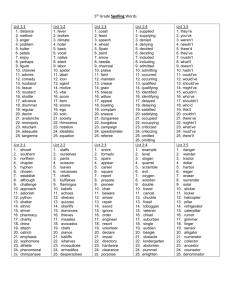

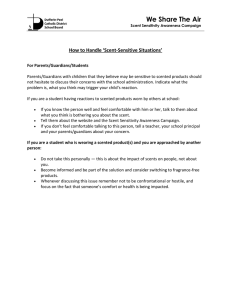

Journal of Environmental Psychology 57 (2018) 83e86 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Environmental Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jep The impact of coffee-like scent on expectations and performance Adriana Madzharov a, *, Ning Ye b, Maureen Morrin b, Lauren Block c a School of Business, Stevens Institute of Technology, 1 Castle Point on Hudson, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA Fox School of Business, Temple University, 1801 Liacouras Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19122-6083, USA c Baruch College, The City University of New York, One Bernard Baruch Way, New York, NY 10010, USA b a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Received 22 August 2017 Received in revised form 14 April 2018 Accepted 21 April 2018 Available online 23 April 2018 The present research explores the effect of an ambient coffee-like scent (versus no scent) on expectations regarding performance on an analytical reasoning task as well as on actual performance. We show that people in a coffee-scented (versus unscented) environment perform better on an analytical reasoning task due to heightened performance expectations (Study 1). We further show that people expect that being in a coffee-scented environment will increase their performance because they expect it will increase their physiological arousal level (Study 2). Our results thus demonstrate that a coffee-like scent (which actually contains no caffeine) can elicit a placebo effect. © 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Handling Editor: Florian Kaiser Keywords: Olfaction Performance Coffee-like scent Placebo effects 1. Introduction Many people experience the scent of coffee on a daily basis: in the workplace, at coffee shops, and in retail and service environments. Coffee houses such as Starbucks are known as the “third place” where people spend hours of their day working, socializing, or relaxing while immersed in a coffee-scented atmosphere (Oldenburg, 1989, pp. 39; Walton, 2012, pp. 1). Beyond stand-alone coffee shops, numerous retailers have built coffee counters into many of their outlets (e.g., Uniqlo, Club Monaco; Cheng, 2014). Given the prevalence and popularity of coffee-scented environments in people’s daily lives, it is important to understand how coffee scent might influence behavior. Can merely smelling a coffee-like scent without actually ingesting coffee have an effect on people’s behavior? The vast majority (80%) of the world’s population consumes caffeinated products such as coffee or tea every day, making caffeine “the single most widely consumed psychoactive ingre€ther & Giesbrecht, 2013, pp. 251). Studies suggest that dient” (Eino ingesting caffeine can enhance self-reported levels of alertness and * Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: adriana.madzharov@stevens.edu (A. Madzharov), ning.ye@ temple.edu (N. Ye), maureen.morrin@temple.edu (M. Morrin), lauren.block@ baruch.cuny.edu (L. Block). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.04.001 0272-4944/© 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. feelings of “energy,” and decrease perceived mental fatigue (Glade, 2010). In addition, caffeine has been shown to boost performance on tasks requiring sustained vigilance, and improve accuracy in €ther solving reasoning problems and making correct decisions (Eino & Giesbrecht, 2013; Glade, 2010; Smith, 2002). We posit that because of these well-known effects of coffee and caffeine, people will associate not only the ingestion of coffee but merely the smell of coffee with the same types of effects. Prior research has shown that ambient scent can enhance people’s ability to recognize and recall brand stimuli (Morrin & Ratneshwar, 2003) and promote approach behavior online (Vinitzky & Mazursky, 2011). The scent literature has also established that scents can bias perceptions and prime certain behaviors because of the se, Poels, Janssens, & De mantic associations they evoke (Douce guen, 2012; Krishna, Elder, & Caldara, 2010; Backer, 2013; Gue Madzharov, Block, & Morrin, 2015). In a similar way, we propose that coffee scent will be associated with the positive effects that caffeine is known to have on alertness and behavioral performance. Specifically, we propose that an ambient coffee-like scent will produce a placebo effect such that it will lead people to feel and behave in ways similar to drinking coffee. Thus, we extend knowledge on ambient scents by identifying for the first time coffee-like scent as an environmental stimulus that can influence behavior. A placebo is “an inert substance or procedure that alters one’s physiological or psychological response” (Geers, Kosbab, Helfer, Weiland, & Wellman, 2007, pp. 563). A placebo effect is “a 84 A. Madzharov et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 57 (2018) 83e86 positive outcome resulting from the belief that a beneficial treatment has been received” (Beedie & Foad, 2009, pp. 314). Placebo effects, from both the actual and perceived ingestion of caffeine, have been demonstrated. In one study (Beedie, Stuart, Coleman, & Foad, 2006), competitive cyclists were told they would receive in random order a placebo, a low dose of caffeine, and a high dose of caffeine (when in fact all were placebos), and their cycling power would be measured after each treatment. The authors found a dose-response relationship such that cycling improved with increases in the perceived doses of caffeine (Beedie et al., 2006, pp. 2160). Expectancy theory describes how individuals learn relationships among events via repeated exposure, over time (e.g., when A occurs, B occurs). Such learning allows individuals to predict outcomes in their environment (e.g., if A is observed to have occurred, B is expected to occur). Expectancy theory thus helps to explain placebo effects (Rescorla, 1988). Expectancy is the “experienced likelihood of an outcome or an expected effect” (Price, Finniss, & Benedetti, 2008, p. 571). What seems to be critical in placebo studies is not whether or not an individual is in the placebo or true treatment group, but whether or not the individual expects the treatment they receive will work (Price et al., 2008). Thus, it is largely the expectation or belief that the placebo will work that elicits the expected outcome. In the present research, expectancy is the extent to which a participant expects that smelling a coffee-like scent will enhance their performance on an analytical reasoning task. We thus extend prior research by showing that merely smelling a coffee-like scent leads to a placebo effect. We propose: H1. A coffee-like ambient scent (vs. no scent) will lead to improved performance on an analytical reasoning task. This effect will be mediated by higher performance expectations. 2. Study 1 2.1. Method 2.1.1. Design and subjects One hundred and fourteen (87% aged 18-21, 41% female) undergraduate business students participated for course credit in a study that was run, in groups of about 30, as a single factor (ambient scent: yes ¼ coffee-like scent, no ¼ unscented control) between-subjects design with random assignment to condition. 2.1.2. Procedure The experiment was conducted in a computer laboratory where participants entered either a coffee-like-scented or unscented environment and filled out a computer survey. We used a commercial electric diffuser to emit the coffee-like scent into the room (Madzharov et al., 2015). The scent smelled like coffee but contained no actual caffeine or other stimulants. The scent diffuser (kept hidden from view) was run for five minutes before the beginning of each scented session, and then was used to emit the odor every 15 s during the experimental sessions. After entering the scented (or unscented) room, participants were told that they would take part in an analytical reasoning task. While in the room, participants indicated their performance expectations (“How confident are you that you will do well on the task?”; “How well do you expect to do on the task?”; “How certain do you feel you will score highly on the task?”; from 1 ¼ not at all to 7 ¼ very; a ¼ 0.97). Then they completed the analytical reasoning task, which consisted of ten multiple-choice algebraic math problems from the GMAT (Graduate Management Admission Test), which the subject population was expected to be familiar with, and which has previously been used to measure performance (Ilyuk & Block, 2015). Performance was measured by the number of correct responses (out of ten possible). To minimize demand effects, participants were asked questions about the ambient scent only after responding to the other measures. They were asked whether they noticed any scent when they first came into the room (yes, no) and whether they noticed any scent right now (yes, no). The majority of participants in the coffeelike scent condition reported they remembered noticing a smell when they first came in (63%), and noticed a scent at the end of the survey (70.4%). Finally, participants answered demographic questions and a hypothesis probe. 2.2. Results An ANOVA on expectations with ambient scent as a betweensubjects factor was significant (F(1, 112) ¼ 9.56, p < .01, h2 ¼ 0.079). Participants in the coffee-like scent condition expected to perform better than those in the unscented control (MCoffeeLikeScent ¼ 4.94, SD ¼ 1.45 vs. MNoScent ¼ 4.18, SD ¼ 1.73). An ANOVA on performance with ambient scent as a betweensubjects factor was significant (F(1, 112) ¼ 11.83, p < .01, h2 ¼ 0.096). Participants in the coffee-like scent condition scored higher than those in the unscented control (MCoffeeLikeScent ¼ 5.44, SD ¼ 1.95 vs. MNoScent ¼ 4.22, SD ¼ 1.86). Using standardized variables, we performed a mediation test using a bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (Hayes’ Model 4, Hayes & Preacher, 2013), with scent as the independent factor (unscented control ¼ 0, coffee-like scent ¼ 1), expectations as the mediator, and the number of correct responses on the GMAT task as the dependent variable. The results showed a significant indirect effect of scent on performance via expectations (bIndirectEffect ¼ 0.13, 95% CI [0.03, 0.29]), but the results indicated only partial mediation. The analysis revealed that scent condition predicted expectations about performance (bScentToExpectations ¼ .56, p < .01) and that expectations predicted actual performance (bExpectationsToPerformance ¼ .24, p < .01; see Fig. 1). We conducted a follow-up study to better understand the underlying process. We wanted to see whether people expect that a coffee scent would improve performance because they believe it would lead to higher levels of physiological arousal (an effect traditionally associated with the ingestion of caffeine). In Study 2, we ask people what the effect would be of being in an environment with a regular coffee scent (or a decaffeinated coffee scent, a floral scent, or no scent at all). In this study we also seek to understand whether the imagined presence of any scent would have a similar effect on expectations regarding both performance and physiological arousal. 3. Study 2 3.1. Method 3.1.1. Design and subjects Two hundred and eight participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk took part for a small payment (Agemean ¼ 33, SD ¼ 9.70; 55% female) in a single-factor design (imagined scent condition: regular coffee, decaffeinated coffee, floral, no scent control), with random assignment. 3.1.2. Procedure We asked participants to imagine they were about to perform on an analytic reasoning task in the presence of either: regular coffee scent, decaffeinated coffee scent, floral scent, or no scent. Participants were asked to indicate how alert and energetic they A. Madzharov et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 57 (2018) 83e86 85 Effects of Coffee-Like Scent (vs. No Scent) on Performance via Expectations (Study 1) Expectations about Performance = .56, SE=.18 t =3.09, p < .01 Scent (Coffee-Like Scent = 1, No Scent = 0) = .24, SE=.09 t = 2.62, p = .01 Total Effect: = .62, SE=.18 t = 3.44, p <.01 GMAT Test Performance Direct Effect: = .48, SE=.18 t = 2.65, p <.01 Note: analysis was conducted with standardized variables. Fig. 1. Effects of coffee-like Scent(vs. No scent) on performance via expectations (study 1). would feel (“I will feel energetic”; “ I will feel alert”; on 7-point scales from 1 ¼ not at all to 7 ¼ very), as a measure of expected physiological arousal. We averaged the answers to the two items measuring the expected physiological arousal to create a single index (r ¼ 0.96, p < .001). We also measured their expectations about performance (same three items as in Study 1; a ¼ 0.87). 3.2. Results An ANOVA on expected physiological arousal as a function of imagined scent condition was significant (F(3, 204) ¼ 14.43, p < .01, h2 ¼ 0.18). The LSD post-hoc tests showed that participants believed they would feel more physiologically aroused in the regular coffee scent condition than in any of the other conditions (MRegularCoffeeScent ¼ 5.25, SD ¼ 1.40 vs. MDecafCoffeeScent ¼ 4.56, SD ¼ 1.23, p < .01; vs. MFloralScent ¼ 4.59, SD ¼ 1.79, p < .01; vs. MNoScent ¼ 3.62, SD ¼ 1.39, p < .01). The decaffeinated and floral scent conditions did not differ from each other (p ¼ .90) but were both greater than the no scent control (ps < .01). A similar ANOVA on expectations revealed a significant effect (F(3, 204) ¼ 8.22, p < .01, h2 ¼ 0.11). The LSD post-hoc test showed that participants in the regular coffee scent condition had higher performance expectations than those in the other conditions (M SD ¼ 1.24 vs. MDecafCoffeeScent ¼ 4.43, RegularCoffeeScent ¼ 4.98, SD ¼ 1.21, p < .05; vs. MFloralScent ¼ 4.36, SD ¼ 1.05, p < .01; vs. MNoScent ¼ 3.92, SD ¼ 0.96, p < .01). The decaffeinated and floral scent conditions did not differ from each other (p ¼ .80) but were both greater than the no scent control (ps < .05). Using standardized variables, mediation analysis showed that participants’ beliefs regarding their physiological arousal fully mediated the effect of imagined regular coffee scent (no scent ¼ 0, regular coffee scent ¼ 1) on performance expectations (bIndirectEffect ¼ 0.80, 95% CI ¼ [0.52, 1.09]; see Fig. 2 for details). Expected physiological arousal also fully mediated the imagined effects of regular (coded 1) versus decaffeinated (coded 0) coffee scent (bIndirectEffect ¼ 0.41, 95% CI ¼ [0.11, 0.75]; bScentToArousal ¼ 0.49, p < .01; bArousalToPerformance ¼ .84, p < .01) and of regular coffee (coded 1) versus floral (coded 0) scent (bIndirectEffect ¼ 0.38, 95% CI ¼ [0.11, 0.66]; bScentToArousal ¼ 0.47, p < .01; bArousalToPerformance ¼ .81, p < .01) on performance expectations. 4. General discussion We contribute to current understanding of how ambient scents Beliefs about the Effect of Regular Coffee Scent (vs. No Scent) on Expectations about Performance on Cognitive Tasks via Expected Physiological Arousal Level (Study2) = 1.15, SE=.19 t =6.14, p < .01 Imagined Scent (Regular Coffee Scent=1,, No Scent = 0) Expected Physiological Arousal Level Total Effect: = .90, SE=.18 t = 4.96, p <.01 = .70, SE=.07 t = 10.62, p < .01 E Expectations about Performance P Direct Effect: = .10, SE=.15 t = .70, p =.49 Note: analysis was conducted with standardized variables. Fig. 2. Beliefs about the effect of regular coffee scent (vs. No scent) on expectations about performance on cognitive tasks via expected physiological arousal level (study 2). 86 A. Madzharov et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 57 (2018) 83e86 work by identifying coffee-like scent as a specific sensory trigger that can change behavior in a placebo-like manner. These findings support prior literature on olfaction that has established the importance of the sense of smell and the subtle but powerful influence that scents can have on perception and behavior (Krishna et al., 2010). For the first time, we identify coffee-like scent as one such influencer of analytical reasoning performance via expectations. Our findings are also informative for research on placebo effects by suggesting that smelling certain scents can have an effect similar to ingesting placebo substances. Placebo effects based on actual or believed caffeine ingestion have been demonstrated for physical performance tasks (e.g., Beedie & Foad, 2009). Here, we extend these findings by showing that merely smelling a caffeineassociated scent (without ingesting any caffeine) can boost performance on an analytical reasoning task. Additional research is needed to better understand people’s expectations regarding the specific effect of scents presumed to contain caffeine on arousal and cognition. For example, do people believe that smelling coffee scent would increase the length of time they could remain vigilant? What other types of mental performance enhancement would people expect to experience when smelling coffee scent? Here we operationalized people’s beliefs about coffee scent effects in a limited manner, using math problems from a standardized test. Future research could examine whether people also believe they could process verbal information more efficiently (e.g., comprehend advertisements seen in a shopping mall faster), or calculate market transactions more accurately (e.g., purchase totals, expected change). This research has several limitations. Study 1 was conducted among students and thus would benefit from replication with other types of participants in other situations. For example, a study in a more natural coffee-scented environment such as a coffee shop or a work place would provide a more realistic setting. Study 2, while helpful in terms of understanding the basis for people’s expectations regarding the effect of coffee scent on arousal and performance, was nevertheless conducted without the emission of actual scent. In conclusion, this research demonstrates that a coffee-like scent (vs. no scent) had a positive effect on performance on an analytical reasoning task, driven by people’s expectations. Given the prevalence and popularity of coffee-scented environments in people’ daily lives, the demonstrated effect has multiple practical implications and might suggest that people may benefit from being immersed in coffee-scented environments without the consumption of caffeine. In addition, our results also suggest that architects, building developers, and retail space managers should be cognizant of the potential impact of exposure to incidental ambient odors such as coffee scent, on people’s beliefs and behavioral patterns. Exposure to these and other types of odors might elicit unanticipated placebo effect type responses that designers may wish to mitigate via heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems. References Beedie, C. J., & Foad, A. J. (2009). The placebo effect in sports performance. Sports Medicine, 39(4), 313e329. Beedie, C. J., Stuart, E. M., Coleman, D. A., & Foad, A. J. (2006). Placebo effects of caffeine on cycling performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 38(12), 2159. Cheng, A. (2014, March 28). Uniqlo’s new partnerships with Starbucks, MoMa are signs of a new retail trend. Market Watch. August 5, 2016 http://blogs. marketwatch.com/behindthestorefront/2014/03/28/uniqlos-new-partnershipswith-starbucks-moma-are-signs-of-a-new-retail-trend/. , L., Poels, K., Janssens, W., & De Backer, C. (2013). Smelling the books: The Douce effect of chocolate scent on purchase-related behavior in a bookstore. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 65e69. €ther, S. J. L., & Giesbrecht, T. (2013). Caffeine as an attention enhancer: Eino Reviewing existing assumptions. Psychopharmacology, 225(2), 251e274. Geers, A. L., Kosbab, K., Helfer, S. G., Weiland, P. E., & Wellman, J. A. (2007). Further evidence for individual differences in placebo responding: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62(5), 563e570. Glade, M. J. (2010). Caffeinednot just a stimulant. Nutrition, 26(10), 932e938. guen, N. (2012). The sweet smell of… courtship: Effects of pleasant ambient Gue fragrance on women’s receptivity to a man’s courtship request. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(2), 123e125. Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2013). Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 2, 217e264. Ilyuk, V., & Block, L. (2015). The effects of single-serve packaging on consumption closure and judgments of product efficacy. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(6), 858e878. Krishna, A., Elder, R. S., & Caldara, C. (2010). Feminine to smell but masculine to touch? Multisensory congruence and its effect on the aesthetic experience. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(4), 410e418. Madzharov, A. V., Block, L. G., & Morrin, M. (2015). The cool scent of power: Effects of ambient scent on consumer preferences and choice behavior. Journal of Marketing, 79(1), 83e96. Morrin, M., & Ratneshwar, S. (2003). Does it make sense to use scents to enhance brand memory? Journal of Marketing Research, 40(1), 10e25. Oldenburg, R. (1989). The great good place: Cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community. New York: Marlowe & Co. Price, D. D., Finniss, D. G., & Benedetti, F. (2008). A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: Recent advances and current thought. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 565e590. Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovian conditioning: It’s not what you think it is. American Psychologist, 43(3), 151. Smith, A. (2002). Effects of caffeine on human behavior. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 40(9), 1243e1255. Vinitzky, G., & Mazursky, D. (2011). The effects of cognitive thinking style and ambient scent on online consumer approach behavior, experience approach behavior, and search motivation. Psychology and Marketing, 28(5), 496e519. Walton, A. G. (2012, May 29). Starbucks’ power over us is bigger than coffee: It’s personal. Forbes. August 5, 2016 https://www.forbes.com/sites/alicegwalton/ 2012/05/29/starbucks-hold-on-us-is-bigger-than-coffee-its-psychology/ #159961b34aed.