The Book of Basketball The NBA According to The Sports Guy (Bill Simmons, Malcolm Gladwell) (Z-Library)

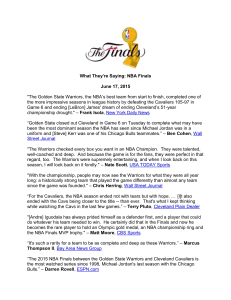

advertisement