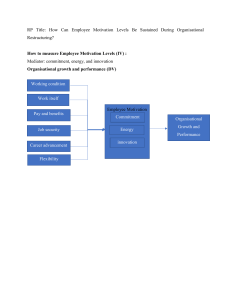

Rapid #: -21731877 CROSS REF ID: OCLC#222800873 LENDER: CTN (Southern Connecticut State University) :: Main Library BORROWER: BUB (University of Bristol) :: Main Library TYPE: Book Chapter BOOK TITLE: Modern corporations and strategies at work USER BOOK TITLE: Modern corporations and strategies at work CHAPTER TITLE: Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes in the Technology Industry: A Comparative Study of the AMD and Nvidia BOOK AUTHOR: Nayak, Bhabani Shankar; Tabassum, Naznin EDITION: VOLUME: PUBLISHER: YEAR: 2022 PAGES: 9-34 ISBN: 9789811946486 LCCN: HD30.28 OCLC #: 1344490682 Processed by RapidX: 12/8/2023 12:40:42 PM This material may be protected by copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code) Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes in the Technology Industry: A Comparative Study of the AMD and Nvidia Anniken Emilie Høiås, Naznin Tabassum, and Bhabani Shankar Nayak 1 Introduction Organisational culture has long been discussed in the literature, with several different models being proposed to explain and identify it within companies. Many of these models look at various aspects of the culture using fixed or given dimensions, such as Schein’s (1985) iceberg model and Handy’s (1993) model of culture. The model selected for this research is the cultural web as it provides the flexibility to use findings from within the culture of an organisation. This chapter contains an outline of organisational culture and its different theories and models, as well as an investigation of the organisational culture in Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) and Nvidia using the cultural web model. The aim of the study is to understand the impact that organisational culture can have on gender discrimination and inequality in the workforce. In the existing literature, it appears that there is very little research on the relationship between gender discrimination and organisational culture, despite the fact that companies, especially in the technology industry, are well known for their tendency to be more male-dominated and lacking in gender diversity (Arun & Bryony, 2015). Having identified a gap in the literature, the current study examines the organisational culture of AMD and Nvidia to identify whether there are gender stereotypes within them. As such, the review of the literature is linked to the organisational culture of companies operating explicitly A. E. Høiås (B) 1415 Oppegaard, Norway e-mail: annikenhoias@hotmail.com N. Tabassum University for the Creative Arts, Epsom, UK e-mail: N.Tabassum@derby.ac.uk B. S. Nayak Buisness Schoool, University of Derby, Derby, UK e-mail: Bhabani.nayak@uca.ac.uk © The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2022 B. S. Nayak and N. Tabassum (eds.), Modern Corporations and Strategies at Work, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4648-6_2 9 10 A. E. Høiås et al. within the technology industry. The review focuses both on articles which discuss the themes of culture and organisational culture, and on secondary case studies about culture within technology companies. Content analysis and a qualitative approach are employed to assess AMD and Nvidia’s organisational culture from the perspective of current employees. As such, the assessment should benefit our understanding of organisational culture and suggest measures for avoiding gender inequality and discrimination in the workforce within the technology industry. 2 Understandings of Organisational Culture Culture can be defined as the knowledge and/or characteristics of a particular group of people sharing the same language, religion, social habits or interests (Zimmermann, 2017). Culture is also often associated with patterns of human behaviour which can be challenging to understand from an outsider’s perspective (Pedersen and Sorensen 1989); this definition can be related to Hofstede’s explanation that culture influences the way humans behave and think (1997). Organisational culture is a complex topic that has been defined in various ways in the literature. Lundy and Cowling (1996) arrived at perhaps the most commonly known definition, stating that culture is “the way we do things around here”. However, although this definition is correct, it is not all-encompassing. Weber et al. (2012) explored the idea that managers use the business’s corporate culture to differentiate their business operations from those of competitors. In comparison, Ortega-Parra et al. (2013) suggested that organisational culture can be defined as the system of values, beliefs, and behaviours that subconsciously drive employees’ decisionmaking. Hofstede (2021) however, sees organisational culture as the way in which members relate to one another, and how they relate to their work and the outside world. Organisational culture has been recognised as an essential influential factor that helps to analyse an organisation in various contexts (Dauber et al., 2012). It is established that organisational culture is important and relevant to the understanding of how organisations can be both effective and distinctive (Khatib, 1996). This culture is a significant force which affects the behaviour of the employees and overall effectiveness of the organisation (Marcoulides & Heck, 1993; Schein, 1990). In this way, organisational culture can be defined as “the ‘set theory’ of important values, beliefs, and understandings that members share in common. Culture provides better (or the best) ways of thinking, feeling and reacting that could help managers to make a decision and arrange activities for the organisation to meet the business goals and objectives” (Sun, 2008: 137). Having a strong organisational culture facilitates shared values and helps ensure that everyone within the organisation is on the same track (Robbins, 1996). The organisational culture can influence factors such as employee motivation and morale, productivity and efficiency, and quality of work, and can Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 11 contribute to employees’ attitudes in the workforce; these can be identified using different models and techniques (Campbell & Stonehouse, 1999). 3 Approaches and Models for Studying Organisational Culture There are three approaches to the classification of organisational culture: by dimensions, by interrelated structure, or by typology. Each of these approaches can be used to define organisational culture via different organisational culture models, and each has its advantages depending on which aspect of the culture is the focus (Dauber et al., 2012:3). Various empirical studies have employed the dimensions approach (Chatterjee et al., 1992; Hofstede et al., 1990; Sagiv & Schwartz, 2007) to measure different dimensions of organisational culture, along with scales that can relate to, or be compared with, another dimension (Dauber et al., 2012: 2). The interrelated structure approach was used by researchers such as Allaire and Firsirotu (1984) Hatch (1993) and Schein (1985). These studies concentrated on developing a link between organisational culture as a concept to other characteristics of an organisation, rather than on single variables and/or dimensions, as in the dimensions approach (Dauber et al., 2012: 2). As Mayer et al. noted, “This approach tends to be multidisciplinary in nature, [and] commonly characterises configuration models” (1993). The typology approach is based on categorising an organisation by predefined vital characteristics (Cartwright & Cooper, 1993) and does not focus on comparing these characteristics or their relationship to each other, as in the interrelated structure approach (Dauber et al., 2012: 3). 4 Exploring Organisational Culture Several models have been developed to describe the relationship between the phenomena and variables within an organisational culture and their role within an organisation (Martins et al., 2003). Questions have been raised as to how the dimensions of an organisational culture can be described. Sathe developed an organisational culture model which focuses on the leadership influencing the organisational system and personnel regarding the actual and expected behaviour patterns; this model has been criticised for not examining the influence of external factors on the organisational culture. Other models which have been used to interpret organisational culture will now be discussed. 12 A. E. Høiås et al. Schein’s Iceberg Model Using an interrelated structure approach, Schein (1985) created the iceberg model which divides the culture into three distinct levels: artifacts, values, and assumptions. Artifacts are the obvious elements of the organisation that even outsiders can see, while values are the declared set of values and norms within the organisation, and assumptions are the beliefs and behaviours that are so deep within the organisation that they may go unnoticed. Schein argued that values, beliefs, and norms exist are internal to humans, and therefore hard to identify and interpret. Hatch (1993) criticised this model for “not addressing the active role of assumptions and beliefs in forming and changing organisational culture”, and added a fourth domain called symbols. Both of these models are strongly focused on parts of the culture in an organisation, and Hatch specifies four processes that link these domains. Moreover, both models provide simplified but limited perspectives due to their high level of abstraction (Dauber et al., 2012) (Fig. 1). Handy’s Model of Organisational Culture The model connects organisational culture with organisational structure, and Handy argues that these two characteristics cannot be separated. There are four types of culture (power, role, task, and person) which can be identified by the extent to which an organisation is both formalised and centralised. Handy also explained that employees might be unsuccessful at all of these types of culture, depending on their preferences and personalities, and that it is up to the organisation’s executives to handle all four types of culture. In comparison, Schein (1985) argues that culture is an entity that is almost impossible to measure, study, or change. Fig. 1 Schein Cultural iceberg model (McGuire, 2012) Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 13 Fig. 2 Handy’s cultural model (Handy, 1993a, b) There are some limitations to Handy’s approach, in that the four different cultures are fixed or given. This compares to the six elements in the cultural web model chosen for the current study, and there are no fixed or given aspects as every company has the same outcomes within these elements. The reason for this is that these cultures are within every organisation, rather than something which has been created, negotiated, or shared by people within it. It can be argued that none of the models is preferred over the others, as each is suited to different kinds of organisational circumstances (Fig. 2). 5 Significance of Gender-Diverse Organisational Culture Diversity is an essential aspect of culture (Jeffs & Morrison, 2005). According to Loden and Rosener diversity can be classified in terms of primary dimensions, such as age, race and gender, or secondary dimensions, such as work background, income, education, or religion. Neither of the abovementioned organisational culture models address diversity, and indeed there has been little research on gender diversity and organisational culture. However, what the existing studies do show is that having a gender-diverse organisational culture is important not least because it can positively impact growth, productivity, and innovation (Arun & Bryony, 2015). Having women in top management roles can result in higher earnings and greater shareholder wealth (Welbourne, 1999). Moreover, companies with more women in their IT departments tend to be further along in the digital transformation and have a more robust financial performance (Sullivan et al., 2021). Ford and Richardson (1994) believe the reason for all of this is because women tend to be more concerned than men when it comes to ethical behaviour in the workplace. 14 A. E. Høiås et al. Alfrey and Twine (2016) undertook a study on gender inequality which analysed the environment in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and medicine) workplaces. The research identified three ways in which the females they studied responded to this gender-discriminated working environment. The first finding was that the females tended to downplay their femininity, in line with other studies (Eisenhart & Finkel, 1998; Faulkner, 2000; Kvande, 1999; McIlwee & Robinson, 1992). The second was that they tended to neutralise the existing gender differences by discursive positioning (Jorgenson, 2002) and the third was that they tended to stop working in STEM fields (Blickenstaff 2005). Interestingly, Schilt (2006) found that women who gender transitioned received higher pay and were treated with more authority and respect than when they were females. While having a gender diverse organisational culture can be beneficial, as mentioned above, significant gender inequality remains in STEM workplaces, indicating that women do not want to work within them (Schilt, 2006). Females experience gender discrimination and masculine environments and, therefore, decide to move companies and industries (Jorgenson, 2002). 6 The Cultural Web Model The cultural web model developed by Johnson and Scholes can be seen as an extension to the model created by Deal and Kennedy with a typology approach that helps to identify the organisational culture (Johnson et al., 2008: 197–203). Johnson (1988) described the paradigm as “the set of beliefs and assumptions [that are] held relatively common through the organisation, taken for granted, and discernible in the stories and explanations of the managers”. The cultural web model can help an organisation identify which aspects of their culture are successful and which need to be developed, changed, or even removed. The model is based on six elements, as shown in Fig. 3. The cultural web model was chosen as the framework for interpreting different phenomena regarding areas of employee behaviour and organisational decisionmaking processes. The model unites various aspects of culture such as diversity, in contrast to how it is traditionally dispersed across the literature, for example, in Handy’s model. The framework provides pre-determined dimensions that allow the categorisation of the organisational culture of a business. As such, this may be a benefit or a challenge, depending on the research needs, and is also provided for in Schein’s iceberg model (Sun, 2008: 140). However, the strength of the cultural web model lies in its simplicity, as it provides a clear overview of the cultural elements and organisational entities, such as structure and control systems. The model also brings in how each component overlaps and impacts the others (Freemantle, 2013a, 2013b). As such, the model can help managers control and direct employee behaviour, such as by using selected rites, stories, symbols and shared values (Sun, 2008: 140). Johnson and Scholes (1999) argue that these paradigms are necessary because organisational culture is rooted in an employee’s mind, and so asking someone to describe their organisation’s paradigm would likely lead to a satisfactory answer. Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 15 Fig. 3 Cultural web model 7 The Cultural Web as a Tested Model The cultural web model has been widely used in previous literature to analyse the academic culture of different sectors such as higher education, and in work-based learning (Doherty & Stephens, 2019; Morris 2018). These studies have valuable insight into the academic sector’s culture, revealing leadership issues connected to the power and organisational structures, respectively. The model has also been used to change maternity leave services in the NHS, as Freemantle (2013a, 2013b) identified a dysfunctional culture with devastating consequences for patient care. Based on the findings generated by the model, Freemantle suggested improvements for the efficiency, effectiveness and environment under study. Therefore, the cultural web model has been tested in various sectors and is suitable for looking at the organisational culture of businesses. 16 A. E. Høiås et al. AMD's net revenue from 2014 to 2019 in million U.S. Dollars 10 5.5 5 3.99 4.31 2015 2016 5.25 6.47 6.76 2018 2019 0 2014 2017 Fig. 4 AMD net revenue 2014–2019 (Statista 2021a, 2021b, 2021c) 8 Organisational Culture in the AMD Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) is an American multinational semiconductor company producing microprocessors, chips, embedded processors, and graphics processors (AMD, 2021) founded as a start-up company in 1969 in Silicon Valley (AMD, 2021). AMD has more than 11,000 employees worldwide and had a revenue of $6.7 million in 2019 (AMD, 2021) (Fig. 4). 9 Organisational Culture in Nvidia Nvidia is an American multinational technology company that designs graphics processors and chips (Nvidia, 2021a, 2021b). Founded in 1993 by the current CEO, Jensen Huang, in Silicon Valley (Nvidia, 2021a, 2021b) Nvidia has more than 13,000 employees worldwide and had a revenue of $11.72 million in 2019 (Statista, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c) (Fig. 5). Nvidia's net revenue from 2014 to 2019 in million U.S. Dollars 15 11.72 9.71 10 5 6.9 4.13 4.68 5.01 2014 2015 2016 0 2017 2018 Fig. 5 Nvidia net revenue 2014––2019 (Statista, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c) 2019 Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 17 The Analytical Outlook Three commonly used research techniques are statistical, thematic, and content analyses. Content analysis is a general term for different ways of analysing text and is used when exploring a great deal of textual information to determine the trends and patterns in the words used (Pope et al., 2006). Thematic analysis is employed to closely examine data and identify similarities or patterns (Braun & Clarke, 2006: 79). In contrast, statistical analysis concerns collecting data and recovering the patterns and trends (Pope et al., 2006). In this research, ten employee reviews gathered from both companies’ websites were thematically analysed to identify any patterns. The reviews were also compared to find similarities and differences in perspective both within and between the companies, and to reveal patterns potentially operating in the same industry. The Time Frame As one of two time frames employed in research, cross-sectional studies are used when a study involves a particular phenomenon at a specific time (Steedle & Zahner, 2015) while longitudinal studies occur over a more extended time so that change and development can be observed (Saunders et al., 2016). This study was cross-sectional because of the time limitation of around eight months, making a longitudinal study less feasible. 10 The Organisational Culture in AMD and Nvidia and the Cultural Web This section analyses the organisational culture in AMD and Nvidia using the cultural web model. Published between 1–31 January, 2021, the selected secondary source reviews were written by current employees of AMD or Nvidia. Other figures in this section are taken from the companies’ websites and annual reports, to demonstrate and visualise what the employees were saying in terms of diversity and the gender gap within the companies. The reviews used in this analysis can be found in Appendices 1–2. 11 Analysing the Organisational Culture in AMD Using the Cultural Web Model As mentioned previously, AMD is a company with more than 11,000 employees worldwide. Table 1 shows the common themes mentioned in the employee reviews of AMD’s organisational culture. 18 A. E. Høiås et al. Table 1 Cultural web model analysis of AMD Stories • Culture (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Diversity (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b) • Hiring and promotion (Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Symbols • Balance (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Flexibility (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Dress code (Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Power structure • Management style (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Turnover (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Organisational structure • Authority (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Favouritism (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Control system • Rewards (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b) • Salary (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Flexibility (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Rituals and routines • Training (Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Opportunities (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Content Analysis of the Employees’ Reviews The Stories The common themes revealed by the thematic analysis were culture and diversity in relation to stories. Of the ten (100%) reviews, five mentioned that the company culture in AMD was good, as the employees were satisfied with the culture within the organisation; however, three (30%) described it as destructive and toxic. Four (40%) mentioned the lack of diversity within AMD, while six (60%) did not mention diversity. A positive comment was made by person A, who said, “There is a good teamwork culture where the employees are helping each other”. This aligns with Alpander and Lee (1995) who argued that having a good company culture and collaboration increases productivity and overall performance. Another positive comment was made by person G, who said “The company is good in terms of inclusiveness for the LGBTQ community”. Negative or semi-negative comments were made by persons E and I, who respectively noted that, “It is a toxic culture” and “it is a good culture, but not many females work here”. Figure 6 demonstrates the lack of females and diversity within AMD. Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 19 Gender percentage of employees in AMD from 2015–2019 80% 76% 71% 76% 76% 76% 60% 40% 29% 24% 24% 24% 24% 20% 0% 2015 2016 Total Male 2017 2018 2019 Total Female Fig. 6 Gender percentage of employees in AMD 2015–2019 (AMD, 2021) The Symbols The common themes regarding symbols that arose from the thematic analysis were balance, flexibility, and dress code. Out of the ten (100%) reviews, three (30%) mentioned a good culture within AMD and a good work-life balance in the sense that the employee can be flexible with where they want to work. In contrast, seven reviews (70%) mentioned an insufficient balance between work and life. Seven (70%) reviews mentioned a casual dress code in AMD, and the lack of rules or regulations on how to dress at work; three (30%) did not mention the dress code. It is known that employees working in the IT industry tend to have a more casual dress code compared to other sectors, and according to Laliberte (2016) this is because it is an industry where you can express who you are with fashion, without limitation. One positive comment (person C) was, “It is a good work-life balance since we are flexible with where we can work as long as we have an internet connection”; however, negative comments were made by persons B, A, and E who said, respectively, “It is hard to balance because of the workload”, “The hours are long and [it is] hard to find a balance between work and personal life” and “It is a stressful environment with a lot of work in a short period”. The Power Structure Management style and turnover were themes revealed in relation to the power structure. Out of ten (100%) reviews, three (30%) mentioned poor senior management, but seven (70%) did not mention management. Six (60%) employees mentioned the high employee turnover among junior staff, whereas four (40%) did not mention turnover. Person H commented that, “Senior managers only think about themselves and keeping their roles in the company rather than helping their team develop and improve”, while person B stated that, “there is not enough focus on hiring qualified employees which can help the company improve”. 20 A. E. Høiås et al. The Organisational Structure The common themes arising from the thematic analysis on authority in relation to organisational structure showed that AMD has a flat hierarchy structure. Lisa Sue is the CEO, and there are executive and senior vice presidents, with 17/19 executives and vice presidents being male and only two female (AMD, 2021b). There is a significant shortage of females in the company, as mentioned before. Out of ten (100%) reviews, four (40%) said there was a culture of politics in the company, and three (30%) mentioned bureaucracy. For example, person H said, “It is a culture of politics where management only thinks about themselves”. The Control System The common themes on the control system were salary and rewards. Out of ten (100%) four (40%) mentioned that the pay was good, while six (60%) said that the salary was terrible. For example, person J said, “The pay is good”, but person G said, “The salary is poor compared to the amount of work the managers expect”. In the same vein, person J said, “The poor salary makes it less motivating to put in the extra work”. Lorens et al. (2011) argued that having a poor salary can make employees less motivated regarding work and performance. Person E’s review stated that the pay was not too bad, but the benefits could have been better. Six (60%) employees said that there were good benefits within the company, but four (40%) said that they were poor. Persons A, G and I stated the salary was bad, but the benefits were good. The Rituals and Routines The common themes in relation to rituals and routines were training and opportunities. Out of ten (100%) reviews, four (40%) said the company had good options for training and growth, while five (50%) said that these were poor. Person C did not mention training or growth. For example, person E said, “There are good opportunities for training and growth in the company”, while person I said, “There are poor opportunities for growth in the company, and the work you do is repetitive”. According to Bartel (1994) there is a significant link between the provision of training for employees and productivity growth, and this might explain the comment made above on high employee turnover and a lack of qualified employees. 12 Analysing the Organisational Culture in Nvidia Using the Cultural Web Model As mentioned previously, Nvidia is a company with more than 13,000 employees worldwide. Below, Table 2 shows the common themes mentioned in the employee reviews of the organizational culture in Nvidia. Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 21 Table 2 Cultural web model analysis of Nvidia Stories • Diversity (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Culture (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Symbols • Balance (Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Flexibility (Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Dress code (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Power structure • Management style (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b) Organizational structure • Leadership team (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Control system • Salary (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) • Benefits (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b Rituals and routines • • • • Training (Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Mentorship (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) Growth (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b) Opportunities (Glassdoor, 2021a, 2021b; Indeed, 2021a, 2021b; Comparably, 2021a, 2021b) The Stories The common themes arising from the thematic analysis in relation to stories were culture and diversity. Out of ten (100%) reviews, four (40%) of the employees said they were satisfied with the culture in Nvidia, whereas five (50%) reviews said there was a culture of politics in Nvidia. Person G did not mention if the culture was good or bad, but did mention a lack of diversity, along with 40% of the employees. Five (50%) did not mention diversity in their reviews. As Figs. 7 and 8 show, there was a significant difference between the male and female employees in the period 2015–2019. Figure 7 shows the lack of female employees in the company, while Fig. 8 shows the lack of females in senior management and the company’s technical roles. For example, person B said, “it is a culture of teamwork and collaboration which is a good thing”. In contrast, person H said, “the culture in Nvidia is terrible” and person J said, “it is a culture of politics and bureaucracy”. The Symbols The common themes from the thematic analysis in relation to symbols were balance and flexibility. Out of ten (100%) reviews, five (50%) said that there was a good work/life balance within the company, while five (50%) employees said there was a poor work/life balance. Seven (70%) employees also said that there was good flexibility within the company, while other reviews did not specify what type of flexibility there was. Seven (70%) of the reviews mentioned long hours, indicating that there was too much work. Three (30%) did not mention the working hours. For example, person C said, “the company has been great with adjusting to Covid-19 and 22 A. E. Høiås et al. Gender percentage of employees in Nvidia from 2015–2019 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 83% 82% 82% 2015 2016 2017 Total Male 81% 19% 19% 18% 18% 17% 81% 2018 2019 Total Female Fig. 7 Gender percentage of employees in Nvidia 2015–2019 (Nvidia, 2020) Employees in Nvidia based on sector and gender in 2019 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 19% Total Male 86% 83% 81% 17% 14% Total Female Management Management Technical Roles Technical Roles Roles Male Roles Female Male Female Fig. 8 Employees in Nvidia based on sector and gender 2019 (Nvidia, 2020) remote working. However, person G said, “the hours are exceptionally long when it is close to a new product launch. It is expected to work 24 h to make a product ready in time close to a launch”. Out of ten (100%) four (40%) employees mentioned no formal dress code in Nvidia. Six (60%) did not mention the dress code. For example, person C said, “we can wear what we want to work, and it is no need to dress formally”. The Power Structure The common themes of the thematic analysis in relation to the power structure were management style. Out of ten (100%) three (30%) said there was a poor senior management team, and four (40%) mentioned the need for better communication between employees and senior managers. Person J emphasised that it took time for employees to receive information. This indicates that six (60%) of the reviews mentioned negative aspects of the management style, with the other four (40%) Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 23 Senior management roles by gender in Nvidia in percentage from 2018–2020 100% 83% 84% 83% 80% 60% 40% 17% 20% 17% 16% 0% 2018 Senior Management Male 2019 2020 Senior Management Female Fig. 9 Senior management roles by gender in Nvidia 2018–2020 (Nvidia, 2020) not mentioning anything. Comments in this regard are exemplified by: person E, who said, “the management team are not any helpful”; person B, who said, “the communication is terrible”; and, person J, who said, “it takes time before we get any information from the managers”. The Organisational Structure The common theme in the thematic analysis in relation to organisational structure was authority. Jensen Huang is the CEO of Nvidia, and the leadership team is based on four officers, two of whom were female and two male in 2018–2020. At the same time, the board of directors was based on 13 people, three of whom were female. Figure 9 shows the difference in senior management roles in Nvidia between 2018– 2020. A significant gap can be seen here between males and females. In the ten reviews (100%) four (40%) mentioned a lack of diversity and five (50%) said there was a culture of politics (Fig. 9). The Control System The common themes arising from the thematic analysis in relation to the control system were reward and salary. Out of ten reviews (100%) nine (90%) said that the salaries were satisfactory, but person G said that the salary was inadequate. However, 100% of the reviews said they were satisfied with the company’s benefits. Comments made in this regard are illustrated by person D, who said, “I am satisfied with the benefits because Nvidia does offer medical advice and care access if we need that”. Many offices also do provide onsite services such as laundry and car maintenance (Nvidia, 2021a, 2021b). The Rituals and Routines The common themes in the thematic analysis in relation to rituals and routines were training and opportunities. Out of ten reviews (100%) five (50%) mentioned good opportunities for training and growth in Nvidia. Seven (70%) said that they were satisfied with the mentor arrangement Nvidia provides, while two (20%) said that this arrangement was good if you had a mentor who provided you with the help you 24 A. E. Høiås et al. needed. For example, person B said, “Nvidia does offer training if the employee wants this”, but person G said, “there are not enough opportunities for training and growth”. 13 Comparing the Organisational Culture in AMD and Nvidia As Table 3 shows, there are some similarities and differences between AMD and Nvidia according to the cultural web model. AMD and Nvidia are similar regarding stories, symbols, power structure, and organisational structure, but different on the control system and rituals and routines. It is clear that both companies had a gender gap both for employees and those in management. Based on the reviews, AMD’s employees seemed more dissatisfied than Nvidia’s, possibly because the latter’s employees were more satisfied with their salary, benefits, and better access to personal development. Based on the employee reviews, those giving a negative review tended to be negative on all the analysed aspects, potentially indicating that the employee does have a generally negative attitude towards to company. In contrast, those employees who gave positive reviews tended to have a more positive attitude towards the company. In contrast, those employees who gave positive reviews tended to have a more positive attitude towards the company, as shown in Appendices 1–2. Based on these findings, there is no significant connection between the organisational culture in AMD and Nvidia and gender discrimination, despite the identification of a lack of diversity within both organisations. The study also identified a gender gap in the management and technological sectors in the companies, but there is no Table 3 Comparison of the cultural web model findings of AMD and Nvidia Similarities Differences Stories • Lack of diversity • Culture of politics • Culture of teamwork (AMD) Symbols • Poor work/life balance • Long hours • Casual dress code • Good flexibility (AMD) Power structure • Poor senior management • High turnover (AMD) • Favouritism amount managers (AMD) • Poor communication (Nvidia) Organizational structure • Flat hierarchy • Poorly diverse leadership team Control system Rituals and routines • Good benefits • Poor salary (AMD) • Good availability for training and growth (Nvidia) • Good mentorship programme (Nvidia) Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 25 evidence showing this to be due to the companies’ organisational culture. Although little research has been conducted on how a company’s organisational culture may be connected to gender inequality, a few studies have revealed the lack of diversity within companies operating in the technology industry, demonstrating that companies are male dominated, challenging environments for females. These findings may explain why there is a lack of diversity in AMD and Nvidia. However, the data used in this study do not provide this information explicitly in the employee reviews. 14 Conclusions Research suggests that it is necessary for women to experience career equality with gender-inclusive climates (Kossek et al., 2003) and so the first recommendation for both companies would be to reduce their gender gap by actively and specifically encouraging females to apply for jobs in their company. AMD has created AMD Research, which is their attempt “to build a culture of inclusion [and] expand beyond the company walls” (AMD, 2021a). These activities support early-year graduate students and help women and under-represented minorities enter the technology industry (AMD, 2021a). In both companies, having a more diverse management team could also reduce some of the difficulties employees may experience. As mentioned in the literature review section, having females in top management roles results in higher earnings and better shareholder wealth. Males and females view the purpose of conversations differently (Merchant, 2012). Females use communication as a device to develop social connections and build a relationship, while males use language to exert dominance and achieve tangible outcomes (Leaper, 1991; Maltz & Borker, 1982). Burns (1978) argues that females tend to use the transformational leadership style, which encompasses inspirational and visionary leaders who gain their employees’ trust and confidence. This has been done by creating shared goals and setting plans for employees to achieve these goals. Therefore, it is necessary to have both males and females in a company. A common factor in both AMD and Nvidia was the lengthy working hours, indicating that workloads for employees were potentially too great and that more people needed to be recruited. Recruiting more employees would also allow AMD and Nvidia to decrease the gender gap and employ more females. Another recommendation on increasing overall employee satisfaction in AMD would be to increase the company’s benefits. None of the employees mentioned in their reviews that AMD has a mentorship programme as does Nvidia, and indeed AMD employees were less satisfied with training and growth opportunities compared to Nvidia. Establishing a mentorship programme could help the employees increase their personal skills and knowledge, which will also improve AMD’s overall performance. This section has looked at the organisational culture in AMD and Nvidia using the cultural web model. The findings show that AMD and Nvidia had similarities and 26 A. E. Høiås et al. differences in their organisational culture. A common theme for both companies was the lack of diversity and a gender gap in employee and management positions. As yet, no findings show that this is linked to the organisational culture. Recommendations were provided on how AMD and Nvidia can improve their overall organisational culture and decrease their respective gender gaps. The analysis also showed that there was lack of diversity and a lack of females in management and technical roles, respectively. However, the analysis does not indicate that this was because of the organisational culture in AMD or Nvidia. None of the reviews mentioned that the lack of diversity was because of the organisational culture. This lack of diversity might be because of factors mentioned earlier, such as the lack of female applicants for jobs. Another factor may be that the technology industry is known for being heavily male dominated, and therefore females do not want to work within this industry. This analysis revealed no indication that the lack of diversity was because of the organisational culture or the employees within the companies. Being more positive, the employees in AMD did say there was a culture of teamwork and collaboration. Employees in Nvidia said it had a good mentor programme and opportunities for growth within the company. This could indicate that the lack of females in management positions was because of the general lack of females in the company, as the analysis has shown. Acknowlegements Being more positive, the employees in AMD did say there was a culture of teamwork and collaboration. Employees in Nvidia said it had a good mentor programme and opportunities for growth within the company. Appendix Appendix 1: 10 Employee Review of AMD Person A • Good culture – Good teamwork • Lack of diversity • Poor w/l balance • Poor salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility • Good opportunities • Stressful environment • Casual dress code Person B • Good culture • Lack of diversity • Poor w/l balance • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility • Good opportunities • Stressful environment • Casual dress code • High turnover – Not hiring enough qualified people Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … Person C • Good culture • Good w/l balance – Good teamwork • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility • Casual dress code • Inclusive for LGBTQ Person D • Good culture – Good teamwork • Good w/l balance • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility • Good opportunities • Casual dress code Person E • Good culture • Good w/l balance • Good salary – Not too bad • Bad benefits – Could been better • Good flexibility • Good opportunities • Stressful environment Person F • Toxic culture • Hired/promoted by network • Poor w/l balance • High turnover • Culture of politics • Bad salary • Bad benefits • Poor flexibility • Poor opportunities • Casual dress code Person G • Toxic culture • Hired/promoted by network • Poor w/l balance • Poor senior management • High turnover • Culture of politics • Bad salary • Good benefits • Poor flexibility • Poor opportunities • Casual dress code Person H • Toxic culture • Poor w/l balance • Poor senior management – Only thinking about themselves • Managers favouriting • High employee turnover • Culture of politics • Bad salary • Bad benefits • Poor flexibility • Poor opportunities • Casual dress code Person I • Lack of diversity • Hired/ promoted by network • Poor w/l balance • Poor senior management • Managers favouriting • Bad salary – Less motivating • Good benefits • Poor flexibility • Poor opportunities • High turnover Person J • Lack of diversity • Hired/ promoted by network • Poor w/l balance • Culture of politics • Bad salary – Less motivating • Bad benefits • Poor flexibility • Poor opportunities • Stressful environment • High turnover 27 28 A. E. Høiås et al. Appendix 2: 10 Employee Review of Nvidia Person A • Good culture • Lack of diversity • Good w/l balance • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility • Good opportunities • Good mentoring Person B • Good culture – Teamwork/collaboration • Poor w/l balance • Long hours • Poor communication • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility • Good opportunities • Good mentoring Person C • Good culture • Good w/l balance • Long hours • Casual dress code • Wear what you want • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility – remote • Good opportunities • Good mentoring Person D • Good culture • Poor w/l balance • Long hours • Good salary • Good benefits • Medical help • Good flexibility • Good opportunities • Good mentoring Person E • Toxic culture • Lack of diversity • Poor w/l balance • Casual dress code • Long hours • Poor senior management • Culture of politics • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility • Good opportunities • Good mentoring Person F • Lack of diversity • Good w/l balance • Poor senior management • Culture of politics • Organization with bureaucracy • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility • Good mentoring Person G • Lack of diversity • Poor w/l balance • Long hours – Especially close to launch • Poor senior management • Poor communication • Culture of politics • Bad salary • Good benefits • Poor flexibility • Poor opportunities • Poor mentoring Person H • Poor w/l balance • Long hours • Casual dress code • Culture of politics • Organization with bureaucracy • Good salary • Good benefits • Poor flexibility • Good mentoring Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … Person I • Good w/l balance • Long hours • Good salary • Good benefits • Good flexibility 29 Person J • Good w/l balance • Culture of politics • Casual dress code • Organization with bureaucracy • Good salary • Good benefits • Poor flexibility • Poor mentoring • Poor communication • Long time to get down the chain References Alfrey, L., & Twine, F. (2016). Gender-fluid geek girls: Negotiating inequality regimes in the tech industry. Gender and Society, 31(1), 28–50. Allaire, Y., & Firsirotu, M. E. (1984). Theories of organizational culture. Organization Studies, 5, 193–226. Alpander, G. G., & Lee, C, R,. (1995). Vulture, strategy and teamwork: The keys to organizational change. Journal of Management Development, 14(8), 4–18. AMD. (2021a). Innovation is at the core of AMD. https://www.amd.com/en/corporate/research-div ersity-inclusion. [4th February 2021]. AMD. (2021b). Labor performance indicators. https://www.amd.com/en/corporate-responsibility/ governance-data-tables. [3rd February 2021]. AMD. (2021c). AMD executive team. https://www.amd.com/en/corporate/leadership. [11th March 2021]. Arun, A., & Bryony, R. (2015) Melting pot or salad bowl: The formation of heterogeneous communities. IFS Working Papers. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. Bartel, A. B. (1994). Productivity gains from the implementation of employee training programs. Industrial Relations, 33, 411–425. Blickenstaff, J. K. (2005). Women in science careers: Leaky pipeline or gender filter? Gender and Education., 17(4), 369–386. Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row New York. Business Insider. (2021). The 31 best tech companies to work for in 2020, according to employees. https://www.businessinsider.com/best-tech-companies-to-work-for-2020-glassdoor2019-12?r=US&IR=T. [2nd March 2021]. Campbell, D., & Stonehouse, G. (1999). Business strategy (pp. 47–48). Butterworth Heinemann. Carter, R., & Kirkup, G. (1990). Women in engineering: A good place to be? Macmillan. Cartwright, S., & Cooper, C. L. (1993). The role of culture compatibility in successful organizational marriage. Academy of Management Executive, 7, 57–70. Cejka, M. A., & Eagly, A. H. (1999). Gender-stereotypic images of occupations correspond to the sex segregation of employment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 413–423. Center for American Progress. (2018). The women’s leadership gap. https://www.americanprog ress.org/issues/women/reports/2018/11/20/461273/womens-leadership-gap-2/. [10th December 2020]. 30 A. E. Høiås et al. Chatterjee, S., Lubatkin, M. H., Schweiger, D. M., & Weber, Y. (1992). Cultural differences and shareholder value in related mergers: Linking equity and human capital. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 319–334. Coates, R. D. (2011). Covert racism: Theories, institutions, and experiences. Chicago: Haymarket Books. Cockburn, C. (1991). In the way of women: Men’ s resistance to sex equality in organizations. Ithaca, New York: ILR Comparably. (2021a). AMD. https://www.comparably.com/companies/amd. [1st February 2021]. Comparably. (2021b). Nvidia. https://www.comparably.com/companies/nvidia/manager. [1st February 2021]. Dasgupta, N., & Asgari, S. (2004). Seeing is believing: Exposure to counter stereotypic women leaders and its effect on the malleability of automatic gender stereotyping. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 642–658. Dauber, D., Fink, G., & Yolles, M. (2012). A configuration model of organizational culture. SAGE Open, 2(1), 1–16. Doherty, O., & Stephens, S. (2019). The cultural web, higher education and work-based learning. Industry and Higher Education, 34, 330–341. Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Erlbaum. Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (1984). Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 735–754. Eisenhart, A., & Finkel, E. (1998). Women’s science: Learning and succeeding from the margins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Equality and Human Rights Commission. (2021). Sex discrimination. https://www.equalityhuma nrights.com/en/advice-and-guidance/sex-discrimination. [27th January 2021]. Faulkner, W. (2000). The power and the pleasure? A research agenda for “making gender stick” to engineers. Science, Technology and Human Values, 25(1), 87–119. Forbes. (2021). The world’s best employers 2020 list. https://www.forbes.com/lists/worlds-bestemployers/#36b225a91e0c. [2nd March 2021]. Ford, R., & Richardson, W. (1994). Ethical decision making: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Business Ethics., 13(3), 205–221. Freemantle, D. (2013a). Part 1 - The cultural web- a model for change in maternity services. British Journal of Midwifery, 21(9). Freemantle, D. (2013b). Part 2- applying the cultural web. changing the labour ward culture. British Journal of Midwifery, 21(10). Glassdoor. (2021a). AMD. https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/Overview/Working-at-AMD-EI_IE15. 11,14.htm. [1st February 2021]. Glassdoor. (2021b). Nvidia. https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/Overview/Working-at-NVIDIA-EI_IE7 633.11,17.htm. [1st February 2021]. Goldsmith, P., & Romero, M. (2008). Aliens, illegals, and other types of Mexicanness: Examination of racial profiling in border policing. In Hatter, A., Embrick, D., & Smith, E. (Eds.), Globalization and America: race, human rights, and inequality. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Handy, C. B. (1993a). Understanding organizations (4th ed.). London-UK: Penguin Books Ltd. Handy, C. B. (1993b). Understanding organizations. Oxford University Press. Handy, C. B. (1996). Gods of management: The changing work of organizations. Oxford University Press. Hatch, M. J. (1993). The dynamics of organizational use technology analysis and strategic culture. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 657–693. Heilman, M. E. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 113–135. Hofstede, G., Neuijen, B., Ohayv, D. D., & Sanders, G. (1990). Measuring organizational cultures: A qualitative and quantitative study across twenty cases. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 286–316. Hofstede, G. (1997). Culture and organisations: Software of the mind: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. McGraw-Hill Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 31 Hofstede Insights. (2021) Organizational culture. https://hi.hofstede-insights.com/organisationalculture. [28th January 2021]. Igi Global. (2021). What is national culture. https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/national-cul ture-and-the-social-relations-of-anywhere-working/19905. [28th January 2021]. Iljins, J., Skvarciany, V., & Gaile-Sarkine, E. (2015). Impact of organizational culture on organizational climate during the process of change. Procedia- Social and Behavioral Sciences, 213(1), 944–950. Indeed. (2021a). AMD. https://uk.indeed.com/cmp/Amd/reviews?fcountry=ALL. [1st February 2021]. Indeed. (2021b). Nvidia. https://uk.indeed.com/cmp/Nvidia/reviews?fcountry=ALL. [1st February 2021]. Isaac, M. (2015). Behind Silicon Valley’s self-critical tone on diversity, a lack of progress. https://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/06/28/new-diversity-reports-show-the-same-oldresults/. [13th January 2021]. Jeffs, T., & Morrison, W. (2005). Special education technology addressing diversity: A synthesis if the literature. Journal of Education Technology, 20(4), 19–25. Johnson, G. (1988). Rethinking incrementalism. Strategic Management Journal, 9(1), 75–91. Johnson, G., & Scholes, K. (1999). Exploring corporate strategy (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. Johnson, G., Scholes, K., & Whittington, R. (2008). Exploring corporate strategy: Text and cases (8th ed.). England. Johnston, L., & Hewstone, M. (1990). Intergroup contact: Social identity and social cognition. In Abrams, D., & Hogg, M. A. (Eds.), Social identity theory: Constructive and critical advances (pp. 185–210). New York, NY: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Jorgenson, J. (2002). Engineering selves: Negotiating gender and identity in technical work. Management Communication Quarterly, 15(3), 350–380. Khatib, T. M. (1996). Organizational culture, subcultures, and organizational commitment. Iowa State University Digital Repository. Kilmann, R., Saxton, H., & Serpa, M. R. (1986). Introduction: Five key issues in understanding and changing culture. California Management Review, 28(2), 87–94. Kossek, E,E., Markel, K., & McHugh, P. (2003). Increasing diversity as an HRM change strategy. Journal of organizational change management 16(3), 328–352. Kvande, E. (1999). In the belly of the beast: Constructing femininities in engineering organizations. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 6(3), 305–328. Laliberte, K. (2016). Factory PR: where employees love their dress code: for the employees at the cutting-edge fashion and tech agency factory PR, there is a dress code, but it is all about self-expression (within limits). https://search.proquest.com/docview/1818457920/C3BFDA571 E5C41EBPQ/3?accountid=10286. [15th March 2021]. Leaper, C. (1991). Influence and involvement in children’s discourse: Age, gender, and gender differences in leadership 59 partner effects. Child Development, 62, 797–811. Llorens, J., Stazyk, J., & Edmund, C. (2011). How important are competitive wages? Exploring the impact of relative wage rates on employee turnover in State government. Public Personnel Administration, 31(2), 111–127. Lundy, O., & Cowling, A. (1996). Strategic human resource management. Routledge. Malik, A. (2020). My internship at AMD. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=60shM6VGRjA. [27th January 2021]. Maltz, D. N., & Borker, R. (1982). A cultural approach to male-female miscommunication. In J. J. Gumpertz (Ed.), Language and social identity. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press. Marcoulides, G. A., & Heck, R. H. (1993). Organizational culture and performance: Proposing and testing a model. Organization Science, 4(2), 209–225. Martins, E., & Terblanche, F. (2003) Building organizational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 6(1), 64–74. McGuire, M. (2012). Examining culture. https://agents2change.typepad.com/blog4/2012/01/exa mining-culture-6-thats-just-the-tip-of-the-iceberg.html. [13th January 2021]. 32 A. E. Høiås et al. McIlwee, J, S., & Robinson, G, J. (1992). Women in engineering: Gender, power and workplace culture. Albany: State university of New York Press. McIlwee, J., & Robinson, J. G. (1992). Women in engineering: Gender, power and workplace culture. State University of New York Press. Merchant, K. (2012). How men and women differ: Gender differences in communication styles, influence tactics and leadership styles2. CMC Senior theses. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ cmc_theses/513. [15th March 2021] Meyer, A. D., Tsui, A. S., & Hinings, C. R. (1993). Configurational approaches to organizational analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1175–1195. Morris, J. P. (2018). IS this culture of academies? Utilizing the cultural web to investigate the organizational culture of an academy case study. Education Management Administration and Leadership., 48(1), 164–185. Nvidia. (2019). Social responsibility report 2018. https://www.nvidia.com/content/dam/en-zz/Sol utions/documents/FY2018-NVIDIA-CSR-Social-Responsibility.pdf. [3rd February 2021]. Nvidia. (2021a). Corporate social responsibility report 2020. https://www.nvidia.com/content/dam/ en-zz/Solutions/documents/FY2020-NVIDIA-CSR-Social-Responsibility.pdf. [2nd February 2021]. Nvidia. (2021b). About us. https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/about-nvidia/benefits/. [15th February 2021]. Ortega-Parra, A., & Sastre-Castillo, M. (2013) Impact of perceived corporate culture on organizational commitment. Management Decision, 51, 1071–1083. Pederson, J, S., & Sorensen, J. S. (1989). Organizational culture in theory and practice. England. Gower Publishing Co. Pope, C., Ziebland, S., & Mays, N. (2006). Analyzing qualitative data. In C. Pope & N. Mays (Eds.), Qualitative research in health care (3rd ed., pp. 63–81). Blackwell Publishing. Robbins, S. P. (1996). Organizational behavior: Concepts, controversies, applications (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall. Russell-Brown, K. (2009). The color of crime: Racial hoaxes, white fear, black protectionism, police harassment, and other macroaggressions (2nd ed.). New York University Press. Sagiv, L., & Schwartz, S. H. (2007). Cultural values in organizations: Insights for Europe. European Journal of International Management, 1, 176–190. Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2016) Research Methods for Business Students (7th ed.). Harlow: Pearson. pp. 144–151. Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass. Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture. American Psychologist, 45(2), 109–119. Schilt, K. (2006). Just one of the guys: How transmen make gender visible at work. Gender and Society., 20(4), 465–490. Schilt, K. (2011) Just one of the guys? Transgender men and the persistence of gender inequality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Schneider, S. C., & Barsoux, J. L. (1997). Managing across cultures. Prentice Hall. Simoneaux, S., & Stroud, C. (2014). A strong corporate culture is key to success. Journal of Pension Benefits, 22(1), 51–53. Statista. (2021a). AMD’s net revenue from 2001 to 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/267 872/amds-net-revenue-since-2001/. [11th January 2021]. Statista. (2021b). Intel’s net revenue from 1999 to 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/263559/ intels-net-revenue-since-1999/. [11th January 2021]. Statista. (2021c) AMD’s quarterly revenue worldwide from 2009 to 2020. https://www.statista.com/ statistics/272972/amds-net-revenue-since-q1-2009-per-quarter/. [2nd February 2021]. Steedle, J., & Zahner, D. (2015). Comparing longitudinal and cross-sectional school effect estimates in postsecondary education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED582107.pdf. [12 February 2021]. Sullivan, A., Abraham, M., & Amiot, M. (2021). The changing face of tech. https://www.spglobal. com/en/research-insights/featured/the-changing-face-of-tech. [3rd February 2021]. Organisational Culture and Gender Stereotypes … 33 Sun, S. (2008). Organizational culture and its themes. International Journal of Business and Management, 3(12), 137–141. Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (2003). Studying organizational cultures through rites and rituals. Academy of Management Review, 9(4), 653–669. Weber, R., & Crocker, J. (1983). Cognitive processes in the revision of stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 961–977. Weber, Y., & Tarba, S. (2012). Mergers and acquisitions process: The use of corporate culture analysis. Cross Cultural Management, 19, 288–303. Welbourne, T. (1999). Wall Street like female: An examination of female in the top management teams of initial public offerings. Center for advanced human studies (Working Paper 1999–0). Cornell University. Wells, G. (2016). Tech companies delay diversity reports to rethink goals. https://www.wsj.com/ articles/tech-companies-delay-diversity-reports-to-rethink-goals-1480933984. [13th January 2021]. White, G. (2017). Melinda Gates: The tech industry needs to fix its gender problem – now. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/03/melinda-gates-tech/519762/. [8th January 2021]. World Economic Forum. (2021). Global gender gap report 2020. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/ WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf. [2nd March 2021]. Zimmermann, K. A. (2017). What is culture. https://www.livescience.com/21478-what-is-culturedefinition-of-culture.html. [27th January 2021]. Anniken Emilie Høiås is currently studying for a master’s degree at the Hult international business school and working for the College of West Anglia as a commercial trainer in business and management. She has completed her bachelor degree from Coventry university in international business management. She has previously worked at companies like Enterprise Rent-A-Car and Fave. Her research interest is in Cultural Differences in Organizations, and how this impacts the organization culture. The research idea came after her interests of traveling and fascination of culture and cultural differences in organizations, and their impact on the operations. Naznin Tabassum is currently working as a Senior Lecturer and BA (hons) Business Management Programme Leader (Year-3) at the University of Derby, Derby, UK. She is a gender researcher. She worked in universities in Coventry, Teesside, Newcastle, Bradford and Leeds for last eight years. Her research interests consist of five interrelated subject areas i.e. (i) Women in management/leadership/Women entrepreneurs and Gender stereotyping, (ii) Resilience, (iii) Liberal, radical and moderate feminism, (iv) Corporate Governance and CSR, (v) Corporate Prostitution. The main focus of her research is the impact of gender stereotyping on women career progression in South East Asia. She is author of book chapter like; Women entrepreneurs in Libya: a stakeholder perspective; and journal articles like; ‘Gender stereotypes and their impact on women’s career progressions from a managerial perspective’, ‘Antecedents of women manager’s resilience: conceptual discussion and implications for HRM’ and ‘The impact of gender stereotyping on female expatriates; A conceptual model of research’. Bhabani Shankar Nayak is a political economist working as Professor of Business Management, University for the Creative Arts, UK. He worked in the universities in Sussex, Glasgow, Manchester, York and Coventry for last eighteen years. His research interests consist of four closely interrelated and mutually guiding programmes i.e. (i) political economy of sustainable development, gender and environment in South Asia, (ii) market, microfinance, religion and social business, (iii) faith, freedom, globalisation and governance and (iv) Hindu religion and capitalism. The regional 34 A. E. Høiås et al. focus of his research is on the impacts of neoliberalism on social, cultural and economic transition of indigenous and rural communities in South Asia. He is the author books like; ‘Nationalising Crisis: The Political Economy of Public Policy in India’, ‘Hindu Fundamentalism and Spirit of Capitalism in India’ and ‘Disenchanted India and Beyond: Musings on the Lockdown Alternatives’, China: The Bankable State (2021).