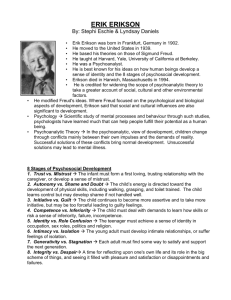

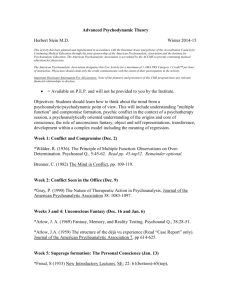

Psychoanalytic Approaches: Freud & Modern Psychotherapy

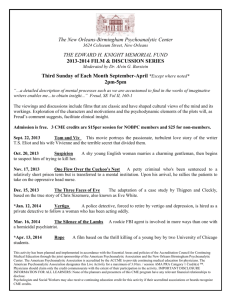

advertisement