss in combat, consider running waves of combatants before the boss shows up. Each of these waves might be a hard or even deadly encounter, with some overlap between the waves as befits the situation and the difficulty of the encounter as it plays out. For example, the first wave of a boss fight might involve several creatures roughly equivalent in number and power to the characters. This first wave gets the characters moving around, establishing positions, and using some of their resources to control or take out these “normal” foes. A second wave might involve huge numbers of weak monsters. A horde of fifty skeletons might charge a group of 8th-level heroes, firing arrows and swinging swords. 31 This gives the characters a chance to go wild with areaeffect or crowd-control spells or features, blowing away huge swaths of their foes. Another wave might include a small number of big brutes. Individual crowd-control features might lock those foes down, or the characters can focus their high-damage attacks on them. Only then comes the boss—floating down from their shielded throne, flying in through a side passage, teleporting in, manifesting as a swarm of bats, or what have you. At this point, the characters are spread all over the battlefield. They’re wounded. They’ve expended resources. They’re not in an ideal situation to drop everything they have on the boss anymore. And depending on how difficult things appear, the boss might even arrive right in the middle of the previous wave, forcing the characters to either switch targets or to continue fighting the threat in front of them. Running waves of combatants, either one after the other or having them overlap, is a powerhouse tool to threaten even the most commanding characters. You don’t need to use waves for every boss battle, but the more powerful the characters become, the more that doing so can help you maximize those upward and downward beats in your final confrontations. MITIGATING DAMAGE SPIKES No matter how powerful they are, most bosses need protection to survive an encounter with the characters. Because they’re the most sought-after target in combat, they often need features or magic to help them survive a barrage of attacks long enough to do boss things. One great threat faced by bosses are huge spikes of damage, delivered by paladins with Divine Smite, fighters with Action Surge, and other characters with a knack for unloading tremendous amounts of damage in a single turn. Adding more hit points to a boss certainly helps with this problem, and is the easiest way to mitigate tremendous amounts of damage. But there are other ways. One trick is to give the boss the capability to transfer half the damage they take to willing allies—or even all the damage. A lich might shunt damage into the iron golems guarding them. A cult fanatic might transfer damage to a number of cultist minions. An ancient brass dragon might direct damage to a horde of fire elemental servants. The Fanaticism trait in “Monster Powers” (page 15) is an example of this approach. It helps to have an in-world explanation for such a feature, with one example being the control amulet of a shield guardian. A blood-pact ritual undertaken by the cult fanatic might have the same effect. It also helps to telegraph this in-world connection to the players so they can make choices about how to respond. Taking out the minions first might be tactically advantageous, with their lower Armor Class and closer physical proximity. Clarify these advantageous tactics, and nudge players away from their instinctive drive to focus on the boss. 32 USING LEGENDARY RESISTANCE Love it or hate it, Legendary Resistance is one of the strongest ways to protect boss monsters from “save or suck” spells, or effects that allow a single attack to shut down a boss’s actions for a round or more. Most 5e legendary monsters have Legendary Resistance, often usable three times per day. If you have a boss you want to protect, giving them Legendary Resistance covers 90 percent of the effects that might pin them down and prevent them from doing their cool boss things—a dragon’s breath weapon, a lich’s deadly magic, a vampire’s life-draining bite, and so on. Legendary Resistance (3/Day). If this creature fails a saving throw, they can choose to succeed instead. “Building and Running Legendary Monsters,” page 28, offers lots of thoughts on Legendary Resistance, including having a legendary boss manifest that trait physically so the players recognize how many uses are left. It also talks about ways to alter or fine-tune Legendary Resistance with additional effects. HANDLING THE MOST POWERFUL FEATURES Many features and attacks in 5e bypass Legendary Resistance. This includes features that force a creature to make an ability check instead of a saving throw, making grappling and pinning down smaller foes such as liches a common tactic. Likewise, high-level attacks such as the forcecage spell can easily pin down a boss and remove their ability to threaten the characters with no saving throw at all. And though features such as a monk’s Stunning Strike don’t bypass Legendary Resistance, being able to use such features on attack after attack means that a monk might burn out all of a boss monster’s uses of Legendary Resistance in a single turn. You can gauge if such situations are a problem in your game by running early boss monsters against the characters—even copies of the main boss. An evil wizard might create a simulacrum to harry the characters, or a lich might attack knowing that while their soul remains safely stored away elsewhere, their body being destroyed is of no consequence. A vampire can test the characters, then simply return to their coffin if defeated. These preliminary boss test fights can tell you a lot about what the characters bring to the table when facing a boss. Sometimes you simply won’t worry about the party’s arsenal of irresistible effects, instead letting the characters take control of the situation with their cool class features and magic. But if you do feel as though these features get in the way of the boss fulfilling their duty to the story and their own place in the world, it’s worth considering how the boss can react to such situations. Do they have the magical means to escape a forcecage spell? Can they deal with multiple stunning strikes in a row? Can they escape a grapple with misty step used as a legendary action? Be wary of giving a boss monster the ability to circumvent the characters’ powerful features just because you don’t want those features used. Be a fan of the characters and the cool stuff they can do. But you can have a boss monster bypass powerful features as long as doing so still leaves the game fun for the players. RUN MULTIPLE BOSSES Another common technique for protecting your boss monster is to have more than one. Three hags might work together in a single battle, benefiting from their coven magic, and even potentially sharing a pool of uses of Legendary Resistance. Likewise, a pair of twin black dragons makes for a much stronger encounter than just one. Spreading the hatred of a boss to more than one boss in a single encounter helps avoid the scenario of the characters focusing everything on a single target. As one boss works to protect themself, the other boss can come forward, unleashing their devastating attacks. Some bosses might be able to make multiple copies of themselves, using the simulacrum spell or similar magic. Other bosses might have unique power that lets them form three separate copies of themselves, perhaps sharing a single hit point pool but having multiple actions and multiple physical representations. CONDENSING LEGENDARY ACTIONS When running multiple bosses, avoid including more than one with legendary actions in a single battle. Legendary actions are intended to offset the problems with the action economy that arise from having multiple characters take on a single foe. (“Understanding the Action Economy,” page 42, has more on this topic.) If you have multiple bosses, those bosses often don’t need legendary actions to keep up with the characters, allowing you to instead compress those legendary actions down into normal actions. Because legendary actions are factored into a monster’s challenge rating, if you don’t want to add those legendary actions to a monster’s normal actions, you can instead increase the damage of their regular attacks. Using an adult black dragon as an example, you can add a Tail attack and a Wing attack, or three Tail attacks, to their Multiattack action instead of taking those extra attacks as legendary actions. Or if you want a battle with fewer attack rolls, you might instead add 15 damage to the dragon’s Claw and Bite attacks (the same amount of damage dealt by three legendary action Tail attacks per round) to keep their damage output where it should be. servants don’t worry about fighting in a cavern filled with lava. Liches have no problem fighting in chambers filled with poison gas. As such, the environment of a boss’s sanctum can have a huge effect on the challenge they bring to a battle. Pools of lava, places to fly, statues to topple over, glyphs of warding—these kinds of features can easily turn the tide of a battle in favor of a boss. Bosses might have ways they can use the environment to shake up how the players think about the battle. For example, a powerful lich might use glyph-scribed obelisks in their lair that allow them to have more than one concentration spell active at a time. This powerful spellcaster might have one pillar letting them concentrate on greater invisibility, another pillar granting them a globe of invulnerability, another surrounding them in a cloudkill, and a fourth granting them flight with a fly spell. Each pillar might have an AC of 15 and 50 hit points, giving the characters multiple tactical goals as they decide whether to destroy the pillars so that the lich loses those spells. KEEPING YOUR HANDS ON THE DIALS “Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27 talks about how to make useful modifications to monsters right in the middle of combat. Running boss battles is one of the best times to have your hands on those dials, letting you easily adjust the threat level to keep the characters and the players on their toes. When running waves of combatants, you have a firm hand on the “Number of Monsters” dial. When the second wave comes out, you can decide how many monsters join that wave based on the outcome of the first wave. Did the first wave take longer than expected and push the characters hard? Reduce the monsters in the second wave, or remove that wave completely. Did the characters steamroll the first wave? Add a few more foes. Turning the “Hit Point” dial likewise tunes the entire battle. When any of the monsters, including the boss, have overstayed their welcome, turn their hit points down and let them fall on the next hit. Did the characters mow through monsters faster than expected? Consider turning the hit point dial up, especially for the boss. Typically, you want a boss to stick around for at least 3 rounds. Less than that, and the players never get to see what the boss can do. But a battle that goes on forever can become boring. ADDING ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Most often, boss monsters battle in environments that serve their needs. A red dragon and their fire elemental 33 BUILDING SPELLCASTING MONSTERS Magic is a cornerstone of most fantasy RPG campaigns, and nothing helps bring the magic of a world to life better than having foes pound the characters with spells and other magical attacks during combat. Many of the game’s creatures already pack a magical punch, but adding spellcasting to foes who don’t already have it can be great fun. However, the baseline power of spellcasting means that doing so requires some planning. A creature’s general level of challenge for a party can be assessed in many different ways. But when adding spellcasting to existing stat blocks, the mechanics to focus on are damage per round, followed by what conditions can be imposed by a spell. After you’ve chosen magic for a spellcasting creature, “Running Spellcasting Monsters” on page 58 has great advice for working with that magic. SPELL DAMAGE DAMAGE AND TARGETING 34 Every combat-focused creature deals a certain amount of damage per round with their best attacks—often the sum total of all attacks in the Multiattack action. When adding spellcasting to a creature, you want to focus on that total damage-per-round number, choosing spells that deal roughly that same amount of damage to all their targets. For example, a doppelganger’s Multiattack lets them deal an average of 14 damage with their Bite and Claw attacks, so giving them spellcasting that deals 14 damage makes a nice surprise for the characters and doesn’t change the doppelganger’s threat level. If a creature has only one primary attack per round or deals relatively low damage with Multiattack, a singletarget spell is a great fit. But if a creature’s damage-perround output is high and is spread out across multiple attacks, look for a spell that allows multiple targets or deals damage to creatures in an area. A CR 2 gargoyle dealing a relatively low 10 damage per round is equally fine with an area spell or a single-target spell dealing 10 damage. But a CR 2 centaur hits harder with 20 damage per round, meaning they work better with an area-effect spell dealing that much damage in total to all its targets. Using a single-target spell that deals the same damage as all of a high-damage creature’s weapon attacks can skew a monster’s effective challenge by making them more likely to drop a character with one attack. SAVE VS. ATTACK A key component to calculating creature challenge ratings is that attacks, spells, and special features are always assumed to deal full average damage. A monster’s attacks are always assumed to hit, and the characters are always assumed to fail their saving throws against a monster’s spells and special features. But one area where you want to keep an eye on this is spells that deal half as much damage on a successful saving throw. Replacing a creature’s weapon attacks with spells that deal partial damage on a failed save is akin to deciding that those weapon attacks deal partial damage on a miss. So be careful that dealing default damage round after round doesn’t make a creature a bit too sweet in combat. AREA EFFECTS For spells that deal damage in an area, assumptions need to be made about how many targets those area-affect spells will hit. A good general guideline is to assume that most areas of effect will target two creatures on average. Extra-large areas such as the 60-foot radius of a freezing sphere or sunburst spell will target three creatures. CHOOSING DAMAGE-DEALING SPELLS For characters, the damage output of spells can sometimes be a complex curve, tying into caster level and the level of the spell slot used to cast. When building JACKIE MUSTO Alongside hit points, damage output per round is the most significant factor in determining the relative challenge of combat-focused creatures. (This can be seen in many NPC stat blocks, where spellcasters slinging high-damage evocation magic can have a higher challenge rating than diviners or enchanters, even when casting at the same level.) When building a spellcasting foe from an existing stat block, start by assessing the foe’s damage output (perhaps with reference to the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table on page 6 of “Building a Quick Monster”). Then think about how to best rework that output in spell form. spellcasting foes for combat, you can usually focus on baseline damage—5 (1d10) for eldritch blast or firebolt; 10 (3d6) for burning hands; 7 (2d6) for each scorching ray; 28 (8d6) for fireball or lightning bolt; and so on. That said, when trying to pick a spell appropriate to a creature’s normal damage output, don’t forget that adjusting that damage is just as easy as adding the spell in the first place. Want to build an inferno ettin who casts fireball? Look at the ettin’s normal damage output of 28 points, then make sure their fireball spell deals about 14 damage (4d6 or 3d8) to each of its two expected targets. SPELL CONDITIONS In most cases, conditions in combat make the creatures dishing them out more effective in a fight, by reducing the effectiveness of the characters while hindered by those conditions. Adding spells that impose conditions to existing stat blocks is thus a slightly less straightforward process than swapping weapon damage for magical damage. The effectiveness of a particular condition can vary drastically depending on what type of character it’s imposed on, and on how enemies might take advantage of the condition’s effects. A fighter who’s been poisoned takes a big hit in combat as disadvantage penalizes their attack rolls, even as their wizard ally casting spells that require saving throws can all but ignore the condition. Likewise, sleep is a 1st-level spell, and so might seem an easy option to add to any relatively low-CR creature. But a foe who casts sleep in order to run away from the characters is a very different threat than one who does so to let their melee-focused allies run in and start auto-critting unconscious heroes. CONDITIONS AS THREAT When looking at spells that impose conditions, think about those conditions as a kind of sliding scale of threat, from least to most significant. For the purpose of this approach, ignore grappled as a condition of its own, focusing instead on the restrained condition that being grappled typically imposes. Also ignore exhaustion, which is a special-case condition that should generally not be imposed during combat. Charmed, Deafened, Poisoned, and Prone. These weakest conditions are the easiest ones to make use of for spellcasting monsters. Each has the ability to take a fight in an unexpected direction by hindering characters, but none is powerful enough to upend a battle on its own because none can take a character completely out of the fight. Blinded, Frightened, and Restrained. These conditions are a stronger threat, representing a greater ability to hinder characters in combat. All can limit the actions or movement of characters, even as they also penalize combat rolls. Incapacitated, Paralyzed, Petrified, Stunned, and Unconscious. At the apex of the hierarchy of how badly conditions can mess with characters, these five stand alone. Each can take a character completely out of a fight, shifting the overall balance of an encounter for a number of rounds—or even for the entire battle. Conditions and Duration. When assessing any spell that imposes a condition, consider the different feel of spells that do so for 1 round or that allow a repeated saving throw to end the condition, as compared to spells whose imposed conditions have a long duration and no repeated save. Long-duration conditions with no automatic opportunity to end them can be vexing for players if they cause characters to sit out multiple turns. Even low-level spells such as charm person or sleep can feel quite different when it’s the characters using them to turn the tide against a mob of foes, and when it’s a single spellcasting monster using them to make multiple characters sit on the sidelines during a fight. CONDITIONS AS REVERSE BENEFITS The way combat changes across a broad range of character levels makes it impossible to come up with any hard-andfast rule for how much damage a particular condition is equivalent to in a fight. So instead, think about conditions imposed by spells as granting benefits to the enemy side akin to adjusting foes before combat. (“Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27 talks about how to adjust encounters on the fly.) For example, conditions that impose penalties on characters’ attack rolls decrease their chances of hitting foes. So giving a creature a spell that imposes the frightened or poisoned condition is effectively the same as dialing up the Armor Class of the foes in an encounter. Conditions that limit characters’ actions have the same general effect on the action economy in a fight as giving the enemy side additional actions, so think of spells that impose the charmed or stunned condition as equivalent to adding extra attacks to the enemy side. At the high end of the condition hierarchy, being able to render characters incapacitated in any way can be thought of as akin to having more foes on the enemy side, working with the idea that a character taken out of the fight for a round is the same as a character spending that round fighting an additional “virtual foe.” CHECK SPELLCASTING ABILITY As a final step in building spellcasting creatures, have a look at a stat block’s spellcasting ability scores. The math underlying a creature’s relative challenge in combat makes the assumption that a creature is using one of their best abilities for their go-to attacks. So if you add spellcasting to a creature whose Intelligence, Wisdom, or Charisma are all low compared to the Strength or Dexterity fueling their weapon attacks, bump up one of those mental abilities so the creature’s spell save DC and spell attack modifier aren’t lagging behind their other attacks. Alternatively, you can easily create a house rule stating that creatures known more for brawn than brains who channel spell magic innately can use Constitution as their spellcasting ability. 35 CREATING LAIR ACTIONS When a legendary creature inhabits a location, their presence can change the environment in which they live. After a hag moves into a forest, the trees become twisted, brambles grow, shadows darken, and the air becomes foul and oppressive. In the lair of a white dragon, bitter winds howl through icy tunnels, whose walls reflect the frozen visages of the dragon’s many victims. From a narrative perspective, lair actions allow us to tell the story of a formidable creature and their environment. The best lair actions capture the creature’s essence, and how that essence permeates and alters the world around them. From a mechanical perspective, lair actions provide GMs with an additional set of combat options, allowing greater flexibility in focusing on the characters and creating a higher challenge level. LEGENDARY IN NATURE In most cases, only exceptional creatures should have lair actions. This represents the fact that it takes a particularly powerful or special creature to alter their surroundings in such a formidable way. However, a good story can explain a lesser threat having access to lair actions, as with an alchemist in a workshop with potions brewing, each of which can explode each round to affect combatants. When a creature is legendary, take care to ensure that lair actions feel different from legendary actions. Legendary actions represent what a creature can do directly with their body and their inherent capabilities. Lair actions are external, representing the interplay between the creature and their surroundings. (“Building and Running Legendary Monsters” on page 28 has advice for creating legendary actions.) THE IMPORTANCE OF A LAIR Before you can add effective lair actions to a creature, take the time to understand the key aspects of that creature, and what kind of environment their lair should be. Thinking through the connection between creature and lair allows you to weave lair actions convincingly into a story. You can get lair ideas by reviewing a monster’s lore, the myths of similar creatures, and the larger story and setting of your campaign. Consider the following examples: • A fire elemental could live in a lava-filled cavern, but could also inhabit a burning forest. • A black dragon has transformed a valley into a fetid swamp, with all its former beauty turned to rot and undeath. • A treant lord has deep roots that influence all the plant life in an area. Even creatures living in the trees and soil obey this powerful leader. • An egotistical giant has collected trophies in a vast museum, with the spirits of creatures they’ve conquered manifesting through each of those displays. 36 • A legendary undead pirate captain dwells in a shipwreck upon a rocky coastline. Waves, sand, and rain all obey the pirate’s whims, even as their undead crew does battle. (“Building Engaging Environments” on page 79 also talks about the kinds of engaging elements that can factor into the design of lair actions.) USING LAIR ACTIONS When in their lair, a legendary creature can use one of their lair actions on initiative count 20 (losing initiative ties). They can’t use a lair action when incapacitated, or on their first turn of combat if they were surprised. TYPES OF LAIR ACTIONS Most creatures have three to four lair actions, which provide one of three types of benefits. When creating lair actions, choose the benefit type that fits what a creature needs in each round of combat. Damage. Lair actions might represent bursts of fire or other elemental energy, brambles tearing at heroes, spectral swords, or other effects. Damaging lair actions allow a GM to target the characters outside of a creature’s normal turn, keeping a higher level of pressure on the heroes. By lessening the impact of conditions or other effects (other than being incapacitated), damaging lair actions make a solo creature’s overall damage output more reliable. Control or Impede. A column of stone or a stalactite might deal damage as it falls, but its primary benefit is pinning a hero down and taking them out of the fight for a time. Fumes from a swamp or a pool of acid might poison heroes. Grasping skeletal hands or vines can grapple and restrain characters. These types of lair actions limit the characters’ effectiveness, allowing a creature to evade blows or to isolate and pick off foes more easily. Excessive control hurts fun, however, so limit your use of these types of lair actions to make them stand out as infrequent but significant challenges. Protection. Protective lair actions shield, heal, or enhance a creature, providing them with important survival capabilities they might otherwise lack. For example, an artificer’s lab might contain a clockworkgenerated shield that grants temporary hit points or heals wounds. A fire elemental might be able to teleport from one pool of fire to another to keep away from the characters. Obscuring gases or crashing waves can occlude a battlefield, imposing disadvantage on attack rolls. (“Building and Running Boss Monsters” on page 31 has thoughts on protecting important monsters that make great inspiration for lair actions.) TACTICS When choosing which lair actions to use during combat, think about whether damage, control, or protection are more effective in any given round. Damage and control work particularly well early in combat, causing the players to adjust their plans and break out of typical attack routines. The heroes might be forced to expend resources or heal an ally rather than make an attack, or might have to contend with conditions that leave them unable to reach their target. Protection works well when a foe is pinned down in their lair, helping them make it through tough moments—or to escape those moments entirely. Such actions surprise the characters, showing the full range of their foe’s resources as the world around them bends to that foe’s will. CREATING LAIR ACTIONS When creating your own creatures with lair actions—or if you want to expand on the lair actions of an existing creature—you have several options. Regardless of which method you choose, it’s worth noting that the damage dealt by lair actions should be counted as part of a creature’s damage output for the purpose of calculating their CR. Thus, if you add lair actions to a creature, their CR may increase. However, because creatures with lair actions are typically high challenge, you can often not worry about this CR bump if you know the characters can handle the increased threat. RESKINNING You can quickly create lair actions by looking at the lair actions of published monsters, many of which can be easily reskinned to fit different environments. A falling stalactite can become a falling chandelier or a stack of crates toppling onto the heroes. A teleportation effect can be reproduced as a magical wind, movement through shadows, or temporarily stepping into the Ethereal Plane. Divine healing can be reskinned as a healing spring, an arcane device that knits flesh back together, or armor that repairs itself. MONSTER POWERS Many of the monster powers found in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22) can be set up as though their benefit is channeled from the environment rather than from a creature directly. A power that creates a damaging BOSSES NEED THE HELP Mike maintains that the damage created by lair actions is often necessary, and shouldn’t be counted as part of a creature’s regular damage output in all cases. Boss monsters, by virtue of being an obvious single target with limited actions, are often underpowered for their challenge ratings. As such, having lair actions for damage, control, and protection is often vital to ensuring a fun boss encounter. aura can become a zone of energy spreading around a specific point, while a power that grapples could originate from a tentacle emerging from a pool or a portal. As an example, consider the Telekinetic Grasp monster power: Telekinetic Grasp (Action). This creature chooses one creature they can see within 100 feet of them weighing less than 400 pounds. The target must succeed on a Strength saving throw (DC = 11 + 1/2 CR) or be pulled up to 80 feet directly toward this creature. Then consider how that might be turned into a lair action: Telekinetic Grasp. One creature in the lair weighing less than 400 pounds is grasped by a telekinetic force and must make a Strength saving throw (DC = 11 + 1/2 CR). On a failure, the target is pulled up to 80 feet directly toward a location chosen by the creature using this lair action. TEMPLATE LAIR ACTIONS The following lair actions can be used as templates by changing the exact nature of how the environment creates the indicated effect. The type of lair action is indicated in parentheses after the name. Elemental Damage (Damage). A blast of elemental energy targets one creature who the creature using this lair action can see within 100 feet of themself. The target must succeed on a Dexterity saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) or take 2 × CR damage of an appropriate elemental type. Falling Structure (Damage, Control). Part of a ceiling, wall, column, or some other part of the lair collapses onto one target who the creature using this lair action can see within 100 feet of them. The target must succeed on a Dexterity saving throw (DC = 10 + 1/2 CR) or take CR bludgeoning damage and be knocked prone. The target is then restrained, and can be freed with a successful DC 10 Strength check made as an action by the target or a creature who can reach them. Obscuring Cloud (Control, Protection). The creature using this lair action chooses a point they can see within 60 feet of them. A cloud fills a 30-foot-radius area centered on that point. The creature using this lair action can see normally within and through the cloud, which is a heavily obscured area for all other creatures. The cloud lasts until the creature using this lair action does so again or is reduced to 0 hit points. It can also be dispersed by a wind of at least 20 miles per hour. Restorative Energy (Protection). Restorative energy is channeled from the environment into the creature using this lair action. The creature regains 2 × CR hit points and can attempt to end one condition or magical effect affecting them. If ending an effect normally requires a saving throw, the creature immediately makes the saving throw with advantage, ending the effect on themself on a success. 37 LAZY TRICKS FOR RUNNING MONSTERS This section presents a number of tricks and tips that can help you more easily prepare and run monsters during your games. We call them “lazy tricks” not because they’re about cheating or doing less work overall, but because they’re meant to let you quickly accomplish things when your game is in progress and you don’t have a lot of extra time. Many of the concepts below are described in more detail in other sections of Forge of Foes. QUICK MONSTER STATISTICS “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4) provides great guidelines for creating a foe for your game in just a few minutes. But you can come up with an even quicker set of monster statistics using the following steps. First, choose a challenge rating for your monster, based on their perceived power in the encounter. When needed, compare your monster to existing monsters to find a suitable challenge rating. Then use the following guidelines to craft their baseline statistics: • Armor Class = 12 + 1/2 CR • Hit points = (15 × CR) + 15 • Proficient saving throws and skills = 4 + 1/2 CR • Nonproficient saving throws and abilities = −2 to +2, based on the monster’s story • Attack bonus = 4 + 1/2 CR • DC for saving throws = 12 + 1/2 CR • Total damage per round = (7 × CR) + 5 Start your monster out with one attack, then add one additional attack at CR 2, CR 7, CR 11, and CR 15. Split the total damage noted above across all attacks. With a solid set of combat statistics at hand, you can then use narrative descriptions to make your monster unique, interesting, and evocative. Damage Reflection. Whenever a creature within 5 feet of this creature hits them with a melee attack, the attacker takes damage in return of a type appropriate to the creature. The damage dealt is equal to half the damage of one of this creature’s attacks. If you give a creature this feature, give them one less attack than normal. Misty Step. As a bonus action, this creature can teleport up to 30 feet to an unoccupied space they can see. Knockdown. When this creature hits a target with a melee attack, the target must succeed on a Strength saving throw or be knocked prone. Restraining Grab. When this creature hits a target with a melee attack, the target is grappled (escape DC based on this creature’s Strength or Dexterity modifier). While grappled, the target is restrained. Damaging Burst. As an action, this creature can create a burst of energy, magic, spines, or some other effect in a 10-foot-radius sphere, either around themself or at a point within 120 feet. Each creature in that area must make a Dexterity, Constitution, or Wisdom saving throw (your choice, based on the type of burst). On a failure, a target takes damage of an appropriate type equal to half this Give any custom monster impactful features and attacks that make sense for their place in the game. When a monster feature deals damage, choose a damage type appropriate to the creature’s physiology, theme, or story. A creature channeling magical power might deal acid, cold, fire, lightning, force, poison, psychic, necrotic, radiant, or thunder damage. A creature making use of spines, spikes, or projectiles might deal bludgeoning, piercing, or slashing damage. Damaging Blast. This creature has one or more single-target ranged attacks using the attack bonus and damage calculated above, and which deal damage of an appropriate type. 38 VÍCTOR LEZA TEN USEFUL MONSTER FEATURES creature’s total damage per round. On a success, a target takes half as much damage. Cunning Action. On each of their turns, this creature can use a bonus action to take the Dash, Disengage, or Hide action. Damaging Aura. Each creature who starts their turn within 10 feet of this creature takes damage of a type appropriate to the creature. The damage dealt is equal to half the damage of one of this creature’s attacks. If you give a creature this feature, give them one less attack than normal. Energy Weapons. The creature’s weapon attacks deal extra damage of an appropriate type. You can add this damage on top of the creature’s regular damage output to give them a combat boost, or you can replace some of the creature’s normal weapon damage with this energy damage. Damage Transference. When this creature takes damage, they can transfer half or all of that damage (your choice) to a willing creature within 30 or 60 feet of them. This feature is particularly good for boss monsters, as discussed in “Building and Running Boss Monsters” (page 31). USING AVERAGES By default, 5e monster stat blocks calculate the average damage for any attack’s dice expression, as with “13 (2d8 + 4) bludgeoning damage” for an ogre’s Greatclub attack. Using average damage for a monster’s attacks is one of the best ways to speed up combat. Sometimes, though, you need to roll damage for effects that aren’t in a stat block. When you do, you can use the following table to quickly look up the average value of various dice equations. Simply find the number of dice in the leftmost column, then go across to the appropriate die type. As can be seen in the table, you can add up averages to get an average value for higher numbers of dice—for example, adding the average of 2d10 and 6d10 to get the average of 8d10. You can use this approach to find the average for rolling more than twelve dice, so that if you need an average for 24d10, you can simply look at the 12d10 average and double it. # of dice d4 d6 d8 d10 d12 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 5 7 9 11 13 3 7 10 13 16 19 4 10 14 18 22 26 5 12 17 22 27 32 6 15 21 27 33 39 7 17 24 31 38 45 8 20 28 36 44 52 9 22 31 40 49 58 10 25 35 45 55 65 11 27 38 49 60 71 12 30 42 54 66 78 (The monster powers that appear in “Building a Quick Monster” on page 4, “Monster Powers” on page 15, and “Monster Roles” on page 22 often provide damage expressions such as “4 × CR.” If you’re a GM who loves to roll dice, you can use this table to convert those fixed damage values back into a dice-rolling expression by finding an average close to the fixed value.) You can also compute averages for dice expressions with simple equations you can keep in your head. The average of two dice is the maximum value of one of those dice + 1, so that the average of 2d12 is 13. Then double that number for multiples of two, so that the average of 2d8 is 9, the average of 4d8 is 18, and so forth. Likewise, the average of a single die is half the size of the die, so add that number to a two-dice average to get odd numbers. For example, the average of 4d6 is 14, so the average of 5d6 is 17. (The average of one die is actually half the size of the die plus 0.5, which is why the average of two dice is the maximum value of the die +1.) THE LAZY ENCOUNTER BENCHMARK Build encounters based on the story, the situation, and the location. When you want to check whether a particular encounter is too challenging for the characters, you can use a simple benchmark (detailed in “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” on page 70) to see if the encounter might be inadvertently deadly. OTHER LAZY MONSTER TRICKS Once you’re in the middle of an encounter, you can make use of a number of other quick tricks to make running monsters easier, with more flexibility and greater speed. Try any of the following options at your table, and make use of any trick that helps your game: • Use fixed initiative for monsters equal to 10 + each monster’s Dexterity bonus. Even faster? Just have all monsters act on initiative count 12. • Reduce hit points on the fly to allow monsters to drop or surrender more quickly, or increase a monster’s number of attacks or damage if the characters are having too easy a time. (“Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27 talks about these kinds of adjustments.) • Have foes flee or surrender when it makes sense to move the game forward. (“Exit Strategies” on page 91 and “On Morale and Running Away” on page 125 talk more about this.) • Have constructs and undead be destroyed when the creature controlling them dies. • Run multiple waves of monsters for big battles. (“Building and Running Boss Monsters” on page 31 talks more on this topic.) • Include creatures designed to eat “save or suck” attacks such as banishment or polymorph. (“Lightning Rods” on page 44 has more information on this.) 39 RUNNING MONSTERS FOR NEW GAMEMASTERS Forge of Foes contains numerous tips and tools to help GMs run monsters. But as with any collection of advice, some of what’s here can feel relatively advanced for GMs new to the game. This section offers tips to help relatively inexperienced GMs run monsters effectively—and can serve as a refresher for advanced GMs as well. 1ST LEVEL = VULNERABLE Though it seems illogical, 1st level is the most dangerous and potentially lethal level in an adventurer’s career. With their low hit points making it easy for them to drop—and easy to be permanently dispatched if they take damage while dying—characters are significantly more likely to die at 1st level than at any other point in the game. Monsters matched up against 1st-level characters at a particular encounter difficulty are almost always more dangerous than monsters matched up against higher-level characters at the same difficulty. So when designing or running encounters for 1st-level characters, pay careful attention to how lethal those encounters might get. Run fewer monsters than characters, and ensure that the monsters are CR 1/4 or less. Even a CR 1/2 foe might prove deadly to a 1st-level character. Though you might expect CR 1 monsters to be a good match for characters of 1st level based on hit points and defenses, many such monsters can deal potentially deadly damage. A bugbear or a dire wolf, for example, can deal enough damage to easily kill a low-hit-point character with one attack. A specter can easily kill a 1st-level fighter or barbarian with a single hit. So be nice when the characters are at 1st level. You have nineteen more levels to turn up the heat. (“Monsters and the Tiers of Play” on page 74 also talks about the perils of 1st level.) MORE MONSTERS, MORE DANGER No matter whether the characters are fighting monsters of a challenge rating appropriate to their level, more monsters are almost always more dangerous than fewer monsters. Even if a creature is significantly more powerful than the characters, that creature is at a big disadvantage due to their lower number of actions as compared to the number of actions the characters can take. (This concept is called the “action economy,” and is talked about in “Understanding the Action Economy” on page 42.) When in doubt, keep the number of foes below the number of characters to make an easier fight. Whenever an encounter has more monsters than characters, the challenge goes up. 40 THE 5TH-LEVEL POWER SURGE In the same way that the characters get much better at surviving when they reach 2nd level, 5e games have other leaps in character power at 5th, 11th, and 17th level. Starting at 5th level, you’ll see the characters pinning down powerful foes with a single failed saving throw. You’ll see huge hordes of monsters taken out of the fight with spells such as hypnotic pattern and fireball. You’ll watch fighters cleave through powerful opponents with ease, both from the increases to their attack modifier and damage, and their ability to dish out four attacks in a turn using Action Surge. Even though combat changes at 5th level in the characters’ favor, that doesn’t mean you have to make everything harder. But understanding and expecting the power jump at 5th level lets you think about different ways to handle that jump. Easy battles are still a lot of fun (as talked about in “Running Easy Monsters,” page 124). And you can learn what kinds of foes are the best challenge for the characters’ new capabilities in “Lightning Rods” (page 44) and “Monsters and the Tiers of Play” (page 74). READ THE WHOLE STAT BLOCK When running a monster, it’s easy to focus on their big combat statistics. You might look only at a creature’s hit points, Armor Class, and attacks while getting ready to run an encounter. However, many monsters have useful and critical capabilities described in their other statistics, such as resistances, immunities, senses, and proficiencies. A goblin’s +6 bonus to Dexterity (Stealth) checks might be relevant to how you set up an encounter with goblin cultists, given the circumstances and situation. More complicated monsters often have important features noted as bonus actions or reactions, and it’s easy to miss these features when you’re in the heat of the game. Stat blocks also tell you the story of a monster. By looking at a creature’s ability scores and skill proficiencies, you can recognize how those numbers might feed in to that story. “Reading the Monster Stat Block,” page 102, has more details on this. While preparing your game, review any stat blocks you think you might run. Then review them again just before you run them, right at the table. By taking thirty seconds to remind yourself what a monster brings to an encounter, you’re less likely to forget a feature and miss an opportunity for a more memorable game. SANDWICH MECHANICS WITH FLAVOR It’s easy to lose track of the fiction going on in the world of your game when you’re focused on the mechanics of combat. So consider sandwiching mechanical descriptions with the flavor of what’s happening around the characters. For example, rather than simply reporting the damage a character takes on a successful hit, you can say something like: “The cultist hisses at you and slashes with her jagged curved blade. It hits you for 6 slashing damage as the blade cuts through your leather armor and into your flesh.” Likewise, the mechanics of rolling damage and saving throws for a complicated spell can be made more interesting as part of a descriptive narrative. “Durrim, you hurl your fireball into the room full of unsuspecting ghouls, one of them turning your way just as the spell explodes in a roar of flame. Roll 8d6 damage. Two of the eight ghouls make their saving throws, but six of the eight burst into flames, leaving only two. They’re smoldering and burnt, but still fighting!” Even when crunching numbers, you can move the story along. Use those silly vocal sound effects you used to love in middle school, and don’t lose sight of the fiction happening during the game. MONSTERS DON’T HAVE TO BEHAVE OPTIMALLY A veteran might have three attacks at their disposal, but that doesn’t mean they have to take them. Sometimes the characters’ foes make poor choices and bad decisions. They might let ego get in the way of their better judgment. They make tactical errors. An enemy spellcaster might hold back their most powerful spells, thinking that the characters are easy targets. A troll commander might toy with a hero, attacking only with a single claw. A gnoll outlaw in a position to finish off a dying cleric might turn their attention to the pesky fighter interrupting their finishing move. Whenever it increases the fun of the game for the players, let the monsters make mistakes. REDUCE HIT POINTS TO END BATTLES EARLY Proper pacing is one of the most important parts of keeping a game fun for both you and the players. Sometimes battles go on too long, threatening to end a fun encounter as a final slog. If this happens, just reduce the hit points of monsters to let the next hit take them out of the fight, letting you and the players move on to the next part of the story. Many monster statistics can be fine-tuned before or during the game, helping you focus on fun and helping the monsters play the part you want them to in the narrative. “Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27 talks about the kinds of adjustments you can make on the fly to make a foe easier or harder in combat. These dials include a creature’s hit points, their number of attacks, and the damage they deal, as well as the overall number of foes in a battle. You can tweak all these dials to suit your story and its pacing, but reducing a monster’s hit points can be the most powerful dial for keeping your game fast and fun. UNDERSTANDING CHALLENGE RATINGS The concept of challenge rating as it defines a monster’s power level can be hard to grasp. “What Are Challenge Ratings?” on page 99 breaks down this measure of monster difficulty in detail, but you can keep a few simple rules in mind: • A challenge rating compares one monster to another. There isn’t a perfect comparison between character levels and monster challenge ratings. • A monster is a hard challenge for a single character if their challenge rating is roughly 1/4 of a character’s level, or 1/2 of a character’s level if the character is 5th level or higher. • A single creature might be particularly challenging to a group of characters if the creature’s challenge rating is greater than 1.5 × the average character level. • A battle might be more challenging then you want it to be if the sum total of monster challenge ratings is greater than 1/4 of the sum total of character levels, for characters of 1st to 4th level; or greater than 1/2 of total character levels if the characters are 5th level or higher. (The above comparisons are taken from “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” on page 70, which explains them in more detail.) Challenge ratings are a rough gauge of monster power—not a perfect measurement. Challenge rating comparisons alone don’t determine the difficulty of a battle, as many other factors can come into play: • The specific situation • The combat environment • The experience of the players • How well the characters’ attacks and features work together • Whether most of the characters or most of the monsters come first in the initiative order • What kinds of magic items the characters possess As the GM, you’ll develop a much better sense for the capabilities of the characters and the potential difficulty of a battle as you gain more experience running games for your group. UNDERSTANDING A MONSTER’S ROLE Some monsters like to get up in front of the characters and hit them with clubs. Some work better while lurking in the shadows. Others want to be up on a ledge raining magic down upon their foes from a distance. When reading a stat block, consider what role and position a monster might prefer in combat. An evil mage can have a ton of powerful spells, but they might never get a chance to use them if they’re up front getting hit. A squad of veterans can be mighty opponents, but not if they’re stuck on the other side of a chasm. So always put the veterans up front and stick the mage in the back. (“Monster Roles” on page 22 talks more on this topic.) 41 UNDERSTANDING THE ACTION ECONOMY Often, GMs look at the powers, actions, and statistics of characters and monsters and take those statistics at face value. A fireball spell creates a huge blast of flame. A paladin smites foes by channeling divine energy into their attack. A wizard’s power is measured by the number of spells they wield and the spell slots with which they cast them. But there’s an equally important element to the game that’s not as obvious—the action economy. The game’s action economy is the comparison between the number of actions the characters can take and the number of actions their foes can take. If these numbers of actions are imbalanced, one side has a distinct advantage over the other, regardless of how good their actions and attacks are, because one side can simply do more things. Understanding the action economy is critical when considering the challenge of an encounter. As you consider the characters and the foes they face, consider how the action economy is balanced—or imbalanced—between them. MORE MONSTERS! LEGENDARY ACTIONS 42 When a single foe faces a whole group of characters, that foe is at a distinct disadvantage with the action economy. In a typical party, four to six characters each have actions they can take in a round, while the poor monster might have only one. The iconic CR 15 purple worm can probably swallow a house. But with only two attacks, it’s possible that the worm might do nothing at all in a round if they miss both times. The purple worm is a powerhouse monster by virtue of how nasty their attacks are, but distinctly falls short in the action economy. They just don’t have a lot of actions they can take compared to the characters. By contrast, other creatures such as the adult red dragon can do lots of things. The designers of 5e D&D knew that particular monsters often face groups of characters alone, putting them at an action economy disadvantage. For this reason, those creatures are given legendary actions— actions they take between other characters’ turns to make up for the lack of actions on their own turn. An adult red dragon can attack up to six times across a round—three on their turn and three times with legendary actions. Not bad. When you want to run a single nonlegendary creature against a group of characters, consider increasing that creature’s actions to account for the imbalance in the action economy. “Building and Running Legendary Monsters,” page 28, has more information on this topic. MODIFYING THE ACTION ECONOMY DURING A BATTLE Even without building out a full-blown legendary monster, you can change up a potential imbalance of actions by simply giving creatures more attacks as part of their Multiattack action (or giving them Multiattack if they don’t already have it). This is a significant threat boost to a creature, sometimes doubling the amount of damage they can deal in a turn, so take care. Giving a purple worm an additional Tail Stinger attack represents MATT MORROW Perhaps the easiest way to balance the action economy is to include enough foes to roughly balance the actions of the characters. Beyond having more actions they can collectively take, a larger group of monsters means more targets. It means the characters’ damage is often spread across multiple foes instead of focusing on one big threat. “Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27 talks about how a GM can adjust encounters before or during play. The “Number of Monsters” dial is a powerful tool for tuning a battle’s difficulty. It’s perhaps the strongest dial you can turn, as it can affect both the challenge of a fight and the time it takes to complete that fight. a significant jump in the danger that creature brings to an encounter. For something a bit less drastic, consider letting the monster attack a second time if they miss with their first attack. There’s little difference between this approach and granting a creature advantage on their attack rolls, except in how you describe the effect during the game. You might use this approach on a powerful creature who dishes out tremendous damage, allowing them to hit more reliably, but capping their damage lower than if they were hitting twice. For example, a frost giant who attacks again after a miss with their first attack has a greater chance of dealing their average 25 damage on a turn, but is still less likely to deal their full 50 damage per turn. THE ACTION ECONOMY AND SPELLCASTING Monster and NPC stat blocks sometimes feature long lists of castable spells presenting a wide range of combat options. But a spellcasting creature can cast only one spell per turn. Sometimes this is fine, as when a group of cult fanatics throw around inflict wounds spells one at a time just as the characters might. But noteworthy spellcasters, including boss monsters, can improve their standing in the action economy by casting spells as part of an existing Multiattack action, replacing one of their normal attacks with their spellcasting action. For creatures who don’t have the Multiattack action, you can give it to them, letting them cast a spell as well as attack on their turn. Giving NPC spellcasters the ability to cast more than one spell on a turn increases the threat they can bring to a battle, so keep that in mind. But for other monsters, casting spells alongside other attacks can help them keep up with the characters’ actions, even as it lets them reinforce their place as a dual melee-and-magic threat in the fiction of the game. (“Building Spellcasting Monsters,” page 34, and “Running Spellcasting Monsters,” page 58, both offer additional points of view on mixing monsters and magic.) SPELLS AND FEATURES THAT BALANCE THE ACTION ECONOMY Some spells and features scale particularly well with efforts to improve the action economy for monsters and other foes, becoming more powerful the more characters a foe faces. Spells such as fire shield directly affect enemies who hit the caster—every time. As such, it’s one of the few features in the game that becomes more effective as the caster becomes more outclassed in combat. A paladin who smites an adult black dragon protected by fire shield takes an average of 9 damage for each hit. A monk who strikes the dragon four times with a flurry of blows takes 27 damage! The balor’s Fire Aura trait scales in two different ways— damaging any characters who happen to be next to the balor at the start of the balor’s turn, as well as characters who attack and hit the balor while next to them. The balor might get only two attacks on their turn, but their aura deals significant damage without expending any actions, and increases in threat as more characters move in close to attack. Damaging defensive effects and damaging auras, whether spells or innate abilities, are gifts that keep on giving when it comes to balancing the action economy. Whenever you’re creating or running a boss monster or some other creature likely to face the characters alone, these kinds of passive-damage features can help. The monster powers in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22) offer a number of such options, any of which can help a foe scale up their threat without requiring extra actions. You can also assign monster powers to terrain features, such as an altar that has the Damaging Aura power, or an arcane orb that targets a hero each round with the Telekinetic Grasp power. Setting the terrain features to activate on a specific initiative count, such as 20 or 15, gives you extra actions each round that can shift the action economy in your favor. You can then add simple ways for the characters to deactivate such features by using their own actions. The following table highlights a number of spells that are particularly good at balancing the action economy in favor of a creature making use of them. To further improve their value, consider letting foes cast some of these spells before combat begins, in addition to their personal protection spells. ACTION-BALANCING SPELLS Spell Level Spell Spell Level Spell 1 Fog cloud 3 Haste 1 Hellish rebuke 3 Slow 1 Shield 3 Spirit guardians 2 Blur 4 Fire shield 2 Darkness 4 Greater invisibility 2 Spiritual weapon 5 Antilife shell 3 Blink 5 Cloudkill 3 Fear 7 Divine word 3 Fly 9 Foresight PRECASTING PROTECTION SPELLS Many spellcasters have a number of spells that enhance or protect them, but wasting a number of rounds to cast those spells during combat greatly reduces the caster’s effectiveness. Instead, consider having foes precast any such spells that last a long time and don’t require concentration, such as mage armor, fire shield, or true seeing. You can also select one long-duration concentration spell that a foe can cast before a fight if they suspect adventurers might be present, such as globe of invulnerability, fly, or invisibility. Precasting spells frees up a foe’s actions during the actual battle, allowing you to spend those actions on spells that target the heroes. 43 LIGHTNING RODS When characters rise above 4th level, their ability to deal with powerful foes makes a huge jump. But challenging characters of 5th level and higher isn’t just about making things hard. It’s easy for GMs to fall into the trap of thwarting the coolest things the heroes can do, by giving monsters immunities to certain conditions, increasing their hit points to offset the high damage a character can deal, or running monsters with tactics clearly built to bypass the characters’ best attacks. But thwarting the characters’ best features can be frustrating to the players, for obvious reasons. So instead of shutting down the characters, build your encounters around monsters specifically designed to show off—by eating up—the characters’ cool new capabilities as they rise in level. You can think of these monsters as “lightning rods”—intended victims ready to take the full effect of a character’s most powerful attacks and features. WATCH WHAT THE CHARACTERS BRING When running encounters challenging enough for the characters to use their top-tier features and attacks, pay attention to what they do. Does the wizard blast enemies with high-damage spells like fireball? Does the cleric make liberal use of Turn Undead when faced with those monsters? Do spells like polymorph or banishment come into play to get rid of bosses and elite threats? Note which features the players enjoy having their characters use, and think about how to build for those features in your next big battle. If you aren’t sure what features the characters have, ask the players. Each time the characters level, start the session by having the players talk about what new attacks, spells, and special abilities they’ve picked up. Then build encounters to show off those features, not avoid them. For example, at higher levels, a monk gains the ability to stun creatures with a single strike, effectively taking a monster out of the fight for a round or more. So when you know a player’s monk has this feature, add monsters into big battles that you specifically want the monk to stun. A smack-talking spellcaster with a low Constitution saving throw, and who only a monk can reach with their enhanced movement, is just begging to have a hero leap up and punch them in the face. RUN HORDES FOR AREA EFFECTS 44 At 5th level and above, characters get access to spells and class features with large areas of effect, including hypnotic pattern, fireball, and Destroy Undead. When you know the characters have such features at their disposal, add hordes of low-CR creatures who can charge at them, all grouped up and ready to be blasted away. Ignore the fact that it might be more tactically appropriate for such creatures to spread out, instead thinking of yourself as the director of an action movie. What’s the coolest outcome for the scene—a group of careful zombies staying 20 feet away from one another, or a huge mob of undead in perfect position to be turned to ash or blown to pieces with a well-placed fireball? (“Running Minions and Hordes,” page 54, talks more about running large numbers of monsters in combat.) EXPENDABLE LIEUTENANTS Many legendary monsters can use Legendary Resistance to avoid being taken out with a single casting of banishment or polymorph, but their lieutenants have no such advantage. When the characters have access to such spells, add powerful monsters into your encounters specifically designed to be banished, polymorphed, or otherwise controlled or incapacitated. Monsters with the bruiser or defender role are often perfect targets for such spells (see “Monster Roles” on page 22), especially those with terrible Wisdom and Charisma saving throws. Keep in mind, though, that if you add one or two hardhitting foes to an encounter who don’t get controlled, things can go south for the characters quickly. FRAGILE DAMAGE-DEALERS For stunning-strike monks, hard-hitting paladins, sharpshooter rangers, or great-weapon fighters, fragile foes who deal a ton of damage make fantastic targets. These are creatures with a low Armor Class, low hit points, and a low Constitution save, but who are deadly until taken out. (Creatures with the artillery or skirmisher role are great choices; see “Monster Roles” on page 22.) It’s always rewarding for a character to reach such a foe and cut them down with a single powerful attack. PLAY TO THE CHARACTERS’ STRENGTHS Players and their characters love to outsmart their foes. You can help with this by placing artillery in locations that the foes assume will be hard to reach, but which you know present just a minor challenge to characters who can climb, fly, or short-range teleport. Likewise, add hidden ambushers when you know that some of the characters will be able to easily perceive them. These sorts of setups let the characters show off, and reward the players for choosing those specific tactical capabilities. TELEGRAPHING LIGHTNING RODS Less tactically minded players might need help, or even direct advice, to recognize the danger of not dealing with lightning rods. If you intend for a fire giant bodyguard of the hobgoblin king to be banished and the characters don’t pick up on that, they might be in trouble when the giant starts pounding them into the ground like tent pegs. If the characters are focused on the boss while getting pelted by the fiery rays of flameskulls just begging to be stunned, blasted, or turned, be prepared to project or reveal outright to the players the dangers their characters face, and how they might deal with them. MODIFYING MONSTERS BEFORE AND DURING PLAY As a GM, you have many ways to customize monsters to make them the best fit for a particular encounter. You might simply give them a few more hit points. Or you might revise them completely, changing their stats, adding new features, or modifying their existing features. Some of these modifications are quick and easy. You can often do them in your head while running the game. Other modifications require time and thought best suited for game prep. This section discusses which monster modifications work well before your game begins, and which modifications you might make during play. WHY MODIFY MONSTERS? Why modify a creature in the first place? Why not run with the default monster stat blocks? Most of the time, monsters run fine as written. With dozens of excellent books of foes to use, you can almost always find one befitting the scene and situation of an encounter. Even when reskinning an existing stat block into something new (see “Reskinning Monsters,” page 50), you likely don’t need to make many changes to the mechanics, letting the monster work as intended. Sometimes, though, the story of a creature in the world of the game and the mechanics you find in a published stat block don’t match. Sometimes, you know a monster just won’t hold up to the characters in your group. Sometimes an encounter promises to be less fun than you want if a monster doesn’t get a little something extra. CHANGING THE MECHANICS TO FIT THE STORY You might want to modify the statistics of a monster so that they better fit their place in the story and the world. Maybe the basilisk the characters face is no normal basilisk but a dire basilisk, twice the size of their kin. They have more hit points. Their attack bonuses and DCs are higher. Maybe they can make more attacks per round. In such a case, the standard basilisk stat block isn’t enough. So you might decide to use the young black dragon stat block instead, giving them the Petrifying Gaze trait of the normal basilisk, and losing the black dragon’s flying speed. This basilisk is new and different, but this sort of reskin works well because the modifications fit the story. When any of the following issues present themselves, you can think about changing the mechanics of a monster to fit the story: • A creature you want to use needs to be significantly bigger than the baseline stat block. • The monster of your story has a trait a published monster doesn’t have. • A creature has unique skills, such as a dragon spellcaster or an undead knight. • A monster needs to be more of a mini-boss version of their type—one who stands out among their peers. INCREASING THE CHALLENGE OF A MONSTER Increasing the challenge a monster provides in combat is another common reason to modify a stat block. Instead of coming at it from the story first, you might know that a party of 9th-level characters won’t be challenged facing CR 2 creatures. But the creatures still make sense for the situation, so you boost them mechanically, either reskinning a higher-CR stat block or increasing the creatures’ baseline stats directly. It still helps to have an in-world reason for such changes, though. If a group of soldiers is much stronger than normal CR 1/8 guards, what makes them so formidable? If the evil queen’s bodyguard hits like a fire giant, what makes him so strong and powerful? Even if a monster’s story is a secondary consideration to their increase in challenge, it’s worth thinking about the narrative behind that increase. MAKING THE GAME MORE FUN Beyond story and mechanics, we modify monsters for the fun of the game. Reworking the baseline statistics of a foe can make combat more exciting, showcase the characters, enrich the story—and make it easier to get foes off stage when their time is done. WHEN NOT TO MODIFY MONSTERS Never modify monsters to punish the players. Don’t rebuild creatures specifically to circumvent the characters’ most powerful capabilities. And don’t modify monsters just to beat the characters into the ground. Just because one of the characters picked up the banishment spell doesn’t mean all monsters should suddenly become immune to banishment. (“Lightning Rods” on page 44 has more guidance on these topics.) Before modifying any creature, ask yourself why you’re modifying them. Is it to fit the story or make the game more fun? Are your modifications helping you keep up the right pace and beats to make your game exciting? Make sure your monster modifications enrich the game and don’t diminish it. MODIFYING MONSTERS BEFORE THE GAME When preparing adventures and selecting monsters, ask if the standard stat blocks for the creatures you select work well enough as is. Most of the time, they should. You can always make a given creature unique in the flavor of your 45 descriptions—for example, giving them a proper name and a few scars to show their history. But a chimera is a chimera, and if the standard chimera stat block works fine on its own, there’s no need to change it. If you don’t have the right monsters on hand, look at your toolbox of options and determine how to make the monster you need. Should you reskin an existing stat block? Should you build something from scratch? The crunchier the details you want to add to a creature, the more likely you’ll want to do this work ahead of time instead of at the table. (“Building a Quick Monster,” page 4, and “Reskinning Monsters,” page 50, provide guidance for both these approaches.) Often, you can make significant modifications or entirely new monsters on an index card or in whatever digital tool of choice you use to run your game. Don’t worry about the formality of these changes or matching the style of mechanical wording perfectly. You know what you mean. Likewise, don’t bother recalculating the challenge rating of a creature after you’ve modified them just to assess how they fit an encounter. Your own understanding of the characters, their capabilities, the environment of the encounter, and other potential factors paint a much more accurate picture of the potential challenge than any encounter-building tool or equation. If you find yourself needing to figure out a modified creature’s new challenge rating (for example, if you’re giving out experience points immediately after combat), you can do so by comparing the creature’s capabilities to the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table on page 6, or compare the creature to other monsters in your favorite monster book. Don’t sweat it too much, though. These modified monsters are just for you and your group. Quick guesses and scratchy notes are just fine. Modifying monsters during play is also an excellent way to change the pacing and challenge of an encounter during the game. Some GMs oppose this idea, and it’s fine if that’s how you feel. Changing a creature’s statistics during an encounter can feel a bit like cheating. It’s moving the goal lines while the game plays out—but sometimes you don’t realize that you accidentally set the goal lines too far out to begin with. Decide for yourself if such changes are acceptable, and if so, when. “Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27 offers lots of guidance for ways to modify monsters during play. LOWERING HIT POINTS TO END BATTLES EARLY Of all the topics discussed in “Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27, few are as important and valuable as lowering hit points to speed up a dreary battle. Doing so is an incredibly useful tool for keeping the pace of your game moving forward. Even if you feel as though changing damage, increasing hit points, and adjusting a creature’s number of attacks are a form of “cheating,” consider reducing a monster’s hit points to keep your game moving quickly and staying fun. Sometimes, a creature needs modifications that are minor enough to make on the fly. To determine what changes work well when made during a game session, keep the following in mind. First, if you’re playing fast and loose, you can save time by modifying monsters as the need arises in a battle. “Reskinning Monsters” on page 50 describes how to omit details when reskinning a creature unless and until you need them. If the story of your custom monster means that they have immunity to poison, just add that feature during the game when you need it, rather than worrying about it ahead of time. A skeletal frost giant is undead, so you know they’re subject to Turn Undead even if you didn’t bother to jot that down before they showed up in combat. 46 FABIAN PARENTE MODIFYING MONSTERS DURING THE GAME RUNNING MONSTERS IN THE THEATER OF THE MIND While many GMs run combat using a gridded battle map, online virtual tabletop, or other physical representation of positioning in combat, some prefer to use a purely narrative approach often called “theater of the mind.” Even if you run games this way only occasionally—or if you’re wanting to try theater of the mind—it’s good to recognize how this style of play works, and to discuss it with your players. In theater-of-the-mind combat, the GM describes the physical situation, the players describe what they want to do, and the GM arbitrates the results. On each player’s turn, the GM clarifies the current situation, and might offer some options for what a character can do. However, many monster features are described in ways that make it difficult to run purely descriptive combat. If a creature has a spell blasting all targets in a 20-foot radius, how does a GM decide which targets are in the blast and which are not? CHOOSING NUMBERS OF TARGETS One way to remove some of the uncertainty of descriptive combat is to make all creatures’ attacks less dependent on physical positioning. As an example, a monster who uses the lightning bolt spell needs to know how many characters are currently in a line. But instead of thinking that way, consider instead how many creatures an attack or feature feels likely to hit, and then target that number of creatures directly. Thus, instead of hitting each creature in a line with a lightning bolt spell, a foe’s Lightning Arc attack might target three creatures within 60 feet, reducing its range to fit the theme of the attack. When looking at monster attacks or offensive spells, you can gauge how many creatures such an effect might target based on its size, as shown on the following table. NUMBER OF TARGETS BY AREA OF EFFECT Area Shape and Size Number of Targets 5-foot-radius sphere 1 10-foot-radius sphere 3 20-foot-radius sphere 4 30-foot-radius sphere 12 30-foot-long, 5-foot-wide line 2 60-foot-long, 5-foot-wide line 3 90-foot-long, 10-foot-wide line 4 120-foot-long, 10-foot-wide line 6 15-foot cone 2 20-foot cone 3 30-foot cone 4 60-foot cone 6 Depending on the situation, you might decide that more or fewer creatures are caught in an area. For example, you can turn a monster’s use of a magical attack mimicking the fireball spell into a fiery blast targeting four creatures. If you want to add a fun negotiation when a character casts fireball, ask the players if they’re willing to add two more enemy targets into the blast—by being willing to include one of the characters in the area as well! ROLL RANDOMLY FOR THE UNAFFECTED In some situations, the flavor of a monster’s attack doesn’t lend itself to the pinpoint accuracy of choosing specific targets. An adult blue dragon’s lightning breath might fork out like chain lightning, hitting several specific targets instead of blasting out in a line, but a red dragon’s fire breath is almost certainly a big cone of flame. When arbitrating such large areas in the theater of the mind, consider letting the dice decide who’s in and who’s out of the blast. Assuming four of six characters are hit by a young red dragon’s fire breath (a 30-foot cone), assign each character a number from 1 through 6 (using either the initiative order or the order of the players around the table to make it easy). Then roll a d6 twice, rerolling duplicates, and the two characters whose numbers match the die rolls are considered to be outside the blast. Describe how this process works before the battle begins, and make these rolls in the open so players recognize that they’re not being picked on. If any players have good in-world reasons for their characters to not become targets of a large area of effect (“I was hiding behind the wall of force spell I cast last round!”), take that into consideration. Always lean in favor of the characters when you can, as doing so can help to build the players’ trust of your approach to this narrative combat style. FOES BLASTING FOES Characters are often careful to not include their allies in the areas of their bigger spells. Monsters don’t need to be. It can be great fun for players to watch foes blow up some of their own allies with big damage. But remember that powerful monsters often have allies or servants with resistance or immunity to such damage. For example, an adult red dragon might have fire elemental or fire giant allies who take no damage from the dragon’s fire breath. Even if their allies don’t have immunity or resistance to their area-effect attacks, many foes might choose to blast those allies if doing so gives them the upper hand in the battle. Monsters can be jerks that way. 47 ROLEPLAYING MONSTERS In a campaign that leans heavily into roleplaying, few things are as much fun as a GM getting to dig into the personality and idiosyncrasies of a monster while bringing them to life at the table. Trying to negotiate safe passage through a ruin claimed by an ogre or troll. Bargaining with a chuul in possession of important magical lore. Attempting to convince a bored green dragon that the characters have more worth to them as allies than as a light snack. These kinds of monstrous interactions can make for great roleplaying scenes. However, when it comes to monster design, the game focuses to a large degree on the rules of combat first and foremost—to the extent that monster stat blocks are built mostly around traits and actions related to combat, while largely relegating the other pillars of play to ability check modifiers and flavor text. As such, when running monsters, it becomes easy to all but ignore roleplaying in combat in favor of focusing on the minutiae of attack mechanics. But actively engaging in roleplaying during a fight scene can be a great way to create fights that go beyond the usual exchanges of attacks and damage, shaping a more memorable encounter. MONSTROUS MOTIVATIONS The first step in roleplaying a monster in combat is understanding the broad scope of what that monster wants in general, and the narrower scope of what they hope to attain in this particular fight. The narrative that accompanies the stat blocks of many monsters can provide good hooks touching on the creature’s overall goals, but the specifics of the adventure and the encounter as you’ve set them up are likely the more important baseline. If you’re the kind of GM who jots down notes on which attacks and effects you want a monster to make use of during a fight, add notes on the monster’s motivations as well. If you’re not a note taker, you can instead think about the monster as if they were a character in a work of fiction you were writing, asking: What does the monster want from the fight? What do they need? What obstacles and conflicts do they perceive as getting in the way of what they want and need? A creature’s role in an adventure shapes their wants and needs in a big way. Are they a guard obligated to take on the threat the characters represent? Are they simply in the wrong place at the wrong time when the party stumbles into their lair? Do they have something to prove, giving them a perfect excuse to step into combat when well-armed adventurers wander into their territory? Are they ravenously hungry and possessed of no moral compunction against having humanoids on the menu? Do they have young or other family members to defend? And should that provoke them to attack, or inspire them to leave the fight before being badly injured? 48 Once you have a monster’s motivations noted, you can then look to two areas of information on the stat block. And just as you’ll use the rest of the stat block to guide the monster’s offensive and defensive behavior in the fight (as talked about in “Reading the Monster Stat Block” on page 102), you’ll use the monster’s creature type and mental ability scores to guide the way you roleplay those motivations while the fight unfolds. CREATURE TYPE The broad classification of creatures in the game into different types reflects biology and morphology, origin, access to magic, and other key details that are shared between different creatures. And just as creature type makes a useful shorthand for talking about different monsters’ abilities, traits, resistances, and other combat details, it can be used to collectively examine the behavior of creatures to suggest specific roleplaying tropes. Though specific creatures might have more detailed suggestions for roleplaying in the write-ups that accompany their stat blocks, you can use the following quick guidelines as inspiration for roleplaying hooks as needed: Aberration: Chaotic, ravenous, craves destruction for its own sake Beast: Territorial, cautious about combat, fights only if threatened, defends young Celestial: Accustomed to power, superiority complex, immediately forgiving or unforgiving with little middle ground Construct: Programmed, focused, unrelenting, unforgiving Dragon: Accustomed to power, haughty, superiority complex, expects adulation or fear from lesser creatures Elemental: Chaotic, capricious, treats destruction as the normal state of things Fey: Capricious, joyful or maniacal, flighty, distractible Fiend: Destructive, manipulative, fights for any reason, fearless Giant: Accustomed to power, dismissive of lesser creatures, jealous of equally powerful creatures Humanoid: Self-serving or altruistic, fight if threatened, fight to save face Monstrosity: Solitary, accustomed to not fitting in, like to show off special abilities Ooze: Mindless, driven to feed, fight in response to any provocation Plant: Mindless, fight in response to any threat Undead: Vicious, relentless, fight for the sake of fighting, driven to destroy life THINKING LIKE YOUR MONSTERS A creature’s overall intellect as defined by their mental abilities—Intelligence, Wisdom, and Charisma—makes a ROLEPLAYING MONSTERS AS PREP “Put yourself in the place of your villain,” is one of the best pieces of advice for making a villain truly come to life. Stepping into the metaphorical shoes of a boss foe and thinking about the world as they think about it can give you a much more realistic view of that foe, what they’re doing, what they want, and the steps they’re taking to get there. Such mental exercises are their own form of roleplaying—a kind of independent game you can play just in your head and as part of your prep. Putting yourself into your villain’s thoughts and mindset can guide you as you design your world and the adventures the characters are set to undertake within it. Perceiving the world as a boss monster does can tell you how they feel about the characters, what minions they might send out to do their bidding, what secrets the characters might learn about the boss, what locations they’re focusing on, what treasures they amass, what other allies the villains connect with, and so much more. great go-to roleplaying hook. A creature’s scores in those three abilities shape the way in which that creature thinks about the world, their instinctual understanding of the world, and their sense of place and importance within the world. Monsters with high Intelligence or Charisma might love to focus on their own mental and emotional superiority, making them hard to negotiate with, just as monsters with high Wisdom are traditionally hard to dupe or trick. By contrast, monsters with low mental ability scores have more trouble engaging with the world, whether a low Intelligence that makes them easily confused or reluctant to embrace complex concepts, a low Wisdom that makes them naturally incautious, or a low Charisma making them easily manipulatable and standoffish. Creatures with high mental ability scores often have a strong sense of self, convincing them that everything they do is the right course. This can make intellectually superior creatures inclined to get into fights just for the sake of doing so—somewhat ironically, given that they’re in the best position to understand what’ll happen to them if the fight goes bad. This can also make such creatures disinclined to surrender or back down in combat, unless first offered some sort of overture or face-saving “out” by their opponents. By contrast, less intellectual monsters are focused mostly on the basic goals of food, shelter, and being left alone. They often won’t enter a fight unless directly threatened, and are quick to abandon the fight if it goes against them, but might be difficult to negotiate with if their lack of intellect makes it difficult to grasp complex terms of detente or surrender. THE FINE ART OF SUBOPTIMAL CHOICES Many of the most interesting roleplaying choices a monster can make in combat—fighting for no reason, attacking a clearly superior foe to prove a point, fleeing a fight if injured regardless of the state of their foes—are at odds with the assumed overarching goal of winning the fight. And that’s as it should be. Much combat time in the game revolves around the characters being given opportunities to assess, then counter the strengths of their foes, and roleplaying those foes provides great opportunities to reveal strengths and weaknesses. Creating a sense that monsters and NPCs have a stake in every fight beyond simply stepping up as bags of hit points—playing them as wary, or afraid, or desperate, or cocky in ways that benefit the characters—can help make those fights feel as real to the players as they do to the heroes. It can also help you use roleplaying to shorten fights where the characters are so far ahead that finishing a battle might feel tedious, or to find a different outcome for a fight that the characters will almost certainly lose if they stick it out to the bitter end. (“Exit Strategies” on page 91 and “On Morale and Running Away” on page 125 both dig into this topic.) The familiar hook of “These creatures fight to the death,” is one straightforward and usually suboptimal roleplaying choice. But there are many other excellent and entertaining choices toward the bottom end of the spectrum of optimal combat tactics, and digging deeper into the intellectual boundaries of your monsters’ roleplaying can help you find them. HOOKS VS. STEREOTYPES When playing to a monster’s intellectual weaknesses in combat, be careful that your roleplaying doesn’t cross over into hurtful and offensive tropes or stereotyping. With the exception of creatures who can be thought of as “programmed” in some way (many constructs and undead; most oozes; some aberrations), creatures with a low Intelligence ability score might think differently than high-Intelligence creatures—but they’re still thinking, conscious creatures nonetheless. As such, when roleplaying creatures with a low Intelligence ability score, you want to establish those creatures as having a particular type of intellect, rather than playing them as mentally inferior, for laughs or otherwise. Most people who’ve lived around animals can imagine the conversations they might have with a dog or cat who somehow learned to talk, even with both having Intelligence 3 by the rules of the game. A talking dog might regale you with tales of how the world smells that you have no ability to understand. A talking cat might alternate between doting on you and suddenly forgetting you exist. So keep those kinds of ideas in mind when roleplaying creatures with a low Intelligence score, treating them as simply having a different intellectual focus and way of viewing the world, and avoiding ableist tropes such as pidgin speech, sluggish reasoning, and slurred words. 49 RESKINNING MONSTERS Of all the tools Gamemasters have at their disposal, few are as powerful as reskinning monster stat blocks. Reskinning a monster’s stat block lets us take the time, energy, and money invested in professionally designed monster statistics and turn them into just about any monster imaginable, quickly and easily. This brings incredible value to every book of monsters a GM owns. To reskin a monster, select an existing stat block and describe it as a completely different monster in the story and lore of the game. For example, the stat block of an ogre might be described as a powerful humanoid warrior or the thick-necked bodyguard of a local guildmaster. At its simplest, reskinning takes little more effort than finding a stat block and describing it as something else. There are layers to reskinning, however, some of which go deeper than a simple surface-level description change. This section explores those layers and the benefits that each provides. CHOOSING RESKINNABLE STAT BLOCKS As powerful as reskinning is, the process always starts with a GM finding the right stat block to reskin. An ogre stat block might be perfect for any tough and powerful humanoid, but it won’t work as well for a tentacled horror bursting out of the darkness. However, a giant octopus stat block does the trick for that horror nicely. Simpler stat blocks—those of humanoids, NPCs, animals, and giants—often work well when reskinning secondary monsters or groups of monsters. For example, the fire giant stat block easily becomes a powerful tombguardian knight. When looking to build a custom boss monster, though, think about reskinning the stat blocks of more powerful and complicated creatures—including legendary creatures. An adult red dragon stat block is a great stand-in for a powerful fire-based sorcerer boss who slashes with fiery blades (reskinned Claws and Bite) and huge blasts of pyro-energy (the dragon’s Fire Breath). Reading the Monster Manual or your other favorite monster books offers tremendous dividends for your games. Not only does it help you identify which stat blocks will work best for reskinning, but it also fills your imagination with the lore of numerous monsters, giving you a sense of how they might fit into or help you build your adventures. COMMON RESKINNABLE MONSTERS The table on this page presents a list of common reskinnable monsters for standard nonboss creatures at several challenge ratings. The stat blocks of these creatures focus on simple mechanics, with the intention that you’ll reskin their descriptions with the flavor of the monster 50 you create. (“General-Use Combat Stat Blocks” on page 13 contains a number of monster stat blocks built specifically for reskinning as well.) To use the table, look down the CR column to find the baseline challenge rating of the monster you need. The Example Monster column for that challenge rating lists a few easily reskinned monster stat blocks. The Reskinned Role column then shows you what monster role this stat block can most easily be reskinned into, broken out by tier of play and the monster’s role in combat (see below). The tiers of play break down into the following tiers and levels: 1st Level: Though standard 5e includes 1st level in tier 1, 1st-level characters are delicate enough that they really belong in their own tier of play. Tier 1: 2nd through 4th level Tier 2: 5th through 10th level Tier 3: 11th through 16th level Tier 4: 17th through 20th level The monster roles that these stat blocks can easily reskin into are defined as follows: Artillery: Ranged combatants who often attack with spells, and who typically have lower hit points, Armor Class, or both. Bruisers: Monsters with high hit points and relatively low Armor Class, and who hit hard. Controllers: Creatures who use conditions and other hindrances to impede opponents. Defenders: Creatures with high Armor Class and other defenses, and who deal moderate damage. Skirmishers: Low-defense creatures who often deal high damage, and who have superior mobility. (“Monster Roles” on page 22 has more information on breaking down monsters by role.) CR Example Monster Reskinned Role 1/8 Bandit 1st-level skirmishers 1/4 Goblin, skeleton Tier 1 skirmishers 1/2 Black bear, orc, thug Tier 1 bruisers 1 Animated armor, brown bear, spy Tier 1 defenders, bruisers, and skirmishers 2 Bandit captain, cult fanatic, ogre Tier 1 defenders, artillery, and bruisers 3 Knight, minotaur, shambling mound, veteran Tier 2 defenders 5 Gladiator; air, earth, fire, or water elemental; shambling mound Tier 2 bruisers 6 Mage Tier 2 artillery 7 Giant ape, stone giant Tier 3 bruisers 8 Frost giant Tier 3 bruisers 9 Fire giant Tier 3 defenders 10 Stone golem Tier 3 controllers 11 Horned devil Tier 3 skirmishers 12 Archmage Tier 3 artillery 13 Storm giant Tier 4 skirmishers 16 Iron golem Tier 4 defenders You need not limit yourself to the stat blocks above, of course. These simply work well as straightforward creatures easy to reskin, suitable when you need several monsters or minions to support a more powerful boss. MODIFYING FEATURES Often, you don’t need to make any other changes to reskin a stat block into a new monster. Sometimes, though, you’ll want to add more details, whether you do it before or during the game. Powerful tomb guardians (reskinned fire giants) clearly have the undead type. But unless they’re hit with poison attacks or abilities such as Turn Undead, you can worry about adding the features associated with undead creatures as needed. You might start off by writing down those features on an index card, on a sticky note, or in whatever digital tool you use to take notes. The “Common Monster Type Templates” section of “Building a Quick Monster” on page 4 breaks down features and traits for undead and many other monster types. Additionally, the more experienced you become, the easier it gets to improvise these sorts of features on the fly. If you’re changing saving throws, adjusting attacks or abilities, or changing the scope of magical effects in a stat block, you might want to write those changes down as well. You’re only taking these notes for yourself, though, so they don’t have to be pretty. You’re the only one who needs to understand these shortcuts. ADD SPELL EFFECTS AND MAGIC Adding spell effects and other magical abilities to reskinned monsters is a fantastic way to customize them, granting access to hundreds of predesigned thematic sets of mechanics that can be easily applied to your monsters. You can change up any creature by giving them one or more uses of a particular spell. The reskinned giant octopus playing the part of an otherworldly horror as described earlier will be much more thematic if they can cast darkness or black tentacles. However, when adding new magical features, ensure these are features your new monster needs and can actually use. Monsters are often limited by the numbers of actions they can take, so be careful that magic used as an action doesn’t simply replace the thematic actions that define a creature. As an example, spiritual weapon is a good spell to give an assassin reskinned as a priest, because it’s only a bonus action to cast. As such, it won’t interfere with the assassin’s ability to make Shortsword attacks fueled by their signature Sneak Attack and Assassinate traits. (“Understanding the Action Economy” on page 42 has more information on this topic.) ADDING FEATURES JACKIE MUSTO Instead of—or in addition to—modifying the features of your reskinned monster, you can add new features to an existing stat block to give a creature new mechanical flavor over and above the baseline reskinned monster. For example, you might add some fire damage onto a reskinned veteran’s Longsword attack, or give a fire giant reskinned into an undead guardian an aura that deals necrotic damage to creatures who hit the guardian with melee attacks. Monster powers built for specific sorts of creatures can help your reskinning efforts. A bugbear reskinned as a zombie is far more convincing when you give them the Undead Resilience power. A topiary in a magical garden that comes to life in the shape of a dragon can become truly draconic with the Poison Thorns or Grasping Roots powers. “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22) all present new monster power options that you can add to your foe of choice. 51 To make them even more usable, some spells can easily be converted into traits. For example, the blink spell used as an always-on trait creates a creature able to move between dimensions the way a blink dog does. A foe created from or armored by magical glass might automatically activate the mirror image spell as a trait at the end of each long rest, with that spell’s duplicates rendered as panes of glass the heroes must smash. When an ooze moves, they might leave behind the effects of a grease spell, just as a creature reskinned as a monk might be able to use jump and feather fall as inherent traits rather than spells they cast using an action or reaction. ESSENTIAL ADD-ON SPELLS The Add-On Spells table sets out a list of spells that work well as add-ons to any monster, organized by level and indicating whether the spell is focused on dealing damage, on defense, or on control. When needed, use a spell attack bonus of 4 + 1/2 CR for the monster using the spell, and a spell save DC of 10 + 1/2 CR. You might consider changing the type of action required to activate spells normally cast as an action. Letting a creature activate such a spell as a bonus action, or as one of several attacks they can make with their ADD-ON SPELLS Spell Level 52 Type Action 1 Spell Burning hands Damage Action 1 Guiding bolt Damage Action 1 Hellish rebuke Damage Reaction 1 Inflict wounds Damage Action 1 Shield Defense Reaction 1 Sleep Control Action 2 Acid arrow Damage Action 2 Darkness Control Action 2 Invisibility Defense Action 2 Misty step Defense Bonus action 2 Scorching ray Damage Action 2 Shatter Damage Action 2 Spiritual weapon Damage Bonus action 2 Web Control Action 3 Counterspell Control Reaction 3 Dispel magic Control Action 3 Fireball Damage Action 3 Lightning bolt Damage Action 3 Spirit guardians Damage Action 4 Blight Damage Action 4 Fire shield Damage Action 4 Greater invisibility Defense Action 5 Cone of cold Damage Action 6 Chain lightning Damage Action 6 Circle of death Damage Action 6 Disintegrate Damage Action 6 Harm Damage Action 7 Finger of death Damage Action Multiattack action, helps them use these abilities without reducing what else they can do. Just be careful that doing so doesn’t increase a creature’s damage output significantly. (“Building Spellcasting Monsters” on page 34 has more information on this topic.) MASHING UP MULTIPLE MONSTERS One further level of reskinning involves mashing together two monster stat blocks. You can think of this process as something like using one monster stat block as a template for another. This process works best when using the more complicated stat block as a baseline, and modifying it with traits from another simpler stat block. For example, if you want a fire giant death knight, use the death knight stat block first (the more complicated of the two) and add fire giant features like Huge size and immunity to fire damage. If you’re feeling nasty, you might also bump the damage the death knight deals with their Longsword attack from 9 slashing damage to the fire giant’s 28 damage. Knowing that the fire giant is significantly bigger means that the fire giant death knight probably has more hit points than the baseline death knight. But instead of doing a lot of math to calculate new hit points with a d12 Hit Die instead of a d8, just increase the death knight hit points by 50 percent. Always remember that you’re building a one-off monster, not a creature you plan to publish. Rough changes save you time better spent elsewhere in your preparation. DESCRIBING RESKINNED MONSTERS The key to making a reskinned monster work is how you describe your new creature in the game. You’ll want to lean heavily on your narrative, focusing your descriptions on the parts of the monster you’ve reskinned most directly. Describe the aura of necrotic horror surrounding the undead fire giant. Add the details of the tattoos the thick-necked bodyguard of the guildmaster wears. Lean in on the description to make a new monster come alive. Do the same thing with your narration of the reskinned creature’s attacks. If an adult-red-dragon-turned-sorcerer attacks with the dragon’s breath weapon, describe how the sorcerer’s body erupts with burning veins, and how they unleash a blast of fire hotter than any natural source as they extend their hands toward the characters. How we narrate our monsters is critical to helping the players think past those monsters’ game mechanics. As such, it’s particularly crucial when we reskin one monster to incorporate the mechanics of another. THE RELATIVE WEAKNESS OF HIGH-CR MONSTERS Challenging high-level characters is much harder than challenging low-level characters. It often takes more monsters than expected—and often of a higher-thanexpected CR—to push high-level characters to their breaking point. A number of low-threat monsters can kill a 1st-level character with one hit, but it’s nearly impossible for most high-threat monsters to do the same to a 20thlevel character. CHARACTER GROWTH Characters in 5e don’t just grow linearly when they increase in level. In addition to more hit points, higher attack bonuses, and increased damage, they also gain new features. They increase the number of things they can do with their actions. They gain new defenses and become more versatile, working even better as a group. Though a level ranging from 1 to 20 represents a character’s relative power, 10th-level characters aren’t just twice as good as 5th-level characters—they’re better in entirely new ways. They have spells and class features that can completely upend a battle, accomplishing with a single action what might have taken significant effort at lower levels. This faster-than-linear growth continues all the way to 20th level, and spikes at levels where characters gain additional attacks and access to more powerful spells. By 20th level, characters are able to mitigate incredible amounts of damage, and to dish out far more damage than most monsters can keep up with. Challenging a group of 20th-level characters is thus much harder than challenging a group of 4th-level characters. The game’s standard encounter-building guidelines don’t keep up. Neither does the general concept of challenge rating as 5e presents it. A CR 1 dire wolf might be an effective challenge against a group of four 1st-level characters, using the basic guidelines for what CR is supposed to represent. But against four 20th-level characters, a CR 19 balor isn’t nearly as dangerous. (See “What Are Challenge Ratings?” on page 99 for more on this topic.) THE LINEAR GROWTH OF MONSTER CHALLENGE Although players often choose optimal new spells and features as they increase in level, they continue to face monsters who use average statistics. Unlike characters, monsters largely are linear creatures. And by virtue of the way monsters are designed, any special features they gain by virtue of a higher challenge rating have a cost toward that challenge rating. Using the game’s standard monster-building rules, if a creature has the Magic Resistance trait to grant it advantage on saving throws against magical effects, that creature’s defensive challenge rating increases. If a creature has Legendary Resistance, its defensive CR goes up again. A monster’s CR increases the more special features they have—yet monsters need those features to stand any chance of challenging higher-level characters. As a result of this, monsters don’t typically hit as hard or have as many hit points as expected at higher challenge ratings. Even worse, features and traits that affect a creature’s calculated CR are often weighted high. For example, the wight has a Life Drain attack calculated into their damage output even though they can’t effectively use that attack while also attacking to full effect with their longsword. Life Drain thus pulls down the wight’s effective damage output below their challenge rating’s expected effectiveness. (An easy fix for this is to give the wight a damage boost on their Longsword attacks with the Damaging Weapon power, part of “Building a Quick Monster” on page 4, or a similar effect.) It’s also worth noting that a creature’s challenge rating is based on the idea that they hit with all attacks, and that all saving throws against their attacks and features fail. This often works out at lower levels, but the more powerful the characters are, the more easily they can avoid attacks and pull off saving throws even against high DCs. A character’s proficient saving throws go up relatively linearly as they increase in level, but all their saves get much better when they’re near a paladin ally and their Aura of Protection feature. KEEPING THREATS HIGH The more experienced you are at running 5e games, the easier it becomes to improvise challenging battles without checking any table or other reference. You quickly become aware when a monster is hitting below their expected challenge compared to the characters, at which point, you can use the other sections of this book to bring that challenge back up. The Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4) helps you create a baseline for the expected hit points and damage of a creature at a given challenge rating. If you feel like a foe isn’t holding their own, you can adjust their hit points and damage to provide a threat more appropriate to their CR and their place in the world of your game. Beyond base damage, you can look to the monster powers in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22) to boost a creature’s effectiveness in combat. And “Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” (page 67) and “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” (page 70) offer different approaches to determine encounter difficulty that scales higher as the characters increase in level. 53 RUNNING MINIONS AND HORDES A powerful sword fighter stands atop a hill, surrounded by a horde of murderous brigands. A cleric braces herself against an ancient sarcophagus, holy symbol held aloft, while hundreds of skeletons swarm around her. Five heroes stand in a narrow passageway, facing down an army of charging cultists. Fantastic stories often place heroes in the paths of dozens or even hundreds of foes. Most of us have had the experience of reading or watching as those heroes cut through the opposing hordes, sending foes flying through the air as they smash through enemy ranks. Unfortunately, the default 5e combat rules offer little practical help for running dozens to hundreds of creatures against a group of heroes. So this section offers several different approaches to running numerous low-threat creatures against a single party. These aren’t mass-combat rules in which large groups of monsters fight each other. Rather, these tips focus on a small group of powerful heroes fighting a great horde of foes. BUILD YOUR HORDE RULESET Attempting to run large groups of monsters with existing rules typically breaks down in two areas: tracking damage and managing die rolls. As such, many of the guidelines in this section focus on two things: • Rules for tracking damage done to creatures fighting as a horde • Rules for managing attack rolls and saving throws for large numbers of creatures These rules follow certain design constraints, which are worth understanding as you think about which rules to use: • Any rules for horde combat should handle almost any number of monsters. • Rules should use the normal 5e monster stat blocks and combat setup as much as possible. • They should be easy to implement and use. • They should focus on the fantastic and heroic battle going on in the story. • For ease of play, foes taken out during a battle (whether reduced to 0 hit points, hypnotized, made unconscious with a sleep spell, and so forth) are removed from play. • Rules shouldn’t require arduous preparation before use at the table. • They should be understandable to both players and GMs. • They should be easy to remember, so you can use them without having to reference books, tables, or articles online. There’s no perfect way to run hordes in 5e, and all of these optional rules abstract typical 5e combat in some way. Every solution requires trade-offs. As such, some of the different approaches in this section might work better in certain circumstances than others. If you’re mainly worried about tracking damage, you might use 4e-style minions or a single damage tally to avoid managing lots of die rolls. If you find yourself needing to roll attacks or saving throws dozens of times for a group of monsters, you might use the “one quarter succeed” method or try grouping rolls together. You can even switch approaches in the middle of a battle, going with whichever rules help you meet the intent and feeling of the narrative. DESCRIBE YOUR MECHANICS Whatever rules you choose when running hordes of foes, let the players know how those rules work, so they know how to interact with the horde most effectively. Don’t surprise them when the wizard casts fireball against a group of monsters, only to realize they’re all part of one big stat block. Battles against hordes aren’t typically intended to challenge the characters in the way that waves of more potent attackers are (as talked about in “Building and Running Boss Monsters,” page 31). Instead, fighting hordes is all about cleaving through foes, blowing groups of enemies sky high, and looking awesome while doing so. LEAN INTO NARRATIVE 54 Setting up a spectacular scene of action requires solid in-world descriptions to show the players the results of their characters’ actions. Describe what it looks like when a fireball spell explodes in the midst of the horde. Describe how the fighter’s blade cleaves through three skeletons, destroying them all in one fell swoop. Use in-world descriptions to make the battle against the horde feel like the cinematic action scene you want to represent. ROUND HIT POINTS When considering the hit points of creatures who are part of a horde, it’s far easier to deal with the math if you round those creatures’ hit points to the nearest 5 or 10. An average zombie has 22 hit points—so make that 20. An average skeleton has 13 hit points, so round up to 15 or down to 10, depending on how challenging you want them to be. This trick works regardless of which style of hit point tracking you choose for your horde (as discussed below). TRACKING DAMAGE 4E STYLE In the fourth edition of Dungeons & Dragons, a minion was a special type of creature with all the baseline statistics of a normal creature—and only 1 hit point. To offset this lack of hit points, a minion didn’t take damage if they were missed by an attack, even if that missed attack dealt damage. (Fourth edition didn’t have saving throws that worked like 5e saving throws, instead using attack rolls for weapon attacks, area-effect spells, and other damaging effects.) This meant never needing to track the damage dealt to a minion, since the first damage dealt by a hit killed them. To use the same sort of approach for a horde of 5e monsters, give those monsters the following trait: many minion creatures as the attack could conceivably hit, subtracting the hit points of each slain monster from the damage of the attack until no damage remains. For example, consider Avantra the paladin hewing into a horde of minion skeletons with her greatsword while using Divine Smite. Each skeleton has 15 hit points, and Avantra’s smite deals 38 damage. The first minion skeleton is destroyed automatically by the successful hit, and Avantra’s player subtracts 15 from the total damage of the attack, leaving 23. That lets the attack hew into the next skeleton, destroying that one and subtracting another 15 damage to leave 8 damage remaining. The attack then cleaves into a third skeleton, destroying that minion foe as well and reducing the remaining damage to zero. THE HORDE DAMAGE TALLY Instead of treating the members of a horde as individual creatures for the purpose of tracking damage, you can track damage done to the horde as a whole. Whenever any member of the horde takes damage, add that damage to an ongoing tally. Round each creature’s hit points to the nearest 5 or 10 to make the math easier. Then each time the tally reaches the hit points of an individual creature in the horde, the last creature damaged is killed and you reset the tally to any damage left over. Additionally, if a single attack deals enough damage to kill more than one monster, let that attack kill multiple monsters in the horde, then reset the tally. Minion. If this creature takes damage when they are hit by an attack or fail a saving throw, they drop to 0 hit points. Using 4e-style minions avoids the need to track the damage dealt to dozens or hundreds of individual foes. A minion still has their normal hit points, but those hit points act as a kind of damage threshold. Any damage dealt to a minion from a missed attack or a successful save that is equal to or greater than the minion’s hit points also drops them to 0 hit points, as does damage from autohit attacks such as the magic missile spell. Likewise, you use a minion’s normal hit points when considering the effectiveness of hit-point-dependent effects such as the sleep spell. You just don’t bother tracking those hit points as the fight unfolds. JACKIE MUSTO CLEAVING MINIONS You might also choose to allow the characters’ weapon attacks to cleave through minions in a horde, giving melee and ranged characters the same awesome feeling of hewing down monsters that a wizard gets by throwing a fireball spell. Whenever a character kills a minion with a weapon attack, if the amount of damage dealt by the attack is greater than the minion’s hit points, subtract the minion’s hit points from the damage dealt and let the attack carry through into the next minion in line. Repeat this process for as 55 For example, imagine Thorgrim the fighter and Selvara the ranger facing ten zombies, each with 20 hit points. Thorgrim makes three attacks, hitting all three times and dealing 12, 11, and 18 damage on each hit. But instead of applying the damage to individual zombies, tally it up as the total damage dealt to the zombies overall—41 damage, enough to destroy two zombies. Those two drop, and the damage tally is reset at 1 point of damage remaining. Next, Selvara fires three arrows, dealing 9, 13, and 17 damage on three hits. Her 39 damage is added to the tally to increase it to 40—enough to destroy two more zombies, and dropping the tally to 0. When tracking damage for hordes, write down the base hit points of a single creature in the horde as a reference, the number of creatures remaining, and the current damage tally. It might look something like this: Zombies (20 hp) × 6: 0 damage When a horde of creatures is hit with a high-damage area attack, rather than using the tally, it’s often easier to simply remove all the creatures affected by the attack if doing so makes sense. For example, if a wizard casts fireball against twenty skeletons with 15 hit points each, it’s easier to remove all the skeletons than to figure out which ones of them might have one or two hit points remaining. MULTIPLE ATTACKS AND SAVING THROWS 56 Based on the physical circumstances of a horde battle, it’s often the case that only a handful of foes can attack a single character, even if hundreds of those foes are in the horde. If creatures are making between four and six attacks against a single character, you can still roll individually for those attacks. But save yourself time by calculating your target number before you roll. Ask the player of the character under attack for their character’s Armor Class, and whether they plan to use any abilities or spells to boost it (such as shield). Then subtract the attack modifier of the attacking creatures to get a target number for the d20 roll—the minimum number the attacker would need to roll in order to hit normally. You roll one die for each creature attacking the character, compare to the target number, and count the successes. Multiply the successes by the amount of damage the attacking creature deals, and you have the total damage dealt to the character. Consider using the same technique when enemies make saving throws. If a single effect requires multiple creatures to make a save, ask the player for the save DC and subtract the saving throw modifier of the monster to get the target number. Roll the appropriate number of d20s based on the number of creatures affected, and see how many succeed. When a number of creatures in a horde act at the same time and force one character to make multiple saving throws, have the character make a single saving throw with disadvantage against the effect. ONE QUARTER SUCCEED With a horde of sufficient size, the number of attack rolls or saving throws needed might simply be too many. So instead of rolling for those attacks and saves, assume that one quarter of the creatures in a horde succeed on attacks or saving throws. For example, if a wizard casts hypnotic pattern in the middle of a horde of twenty raging orc mercenaries, assume that five of them succeed on the saving throw and the other fifteen are hypnotized. This “one quarter succeed” abstraction is fast enough to use for hundreds or even thousands of foes, and doesn’t get any harder to use as the number of creatures increases. You can increase or decrease the number of monsters who succeed based on the circumstances of the situation. For attacks against a character who’s particularly well armored or who casts shield, or if most or all foes have disadvantage on their attack rolls, assume that one in ten attack rolls succeed. Use the same guideline for horde saving throws if specific effects hinder the saving throws of creatures in the horde, or if something has boosted the power of the characters’ features that require saving throws. If there’s enough variance in power level between the characters and the creatures of the horde, such as a 20th-level wizard dropping a meteor swarm spell on two hundred manes, assume that all creatures within the area fail their saving throws. A 12th-level cleric might simply destroy every skeleton surrounding them with the radiant force of their Turn Undead feature, or leave one or two survivors. Because horde battles often involve edge cases such as part of a group being caught by a hypnotic pattern spell, or a bunch of undead who are turned but not destroyed, work with your players and within the intent of your game’s narrative to adjudicate such cases as they come up. Lean into decisions that make the scene feel epic. COMBINE ROLLS If you prefer some dice rolling to anchor the action in your game, combine the foes of a horde into smaller groups, then make one attack roll or saving throw for each such group. You can put creatures into groups of four, ten, or any number that makes sense against the size of the horde. When you make one attack roll or saving throw for the group all at once, use the attack modifier or saving throw modifier of one creature in the group, and add the damage of all creatures together if the combined attack hits. For example, a cleric might use her Turn Undead feature on a horde of twenty wights. Instead of rolling twenty saving throws, combine the wights into groups of five so that each group makes one save. On a failed save, all five wights in a group are turned. Likewise, if nine wights attack the cleric, put them into groups of three, roll three attack rolls using the wight’s normal attack modifier, and combine the damage of all three wights in a group. Even though wights get two attacks each, you can combine the damage from both attacks as part of this abstracted approach—14 damage per wight for 42 damage per group. You can also use this approach to make mass attack rolls, rolling two attacks for an entire horde. Each attack uses the attack modifier of the type of creature in the horde, and deals one quarter of the total damage of the horde. For example, if ten skeletons attack a paladin, you could roll two attacks at a +4 bonus (the skeleton’s attack modifier). Each attack that hits deals 12 damage—one quarter of the 50 points the ten skeletons can deal in total, with their Shortsword attacks dealing 5 damage each. Like the “one quarter succeed” guideline, this twoattack rule scales for a horde of any size, and requires just a little math to compute the total damage dealt. HORDE MONSTER STAT BLOCKS Another common approach to handle hordes of creatures is to combine multiple creatures together into a single stat block resembling a much larger creature. This lets you run hordes the same way you run any normal big monster, akin to how a swarm of rats represents multiple rats. For this approach, choose a challenge rating for the horde and build the stat block for that challenge rating. You can use the information in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4) to build a stat block in a few minutes, or reskin an existing stat block to represent your horde. Rather than a single stat block, you can also create multiple stat blocks to represent groups within a larger horde. For example, a horde of sixty skeletons might be broken up into four group stat blocks representing fifteen skeletons each. If you’re not sure what challenge rating to use for a horde, try multiplying the challenge rating of the creatures in a horde or horde group by the number of creatures, rounding up for creatures with challenge ratings less than 1. For example, a horde of fifteen skeletons with a challenge rating of 1/4 would have a CR of 3.75, rounded up to 4. To represent a hoard of creatures, add the following trait to the base stat block of the creatures in the horde: Horde. The horde can occupy another creature’s space and vice versa, and can move through any opening large enough for the horde’s base creature to move through. The horde can’t regain hit points or gain temporary hit points. Damage dealt by the horde is halved when the horde has half of its hit points or fewer. One problem with horde stat blocks is that attacks affecting a large area often work less well against singlestat-block hordes than they would against the creatures in the horde individually. For example, a fireball spell is tremendously effective against a group of ghouls, easily cutting their numbers down. But when that group of ghouls is represented by a single ghoul horde stat block, that horde remains standing even after a lot of damage. Likewise, casting hypnotic pattern on a horde of bandits either hypnotizes all of them or none of them, depending on whether the horde collectively succeeds or fails on their saving throw. You can help fix this by establishing that damaging areas of effect deal double damage, or that an area of effect controlling many creatures instead deals damage to a horde’s hit points. But this often isn’t as rewarding to the players as describing the characters actually tearing through or controlling a big pile of foes. If you use single stat blocks to represent hordes of monsters, let your players know, so they know what to expect and can choose the right actions given the mechanics you’re using for the horde. CHOOSING HORDEAPPROPRIATE CREATURES Certain foes work better in a horde than others. Often, weaker monsters make more sense for a horde than stronger ones—a good thing for the characters facing them. Your story often dictates what kinds of creatures normally attack in large groups, whether skeletons, bandits, guards, orcs, goblins, kobolds, or similar foes. If your story calls for a particularly strange horde of creatures, consider reskinning an existing horde-friendly stat block as a starting point. “General-Use Combat Stat Blocks” on page 13 offers some simple examples. If a single horde is made up of different types of creatures, use a single stat block for all those creatures, then describe them differently in the narrative. Trying to manage two separate stat blocks for multiple hordes of monsters quickly becomes complicated. For creatures with multiple attacks, combine those attacks into one attack roll that deals the creature’s total damage. For example, each veteran in a horde of veterans combines their Longsword attacks from Multiattack into one attack dealing 14 damage (or 20 damage if you decide they’re using their Shortsword attack too). Ignore bonus actions, reactions, and special attacks for creatures in a horde. If a creature deals some sort of ongoing damage, add that damage to its regular attack, but ignore other damage and effects. If a horde of creatures has a damage-dealing attack requiring a saving throw, let a character targeted by that effect make a single saving throw against it with disadvantage. SWITCH RULES AS NEEDED All the guidelines in this section are intended to make it easier for you to run large numbers of monsters. But at some point, you can stop using them when they no longer serve this purpose. This doesn’t have to be an all-at-once process, though, as many of the guidelines above can be used, and removed, independently. You might switch from using “one quarter succeed” for large numbers of monsters to “combining rolls” when fewer are in play. You might use a damage tally at the start of a horde battle, then switch to tracking damage independently when only a handful of foes are left. You might start with a single stat block used to represent a group of monsters, then “explode” that horde into a handful of individual monsters when the horde’s hit points are low enough. 57 RUNNING SPELLCASTING MONSTERS Whether an NPC mage or priest, or a monster innately channeling potent magic, spellcasting foes create great flexibility for a GM wanting to challenge players and characters in combat. But that flexibility comes at a cost. Spellcasting is one of the most complicated subsystems in the game, which can make running spellcasting creatures a challenge. Even stat blocks that focus the magic of creatures and NPCs into one or two fully broken-out key features usually come with a list of other spells the foe can use. But because using one of those spells often means that a GM needs to look up its details, a foe’s key features can end up overused, while potentially interesting spells from the spell list languish. The following guidelines can help create a better experience running spellcasting foes. LEARNING MAGIC Whenever you review the stat blocks of your favorite spellcasting creatures, whether as part of game prep or just for fun, make yourself familiar with their spells by making notes on those spells. The act of making notes, whether handwritten or electronically, reinforces memory in a much stronger way than simply reading. So by taking down the details of interesting spells on index cards or in an app, you help to fix those details in your memory— even as you give yourself a useful tool for playing and adjudicating those spells on the fly. GMs who have the ability to see stat blocks and look up spells electronically might not see the value in this. But consider that clicking through to read the full text of wall of force creates a need to parse out the important information from the spell description, which takes time. However, making a note saying, “Any angle; dome or sphere 10-foot radius; flat surface ten times 10-by-10; immune to all but disintegrate,” gives you that information at a glance when you need it quickly. A SUITE OF SPELLS Throughout multiple editions of the game, a number of spells have become classics—because they work. Fireball, lightning bolt, command, hold person, wall of force, and many more are the cornerstone of combat spellcasting, and appear in numerous creatures’ stat blocks. So when you’re making notes on the spells of your favorite creatures, keep an eye out for spells that appear over and over again, as well as spells you think should be used more often. Then use the notes you make for those selections as a suite of combat-friendly spells you know, like, and can use easily in your game. As GMs, we often put a certain amount of pressure on ourselves to make sure every combat encounter feels 58 unique, but don’t let that force you into using unfamiliar spells that can slow down play and make running combat a chore. On the other side of the table, the players of clerics, wizards, and warlocks will be making use of repeat castings of spiritual weapon, eldritch blast, and fireball encounter after encounter without a care, so cut yourself the same slack. In a pinch, a spellcasting creature you haven’t had time to fully prep can make use of spells from your creature caster suite even if those spells aren’t normally on their spell list. Just make sure that the spells you use match the level of spells normally available to the creature. QUANTITY AND VARIETY The number of spells in your creature casting suite is up to you, but try to have enough that you can go a few encounters—or even a couple of sessions—without repeating yourself. In an ongoing campaign against death cultists, two encounters against mini-boss high priests who favor flame strike might feel flat. But if one priest specializes in flame strike while the other loves to harry foes with insect plague, you keep the characters and the players on their toes. MIXING THINGS UP Knowing that you have your creature casting suite set up and ready to run, you might then pick one new and unusual spell to prep in each session. By being able to deal quickly and easily with most of the spells your foes use, having to reference one spell while under the stress of running combat is an easier task. And who knows? If you have fun with that new spell, it might become another addition to your creature casting suite for future games. SPELL SKINS “Reskinning Monsters” on page 50 talks about the ease and usefulness of reskinning stat blocks to let them pose as new and unique creatures. Even if you’re not reskinning any other part of a stock creature, reskinning spells is a particularly easy way to add new combat spice to familiar foes. This technique works well with the spells of your creature caster suite, which can be quickly reflavored to make it feel as if foes have access to an even wider range of magic. DAMAGE TYPES Trading out damage types is the first and most straightforward approach to reskinning spells. Enemy mage casting fireball? Been there, done that. But when that mage unleashes sphere of ruin, a reskinned fireball that deals necrotic damage, the fight potentially gets a bit more interesting. Each of the standard damage types is intrinsically connected to many classic spells, so swapping damage types makes a unique statement about a creature’s magic. Likewise, changing up damage is a great way to work with a theme for spellcasting foes, whether it’s dark priests primarily channeling necrotic damage, elemental-adjacent creatures favoring cold and fire damage, or an order of storm mages specializing in destroying enemies with thunder and lightning. Damage Type Acid Bludgeoning Example Spell Acid arrow, acid splash Arcane hand, control water Cold Cone of cold, ice storm Fire Burning hands, fireball Force Disintegrate, magic missile AREAS OF EFFECT Many classic offensive spells are tied to specific types of areas, from fireball’s 20-foot-radius sphere to fear’s 30-foot cone. Changing up a spell’s area is thus an easy way to make it feel as though a spellcasting creature has a special edge. When you change a spell’s area, just make sure you keep the number of possible targets roughly the same so as to not seriously increase or decrease the threat of the spell. In general, when a spell targets only creatures standing on a level surface, as opposed to flying creatures who might stack on top of each other in the area of effect, you can use the following table to convert different types of areas. To use the table, look for the area of the spell you want to convert in the leftmost column, then read across to the cell under the type of area you want to convert to. Lightning Lightning bolt, shocking grasp Necrotic Blight, finger of death Piercing Insect plague, spike growth Poison Cloudkill, poison spray Cone Psychic Feeblemind, phantasmal killer Radiant Guardian of faith, sacred flame Slashing Blade barrier, wall of thorns Thunder Shatter, thunderwave SAVING THROWS Changing up saving throws is another easy way to mix things up spell-wise, and can go hand-in-hand with retooling damage. Spells whose effects need to be physically avoided, including acid, cold, and fire damage, often make use of Dexterity saving throws. But if you finetune the description of a spell’s effect so that it instead overwhelms targets with destructive power, a Strength or Constitution save can represent trying to shrug off the worst effects of the spell. Mental saving throws can also be easily swapped around, with only a subtle difference between a character calling on Intelligence to resist their mind being overwhelmed, Wisdom to keep their will focused, and Charisma to remain grounded in their sense of self. Saving Throw Good for… Strength Resisting crushing effects, ignoring forced movement Dexterity Rolling with area-effect damage, avoiding hurled effects Constitution Resisting necromantic or poison effects, maintaining bodily autonomy Intelligence Resisting illusions, shrugging off psychic effects Wisdom Resisting charms, shrugging off mind control Charisma Resisting spiritual effects, shrugging off emotional control Cone Cube or Square Cylinder, Sphere, or Circle Line* — Size ÷ 2 Size ÷ 2 Size × 3 Cube or square Length × 2 — No change Length × 6 Cylinder, Sphere, or Circle Radius × 2 No change — Radius × 6 Line* Length ÷ 3 Length ÷ 6 Length ÷ 6 — * These conversions assume a line 5 feet wide. For each additional 5 feet of width, divide the line’s length by 2. For example, the 20-foot-radius area of a fireball or ice storm spell could be converted to a 40-foot cone, a 20-foot cube or square, or a 120-foot line that is 5 feet wide. VARIETY, NOT PUNISHMENT In the course of reskinning spells to mix things up in combat, be careful that these approaches don’t end up accidentally—or intentionally—punishing characters for their defensive strengths. If all foes cast their spells with areas of effect that conveniently fill whatever room the characters are in, it’ll start to feel punitive. Likewise, if the rogue has Evasion and the barbarian has resistance to everything except psychic damage, a lot of fun gets sapped from the game when enemy spellcasters tee up mindball and cerebral bolt instead of fireball and lightning bolt, dealing psychic damage and calling for Intelligence saving throws round after round. 59 USING NPC STAT BLOCKS Of all the monster stat blocks GMs have at their disposal, NPC stat blocks offer tremendous utility. Because many games prominently feature nonplayer characters as villains and opponents, a crafty GM can squeeze the most value out of NPC stat blocks with a few simple guidelines. INHERENTLY RESKINNABLE STATS Though any monster stat block can be easily reskinned into a unique creation, NPC stat blocks make particularly useful baselines for reskinning because of their general utility. Simply change the creature type and the flavor, and you can easily turn an NPC into an undead horror, an otherworldly fiend, a commanding goblinoid, or many other monstrous foes. (“Reskinning Monsters” on page 50 has more information on this topic.) NPC stat blocks are likewise easy to reflavor. Change their weapons, their armor, and their mannerisms and you have an entirely new NPC. Every veteran can be unique, with personalized armor and a sword tied to a distinct history. Reskin and reflavor an NPC spellcaster’s spells and damage types, and you can quickly create acidic sorcerers, ooze-worshiping cultists, psionic adepts, and archmages of the infinite void. Such changes are often easy enough to do in your head, making it easy to improvise unique foes during your game with the same simple NPC stat block. BUILD MONSTROUS NPCS It’s easy to forget the wide range of potential creature types you can wrap over an NPC stat block. Humans, elves, dwarves, and the other common humanoid ancestries are obvious choices for NPCs, but goblinoids, orcs, drow, giants, skeletons, zombies, and ghouls fit just as easily. Making a quick change to a monster’s type, and adding an ancestry trait if desired, is all that’s needed to turn a common NPC stat block into a huge range of potential foes. You can also look to the monster powers presented in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22) for further quick customization. TEMPLATING 60 For more utility from NPC stat blocks, consider using them as templates that can be customized with the traits of other creatures—or vice versa. This is a great way to add a social role to a monster, or to give monstrous foes the feel of having class levels. Want to turn a typical duergar into a duergar veteran? Take the duergar’s most defining traits and add them to the veteran stat block. Want to create a stone giant archmage? Take the archmage’s Spellcasting feature and add it to the stone giant stat block. A doppelganger scout, a goblin noble, a troll priest—any such combination gives you a huge range of options to turn existing monsters into foes who feel more like characters. When mashing up stat blocks in this way, add features of the simpler or weaker stat block to the baseline stat block of the more powerful or complex creature. In the case of the stone giant, their physical ability scores, Armor Class, and hit points are higher than the archmage’s, so it’s easier to add a high Intelligence and spellcasting (the primary feature defining the archmage) to the stone giant stat block than it would be to take the baseline archmage and add the stone giant’s dominant features. WORRY LESS ABOUT CR If you can’t find an NPC stat block at the exact challenge rating you want, it’s often easier to just use the nearest existing stat block that fits the story of the NPC. A few points of CR up or down doesn’t make a huge difference in the story. If you’re worried an encounter might be too easy or too hard, you can add more NPCs or reduce their numbers as you need. You can go especially far with the baseline CR 3 veteran stat block, which works well against characters as low as 2nd level (with the veteran serving as a powerful elite foe), all the way to 15th level (where hordes of veterans still provide a challenge). If you want to fine-tune an NPC’s stat block for a different challenge rating, you can use the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4) to upgrade or downgrade an NPC like any other stat block. Just replace the NPC’s hit points and attack numbers with those in the table for your desired CR. Recalculate their damage either by changing their number of attacks or replacing those attacks with the attacks in the table. Likewise, if the NPC has attacks or features that require a saving throw, replace the stat block’s save DC with the table’s value. ADD ONE SPECIAL TRAIT To make nonplayer characters stand out, use a default NPC stat block but add one unique feature for particular NPCs. Maybe you change a mage’s fireball into an acidic or necrotic blast. Or you could create a corrupting sphere spell that creates a temporary hole in the world, through which demons claw at those trapped within—still doing fireball-appropriate damage, but with some fancy reskinning. A veteran serving a necromancer might bathe her blades in necrotic flames, dealing an extra 3 (1d6) necrotic damage on each hit. A psionic spy might add 7 (2d6) psychic damage to their Shortsword attack. Or to make NPCs even more memorable, you can use any of the monster powers in “Building a Quick Monster,” “Monster Powers,” or “Monster Roles,” tailoring a generic stat block even more to the story you want to share. BOSSES AND MINIONS When creating a boss battle, thinking about which bosses pair well with which minions can be a great starting point. You can use the table below to match up minions and bosses in a number of classic adventure environments. Boss CR Boss For unique bosses, look to “Building and Running Boss Monsters” (page 31), as well as the monster powers in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22). Environments Minions 1 Goblin boss Caves, mountains Goblins, worgs 2 Bandit captain Cities, sewers, ruins Bandits, spies, thugs, berserkers, gladiators 2 Cult fanatic Cities, ruins Cultists, bandits, thugs, dretches 2 Ettercap Caves, ruins Giant spiders 2 Ghast Ruins, crypts, cities, sewers Ghouls, zombies 2 Gnoll pack lord Plains, caves, ruins Gnolls, hyenas 2 Ogre Ruins, caves Orcs, goblins 2 Sea hag Coves, swamps, grottos Giant constrictor snakes, crocodiles 3 Bugbear chief Keeps, fortresses, ruins, caves Bugbears, goblins, worgs 3 Green hag Forests, swamps Bullywugs, giant toads, giant constrictor snakes, imps, quasits 3 Winter wolf Frozen mountains, frozen ruins Dire wolves, ice mephits 4 Banshee Ruins, crypts Specters, skeletons 4 Bone naga Ruins, crypts Skeletons, specters, wights 4 Ettin Mountains, ruins, caves Ogres, orcs 4 Lamia Ruins, towers, caves Jackalweres 4 Lizard king/queen Swamps, sunken grottos Lizardfolk shamans, lizardfolk, monitor lizards 5 Hill giant Mountains, ruins, caves Ogres, orcs, bugbears, goblins, cave bears 5 Night hag Ruins, crypts, Lower Planes Hell hounds, quasits, manes, shadow demons 5 Sahuagin baron Coves, grottos, underwater ruins Sahuagin priestesses, sahuagin, reef sharks, giant octopuses, krakens 5 Wraith Ruins, crypts Flameskulls, specters, wights 6 Hobgoblin warlord Ruins, keeps, fortresses Hobgoblin captains, hobgoblins, bugbears, goblins, worgs 6 Mage Towers, cities Animated armor, imps, acolytes, flesh golems, veterans 6 Medusa Ruins, caves Basilisks, giant constrictor snakes, death dogs 7 Oni Ruins, caves, cities Hobgoblins, orcs 8 Frost giant Frozen mountains, frozen ruins Yetis, young white dragons, polar bears, winter wolves 9 Fire giant Volcanoes, caverns Hell hounds, young red dragons, salamanders, azers, fire mephits 9 Glabrezu Lower Planes, ruins, towers Barlguras, chasmes 10 Aboleth Caverns, coves, lakes Chuuls, cult fanatics, hydras, NPCs (enthralled), sea hags 11 Efreeti Ruins, volcanoes, cities, deserts Fire elementals, salamanders, fire snakes 11 Horned devil Lower Planes, ruins, towers Barbed devils, bearded devils, spined devils 12 Archmage Towers, cities Animated armor, imps, cambions, demons (any), elementals, golems 13 Adult white dragon Frozen mountains, frozen ruins Yetis 13 Vampire Ruins, crypts Vampire spawn, giant bats, dire wolves, specters, wights 14 Adult black dragon Swamps, sunken grottos Giant crocodiles, trolls, bullywugs, lizardfolk, kuo-toa 15 Adult green dragon Forests, ruins, caverns Treants, elves 15 Mummy lord Ruins, crypts Mummies, skeletons, wights, cult fanatics 16 Adult blue dragon Deserts, ruins, towers Air elementals, mages 16 Marilith Lower Planes, ruins, towers Hezrous, vrocks 17 Adult red dragon Mountains, volcanoes, ruins, caverns Fire elementals, kobolds 17 Death knight Crypts, ruins, Lower Planes Wights, wraiths, liches, flameskulls, nightmares, revenants 19 Balor Lower planes, ruins Mariliths, glabrezus, goristros, cambions, cult fanatics 20 Ancient white dragon Frozen mountains, frozen ruins Abominable yetis 20 Pit fiend Lower planes, ruins, towers Horned devils, bone devils, erinyes 21 Ancient black dragon Swamps, sunken grottos Giant crocodiles, trolls, bullywugs, lizardfolk 21 Lich Ruins, towers, crypts, caves Death knights, iron golems, wraiths, mages 22 Ancient green dragon Forests, ruins, caverns Treants, elves 23 Ancient blue dragon Deserts, ruins, towers Air elementals, mages 24 Ancient red dragon Mountains, volcanoes, ruins, caverns Fire giants, fire elementals, kobolds 61 EVOLVING MONSTERS Players usually feel safe assuming that a monster is exactly what the characters see. But what if that monster changes partway through a fight? An evolving monster starts out one way, and then at a specific point in the narrative, raises their threat level significantly. When a monster evolves, GMs are able to catch players by surprise and crank up an encounter’s excitement. The evolution keeps player interest high and communicates a shift in story. Something caused this monster to suddenly change, with new and exciting capabilities! Evolving monsters change the assumptions made about an encounter. For example, players and characters alike know that goblins are skirmishers and easily defeated. But if a goblin drinks a potion and is horribly transformed into an enormous ooze, the nature of the confrontation changes significantly. The threat might feel mechanically similar to an encounter with a goblin and an ooze companion who enters combat once the goblin falls or flees. But the emotional reaction of the players is different. Though any player can enjoy the surprise that comes of seeing a monster in a different light, evolutions work especially well for when experienced players become accustomed to and even bored by familiar creatures. DEVELOP A STRONG CONCEPT Not every monster should evolve. This technique should be used sparingly, and with a strong concept that will feel right to the players. So think through that concept and the reasons for the evolution. STORY Verisimilitude is important, whether the concept is mundane or supernatural. A goblin drank a potion and turned into an ooze … but why did that potion have such a powerful effect? An encounter always works better if the story concept is strong. Perhaps a group of goblin zealots have taken over a tower once inhabited by an eccentric wizard who collected oddities. Stating this up front establishes the story. Mundane evolutions can be just as exciting. A crab might molt, shedding their carapace to grow in size and become more formidable (though probably with a lower Armor Class). A huge spider might have hundreds of baby spiders on their back, something seen in nature. Then THE 2016 D&D OPEN When designing this competitive event, Teos combined a puzzle with an evolving monster. The characters found themselves in a room, sealed with an enormous gnomish contraption containing a metal tarrasque which looked certain to defeat them. Except that each time the characters solved a short puzzle or riddle correctly, the gnomish contraption reassembled the metal creature into a different, easier threat. The next-to-last form? A flumph. The final form? A helpless upside-down flumph. 62 when the spider is hurt, the spiderling swarms advance to change the nature of the fight. Evolving monsters can let you make use of powerful story material, including rebirth, divine transcendence, foolish deals with malevolent forces, or a character taken over by their baser emotions. Such a story can appeal to the players, becoming a significant campaign development, and reinforced through your descriptions of the evolution. A shelled creature might change color before they molt. A creature with the power of rebirth might boast of their immortality and call upon otherworldly magic before being reduced to 0 hit points. EIGHTEEN EVOLVING MONSTERS The following ideas can be used to work up evolvingmonster encounters around many standard types of foes, or as inspiration for creating encounters of your own. Ritual of Transformation. A spellcaster stands within a ritual circle, and is transformed when the ritual is complete. Character actions could change the efficacy of the evolution, perhaps transforming the caster into a different creature than what was intended. Undead Host. An undead creature holds another creature inside them, either living or undead, which emerges once they are defeated. Incorporeal Shift. A corporeal undead refuses to fall, rising from apparent destruction as an incorporeal evolved form—a death knight becoming a powerful wraith, perhaps. Cursed until Death. A monster bears a curse that has transformed them, and that is ended when the characters kill them. This causes the villain to transform into their original form, whereupon they attack again in a state of fear and anger, unable to remember what happened. Sudden Curse. Desperate to defeat the characters, a creature foolishly grabs a cursed magic item or artifact and becomes transformed by it. Molting or Shedding Skin. A juvenile kraken might molt their shell to become an adult, or a giant snake could shed their skin to become even larger. Youthful Vitality. A foe begins a fight as old and frail, but magic in the area begins to rejuvenate them, improving their statistics every other round. Extraplanar Pact. A foe has made a pact with a fiend or other extraplanar entity. The entity either rewards or punishes the foe by transforming them in the middle of battle, or when the foe dies. Wild Magic. Magic in the area is out of control, and changes one or more foes. It might be possible for the characters to undo the change, or even to benefit from it. Power Armor. The foe climbs into a large suit of magic armor partway through the fight, gaining powerful capabilities. Escaped Meal. A creature has swallowed another creature, which they cough up when hurt sufficiently. Both creatures now attack the characters, unless the heroes can win over the newly appeared foe. Empowering Meal. A creature gains the powers of creatures they consume—such as a dragon who swallows an NPC spellcaster and now can cast their spells! Shapechanger. A creature changes shape into a powerful new form when a fight starts to go against them, or was previously shapechanged and reverts to their true form during battle. Illusion Drops. A creature’s appearance is merely a facade, which they use illusion magic to maintain. Once they realize that fighting is the only option, the creature drops the illusion and reveals their true form and actual capabilities. Parasite. A creature is controlled by a parasite. When defeated, the parasite emerges from the creature and attacks—trying to gain a new host. Remembered Power. A foe has repressed memories, letting them tap into their true strength even though they don’t remember having such capabilities. Primal Fury. When wounded, a creature taps into a primal state of being to become more ferocious. Reversible Strength. Due to powerful magic or some other effect, a foe begins a fight far stronger than the characters. The characters can reverse the effect, letting the foe devolve to a form that can be defeated. SHAKE UP THE FAMILIAR Scott points out that players can easily become overly familiar with common monsters, either because they’ve fought them several times or because those players are also GMs with a high level of monster knowledge. Turning a known commodity into an evolving monster is an easy way to transform familiar foes into something new and exciting. But think about adding some kind of clear visual indication—an unusual piece of equipment, an eldritch tattoo, strange demeanor or behavior, and so on— to hint to the players that this isn’t the monster the characters are used to. in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22). Monster powers are specifically designed to be exciting and to surprise players, as well as to communicate story. TRIGGER Think about how the evolution should be triggered. Does it happen when the creature is reduced to half their hit points? When reduced to 0 hit points? When a ritual is complete, or on the second round of combat? The trigger should always fit the story, and should feel inevitable—but shouldn’t feel like you’re trying to fool the characters. If the players feel as though their characters should have MECHANICS Because evolving monsters is a technique to be used sparingly, you want the mechanics of that evolution to be evocative and significant. The mechanical change reinforces the story and the seriousness of what has taken place. CARLOS EULEFÍ STATISTICAL EVOLUTION First, think through the type of evolution and what it represents. Is a creature becoming larger? Are they changing type, such as from humanoid to elemental? What capabilities should the new form have? Depending on the nature of the evolution, you might simply swap creature statistics entirely. A goblin mage becomes an ogre. A dwarf noble becomes a fire elemental. Or you might borrow aspects of one stat block, combining them with the other. For example, you might use the noble stat block but add the fire elemental’s resistances, immunities, and Fire Form trait, as well as having all the noble’s attacks deal fire damage. You can also apply new features or actions using monster powers, as found 63 been able to stop the evolution before it was triggered, a fight might become frustrating rather than exciting. Foes might evolve a single time, or more than once. The evolution could be permanent, or something the characters can prevent or reverse. In the latter case, think through what circumstances would allow this, and which of a monster’s mechanical aspects (such as stat block features) might be lost based on how well the characters succeed on undoing the effect. Foreshadowing a trigger helps establish the story. A villain warns the characters not to strike them down, with their death triggering the transformation, of course. A huge creature has a swollen belly, and striking them causes them to cough up a meal that also attacks the characters. ENCOUNTER DYNAMICS Statistical changes can result in major changes to the dynamic of the encounter. A foe who becomes part spider might be able to walk on the ceiling, avoiding traps and hazards on the battlefield. A foe who becomes part fire elemental can ignore the river of lava in a cavern. Consider matching the evolution with an environment that makes the most of the change, but do so in a way that doesn’t make the battle much harder for the characters. In some cases, a transformation might involve tradeoffs. The monster might gain new abilities, even as they lose former resistances or gain new weaknesses. Either way, though, the expectation is that whatever narrative device allowed a foe to evolve can’t be used by the characters to gain similar benefits. Evolutions are meant for monsters. Monster statistics are different from character statistics, and evolving characters in the same way can have an impact on game balance. Thankfully, there are plenty of other ways to help the characters even the odds against a foe who is suddenly more formidable, as discussed in “Building Engaging Encounters” on page 76. And as a one-off benefit, you can have fun letting an environmental effect grant characters the use of one of the monster powers in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), or “Monster Roles” (page 22). ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE Mike notes that the environment might change along with a monster’s newly evolved form. The world might fall away into a void, or rocks could start dropping from the ceiling as a creature’s evolution disrupts the physical nature of the area around them. A transformation into a fire elemental might set a room ablaze. Such unexpected changes create a truly epic scene. 64 DESIGNING VERAGON When writing the book Fantastic Lairs, Mike, Scott, and fellow designer James Introcaso wanted to provide powerful foes even for the highest-level characters. One such foe was Veragon, a demon-touched ancient gold dragon who was intended to do the impossible—work as a solo monster capable of truly challenging a group of 20th-level heroes. Anyone who’s run 20th-level encounters knows how hard it can be to challenge such characters, who have so many resources at their disposal and so many tricks up their proverbial sleeves that any lone monster, no matter how big, is at a disadvantage. A big part of addressing that challenge was having Veragon evolve as he faced the characters. The dragon has a tremendous 546 hit points, enough to keep him alive even after multiple paladin smites and rogue sharpshooter sneak attacks. For half the battle, he acts as a “standard” ancient gold dragon, though with a big pile of spells he can cast. But when reduced to half his hit points, Veragon turns into something else as his demon-touched nature takes hold. Suddenly, the dragon is throwing around the finger of death spell twice per round, even while surrounded by an aura that chews through characters like a never-ending circle of death spell. But one trick that makes this approach work is that Veragon becomes simpler to play when he switches forms, focusing on those new abilities and his regular attacks, and no longer having all his spells at his disposal in phase two of the fight. Veragon isn’t a simple monster by any means, but when building your own evolving monsters, always keep in mind how to balance increased power with making your monster easy to run at the table. Evolving monsters don’t just need to add new things. They can often take some things away as well. RESOLUTION Evolving a monster can be more than just a fun, oneoff change. It can tie into your campaign or drive up its stakes. A young noble who went missing has been transformed by terrible studies encouraged by the cult threatening the local area. A power that changes people into devils in one encounter might affect other creatures as well, prompting the characters to find the catalyst for the transformation and stop others from being exposed to it. The story impact of an evolution can merit providing some extra time after combat ends so the characters can analyze what took place and learn from it. Story implications, such as an aberrant spy among the nobility, might result in the characters coming up with ideas to detect or counter any other such spies. Think about what manner of resolution works best to make an evolution a strong part of the story. THE COMBAT ENCOUNTER CHECKLIST Sometimes all a game needs is an interesting location and some cool monsters to fight, setting up a combat encounter that a GM might build right at the table. The characters go somewhere, everyone decides it’s time for a fun fight, and you whip something up. Or you determine that, given the circumstances going on in the story, it’s time for the characters to run into some opposition, and you’re off to the races. (“Building a Quick Monster” on page 4 and “General-Use Combat Stat Blocks” on page 13 are great resources when you’re building those kinds of on-the-fly encounters.) Sometimes we need more, though, particularly for big set-piece battles or boss fights. When it’s time to build an interesting and dynamic encounter, the following checklist can help determine what options a big combat might need: • Interesting monsters • A fantastic location • Zone-wide effects • Traps and hazards • Advantageous positions • Interactive objects • Cover • Difficult or fantastic terrain • A goal No battle needs all these things, but it’s worth running through the list to see which options fit the sort of combat scenario you’re putting together. INTERESTING MONSTERS For a big, self-contained combat encounter, a single monster usually won’t do it. Even several monsters of the same type might not prove interesting enough for a big fight. Complex, climactic battles often work best with two or three creature types that work well together—big bruisers up front and powerful artillery in the back, for example. (“Monster Roles,” page 22, has more information about choosing foes this way.) However, having more than three types of creatures in any one battle is going to be hard to manage. As such, designing a big set-piece battle is also a great time to think about waves of monsters (talked about in “Building and Running Boss Monsters,” page 31). A FANTASTIC LOCATION An empty, 50-foot-square room doesn’t lend itself to an interesting set-piece battle. We want fantastic rooms with interesting shapes, lots of room to move around, and a cool environment for the characters to spend time in. Great self-contained fights are like theme parks where the characters can climb up big statues, swing from chandeliers, and dance across elevated platforms. Whether you’re playing online or in person, you can purchase battle maps showing off interesting locations, or might find maps that cartographers have released for free. Build a library of cool maps that inspire your players to enjoy the scenery while they’re kicking ass. However, you want to ensure that your fantastic location isn’t too big. It’s no fun to have a character spend multiple rounds running to the far side of an arena—only to arrive just in time to watch the other characters drop the big bad to the mat. Let all the characters get to the meaty part of a location in two moves at most. ZONE-WIDE EFFECTS Sometimes a combat environment has a big ongoing effect—something that impacts all the creatures in the area, no matter where they are. Such zone-wide effects can make a fight more interesting, as with any of the following examples: • Unholy energy in a crypt makes healing magic only half as effective as normal. • Supernatural fire negates any creature’s resistance to fire, and turns immunity to fire into resistance. • Psychic wailing forces each character to succeed on a DC 10 Constitution check to successfully cast a spell. • Periodic bolts of lightning strike, with each creature in combat having a 1-in-4 chance of being struck at the start of their turn. • An arcane rift causes each damaging spell cast in a fight to deal an extra 2d6 force damage. • An aura of bloody rage fills the area, granting each combatant advantage on attack rolls. • A rift to a realm of chaos causes all spells to trigger a wild magic surge. • The god of blood infuses all melee attacks with an extra die of damage. • A rift in space-time lets a creature swap places with an enemy within 60 feet if that enemy fails a DC 12 Wisdom saving throw. • A thick fog makes it impossible to see creatures more than 30 feet away. Avoid zone-wide effects that are just plain annoying. Having creatures fall down a lot because of icy floors sounds fun—until all the characters are lying on their backs and the players are wishing they’d never entered the fight in the first place. Likewise, certain effects hurt some classes more than others. Disadvantage on attack rolls hurts martial combatants more than spellcasters. Limiting movement hurts melee attackers, while limiting visibility hurts ranged attackers. Be aware of when a zone-wide effect affects some characters more than others, so that you can change it up if needed. TRAPS AND HAZARDS Certain parts of a battlefield might contain traps or hazards. Some of these might be easily seen, such as 65 bladed pillars or spike-lined pits. Others might come as a surprise, such as a trap door over an acid pool. Characters with high passive Wisdom (Perception) scores might notice hidden traps automatically, or you might give each character a chance to make a Wisdom (Perception) check requiring no action—maybe even rolling on their behalf—to detect a trap before stumbling into it. Make sure these traps matter if you’re going to put them in an encounter. Traps that are too far out of the way might never come into play. Likewise, it can be fun for players to spring traps on their opponents, so don’t use them only as a threat against the characters. ADVANTAGEOUS POSITIONS Getting the characters to enter an arena (literal or metaphorical) and move around can be hard. Advantageous positions give them a reason to do so. Areas of high ground where they can gain cover against their foes—and perhaps advantage on attacks—are highly sought after by ranged attackers. Arcane circles that infuse a spellcaster’s magic with greater power might draw wizards into a room. This approach can turn a whole encounter into a fun game of “king of the hill” as the characters and their enemies fight for superior position. “Building Engaging Environments” on page 79 has more ideas on this topic. INTERACTIVE OBJECTS Make sure that the battlefield features some interactive objects. This can include any physical features the characters can manipulate and use to their advantage in a fight, including things like the following: • Crumbling statues that can be easily toppled • Pillars that collapse part of the ceiling • Chandeliers upon which to swing • Ballistas the characters can use to fire upon their foes • Obelisks infusing the villain with power until they’re destroyed • Levers that physically or magically transform parts of the battlefield • Catapults that can hurl allies to the far side of the fight • Cranes lifting heavy objects that can be dropped onto foes • Fiery cauldrons or braziers ready to tip over • Deep wells into which enemies can be dumped COVER Shattered pillars, crumbling statues, destroyed furniture, fallen trees, and other forms of cover can help break up the otherwise open terrain of a big battleground. When you drop in these elements of cover, be sure that the players understand the advantages of hiding behind them. For bonus points, tie the history of the location and other secrets and clues to these elements of cover. It’s not just a statue—it’s a statue of the forgotten god Gan, lost 66 in history and now seeking just one follower to pull their spark of divinity from the edges of infinite darkness. DIFFICULT OR FANTASTIC TERRAIN Different areas of a location might have some sort of terrain feature that can impact the fight. Difficult terrain is the easiest option, making it challenging but not impossible to take certain routes across the battlefield. But other areas of interesting terrain can also shake up a physical encounter. Icy floors where the characters might slip don’t work well as a zone-wide effect. But they can be great in specific areas, forcing the characters to avoid those areas as they move. Any of the following terrain features can make a big battle location more interesting: • A crumbling bridge over a deep crevasse • Spikes of sharp glass that cut creatures when they fall or are forced to move through them • Jets of flame that randomly erupt • Swampy land that belches forth poisonous gas when crossed • Oiled surfaces that cause creatures to slide across them uncontrollably. • Electrified floors that deal damage to creatures at the start of each turn • An area filled with antigravity magic that causes creatures to fall to the ceiling • An ethereal rift where creatures become invisible and insubstantial • Pockets of shadow where characters have their life energy drained away • An area of antilife magic where living creatures gain vulnerability to necrotic damage A GOAL Finally, think about what objective an encounter might have beyond simply taking out all the enemies. What might the characters do to “complete” the encounter? The following sorts of goals work well in a big set-piece encounter: • Stop a ritual before cultists summon a demon. • Recover an artifact and escape with it. • Kill the boss, but don’t worry about their minions. • Activate a gateway and escape through it. • Recover a prisoner. • Steal secret plans. • Destroy a powerful monument. • Activate the four altars around a temple site. • Close a magical gateway and prevent the villain’s escape. • Destroy a doomsday device before it blows up the multiverse. This topic is touched on in more detail in “Building Engaging Encounters” on page 76 and “Exit Strategies” on page 91. MONSTER COMBINATIONS FOR A HARD CHALLENGE When GMs design encounters, we often have a concept that includes the number of foes the characters will face. An encounter might feature a squad of four monsters going against the characters one-to-one, or perhaps a larger force of six or eight swarming the heroes. Or maybe we want a stronger creature, acting as a boss or captain, with only a few other creatures to back them up. And, of course, it’s always fun for characters to face a single dangerous foe. This section provides guidelines for combining creatures of different challenge ratings to enable these various concepts. Simply pick your concept, consult the appropriate table for the number of characters in your game, look up their average character level, and you have the monster challenge ratings you need to build different types of encounters and boss scenarios. You can then use the many other tips in this book to make encounters unique, including “Building and Running Boss Monsters” for any of the boss scenarios on the tables. HARD CHALLENGE LEVEL MONSTER COMBINATIONS JACK KAISER The challenge ratings in the tables are geared toward creating encounters that are a hard challenge (see “Defining Challenge Level” on page 105). The encounter concepts are set up along specific lines, reflecting some of the most common—and fun—combinations of foes. One Monster. The leftmost column notes the challenge rating expected for a solo creature whose statistics and capabilities can build a hard challenge. As discussed in “Building and Running Boss Monsters” (page 31) and “Understanding the Action Economy” (page 42), running an encounter for a single solo monster is always tricky. So use the advice in those sections to ensure that an intended solo creature is up to the challenge. Two, Four, Six, Eight, or Twelve Monsters. The other columns under Monsters of the Same CR allow you to challenge the characters with a number of creatures of the same CR, and usually of the same type. For example, a hard challenge for four 4th-level characters could constitute six scouts (CR 1/2) or two ogres (CR 2). Using creatures of the same type allows you to quickly and simply tell a story as the characters find themselves in an ogre market cavern, a caravan under attack, the room with mimics, and so forth. Using the same monsters also lets you focus on a single stat block for ease of play. One Boss + X Monsters. Encounter concepts often suggest a group of creatures led by a more formidable leader. Each of the Boss Scenarios columns pairs up one boss and a number of subordinates of lower challenge rating. For example, a group of four 3rd-level characters could face one boss of CR 2 and two subordinates of CR 1/2—perhaps an ogre explorer and the two rust monsters they’ve befriended. The rightmost column under Boss Scenarios builds encounters with eight minions, two lieutenants of a higher challenge rating, and one boss whose CR is higher again. USING THE TABLES To build encounters using the tables, follow these steps: • Select the appropriate table, based on the number of characters in the party—four, five, or six. • In the leftmost column of the selected table, find the row containing the average character level for all the characters. (To find the average, add up all the characters’ levels, then divide by the number of characters and round down.) • Follow that row to the column containing the encounter concept you wish to use. For example, to create an encounter with one boss and three lesser monsters, you’d go to the 1 Boss + 3 Monsters column. 67 FOUR CHARACTERS (HARD CHALLENGES) Monsters of the Same CR Character Level 1 2 4 6 8 1 1 1/2 1/8 1/8 0 2 3 1 1/2 1/4 3 4 2 1/2 1/2 4 5 2 1 5 8 4 6 9 7 10 8 Boss Scenarios 12 1 Boss + 2 Monsters 1 Boss + 3 Monsters 1 Boss + 4 Underlings 1 Boss + 2 Lieutenants + 8 Minions — 1/2 + 1/8 (x2) 1/2 + 1/8 (x3) 1/4 + 1/8 (x4) — 1/8 0 1 + 1/4 (x2) 1 + 1/4 (x3) 1 + 1/8 (x4) 1/2 + 1/4 (x2) + 0 (x8) 1/4 1/8 2 + 1/2 (x2) 2 + 1/4 (x3) 2 + 1/4 (x4) 1 + 1/4 (x2) + 0 (x8) 1/2 1/2 1/4 2 + 1 (x2) 2 + 1/2 (x3) 3 + 1/4 (x4) 2 + 1/4 (x2) + 0 (x8) 2 1 1 1/2 4 + 2 (x2) 4 + 1 (x3) 4 + 1 (x4) 3 + 1/2 (x2) + 1/4 (x8) 5 3 2 1 1/2 5 + 2 (x2) 4 + 2 (x3) 5 + 1 (x4) 4 + 1 (x2) + 1/4 (x8) 6 3 2 1 1/2 5 + 3 (x2) 5 + 2 (x3) 6 + 1 (x4) 4 + 1 (x2) + 1/2 (x8) 12 7 3 3 2 1 7 + 3 (x2) 5 + 3 (x3) 6 + 2 (x4) 4 + 2 (x2) + 1/2 (x8) 9 12 8 4 3 2 1 7 + 4 (x2) 6 + 3 (x3) 6 + 3 (x4) 5 + 2 (x2) + 1/2 (x8) 10 14 8 4 3 2 2 7 + 5 (x2) 6 + 4 (x3) 7 + 3 (x4) 5 + 2 (x2) + 1 (x8) 11 16 9 5 4 3 2 8 + 5 (x2) 6 + 5 (x3) 9 + 3 (x4) 6 + 3 (x2) + 1 (x8) 12 18 11 6 5 4 2 9 + 7 (x2) 8 + 5 (x3) 8 + 5 (x4) 7 + 4 (x2) + 1 (x8) 13 19 12 7 5 4 3 11 + 7 (x2) 10 + 6 (x3) 10 + 5 (x4) 8 + 4 (x2) + 2 (x8) 14 20 13 8 6 4 3 11 + 8 (x2) 10 + 7 (x3) 10 + 6 (x4) 8 + 5 (x2) + 2 (x8) 15 21 14 8 7 5 4 12 + 9 (x2) 10 + 8 (x3) 10 + 7 (x4) 9 + 5 (x2) + 2 (x8) 16 22 15 9 7 5 4 12 + 10 (x2) 11 + 8 (x3) 11 + 7 (x4) 10 + 6 (x2) + 3 (x8) 17 24 16 10 8 5 5 14 + 10 (x2) 11 + 9 (x3) 11 + 8 (x4) 12 + 6 (x2) + 3 (x8) 18 26 17 11 8 6 5 14 + 12 (x2) 12 + 10 (x3) 12 + 9 (x4) 13 + 7 (x2) + 4 (x8) 19 27 19 11 9 7 5 15 + 12 (x2) 14 + 10 (x3) 13 + 9 (x4) 13 + 8 (x2) + 4 (x8) 20 29 19 12 9 7 5 15 + 13 (x2) 14 + 11 (x3) 13 + 10 (x4) 14 + 8 (x2) + 5 (x8) • The entry you cross-referenced notes the challenge ratings of the creature or creatures in your encounter. If a multiplier is indicated, that’s the number of monsters for the preceding CR. For example, wanting to challenge four 3rd-level characters with the encounter concept of one boss and three monsters yields an entry of “2 + 1/4 (×3).” This indicates that you want one CR 2 creature acting as the boss, and three CR 1/4 creatures acting as subordinates. • Choose your monsters! If you’re building a quick encounter, the recommendations in “Monsters by Adventure Location” (page 72) are a good starting point. SCALING ENCOUNTERS Each of the tables is intended to build a hard encounter (see “Defining Challenge Level” on page 105). However, you can easily build encounters with other challenge levels in mind by adding or subtracting a modifier to the party’s average character level: • For a deadly challenge: +1 or +2 • For a medium challenge: −2 • For an easy challenge: −4 68 DON’T HANG ON TOO TIGHT It’s good to keep in mind that the guidelines in this section aren’t perfect for every group and every situation. Building combat encounters will always be an art, not a science. As such, the tables can give you a rough idea about what combination of monsters you might use in an encounter and what challenge rating might be appropriate for a hard challenge level. But so many variables can affect the outcome of an encounter—not the least of which is the incredibly random d20 roll—that no two battles ever run the same. Your own experience with your players and their characters almost always offers a better gauge of how any given combat scenario might play out. As such, always treat the advice in this section and the rest of Forge of Foes as loose guidelines, not fixed rules. For example, when building an encounter for four 10th-level characters, you could use the row for 8th-level characters to create a medium challenge. In all cases, be cautious with scaling. Encounters of certain types and at certain levels will be harder or easier than the approximation would indicate. Always be prepared to adjust encounters on the fly (with “Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27 providing great advice on this topic). FIVE CHARACTERS (HARD CHALLENGES) Monsters of the Same CR Character Level 1 2 4 6 8 1 1 1/2 1/4 1/8 0 2 4 1 1/2 1/4 3 5 2 1 1/2 4 6 3 1 5 9 5 6 11 7 12 8 Boss Scenarios 12 1 Boss + 2 Monsters 1 Boss + 3 Monsters 1 Boss + 4 Underlings 1 Boss + 2 Lieutenants + 8 Minions 0 1/2 + 1/4 (x2) 1/2 + 1/8 (x3) 1/4 + 1/8 (x4) — 1/8 0 1 + 1/2 (x2) 1 + 1/4 (x3) 1 + 1/8 (x4) 1/2 + 1/4 (x2) + 0 (x8) 1/2 1/4 2 + 1/2 (x2) 2 + 1/4 (x3) 2 + 1/4 (x4) 1 + 1/4 (x2) + 1/8 (x8) 1 1/2 1/4 3 + 1 (x2) 3 + 1/2 (x3) 3 + 1/2 (x4) 2 + 1/4 (x2) + 1/8 (x8) 2 2 1 1/2 5 + 2 (x2) 4 + 2 (x3) 5 + 1 (x4) 3 + 1 (x2) + 1/2 (x8) 6 3 2 1 1/2 6 + 3 (x2) 5 + 2 (x3) 6 + 2 (x4) 4 + 1 (x2) + 1/2 (x8) 7 4 3 1 1 7 + 3 (x2) 5 + 3 (x3) 6 + 2 (x4) 4 + 2 (x2) + 1 (x8) 13 8 4 3 2 1 7 + 4 (x2) 7 + 3 (x3) 6 + 3 (x4) 5 + 2 (x2) + 1 (x8) 9 14 8 5 3 2 1 8 + 4 (x2) 7 + 4 (x3) 7 + 3 (x4) 6 + 2 (x2) + 1 (x8) 10 15 9 5 4 3 2 8 + 5 (x2) 8 + 4 (x3) 8 + 4 (x4) 6 + 3 (x2) + 1 (x8) 11 17 11 6 5 4 2 10 + 6 (x2) 9 + 5 (x3) 8 + 5 (x4) 6 + 4 (x2) + 2 (x8) 12 19 12 7 6 4 3 11 + 7 (x2) 10 + 6 (x3) 9 + 5 (x4) 8 + 4 (x2) + 2 (x8) 13 20 13 8 7 5 3 11 + 8 (x2) 11 + 7 (x3) 10 + 6 (x4) 9 + 4 (x2) + 2 (x8) 14 22 14 9 7 5 4 11 + 9 (x2) 12 + 7 (x3) 10 + 7 (x4) 10 + 5 (x2) + 2 (x8) 15 22 15 9 7 5 4 12 + 10 (x2) 12 + 8 (x3) 12 + 7 (x4) 11 + 5 (x2) + 2 (x8) 16 24 16 10 8 6 4 12 + 11 (x2) 11 + 9 (x3) 11 + 8 (x4) 11 + 7 (x2) + 2 (x8) 17 25 17 11 9 7 5 15 + 11 (x2) 13 + 10 (x3) 14 + 8 (x4) 12 + 7 (x2) + 3 (x8) 18 27 18 11 9 7 5 15 + 12 (x2) 14 + 10 (x3) 13 + 9 (x4) 12 + 8 (x2) + 4 (x8) 19 28 20 12 10 8 6 15 + 13 (x2) 14 + 11 (x3) 13 + 10 (x4) 13 + 9 (x2) + 4 (x8) 20 29 20 13 10 8 6 16 + 14 (x2) 15 + 12 (x3) 14 + 11 (x4) 14 + 9 (x2) + 5 (x8) 12 1 Boss + 2 Monsters 1 Boss + 3 Monsters 1 Boss + 4 Underlings SIX CHARACTERS (HARD CHALLENGES) Monsters of the Same CR Boss Scenarios Character Level 1 2 4 6 8 1 Boss + 2 Lieutenants + 8 Minions 1 1 1 1/4 1/4 1/8 0 1 + 1/4 (x2) 1 + 1/4 (x3) 1 + 1/8 (x4) — 2 5 2 1/2 1/2 1/4 1/8 2 + 1/2 (x2) 2 + 1/4 (x3) 2 + 1/4 (x4) 1/2 + 1/4 (x2) + 1/8 (x8) 3 7 3 1 1 1/2 1/4 3 + 1 (x2) 3 + 1/2 (x3) 3 + 1/2 (x4) 1 + 1/2 (x2) + 1/4 (x8) 4 8 4 2 1 1/2 1/2 4 + 2 (x2) 4 + 1 (x3) 4 + 1/2 (x4) 2 + 1/2 (x2) + 1/4 (x8) 5 10 6 3 3 1 1 7 + 3 (x2) 7 + 2 (x3) 6 + 2 (x4) 3 + 1 (x2) + 1/2 (x8) 6 12 8 4 3 2 1 7 + 4 (x2) 6 + 4 (x3) 6 + 3 (x4) 3 + 2 (x2) + 1 (x8) 7 13 9 5 4 2 1 8 + 5 (x2) 7 + 5 (x3) 7 + 4 (x4) 5 + 2 (x2) + 1 (x8) 8 15 11 6 4 3 2 8 + 6 (x2) 8 + 5 (x3) 8 + 4 (x4) 6 + 3 (x2) + 1 (x8) 9 16 12 6 4 3 2 9 + 6 (x2) 8 + 6 (x3) 10 + 4 (x4) 6 + 4 (x2) + 1 (x8) 10 17 13 7 5 4 2 10 + 7 (x2) 9 + 6 (x3) 10 + 5 (x4) 7 + 4 (x2) + 1 (x8) 11 19 14 8 6 4 3 12 + 8 (x2) 11 + 7 (x3) 12 + 5 (x4) 8 + 4 (x2) + 2 (x8) 12 20 16 9 7 5 3 14 + 9 (x2) 13 + 8 (x3) 12 + 7 (x4) 9 + 5 (x2) + 2 (x8) 13 21 17 10 8 6 4 14 + 10 (x2) 13 + 9 (x3) 12 + 8 (x4) 10 + 6 (x2) + 2 (x8) 14 23 17 10 8 6 4 15 + 10 (x2) 15 + 8 (x3) 13 + 8 (x4) 9 + 7 (x2) + 2 (x8) 15 24 18 11 8 6 4 15 + 11 (x2) 15 + 9 (x3) 12 + 9 (x4) 9 + 7 (x2) + 3 (x8) 16 25 19 11 9 7 4 15 + 12 (x2) 15 + 10 (x3) 13 + 9 (x4) 11 + 7 (x2) + 3 (x8) 17 27 20 12 10 7 5 16 + 13 (x2) 16 + 11 (x3) 15 + 10 (x4) 11 + 7 (x2) + 4 (x8) 18 28 21 13 11 8 5 18 + 14 (x2) 17 + 12 (x3) 15 + 11 (x4) 12 + 8 (x2) + 4 (x8) 19 29 21 14 11 8 6 18 + 15 (x2) 16 + 13 (x3) 15 + 12 (x4) 13 + 9 (x2) + 4 (x8) 20 30 22 15 13 9 7 20 + 16 (x2) 18 + 14 (x3) 16 + 13 (x4) 13 + 10 (x2) + 5 (x8) 69 THE LAZY ENCOUNTER BENCHMARK Forge of Foes offers multiple ways to think about and plan combat encounters in your game. But this section sets out a simple calculation you can keep in your head to give you a gauge of the difficulty of an encounter. This “lazy encounter benchmark” isn’t perfect or precise. Rather, it’s a tool for getting a rough sense of the potential challenge of a combat encounter—and for recognizing when an encounter crosses over from challenging to potentially deadly. Think of it like a tachometer measuring how fast the engine is running in a car. If you go beyond the limit defined by the benchmark, you’re “in the red”—pushing to a point where your encounter might be more than the characters can handle. USING THE BENCHMARK The primary calculation of the lazy encounter benchmark compares the challenge ratings of monsters with the levels of the characters in the following way: An encounter might be deadly if the sum total of monster challenge ratings is greater than 1/4 of the sum total of character levels, for characters of 1st to 4th level; or greater than 1/2 of the sum total of character levels, for characters of 5th level or higher. What exactly does “deadly” mean in this context? “Defining Challenge Level” on page 105 explores this topic in detail, but it can be easily summarized. In a deadly encounter: • Most characters might lose more than half their hit points. • Several characters might go unconscious. • There’s a chance that one or more characters might die. For example, imagine an encounter pitting five 4thlevel characters against four ogres of CR 2. To see how dangerous this fight might be, add all the character levels together and divide by 4 (because they’re lower than 5th level), giving a result of 20 ÷ 4 = 5. Now compare that result to the sum of monster challenge ratings, with four CR 2 ogres giving a total of 8. Because 8 is more than 5, this could be a potentially deadly encounter. Above 4th level, you divide character levels by 2 instead of 4 because of the extra resources and synergies characters gain at 5th level and higher. Going back to the previous example, if the characters were 5th level instead of 4th, their total levels would be 25. The benchmark gives a result of 25 ÷ 2 = 12 (rounded down, as usual in the game). The four ogres still have a total CR of 8, and with 8 less than 12, these fifth-level characters aren’t likely to find this a deadly fight. 70 As another example, consider six 8th-level characters facing three CR 11 horned devils. Dividing the total character levels of 48 by 2 gives a result of 24. Adding up the challenge ratings of the horned devils gives you 33. So with 33 much higher than 24, that’s a potentially deadly fight. Still, even when a calculated benchmark suggests that an encounter might be too tough, that doesn’t mean you should automatically change things up. The lazy encounter benchmark is there to give you a warning sign that your encounter might be into the danger zone where it becomes more than the characters can handle. But your own experiences with the characters and players should ultimately tell you whether you should change things up or not. The lazy encounter benchmark intentionally doesn’t provide specific measurements for easy, medium, or hard encounters. Instead, think of it like an analog gauge. The lower the total monster challenge ratings are compared to the benchmark calculation from character levels, the easier the battle might be. The higher the total monster challenge ratings are above the benchmark, the deadlier the battle might be. OPTIONAL SCALING FOR HIGHER LEVELS As characters rise in level above 10th, their increased power and synergies mean that you might find the benchmark becomes less accurate about representing the potential deadliness of encounters. If this is the case in your games, you can scale up the benchmark equation for higher-level characters with the following variation: An encounter might be deadly if the sum total of monster challenge ratings is greater than 3/4 of the sum total of character levels, for characters of 11th to 16th level; or equal to the sum total of character levels, for characters of 17th level or higher. Explore this option only if it feels as though encounters assessed using the original benchmark are consistently underpowered for your group. But if you need it, this WRITE DOWN THE BENCHMARK RESULT Because the benchmark result only changes when the characters increase in level, you can write it down and keep it in your notes. If you’re going to have five 8th-level characters in your next several sessions, you can write down “Lazy Encounter Benchmark: 20” and reference that when throwing monsters together for an encounter. It’s especially useful to keep this number in front of you when improvising encounters during a session. option sets the benchmark for truly dangerous encounters at the highest levels, where characters of great heroic capability might face several powerful creatures in a single battle. THE CR CAP FOR A SINGLE MONSTER Although the lazy encounter benchmark uses the total challenge ratings of all monsters in an encounter, it doesn’t take into consideration the maximum challenge rating for any single monster, either alone or with a group. For that, you can use a different benchmark calculation to describe when a single monster of a particular challenge rating might represent a deadly challenge for characters of a given level, whether battled alone or in a group: A single monster might be deadly if their challenge rating is equal to or higher than the average level of the characters, or 1.5 times the average level of the characters if the characters are 5th level or higher. TUNING THE BENCHMARK Given the many different circumstances that can affect character power and encounter difficulty, you might want to tune the benchmark calculation up or down to serve as a more accurate guideline for your own group. To do so, simply increase or decrease the number of characters you use to calculate the sum total of character levels, treating that as a dial for tuning the benchmark for your own group. For example, if a party in your campaign has companion NPCs who make combat easier, or if characters employ spells that often remove monsters from combat, you can pretend the group consists of six characters instead of their actual five and calculate the benchmark that way. Likewise, if a group regularly gets into trouble in encounters where the sum total of monster CR is well below the benchmark, pretend the party has four characters instead of five. OTHER CONSIDERATIONS Many circumstances can change how challenging an actual combat encounter might be. All of the following examples set up types of encounters that often play out more easily than the lazy encounter benchmark might suggest: • The fight features significantly more characters than foes. • The characters’ goals in an encounter can be achieved without eliminating all the foes from the fight. • The environment favors the characters. • The monsters come in waves instead of all at once. • Foes are distracted or in disadvantageous positions. • The monsters are all surprised, or all act after the characters in initiative. ALTERNATIVE BENCHMARK An alternative approach to the lazy encounter benchmark lets you compare monster challenge ratings and character levels with a single straightforward formula, as follows: To assess the strength of the characters relative to the monsters they face, take the sum total of all character levels and divide by 4. Then multiply that number by the characters’ tier. At 1st tier (levels 1 to 4), the benchmark is simply the total of all character levels divided by 4. But as characters rise in level and across the tiers of play, they experience three distinct bumps in power at 5th level (the start of the second tier, multiplying the benchmark by 2), 11th level (the start of the third tier, for a ×3 multiplier), and 17th level (the start of the fourth tier, for a ×4 multiplier). In a broad sense, characters of the second tier can be thought of as effectively twice as powerful as characters of the first tier, with characters of the third and fourth tiers increasing in power yet again. However, as with the default versions of the benchmarks, it’s important to remember that increasing the multipliers for the third and fourth tier is optional, and should be done only if you find that encounters created with the ×2 multiplier aren’t keeping up to the characters. • The characters have spells or features well suited for taking out foes. • The players engage in excellent tactical behavior and synergistic strategies. • The characters are well rested and coming in fresh. • The characters have an arsenal of powerful magic items. • The characters have useful companions. Likewise, the monsters might be favored over the characters in the following types of encounters: • The monsters outnumber the characters. • The characters are surprised by the monsters. • Foes have advantageous position. • The terrain favors the foes. • The monsters fight with a strong tactical synergy. • The characters are coming in well worn by previous fights and have no chance to rest. As you make use of the benchmark, you’ll soon come to recognize when the circumstances of a combat encounter might steer it toward an easier or harder fight. 71 MONSTERS BY ADVENTURE LOCATION This section offers quick starting points for building encounters, in the form of tables that cover a broad range of foes in twelve types of common adventure location. The tables serve four purposes: • They show which creatures might inhabit a particular adventure location. • They highlight foes appropriate for a given level range in that location. • They show which foes might naturally pair up with other foes. • They offer example relationships between creatures and suggest what they might be doing in a location. Though you can use the setups in the tables directly, you’ll get even more value from them by customizing your own list of foes for these common locations and scenarios—or by adding environments and scenarios that fit the specifics of your campaign. “Choosing Monsters Based on the Story” (page 113) and “Building Engaging Environments” (page 79) both offer thoughts on determining which creatures make sense for a situation or location. Each line in the “Example Encounters” column contains an example encounter with multiple monsters. You can decide how many monsters are appropriate given the scenario, the number of characters, and their level. Monsters who are in bold represent potential bosses for an encounter. ANCIENT RUINS Level 72 Example Encounters 1st • A thug leads bandits intending to rob a caravan. • A vengeful shadow shifts in the darkness among a handful of arisen skeletons. 2nd to 4th • A pair of bugbear entrepreneurs use goblin actors as bait to seek adventurers as prey. • A sorrowful banshee orders specters to recreate their former beautiful life. • A gnoll pack lord bounty hunter leads gnolls and hyenas after an escaped prisoner. • A death dog protected by wolves lairs in a ruined cave. • A lamia served by jackalweres dwells in an illusory paradise. 5th to 10th • A wise bugbear chief leads bugbear and goblin soldiers from an obsidian throne. • A cyclops matriarch leads fanatically loyal ogres. • A solitary medusa dwells in a mausoleum, surrounded by petrified heroes and protected by death dogs. • A noble oni in a posh den is guarded by loyal spirit naga storytellers. 11th to 16th • An adult blue dragon is guarded by clay golems in a jeweled lair. 17th to 20th • An ancient blue dragon protected by stone golems and air elementals dwells in the shattered remains of a tower. CRYPTS, CATACOMBS, NECROPOLISES Level 1st Example Encounters • A pair of skeletons rises from a pile of crawling claws. 2nd to 4th • A lost ghost wanders, surrounded by specters. • A bone naga rises from an obsidian sarcophagus to command a host of skeletons. 5th to 10th • A mummy lord entombed in a cold-iron sarcophagus is guarded by mummies and wights. • A pair of wraiths float above unholy urns surrounded by vengeful specters. 11th to 16th • A vampire in a gilded tomb is guarded by howling dire wolves and served by vampire spawn. 17th to 20th • A lich in an unhallowed laboratory is protected by loyal death knights and iron golems. CITY SEWERS Level 1st 2nd to 4th Example Encounters • A wandering zombie is covered by a swarm of rats. • An erudite ghast weaves fantastic tales to their ravenous ghoul followers. • A spy is guarded by unscrupulous bandits while awaiting the arrival of a contact. • An otyugh luxuriates in a watery pit, surrounded by concealed gray oozes. • Wererats try to be intimidating by threatening to feed prisoners to their giant rat pets. SEEDY CITY STREETS Level Example Encounters 1st • A giant rat and the swarm of rats that travels with them are feeding on a dead body. • A thug and a pack of bandit toadies are waiting for someone to rob. 2nd to 4th • A spy assisted by thugs has been hired to steal something from the characters. • A bandit captain with berserker bodyguards and bandit followers is easily insulted. • A cult fanatic leads cultists who have summoned ravenous dretches into the world. 5th to 10th • A mage commanding veterans is seeking something the characters seek as well. • A bandit captain protected by hired gladiators and veterans seeks the characters with an offer they can’t refuse. • A careful assassin backed up by spies and thugs hunts the characters. WIZARD’S TOWER Level 1st Example Encounters • A loyal imp commands a squad of guardian flying swords. HELLISH CITADEL Level Example Encounters 2nd to 4th • A bearded devil draws lemures through a portal connected to the river Styx. • A barbed devil and a host of imps keep watch on enemy forces. 2nd to 4th • A summoned succubus or incubus directs animated armor serving as guards. 5th to 10th • Apprentice mages command elementals and flesh golems. • An important chamber is guarded by two flameskulls and a number of helmed horrors. 5th to 10th • An armored erinyes commanding a host of spined devils prepares for war. • A horned devil leading bearded devil soldiers guards an oracular sphere. 11th to 16th • An impatient archmage is protected by two stone golems in an arcane laboratory. 11th to 16th • Ice devil wardens and bone devil guards protect a valuable prisoner. 17th to 20th • A lich studies the multiverse while protected by bound balors and iron golems. 17th to 20th • Pit fiend commanders and horned devil lieutenants use scrying crystals to get the drop on the characters. VOLCANO LAIR Level Example Encounters 5th to 10th • A fire giant with pet hell hounds commands an azer to dig for them. • A trapped efreeti uses fire elementals to fight for freedom. 11th to 16th 17th to 20th FROZEN FORTRESS Level 5th to 10th • An adult red dragon served by salamanders demands fealty from the characters. • Frost giant hunters enjoy the sport of their remorhaz pet stalking commoners. • The bone-cluttered cave of an abominable yeti is guarded by winter wolves. 11th to 16th • An ancient red dragon worshiped by fire giants awakens from slumber. • An adult white dragon is served by loyal frost giants. 17th to 20th • An ancient white dragon lairing atop an inaccessible peak is worshiped by generations of abominable yetis. ABYSSAL KEEP Level 2nd to 4th Example Encounters • A night hag and their pet quasit schemes within a chamber guarded by hell hounds. • A summoning circle disgorges a barlgura and a gang of dretches. 5th to 10th • A glabrezu commands from a throne flanked by chasmes. 11th to 16th • A marilith, their cambion advisor, and a number of hezrou servants guard a planar gateway. 17th to 20th • A balor, a servile archmage, and a squad of glabrezu soldiers guard an artifact. DEEP CAVERNS Level 1st 1st 2nd to 4th 5th to 10th • Basilisks and cockatrices lair in a hall full of petrified adventurers. • A cloaker lurks above a pack of hook horrors disemboweling a dead bulette. • Ropers and darkmantles hang above a waterfall, competing for prey. • An elf cultist hunts prey with bloodthirsty wolves. 5th to 10th • An orc war chief commands a force of ettin and orc scouts based in a ruined keep. 11th to 16th • An adult black dragon commands a host of trolls made loyal through fear. • An adult green dragon lurks in a dead forest, protected by shambling mounds. 17th to 20th • An ancient black dragon dwells in a sunken bog filled with giant crocodiles. • An ancient green dragon rules from an ancient wooden throne guarded by loyal treants. • A cockatrice pecks at a crumbling statue, while stirges linger above. • A giant bat surrounded by swarms of bats skulks in the shadows. • Darkmantles and piercers lurk in pools of shadow. • A worg-riding goblin boss commands a squad of goblin hunters. Example Encounters • Two ettercaps and their giant spiders stalk adventurers. • An ettin warlord commands a host of orc mercenaries. • A green hag lurks in an old hut with a pet giant toad, and is guarded by loyal bullywugs. • A werewolf prowls the shadows with their dire wolf companions. Example Encounters 2nd to 4th DARK FORESTS AND FETID SWAMPS Level Example Encounters SUNKEN GROTTO Level Example Encounters 1st • A lizardfolk hunter is teaching their trained giant crabs how to hunt. 2nd to 4th • A sea hag commands loyal kuo-toa to set up an effigy to a fictitious god. • A lizard king with a lizardfolk shaman advisor commands a clan of lizardfolk from a coral throne. 5th to 10th • An aboleth in a swirling pool is guarded by chuuls and worshiped by enthralled veterans. • A sahuagin baron watches a pack of sahuagin fight water weirds. • A corrupt sahuagin priestess feeds sacrificial victims to giant crocodiles. 11th to 16th • A kraken rules a deep-sea trench, surrounded by reverent water elementals. 73 MONSTERS AND THE TIERS OF PLAY How combat plays out against specific types of monsters in D&D and other 5e games changes depending on the level of the characters. Character power progression isn’t smooth and linear across levels. Rather, it spikes at particular levels, potentially changing the outcome of a battle dramatically. As an example, the jump from 4th to 5th level gives melee characters twice as many attacks, while spellcasters gain access to spells such as fireball, significantly raising a party’s damage output overnight. Recognizing when and how these changes take place can help GMs understand and prepare for these shifts in game play. 1ST LEVEL 2ND THROUGH 4TH LEVEL 74 At 2nd through 4th level, encounters most often play out as expected for a heroic fantasy roleplaying game. Characters are robust enough to face a range of monsters and not get killed. Most characters have a single attack, or sometimes two if they fight with a weapon in each hand. Spells usually target one or two creatures. Combat encounters of 2nd to 4th level are often the easiest to balance compared to other levels of play. Characters of 2nd through 4th level can typically handle a group of monsters from challenge rating 1/8 to CR 1, a pair of monsters of CR 2 or 3, or a single monster up to about CR 5. Great foes at these levels include all of those appropriate for 1st-level characters, along with ogres, scouts, dire wolves, and veterans. Cult fanatics, hags, vampire spawn, ettins, and lamias can work well for bosses at this tier. 5TH TO 10TH LEVEL At 5th level, character power spikes up. Fighters can attack twice, and can double that double attack with Action Surge. Spellcasters gain access to spells such as fireball, spirit guardians, and hypnotic pattern. As characters rise above 5th level, their capabilities increase quickly. Monks get Stunning Strike. Spellcasters learn spells able to take out a foe with a single failed saving throw, including banishment and polymorph. At 5th level and above, you can no longer trust a lone nonlegendary monster to challenge a group of characters. Often a single spell, class feature, or volley of attacks can incapacitate or kill any such creature. Against large groups of foes, a casting of fireball or a use of Turn Undead can end the fight. Get comfortable with this change to how your encounters are going to play out, and use lightning rod monsters (page 44) to let the characters show off these potent capabilities without ruining your fun. At these levels, the heroes’ defensive capabilities increase as well. Characters can fly, turn invisible, or block off entire sections of the battlefield with spells like wall of fire. Healing becomes plentiful. Paladins can protect entire parties with their defensive features. Even lower- FABIAN PARENTE Though not identified as its own tier of play in the fifth edition core rules, games at 1st level are entirely different from games at later levels. Characters of 1st level have few resources—hit points in particular. Creatures of CR 1/2 can kill 1st-level characters with a single critical hit, and 1st-level spellcasters have few spells able to control more than one or two monsters. When designing combat encounters at 1st level, be wary of using foes higher than CR 1/4, and lean toward running fewer monsters than characters. A CR 1/2 creature might make a decent boss monster for 1st-level characters, but a CR 1 monster might knock characters unconscious with a single hit—or even kill them completely. Even when running a published adventure for 1st-level characters, take note of the encounters it offers. Many such adventures include potentially deadly encounters at 1st level, so adjust them accordingly by running lower-CR monsters and fewer of them. Creatures of CR 1/8 to CR 1/2 work well for 1st-level characters, including bandits, cultists, and skeletons, with maybe a thug for a boss. (The “Running-1st Level Adventures” sidebar in this section offers more thoughts on this topic.) level defensive features such as the shield spell can be used more often with a larger number of available spell slots. At 5th level and above, a GM’s understanding of the capabilities of the characters and how those capabilities relate to a monster’s stat block is vital to building challenging encounters. (See “Reading the Monster Stat Block,” page 102, for more on this topic.) Creatures who challenge characters at 5th level and above (roughly CR 4 and up) are usually more complicated than those of lower challenge ratings. Hard encounters put together using default encounter-building rules might be less challenging than expected. Characters of 5th to 10th level can often take on hordes of foes of CR 1/4 to CR 1. They can usually survive battles against groups of CR 2 to CR 5 monsters, small groups of CR 6 to CR 10 foes, and single monsters up to CR 15. Great foes at this tier include young dragons, giants, mages, and lower-CR demons and devils. Bosses can include medusas, lower-CR adult dragons, mid-CR demons and devils, and maybe even an archmage. 11TH TO 16TH LEVEL At 11th level, characters become superheroes. They have huge amounts of resources at their disposal to handle the hardest monsters in the game. The heroes’ ability to control or incapacitate foes continues to increase, along with their ability to dish out tremendous amounts of damage. The variance in power and capabilities between different groups at these levels of play is wide. Challenging battles can take significantly longer to run than those of lower levels. Monsters who feel like a good challenge often end up easier to defeat than expected, and characters at this level can often take out a single powerful boss with ease. Likewise, the characters have numerous options to mitigate the damage their foes deal—made worse by the fact that many published monsters appropriate for these levels deal too little damage for their challenge rating. (See “The Relative Weakness of High-CR Monsters,” page 53, for more on that topic.) Characters at these levels can often take on large groups of monsters of up to CR 3, medium-sized groups of CR 6 to CR 10, small groups of CR 11 to CR 14, and single opponents of up to CR 21. Good foes at this tier include all of those mentioned previously, along with ancient dragons, higher-CR giants, liches, and high-CR demons and devils. And even at a high CR, a boss monster almost certainly wants some friends to defend against the characters. 17TH TO 20TH LEVEL From 17th level up, the characters are just short of godlike. They travel across worlds. They can often easily defeat any single monster of any challenge rating, unless the GM customizes that monster to face them. Characters at the highest levels have the strongest defenses imaginable, letting them absorb tremendous amounts of damage and wave off most detrimental effects. RUNNING 1ST-LEVEL ADVENTURES At 1st level, 5e isn’t just effectively its own tier—it almost feels like its own game. Play at 1st level feels different than at just about any other level. Characters have far fewer resources at their disposal—including tactical options and hit points—even as 1st-level campaigns often feature less-experienced players. Many groups love this style of play, often seen in D&D-inspired games that identify as part of the Old School Renaissance, hearkening back to a time when characters were at greater risk of death, and players had to trust to their wits rather than their characters’ die rolls and class features to overcome challenges. As a GM running a 1st-level 5e game, you have some choices about how you want to handle this very different play style. First, you can get through that level quickly. Mike often quips that 1st level should be a crucial conversation and a fight against a giant rat. Then boom, the characters are 2nd level and can begin their adventuring careers in earnest. This takes the game past its initial potentially deadly stage, and into the heroic-fantasy style of play faster. At 2nd level, character hit points go way up in relation to the damage their foes can deal, and new class features unlock to give characters more agency in situations that might have crushed their 1st-level selves. Alternatively, you can design adventures specifically for this level of play. The guidance in this section can help you think about which monsters of specific challenge levels work best to not wipe out 1st-level characters. Or you might decide to have the stripling adventurers focus more on challenges in the world than combat encounters. Create opportunities for the characters to sneak around, so that maybe they drop a big pile of logs on those pesky bandits instead of facing them head on. Your 1st-level games can also focus on roleplaying, letting the characters engage with important NPCs before heading off on more dangerous missions. Alternatively, you can embrace those earlier days of fantasy roleplaying where death was around every corner. Many people love 1st-level 5e games for this very reason. Two Shortbow attacks from a skeleton can put an average character in the dirt, and a critical hit from an ogre can turn even the toughest fighter or barbarian into a red splotch on the wall. Whichever approach you choose, discuss the style of the game you plan to run with your players ahead of time. Find out if they want that grim and dangerous 1st-level adventure, or if they’d prefer to have their stern conversation and giant-rat fight before their real heroic journey begins. To build challenging encounters at these levels, GMs must customize those encounters around the powers and capabilities of the characters, and such battles can take a long time to run. (“Building Challenging High-Level Encounters,” page 86, has information and advice on these sorts of encounters.) At these levels, characters can take on huge numbers of foes below CR 5, large groups of CR 6 to CR 10, mediumsized groups of CR 11 to CR 15, and bosses of CR 22 and above. Characters at these levels can fight—and triumph over—any monster in 5e, even when partnered with other monsters. 75 BUILDING ENGAGING ENCOUNTERS An engaging encounter is one that makes the players take notice. They lean forward in their seats. They talk to each other excitedly. They come up with plans, interact with scene elements, and stay focused as the scene develops. But how do we achieve this? This section looks at the types of elements in an encounter that can serve as sources for engagement. It then discusses the types of engagement we can tie to those elements, evoking in the players a desire to take action. engaging. An encounter with the zealots who attacked the caravan from a previous scene? Much more engaging. WHAT DOESN’T ENGAGE? Encounter features that can be manipulated catch the eye of players and characters alike. The more the interaction feels rewarding, necessary, or interesting, the greater the engagement. A rewarding feature is one that provides a benefit in combat. A statue might look obviously unstable as it looms over a foe—inviting the characters to topple it onto that foe. An enemy spellcaster lobs spells from a raised platform, but a block-and-tackle can allow a character to reach the top of the platform. Archers fire on the party from an unreachable position, but furnishings can be Many aspects of a fantasy roleplaying game are fun but not necessarily engaging. This is especially true of the many repetitive elements of the game. A spellcaster attacks with their cantrip. A rogue hides. The dwarf fighter attacks with her battleaxe. Players can do these things, have fun, and be disconnected from play at the same time. A player might roll their dice, then go back to their phone. Similarly, an encounter element can fail to engage. A trap fires an arrow, but the players smartly conclude that it isn’t a priority and agree to ignore it for a time. That’s fine if the role of the trap was solely to add a bit more damage. But it’s lackluster if the trap was supposed to engage the players. Likewise, a GM might imagine an encounter with a pack of gnoll reavers as fearsome, but can clearly see that the players aren’t on the edge of their seats. Monster concepts, and even monsters with fun stat blocks, are sometimes not enough engagement on their own. FOES Certain monsters and types of monsters can provide engagement in their own right. They might have surprising features, story importance, interesting roleplaying potential, or other compelling aspects. ACTIONABLE FEATURES ENCOUNTER ELEMENTS PROVIDING ENGAGEMENT To create an encounter to which the characters can fully respond, it’s good to break the encounter down initially into its component parts. Think about which elements can fit your encounter concept—but be aware that you don’t want to overwhelm the encounter with too many engaging elements. Rather, look for the specific elements that match the feel of the encounter best. ENCOUNTER PREMISE 76 DANNY PAVLOV The premise of an encounter dictates from the start how significant it is for the players. An encounter with goblin religious zealots might or might not be turned on their sides to provide cover. The clearer the payoff of a feature, the more likely the engagement. Necessary features are ones that the characters immediately understand they must make use of during an encounter. For example, planks next to a ravine must be turned into a bridge to get to the other side to reach enemies. Magic pillars must be interacted with to bring down a force field protecting a spellcaster. A vial of liquid labeled “Sleep Potion” appears near a huge monstrosity who appears impervious to spells and weapons. Interesting features are those that are as much fun for the players to figure out as for the characters—or sometimes even more so. If an angry beast is held in a cage and the key is in the lock, it isn’t clear whether letting the beast loose will help the party—but it sure is interesting! A lever on a wall bears a sign saying: “Pull when in danger.” An unlabeled potion sits on a table halfway between the foes and the characters, and the foes appear intent on seizing it first. LOCATION AND TERRAIN The location of an encounter can easily drive engagement. A battle across a ravine filled with molten lava tends to wake the players up. A choice between using a swaying rope bridge to cross a ravine or taking a longer but safer path around it forces a decision. BENEFITS AND TREASURE a battle on the edge of a ravine filled with molten lava can take on story relevance when a character spots an important item they need sitting perilously close to the edge of the ravine. Story relevance can be an important add-on to random encounters, even beyond what such encounters can tell the characters and players about the world. Players pay attention when a random encounter features a direct connection to the villain they’ve been chasing, a clue they need to obtain, or an NPC they care about who is in peril. PERSONAL OR GROUP GOALS An encounter has greater engagement when it ties to goals the players and their characters care about. A player might have set up a character backstory to which an encounter element can be tied. A long-lost journal, information about a missing sibling, or a clue to the location of a treasure they once lost can all engage individual characters. The characters might also have goals as a group. Needing to earn the trust of a city’s rulers might be necessary to gain permission to build a keep in the area. So if the characters happen upon a spy who just murdered one of those rulers, the stakes are that much more engaging. AN ADVANTAGE OR OPPORTUNITY The presence of an obvious benefit engages players. To reach the golden chest, the foes must first be defeated. A noble shouts a promise of a reward if the characters save them from an imminent threat. A foe fights with a glowing longsword that promises unusual power to the character who claims it. Encounters can provide clear boons the characters can utilize or turn to their advantage. A barrel of lamp oil is discovered, one room away from an enormous troll. A chandelier has a rope tied to it, ready for someone to swing across the area. A cavern features only sleeping foes, who stay that way if the characters can cross the debris-strewn floor without making noise. TYPES OF ENGAGEMENT THE UNEXPECTED As you consider sources of engagement for your encounters, also consider what types of engagement those encounter elements can provide. STORY RELEVANCE Story relevance ties one or more encounter elements to the arc of the adventure or the campaign. This relevance is often tied to the encounter premise, but it can link to other encounter elements as well. During a battle with ruffians in a city, a character notes a foe’s tattoo—a symbol associated with the secretive cult the party has been trying to find. Suddenly, the foe has story relevance. Similarly, START STRONG Especially for experienced players with a wide knowledge of what standard monsters can do, Scott likes to have monsters who play against type or immediately show off unusual traits or abilities. This strong start can dial up the engagement in a hurry. An encounter can grab everyone’s attention when an encounter element is surprising or unusual—especially the encounter premise. Approaching a guardroom, the characters hear goblin and human guards having a heated argument that threatens a fight. In response, the players can discuss how to use the conflict to their advantage as they try to sneak past—or to goad the two sides into fighting each other. Surprises can also be revealed during an encounter. A young kraken might molt, shedding their skin and becoming larger and more capable as you add several new features to their stat block. Or an earthquake might strike underground, threatening to throw all the characters into a lava-filled ravine. In a dungeon, a foe pulls a lever and a wall begins to drop, closing off access to the treasure in 2 rounds unless the characters can reach it or stop the wall’s descent. Foes can also provide surprises by revealing information as they fight. What does the paladin do when an assassin says she’s tired of serving evil and offers to follow them? 77 FORESHADOWING VILLAINS Mike likes to let characters hear tales of particular villains ahead of time. The characters might encounter a captive, who tells of the fearsome gnoll captain Argvon the Black Foot. When the characters later encounter a fearsome gnoll with one black foot, they excitedly anticipate a challenge! MYSTERIOUS OR INTRIGUING A mysterious encounter element is a promise that something will be revealed during the encounter, often in exchange for interaction and engagement. When a skeleton on the ground has an arm stretched toward one of three levers sticking out of the wall, the characters and players can discuss what this means. They can seek out clues to tell them more, and hopefully learn enough to make the exercise feel rewarding. When facing creatures made of shadow, interacting with a glowing source of light in the center of the room is likely to interest the characters. Likewise, when fighting an invisible foe in a chamber full of looking glasses and spectacles, the characters should be quick to suspect that interacting with those objects might let them discover a way to reveal that foe. TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE Characters and players can have fun interacting with a situation that feels like an obvious setup. The players might second-guess themselves and trigger the setup anyway, or they might find clever ways to turn the situation against others. For example, a dungeon doorway leads into an open-air garden, the warm sun visible overhead. That can’t be possible, and the characters know it. Or an enemy on the far side of a room might flip a lever that activates a trap. Another lever near the characters has an inscription on the wall above it that reads, “Turn Off Trap”—but the characters might suspect that pulling that second lever will only make the trap worse. IMPENDING DOOM An obvious problem that gets worse over time creates pressure and begs for action. An hourglass secured to a wall rotates, the sand slowly running out—but what must the characters do in response? A shadowy form pushes against a membrane, threatening to break through at any moment. A gang of kobold inventors are assembling a huge trap or weapon, and will be able to use it against the heroes in just a few rounds. Such clear signs of impending doom provide a clarion call to action. FORESHADOWING When the characters have heard of a particular monster or dungeon feature ahead of time, finally reaching that foreshadowed element makes a big impression. A torn journal in a dungeon corridor might record the account 78 of other adventurers who barely survived “the deadly scythe room.” Several rooms later, the characters find a chamber filled with swinging scythes, making that encounter feel more engaging and less random because of the earlier warning. PROVOCATION OR CHALLENGE A villain appears in court and whispers a challenge, daring the characters to strike them down. An ogre bellows that no foe has ever forced her to yield. A band of goblins wear shirts saying “Unbeatable Goblin Fight Club.” Such provocations demand responses from the characters, and make a scene more memorable. HOW MUCH IS TOO MUCH? An encounter with no engagement can be boring. An encounter with too much engagement can be overwhelming. When thinking about encounter elements that can create engagement, try to think through the perspective of the players when their characters first enter the encounter. How much information is presented initially? How much additional information is presented as the encounter progresses? Is needing to process that information likely to help the characters during the encounter? Or will it cause the players to become disengaged because they can’t keep track of everything going on around the party? As a rule of thumb, select no more than two or three types of engagement for an encounter, and apply them sparingly. One goblin warlord issuing a challenge can create a memorable scene. But that scene loses engagement if the characters are already trying to swing on a chandelier, disarm a trap, and save a beloved NPC. Similarly, if every goblin in the war band issues a challenge to different characters, the engagement becomes repetitive and harder to track. Less is more! Engagement can also be overwhelming for you as a GM. When GMs have to track too many variables, it can become harder to also look after all the other parts of the game, including roleplaying the foes, remembering character backstory, and running monsters tactically. Using whatever level of engagement you’re able to run most effectively will help make that engagement fun for you too. As you create encounters and try out different methods for increasing engagement, also keep an eye on what works for your group. Some players like a simpler game, while others will embrace complexity and enjoy trying to track all the things they can do in an encounter. Over time, you can modify your approach to find the best common-ground fit between your preferred style and that of your players. BUILDING ENGAGING ENVIRONMENTS Engaging environments are ones in which the terrain, features, layout, and other elements excite players and characters alike. In this section, we take a look at the locations we choose for our battles, and the art of encouraging the characters to interact with the environment. REINFORCING STORY When designing an encounter, consider the natural habitat of the foes in that encounter. The right environment can reinforce the theme of the encounter and enhance the story by creating a more realistic and engrossing setting. For example, in an encounter with several giant apes, it’s almost mandatory for the encounter area to include trees and vines from which the apes can swing down and attack. Such an environment provides engagement as the characters deal with the apes’ ability to climb out of reach and move from branch to branch. Even if an expected or ideal environment isn’t available, you can play off the baseline concept. Giant apes in a canyon could climb rocky pillars and navigate narrow rock ledges, providing the same advantages and attack options outside of a forest environment, and helping the story resonate with and engage the players. However, when selecting an environment, make sure that what fits the story doesn’t hinder the fun. An encounter with giant frogs in pools or a swamp makes great sense. But if the pools are so deep that the characters can’t easily approach the frogs, the encounter could become frustrating. Adding giant lily pads increases engagement and reduces frustration, while still presenting the thematically appropriate challenge. TACTICAL ENGAGEMENT An environment that provides a tactical advantage almost always creates engagement. This can be true regardless of whether the environment favors the foes, the characters, or both. When providing a tactical advantage, think of the benefit and how it might be countered, as with the examples below. (You can find additional ideas for engagement in “Building Engaging Encounters” on page 76.) FORMATION What the characters see when an encounter starts informs how they approach the encounter. If ten kobolds are in the center of a room, the characters might opt to initially engage with area spells and effects. Melee characters lacking those options will rush forward, engaging the closest foes. But if five of the kobolds are in the center of the room and five are farther back using bows, the tactics change. Area spells are still useful, but the characters might want to divide their tactics, with some going after the kobold archers. Likewise, spreading all ten kobolds around the room, perhaps in groups of two, forces the characters to split up. This could leave them open for a surprise the kobolds have planned, such as getting ready to use nets or standing on the far side of concealed pit traps. For all these options, needing to decide what to do can engage the players, encouraging them to develop strategies and communicate with each other. MOVEMENT An excellent skill to develop as a GM is understanding how an encounter drives, facilitates, or impedes movement. Consider an encounter with interesting features, but in which the monsters quickly run up to the characters and the fight ends up centered on the doorway into the area. To avoid this, consider the width of the entrance and the distances between the door, the foes, and the engaging aspects of the environment. Moving foes back from the entrance allows characters to get fully inside an encounter area. In many cases, it can be advantageous to start an encounter without obvious foes, making it more likely that the characters will enter the area—after which combat can begin. Gargoyles might wait until characters start to explore the interior of an old temple before revealing themselves. A group of gnoll sentries can enter a great hall from another door once the characters reach the center of that area. Once an encounter is underway, provide incentives to entice characters to move. An engaging environment can help, but think through all the lines of travel that exist in an area. Are there bottlenecks where fights will impede movement? Are there enough ways to reach key areas of the encounter? How many 30-foot moves are required to reach those key areas? You don’t necessarily want to remove all elements that impede the characters, but providing ways to speed up travel or bypass bottlenecks can encourage movement. Forced movement can also provide good engagement. A monster who can use telekinesis, grasping tentacles, or some other means of dragging characters closer to desired locations (including closer to themself) ensures that the characters will interact with the environment, whether as STACK THE DECK Scott notes that GMs can easily entice players to take a particular course of action by giving their characters a tangible benefit if they do so. Characters might not be inclined to take the time to navigate stairs to reach a boss monster—unless the stairs also provide half cover against attacks from the boss’s minions, creating an environmental benefit that makes that route a more attractive option. 79 UNREALISTIC SIZES ARE OKAY Scott points out that the goals of facilitating roles and enabling movement often require larger encounter areas than would be found in real life—and that this is fine. A 30-by-30-foot chamber is large in our world, but might work perfectly with the backstory of a fantastic location to allow for monsters and characters to interact properly. Similarly, Teos points out that a 5-foot-wide corridor works just fine for real people walking, but can be too narrow for the combat-focused reality of the game. This is because moving through a space containing an ally requires twice the movement. As such, a 5-foot corridor can hinder any attempts for characters or monsters to reposition or move tactically, and should generally not be used anywhere that combat might take place. a result of forced movement or of trying to stay out of the reach of a creature who can move them. FACILITATE ROLES Even though monsters in 5e games don’t have defined roles (controller, defender, and so forth), you can always think about the effect a monster’s stats have on the role it plays in combat, then use the environment to facilitate that role. A monster with high hit points or Armor Class should go to the front, drawing the heroes’ attention and soaking up the damage that would otherwise reach more important monsters. A choke point forces heroes to work through these combat-focused foes first. Monsters who deal high damage, especially those with high mobility, can engage key heroes in the middle or rear party ranks and then move away to safety. The environment facilitates this approach to monster roles when it provides ways for monsters to reach their intended targets. Likewise, monsters who hide should be given cover so they can maximize their potential for ambush. And monsters who can boost allies or attack at a distance should be given enough space to do so while maneuvering to stay away from the characters. (For a look at how to more formally apply monster roles to your game, see “Monster Roles” on page 22. “Reskinning Monsters” on page 50 also makes use of monster roles.) ELEVATION AND COVER 80 Even easily defeated foes such as kobolds and goblins become harder to take on if some of them are placed on higher ground and behind cover. Similarly, providing characters with the benefits of elevation or cover can allow them to take on stronger foes or additional waves of weak foes. When adding elevation, consider how one or both sides can use it, and how creatures can reach elevated areas. Stairs or other means of access that are difficult terrain might require several rounds of movement. Many players would rather have their characters stay below and make inefficient ranged attacks than spend 2 or more rounds to reach their foes. But there are also times when placing foes out of reach works well, as doing so can let ranged and spellcasting heroes shine. If melee characters are expected to try to reach the high ground, set up ways for them to do so in 1 round, and don’t create a scenario where they spend most of the combat running from foe to foe. Even risky ways to move, such as making an ability check to ascend to a warehouse balcony using a pulley, work better than spending successive rounds on movement. Both elevation and cover are excellent ways to boost survivability. Because spellcasting foes often have fewer hit points and can be easily pinned down in open terrain, allowing spellcasting foes to begin combat hidden behind cover causes characters to focus on other targets initially. Once the spellcaster takes their actions, the heroes can change tactics to respond to the newly revealed threat. And whereas needing to spend 2 rounds to reach a goblin is usually frustrating, spending 2 rounds to reach a dangerous spellcaster might be a worthwhile option for a melee hero. Cover is also a boon to any foes or characters who benefit from stealth. A rogue always appreciates environments allowing them to hide, just as foes who work best as lurkers or skirmishers can benefit from cover and being able to fall back to hard-to-reach places. ENGAGING ELEMENTS Specific elements in the environment can help engage the players during an encounter, especially when the source of engagement gives the characters an edge. When designing encounters, look for opportunities to add dynamic elements that fit the location and reward interaction. DAMAGING OR HINDERING TERRAIN In a forest frequented by fey creatures, the vegetation might grab at characters, slowing or restraining them. A fight atop a volcano might feature pools of glowing magma that damage any creature moving through them. When selecting such terrain, consider where to place it in an encounter. Think through the likely routes creatures will take during combat, and how to create or break up obvious movement patterns to generate options or force particular behavior. Pools of lava might force melee characters to spend time reaching foes, or might encourage them to focus on high-AC foes in front of them, helping to protect vulnerable foes farther away. When hindering or damaging terrain is obvious, the players can freely discuss options when the encounter begins. Terrain can also be revealed during play when it impacts a creature, though it’s often more effective to hint at the terrain’s unusual nature and encourage ability checks that can reveal its effects. “The vegetation is moving, as if blown about by a wind you can’t sense,” can inspire a player to ask if they can learn more, followed by an Intelligence (Nature) or Wisdom (Survival) check to determine the terrain’s effects. If the check fails, the LEVEL MATTERS Damaging and hindering terrain can be exciting, but Scott notes that such terrain has a disproportionate impact on lower-level characters, who often lack ways to mitigate hindering terrain or come up short on the hit points needed to weather continued damage. At the same time, highlevel characters might see such terrain as little more than a resource tax, requiring a couple of relatively low-level spells or readily available class features to deal with. As such, setting up engaging terrain at lower or higher levels often requires additional work to maintain the story and the challenge. character must decide whether to risk crossing the area to learn what it does the hard way. To create damaging terrain, you can take inspiration from magic the characters or their foes might use, including spells such as spike growth, entangle, grease, or sleet storm. You can also use the guidelines in the 5e Dungeon Master’s Guide for creating traps, using the tables to determine how much damage terrain might deal. FACILITATING OR DENYING MOVEMENT Swinging from a chandelier is great fun, and is more likely to become part of a scene when you point out the chandelier and the rope attached to it in an encounter area. Characters are more likely to cut a rope bridge the monsters are using when you describe how old the bridge looks and how its ropes are fraying. Likewise, adding elements that make movement easier increases the dynamic nature of the encounter environment. Bridges, ropes, teleporters, slides, and ramps can all add interest and engagement, helping facilitate the use of the entire encounter area. Such environmental elements can also change the tide of an encounter. The foes might start with the advantage of higher ground, but heroes who can pile up a number of convenient crates can reach those foes. Or an area could feature ladders or even a trampoline the heroes can utilize. When foes are attacking from a hayloft, a barrel of torches can allow characters to turn the tables, lighting the loft on fire and forcing the creatures above to descend. ATTACKS AND POWER-UPS An encounter environment can include elements that provide or boost offensive capabilities. A siege weapon might add a potent way for characters to damage a giant, or provide the means to tear down cover. In a bar fight, broken bottles can serve as improvised weapons, and alcohol spilled on the bar’s surface might be lit on fire. Such elements can be even more fun when they initially favor foes but can eventually be used by the characters. Spellcasting foes might benefit from an arcane circle boosting their spells, until the heroes drive them back and make use of the circle’s magic themselves. A table in an alchemist’s laboratory might hold potions that any creature can drink to gain a benefit, a fact the characters learn while observing their foes. Providing an obvious element meant to boost foes can also be interesting if the characters are allowed to prevent its use. If kobold brigands begin an encounter near a siege weapon but their ammunition is some distance away, the characters have the ability to prevent the kobolds from loading the weapon. DEFENSES Encounter elements offering a defensive benefit can likewise provide solid engagement. If heroes are targeted by ranged attackers, they might be in trouble if they have no cover. But a nearby clockwork fan has a large crank that can be turned to create a wind that blows away incoming arrows, and forces the foes to approach with melee weapons. Defenses can be interesting when they have a limited duration or a means to disable them. An arcane shield might protect an enemy spellcaster until special runes can be removed from four pillars in the area. The fell undead in a ruined temple regenerate all damage until a corrupted relic is restored by bathing it in holy water. The trick is to provide ways the characters can discover this. If the relic or the runes pulse with magical energy whenever a foe would have taken damage, that can provide a clear indication to the heroes of what kind of power is in play. Mundane defenses can work just as well for creating engagement. A ritual is being conducted behind a closed door that the characters must get through, but monsters stand in the way. A pack of undead is on the move, but the adventurers can loosen and drop a rusted portcullis to slow the horde’s approach. If ranged combatants stand on the other side of a ravine, the characters might topple a tree or move wooden planks to create a bridge. And if a red dragon breathes fire from above, the characters can hide in one of two ruined homes—but each time the dragon breathes, that home will burn, preventing it from being used as cover a second time. CHARACTERS ACT DEFENSIVELY Mike notes that players often have their characters act defensively by default. As a result, giving the characters more defenses can cause play to become less dynamic if those defenses provide an incentive to hunker down in one place. To counter this, consider ways for additional defenses to eventually break down, as with a monster tearing through cover, or a magic circle in the process of fading out. Alternatively, create reasons why the characters can use the defenses only periodically. Scott likewise points out that providing defensive-minded characters with alternative—as opposed to additional—ways to defend themselves can help with this problem, especially if those alternative means of defense require or encourage movement. 81 FIFTEEN ENGAGING ENVIRONMENTS Presented below are fifteen examples of environments containing elements meant to engage your players and their characters. You can use any of these examples as is, or as inspiration for creating your own environments. SLIP AND SLIDE Frost-covered terrain features ramps shaped of ice, letting foes or heroes quickly move across a battlefield that would otherwise be difficult terrain. ALCHEMY LAB In an alchemist’s laboratory, any missed attack causes bottles to break and spill, creating a range of short-term hazards. VERTICAL ACCESS Within a wizard’s tower, each level features open ceilings and narrow ledge-floors hugging the inside walls, allowing other levels to be seen from above or below. Teleportation alcoves on each ledge can allow the fight to span several levels at the same time. SHIFTING FLOOR A construction site features automated clockwork cranes that move sections of the floor during a battle, and which suddenly bring different areas of the encounter together or move them apart. The characters understand that they can learn to manipulate the cranes, giving them control over the battlefield. STEP LIGHTLY While exploring a swamp, the characters quickly discover that what seems to be solid ground is actually a sleeping tentacle beast. Missing with an attack or moving without care causes the beast to strike. CRYPT SHORTCUTS A battle unfolds in an abandoned crypt filled with secret passages. The passages allow rapid maneuvering from one side of the fight to the other, but a few of them contain undead that dislike being disturbed. The presence of undead is random, and either side might trigger their appearance. DOWN TO EARTH Enemies start the fight atop a wooden platform, letting them attack with ranged weapons from cover. However, the heroes can cut the supports, causing their foes to take falling damage as they crash down to the characters’ level. WHITE WATER 82 A battle takes place on rafts heading down a river. Each round brings a new threat from the environment, such as low branches forcing all creatures to duck or take damage, or fast-moving rapids requiring an ability check to navigate. CONTROLLED MOVEMENT In a dwarven fortress, a central chamber set with levers allows foes to open and close different sections of narrow corridors, enabling dwarf guards to attack the characters and then retreat. Once the heroes reach the central chamber, they can take control and dictate the conditions of the battle. FIRE BRIGADE During a battle in a burning building, in addition to their normal actions, each creature can attempt to either prevent the fire from approaching them or cause it to spread toward their foes. STAY DRY While the characters fight in a sewer canal, it suddenly begins to fill with water. Ramps and other devices can be climbed to keep the fight going. MARKETPLACE BRAWL A marketplace erupts in an exciting battle. Errant blows might knock over stacks of crates to hinder the characters or their foes, sacks of flour might split open to create obscuring and flammable clouds, or angry merchants could enter the fray to demand that the characters pay for damaged goods. PIT PUSH Multiple pits are set into the floors of a chamber where the walls shoot inward each round, potentially knocking creatures into a pit. It’s possible for the characters to determine which walls will move next, and how far, so as to find a safe place to fight. KING OF THE HILL A battle takes place along the outside of a pyramid, with those atop the pyramid gaining a bonus to attack and damage rolls, whether from magic or from the cheers of a crowd below. The uneven top of the pyramid has space for only four creatures, and creatures can be pushed off with successful blows, leading to constant change at the top. GEYSER RIDES Geysers erupt in a cavern at unpredictable intervals, sending creatures flying upward and spraying them with scalding water. However, riding a geyser also allows creatures to reach the mushrooms growing on the cavern ceiling, which provide magical benefits. ASSESSING A PUBLISHED ENCOUNTER Despite all the care designers take, no published adventure is perfect. It’s impossible for the encounters in an adventure to fit every group’s preferences, or to be playtested for the way every group of characters might approach them. Designers recognize that there’s no way to flawlessly select monsters, motivations, and engagement that will work for every table. So they make use of flexible design to encourage GMs to personalize a published adventure’s encounters. GMs didn’t always understand or even know this, however. Historically, earlier editions of D&D carried a mistaken sense that the words on the page were somehow sacred. “That’s the way the encounter is written,” was used as an excuse to explain why an encounter didn’t work well. Using a published encounter offers many benefits. But as GMs, recognizing that published encounters are imperfect means we must also accept the responsibility to tailor those encounters to our own needs. We want to learn how to assess what an encounter offers, and the changes we can make to improve how it runs at our table. Here’s how. Which are the Key Sections? Which sections receive the most emphasis? In one encounter, terrain might receive a lot of emphasis. In another, the encounter’s focus could be the characters’ goals and how the monsters try to thwart them. Where is the Fun? Ideally, the key sections also drive the fun—within the context of what that means to your players. Ask yourself which sections excite you as a GM, because those will probably also be the ones to excite your players. You want to lean into those sections during play. What’s Confusing? Sections that read poorly, are confusing, or appear overly complex during a quick skim might simply need review to fully understand them. However, confusion can also be a sign that a section doesn’t fit your play style. Note these sections for later review. What’s Missing? Is the encounter missing sections? Does it fail to mention what the monsters do, or lack details for the environment and terrain? Does it seem too simple or lack fun? Make a note of these gaps. ALLIE BRIGGS FIRST LOOK When reviewing an encounter in a published adventure, start by quickly skimming it from start to finish. Note the major sections and what they tell you, at a high level, about the encounter. Published encounters (particularly encounters featuring combat) often have one or more of the following sections, roughly in this order: • Introduction or overview for the GM • Descriptive text to read aloud for the players • Lighting, ceiling or canopy heights, sounds and smells, and other environmental information • Goals or other story information not in the introduction • Terrain mechanics • Features that the monsters or characters might use • Lists of monsters and traps • Monster tactics or scaling • Monster or NPC motivations and roleplaying guidance • Developments or phases of play • Rewards and treasure • Information for moving on to the next adventure section A quick glance over the encounter’s sections can help you understand the encounter framework. Then ask yourself the following questions. 83 WHAT’S MISSING THAT EXCITES YOU? Scott notes that we don’t have to focus on every one of these questions as GMs. Another way to approach a first read is to look for the sections that normally excite you or are best for your style of play. For example, if you like tactical encounters, you might specifically look for monster tactics and terrain. If you love roleplaying and exploration, you’ll look for creature motivations, lore, and interesting features. By using this approach, you’ll be sure to focus on the elements you enjoy most, and can add those elements where they’re missing. Does This Fit the Story? Does the encounter fit the adventure, your campaign, and the developing stories of the characters? Does It Inspire Other Ideas? As you read, you might be inspired to add a plot twist, a new creature, or another element to the encounter. Or a published encounter might give you an idea for another encounter you want to create, perhaps tying into the published encounter through theme or plot. SECOND READ After an initial skim, go back and read the encounter fully. Some GMs like to do this immediately, while others prefer to give it a bit of time (even a day or two) for initial ideas to settle. A second read prepares you to run the encounter, and might correct some aspects of your initial assessment. Something you thought was confusing might become clear, or a perceived deficiency might actually turn out to be a strength. You might also confirm aspects of your initial assessment. You can make notes in the margins, underline or highlight text, or make notes in a separate document to help you when you run the encounter. During this second assessment, you want to focus particularly on the following key aspects of the encounter. ASSESSING THE FOES In a few cases, the monsters, NPCs, and other foes aren’t the key to an encounter. If this happens, you can decide not to worry about those foes, as they aren’t critical to the fun. For most encounters, though, the foes are a key part of the action. You therefore want to assess them carefully. Lore and Story. It’s worth reviewing the lore behind creatures appearing in a published encounter. Monster lore can offer valuable information about a creature’s mannerisms and preferences, which you might otherwise forget. By reviewing monster lore, you get into the heads of those foes, and can better understand how they fit into the story of the encounter, the adventure, and the campaign. 84 Consider which lore aspects are known to the heroes. An ogre mercenary makes a straightforward foe, recognizable on sight. You can describe their massive muscles and stature to emphasize their nature. Any adventurer should know that a giant spider is dangerous, so you can freely describe the venom dripping from their fangs to heighten the sense of danger. Low-level adventurers probably won’t recognize what a cockatrice can do, so you might instead describe the coloration of their plumage and leave their capability for petrification as a surprise to be experienced during play. Monster Stat Block. As described in “Reading the Monster Stat Block” (page 102), you can review monsters in an encounter to understand how they operate, gauge their strengths and weaknesses, and think about how to make the most of their capabilities. Whenever a monster uses a combination of actions or features to be effective, you want to highlight that on their stat block. You also want to look for intersection points between different monster types. If one foe knocks creatures prone, this benefits another creature with many melee attacks, since they can now gain advantage on each of those attacks. Conversely, creatures might have features, actions, or spells not worth using. You can cross those out to make your foes easier to run. In general, ask yourself what makes a stat block interesting in the context of the encounter. If certain aspects aren’t interesting, you can mark them up to change them, or add to them using the monster powers in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22). For complex monsters, consider assigning specific features to particular rounds. An undead wizard might blast characters with a fireball spell on the first round, use a fear-based action on the second round, and then move in to use their life-draining melee attacks on characters not affected by fear. Goals and Tactics. An encounter might have creatures engaging in unusual goals or employing specific tactics. If not, you want to review the stat blocks and lore to create appropriate goals compatible with the encounter. Encounters often feature more than one type of creature—hobgoblin gladiators fighting alongside an ogre battlemaster, for example. You can examine these pairings and what makes them interesting, starting with whether allied foes have slightly different goals and tactics. You can then highlight the differences during play, adding interest and realism to the encounter. Environment and Engagement. You can review how creatures fit into an encounter’s environment, and how those creatures engage the players. If an encounter offers this information, then review these aspects to make the most of them during play. You might make a note next to the stat block such as, “The ogre will try to destroy the bridge,” or, “The bandits use the ropes to move between levels.” If the environment doesn’t fit the monsters well, or if their engagement with the environment is low, you can add those details. “Building Engaging Encounters” (page 76) and “Building Engaging Environments” (page 79) have all the information you need to make those adjustments. Challenge Level. You can assess the overall challenge level of monsters based on their CR and how many of them appear, using the tables in “Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” (page 67) or the information in the “Lazy Encounter Benchmark” (page 70). You can then assess whether the encounter utilizes the monsters to their typical potential, or even above that potential. For example, if normally weak gnome archers are placed behind cover in a place the heroes can’t easily reach, you might treat the challenge level as higher—a medium encounter becoming hard, or a hard encounter becoming deadly. You can then consider how that challenge level fits the resources the characters have available, and whether an encounter under those circumstances will be fun. If a different challenge level would work better, you can make adjustments. Some published encounters come with scaling advice—information on how to adjust the encounter for weaker or stronger characters—which you can use to make changes. If not, you can make your own changes, or add features to monsters to increase the challenge. “Monster Difficulty Dials” (page 27) talks about making adjustments to encounter difficulty on the fly. “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22) present lots of options for adding features to monsters. And challenge level is discussed in more detail in “Defining Challenge Level” (page 105). SURPRISES AND DEVELOPMENTS When preparing an encounter, you want to differentiate between what should be obvious to the characters initially, and those elements that can be learned during the course of the encounter. Aspects that should be known might need to be clarified for characters. For example, if the published encounter says negotiation is possible, you can review EXITS AND ALTERNATIVE ENDINGS Scott advocates always checking a published encounter for exit points and a range of possible endings, beyond the often-default expectation of all the foes—or all the characters—being killed. Are the creatures in an encounter likely to negotiate for surrender or offer an alliance? Will some of the creatures attempt to escape if overwhelmed? Similarly, recognizing the difference between an encounter the characters can run from versus an encounter that demands a fight to the finish can help you prepare for a range of outcomes. whether the encounter gives the characters reasons to try this. If anything that should be clear isn’t, you can make a note to clarify that during play, or add ways that the characters can learn the information. Some elements of the encounter might initially be hidden or unclear, with the intention of having those elements revealed during play. You should make a note of such elements, and think through the conditions by which characters can discover them, or when they should be surprised by them. It’s okay if characters spoil a surprise through clever or lucky play, so always keep that possibility in mind as well. Developments are often events that take place after the first round of combat—making them easy to forget during play. To prevent this, make a note of when a development occurs, and place the note where you’ll see it. For example, if a fog rolls in at the start of round 2, you might add an entry to the initiative tracker reminding you of that. As noted earlier, for complex monsters, you might want to assign specific actions to particular rounds. And if certain creatures surrender when reduced to below half their hit points, you might write that next to their stat blocks. If an encounter is simple, you can consider possible developments for it. A foe might issue a challenge or share interesting information at a particular time. Making a note of this can help keep you from forgetting the development. MINIATURES, MAPS, AND TERRAIN If you play with miniatures and maps or crafted terrain, your read-through of an encounter should also assess how best to portray the encounter physically. You don’t need perfect miniatures or maps to have a great time, but choosing miniatures effectively can help clarify who’s involved in a battle. Can the players tell two groups of creatures apart? If important terrain elements are featured on the map, will those be clear? Can you use simple tools like wooden blocks to signify elevation? A bit of time spent in preparing miniatures, maps, and terrain according to the specifications of the encounter can facilitate a great session. ONLINE PLAY You can ask similar questions for online play, selecting maps, creature tokens, and terrain markers that will help players understand what they face and the options available to them. When reviewing a published encounter, ask yourself whether you can easily use a generic map (a standard dungeon chamber, a default forest clearing, and so forth), or whether you want to look for a more distinctive map and more detailed tokens to properly capture the features described in the encounter. 85 BUILDING CHALLENGING HIGHLEVEL ENCOUNTERS As characters rise in level, many GMs find it harder and harder to challenge those characters and their players. Why is that? Characters gain more features as they level up than monsters do, and the players choose many of those features carefully, if not optimally. Likewise, players hone the use of their characters’ capabilities through repeated play, while GMs are often running higher-CR creatures for the first time. The game’s math also takes some of the blame. At low levels, monsters deal enough damage to kill characters outright, and the regular rules for building encounters based on challenge rating often result in low-level encounters that can easily wipe an entire party out. At high levels, the reverse is true. It can seem impossible for monsters to deal enough damage to threaten a character, let alone kill one. So with all those factors in mind, let’s take a look at how we can build high-level encounters that will be challenging, fun for the players, and fun for us to run. ANALYZING CHALLENGE Challenging players and characters becomes easier if we look at challenge as more than just hit points. It also helps if we understand our players and their characters, as well as our own tendencies as GMs. STORY AND FUN ARE MORE IMPORTANT In the quest for challenge, we should never forget what matters the most: whether the GM and the players are having fun. Although a nail-biting encounter can be exciting, many players have even more fun with an easy win. Easy wins can make players feel awesome! Story is one of the key ways to provide fun. A good story resonates with the players. A game’s story is more likely to be a good one when the players see their characters’ actions matter, when there are secrets to unravel, and when the characters’ goals and aspirations are woven into the game. If a fight is easy but has a great story, that’s almost always preferable to having a challenging fight with a so-so story. The first step to making high-level play great is thus to create a great story alongside a fun and engaging encounter. That way, even if the encounter isn’t as challenging as you might have hoped, the game session can still be fun and interesting. Think about and ask yourself the following questions when creating a highlevel encounter, even before you work on making it challenging: • Are the monsters interesting, and fun to engage with? Do they do interesting things, and do they advance the story? 86 • Does the encounter engage the characters, giving them heroic and fun things to do? • Does the encounter matter? Are there choices with repercussions, opportunities for clever play, secrets to learn, plots to advance, and threats worth overcoming? • Are the decisions and actions epic, reflecting the importance of the high-level heroes? At lower levels of play, a straightforward combat encounter can be exciting even when it’s not part of a perfect story—because the risk of death creates its own story. So as the risk of death becomes mitigated at higher levels, it becomes important for the GM to replace the narrative tension that the threat of death brings to the game. High-level play should therefore come with exciting story. The heroes are saving entire lands, if not the world or multiverse. Threats such as planar intrusions, the essential nature of magic becoming corrupted, or an ancient terror that can gain unstoppable power—if you create an engaging story around such concepts, your encounters will be fun regardless of whether the fights are hard or easy. CHALLENGE IS MORE THAN DAMAGE Encounters inevitably become boring if the only challenge the characters face is hit point loss. So by remembering that challenge is more than damage, we can enable more ways to create engaging encounters that feel epic, especially as the characters gain levels and face increasingly formidable threats. The basic nature of an encounter can make it seem challenging and rewarding, even if the combat ends up being easy. Consider the following examples: • A mighty creature threatens to destroy a town or city that is important to the heroes. Each round, in addition to their attacks, the creature also deals damage to buildings. The faster the characters defeat the creature, the more of the settlement they can save. • The villain is protected by an arcane energy field that greatly reduces incoming damage. Characters can destroy the arcane engine, which hovers high above the ground. Flight and teleportation, as well as other capabilities, become part of the way to address the challenge. • The dragon the characters fight isn’t just flying— they’re also ending each turn behind clouds. This puts spellcasters with the ability to cast control weather, or other characters with similarly powerful mastery over nature, in a position to cancel the dragon’s advantage. (“Lightning Rods” on page 44 has lots of ideas on how to customize creature traits and tactics to allow the characters to show off—and to feel great doing so.) • As the heroes prepare to face the head of an enemy army, they also must raise the spirits of their nation’s people, and heal dozens of wounded soldiers so they can return to the battle and keep the enemy from outflanking them. A scenario of this sort can challenge players to come up with an inspiring speech, knowing that the tide of battle might change if their speech is a good one. LEARNING OVER TIME As we run encounters as GMs, we can take measure of what works and what doesn’t. By isolating what made an encounter easy and how to change that, you can change your approach to increase the challenge. “Building Engaging Encounters” on page 76 has lots of ideas on this topic, in addition to the following examples. Starting Distance. You might have been really excited to use monsters who felt powerful for an encounter, only to discover that most of them never got to do anything. Spells might have prevented some from acting, while other creatures were cut down before they could reach the characters. So make a note regarding which types of monsters become less effective when they start out grouped together and far from the characters. Then next time, test a way to place the monsters right among the heroes, perhaps cloaked by illusions or coming out of doors, crates, or thick underbrush. Obvious Linchpin. You might spend time preparing a powerful spellcaster mini-boss, setting them up at an altar, guards before them, ready to tear into the characters with their magic. The players, however, immediately focus fire. A few ranged attacks, spells (including castings of counterspell), and attacks by melee fighters with mobility, and your caster won’t get to do much. So make a note about how making the boss so high profile played against the encounter setup, and think about providing the spellcaster with some protection next time—an arcane barrier, a shield guardian, resistances, and so forth—that can help prevent them from being taken down. Alternatively, you might have the caster appear from behind cover, making it likely that they get at least a round to cast a strong spell. Darting behind full cover each time they cast could buy them a couple of rounds, and portals or other ways to move around to different areas of cover could protect them further. Unhittable Defense. A fearsome giant deals tremendous damage—if they can actually land a blow against the characters. The one time you think you’ve actually hit the multiclassed tank, out comes a shield spell or a class feature to make the attack miss. When this happens, make a note of it. You want to reward the player of an optimized character with their desired play experience, but when you can’t count on hitting that character, you need more than one monster who hits hard, or ways for the hardesthitting monsters to reach other targets with lower ACs. When you want to challenge the tank in ways beyond weapon attacks, make use of damaging terrain, spells, illusions, and other complications to keep them on their IT’S NOT YOUR FAULT Mike often talks about the “triangular growth of character power” (discussed in “The Relative Weakness of High-CR Monsters” on page 53). Characters don’t become stronger linearly as they increase in level. They become vastly more powerful and capable. On his blog, Teos has analyzed the average hit points of characters and compared it to the average damage of creatures in an encounter. As characters increase in level, foes appropriate for those characters fall farther behind. For example, a 12th-level party has somewhere around 375 total hit points. The official rules state that a battle with a CR 16 creature should be a tough challenge, but such a creature deals an average of 46 damage per round—meaning they need 8 rounds to defeat the heroes even if every attack hits! toes. Similarly, characters who fight primarily at range often avoid damage, but you can design surprises for them as well. That obvious cover … it couldn’t possibly be an advanced mimic who grapples and deals a ton of damage, right? Surely not. Smooth Operators. Some adventuring parties operate like a well-oiled machine. Each character has a role and plays it well. Make a note of this in your games. Usually, it’s good to not just allow but to reward that kind of play. But what happens when the character who bails others out of trouble is in trouble? When the healer can’t heal because healing magic doesn’t work in an encounter area? When the terrain restrains, making it hard for characters to move around? By playing against the characters’ strengths, you can test what happens when the battle is fought on your terms. However, this is a technique to be used sparingly. Otherwise, it can feel as though you’re being antagonistic toward the players by deliberately countering their characters’ best combat options. What Works. Just as importantly, when a high-level encounter is hard, you can examine that. Where were the monsters in relation to the characters? What let the monsters be effective? How can you use this as a template for future combats? CHALLENGING HIGH-LEVEL CHARACTERS You have a fun story. Your encounter challenges characters in ways other than damage. You’re analyzing your games and learning as you play. Now it’s time to add specific techniques to make your high-level encounters more challenging. JUST ADD DAMAGE This sounds trite—and remember that challenge is about more than damage. But dialing up damage to boost the challenge for high-level characters is a good first step. If your encounters lack challenge, and especially if the players seem unimpressed, increase damage. A strong blow, even if a character still has plenty of hit points, feels dangerous. It wakes the players up. 87 Mike loves using two or even three bosses in one encounter! When you take this approach, by describing each of the bosses and showing off their capabilities, you can create an encounter with no obvious linchpin. Similarly, Mike is a fan of waves of foes, as discussed in “Building and Running Boss Monsters” on page 31. The characters might quickly defeat the spellcaster protected by guards, but when a second guard patrol then shows up, the loss of the first obvious linchpin isn’t as significant—and the characters have expended the resources that enabled them to take down the linchpin so quickly. Waves of foes from unexpected directions can also pressure the more fragile characters who hang back from battle, forcing a change in tactics beyond just pummeling the obvious boss. To make things even more interesting, the boss or linchpin can arrive as part of a wave. Have the characters start out by battling guards, then have the boss arrive after resources have been expended. 88 The easiest way to increase damage is to add more dice to every attack a monster makes. If a foe deals 2d8 + 10 damage, try making that 3d8 + 10. If that’s not working, try 4d8 + 20. If you’re comfortable doing so, you can simply double a creature’s damage output if they need a strong boost. From a story perspective, you can easily explain a change in a monster’s damage as a response to something the characters have done. When a monster misses on their first attack, they become enraged and start to hit harder. When reduced to half their hit points, a creature’s tenacious nature drives them to hit harder in an effort to stay alive. You can also add one or more monster powers (see “Building a Quick Monster” on page 4, “Monster Powers” on page 15, and “Monster Roles” on page 22) to increase the damage dealt by key foes. If a foe hits hard but only takes on single targets, add an aura so they deal damage to every character who comes near. You can also add a power that gives an additional attack, or even one that deals damage when a monster dies, either exploding or leaking lethal energy. You can add damage in an encounter from sources other than creatures as well. If your original idea for a warped Outer Planes landscape was to have colored grass that restrains the characters, you might decide that on the second round of combat, the grass begins to deal damage as well. (For more ideas on this topic, see “Building Engaging Environments” on page 79.) KEEP THE HEROES BUSY When a bunch of high-level characters are dealing significant damage, their foes can drop quickly. So challenging encounters must find ways to tie up the characters using more than just combat. This approach functions like splitting the party, but all the characters are present. They’re just pursuing more than the singular goal of defeating enemies. To keep the heroes busy, consider any of the following scenarios. Save Something. The characters came to retrieve a holy artifact or ancient tome—and during the battle, the item is in danger. Maybe the fire used in a ritual grows out of control, and will destroy the item unless the characters do something. Or maybe a beloved NPC is dangling over a pit that looks like a giant maw. If the characters must spend actions and resources to save someone or something, it limits their ability to just fight monsters. MATT MORROW MORE THAN ONE BOSS OR MULTIPLE WAVES Activate or Disarm. A terrible trap drains the characters’ life essence until it is disarmed. Four pillars around the encounter area must be deactivated to bring down the arcane shield protecting the villain. Any device that needs to be shut down during a fight can keep the characters busy—with the location of the device made difficult to reach, whether it’s floating in midair, surrounded by damaging terrain, or accessible only through a portal that must be activated before use. Penalty Box. A glyph or other magical effect could put a character into a maze spell or take them to a pocket dimension where they face a challenge before returning. Stepping on the wrong flagstone might teleport a character into a sarcophagus. A lot of monsters can swallow characters, limiting their actions for a time. All these scenarios are effective ways of isolating characters and keeping them busy, but you want to make sure they’re fun. Perhaps while within the belly of a monster, a character finds an unexpected treasure. The inside of a sarcophagus might have a note hinting at how to defeat the boss villain. Make any penalty box feel like part of the adventure, not a way to pick on specific characters. MODIFY THE ENCOUNTER BUDGET Some GMs create encounters using the core rules in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, adding up the XP of creatures in an encounter and using that total to determine the challenge level (easy, medium, hard, or deadly). A benefit of this technique is that if encounters consistently feel too straightforward, you can easily alter your budget, and thus alter the associated challenge. If moderate encounters consistently feel easy, try increasing the XP budget of a moderate encounter—or simply use the threshold for a hard encounter. When building a deadly encounter, you can take the difference in XP between the minimums for hard encounters and deadly encounters, then add that as the new minimum for a deadly encounter. However, be careful to not adjust the budget in a way that adds more creatures than you can easily run— especially creatures of different types. Adding another hill giant to an existing brute squad is fine. But adding a troll, a cyclops, and an advanced ogre is likely to overwhelm you. Any XP budget is usually better spent on creatures you can run easily and effectively. Another way to modify the encounter budget is to worry less about balancing encounters, and to simply run more encounters before the characters can take a long rest—as long as doing so fits the story and pacing of your game. “On Encounters per Day” on page 93 offers advice on this topic. The Lazy Encounter Benchmark. If you use the lazy encounter benchmark (from the section of the same name on page 70) instead of the core rules’ XP encounter budgeting, you can increase the threshold of encounter challenge by pretending a party has more characters. If five characters routinely find hard encounters less than CAN YOU WEAR IT? CAN IT BE A MOUNT? Talking of mounts reminds Teos of some of the surprises organized play has provided. A fire giant with a pyrohydra “backpack” they carried, the hydra’s heads breathing fire in every direction. Druids using Wild Shape to serve as mounts for powerful creatures. Teleporting creatures carrying foes into battle, and then far away to safety. High-level encounters are a great time to get a bit weird, because the characters can likely survive even if you accidentally push a concept too far. Plus the unusual nature of such an encounter will surprise the players and engage them. challenging, build encounters as though the party had six characters—or even more characters, until you find the right balance. This technique can easily be used with most online encounter-creation tools. CUNNING TACTICS Because the effectiveness of a high-level party often comes from the tactics of the characters and players, keep in mind certain monster tactics specifically designed to challenge high-level characters in return. Prevent or Draw Focused Fire. Is it obvious to the players and characters which enemy should be ganged up on and defeated first? If so, describe all your foes as fearsome and interesting in different ways, making them all seem worthy of attention. You can also use descriptions during combat to make the least damaged foes seem more important than they are, leading characters to return fire when attacked by those foes. You can adjust position on the battlefield, so that the most important enemies aren’t near the encounter locations where the characters want to be. This can split the party, forcing some to focus on specific foes or locations, while others chase down the one foe dealing a ton of damage at range. Alternatively, sometimes having an obvious main foe can be used to your advantage. The big elemental in an encounter is a sack of hit points, and melee characters take fire damage each time they hit that foe. Meanwhile, the elemental’s seemingly unimportant allies are the real threat, but their innocuous appearance makes the characters downplay that threat. Monster Roles and Placement. As described in “Monster Roles” (page 22), you can often think of the characters’ foes as a team, each using separate but complementary tactics. So place each foe where they can best fulfill their role. Defend vulnerable or key targets, whether through harmful terrain, features such as self-firing arcane ballistas, or foes such as a spellcaster benefiting from cover or magical defenses. Unless there’s a story reason to not do so, you can place creatures where they’ll be most effective right from the start of battle. Just ask yourself whether a particular foe would want to 89 start next to characters, near them, far away, or hidden or behind cover. Counter Defenses. If the damage resistances high-level characters often have are a problem, you can consider ways to remove them periodically. A dragon’s breath weapon might cling to characters, dealing damage for multiple rounds or temporarily removing resistance to the breath’s damage type. A trap, magical effect, or environmental feature can do the same. You might even let the characters learn that there are ways to reverse these effects by interacting with some aspect of the encounter. MONSTER–TERRAIN INTERACTIONS A powerful way to give foes an advantage and increase the challenge in high-level encounters is to create an interaction between the terrain and your monsters. “Building Engaging Environments” (page 79) cautions about not overwhelming low-level characters. But with high-level characters, you can safely cut loose! Many creatures can fly, letting them stay away from the heroes or forcing characters to expend magical resources to take to the air. But a black dragon can also swim through pools of acid, while most characters can’t. This lets the dragon use such pools to move around an encounter area—or even hide in a pool while their breath weapon recharges. A giant might push a pillar down on a character, dealing the same damage as if the giant had hit with their best melee attack, and also causing the character to be restrained. Incorporeal undead can fight in collapsing ruins, uncaring as parts of those ruins fall and pin characters underneath the rubble. A massive demon might set an encounter area on fire while fighting, potentially dealing damage to the RUNNING A BATTLE ACROSS TWO WORLDS In a particularly memorable high-level battle, Mike built an encounter designed to split the party—not just into separate rooms but across separate worlds. For months, the game had set up the idea that one of the characters had a deep friendship with a giant they thought was dead. But what none of the characters knew was that the nasty ancient blue dragon sorcerer boss had actually trapped the friendly giant in amber. When the characters entered the dragon’s sanctum, the trapped giant was hanging above a pit leading into the Nine Hells—whereupon the dragon snapped her clawed fingers and the amber prison fell. Without a second thought, the character bound to the giant leaped in after them. Thus began a battle across two worlds, with some characters fighting the ancient blue dragon sorcerer on one side and others fighting a host of devils to protect their friend in a hellish arena. Only through the careful use of a powerful cubic gate did the characters survive, teleporting across worlds for the occasional bout of healing before popping back to their home world to defeat the dragon. 90 characters each round. And similar effects might hurt the characters even as they provide a boon to foes. In a dread temple, waves of necromantic energy could heal undead while damaging the heroes. Curtains of fire could provide concealment for fire elementals, while also burning any character who moves through them. BREAK THE RULES Our world uses physics, but a magical world can ignore or bend the expectations physics creates. Similarly, the world of the game creates expectations which we can change, creating exceptions that can be validated through story. A fire giant king might be no regular fire giant, as you increase your encounter budget as described above to create a stronger threat. You can have the king deal more damage, letting them hit harder than expected. You can also pair them with a powerful mount, such as a massive hydra that breathes fire and is immune to fire damage. A magical monster on another plane might be able to use their movement to simply will themself to be anywhere in the encounter area. A creature who doesn’t normally fly could be a winged variant who does. A creature might wear self-repairing armor, manifesting as temporary hit points granted at the start of each of their turns. A death knight becomes truly terrifying when you give them the ability to tear apart the magic of a forcecage spell with their bare hands. You can usually exceed the game’s expectations when creating high-level challenges because high-level characters are so resilient. They can even recover from death … unless you counterspell their revivify. One of the best ways to break the rules is to take monster features you love and add them to other monsters—but you need to do so convincingly. A remorhaz is a great threat, because whenever characters hit them with melee attacks, those characters take damage. You can add that sort of trait to any elemental creature, or to a monster covered in spikes or wearing spiked armor. You can give a monster a reaction to reflect a spell back on a caster, with or without an opposed check or saving throw. Or you might have a creature targeted by a spell cause the spell to target the caster as well, evening the score a bit. You can have creatures who take a final attack when they die, upping their damage output as they go down fighting. The monster powers presented in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4), “Monster Powers” (page 15), and “Monster Roles” (page 22) present all kinds of ready-to-use features that let you scale damage and alter effects to meet your needs. ON THE FLY When preparing encounters for powerful high-level characters, keep in mind that the tricks and tools discussed here can also be used on the fly to make encounters more challenging. If you do so, don’t worry about picking just one or two. Use several ideas and options, one after the other, until the encounter becomes compelling and fun for both you and the players. EXIT STRATEGIES The other sections of this book talk about lots of different options for setting up and running combat with monsters and other foes. But when thinking about the beginning and middle of a fight, many GMs overlook all the possible endings of a fight—and the ways in which having ending options in mind can help keep an exciting combat from becoming a total-party-kill scenario. In the earliest editions of D&D, encounter design was much more of an art than a science (as discussed in “The History of Challenge” on page 97). As such, adventures for those older editions typically set the GM up to assume that every fight might go in any possible direction, with four cardinal points on that combat compass: the characters win; the monsters win; the characters flee; the monsters flee. But as later editions of the game have pushed toward the holy grail of balanced encounter design, and an implicit math-backed guarantee that a certain encounter should turn out a certain way, the fine art of not fighting to the bitter end has become minimized. A whole lot of players have never learned the value of fleeing a fight their characters can’t win, and GMs are reminded to ignore alternative options for ending fights by the number of published adventures making use of the words: “These creatures fight to the death.” To help prevent an exciting encounter from becoming memorable for all the wrong reasons, this section encourages GMs to think about monster motivations, a broader range of rewards for combat beyond just “winning,” hooks that you can use to have foes roleplay their way into a surrender scenario, and making sure that the physical setup of encounters affords characters and monsters alike the ability to flee from a fight. PLAN YOUR ENDGAMES Figuring out how to end a fight in a satisfactory way that doesn’t involve one side claiming complete victory is a difficult thing to do in the moment. While engaged in running combat, a GM already has a lot of things to think about. As such, by the time you realize that an encounter you thought would be an average challenge at best is about to become a smorgasbord of player-character pâté, coming up with a believable plot twist to take the fight to a different end can be tough. You want to think about those plot twists and possible alternative endings ahead of time, so that you’ve always got one or more ready to drop into any fight. The following guidelines can help. ASSESSING MOTIVATIONS Only rarely do the monsters in a fight have the single motivation of “destroy or be destroyed in turn.” Mindless undead or constructs are great for those kinds of fightto-the-finish encounters when that’s what you want to run. But almost all other creatures, including intelligent undead and the game’s full range of monstrous and NPC foes, have other motivations for getting into combat—and equally powerful motivations that can inspire them to get out of combat. (“Roleplaying Monsters” on page 48 talks more on this subject.) STAYING ALIVE A monster who fights and runs away lives to fight another day, and even creatures who can’t articulate that old adage can live it. Every NPC, from the most loyal guard to the most fanatical cultist, has a sense of self-preservation that can inspire them to flee when the fight goes bad. Likewise, animals, aberrations, draconic creatures, and more all have reasons to want to live, whether those reasons are guided by intellect and self-awareness or by instinctual need. Monsters who draw part of their combat strength from fighting as a team or in a pack are especially open to reevaluating the odds of survival in a battle as their allies start to drop around them. Whether the characters fight a pack of wolves or a mercenary band, those enemies can easily tell when the tide of battle shifts to create a fight they can’t win, triggering a perfect opportunity for an offer of truce—or for the enemy side’s sudden flight from the battlefield. ALTERNATIVE REWARDS A pack of wolves on the hunt most often have sustenance as their goal, not violence, when they surround characters in the wilderness. One way or another, bandits get into that line of work for material gain. And most sapient creatures who routinely enter into combat understand what kind of edge magic can give them in battle. As such, player characters looking to end conflict early often have the ability to buy their way out of a fight. Dropping food for hungry predators; offering coin or other valuables to brigands, pirates, or cultists; or offering magic or service to sapient monsters in the hope of ending a violent misunderstanding can easily let the characters reshape the scope of a fight. Alternatively, a foe aware that they are about to be trounced by the characters might offer them a reward or their own promise of service in the interest of ending combat. CUT OFF THE HEAD Many times, the ferocity of a group of creatures in battle is inspired by strong leadership, whether a pirate captain able to whip a ship’s crew into a fighting frenzy, a mage summoning magical creatures to do their bidding, or a group of zombies responding to the will of the death knight who directs them to attack. Having a clearly identified boss who controls the rest of the enemy combatants in a battle gives the characters a clear line on ending a fight early. Once the boss is dispatched, you can have their minions flee, or let them fight on in a less organized fashion to give the characters an edge. 91 CHANGE OF ALLEGIANCE Teos likes the potential that comes from characters asking surrendering foes to join them. As the GM, you get to decide how long this alliance will last, and how thoroughly the surrendering foes comply with requests—particularly ones that endanger them. It can be good to come up with a goal (other than treachery) for the surrendering group, whether that’s simply not to lose any more members, or to gain enough treasure to make the truce worthwhile. This kind of setup provides a realistic roleplaying hook to communicate to the players, and from which tension and compromise can emerge. If the characters’ newly made allies are pushed too far from their goal, it’s time for the alliance to end in a way that will further the goal. This might mean retreating at night, renegotiating, or attacking when the characters are vulnerable. CAN’T WE JUST TALK? Whether on its own or as a lead-in to convincing foes to stand down in some of the scenarios above, negotiation and detente are time-honored traditions for ending a fight. Though combat is one of the most exciting aspects of fantasy roleplaying games, it’s almost always easier and less costly for both sides in a conflict to not fight. So after a few rounds of exciting combat, don’t be afraid to show the players and characters that detente is a fine alternative to one side or the other being thoroughly beaten down. Rather than having the party’s most charismatic character take a solo role in talk meant to end hostilities, you can engage the whole party in negotiations by calling for a group ability check using different abilities and skills. This lets everyone play a part, from the sorcerer making Charisma (Persuasion) checks to set out the deal, to the cleric making Wisdom (Insight) checks to help determine which foes are most open to negotiation, to the barbarian quietly making Strength (Intimidation) checks to warn the other side what happens if discussions break down. In the event of a failed group check, you can allow the negotiations to successfully end hostilities anyway, with the failure simply creating a complication surrounding the truce. For example, although the leader of a group of assassins agrees to end a potentially deadly fight with the party, one prideful member of that band feels humiliated at being forced to stand down, and can return as a longterm foe of the characters in subsequent adventures. INS AND OUTS 92 In addition to the many social baselines that might allow a combat encounter to be called off early, adventures— particularly site-based published adventures—have another important requirement for GMs who want to keep exit conditions in mind. Specifically, one or more actual exits. Just as recent editions of the game have seeded the expectation that every fight should go to the bitter end, many of the adventures of those editions focus on a linear encounter setup that can make it difficult for characters to break off from an encounter without interrupting the expected flow of adventure events. In a site-based adventure, this idea most often manifests in a map that features little or no empty or safe space for characters fleeing a fight to fall back to. If fleeing one encounter only brings the party immediately into the orbit of the next encounter, not much is gained—especially if some of the combatants in the previous encounter are in hot pursuit. Likewise, you can set up the most entertaining surrender-and-flee scene for a goblin mercenary band who realize the party are way above their pay grade. But if the mercenaries don’t have a way to slip safely and quietly out of the adventure, the characters are just going to run into them again. SIDE ROUTES Whatever the main route the characters are expected to take through an adventure (whether in a dungeon, a city, a noble’s estate, or what have you), make sure the adventure’s physical locations hold side routes that can be fallen back to. If you set out that the Forest of Eternal Death promises a horrid end to all those who stray from its single path, characters or monsters breaking off from a fight in the forest might have nowhere to go. If it doesn’t make sense to have prebuilt side routes in a location, secret passages and alternative pathways (waterfalls, air shafts, fast-flowing streams, sinkholes, and so forth) also offer good escape routes for both characters and monsters. SAFE HAVENS Unless it makes sense for creatures (especially characters) to not be pursued after fleeing a fight, it’s important to have locations where a party can safely regroup. Stumbling upon a secret room, or having previous knowledge of a section of a fortress or ruin where guards don’t regularly patrol, can give fleeing creatures respite before taking on new threats. And combatants on both sides of a fight might be able to make use of illusions or other magic to create a safe space while remaining in enemy territory. RIPPLE EFFECTS Any group that can depart from an encounter rather than falling victim to it provides a potential catalyst for unexpected changes in an adventure—especially a published adventure that doesn’t expect that group to survive. In a site-based setup, a group of NPC adventurers who stand down from a fight with the characters and agree to go their own way might take care of subsequent threats before the characters get to them—or might rile up those threats out of spite for when the characters finally arrive. In an event-based adventure, enemies who survive combat because the characters let them go might become reluctant allies of the party from a sense of hard-won respect. Or they might double down on their nefarious plots, furious at having been bested by the party and anxious for revenge. ON ENCOUNTERS PER DAY In many discussions, the ideal number of combat encounters a group of characters can face before taking a long rest—often described as “the adventuring day”—is focused on resource attrition. But although draining resources is an important consideration, it isn’t the only factor in assessing encounters, nor the most significant. This section examines how the number of encounters in an adventuring day impacts play, enables specific stories, and contributes to the overall level of challenge those encounters create. WHAT THE RULES AND OFFICIAL ADVENTURES SAY In talking about the adventuring day, the 5e Dungeon Master’s Guide states that an adventuring party can handle roughly six to eight medium or hard combat encounters in a day, interspersed by two short rests. These numbers are likely based on typical character resources—hit points, spell slots, and so forth—but their context is never explained. More importantly, those numbers aren’t given as a recommendation. (“Defining Challenge Level” on page 105 provides recommended maximums based on every encounter challenge level.) The fact that these numbers aren’t recommendations can be seen in the design of the game’s many official adventures, which vary greatly in the number of encounters per day. In some scenarios, the characters might undertake a week-long wilderness trek with only a single combat encounter. Other scenarios might feature a dungeon with a dozen encounters. A typical four-hour one-shot or organized play adventure usually features three to four encounters in a single day, often of medium to deadly difficulty. the challenge of running out of resources, that drawback becomes a special experience. (This idea is expanded upon at “Dictating Rests” below.) When the story doesn’t force the heroes to continue, players generally prefer to decide whether to press on for greater progress and rewards, or to stop to rest and recuperate. As discussed in “Defining Challenge Level” (page 105), the difficulty of an encounter does impact when characters need to rest. However, resting is even more valuable as a way to establish the pace of play. Rests are natural break points, allowing characters, players, and GM to step away from the tension of combat, engage in interparty roleplaying, discuss character and adventure goals, and plan for the next set of adventures. THE RIGHT NUMBER So what number of encounters should a GM use? Ultimately, the right number of combat encounters in an adventuring day is as many as makes sense for the story and your world. You might set up just a few encounters MATT MORROW DRAINING RESOURCES As noted, the arbitrary number of six to eight combat encounters in a day is likely based on available resources. Characters start the adventuring day fresh, and as they face foes and other challenges, they use up spells, limited-use class features, and magic items. Running out of resources and being forced to face another fight is problematic. Characters who lack healing, have minimal hit points, have no spell slots, and have expended their limited-use class features—yes, that is challenging. It’s also frustrating if it happens too often. As such, GMs should consider using resource attrition sparingly, and tying it to strong story developments. In situations where the players understand 93 in an inhospitable region, then dial up to many possible encounters in a populated city or a forest teeming with beasts and monsters. The number dictated by the story can then be adjusted based on play impact and story beats. These design goals are the key reasons why adventures often vary the number of encounters in a day. STORY IMPACT Start by thinking about the story. When the characters engage in an overland trek, a single combat encounter in a day can break up the travel nicely, painting a picture of the environment and the foes who live there. A self-contained encounter story, such as a lazy troll under a bridge who demands payment to cross, or a chance encounter with a pack of beasts, helps you tell the larger story of a desolate wilderness where dangerous creatures live and hunt. When the characters explore a dungeon, you can instead set up several encounters spread across a series of cramped quarters joined by twisting, sarcophagus-lined corridors. This larger number of encounters perfectly fits the story of ruins crawling with threats. So ask yourself what threats should be present in the setting, and how those threats can be best captured as encounters. Then use the number that best fits the setting as you portray the story you want to tell. PLAY IMPACT An adventuring day with lots of short encounters feels different from a day with one or two long encounters. Over one session of play, changing the number of encounters helps you vary the feel of the game, keeping the players’ interest levels high. You can thus select the type of adventuring day that will help you create the desired play experience. When a day features a single encounter, that encounter is likely significant. You have one chance for this encounter to impart your vision of a particular part of the setting and the story. For example, on a wilderness trek through a primeval forest, you might create a single encounter featuring a gargantuan dinosaur among bubbling tar pits. You can easily lean into the pulp feel of this encounter, with the monster making the most of their capabilities, and the terrain helping to shape a memorable and interesting fight. With just a single encounter, the players get a strong feeling for the lands the characters travel through, in addition to a great play experience. But you could instead use multiple encounters to mark out one day of a wilderness trek. You might decide to make each encounter tougher than the previous one, building a sense of dread. Before they even begin travel, the characters might hear stories of the swamp teeming with undead. As they traverse the swamp, they glimpse roaming zombies, easily evaded at first. They then face a series of encounters, with your story goals spread across them so that each tells one facet of the overall story. The first encounter could feature skeletons in the tattered military garb of the nation controlling the 94 swampland. The second encounter could feature zombies and skeletons in the uniforms of this nation and a rival, painting the picture of an ancient battle. A third encounter with ghouls and a ghost could take place at a main battle site, loaded with lore about how one of the armies’ clerics tried to animate their dead soldiers to gain victory, but instead doomed everyone. MULTIPLE APPROACHES These approaches aren’t exclusive, and you can consider both story impact and play impact based on your design goals. As GMs, we always want to periodically step back and assess the patterns of play in our games. Are our dungeon excursions always composed of three to four encounters? Are our wilderness treks always a single encounter? Breaking out of established patterns can surprise the players, even as it makes our storytelling more complex. PACING AND THE PILLARS OF PLAY When the adventuring day features a single encounter, we have a limited canvas with which to capture the three pillars of 5e play—roleplaying, exploration, and combat. When we use multiple encounters in a day, we have more opportunities to play with pacing and activate different pillars of play. As with the general approach to choosing how many encounters to run per adventuring day, think about the effect of these broadly different approaches. A SINGLE COMBAT ENCOUNTER In an attempt to keep play exciting, a single encounter in a day often features just combat by default. But it’s better to choose the pillar you want to feature in a single encounter based on your story and the encounter’s place in the campaign. There are times when roleplaying or exploration deserve the focus and will create a better experience, just as there are times when combat is more exciting for the players. When focusing on combat for a single encounter, you can add separate roleplaying or exploration experiences during the remainder of the adventuring day. With no further threats at hand, the pacing of additional events allows the characters to rest and regain resources. And even when a single big encounter is primarily focused on combat, you can increase its complexity by weaving roleplaying or exploration elements into it. Make it clear that sadistic dwarf warlords are forcing a band of goblins to fight, and the characters might encourage the goblins to switch sides. In a fight against a golem who appears impossible to defeat, let the players deduce that arcane machines along the walls of the golem’s sanctum can shut down—or heighten—the construct’s defenses. In the same way, you can focus on exploration or roleplaying as the main pillar of play, then add an aspect of combat to that play. While the characters explore a ruin, a spider attempts to leap onto an isolated character for a quick fight before exploration resumes. Or an encounter might begin as a fight, then highlight roleplaying when both sides realize they have a reason to work together. MULTIPLE COMBAT ENCOUNTERS When exploring a hillside riddled with caves, some of those caves might feature foes who can be engaged in roleplaying encounters. At the same time, roleplaying or investigation can provide insight into certain aspects of the setting, helping the players determine which creatures live in the caves and why. You can adjust the length of the many possible encounters in and around the caves with more or fewer foes, and by varying complexity. Doing so creates different experiences to engage the players’ interest, and to surprise the characters as they explore each cave and steadily gather more information. With multiple encounters, you can decide how often to insert scenes without combat. These interludes allow characters to momentarily let their guard down, stop to rest, and reflect upon the adventure. As such, decreasing the number of noncombat breaks keeps the players on their toes as it builds a sense of relentless danger and pressure. A series of caves that are home to kobold trapsmiths could be an unending gauntlet the characters must run through until they reach the end. Or it could feature a number of exploration and roleplaying scenes in which the characters learn about the folk who dwell in the caves, negotiate with some of those folk, and prepare to sneak into the caverns occupied by oppressive forces. You can also consider the pacing when an encounterfilled adventuring day ends. Will the next day feature more of the same? Will you do a fast cut straight to the next combat encounter to keep pressure going, or do the characters get to return home or to a place of rest and refuge? Allowing for slow moments and a return to base provides many opportunities for play, including allowing characters to follow up on personal goals or make the most of downtime activities. CHALLENGE A single encounter can be just as hard as several encounters strung together. But because the game can be swingy, a single encounter might have more variance than a series of encounters, ending up much easier or harder than expected. As such, when planning a single encounter, think through ways to adjust the challenge during play. For example, if you realize that damaging terrain is too effective, you can prompt characters with possible ways to bypass it. If a boss monster foe isn’t dealing enough damage, you can have them become enraged and boost their damage output when they drop below a certain hit point total. When working with multiple encounters in an adventuring day, you typically need to worry less about any particular encounter being easier or harder than expected. Variance in individual encounters usually evens out over time, with characters expending resources on unexpected challenges and saving resources on encounters that go easier than expected. If you find that the characters are having too easy a time and you want resource attrition to be part of the play experience, you can simply increase the challenge of later encounters. “Modifying Monsters Before and During Play” (page 45) has lots of ideas for this. DICTATING RESTS An average adventuring day allows characters to take a number of short rests before ending with a long rest. You can lessen the frequency of rests when needed to create a sense of urgency and use up resources more quickly. You can also add more rests when you want to replenish resources to compensate for heightened challenge. DENYING RESTS Successfully resting, whether the one hour of a short rest or the eight hours of a long rest, requires two conditions. First, the characters must be able to rest without engaging in strenuous activity. Second, the rest period must be uninterrupted. This means that you can reduce or prevent resting by altering either of these conditions in any number of ways. Clear Time Pressure. A volcano’s imminent eruption. Poison gas slowly building up in a cavern. The timing of a ritual. An army’s impending arrival. Upcoming story events such as these can help convince the characters to not take a rest by making it clear that resting will result in failing at their primary goals. A Need to Keep Moving. To stay in one place long enough to rest might be impossible. For example, guards patrolling an area will surely find characters if they stay in one place more than ten minutes (to prevent short rests) or one hour (to prevent long rests). Constant Threats. A location might be unsafe, periodically dealing a small amount of damage to the characters from magic, environmental effects, or the STAY FLEXIBLE Scott notes that some site-based adventure setups can lock a GM into needing to run a full slate of encounters, even if those encounters end up depleting more of the characters’ resources than expected. For example, consider the difference between exploring a haunted ruin and infiltrating an active military outpost. The former can easily allow retreat and respite, but the latter forces the characters to keep going until they accomplish their goals. When designing such scenarios, consider whether the characters might get in over their heads and what changes you can make if they do. In the military outpost scenario, you should be able to easily remove some of your planned encounters, or allow the characters to use distractions or roleplaying to avoid them. 95 DON’T WORRY ABOUT IT Mike often takes a different approach when considering the number of encounters per day—he doesn’t. If you want to experiment with this approach, just let the game play out how the game plays out. Sometimes the characters have good opportunities to take a lot of long rests, such as when they’re traveling vast distances in relative safety. Other times, heroes exploring deep dungeons have few opportunities for a safe respite. Sometimes the characters have all their resources going into a big fight. Sometimes they have hardly any. If the fun of the game is at risk from too many or too few encounters between rests, it’s worth grabbing onto the reins and looking to the advice in this section for managing your adventuring day. But otherwise, don’t be afraid to let things play out how they play out based on the evolving story taking place at the table. attacks of lurking insects. Alternatively, poisonous gas or extreme temperatures might make it impossible for characters to rest. Nightmares and Hauntings. Short rests might be possible in a haunted area, but attempts to take a long rest result in horrid dreams that deny characters the benefits of the rest. Background Disturbances. The constant chittering of insects, the ground shaking due to tremors, the moaning of spirits, and similar disturbances can prevent rest. Likewise, a recurring loud gong in a nearby temple or waves of magical energy washing through an area could interrupt a rest. If the environment denies characters the opportunity to rest, let the players determine this quickly. Heroes who enter a ruined abbey should immediately feel a sense of overwhelming dread telling them they won’t be able to rest even as they explore, creating a sense of urgency. When characters can’t rest, the number of encounters in an adventuring day becomes more impactful, and resources become precious. Even a single encounter per day as a party crosses a haunted wilderness can be a challenge when no long rests are possible. A series of easy- and medium-challenge encounters becomes more exciting and formidable when no short rests are available. ADDITIONAL REST BENEFITS 96 Sometimes it can be useful—or even necessary—to give characters even more rests than normal, by granting the benefit of short or long rests in other ways. When rests are plentiful, characters can face repeated challenges with all or most of their resources available, which can be fun for the players. When providing rest benefits, you can grant characters the full effect of a short or long rest, or create a partial rest effect that replicates a spell or other magic. Usually, the time required to gain these benefits is reduced, even to the point where the characters can gain the benefit during an encounter by making use of a source of power that bestows it. Holy Restoration. Drinking from a healing font, praying at a temple, or receiving a divine gift can all provide a restorative effect. Alchemy. Potions and draughts, ancient elixirs, or alchemical concoctions can allow characters to replenish resources in unusual ways. Alchemy can be a good way to provide alternative types of rejuvenation, from temporary hit points to reproducing the effects of magic potions. Unusual Magic. Arcane equipment, sources of raw eldritch power, or limited-use magic items can all restore characters. As a potential benefit, you can also let characters attune to newfound magic items more quickly than normal (or even instantly), either as a property of those items or a one-time supernatural benefit. Nature’s Gift. Natural sites with an abundance of primal or elemental energy might heal or reinvigorate characters. Meditation or Psionic Restoration. Places or sources of deep mental calm can restore body and mind in minutes rather than hours or days. Safe Place. In a busy or well-trafficked environment, the characters might find a secret door leading to a concealed space where they can rest without interruption. This space might be temporary, or it could allow repeated use. Out of Time. An extradimensional space can allow for time to pass differently, so that a short or long rest can be taken with almost no time passing in the world. Chaos. Elements of chaos magic or wild magic can let characters restore resources, or not expend those resources in the first place. In areas of such magic, casting a spell might not use a spell slot. Or perhaps every critical hit or each fallen foe randomly recharges one of a character’s limited-use class features. In some cases, it can be fun to surprise players and characters with a source of rest or rejuvenation. The characters might feel like they are on their last legs with many dangers still to come, only to find an unexpected way to regain resources. However, when the players benefit from carefully tracking their characters’ resources, it can be better to let them know up front how they can replenish those resources once spent. For example, characters trapped in a dungeon where resting is impossible might quickly realize that each of a set of artifacts they must recover to exit the dungeon also provides the equivalent of a long rest. This mechanic keeps the characters focused on finding the artifacts, while still encouraging them to use their capabilities to the fullest. THE HISTORY OF CHALLENGE In the first comprehensive edition of the Dungeons & Dragons game (the version commonly known as first edition or 1e to those who remember it, though it was in fact the second full version of the game), the ancient red dragon—that greatest of all mortal foes—had 88 hit points and an Armor Class of −1. Those aren’t typos. Yes, Armor Class ran backward in those days. That’s roughly equivalent to AC 21 in 5e. It’s complicated to explain. When we talk about encounter building within the context of the 5e D&D ruleset, we’re discussing a topic that’s been around for almost fifty years, and which has gone through multiple stages of evolution and revision. Each edition of the game had its own rules for how monsters and other enemies were to be stacked up against the player characters, and its own guidelines (or charming lack thereof) that GMs were expected to follow to create challenging encounters. By looking back at the progression of challenge and encounter design, we can see where earlier editions fell short of the modern game—and where we can learn things as GMs from the more laissezfaire approach of earlier gaming generations. TURNING THE TABLES There was no such thing as challenge or CR in first edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. (That name is also complicated to explain.) There were no formulas or checklists for building balanced encounters. There was, in fact, very little consensus on what a balanced encounter even meant, in the sense that we talk about it with the current version of the game. Instead, monsters were broadly organized into ten “level” groups according to their XP value (the number of base experience points a monster was worth if defeated in combat). That XP calculation was in turn based on a monster’s Hit Dice (which were d8s across the board for all creature types and sizes, unlike later editions), hit points, and special features. Monster Hit Dice were also used to compare the relative threat of a group of monsters with the party fighting them, by dividing total Hit Dice by total character levels— but with monsters granted extra virtual Hit Dice for bonus hit points and special attacks. Challenge in 1e was a complicated process, in other words. But even more than that, challenge in 1e was never intended to be a process for selecting monsters to create balanced encounters. The ten tables into which creatures were divided were used for stocking the 1e game’s default multilevel, increased-depth-equals-increased-threat dungeons, where the level of the dungeon below the ground was expected to indicate the level of characters who would find its threat level manageable. Consulting the tables, a GM could see that the minor monsters of Table I were most common on the first to third levels of the dungeon (arbitrarily intended for 1stto 3rd-level characters), more powerful monsters from Table IV were unseen on the first dungeon level and most common on levels five through seven, and so forth. But random encounter tables for wilderness areas paid no attention to monster strength, with creatures there chosen entirely on the basis of fitting the environment and nothing else. NIKKI DAWES TRIAL AND ERROR The second edition of AD&D (commonly called 2e in current parlance) cleaned up and clarified the 1e encounter approach somewhat. But for the most part, encounter building in both those earliest versions of the game was an art, not a science. Through trial and error, while keeping one eye on the tables and the other on monster Hit Dice and special features, a GM would develop a sense of which monsters were a reasonable fit for characters by level. They would then adjust the difficulty of such encounters by adjusting monster numbers relative to the party. But creating encounters against higher- or lower-threat creatures was almost entirely an ad hoc process. Then that process was made even more chaotic by randomly rolling for the number of monsters in an encounter before randomly rolling their hit points, as many GMs did. As such, encounters in the first- and second-edition days often needed to feature things rarely considered by modern GMs accustomed to setting up balanced 97 encounters of specific challenge level (easy, medium, hard, and deadly). GMs of old would thus become deft hands at fitting monsters to the narrative (see “Choosing Monsters Based on the Story” on page 113), and at making sure that combat encounters can be resolved in ways other than a clear win for the characters (talked about in “Exit Strategies” on page 91 and “On Morale and Running Away” on page 125). At the height of second edition, the ancient red dragon received an upgrade to the red great wyrm, and averaged out at 103 hit points with an upgraded AC of −11 (equivalent to AC 31 in the current game). GUIDELINES FOR CHALLENGE Starting in 2000, third edition D&D (no more “Advanced,” 3e to most, divided into 3.0e and 3.5e releases) made big changes to monsters and encounters—and in so doing, laid the framework for encounter-building guidelines whose reflection can be seen in the current game. Across the board, monsters in 3e were tougher than their 1e and 2e counterparts, as 3e design embraced the idea of monsters having ability scores (which they didn’t in earlier editions), and made good use of monsters’ Strength and Constitution modifiers to dial up damage output and hit points. Characters in the 3e game got tougher and more feature-rich as well, but that edition stuck close to the 1e/2e model in combat, with an average fighter still dealing a baseline 1d8 + 4 damage with a longsword, and a fireball spell still smacking down foes with 1d6 damage per caster level. GMs in third edition were the first to make use of challenge rating as a concept and game term, as each foe in the game was assigned a fixed numerical CR based on defenses, attacks, damage output, special features, and other factors. Famously, the 3e core rules didn’t provide any easy way to calculate a GM-created monster’s challenge rating, describing instead an arduous process of eyeballing the monster’s stats against other monsters of a given CR. Challenge rating was used to determine XP rewards for characters defeating a monster of a particular CR, with that reward adjusted depending on how the characters’ level and the monster’s CR compared. More importantly, though, 3e provided formulas and tables in plenty for determining how to create a theoretically balanced encounter for characters of a particular level, using the baseline idea that one monster of CR X was an appropriate challenge for four characters of level X. At the same time, third edition formalized the sense of what “balanced” should mean by breaking out encounters into varying ranks of difficulty, from easy to overpowering. In 3.0e and 3.5e, the apex red dragon remained the red great wyrm, and received an eye-popping update to 660 hit points and an Armor Class of 41. NUMBERS GAME 98 The tactical-focused fourth edition of D&D used dramatically different foundations for monster building and encounter design, making significant departures from third edition. The biggest of those departures was replacing monster challenge rating with monster level, and creating an encounter framework where one creature of level X was considered equivalent to one character of level X. That made building balanced encounters as easy as matching the characters up against equal numbers of same-level foes, using same-level elite and solo monsters to build mini-boss and boss encounters, or using straightforward formulas to build more complex encounters featuring monsters within one or two levels of the characters. The rebuilt challenge paradigm of fourth edition created what was arguably the game’s best encounterbuilding system—at least within the context of the neverending power creep that was the unintended baggage of 4e’s tactical-combat focus. That focus owed much to the broad math underlying the fourth edition game, which used the horizontal scaling of minion, normal, elite, and solo monsters to fill in a roster of foes for each level of challenge. By comparison, the much tighter bounds on 5e monster math can see a creature like an ogre act as a solo monster at the lowest levels of the game, an elite or normal monster at low-to-middle levels, and a minion at anything beyond the middle levels of the game. To wit, the ancient red dragon in 4e once again became the apex draconic foe, and tipped the scales at 1,390 hit points and an Armor Class of 48. BACK TO THE FUTURE The current 5e core rules are a wonderful amalgam of ideas, principles, and feel-of-play from previous editions, all reshaped within a contemporary design space that’s produced the most popular—and arguably the most solid—version of the game yet. Tightening the range of bonuses that can be applied to combat has created a more focused math for determining the challenge of monsters. This means a thankful move away from the 3e and 4e tendency of attack modifiers, hit points, and Armor Class and other defenses to reach mid or high double digits. But at the same time, a more controlled increase of character power across all levels leaves room for the most powerful monsters to still feel forbidding. Looking over the history of challenge, one straightforward conclusion is that whether the game had loose systems or rigid systems, those systems never worked quite as well as their designers intended. Whether it’s the loose Hit Dice gauge of 1e and 2e or a rigid levelbased system like 4e, other factors and the subtle effects of the game’s mechanics can constantly send battles in unexpected directions. The rest of this book offers much advice for building and running encounters for the 5e game, keeping in mind the importance of being able to navigate those unexpected combat course changes. But as a starting point to all that, this section can offer up that the ancient red dragon of 5e has 546 hit points and an Armor Class of 22. Roll for initiative. WHAT ARE CHALLENGE RATINGS? Challenge ratings are a loose guideline with which we can compare monsters to evaluate their power and station, and to compare them to the level of the characters. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of 5e’s challenge rating system can help you build more dynamic encounters and adventures. The concept and intent of a monster’s challenge rating is sometimes difficult to grasp. This comes from one important yet often unspoken aspect of challenge ratings: they don’t compare to anything else. A monster’s challenge rating compares only to the similar challenge rating of other monsters—and this comparison is loose at best. Even with the same challenge rating, creatures often behave very differently in combat. THE LIMITS OF GUIDELINES As set out in the 5e Dungeon Master’s Guide, four characters should be able to defeat a single monster with a challenge rating equal to their level without suffering any deaths. But relating four characters to one foe is hardly a solid comparison, because of the difference in the number of actions the characters and a single foe can make use of. (“Understanding the Action Economy,” page 42, has more information on this topic.) In general, a single monster doesn’t match well against four characters of a level equal to the monster’s challenge rating. The higher level the characters, the worse that match becomes. Further, challenge ratings don’t provide any indication of how well a group of foes matches up against a group of characters. For that, the 5e core rules offer a complicated two-dial system of experience points budgets and multipliers, while other books provide tables to help compare groups of monsters to groups of characters. But there’s one unfortunate truth underlying these approaches: no system does an accurate job. There’s simply too much variance and too many variables to summarize combat with a single calculation. This book includes different sets of loose guidelines to help gauge the combat threat of creatures compared to characters, including “Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” on page 67 and “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” on page 70. Loose guidelines are as good as any advice on this topic can get, given how loose challenge ratings can be when applied to different creatures, and the high variance of difficulty for any given encounter. Since no system of encounter building is particularly accurate, loose systems thus work better than complex ones. COMPARING MONSTERS So if challenge ratings are of limited use in gauging encounters, why do we bother with them? It’s because challenge ratings are still generally useful for comparing one monster to another. They say something about each creature’s place in the world. Giant rats aren’t as dangerous as ghouls, who aren’t as dangerous as ogres, who aren’t as dangerous as fire giants, who aren’t as dangerous as balors. Challenge ratings offer quantifiable numbers that show the overall power hierarchy of creatures and NPCs in the world. They show which foes are weak, which ones are strong, and which are epically dangerous. APPROPRIATE CHALLENGES Challenge ratings also clarify what kinds of threats characters should face given their level. They help define what kinds of problems are worthy of the characters’ attention at different points in their adventuring careers. It’s easy to conclude that 18th-level characters probably shouldn’t be facing giant rats, even as 2nd-level characters shouldn’t be facing frost giants. Character level means something in the story of the game. A 2nd-level party typically handles problems of a local scale. At 7th level, characters are handling regional problems. By 13th level, they handle kingdom-level problems. At 17th level, characters are taking on the problems of the multiverse. And thanks to challenge ratings, we can see what foes are the best general fit for those types of threats, knowing that 3rd-level characters are going to have significant trouble defending a town overtaken by an army of greater demons. In this regard, a monster of a specific challenge rating shows roughly what level of characters are their “equals” from a story perspective—even if knowing that doesn’t help perfectly balance the mechanics of combat. THE WORLD DOESN’T FIT THE LEVEL OF THE CHARACTERS That said, GMs shouldn’t shy away from exposing low-CR monsters to higher-level characters—or vice versa—if doing so makes sense within the context of the story. Bandits are still bandits wherever they might be found, and if 9th-level characters get jumped by such brigands, it’s perfectly acceptable for them to mop the floor with those NPCs—and potentially a lot of fun. (“Running Easy Monsters,” page 124, has thoughts on that topic.) On the other hand, the characters might witness foes far beyond their capabilities—hopefully from a distance. It behooves GMs to telegraph the danger of encounters with too-powerful creatures, so that the characters don’t run in with swords and spells at the ready, only to be quickly destroyed. Likewise, being directly threatened by highCR monsters can take agency away from the players and characters alike, leaving them with few options other than surrender and capitulation. In general, try to avoid forcing encounters with deadly threats just to push the characters in a particular direction—but if doing so makes sense in the larger context of the story and won’t ruin the players’ fun, go with it. 99 WHAT MAKES A GREAT MONSTER? You flip through a monster book, seeking a foe for your next gaming session. But what should you look for? This section is all about breaking down the characteristics that can help identify a great monster. But it can also help guide you when customizing a monster, letting you correct any lackluster aspects—by making use of the guidance found elsewhere in this book—and turning an okay monster into a great one. FUN, ENGAGING, AND MEMORABLE A monster’s presence in an encounter should be fun for both the GM and players, built on exciting features that engage the characters. When a monster is both fun and engaging, the encounter is more likely to be memorable, worth looking back on and retelling over time. FUN TO PREPARE A fun monster feels fun even as you read over their details prior to the game. They have exciting combat or noncombat features that jump off the page, making you look forward to surprising the players. Because of the Shield Bash reaction you created for the knight, you might decide to add a pit to the encounter area, forcing the players to change their characters’ typical tactics to avoid being pushed in. Characters might focus on attacking the knight from range, or drawing them away from the side of the pit. Similarly, observing the rogue using their custom-created Poison Weapon bonus action might inspire the characters to focus fire, trying to defeat the rogue before they can once more add deadly poison to their blade. Great monsters can create different types of engagement. Undead who explode in waves of necrotic energy encourage characters to spread out across the battlefield. A creature who strikes and then goes invisible encourages the characters to locate the creature or ready actions for the foe’s next attack. DISTINGUISHING FEATURES Consider working up a fight against giants. What makes that combat potentially memorable? What features do EXCITING DURING PLAY Consider a hypothetical stat block for an enemy knight, with a Greatsword attack and a high AC to reflect their formidable armor. Although those baseline details fit the concept, they’re not particularly exciting. Now imagine a similar stat block, but the knight can use a reaction to perform a shield bash and push an approaching creature away. That second stat block will likely provide more excitement for the players. Consider another hypothetical stat block meant to represent an NPC rogue, and which features a recharging bonus action to apply poison to a weapon and deal extra poison damage until the end of the rogue’s turn. In addition to its mechanical benefit, that bonus action is something you can roleplay, describing the sickly gleam of poison to make the players understand that this foe just became a greater threat. FACILITATES ENGAGEMENT 100 ALLIE BRIGGS When reviewing creatures, look for features that create obvious interactions with the environment, other creatures, or the characters. The examples of the hypothetical knight and rogue aren’t just potentially exciting—they also create engagement that way. giants have that can provide a foundation for an engaging fight? In general, giants have a lot of hit points, have low AC, and hit hard. But to build on that foundation, you might imagine that a giant can stomp the ground to knock characters prone, or hits so hard that every blow can push a target across the encounter area. Maybe you want your giants to hurl furniture, driving home their incredible size and strength. You can use the table in “Building a Quick Monster” (page 4) to quickly improvise the attack modifier and damage for any new action you want to give a creature, or use one of the common monster powers in that section. “Monster Powers” (page 15) and “Monster Roles” (page 22) have even more powers you can consider, whether to use as is, or to reskin to make a power an even better fit for a specific concept. CONCEPT AND LORE A great monster’s description provides concepts and lore that can inspire you as you design encounters. By grasping the nature of a foe and their place in the world, you can best fit that foe into your campaign plans, making the monster far more than just a set of statistics. For example, you might be planning an encounter in a swamp, and choosing a creature whose lore says they dwell in such locations. So look at how well the creature’s nature reflects this, and how their capabilities reinforce the concept and lore. An amphibious froglike creature with a huge mouth, a grasping tongue, and the ability to swallow prey whole nicely fits a swamp encounter. Likewise, monster lore related to hiding underwater and ambushing creatures as they pass reinforces the concept of your encounter. In addition to ecology, story lore works great to build an encounter concept. For example, many myths and legends talk about hags as creatures of the swamps. So when you decide to make your froglike monstrosity the pet of a green hag who rides that pet through the swamp she rules, the concept really comes together. EASY TO RUN WELL Many encounters work fine with simple monsters, such as when you imagine a group of gnome contract killers stabbing at the heroes. But there are times when you want a more complex monster, such as a malevolent dragon who can take on the whole party. In both cases, though, you want the stat blocks to be easy to run well. So when IN DEFENSE OF THE KNIGHT Scott and Mike both point out that there’s nothing wrong with just loving a creature who hits hard and is simple to run. You can often look to the narrative for other ways to make an encounter engaging (as discussed in “Building Engaging Encounters” on page 76), so don’t forget that narrative can be as powerful a tool as an interesting stat block. BALANCING MONSTER AND ENCOUNTER COMPLEXITY Scott notes that simple monsters can create interesting encounters when paired with great environments, novel tactics, and compelling goals (see “Building Engaging Encounters” on page 76 and “Building Engaging Environments” on page 79). Complex monsters, however, are made to create interesting encounters just by virtue of their features and capabilities. assessing how easily a monster can be run, keep the following points in mind. APPROPRIATE CHALLENGE First and foremost, a monster who runs well is typically one chosen to be a suitable challenge for a specific encounter. “Assessing a Published Encounter” (page 83), “What Are Challenge Ratings?” (page 99), and “Defining Challenge Level” (page 105) all talk about the process of assessing how well a monster can challenge a party. THE RIGHT COMPLEXITY Most foes last 2 to 5 rounds in combat, so they don’t need more than a few actions and features to be interesting. Consider the classic goblin stat block, with one melee and one ranged attack, plus the simple but memorable ability to slip out of combat or easily hide. It’s possible for a monster to be simple to the point where they fail to be interesting. But even then, they might make a perfect choice for followers or minions of more interesting foes. A creature such as a dragon should be more complex, because you want their features and actions to provide you with options you can use in response to the characters. As such, having multiple actions and features lets you fine-tune a combat encounter to create the best challenge. INTUITIVE A great monster does their job intuitively, with just the right number of actions and features for use in combat. In turn, those intuitive actions let you run monsters well, granting a level of confidence that comes from monster features and actions making sense. For example, when a creature can use a bonus action to knock a target prone, you’ll understand that doing so grants that creature advantage on its follow-up melee attack action. A great monster also establishes why they have the features they do, based on the creature’s lore and their place in the world. For example, an agile flying creature might have a flyby attack in combat, letting them attack and move without provoking opportunity attacks, which reflects their normal method of hunting prey. Likewise, a creature resembling a turtle might be able to retreat into their shell, with that defensive response making perfect sense in the context of the creature’s place in the world. 101 READING THE MONSTER STAT BLOCK A stat block is the window through which a GM can understand all of a creature’s intricacies. How does a monster perceive the world and react to threats? What are their capabilities and preferences? Are a creature’s tactics fearsome or lackluster? This section discusses what a stat block can tell you about those things and more. Each section of the standard 5e stat block provides different insights into a creature, helping you better represent that creature tactically and to breathe life into them through roleplaying. If you’re designing an encounter, review monster stat blocks to ensure they work well with the encounter’s theme, goals, and dynamics. And even if you’re using an encounter from a published adventure, you should review monster stat blocks before your game session, giving yourself enough time to make the most of those monsters during play. BROAD STROKES The first two lines of a stat block define a monster at their most basic level, and are the clearest parameters you can share with players. NAME In many cases, a creature’s name can be informative and evocative. A shambling mound. A mummy. A spy. Unless a creature’s name should be unknown, say it aloud often to personify the creature. SIZE AND TYPE Whether humanoid or giant, aberration or fey, monstrosity or undead, a creature’s type helps define how they fit into the world. Likewise, a creature’s size can help you roleplay how they interact with other creatures and the environment. ALIGNMENT 102 Whether alignment plays a big part in your game or not, a creature’s alignment in their stat block can help you understand their moral outlook and how organized and logic-oriented they might be. A lawful creature follows the rules and conventions of their society, works in organized teams, and embraces dependable tactics and planning. A chaotic creature thinks for themself, improvises, easily breaks with social conventions, and might behave arbitrarily. A good creature looks for kindness and compassion in the world, values fair exchanges, and tries to help others. An evil creature seeks personal gain and is largely bereft of compassion. Creatures who are neutral or unaligned are uniformly unpredictable, and often more likely to flee a fight they can’t win than more dogmatic foes. Every creature is an individual, but a creature’s default alignment can help guide how they react to situations, including how likely they are to offer to cease combat and negotiate, or to run away from battle and leave their friends behind. BASELINE STATS Roughly half of most stat block information sits above the Actions section, and contains the baseline details necessary for running a foe in combat. ARMOR CLASS Armor Class tells you how easy it is to break through a creature’s defenses. AC is a function of size, Dexterity, and the toughness of a creature’s armor or hide. A small or quick creature is generally harder to hit than a large or slow creature, except where large creatures are protected by scales or skin that is as tough as metal—or is sometimes actually made of metal. Take a moment to think through what a creature’s Armor Class represents. Does a slow brute plod along and barely bother to dodge? Does a rogue parry and twist away from every blow? Is a villain’s armor nigh impenetrable? Bringing AC to life can be a lot of fun for GMs and players. AC is also important because of how tangibly it impacts the play experience. It influences how often attacks hit or miss, which can feel frustrating or rewarding. High AC tells a story of a mighty combatant capable of outlasting opponents through resilience or cunning. Describing this can help establish expectations and increase the payoff when a character finally lands a blow. HIT POINTS Hit points represent a creature’s health, linearly determining how long a foe can remain in an encounter. They typically represent how physically fit a creature is. The combination of Armor Class and hit points is important, since a foe with both high AC and hit points can last a long time, defining a creature who can wade into the action, take risks, and provoke opportunity attacks without worry. When AC and hit points are low, a creature falls quickly no matter how much damage they dish out, instilling players with confidence. When AC is low and hit points are medium or high, the players feel great while hitting often, but the foe can still endure long enough to make trouble. High AC and low hit points are a wildcard, defining a monster who might last a long time or go down quickly to a few lucky blows. SPEED Speed doesn’t vary tremendously among monsters, but having additional movement types such as flying, climbing, or burrowing can grant tactical advantages, and can be used to surprise players and drive engagement. Take a moment to assess a monster’s traits (see below), as these might interact with speed in the form of special capabilities such as charging, stealth, or teleportation. ABILITY SCORES Ability scores tell the story of a foe’s assets and weaknesses. They help you describe a creature as quick or plodding, hardy or weak, boring or fascinating, uncouth or compelling. Combined with a creature’s proficiencies, ability scores determine the skills that foes feel most confident using, such as Athletics or Stealth. Strength. Strong creatures often engage with the environment and physical challenges. They are more likely to try climbing a cliff to reach an opponent, jump across a pit, or break through a wooden barrier. A weaker creature shies away from such trials, and might avoid the front lines of battle unless they can dart in and out of danger. Dexterity. Dexterous creatures are quick, often acting first in combat, and looking for ways to seize the advantage over stronger foes. They might favor ranged weapons or skirmish tactics, and might bypass challenges by swinging on ropes, dodging out of danger, or hiding. Constitution. A creature with a high Constitution has a strong measure of health and hardiness. They can easily take physical risks and expect to survive, where a more fragile creature will be cautious and seek cover or other ways to improve their chances. Intelligence. Creatures of high Intelligence are often analytical or experienced. They might have studied or faced similar challenges in the past, and are thus able to make good choices regarding future opportunities. Creatures with lower Intelligence might take longer to fully assess their options, and might make mistakes or be fooled easily. Wisdom. A wise creature is aware of their surroundings and can read situations accurately. They understand other creatures and how they behave, with the insight to potentially guide that behavior. An unwise creature misunderstands situations, potentially acting contrary to available information. Charisma. A high Charisma is a boon in directing others and preserving strong bonds. A charismatic creature can keep their allies from fleeing, or help negotiate favorable terms with others. They can be intimidating or manipulative, covering up lies capably. Creatures with low Charisma might try to avoid social interactions or could end up on the defensive in such situations, easily giving away their intentions. SAVING THROWS AND SKILLS Saving throws and skills highlight which abilities a creature uses most confidently. Proficiency in certain saving throws might define how easily a creature throws themself into specific types of peril, while skill proficiencies can determine how a creature acts outside of combat. Because these lines in the stat block can be easy to overlook or forget—and because many creatures don’t have proficient saving throws or skills called out—make note of these things. You might highlight or circle ability scores that are a creature’s best saving throws, or jot down the names of skills that a creature is likely to use, particularly skills that interact with traits or actions. VULNERABILITIES, RESISTANCES, AND IMMUNITIES Beyond their importance in combat, vulnerabilities, resistances, and immunities are also amazing opportunities for encounter and story design. They let you look for ways to bring story to the forefront during combat, highlighting the interaction between the nature of a creature, the characters, and the environment. You can lean into a creature’s weaknesses to make combat easier for the characters, as with a troll marauder fighting in a burning forest. Not only does such a scenario make the troll easier to defeat, you get to explain how the creature came to be there, and to roleplay them appropriately. Resistances and immunities can likewise easily heighten a challenge. For example, in an encounter with a black dragon, you can add acid pools linked by submerged tunnels, providing the dragon with a refuge and the means to surprise the heroes. SENSES If every foe in an encounter has the ability to fight in the dark (whether through darkvision, tremorsense, or other means), that might be an advantage worth incorporating into your encounter design. Tremorsense, truesight, and blindsight defeat most of the ways in which characters can hide. Even a few creatures with special senses can work well in that regard as they provide information to their allies. LANGUAGES It’s important to note whether foes can understand or be understood by the characters. When kobold brigands shout tactics in Draconic and one character understands them, that’s fun! If a giant shouts at the characters and no one understands what they’re saying, it leaves the players to determine whether combat can be avoided. Language differences highlight the importance of spells such as comprehend languages or features such as telepathy. CHALLENGE RATING A creature’s challenge rating (and the XP reward assigned to that challenge) is a rough measure of that creature’s power. By the 5e core rules, a creature of a particular challenge rating should present a medium encounter when fought by four characters whose level is the same as that challenge rating—but there’s a lot more to creating encounters than that simple formula. You can find more on that topic in “Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” (page 67), “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” (page 70), “Building Challenging HighLevel Encounters” (page 86), “What Are Challenge Ratings?” (page 99), and “Defining Challenge Level” (page 105). 103 TRAITS A creature’s traits represent vital features, advantages, and characteristics, all of which are important to review before play begins. Unlike actions, which must be chosen round by round, traits are typically “always on” and thus easy to forget during play. Make special note of traits you expect to come up during play to make them easier to remember. Traits can drive monster behavior and encounter design. A grick’s Stone Camouflage grants advantage on Dexterity (Stealth) checks to hide in rocky terrain, so let that monster make the most of it to set up an ambush encounter. An otyugh’s Limited Telepathy creates an interesting roleplaying encounter if the characters can figure out what the creature wants—or a combat encounter if they can’t. Traits can likewise determine how a creature approaches combat. A tiger uses their Pounce trait whenever possible, as does a minotaur with their Charge trait, because they deal much more damage that way. A wolf ’s use of Pack Tactics provides advantage on attack rolls, causing wolves to instinctively gang up on foes. Whether a monster will risk an opportunity attack to move into position to use a combat-focused trait can depend on their ability to judge risk and choose caution over opportunity, perhaps as indicated by their Wisdom, Intelligence, or alignment. Some traits require careful attention because the moment when they trigger is easy to overlook. Examples include remembering to use a gnoll’s Rampage trait, or determining whether a troll’s Regeneration trait functions on their turn. If possible, avoid using more than a couple of monsters with hard-to-track traits in an encounter. In some stat blocks, spellcasting and innate spellcasting are included in traits, requiring special review. “Running Spellcasting Monsters” (page 58) has a lot more information on this topic. ACTIONS 104 Although some traits can deal damage in their own right, a creature’s primary damage output comes from their actions. Actions are the dynamic means by which a creature engages the characters, challenging and potentially defeating them. The nature of each action provides tactical advantages, as well as a means by which you portray the creature and their threat. In some cases, lore and statistics suggest that certain monsters don’t often experience combat, or that they lack tactical acumen. For such monsters, you don’t need to worry about optimal combat choices, and having foes making obvious mistakes can delight players. Roleplay the creature’s confusion, frustration, or other signs that they lack combat experience. Clever players might try to goad such creatures into making poor choices, creating a fun play experience. For the most part, though, monsters in a fantasy world must periodically face combat in order to survive. For such monsters, their actions represent the tactics they have honed over time, and they use the most favorable of those tactics when possible. Reviewing a stat block’s actions can reveal superior choices to use whenever possible, let you dismiss choices you can ignore, and highlight actions dependent upon other actions or specific situations. For example, a chimera’s Multiattack action allows three attacks, but it almost always makes sense to substitute the higher-damage Fire Breath for one of those attacks whenever it’s available. Whenever an attack imposes a condition that makes subsequent attacks easier, a creature knows instinctively to use that attack first. For example, an otyugh’s Multiattack allows one Bite and two Tentacle attacks, but a hit with a tentacle can restrain an opponent to make them grant advantage, so Tentacle attacks should be used first. Actions with a recharge are almost always superior to actions lacking them, but there can be situational advantages to waiting to use such actions. For example, a dragon who recharges their breath weapon will wait to use it again until they have enough targets lined up. Creatures with spell attacks or complex actions can be hard to run, requiring tactical assessment and comparing damage output to determine the options the creature should naturally favor. For example, a drider can cast faerie fire to help their allies, or can cast darkness to prepare an ambush or escape from battle. They otherwise deal more damage with three Longbow attacks, but should instead use two Longsword attacks and a Bite attack if pressed to melee. This complex creature’s optimal attacks aren’t immediately obvious, however, so reading the stat block carefully is important. PLAY TO YOUR STRENGTHS Encounters typically run better when you play to your own strengths as a GM. If you enjoy discovering a complex monster’s perfect attack sequence, then the time spent reviewing attack options will be rewarding. But if you prefer a simpler game, running complex monsters could result in frustration—so when you review monster stat blocks, choosing the simpler options will be more effective and rewarding. If a published encounter has a complex monster, consider replacing their most complex actions or traits with simpler options, either from another creature stat block or from the range of monster powers presented in this book (in “Building a Quick Monster” on page 4, “Monster Powers” on page 15, or “Monster Roles” on page 22). ROLEPLAYING ACTIONS Actions are the primary way that creatures engage with other creatures in a combat encounter. As such, your monsters will resonate more fully with the players when you bring their actions to life through roleplaying. A drider scout might cast their spells in a hissing voice, or dip their arrows in poison before nocking and loosing them. An otyugh might send telepathic images of food as they attack, revealing their simple goal. “Roleplaying Monsters” on page 48 talks more about this topic. DEFINING CHALLENGE LEVEL As GMs, we all want to design for a specific challenge level at different points. Though we understand that the players and their characters will often surprise us, we want to be able to shape a thrilling final encounter that pushes the heroes to their limits, or a series of easy encounters that let players build confidence. GMs using challenge levels might find that the definitions of challenge in the 5e core rules—the idea of breaking encounters out as easy, medium, hard, or deadly—don’t match their expectations, or that the definitions are unclear. This section can help with that, by discussing the key factors that establish a particular challenge level. Using these criteria, you can then provide an alternative definition of the easy, medium, hard, and deadly challenge levels used for encounter building. are losing even if they actually have the upper hand. A similar effect takes place when characters are rendered unconscious by other means, stunned, paralyzed, or otherwise unable to act, though running out of hit points feels far more dangerous. WHAT DETERMINES CHALLENGE LEVEL? CHALLENGE LEVELS Challenge levels are useful because they can help craft specific experiences for the players. Understanding the factors that differentiate challenge levels can thus help GMs select the right challenge for a particular play experience. The following elements, all related to monster challenge rating, establish the baseline challenge level of an encounter. HITS AND DAMAGE Characters are challenged the more often they are hit by attacks and the more damage they take from those hits. This is true even if the characters are not close to dying. Hits and damage are the easiest key factors to assess before an encounter begins, and also the easiest to adjust during play. RESOURCE EXPENDITURE When the challenge level feels high, players expend their characters’ resources to achieve victory or prevent defeat. Resources include class features or magic items with a specified number of uses, consumable magic items, spell slots, and other limited-use capabilities. Resource expenditure feels important to players, even if they know the encounter is to be followed by a long rest. FORMIDABLE FOES Foes feel formidable when they hit harder than expected, hit more often than usual, have special tricks, control the battlefield, or are particularly well suited to the encounter environment. This often translates to monsters of higher challenge rating, but not always. A fearsome description and great roleplaying can make a foe feel formidable to the players and their characters alike. DYING CHARACTERS When a character is brought to 0 hit points, all the players notice. The tenor of an encounter often changes immediately, creating the feeling that the characters ABILITY TO PRESS ON After the fight ends, do the heroes feel they can continue adventuring and face future encounters? The most challenging encounters erode the confidence of an adventuring party, hastening the point when the characters stop for a short or long rest, and therefore impacting the length of the adventuring day. (“On Encounters per Day” on page 93 talks more about rests and the concept of the adventuring day.) By using these key criteria, you can define each challenge level—easy, medium, hard, or deadly—in a way that replaces the definitions found in the core rules. You can still use your current tools or the core XP-based rules to determine an encounter’s challenge level. But the tips and guidelines found throughout this book will help your encounters meet these new definitions. In particular, “Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” on page 67 has specific guidelines for achieving a hard challenge level with different groups of foes. “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” on page 70 talks about how to avoid a hard challenge level crossing over into deadly. EASY CHALLENGE LEVEL An easy encounter is relaxing and empowering for the players, as their characters show off their capabilities. Because no characters should take significant damage or be in danger, players have the freedom to be creative, trying unusual or inefficient tactics for the sake of roleplaying or fun. IF YOU DON’T USE CHALLENGE LEVELS Mike tends not to aim encounters at particular challenge levels, instead letting the challenge of an encounter shape itself as a result of the story and the pacing of the game. Sometimes that creates an encounter with two half-drunk bandits playing cards in the woods. Sometimes it’s a squad of merregon devils conducting phalanx training. Using the information in “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” (page 70), Mike determines if a battle might be inadvertently deadly after he’s decided on the number and types of creatures to drop into an encounter. This is a less exact but much faster approach to encounter building, which Mike favors. For your own games, try different approaches for designing combat encounters and see which work best for you and your group. Keep all the options in your GM’s toolbox, and use whichever works best for the moment. 105 Use easy encounters as warm-ups, to provide respite or confidence, or in a dungeon or other area that works best with many short encounters. Hits and Damage: Low Resource Expenditure: None Formidable Foes: Stock creatures, dispatched quickly Dying Characters: None Ability to Press On: High. Characters can easily face eight to ten easy encounters in an adventuring day. MEDIUM CHALLENGE LEVEL HARD CHALLENGE LEVEL 106 A hard encounter features one or more formidable foes who can function effectively, hitting reliably and dealing damage that causes characters and players to take notice. Hit point levels can go up and down as healing resources are consumed, driving characters to adjust tactics and expend vital resources to counter the threat. Most of the characters could lose a quarter to half of their hit points as a result of their foes’ high damage output. One or two characters might end up dying and unconscious, and there could be moments when the battle looks like it could go either way, even as the heroes are expected to emerge victorious. Losing the fight is a slim possibility, but the challenge level of the encounter means the characters are likely in a position to negotiate or retreat to avoid dying en masse. After a hard battle, the characters can continue, but might decide to rest if they’ve had previous encounters. Use hard encounters to wake up the players, underscore the stakes and peril in an adventure, deplete resources, or present a strong challenge that the characters will enjoy overcoming. Hits and Damage: High Resource Expenditure: Moderate to high Formidable Foes: One or more Dying Characters: One or two, and several characters might run low on hit points. Character death is possible, though rare. Ability to Press On: Moderate. Characters can face two to three hard encounters in an adventuring day. DEADLY CHALLENGE LEVEL In a deadly encounter, most or all of the foes are formidable, feeling stronger than the characters even if they actually aren’t. They hit often and hard. In addition to damage, higher-CR monsters often have features and other capabilities that add pressure to the encounter. Players should be on the edge of their seats as they carefully consider and reconsider tactics while the battle progresses. Resource expenditure is ongoing, as characters dig deep and use their strongest class features and magic. A deadly encounter is dangerous, but isn’t aiming to be a slaughter or a TPK—a disastrous encounter that ends in a total party kill. Most characters should lose half or more of their hit points in a deadly encounter. Several characters might be temporarily taken out of the fight by conditions or other effects, and there’s a chance for one or more characters to take enough damage to drop to 0 hit points. The pressures of combat might also result in characters dying outright by failing death saving throws, especially from critical hits or taking damage while unconscious and dying. Deadly encounters are particularly challenging when the party is already low on hit points and resources. After a deadly encounter, characters who began the encounter fully rested will typically take a short rest to spend Hit Dice and regain a few resources. Characters who began the encounter without their full hit points or resources usually choose to take a long rest. Use deadly encounters to introduce key foes, surprise players with a thrilling challenge, or provide an exciting conclusion to a gaming session or adventure. Hits and Damage: Very high Resource Expenditure: Very high CARLOS EULEFÍ At the medium challenge level, monsters are of a high enough CR to provide some measure of threat, and one formidable foe could be grouped with weaker foes. The encounter allows for moments when both characters and monsters shine, but the characters are expected to have the upper hand throughout the battle by expending a few resources. Characters are unlikely to drop to 0 hit points, unless they began the battle with fewer than half their normal hit points. Use medium encounters when you want game play to be engaging but not high pressure. After the battle, the characters are left less capable than when they began, but should still be inclined to continue unless previous battles have depleted their resources. Hits and Damage: Average Resource Expenditure: Low Formidable Foes: Stock creatures, dispatched quickly Dying Characters: None, though one in four characters might run low on hit points. Ability to Press On: High. Characters should be able to face four medium encounters in an adventuring day. Formidable Foes: Most or all Dying Characters: Several, with a low-to-moderate chance of character death. Ability to Press On: Moderate. Characters can face one to two deadly encounters in an adventuring day. BEYOND DEADLY? The core rules set an XP value above which an encounter is deadly—and no amount of XP over that line changes the definition. This might seem strange, especially given that neither the core rules nor Forge of Foes use the term “deadly” to mean “everybody dies.” We don’t usually want a high chance of a TPK—a total party kill encounter—in our games. We want the heroes to prevail because that’s fun for the players. A deadly challenge level already feels like high stakes, and going above that risks frustration and the end of a campaign. As such, it can be helpful to have a threshold that warns us when we’re at the upper level of deadly and veering into a TPK. To determine the upper end of a deadly encounter, take the difference between the XP thresholds of the deadly and hard columns in the core rules of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, then add that number to the deadly column. This new number becomes the end of the deadly threshold—meaning that above that number is where a TPK becomes likely. For example, if the hard encounter threshold is 3,000 XP and the deadly threshold is 4,400 XP for a party of four characters, then the upper threshold for deadly would be the difference (4,400 – 3,000 = 1,400) added to the deadly threshold (4,400 + 1,400 = 5,800). This tells you that using creatures in an encounter with a total XP value of 5,800 or higher takes you beyond the deadly threshold and puts you at risk of a TPK. ADDITIONAL FACTORS NOT RELATED TO CR The following factors aren’t directly related to challenge rating or challenge level, and therefore don’t appear in the discussion above. However, these factors are important to also keep in mind, as they can impact how you might need to modify the expected challenge level to make an encounter work as intended. (“The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” on page 70 talks about other considerations that can have an effect on challenge level.) TACTICS Your tactical decisions as a GM impact the challenge. You might make the enemy wizard obvious at the start of combat, or begin with them hidden behind a secret door. You might have monsters attack the rear ranks, forcing melee characters to choose between reinforcing their position and going after the boss ahead. TERRAIN Does reaching an enemy caster require crossing a rickety rope bridge, or swinging across a chasm? Are archers CHALLENGE LEVELS AS ANALYSIS POINTS Scott notes that we can use challenge levels to assess how closely our encounters hit the desired mark, and then adjust our approach accordingly. When you run a medium challenge level encounter, do the benchmarks hold true? This analysis lets you know the relative strength and weakness of the characters—and your style as a GM—compared to the default definition. You can then make adjustments to achieve the desired challenge more consistently. positioned far from the heroes and behind cover? You can easily use terrain to increase challenge level in ways that monster CR fails to capture. GOALS The characters might need to stop the cultists, but also to save a group of captives. A merchant trapped in a burning shop calls for help, distracting a hero from their goal of attacking an evil fire demon. A relic must be recovered before it falls into lava. Having specific goals in an encounter beyond simply defeating the foes increases the challenge level if those goals decrease the emphasis characters can place on combat. USING CHALLENGE LEVELS When you create encounters, use the challenge level that most closely fits your goals for the encounter. If you’re looking for a fun warm-up that shouldn’t use up resources or threaten the characters, then go for an easy challenge level. If the encounter should feature formidable foes dealing maximum damage and pushing the characters to their limits, with high resource expenditure and the chance of characters dropping to 0 hit points or dying outright, that’s a deadly encounter. As you create encounters, you’ll find yourself varying the challenge level to fit the story and to create different emotional responses from your players. This idea lends itself to a number of different approaches for filling out a party’s adventuring day. CLASSIC APPROACH This straightforward method of encounter building tells a satisfying story and has an easy-to-manage linear expenditure of resources. However, players can quickly become too accustomed to this approach. The classic approach features the following setup: • An easy challenge to warm up the characters and provide a fun start. • A set of medium or hard encounters to expend resources. • A deadly challenge as the climactic finish. Examples of the classic approach include: • Entering a cultist hideout to stop the ritual taking place in the final chamber. 107 • Overcoming several wilderness challenges, then facing off against a terrifying monster before reaching a specific destination. • Following leads in the city to find and confront a series of lesser members of the thieves’ guild, before battling the head of the guild. REVERSE APPROACH The reverse approach flips the script to surprise players who expect encounters to become more progressively difficult. Expending resources early on can shake the players’ confidence, though, requiring cues that the characters should press on. The reverse approach features the following setup: • A deadly challenge to start, knocking the characters back and surprising the players. • A set of medium or hard encounters to expend more resources. • An easy challenge to finish things off, allowing the characters to relax and celebrate their success. Examples of the reverse approach include: • Attacking a keep, which results in numerous defenders coming to stop the characters. Once past those defenses, the number of foes drops down to reflect the number of defenders that have been defeated or are unwilling to challenge the characters. • Deadly traps and terrible undead guardians have prevented anyone from making it into an ancient tomb. Once this initial chamber is cleared, the characters can explore the inner chambers, finding that they need only fight a few more undead and solve a relatively simple puzzle to gain the treasure they seek. HILL APPROACH In this approach, challenge is built up, then eased back down. This creates a nice tension, with roughly half the action taking place after vital resources have been spent. The hill approach features the following setup: • Two medium encounters to start, or an easy and a hard encounter. • A deadly challenge to anchor the action. • Medium or easy encounters to finish things off. Examples of the hill approach include: • The characters sneak their way into a keep, steal an item from a trap-and-guardian-filled central chamber, then must flee the site before the defenders are fully alerted. • A trek across the wilderness passes through a central highlight such as a lava field or a vast swamp. That central point offers potentially deadly challenges, but getting there and then getting away are relatively easy. VALLEY APPROACH This approach keeps the characters focused with both a strong start and a strong finish, but provides a respite in between. This style of encounter building works well when you want the middle scenes of an adventure or a 108 THE “ALL-OR-NOTHING” APPROACH Conventional wisdom suggests that if you want to challenge characters, you’ll want to wear them down first. Characters who enter a battle fully rested have a lot of resources at their disposal, and especially if they have the opportunity to use those resources all at once, they’re going to dominate the battle. Sometimes, whether by accident or design, the characters end up facing the boss monster fully rested. They haven’t been worn down first with a series of easy or medium battles, but can push straight toward the big climactic boss fight. When this happens, the hard encounter threshold probably isn’t enough to truly challenge a party. You have to go harder than hard— into the realm of deadly encounters, or even beyond. “Building and Running Boss Monsters” on page 31 talks about running waves of monsters, and that approach works great for an all-or-nothing battle. You can effectively set up the characters facing the easy and medium battles they missed out on—but they face those challenges one right after the other, or maybe even overlapping. Then in the final wave, the big boss and their guardians come out before the characters have any chance to rest. Alternatively, you might set up a seemingly overwhelming encounter, then dial it back by having many of the potential foes in the battle not focused on killing the characters. Some might be busy performing a ritual. They might be in the middle of a big vampire wedding ceremony. They might be getting ready to raid the headquarters of a rival. Even if such a battle is well beyond deadly, the characters can maintain the upper hand by picking and choosing their foes. Sure, things can still go sideways—but that’s where the real fun begins. session to focus less on combat and more on exploration or roleplaying. The valley approach features the following setup: • A deadly or hard encounter to start, ratcheting up the tension. • Two easy encounters, or one medium and one easy encounter, to allow the characters to regain their footing. • A deadly or hard encounter to maximize the tension and drama of the conclusion. Examples of the valley approach include: • Defeating bandits hiding out in ancient ruins is a tough challenge, but makes exploring the ruins easy. Then as night falls, the bandits rise as undead. • Secretly breaking into a bank is a dangerous operation, but once inside, the characters face only minor traps as they explore the vaults. Then when they emerge, they find that the city watch has been called to confront them. • The characters defeat a deadly monster in their lair, explore some low-threat caves at the back of the lair, and return to find that the monster’s enraged partner has just arrived. BALANCING MECHANICS AND STORY Monsters serve two purposes in tabletop RPGs. First, a monster’s stat block includes the rules and mechanics by which a GM can run them in the game—typically during combat, but not always. Secondly, monsters also serve the story of our games. It’s easy to focus on the mechanics of a foe when preparing to run them, but don’t forget the story of that foe. They have things they do mechanically, yes, but each monster also has a representation in the world. They have lore and flavor. Physical descriptions. History, motivations. The sounds they make. The smells … Game mechanics serve the story of each monster, not the other way around. But it’s easy to forget about a monster’s narrative when combat begins. Each creature in a fight moves their speed, makes their attacks, and deals their damage. They react to the characters’ actions, teleport, knock opponents prone, build articulated walls of fire, and so on. With so many rules, it’s no wonder GMs sometimes forget there’s a story going on in the background. It’s a lot to manage, and the more complicated the monster, the easier it is to forget what they’re like in the world. and describe such details each time a monster attacks or a character hits them. You don’t have to flood your description with details for every single monster. But every so often, when it feels right, mention the scar over a brass dragon’s left eye, or the creases in a bandit captain’s well-worn leather boots, or the rusty blade decorated with scalps wielded by a gnome murder cultist. DON’T FORGET THE STORY GMs often fall back on designing or implementing new mechanics when they want to change a monster from their default presentation, and there’s nothing wrong with that. (This book is filled with that sort of advice.) But you can also try changing the in-world description of a monster and their behavior to suit their fictional narrative. Tweak their description. Tweak their behavior. Tweak their history and their reaction to confrontation with the characters. Describe a creature’s unique armor or weapons. Talk about their tattoos or scars. Talk about the holy symbols around their necks. Every foe can be as unique as you’re willing to describe them. When preparing, designing, and running monsters, don’t forget the role they play in the story of your game. First and foremost, every foe is an element of the story taking place at the table. A troll is often (though not always) a big, warty, green-skinned, regenerating giant who’s no stranger to combat. Only within the context of that description does the troll have a set of mechanics—their stat block—to support that story. Use the story of monsters to your advantage. Make foes unique and interesting by their descriptions, their mannerisms, their words, and their actions. A giant rat might be the most boring monster in the game—or could be the most horrific foe ever faced, based on the description a GM uses when that oily-furred, red-eyed horror slithers out of a slimy sewer pipe, screeching as they bare razor-sharp, plague-coated teeth. UNLIMITED NARRATIVE BUDGET The narrative surrounding a monster is limited only by imagination and time. You can describe monsters however you wish. Every ogre warrior’s club can be uniquely carved to show their exploits in combat. Every elf knight’s suit of scale armor can show the details of the battles they fought before. You needn’t change the mechanics of every veteran in a squad to make each of them unique and interesting. The way they wear their armor, the scars across their hardened skin, the style of swords they wield—all these details can change without touching the stat block. You can jot these details down ahead of time if you want, or you can stretch your improvisational skills ASK PLAYERS TO IDENTIFY MONSTROUS TRAITS A GM doesn’t need to be the only one responsible for filling in these details. During combat, you can ask the players to identify interesting physical characteristics of the foes they face. Use these characteristics not only to enrich the flavor of the foe, but to identify them when making attacks, applying damage, or otherwise targeting them. “The ogre bodyguard with the huge scar across their chest” and “the skeleton with the green mohawk” are far more interesting than “ogre number three” and “the skeleton on the left.” MORE THAN MECHANICS WHEN TO CHANGE MECHANICS Alter the mechanics of a monster only when the default stat block doesn’t support the monster’s story in the world. If a troll warlord stands atop a bone-cluttered hill preparing to hurl the skulls of former victims at the characters, the troll stat block has no such ranged attack. So you improvise. Reskin the troll’s Claw attack into a Thrown Skull attack that uses the same attack bonus and deals the same damage, changing that damage from slashing to bludgeoning. Want to make that attack even more dangerous? Increase the damage by another 2d6. Becoming comfortable making such modifications right at the table can help you improvise monsters all throughout your games. “Monster Difficulty Dials” on page 27 offers more advice on making changes to monsters on the fly. Additionally, the Monster Statistics by Challenge Rating table (part of “Building a Quick Monster,” page 4) gives you a set of statistics to improvise new monster mechanics with little to no prep. 109 BUILDING THE STORY TO FIT THE MONSTER In many cases, we can choose monsters to fit the story of our adventures (as discussed in “Choosing Monsters Based on the Story” on page 113). Story matters the most in the long run, so it typically makes sense to start with a larger premise and stock our adventures with monsters who reinforce that story. But there are times when it’s even more fun to do the reverse. We start with monsters who excite us, then we build the story to fit them. MONSTERS FIRST While paging through any of the many monster books available for 5e games, you come across an amazing monster. Filled with excitement, you wish that creature could appear in your campaign. Or maybe a player mentions a type of monster during a game session, saying, “I’ve never fought one of those before!” Or you might have long had an idea for a fun encounter with different types of unusual creatures, but those creatures don’t fit the current locations in the campaign. In these and other similar situations, it makes sense to think about the monsters first and then build a story to validate their presence. VERISIMILITUDE Players have more fun when they can immerse themselves in a world that makes sense. They know that every aspect of the game’s setting is imaginary, but they can suspend that disbelief when it makes sense to do so. As such, it’s important to make monsters and their presence in the game make sense. Start by asking yourself whether a particular monster fits the environment and setting. A monster’s lore often includes rich information on the types of environments they favor, as well as the role they play in such environments. So as fantastic as creatures like water elementals are, they make the most sense when they’re encountered near a lake or other body of water. If you place a water elemental in the middle of a dungeon corridor with no explanation for why they came to be there, the players will likely find that jarring, making them less likely to enjoy the session. You also want to take care when combining different types of monsters, to make sure it makes sense for them to work together. GMs should select monsters for encounters the way a chef selects ingredients: choose a few skirmishers, add a beefy monster to take some hits, and done! But even though a squad of goblins fighting with a water elemental might be tactically sound, that combination will inevitably be jarring in the game. 110 ESTABLISHING CREDIBILITY When choosing monsters first and then selecting the story, you want to find a story that establishes verisimilitude. For some monsters, minor explanations can suffice. Players and their characters will likely believe that brigands have hired a bugbear ranger from a nearby forest. Minor details such as the bugbear wearing a tootight uniform can reinforce this already plausible story. Even the goblins and the water elemental can work, if at the start of the encounter, the goblins are arguing over who should use a magic item. When they see the characters, one of the goblins takes the item and uses it … to cause the water elemental to appear! FISH OUT OF WATER There are times when it can be fun to use monsters who don’t fit the situation, or monsters who shouldn’t be working together. Strange combinations can be surprising and intriguing, as long as you take some care to make the fish-out-of-water scenario plausible. When a monster is a figurative fish out of water, you’ll need to work a bit harder to establish verisimilitude. In this case, you want to explain how the monster came to be in its present environment, and make that a key part of the encounter. Start by asking yourself the following questions: • Where did this creature come from, and how could it have ended up here? • What would it take for this creature to be comfortable in this location? • In what ways is the creature changing or impacting the location? In what ways is the location impacting the creature? • What would this foe need or want to allow them to remain in this location? How could someone else keep the creature here? • How do the answers to the previous questions impact the current story and the other creatures in this location? • What can the characters notice or learn that explains the story of this monster? LORE AND STAT BLOCKS A monster’s stat block tells us a lot about them, as discussed in “Reading the Monster Stat Block” on page 102. Likewise, the lore that accompanies a stat block can provide ideas useful for thinking through a monster’s nature and what their story might be. As an example, wolves fight in packs, and they hunt prey. Their desire for prey could force them into a village. Maybe the first thing the characters see at night is a bush moving. When they investigate, a deer bounds out from shelter. Moments later, the wolves that hunt the deer show up. Kobolds have a reputation for liking traps, so you can showcase their traps up front to foreshadow their presence in a location. You might also leave related clues in the form of notes written in Draconic. You can then set up a fun encounter where kobolds are trying to create or repair a big trap, with the final encounter reinforcing the earlier discoveries and providing confirmation for players who guessed what unseen foes they were facing. Novels and movies can also provide narrative ideas that can be combined with monster lore to set up plausible scenarios for a fish-out-of-water creature. A construct or undead could have escaped from their creator, creating a scenario that works with the expectation that players are familiar with the story of Frankenstein. Depending on how much you borrow from the novel, the players and characters might end up asking who is the true monster and villain in the story. EXAMPLE STORIES Like our larger campaign story, the story we create for our monsters is just a starting point. The real narrative is the one created by the intersection of the characters and that initial tale. A great monster story is therefore one that helps the characters engage with the scene as fully as they can, creating a fun adventure that the players will want to talk about for years to come. This section presents several types of stories that can explain the presence of a monster you want to use in an unusual environment or location. Use any of these setups and the example stories that come with them as is, or use them as starting points that you can alter as needed to fit your own game. SUMMONED, HIRED, OR CAPTURED MATT MORROW A creature who doesn’t fit their environment could have been deliberately brought to that environment. Magic or other threats might bind the creature, or they might serve willingly in exchange for something. Bound Air Demon. An evil sorcerer binds an air demon, convincing the fiend to stay by constructing an area that has tall ceilings, many ledges, and is filled with smoke. The demon can speak of this as they attack, explaining why they deign to serve a mere humanoid. Water Guardian. A water creature could be bound to a fountain, cistern, or moat. The characters might meet an NPC carrying buckets of water, with the scars along their arms a sign of the dangers of reaching into the water. Runes of binding are hidden under the water’s surface, visible to a character who carefully peers over the edge, or could be noticed during battle. Oops, We Hired Swamp Creatures! A group of lizardfolk working as laborers in a village have been hidden away by the merchant who hired them, and have flooded the basement of the merchant’s home trying to make themselves comfortable. When the characters discover them, it’s clear that the lizardfolk are being taken advantage of, and pointing this out could turn the laborers against their employer. Spider Pet. Goblins feed giant spiders in a side tunnel near their lair, and the arachnids no longer attack creatures providing food. In an adjacent cavern, the goblins raise pigs, and are trying to drag one out of a cage to feed the spider when the characters happen by. SURPRISING PLAYERS Scott notes that intentionally using a fish-out-of-water scenario can sometimes work better than making use of monsters who are the perfect fit. Players expect goblins in the goblin tunnels, and might be less engaged when they see still more goblins in a larger cave. However, add another creature who doesn’t seem to belong, and the players become intrigued. They’ll still want to know why the monster is in a strange location, or why two seemingly incompatible creatures are working together, but those questions now tie into the encounter rather than undermining it. 111 BREAK AWAY FROM STEREOTYPES Mike notes that the act of building a story around an out-ofplace monster pushes us away from stereotypical situations. The very act of having to explain the weird occurrence of a creature’s existence forces a GM to come up with a creative explanation that they might never otherwise have come up with. Truly memorable encounters can arise from this process. And That’s Why We Locked Them Up. A prison holds an atypical creature, such as a mephit captured by bandits. The creature’s personality, as well as a possibly secret reason for their captivity, can then become a fun part of the adventure. Is the creature a potential ally and source of information, or a potential foe biding their time before they turn against the heroes? Are they especially obnoxious, or incessantly obsequious? Do they lie all too convincingly, then quickly turn against any ally or enemy who believes them? Another option is to have a captured creature seem mundane when they’re actually far more dangerous. That dog held captive in the crate? It’s a hell hound or death dog. The trophy case displaying two crossed swords? Those are flying swords. And of course, the empty cell holding nothing but a mundane-looking object might be a mimic, a cloaker, or a creature not normally known for camouflage fallen victim to a magical curse. MINI-BIOME A broader location might contain a small area where an out-of-place monster fits in, even when the rest of the location is not a typical lair. Magic can always be used to explain a mini-biome, though this might feel forced or trite. A more natural reason for a mini-biome usually works best. Localized Swamp. Lizardfolk and their pet giant frog dwell in a cavern where an underground river has eroded the rock, creating swamplike conditions. Brackish Waters. A sea creature is attacking settlements along a freshwater river. A village elder tells the characters that during heavy rains, the sea floods the estuary and the waters turn brackish, explaining how a marine predator has found a new home. There Must Be a Volcano. A biome can sometimes be foreshadowed. Setting up the appearance of a fire elemental and magma mephits in a dungeon can be accomplished by first creating a chamber where crude drawings of volcanoes and fire creatures cover the walls. When the characters later come across a river of magma, the presence of fire creatures makes sense. ON A MISSION Sapient monsters might intentionally travel to an unfamiliar location, becoming explorers just like the characters. The reason for the monsters being there can be just as interesting as the monsters themselves. 112 Give Us the Artifact! A band of drow seek a rumored artifact or lost lore. Their mission is vital, so they might negotiate with the characters to gain what they seek—or fight the characters if their mission is opposed. Meet the Neighbors. A group of creatures who would normally be more at home on a different dungeon level or in an adjacent biome have come to the area the characters are exploring with some purpose in mind. They might be meeting up with other creatures to establish an alliance, trying to claim (or reclaim) a valuable relic, or simply seeking conflict for its own sake. The appearance of such creatures can add richness to an encounter, even as it sets up new regions or dungeon levels the characters haven’t yet visited. What Dug This Hole? A burrowing creature has broken into a dungeon or city basement, seeking or escaping something. The broken wall or floor explains how the creature came to trade its former environment for a new one. A STORY WITHIN A STORY We can make the presence of a monster believable by telling that creature’s story and explaining how that telling fits into our larger story. Though discovering an explanation for a monster’s presence after the monster has been encountered sometimes works, providing at least a partial explanation up front can make the actual moment of meeting the monster feel more plausible. Inventor Lost Control. To make use of some awesome clockwork monsters within a larger dungeon, you can place a door barred from the inside with a “Keep Closed” warning sign. The door leads to a mini-lair for a gnome inventor. The first of three rooms holds her notes, indicating that her clockwork creations have gone out of control. The second and third rooms contain the aggressive creatures, and the third room also has the bound inventor. If freed, she can help turn the tide of battle. Long Cold Winter. You can establish that it’s been an unusually harsh winter in town, and that the townsfolk are afraid. This sets the players and characters up nicely for a yeti attack, which seems entirely plausible. They Have Eyepatches and Say Yar. To make use of some great bandit-type stat blocks while the characters are in a port town, simply reskin them as pirates. For extra fun, place wanted posters for the pirate captain that the characters can find before the encounter. They Scuttled Off That Way. A remorhaz is a fun monstrosity, but doesn’t quite fit a dungeon milieu. So set up a scene where the characters can overhear two ogres by a fire in a cave, talking about how a rock broke open and something nasty came out. Investigating the fire pit shows that some of the rocks around it appear to have cracked open like eggs. Later, the characters can encounter a young remorhaz—perhaps chewing on the remains of another dungeon denizen the predator surprised. CHOOSING MONSTERS BASED ON THE STORY Rather than building combat encounters based on the level of the characters and the difficulty of the intended challenge, consider choosing monsters for your adventure based on the story and the situation in the world around the encounter. This idea isn’t always easy to understand, and it departs from a common approach toward preparation for fantasy RPGs—building adventures as a set of encapsulated and predefined scenes or encounters, with a bit of exploration, some roleplaying, and (usually) a lot of combat. As an alternative, write down a list of the monsters who might be encountered in a larger area depending on the situation taking place during the game. The seventh step of preparation from chapter 9 of Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master describes how to abstract lists of monsters from the scenes and situations in which they might appear during an adventure. This lets GMs “cook at the table,” dropping in monsters who fit both the scene and the situation—and which make for the most fun in the moment as the GM improvises encounters based on what happens during the story and the game. other monster books available for fifth edition fantasy games offer excellent summaries of each of their creatures, including lore, environment, behaviors, and allies. When considering monsters to add to your adventure, start first with your favorite book of monsters. Many monster books and guides for Gamemasters include lists of monsters by ecology, often sorted by challenge rating. These lists show what monsters typically reside in which environments, including forests, deserts, ruins, cities, and more. The challenge ratings in such lists are useful guides, but don’t be afraid to include weaker monsters to let higher-powered characters show off their skills. Likewise, you might choose a monster who’s technically too powerful for the characters, but you can give them a chance to see the creature from afar so they don’t simply wander in and get killed. (“Bosses and Minions” on page 61 offers suggestions on which monsters might serve more powerful creatures, all keyed to environment. “Monsters by Adventure Location” on page 72 features lists of monsters keyed to specific locations.) UNDERSTANDING THE STORY REALISM AND FUN Which monsters make sense given a particular story, situation, and location isn’t always clear. We must first understand the story of our adventure, which we can do by asking the following questions: • Where does it take place? • Who would inhabit this location? • What types of allies, followers, or symbiotic relationships exist alongside these primary inhabitants? • In what numbers do these inhabitants typically gather? • Do they wander alone? Do they travel in pairs or groups? As an example, red dragons are usually solitary creatures as regards living among other dragons—but they could certainly have allies. Some might have fire elementals who serve them unerringly, or hordes of kobold worshipers to do their daily menial work. They might have sworn knights or priests who serve them on far-reaching quests, or who protect the dragon as bodyguards and advisors. A particularly powerful red dragon spellcaster might summon and bind a demon to their service—a demon eager for a chance to break their bonds. When considering what monsters might inhabit the locations of our adventures and in what numbers, consider the issue from two angles. What makes sense in relation to the fiction and location of the world? And what best entertains your players? Instead of balancing both ideas at the same time, though, consider focusing on realism first. What makes sense for the fiction of the game? If the characters delve into the ruins of an ancient crypt, all sorts of undead come to mind, including skeletons, specters, wights, wraiths, ghosts, mummies, vampires, and liches. But many other types of foes might also work in such a location, including cultists, necromancers, graverobbing bandits, or black puddings feasting on the flesh of the dead. Any such creatures can easily feel realistic given the location. So when preparing a game set in a crypt, list the various undead and other monsters who might show up in an encounter. Then when running the game, choose the type and number of monsters that feels like the best fit for the fun and pacing of the game. Since the inhabitants of a location can move around, you can decide what quantities and combinations of monsters might reside in or travel through any given area moment by moment. Did the party just finish a big battle with hard monsters? Maybe it’s time for a couple of weaklings to wander through. Have the characters been having an easy time so far? Maybe they stumble into a group of heavy hitters. Either scenario still makes sense given the larger story and situation, but you can choose UNDERSTANDING THE MONSTERS It always helps to have a deeper understanding of the lore behind monsters, whatever its original source. You might seek out this lore from old folktales and stories from thousands of years ago. You might take monsters from popular fiction. The D&D Monster Manual and the many 113 the scenario offering the right beat and the right element of pacing for the game. Such variability helps tremendously in pacing a game. You don’t ever have to throw your hands up and run an encounter as is, just because it’s written that way. By choosing the number and types of monsters, you can easily tweak encounters toward what brings the right pacing and feeling to the overall game. WHAT ABOUT ENCOUNTER BALANCE? If we’re choosing monsters strictly by what makes sense for the scene, location, and situation, then improvising the number and combination of monsters during play, how do we ensure encounters are balanced? There’s one simple answer: We don’t. “Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” (page 67) offers guidelines for building groups of monsters to challenge characters. But a story-focused approach toward encounters means not worrying about encounter balance. Instead, you can focus only on being aware of when an encounter might become inadvertently deadly, discussed in “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” on page 70. CHOOSING TOKENS AND MINIATURES Whether you play in person or online, this free-flowing way of choosing monsters might challenge you if you make extensive use of tokens or miniatures. However, there are a few easy ways to make sure you can still use those tools even while running flexible, story-based encounters. SELECT A SUBSET OF TOKENS OR MINIATURES If you know you’re going to be running an adventure in a crypt and you have an idea of the types and numbers of monsters who dwell there, you can sift through your collection and set aside the tokens or miniatures you might need. This can be a little time consuming, and you might not use every mini you pull out. But having them all on hand means you can pick what you need when you need it. For online play, you don’t have to worry about the number of tokens—just the style. You can keep a separate folder with the tokens you think you might make use of given the scenario, then copy and paste as many of those tokens as you need. USE GENERIC TOKENS A set of generic tokens is a fantastic lazy tool for online or in-person play. A generic token is either a physical or digital token with an abstract representation of various types of monsters, rather than specific art for only one 114 type of monster. These abstractions might include a skull, a grim-looking humanoid, a wolf, a slime, a dragon, or any other general representation of creatures in the game. Numerous examples of generic tokens can be found online, which can be purchased or constructed at low cost. Some virtual tabletops even include generic monster tokens built in. For others, you might have to import the tokens into your VTT, but having a set of generic tokens on hand means never needing to worry about having the exact right token at the exact right time. ORGANIZE FOR EASY RETRIEVAL When you organize your tokens or miniatures, either inperson or online, spend the time to organize them so you can easily find the ones you need when you need them. Find the right categories that make it easier to dig out the right ones. Keep your most-used tokens or miniatures close at hand, and let your least-used tokens or miniatures fall to the bottom of your organizational system. FIND A FAST METHOD FOR ONLINE TOKENS A number of online tools let you build a token from any image quickly and easily. Some virtual tabletops have built-in token making software. Find these tools and practice using them to quickly build tokens from the many monster images made available for purchase or free download online. Get good and fast at this process, and you’ll be able to build any monster token you need even in the middle of your game. CRAFT GENERIC TOKENS FOR IN-PERSON PLAY For playing in person, you can build a set of generic tokens with a little bit of crafting. Start by printing out black-and-white silhouettes of monsters, skeletons, knights, and other images. Search for royalty-free game icons online. Pick the ones you like and print them out at just under one inch in size. Then punch them out with a one-inch hole punch. Use one-inch magnets for the base of the token and one-inch clear epoxy stickers for the top. You can put together a couple of dozen such tokens for under $20. BUILD SITUATIONS AND SEE WHAT HAPPENS By abstracting monsters from encounters and choosing monsters who fit the scenes, story, locations, and situations in your adventures, you give yourself the freedom to let those adventures follow whatever directions they might take in the game. Keep these tools and guidelines in mind to help you facilitate the adventure—moving where the action takes you, and freely adjusting the pace to fit the fun of the table. ROMANCING MONSTERS It can happen in any campaign. Everybody’s focused on the endgame, dispensing with foes on every side, digging in deep to uncover ancient lore, and unraveling dire mysteries layer by layer. And then the player of the warlock says: “Hey. What if instead of trying to defeat the Shadow Sovereign and their Legions of Umbral Anguish, I just … you know … turn on the charm?” Whether it starts as a simple jest around the table at the end of a very late night, an ironic attempt at Twilight actual-play fan fiction, an homage to all the players’ favorite anime, or some other slow-burning urge, many campaigns come to the crossroads that is romancing the big bad. Whether that big bad is a feral monster, a wicked villain, a capricious deity, a malevolent antihero, or worse (which is to say, better), the characters’ ultimate goal of fiercely taking down their foe can suddenly remake itself as the new goal of … well, fiercely taking down their foe. If you catch the drift. Romancing monsters and villains is a trope that’s existed in human-told tales for millennia. It can be great fun if it fits the story your game is telling and the narrative sensibilities of the players. (Letting the game move in this direction also inevitably brings the roleplaying side of things into sharp focus, discussed in “Roleplaying Monsters” on page 48). But there are a few things to think about before taking your game to the delicious dark side. storyline should be treated as narrative kryptonite. People sometimes talk about how there’s no wrong way to play the game, but in fact, there are many, many wrong ways to play the game. And invoking or alluding in any way to nonconsensual encounters of a romantic or passionate nature is one of the worst. CONSENT Wait, didn’t we already do this? Yes we did. But consent is such an important part of this topic that talking about it once isn’t enough. This time, though, we’re talking about player consent. Because even for a romancing-the-monster story that involves appropriate consent within the narrative, it’s important to recognize that this might not be a type of story all players want to engage in. Many players love a campaign that strays into romance-and-relationship side treks, whether between player characters, characters and NPCs, characters and emissaries from the Court of the Shadow Fey doomed to never find true love, or what have you. But lots of players find those topics uncomfortable when they engage them in games, even if they have no problem with them in other fictions. And it’s important to respect that. If a full-on villain romance is something that feels like it might come up in a campaign, GMs should make discussing that topic part of their session 0. If it comes JACKIE MUSTO CONSENT Any narrative form—prose fiction, film or video, video game cut-scene, or tabletop roleplaying scenario—can veer toward romantic interactions between characters and all the things that can result from that. When this happens, showing consent within that narrative framework is the all-important first point in any checklist of tropes and narrative elements feeding the story. Always. There’s perhaps no more archetypal moment in a story revolving around an enemies-to-lovers reversal than the villain and their heroic foil fighting toe to toe, matching each other’s ferocity, pressing each other closer and closer in combat—and then having one or the other plant a physical or metaphorical kiss on their astonished foe. It’s a great scene. But no matter how innocent it seems, don’t ever confuse that momentary transition of violence into romance with a scenario in which romance is earned through violence, threats, or an imbalance of power. Especially in a roleplaying game, where our engagement with the story as the players creating it is so much stronger than as viewers or readers passively engaging with a book or film, the loss of agency for any character in a romantic 115 CAN’T WE JUST BE FRIENDS? Mike points out that even if romancing the monsters isn’t your thing (and especially if that kind of roleplaying isn’t a good fit for any member of your group), a lot of the issues discussed here work perfectly well for creating an enemies-to-friends scenario. Fiction, movies, and comics are full of examples of this sort of story, because that narrative packs a lot of punch. Think of the number of times in comics that villains have reversed away from their initial motivations to take a heroic turn (Bucky Barnes, Harley Quinn, and many more), or villains and heroes have found common ground to fight a mutual foe (one of the constant themes touched on by the X-Men comics and films). up without forethought or planning during a campaign, use your safety tools to take a pause in the game (whether during a session or as a conversation between sessions) to ask how that type of story fits with each player’s lines and veils. (You can get more information on RPG safety tools, including lines and veils, in The Lazy DM’s Companion, and many places online.) Remember that this conversation includes the GM as well. A group of players dead set on having the bard seduce the Three-Tongued Death King should make sure that the GM is happy to run that particular scenario, and should ask whether that GM has any lines and veils of their own regarding that type of subject matter. ENEMIES TO LOVERS Part of the reason that so many games and campaigns can move in the direction of characters romancing their enemies is that characters romancing their enemies is a storytelling tradition as old as storytelling itself. The myths of Ancient Greece familiar to a great many fantasy fans are chock-full of such stories—though many are extremely problematic in their handling of character agency (to put it mildly) and should be approached with care if you’re looking to them for inspiration. Shakespeare did a much better job with Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing, Romeo and Juliet in that eponymous play, and other works. (Still, though: content warning for those plays falling far short of being feminist classics.) Even better was Jane Austen setting the bar for the enemies-to-lovers trope with Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy in Pride and Prejudice. And more recently, one can look to Daphne and the Duke of Hastings in the Bridgerton Netflix series and books, Ygritte and Jon Snow from the Song of Ice and Fire books, Satan and Emilia from the anime The Devil Is a Part-Timer!—and of course, Han Solo and Princess Leia in The Empire Strikes Back, with the frisson of adversarial tension carried between all those characters creating a narrative foundation that turns unlikely romance into compelling character story. LEVELS OF CONFLICT The power of the enemies-to-lovers trope lies in the way it upends the expectation for the conflict that drives the 116 narrative. In the simplest terms of story analysis, character versus character is one of the foundational forms of dramatic tension and conflict, and is unsurprisingly the conflict linchpin in tales of fighting monsters. As such, stories built around battle and struggles for interpersonal domination fit perfectly into the combat-focused narrative framework of a fantasy roleplaying game. But at a level above the straightforward narrative tension of character versus character, the dramatic paradigm of character versus themself offers a more complex conflict framework. Essentially, a story built around the idea of a character fighting against their own instincts and nature implicitly raises the question of how the character can ever possibly win that battle. As such, whichever character in the enemies-to-lovers scenario is the one most surprised by the sudden turn of romantic events ends up in a much more dramatically interesting place, as the question of how to handle their enemy becomes increasingly complicated. THE COURSE OF TRUE LOVE A character’s attempt to romance a villain might start out as a ruse, intended to distract or confuse that foe, or to allow the character to get close enough to the villain to learn vital information. In a similar vein, a villain characterized as a cold, calculating despot might view caring for others as a fatal weakness—making their longignored ability to feel emotion into a flaw the characters decide to exploit. But in the course of what initially feels like contrived romantic attraction, a character might learn that their enemy is more than what they first appeared to be—or is perhaps even worthy of redemption. So if the character’s false overtures are met with real emotion, real romance, and a chance to turn the foe away from their villainous path, what should they and their compatriots do? BAD BARGAIN Another angle that can play into a romancing-themonster scenario arises from the realization that both sides in that scenario can continue to have their own adversarial objectives even as the romance blooms. A player character who ends up drawn to the idea of romancing a villainous foe might initially do so with a particular goal in mind, even if that goal is just the baseline idea of not wanting to kill or incarcerate the villain in the normal way of things. However, in the course of roleplaying the scenario, the character and their allied party members might discover that the foe has goals of their own for the romance— perhaps including objectives the characters have a hard time accepting. This sort of setup can lend itself to strong roleplaying opportunities wrapped around all kinds of moral dilemmas, as the characters must decide whether having an enemy become a lover creates more problems than it solves. THERE BE MONSTERS The rest of Forge of Foes is filled with all kinds of guidance for making monsters feel unique and memorable in your games. But most of that advice is built around the idea of adding on to a preexisting monster concept in some way. Whether you’re starting with an existing stat block and customizing it, or crunching the numbers underlying monster design to create the most effective attacks and traits, fine-tuning a known creature is a great way to match that creature to the fit and feel of your game. But what about creating new monsters from whole cloth, or thinking about reskinning a monster not with new stats and attacks but with a new story? Within the world of the 5e game, with all its infinite fantasy possibilities, how do you come up with ideas for new monsters in the first place? THE OLD TALES The lists of monsters assembled for the earliest editions of Dungeons & Dragons are an odd grab bag of creatures from European myth and folk tales, sprinkled through with equally fantastic creatures borrowed (usually with no acknowledgment, and often in problematic ways) from other cultures. For years, many fantasy RPG players have learned of the wiles of minotaurs, wyverns, harpies, and the tarrasque at the gaming table, long before discovering the centuries-old tales in which those creatures first appeared—and learning how drastically the game lore for many monsters deviates from its classical roots. Just as the designers of the monsters in the earliest fantasy RPG rulebooks and periodicals did, you can create monsters from the fantasy stories that define your own personal journey through the genre. Were you awestruck by the sandworms of Dune? Pleasantly creeped out by the Children of the Forest in the Song of Ice and Fire novels and Game of Thrones? Overwhelmed by the towering beasts in Shadow of the Colossus? Creatures from books, movies, TV, streaming shows, video games, comics, and other entertainments are ripe for rebuilding as part of your own games and campaigns. You might want to perfectly clone a tabletop version of a favorite fictional or video game foe, pick and choose bits of lore as a starting point, or take any option in between. ROOTS IN STORY The most memorable monsters are often those whose inspiration doesn’t come first from cool attacks and other game mechanics, but from a creature’s place within the story of your game and campaign. The way that the interplay between players and GM, the characters and the game world, shapes a communal narrative stands at the heart of the unique experience of tabletop RPGs. So when thinking about a new monster, think about the place that monster might occupy in your story—physically, mythically, and thematically. Think about how you want the characters to feel when they first hear about the threat a monster presents. Think about how you want them to respond to rumors and evidence of the creature’s plots and attacks, and of the reaction you hope to see when they finally face the foe in combat. Then give thought to what mechanics can support that sense of the monster’s story. RUMORS AND WHISPERS Even as you draw inspiration from the story your game will tell, you can also think about the stories told within your game. How do the NPCs of your campaign or game world speak about the monster you’re creating? What tales do they tell about the creature’s depredations or reputation for evil? Have they grown up hearing legends of the monster from an early age? Do heralds or other minions appear as a warning of the monster’s own imminent arrival? What warnings do people give their children when rumors begin to spread that the creature you’re creating prowls among them? One great way to tap into this internal sense of story is to create short pieces of flash fiction for your campaign—a few hundred words written in character by specific or unnamed NPCs. You might eventually share your writing with your players, as part of setting the tone for the kind of story you want your monster to tell. But even if you don’t, the act of writing such fiction can help clarify the sense of the monster’s existence, helping bring them to life in your mind as you bring them to life in the world. MONSTER AS PUZZLE The nature of the stories surrounding many classic realworld monsters involve puzzles that people can solve to help deal with the monster. In some European folkloric traditions (not to mention Sesame Street), vampires are compelled to count grains or seeds spilled upon the ground, preventing them from wreaking havoc. A sphinx is a deadly guardian capable of destroying all trespassers—except for those who answer a challenging riddle. The original basilisk of Pliny the Elder was said to be fatally weakened by the odor of a common weasel. Creating a puzzle or a secret for a monster is a great story hook, revealing a creature’s vulnerabilities and providing the characters with a tangible reward as they gain some measure of control over the monster. UNIVERSAL FEARS Many monsters of myth and legend originated in the primal fears that kept our forebears huddled together in the dark of night or around the evolutionary leap forward that was the campfire. Even today, we often gravitate toward fiction—fantasy or otherwise—with antagonists who tap into those archetypal terrors. So when thinking about new monsters, you can keep in mind any of the following fundamental human(oid) fears as an origin point. (Content warning: As indicated by their titles, some of the following examples deal with themes that might be upsetting.) 117 MODERN FOLKLORE Mike notes how the history of D&D and its monsters often connects to old folktales and lore, but points out that players and GMs today are all swimming in our own modern folklore. Movies, TV shows, books and comics, video games—all these entertainments can flood our minds with ideas for cool monsters to drop into our games. And as a bonus, many recent fictional works break away from the typical Eurocentric and male-dominated forms of fiction and lore that inspired many of the traditional monsters of D&D. As GMs, we can take our inspiration from all around us, including traditional folklore, modern fiction, real-world history, and current events. And when we do, we can easily combine inspiration to create a wholly new approach. Vampire folklore goes back thousands of years, and yet we continually come up with new takes on those awesome creatures. Spacefaring vampires, good-guy vampires, vampire gunslingers, vampire governments—there’s no end to the mash-ups. So whether you’re diving back into lore from two thousand years ago or the latest episode of your favorite TV or online series, take your ideas from everywhere and use them to build the coolest monsters your players have ever seen. DEATH AS THE END A fear of death is well understood and shared by most people. But that fear changes within the context of a game in which the more powerful the characters, the more likely they can treat death less as a final end to the journey of life, and more as a momentary detour to be overcome with magic and heirloom jewelry. As such, monsters in the game who have the ability to kill characters permanently, leaving no chance of being raised or resurrected, pack a powerful punch that can let the characters truly share in the fear of death their players understand. BEING EATEN ALIVE One of the most horrific understandings that comes of observing nature in all its splendor and glory is the idea of how many animals come to their end inside other animals, consumed while still conscious, their last terrified awareness focused on their own inescapable demise. Monsters who have attacks allowing them to engulf characters or swallow them whole hit that primal fear hard, and can create truly horrific moments in a campaign. BLOOD AND LIFE 118 Even before humans began to collate the earliest concepts of medicine and physiology, blood was seen as a precious commodity linked inextricably to the power of life. Creatures who drink blood have long been a mainstay of folklore, including vampires, demons, and evil spirits whose tales of exsanguination have existed since antiquity and can be found in countless cultures. In a game in which a character’s combat health is measured in hit points, a monster who drains blood or steals life force in other ways—reducing a character’s hit point maximum, reducing their Strength, and so forth—makes a formidable threat, with heroes forced to watch helplessly as their vitality and essence is drained away. LOSS OF IDENTITY The fear of being replaced and having one’s life taken over by another creature, whether evil shapeshifter or capricious changeling, is deeply connected to psychology and the concept of ego. This fear can work in two directions, causing characters to dread the thought of another creature stealing the thoughts, memories, and appearance that define them—as well as creating paranoia in those characters if they have reason to believe that a loved one or ally has already succumbed to that fate. LOSS OF AUTONOMY Losing one’s personal autonomy by succumbing to physical or mental helplessness, or by having the ability to make choices taken away, is a powerful fear for many people. As such, monsters who can shut down a character’s physical responses by immobilizing them, wreck their mental faculties by making it impossible to reason or assess the world, or take away their ability to act through mind control make powerful foes. Such creatures must be handled carefully, however, given the importance of character agency to the game. Character agency is the idea that players should always be able to make free, meaningful choices for their characters, and taking away those choices can drastically undermine the fun of a game. This fear is thus one that can frustrate and anger players almost as much as it frustrates and angers their characters. When monsters establish the kind of control that takes away a character’s purpose, it’s good to keep that control short term, and to give characters plenty of chances to break that control. If you ever find that repeated saving throws or the other regular mechanics of the game aren’t enough, you can think about options such as letting a character choose to take 1d8 psychic damage per two levels to end charm or domination effects. You can also have a monster control only some of a character’s actions, leaving the character free to act independently some of the time. TALK TO THE PLAYERS When thinking about these or any other personal fears as grist for your campaign story mill, it’s a great idea to talk to your players in a session 0 or an in-game checkin to make sure the fear you want to make use of isn’t something one or more players will find problematic. (Information on using safety tools in your game can be found in The Lazy DM’s Companion, and many places online.) Additionally, one universal fear to be wary of is the fear of “the other” that lies at the root of many myths and legends of the real world, and which has long fed imperialist and colonialist narratives. “Anticolonial Play” on page 119 has some thoughts on that particular trope and how to avoid having it undercut your game. ANTICOLONIAL PLAY In any family tree tracing out the evolution of modern fantasy roleplaying games, the apex of that hierarchy isn’t a roleplaying game at all. Tabletop miniature war gaming was the forebear of fantasy roleplaying in its earliest forms. In fact, the primal edition of the Dungeons & Dragons game made the explicit assumption that new players were already war gamers, able to automatically understand the lexicon and context of those games. Some fifty years later, D&D and other 5e fantasy games would be all but unrecognizable to the players of the game in its first war game-adjacent incarnation. But despite that, the DNA of all the editions that led to 5e still lingers in the game’s rules and its worldview. And that worldview holds a starkly colonialist view of the relationships between the game’s heroes and too many of the other sapient peoples—humanoids and other creatures with intelligence, awareness, language, and culture—who often play the part of the game’s foes. The ongoing legacy of colonialism is the foundation of a great deal of what’s wrong with the world—and a book like this is clearly not the venue to try to fix what’s wrong with the world. However, as gamers, we can, should, and must think about how our experience of the real world feeds into the worlds we create together. We need to understand the ways in which the traditions of colonialism hardwired into common culture and media can easily make us embrace potentially hurtful ideas even without meaning to. A PROBLEM WORTH FIXING The topic of colonialism in fantasy gaming deserves far more discussion than our little monster book can bring to bear. The sidebars in this section dig in just a bit to the starting points of colonialist thought and its pervasiveness in the real world. But even those brief discussions aren’t the actual point of us wanting to talk about an anticolonial approach to monsters in Forge of Foes. We want to have this discussion because being aware of and rejecting colonialist ideals in our fantasy roleplaying games makes those games better. Because the more interesting you make the peoples and sapient creatures of your world and their place in that world, the more interesting your story. It’s easy to say, “D&D is just a game. What does it matter?” But there’s actually a good answer to that rhetorical question, because the harm that colonialism does in games can ruin the fun for players with real-world stakes in the problem. And in the end, building better stories with the help of a new perspective doesn’t take any more effort than building the same old stories that fantasy gaming has been working with for the past fifty years. A CHECKLIST FOR BETTER STORIES The point of this section isn’t to figure out how to fix colonialist thinking in the real world, as much as we’d all like to. It’s about acknowledging how the harmful roots of that worldview (talked about in the “Colonialism: The Short Version” sidebar) have long been a part of fantasy roleplaying, and the ongoing problems created by a pervasive “it’s just a game” moral setup in RPGs (talked about in the “Othering” sidebar on the next page). Those deep historical faults at the heart of the games we love make for tired, derivative storytelling. But by keeping a handful of course corrections in mind, we can move away from those old faults as we build better game worlds: • Avoid monolithic ancestry cultures (“All elves/dwarves/ orcs are the same”) in favor of a broader cultural worldview. • Use ancestries as adjectives (“Gnoll bandits are attacking villages,” rather than, “Gnolls are attacking villages”) to avoid forcing narrow morality onto sapient creatures. • Focus on villainy as a choice, not a biological or cultural imperative. • Avoid the trap of perceiving civilization from a single viewpoint (usually “settled lands = civilized lands,” so that everywhere else is uncivilized). • Understand and move away from the trope of heroic characters as the saviors of “lesser” folk. • Make use of cultural inspirations from reliable sources, with the aim of centering other cultures and perspectives from a position of respect. COLONIALISM: THE SHORT VERSION Colonialism is a topic far too broad to be properly summed up in this or any other short treatise. But in a nutshell: The history of our modern age has been defined by specific groups of people laying claim to the entire world over centuries of exploration—and not caring that the rest of the world had other peoples living in it at the time. The history of colonialism is a history of conflict and warfare. Of groups clashing over control of wealth and natural resources. Of one group of people raiding into and claiming lands not their own, and treating the lives and livelihoods of folk living in those lands as plunder. And if any of the above sounds vaguely similar to any fantasy RPG you’ve ever played, you might get a sense of the problem. At its heart, every fantasy roleplaying game tells a story. Our stories take place in specific worlds, and often explore a lot of the negative aspects of those worlds in the course of showing off the best parts of those worlds. All heroes need evil to fight against, after all. But colonialism needs to be treated differently than many of the other negative aspects of our game narratives, because the harm of unexamined colonialism can hurt players and the people near them in very real ways. For many of us, the story of the game takes place entirely in our imaginations—both the good and the bad. But for just as many players, the bad aspects of a game’s narrative are made real in their own experiences, every day of their lives. For many of us, the stories of heroism and adventure we know best are stories of colonialism—and being aware of how colonialism in a game can harm others who play the game is the first step in addressing that harm. 119 The sections that follow explore this checklist in greater detail. Ultimately, none of the thoughts and suggestions presented here are anything like a complete fix for the harmful colonialist legacy of fantasy roleplaying, with that task sitting firmly in the hands of the designers working on 5e D&D and other modern fantasy games. But these are just some of the things we can do as GMs to help address that legacy—and to build better worlds and adventures as a result. BEWARE MONOLITHIC THINKING Though it’s part of a much broader conversation about culture in fiction, the idea of monolithic culture in fantasy owes a lot to the world-building of J.R.R. Tolkien in The Lord of the Rings, which has long provided a bedrock foundation for fantasy fiction and RPGs. Monolithic culture is the idea that all members of a particular ancestry share a consistent set of outlooks, ideals, and OTHERING 120 The earliest versions of D&D worked on the assumption that the world of the game was one in which sophisticated humans and demi-humans (to use the parlance of the original edition— elves, dwarves, gnomes, halflings, and so forth) were locked into perpetual conflict with other peoples. Orcs and goblins, kobolds and lizardfolk, hobgoblins, bugbears, and more were the evil enemy, to be fought alongside more monstrous foes such as dragons, aberrations, and the undead. When one group of people—whether in our game worlds or in the real world—reduces another group of people to the status of default enemies, that’s a process called “othering.” As the name suggests, othering is about defining differences between ourselves and other people that allow us to eventually view those people as wholly different from ourselves. As less than us, deserving only of contempt and violence. As sometimes not even people at all. Unsurprisingly, othering plays a huge part in colonialist thinking, creating a mindset that allows one group of people to see other people merely as obstacles to be overcome on the path to conquest and control by way of conflict. Equally unsurprisingly, othering is the first order of business in warfare—and in the war games that were inspired by the conflicts of history, originally created as a tool to teach the strategies of conflict and colonialism to European army officers. When playing a miniatures tactical skirmish game, a player doesn’t think about the morality involved in attacking, defeating, and killing imaginary enemies on the other side. It’s just a game, after all. And as the earliest versions of fantasy roleplaying gaming evolved from war gaming, that “it’s just a game” sense of not caring about the morality of fighting and killing sapient humanoid peoples was locked in. It established a narrative baseline for fantasy RPGs that was rooted in othering. And so the idea that whole cultures of sapient humanoids can be painted as irredeemably evil has lingered within fantasy games, even fifty years and more than five editions of D&D later. behavior—to the point where any member of an ancestry who doesn’t show off their people’s acknowledged traits might be treated as abnormal. Even in fictions where that approach makes solid narrative sense and has benign intent (as with the elves and dwarves of The Lord of the Rings), monolithic culture can only ever tell a single story—and the best fantasy RPG campaigns tell stories in multitudes. We don’t have to look far to find monolithic culture in our games, as that concept is baked into the selection of ancestry that’s been front and center in every D&D Player’s Handbook, and in many of the games D&D has inspired. Our first entry point into the world of the game tells us that all dwarves are bonded by mining and forge craft, clan ties, and a hatred of specific other ancestries. All elves are lovers of art and nature, aloof and distant, detached and vengeful. All orcs are shaped by barbarism and fury, embracing violence as a first resort. As a steppingstone into roleplaying, monolithic culture serves a purpose. By focusing on common archetypes, players can quickly grasp the familiar feel of their elf wizard, their dwarf cleric, or their orc barbarian, and can start off with a useful sense of how their character fits into and views the world. But the line between archetypes and stereotypes is razor thin. And especially when the negative stereotypes of an in-game ancestry show stark and hurtful parallels to the real-world stereotypes used for generations to attack the people of marginalized communities, the fantasy of the game gains the potential for harm. ANCESTRIES AS ADJECTIVES Instead of treating ancestries as nouns in the world of your game, and inevitably making use of the “all X are Y” trope created by monolithic thinking, think of ancestries as adjectives. An ancestry should be used to give flavor to conflict, not to define conflict across the board. One of the most standard adventure hooks in fantasy games goes something like this. “Goblins are attacking the village! The characters need to help!” It’s a straightforward setup. It’s fun. But as written, it embraces the explicit idea that the goblins are attacking the village simply because that’s what goblins do. So when that hook comes to mind or appears in a published adventure, put yourself in the frame of mind that attacking villages isn’t what goblins do across the board—then figure out what kinds of goblins might engage in that sort of behavior. For example: Goblin cultists are attacking the village. Or goblin bandits are attacking the village. Goblin refugees are attacking the village. Goblin men’s-rightsactivists are attacking the village. Any of these alternative scenarios sets up the same basic adventure—but in these other scenarios, goblins aren’t the noun. They aren’t the agents of conflict simply because they exist to create conflict. Rather, they’re the adjective giving more context to who the agents of conflict are, letting you explore the story of why they’ve embraced conflict as a choice. YOU ARE WHAT YOU DO Mike, always seeking a lazy approach, likes to shake up monolithic thinking by changing the game’s traditionally ancestry-focused motivations into paths one chooses to follow. If hobgoblins are raiding nearby trade roads, it’s never just hobgoblins. It’s hobgoblin cultists of Krasar, demon prince of war and bloodshed. Mike also likes to provide a juxtaposition when making use of members of an ancestry traditionally coded as “evil” in the game by showing off explicitly good members of that ancestry. Those orcs of Thrasix are a bunch of jerks, sure. But those orc paladins of Vorn? They’re good-hearted protectors of the land. Why are cultists or bandits or refugees or MRAs attacking a village? You can probably come up with any number of good reasons on which you can hang a solid story. But none of those reasons have to revolve around the weak idea of: “Because that’s the way they are.” THE GANG’S ALL HERE As an additional side benefit, thinking of ancestries as adjectives makes it easier to move away from the habit of forging threats in homogenous groups. If all goblins aren’t sneaky thieves and reavers by biological or cultural necessity, maybe a goblin bandit gang in a published adventure consists of ne’er-do-wells from different ancestries led by a goblin? Or maybe a group of goblins looking for easy money have been seduced into a life of crime by a duplicitous dwarf con artist? In every way, moving your game away from the archetypes that feed stereotypes makes for better story. JACKIE MUSTO BUT I JUST WANT BAD GUYS TO FIGHT! When shaping heroic story, it’s a given that the heroes need to do heroic things. And if the story of your campaign involves conflict between different peoples, different kingdoms, different territories, different clans, it’s perfectly reasonable to want to make use of the wide range of creatures in the game as anchors for that conflict. (If that wasn’t the case, a lot of the rest of this book would be a waste of your time.) Nothing in this section is meant to make you stop using orcs, hobgoblins, giants, and other sapient folk as foes. But when you do, just ask yourself: “What is it that’s making these orcs, these hobgoblins, these bugbears, these giants, these hags drive the conflict?” And look for an answer more interesting than: “Because they were born evil.” Asking and answering that question lets us establish a more level playing field between the sapient creatures who fill the world of our games. You can move away from the notion that orcs, goblins, kobolds, giants, duergar, drow, hags, troglodytes, ogres, doppelgangers, and all the rest of the wide range of sapient creatures in the game are specifically prone to warmongering, casual violence, betrayal, humanoid sacrifice, and any of the other elements on your adventure-hook-conflict checklist. As GMs, we can move away from the idea that certain types of sapient creatures exist only as fodder for conflict. Rather than treating specific groups of sapient creatures as inherently violent and defined by the combat tactics hardwired into their ancestry traits and stat blocks, you can establish that those folk are no more likely to be violent or aggressive than the player characters and their own peoples. But if and when orcs, giants, goblins, doppelgangers, hags, and more are pushed to conflict, their combat tactics define the specific and different ways in which those foes will mess the characters up. LET JUSTICE BE DONE Consistent with the morality of their war game roots, earlier editions of D&D made it very clear that the player characters were the arbiters of frontier justice in the game world. When evil arises, heroes are meant to deal with it, acting as judge, jury, and all-too-often executioner. Even in the 5e rules, it remains easier to kill a foe than to safely neutralize them while letting them live. Thankfully, not every combat in the game needs to be a fight to the death (as talked about in “Exit Strategies” on page 91, and “On Morale and Running Away” on page 125). However, many gaming groups—not to mention many published adventures—struggle with the idea of what the characters should do when a group of foes are left alive at the end of a fight. It’s a problem that becomes an even bigger problem in campaigns where every member of a specific ancestry is intrinsically amoral, creating the narratively grotesque idea that good characters should feel compelled to kill evil humanoids just because. 121 BIOESSENTIALISM “Bioessentialism” is a word that’s never appeared in any edition of D&D. But it’s the concept that underpins the game’s original colonialist worldview, and thus has been present in fantasy gaming, unnamed and unseen, since the beginning. Short for “biological essentialism,” it’s the idea that the core traits and behaviors of certain sapient peoples and creatures are biologically hardwired in—and as a result, can’t be changed by intent or will. For centuries, bioessentialism has been a foundational component of bigotry, racism, and dehumanizing behavior in the real world. But even as most people are quick to understand how abhorrent and wrong such beliefs in the real world are, putting a fantasy spin on it can make bioessentialism far too palatable in fiction and roleplaying games. The most obvious aspect of bioessentialism in fantasy games is ability score modifiers and suggested alignments based on ancestry, which once shoehorned characters into specific archetypal tropes. Dour, lawful, and hard-drinking dwarves with robust Constitution and penalized Charisma. Fragile and chaotic elves with heightened Dexterity and lowerthan-average Constitution. Half-orc characters established at character creation as strong, dull, and crude (as the third edition Player’s Handbook put it), and tending toward evil, with a bonus to Strength and a penalty to Intelligence and Charisma. Thankfully, ability score penalties disappeared before the release of 5e, and the current rules detach ability modifiers from a character’s ancestry altogether. But the idea of locking in behavior and morality for all creatures of a specific ancestry or type remains a problem in the representation of sapient creatures as potential foes on the GM’s side of the game. 122 It’s quite telling that in so much fantasy world-building, the fictional justice system looks an awful lot like the worst parts of our broken real-world justice systems. Corrupt city guards looking out only for themselves. Robin Hood-style sheriffs brutalizing the people of vulnerable communities. So in the world of fantasy that you and your players create, don’t be afraid to engage in the ultimate fantasy of real justice for the people of your campaign. In settled lands, you can establish that the law functions along real lines of fairness, impartiality, and restitutionbased justice. Though if you do, be aware that for some players, that might look like an attempt to sugar-coat or mythologize broken real-world justice systems—and that many people have experienced trauma within those systems, making that topic a good one to discuss with safety tools in mind. (Information on using safety tools in your game can be found in The Lazy DM’s Companion, and many places online.) A better approach is to make use of the characters’ status as larger-than-life heroes to try to redress harm done in the world in ways that center the specific needs of the harmed. Then when the characters take a bunch of rank-and-file cultists into custody after dispensing with their evil-by-choice leadership, you can let the players and characters alike define how what happens to the bad guys is focused not on the bad guys, but on the needs of the people who’ve been wronged. Whether that involves restitution or imprisonment, your game can shape the narrative of those sentences not as arbitrary punishment leveled by a justice system, but as a means of preventing those who’ve harmed before from harming again. THE CIVILIZING DIVIDE The first incarnation of D&D made it clear that the baseline world of the game was a battleground between the forces of chaos and law, barbarism and civilization. As story tropes go, that archetypal clash between the solidity of civilization and forces dedicated to destruction and anarchy is pretty potent. But the concept of “civilization” at the center of that trope is straight from the colonialism playbook. It’s said that history is written by the victors—and when those victors write history, they’re usually quick to slap the “civilized” label onto their own side. It’s always been this way, whether we’re talking about the oldest historical conflicts, the world-changing wars of the modern age, or the less subtle but equally destructive cultural warfare that colonialism epitomizes. The root of the word “civilization” connects to the concept of living in towns and cities. But when those of us who’ve grown up unwittingly steeped in colonialist thought use the term, that’s usually not what we mean. We talk of civilized lands in our fantasy, and of characters dwelling among civilized folk, and of adventurers passing beyond the boundaries of civilization. And when we do so, we should ask ourselves: What are we actually saying? When defining the world of our games, we can create settled lands, filled with permanent farmsteads, villages, towns, and cities. We can shape wilderness, sparsely populated and filled with peril. We can talk about peoples and creatures who live in nomadic settlements, or who live under a tight code of law, or who are fiercely independent. But when we use the word “civilized” rather than “settled” to exclusively describe lands dotted by permanent towns and cities, we’re implicitly describing nomadic cultures as uncivilized. When we talk about the record of civilization being the written annals of a particular culture or ancestry, that can easily be heard as saying that histories recorded in story or song are the mark of less-civilized cultures. A conflict between a settled agrarian nation and a land of wilderness nomads could be a great setup for a campaign story. But avoiding the use of “civilization” to describe only the settled nation lets you easily make it clear that both lands are equally civilized with respect to their own specific cultures and histories. BARBARIAN RHAPSODY The other side of the “civilized” coin is the millenniaold trope of labeling different groups of people with descriptives such as “barbaric.” As many players are aware, D&D and the many other games descended from it are somewhat unique in having a character class—the barbarian—named after what was originally an Ancient Greek cultural slur. But much more recently—and much more importantly—“barbaric” and similar terms have been used as epithets to harm the members of marginalized groups, and to reinforce the divide between colonizing peoples and the victims of colonialism. As with “civilized,” if the word “barbaric” ever comes to mind when describing a group of humanoids or other sapient creatures in your game, ask yourself what you actually mean by that. When looking for words to replace “barbaric” when talking about the worst behaviors sapient creatures can engage in—humanoid sacrifice, ritual murder, genocide, cannibalism, or what have you—“evil” remains a solid go-to. “Brutal” and “ruthless” are equally apt, with all three terms implying that a conscious choice underlies malevolent behavior. If you’re instead talking about a more general mode, conduct, or worldview that clearly doesn’t push into evil territory, treat that as a sign that synonyms for “barbaric” should be avoided across the board. A group of nomadic peoples might live by a code of law whose unforgiving nature is viewed as a reflection of their harsh lives in the wilderness. But describing that code as “brutal” creates an explicit contrast with the codes of other folk—and a sense that those other folk are morally or culturally superior. AVOIDING THE SAVIOR COMPLEX A trope as old as fiction itself, the savior complex refers to a narrative in which a group of people (or, in the case of a fantasy roleplaying game, any group of sapient creatures) faces significant peril—and is saved from that peril not by their own actions, but by the actions of another group of creatures. The savior complex is rooted deep in real-world colonialism, which was built for centuries on the idea that the peoples subjected to colonial conquest and cultural destruction were being “saved” by the beneficent actions of superior peoples and cultures. A common trope in the game involves the player characters stepping up to help NPCs unable to defend themselves. It’s a workable (if overworked) campaign hook. But be careful that the hook doesn’t cross over into savior-complex territory by having the NPCs’ inability to properly defend themselves revolve around their having a “less advanced” culture or worldview than that of the characters. Most of the time, a better option for that particular hook involves the people in trouble being able to take care of themselves, then having the characters’ presence solidify that capability, rather than standing in for it wholesale. Also a good idea is thinking about what things the locals are actually better at than the characters, making it clear that needing aid against exceptional threats isn’t a one-note sign of inferiority. Work toward having the characters and the NPCs as natural allies and equals, with each possessing assets and knowledge that HARDWIRED FOR EVIL Beyond baseline bioessentialism (as talked about in that sidebar), fantasy also engages in something we might call “theist-essentialism”—the idea that the traits of humanoids and other sapient creatures are instilled in them by their creator gods. Often, this feeds neutral stereotypes such as the dwarves’ love of stone and mountain, or the elves’ fascination with magic and nature. Other times, the effect is much less benign. With this trope on display, it’s not the case that orcs and bugbears and kobolds are biologically predisposed toward violence or trickery or evil. Rather, that’s just the way their violent, conniving, and evil gods made them. But whether named, renamed, or unnamed, this is effectively the same bioessentialist idea that an entire group of sapient people are compelled to evil. It defines whole cultures of sapient beings as having a single mode of thought, a single morality, and a single goal. And it drives the same wedge of flat, harmful narrative into the heart of any game. allow them to create a stronger presence standing together than standing apart. CULTURAL INSPIRATION IN YOUR GAME Stories and lore from cultures not our own can be fascinating because of their newness. Our familiarity with the tales and literature of our own cultures can make those things feel too familiar, so that the tales, literature, art, and legends of other cultures feel like a breath of fresh air. But that becomes a problem when our experience of and exposure to other cultures doesn’t come from reliable and authentic sources. Seeking out reliable voices talking about cultures not your own is a great way to explore those cultures. Libraries, bookstores, and the Internet are full of histories, books of mythology and legend, and other sources of cultural inspiration written by people within those cultures. And there are an increasing number of fantasy RPG campaign settings and player supplements based on real-world cultures and created by designers, illustrators, and others with concrete connections to those cultures. As a bonus, many such authentic game works present great advice on how players who aren’t part of a particular real-world culture can approach using fantasy tropes built from that culture. But if you’re working on your own to make use of real-world inspiration, you can follow the basic advice those game works often lay down—be respectful of the cultures you want to explore in your games. Don’t portray their peoples or traditions as exotic. Avoid the harm inherent in othering and treating new cultures as less advanced or less civilized than your game’s dominant cultures. Likewise, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that other cultures should just be avoided in your games because of the risk of using them wrongly. Rather, be active in making cultural representation in your game better—and helping your game tell better stories as a result. 123 RUNNING EASY MONSTERS Many GMs like to run a string of hard battles, one right after the other. For them, running easy monsters is a waste of time. It takes too long to set up an encounter that won’t last more than a round or two, and easy battles bore players. This section offers a few arguments against this point of view, and a number of recommendations to get the most fun out of running easy monsters. SHOWING A LIVING WORLD The monsters in a typical fantasy world don’t suddenly all become more challenging each time the party gains a new level. No doubt, the characters journey to new locations with deadlier foes as their adventures take them to places appropriate for their station in the world. But that world remains filled with countless monsters less powerful than the characters. Bandits are plentiful. Liches, not so much. As such, it doesn’t make sense that every group of hostile entities the party faces happens to be a perfectly balanced group of five to eight foes of the appropriate CR, designed to last exactly 3 rounds in an exciting fight. When 2nd-level characters go into a seedy tavern, it’s entirely plausible for them to find a bandit captain leading a bunch of drunken bandits at the bar. But it doesn’t make sense to find the same bar filled only with bandit captains when the characters come back at 8th level, unless there’s a Bandit Captain Convention in town. When the characters run into monsters weaker than they are, it reinforces the idea that they dwell in a large, living world—one that doesn’t shift its whole ecology and social structure just because the characters gained a level. SHOW OFF CHARACTER GROWTH Running easy encounters also lets the players see the growth of their characters. Players are likely to remember how challenging a battle against an ogre enforcer was when the characters were 2nd level—but now they’re taking on eight ogre guards at a time at 13th level, and wiping the floor with them. Few things are more rewarding than casting fireball into a group of evil monsters and knowing none of them will survive, even if they make their saving throws. Fighting weak foes lets the players truly enjoy how powerful their characters have become. (And as the number of those weak foes grows, “Running Minions and Hordes,” page 54, has lots of advice for keeping combat moving.) CHOICES OTHER THAN COMBAT 124 When a group of 7th-level characters are stopped by two overconfident CR 1/8 bandits, a lot of things can happen. Sure, the characters can easily dispatch the pair. But they could just as easily persuade them to step aside. The characters might interrogate them to find out who they’re working with. They might recognize the bandits as scouts and sneak around them to avoid alerting a larger band of brigands. How high-powered characters approach two bandits can tell you a lot about those characters. What motivates them? What do they do when facing clearly surmountable foes? How do they treat people weaker than they are? So instead of thinking of every situation in the game as a combat encounter, let these kinds of easy confrontations tie into all three pillars of the game, with sneaking, talking, or fighting driving exploration, roleplaying, and combat. COMBAT IN THEATER OF THE MIND The common argument that easy battles take too much time often comes from a requirement to set up battle maps with tokens or miniatures. Drawing maps in person or finding the right map for online play takes time, as does finding the right tokens or minis. Who wants to do that for a battle against two bandits? For quick, off-the-cuff battles against weaker foes, a generic battle map and some generic tokens work well. But running easy battles is also the perfect time to use “theater of the mind” play—running combat without maps or miniatures. In theater-of-the-mind combat, the GM describes the situation, the players describe what they want to do, and the GM adjudicates what happens as a result. (“Running Monsters in the Theater of the Mind” on page 47 talks about this process in detail.) In a clearly easy battle, players don’t need to worry about optimizing positioning to make the most of their combat features. Because it doesn’t really matter where the bandits are or who they’re next to if a single hit can take them out. EASY AND HARD BATTLES Though easy battles are fun, many easy battles can become boring—just as too many hard battles can come to feel frustrating and tiring. As such, you want to always switch things up between easy battles and hard battles as you run your adventures. By improvising encounters— choosing the number and types of monsters during play—you can craft easy, medium, and hard battles as the game unfolds. Don’t let the cycle of such battles become a pattern, though. You don’t want only easy battles always followed by hard battles, and so on. (“Monster Combinations for a Hard Challenge” on page 67, “The Lazy Encounter Benchmark” on page 70, and “Defining Challenge Level” on page 105 all provide guidance for encounter building.) ON MORALE AND RUNNING AWAY Our games often feature situations in which one or more monsters would flee from the characters given the opportunity. At other times, it’s the characters facing an overwhelming challenge who would like to run away, or characters with the upper hand wanting to convince a group of bandits to throw down their swords and surrender. Novels and movies are full of these kinds of scenes, where the villains or the heroes get to flee the fight and return another day. Unfortunately, the rules of 5e don’t support these scenarios the way we might picture them in our minds. But by being aware of the factors that often prevent these scenarios from working, we can create a framework to handle them. MORALE The concept of morale comes from the military games that preceded roleplaying games. As a battle wore on, the chance increased that one side would break and run, and it was perfectly acceptable for dice to decide this. Early editions of Dungeons & Dragons implemented morale using a single die roll. Later editions used checks and tables, often tending toward overly complex solutions. Fifth edition D&D returned to a simpler approach to morale, but one that still rests on a single saving throw. Ultimately, both the simple and the complex die-roll approaches can feel more like a game and less like a story. Rolling to see whether foes surrender or run doesn’t necessarily fit the narrative of who those foes are, or the purpose they serve in the campaign. The players might also be having fun with an encounter, so that you don’t want the battle to be over just yet even if the dice say so. A morale check can often feel like a coin toss. Roll high, and enemies fight to the death. Roll low, and they surrender or flee. But what makes sense for the creatures and the situation? What would be the most fun for the game? These questions are ignored when morale is determined by simply rolling a die. defeat. By the time players finally agree to start running away, their characters are usually in bad shape. When it comes to characters fleeing, initiative is a key problem. One character might start to retreat, even as others stay behind to try to accomplish a goal such as retrieving a valuable item, or to buy time. This effectively splits the party, and anyone still in the encounter is now both injured and outnumbered. If one character drops, the characters who retreated might try to return to the encounter to save them—and suddenly you have a frustrating total-party-kill scenario on your hands. Even if all characters can leave an encounter area, in an environment such as a dungeon, it might be unclear how easily the characters can elude the monsters coming after them or reach a place of refuge. Initiative works against the characters once again, because if they can move and dash, so can the monsters. A FRAMEWORK FOR HANDLING MORALE The key problem with making checks for morale is that the check is often abstract, failing to represent the situation at hand in a tangible fashion tied to the story. Even with complex tables adjusting for various factors, the MONSTERS FLEEING DANNY PAVLOV Sometimes it makes sense for a foe to flee combat. At other times, you might feel that the story should result in an enemy getting away. This is especially true of key villains, who might need to escape so they can show up in a later scene. Unfortunately for their enemies, though, the characters usually have multiple means to prevent fleeing. Spells can immobilize or slow. Magic or class features might allow a character to easily catch up to a fleeing monster. Once a foe is hindered or grappled, that buys enough time for the whole party to gang up on them, and that foe is defeated. If it happens every now and then, that’s fine. But all the time? Not cool. CHARACTERS FLEEING When the tide of battle turns against the characters, players often resist fleeing because doing so feels like 125 dice make the result too unpredictable. But we can instead lean into the story as follows. UNDERSTAND THE MONSTERS Before the encounter begins, review monster lore and stat blocks as you consider the story of the encounter. What goals do the monsters have? What motivates them? What’s the role they play in the story? One foe might fear their boss villain overlord too much to surrender, while another might gladly surrender or flee. By understanding the foes, you’re prepared to react to the characters and the encounter. UNDERSTAND THE CHARACTERS During the encounter, listen to what the characters are saying and evaluate what they’re doing. Are they communicating with their enemies? Are they offering a truce or promising only death? Those enemies will react to the characters based on their motives and mannerisms. ASSESS THE PLAYERS Separate from how the characters might be feeling, assess whether the players want the battle to continue longer and end through combat. Are they looking forward to pushing their fun combat capabilities to the limit? Or do they have broader motivations such as learning the boss villain’s location or plans? Even if the monsters offer to surrender, you don’t want to force that option on the players if it isn’t welcome. PROVIDE CUES If the motivation of foes would lead to surrender, those foes can provide cues to indicate that. A boss villain might glance nervously at the exit, or a once-confident monster could look clearly overwhelmed. You can express such details outright, or have the characters attempt easy Wisdom (Insight) checks to note them. REACT AND ADJUST Over the next round or two, have the monsters react to what the characters do, playing off that to further facilitate a surrender. For example, a character might see how nervous the monsters are and demand that they stand down. The monsters might respond by asking for coin. The characters choose to intimidate, so you improvise an easy DC, or ask a player to roleplay the scenario and have the foes react to that. You also adjust as you continue to read the players. If they see enemies offering to surrender but prefer combat, so be it. Likewise, if the players express interest in negotiation, you can switch out of initiative and jump into a more narrative mode of play to let each side state their demands. Combat can resume if negotiations break down. Assessing what the participants want and allowing monsters and characters to provide each other with cues 126 enables morale to become a tangible part of the narrative. This lets you move away from the on-off switch of a die roll and instead allow morale to become a full part of the story developed in concert with the players. A FRAMEWORK FOR RUNNING AWAY A few exceptions in the game prove the rule that sees the initiative system make it all but impossible to flee from combat. A monster designed specifically for escape might be able to remain hidden and do so. If characters are smart and flee before they’re badly wounded and close to dropping, they might run away. (“Exit Strategies” on page 91 talks about planning ahead for ways to bring combat to a close.) In general, though, the characters have too many ways to stop one or two fleeing creatures in between each of those creatures’ turns, and wounded characters flee too slowly to withstand damage from pursuing foes. To counter this, we need to step away from typical initiative for fight-to-flight scenarios, making use of the following framework instead. ASSESS TIMING Ideally, you want to monitor an encounter for the cues that tell you the characters are facing a potential totalparty-kill scenario, or that a foe needs to flee. You can encourage characters to flee when needed by describing the overwhelming power and confidence of their foes. Likewise, you can monitor the monsters’ hit points so you don’t wait too long to enact their escape. REDUCING FRUSTRATION Mike notes a few tricks that can be used to help boss foes depart a fight in order to return again, but in ways that can feel more realistic and less like deus ex machina: • The boss was a simulacrum forged by the “real” boss. • The boss has a magical vessel holding their soul, which resurrects them somewhere else. • After defeat, the boss is dug up and resurrected by faithful cultists. • When the boss is mortally wounded, powerful magic or a special feature grants them an automatic escape, such as teleporting back to a sanctum, or turning into mist and drifting back to their lair. • The defeated boss was one of many clones. As well, once a boss flees or drops early, you can have any of their servant creatures—summoned monsters, created undead, bound fiends, constructs, and so forth—quit the fight. Some might simply fall apart or magically unravel, while others are drawn back to their original dimensional realms when the magic binding them expires. It’s a great “easy out” for a GM, especially if the characters have exhausted their resources while pushing the boss to the point of flight—but still leaving them with a huge pile of underlings to deal with. MAKE AN IMPENDING TPK CLEAR DETERMINE SUCCESS OR FAILURE Players usually know when their characters are having an easy time with monsters. But they often fail to realize that the characters are facing a total party kill, doubting the risk of such a scenario until long after you as the GM see it coming. As such, you need to make an impending TPK as clear to the players as it would be to their characters. You can call out a looming TPK descriptively, clarifying as a character is attacked that their foes have the upper hand and sense imminent victory. If that doesn’t work, you might need to be even clearer, telling the players that their characters recognize how the foes they face are stronger than the party, and that continuing to stand against them might mean the characters’ end. An escape plan might simply work. The defenders in a goblin enclave could believe a tall tale that the characters were sent by their boss to test their readiness. Good job! Mercenaries or brigands might accept gold or magic as payment to stop fighting. Other plans might require successful checks, parting attacks, or spells to succeed. A Strength (Athletics) check or an attack with a slashing weapon could snap a rope, causing drapes to collapse on a group of guards. Failure might mean that escape is delayed or comes at a cost. Escape plans implemented by foes can be handled the same way. A villain sets a tavern on fire, and the characters must decide whether to save innocent people or go after their nemesis. It takes all the characters to put out the fire, so it’s an all-or-nothing decision. Alternatively, a hobgoblin war boss might need to make ability checks to swing across a pit, then cut the rope to prevent the characters from following. DEFINE OPPORTUNITIES Assessing the situation lets you identify any plausible means of escape. The capabilities of the creatures fleeing, their positioning, and the terrain around them can all be factors. For example, strong foes could shove furniture between themselves and the characters, blocking pursuit. A spellcaster might use a spell to impede a chase, to obscure the area, to set fire to vegetation or furnishings, or to cause a column or other heavy object to topple over. Foes might put noncombatants in the encounter area in danger, forcing the characters to deal with that threat instead of pursuing. PAUSE INITIATIVE When you know that either the characters or their foes are ready to flee, pause normal initiative. Let the players know that to resolve the scene, you’ll employ side initiative— an option presented in the Dungeon Master’s Guide where each side (monsters and characters) takes a turn collectively. On each side’s turn, every member of that side acts in whatever order the players (for the characters) or the GM (for foes) chooses. The side initiating the escape goes first, after which the pursuers act. You can also forego initiative entirely, simply narrating the scene as you would an exploration or roleplaying scene. COMMUNICATE THE OPPORTUNITY Players can often be encouraged to develop a plan around getting out of combat, which you can help with. Alternatively, you might propose plans based on what the characters observe. If a number of foes are all standing under a platform, suggest that the characters can cause the platform to topple to buy themselves time to flee. If the terrain doesn’t offer clear opportunities, you can encourage the players to think through their characters’ capability to create illusions, obscure their enemies’ senses, or create distractions. Throwing a sack of gold might stop ogre mercenaries, and throwing rations will typically cause a ravenous beast to pause long enough for the characters to get a safe distance away. MITIGATE OR HARNESS FRUSTRATION Players often hate it when villains escape, especially if that escape feels arbitrary or forced upon them. But the frustration level can be reduced when the players understand clearly how the foe escaped, and especially if the characters made the hard choice to allow that escape so as to deal with a different threat. Whenever possible, work to channel the players’ potential frustration toward the villain and not you—and understand that when the heroes next meet the villain, they will absolutely want revenge. OPTIONAL CHASE If doing so feels realistic and fun, you can use the chase rules found in the 5e Dungeon Master’s Guide to play out a chase as one group of combatants flees from another. But such a chase should feel rewarding, rather than simply dragging the characters back into a combat that the players are ready to end. DESCRIBE SUCCESS OR RESUME COMBAT Successfully running away can be described in loose terms. Fleeing characters get away from their enemies, and can choose a safe location they want to reach. A foe can slip away, even as you let the players know that the characters haven’t seen the last of that foe. Alternatively, if an attempt to flee fails, combat resumes with the original initiative order. At your discretion, a different attempt to flee can be made, if that would be fun and if a new plan can be employed. And remember that for both sides in a fight, surrender is always an option—and usually a far better option than dying. 127 ABOUT THE AUTHORS This book comes from the minds and the partnership of Teos Abadía, Scott Fitzgerald Gray, and Mike Shea. With the combined experience of nearly a century’s worth of writing, designing, and running D&D and other fantasy RPGs, we all have lots to say about running monsters. All three of us have designed monsters for decades, working with publishers such as Wizards of the Coast, Kobold Press, MCDM, Ghostfire Gaming, Pelgrane Press, Sasquatch Game Studio, and many more. We’ve spent years living and breathing monsters and other foes—and we’re thrilled to be able to share that passion with you. TEOS ABADÍA Teos Abadía is a Colombian-American freelance author and developer working with Wizards of the Coast, Penny Arcade, MCDM, Hasbro, and others. Teos was a primary author on the D&D book Acquisitions Incorporated, and on the vast Dungeon of Doom and Caverns Deep adventures for Dwarven Forge. His board game work includes the recent HeroQuest game relaunch. Teos shares knowledge and advocates for a healthier RPG industry as cohost of the Mastering Dungeons podcast, on his blog at Alphastream.org, and on Success in RPGs—a YouTube series helping creators identify what success in the RPG industry is like … and the concrete steps we can take toward achieving it. SCOTT FITZGERALD GRAY Scott Fitzgerald Gray (9th-level layabout, vindictive good) is a writer of fantasy and speculative fiction, a fiction editor, a story editor, and an RPG editor and designer—all of which means he finally has the job he really wanted when he was sixteen. His work in gaming covers three editions of Dungeons & Dragons, including working as an editor on all three 5e core rulebooks, as well as creating the CORE20 RPG system. Scott shares his life in the Western Canadian hinterland with a schoolteacher named Colleen, two itinerant daughters, and a number of animal companions and spirit guides. More info on him and his work can be found by reading between the lines at insaneangel.com. MICHAEL E. SHEA 128 Mike Shea is the writer for the website Sly Flourish and the author of Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master, The Lazy DM’s Workbook, The Lazy DM’s Companion, Fantastic Adventures, Fantastic Adventures: Ruins of the Grendleroot, and a number of other books. Mike has freelanced for a bunch of RPG companies, including Wizards of the Coast, Kobold Press, Pelgrane Press, and MCDM. He’s been playing RPGs since the mid ’80s, and writing for and about RPGs since 2008. Mike also happens to be the son of Robert J. Shea, author of the ’70s cult science fiction novel Illuminatus! He lives with his wife Michelle in Northern Virginia, USA. Built for the Lazy Dungeon Master, Forge of Foes helps you create, customize, and run monsters for your 5e fantasy roleplaying games. As with the material found in Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master, The Lazy DM’s Workbook, and The Lazy DM’s Companion, Forge of Foes offers easy-to-use tools and guidance to help you master the monsters in your game. TAKE YOUR MONSTERS TO THE NEXT LEVEL