nelson.com

ISBN-13: 978-0-17-673027-7

ISBN-10: 0-17-673027-3

9 780176 730277

Second

Walk

a Mile

Edition

Second

Edition

A Journey Towards

Justice

andTowards

Equity

A

Journey

in Canadian

Society

Justice

and Equity

in Canadian Society

THERESA ANZOVINO

Niagara College

THERESA ANZOVINO

Niagara College

JAMIE ORESAR

Niagara College

JAMIE ORESAR

Niagara College

DEBORAH BOUTILIER

Niagara College

DEBORAH BOUTILIER

Niagara

College

with contributions

by Yale Belanger,

University of Lethbridge, and Samah

with

contributions

by Yale Belanger,

Marei,

Niagara College

University of Lethbridge, and Samah

Marei, Niagara College

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

This is an electronic version of the print textbook. Due to electronic rights restrictions,

some third party content may be suppressed. The publisher reserves the right to remove content

from this title at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. For valuable information

on pricing, previous editions, changes to current editions, and alternate formats, please visit

nelson.com to search by ISBN#, author, title, or keyword for materials in your areas of interest.

Walk A Mile: A Journey Towards Justice and Equity in Canadian Society, Second Edition

by Theresa Anzovino, Jamie Oresar, and Deborah Boutillier

VP, Product Solutions, K–20:

Claudine O’Donnell

Production Project Manager:

Jaime Smith

Design Director:

Ken Phipps

Publisher, Digital and Print Content:

Leanna MacLean

Production Service:

MPS Limited

Higher Education Design PM:

Pamela Johnston

Marketing Manager:

Claire Varley

Copy Editor:

Linda Szostak

Interior Design:

Dave Murphy

Content Manager:

Toni Chahley

Proofreader:

MPS Limited

Cover Design:

Colleen Nicholson

Photo and Permissions Researcher:

Carrie McGregor

Indexer:

MPS Limited

Compositor:

MPS Limited

Copyright © 2019, 2015

by Nelson Education Ltd.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of

this work covered by the copyright

herein may be reproduced,

transcribed, or used in any form

or by any means—graphic,

electronic, or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, taping,

Web distribution, or information

storage and retrieval systems—

without the written permission of

the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada

Cataloguing in Publication Data

Printed and bound in Canada

1 2 3 4 21 20 19 18

For more information contact

Nelson Education Ltd.,

1120 Birchmount Road, Toronto,

Ontario, M1K 5G4. Or you can visit

our Internet site at nelson.com

Cognero and Full-Circle Assessment

are registered trademarks of

Madeira Station LLC.

For permission to use material

from this text or product,

submit all requests online at

cengage.com/permissions.

Further questions about

permissions can be emailed to

permissionrequest@cengage.com

Every effort has been made to

trace ownership of all copyrighted

material and to secure permission

from copyright holders. In the event

of any question arising as to the use

of any material, we will be pleased

to make the necessary corrections in

future printings.

Anzovino, Theresa, author

Walk a mile : a journey towards

justice and equity in Canadian

society / Theresa Anzovino, Jamie

Oresar, and Deborah Boutilier.

—Second edition.

Includes index. Subtitle for first

edition was: Experiencing and

understanding diversity in Canada.

ISBN 978-0-17-673027-7 (softcover)

1. Multiculturalism—

Canada—Textbooks. 2. Ethnic

groups—Canada—Textbooks.

3. Canada—Civilization—Textbooks.

4. Textbooks. I. Oresar, Jamie, author

II. Boutilier, Deborah, author III. Title.

HM1271.A59 2018 305.800971

C2017-904222-X

ISBN-13: 978-0-17-673027-7

ISBN-10: 0-17-673027-3

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

To my family and friends, for your love and support—Theresa

For my daughter, Joey – may you experience a world united by difference—Jamie

For my wild and wonderfully diverse family, with love—Deborah

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Foreword by Craig and Marc Kielburger

For us, “walking a mile in someone else’s shoes” is only a partial metaphor.

Our international development work through WE Charity often leads us to remote commun­

ities where the only way to travel is by foot. In the Chimborazo region of Ecuador, for example,

the road stops halfway up the Andean mountains, and we walk the rest of the way. Beside us are

our friends from the mountaintop villages, and the mules carrying cement, lumber, and other

school-building materials. We would offer to trade our comfortable hiking shoes for our friends’

bare feet, but we know if they accepted we’d never keep up.

An even more challenging walk is with groups of Maasai women and children in Kenya to

collect their families’ water from the nearest source stream. On the return trip—often two

kilometres or more—we balance a 40-litre jerry can of water on our heads like the others, some

of whom are as young as six. It’s a powerful experience that reaffirms our commitment to clean

water projects in communities like theirs, to ensure their walk is much shorter and the children

can go to school.

We’ve learned innumerable lessons by travelling great and difficult distances, literally and

figuratively, with our diverse overseas partners. Understanding other ways of living, thinking,

and doing has enriched our own life experience and made our work projects more effective and

impactful.

It has also inspired us to share these experiences with as many people as possible because

we are convinced that a whole generation of diversity-competent global citizens can change the

world.

We’ve now travelled with thousands of young people who want not simply to appreciate

diversity, but to live it. On our overseas volunteer trips, one-third of participants’ time is dedi­

cated to cultural immersion in the communities we visit. We eat traditional local meals, partici­

pate in centuries-old celebrations, and contribute to daily chores like the water walk.

Most importantly, when they return home, our volunteers pursue a better world with

renewed vigour. Some have even organized a fundraising “Mamas’ Water Walk,” where students

from various local schools collected pledges and completed a two-kilometre walk with water

jugs on their backs.

Leaving their comfort zones to truly connect with their fellow human beings, our volunteer

travellers gain a deeper appreciation of our world’s diversity; an understanding of how that

diversity plays out in power, privilege, and hardship; and a lifelong sense of empathy, compas­

sion, and dedication to justice and equity.

Now, living diversity doesn’t necessarily require international travel. We Canadians have the

great fortune of living in one of the world’s most diverse nations, brimming with opportunities

to meet people with different backgrounds and experiences from our own. It’s not far outside our

comfort boxes that we can find culturally different foods, music, or community festivals. Even

take a look around your own neighbourhood, workplace, or social group, and see people of

different gender, age, ability, sexual orientation, income level, and countless other identities than

yours. For the truly adventurous, visit a local temple, mosque, or church and get a glimpse into a

new way of seeing the world that will expand your mind.

iv NEL

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

There are also more tangible benefits to becoming diversity competent, in the enhanced

prospects for your career and social life. Imagine opening your job search to the world—we regu­

larly encounter fellow Canadians working in banks in China, overseeing construction projects

in Africa, or running development programs in South America. A 2008 University of California–

Berkeley study even showed that people with culturally diverse social groups have lower levels of

the stress hormone cortisol, which lowers their risk of cancer, heart disease, and Type 2 diabetes.

For all these reasons, we are ecstatic to see this book in classrooms across Canada, and we

congratulate Professor Boutilier and Professor Anzovino for translating their decades of experi­

ential learning and teaching into a practical guide to diversity competency. The knowledge and

active reflection provoked in these pages will help a generation of young Canadians to under­

stand their own identity, the place of identity in our relationships with our fellow global citizens,

and our responsibility to take action for a more equitable and just world.

We therefore urge you to see this book as just the beginning. Let it be your guide to a world

of opportunity, of understanding, of experiences, of action. You don’t have to walk a mile with a

jug of water on your head, but don’t let the title of this book remain a simple metaphor. Try not

to just see the world through someone else’s eyes, but to live it. Live diversity, and it won’t be just

your life that is better for it.

Source: Photo courtesy of Marc and Craig Kielburger

Craig Kielburger and Marc Kielburger, Co-Founders of WE

NEL

v

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

About the Authors

Source: © Ivan Ivanov/

Thinkstock.com

THERESA ANZOVINO

Theresa Anzovino has completed a Masters of Arts degree in Sociology (York University, 1994), Bachelor of Arts Degree in Sociology (University of Waterloo, 1985)

and Teaching Adults Certificate (Niagara, 1989). Her academic areas of interest

include feminist jurisprudence, migration, diversity, human rights, and universal

design for learning. She is a proud mother to son Daniel. Anzovino is a professor in

the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Niagara College and the 2013 recipient

of the Teaching Excellence Award at Niagara College. Prior to this, she worked as a

CEO for a large organization within the non-profit sector dedicated to refugee protection and resettlement. This work earned her numerous humanitarian and leadership awards. When she invites you to walk a mile in her shoes, it will be barefoot

on a beach connecting with the earth.

Source: Stokkete/Shutterstock

JAMIE ORESAR

Jamie Oresar has completed a Masters of Teaching degree (Griffith University, 2004)

and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Sociology (Western University, 2001). Her academic

areas of interest include diversity and social inclusion, criminology, globalization

and sustainable development, and gender studies. Oresar is a professor of Sociology

in the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Niagara College. Prior to this, she has

taught at the secondary level in Ontario, as well as internationally in China, Australia, and Mexico. When she is not teaching, Oresar loves to travel and spend time

outside with her partner, Joe, daughter, Joey, and dog, Bentley. She invites you to

walk a mile in the shoes that have led her across three continents.

Source: © Emily Andrews

DEBORAH BOUTILIER

Deborah Boutilier holds a Doctorate of Education degree in Sociology and Equity

Studies (University of Toronto, 2008); Master’s degrees in Sociology (State University of New York at Buffalo, 1987) and Education (Brock University, 1998), and a

Baking Certificate (Niagara College, 2013). Her academic areas of interest include

diversity and social inclusion, social constructions of gender and homicide, and the

learning processes of information technology in the practice of cross-cultural computer-mediated exchanges. When she is not teaching in the School of Liberal Arts

and Sciences at Niagara College, she loves reading, writing, baking, and walking

her dog, Harley. She invites you to take a walk in her favourite shoes, but warns you

that they leak!

vi NEL

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

About Contributing Authors

YALE BELANGER

Dr. Yale D. Belanger holds a doctorate in Indigenous Studies (Trent University),

and is Professor of Political Science at the University of Lethbridge (Alberta).

His areas of study include First Nations casino and economic development,

Aboriginal gambling, housing and homelessness, and local community

develop­ment. He has written and edited several books and dozens of articles

and book chapters, and remains a regular contributor to international,

national, and regional media. When not stuck writing at a computer, he

enjoys hiking in the coulees with Loki and Walt the dogs.

SAMAH MAREI

Samah Marei earned her degree in History from UCLA and is currently completing post-graduate work at Oxford. She has taught locally at the elementary level as well as at Niagara College, and is a teacher of Arabic at the Qasid

Institute. In addition to teaching history and sociology, Samah has spent the

last 15 years presenting workshops on Diversity and Inclusion in both the

workforce and the community. Samah sits on the Board of Gillian’s Place in St.

Catharines and spends her time volunteering at various shelters and with her

family on their Niagara hobby farm.

NEL

vii

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Brief Table of Contents

Foreword by Craig and Mark Kielburger iv

About the Authors vi

Preface

xvi

CHAPTER 1

Diversity, Oppression, and Privilege 1

CHAPTER 2

Forms of Oppression

CHAPTER 3

Social Inequality

24

47

CHAPTER 4

Gender 69

CHAPTER 5

Sexuality 92

CHAPTER 6

Race and Racialization 114

CHAPTER 7

Indigenous Peoples

137

with contributions by Yale Belanger

CHAPTER 8

Immigration 165

CHAPTER 9

Multiculturalism

192

with contributions by Samah Marei

CHAPTER 10

Religion 210

with contributions by Samah Marei

CHAPTER 11

Ability 229

CHAPTER 12

Age 257

CHAPTER 13

Families 280

Glossary

Index

viii 301

315

NEL

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Detailed Table of Contents

Foreword by Craig and Mark Kielburger

iv

About the Authors

vi

Preface

xvi

CHAPTER 1 Diversity, Oppression,

and Privilege

1

THE CONCEPT OF DIVERSITY: KEY

CHALLENGES

2

THE CELEBRATORY APPROACH

THE DIFFERENCE APPROACH

AN ANTI-OPPRESSION APPROACH

2

2

3

ANTI-OPPRESSION

AND CRITICAL SOCIAL THEORY

THE NATURE AND DYNAMICS

OF OPPRESSION

MULTIPLE LEVELS OF OPPRESSION

INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION

INTERSECTIONALITY AND THE MATRIX

OF OPPRESSION

HETEROGENEITY WITHIN OPPRESSED GROUPS

BULLYING AS OPPRESSION

3

4

4

6

6

8

9

STEREOTYPES

PREJUDICE

THE “ISM” PRISM

DISCRIMINATION

FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION

CHALLENGING PRIVILEGE AND OPPRESSION

26

27

29

33

34

36

ENDING THOUGHTS

39

READING: “HOW TO”—BECOMING

AN ALLY BY ANNE BISHOP

39

REFERENCES

44

CHAPTER 3 Social Inequality

47

SOCIAL STRATIFICATION

49

MEASURING INEQUALITY

50

POVERTY IN CANADA

52

CHILD POVERTY

STUDENT POVERTY

THE WORKING POOR

HOMELESSNESS

HOMELESSNESS AND MENTAL HEALTH

52

54

54

55

56

9

GLOBAL INEQUALITY

57

JOURNEY TOWARD JUSTICE AND EQUITY 12

INTERSECTIONALITY

58

UNPACKING OUR PRIVILEGE

SOCIAL JUSTICE

EQUITY VERSUS EQUALITY

STARTING THE JOURNEY:

THE POWER OF NARRATIVES

12

13

GENDER AND SOCIAL INEQUALITY

RACE AND SOCIAL INEQUALITY

AGE AND SOCIAL INEQUALITY

58

59

60

15

ENDING THOUGHTS

61

KNOWING YOUR OWN STORY

15

ENDING THOUGHTS

16

READING: THE SINGER SOLUTION TO

WORLD POVERTY BY PETER SINGER

61

REFERENCES

66

READING: EXCERPTED FROM BUT YOU

ARE DIFFERENT: IN CONVERSATION

WITH A FRIEND BY SABRA DESAI

18

CHAPTER 4 Gender

REFERENCES

21

GENDER AS A SOCIAL CONSTRUCT

CHAPTER 2 Forms of Oppression

24

FIVE FACES OF OPPRESSION

25

STEREOTYPES, PREJUDICE,

AND DISCRIMINATION

26

NEL

AGENTS OF GENDER SOCIALIZATION

GENDER INEQUALITY

EDUCATION

EMPLOYMENT AND GOVERNMENT

VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

69

70

71

76

76

76

78

ix

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

THE –NESS MODEL: DECONSTRUCTING

THE BINARY AND THE CONTINUUM

GENDER IDENTITY

GENDER EXPRESSION

BIOLOGICAL SEX

ATTRACTION

ENDING THOUGHTS

79

81

81

83

85

85

READING: FIGURE SKATING IS THE MOST

MASCULINE SPORT IN THE HISTORY OF

FOREVER BY JULIE MANNELL

86

REFERENCES

90

CHAPTER 5 Sexuality

SEXUAL IDENTITIES

GAY OR LESBIAN

HETEROSEXUALITY

BISEXUALITY

PANSEXUALITY

ASEXUALITY

THE POWER OF LANGUAGE

INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS

MONOGAMY

POLYAMORY

92

93

94

96

97

97

98

99

99

99

102

CURRENT ISSUES IN SEXUALITY

102

TECHNOLOGY AND INTIMATE

RELATIONSHIPS

SEXUAL EDUCATION

SEXUAL VIOLENCE

102

103

103

INTERSECTIONALITY

GENDER AND SEXUALITY

ENDING THOUGHTS

107

107

107

READING: RIGHTS FIGHT PROMPTS NEW

TRANS-INCLUSIVE RULES FOR ONTARIO

HOCKEY BY WENDY GILLIS

107

REFERENCES

CHAPTER 6 Race

and Racialization

111

114

THE CONCEPT OF RACE AS

A BIOLOGICAL MYTH

115

WHAT IS RACISM?

117

FORMS OF RACISM

HOW RACISM OPERATES

x 118

119

ACKNOWLEDGING RACISM

IN CANADA

WHITE PRIVILEGE AND FORMS

OF ITS DENIAL

COLOURBLINDNESS

RACISM AND THE LAW

WHITE SUPREMACY AND RACIALLY

MOTIVATED HATE CRIMES

RACE AND LAW ENFORCEMENT

120

121

123

123

123

125

INTERSECTIONALITY:

THE COLOUR OF POVERTY

127

A POST-RACIAL SOCIETY

127

ENDING THOUGHTS

128

READING: BROKEN CIRCLE: THE DARK

LEGACY OF INDIAN RESIDENTIAL

SCHOOLS BY THEODORE FONTAINE

129

REFERENCES

134

CHAPTER 7 Indigenous Peoples

THE LANGUAGE

USING THE RIGHT WORDS

THE ROLE OF STORYTELLING IN ABORIGINAL

COMMUNITIES

TREATIES

THE ROYAL PROCLAMATION OF 1763

AND THE PRE-CONFEDERATION TREATIES

THE NUMBERED TREATIES

137

138

138

138

141

142

142

LAND CLAIMS

145

LEGISLATION

147

ABORIGINAL IDENTITY

THE INDIAN ACT

RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS

THE WHITE PAPER

BILL C-31

THE ROYAL COMMISSION ON ABORIGINAL

PEOPLES (RCAP)

MURDERED AND MISSING INDIGENOUS

WOMEN (MMIW)

LESSONS

147

148

149

151

153

153

153

155

ENDING THOUGHTS

158

READING: A MOTHER TO A TEACHER

158

REFERENCES

161

NEL

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 8 Immigration

HISTORY OF CANADIAN

IMMIGRATION POLICY

PERIOD

PERIOD

PERIOD

PERIOD

PERIOD

PERIOD

PERIOD

PERIOD

PERIOD

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

CANADA APOLOGIZES

THE “UNDESIRABLES”

AN APOLOGY FOR KOMAGATA MARU

AN APOLOGY FOR THE CHINESE HEAD TAX

AND EXCLUSION

AN APOLOGY FOR JAPANESE INTERNMENT

NO APOLOGY FOR JEWISH

REFUGEES ABOARD THE ST. LOUIS

IMMIGRATING TO CANADA

WAYS OF IMMIGRATING TO CANADA

AN OVERVIEW OF THE NUMBER

OF IMMIGRANTS COMING TO CANADA

DECIDING WHO GETS IN

MYTHS AND FACTS ABOUT REFUGEES AND

IMMIGRANTS COMING TO CANADA

SETTLEMENT AND INTEGRATION

DEFINING SETTLEMENT

SETTLEMENT AS A TWO-WAY PROCESS

FACTORS AFFECTING SETTLEMENT

CONTEMPORARY MIGRATION ISSUES

IN CANADA

SYRIAN REFUGEE CRISIS AND

CANADA’S RESPONSE

TEMPORARY FOREIGN WORKER PROGRAM

CREDENTIAL RECOGNITION FOR IMMIGRANT

PROFESSIONALS

ENDING THOUGHTS

165

166

166

166

167

167

167

167

167

167

167

168

168

168

168

168

169

169

170

IS MULTIKULTI A FAILURE?

MULTICULTURALISM AS A DESCRIPTIVE

AND PRESCRIPTIVE CONCEPT

196

THE ARCHITECTURE OF MULTICULTURALISM

EARLY MULTICULTURALISM

196

197

DOES CANADIAN MULTICULTURALISM

WORK?

198

WHAT DO THE NUMBERS TELL US?

IS “ETHNIC ENCLAVE” JUST A FANCY NAME

FOR “GHETTO”?

172

172

177

177

178

179

ENDING THOUGHTS

203

READING: AN IMMIGRANT’S SPLIT

PERSONALITY BY SUN-KYUNG YI

204

REFERENCES

208

CHAPTER 10 Religion

RELIGIOUS AFFILIATION IN CANADA

211

214

214

LEGISLATING ACCOMMODATION

215

WHAT IS NOT COVERED BY THE LAW

YOU BE THE JUDGE

“CAN’T WE ALL GET ALONG?”

THE ELEPHANT IN THE MOSQUE

INTERSECTIONALITY

216

216

219

220

221

183

RACE AND RELIGION

AGE AND RELIGION

221

221

183

183

ENDING THOUGHTS

223

READING: NATIVE SPIRITUALITY

AND CHRISTIAN FAITH – BEYOND

TWO SOLITUDES BY DONNA SINCLAIR

223

REFERENCES

227

184

185

CHAPTER 11 Ability

REFERENCES

189

DEFINING DISABILITY

NEL

210

PLURALISM AS A FUNDAMENTAL

PRINCIPLE

185

CANADIANS ARE NOT AMERICANS

200

201

READING: THE THINNEST LINE –

WHEN DOES A REFUGEE STOP BEING

A REFUGEE? BY BETH GALLAGHER

CHAPTER 9 Multiculturalism

200

CANADA’S MULTICULTURAL FUTURE:

DOES IT EXIST?

THE FUTURE OF RELIGION IN CANADA

172

194

192

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION DEFINITION

DISABILITY BINARISM

VISIBLE AND INVISIBLE DISABILITIES

229

230

230

231

231

194

xi

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

PEOPLE FIRST APPROACH AND

INCLUSIVE LANGUAGE

231

DISABILITY HISTORY IN CANADA

233

INSTITUTIONALIZATION AND COMPULSORY

STERILIZATION

VETERANS WITH DISABILITIES

DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION AND

THE ANTI-PSYCHIATRY MOVEMENT

DISABILITY HUMAN RIGHTS PARADIGM

NEOLIBERALISM AND CUTBACKS

ENTERING THE 21ST CENTURY

DISABILITY PERSPECTIVES

234

234

GENERATION Z

GENERATION ALPHA

AGEISM

AGEISM AND EMPLOYMENT

AGEISM AND YOUTH

AGEISM AND THE AGING POPULATION

COMBATING AGEISM

263

263

265

265

266

268

271

234

235

235

235

INTERSECTIONALITY

236

ENDING THOUGHTS

273

READING: KEEPING AN EYE OUT:

HOW ADULTS PERCEIVE STUDENTS

BY ADAM FLETCHER

273

REFERENCES

277

BIOMEDICAL PERSPECTIVE

FUNCTIONAL LIMITATIONS PERSPECTIVE

SOCIO-CONSTRUCTIONIST PERSPECTIVE

SOCIO-ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE

LEGAL RIGHTS PERSPECTIVE

SOCIAL INCLUSION PERSPECTIVE

236

237

238

238

239

241

10 FACTS AND FIGURES ABOUT

HAVING A DISABILITY IN CANADA

241

SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS AND AGE

ABILITY AND AGE

SEXUALITY AND AGE

CHAPTER 13 Families

271

271

272

273

280

DEFINING THE FAMILY

281

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY

283

COMMON-LAW UNIONS

283

SAME-SEX UNIONS

284

DIVORCE AND REMARRIAGE

285

245

BLENDED FAMILIES

285

MENTAL HEALTH AND STIGMA

247

SINGLEHOOD

285

ENDING THOUGHTS

248

PARENTHOOD AND FAMILY

286

LONE-PARENT FAMILIES

287

THE CONTEXT OF DISABILITY

WITHIN OUR SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT

THE DIFFERENCE APPROACH AND

ACCOMMODATION

MOVING FROM ACCOMMODATIONS TO

ACCESSIBILITY

UNIVERSAL DESIGN

UNIVERSAL DESIGN AND POSTSECONDARY

EDUCATION

243

243

244

245

READING: LIVING WITH POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

BY VESNA PLAZACIC

250

FOSTERING AND ADOPTION

288

REFERENCES

254

ASSISTED HUMAN REPRODUCTION

288

CO-PARENTING

290

CHILDFREE COUPLES

290

FAMILY VIOLENCE IN CANADA

290

CHAPTER 12 Age

AGE AS A SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION

THE GENERATIONAL DIVIDE: AGE

STRATIFICATION IN CANADA

TRADITIONALIST

BABY BOOMER

GENERATION X

GENERATION Y

xii 257

258

258

259

261

261

262

SPOUSAL ABUSE

CHILD ABUSE

291

291

INTERSECTIONALITY

292

RACE, ETHNICITY, AND THE FAMILY

GENDER AND THE FAMILY

292

292

NEL

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS

AND THE FAMILY

ENDING THOUGHTS

293

READING: GROWING UP WITH SAME-SEX

PARENTS BY ANDREA GORDON

294

NEL

REFERENCES

298

Glossary

301

Index

315

292

xiii

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

A Unique Learning System

Walk A Mile employs a unique approach that integrates academic and experiential

learning tools to help motivate students to actively engage with the text and issues of

social justice and equity in the real world. This learning will help prepare students to

challenge oppression and injustice when they experience it in their personal and professional lives. Students come to understand that the enterprise of diversity is to construct

a society where all people can experience the world as just; where all people have equivalent access to opportunities; where all people, including those historically underserved

and underrepresented, feel valued, respected, and able to live lives free of oppression;

and where all people can fully participate in the social institutions that affect their lives.

Most reviewers agree that Walk A Mile is unlike any other resource currently available for

diversity courses.

THREE TYPES

OF BOXES

82

CHAP TER 4

IS...

RE TH

t Racism

hing Abou

ents Teac

3).

,” Stud

aign (201

a Costume poster camp

re Not

a Cultu

University

), Ohio

“We’re

(S.T.A.R.S.

Society

in

PICTU

(Continued)

Gender

NEL

Carol and Amanda Todd

rules

by the

y play

isog as the

logy of

m as lon exists a patho and ethnirk for the

still

racially

The

still wo 10a). There

intains oss Canada.

ma

20

,

acr

ton,

s and

(Wise

t create ghbourhoods city of Bramp ing

tha

ion

nei

lat

enc

the

regated

icle on city is experi here

cally seg r, in an art

t this

ht”—w

Sta

e sugges as “white flig instream

Toronto

som

t

ma

to

tha

t

white

referred

reports

former iti es are no

menon

ng

a pheno

co mm unab le be co mi :

co mf ort rity population

the mino

t equity:

eEmployment under the

the visibl nt

ile

men

Wh

uire

Act

Req

segme

ent Equity

minority

to

Employm that employers

loded

of Canada e employment

has exp t tw octiv

use proa

ease

rep res en Bramps to incr

of

practice ion of four

thirds

lation,

representat groups: women,

’s popu

ted

ton

ies,

designa

ide

res nts

disabilit

wh ite ind lin g.

people with peoples, and

the

Indigenous munities in ity

are dw mb ers

d com

equ

nu

racialize

loyment tion

Th eir

19 2

ce. Emp

workpla the accommoda

nt fro m

we

s

2001 to

mandate e with special

400 in

differenc

ded.

In each chapter throughout the textbook, we have

featured Canadians as AGENTS OF CHANGE—doing

extraordinary things to create social change in their

neighbourhoods, their communities, and their country,

and across the world. They are advocates against micro

and macro levels of oppression. They are motivated by

principles of social justice and equity.

We begin with Carol Todd, a Canadian icon for

resiliency, strength, and hope. When you meet Carol,

some of your first impressions are of a woman of

quiet strength and depth, a mother with a heart filled

with love, a tech-savvy educator with a passion for

teaching, and a stalwart anti-bullying advocate.

Her reach is far and wide; I am never sure when we

talk if she is at home in British Columbia or another

part of the world speaking in elementary schools, high

schools, colleges, universities, and other public venues

about anti-bullying, mental health, and cyber safety

initiatives. What is constant is the impact Carol has

on those she speaks to. It never ceases to amaze me

the number of students I teach who talk about having

been bullied and reaching out to Carol and finding

support and help when they did. It speaks to me of

Carol’s authenticity as an agent of change and of the

impact of her daughter Amanda’s legacy.

On September 7, 2012, Amanda Todd shared with

the world an eight-minute YouTube video entitled My

Story: Struggling, bullying, suicide, self-harm that was

a silent flash-card narrative of her own experiences of

being bullied. The message posted by Amanda below

the video reads:

10

than

when

s

a decade at’s

11. That’

0 in 20 12 per cent, in

t. Th

169 23

per cen

or

e by 60 ural ideal so

people,

23 000 population ros

multicult

3)

’s

the city picture of the (Grewal, 201

y.

a

Silva

hardly d in this countr

Bonilla- ialEduardo

rac

celebrate

Professor ion produces racial

iversity

isolat

rmalizes

Duke Un s that white

that no noting that

aviour

assert

and beh 10b) concurs, ents where

(2012)

ns

tio

nm

cep

Wise (20 en in enviro se children

ized per

ldr

ty. Tim

tho

natinequali of raising chi can result in

ies are

cts

racism racial inequalit temic issue

the effe

sys

discusses

that

no one up to believe

is not a es. More genization

g

growin that marginal dual deficienci d by a kind

rce

ural and based on indivi ess is reinfo e tax exempiten

tters lik n policies,

but one oss society, wh

tio

ity in ma

erally acr t attacks equ ple, immigra ge. Professor

tha

peo

of code First Nations inclusive langua white privof

tion for ent equity, and t the defence all for equal

tha

ym

congests

s: “I am

emplo

Silva sug ething like thi judged by the their

lanil

Bo

of

nds som

ple to be

colour

ilege sou y; I want peo not by the

nit

and

opportu ir character

the

NEL

tent of

of

nee

s when

measure

122

CH AP

TE R 6

Race and

ation

Racializ

I’m struggling to stay in this world, because everything

just touches me so deeply. I’m not doing this for attention. I’m doing this to be an inspiration and to show

that I can be strong. I did things to myself to make

pain go away, because I’d rather hurt myself than

someone else. Haters are haters but please don’t hate,

although I’m sure I’ll get them. I hope I can show you

guys that everyone has a story, and everyone’s future

will be bright one day, you just gotta pull through. I’m

still here aren’t I?*

Carol and Amanda Todd

xiv paign,

ture cam t to

Their pos

ugh

versity.

t are tho ity reveals

Ohio Uni costumes tha

then

o Univers

group at

een

s at Ohi of that group,

student

r Hallow

student

.S.) is a

ate ove

ber

t since

paign by

(S.T.A.R

a mem

ing deb

gest tha

in Society rked an interest this poster cam t if you are not students sug

er

m

Racism

k?

tha

spa

ut

clai

Oth

ed

thin

s

s.

has

Abo

ent

ber

g

you

e,”

e stat

its mem are. What do

Some studin rebuttal, hav

ts Teachin , Not a Costum

y

ht be to

Studen

racism.

s,

the

ture

mig

t

ent

feed

Cul

ges

ype

a

s and

Other stud

t stereot or clever to sug

“We’re

eotype

e too far. how painful tha

ny

ate ster

prolifer

ess gon

is not fun

l correctn able to dictate ire identity, it

politica

be

son’s ent

uld not

you sho s are not a per

ype

more

stereot

a loss of

AGENT OF CHANGE

Photo courtesy of Carol Todd

In Their Shoes uses students’

stories to give an authentic voice

to the lived experience of “real”

people that other students can

identify with.

Picture This ... uses carefully

chosen photographs to speak to

the undiscovered themes in each

chapter as students consider the

historical and future implications of each photograph.

Agent of Change uses examples of Canadians, some famous

and others not, to highlight the

ways in which positive social

change can impact families,

neighbourhoods, communities,

Canadian society, and beyond.

IN THEIR SH

OES

If a picture can

say a thousand

this student

story on for size words, imagine the storie

s your shoes

– have you walke

could tell! Try

d in this stude

The first thing

nt’s shoes?

I feel that everyo

ne

stand, is that

the LGBTQ comm needs to underwas themed zombi

unity is more

those specific

than just

es. I how5 letters. Sure

ever didn’t want

they may be the

prevalent aspect

to dress as a zombi

most

s of the gay comm

drag. My mothe

e, and went in

much more that

unity, but there

r gave me her

the world needs

is so

old bridesmaids

did

my

are people who

to understand.

makeup, threw

dress;

There

are

on a wig from

store and my black

the costume

erence at all. The asexual; who have no sexual

Converse. Showi

prefpansexual comm

as a “Glam-pyre”

ng

to all humans

was the best thing up at school

regardless of gende unity are attracted

time. Everyone

that I did at the

only some of

was both impres

the sexuality identit r identity. These are

sed and in subtle

that I arrived at

mixed up with

ies that need

a school dance

shock

not be

romantic attrac

in drag. The attent

and feeling I had

tions. A person

pansexual and

ion

with being in

may be

identify as female

drag was like

another world.

, but may be hetero

mantic. This would

being in

It was what I was

Now a disting

missing from my

people but roman mean she is sexually attracted rouishable note

life.

to all

tically attracted

I need to mentio

rent life differe

Whereas a gende

to the opposite

n is my curnces between

sex.

rfluid male may

my drag person

S. Klawe, and

but homoroman

identify as an

a, Raven

my genderfluidit

asexual

tic or heteroroman

y. I arrive to an

tainment place

the gender he

tic depending

enterin drag, with the

identifies at the

on

intent of entert

people or being

time.

I myself am a

aining

a source of enjoym

Genderfluid homo

woman to forma

ent. I may arrive

romantic male,

sexual

l

and

events

as a

homo

but

and galas, but

derfluidness. I

mantic and hetero sometimes a genderfluid hetero that’s my genseparate my craft

sexual female

roof drag and my

identity throug

. It took about

for me to come

h the means of

gender

6 years

to the conclusion

the place or event

going. People

earth and what

of

may ask me why

I am

it was I was attrac who I am on this

I am doing drag

formal event,

had thought I

when I’m not.

at

a

was simply bisexu ted to. At a time I

I’m simply embra

other gender

al. I also thoug

asexual, as well

cing my

at that time. There

ht I was

as Transgender

is the odd event

and there that

ed at one point.

so sure of myself

I do combine

here

I was

I had gone to

the genders and

what is known

lengths of resear

the costs of the

create

as gende

ching

surgeries. But

like all big decisio

A few years follow r non-conforming.

mother’s advice

ns, a

gives the cleare

ing that dance

my first year of

st perspectives.

, when I finishe

I may not have

colleg

d

told her everyt

my first drag pagea e, was when I participated

she always just

hing all the time,

in

knew something

but

I was surrounded nt where I came close to winnin

was up. I remem

one day, both

by

g.

my parents, my

other

ber

people like me

expressing thems

sister, and I were

having dinner

who enjoy

elves in this way

outside on the

just

I knew I was “hom

and

patio when I broug

feeling like I was

e.” At that same in that moment

ht up

in the wrong body

had heard of

time of the year

templating on

and

that

these

I was conI

taking

tities that I didn’t other sexualities and gende

feminine, or testos either estrogen to becom

r idenknow about early

e more

terone to be more

So after doing

in high schoo

time I didn’t consid

male. At this

some research

er or even know

I had found what l.

have been lookin

meant. I was still

what Genderfluid

I

g for; after years

an identified gay

searching. Gende

of

I was frustrated

male at the time

rqueer and Gende wondering and

with how I was.

but

tities that I had

rfluidity were

I

was too femin

never known.

idenine to call myself didn’t have a label. I

These

discovery of being

then lead to the

male, but my

too masculine

body was

dual-spirited,

to call myself

agender, bigend

gender non-conform

female. But my

what all mothe

er,

mothe

ing as well as

rs do, is let me

which apparently

to genderfuck,

explain my reason r did

behind how I

means to playfu

felt, and then

ing

with these typica

said, give it time.

lly confuse others

thinking back

l gender roles

Which

on it now, was

or expres

the best advice

So now with all

have gotten. After

I could

this in mind, don’t sions.

a few months

have the tough

time I found that

to a year from

assume I didn’t

childh

that

ood or teen years.

there are so many

elementary schoo

tities than what

All through

other gender

l, middle schoo

I was exposed

idenl and in the first

of my high schoo

to, or what

My first real experi

half

l life I was bullied

ence with regard I thought.

being too femin

about my voice

derfluidity was

s to my genine, or that I was

back

word, a fag. To

for lack of a better

Laura Secord Secon when I was in grade 11. I attend

say I didn’t let

dary School, which

ed

these notions

me would be

tion of being where

get to

had a reputaa lie. I

the “gay kids”

life where I wante went through a dark stage

its focus on the

went because

in my

d

arts

of

and just get away nothing more than to not exist

lgbtq community. and its notable acceptance

from everything.

of the

It was at a Hallow

at home; all the

I kept it hidden

een dance that

feelings and the

endured. There

bullying events

were times I tried

I

to tell myself “You’

re

CHAPTER 1

Diversity, Oppression, and Privilege

On October 10, 2012, Amanda took her own life.

Following her death, Amanda’s YouTube video went

viral and her story has received international media

coverage. In the years since this tragedy, Carol has

courageously continued the conversation Amanda

started by speaking to students, parents, educators,

and helping professionals around the world. Carol has

appeared on the Dr. Phil Show (2014) and the Fifth

Estate’s documentaries, “The Sextortion of Amanda

Todd” (2013) and “The Stalking of Amanda Todd:

The Man in the Shadows” (2014). The list of keynote

addresses and public presentations found on the

Amanda Todd Legacy Society website is staggering.

Carol is the recipient of numerous awards for her

anti-bullying and mental health activism, including

the Me to We Award for Social Action, TELUS WISE

Outstanding Canadian Citizen Award, BC Community Achievement Award, and more. While very

deserving of this recognition, what matters most to

Carol is the ability to continue the conversation that

Amanda started so that we can create communities

and neighbourhoods that practise kindness and give

a sense of belonging and inclusion for all. As Carol

prepared to travel to the Netherlands in 2017 for the

trial of Aydin Coban, her grief was palpable as she

wrote of Amanda, “what I would give up to be able

to see her, feel her, touch her, cuddle her and kiss her

once again.” And still Carol channels this grief to save

others from the kind of bullying and emotional pain

Amanda suffered.

Students describe Carol as inspirational …

authentic … strong … a voice for change.

Through Carol, Amanda’s legacy continues to be

one of transformational social change for all of us as

Canadians.

To learn more, visit the Amanda Todd Legacy

Society at http://www.amandatoddlegacy.org/

*Source: http://www.amandatoddlegacy.org. Reprinted with permission.

NEL

NEL

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

KEY TERMS

Every term is carefully defined and conveniently

located in the text margins beside the section where

the term is first introduced. A complete glossary of all

key terms is included at the end of the text.

In the past, the

concept of race

ically categorize

was used to biolo

people based

gone of two black

teristics, inclu

ding skin colou on physical characstudents stared students, during which time

r. “This notio

emerged in the

at him for his

most

n of race

context of Europ

discu ssion , he

reaction. Durin

nations and peop

ean dominatio

g the

listen ed

while a stude

of Guelph, 2016 le deemed non-white” (Univ n of

nt used the

ersity

). Genetic scien

rever se-di scrim

this biological

ce

now

tells

us that

concept of race

Race: A concep

and so-called inati on

of Guelph, 2016

is

t no longer

race-card

). And while the a myth (University

recogn

ized as valid, except

arguments, and

race has been

biological conce

exasperin terms of its social

discre

pt

ated by their

race with a focus dited, the social constructio of

consequences;

inability to

in the

recognize their

the negative effecton difference between group n of

the concept of race past,

own privs has

referred to

of marginalizing

ilege, he thoug

biological division

some of these

and oppre

ht

s between

groups within

human beings,

self … try walki to hima society. This ssing

of social const

based

ng a day

process

ruction of race

primari

ly on their skin

in my shoes.

is

racia lizati on

colour.

This is, in

(University of referred to today as

part,

Ontario Human

Guelph, 2016

the inspiration

Racialization: The

). The

Rights Comm

for

process

the title of this

of social constru

ission (2016)

guage to recog

book.

ction of race

uses

nize

whereby individu

tion by describing and reflect the process of raciallanals or groups

are subjected to

“racialized group people as a “racialized perso izadifferen

and/or unequal treatme tial

n” or

” instead of the

inaccurate terms

more out-dated

based on their designa nt

THE CONCEP

“racial minority,”

and

“person of colou

T

member of a particul tion as a

r,” or “non-Whit “visible minority,”

ar “race.”

OF RACE AS

e.”

Racism is an

A

Racialized person

is inherently superideology that one racialized

BIOLOGICAL

racialized group: or

group

An

superiority is assoc ior to others. This belief

individual or group

MY

in racial

iated

TH

of

with

some of histor

atrocities. It is

other than Indigen persons,

y’s greatest

important to

ous

So what is race

understand that

peoples, who are

operates to marg

subjected

? Some

racism

inalize and oppre

to differential and/or

have used the

levels, including

ss at a number

unequal

concept of

treatment based

race to mean

Racism can be individual, systemic, and socie of

on their

a biological

designation as a

openly displayed

tal.

member of a

division of huma

emails, and hate

as offensive jokes

particular “race.”

ns based

crimes, but be

on phys ical

in prejudicial

more deeply roote ,

attrib utes

attitudes, value

d

Visible minority:

such as skin

s, and racialized

types that can

Outdated

colour and

becom

stereoterm used primari

other physical

tutions over time, e embedded in systems and

ly in

traits. And

by Statistics Canada Canada

instifor hundreds of

justice, policing, most notably in systems of

a category of personsto refer to

years, we

crimi

who are

have used these

tion, and empl education, health, media, immi nal

non-Caucasian in

oyment

differrace

graences to draw

white in colour and or nonAs a nation, we (Roy, 2012).

a colour

who do

have acknowledg

not report being

line that has

gized to racial

Indigen

ed

categ

ous.

and apoloized groups affect

people into four orized

ed

that is a part

Person of colour

of Canada’s past. by historical racism

or five

: Considered

grou ps we

and racial discri

Unfortunately,

to be an outdate

call races .

racism

d term, which

mination rema

Academics have

was originally intende

in Canadian socie

in a

d to be

ty, and this must persistent reality

more positive and

ously equa ted erroneacknowledged

be recognized

inclusive of

biolo gy

as a

and

people than the

with desti ny

terms “nonracism (Ontario starting point to effectively

for many

white” or “visible

address

Human

years, usually

minorities”;

Consider the case Rights Commission, 2016

was used to refer

with the

).

of a student name

to people

effect of reinfo

found that as

who may share

d Samuel,

rcing white

a black student

commo

superiority.

experiences of racism. n

studying in Cana who

was reminded

every day that

da, he

he was black.

During the 1820

described every

In fact,

Reverse discrim

day

1830s, American s and

ination:

experience in unde of his life in Canada as a perso he

Discrim

ination against

physician and scien

that meant, Samu rstanding racism. When asked nal

whites, usually

tist Samuel

in the

what

el described daily

Morton conducted

form of affirmative

people remin

experiences wher

action,

ded

a sysemployment equity,

tematic analy

his skin yet they him they didn’t see the colou e

and

sis

stared at him,

diversity policies

dreds of huma of huntheir purses a

; the concept

touched his hair, r of

n skull s

of reverse discrim

little

held

from all over

ination,

from, called upon tighter, asked him where

specifically reverse

the world

he came

racism,

to confirm his

told him he was him to speak for all black

is considered by

hypothpeople,

many

a role model for

to be

esis that there

impossible becaus

him, and decla

other students

were dife of existing

red

like

power structures

ferences amon

had friends who they were anti-racist becau

in society.

g races not

se they

were black. Samu

only in term

heated discussion

el also described

Race card: Term

s of their

on racism in a

a

that refers

origin, but also

class where he

to the use of race

in

terms

to gain an

was

of their brain size.

advantage.

Morton

NEL

CHAP TER 6

END-OF-CHAPTER SKILLBUILDING MATERIAL

Each chapter ends with a reading, followed by several

discussion questions that instructors can use as the

basis for a written assignment, an oral discussion, or a

class debate. The KWIP feature closes each chapter by

leading students through a process of reflective questioning using the following steps:

K: Know it and own it—What do I bring to this?

W: Walk the talk—How can I learn from this?

I: It is what it is—Is this inside or outside my comfort zone?

P: Put it in play—How can I use this?

ONS

ESTI

ON QU

SCUSSI

of imprestheory

DI

selves into

s (1956)

Goffman’ t we divide our d through

Erving

tha

iologist

use to win e” selves,

suggests

1. Soc

which we

nagement

ck stag

who

our “ba

sion ma stage” selves,

exist as

nt

life, and

ay

and

“fro

s,

ryd

our

masks

s of eve

some way

off our

ting.” In For those

the realitie w us to take

“ac

m.

are not

which alloare, when we

mechanis ans,” how

coping

adi

we really n becomes a

e” self?

nated Can

isio

as “hyphe their “back stag alleviate

s

this div

live

nce

their

ed to

what

who live can they experie was suppos

enia,” but

en

ralism

and wh

lticultu ltural schizophr

ideal, mu

“cu

2. As an hor’s notion of

the aut

Race and Racializ

ation

115

ers,

of her eld

g views

opposin

merge the herself?

t

done to

ions tha

author

can be

dimens

s, and the

self in

ity; for

employer identifies her s her ethnic t, single, and

ide

hor

inis

bes

aut

s

fem

m to

3. The e other factor

t she’s a

ever, see

icates tha parents, how

includ

itage.

she ind

their her

n,

example, good cook. Her in terms of

nomeno

y

ctly

tional phe

not a ver mselves stri

a genera author is

the

t this is

identify

e the

think tha

becaus

Do you

k this is

thin

or do you ed”?

nat

“hyphe

that it

ersity is

g

s learnin

KWIP

about div

al truths oneself as it doeat how our

dament

look

the fun learning about

cess to

One of

KWIP pro raction.

as much

involves ers. Let’s use the h social inte

oug

about oth are shaped thr

identities

T DO I

IT: WHA

N

ects

D OW

ing asp in

examin

involves as the first step

process

ation

KWIP

social loc

in the

The “K” n identity and ent.

ow

pet

r

com

of you

diversity

becoming

IT AN

IS?

KNOW

G TO TH

BRIN

using on

lity by foc

as the

ial inequa en referred to so, it

es of soc

(oft

In doing

psed issu of difference

roach).

uted to

has ecli

aspects

bands app t have contrib ethnic

superficial s, and steel

s tha

nce

ation of

osa

ere

aliz

an

saris, sam d the power diff itical margin

Canadi

ore

and pol

within

s

ic,

has ign

ual

nom

ivid

ial, eco

and ind

the soc

groups

zed

g full

iali

ensurin

and rac

ent for

ans by

instrum

society.

sm is an on for all Canadi olvement

nation

sm as

y with

inv

lusi

lticulturali

an

y

rali

ntif

inc

mu

adi

l

den

ide

ultu

and

Can

to

to

both

does not

• Officia ion, equity,

people

• Multic to construct a ages everyone

pat

ourages anadian

ethnicity ralism provides ectful

tici

our

or

enc

s

par

is hard

enc

Thi

ralism

anese-C icial

g their raceicial multicultu ceful and resp

estries.

like Jap

ensurin

multicultu t ethnic anc

Off

ship. Off

rk for pea

eren

identities

al unity.

or citizen legal framewo

their diff h hyphenated ense of nation

ada as a

on Can

and

wit

s. Using

at the exp ch emphasis us—our idena social e.

identify

stereotype

ns

mu

anadian

ds

zing and ralism envisio

that bin

coexistenc

or Italo-C ralism places too

essentiali

ultu

the glue

t runs the

ralism is mosaic, multic

multicultu not enough on

ups tha

lticultu

by

the

Mu

nic gro

ada

and

groups

of

•

hor

tinct eth ersity within

mosaic

hens Can

adians.

the metap de up of dis

div

icy strengt that we do not .

Some

the

pol

s.

ma

tity as Can

cial

iate

ype

the idea

a society ing to apprec ethnic stereot

s are

as an offi

in society

to

fail

lturalism together through ticipate equally

all familie rriages

:

m

of

ers

lticu

ing

alis

mb

risk

Mu

ow

ltur

ns

ma

•

the foll

ucing me

multicu

ng and par

Canadia

and all

and red might include

binding the same to belo ity in diversity,”

inated;

subord

be

examples all women are

slogan “un rk for a country racterized by

have to

racing the

extended; d.

By emb unifying framewo a population cha

is

a

nge

are arra

provides ographic reality uistic diversity.

ling

ethnic

whose demral, racial, and

zed and

rk

iali

ewo

rac

fram

ultu

ed

ethnoc

marginaliz sm’s celebratory

sm has

rali

ulturali

lticultu

• Multic in Canada. Mu

groups

L

JOURNA

ation

social loc

ntity and agree or dis

:

r own ide

y you

how you es, explain wh lticulturalism

dful of

ons

ut mu

Being minuence your resp ements abo

It

stat

adians.

might infl the following

e for Can when

isiv

h

div

y

is

agree wit

al identit

an ideal

TY:

ACTIVI

LEARN

CAN I

: HOW

E TALK

dy

case stu

nario or

d

sents a sce problem-base

cess pre

ugh

KWIP pro lk the talk” thro

” in the

The “W

you to “wa

llenges

that cha

learning.

NG TH

WALKITHIS?

FROM

CH AP

TE R 9

lism

Multicultura

205

NEL

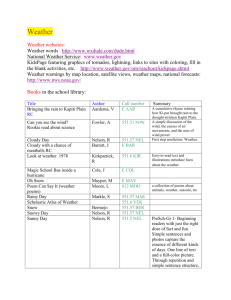

COURSEMATE

Nelson Education’s Walk a Mile CourseMate brings course concepts to life with interactive

learning and exam preparation tools that integrate with the printed textbook. Students activate their knowledge through quizzes, games, and flashcards, among many other tools.

Interactive Teaching and Learning Tools include interactive teaching and learning tools:

NEL

●●

Flashcards

●●

Multiple Choice Quizzes

●●

Picture This with reflection questions

●●

Diversity in the Media with critical thinking questions

●●

The KWIP framework with reflection questions … and more!

A Unique Learning System xv

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Preface

A JOURNEY TOWARD

JUSTICE AND EQUITY

IN CANADIAN SOCIETY

The second edition of Walk A Mile uses an

anti-oppression framework with the goal of

promoting justice and equity for members

of diverse populations while challenging patterns of

oppression and discrimination. The journey toward

justice and equity acknowledges the historical

oppression and social exclusion of affected

communities in Canada—placing the experience of

affected communities at the centre of analysis and

embracing the hope of creating a society where the

dignity and intrinsic worth of every human being is

respected and valued.

Ten years ago, we struggled to find a resource for

teaching and learning that was written at a level that

would engage our students and that provided a balance

of theory and content that would work in experiential and active learning environments. So we created a

course manual called Walk a Mile. Thanks to the vision

and tenacity of Jillian Kerr, Senior Learning Solutions

Consultant at Nelson Education, the course manual

evolved into the first edition, Walk a Mile: Experiencing

and Understanding Diversity in Canada.

As the new subtitle suggests, Walk a Mile: A Journey

Toward Justice and Equity in Canadian Society moves the

content of this second edition in the direction of justice

and equity.

Our Reviewers Write…

“I love the new title and the focus on equity and

justice. It takes it to a deeper level.”

When we were approached to write a second

edition by Nelson Education Ltd. publisher Leanna

McLean, we were grateful for the opportunity to update

the pedagogical elements and research. We were equally

grateful for the opportunity to refocus and expand

upon concepts like oppression, power, privilege, intersectionality, social justice, and equity. This second

edition has also been enriched by the thoughtful, thorough suggestions provided by reviewers from across

the country. Their feedback has been instrumental in

recreating this resource, which aims to balance student

engagement activities, theoretical material, and critical

thinking and self-reflection exercises, written in an

xvi inviting style so that every learner becomes part of the

learning experience.

Our Reviewers Write …

I have been reviewing books for a new … Diversity course and this manual is the first textbook

that attempts to go “beneath the tip of the iceberg.”

It is not just a text full of theory and concepts, but

attempts to capture the real life application and

significance of the people whose lives they are supposed to address.

GOALS OF THIS BOOK:

WHEN STUDENTS WALK

A MILE, THEY WILL BE

ABLE TO …

Our goals as authors of this textbook were to create a

text that would help students to

●●

●●

●●

●●

●●

●●

●●

define diversity as a framework that acknowledges difference, power, and privilege using

principles of social equity, social justice, and

anti-oppression

actively engage in examining issues of diversity,

including social inequality, race, ethnicity, immigration, religion, gender, sexuality, ability, age,

and family in ways that are relevant to the lives of

students today

extend learning beyond the classroom to the real

world and diverse experiences of affected persons

and communities

enjoy the interactive experience of learning about

diversity in a non-traditional manner

understand diversity through greater self-awareness, knowledge, and empathy for those who

experience prejudice and discrimination

model ways of being in the world that help to

promote awareness, respect, and inclusiveness in

building positive relationships with diverse communities

critically analyze roots of oppression and inequality

for historically disadvantaged and underrepresented

NEL

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

communities and make connections with systemic

discrimination experienced by these communities

in contemporary society

●●

devise sustainable and inclusive strategies to

eliminate barriers to full participation of diverse

communities

WALK A MILE IN THE

CLASSROOM

As educators, we make many decisions—including if

and how we want to use a textbook. One of the features that we often look at is the textbook’s fit with our

course plan. Walk a Mile was designed to provide you,

as an instructor, with a balanced presentation of information in steps that mirror the process of becoming

diversity competent. The intention of its design was to

give you ideas to help with the development of course

plans, including course goals, student learning objectives, assessment plans, units of instruction, and course

schedule. For those instructors with an established syllabus, Walk a Mile can be customized to include specific

chapters to meet your needs and provide you with the

content required to cover your course’s topics.

Our Reviewers Write …

The materials, concepts, and pedagogical techniques in this text are everything I would want to

include in a diversity course.

Walk a Mile welcomes your students into an invitational learning environment where content and peda­

gogy interact in non-traditional ways. More than a

compendium of intellectual content, this text will engage

your students through an active learning approach that

makes diversity relevant to their personal and professional lives. Students “must talk about what they are

learning, write about it, relate it to past experiences,

and apply it to their daily lives. They must make what

they learn part of themselves” (Chickering & Gamson,

March 1987). Walk a Mile uses pedagogical elements to

tap into the voices, experiences, creativity, and passion

of postsecondary students, infusing it with content relevant to students’ own lives. Walk a Mile is shaped by a

belief that experiential activities are among some of the

most powerful teaching and learning tools available.

For example, the pedagogical element entitled In Their

Shoes shares powerful experience narratives of students

as tools for empathy, while the pedagogical element

entitled KWIP facilitates reflection on experience and

action. Together, these elements awaken in students an

understanding that learning scaffolds on experience

and reflection. Most of our reviewers identify Walk a

NEL

Mile’s uniqueness and strength as its ability to engage

students through its active learning approach.

Our Reviewers Write …

I especially like this text because it takes the

hassle out of teaching. These authors have done

a lot of the work for faculty: the book is full of

good ideas for developing and supporting a syllabus, it has plenty of in-class activity ideas, and

opportunities for students to engage with the

material outside of the classroom and through

the Internet.

PEDAGOGICAL FRAMEWORK

Walk a Mile is a text that supports the implementation of

active learning based upon research on best practices in

learning environments (Michael 2006). The hallmarks

of active learning include: a holistic approach that

involves cognitive and affective domains of learning;

embracing students’ unique ways of knowing, learning,

and experiencing; making connections between academic knowledge and practice; emphasizing reflective

practice; and active engagement in critical thinking

processes that involve analysis of concepts, forming

opinions, synthesizing ideas, questioning, problem

solving, and evaluating information (McKeachie &

Svinicki 2006).

Our Reviewers Write …

The pedagogy integrating academic and experiential learning tools is inspiring. It has the ability

to motivate students and teachers to actively engage

(think, reflect, and reflex) with the text and issues

of diversity in the real world.

Walk a Mile: A Journey Toward Justice and Equity in

Canadian Society requires learning in the cognitive and

affective domains. It is not a book that focuses exclusively on the intellectual journey and content because

learning about diverse communities also requires

empathy and understanding that are culled from

experience.

Opening Lyrics

Each chapter begins with a line from a song that relates

to the specific theme in each chapter. Why do we use

song lyrics and not a quotation from a book or article?

Music unites people and builds a commonality at the

outset of the chapter. Music also makes us feel—its

lyrics help us relate to the experience as we take in the

emotional aspects of a song. And feeling, as we know, is

an important part of the process of becoming diversity

competent.

Preface xvii

Copyright 2019 Nelson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content

may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Nelson Education reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

In Their Shoes

In Their Shoes is a pedagogical tool that uses students’

stories to give an authentic voice to the lived experience of “real” people that other students can identify

with. In Their Shoes consists of a piece of original work

written by a college or university student on the specific

theme of each chapter. The student authors come from

a variety of different programs and institutions. With

courage and integrity, they shared their personal narratives so that readers might grow in empathy, understanding, and knowledge as they walk a mile “in their

shoes.” Many of the student authors saw the writing of

their stories as an opportunity to engage in the political act of storytelling. Their hope has been that a dialogue might begin about the validity of lived experience

as a form of knowledge, and about the importance of

teaching and learning empathy. Student readers actively

engage with these stories because they are relevant to

their lives here and now.

Picture This…

Does a picture say a thousand words? The pictures in

Walk a Mile have been selected to evoke meaningful

critical thought in the minds of students and in their