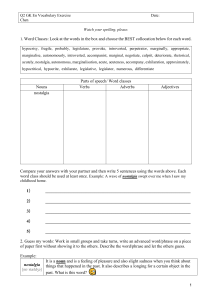

Article Nostalgia and pastiche in the post-postmodern zeitgeist: The ‘postcar’ from Italy Marketing Theory 2020, Vol. 20(4) 481–500 ª The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1470593120942597 journals.sagepub.com/home/mtq Luigi Cantone Federico II University of Naples, Italy Bernard Cova Kedge Business School, France Pierpaolo Testa Federico II University of Naples, Italy Abstract The transition towards a post-postmodern zeitgeist has attracted much scholarly attention over the last decade, highlighting the major traits of the coming post-postmodern condition, such as sincerity challenging irony, reconstruction despite paradoxes, hope despite difficult circumstances and structure counterbalancing anti-structure in lived experience. Nevertheless, we know little about what is happening with regard to nostalgia, a key characteristic of postmodernity, especially in terms of one of its major components, pastiche. From the start of the 1990s, marketing research on postmodern nostalgia and pastiche has largely focused on different models of cars. Through an interpretive analysis focusing on the dual comeback of an Italian car, the Giulia, this article aims to investigate the existence and forms that nostalgia and pastiche take under the new zeitgeist. It highlights a mutation of nostalgia that is becoming regenerative. The major consequence of this is the changing nature of pastiche, from stylistic to essentialist. Our understanding of the coming zeitgeist has also improved: in addition to confirming the major features of post-postmodernity already established in the literature, this study argues that the possibility of a (mini)miracle is another key feature of our times. Keywords Italy, miracle, nostalgia, pastiche, postmodern, zeitgeist Corresponding author: Bernard Cova, Department of Marketing, Kedge Business School, Domaine de Luminy, BP 921, 13288 Marseille Cedex 9, France. Email: bernard.cova@kedgebs.com 482 Marketing Theory 20(4) Introduction Postmodern is dead (Brown, 2016b)! The demise or decline of postmodernity has been acknowledged by marketing theorists ‘as reflecting a shift in zeitgeist that renders postmodernism anachronistic’ (Cova et al., 2013: 214). In its wake, knowledge of the post-postmodern zeitgeist has been advanced and enriched by numerous researchers. However, we know little about what happens within this new zeitgeist to a key characteristic of postmodernity (Jameson, 1985) that has fuelled retromarketing and retrobranding approaches over the last two decades (Brown, 1999; Brown et al., 2003): nostalgia! And we know even less about one of the most significant practices of postmodernity associated with nostalgia, namely ‘pastiche’ (Goulding, 2000), used in marketing mainly through the ‘grotesque’ combinations of past offerings (Brown, 2013). Does the postpostmodern zeitgeist discard nostalgia or does it alter it? And what happens to pastiche? Is it still a prominent practice under a post-postmodern zeitgeist or will it disappear from the foreground? These questions are not just academic mind-breakers. Nostalgia and pastiche have been – and for some are still – widely mobilized by Western companies in their offerings, namely in the contemporary television, film, advertising and photography industries (Niemeyer, 2014). Through an analysis of the conjunction of the launch of a brand new Giulia model and the success of a movie starring the old 1960s Giulia in the very same year (2015) and in the same country (Italy), we show that the decline of postmodernity has not to be equated with the demise of nostalgia: quite the contrary (Cervellon and Brown, 2018b). However, we also show that the transition of the zeitgeist is not without impact on the meaning of nostalgia and especially on the practice of pastiche that has mutated from stylistic to essentialist. The key features of the post-postmodern zeitgeist The beginning of the last decade was marked by several works, both within (Cova et al., 2013) and outside marketing (Fjellestad and Engberg, 2013), which suggested that postmodern culture – beginning more or less in the 1970s – had come to an end. These works propagated the terminology of ‘post-postmodernism’ to label the contemporary zeitgeist and proposed three major features characterizing it: enthusiasm, engagement and sincerity. Beyond this pioneering big picture of the shift towards the post-postmodern, we can look now, at the close of the decade, to a series of empirical works that allow a better understanding of the post-postmodern zeitgeist and even to envision how consumer culture has changed – or could do so – as a result. Research in the fields of popular culture (Canavan and McCamley, 2020; Fjellestad and Engberg, 2013), television fictions and novels (Doyle, 2018; Frangipane, 2016), consumer experience (Cronin et al., 2014; Skandalis et al., 2016, 2019) and tourism (Thomas et al., 2018) have provided us with some clues to understand the post-postmodern condition. A first bulk of research is based on the textual analysis of novels or songs, plus some contextual evidence regarding the life of the authors. They highlight how authors as producers of texts have taken a new stance that can be characterized by three main features. The first feature is sincerity. In a post-postmodernist sensibility (Doyle, 2018), postmodernist irony should be shunned, as it makes it impossible to engage in a meaningful and sincere way with reality or express emotion with sincerity. The seminal work of Fjellestad and Engberg (2013) highlights the differences between the postmodern Madonna and the post-postmodern Lady Gaga. Lady Gaga represents many postmodern tropes that, for many, make her the inheritor of the Madonna lineage (Canavan and McCamley, 2020). However, while performance, for Madonna, is Cantone et al. 483 about professionalism – slick, perfect, ironic and managed – for Lady Gaga, it is about blood and guts, stumbles and falls, life and death (Fjellestad and Engberg, 2013). Lady Gaga is ‘always on stage’, living her art sincerely, grafting it into the visceral immediacy of life rather than playing with ironic citation and distance. Doyle (2018: 259) suggests, on the basis of his study of recent fictions such as Nathan Hill’s The Nix, that ‘socially and culturally aware post-postmodern fiction must therefore exist in a constant state of questioning – sincerity challenging irony and irony challenging sincerity’. The second feature is the existence of hope despite difficult circumstances. Frangipane (2016: 522), studying contemporary novelists, demonstrates that they ‘are writing novels that acknowledge our lack of epistemological certainties’ but try to tell stories that anyway restore hope in their readers. The effect of this difference is clear: at the end of a typical postmodern novel, the character is feeling suicidal, while at the end of a post-postmodern one, the character is feeling connected. Doyle (2018: 8) notes that in the novel The Nix (Hill, 2017) the author wants to explore the situations in which his characters find themselves, searching for redemption in the most vapid of circumstances. Every scathing attack and satirical jab is followed by a humanizing counter-punch, so that the book’s benevolence becomes the persevering force. However, this sympathetic view of personal circumstances in no way mitigates criticism of larger forces. Indeed, many people feel torn in post-postmodern times. Remaining hopeful may feel like a futile use of energy, but at the same time, people are unwilling to live in a state of hopelessness. The third feature is reconstruction. Returning to the polarity between Madonna and Lady Gaga’s texts but adding Taylor Swift’s, Canavan and McCamley (2020) consider Lady Gaga as a halfway house between Madonna’s deconstructive and Taylor’s reconstructive selves. Using Taylor Swift, who reimagines herself through shared socially told fabulations as a post-postmodern paragon, they show how her lyrics are marked by ‘new reconstructions of fragments that can be socially told and retold [ . . . ] and in so doing re-reconstructed into evolving agglomerations’ (Canavan and McCamley, 2020: 223). What is key here is the notion of reconstructive sensibility facilitated by communality: ‘Taylor’s prioritisation of oneself amongst a supporting cast denotes her understanding of reconstruction as facilitated by communality’ (Canavan and McCamley, 2020: 228). The postdeconstructive stance thus opens up to a reconstructive movement (Cervellon and Brown, 2018b). A second bulk of research is based on interviews on food and gaming experiences as well as the ethnography of festival and pilgrimage experiences. They highlight how consumers, as producers of experience, have taken a new stance that can be characterized by two additional features. The fourth feature is reconstruction despite the paradoxes. On the basis of their study of an online gaming community, Skandalis et al. (2016) show how post-postmodern consumers play unhesitatingly with the opposing poles of individualism and tribalism during the same consumption experience, ‘a performance in line with the reconstructive spirit of the postpostmodern discourse’ (p. 1322). The same negotiation is also found by Cronin et al. (2014: 386) in their study of women attempting to negotiate the two opposite poles of the past and present through the use of food: ‘Through their ability to perform unification of paradoxical behaviors, women can improvise and tailor the types of femininity that suit them’. In the same vein, Thomas et al. (2018) highlight the duality of Lourdes pilgrims, which lies in the freedom of the individuals and their need for experiences grounded in a socio-historical ‘truth’. If postmodernism represents deconstruction because of paradoxes, then post-postmodernism suggests reconstruction despite the paradoxes. 484 Marketing Theory 20(4) Table 1. Five inter-related contrasting features. Modern condition Postmodern condition Sincerity Irony h Trust in the future Scepticism h Construction (progress) Deconstruction h Construction without paradoxes Deconstruction due to paradoxes h Structure dominant within an experience Anti-structure dominant within an experience h Post-postmodern condition Sincerity challenging irony h Hope despite difficult circumstances h Reconstruction h Reconstruction despite paradoxes h Structure counterbalancing antistructure in an experience h The fifth feature is the counterbalancing of anti-structure by structure in experience. Skandalis et al. (2016: 1320) underline the changing nature of experiences of consumption in postpostmodern culture, emerging ‘through a consideration of consumers’ playful and creative engagement with transitional objects in the context of everyday life’. This is complemented by Skandalis et al. (2019: 49) in their study of a Spanish festival experience showing that consumers ‘are not looking for an escape from everyday life through their participation, instead they embrace these tensions and accept the everyday nature of this festival experience’. The same type of reluctance to the quest of anti-structure is noted by Thomas et al. (2018) in their study of Lourdes pilgrimages. The sustainable coexistence of structure and anti-structure leads to the creation of meaningful consumer experiences. Whereas postmodern consumption experiences ‘are framed as in opposition to or an escape from structure’ (Tumbat and Belk, 2011: 46), the intertwining of structural and anti-structural is highly visible in the two studies of post-postmodern experiences. Research carried out over the last decade has made it possible to build on the ideas of Cova et al. (2013) involving major ideological directions connected with this post-postmodern condition, namely enthusiasm, engagement and sincerity. Enthusiasm has taken the shape of hope despite difficult circumstances. Engagement is clearly visible in all the reconstruction projects, and sincerity appears central to the post-postmodern zeitgeist. In addition, reconstruction despite the paradoxes and the predominant role given to structure in experience make it possible to complete a model for the post-postmodern condition in terms of five key features (Table 1). What happens to nostalgia? While there are several points of contact between all the works we have examined that touch upon the post-postmodern zeitgeist, it is striking that only one paper addresses, in passing, the topic of nostalgia. Indeed, Canavan and McCamley’s (2020) study on the lyrics of prominent pop artists is the only one to notice a new form assumed by nostalgia. The authors highlight Taylor Swift’s ‘prospective remembering of future relationships’ (p. 228) and emphasize the way her lyrics foster Cantone et al. 485 a sense of nostalgia in reverse for young teen girls. Canavan and McCamley (2020) label the way genuine relationship experiences are fused with multiple hypothetical takes on these as ‘reverse nostalgia’, and they connect this reverse nostalgia with the post-postmodern reconstructive stance. This lack of concern for post-postmodern nostalgia is all the more surprising if we consider the role taken on by nostalgia in the postmodern era. Nostalgia has been considered a key characteristic of postmodernism (Jameson, 1985). Indeed, postmodernism has been mainly defined by a nostalgic, conservative longing for the past (Denzin, 1991); a kind of nostalgic tendency to escapism (Hutcheon, 2003). The postmodern version of nostalgia was above all ‘a celebration of styles, images and consumer items associated with the past, or with a particular past’ (Higson, 2014: 128). One could even say that the postmodern actually perverted nostalgia to its own ironic ends and generated a kind of ‘neo-nostalgia’ (Brown, 1999: 365). What remains today of this neo-nostalgia? Has nostalgia mutated into reverse nostalgia? Or something else? Has this key feature of the postmodern era disappeared? Or does it remain unchanged? As Cervellon and Brown (2018a: 394) state, ‘regardless of the rationale, there’s no denying that nostalgia is now the norm’. So does nostalgia differ in postpostmodern times? And if so, how does it differ? Beyond the hypothesis of ‘reverse nostalgia’ advanced by Canavan and McCamley (2020), we build on Cervellon and Brown’s standpoint (2018b: 5) to investigate whether there is a difference between nostalgia then and nostalgia now: ‘Back then, nostalgia was nugatory . . . Twenty-one years later, nostalgia is generally considered healthful, wholesome, a very good thing and, not unlike the initially reviled Burlesque, something that pretty much everyone experiences, enjoys and benefits from’. One of the most significant practices of postmodernity associated with nostalgia was introduced by Jameson (1985) as ‘pastiche’. In his view, the stylistic form of pastiche is linked to a desire for nostalgia. Jameson’s concept of pastiche immediately caught on and inspired other critics to pursue his exploration of aspects of postmodern culture (Firat and Venkatesh, 1995). Pastiche in postmodernity referred broadly to ‘a free-floating, crazy-quilt, collage, hodgepodge patchwork of ideas or views’ (Rosenau, 1991: xiii). The postmodern understanding of ‘pastiche’ is thus extremely elastic and includes mashup, montage, collage, bricolage, combination, burlesque and so on. Pastiches of the past were endemic in postmodern consumption and marketing (Goulding, 2000). Many postmodern offerings combined a variety of elements into a pastiche that could often appear ‘grotesque’ (Brown, 2013) even if there was no intention of ridiculing these elements. Pastiche was even said to be one of the 4 Ps of postmodern marketing, together with parody, persiflage and playfulness (Brown, 1999). Brands have been a particularly fruitful field of application of pastiche. Indeed, during the postmodern era, there was ‘considerable overlap among nostalgia, brand heritage, and brand revival’ (Brown et al., 2003: 20). Postmodern neo-nostalgia culminated in the practice of retromarketing (Brown, 2001) and retrobranding (Brown et al., 2003), which combined product pastiche and community belonging. The postmodern neo-nostalgia through the development of pastiche allowed consumers to enjoy a nostalgic brand experience with no need for analysis or critical engagement with the past. All that was irrecoverable from the past was then attainable (Higson, 2014). One could drive a Beetle, a Mini, a 500 or, in fact, a retro pastiche of these iconic products of the past, not to mention the Chrysler PT Cruiser, ‘a pastiche of the upright sedans of the 1940s’ (Brown, 1999: 367). It should be noted, however, that postmodernity (Jameson, 1985) reinvented the notion of pastiche. Rose (1991: 35) contends that pastiche is ‘not only a post-modern device, as suggested by Jameson and those following him, but one which has been used, and talked about, for at least the last few centuries’. During the past three centuries, pastiche was generally characterized as borrowing, copying, rendering or – most frequently – as imitation, often paying homage to previous 486 Marketing Theory 20(4) works (Dyer, 2007). It represented ‘refigurations’ (Hoesterey, 2001) that would take formal elements of past styles and bring them forward into a contemporary context. Before the postmodern, the object of pastiche was thus defined as the style, manner or means of expression. Thus, with the postmodern, pastiche remained an imitation, but its source was less obvious and its purpose less evident. Our research project is thus driven by the wish to answer the question: ‘what happens to nostalgia in post-postmodern times?’. This question involves a focus on pastiche, a key practice associated with postmodern nostalgia, and the forms it takes – or not – in post-postmodernity. This question has also to be seen within the wider scope of mapping the post-postmodern zeitgeist. Methodological considerations The aim of our research is to reinvestigate the notions of nostalgia and pastiche in the postpostmodern zeitgeist. To do so, we provide a contextualized interpretive analysis of the changes associated with the post-postmodern zeitgeist reflected in the dual comeback of the Giulia brand. Our approach is consistent with content-centred studies in marketing scholarship that use brand-specific data to illustrate major aspects of consumer culture (Brown et al., 2013; Cronin and Fitchett, 2020; Cronin and Hopkinson, 2018). Societal changes such as the one under consideration are characterized by ambiguity and fuzzy boundaries, and the research approaches issued by researchers must therefore adjust to reflect an unfolding and changing reality. In line with Abbott (2004), we look at such phenomenon not from a population/analytical perspective but as fuzzy realities with autonomously defined complex properties, engaged in a perpetual dialogue with their environment. In our interpretive study, the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident as context forms an integral part of the study. Indeed, the post-postmodern context of our research on nostalgia and pastiche is an integral part of our work. Our choice of the Giulia episode was underpinned by the desire to obtain the richest possible information for identifying the variations nostalgia takes on in post-postmodernity. In addition, we looked for a post-postmodern phenomenon associated with cars, as we contend that looking at car brands may prove particularly fruitful in understanding what nostalgia is about in a postpostmodern era. Indeed, nostalgia in postmodern times has been largely addressed through study of the car industry, which has often seen the proliferation of retro-products and retro-brands (Brown et al., 2003; Cattaneo and Guerini, 2012). In 2015, the Giulia, produced by Alfa Romeo (Testa et al., 2017) but which went out of production in 1977, reappeared in the lives of the Italians from two different angles. The conjunction of the launch of a brand-new model of Giulia and the success of a film starring the old Giulia that very same year (2015) and in the same country (Italy) forms a worthwhile episode to investigate what happens to nostalgia and pastiche in postpostmodern times. The analysis of such an unusual phenomenon would allow us to obtain information of particular utility in fulfilling our research aim. Data collection and analysis This type of interpretive research is a highly qualitative form of inquiry; it typically involves a detailed investigation of one social phenomenon; it draws on data collected over a period of time and it aims to provide an analysis of the context and multiple meanings involved in the Cantone et al. 487 phenomenon under examination. Regarding the episode of the dual Italian comeback of the Giulia in 2015, we have collected data on different levels of the scale of observation: – on the level of Italian society in the 2010s; – on the level of the Alfa Romeo carmaker, its history and its connection with the Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA) group; – on the level of the launching event of the new Giulia, including its preparation and its follow-up; and – on the level of the movie, its characters, its material devices such as the old Giulia and its dialogues. The sociological investigation of changes in Italian society during the 2010s uses archives (Italian newspapers) and an expert interview (with an Italian sociologist, expert in social trends, work and organizations). The investigation of the evolution of the Alfa Romeo uses archive sources (the Alfa Romeo web site, Alfa Romeo Clubs) and an expert interview (with a former Italian racing driver who is currently a motor sport journalist). The data regarding the launching event come from accessible archives (27 articles in Italian newspapers, 3 books in Italian, 119 minutes of Alfa Romeo spokespersons videos, 3 Giulia commercials). Lastly, the film is 1 hour 55 minutes long and is available only in Italian; it is also accompanied by five press articles. Theorizing such an attempt at interpretation can take many different forms, but it often calls for a way of thinking that is more intuitive and less procedural than other research approaches (Swedberg, 2012). It is based on inferences made by the researchers, who follow the hermeneutical back-andforth principles of iterative analysis as recommended by Spiggle (1994). In our analysis, we have thus moved constantly from the surface structure of the data to the deep structure of the concepts by mobilizing prior works pertaining to marketing or other disciplines. The team of researchers worked in such a way as to maximize this hermeneutic approach, which allowed ideas to be developed or refuted at each stage with the mutual agreement of the three authors (Cronin and Fitchett, 2020). The three authors thus worked together to establish the major traits of 2015 Italian society and the key episodes in the ‘life’ of the Alfa Romeo carmaker. Thus, the first author focused on analysing the movie, while the third author focused on analysing the launch event. The second author acted as an intermediary between their analysis and the portfolio of relevant concepts regarding nostalgia, pastiche, the postmodern and the post-postmodern and their potential modulations. Altogether, the three authors negotiated and renegotiated the theorizing of the data several times before finally reaching an agreement. Moreover, the negotiations made it possible to maintain a critical distance from the data and to prevent attributing the label of post-postmodern to an event or situation that might be seen as postmodern, modern or even pre-modern by another observer. Findings The 2015 Italian context After decades of ‘Italian miracles’ (the 1950s/1960s and 1980s), the 2000s were marked by a stall in social mobility and the perception of an uncertain future.1 The lack of perspective for the future is the essence of the collective consciousness shared by young, adult and elderly people in Italy in this period. There is a lack of faith in capitalism and the industrial economy, as well as in the fundamental social institutions, which causes a loss of social identity. The widespread fear of falling behind created a collective climate of anxiety (Sarti and Vitalini, 2016). Uncertainty lay at 488 Marketing Theory 20(4) Figure 1. The old Giulia in the movie and the new Giulia on the road. the heart of widespread dissemination of a belief system based on surrender, the futility of initiative, passiveness, bias and resentment. In the absence of direction, what unites Italians is mainly their artistic and architectural heritage.2 Alfa Romeo and the Giulia The famous Italian carmaker Alfa Romeo has produced some of the most beautiful, exciting and gutsy cars in the world throughout its 110-year history; it has a strong racing pedigree and an even stronger classic car market value. After World War II, Alfa Romeo built on the fame brought by its two Formula One world championship victories of 1950 and 1951 to launch mainstream cars with a sporting allure. Alfa Romeo introduced two mid-range cars, the Giulietta in 1954 and the Giulia in 1962 (with the slogan ‘Giulia, the sedan that wins races’), both of which became Italian icons. The Giulia especially has long been used in Italian films to represent social success and power, representing either the bright side (the actors, the police) or the dark side (the Mafiosi). The Giulia was the brand of Italian car that interpreted the zeitgeist of Italian society more than any other in the immediate post-war period, embodying the ‘Italian miracle’. The last three decades (from the 1980s to the 2010s) were marked by the takeover of Alfa Romeo by Fiat and a continuous process of decay and the de-iconization of the new models (Testa et al., 2017). However, thanks to its extraordinary history, Alfa Romeo has always been a brand with a fond place in the memory of Italians of all ages. This is why the dual episode of 2015, starring the old Giulia in a movie and a new Giulia during a launching event, is worth investigating (Figure 1). The film – The legendary Giulia and other miracles The Legendary Giulia and Other Miracles is a 2015 Italian comedy (entitled ‘Noi e la Giulia’ – ‘Us and the Giulia’ – in Italian) that won many Italian awards and a great deal of success. Diego (the character who tells the story through voiceover), Fausto and Claudio are three unfulfilled 40-year- Cantone et al. 489 old men, fleeing from the city and their own lives, and who, as perfect strangers, find themselves united in the joint effort of opening a farm stay business located in Campania (Southern Italy). Sergio, a 50-year old fanatic, will join them, as will Elisa, a young pregnant woman, decidedly off her head. Their dream will be shattered by Vito, a curious camorrista, who comes to ask for protection money, driving up in an old Giulia 1300 from the 1960s. However, the reaction of the protagonists to this high-handedness is a real surprise. Sergio hits Vito in the face, knocking him unconscious to the ground. The companions decide to kidnap the mobster and lock him up in the basement room of the farmhouse. In an attempt to hide the kidnapping from other members of the Camorra, who will surely follow, the protagonists bury the old Giulia 1300 in the farmyard. However, because the protagonists bury the car with the keys still in the ignition, the defective stereo continues to work, and strains of classical music occasionally emerge from below ground. This ‘magical’ phenomenon would later contribute to the success of the holiday farm. After a period of success, the protagonists face the local Camorra and have to leave the farmland with Vito who has teamed up with them. The closing scene of the film frames them in the Giulia 1300 after digging it up. A post-postmodern tone to the movie. The movie exemplifies the post-postmodern trope of hope despite difficult circumstances with the addition of the notion of miracle. The filmmaker explores situations in which the five characters find themselves searching for redemption in an unfriendly Italian context (Doyle, 2018). They unwittingly form a group of desperate unfortunates, losers who have accomplished little – if anything – in their lives, whose sum total amounts to nothing more than drudge dead-end jobs, legal troubles, worries, depression, emotional and existential crisis and political nostalgia. However, these losers discuss the possibility of breaking down the immature fiction and detachment from their lives to try and build something positive and put the past behind them. So, they leave their alienating jobs amid the realization that in Italy the time has come to pursue a ‘plan B’, to make their dreams and ambitions come true, as Diego explains: We are the Plan B generation. Working in this country is so bad that, even if by some miracle you actually get the job you studied for, after two years you’ve had enough, and you start working on your plan B. It is usually a holiday farm, especially when you hate living in the city as much as your job. You kid yourself that it’ll be a better, healthier lifestyle, with more free time. What is striking in this story is the ubiquity of the notion of miracle. It is already present both in the title of the book that inspired the filmmaker and in the English title of the movie. In addition, the story is imbued with quasi-miraculous episodes connected with the existence of the Giulia. The most important is the music that occasionally surfaces from the buried Giulia 1300 and that gives the farm a magical atmosphere that contributes to its mystique. After early fears that the Giulia’s stereo continuing to work might create problems, they eventually invented a legend to explain the phenomenon to their clients, that Diego narrates as follows: ‘Mario was a promising conductor who fell in love with Giulia, a young noblewoman. However, Giulia was betrothed to a rich land owner . . . ’. At the end of this impossible love story Giulia dies, and Mario is so desperate that he kills himself but continues to play music from the hereafter to remain in contact with his beloved. The Giulia – which continues to play classical music from time to time, despite being buried under ground to cover up the kidnapping – becomes the miracle of the legend. Numerous guests come to the farmhouse on account of this mysterious music and spend a few days in this unique and timeless place. Another quasi-miraculous episode connected to the Giulia is the transformation 490 Marketing Theory 20(4) of the camorrista Vito, kidnapped by the protagonists and locked up in the basement of the farmhouse, where his Giulia is buried. Indeed, an affinity and mutual awareness between the five protagonists and Vito develops, and the Giulia 1300 can be started up again. It is dug up after several months as a possible means for the five to escape the vengeance of the local Camorra and thus head towards a possible new and better future. Through invented legends and lived episodes, the movie proposes the possibility of ‘mini-miracles’ (Higgins and Hamilton, 2016) that break the flow of the serious sociological and cultural issues of the post-postmodern era. These minimiracles bring the protagonists deliverance from suffering as experienced in the world they live in. This deliverance does not come about through attempts to escape but by reference to a power beyond the self – a higher power. However, blind faith is also challenged (Doyle, 2018) as the protagonists are aware of the limits of remaining hopeful. Reconstruction in post-postmodernity is reconstruction despite the paradoxes (Cronin et al., 2014; Skandalis et al., 2016): circumstances are vapid, people are not really believers, but miracles happen. Is there nostalgia? The protagonists are not yearning for the past. They show no sign of nostalgia for previous times; this is not part of their discourse. They are simply trying to make their life better in today’s difficult times. If they do nurture any nostalgic feelings, they are directed towards the farmhouse, which represents for them a sort of ‘get back to basics’. Upon the arrival of Vito – in Diego’s words ‘an old man driving a green Giulia’ – with the radio playing pleasant classical music, they show no sign of interest in the old iconic car. Quite the opposite, they ascribed a low status to Vito, an elderly member of the Camorra, because he drives what they consider to be an old car with zero residual value. One of the characters (Claudio), talking about the importance of camorristas in organized crime says, ‘so that man who came today is at the bottom of the criminal organization; do you see what he drives? He doesn’t have a good life, he dreams it’. Far from being considered a vintage car by the protagonists and thus generating nostalgic feelings, the Giulia is simply perceived as a second-hand car for poor people. Its former iconicity has vanished from their memory. And this seems to be the same for his driver, Vito. When one of the protagonists tells him that they have buried the car in the garden, he says: ‘Take care of it; it is a very dear memory . . . . Yes, it was my father’s’ (his father bought the car when he was hired as a music teacher at the secondary school). If Vito appears nostalgic, it is because of his link with a significant other, his father, whom the car comes to represent, not because it is a Giulia 1300. So, in the light of this lack of memory of the protagonists, why is this brand of car in the film? What are Italian viewers supposed to glean from its central position in the movie? As argued by an Italian film critic, ‘the Giulia 1300 is another protagonist of the story, the symbol of a melancholy hope, of the dream of nevertheless being able to win’.3 The filmmaker could have used any other car brand, but he chose this one as symbol of a bygone Italy, that of the ‘Italian Miracle’ of the 1960s. In 1964, the year of its launch, the Giulia was the fastest 1300 of its day. It symbolized social and economic improvement for the people who bought it. It was the car of winners after Alfa Romeo’s Formula One Championship victories of 1950 and 1951. And, when the Giulia 1300 is dug up after several months underground and is able to start again, it is a metaphor for the fact that Italians can start afresh if they rediscover the past values they need to bounce back. Diego details the scene: ‘At last the Giulia takes its first steps, dragged by Sergio’s car, skidding on the damp grass, swerving one way and another like a kite buffeted by the wind’. He then admits that the Giulia can be attractive: ‘The Giulia is there in front of me, on the grass, wonderful’. The closing scene of the film frames the five protagonists in the Giulia 1300 after digging it up. They thus Cantone et al. 491 abandon a transitory phase of their existence to head towards the future on board the Giulia. The Giulia represents the vehicle for regeneration in the film. Relic and glorious heritage. The Giulia 1300 that comes into view in the film is the old, iconic and successful model manufactured by Alfa Romeo from 1962 to 1977. However, in the context of the story, the Giulia 1300 looks like a relic. It is an object belonging to a past and valued time that returns unchanged: it is a revenant, a ‘zombie brand’ (Brown, 2016a: 240). In fact, the five protagonists do not recognize the ‘aura’ of the Giulia in the hands of an unknown camorrista from the outskirts. Moreover, Vito looks like a caricature of a real camorrista, with his insecure, ridiculous attitudes and the signs of weakness he shows throughout the story. He dresses badly and has a small and weak physique; he also speaks with a characteristic hint of dialect. The old Giulia 1300 is decorated with a huge red lucky charm to ward off the evil eye, and a rosary – used by Catholics for prayers in veneration of the Virgin Mary (Rinallo et al., 2012). Both hang from the rear-view mirror in plain sight. In the hands of Vito and with its rundown decoration, the Giulia is just a fallen and forgotten icon of the Italy of yore. This grotesque aspect is enhanced by the way Vito arrives at the farm. It recalls a scene from an old ‘spaghetti western’, when the lone villain arrives in the centre of town (in this case the farmhouse courtyard) riding his ‘horse’ (the Giulia 1300), confident that he will obtain what he wants by force. Finally, it is paradoxical that such a rough and grotesque camorrista like Vito might love the refined classic music coming from the Giulia. In Vito’s arrival sequence, all this means that the Giulia 1300 does not come across as a pastiche but an unchanged relic immersed in a situation that is a ‘refiguration’ (Hoesterey, 2001) of certain episodes of past Italian movies rewritten into a new narrative. Where the movie makes a break with the postmodern notions of pastiche is in the story itself, which, without (re)citing previous works, builds a tribute to previous production on the basis of key tropes of 1960s Italian cinema. Picturing reality through the strength of the stereotypes is a way of depicting society that pertains to the heritage of the glorious ‘commedia all’italiana’ – Italian-style comedy – produced at the height of Italy’s economic miracle following post-war reconstruction, which culminated in the boom period from 1958 to 1963 (Lanzoni, 2008). The ‘art of getting by’ (l’arte di arrangiarsi) is a distinct and essential narrative element of the commedia all’italiana. This comedic expression of daily survival, a narrative tradition rooted in commedia dell’arte and the works of Carlo Goldoni, is central to the story proposed in the movie. Within the comedy and satire is a drama of social disorder and individual survival within a chaotic society. In addition to the arte di arrangiarsi, the filmmaker also borrows from the commedia all’italiana the stereotyping of characters and the showcasing of cars, and especially Alfa Romeo cars (Testa et al., 2017). Thus, the film The Legendary Giulia and Other Miracles, with its return to realism, albeit in a new form, still under the influence of the postmodern legacy, but driven by the need to rehumanize, pays specific homage to the Italian cinema of the 1960s without undue striving to imitate or mimic certain sequences or characters. The relaunch of the Giulia It is 24 June 2015. Hundreds of journalists and other invited guests are starting to arrive in Arese, close to Milan, the birthplace of the Alfa Romeo. In a ceremony starring the world-renowned Italian Andrea Bocelli singing ‘Nessun dorma’ (‘None Shall Sleep’), the tenor aria from Puccini’s Turandot, Fiat CEO Sergio Marchionne unveils the Giulia, a new sedan that will herald the beginning of the carmaker’s product renaissance. The Giulia is pitched to take on the likes of the 492 Marketing Theory 20(4) Audi A4 and BMW 3-Series and is the first of several new models due to be launched over the next 3 years. On this occasion, Marchionne delivered a speech explaining how the decision was predicated on a number of cultural and industrial realities. This was followed by another speech by Harald Wester, CEO of Alfa Romeo. A post-postmodern stance to the event. The speeches delivered at the launch of the new Giulia herald some major post-postmodern features. Marchionne breaks with any kind of irony that might be associated with postmodernism, admitting in all sincerity that, If we look at the history of our choices as owners of the Alfa Romeo brand, we have not got one right apart from the last two models: the MiTo and the Giulietta. With these two models we have done nothing ‘grandiose’, but what we did previously was actually an affront to the brand. Marchionne is sincere about Alfa Romeo’s past, admitting the mistakes made by the Fiat Group during the past three decades. In his speech, Marchionne gives the impression of having paid off a debt: In the last thirty years, Alfa has borne a sense of incompleteness that desperately needed to be addressed; letting it compete with other common or low cost brands would have meant betraying the spirit and values of the brand. This was a task that cried out for action; giving a voice to the real Alfa was also a moral duty. And Wester admits that they have more to change about themselves to manage the Giulia than to change the brand: ‘there was nothing to change about this brand, but we had to change everything about ourselves, learning from the history of difficult times, from mistakes; we felt great responsibility towards the men and women who made this story great’. In both declarations, an attempt was made to suspend irony in favour of sincerity. These managers no longer see sincerity as something to be afraid of. The emphasis of both managers’ declarations on sincerely and fearlessly confessing previous mistakes resonates with what we already know of the post-postmodern sensibility. However, irony is not too far off. Let us just remember that under Marchionne’s (Italian-born, Canadianraised) captainship, the Fiat Group HQ left Italy: the new FCA headquarters immigrated to Great Britain, the registered office was set up in Amsterdam and the main stock exchange for the group became Wall Street, with Milan only in secondary position. The juxtaposition of such irony markers with the speeches celebrating the great Italian past of the Giulia generates a kind of incongruity. Irony thus vies with sincerity in managers’ speeches (Doyle, 2018). Another post-postmodern stance visible during the launch is the emphasis on reconstruction (Fjellestad and Engberg, 2013). ‘We have imagined, planned, and turned the “Renaissance of Alfa Romeo” into reality’ was Wester’s declaration during the launch of the new Giulia. And Marchionne argued that the time was right for the return of the Alfa Romeo: ‘At long last we can say that today is the first day of a new era for Alfa. A brand that has taken back the place it deserves on the car scene’. In their speeches, the Alfa Romeo managers expressed the need to fulfil a moral obligation to return the brand to those who had been deprived of this great tradition for so many years: the Alfa employees and the Alfa Romeo fans of yesterday and today who have helped create and nurture the Alfa Romeo legend. In doing so, they based the reconstruction of the brand on communality and the ways this reconstruction can be, and be retold, among people (Canavan and McCamley, 2020). The tropes of re-turn, remaking, reconstruction and so on that Cantone et al. 493 characterize the post-postmodern zeitgeist (Cervellon and Brown, 2018b) are visible in all these declarations. Nostalgia regenerating the present. During the launch event, Fiat managers adopted a ‘cultural’ language, full of symbols, metaphors and analogies with a strong ideological content, inspired by several periods in the history of the country that had expressed the creativity and intellect of the Italian people, producing the best in art and music. At first sight, this juxtaposition of symbols and images could act as a kind of postmodern collage, nostalgically mingling everything that belonged to the past. However, it is worth taking a second look. Two of the referents and analogies that have been recalled by the FCA top managers during the event – The Renaissance as the driving referent for the whole innovation process surrounding the new Giulia and Turandot as an analogy of the life of the Giulia brand – are directly related to the stance of reconstruction and allow the definition of a nostalgia that also looks to the future. The Renaissance referent best captures the endeavour of looking to the past for the recovery of a lost heritage. The Renaissance began in Tuscany (Central Italy) after the centuries labelled the Dark Ages. It stands as a period of cultural revival and renewed interest in classical antiquity (Greek and Latin). The literal meaning of the word is ‘rebirth’. Thus, the repeated use of such a major referent from the past epitomizes the ambition to ‘re-make’ (Fjellestad and Engberg, 2013). The glorious cultural past of Italy is used to inspire a fresh restart. Marchionne explicitly referred to the Turandot analogy during his presentation speech. After Bocelli’s performance of the aria ‘Nessun dorma’, Marchionne declared that the Giulia is our Turandot for at least for two reasons. Firstly, it’s been a long time in coming. Secondly, over the past two years, it has seen an exceptional transformation . . . Alfa Romeo Giulia went through a long cathartic process and came out from it pure again. Turandot is an operatic aria composed by Italian composer Giacomo Puccini and is the very last masterpiece of the grand operatic tradition. Turandot is the Ice Princess, a woman who obsesses over a distant ancestor who was ravaged by a marauding male. No man will win Turandot unless he can answer three riddles, and if he fails, as invariably happens, the punishment is death. An Unknown Prince accepts the challenge and wins the contest. Turandot, a man-hater, the ice Princess, undergoes a ‘self-reformation’ that transforms her into a beloved and, indeed, loving wife. Marchionne suggests that he – together with his team – is the Prince who, after many years, has transformed the Princess Giulia. Marchionne states that his team has succeeded in transforming one of the most important icons of the 1960s ‘Italian Miracle’ from being the ‘ice princess’ it had become over the preceding decades (from the 1980s to the 2000s) – dismissing any attempts by previous Fiat managers – into a beauty ready to seduce new lovers. The Giulia metamorphosis came about thanks to a team of 10 specialists in different departments who abandoned the usual R&D organization to design a new car in 2 years. ‘They are the ones who have performed the miracle and have changed the Alfa’ he adds. Both these referents and analogies – the Renaissance and Turandot – refer to Italy’s illustrious past to build the future of the Giulia. As an advertisement put it, ‘Nuova Alfa Romeo Giulia – You can only make history’. The future history of the Giulia has its roots in the history of the country and not only in the history of the brand. Marchionne’s references to Italy’s past may show multiple layers of nostalgia and retro-celebrations. However, they can also indicate the use of nostalgia in a regenerative way that does not end in the celebration of the past but takes it as a starting point for envisioning the future. 494 Marketing Theory 20(4) Realigning the brand’s essence with that of the nation. The new 2015 Giulia brings together an exciting sports design and rear-wheel drive that restores the brand’s historical technological tradition. Unlike several branding strategies employed in the world automotive industry over the last two decades, the new Giulia has nothing in common with its predecessor from the stylistic point of view. It does not try to mimic the old Giulia. The only stylistic similarity is the iconic Alfa Romeo badge that has been given a fresh touch with a restyled border; it is set in a crisp, traditional trefoil grille framed by the meanest-looking front end seen on an Alfa Romeo in many years. As for the rest, it is a continuation of recent Alfa models – the 155, 156 and 159 – belonging to the same category and the same size, rather than a reinterpretation of the old Giulia. The 2015 Giulia launch is not a mere retrobranding operation (Dion and Mazzalovo, 2016), nor a replicant or revival phenomenon (Brown, 2013). Marchionne does not seek instant acceptance of a new brand recalling the past. At the same time, he is not interested in bringing a product back to life. With his team, they do not set out to repeat the past at it was. However, it should be clear, from the Fiat perspective, that there is something else about the new Giulia that recalls the old one. For Marchionne, this something is its DNA or brand essence: We studied the history of Alfa Romeo in depth, and we wanted to understand why the brand is so much loved across the globe and why the great technical successes of the past have not been followed by the same commercial success. We have learned from both, from the triumphs but also from the mistakes and failures, and we set out to put the Alfa DNA chain back together, to restore it to its true nature. Wester lists the five elements that make Alfa Romeo stand out from all other cars: ‘1. cutting-edge and innovative engines, 2. perfect weight distribution, 3. unique technological solutions, 4. the best power-to-weight ratio for each car that we will launch in each category, 5. an extraordinary and distinctly Italian design’. In spelling out the Giulia heritage, the Fiat managers went beyond the aesthetic and/or symbolic dimensions of the brand to search for the brand essence (Dion and Mazzalovo, 2016). However, Wester adds that ‘these five elements are indispensable but not sufficient to create an Alfa Romeo’. Beyond these five elements, there is something more important at stake with the relaunch of the Giulia. Marchionne and his team did not work solely on brand essence but also on that of Italy itself. They designed the Giulia to reconnect Italians to their country’s essence and resonate with Italians from all parts of the country and backgrounds. In his speech, Marchionne stresses the need to revitalize Italy: ‘Italy is a country with one of the biggest but most unexpressed potentialities that I know’. Although Marchionne was not hired by FCA to fix Italy, his project for the new Alfa Romeo was that it would be ‘one of the most important champions of the Italian spirit in the world, a style icon, a symbol of the best technological know-how and the best creative spirit of this country’. Even Matteo Renzi, the Italian Prime Minister in 2015, tweeted his recognition of the prominent role of the new Giulia at national level: ‘How wonderful! Welcome Giulia! Italy starts again’. So, when Marchionne and his team worked on the Giulia’s DNA, they did so both at the level of the essential elements of the car and at the essential elements of the nation. These elements are the ones that made Italy great after World War II, leveraging the technological talent, creativity, styling capabilities and collective hope and energies of the Italian people in times of trouble. The project for the new Giulia incorporated this resilient essence of Italy.4 This incorporation did not deny the difficulties of contemporary life, but it managed to build on this resilience. In doing so, Marchionne aligned the essence of the brand with that of the nation and society. The new Giulia is not just a matter of design, atmospherics and brand associations: it is a matter of techno-ideological come backs. Its brand essence, or ‘brand aura’ (Brown et al., 2003), is not limited to the brand name alone and some Cantone et al. 495 associated/core immaterial values, as is the case of the new DS by Citroën and its ‘anti-retro marketing’ strategy (Prieto and Boistel, 2014). The essence of the Giulia expands to include some major elements of ‘Italianness’, realigning the brand with society. Discussion By combining the points of view of filmmakers and managers, the Giulia episode offers an exceptional opportunity to observe the changes connected with the post-postmodern zeitgeist in an Italian context and to discuss their impacts on nostalgia and pastiche, which have been defined as key features of postmodernity (Jameson, 1985). Before entering into this discussion, it is worth noting that the postmodern is still there, standing on the corner, both in the film and at the event launching the Giulia. It has far from totally disappeared from the lives of the Italians and the lives of brands. A reconstructive stance (Cervellon and Brown, 2018b; Fjellestad and Engberg, 2013) runs through the film and the launch alike. In the case of the film, it takes the form of ‘Plan B’, a shared humble and limited reconstructive spirit among the protagonists despite the serious sociological and cultural issues of 21st-century life (Doyle, 2018). In the case of the launch, it is evident in the sincerity of the managers, who shun any sense of ironic detachment and fear of honesty (Doyle, 2018). In both, the many mistakes and errors made in the past (during the lives of the protagonist and the life of the brand) impacts on the future but taking them into account makes it possible to urge people to act and change the situation. In the film, the reconstruction is facilitated by the advent of a quasi-miracle that creates the business success for an improbable location. The carmaker also introduces the new car as the result of a miracle. The possibility of a miracle forms a trait of the post-postmodern reconstructive stance. It is not (only) a reconstruction based on faith in progress or science but the fact that people think that miracles are possible in today’s world. When a society experiences a severe identity crisis, a combination of a sense of vulnerability, uncertainty and lack of opportunity takes root, and with it the hope of prodigious events. In line with Higgins and Hamilton (2016) who discuss the meaning of the contemporary ‘mini-miracles’ that take place during Lourdes pilgrimages, this kind of mini-miracle can be defined as a transformation that brings positive benefits to the powerless (Thomas et al., 2018). In a post-postmodern zeitgeist, people live in a state from which they expect to be saved or rescued, and miracles are attributed to forces beyond individual control. However, salvation ‘is not so much “theological” as “phenomenological”’ (Bacon et al., 2015: 30). Even so, albeit understood as a reference to a power beyond the self, it is not the grace of God that would save the five protagonists of the film or the brand. It is the resilient effort of people brought together by chance or design and who want to collectively bring about changes. Post-postmodern miracles are thus improbable events made possible by the existence of a collective, even a collective of rather desperate humans. Given this historical juncture in which we all find ourselves since the outbreak of the Covid pandemic, such mini miracles might be very important in bringing about ‘Plan B’. The centrality of the past and its significance for the present and future is at the core of the nostalgia operating in the Giulia episode, especially with the carmaker but without regret or melancholy. Neither the protagonists of the film or the managers are yearning for the past: they take the past as a key resource for today and the future. There is no yearning for bygone days, but there is an acceptance that the past could be an ‘inheritance in the present and a bequest to the future which affords opportunities and responsibilities’ (Balmer and Burghausen, 2019: 221). The ‘atemporality’ of postmodern nostalgia (Higson, 2014; original emphasis) which is about the past, but where the past is contemporary with the present, is replaced by a regenerative nostalgia where 496 Marketing Theory 20(4) there is a clear dividing line between past and present. Post-postmodern nostalgia is not about a celebration of past style; it is about reconstruction on the basis of the past. This is exemplified by the attitude of the protagonists of the film, who ascribe no value to the Giulia, which comes directly from the past. This type of co-presence is not expected and not welcomed. The experience of loss is not replaced by possessing the past but by (re)building on it, and this past is anchored in a territory. With post-postmodern nostalgia, the look towards the past aims to recover, from one or more previous local realities or historical moments, those elements or symbols that, when placed in a structured system, allow people to envision the future. In post-postmodernity, nostalgia is not only a longing for the way things were, but it also has important future-oriented roles (Veresiu et al., 2018). The filmmaker and the carmakers mobilize this sort of nostalgia by reflecting on winning key elements from a previous Italy to articulate present and future possibilities (the Giulia, the Renaissance, Turandot). Nostalgia is thus not limited to previous products and brands in the same industry but covers all the elements that make people proud to be Italian. Regenerative nostalgia engages with major milestones from a nation’s past and points to reinjecting what they bear – and not what they are – in present time. It is thus something that people can enjoy and benefit from (Cervellon and Brown, 2018b). Where the dual Giulia come back makes the most compelling contribution to our understanding of the post-postmodern zeitgeist is in relation to pastiche. While postmodern marketing has made pastiche one of the 4 Ps of the retromarketing approaches (Brown, 1999) by adopting a rather stylistic meaning of pastiche limited to the imitation of the surface of things, the episode at hand informs us that pastiches have to do with the essence of things in post-postmodernity: the essence of Italian cinema, the essence of the Giulia and Alfa Romeo. Post-postmodernity pays scant attention to the refiguration (Hoesterey, 2001) or recombination (Brown, 2013) of elements from the past and other forms of superficial pastiches; it focuses on essentialist pastiches. By essentialist, following the philosophical tradition of Plato and Aristotle and other pre-Darwinian thinkers (Gergen, 2018), we refer to the attributes or properties that are supposed to be inherent in the entity itself, independent of the viewer, and form the underlying essence that makes it what it is. An essentialist pastiche is thus a new interpretation of an entity based on its essence with the aim of paying homage to it. The movie is an essential pastiche of the ‘commedia all’italiana’ of the 1960s; the new Giulia is an essential pastiche of the Giulia from the 1960s. As an essential pastiche, the new Giulia does not belong to the range of retro-products and retrobrands that are ‘new state-of-the-art stuff . . . sold with the aid of an old-time message, or narrative, or styling, or packaging, or logotype, or slogan or mascot’ (Cervellon and Brown, 2018b: 27). Nor does it belong to the anti-retro-brands (Prieto and Boistel, 2014) like the DS that builds on the exceptional heritage of the Citroën DS cars originally launched in 1955 without retaining any of its technological or ideological solutions. Like other ‘sleeping beauties’, the new Giulia draws on an attentive selection of product features (design, technology and know-how) and features related to the brand’s history (Dion and Mazzalovo, 2016). This is meant to represent the essence of the brand. It is related to Alfa Romeo’s heritage-based rebranding (Balmer and Burghausen, 2019) at corporate level, of which the new Giulia is the pilot outcome. In addition, the new Giulia epitomizes not only the essence of Alfa Romeo but also, to a certain extent, the essence of Italy: it epitomizes the important period after World War II, during which the country’s essence came to be described as resilient. Alfa Romeo managers have captured this country’s essence and combined it with the brand essence to offer something thus far removed from what retrobranding strategies have proposed by exploiting a perceptive space already existing in the mind of consumers. In a post-postmodern zeitgeist, the days of superficiality are over and marketing has to move beyond positions that could be seen as an obsessive celebration and reinterpretation of the past. Cantone et al. 497 Thriving in tough times necessitates major involvement with the essence of things. In terms of brand management, this means going beyond product design, beyond brand heritage, to uncover what is essential both in the brand itself and in its context – the country, the period – to regenerate it. While every year, hundreds of retro-products roll off the production lines, future marketing research will have to analyse the performance of such stylistic pastiches and compare them with one of the more essential pastiches such as the Giulia. Conclusion Will retro continue to reign glorious for time to come (Brown, 2018)? Based on the results of our analysis in Italy and in parallel with the hypotheses of other works (Cervellon and Brown, 2018b; Dion and Mazzalovo, 2016; Veresiu et al., 2018), we would tend to be dubious about the longevity of the retro reign. Even if the postmodern and retro continue to drive many of our behaviours and strategies, the post-postmodern zeitgeist is bringing with it a mutation of nostalgia that is becoming regenerative and aspiring for change. The major consequence is the changing nature of pastiche, moving from stylistic to essentialist. Marketing research will have to investigate the future of pastiche. Are we close to the end of pastiche as we knew it in postmodern times? What are the other potential mutations of pastiche beyond essential pastiche practice? Could the notion of essential pastiche be a return to a modern and univocal way of looking at the world around us? Furthermore, our understanding of the coming zeitgeist has improved: in addition to the confirmation of the major features of post-postmodernity already established in the literature, this study argues that the possibility of a (mini)miracle to realize ‘Plan B’ is another key feature of our times. Whereas our results, especially those concerning miracles, must be tempered by the specificities of the Italian context, we contend that miracles assume a central role in the postpostmodern social imaginary and as such must be assimilated and analysed by consumer culture theory. Today, miracles do not concern religion alone. Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. ORCID iDs Bernard Cova https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0459-5083 Pierpaolo Testa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8898-4731 Notes 1. http://www.censis.it/rapporto-annuale 2. https://www.ipsos.com/fr-fr/ipsos-flair-italie-2016-administrer-le-desordre 3. https://www.noteverticali.it/visioni/noi-e-la-giulia-la-commedia-di-edoardo-leo-che-sa-regalare-risate-esperanza/ 4. https://www.ft.com/content/2c4dcf54-216b-11e8-a895-1ba1f72c2c11 498 Marketing Theory 20(4) References Abbott, A. (2004) Methods of Discovery: Heuristics for the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Norton & Company. Bacon, H., , Dossett, W. and and Knowles, S. (eds) (2015) Alternative Salvations: Engaging the Sacred and the Secular. London, UK: Bloomsbury. Balmer, J. M. and Burghausen, M. (2019) ‘Marketing, the Past and Corporate Heritage’, Marketing Theory 19(2): 217–27. Brown, S. (2001). Marketing-The Retro Revolution. London, UK: Sage. Brown, S. (1999) ‘Retro-Marketing: Yesterday’s Tomorrows, Today!’, Marketing Intelligence & Planning 17(7): 363–76. Brown, S. (2013) ‘Retro From the Get-Go: Reactionary Reflections on Marketing’s Yestermania’, Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 5(4): 521–36. Brown, S. (2016a) Brands and Branding. London, UK: SAGE. Brown, S. (2016b) ‘Postmodern Marketing: Dead and Buried or Alive and Kicking?’, in M. J. Baker and S. Hart (eds) The Marketing Book (7th ed.), pp. 43–58. Oxon, UK: Routledge. Brown, S. (2018) ‘Retro Galore! Is There No End to Nostalgia?’, Journal of Customer Behaviour 17(1-2): 9–29. Brown, S., Kozinets, R.V. and Sherry, J.F., Jr (2003) ‘Teaching Old Brands New Tricks: Retro Branding and the Revival of Brand Meaning’, Journal of Marketing 67(3): 19–33. Brown, S., McDonagh, P. and Shultz, C.J. (2013) ‘Titanic: Consuming the Myths and Meanings of an Ambiguous Brand’, Journal of Consumer Research 40(4): 595–614. Canavan, B. and McCamley, C. (2020) ‘The Passing of the Postmodern in Pop? Epochal Consumption and Marketing From Madonna, Through Gaga, to Taylor’, Journal of Business Research 107(February): 222–30. Cattaneo, E. and Guerini, C. (2012) ‘Assessing the Revival Potential of Brands From the Past: How Relevant Is Nostalgia in Retro Branding Strategies?’, Journal of Brand Management 19(8): 680–87. Cervellon, M.C. and Brown, S. (2018a) ‘Reconsumption Reconsidered: Redressing Nostalgia with NeoBurlesque’, Marketing Theory 18(3): 391–410. Cervellon, M.C. and Brown, S. (2018b) Revolutionary Nostalgia: Retromania, Neo-Burlesque and Consumer Culture. London, UK: Emerald. Cova, B., Maclaran, P. and Bradshaw, A. (2013) ‘Rethinking Consumer Culture Theory From the Postmodern to the Communist Horizon’, Marketing Theory 13(2): 213–25. Cronin, J. and Fitchett, J. (2020) ‘Lunch of the Last Human: Nutritionally Complete Food and the Fantasies of Market-Based Progress’, Marketing Theory. DOI: 10.1177/1470593120914708. Epub ahead of print 7 April 2020. Cronin, J. and Hopkinson, G. (2018) ‘Bodysnatching in the Marketplace: Market-Focused Health Activism and Compelling Narratives of Dys-Appearance’, Marketing Theory 18(3): 269–86. Cronin, J., McCarthy, M. and McCarthy, S. (2014) ‘Paradox, Performance and Food: Managing Difference in the Construction of Femininity’, Consumption, Markets and Culture 17(4): 367–91. Denzin, N.K. (1991) Images of Postmodern Society: Social Theory and Contemporary Cinema, Vol. 11. London, UK: SAGE. Dion, D. and Mazzalovo, G. (2016) Reviving sleeping beauty brands by rearticulating brand heritage. Journal of Business Research 69(12): 5894–5900. Doyle, J. (2018) ‘The Changing Face of Post-Postmodern Fiction: Irony, Sincerity, and Populism’, Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 59(3): 259–70. Dyer, R. (2007) Pastiche: Knowing Imitation. London, UK: Taylor & Francis. Firat, A.F. and Venkatesh, A. (1995) ‘Liberatory Postmodernism and the Reenchantment of Consumption’, Journal of Consumer Research 22(3): 239–67. Fjellestad, D. and Engberg, M. (2013) ‘Toward a Concept of Post-Postmodernism or Lady Gaga’s Reconfigurations of Madonna’, Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture 12(4): 2. Cantone et al. 499 Frangipane, N. (2016) ‘Freeways and Fog: The Shift in Attitude Between Postmodernism and PostPostmodernism From the Crying of Lot 49 to Inherent Vice’, Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 57(5): 521–32. Gergen, K.J. (2018) Constructionism vs. Essentialism, in M. Ryan (ed.) Core Concepts in Sociology, pp. 43–5. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Goulding, C. (2000) ‘The Commodification of the Past, Postmodern Pastiche, and the Search for Authentic Experiences at Contemporary Heritage Attractions’, European Journal of Marketing 34(7): 835–53. Higgins, L. and Hamilton, K. (2016) ‘Mini-Miracles: Transformations of Self From Consumption of the Lourdes Pilgrimage’, Journal of Business Research 69(1): 25–32. Hill, N. (2017) The Nix. New York, NY: Penguin. Higson, A. (2014) Nostalgia is not what it used to be: Heritage films, nostalgia websites and contemporary consumers. Consumption Markets & Culture 17(2): 120–142. Hoesterey, I. (2001) Pastiche: Cultural Memory in Art, Form, Literature. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. Hutcheon, L. (2003) The Politics of Postmodernism. London, UK: Routledge. Jameson, F. (1985) ‘Postmodernism and Consumer Society’, Postmodern Culture, 115(11): 111–125. Lanzoni, R.F. (2008) Comedy Italian Style: The Golden Age of Italian Film Comedies. New York, NY: Continuum. Niemeyer, K. (ed.) (2014). Media and Nostalgia: Yearning for the Past, Present and Future. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Prieto, M. and Boistel, P. (2014) ‘Rétromarketing dans l’automobile’. Revue Française de Gestion 239: 31–49. Rinallo, D., Borghini, S., Bamossy, G., et al. (2012) ‘When Sacred Objects Go B ® a (n) d: Fashion Rosaries and the Contemporary Linkage of Religion and Commerciality’, in D. Rinallo, L. Scott and P. Maclaran (eds) Consumption and Spirituality, pp. 45–56. London, UK: Routledge. Rose, M.A. (1991) ‘Post-Modern Pastiche’, British Journal of Aesthetics 31(1): 26–38. Rosenau, P.M. (1991) Post-Modernism and the Social Sciences: Insights, Inroads, and Intrusions. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Sarti, S. and Vitalini, A. (2016) ‘La salute degli italiani prima e dopo la crisi economica (2005-2013): Alcune evidenze empiriche sulle categorie sociali a maggior rischio di impatto’, Quaderni di Sociologia 72(2): 31–55. Skandalis, A., Byrom, J. and Banister, E. (2016) ‘Paradox, Tribalism, and the Transitional Consumption Experience: In Light of Post-Postmodernism’, European Journal of Marketing 50(7/8): 1308–25. Skandalis, A., Byrom, J. and Banister, E. (2019) ‘Experiential Marketing and the Changing Nature of Extraordinary Experiences in Post-Postmodern Consumer Culture’, Journal of Business Research 97(April): 43–50. Spiggle, S. (1994) ‘Analysis and Interpretation of Qualitative Data in Consumer Research’, Journal of Consumer Research 21(3): 491–503. Swedberg, R. (2012) ‘Theorizing in Sociology and Social Science: Turning to the Context of Discovery’, Theory and Society 41(1): 1–40. Testa, P., Cova, B. and Cantone, L. (2017) ‘The Process of De-Iconisation of an Iconic Brand: A Genealogical Approach’, Journal of Marketing Management 33(17-18): 1490–521. Thomas, S., White, G.R. and Samuel, A. (2018) ‘To Pray and to Play: Post-Postmodern Pilgrimage at Lourdes’, Tourism Management 68: 412–22. Tumbat, G. and Belk, R.W. (2011) ‘Marketplace Tensions in Extraordinary Experiences’, Journal of Consumer Research 38(1): 42–61. Veresiu, E., Robinson, T.D. and Rosario, A.B. (2018) ‘Reflective Nostalgia in Post-Socialist Cartoon Consumption: Rethinking the Temporal Dynamics of a Consumable Past’, in D. Badje and D. Kjeldgaard (eds) Consumer culture theory conference, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, 28 June – 1 July 2018. 500 Marketing Theory 20(4) Luigi Cantone is a full-time Professor of Marketing at Federico II University of Naples. His research interests focus on Consumer Culture Theory, brand management and consumer engagement. His research has been published in the Journal of Marketing Management, the International Journal of Innovation Management and Sinergie – Italian Journal of Management. Furthermore, he is the author of several books on marketing and strategic management. Address: Department of Economics Management Institutions, Federico II University of Naples, 21 Vicinale Cupa Cintia Road, Monte S. Angelo University Campus, 80126 Naples, Italy. [email: lcantone@unina.it] Bernard Cova is a full-time Professor of Marketing at Kedge Business School, Marseille, France. Ever since his first papers in the early 1990s, he has taken part in postmodern trends in consumer research and marketing. A pioneer in Consumer Culture Theory, his work on this topic has been published – among others – in the Journal of Consumer Research, the European Journal of Marketing, the Journal of Business Ethics, Marketing Theory and Organization. Address: Department of Marketing, Kedge Business School, Domaine de Luminy, BP 921, 13288 Marseille Cedex 9, France. [email: bernard.cova@kedgebs.com] Pierpaolo Testa is an Assistant Professor of service management at Federico II University of Naples. His current research efforts focus on Consumer Culture Theory, brand management and consumer engagement. His works have been published on the Journal of Marketing Management, the International Journal of Innovation Management and Sinergie – Italian Journal of Management. Address: Department of Economics Management Institutions, Federico II University of Naples, 21 Vicinale Cupa Cintia Road, Monte S. Angelo University Campus, 80126, Naples, Italy. [email: p.testa@unina.it]