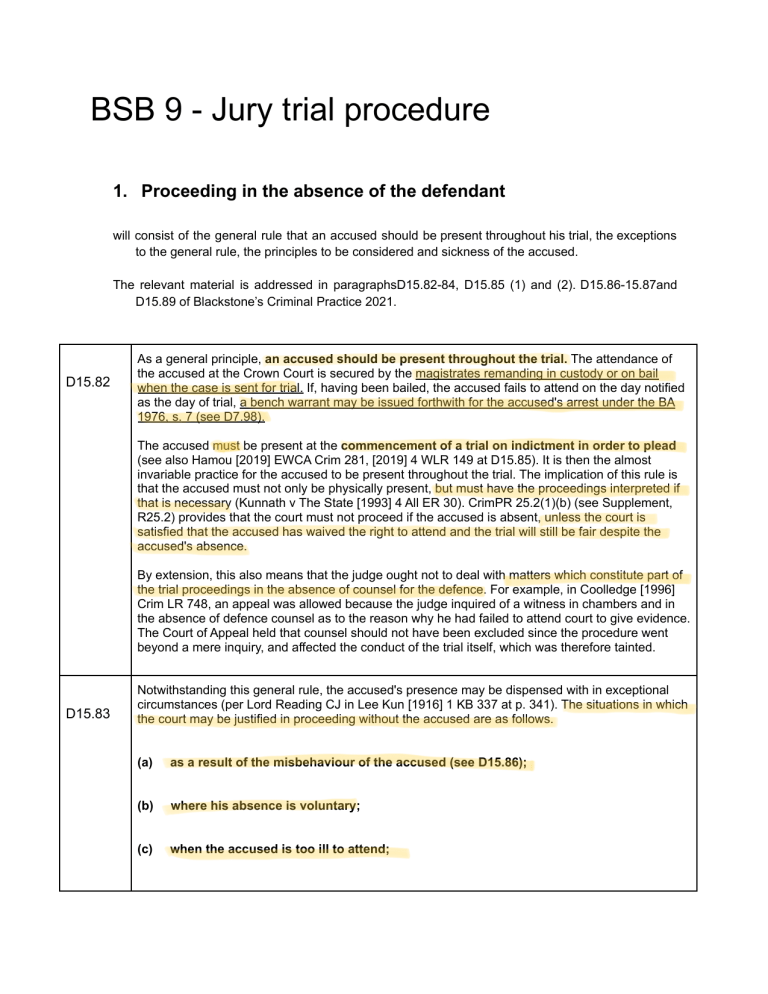

Jury Trial Procedure: Defendant Absence

advertisement