Mind-Body Practice & Pro-Environmental Engagement

advertisement

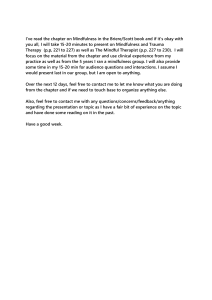

Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Environmental Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jep Hype and hope? Mind-body practice predicts pro-environmental engagement through global identity T Laura S. Loy∗, Gerhard Reese Department of Social, Environmental and Economic Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Koblenz-Landau, Fortstraße 7, 76829, Landau, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Handling editor. Sander van der Linden Humanity is facing global environmental challenges and a global identity has been found to predict pro-environmental engagement. As the origins of a global identity are not broadly understood, we aimed to contribute to investigating its predictors. One way to cultivate a global identity might be through the mind-body practices of yoga and meditation that an increasing number of people pursue, as it is one traditional goal of these practices to evoke a sense of connectedness with all humans. In our online survey study, we compared 113 mind-body practitioners with 145 non-practitioners and found that mind-body practice positively predicted one of two dimensions of a global identity – namely global self-definition –, pro-environmental behaviour, and climate policy support. Moreover, mind-body practice positively and indirectly predicted pro-environmental behaviour as well as climate policy support through a stronger global self-definition. We thus suggest that mind-body practices might bear the potential for contributing to a sustainable society and that their causal effects on global identity should be examined in future research. Keywords: Meditation Yoga Mindfulness Pro-environmental behaviour Climate policy support Global identity 1. Introduction Humanity is facing global environmental challenges such as climate change or the spread of micro plastics in the oceans that can be only solved or attenuated by collective efforts (IPCC, 2014; Ripple et al., 2017; Rockström et al., 2009). These collective efforts require individual behaviour. The role of social influences and other group processes on people's engagement to limit environmental crises has therefore been increasingly discussed in recent years (for a review, see Fritsche, Barth, Jugert, Masson, & Reese, 2018). Specifically, research on global identity, defined as a sense of connectedness with people all over the world and a concern for their well-being (McFarland, Webb, & Brown, 2012; Reese, 2016; Reese, Proch, & Finn, 2015), found that it predicts pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours (Lee, Ashton, Choi, & Zachariassen, 2015; Leung, Koh, & Tam, 2015; Renger & Reese, 2017; Reysen & Hackett, 2016; Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013; Rosenmann, Reese, & Cameron, 2016; Running, 2013). As the origins of a global identity and ways to foster identification with people all over the world are still not broadly understood (for an overview, see McFarland et al., 2019), we seek to address this gap. One way to cultivate a global identity might be through the mindbody practices of meditation and yoga that an increasing number of people pursue. In the following, we use the term mind-body practice to ∗ include both. A traditional goal of mind-body practices is compassion and connectedness with all other humans and the natural world (Hofmann, Grossman, & Hinton, 2011; Singer & Bolz, 2013; Trautwein, Naranjo, & Schmidt, 2014). Certain techniques such as loving-kindness (or metta) meditation even specifically focus on its cultivation (Kristeller & Johnson, 2005). Research examining mind-body practice interventions revealed positive effects on social and nature connectedness (Aspy & Proeve, 2017; Hutcherson, Seppala, & Gross, 2008) and prosocial behaviour (Donald et al., 2019). However, to our knowledge, no research has explicitly examined the relation between mind-body practice and the sense of connectedness with people all over the world and a concern for their well-being. Connectedness is often regarded as the more advanced secondary outcome of mind-body practices, while the primary goal – and initial core focus of psychological research on mind-body practices – is the cultivation of mindfulness, defined as an intentional and non-judgemental awareness of present moment experiences (Bishop et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 1990). Research has found that people who are characterised by mindfulness as a trait feel more connected to nature (e.g., Howell, Dopko, Passmore, & Buro, 2011; for an overview, see Schutte & Malouff, 2018) and engage more in environmental protection (e.g., Geiger, Otto, & Schrader, 2018; for an overview, see Fischer, Stanszus, Geiger, Grossman, & Schrader, 2017; Geiger, Grossman, & Schrader, Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: loy@uni-landau.de (L.S. Loy), reese@uni-landau.de (G. Reese). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101340 Received 1 April 2019; Received in revised form 27 August 2019; Accepted 27 August 2019 Available online 29 August 2019 0272-4944/ © 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese 2018). It has thus been argued that mind-body practice might contribute to a more sustainable society (for theoretical statements, see Ericson, Kjønstad, & Barstad, 2014; Patel & Holm, 2017). However, whether actual practice relates to pro-environmental engagement has been rarely investigated (for the only intervention study which found no effects, see Geiger, Grossman et al., 2018). Our research thus brings together two recent strands of research on predictors of prosocial and pro-environmental engagement: mind-body practice and mindfulness, on the one hand, and global identity, on the other hand. In our study, we compared mind-body practitioners (yoga, meditation, or both) with non-practitioners. We examined whether they differ in their global identity and pro-environmental engagement, and whether the cultivation of global identity might be a potential mechanism by which mind-body practice could encourage pro-environmental engagement. detachment (Schindler, Pfattheicher, & Reinhard, 2019). 2.2. Mind-body practice and global identity The concept of a global identity has been theoretically elaborated and empirically investigated under different labels (for an overview, see McFarland et al., 2019). We refer to the conceptualisation named “identification with all humanity”, which was introduced by McFarland et al. (2012) and differentiated by Reese et al. (2015). This conceptualisation is rooted in self-categorisation theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987) as well as the humanistic theories of personal growth and maturity by Maslow (1954) and Adler (1927/ 1954). Therein, global identity comprises the dimensions of global selfdefinition (i.e., the self-categorisation to an inclusive ingroup that covers all humanity) and global self-investment (i.e., a concern and solidary caring for people all over the world). However, even broader conceptualisations exist that go beyond identification with humanity to include all living, namely humans, animals, and plants (e.g., Arnocky, Stroink, & DeCicco, 2007; Leary, Tipsord, & Tate, 2008), and thus the concept of nature connectedness (Mayer & Frantz, 2004). Previous experimental research suggests that a global identity could be promoted by making global interconnection and diversity salient (Reese et al., 2015, Study 3) or by bringing individuals into contact with people from another continent (Römpke, Fritsche, & Reese, 2019). Correlational research further proposes that global awareness (Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013) and being respectfully treated as a human being (Renger & Reese, 2017) may strengthen global identity. Moreover, openness to experience and empathy may be considered as antecedents of a global identity (Hamer, McFarland, & Penczek, 2019; for a review, see McFarland et al., 2019). We suggest mind-body practice as a potential opportunity to cultivate a global identity. Trautwein et al. (2014) argued that self-other connectedness is one of the fundamental mechanisms behind the effects of mind-body practices on prosocial outcomes. They reasoned that meditation shifts the focus from the cognitive-conceptual self to the bodily-affective self. This shift allows to see more similarities than differences between people and opens up the strict distinction between ingroup and outgroup as well as between individual self and other to a more inclusive and interdependent representation (see Cross, Hardin, & Gercek-Swing, 2011). Thereby, a stronger empathic connection with others becomes possible (see also Trautwein, 2018; Trautwein, Naranjo, & Schmidt, 2016). Connectedness with all humans is a goal stated within the Buddhist philosophy of mind-body practices (Mannschatz & Baur, 2018). Metta meditation, for example, explicitly involves the stepwise development of compassion for and connectedness with close and distant others, beginning with one's personal network, over neutral people or people with whom one has difficulties, up to strangers all over the world (Salzberg, 2002; Singer & Bolz, 2013). One of the most popular meditation mantras guiding mind-body practices is “Lokah Samastah Sukhino Bhavantu”, which can be translated as “May all beings everywhere be happy and free, and may my thoughts, words, and actions contribute to this”. As this mantra shows, the idea of connectedness that is cultivated in mind-body practice is not limited to humans but includes all living beings and also connectedness with nature per se. Empirical evidence suggests effects of mind-body practices on general social connectedness and connectedness with nature. For example, Aspy and Proeve (2017) compared brief 14-min interventions of progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness meditation, and loving-kindness meditation in an experiment with undergraduate students. They found a stronger social and nature connectedness in the latter two groups. In an experiment by Hutcherson et al. (2008), participants reported more similarity, connectedness, and positivity when evaluating photographs of strangers after a loving-kindness meditation intervention compared to a control group. On the basis of this evidence, we assumed: H1: Mind-body practitioners (yoga, meditation, or both) have a 2. Theoretical background 2.1. Mind-body practice An increasing number of people all over the world practice meditation and yoga (e.g., Clarke, Barnes, Black, Stussmann, & Nahin, 2018; Statista, 2017, 2018). These ancient contemplative mind-body techniques originate in Buddhist philosophy, but are today widely implemented beyond spiritual contexts in various styles. In meditation, attention is typically focussed on an object, thought, or body sensation such as the breath, with the goal to quiet the mind and cultivate awareness (KabatZinn, 1994). Yoga can be regarded as a kind of meditation in movement. Here, attention is usually focussed on the breath while practicing body postures (i.e., “asanas”). Moreover, yoga classes typically include explicit breathing exercises (i.e., “pranayama”) as well as sitting meditation elements and deep relaxation techniques (Büssing, Hedtstück, Khalsa, Ostermann, & Heusser, 2012). A core aim of mind-body practices is the cultivation of mindfulness. The widely used concepts by Kabat-Zinn (1990) and Bishop et al. (2004) describe two core aspects. First, an awareness for internal and external experiences (e.g., thoughts, emotions, sensations) in the present moment and an ability not to get distracted. Second, an accepting and open attitude towards these experiences and an ability not to identify with them, evaluate them, or react to them (Geiger, Otto et al., 2018). Further differentiating these aspects, Baer, Smith, and Allen (2004) suggested four mindfulness skills, namely observing internal and external stimuli, describing these, acting with awareness, and accepting without judgment. We refer to and used a measure based on this conceptualisation in our study. Later, Baer et al. (2008) added a fifth dimension named non-reactivity. Mindfulness as a state is cultivated in mind-body practices and is thought to result in an individual trait difference over time (Rau & Williams, 2016). Research on mind-body practices initially focussed mostly on their effects on individual well-being (Brown & Ryan, 2003), such as reduced stress, depression, or anxiety (Chiesa & Serretti, 2011; Goyal et al., 2014; Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004; Khoury, Sharma, Rush, & Fournier, 2015), cognitive measures (Eberth & Sedlmeier, 2012; Sedlmeier et al., 2012), or work-related outcomes (Virgili, 2015). However, a further core aim of mind-body practices is social in nature, namely the cultivation of compassion and social connectedness (Hofmann et al., 2011). Therefore, scholarly interest in understanding not only individual but also social implications recently grew. Several studies revealed, for example, positive impacts on compassion (Condon, Desbordes, Miller, & DeSteno, 2013), altruism (Wallmark, Safarzadeh, Daukantaitė, & Maddux, 2013), reduced intergroup bias (Kang, Gray, & Dovidio, 2014), and prosocial behaviour (Leiberg, Klimecki, & Singer, 2011; for an overview, see Donald et al., 2019; Luberto et al., 2018). At the same time, also critical voices were raised (van Dam et al., 2018) that cautioned against the possibility to foster self-enhancement (Gebauer et al., 2018) or reduce moral reactivity due to emotional 2 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese stronger global identity regarding its dimensions of global self-definition (1a) and self-investment (1b) than non-practitioners. health behaviour. Hunecke and Richter (2018) found that acting with awareness positively predicted sustainable food consumption through construction of meaning, sustainability-related meaning, and personal norm. Finally, Jacob, Jovic, and Brinkerhoff (2009) assessed the frequency of certain experiences associated with mindfulness meditation (i.e., mind slowing down, stillness, seeing thoughts without becoming attached to them, watching emotions without being carried away by them) and found these to be related to sustainable household choices and food consumption. In their Study 2, Panno et al. (2017) found that practitioners of Buddhist meditation reported more pro-environmental behaviour as well as belief in global climate change than non-practitioners. We are aware of only one randomised controlled mind-body intervention study which specifically aimed at promoting sustainable consumption (for the curriculum, see Stanszus et al., 2017). The 8-week course that taught mindfulness exercises and discussed sustainability issues of consumption did not affect participants’ behaviour regarding nutrition or clothing (Geiger, Grossman et al., 2018). Summing up these results, mindfulness as a trait predicted pro-environmental behaviour in various studies, and proenvironmental behaviour was higher amongst meditation practitioners than non-practitioners in one study. One mindfulness intervention did not raise sustainable consumption. On the basis of the outlined evidence, we hypothesised: H4: Mind-body practitioners act more pro-environmentally compared to non-practitioners. H5: Mind-body practitioners support climate policies more compared to non-practitioners. As outlined, prior research suggested and examined several mechanisms that might explain the relation between mindfulness as a trait and pro-environmental behaviour with nature connectedness among them (Barbaro & Pickett, 2016). No study investigated connectedness with all humans and compared mind-body practitioners and nonpractitioners in this regard. Connecting the outlined theoretical reasoning and empirical results on mind-body practice, mindfulness, global identity, and pro-environmental engagement, we suggest global identity as an outcome of mind-body practice that might partly explain potential positive impacts of mind-body practice on pro-environmental engagement: H6: Mind-body practice indirectly predicts pro-environmental behaviour through a stronger global identity, regarding its dimensions of global self-definition (6a) and self-investment (6b). H7: Mind-body practice indirectly predicts climate policy support through a stronger global identity, regarding its dimensions of global self-definition (7a) and self-investment (7b). 2.3. Global identity and pro-environmental engagement Pro-environmental engagement can be shown in the private sphere (e.g., by behaviours involving sustainable product purchases and uses, mobility choices, or energy consumption patterns) and the public sphere (e.g., by supporting policies that aim at environmental protection; Stern, 2000). In our research, we were thus interested in examining people's pro-environmental behaviour across different domains (Kaiser & Wilson, 2004) as well as concrete climate policy support (Drews & van den Bergh, 2015) as indicators of engagement. Global identity positively predicted pro-environmental attitudes (Lee et al., 2015; Renger & Reese, 2017; Reysen & Hackett, 2016; Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013), intentions and behaviours (DerKarabetian, Cao, & Alfaro, 2014; Lee et al., 2015; Renger & Reese, 2017), support for environmental movements (Leung et al., 2015; Rosenmann et al., 2016), and the relevance attributed to climate change (Katzarska-Miller, Reysen, Kamble, & Vithoji, 2012; Running, 2013). Furthermore, global identity positively predicted global social engagement such as collective action intentions on behalf of climate change victims (Barth, Jugert, Wutzler, & Fritsche, 2015), cooperation in a global public goods dilemma (Buchan et al., 2011), fair trade consumption (Reese & Kohlmann, 2015), behavioural intentions in favour of global equality (Reese, Proch, & Cohrs, 2014), and willingness to donate to humanitarian charities (McFarland et al., 2012). Summing up these results, global identity predicted engagement in global social and environmental issues. We hypothesised on the basis of this evidence: H2: Global identity, regarding its dimensions of global self-definition (2a) and self-investment (2b), positively predicts pro-environmental behaviour. H3: Global identity, regarding its dimensions of global self-definition (3a) and self-investment (3b), positively predicts climate policy support. 2.4. Mind-body practice and pro-environmental engagement Empirical evidence suggests a relation between mindfulness as a trait and pro-environmental engagement. In a study by Brown and Kasser (2005), the mindfulness dimension of acting with awareness positively predicted broad measures of pro-environmental behaviours. Amel, Manning, and Scott (2009) found a positive relation between acting with awareness and the degree to which participants evaluated themselves as behaving green. Barbaro and Pickett (2016) examined five dimensions of mindfulness in two studies and revealed positive relations of observing, describing, acting with awareness (one of the two studies only), and non-reactivity with pro-environmental behaviour. Geiger, Otto, et al. (2018) conducted two studies and reported positive relations of observing, describing, and non-reactivity with proenvironmental behaviour. Several authors reflected about potential mechanisms linking mindfulness and pro-environmental engagement. A recent review reasoned that mindfulness might foster sustainable consumption through a disruption of routines, an alignment of attitudes and behaviours, and a promotion of non-materialistic values, well-being, and prosocial behavioural tendencies (Fischer et al., 2017). Moreover, five studies empirically investigated possible mediators. Barbaro and Pickett (2016) found an indirect relation between mindfulness and pro-environmental behaviour through a stronger connectedness with nature. In an study by Panno et al. (2017), acting with awareness was indirectly related to proenvironmental behaviour through a weaker social dominance orientation (SDO). Geiger, Otto, et al. (2018) found an indirect relation between mindfulness and pro-environmental behaviour through stronger 3. Methods 3.1. Procedure and participants We conducted this study using an online questionnaire programmed with the software package SoSci Survey (www.soscisurvey.de, Leiner, 2019). With the aim to include people with and without mind-body practice, we recruited study participants with flyers and e-mails on the campus of a German university, in several yoga and meditation centres, online forums, and via personal networks in December 2018 and January 2019. Psychology students had the possibility to earn class credit for participating and n = 120 made use of this. There were no other incentives for participating in the study. We followed the APA guidelines for the ethical conduct of research. The questionnaire included an informed consent as well as a debriefing. We calculated an a priori power analysis using G*Power 3 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) to determine the desired sample size for detecting small to medium sized differences between two groups (i.e., mind-body practitioners vs. non-practitioners; Cohen's d = 0.35) and small to medium sized correlations between variables (r = .20) at 3 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese p < .05 with 80% test power. The estimated sample sizes were N = 204 and N = 153, respectively. The actually acquired sample consisted of N = 258 participants (200 women, 57 men, 1 other; M = 27.0 years of age, SD = 13.3); 145 of them practiced neither yoga nor meditation, 113 pursued a mindbody practice (52 yoga only, 31 meditation only, 30 both), hence, we compared these two groups (for further sample information, see Supplemental Material 1.1). complemented them with own items as we intended to specifically include more questions on the currently discussed topic of plastic use (Heidbreder, Bablok, Drews, & Menzel, 2019). The items also covered other aspects of ecological consumption, energy use, and mobility (e.g., “If I receive a plastic bag in a store, I take it”, “I buy seasonal fruit and vegetables”, “I leave appliances on standby (e.g., TV, computer)”, “I fly within Germany”). Participants indicated how often they conducted each behaviour on a scale with five answer options. Following Kaiser and Wilson (2000, 2004), we dichotomised items on pro-environmental behaviours as 0 (never, seldom, once in a while) or 1 (often, very often), items on environmentally damaging behaviours as 0 (once in a while, often, very often) or 1 (never, seldom). A 1-dimensional Rasch analysis of all items resulted in a scale with a satisfactory person separation reliability of Rp = .72. Item mean square infit values were between 0.78 and 1.15 and thus all below the recommended threshold of 1.30 for samples smaller than 500 (Bond & Fox, 2007). 4. Material 4.1. Mind-body practice We asked participants whether they practice meditation (yes, no) and yoga (yes, no) and built the dichotomous predictor variable mindbody practice as 0 (none) and 1 (meditation, yoga, or both). Moreover, we asked practitioners how long they have been practicing and how much time they spend practicing (for results see Supplemental Material 1.2.1). 4.4. Climate policy support 4.2. Global identity We adapted items from Tobler, Visschers, and Siegrist (2012) and the European Social Survey (ESS, 2016) to measure climate policy support. We asked participants whether they were against or in favour of six measures the government could enact to limit climate change (e.g., “subsidies for renewable energy (e.g., solar, wind, and water energy)”). They answered on a scale ranging from 1 (fully against) to 7 (fully in favour). The CFA of the 1-dimensional model did not yield satisfactory model fit with regard to CFI and TLI, χ2(9) = 31.51, p < .001; CFI = .91; TLI = .85; RMSEA = .098, 90% CI [.069, .130]; SRMR = .057. Factor loadings were between .35 and .82. We discuss this issue in the Supplemental Material 1.2.3. We adapted the German version (Reese et al., 2015) of the Identification with all Humanity Scale (McFarland et al., 2012) to measure global identity. The original measure assesses three levels of social identification (i.e., with people in the community, country, and the whole world) with nine items each. Four of the global items were found to load on the dimension of self-definition, four on the dimension of self-investment, and one on both (Reese et al., 2015; Reysen & Hackett, 2016). In order to reduce the length of our questionnaire, we formulated five statements reflecting global self-definition (e.g., “I think of people all over the world as ‘we’“) and five reflecting global self-investment (e.g., “I want to help people all over the world”) based on the original items. We slightly adapted some wording, reformulated the double-loading item as two statements, and changed the answer format to participants' agreement on a scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 7 (fully applies; see also Loy, 2018). The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the 2-dimensional model with correlating factors yielded satisfactory model fit, χ2(34) = 72.29, p < .001; CFI = .97; TLI = .96; RMSEA = .066, 90% CI [.048, .084]; SRMR = .035. Factor loadings were between .62 and .85. The covariance of the two dimensions was .90 (a 1-dimensional model did not yield satisfactory model fit, see Supplemental Material 1.2.2. However, the strong relation speaks for a second-order factor of global identity). 4.5. Mindfulness We used the German short version (KIMS-D-Short, Höfling, Ströhle, Michalak, & Heidenreich, 2011) of the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (Baer et al., 2004) in order to assess the trait of mindfulness as a multi-faceted construct with a validated, yet parsimonious measure. It comprised 20 items and asked participants to evaluate statements on a scale ranging from 1 (applies never or very seldom) to 5 (applies very often or always) referring to four dimensions of mindfulness: six items on observing (e.g., “When I'm walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving”), five on describing (e.g., “I'm good at finding the words to describe my feelings”), four on acting with awareness (e.g., “When I'm doing something, I'm only focussed on what I'm doing, nothing else”), and five on accepting without judgement (e.g., “I make judgments about whether my thoughts are good or bad”, reversecoded). The CFA of the 4-dimensional model with a superordinate 4.3. Pro-environmental behaviour We measured pro-environmental behaviour with a 24-item version of the General Ecological Behaviour Scale (GEB, Kaiser & Wilson, 2000, 2004). We selected items from different existing versions and Table 1 Psychometric properties of the measures. Variable M SD range items α ω AVE RP Global identity Self-definition Self-investment Pro-environmental behaviour a Climate policy support Mindfulness Observing Describing Acting with awareness Accepting without judgement 5.14 4.90 5.38 0.43 5.72 3.36 3.55 3.42 2.87 3.45 1.19 1.35 1.16 1.00 0.90 0.48 0.64 0.76 0.63 0.92 1.30–7.00 1.00–7.00 1.20–7.00 −3.37–4.25 2.50–7.00 2.15–4.65 1.67–5.00 1.40–5.00 1.25–4.75 1.20–5.00 10 5 5 24 6 20 6 5 4 5 .94 .91 .88 .78 .76 .83 .75 .83 .72 .87 .94 .91 .89 – .80 .88 .75 .85 .72 .87 .65 .67 .62 – .46 .48 .34 .55 .40 .58 – – – .72 – – – – – – Note. a Results are based on Rasch analysis. RP = Rasch model based person separation reliability. AVE = average variance extracted. 4 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese Table 2 Variables differentiated for mind-body practitioners and non-practitioners. Variable Global identity Self-definition Self-investment Pro-environmental behaviour a Climate policy support Mindfulness Observing Describing Acting with awareness Accepting without judgement Practitioners (n = 113) Non-practitioners (n = 145) M SD M SD 5.35 5.17 5.52 0.72 5.94 3.43 3.72 3.47 2.93 3.43 1.17 1.33 1.15 1.10 0.82 0.50 0.60 0.72 0.60 0.99 4.98 4.68 5.28 0.21 5.54 3.30 3.42 3.39 2.82 3.47 1.19 1.33 1.17 0.85 0.93 0.47 0.65 0.78 0.65 0.86 95% CI t p d [0.07, 0.65] [0.16, 0.82] [-0.05, 0.52] [0.26, 0.75] [0.17, 0.61] [0.004, 0.24] [0.15, 0.46] [-0.10, 0.27] [-0.05, 0.26] [-0.26, 0.19] 2.45 2.95 1.62 4.05 3.53 2.04 3.82 0.87 1.39 0.32 .015 .003 .107 < .001 < .001 .042 < .001 .385 .166 .748 0.31* 0.37* 0.20 0.52* 0.44* 0.26* 0.48* 0.11 0.17 0.04 b Note. a Results are based on Rasch analysis. b Welch test was used due to unequal variances. Effect size Cohen's d. 95% CI for mean difference. mindfulness factor yielded satisfactory model fit apart from CFI, χ2(166) = 275.60, p < .001; CFI = .93; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .051, 90% CI [.040, .061]; SRMR = .074. Factor loadings were between .46 and .87. Table 1 summarises the psychometric properties of the described scales. Details on our data analyses methods can be found in the Supplemental Material 1.3. Hypothesis 2b, global self-investment positively predicted pro-environmental behaviour as indicated by a small to medium direct relation (Model B: B = 0.17, 95%CI [0.07, 0.26], β = .21). Supporting Hypothesis 3a, global self-definition positively predicted climate policy support as indicated by a medium to large direct relation (Model A: B = 0.37, 95%CI [0.23, 0.50], β = .44). Supporting Hypothesis 3b, global self-investment positively predicted climate policy support as indicated by a medium to large direct relation (Model B: B = 0.34, 95%CI [0.20, 0.48], β = .38). Supporting Hypothesis 4, mind-body practitioners reported more pro-environmental behaviour compared to non-practitioners as indicated by small to medium direct relations (Model A: B = 0.41, 95%CI [0.17, 0.66], β = .21; Model B: B = 0.46, 95%CI [0.23, 0.70], β = .23) and total relations including the direct path as well as the indirect path through global self-definition and global self-investment, respectively (Model A and B: B = 0.51, 95%CI [0.26, 0.75], β = .25). Supporting Hypothesis 5, mind-body practitioners supported climate policies more compared to non-practitioners as indicated by small to medium direct relations (Model A: B = 0.34, 95%CI [0.05, 0.62], β = .15; Model B: B = 0.43, 95%CI [0.14, 0.72], β = .19) and total relations (Model A and B: B = 0.52, 95%CI [0.22, 083], β = .23). Supporting Hypothesis 6a, mind-body practice indirectly predicted pro-environmental behaviour through a stronger global self-definition. The indirect relation was of small size (Model A: B = 0.09, 95%CI [0.02, 0.17], β = .05). Hypothesis 6b was not confirmed as practice and pro-environmental behaviour were not indirectly related through global self-investment (Model B). Supporting Hypothesis 7a, mind-body practice indirectly predicted climate policy support through a stronger global self-definition. The indirect relation was of small size (Model A: B = 0.19, 95%CI [0.04, 0.34], β = .08). Hypothesis 7b was not confirmed as practice and climate policy support were not indirectly related through global self-investment (Model B). Fig. 2 provides facet plots for the assessed model variables differentiating non-practitioners and mind-body practitioners. The means of global self-definition, pro-environmental behaviour, and climate policy support (but not global self-investment) are higher for mind-body practitioners compared to non-practitioners, hence the frequency distribution is shifted to the right. 5. Results 5.1. Comparison of mind-body practitioners and non-practitioners Table 2 shows the descriptives of the assessed variables differentiated for mind-body practitioners and non-practitioners. Practitioners expressed a stronger global identity overall. Differentiating the two dimensions showed that only global self-definition but not selfinvestment was higher. They reported more pro-environmental behaviour and climate policy support. Regarding mindfulness, the overall score was higher for practitioners compared to non-practitioners. However, differentiating the four dimensions revealed that they only expressed a higher level of “observing”. Correlations between all study variables are provided in the Supplemental Material 2.1. 5.2. Hypotheses tests using structural equation modelling In order to test our hypotheses, we calculated two structural equation models, which both fit the data well (for alternative model tests, see Supplemental Material 2.2). Model A included global self-definition, χ2(61) = 112.65, p < .001; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .057, 90% CI [.042, .073]; SRMR = .045. It explained 3.6% of variance in global self-definition, 12.3% of variance in pro-environmental behaviour, and 23.8% of variance in climate policy support. Model B included global self-investment, χ2(61) = 93.11, p = .005; CFI = .97; TLI = .96; RMSEA = .045, 90% CI [.027, .062]; SRMR = .047. It explained 1.0% of variance in global self-investment, 10.8% of variance in pro-environmental behaviour, and 20.0% of variance in climate policy support (see Fig. 1). Results are summarised in Table 3. Supporting Hypothesis 1a, people who practiced mind-body techniques (yoga, meditation, or both) had a stronger global self-definition compared to non-practitioners as indicated by a small to medium direct relation (Model A: B = 0.51 95%CI [0.17, 0.86], β = .19). Hypothesis 1b was not confirmed as practitioners and non-practitioners did not differ in their global self-investment (Model B). Supporting Hypothesis 2a, global self-definition positively predicted pro-environmental behaviour as indicated by a small to medium direct relation (Model A: B = 0.18, 95%CI [0.10, 0.27], β = .25). Supporting 6. Discussion An increasing number of people pursue the mind-body practices of yoga and meditation. While individual benefits on well-being and psychological health have been widely studied for decades (Brown & Ryan, 2003), social or societal implications of this trend only recently received more scholarly attention (Donald et al., 2019). We were 5 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese Fig. 1. Structural equation models for the sample of n = 113 mind-body practitioners and n = 145 nonpractitioners. Pro-environmental behaviour was measured with 24 items and we used the scores resulting from a calibrated Rasch scale. Standardised beta coefficients are displayed. The coefficient of the relation between pro-environmental behaviour and climate policy support represents the residual covariance. specifically interested in their potential to motivate engagement to tackle global environmental challenges for a sustainable society (Fischer et al., 2017). In other words, we aimed to illuminate whether there lies hope for societal benefits in the current hype around mindbody practices. In our study, we examined whether people who practice mind-body techniques (yoga, meditation, or both) engage more in environmental protection compared to non-practitioners and whether this relation can be explained by a stronger global identity. Practitioners’ global self-definition (i.e., the degree to which they felt connected and similar to people all over the world) was indeed higher, while their global self-investment (i.e., the degree to which they felt concern and caring for the well-being of all humans) was not. Both dimensions of global identity were related to pro-environmental behaviour and climate policy support. Moreover, practitioners engaged more in pro-environmental behaviours and more strongly favoured climate policies compared to non-practitioners. We found indirect relations between mind-body practice and these two indicators of proenvironmental engagement through a stronger global self-definition. Hence, global self-definition but not self-investment seems to be a possible mechanism by which mind-body practice might encourage Table 3 Results of the structural equation models. Path Model A (global self-definition) H1a Direct relation practice – global self-definition H2a Direct relation global self-definition – pro-environmental behaviour H3a Direct relation global self-definition – climate policy support H4 Direct relation practice – pro-environmental behaviour Total relation practice – pro-environmental behaviour H5 Direct relation practice – climate policy support Total relation practice – climate policy support H6a Indirect relation practice – global self-definition – pro-environmental behaviour H7a Indirect relation practice – global self-definition – climate policy support Model B (global self-investment) H1b Direct relation practice – global self-investment H2b Direct relation global self- investment – pro-environmental behaviour H3b Direct relation global self- investment – climate policy support H4 Direct relation practice – pro-environmental behaviour Total relation practice – pro-environmental behaviour H5 Direct relation practice – climate policy support Total relation practice – climate policy support H6b Indirect relation practice – global self- investment – pro-environmental behaviour H7b Indirect relation practice – global self- investment – climate policy support 6 B SE p 95% CI β 0.51 0.18 0.37 0.41 0.51 0.34 0.52 0.09 0.19 0.18 0.04 0.07 0.12 0.12 0.15 0.16 0.04 0.08 .003 < .001 < .001 .001 < .001 .022 .001 .018 .013 [0.17, [0.10, [0.23, [0.17, [0.26, [0.05, [0.22, [0.02, [0.04, .19* .25* .44* .21* .25* .15* .23* .05* .08* 0.26 0.17 0.34 0.46 0.51 0.43 0.52 0.04 0.09 0.17 0.04 0.07 0.12 0.12 0.15 0.16 0.03 0.06 .118 < .001 < .001 < .001 < .001 .003 .001 .151 .141 [-0.07, 0.59] [0.07, 0.26] [0.20, 0.48] [0.23, 0.70] [0.26, 0.75] [0.14, 0.72] [0.22, 0.83] [-0.01, 0.10] [-0.03, 0.21] 0.86] 0.27] 0.50] 0.66] 0.75] 0.62] 0.83] 0.17] 0.34] .10 .21* .38* .23* .25* .19* .23* .02 .04 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese Fig. 2. Facet plots depicting the model variables in the sample of n = 145 non-practitioners and n = 113 mind-body practitioners. We used the mean scores for global self-definition, global self-investment, and climate policy support, and the calibrated Rasch person estimates for pro-environmental behaviour. engagement. Interestingly, global self-definition and self-investment predicted climate policy support more strongly than pro-environmental behaviour. A reason for this might be that policies are linked to more grouprelated consequences. In other words, policies may result in stronger collective impact than individual behaviours that are not concerted among many. practice that might in turn motivate global engagement. If mind-body practices strengthen global identification with humans all over the world, this would confirm one of the main goals behind meditation in its Buddhist tradition. It has to be kept in mind though that we cannot draw causal inferences from our study, yet. An alternative mechanism could be that globally identified individuals are more prone to devote themselves to mind-body practices. Our results further support the suggestion by Reese et al. (2015) that self-definition and self-investment should be differentially regarded as dimensions of a global identity (see also Reysen & Hackett, 2016). Reflecting on why only global self-definition but not self-investment differs between mind-body practitioners and non-practitioners, we 6.1. Implications On a theoretical level, we suggest that it is worthwhile to theorise and examine global identity as a possible outcome of mind-body 7 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese imagine that a feeling of connectedness and commonality with other people might be broached and cultivated in classes, whereas actionorientation might be less of a topic. Moreover, research on global identity consistently finds that global self-investment is higher than global self-definition (Loy, 2018; Reese et al., 2015). Hence, the idea or the feeling of connectedness with people around the world seems to be more difficult than caring about their well-being. Therefore, we find it specifically interesting to see that global self-definition is higher in practitioners of mind-body practices. These practices might be means to make the idea of a global connectedness more plausible or less abstract for people. In addition, our results contribute to the current discussion whether and which facets of mindfulness are strengthened in mind-body practices (Visted, Vøllestad, Nielsen, & Nielsen, 2015) and predict pro-environmental engagement (Geiger, Grossman et al., 2018). In our sample, mind-body practitioners only expressed a higher level of “observing” compared to non-practitioners. This could imply that not all dimensions of mindfulness are strengthened in the practices our sample pursues. Interestingly, the recent meta-analysis by Geiger, Grossman, et al. (2018) found the “observing” facet as strongest and most consistent predictor of pro-environmental behaviour, which aligns with our correlational findings (see Supplemental Material). Moreover, an increase in observing internal and external stimuli might facilitate a selfawareness that emphasises similarities over differences between people, which has been proposed as a mechanism initiated by mind-body practices that might lead to prosocial outcomes (Trautwein et al., 2014). Accordingly, the observing facet was the only mindfulness facet correlated with a global self-definition in our sample (see Supplemental Material). On a practical level, we suggest that the hype of practicing yoga and meditation in our society might indeed bear hope for positive societal outcomes that go beyond individual well-being and self-interest, such as identification with all humanity and engagement in environmental protection. Our study provides only a first hint towards this potential. However, if further studies can replicate our findings and additional causal experimental evidence can show that mind-body practices can foster global identity and pro-environmental engagement, more specific intervention approaches that aim at a sustainable development could be implemented (for an example on how to include sustainability issues in a mind-body intervention, see Stanszus et al., 2017). Based on our findings, we specifically suggest that teachers of mindbody classes could more often explicitly discuss the idea of a global identity, namely connectedness of all humans (or even all living) and similarities between people, in order to promote its cultivation. We suspect that the idea of a global identity might become less abstract during mind-body practice derived from the argument of Trautwein et al. (2014) that the shift from the cognitive-conceptual self to the bodily-affective self in mind-body practice might allow to see more similarities than differences between people, to foster self-other connectedness, and to open up ingroup-outgroup distinctions. We further propose that classes could include more metta meditation elements (next to mindfulness meditation which is more commonly practiced) in order to shift the focus to the well-being of others and to cultivate empathy (Singer & Bolz, 2013). An emphasis on cultivating global identity through mind-body practice could be implemented in diverse settings (e.g., regular classes in yoga or meditation centres, classes taught in schools, or also web-based material). Effects of respective interventions should be thoroughly evaluated in order to increase our understanding of the mechanisms at work. versa or bi-directional, or whether unconsidered third variables cause all three of them. Moreover, it has been discussed whether the term mediation should even be used for non-causal designs (Kline, 2016, p. 135). We decided to cautiously use the term mediation for our theoretical assumptions, but speak of indirect relations when describing the empirical results based on our correlational data. A follow-up study should use a randomised controlled trial design and compare a yoga and/or meditation intervention with a control group. An intervention could be short-term (e.g., one-time sessions or online instructions; Aspy & Proeve, 2017; Schindler et al., 2019) or long-term (e.g., courses or regular app use; Flett, Hayne, Riordan, Thompson, & Conner, 2018; Stanszus et al., 2017). Moreover, long-term follow-up measures should be aspired in order to examine the stability of possible effects and the potential evolvement of a global identity over time. If an experimental design is not feasible, an option would be a pre-post-test design comparing global identity and pro-environmental engagement before and after mind-body courses. A further limitation lies in the large proportion of students in our sample. For example, the overall high support of climate policies could be a result of this sample characteristic. Follow-up studies should replicate our research with diverse samples or representative samples, for example, of the German population. Our measure of climate policy support needs improvement (see Supplemental Material 1.2.3 for a discussion). Finally, our conceptualisation and measurement of mindfulness according to Baer et al. (2004) needs improvement. We decided to use the KIMS-D-Short (Höfling et al., 2011) as a validated short measure in German language covering four theoretical dimensions of mindfulness (observing internal and external stimuli, describing these, acting with awareness, and accepting without judgment). However, Baer et al. (2008) themselves later added a fifth dimension named “non-reactivity” and developed the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Even though a German version of this instrument exists (Michalak et al., 2016), we had decided not to use it due to its length of 39 items, thereby accepting not to cover the full breadth of the concept. Moreover, the “describe” component has been criticised by several authors for lacking content validity (Bishop et al., 2004; Grossman, 2010; for an overview, see Bergomi, Tschacher, & Kupper, 2013). The finding that mind-body practitioners in our sample only expressed a higher level of “observing” compared to non-practitioners could also be a hint that our used conceptualisation and measure are not satisfactorily valid. Future research could use the “Comprehensive Inventory of Mindfulness Experiences” (CHIME, Bergomi, Tschacher, & Kupper, 2014) with 37 items, which is based on a convincing analysis of former theoretical arguments and instruments. Alternatively, a new instrument could be constructed based on a recent review on mindfulness conceptualisations by Nilsson and Kazemi (2016). Extending and deepening our findings, future research should examine which type of practice people pursue. Questions could be 1) whether yoga focusses more on physical exercise or has an emphasis on meditative components; 2) which style of yoga is pursued (e.g., styles that focus on spiritual aspects or pursue a political agenda, such as Jivamukti Yoga explicitly promoting environmentalism); 3) whether meditation is focussed on cultivating mindfulness or also compassion. In addition, it could be explicitly asked whether connectedness with all humans has been broached as an issue in taught classes. Moreover, we deem it interesting to assess individuals’ motives for practicing (Mocanu, Mohr, Pouyan, Thuillard, & Dan-Glauser, 2018; Park, Riley, Bedesin, & Stewart, 2016). This could reveal whether connectedness evolves as a theme and whether certain motives (e.g., individual vs. prosocial benefits) differentially predict global identity and pro-environmental engagement. Connectedness with nature could be assessed parallel to connectedness with people all over the world to reveal their relative explanatory strength and interrelations (Schutte & Malouff, 2018). It should also be theoretically reflected whether connectedness with all 6.2. Limitations and future perspective The main limitation of our correlational and cross-sectional study is that it does not allow for causal inferences. Hence, we do not know whether mind-body practice results in global self-definition and proenvironmental engagement, whether the direction of effects is vice 8 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese humans and with nature may be dimensions of a broader concept reflecting one's sense of interdependence with all living and being part of a bigger whole (see e.g., Leary et al., 2008). Moreover, future research could examine whether similar relations occur at different levels of social identification (e.g., local, national, global; McFarland et al., 2012). While generally identifications on the different levels correlate substantially, there are differences in correlations with other constructs. For example, global identity often correlates negatively with SDO or right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), while national identification correlates positively (for a review, see McFarland et al., 2019). Interestingly, SDO and RWA are also negatively correlated with the trait of mindfulness and pro-environmental engagement (Nicol & De France, 2018; Panno et al., 2017; Stanley, Wilson, & Milfont, 2017). Possibly, people low in SDO and RWA develop a global identity, an interest in mind-body practices cultivating mindfulness, and pro-environmental engagement. Then, low SDO and RWA might be the common underlying cause for the relations we report here. Future research should thus include SDO and RWA as predictors and examine whether mind-body practice adds explained variance in global identity and pro-environmental engagement beyond them. Moreover, as outlined above, causality should be experimentally established. Here, it would be specifically revealing whether mind-body practice helps to cultivate a global identity even for people high in SDO and RWA. References Adler, A. (1927/1954). Understanding human nature. (W. B. Wolfe, Trans.; original work published 1927). Greenwich, CT: Fawcett. Amel, E. L., Manning, C. M., & Scott, B. A. (2009). Mindfulness and sustainable behavior: Pondering attention and awareness as means for increasing green behavior. Ecopsychology, 1(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2008.0005. Arnocky, S., Stroink, M., & DeCicco, T. (2007). Self-construal predicts environmental concern, cooperation, and conservation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(4), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.06.005. Aspy, D. J., & Proeve, M. (2017). Mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation: Effects on connectedness to humanity and to the natural world. Psychological Reports, 120(1), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116685867. Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment, 11(3), 191–206. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1073191104268029. Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1073191107313003. Barbaro, N., & Pickett, S. M. (2016). Mindfully green: Examining the effect of connectedness to nature on the relationship between mindfulness and engagement in pro-environmental behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.026. Barth, M., Jugert, P., Wutzler, M., & Fritsche, I. (2015). Absolute moral standards and global identity as independent predictors of collective action against global injustice. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(7), 918–930. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp. 2160. Bergomi, C., Tschacher, W., & Kupper, Z. (2013). The assessment of mindfulness with selfreport measures: Existing scales and open issues. Mindfulness, 4(3), 191–202. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0110-9. Bergomi, C., Tschacher, W., & Kupper, Z. (2014). Konstruktion und erste Validierung eines Fragebogens zur umfassenden Erfassung von Achtsamkeit. Diagnostica, 60(3), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000109. Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077. Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2007). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. Brown, K. W., & Kasser, T. (2005). Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-8207-8. Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. Buchan, N. R., Brewer, M. B., Grimalda, G., Wilson, R. K., Fatas, E., & Foddy, M. (2011). Global social identity and global cooperation. Psychological Science, 22(6), 821–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611409590. Büssing, A., Hedtstück, A., Khalsa, S. B. S., Ostermann, T., & Heusser, P. (2012). Development of specific aspects of spirituality during a 6-month intensive yoga practice. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 1–7. https://doi.org/ 10.1155/2012/981523. Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2011). Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 187(3), 441–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011. Clarke, T. C., Barnes, P. M., Black, L. I., Stussmann, B. J., & Nahin, R. L. (2018). Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among U.S. adults aged 18 and over. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db325-h.pdf. Condon, P., Desbordes, G., Miller, W. B., & DeSteno, D. (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2125–2127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613485603. Cross, S. E., Hardin, E. E., & Gercek-Swing, B. (2011). The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2), 142–179. https://doi. org/10.1177/1088868310373752. Der-Karabetian, A., Cao, Y., & Alfaro, M. (2014). Sustainable behavior, perceived globalization impact, world-mindedness, identity, and perceived risk in college samples from the United States, China, and Taiwan. Ecopsychology, 6(4), 218–233. https:// doi.org/10.1089/eco.2014.0035. Donald, J. N., Sahdra, B. K., van Zanden, B., Duineveld, J. J., Atkins, P. W. B., Marshall, S. L., et al. (2019). Does your mindfulness benefit others? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the link between mindfulness and prosocial behaviour. British Journal of Psychology, 110(1), 101–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12338. Drews, S., & van den Bergh, J. C. J. M. (2015). What explains public support for climate policies? A review of empirical and experimental studies. Climate Policy, 16(7), 855–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1058240. Eberth, J., & Sedlmeier, P. (2012). The effects of mindfulness meditation: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 3(3), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0101-x. Ericson, T., Kjønstad, B. G., & Barstad, A. (2014). Mindfulness and sustainability. Ecological Economics, 104, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.007. ESS (2016). Gesellschaft und Demokratie in Europa. Deutsche Teilstudie im Projekt „European Social Survey“ (Welle 8). Retrieved from https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ docs/round8/fieldwork/germany/ESS8_questionnaires_DE.pdf. Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146. 7. Conclusion We brought together two recent promising strands of research on predictors of prosocial and pro-environmental engagement: global identity and mind-body practice. We found that people who pursue the mind-body techniques of yoga and/or meditation express a stronger connectedness with people all over the world, report more pro-environmental behaviour, and are more in favour of climate policies. Moreover, practice indirectly predicted pro-environmental behaviour and climate policy support through such a higher global self-definition. We thus suggest that, in a next step, the causal effects of mind-body interventions on global identity should be investigated in order to reveal their potential for contributing to a sustainable society. Declarations of interest None. Funding This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Acknowledgements We thank the students in the research seminar for their valuable support in designing the questionnaire and collecting the data: Katrin Benitz, Mirja Feyerabend, Colin Gekeler, Lea Köhler, Laura Kommerscheidt, Alex Kosirew, Annika Leyendecker, Mona Nadig, Jul Nebel, Josra Redjeb, Saskia Scheinert, Amina Sefovic, Kristina Speckert, and Ida Wagner. Moreover, we thank Lea Heidbreder, Claudia Menzel, the editor Sander van der Linden as well as three anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Finally, we thank the yoga teacher Katja Seiffert for sharing her view on the topic. Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101340. 9 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese Fischer, D., Stanszus, L., Geiger, S. M., Grossman, P., & Schrader, U. (2017). Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings. Journal of Cleaner Production, 162, 544–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jclepro.2017.06.007. Flett, J. A. M., Hayne, H., Riordan, B. C., Thompson, L. M., & Conner, T. S. (2018). Mobile mindfulness meditation: A randomised controlled trial of the effect of two popular apps on mental health. Mindfulness, 1(2), 69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-0181050-9. Fritsche, I., Barth, M., Jugert, P., Masson, T., & Reese, G. (2018). A social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). Psychological Review, 125(2), 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000090. Gebauer, J. E., Nehrlich, A. D., Stahlberg, D., Sedikides, C., Hackenschmidt, A., Schick, D., & Mander, J. (2018). Mind-Body practices and the self: Yoga and meditation do not quiet the ego but instead boost self-enhancement. Psychological Science, 29(8), 1299–1308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618764621. Geiger, S. M., Grossman, P., & Schrader, U. (2018). Mindfulness and sustainability: Correlation or causation? Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 23–27. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.09.010. Geiger, S. M., Otto, S., & Schrader, U. (2018). Mindfully green and healthy: An indirect path from mindfulness to ecological behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 14. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02306. Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M. S., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., & Haythornthwaite, J. A. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. Grossman, P. (2010). Mindfulness for psychologists: Paying kind attention to the perceptible. Mindfulness, 1(2), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0012-7. Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. Hamer, K., McFarland, S., & Penczek, M. (2019). What lies beneath? Predictors of identification with all humanity. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.12.019. Heidbreder, L. M., Bablok, I., Drews, S., & Menzel, C. (2019). Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. The Science of the Total Environment, 668, 1077–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.437. Höfling, V., Ströhle, G., Michalak, J., & Heidenreich, T. (2011). A short version of the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(6), 639–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20778. Hofmann, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. (2011). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1126–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.003. Howell, A. J., Dopko, R. L., Passmore, H.-A., & Buro, K. (2011). Nature connectedness: Associations with well-being and mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(2), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037. Hunecke, M., & Richter, N. (2018). Mindfulness, construction of meaning, and sustainable food consumption. Mindfulness, 111(10), 1140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671018-0986-0. Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion, 8(5), 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0013237. IPCC (2014). In R. K. Pachauri, & L. A. Meyer (Eds.). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report: Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [core writing team. Retrieved from Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change website https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/ assessment-report/ar5/syr/AR5_SYR_FINAL_All_Topics.pdf. Jacob, J., Jovic, E., & Brinkerhoff, M. B. (2009). Personal and planetary well-being: Mindfulness meditation, pro-environmental behavior and personal quality of life in a survey from the social justice and ecological sustainability movement. Social Indicators Research, 93(2), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9308-6. Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Bantam Books. Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion. Kaiser, F. G., & Wilson, M. (2000). Assessing people’s general ecological behavior: A cross-cultural measure. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(5), 952–978. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02505.x. Kaiser, F. G., & Wilson, M. (2004). Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(7), 1531–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.06.003. Kang, Y., Gray, J. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2014). The nondiscriminating heart: Lovingkindness meditation training decreases implicit intergroup bias. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(3), 1306–1313. https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0034150. Katzarska-Miller, I., Reysen, S., Kamble, S. V., & Vithoji, N. (2012). Cross-national differences in global citizenship: Comparison of Bulgaria, India, and the United States. Journal of Globalization Studies, 3(2), 166–183. Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009. Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Kristeller, J. L., & Johnson, T. (2005). Cultivating loving kindness: A two-stage model of the effects of meditation on empathy, compassion, and altruism. Zygon, 40(2), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9744.2005.00671.x. Leary, M. R., Tipsord, J. M., & Tate, E. B. (2008). Allo-inclusive identity: Incorporating the social and natural worlds into one's sense of self. In H. A. Wayment, & J. J. Bauer (Eds.). Transcending self-interest: Psychological explorations of the quiet ego (pp. 137– 147). Washington: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 11771-013. Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Choi, J., & Zachariassen, K. (2015). Connectedness to nature and to humanity: Their association and personality correlates. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1003), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01003. Leiberg, S., Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2011). Short-term compassion training increases prosocial behavior in a newly developed prosocial game. PLoS One, 6(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017798. Leiner, D. J. (2019). SoSci Survey (Version 3.1.06) [Computer software]. Available at https://www.soscisurvey.de. Leung, A. K.-Y., Koh, K., & Tam, K.-P. (2015). Being environmentally responsible: Cosmopolitan orientation predicts pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.05.011. Loy, L. S. (2018). Communicating climate change. How proximising climate change and global identity predict engagement (Dissertation). Stuttgart: Universität Hohenheim. Luberto, C. M., Shinday, N., Song, R., Philpotts, L. L., Park, E. R., Fricchione, G. L., et al. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of meditation on empathy, compassion, and prosocial behaviors. Mindfulness, 9(3), 708–724. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12671-017-0841-8. Mannschatz, M., & Baur, A. (2018). Buddhas Herzmeditation: Mit Achtsamkeit zu Selbstliebe und Mitgefühl. München: Knaur MensSana Taschenbuch. Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY US: Harper & Row. Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.10.001. McFarland, S., Hackett, J., Hamer, K., Katzarska‐Miller, I., Malsch, A., Reese, G., et al. (2019). Global human identification and citizenship: A review of psychological studies. Political Psychology, 40(1), 141–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12572. McFarland, S., Webb, M., & Brown, D. (2012). All humanity is my ingroup: A measure and studies of identification with all humanity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(5), 830–853. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028724. Michalak, J., Zarbock, G., Drews, M., Otto, D., Mertens, D., Ströhle, G., & Heidenreich, T. (2016). Erfassung von Achtsamkeit mit der deutschen Version des Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaires (FFMQ-D). Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie, 24(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1026/0943-8149/a000149. Mocanu, E., Mohr, C., Pouyan, N., Thuillard, S., & Dan-Glauser, E. S. (2018). Reasons, years and frequency of yoga practice: Effect on emotion response reactivity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 264. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00264. Nicol, A. A. M., & De France, K. (2018). Mindfulness: Relations with prejudice, social dominance orientation, and right-wing authoritarianism. Mindfulness, 9(6), 1916–1930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0938-8. Nilsson, H., & Kazemi, A. (2016). Reconciling and thematizing definitions of mindfulness: The big five of mindfulness. Review of General Psychology, 20(2), 183–193. https:// doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000074. Panno, A., Giacomantonio, M., Carrus, G., Maricchiolo, F., Pirchio, S., & Mannetti, L. (2017). Mindfulness, pro-environmental behavior, and belief in climate change: The mediating role of social dominance. Environment and Behavior, 5(8), 864–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517718887. Park, C. L., Riley, K. E., Bedesin, E., & Stewart, V. M. (2016). Why practice yoga? Practitioners' motivations for adopting and maintaining yoga practice. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(6), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314541314. Patel, T., & Holm, M. (2017). Practicing mindfulness as a means for enhancing workplace pro-environmental behaviors among managers. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 10(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1394819. Rau, H. K., & Williams, P. G. (2016). Dispositional mindfulness: A critical review of construct validation research. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.035. Reese, G. (2016). Common human identity and the path to global climate justice. Climatic Change, 134(4), 521–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1548-2. Reese, G., & Kohlmann, F. (2015). Feeling global, acting ethically: Global identification and fairtrade consumption. The Journal of Social Psychology, 155(2), 98–106. https:// doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2014.992850. Reese, G., Proch, J., & Cohrs, J. C. (2014). Individual differences in responses to global inequality. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 14(1), 217–238. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/asap.12032. Reese, G., Proch, J., & Finn, C. (2015). Identification with all humanity: The role of selfdefinition and self-investment. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(4), 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2102. Renger, D., & Reese, G. (2017). From equality-based respect to environmental activism: Antecedents and consequences of global identity. Political Psychology, 38(5), 867–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12382. Reysen, S., & Hackett, J. (2016). Further examination of the factor structure and validity of the Identification with all Humanity Scale. Current Psychology, 35(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9341-y. Reysen, S., & Katzarska-Miller, I. (2013). A model of global citizenship: Antecedents and outcomes. International Journal of Psychology, 48(5), 858–870. https://doi.org/10. 1080/00207594.2012.701749. Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T. M., Galetti, M., Alamgir, M., Crist, E., et al. (2017). World scientists' warning to humanity: A second notice. BioScience, 67(12), 1026–1028. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix125. Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, A., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E. F., & Foley, J. A. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461(7263), 472–475. https:// doi.org/10.1038/461472a. Römpke, A.-K., Fritsche, I., & Reese, G. (2019). Get together, feel together, act together: 10 Journal of Environmental Psychology 66 (2019) 101340 L.S. Loy and G. Reese International personal contact increases identification with humanity and global collective action. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology, 3(1), 35–48. https://doi. org/10.1002/jts5.34. Rosenmann, A., Reese, G., & Cameron, J. E. (2016). Social identities in a globalized world: Challenges and opportunities for collective action. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(2), 202–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615621272. Running, K. (2013). World citizenship and concern for global warming: Building the case for a strong international civil society. Social Forces, 92(1), 377–399. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/sf/sot077. Salzberg, S. (2002). Lovingkindness: The revolutionary art of happiness. Shambhala classics. Boston: Shambhala. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/ fy0661/2002070629-b.html. Schindler, S., Pfattheicher, S., & Reinhard, M.-A. (2019). Potential negative consequences of mindfulness in the moral domain. European Journal of Social Psychology. Advance online publicationhttps://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2570. Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2018). Mindfulness and connectedness to nature: A metaanalytic investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 10–14. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.034. Sedlmeier, P., Eberth, J., Schwarz, M., Zimmermann, D., Haarig, F., Jaeger, S., et al. (2012). The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1139–1171. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028168. Singer, T., & Bolz, M. (Eds.). (2013). Compassion: Bridging practice and science. Munich, Germany: Max Planck Society. Stanley, S. K., Wilson, M. S., & Milfont, T. L. (2017). Exploring short-term longitudinal effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on environmentalism. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 174–177. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.059. Stanszus, L., Fischer, D., Böhme, T., Frank, P., Fritzsche, J., Geiger, S. M., & Schrader, U. (2017). Education for sustainable consumption through mindfulness training: Development of a consumption-specific intervention. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 19(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2017-0001. Statista (2017). Wie oft nehmen Sie sich Zeit zur inneren Einkehr, zur Meditation oder etwas ähnlichem? Retrieved from https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/274795/ umfrage/haeufigkeit-von-meditation/. Statista (2018). Number of people doing yoga in the United States from 2008 to 2017. (in millions). Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/191625/participantsin-yoga-in-the-us-since-2008/. Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00175. Tobler, C., Visschers, V. H. M., & Siegrist, M. (2012). Addressing climate change: Determinants of consumers' willingness to act and to support policy measures. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(3), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012. 02.001. Trautwein, F.-M. (2018). Dezentralisierung des Selbst? Neurowissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse über die Wirksamkeit von Achtsamkeitsmeditation und deren Einfluss auf Identität und Sozialverhalten. In H. Stark, & C. Pfisterer (Eds.). BfN Skripten: Vol. 508. Naturbewusstsein und Identität. Die Rolle von Selbstkonzepten und sozialen Identitäten und ihre Entwicklungspotenziale für Natur- und Umweltschutz (pp. 64–78). Freiburg i. Br.: Bundesamt für Naturschutz. Trautwein, F.-M., Naranjo, J. R., & Schmidt, S. (2014). Meditation effects in the social domain: Self-other connectedness as a general mechanism? In H. Walach, & S. Schmidt (Eds.). Studies in neuroscience, consciousness and spirituality: Vol. 2. Meditation neuroscientific approaches and philosophical implications (pp. 175–198). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01634-4_10. Trautwein, F.-M., Naranjo, J. R., & Schmidt, S. (2016). Decentering the self? Reduced bias in self- vs. other-related processing in long-term practitioners of loving-kindness meditation. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(1785), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg. 2016.01785. Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Cambridge, MA, US: Basil Blackwell. Van Dam, N. T., van Vugt, M. K., Vago, D. R., Schmalzl, L., Saron, C. D., Olendzki, A., & Meyer, D. E. (2018). Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617709589. Virgili, M. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions reduce psychological distress in working adults: A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Mindfulness, 6(2), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0264-0. Visted, E., Vøllestad, J., Nielsen, M. B., & Nielsen, G. H. (2015). The impact of groupbased mindfulness training on self-reported mindfulness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 6(3), 501–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-0140283-5. Wallmark, E., Safarzadeh, K., Daukantaitė, D., & Maddux, R. E. (2013). Promoting altruism through meditation: An 8-week randomized controlled pilot study. Mindfulness, 4(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0115-4. 11