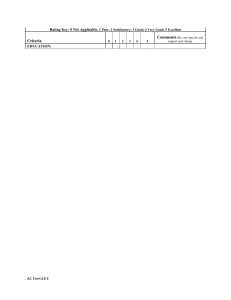

International Journal of Project Management 19 (2001) 139±145 www.elsevier.com/locate/ijproman The risk ranking of projects: a methodology David Baccarini a,*, Richard Archer b a School of Architecture, Construction and Planning, Curtin University of Technology, PO Box U1987, Perth, WA 6845, Australia b Department of Contract and Management Services, Perth, WA, Australia Received 11 January 1999; received in revised form 12 October 1999; accepted 21 October 1999 Abstract Project risk management literature commonly describes the need to rank and prioritise risks in a project in order to focus the risk management eort on the higher risks. This approach can also be applied to the risk ranking of projects. This paper describes the use of a methodology for the risk ranking of projects undertaken by the Department of Contract and Management Services (CAMS) Ð a government agency in Western Australia (WA). # 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd and IPMA. All rights reserved. Keywords: Project risk management; Risk analysis; Risk ranking 1. CAMS: introduction The Department of Contract and Management Services (CAMS) is the agency that provides contracting services to Western Australian Government agencies. The mission of CAMS is ``to enable Western Australian public sector agencies and the private sector to gain access to expert contract and management services for government business'' [1]. A key role of CAMS is to manage contracts and procurement risks. The scope of projects dealt by CAMS in 1996/97 included the management of a capital works program of $A221m and a building maintenance program of $A94m; and calling 224 contracts for goods and services on behalf of agencies with a contract value of $A123m [2]. 2. CAMS and risk management: historical context The risk management process created by CAMS and described herein is consistent with recommendations made in various Western Australian Government reports. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, public con®dence in many Australian institutions had been severely eroded. There had been an increase in allegations of mismanagement, incompetence, improper behaviour, corporate fraud and public corruption. The * Corresponding author. Tel.: +61-9-351-2712; fax: +61-9-3512711. credibility of the public sector and its services, and much of the private sector, was at risk [3]. In June 1993, the WA Government published its ``Report of the Independent Commission to Review Public Sector Finances Ð Agenda for Reform'', known as the ``McCarrey Report'' [4]. This observed that ``there appear to be few internal control processes which embrace the perspective of risk management in ensuring objectives are achieved'' (p. 159). Consequently, it recommended that formal risk assessment be introduced into the WA public sector. In 1994, the Auditor General issued its First General Report that contained a wide range of comments on public sector risk management [5]. It recommended that the McCarrey recommendation to implement internal controls be urgently implemented. Furthermore, it recommended that government agencies assess risks associated with their activities and initiate risk management approaches to minimise identi®ed risks. Finally, Treasurer's Instruction 109 gazetted in July 1997 stated that public sector agencies should ensure that risk management policies, practices and procedures are in place [6]. 3. Risk analysis It is commonly submitted in the risk management literature that part of the project risk management process requires the analysis of identi®ed risks in terms of their 0263-7863/01/$20.00 # 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd and IPMA. All rights reserved. PII: S0263-7863(99)00074-5 140 D. Baccarini, R. Archer / International Journal of Project Management 19 (2001) 139±145 Fig. 1. Project risk rating: framework. Quality requirements have been agreed and are being documented Benchmarks were used to establish schedule Benchmarks were used to establish budgets The basis for the budget is clear, but indications are that overruns are possible The basis for the schedule is clear, but indications are that overruns are possible Quality requirements have been agreed but not yet documented There is no clear schedule or the schedule is clearly insucient Quality requirements are not known The way the TIME targets were established The way the QUALITY targets were established 5 Rating Factor . Procurement planning: Analysis and planning is carried out. Decisions are made regarding the method of procurement and the way in which the contract will be managed. . Contract development: Contract documents are put together and the contract established. . Contract management: Goods and services provided by the contractor in return for payment from the client. Table 1 Risk factors: method of establishing targets The Risk Rating process is the focus of this paper and is applied at the three major phases of the contracting process (Fig. 1): 4 1. Risk Rating: Decide how ``risky'' the project is. 2. Risk Management Planning: Work out what could go wrong, and decide how to manage the things that could go wrong. 3. Risk Monitoring: Continually review the risks and controls. The basis for the current budget is unclear or the budget is likely to be inadequate The basis for the current schedule is unclear or the schedule is likely to be inadequate Some initial discussions with the client on quality requirements 3 The previous section described the process for assessing and prioritising risks within one project. A similar approach can be adopted by organisations dealing with many projects to assess and prioritise projects using risk as a criterion. Most organisations have limited resources to manage all risks equally on all projects. To overcome this problem, the organisation can assess and prioritise the risk level of each project, so that an appropriate level of eort can be applied to the management of those projects. In particular, resources will be directed to manage projects with the higher risk ranking. This is the approach adopted by CAMS Ð ``The focus of risk management activities should be on those contracts that are assessed as high risk'' [1]. In 1997, CAMS introduced a three-step risk management process to be applied to all its contracting activities: Risk Rating, Risk Management Planning, Risk Monitoring: There is no clear budget or the budget is clearly insucient 2 4. Project risk ranking (PRR): introduction The way the COST targets were established 1 potential consequences and probability of occurrence [7,8]. This allows risks to be ranked for management priority. So, once project risk events and causes have been identi®ed, the next stage is to analyse and prioritise them to guide risk management action. This process is ``a vital link between systematic identi®cation of risks and rational management of the signi®cant ones'' [9]. Therefore, the aim of risk analysis is to determine which risk events warrant response [10]. As Grey (1995) points out, ``having identi®ed the risks in your project, you will usually have insucient time or resource to address them all; so the next requirement is to help you to assign realistic priorities'' [11]. 141 Benchmarks were used to establish the budget and adequate contingencies exist Benchmarks were used to establish the schedule and adequate contingencies exist Quality requirements have been agreed and documented D. Baccarini, R. Archer / International Journal of Project Management 19 (2001) 139±145 142 D. Baccarini, R. Archer / International Journal of Project Management 19 (2001) 139±145 The objective of Step 2 of CAMS' risk management process Ð Risk Management Planning Ð is to ensure that appropriate risk management plans are put in place. The level of detail in the risk management plan should be compatible with the level of risk of the project. If Step 1 (Risk Rating) produces a ``high'' or ``signi®cant'' rating, the risk management plan is carried out in detail. If the rating is ``moderate'' or ``low'', a less detailed plan is acceptable. 5. PRR: objective and process The objective of PRR is ``to assess the relative level of risk of contracting projects so that an appropriate level of eort can be applied to the management of those projects'' [2]. The PRR process is computer-based using a database (Access) application that is available to all project managers within CAMS. The process provides a dierent risk rating methodology for a wide variety of projects such as building, goods and services, information technology and outsourcing. The example provided here applies to building projects. CAMS (1998) states that ``there are certain characteristics of contracting projects that give a reasonable indication of possible future problems'' [1]. These are: . How well the contract targets were established (Table 1)? The ways in which contracting objectives of cost, time and quality are established provide a good indication of the likelihood of future problems. For example, if ®nancial year imperatives rather than a realistic assessment of an achievable date have driven the scheduled target date, it is unlikely that the target will be met. Table 1 shows how the ``riskiness'' of time, cost and quality objectives can be assessed from the manner in which the objective was established. In this table, a rating of ``5'' indicates a high likelihood of not meeting the target, whereas a rating of ``1'' indicates that there is a good chance that the target will be met. . The impact if these objectives are not met (Table 2). Some contract objectives might be more critical than others. For example, the objective to establish the contract by the end of the ®nancial year might not be important, but the objective to ensure the project delivery is 99% reliable might be critical to the organisation's business. Assessing the objectives in this way helps in understanding the consequence if they are not met. Table 2 shows how the consequences of not meeting the time, cost and quality objectives can be assessed. In this table, a rating of ``5'' indicates a high impact if the target is not met, whereas a rating of ``1'' indicates that meeting the target is not critical to the success of the contract. . Features of the contracting project (Table 3). Assessing the likelihood and consequences of not meeting the contract objectives, as described above, is one way of foreseeing problems. Another way is to look at the features of the project, sometimes called ``risk drivers''. Risk drivers are ``observable phenomena that are likely to drive the possibility of some risked consequence which depends, in part at least, on the occurrence of this phenomena'' [12]. Examples of risk drivers include complexity, location, speed, novelty, technology requirements, intensity of eort, and client characteristics [12±14]. So, for example, we would expect a lower risk environment working in a project similar to previous experiences and a higher risk environment for a highly novel project [15]. Table 3 shows how the likelihood of problems can be assessed using these factors. In this table, a rating of ``5'' indicates a high likelihood of problems Table 2 Risk factors: consequence of failure to meet targets Factor The eect if the COST targets are not met Estimated Total Cost (ETC) of the project The eect if the TIME targets are not met Project or contract period The eect if the QUALITY targets are not met Rating 5 4 3 2 1 No additional funds available and project will not proceed >$10m No additional funds available and scope reduced $5m±$10m Request for additional funds would be lengthy and embarrassing $1m±$5m Some scope for additional funds Additional funds available $100k±$1m <$100k Cannot be accommodated under any circumstances Severe disruption to clients business Delays undesirable but could be managed Completion date not important >24 months Client's business ceases altogether 18±24 months Client's business severely disrupted 12±18 months Client's business moderately aected Alternative arrangements available 6±12 months Tolerable eect on client's business <6 months No noticeable eect on client's business D. Baccarini, R. Archer / International Journal of Project Management 19 (2001) 139±145 143 each risk factor is allocated a score between 1 and 5, but the number does not necessarily relate to the actual magnitude of risk. Risk management is not an exact science. The risk rating is used to rank projects in order of ``riskiness'', but the rating is relatively meaningless by itself. The project manager scores each factor in Tables 1±3 re¯ecting the level of risk. These scores are the only inputs required. Then the computer program calculates the risk ranking for the project. Once the project managers arising from the area of the project, whereas a rating of ``1'' indicates that there is a low likelihood of problems in this area. 6. PRR: operation and outputs Using the three risk categories described above, it is possible to calculate a risk rating for a project. The PRR process uses semi-quantitative analysis [7]. That is, Table 3 Risk factors: project features Factor Rating 5 4 3 2 1 Uniqueness of the product Prototype incorporating new techniques Conventional project Modi®cations to an existing design One of a series of repetitions Complexity of the deliverables Outcome based contracts (e.g., Peel Health Campus) Private sector funding or joint venture Unusual project (out of the ordinary) Coordination of services (e.g., FM, Landsdale PS) Capital works not yet approved or requested Likely to be inadequate Design and construct Supply and installation Supply only Capital works in forward estimates Capital works already allocated Recurrent funds in current year Tight budget achievable with control Regional, north of 26th parallel Additions to occupied areas Hazardous materials exist, but do not form part of the work Generic project brief available Site identi®ed but not yet purchased Needs justi®ed but may change through project Approval required are known and documented Inexperienced single client or client's rep Adequate with some contingency Adequate with generous contingency Regional, south of 26th parallel Well clear of occupied areas Unlikely to encounter hazardous materials Metropolitan Feasibility study completed New site purchased Detailed project brief available Existing site Need justi®ed based on historical information Few approvals required or majority have been obtained Experienced multiple clients Need fully justi®ed through recognised processes No approval required or all have been obtained Experienced single client Single client reluctant or relationship not established. Limited number of competent contractors Good working relationship (multiple clients) Adequate number of competent contractors Good working relationship (single client) Abundance of competent contractors Public open tender Selected tenderers Design competition Tendered outside CAMS Full EOI and RFP Period panel consultant High pro®le client or project Stakeholder groups involved Project may attract stakeholder or media interest Consultant selected using approved processes Project unlikely to attract stakeholder or media interest Financing Adequacy of funds Totally inadequate Project location Remote, inaccessible Remote, accessible Project surroundings Activities in occupied areas Working with existing hazardous materials Staging within occupied areas Possibly involves existing hazardous materials Brief project description Several sites identi®ed Justi®cation is questionable Hazardous materials De®nition of project Site availability No project information available Site not identi®ed Project justi®cation Need has not been justi®ed Project approvals Unidenti®ed approvals required at all levels of Government Inexperienced multiple clients or client's reps Client's experience Client relationships Availability and competency of contractors Procurement method Consultant selection Stakeholder interest Clients reluctant or relationships not established Unknown contractors No tendering and involving sponsorship Selection without approved processes High level of political, community or media sensitivity Potential approval delays have been identi®ed Mixed experience amongst clients or client's rep Mixed relationship with clients Limited number of unreliable contractors Negotiated tender Green®eld site No known hazardous materials 144 D. Baccarini, R. Archer / International Journal of Project Management 19 (2001) 139±145 have become familiar with the PRR process, it typically takes 10±15 min to complete the tables and arrive at a project risk ranking. The PRR process entails the following: 1. Project details are entered, e.g., client, project manager, project description. 2. Scores are assigned to each of the risk factors, as detailed in Tables 1±3. 3. The project risk rating is arrived at by deriving a rating for the likelihood and consequence factors and multiplying them by using the principle risk = likelihood consequence. So, the score for each risk factor is allocated automatically to either likelihood or consequence of cost, time or quality. The determination of the most appropriate allocation of the score for each risk factor to either likelihood or consequence was derived from discussions with CAMS sta. (Note: commercial con®dentiality prevents any further elaboration). 4. The PRR is then displayed, calculated by: averaging the likelihood for cost, time and quality; averaging the consequence for cost, time and quality; deriving a risk rating for each of cost, time and quality, by multiplying their respective likelihood and consequence average scores; selecting the highest of the time, cost and quality ratings as the overall project risk rating. 5. The PRR score is then categorised as follows: 1±5 = low; 5±10 = moderate; 10±15 = signi®cant; 15±25 = high. A risk management plan is required for projects having a ``signi®cant'' or ``high'' PRR. Projects with a low or moderate PRR rely on project management processes to manage the risks. 6. The program provides a facility to produce a graph (Fig. 2 shows the results of an actual risk rating exercise) showing the relative risks of the cost, time and quality aspects of the project; and a chart (Fig. 3 shows the results of an actual risk rating exercise) that shows the relative levels of the various project features (i.e., Table 3) on the project so that the major sources of risk can be easily identi®ed. 7. Reports are available from the system for individual projects or multiple projects. 7. How PRR was formulated? The PRR process described herein was formulated by running workshops with relevant CAMS sta at which typical project risks were identi®ed. These were then distilled through a number of iterations into a set of Fig. 2. Final risk rating for time, cost, quality Ð example. Fig. 3. Final risk rating for risk factors (project features) Ð example. PRR risk factors. The PRR process was applied to real projects to identify any problems such as missing factors, inconsistencies or illogical components. Finally, the process was reassessed and altered and is under continuous review. 8. Conclusion In the ®rst year of its operation, the PRR process has been applied to over 400 projects. CAMS is involved in a multitude of projects. It recognises that risk management is one of its core competencies and is also aware that its resources are limited. The PRR process allows for the eective and ecient allocation of resources for the management of project risks. D. Baccarini, R. Archer / International Journal of Project Management 19 (2001) 139±145 As with the introduction of any new process into an organisation, the PRR has been continuously re®ned and further re®nement is expected. For example, consideration is presently being given to creating a dierent set of risk factors when the PRR process is applied in the contract management phase of a project. This is because at this phase many risks have been managed and/or transferred to the contractor. All projects require a champion; so, the implementation of the PRR process needed senior management support. The successful introduction and use of the PRR process has been largely due to the support from the CEO. The overall risk rating for a project produced by the PRR process tends to match the project managers' intuitive judgement of the `riskiness' of the project. Consequently, this has encouraged the acceptance of the PRR by CAMS' project managers. References [1] CAMS. Managing risks in contracting. Perth: Government of Western Australia, 1998. [2] CAMS. Annual Report 1996/7. Perth: Government of Western Australia, 1997. [3] Pearson D. Managing public sector risk. In: ARIMA Conference, Perth, Western Australia, 17th October, 1994, p. 84±90. [4] Report of the Independent Commission to Review Public Sector Finances Ð Agenda for Reform. Perth: Government of Western Australia, 1993. [5] Oce of the Auditor General Western Australia. First General Report 1994 on Departments, Statutory Authorities (including hospitals), Subsidiaries and Request Audits. Report No. 3 June. Perth: Government of Western Australia, 1994. 145 [6] Treasurer's Instruction 109 Ð Risk Management. Western Australian Government, July 1997. [7] Standards Australia. Risk management. AS/NZS 4360. Homebush, NSW, 1999. [8] Wideman RM. Project and program risk management: a guide to managing risks and opportunities. Upper Darby, PA: Project Management Institute, 1992. [9] Al-Bahar JF, Crandall KC. Risk management in construction projects: a systematic approach for contractors. In: Counseil International du Batiment W55/W65 Joint Symposium. Sydney, 14±21 March, 1990. [10] Project Management Institute. A guide to the project management body of knowledge. Upper Darby, PA: PMI, 1996. [11] Grey S. Practical risk assessment for project management. Chichester: Wiley, 1995. [12] Berkeley D, Humphreys PC, Thomas RD. Project risk action management. Construction Management and Economics 1991;9:3±17. [13] Thompson PA, Perry JG. Engineering construction risks. London: Thomas Telford, 1992. [14] Raftery J. Risk analysis in project management. London: E & FN Spon, 1994. [15] Rosenau MD. Successful project management. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991. David Baccarini holds an M.Sc. in property development (project management) from South Bank University and is a Senior Lecturer in Project Management at Curtin University of Technology. He introduced a generically-based Master of Project Management program in 1993, the ®rst in Western Australia. Richard Archer is the Risk Management Adviser at Contract and Management Services (CAMS). He established CAMS' risk management policies and procedures and developed risk management processes and tools to support CAMS contracting and project management activities.