Mechanics Design: Standardization & Knowledge Decentralization

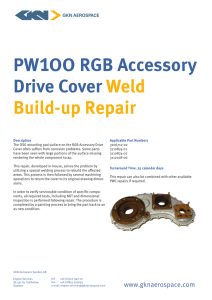

advertisement

The future of mechanics: design as a means of standardisation and knowledge decentralisation Abstract Failure and downtime of heavy logging equipment can be costly in terms of time and money for a productivity-oriented industry such as forestry, and the equipment repairer is responsible for such a role. However, due to the complexity and sophistication of logging equipment, there is a high barrier to entry and communication costs to become a mechanic, and there is a lack of a standardised solution for training and on field repairs. As interaction designers, with the prospect and concern about the career prospects of maintenance mechanics, we started a dialogue with maintenance mechanics to understand their different career development and the real problems they encountered in their work and designed a platform for maintenance workers that focuses on visual guidance and resource integration. By describing the specific design process of the platform, this paper explores the opportunities and challenges posed by industry standardization and open-sourcing of knowledge, as well as where the boundaries are for digitalization to be able to intervene in work that is strongly dependent on reality. Keywords. Knowledge democracy, Standardization, Resource Integration, Design practice, Forestry Context Forestry plays an extremely important role in Sweden's national economic and social development. Forestry products are one of Sweden's main export commodities, and products such as wood and pulp contribute significantly to Sweden's trade revenue. Timber products are exported all over the world, bringing Sweden significant foreign exchange earnings. The forest industry not only directly employs logging and wood processing positions, but also indirectly supports the whole chain, such as wood processing, transport, research and development, which provides work for many people. Heavy logging equipment dominates almost the entire forest industry with its many stakeholders. Heavy equipment producers play a very important part in the core chain of interests of the whole industry. They are not only the suppliers of the implements but also responsible for the repair and maintenance of the implements, as well as the basic training of the operators. Among them, the maintenance of the instruments, as an after-sales treatment, is the most important part of the company's after-sales service mechanism, which is directly linked to the pecuniary interests of the users. Although the company can minimize the probability of machine breakdowns through some service strategies, such as regular maintenance and inspection of the machines, the maintenance itself will bring considerable time costs. This is why the repair process is particularly important for the customer, who is suffering a huge loss in terms of money stacked on top of it every second the machine is out of action. The repairer is responsible for minimising this loss, and the quicker he or she can find the problem, the shorter the machine downtime will be. But the existing training of repairers is not a standardised product. When a recruit enters the workshop, he or she first spends about six months with a senior technician, observing how they diagnose and repair machines. The first 6 months are designed to help them familiarise themselves with the parts of the machine as a first step. Thereafter, they will receive more systematic training to understand each part of the machinery and start to try to take over some repair projects independently on their own. When they encounter a problem that they cannot solve, they usually choose to call a more experienced senior technician for help. Even though all the knowledge they need is stored on the company's platform, they rarely choose to sit down at the computer and slowly work out exactly what kind of problem they need to solve, because the accessibility and visualisation of the information are so low. The repairer's career is so hands-on. Research In this project, we worked with Komatsu, a local company in Umeå, and visited their factory, workshop, and maintenance team in the forest, and observed a lot of phenomena worth exploring. Although I mentioned in the previous article that the junior technicians receive a period of systematic training when they first enter the workshop, in specific conversations with the technicians we learnt that they don't have a complete set of career development programmes and paths. Most of the time they need to be very autonomous, asking questions of more experienced technicians and deciding for themselves which parts of the machine they want to delve into. Even though maintenance is a very hands-on job, technicians still need to switch between different platforms to get the information they want. In a maintenance task, for example, they need to get specific information about the time and place of the task and the machine's operating hours, which are stored on different platforms, so switching between different digital platforms is extremely important for them. Analysis WHAT I NEED (comments on these topics below) I find it hard to structure all the information we get from Komatsu since they are really parelleled. Therefore I got stuck when trying to look into all the valuable details. And since we have to minimise our paper in 4 pages, its difficult to balance the depth I want to go into and the width of information. If I analysis every detail too much, it will be really a long paper. How to write not like I’m presenting the final design work and give just some valuable insights? It's hard not to think about the structure of an entire article in a results-oriented way.