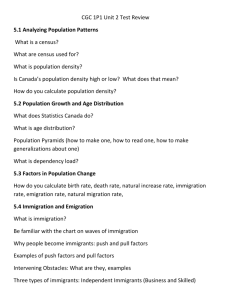

Unequal Relations: Race, Ethnicity, Aboriginal Dynamics in Canada

advertisement