Cray, Inglis Freeman (2007) Managing the Arts - Leadership Decision Making ..Dual Rationalities. Journal of Arts Mgt, Law Society, 36,4 ed2e171b4a15279c2fe43dfd3360533e

advertisement

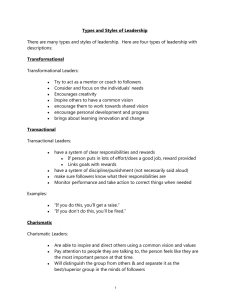

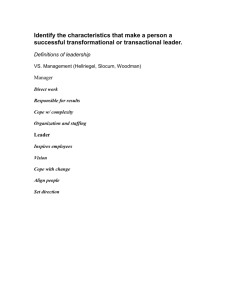

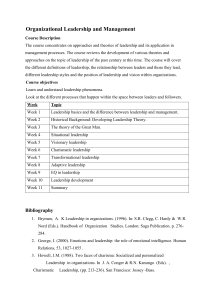

The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society ISSN: 1063-2921 (Print) 1930-7799 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjam20 Managing the Arts: Leadership and Decision Making under Dual Rationalities David Cray , Loretta Inglis & Susan Freeman To cite this article: David Cray , Loretta Inglis & Susan Freeman (2007) Managing the Arts: Leadership and Decision Making under Dual Rationalities, The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 36:4, 295-313, DOI: 10.3200/JAML.36.4.295-314 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.3200/JAML.36.4.295-314 Published online: 07 Aug 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1790 Citing articles: 6 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjam20 Managing the Arts: Leadership and Decision Making under Dual Rationalities DAVID CRAY, LORETTA INGLIS, AND SUSAN FREEMAN A lthough it is acknowledged that arts organizations are undergoing considerable changes in funding, governance, and competition, only recently have basic concepts of management been applied to problems within the arts sector. As a result, little is known about two critical functions of management— leadership and decision making. In this article, we argue that, although leadership and decision-making styles available to managers in the arts are similar to those in other industries, factors unique to the arts sector affect the manner in which they are enacted. The demands of arts stakeholders often conflict with a more business-like, or managerialist, management style and thus complicate leadership and decision making. In this article, we first describe the context of this discussion—arts organizations—and emphasize the increasing challenges they face. Second, we review the literature on leadership styles, positing that the particular leadership styles most likely to be found in the arts sector are charismatic, transactional, transformational, and participatory, each of which is suitable in particular circumstances. Third, we review literature concerning strategic decision-making processes and identify four key models—rational, political, David Cray is an associate professor in the Sprott School of Business at Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada. His research interests include decision making and international management. Loretta Inglis is a lecturer in the department of Management, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. Her research interests include leadership and management of nonprofit organizations. Susan Freeman is a senior lecturer in the department of Management, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. Her research interests include international business, particularly emerging markets, small firms, and the internationalization of services. Copyright © 2007 Heldref Publications Winter 2007 295 The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society incremental, and garbage can—and discuss the applicability of each in the arts sector. We argue that a close match between the organizational goals, environment, and leadership and decision-making styles is necessary for effective management of arts organizations today. To understand appropriate leadership and decision-making styles, given the specific tensions between the dual rationalities of aesthetic judgement and organizational efficiency, further research should include a more systematic approach, using existing concepts and models to understand precisely how arts organizations operate. MANAGERIAL CHALLENGES FACING ARTS ORGANIZATIONS Recently, the context of arts organizations has been shifting in response to changes in funding, governance, and competition. Many arts institutions have seen their governmental grants reduced, leaving them more dependent on donations from individuals and corporations, income from performances and exhibitions, and the efforts of volunteers. In many areas, especially those of marketing and fundraising, these new realities have demanded higher levels of professionalism from employees and more attention to managerial as opposed to artistic or aesthetic issues (Sicca and Zan 2005). Greater involvement with a wider variety of stakeholders has also increased pressure for more accountability and greater transparency in the governance procedures of nonprofit arts bodies. Overall, there has been a strong push to adopt procedures closer to those of profit-making firms. The considerable changes that are being implemented in arts organizations often have important effects on structures, processes, and personnel. Whereas some of the more technical segments of the organization may be shielded from these new realities, those that interact with external stakeholders may have to shift their focus and behavior dramatically. The pressure for visible change will impact most heavily on the leaders of such organizations. Because they represent the organization to its external stakeholders and serve as a link between the organization’s environment and its employees, top-level leaders normally experience tension between the agendas of these groups. When changes are required in arts organizations, differing opinions about the direction of change and the details of effective implementation exacerbate these tensions. Current movements in the arts industries have reshaped the roles of organizational leaders, forcing them, for example, to become more entrepreneurial (Mulcahy 2003). The pressures for change in the arts industry are substantial, but there are limitations on how far alterations may go and how fast they may be implemented (DiMaggio and Stenberg 1985). Because resources are almost invariably in short supply, initiatives that require extensive investment, especially those that require ongoing commitments through hiring specialized staff, may be delayed or 296 Vol. 36, No. 4 Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities shelved. The mission of the organization and its commitment to deliver artistic programs may also constrain reorientation efforts. One of the most vexing problems for arts organizations seeking to restructure lies in their ties with long-time supporters who may dislike change. Arts organizations wishing to attract new clientele by restructuring must do so without forfeiting the attributes that current supporters value (Evrard and Colbert 2000). Both administrators and those who study arts organizations are limited in their ability to deal with the problems induced by change due to a lack of empirical research in the area of arts management. Although some functional areas such as marketing have received considerable attention from researchers (Rentschler et al. 2002), there is only a dearth of comprehensive literature that addresses the problems of managing arts organizations. This reality, in part, reflects a lack of interest in the arts sector on the part of management researchers, who seldom address specific issues in arts organizations (Lohmann 2001). Even the arts management literature rarely discusses leadership and management functions (Evrard and Colbert 2000). Only recently have the basic concepts of management been applied to the problems of the arts sector, but the majority of these studies represent the loose application of concepts from other disciplines by those writing about the arts rather than thorough investigation by management researchers. Much of this basic information is derived from the general nonprofit literature (Lohmann 2001). Yet, one can make a strong case that arts organizations should be seen as distinct from other nonprofits. The strong influence of the artistic director and his or her emphasis on an artistic vision for the organization can conflict forcefully with the requirements of other managerial functions. The dual functions of guiding artistic endeavors and organizational administration, even in the best-run arts groups, fosters structural complexity, competing sets of goals, and multiple stakeholder claims. The distinct nature of arts organizations arises not simply from their artistic missions, but also from the complexity that multiple demands impose. One way that nonprofit organizations cope with their complexity is to introduce corporate models of management (Evrard and Colbert 2000; Palmer 1998; Sicca and Zan 2005). Like all nonprofits, arts organizations have traditionally been seen as lacking professional management and as being run by “social workers, health care professionals, foundation people, educators, participants in high arts and culture, advocacy and interest groups” (Young et al. 1993, 3). In response to the changing nature of their operations, organizations have slowly adopted for-profit management processes, often at the behest of their major stakeholders and the encouragement of academics and consultants, to be seen as professionally managed (Bryson 1995). Processes such as strategic planning, total quality management, and benchmarking have been introduced to improve organizational performance (Mulhare 1999). Nonetheless, many nonprofits Winter 2007 297 The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society have found these for-profit processes difficult to duplicate (Beerel 1997; Crittenden and Crittenden 2000). A number of factors, including the different stakeholders involved in the process, dislike of corporate models, and issues of leadership and general management, explain this difficulty (Bryson and Roering 1988; Crittenden and Crittenden; Lindenberg 2001; Santora and Sarros 2001). These difficulties, common in nonprofit organizations, are also likely to be present in nonprofit arts organizations. Two of the crucial managerial functions in a changing environment are leadership and strategic decision making. All organizational change puts pressure on leaders to ease the conflicts caused by transition to new forms and procedures while still capturing the benefits the change was designed to achieve. Thus, we will argue that, although the variety of required leadership roles is similar to those in other industries, the way that they are enacted involves factors unique to the arts sector. Similarly, the strategic decision-making process encounters forces, especially those of an aesthetic nature, that conflict with the more rationalist orientation inherent in the managerialist approaches that arts organizations are being urged to accept. Our aim, in both instances, is to draw heavily on the existing managerial literature to provide greater understanding of the range of roles that arts managers must fill while acknowledging the distinct nature of the environments they face. LEADERS IN ARTS ORGANIZATIONS Leadership of any nonprofit organization brings challenges that are more complex than those in a for-profit institution (Dym and Hutson 2005), and arts organizations appear to have particular difficulties because of the need to balance aesthetic considerations with ensuring the viability of the organization. Overall, leadership and leaders in arts organization are relatively unexplored topics; leadership is usually discussed in terms of best practice or in relation to the leading organization in a field, rather than in terms of individuals in key management positions (Tschirhart 1996). Yet the behavior of individuals in leadership roles is a major issue, as arts organizations frequently have both an artistic director and a managing director (or similar position). In some cases, one person performs both roles, but in larger organizations two people often lead the organization, sometimes from different perspectives (Evrard and Colbert 2000). The artistic director traditionally plays the dominant leadership role, and it is essential that the artistic direction of the organization enhances his or her reputation among peers. This can only result from the provision of the best possible artistic experience for the organization’s audience. The managing director’s role, on the other hand, is to establish and maintain the organization as an ongoing operation, and his or her reputation as a successful administrator depends on efficiency and effectiveness. The focus of a 298 Vol. 36, No. 4 Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities manager is to ensure the financial security and long-term survival of the organization; the primary focus of the artistic director is short-term artistic recognition. How does an arts leader best influence his or her colleagues and followers toward organizational change? Four basic styles appear to be relevant to strategic leadership in arts organizations: charismatic, transactional, transformational, and participatory. Charismatic Leadership The term “charisma” is commonly used to describe leaders who are able to have profound effects on their followers through the force of their personality and individual abilities (Conger and Kanungo 1998). A charismatic leader usually dominates within the organization, has a high level of self-confidence, and has a strong conviction in the righteousness of his or her beliefs. Such leaders have a powerful effect on their followers, inspiring trust, devotion, and a desire to emulate their values, goals, and behavior. Charismatic leadership is seen as particularly important for new and emerging organizations and also for those facing a significant change or crisis (Conger and Kanungo 1998). However, charismatic leadership also has negative effects on followers. Followers can develop an unhealthy dependence on the leader, diminishing their own ability for independent action. The desire to please the leader may also be seen as an obligation. Charismatic style is usually not appropriate, or less effective, in times of relative stability and is vulnerable to challenge if the leader’s decisions fail or other more credible rivals for leadership appear. Many arts organizations are founded by an individual with a passionate commitment to a particular art form and usually a sound reputation in the field. Such individuals are often extremely talented and strongly committed to the purpose of the organization. A typical pattern for arts organization under charismatic leadership begins with the founder; after the founder moves on, the organization is perpetuated by the artistic director, who influences others to follow the course of action he or she favors. The high levels of talent and commitment suggest that either the founder or a successor is likely to be recognized as a charismatic leader (Evrard and Colbert 2000). Arts organizations are likely to encounter problems if the charismatic leader departs, if he or she is seen to be making inappropriate decisions, or if another strong individual challenges the charismatic leader’s position, perhaps by championing a new style or approach. Transactional Leadership Traditional views of leadership effectiveness have focused on transactional leader behaviors (Bass 1985; Burns 1978). Transactional leadership is based on Winter 2007 299 The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society a leader-follower relationship predicated on mutually beneficial exchanges. One important dimension of transactional leadership is the use of contingent rewards, whereby leaders clarify expectations and provide resources and support in return for effort on the part of the follower. Leaders may also manage by exception, by enforcing rules to avoid mistakes, and by taking corrective action if deviations from standards occur. In one sense, arts organizations embrace transactional leadership. Producing a performance or launching an exhibition requires substantial operational planning. The effort required by both leaders and followers is considerable, and detailed management is required. On the other hand, managing creative people and delivering cultural products requires great sensitivity, and emphasis on meeting deadlines and completing administrative tasks can cause conflict. Overuse of transactional leadership can lead to complaints of managerialism and interference with artistic freedom. Transformational Leadership Contemporary leadership research focuses on the identification and examination of leadership behaviors that make followers more aware of the importance and values of task outcomes, activate their higher-order needs, and induce them to transcend self-interest for the sake of the organization (Yukl 2006). Transformational leadership behavior, according to Bass (1998), includes idealized influence, or charisma, but also the inspirational motivation of followers by articulating a vision for the future, intellectual stimulation of followers by encouraging the expression of new ideas and beliefs, and individualized consideration, where leaders deal with all their followers as individuals whose needs, abilities, and aspirations are valued (Avolio 1999; Bass 1996; 1997). Proponents of transformational leadership argue that such leaders can convince followers to perform beyond expected levels as a consequence of their influence. Followers are willing to exert extra effort because of their commitment to the leader, but also because of their intrinsic work motivation and the sense of purpose and mission that drives them to excel. This is of particular importance in arts organizations where many of the followers are artists themselves who want to be part of a worthwhile organization, to have their ideas valued, and to have their artistic abilities cherished. Participatory Leadership Participative leadership behavior occurs when leaders include followers in various aspects of the decision-making process (Yukl 2006). The common meaning of participatory leadership is when followers are involved in deci300 Vol. 36, No. 4 Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities sions through consulting or through meetings where information and ideas are exchanged before the leader makes the final decision. Participatory leadership behavior includes group discussion sessions, one-on-one meetings, obtaining information from followers, and asking opinions about decision alternatives or ideas about how strategies might be implemented. Because individuals need to be valued, the participatory style of leadership is also likely to be appropriate in arts organizations. These organizations usually include many employees and volunteers who are well educated, interested, and committed to the goals of the organization. Such participants usually wish to be consulted about decisions that will affect them; they may also wish to influence the progress of their organization in a more general manner. Employee involvement in decision making is important, as it is the employees who will implement decisions, thus their support is vital. The effectiveness with which members of an organization implement a decision depends on the extent to which they are committed to its success, and evidence clearly shows that people do support, and are motivated by, decisions they have helped to make. Although the participatory style may motivate organizational members, promote employee buy-in for decisions, and accelerate implementation, this style, especially when applied to major decisions, can slow the organization’s reaction time significantly. The types of organizations amenable to the participatory style are often more inclusive, thus increasing the number of individuals and groups who feel they have a right to be involved. This tendency is exacerbated in organizations with compressed hierarchies, a common structural form among nonprofit bodies. Leadership Styles in Arts Organizations Each of the styles described above has its advocates, but many researchers now believe that successful leaders match their personal styles to the culture of the organization and the demands of its environment. The strengths and weaknesses of each style make it suitable in some instances but inappropriate, or even deleterious, in others. There is considerable debate on the extent to which individuals can change their own styles, but it is clear that a mismatch between an individual’s leadership style and organizational needs or context can result in disaster, even for a leader who has previously been successful (Yukl 2006). A summary of the four styles discussed above is presented in table 1. All four styles of leadership may be appropriate for arts organizations under certain circumstances. The size of the organization, diversity of programs, internal political arrangements, relationships with external stakeholders, financial stability, institutional image, and a number of other factors will Winter 2007 301 302 Single leader who relies on personal attributes Leader-follower relationship based on mutual benefits Leader inspires followers to move self-interest Leader involves others in decision making and other leadership roles Transactional Transformational Participatory Characteristics Charismatic Style Slows decision making and other processes Focuses the organization Concentrates on the on immediate problems leader and ignores situational variables, particularly followers Promotes a sense of belonging; speeds implementation Applicability Appropriate in flat organizations with widely accepted goals Appropriate where the organization requires significant change Most appropriate in routine, bureaucratic organizations Can generate dependency; Most appropriate in small, success depends almost new organizations or solely on leader those in crisis Weaknesses Leadership is routinized; Followers become transition between calculative in leaders is less disruptive their commitments Promotes high levels of commitment; single, overriding vision Strengths TABLE 1. Four Leadership Styles for Decision Making The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society Vol. 36, No. 4 Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities impact the fit between the leader’s style and organizational effectiveness. Charismatic leadership may be most suitable during the initial stages of an organization’s life, although extreme crises may call for the same set of skills. Of course, true charismatic leadership is rare, as it depends on an individual’s personal characteristics. Transformational leadership, which relies more on skills than inherent qualities, is an alternative when the organization requires significant change. Like charismatic leadership, it often falters when the urgent need for concerted action has passed. Transactional leadership is the most stable of these styles, but may not be suited to many arts organizations because they seldom operate in a strictly routine manner. An important advantage of the transactional style lies in the fact that such leaders are readily available, as they can often be found within the organization itself. Participatory leadership offers the best fit for most arts organizations provided they are not undergoing a crisis. However, the slow pace of decision making this style fosters limits the ability of the organization to adapt to a dynamic environment. STRATEGIC DECISION MAKING IN ARTS ORGANIZATIONS One of the key functions of leaders is to set long-term goals for their organizations. Studies of strategic decision making have revealed numerous versions of the decision-making process that depend both on internal factors and the organization’s context (Eisenhardt 1989; Hickson et al. 1986). Thus, the role that leaders play in arriving at strategic decisions is under their control, to the extent that they can manage internal structures and procedures. Because the aim of a strategic decision is to position the organization relative to its environment, those factors, which are largely beyond the leader’s control, will play a large part in shaping not only the decision, but also the process through which it is made. For example, turbulent, fast-changing environments demand equally rapid decision processes focused on a small number of participants (Eisenhardt and Zbaracki 1992). In this section, we will briefly consider four models of strategic decision making and how they affect the leader’s role in the process. Rational Models Rational models of decision making posit a set of higher-level goals toward which the organization must advance. Once the higher-level goals are in place, the decision-making process consists largely of ranking various options often through some type of scoring system. The strategic option that achieves the highest score on the designated criteria or that maximizes a particular function is selected and implemented. The key to success in the rational mode is ensurWinter 2007 303 The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society ing that the proper criteria are selected and given appropriate weights. This approach is most appropriate in situations familiar to decision makers; that is, in cases where the criteria remain stable over time (Dean and Sharfman 1993). The rational model has received considerable criticism over the years on three major grounds (Eisenhardt and Zbaracki 1992). First, it assumes a level of stability in both goals and environmental context that is seldom warranted. Second, the organization is seen as a coherent and uniform whole, ignoring competing internal agendas. Third, the procedures inherent in the rational model do not take account of the perceptual biases and limitations that affect all managers. Despite these criticisms, versions of the rational model still dominate most management and planning texts. It also provides the official framework for decision making in most organizations, however far practices may diverge. Application of the rational model to arts organizations appears problematic largely due to the type of strategic decisions that must be made. The bases for artistic judgments are notoriously difficult to articulate, much less to reduce to quantitative measures. Even if such a rational system of artistic judgment could be developed, it seems unlikely that many of those involved in the arts would be willing to accept outcomes determined in such a manner. Given the lack of congruence between rational models and artistic judgment, it is somewhat ironic that the managerialist procedures being adopted by many arts organizations are predicated on a rationalist approach (Palmer 1998). Certainly the rhetoric of managerialism emphasizes efficiency and adherence to strict budgets, hallmarks of the rationalist approach to management. Sicca and Zan (2005) report on the difficulties that Italian state bodies encountered in implementing a rationalist model of funding for opera companies. Although it developed an elaborate funding formula, the Music Commission found itself unable to produce a scheme for rewarding quality, one of the main aims of the initial reform. The application of the rationalist approach in implementing a strategic decision collided with the artistic concerns of managers in the field, as well as with the notorious political contests among Italian arts organizations. Of course, in practice, no decision-making system is entirely rational; managers and other interested groups will attempt to influence the final decision by biasing options and criteria to favor their needs. It is the leader’s role to maintain some balance in this process. One of the most important products of the rational-decision process is the perception of fairness. A strategic choice is made not because of favoritism or through the exercise of power, but through systematically weighing the available options and choosing the option that is best not for a particular group but for the organization as a whole. Maintaining the appearance of fairness is another important leadership role under the rational model, which aids in implementing the final decision. 304 Vol. 36, No. 4 Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities An interesting application of the rational model to arts organizations has been developed by Krug and Weinberg (2005). They propose three criteria or dimensions on which organizations can measure programs: (a) contribution to the mission of the organization, (b) financial contribution, and (c) what they term “contribution to merit” (326) or the quality of the program. Their system highlights trade-offs between competing initiatives along the three axes, which leads less to the choice of a single option and more to a portfolio of programs that will produce an optimum outcome. Because the application is driven by evaluations solicited from individuals within the organization, there is a certain political element involved, but the logic of the system remains steadfastly rational. Decision Making as a Political Exercise Where the rationalist model tends to ignore the competing interests of actors, the political model sees the decision arena as populated with individuals and groups pursuing their own agendas. In this view, strategic decision making involves coalition building, negotiation, and trade-offs among competing goals. Typically this involves arguing that their particular ideas are best for the organization. In the long run, a political approach to strategic decision making involves moving key members of groups or coalitions into positions of power and influence. One of the early descriptions of political decision making in organizations emphasizes the control of information and communication as means of influencing the decision-making process (Pettigrew 1973). The agendas of interested groups may be based on a variety of considerations ranging from personal prestige to ideological purity (Schwenk 1988, 51). This has several implications. First, political decision making often turns on the choice of criteria rather than the evaluation of options. One of the most common political splits within organizations is among functional units. Strategic decisions typically have implications for all parts of the organization, with each area assessing benefits and costs from its own perspective. If one group is successful in imposing its own specific criteria, for example, the cost of the project or its impact on the image of the organization, then not only is the solution favored, but other possibilities may not even be considered. The diversity of groups also increases the likelihood that other criteria, including those not directly linked to the main issue, will impact the decision-making process (Hickson et al. 1986, 167). For example, the question of mounting an innovative program may be judged by groups not on its benefit to the organization but on who will receive credit for any success. Thus, the issues on the agenda may not be dictated by environmental concerns but by the aims of the groups involved. Thus, it is necessary to consider not only the selection of the issues to be discussed, but also they way that they are framed. For example, the problem Winter 2007 305 The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society of falling attendance can be interpreted either as requiring tighter control on expenditures or the need to offer more attractive programming. Control over the agenda takes on greater significance when decisions are overtly political. Theorists and practitioners often view political-decision processes negatively, but the inclusion of some political elements is almost inevitable when organizations include diverse groups with differing views. Recognizing these differences and dealing with them through negotiation and coalition building helps emphasize common concerns while acknowledging that legitimate differences exist. This, in turn, helps generate commitment for decision outcomes, which may be lacking if such differences are ignored or suppressed. Politicizing the decision process may have negative effects, especially when the concerns of some groups are not seen as legitimate (Eisenhardt and Bourgeois 1988). This stance not only alienates some members of the organization, but it also means that important decision criteria are ignored simply because they do not favor those who dominate the decision-making process. In extreme cases, the intrusion of political considerations may paralyze decision making if groups are too divided to negotiate. Although most observers agree that highly political organizations are less effective, some authors maintain that most political activity is benign, even beneficial (Dean and Sharfman 1993). One of the most common functions for the leader is to direct the decisionmaking process. Of course, this role is common to all approaches to strategic decision making, but it has particular significance when political considerations prevail. Forming committees and other bodies for making decisions will influence the outcome by including or excluding certain interests. A leader may seek to avoid the taint of political favoritism by acting as an impartial referee for the decision-making process. Once the rules of the game are set, the leader ensures that all sides abide by them. The leader may take a more active role by assembling a coalition that supports a particular strategic line. The breadth of the interests represented and the divisions within the organization will determine whether this role is seen as necessary leadership or irresponsible favoritism. This can be seen as a form of the transactional style in which the leader creates mutually beneficial arrangements with enough parties to generate sufficient political power. At the extreme, the leader may simply seek to augment the power of his or her position through the manipulation of the decision-making process. Indeed, some leaders have instigated strategic decision opportunities precisely for this purpose. This is most common when a new leader arrives or when a serious crisis threatens. The political model of strategic decision making has some applicability to arts organizations given the diversity of interests they normally embody. We can expect the political element to be more noticeable in arts organizations that are older, larger, and encompass more diverse programs. As organizations age, they typically move away from the central vision of the founder. Other mem306 Vol. 36, No. 4 Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities bers, especially those recruited from outside, bring their own interpretation of the mission, creating contrasting views. When organizations grow, there is less direct communication among members. Only those within subunits, or those doing similar tasks, regularly exchange views. Under these circumstances, it is natural that opinions diverge and that some groups are defined as either alien or inimical. In arts organizations, the existence of artistic versus operational units will naturally provide the potential for political division. Where these units overlap, as in small, young organizations, that potential will be limited; as they expand and diversify, it will become more pronounced. Big Decisions a Little at a Time: Incremental Decision Making Both the rational and political models of strategic decision-making processes are normally applied to major issues, those that involve important changes in direction for the organization. The decision topic is afforded considerable attention because the outcome is likely to have significant long-term effects on the organization’s well-being. In studying the decision-making behavior of large institutions, however, it appears that at least some organizations seldom take such large steps. Rather, they shift their strategies through a series of small steps that gradually increase their commitment to a specific course of action (Johnson 1987). This approach to strategy formulation, called “incrementalism,” was first observed in large government bureaus, but it has also been observed in commercial organizations. An incremental approach to strategic decision making has several distinct advantages, the most important of which lies in the commitment of resources. When strategic moves are implemented slowly, only limited resources are allocated. If the outcome of the change is negative or if the organizational context shifts, a new direction may be adopted with few serious consequences (Hickson et al. 1986, 99). For example, in a theater, several different types of innovative programming could be offered before settling on the one or two that would underpin a new strategic direction. The incremental approach thus provides a form of insurance because failure at any particular stage will cause only minimal disruption in the organization’s operations. Although the incremental approach allows stepwise implementation of strategic decisions, the slow pace required may have some negative effects. Making and implementing strategic decisions through a series of limited initiatives may leave the organization constantly trying to catch up with new developments. There is always the temptation in this system to refine new programs endlessly before committing to them fully. The potential for endless refining imposes constraints on the organization as a whole and may affect employees at the individual and unit levels. Those at lower levels in the organization often interpret small steps by upper management as a lack of commitment to a parWinter 2007 307 The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society ticular course of action. These employees would then hesitate to make an emotional commitment to any new goals or processes. This tendency will be especially pronounced if some initiatives have been rescinded in the past. Finally, the lack of a decisive strategic direction may frustrate or confuse external stakeholders who do not understand the underlying logic of incremental moves. An incremental approach to strategic decision making does not fit well with either charismatic or transactional decision-making leadership styles. Charismatic leaders must exhibit certainty in their approach to the future. Incremental solutions, especially when they involve retreat from certain positions, will hardly instill the trust that followers crave. If the relationship between leaders and their followers is based on mutual expectations, as embodied in the transactional style, the cost of constant change, even minor adjustments, may seem too stressful for the return. If the leaders of an organization consciously adopt an incremental stance toward strategy, they should be comfortable with either a participatory or transformational style. In both of these styles, the leader articulates a clear vision to others in the organization. This would allow leaders to outline the step-by-step nature of incrementalism, preparing their subordinates for the adjustments that will inevitably be required. In the transformational approach, this would most likely take the form of urging those at all levels of the organization to search for small gains that will further a general strategic thrust. The participatory style of leadership, perhaps the most appropriate for an incremental strategy, would involve subordinates more deeply in the generation of alternatives and their implementation, downplaying or even eliminating, the charismatic role of leaders. The leader’s role here would focus on encouraging diverse experiments, fostering those that were promising and persuading the organization as a whole to accept change as a constant. The Garbage Can: Strategy as a Pattern in Random Events A number of writers in the area have found both the rational and political models of the strategic decision process too deterministic (Das and Teng 1999; Dean and Sharfman 1993; Peterson 1997). They observed that strategic decision making was often initiated and influenced by unexpected changes in the organization itself or in its environment. Internally, the political processes that accompany strategic decisions are complicated by multiple agendas and complex, shifting alliances. Organizations containing a number of loosely coupled units without clear hierarchical strata are especially prone to adopting strategies that have no clear connection to past efforts or even, in some cases, to the problems they are purported to address. In the garbage can process, the arena for strategic decision making is conceptualized as a garbage can containing four elements: problems, solutions, 308 Vol. 36, No. 4 Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities participants, and choice opportunities (Cohen, March, and Olsen 1972; Das and Teng 1999). When an event occurs to spark a decision opportunity, existing problems and solutions are linked. This view of strategic decision making contrasts with those strategies discussed above in that solutions in the garbage can model are seen to exist before the problem is recognized or highlighted. For example, the director of a gallery may wish to add a space for experimental art. This solution may be attached to a number of problems—for example, falling attendance, criticisms of the gallery’s programs, or dissatisfaction by younger artists. The link between problem and solution can be generated by political coalitions (who may choose to promote a crisis to impose a solution), bureaucratic rules, or simple chance. It differs from the political approach in that strategic decisions are reactions to random events rather than a logical expression of specific agendas. It is difficult to evaluate leadership styles for their applicability to the garbage can model, given the strong role allocated to random events. Indeed the “organized anarchies” thought to be most prone to the emergence of such strategies, could hardly exist under the sway of a strong leader. The elements that make such leadership difficult, such as powerful internal constituencies, fluid membership (including volunteers), and external stakeholders with strong internal influence, are the same elements that contribute to the indeterminacy of the process. Charismatic and transformational leaders might emerge from such uncertainty, but their actions would almost inevitably reduce the random element by substituting their own powerful visions. A limited form of transactional leadership might be effective under these circumstances, but, because the leader tends to have limited power, the ability to reward subordinates would be constrained. In such situations, multiple leaders, each with his or her own constituency, would likely emerge. Participatory leadership might prove effective in an organization characterized by a garbage can model of strategic decision making. Given the inability of any one person to affect the outcome of the decision process, inviting a group of colleagues to involve themselves will not overcome the influence of randomness but may help govern reaction to the problems that arise. Participatory leadership in such a scenario would involve acknowledging the instability of the organization’s environment as a defining factor of the strategic outlook. This reactive, group-based type of strategic decision making has been observed in high-tech firms participating in rapidly changing markets (Eisenhardt and Bourgeois 1988). It is unlikely that the participatory style would be effective once firms grow beyond a certain size, as the number of individuals who would need to be engaged would become prohibitively large. Where the garbage can model accurately describes the decision-making process, the successful exercise of leadership will most likely be limited and local. The characteristics of the four approaches to strategic decision making are summarized in table 2. Winter 2007 309 The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society Most organizations, once they grow to the point where they achieve a fixed, multilevel structure, will partake of all four types of strategic decision-making processes. There are very few strategic decisions that do not have some political element. It would also be unusual to observe a strategic-decision process that is entirely rational or that completely follows the random path of the garbage can. What is important is the dominant elements in the approach—the way participants perceive the forces shaping their strategic destiny. If organizational members believe that process is political, they will employ coalitions to promote their interests. An organization that normally uses an incremental approach will be unlikely to generate long-term plans. If a leader wishes to alter the mode of strategic decision making, it will involve significant changes in belief as well as behavior. An examination of the “appropriate leadership style” column in table 2, shows that the transactional approach is appropriate under both the bureaucratic strictures of the rational approach and the more dynamic arrangements of the political. The nature of the exchange between leader and followers will be different under the two approaches, but the logic of leadership remains the same. If an incremental approach is used, participatory leadership facilitates the generation of ideas and feedback crucial to strategic success. If the changes are provoked by a crisis, the transformational style may succeed, but the leader would have to be exceptionally adroit to maintain high levels of commitment through a series of small advances and occasional setbacks. To the extent that any leadership style functions in the random world of the garbage can, the importance of information sharing makes the participatory leadership model the most likely. Charismatic leadership might emerge from a truly random organizational context, but such leaders normally make all important decisions on their own, making the process an individual rather than organizational one (Conger and Kanungo 1998). CONCLUSION In this article, we have attempted to match some recognized models of leadership with the characteristics of arts organizations. The four models discussed are appropriate in some circumstances, but no single leadership style will be successful in all situations. Given the dynamic environment that most arts organizations face, shifts in appropriate leadership styles will likely be necessary. This implies that arts organizations may require changes in leaders more often than other types of organizations. Equally, it might suggest that leaders who can shift easily from one style to another would be more suitable for leadership roles in the arts than those who are wedded to a single approach. To address these and related problems, research that examines leadership activities in the arts should move away from prescriptions to analyses 310 Vol. 36, No. 4 Winter 2007 Strengths Process is stable, clear, and transparent All interested parties participate; surfaces interests and agendas Allows multiple initiatives; provides for small gains Takes advantage of existing solutions Approach Rational Political Incremental Garbage can No coherent strategy emerges Slow; may confuse organizational members May lead to overly politicized decision processes Process may become inflexible; tends to ignore sectoral interests Weaknesses TABLE 2. Four Approaches to Strategic Decision Making Transactional with stable exchange arrangements Appropriate leadership style Fits with “organized anarchy” nature of many arts organizations Useful for organizations with multiple programs Participatory Participatory; transformational, but level of commitment may decline with slow rate of change Exists in all organizations; Transactional with seldom optimal as dynamic coalitions a dominant form Applicable to larger, more bureaucratic organizations Applicability to arts organizations Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities 311 The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society of actual leaders’ activities and styles and their relationships to characteristics of the organization and its environment. An examination of different models of strategic decision making reveals a similar result. Many arts organizations espouse participatory styles of leadership, a style appropriate only for incremental and garbage can models of decision making, neither of which provide the strong strategic direction that most arts organizations require. Rational and political models certainly exist in many arts organizations, but both have liabilities that may inhibit effective strategic performance over the long term. Given the lack of empirical research into these problems and that, aside from the odd case included in larger studies, there are virtually no detailed descriptions of strategic decisions in the arts, it is not even possible to describe how such decisions are made, much less offer advice to boards and managers as to how they should proceed. Research outlining what does occur as strategic decisions are made is necessary before improvements or alternatives can be suggested. As pressure to adopt more managerialist approaches increases, arts organizations and their leaders have little guidance on how to proceed. Ideological attacks on corporatist procedures will avail little without viable alternatives to propose. Much of the sparse literature in arts management is framed in terms of “best practice” based on a few isolated cases. A more systematic approach is needed, one that uses existing concepts and models to understand precisely how arts organizations operate. When we understand how well current theory fits the practice of arts management, we will be better positioned to propose a coherent research agenda to support the practice of management in the arts. KEYWORDS arts management, arts organizations, decision-making process, leadership styles REFERENCES Avolio, B. J. 1999. Full leadership development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bass, B. M. 1985. Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press. ———. 1996. A new paradigm of leadership: An inquiry into transformational leadership. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. ———. 1997. Does the transactional-transformational paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? American Psychologist 52:130–39. ———. 1998. Transformational leadership: Industry, military and educational impact. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Beerel, A. 1997. The strategic planner as prophet and leader: A case study concerning a leading seminary illustrates the new planning skills required. Leadership and Organization Development Journal 18 (3): 136–44. Bryson, J. 1995. Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Bryson, J. M., and W. D. Roering. 1988. Initiation of strategic planning by governments. Public Administration Review 48:995–1004. 312 Vol. 36, No. 4 Managing the Arts: Leadership under Dual Rationalities Burns, J. M. 1978. Leadership. New York: Harper and Row. Cohen, M. D., J. G. March, and J. P. Olsen. 1972. A garbage can model of organizational choice. Administrative Science Quarterly 17:1–25. Conger, J. A., and R. Kanungo. 1998. Charismatic leadership in organizations. New York: Sage. Crittenden, W. F., and V. L. Crittenden. 2000. Relationships between organizational characteristics and strategic-planning processes in nonprofit organizations. Journal of Managerial Issues 12 (2): 150–68. Das, T. K., and B. S. Teng. 1999. Cognitive biases and strategic decision processes: An integrative perspective. Journal of Management Studies 36 (6): 587–600. Dean, J. W., and M. P. Sharfman. 1993. Procedural rationality in the strategic decision-making process. Journal of Management Studies 30 (4): 587–610. DiMaggio, P., and K. Stenberg. 1985. Why do some theatres innovate more than others? An empirical analysis. Poetics 14:107–22. Dym, B., and H. Hutson. 2005. Leadership in nonprofit organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal 32 (3): 107–22. Eisenhardt, K. M., and L. J. I. Bourgeois. 1988. Politics of strategic decision making in highvelocity environments. Academy of Management Journal 31 (4): 737–70. Eisenhardt, K. M., and M. J. Zbaracki. 1992. Strategic decision making. Strategic Management Journal 13 (8): 17–37. Evrard, Y. and F. Colbert 2000. Arts management: A new discipline entering the millennium? International Journal of Arts Management 2 (2): 4–13. Hickson, D. J., R. Butler, D. Cray, G. R. Mallory, and D. C. Wilson. 1986. Top decisions: Strategic decision making in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Johnson, G. 1987. Strategic change and the management process. Oxford: Blackwell. Krug, K., and C. B. Weinberg. 2005. Mission, money, and merit: Strategic decision making by nonprofit managers. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 14 (3): 325–42. Lindenberg, M. 2001. Are we at the cutting edge or the blunt edge? Improving NGO organizational performance with private and public sector strategic management frameworks. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 11 (3): 247. Lohmann, R. 2001. Editor’s notes. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 11 (3): 399–403. Mulcahy, K. V. 2003. Entrepreneurship or social Darwinism? Privatization and American cultural patronage. Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 33 (3): 165–84. Mulhare, E. M. 1999. Mindful of the future: Strategic planning ideology and the culture of nonprofit management. Human Organization 58 (3): 323–30. Palmer, I. 1998. Arts managers and managerialism: A cross-sector analysis of CEOs’ orientation and skills. Public Productivity and Management Review 2 (4): 433–522. Peterson, R. S. 1997. A directive leadership style in group decision making can be both virtue and vice: Evidence from elite and experimental groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 (5): 1107–121. Pettigrew, A. M. 1973. The politics of organizational decision making. London: Tavistock. Rentschler, R., J. Radbourne, R. Carr, and J. Rickard. 2002. Relationship marketing, audience retention and performance arts organisation viability. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 7 (2): 118–30. Santora, J. C., and J. C. Sarros. 2001. CEO tenure in nonprofit community-based organizations: A multiple case study. Career Development International 6 (1): 56–60. Schwenk, C. R. 1988. The essence of strategic decision making. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Sicca, L. M., and L. Zan. 2005. Much ado about management: Managerial rhetoric in the transformation of Italian opera houses. International Journal of Arts Management 7 (3): 46–64. Tschirhart, M. 1996. Artful leadership: Managing stakeholder problems in nonprofit arts organizations. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Young, D. R., R. M. Hollister, V. A. Hodgkinson, and Associates, eds. 1993. Governing, leading and managing nonprofit organizations: New insights from research and practices. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Yukl, G. 2006. Leadership in organizations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Winter 2007 313