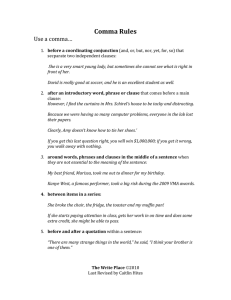

LEKTURA I KOREKTURA ZA PREVODIOCE EDITING TRANSLATION INTO ENGLISH RESOLVING PROBLEMS PERTAINING TO SENTENCE STRUCTURE SIMPLE SENTENCE Comma is not essential if the introductory clause or phrase is a short one specifying time or location: In 2000 the hospital took part in a trial involving alternative therapy for babies. Before his retirement he had been a mathematician. A comma should never be used after the subject of a sentence except to introduce a parenthetical clause: The coastal city of Bordeaux is a city of stone. The primary reason the utilities are expanding their non-regulated activities is the potential of higher returns. Adverbs such as however, moreover, therefore and already in the beginning of a sentence are followed by a comma. However, they may not need it much longer. Moreover, agriculture led to excessive reliance on starchy monocultures such as maize. In the middle of a sentence however and moreover are enclosed between commas: There was, however, one important difference. However is not followed by a comma when it modifies an adjective or an adverb: However fast Achilles runs he will never reach the tortoise. Commas separating adjectives Nouns can be modified by multiple adjectives. Whether or not to use a comma depends on the type of the adjective. Gradable or qualitative adjectives (happy, stupid, large) can be used in the comparative and superlative and be modified by a word such as very, whereas classifying adjectives (annual, mortal, American) cannot. No comma is needed to separate adjectives of different types (large and small – qualitative, black and edible classifying): a large black gibbon, a small edible fish. A comma is needed to separate two or more qualitative adjectives: A long, thin piece of wood A soft, wet mixture No comma is needed to separate two or more classifying adjectives where the adjectives relate to different classifying systems: French medieval lyric poet, annual economic growth, randomized controlled trial. Serial comma The presence of lack of a comma before and or or in a list of three or more items is the subject of much debate. Such a comma is known as a serial comma. For a century it has been part of OUP style to retain or impose this last comma consistently (the Oxford comma). Mad, bad, and dangerous to know. A thief, a liar, and a murderer. A government of, by, and for the people. The general rule is that one style or the other should be used consistently. However, the last comma can be used to resolve ambiguity, particularly when any of the items are compound terms joined by a conjunction, and it is sometimes helpful to the reader to use an isolated serial comma for clarity: cider, real ales, meat and vegetable pies, and sandwiches; the bishops of Winchester, Salisbury, Bristol, and Bath and Wells (one bishop for Bath and Wells). The other way round: the bishops of Bath and Wells, Bristol, Salisbury, and Winchester. In a list of three or more items, use a comma before a final extension phrase such as etc., and so forth, and the like (potatoes, swede, carrots, turnips, etc.), (candles, incense, vestments, and the like.). A comma is placed after namely and for example when part of a parenthetical phrase: Take, for example, the shutting of a small girl in a locker by three older girls. A comma is used after that is. Oxford style does not use a comma after i.e. and e.g. to avoid double punctuation, but US usage does. Semicolon The semicolon marks a separation that is stronger than a comma but less strong than a full point. It divides two or more main clauses that are closely related and complement or parallel each other and that could stand as sentences in their own right: Truth ennobles man; learning adorns him. In a sentence that is already subdivided by commas, a semicolon can be used instead of a comma to indicate a stronger division: He came out of the house, which lay back from the road, and saw her at the end of the part; but instead of continuing towards her, he hid till she had gone. In lists with internal commas, semicolons structure the internal hierarchy of its components: I should like to thank the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford; the staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford; and the staff of the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Colon The colon points forward: from a premise to a conclusion, from a cause to an effect, from an introduction to a main point, from a general statement to an example. It fulfils the same function as words such as namely, that is, as, for example, for instance, because, as follows and therefore. That is the secret of my extraordinary life: always do the unexpected. It is available in two colours: pink and blue. COMPOUND SENTENCE Connecting independent clauses There are two types of words that can be used as connectors at the beginning of an independent clause: coordinating conjunctions and independent marker words. 1. Coordinating Conjunction The seven coordinating conjunctions used as connecting words at the beginning of an independent clause are and, but, for, or, nor, so, and yet (fanboys). When the second independent clause in a sentence begins with a coordinating conjunction, a comma is needed before the coordinating conjunction: Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz, but it was hard to concentrate because of the noise. 2. Independent Marker Word An independent marker word is a connecting word used at the beginning of an independent clause. These words can always begin a sentence that can stand alone. When the second independent clause in a sentence has an independent marker word, a semicolon is needed before the independent marker word. Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz; however, it was hard to concentrate because of the noise. Other similar markers: also, consequently, furthermore, however, moreover, nevertheless, and therefore. Comma splice A comma alone should not be used to join two main clauses, or those linked by adverbs or adverbial phrases such as nevertheless, therefore, as a result. This error is called comma splice. Incorrect use: I like swimming very much, I go to the pool every week. He was still tired, nevertheless he went to work as usual. This error is corrected by adding a coordinating conjunction (and, but, so) or by replacing the comma with a semicolon or colon: I like swimming very much, and go to the pool every week. He was still tired; nevertheless, he went to work as usual. These could also be split into two full sentences. A comma splice (joint) is the use of a comma between two independent clauses. You can usually fix the error by changing the comma to a period and therefore making the two clauses into two separate sentences, by changing the comma to a semicolon, or by making one clause dependent by inserting a dependent marker word in front of it. Incorrect: I like this class, it is very interesting. Correct: I like this class. It is very interesting. I like this class; it is very interesting. I like this class, and it is very interesting. I like this class because it is very interesting. Because it is very interesting, I like this class. Fused (Run-on) Sentences Fused sentences happen when there are two independent clauses not separated by any form of punctuation. This error is also known as a run-on sentence. The error can sometimes be corrected by adding a period, semicolon, or colon to separate the two sentences. Incorrect: My professor is intelligent I've learned a lot from her. Correct: My professor is intelligent. I've learned a lot from her. My professor is intelligent; I've learned a lot from her. My professor is intelligent, and I've learned a lot from her. My professor is intelligent; moreover, I've learned a lot from her. Sentence Fragments Sentence fragments happen by treating a dependent clause or other incomplete thought as a complete sentence. You can usually fix this error by combining it with another sentence to make a complete thought or by removing the dependent marker. Incorrect: Because I forgot the exam was today. Correct: Because I forgot the exam was today, I didn't study. I forgot the exam was today. COMPLEX SENTENCE Independent Clause An independent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and verb and expresses a complete thought. An independent clause is a sentence. Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz. Dependent Clause A dependent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and verb but relies on another clause to complete its meaning. A dependent clause cannot be a sentence. Often a dependent clause is marked by a dependent marker word. When Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz . . . (What happened when he studied? The thought is incomplete.) Dependent Marker Word A dependent marker word is a word added to the beginning of an independent clause that makes it into a dependent clause. When Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz, it was very noisy. Some common dependent markers: after, although, as, as if, because, before, even if, even though, if, in and while. order to, since, though, unless, until, whatever, when, whenever, whether, Connecting dependent and independent clauses Subordinating conjunctions allow writers to construct complex sentences, which have an independent clause and a subordinate (or dependent) clause. Either clause can come first. The students acted differently whenever a substitute taught the class. Whenever a substitute taught the class, the students acted differently. Note that the clauses are separated with a comma when the dependent clause comes first. Some common subordinating conjunctions: after, as, before, once, since, until, and while. An independent or main clause can stand alone as a sentence. It has a subject and a verb and conveys a complete thought. The ball belongs to Alice. The ball rolled down the hill. The ball was red. A dependent or subordinate clause can’t stand alone as a sentence. It does have a subject and a verb, but it doesn’t convey a complete thought. It depends on other sentence elements (typically an independent clause) to give it meaning. Because the ball belonged to Alice After the ball rolled down the hill Since the ball was red These are incomplete sentences because they don’t convey a complete thought. Because the ball belonged to Alice, what? After the ball rolled down the hill, what happened? Since the ball was red, what? An adverbial clause often starts with a subordinating conjunction. A short list of subordinating conjunctions: Although, after, as, because, before, once, since, though, until, when, while A subordinate clause that stands alone is a sentence fragment. Students are taught to not use sentence fragments, but fiction writers use them all the time for effect and rhythm. “Why’d you steal the code?” “Because I can.” The dependent clause can come before the independent one, after it, or it can come in the middle of it, interrupting the independent clause. Comma use is partly dependent upon where the dependent clause falls in relation to the independent clause. Independent clauses often come first in our text, but putting dependent clauses first gives us variety in sentence construction. Relative clause There are two kinds of relative clause, which are distinguished by their use of the comma. A defining or restrictive clause cannot be omitted without affecting the sentence’s meaning. It is not enclosed with commas: Identical twins who share tight emotional ties may live longer. Implication: there are two groups of identical twins - those with tight ties and those without. The people who live there are really frightened. Implication: some people live there, others don’t. A clause that adds information of the form and he/she is, and it was, or otherwise known as (a non-restrictive or non-defining clause) needs to be enclosed with commas. If such a clause is removed the sentence retains its meaning: Identical twins, who are always of the same sex, arise in a different way. Implication: all identical twins are of the same sex. The valley’s people, who are Buddhist, speak Ladakhi. Implication: all the valley’s people are Buddhist. In restrictive relative clauses either which or that may be used in BE, but in non-restrictive only which is used. They did their work with a quietness and dignity which he found impressive. They did their work with a quietness and dignity that he found impressive. That book, which is set in the last century, is very popular with teenagers. Similar principles apply to phrases in parenthesis or apposition. A comma is not required where the item in apposition is restrictive or defining – in other words, when it defines which of more than one people or things is meant: The ancient poet Homer is credited with two great epics. My friend Julie is absolutely gorgeous. When the name and noun are transposed commas are required: Homer, the ancient poet, is credited with two great epics. Julia, my friend, is absolutely gorgeous. I met my wife, Dorothy, at a dance. Their only son, David, was killed in the war. Poppy, the baker’s wife, makes wonderful pies. Do not use a comma when what follows has become part of a name: Bob the Builder, Jack the Ripper. After an introductory clause or adverb When a sentence is introduced by an adverb, adverbial phrase, or subordinate clause, this is often separated from the main clause with a comma: Despite being married with five children, he reveled in his reputation as a rake. Surprisingly, Richard liked the tea. This is not essential if the introductory clause or phrase is a short one specifying time or location: In 2000 the hospital took part in a trial involving alternative therapy for babies. Before his retirement he had been a mathematician. A comma should never be used after the subject of a sentence except to introduce a parenthetical clause: The coastal city of Bordeaux is a city of stone. The primary reason the utilities are expanding their non-regulated activities is the potential of higher returns. Dependent Clause Before Independent Clause When an adverbial dependent clause comes before the independent clause, we put a comma after the dependent clause (between the clauses). We don’t have to give any consideration to the topic of essential or nonessential—when the dependent clause comes before the independent, use a comma to separate them. When I saw the destruction, I cried. After the ball, Cinderella had to run home. Although he turned down the job, the company did pay his travel expenses. After crashing his car into a fence, the police officer pleaded guilty to careless driving. Dependent Clause After Independent Clause When a dependent clause (we’re still talking adverbial clauses beginning with a subordinating conjunction) comes after the independent clause, most of the time there is no comma. I cried when I saw the destruction. Cinderella had to run home after the ball. The police officer pleaded guilty to careless driving after crashing his car into a fence. The company did pay Mark’s travel expenses, although he turned down the job.* The exceptions * There is a comma in the fourth example because the dependent clause begins with although, an adverb of concession. The adverbs of concession set up contrast clauses. Adverbs of concession include though, although, even though, and whereas. Use commas to introduce dependent clauses beginning with these words, even when the independent clause comes first. She said it boldly, although I didn’t believe her. My mother put on her dress, though it was still covered in mud. John got out after six months, whereas Martin had to serve his full two-year sentence. When while means whereas, it is being used as an adverb of concession and would be preceded by a comma after an independent clause. Think contrast. The delivery guy waited in the pouring rain while [as] the little boy counted out his pennies. The delivery guy waited at the door, while [whereas] his supervisor waited in the dry car. The subordinating conjunction because, when it begins a dependent clause after an independent clause, usually gets no comma. Yet there are two instances when because is preceded by a comma in this sentence position. First, when the independent clause contains a negative verb. We use commas in such sentences to eliminate possible confusion. She didn’t run toward the house because she was afraid. Without a comma, this sentence could be read two ways. But the reader has no way of knowing which reading is correct. Either she didn’t run toward the house due to her fear (because she was afraid, which is likely what we want to say) or she didn’t run toward the house not because she was afraid, but for some other reason, a reason not mentioned in this sentence. If a reason other than fear was involved, go ahead and spell that out. She didn’t run toward the house because she was afraid, but because she was eager to meet the ghost. But if you want the first meaning, using because to mean due to her fear, adding a comma lets the reader know the reason for not running was because of her fear. She didn’t run toward the house, because she was afraid. The second exception for using a comma before because is when the cause in because could be paired with the wrong element, creating confusion for the reader. Lauren suspected her brother-in-law robbed the bank because she had seen his mask in his car. X Lauren suspected her brother-in-law robbed the bank, because she had seen his mask in his car. Without a comma, this says that Lauren suspected that her brother-in-law robbed the bank on account of her seeing his mask, as if her seeing it led to his actions. With the comma, the sentence says that she suspected him because she’d seen the mask. Dependent Clause Within Independent Clause A dependent clause can be nestled inside an independent clause. When a dependent clause is within the independent one, it’s an interrupter. An interrupter simply breaks the flow of a sentence, and there are many different kinds, not just dependent clauses. A single word, a phrase, or a clause can interrupt an independent clause, and interrupters include adverbs, participial phrases, absolute phrases, nonessential clauses, appositives, digressions, parentheticals, commentary, and asides. Any time these items interrupt a sentence—interrupt an independent clause—they are nonessential elements and need to be separated from the independent clause with punctuation. We typically use commas both before and after most interrupters, yet you could use dashes or parentheses. The man, breathing heavily, couldn’t call out for help. Elton and Carl, recklessly and without warning, jumped off the roof. Tina, surprisingly, didn’t faint. Bettina, the strong one, did faint. My best friend, Jilly, is coming for the weekend. Tennessee and Georgia, because they couldn’t agree on water rights, went to war. The police officer, after crashing his car into a fence, pleaded guilty to careless driving. The information between the commas could be lifted out of the sentences and these sentences would still make sense in terms of both grammar and meaning. That is, taking out the dependent clauses would not negate the other parts of the sentence. The information between the commas is nonessential. The information may add details, but taking it out wouldn’t change the major thrust of the sentence or have readers trying to figure out what was going on. The sentences without the nonessential words, phrases, and clauses can stand on their own. To sum up, the inclusion or omission of a comma can change the sense. Some authors do not realize that this happens with ‘because’ and ‘in order to’. She said Auckland was attractive because he lived there (it was attractive because he lived there). She said Auckland was attractive, because he lived there (she said it because he lived there). He claimed that he had attended church, in order to avoid the penalties of the law. (he claimed this in order to avoid the penalties) He claimed that he had attended church in order to avoid the penalties of the law (he said this whas why he had attended church). Beware of the dangling participles: Having pitched the tents, the horses were fed and watered. Shot in a factory, Eisenstein moves his camera so that the machinery seems to come alive. Raining, I decided to take my umbrella with me.