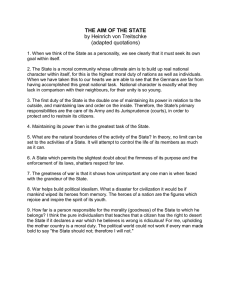

Legal Philosophy Study Notes: Pascual's Introduction

advertisement