Program Evaluation for Social Workers: Evidence-Based Programs

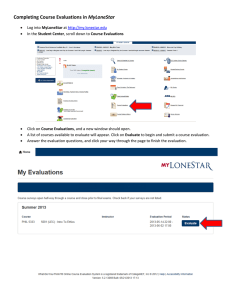

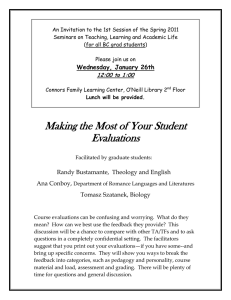

advertisement