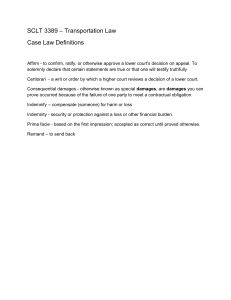

DISCUSS THE CONCEPT OF DAMAGES UNDER THE INDIAN CONTRACT ACT AND QUASI CONTRACTS SUBMITTED BY: UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF: ROLL NO- 61 MS. ANSHI AGARWAL SEMESTER – III ASST. PROF OF LAW, ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My sincere efforts have made me to accomplish the task of completing this project. However the completion of this task would not have been possible without the kind support of many individuals. I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my Asst. Prof. of Law, Ms. Anshi Agarwal, whose suggestions, guidance and moral support was a boon for my project. I would also like to thank my parents and friends for supporting me whole heartedly and providing me with everything I asked for. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to all those who have directly or indirectly guided me in this particular project. However as I have studied from various sources, anything missing incorrect due to oversight is deeply regretted. Thanking you. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Mode of Citation Research Methodology Table of Cases Introduction Body WHAT DOES LOSS OR DAMAGE MEAN? COMPENSATION FOR LOSS OR DAMAGE CAUSED BY THE BREACH OF CONTRACT COMPENSATION FOR FAILURE TO DISCHARGE OBLIGATIONS SIMILAR TO THOSE CREATED BY THE CONTRACT WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF DAMAGES? CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGE AND INCIDENTAL LOSS HOW TO MEASURE THE DAMAGE CAUSED? WHAT DOES THE REMOTENESS OF DAMAGES MEAN? HOW TO TEST THE REMOTENESS? QUASI-CONTRACTS ELEMENTS OF A QUASI-CONTRACT PRINCIPLE ON WHICH QUASI-CONTRACTS ARE BASED QUASI-CONTRACTUAL OBLIGATIONS DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CONTRACTS AND QUASI-CONTRACTS DAMAGES UNDER QUASI CONTRACTS 6. Conclusion 7. Bibliography MODE of citation: Uniform RESEARCH METHODOLOGY: Doctrinal method of research TABLE OF CASES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Mohori Bibee vs Dharmodas Ghose Balfour v. Balfour Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co v. New Garage and Motor Co. Ltd Hadley v Baxendale Bismi Abdullah v. Regional Manager, F.C.I., Trivandrum Hari Ram Sheth Khandsari v. Commissioner of Sales Tax Moses v. MacFarlane Exall v. Partridge Sales Tax Officer v. Kanhaiya Lal INTRODUCTION CONTRACT: A set of promises, may be oral or written in nature, which is legally enforceable is known as contract. It is a binding agreement between two or more parties. A contract includes variety of subjects such as exchange of goods, services, capital or promises of any of those. Contracts are part and parcel of our life. Contracts can be of various types depending on the terms and conditions. A contract creates mutual obligation on the contracting parties. In India, contracts are governed by the Indian Contract Act, 18721. DEFINITIONS OF CONTRACT: According to Pollock, “Every agreement and promise enforceable by law is a contract”. According to Salmond, “A contract is an agreement creating and defining obligation between two or more persons by which rights are acquired by one or more to act or forbearance on the part of others. According to Anson, The law of contract is that branch of law which determines the circumstances in which a promise shall be legally binding on the person making it”. According to Section 2(h) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, “An agreement enforceable by law is a contract”. According to Cambridge Dictionary, “Contract is a legal document that states and explains a formal agreement between two different people or groups, or the agreement itself”. LAW OF CONTRACT IN INDIA: In India, contracts are being governed by the British enacted legislation i.e. the Indian Contract Act, 1872. This act is based on the principle of English Common Law'. It deals efficiently with all the aspects of contract such as formation, enforcement etc.There are 11 Chapters and 266 sections however Sections 76 to 123 and 239 to 266 have been repealed. ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF CONTRACT: As per Section 10 of Indian Contract Act, 1872,”All agreements are contracts if they are made by the free consent of parties competent to contract for a lawful consideration and with a lawful object and are not hereby expressly declared to be void”. The essential elements of a valid contract are as followsoffer: An offer is also termed as proposal. An offer is a proposal by one person, whereby he expresses his willingness to enter into a contractual obligation in return for a promise, act or forbearance. As per Section 2 (a) of the Indian Contract Act, “when one person signifies to another his willingness to do or abstain from doing anything with a view to obtaining the assent of that other to such act or abstinence, 1 It extends to the whole of India and came into force on the first day of September. he is said to make a proposal or offer”. The person making the proposal/offer is called the proposer or offeror and the person to whom the proposal is made, is called the offeree. acceptance: A contract emerges from the acceptance of an offer. Acceptance is the act of assenting by the offeree to an offer. Under Section 2 (b) of the Contract Act, “When a person to whom the proposal is made, signifies his assent thereto, the proposal is said to be accepted”. mutual agreement: A situation is referred to as meeting of mind, when both the parties have recognised the contract and both give consent for entering into its obligations. lawful consideration: The term consideration' simply means something in return (quid pro quo). Any contract to be enforceable by law must have legal consideration. According to Section 2(d), consideration is defined, “When at the desire of the promisor, the promisee or other person has done or abstained from doing, or does, abstains from doing, or promises to do or abstain from doing something, such act or abstinence or promise is called consideration for the promise”. capacity of parties to contract: For a contract to be valid, the parties of a contract must have capacity, i.e. competence to enter into a contract. Every person is presumed to have capacity to contract but there is certain person whose age, condition of mental status renders them incapable of binding themselves by a contract. This incapacity must be proved by the party claiming the benefit of it. As per Section 11 of the Act, it deals with the competency of parties and provides that, “every person is competent to contract who is of the age of majority according to the law to which he is subject and who is of sound mind and is not disqualified from contracting by any law to which he is subject”. Mohori Bibee vs Dharmodas Ghose2 Date of Judgment: 4 March 1903 Court: Judicial Committee of the Privy Council Appealed from: High Court of Judicature at Fort William Appellant: Mohori Bibee Respondent: Dhurmodas Ghose Bench: 2 Lord McNaughton Lord Davey Lord Lindley Sir Ford North Sir Andrew Scoble Sir Andrew Wilson 1903 UKPC 12, (1903) LR 30 IA 114 Decision by: Sir Ford North Referred Sections of the Indian Contract Act, 1872: Section 38 Section 41 Section 68 Facts of Mohori Bibee vs Dharmodas Ghose Case: In Mohori Bibee vs Dharmodas Ghose, Dharmodas Ghose was a young person under 18 years old, which means he couldn’t legally make contracts. He owned some land and his mother was in charge of it legally. He used his land as collateral for a loan from Brahmo Dutta, agreeing to pay Rs.20,000 with a 20% interest rate every year. At the time, Brahmo Dutta was a money lender and Kedar Nath managed his business on his behalf. Kedar Nath acted as Brahmo Dutta’s representative. Dharmodas Ghose’s mother informed Brahmo Dutta that her son was a minor and couldn’t make contracts regarding his land. Kedar Nath, acting on behalf of Brahmo Dutta, knew about Dharmodas Ghose’s age and incapacity to enter such contracts. On September 10th, 1895, Dharmodas Ghose and his mother filed a lawsuit against Brahmo Dutta, claiming that Dharmodas had been a minor when he made the mortgage, rendering it invalid and improper. They wanted the contract to be cancelled. During the legal proceedings, Brahmo Dutta had passed away, so his representatives took over the case.The plaintiffs argued that the contract should be cancelled because the defendant, Dharmodas Ghose, had been deceitful about his age when he made the mortgage request. Mohori Bibee is the person appealing the case, but she’s the representative of Brahmo Dutta who had passed away. Issue Raised: The legal questions raised in Mohori Bibee vs Dharmodas Ghose were: Whether the deed was void under Section 2, 10(5), 11(6) of the Contract Act or not? Whether the mortgage initiated by the defendant was voidable or not? Whether the defendant was obligated to return the loan amount he had received under the deed or mortgage or not? Judgement in Mohori Bibee vs Dharmodas Ghose: After carefully examining the facts of the case, the Privy Council ruled that the agreement made with a minor is void ab initio, which means it is void from the very beginning. The court also addressed the defendant’s arguments. Firstly, the court in Mohori Bibee vs Dharmodas Ghose determined that the law of estoppel would not apply in this case since Brahmo Dutta’s attorney had knowledge of Dharmodas’s minority status.Secondly, the court clarified that Section 64 and 65 of the Indian Contract Act would not apply because there was no valid agreement in the first place and for these sections to be applicable, the contract must be between competent parties. As a result, the court in Mohori Bibee vs Dharmodas Ghose established a precedent that agreements with minors are void ab initio based on this case. free consent of the parties: According to Section 14 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, “Consent is said to be fee when it is not caused by- 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. coercion, undue influence fraud misrepresentation mistake” intent to create a legal relationship: Promise in the case of social engagements is generally without an intention to create a legal relationship. Such an agreement, therefore, cannot be considered to be a contract. Thus an agreement to go for a walk, a movie to play some game etc cannot be enforced in a court of law. Balfour v. Balfour3 Facts: The Plaintiff and the Defendant were a married couple. The Defendant husband and the Plaintiff wife lived in Ceylon where the Defendant worked. In 1915, while the Defendant was on leave, the couple returned to England. When it was time to return to Ceylon, the Plaintiff was advised not to return because of her health. Prior to the Defendant returning, he promised to send the Plaintiff £30 per month as support. The parties’ relationship deteriorated and the parties began living apart. The Plaintiff brings suit to enforce the Defendant’s promise to pay her £30 per month. The lower court found the parties’ agreement constituted a contract. Issue: Does the husbands promise to pay £30 per month constitute a valid contract which can be sued upon? Held: The court first recognized that certain forms of agreements do not reach the status of a contract. An agreement between a husband and wife is often times such a form of agreement. In such agreements, one party is give a certain sum of money on a daily, weekly, monthly, etc.. basis. This agreement is sometimes termed an allowance. However, these agreements are not contracts because the “parties did not intend that they should be attended by legal consequences.” One reason the court is hesitant to treat these agreements as contracts, is that there would not be enough courts to handle the volume of cases. Thus, here, the husband’s promise did not rise to the level of a contract. As discussed, Balfour v. Balfour case made it very clear that the legal intention to enter into a contract is very necessary. 3 1919 2KB 571 BODY WHAT DOES LOSS OR DAMAGE MEAN? The word loss or damage means: Harm to persons through physical injury, disabilities, loss of enjoyment, loss of comfort, inconvenience or disappointment, injured feelings, vexation, mental distress, loss of reputation. Harm to property, viz. damage or destruction of property; and Injury to an economic position which is the amount by which the plaintiff is worse off than he would have been performed, and would include loss of profits, expenses incurred, costs, damages paid to third parties, etc. According to the Indian Contract Act, 1872, COMPENSATION FOR LOSS OR DAMAGE CAUSED BY THE BREACH OF CONTRACT: When a contract has been broken, the party who suffers from such infringement is entitled to receive compensation for any loss or damage resulting from such infringement. Such compensation shall not be given for any remote and indirect loss or damage sustained as a result of the breach. COMPENSATION FOR FAILURE TO DISCHARGE OBLIGATIONS SIMILAR TO THOSE CREATED BY THE CONTRACT: If an obligation similar to what was created in the contract has not been discharged, any person who fails to discharge is entitled to receive the same compensation from the party in default as if that person had contracted to discharge it and had broken his contract. Explanation: In estimating the loss or damage resulting from the breach of a contract, consideration must be given to the means that existed to remedy the inconvenience caused by the non-performance of the contract. WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF DAMAGES? 1. General and Special Damages: General Damages Special Damages General damages refer to those damages which arose naturally during the normal course of the events. Special damages are those that do not, of course, arise from the breach of the defendant and can only be recovered if they were in the reasonable consideration of the parties at the time they made the contract. In relation to the pleadings, the complained of is presumed to be a natural and probable consequence with the result that the It refers to those losses that must be specifically pleaded and proven. In relation to proof, it refers to those losses, It refers to those losses that can be calculated financially. It usually but not exclusively non-pecuniary, which in monetary terms are not capable of precise quantification. represents the exact amount of pecuniary loss that the claimant proves to have suffered from the set of pleaded facts. 2. Nominal Damages: Nominal damages are awarded if there is an infringement of a legal right and if it does not give the rise to any real damages, it gives the right to a verdict because of the infringement. In the following circumstances, nominal damages are awarded to the plaintiff: The defendant committed a technical breach and the plaintiff himself did not intend to execute the contract; The complainant fails to prove the loss he may have suffered as a result of the contract breach; He has suffered actual damage, not because of the defendant’s wrongful act, but because of the complainants’ own conduct or from an outside event; The complainant may seek to establish the infringement of his legal rights without being concerned about the actual loss. Where there is no basis for determining the amount. The view that nominal damage does not connote a trifling amount is erroneous; nominal damage means a small sum of money. Nominal damages have been defined as a sum of money that can be spoken of, but which does not exist in terms of quantity. Holt C.J. in Balfour v. Balfour, observed: Every injury imports a damage though it does not cost the party one farthing. Taking support from the above famous dictim4 of Holt, C.J., The High Court said that nominal damages might be awarded where the fact of the loss was shown but the necessary evidence as to its amount was not given. 3. Substantial Damages: In cases where an offense is proven, many authorities may claim substantial damages even if it is not only difficult but also impossible to calculate the damages with certainty or accuracy. In all these cases, however, the extent of the breach has been established. There was a complete failure to perform the contract on one side. However, where the breach is partial and the extent of the failure is determined, only nominal damage is awarded. The plaintiff who can not show that after the breach he would have had the contract performed, he is in a worse financial position, usually, recover only nominal damages for breach of contract. Where a defendant refuses to accept goods sold or manufactured for him, the plaintiff sells them to a third party on the same terms as the defendant agreed and makes a similar profit, the plaintiff shall be entitled to nominal damages if the demand exceeds the 4 Any statement or opinion made by the judge that is not required as part of the legal reasoning to make a judgement in a case. supply of similar goods; but if the supply exceeds the demand, the plaintiff shall be entitled to recover his loss of profit on the defendant’s contract. 4. Aggravated and Exemplary Damages: Aggravated Damages Aggravated damages, that compensate a victim for mental distress or injured sensations in circumstances where the injury was caused or increased by the manner in which the defendant committed the wrong or the defendant’s behavior following the wrong. Exemplary Damages Exemplary damages are intended to give the punishment to the defendant an example they are punitive and not intended to compensate the defendant for loss, but rather to punish the defendant. It is compensatory in nature. It is punitive in nature. 5. Liquidated and Unliquidated Damages: Damages are said to be liquidated once agreed and fixed by the parties. It is the sum agreed by the parties by contract as payable on the default of one of them, Section 74 applies to such damages. In all other cases, the court quantifies or assesses the damage or loss; such damages are unliquidated. The parties may only fix an amount as liquidated damages for specific types of a breach, then the party suffering from another type breach may sue for unliquidated damages resulting from such breach. Where, under the terms of the contract, the purchaser was entitled to claim damages at the agreed rate if the goods were not delivered before the fixed date and if they were not delivered within seven days of the fixed date, the purchaser was entitled to cancel the contract and pay guarantee amount to the bank, but the goods were delivered within the extended period. It was held that the buyer was only entitled to claim damages at the agreed rate and that the banking guarantee confiscation clause could not be invoked as the contract was not cancelled. In Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co v. New Garage and Motor Co. Ltd5, the plaintiffs, Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co, who were the manufacturers of motor car tyres and tubes etc sold some of these goods to the defendants. The defendants agreed not to sell those goods further below the manufacturere’s list price. They also agreed to pay 5 pounds by way of liquidated damages for every tyre, tube etc sold below the list price. It was held by the House of Lords that the sum of compensation payable on the bgeach of the agreement was the genuine pre-estimate of damages and therefore liquidated damages. CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGE AND INCIDENTAL LOSS: Consequential damage or loss usually refers to pecuniary loss resulting from physical damage, such as loss of profit sustained due to fire damage in a factory. When used in the exemption clause in a contract, consequential damages refer to damages that can only be recovered under the second head in Hadley v Baxendale, i.e. the second branch of the section, and may also include recovery of profit and losses under the first branch. Another term incidental loss refers to the loss incurred by the complainant after he became aware of the breach and made to avoid the loss, i.e. the cost of buying or hitting a replacement or returning defective goods. HOW TO MEASURE THE DAMAGE CAUSED? The measure of damage or measure of damages is concerned with the legal principles governing recoverability; the principle of the remoteness of damage 5 1915 AC 79 confines the recoverability of damages. Questions of quantum of damages are only concerned with the amount of damages to be awarded and are, therefore, different from the measure of damages; the latter involves consideration of the law. In Bismi Abdullah v. Regional Manager, F.C.I., Trivandrum6, the defendant having agreed to purchase rice from the plaintiff failed to do so. The defendant resold the rice 4 ½ months after the breach of contract when the market had crashed. The plaintiff was held entitled to nominal damages only, which were considered to be equivalent to the security deposit of Rs. 1000 deposited by the defendant. WHAT DOES THE REMOTENESS OF DAMAGES MEAN? The term remoteness of damages refers to the legal test used to determine which type of loss caused by contract breach can be compensated by awarding damages. It has been distinguished from the term measure of damages or quantification which refers to the method of assessing the money the compensation for a particular consequence or loss which has been held to be not too remote. HOW TO TEST THE REMOTENESS? In deciding whether the claimed damages are too remote, the test is whether the damage is such that it must have been considered by the parties as a possible result of the breach. If it is, then it can not be considered too remote. The damage shall be assessed on the basis of the natural and probable consequences of the breach. Actual knowledge must be demonstrated that mere impudence and carelessness is not knowledge. The defendant is only liable for reasonably foreseeable losses- those who would have reason to foresee the likelihood of future infringement if a normally prudent person in his place had this information when contracting. The remoteness of damage is a matter of fact, and the only guidance that the law can give is to lay down general principles. Whether the breaching party is liable to compensate for all the losses, both direct and indirect, that the non-breaching party has suffered due to the breach of the contract? Are remote losses liable to be compensated? The most important case law which addresses these questions is the English case of Hadley v. Baxendale7. The case was decided in the Court of Exchequer by a bench led by Judge Sir Edward Hall Alderson. The principle laid down in the judgement finds expression in the contract laws of most common law countries, including the Indian Contract Act, 1872. The facts of the English case of Hadley v. Baxendale: involves a contract for carriage of a broken component of a mill. Hadley along with his partners were the proprietors of the City Steam Mills in Gloucester. The mill was involved in the cleaning and processing of food grains into flour and bran using steam power. On one of the days of operation of the mill, the crankshaft running the steam engine broke and production of the mill came to a halt. The proprietors of the mill contacted the engineering firm W. Joyce & Co., based in Greenwich, to manufacture a new crankshaft. The manufacturers sought the broken crankshaft to be sent to them as a reference for the new component. Hadley, through his agent, contacted Baxendale, who was operating the common carrier Pickford & Co. Both the parties agreed on a price for the shipping of the broken crankshaft and a deadline for the delivery was also agreed upon. Hadley did mention that it is extremely vital that the delivery is made within the deadline. But the shipment was re-routed through London where the broken crankshaft was held in storage so that it can be despatched along with other items which were also to be shipped to Greenwich. The 6 AIR 1987 Ker 56 7 (1953) Ch. 770, at p. 780; (1953) 2 All ER 810 at p. 815 shipment reached the manufacturer several days after the deadline. All the while the mill at Gloucester remained shut down. Hadley suffered a severe loss due to the non-operation of the mill. Aggrieved by his loss Hadley sued Baxendale for damages to compensate for the losses he has suffered due to the non-operation of the mill and possible loss of goodwill and customers. Rule of Hadley v. Baxendale in Indian Contract Act, 1872: The rule of Hadley v. Baxendale is incorporated in the first proviso of Section 73 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872. The Section, in full, states that: “73. Compensation for loss or damage caused by breach of Contract– When a contract has been broken, the party who suffers by such breach is entitled to receive, from the party who has broken the contract, compensation for any loss or damage caused to him thereby, which naturally arose in the usual course of things from such breach, or which the parties knew, when they made the contract, to be likely to result from the breach of it. Such compensation is not to be given for any remote and indirect loss or damage sustained by reason of the breach. Compensation for failure to discharge obligation resembling those created by contract- When an obligation resembling those created by contract has been incurred and has not been discharged, any person injured by the failure to discharge it is entitled to receive the same compensation from the party in default, as if the person had contracted to discharge it and had broken his contract. Explanation- In estimating the loss or damage arising from a breach of contract, the means which existed to remedy the inconvenience caused by the non-performance of the contract must be taken into account.” The rule as embedded in Section 73 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 had been used to decide several seminal cases by the Indian Judiciary. QUASI-CONTRACTS The word ‘quasi’ means pseudo or partly or almost and that is why it can also be called a pseudo contract. A quasi-contract is an agreement that is retroactive in nature. These kinds of agreements take place between parties who have no prior contractual commitments or intention of getting into a contract. The judge simply develops the concept of a quasi-contract to rectify situations where one side acquires something at the detriment of the other side. In layman’s language, this type of contract aims to prevent one party from benefiting financially in a situation while financially draining the other party. Such agreements may be enforced by the approval of the party which is responsible for providing the goods or services but it is not necessary to keep this factor in mind before enforcing a quasicontract. The only factor that constitutes a quasi-contract is that there lacks an understanding between parties beforehand. Quasi-contracts exaggerate one party’s duties to the other party where the second party is in control of the first party’s personal property. As a remedy, it is the judge’s duty to impose the agreement by the law. To support this statement, the author would like to give an example: in a hypothetical situation, Party A found a wallet on the road which belongs to Party B. By this example shows that Party A owes something to Party B as they now possess Party B’s property indirectly or by mistake. The contract becomes enforceable only if Party A decided to keep Party B’s wallet without trying to return it to the original owner. A second word for quasi-contracts is implied contracts. A literal meaning is attached to the term implied contract as the defendants are ordered to pay for the damages and the quantum meruit or restitution is measured as per the intensity of the wrong done. Lastly, none of the parties involved are supposed to give consent as the agreement is being established in the court, therefore, making it legally enforceable without consent. The main aim of such contracts is to make a fair decision that will, later on, turn into an outcome that is acceptable to the party that has been wronged. ELEMENTS OF A QUASI-CONTRACT: Listed below are the components required for a judge to issue a quasi-contract: An individual or as the law recognizes, one claimant. There must also be a defendant who will be responsible and asked to pay the restitution. The defendant must be willing to recognize or even acknowledge the value of the product/ service in question but has not made any efforts to return it/ pay for it or even made an effort to do something about it. The complainant needs to prove that the defendant earned wrongful enrichment. PRINCIPLE ON WHICH QUASI-CONTRACTS ARE BASED: The main principles on which these types of contracts work are justice, equity, and good conscience. This principle is based on a legal maxim ‘Nemo Debet Locupletari Ex Aliena Jactura’8. To support this statement, here is an illustration of this principle: In a situation, Pari and Isha enter into a contract where Pari agrees to pay 900 rupees for a bouquet of flowers when it would be delivered to her house by Isha herself. However, Pari mistakenly delivers the bouquet to Anisha’s house and she issues it as a birthday gift and she keeps it for herself. Even though there is no contract between Anisha and Pari, the court shall treat this situation as a quasi-contract and order Anisha to either pay for the flower bouquet or return it in the same condition. Law sees no contract between the parties, it is just that the law imposes contractual liabilities in order to not oversee certain peculiar situations. There are 5 different types of situations where a quasi-contract can be formulated. All these situations are elaborately discussed under Section 68 to Section 72 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872. In the case of Hari Ram Sheth Khandsari v. Commissioner of Sales Tax9 , the applicant of this case deposited the tax as a major turnover of Khandsari and it was initially taxable at the rate of 2 percent. Because of a mistake, in the fourth quarter, the applicant deposited the tax at the rate of 4 percent which means a total of Rs. 10,198.22 of excess money was deposited. The concept of quasi-contract has been discussed even though the definite term was not used in this case law. For the very first time, the concept of quasi-contracts was introduced and discussed in the case of Moses v. MacFarlane10. This was an English case and in this case, the ruler of Mansfield stated that the commitment of such sorts or in simpler words the obligation underlying quasi contracts was based on 8 No man must grow rich out of another persons’ loss. 9 2005 139 STC 358 All 10 1760, 97 Eng. Rep. 676 (2 Burr. 1005) the law as well as the justice with anticipation of not giving out undue advantage to one person that might cost another person. QUASI-CONTRACTUAL OBLIGATIONS 1. Section 68: “Necessaries supplied to a person incapable of contracting”: Necessities supplied to the person who is incapable of contracting is the first example of the situation under which a quasi-contract can be formulated and this situation is explained under Section 68 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872. To understand this easily, any person who is incapable of entering into a contract i.e. is a lunatic, minor, mentally incapable of understanding their surroundings, etc. If someone even supplies necessary supplies to such a person even is entitled to get a reimbursement from the property of the person who is incapable in this situation. This rule is applicable whether or not the person does help the incapable person because of an ulterior motive or purely out of humanity. 2. Section 69: “Payment by an interested person”: Payment by an interested person is the second situation under which a quasi-contract can be formulated and this situation is explained under Section 69 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872. To understand this type of quasi-contract, the main thing to keep in mind is that if a person pays the money on someone else’s behalf, the other person is bound to pay back the money and reimburse the person by law. In Exall v. Partridge11, the plaintiff placed his carriage in the defendants premises. Since it was lying in the defendants premises, his landlord seized it as distress because the defendant was in arrears of rent. The plaintiff had to clear the arrears of rent which were otherwise to be paid by the defendant and got his carriage back. It was held that the plaintiff was entitled to recover from the defendant the rent paid by him. 3. Section 70: “Obligation of the person enjoying the benefits of a non-gratuitous act”: When a person enjoys the benefits of a non-gratuitous act, that person is obligated to repay the person wronged. As per Section 70 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 it is stated that if a person is legally giving out goods/ products/ services with no intentions behind it of performing a non-gratuitous act for anyone and the person in the wrong graciously uses the goods/ products or services is liable to pay the compensation to the former for the benefits they have been getting from the latter. They may be liable to give back monetary compensation or maybe simply asked to restore the goods used. To get reimbursed, the plaintiff must prove that the services/ goods they delivered were lawful, there was no intention to provide those products/ services graciously, and that the latter did enjoy the benefits of the products/ services. 4. Section 71: “Responsibility of finder of goods”: As per Section 71 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, if a person finds an item that belongs to someone else and decides to take them into their custody, the former person has to adhere to the responsibilities that include taking good care of the goods, not appropriating the goods and returning it back to the owner in the same condition they found it in. 5. Section 72: “Money paid by mistake or under coercion”: As per Section 72 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, if a person finds that they received money from someone by mistake or 11 (1799) 8 Term R. 308 because of the fact that they were under coercion then the former is liable to repay or return the money they received in the due course. Section 72 is based upon the principle of equitable restitution. A person is under a mistake that money is due when, in fact, it is not due. Such a person when he pays under mistake must be repaid. Money paid under mistake is recoverable whether the mistake be of fact or of law. In the case of Sales Tax Officer v. Kanhaiya Lal12. The Supreme Court held that section 72 of the Indian Contract Act is wide enough to cover not only a mistake of fact but also a mistake of law. In this case, the levy of sales tax on forward transactions was held to be ultra vires by the . Allahabad High Court. The respondent, therefore, claimed a refund of the tax paid under mistake of law under section 72. It was held that the respondent was entitled to the refund. DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CONTRACTS AND QUASI-CONTRACTS: A quasi-contract is a fictitious contract that has been pointed out by law. It is considered a valuable suggestion by law as it is a cure for the distress of the wronged party which isn’t the case in express contracts. While talking about quasicontracts, the purpose of the parties is not taken under consideration but it is totally opposite when we talk about express contracts as discussing the purpose here is a vital process. Without understanding the intention of the parties, there would be no contract at all. In the case of a quasi-contract, the entire concept of the contract revolves around the obligation of the parties as they are used to identify and shape the terms and conditions of the contract. On the other hand, the obligations formed are characterized because of the formation of the contract. DAMAGES UNDER QUASI CONTRACTS: In case of breach of a quasi contract, section 73 of the Indian Contract Act provides for the same remedies (claim for damages) as provided in case of breach of a contract. It reads: When an obligation resembling those created by contract has been incurred and has not been discharged, any person injured by the failure to discharge it is entitled to receive the same compensation from the party in default, as if such person has contracted to discharge it and has broken his contract. Because a quasi contract is not a true contract, mutual assent is not necessary, and a court may impose an obligation without regard to the intent of the parties. When a party sues for damages under a quasi-contract, the remedy is typically restitution or recovery under a theory of quantum meruit13. Liability is determined on a case by case basis. 12 13 1959 AIR 135, 1959 SCR Sulp. (1)1350 When the injured party has performed a part of his obligation under the contract before the breach of contract has occurred, he is entitled to recover the value of what he has done, under this remedy. CONCLUSION Though there are other remedies available to parties aggrieved by breach of contract like rescission of contract, sue for specific performance, injunction and quantum meruit, damages especially liquidated ones are considered far better option than the enlisted remedies due to the easy nature of their computation, thereby leading to prevention of litigation or at least fast outcome of litigation. For fixation of liability in order to claim damages, there has to be establishment of causation, that is, to establish a causal connection between the loss incurred/ injury sustained and the breach committed. Such an establishment of causation will not solely make a defendant liable if the loss or injury is too remote to the breach of contract. In cases where there is contributory negligence on the part of plaintiff himself, the court may disentitle him from claiming damages. Thus, the maxim of “He hath committed inequity shall not have equity” may be applied by courts. A quasi-contract is not a contract in its natural context and therefore it is also named an inverted contract. This is the reason why the term quasi-contract is not stated out there expressively. The most simple principle it follows is that a quasi-contract is a simple and basic contract that will not and cannot supersede the requirement of justice. BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS REFERRED: 1. The Indian Contract Act, 1872 2. Contract-I by Dr. R.K. Bangia WEBSITES REFERRED: https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-4749-law-of-contract.html#google_vignette https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-4531-balfour-vs-balfour-case-analysis-1919-2kb571.html https://www.casebriefs.com/blog/law/contracts/contracts-keyed-to-calamari/the-agreementprocess/balfour-v-balfour/ https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-232-case-analysis-mohori-bibee-v-s-dharmodasghose.html https://blog.ipleaders.in/damages-for-breach-of-contract-under-indian-contract-act-and-englishcontract-law/ https://blog.ipleaders.in/types-damages-section-73-indian-contract-act-1872/ https://www.casebriefs.com/blog/law/contracts/contracts-keyed-to-farnsworth/remedies-forbreach/hadley-v-baxendale/ https://blog.ipleaders.in/all-about-quasi-contracts-and-types/ https://egyankosh.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/13374/1/Unit-8.pdf https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=cases%20on%20quasi%20contract https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/quasi_contract_(or_quasicontract)#:~:text=Because%20a%20quasi%20contract%20is,a%20theory%20of%20quantum%20meruit. https://blog.ipleaders.in/limiting-damages-promoting-contracting-rule-hadley-v-baxendale-englishcontract-law/