Bank Deposit Types: Transaction & Savings Accounts Explained

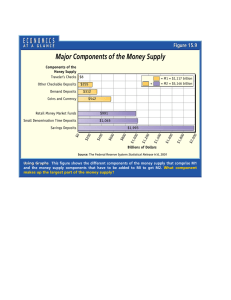

advertisement

Types of Deposits Offered by Banks and Other Depository Institutions The number and range of deposit services offered by depository institutions are impressive indeed and often confusing for customers. Like a Baskin-Robbins ice cream store, deposit plans designed to attract customer funds today come in 31 flavors and more, each plan having features intended to closely match business and household needs for saving money and making payments for goods and services. Transaction (Payments or Demand) Deposits One of the oldest services offered by depository institutions has centered on making payments on behalf of customers. This transaction, or demand, deposit service requires financial-service providers to honor immediately any withdrawals made either in person by the customer or by a third party designated by the customer to be the recipient of funds with- drawn. Transaction deposits include regular noninterest-bearing demand deposits that do not earn an explicit interest payment but provide the customer with payment services, safe- keeping of funds, and recordkeeping for any transactions carried out by check, card, or via an electronic network, and interest-bearing demand deposits that provide all the foregoing services and pay interest to the depositor as well. Noninterest-Bearing Transaction Deposits Interest payments have been prohibited on regular checking accounts in the United States since passage of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. Congress feared at the time that paying interest on immediately withdrawable deposits endangered bank safety- a proposition that researchers have subsequently found to have little support. However, demand (transaction) deposits are among the most volatile and least predictable of a depository institution's sources of funds, with the shortest potential maturity, because they can he withdrawn without prior notice. Most noninterest-bearing demand deposits are held by business firms. Interest-Bearing Transaction Deposits Many consumers today have moved their funds into other types of transaction deposits that pay at least some interest. Beginning in New England during the 1970s, hybrid checking-savings deposits began to appear in the form of negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts. NOWs are interest-bearing savings deposits that give the offering depository institution the right to insist on prior notice before the customer withdraws funds. Because this notice requirement is rarely exercised, the NOW can be used just like a checking (transaction) account to pay for purchases of goods and services. NOWs were permitted nationwide beginning in 1981 as a result of passage of the Depository Institutions Deregulation Act of 1980. However, they can be held only by individuals and nonprofit institutions. When NOWs became legal nationwide, the U.S. Congress also sanctioned the offering of automatic transfers (ATS), which permit the customer to preauthorize a depository institution to move funds from a savings account to a transaction account in order to cover overdrafts. The net effect was to pay interest on transaction balances roughly equal to the interest earned on a savings account. Two other important interest-bearing transaction accounts were created in the United States in 1982 with passage of the Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act. Banks and thrift institutions could offer deposits competitive with the share accounts offered by money market funds that carried higher, unregulated interest rates and were backed by a pool of high-quality securities. The result was the appearance of money market deposit accounts (MMDAs) and Super NOWS (SNOWs), offering flexible money marker interest rates but accessible via check or preauthorized draft to pay for goods and services. MMDAs are short-maturity deposits that may have a term of only a few days, weeks, or months, and the offering institution can pay any interest rate that is competitive enough to attract and hold the customer's deposit. Up to six preauthorized drafts per month are allowed, but only three withdrawals may be made by writing checks. There is no limit to the personal withdrawals the customer may make (though service providers reserve the right to sec maximum amounts and frequencies for personal withdrawals). Unlike NOWS, MMDAs can be held by businesses as well as individuals. Super NOWs were authorized at about the same time as MMDAs, but they may be held only by individuals and nonprofit institutions. The number of checks the depositor may write is not limited by regulation. However, offering institutions post lower yields on SNOWs than on MMDAs because the former can be drafted more frequently by customers. Incidentally, federal regulatory authorities classify MMDAs today not as transaction (payments) deposits, but as savings deposits. They are included in this section on transaction accounts because they carry check-writing privileges. Nontransaction (Savings or Thrift) Deposits Savings deposits, or thrift deposits, are designed to attract funds from customers who wish to set aside money in anticipation of future expenditures or financial emergencies. These deposits generally pay significantly higher interest rates than transaction deposits do. While their interest cost is higher, thrift deposits are generally less costly to process and manage. Just as depository institutions for decades offered only one basic transaction deposit- the regular checking account-so it was with savings plans. Passbook savings deposits were sold to household customers in small denominations (frequently a passbook deposit could be opened for as little as $5), and withdrawal privileges were unlimited. While legally a depository institution could insist on receiving prior notice of a planned withdrawal from a passbook savings deposit, few institutions have insisted on this technicality because of the low interest rates paid on these accounts and because passbook deposits tend to be stable anyway, with liccle sensitivity to changes in interest rates. Individuals, non- profit organizations, and governments can hold savings deposits, as can business firms, but in the United States businesses cannot place more than $150,000 in such a deposit. Some institutions offer statement savings deposits, evidenced only by computer entry. The customer can get monthly printouts showing deposits, withdrawals, interest earned, and the balance in the account. Many depository institutions, however, still offer the more traditional passbook savings deposit. where the customer is given a booklet showing the account's balance, interest earnings, deposits, and withdrawals, as well as the rules that bind both depository institution and depositor. For many years, wealthier individuals and businesses have been offered time deposits, which carry fixed maturity dates (usually covering 30, 60, 90, 180 or 360 days) with fixed interest rates. More recently, time deposits have been issued with interest rates adjusted periodically (such as every 90 days, known as a leg or roll period). Time deposits must carry a minimum maturity of seven days and cannot be withdrawn before that. Time deposits come in a wide variety of types and terms. However, the most popular of all time deposits are CDs-certificates of deposit. CDs may be issued in negotiable form-the $100,000plus instruments purchased principally by corporations and wealthy individuals that may be bought and sold any number of times prior to reaching their maturity—or in nonnegotiable formsmaller denomination accounts that cannot be traded prior to maturity and are usually acquired by individuals. Innovation has entered the CD marketplace recently with the development of bump-up CDs (allowing a depositor to switch to a higher interest rate if market interest rates rise); step-up CDs (permitting periodic upward adjustments in promised interest rates); and liquid CDs (allowing the depositor to withdraw some of his or her funds without a withdrawal penalty). In 1981, with passage of the Economic Recovery Tax Act, Congress opened the door to yet another deposit instrument-retirement savings accounts. Wage earners and salaried individuals were granted the right to make limited contributions each year, tax free, to an individual retirement account (IRA), offered by depository institutions, brokerage firms, insurance companies, and mutual funds, or by employers with qualified pension or profit-sharing plans. There was ample precedent for the creation of IRAs; in 1962, Congress authorized financial institutions to sell Keogh plan retirement deposits, available to self-employed persons. Unfortunately for depository institutions and their customers interested in IRAs, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 restricted the tax deductibility of additions to an IRA account, which reduced their growth rate somewhat, though Keogh deposits retained full tax benefits. Then, in August 1997 the U.S. Congress, in an effort to encourage saving for retirement, purchases of new homes, and childrens' education, modified the rules for IRA accounts, allowing individuals with higher incomes to make annual tax-deductible contributions to their retirement accounts and families to set up new education savings accounts that could grow tax free until needed to cover college tuition and other qualified educational expenses. Finally, the Tax Relief Act of 1997 created the Roth IRA, which allows individuals to make nontax-deductible contributions to a savings fund that can grow tax free and also pay no tax on their investment earnings when withdrawn. Today depository institutions in the United States hold about a quarter of all IRA and Keogh retirement accounts outstanding, ranking second only to mutual funds. The great appeal for the managers of depository institutions is the high degree of stability of IRA and Keogh deposits-financial managers can generally rely on having these funds around for several years. Moreover, many IRAs and Keoghs carry fixed interest rates-an advantage if market interest rates are rising allowing depository institutions to earn higher returns on their loans and investments that more than cover the interest costs associated with IRAs and Keoghs. (These retirement accounts were made more attractive to the public in 2006 when the U.S. Congress voted to increase FDIC insurance coverage to $250,000 for qualified retirement-plan deposits.)