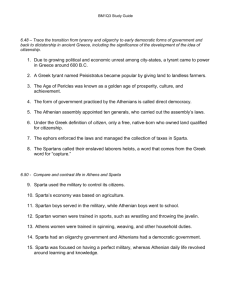

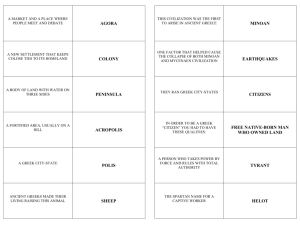

STUDENT NAME: Faustina Efua Ghartey STUDENT ID: 10880340 CAMPUS: City Campus COURSE CODE: LECTURER: THE SOCIO-POLITICAL NATURE OF ARCHAIC SPARTA 1.0 INTRODUCTION The term "archaic" refers to the time in ancient Greek history that preceded the classical period and is derived from the Greek word ´archaios´, which means "old." Essentially, the Greek Archaic Period lasted from the eighth century BCE until the Persian Wars in 490 BCE. It symbolises a pivotal point in the evolution of Greek civilization which ushered in the Classical era after the Dark Ages (Shapiro, 2007). In archaic Greece, Sparta was a well-known city-state in Laconia due to its acknowledgement by historians as the power-house of military strength and prowess around 650 BC (Cartledge, 2002). Sparta's peculiar socio-political structure set it apart from other ancient Greek city-states throughout the Archaic era, which roughly spanned the years between the eighth and late sixth centuries BCE. Due to its superior military might, Sparta was considered as the head of the combined Greek armed forces during the GrecoPersian Wars, competing with Athens' growing naval might. Because Spartans were highly militarised, their army's power and effectiveness was their top priority (Russel, 2015). A rigorous education and training programme supported by the state, the agoge was created to nurture disciplined and physically strong warriors. The following are some significant facets of ancient Sparta's socio-political structure: 2. 0. POLITICAL STRUCTURE OF ARCHAIC SPARTA Archaic Sparta had a distinct political structure that was frequently very unpleasant. It was an oligarchy, which means a tiny number of affluent people controlled it. The following are the main features of the oligarchic nature of Spartan political organisation: Diarchy (Dual Monarchy) The Spartan political structure was unique in that it had two monarchies. Two independent royal lineages called the Agiad and Eurypontid families produced two hereditary kings who ruled over Sparta. It was expected of these kings to cooperate and share authority (Cartledge, 2002). The monarchs' main responsibilities were military, judicial, and religious in nature. As the state's top priests, they communicated with the Delphian sanctuary, whose decisions had a significant political influence in Sparta. Their judicial responsibilities had been limited to instances involving inheritors, adoptions as well as roadways for the public by the time of Herodotus, who lived around 450 BC. The Spartan kingdom was described by Aristotle as "a form of unrestricted and everlasting generalship." As opposed to this, Socrates describes the Spartans as "subjected to an oligarchy at home, to kingship on a campaign." (Todd, 1911). The Council of Elders (Gerousia) The Gerousia, also known as the Council of Elders, was a crucial body in the Spartan government. In literary works, the group identified as the Spartan senate consisted of the two Spartan kings and twenty-eight individuals who were above sixty years old, referred to as gerontes´. Sparta's politics were influenced by the powerful Gerousia, a prestigious group with broad judicial and legislative authority (Cartledge, 2003). The mythological Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus is credited by the ancient Greeks with creating the Gerousia in his Great Rhetra, which is Sparta's constitution. Strange shouting elections were used to choose the gerontes, and these elections were susceptible to manipulation, particularly by the kings. The Gerousia members were chosen for life and had a great influence on decisions, especially when it came to laws (Forrest, 1968). The Administrators (Ephors) Five elected officials with considerable authority were known as the Ephors. They had the capacity to restrain the monarchs' power and were in charge of running the state on a daily basis. In archaic Sparta, the ephors were a council composed of five magistrates. They possessed a wide range of military, legal, judicial, and religious authority and could influence both domestic and international matters for Sparta (Xenophon, 1925). The Ephors were chosen yearly and had the authority to file accusations against the kings. Because of the significance of their authority and the sacred status they had acquired during their service, the ephors were revered by the people of Sparta and were exempt from having to kneel before the monarchs (Kagan, 1969). The Assembly (Apella) The Apella was a gathering where Spartan residents, often referred to as Spartiates or Homoioi, cast votes on significant matters. In contrast to other Greek city-states like Athens, the assembly's authority was, nevertheless, a bit restricted. The common assembly known as the Apella served as an advisory body in archaic Sparta and, in theory, symbolised the "democratic" aspect of the Spartan city-state, as claimed by historians from both the past and the present. Appella was very similar to what the Athenians called ´Ecclesia´ because they had similar roles and functions in the Spartan State. Similar to numerous other Spartan political establishments, the Apella's function within the Spartan political framework is outlined in the “Great Rhetra,” a collection of laws introduced by the renowned reformer Lycurgus (Plutarch, 2004). 3.0. THE SOCIAL STRUCTURE OF ARCHAIC SPARTA Throughout history, individuals have been divided into several social classes. In ancient Greece, social class was based on a number of variables, including citizenship, place of birth, income, and occupation. Greek city-states, or polis, had astonishingly diversified populations despite the fact that the male citizens had complete legal standing, the ability to cast a vote, assume public office, and possess property, dominated archaic Greek society. Although there were specific roles for women, children, labourers, slaves, and immigrants (both Greek and foreign), three social classes comprising the Spartans, perioeci, and helots in the Spartan archaic Greek hierarchy emerged. The Spartans Also known as Spartiates, they had the highest position in the ancient Greek social hierarchy at Sparta. All male citizens, even the free men, were compelled to undergo training and fight their entire lives because Sparta was only interested in war and combat (Powell, 2001). Children born to these mothers were supposed to follow in their fathers' footsteps and become Spartan soldiers . The Spartans did not engage in any manual labour in the city; their primary occupations were fighting and training for war. Men from Sparta stayed in the active reserve until they were sixty. Men were not allowed to remain with their families until they were 30 years old, when they were urged to marry at age 20. They referred to themselves as "homoioi" (equals), citing their shared way of life as well as the phalanx's discipline, which prohibited any soldier to be inferior to his fellows (Adcock, 1957). Labourers (Helots) The poorer classes of people, known as helots, were responsible for farming, labour, and other necessary occupations. It is a widely accepted historical fact that slaves made up a far smaller percentage of Archaic Greek society than labourers did (Kennel, 2010). These workers had no freedom at all and were entirely reliant on their boss. The Spartan helot class is the most wellknown example of Archaic Greece. These dependents frequently resided with their family and were not the property of any one citizen; unlike slaves, they could not be sold. They usually came to agreements with their employer, such as providing the farm owner a portion of their harvest and retaining the remainder for themselves. The quota that was necessary may have been large or inadequate, and the serfs may have received further advantages like safety and protection in numbers (West, 1999). Perioeci Although they shared comparable ancestry with the helots, the Perioeci held a very different role in Spartan culture. They were free and not bound by the same constraints as the helots, although not having full citizenship rights. Their precise role during the Spartans' rule is unclear, although it appears that they played a variety of roles, including talented artisans, foreign trade intermediaries, and provided a form of military reserve (Cartledge, 2002). As the Spartiate population declined, perioeci served with the Spartan army more and more, specifically at the Battle of Plataea. While they may have also performed tasks like manufacturing and repairing armour and weapons, they were gradually incorporated into the military units of the Spartan soldiers. They were Spartan dependents, residing in several dozen cities inside Spartan borders. The Spartan state belonged only to Spartan citizens whilst the perioeci just possessed political rights within their own city (Figueira, 1986). The Role of Women In comparison to other women in the archaic era, Spartan women belonged to the citizenship class and had a status, power, and respect unmatched by others. In Spartan society, women had a superior standing from birth; unlike in Athens, girls were fed the same food as their brothers. They were not like the Athenians in that they were not restricted to their father's home and couldn't go outside or exercise; instead, they went outside and participated in sports (Blundell, 1999). Uncommon in archaic times, Spartan women were educated and literate. Moreover, due to their education and their ability to interact openly with other male individuals in society, they were well-known for voicing their opinions even in public. Plato, writing in the middle decades of the 4th century, characterised the curriculum of women in Sparta as comprising gymnastics and music, and he commended the capacity of Spartan women for philosophical discourse (Pomeroy, 2002). "Wife-sharing" was another custom that numerous visitors to Sparta reported. Many older men permitted younger, fitter men to impregnate their wives, adhering to the Spartan concept that breeding should occur between the most physically fit parents. If a woman has a history of being a strong kid bearer, other single or childless men might even ask her to bear their children. Due to this, several individuals viewed Spartan women as polyandrous or polygamous (Blundell, 1999). 4.0. CONCLUSION: In summary, the unique institutions and priorities of archaic Sparta defined its socio-political makeup. Comprising of two dynastic monarchs, the Gerousia council of elders, and the influential Ephors, the dual monarchy established an intricate political structure. This philosophy placed a high value on military might and discipline, as demonstrated by the rigorous agoge training regimen required of Spartans. Though present, the assembly was not as powerful as other Greek city-states. The oppressed group known as helots was vital to the survival of the Spartan way of life. Overall, Sparta's socio-political structure demonstrated a society centred on upholding a strong military, and its distinctive elements—such as the dual monarchy and the helot system—set it apart from other ancient Greek societies. REFERENCES Adcock, F. E. (1957), The Greek and Macedonian Art of War. Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-00005-6 Blundell, S. (1999). Women in Ancient Greece. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-07141-2219-9. Cartledge, P. (2002). Sparta and Lakonia: A Regional History 1300 to 362 BC (2nd ed.). Oxford: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26276-3 Cartledge, P. (2003). The Spartans: An Epic History. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-1-44723720-4 Figueira, T. (1986). Population Patterns in Late Archaic and Classical Sparta. Transactions of the American Philological Association Vol. 116, pp. 165–213. Forrest, W. G. (1968), A History of Sparta, 950–192 B.C., New York: W. W. Norton & Co. Hall, J. M. (2007). "Polis, Community, and Ethnic Identity". In Shapiro, H.A. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kagan, D. (1969). The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. Page 29. Ithaca/New York 1969, ISBN 0-8014-9556-3. Kennell, N. M. (2010). "Helots and Perioeci" Sparta: A New History. Wiley-Blackwell pp. 136. Plutarch (2004). Frank Cole Babbitt (ed.), Moralia Vol. III, Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-99270-9r Powell, A. (2001), Athens and Sparta: Constructing Greek Political and Social History from 478 BC (2nd ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26280-1 Pomeroy, S.B. (2002). Spartan Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19513067-6 Russell, B. (2015). "The Influence of Sparta". History of western philosophy. Chapter XII: Routledge. ISBN 978-1138127043. OCLC 931802632 Shapiro, H.A. (2007). "Introduction". In Shapiro, H.A. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Todd, Marcus Niebuhr (1911). "Sparta". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 609–14. Xenophon. (1925). ´Constitution of the Lacedaemonians´. In E. C. Marchant, G. W. Bowersock, Constitution of the Athenians. Volumes 7. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann, Ltd., London. West, M. L. (1999). Greek Lyric Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19954039-6.