Caribbean Voodoo: Racial Resistance & Religious Expression

advertisement

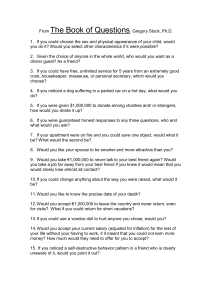

SociologicalAnalysis, 1977, 38, 1:25-36 Caribbean Religion- The Voodoo Case Roland Pierre st. Teresa Church (Brooklyn) The components of Voodoo in the religion of the Antilles are explored in their religious dimensions. The Voodoo religion appears to be the expre~sion of the racial and cultural resistance of ah oppressed class of people within a hostile societ~. There is absolutely no h u m a n group which does not react to the changes, disturbing events and crises which the dynamics of history introduce into the physical or cultural context to which the group belongs. Any quick change, any internal of external conflict whatever, produces a crisis. To each crisis, society responds by slowly developing new forros and new means to bring about balance within the limits of the particular cultural group. Sometimes the crises and wounds are so serious that they threaten the very existence of the group. Their whole existence seems to be on the line. In sucia a case, the most secret and active forces in their whole culture ate mobilized so as to develop adequate means for their liberation. These means are theforces of religious life. C a r i b b e a n V o o d o o is the clearest p r o o f o f this! But h e r e a w o r d o f w a r n i n g is necessary. PoliticaI a n d ideological c o n s i d e r a t i o n s h a v e given rise to m a n y illf o u n d e d c o n s i d e r a t i o n s c o n c e r n i n g the n a t u r e o f C a r i b b e a n Voodoo. For m a n y f o r e i g n e r s , it is c o n v e n i e n t to see in it "a mess o f N e g r o s u p e r s t i t i o n s ! " M o r e o v e r , 1The West Indies named after the mistake of Christopher Columbus who believed he had boarded the Indies. The Greater Antilles are Cuba, Haiti, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico. The Lesser Antilles are Guadeloupe, Martinique, Trinidad, Curacao and Aruba. 2The traditional school system that prevails today functions as ah instrument of integration to the dominant ideology of the society. The fact is widely demonstrated by some modern thinkers, among others, Paulo Freire, who views the present school system as a tool of domestication of the popular classes by the elite. 25 Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 T h e p r o b l e m r a i s e d in these pages is o n e o f i n v e s t i g a t i n g , d e s c r i b i n g a n d e v a l u a t i n g o n e o f the most i m p o r t a n t realities in the C a r i b b e a n : the Religion o f the Antilles. ~ W h i l e a n i m p o r t a n t question, it is also a delicate q u e s t i o n w h e n the religious p h e n o m e n o n is at the same time a c u l t u r a l p h e n o m e n o n . So it b e c o m e s clear at once that the e x a m i n a t i o n o f this reality will not be easy e v e n f o r a C a r i b b e a n p e r s o n t r y i n g to d e s c r i b e s o m e t h i n g w h i c h is, n e v e r t h e l e s s , very m u c h a p r o d u c t o f bis own e n v i r o n m e n t . For the i n t e r p r e t a t i o n h e r e contradicts the " W e s t e r n " line o f t h o u g h t which, h o w e v e r , does h a v e a certain effect o n a n y black m a n who has b e e n t h r o u g h the W e s t e r n school-system. 2 G e o r g e s B a l a n d i e r (1955) has d e m o n s t r a t e d in a very c o n v i n c i n g f a s h i o n that w h e r e v e r political e x p r e s s i o n is c o m p l e t e l y s u p p r e s s e d , the p r e s s u r e w i t h i n the o p p r e s s e d p e o p l e will always c o m e out in t h e i r religious e x p r e s s i o n . Vittorio L a n t e r n a r i (1962:109) b r i n g s out the s a m e point: 26 SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS The Phenomenology of Voodoo Since Voodoo is a religion without writings, there are no official texts. O u r study will have to be like the work of an artist trying to rediscover the context of the Voodoo which underlies its cuhic practices. Actually, this cuh carne to us in the Antilles from the Black Continent by means of forced slavery. Ir is known that, beginning in 1503, the Portuguese began selling the first Africans to the Spanish for the reines of Hispaniola. In 1510, Pope Nicholas V would give them his blessing as they undertook this "work of civilization and Christian faith." About 1555, the English began trading. In 1612, the Dutch get involved and, about 1665, the French in their turn begin setting up their counters. During the time of colonization, the tribal chiefs on the Western coast of Africa became real bell-hops for the slave traders. Those in charge of kidnapping and razzia took not only men but even the women and children because these last ones were particularly sought after by certain planters since they cost less on the open market. T h e victims were raided from Senegal to Angola. But the "Slave Coast" was a mosaic of many different peoples. According to A. Labat (1722), the Caribbean slaves came from Senegal, GamaA proof of that is found in the "Campagne anti-superstitieuse" (anti-superstituous campaign) led in 1943 by both the French Clergy and the Haitian Government. Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 it should be mentioned that about 10% of the Haitians only use the word to designate a p h e n o m e n o n of which they disapprove (cf. Peters, 1941, 1956, 1960; Bijou, 1963), while the majority of the Haitian people cherish ir as ah object of their love and strong fervor. Those who dare to touch on this point with any hostility will unloose on the part of the majority the most violent reactions possible. 3 An explanation can be found in the colonial mentality, shared by both the colonist and the alienated colonized people, according to which everything which was not Western was dismissed with the contemptuous label: barbarian; whereas the p h e n o m e n o n so c o n d e m n e d was often fulfilling within the context in which it was produced ah extremely useful function. O u r purpose here, then, is to approach the Religion of the Antilles without any theoretical prejudices. To accomplish this, our first step will be to reconstruct the object of our observation: the cultural p h e n o m e n o n of Voodoo, while keeping our distance from the traditional exegesis which is usually biased. At the same time we will attempt to go beyond mere description. We are undertaking a true reconstruction, because the perspective which the researcher adopts in his observation ofa p h e n o m e n o n plays a considerable role in the make-up of the p h e n o m e n o n itself. Isn't it a principle of m o d e r n science that "it is the scale which creates the p h e n o m e n o n " (cf. Pinto, 1967: 304). Too often in the past Voodo has been understood in categories which were inappropriate to it and hence deformed it. Above all, we must "decolonialize" certain interpretations. Voodoo, here, will be treated a s a variety of and not a stage in religious behavior. We believe that this approach will help to avoid any temptation to compare Voodoo unfavorably with Christian ideas which have been imposed on the peopte of the Caribbean area. CARIBBEAN RELIGION: THE VOODOO CASE 27 Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 bia, Benin, Juda, Arda and from other places along this coast. An official document published in London in 1789 mentions that Dahomey furnished to the slave traders an annual average of 10,000 to 20,000 "pieces." Of this total number, the French exported 6 to 8,000 "heads" destined for the Antilles. About 1789, the Caribbean colony of St. Domingue had 500,000 slaves. We learn from Moreau de St. M› (1797) that they were mostly Congolese, and that can easily be understood when one recalls that theBantus were the best farmers in Black Africa. T h e r e were also Angolians. Alfred M› (1968) writes that "the growing n u m b e r of slaves coming from the counters in the Congo and in Angola has not stopped i n c r e a s i n g . . . " Many were from Togo, Nigeria, and Dahomey. Almost every West African ethnic group was represented in the French colony of St. Domingue. To avoid the i n h u m a n conditions imposed upon them, the slave engaged in "Marronnage," i.e., escape from the plantation. The "marronnage" allowed the slave to break away from everything in the terrible colonial situation which had disturbed his African way of life. Ir would now, in those hiding places, permit the outlaw to perform the complete re-Africanization of his !ife. In addition, Moreau de St. M› (1797, vol. 3:1395) notes the existence of vast zones which owe their names to runaway slaves and which were really impenetrable by whites. This is significant because it would contribute to making of "maroon" refuges into true cultural storehouses where native African values would flourish. But who are these "Maroous" and what kind of content would they give to Voodoo in their hiding places? Voodoo is, in fact, a concentration of various African religious expressions which, taken one by one, only a p p e a r as modulations--according to local particularities and experiences--of the same basic substratum. M› (1958:15) observes that "Voodoo is a religion practiced by autonomous confraternities of which each one often has its own style and traditions." T h e fact is that even though the affinity of great cultural traits from Africa caused ajoining in all that would be essential, it did not cause the various cultic nuances to be leveled nor was the originality of each group's conceptions rubbed out. What h a p p e n e d was that many factors came together to f o r m a common vision. One of the strongest influences in Voodoo was that of the Congolese because, being in the majority, they "would also easily take off for the hidden maroon colonies" (St. M› 1797, vol. 2: 212). It can, then, be supposed that a strong crystallization of Congolese customs appeared in the maroon communities even if, in the last analysis, we must minimize this p h e n o m e n o n and see it in combination with others. Ethnologists have discovered in the Voodoo hagiography a whole long list of Congolese divinities. They are divided into Congo Bbdm} and Congo Savan-n, also called Zandb. T h e latter group is divided into "families" of which the principal ones would be theKanga, theKaplaou, theBoumba, theMondongues and theKita. In addition, there also exist the CongoFran, the CongoMazon-n and the CongoMoussai (M› 1958:76; Bastide, 1967:118; Peters, 1941). These last divinities would preside over sorcery (M› 1958:164; Denis, 1944; Courlander, 1960). T h e term "Zombi," which refers to the living-dead, victims of the work of the b6k6 (Bastide, 1967:117), is of Congolese origin. Furthermore, folkloric dances, di- 28 SOCIOLOGICALANALYSIS 4St. Patrick stands for Danbala; St. Peter stands for Legba; St. Ann stands for Ezili; St. James stands for Ogoun; St. Expedit stands for Agou› (cf. Salgado, 1963:31; Price-Mars, 1954:180-182). Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 vided into CongoMazon-n, CongoPay~t, CongoFran and CongoPastor~lwitness to the good h u m o r of this ethnic group and to their very advanced musical knowledge. On the other hand, the god Wangbl and the god Lemba, god of regeneration in Angola, witness to the important Bantu influence in Voodoo. It must be said at once that the Bantu religions were not based on "systems" as well organized as those of the Sudanic and Guinean religions. T h e basis of the Bantu religion was ancestor worship. T h e social structure and life on the plantations disturbed their expression of faith. Once this base was destroyed, only a certain Animism survived which served to distinguish the Bantus from the Fons and the Yorubas who professed a more systematic mythology. Voodoo also gained a great deal from these last two groups: For example, the Fon influence gave Voodoo the following vocabulary: a "vodou-n" is a god, a spirit; a "houn-si" is the servant of a god; a "houn-gan" is the priest of a god; T h e accessories for the cuh in Haiti still bear names of Dahomean origin: govi= pitcher; zin= pot; ason= a sacred shaker; h o u n - t £ a drum; h o u n g n 6 = a god's child. T h e major divinities in the Voodoo pantheon are found among the Fons and the Yorubas: Legba, Dambala-Ou~do, Aida-Ou~do, H›233 Agassou, Ezili, Agou› Taroyo, Zaka, Ogoun, Chango still have their temples in the towns and villages of Togoland, Dahomey and Nigeria. T h e Fons succeeded in imposing their ritual cadre on Voodoo more than the other groups did. This preponderance is due, for one thing, to the Dahomean "will to have power" and, for another, to the n u m b e r of qualified people and exiled priests from Dahomey who were deported as slaves to the Antilles (Labat: 1722:38-40). Thus, they were able to impose their religious domination on the other ethnic groups. Briefly, while the Congolese religion is based on a cult of the dead, the Yoruba religion is centered on the Monotheism of Olorun (Supreme God) and the Polytheism of the Orisha (Heroes or national sovereigns deified), the Fon religion is based on Divinities and ritual possessions (Bastide, 1960:82-83). T h e funeral rites also come from the Ibo in the forro of the Kas› and the religious dances. Therefore, one can better understand the multiplicity ofinfluences which Dahomean religious architecture had to recast so as to transform them into a coherent system capable of producing a complete and understandable meaning. T h u s the Haitian Voodoo is the product of ah intense integration, u n d e r the influence of Dahomean ideas, of the religious conceptions brought to America by Bantus (Congolese and Angolians) and Sudanese of the Manding groups (Bambara, Diola, Soninke), as well as of Achanti, Ewe, Haoussa and Peuhls (of the Kamitic race), Ouoloffs, Fons and Yorubas (Caseneuve, 1967:61-68; Romain, 1958:110). Now, a certain catholic appearance of the Voodoo has often been denounced so as to deny to this cult any true religiosity and to disqualify it asa sort of d e f o r m e d Catholicism, a "mixture." A s a matter of fact, this syncretism can be observed on three levels: a) that of the pantheon4; b) that of the liturgical calendar (M› C A R I B B E A N RELIGION: T H E V O O D O O CASE 29 Voodoo and the Nature of the Soul For the Voodoo believer, conception is n o t a biological p h e n o m e n o n nor is the appearance of a new baby a purely social happening. It is a religious event made up of ritual prophylaxis designed to protect the future mother and the fetus as well as a subsequent thanksgiving for a happy delivery. Giving birth to twins is considered a matter of considerable importance and one which involves a very strong divine mission. Twins who have been ascribed a special ancestry will be venerated even while they are alive. In the Voodoo context, the name is very important. Ir is the name which regulates the spiritual condition of the person. It is so m u c h a part of his m a k e u p that "it should not be divulged." Otherwise, the bearer of the name is exposed to evil spirits. It is the name which situates, according to Voodoo belief, the very essential of the person: theGrobon-nanj, whose power can be reinforced by the rite of the "Lav› and who can be taken away from the attacks of a wicked supernatural being by the rite of the "Po-tkt." This Grobon-nanj is a kind of orchestral component which presides at the same time over the spiritual life and the organic life (a fact which led some to say that each person had two souls). In fact, it is mobile and detachable from the body in the sense that it can wander at night, r u n n i n g the risk of being captured by evil powers and causing the death of the living person to whom it would not be able to return. It returns to the Gran-M~t 5"The sacraments of the church such as Baptism, Eucharist . . . are re-thought in ah African perspective. T h e i r function henceforth is going to be that ofincreasing the vital force, heal the diseases and strengthen the head, dwelling of the personality and the god" (cf. Bastide, 1968:185). ~"Every religious activity develops on a certain set space and is inserted into a calendar which rhythms its life. Slavery had forced African people to divorce their religious expression from its natural geographical framework and e n v i r o n m e n t to adjust it to a new setting, another calendar, that of their western white masters. From those forced adjustments s t e m m e d the first forms of syncretism. What features the spatial.syncretism is the fact that the material spread out in the space is comprised of solid objects that cannot be put out of shape and therefore, the syncretism in the case cannot be a fusion, h just remains as coexistence of dissimilar objects" (cf. Bastide, 1968:160). 7Pouring forth ah African idea into a western envelope is not a synthesis which is defined as ah assembling of different parts into a new form o r a complex whole resulting from this. As an example: when the Voodooists make believe they are celebrating Christmas they are in fact celebrating the Voodoo liturgical New Year which is--according to t h e m - - t h e period of best quality of the Mana (cf. Bastide, 1968a: 160; 1954b: 77-81; M› 1958:216). SAn amalgam would be a mixture of two or many religious beliefs opposed to one another (cf. Luzbetak, 1968). Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 1958: 292); c) that of the sacramentary cult. 5 But this "civil" syncretism is not in any way a fusion, 6 n o r a synthesis ` nor an amalgam, 8 but only a white mask put on over black skin. T h e Voodoo has kept its religious originality in spite of the catholic cloak which circumstances have obliged it to raise in front of its cultural face and in spite of the Christian ingredients which it uses, by reinterpreting them, so as to reinforce its magical effectieness. In the Antilles, the policy of the masters was to force their slaves to give up their culture (language, work methods, religion) and to assimilate a new one; the only possible reaction was to reject or to reinterpret the culture forced on them. This is what gives the Voodoo its aspect of a religion of deportees which, therefore, could only be a religion of protest and social redemption. 30 SOCIOLOGICALANALYSIS after death; this is why the Voodooists get rid of the soul by the funeral ceremony (M› 1958:226) which they celebrate one-year-and-one day after the death of the initiate whose soul resides, until then, in an earthenwarejar or at the bottom of a river in a cold, unattractive world. It was, nevertheless, the Grobon-nanj which gave the body its meaning. As long as the body is alive, it is never ala object. It enters into a substantial unity with the soul to become the space f o r a mys6c geograph~. In this view, the liver and blood become /ife's point of condensation. The god enters and leaves people via the fbntanels. "The teeth, saliva, sweat, nails, hair represent the entire person" (Mauss, 1968:57). T h e feet gather up the force of the earth which is the conservatory of the Ancestors. T h e Grobon-nanj assumes two functions: 1) that of"vital principle." Indeed, if it leaves the body once and for all and goes back to God, the individual's death can be expected. This situation recalls the close parallel that could be made between the role of the Caribbean Grobon-nanj and that of the Yoruban Ori (Bastide, 1967:218); 2) that of a more "subtle soul." It can, during sleep, leave the body which still remains alive. It can be inferred from this belief that the "vital principle" is, then, always there to keep the sleeper alive while he breathes and moves unconsciously. That the Voodooist introduces the idea of the detachability of the Grobon-nanj is a sign of the independence of this element and of its spiritual freedom since it can use the natural life of the body and, at the same time, oppose it even if, in concrete fact, there be no barrier between the body and this principle. Besides, each person also possesses a Tibon-nanj who is the tutelary god of the individual, also calted his Mbt-tbt, a limited supernatural being (cE M› 1958:139) whose servant honors hito at theRogatoua: the personal altar he erects in his room. This guiding loua could have been chosen by the bearer's parents sometimes before his birth. T h e god can also, spontaneously, in a dream or by the intermedŸ of one of his supporters (his possessed), manifest his desire to take the child under his protection. But the child remains free, when he reaches an adult age, to renounce his patron and adopt another. Such an action concerns only the renouncer and the god. It shows religion u n d e r its most personal cultic aspect (Romain, 1958:169). A funeral rite practiced after physical death, the D&ounin, is supposed to cut away any attachment between the dead person and the loua-protector, who must be transferred to the head o Ÿ living searcher u n d e r penalty ofvindication by the gods (Romain, 1958:208-9). Many would argue this is a naive and prescientific rationalization of not-yet-understood phenomena manifesting the interior life of man. This does not take away from the fact that through these coarse concepts there ate revealed some profound and accurate intuitions corresponding to two major experiences in the life of the Voodooist: 1) that man is more than his body (the whole biology of the Grobon-nanj) and, 2) that man is essentially bound to a transcendent world on which he depends for his entire existence: the Gran-Mbt, the Loua, with whom he enters into familiarity by the Kanzo of initiation. ofBoul› It must be noted, first of all, that the Voodoo Religion is, above all, an "experience." To an observer alien to the Black Weltanschauung, this practice apparently Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 S emantization CARIBBEAN RELIGION: THE VOODOO CASE 31 Legba Without going into a tiresome exploration ofall the details, we will examine one major institution relevant enough to be considered a s a key which leads to the u n d e r s t a n d i n g of Voodoo: the loua LEGBA. It should be stated that the LOUAS appear as visible forces of the Gran-M6t, supreme creator, but are situated on a level inferior to his. They e n j o y a more profound awareness than man (Kon› M› 1958:310-317). They protect h u m a n s and help them to avoid d a n g e r (M› 1958:219), they incarnate themselves in their servants by coming to them from Nan Ginin, the Voodoo Olympus. They are addressed prayers and offered sacrifices, have space and time which are consecrated to them and can either punish or reward. T h e y can decide on the duration of h u m a n life and are called "papa" in virtue of the filial feeling they inspire. In short, they are considered in their functions as delegates of the supernatural power between the Gran-M› and Man. However, one of them seems to have a very special role and to take precedence of the others and this is LEGBA. Presentat any spot of influence, he is the object o f a myth which says that the supreme God has made hito the Universal interpreter. As guardian of houses, his symbols ate found everywhere. They are the sacred plants in the courtvards. They are the small earthern hillocks topped by a phallic sign in front of the houses. They are the blue cross traced with indigo on doors. In the cuh, Legba fulfills a primordial function: Only He can translate into human language the messages of the gods and express their will (M› 1958:319). Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 carries nothing really meaningful and involves more bodily aspects of the man than his brain. According to Gusdorf (1953:16), mythical thought is a thought lived before it is intellectually developed and formulated. Ir is a spontaneous way-of-being-inthe-world, a way of c o m p r e h e n d i n g things, beings and oneself, and one's conducts and attitudes, a way of inserting man into reality. Nevertheless, when a voodooist drags a bird across the body of a patient in o r d e r to transfer to the animal the sickness which he wants to take away from that person, he is acting according to a theory. Even in the hypothesis which says that the single believer is not capable of explaining what he is doing as a ritual, it is still true that he undertakes the action in view of a resuh which presupposes some meaning. From this can be discovered in the Voodoo context two fundamental forros of Knowledge: 1) T h e r e is, first of all, the Knowledge of the believing masses more or less elaborated according to the role and the status of the devotee. It is a concrete, immediate, pragmatic knowledge. 2) T h e Knowledge of the high initiated, instead, is given the name of"Kon› Lou" (profound science). It is not unusual to h e a r a Haitian peasant declare with admiration that a person who possesses this quality is a gason-kanson, a N~g-kanbr› (morally strong man). This statement connotes a mystical power in the person so designated. It is believed that only those wise men would know exactly what they ate doing when engaged in an action which requires this justifiable explanation that comes way back from the ancient African. A s a consequence of this, support can be found for the existence of a hidden theory which is implied in even the smallest gestures. 32 SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS African logic tends toward a type of analogic reasoning which establishes connexion between the different strata of reality, permitting one to pass from one to the other while, at the same time, maintaining their unchangeable differences... The mythical structure, the mental structure, the social structure fbrin part of only one reality (Bastide, 1958:244). Therefore, "The African is induced to see the most ordinary object as part of a global system" (cf. Thomas, 1969:75). For him the Cosmos is a network of forces distributed in an unequal and dynamic way along different spots where the universal force is at work. 'From God all the way to the least grain ofsand,' writes Leopold S. Senghor, 'the African Universe is seamless' (cf. De Leusse, 1967:210). So it is this system of forces, correspondences, analogy and reflection which can help decode the mythico-ritual elements of the Voodoo. Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 He is also the god of Destiny, the one who presides at divination by means of palm nuts and shells. He is honored at the beginning of each ceremony and receives the first offerings. His liturgical colors are the fundamental colors of the NegroAfrican world (M› 1958:80). What meaning does this material convey? A first interpretation comes from the Voodoo liturgists themselves who, in a cultic chant celebrate Legba as the "opener of barriers" (M› 1958:88), or in other words, the one who makes possible the communication between heterogeneous spaces, at least between two different worlds. Indeed, all of the cultic and "extra-cultic" rites emphasize this position of Legba as myth tells it. It seems, t h e r e f o r e , that the function of this dignitary comes to that of an intermediary, and In-Between. It is also illustrated by the fact that he presides over the sexual encounter of married people. Ir is shown in the fact that children wear the "Legba shirt," a symbol which refers to the African idea that the child is the most visible connecting link between two married people. Another illustration of this point ofview is given t h r o u g h the main symbol of Legba which is indeed his "vbv6": The Legba Cross. Maya Deren (1953) convincingly establishes in her book Dieux Vivants D'Haiti that the cross of Legba is in no way indebted to any christian influence even if it is identical in form to the Roman Cross. In her opinion, the Voodoo cross is the symbol of the unity of the universe that has been entrusted to Legba's care and ministry by the Gran-Mkt. T h e vertical branch of that instrument represents the link which makes the connection between what is above and what is below. This is the route of the "invisibles." In fact, the foot ofthis vertical axis plunges into a submarine country which is considered to be the mythical paradise of the Loua who come up at the call of the living. T h e horizontal branch stands for the world of man and things. Ir is only at the cross-road of these two worlds between the divine and the h u m a n earthly axes that the encounter between the divine and the h u m a n is realized. Legba watches over this cross-road. This explains why-the offerings are made to him at the intersection of roads. T h e special significance of Legba becomes clearer if one remembers that African epistemology is a forro of knowledge in which mythical tradition furnishes both the category of thought and the models for h u m a n behaviour and social exchanges. CARIBBEAN RELIGION: THE VOODOO CASE 33 Priesthood Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 It is also revealed in a very convincing m a n n e r in the structure of the Voodoo priesthood which is divided into four priestly classes, each one in charge of one c o m p a r t m e n t of reality. 1) These are, first of all, the Divinb whose specialty is Divination. They are also called Papaloua and they occupy the first rank in the classification of the Afro-haitian priesthood. T h e Papaloua "interprets mysteries of life and brings messages from the gods" (cf. Senghor, 1946). He knows the future, explores hidden intentions, shows the meaning of the past. He takes ah individual u n d e r his care from birth to death and is consulted at the time of marriages, sickness, departure on a voyage and when someone dies. His art comes to him t h r o u g h a special initiation (the highest one in Voodoo) which is called: "La prise des yeux. Ir makes him able to scrutinize the invisible world where contrary forces are in conflict with each other. T h e most common forros of divination ate those which can be done with water, the earthenwarejar, corn, the calabash, the cartomancy and the stick with circular notches. All of this is done u n d e r the supervision of the loua Agom. During the entire divination session, the priest must smoke the Pipe o r a large cigar. It is believed that the smoke makes the word able to develop fully and to reach out to an efficiency that will last (cf. Zahan, 1963:33). For this reason one also smokes before uttering any important word, before a wish o r a blessing. 2) T h e second kind of priest in the order of importance is the B6k6 who is the great manipulator of the mystical properties of leaves and herbs. He works u n d e r the direction of the loua Loko. Concerned with the health of the group, he is a master in the art of prescribing infusions, macerations and baths required for the recovery of physical and supernatural well-being. What happens is that the "Mana" of the Loua circulates in a definite category of vegetation which must be picked "living" at certain moments and according to a set liturgy. T h e r e exists a whole list of sacred herbs which are associated with certain louas who ate supposed to dwell in them. In effect, a cultic hymn celebrates the religious herb as saving. Also a haitian myth tells how a hero who has been killed is transformed into a plant. 3) T h e third kind of priesthood is that ofS~vit~-Gh›233upon which M› has insisted a great deal. T h e Voodoo thanatology is a highly elaborated sector of thought. T h e complicated way people deal with the mortal remains, the extreme caution with which everyone prepares for his own death shows that one arrives here at the clŸ of the numinous situation about which Rudolph Otto has spoken (cf. Caseneuve, 1967:131). But if there does e x i s t a Voodoo prophylaxis against impure and dangerous supernatural powers which is the abandoning of the normal h u m a n condition, nevertheless, death is not presented a s a shipwreck in which one disappears body and all, but rather as an emergence to another life. Ir is lived in terms of ah ex-carnation. All of the practices relating to a world of beyond the tomb witness to this belief. This ministry comes u n d e r the jurisdiction of the Sbvitb-Gh›233 T h e ritual he works up is very closely associated to the Govi (the cultic pot) and to water. This is an extremely rich symbolism when one realizes that in the Negro-African thought water and the pot remind one of heaven (cf. Zahan, 1966:4). 34 SOCIOLOGICALANALYSIS Conclusion When this inquiry into the Voodoo had been initiated, we had been asking if that reality so much disparaged by so-called "civilized people" conveyed a meaning which could be profitable for the Caribbean man. T h e Voodoo appears to us first of all as a reality which is rooted in a context having many different sides to it of which the principal are the following: A) Political (the white power of the 18th century, the bourgeois power today); B) Economics (the seeking of profit yesterday as well as today on the part of a dominant minority); C) Social (class-struggle aggravated by the racial struggle in the 18th century and today a class-society which is still keeping social distances and separation); D) Psychological (during the Colonial time a reaction of rejection of the establishment on the part of the slaves and today adjustment of the masses to their situation of forgotten people); E) Cultural (ah instrument of expression of the masses, the subjected people within the broad society). In the 20th century, nothing has really changed in the human relations as they have been lived in the Antilles. T h e servile condition has simply been transposed into a proletarian condition. Voodoo has appeared to us as a religious reality. Many foreign and native missionaries yesterday as well as today have denied the religious condition of the Voodoo but without sufficiently examining ir. Nowadays a more evolved hermeneutics permits one to go beyond the appearances, to strip away the structures in order to make a better and more adequate diagnosis. Up until now the ground for the evaluation of the Black realities had come from the Western world. Today a more honest approach attempts to refer Black realities to a Black framework. It little matters what are the original forms in which the Voodooist expresses his relations to the invisible. Where there is any kind of prayer and worship, there is indeed religion. Where there is sacrifice by which contact is sought with superior spirits--principally when this element is as finely conceived as in the Voodoo cult--there is indeed religion. Where the priest is submitted to the invisible powers rather than imposing his will on them, one can, without hesitation, acknowledge that he is dealing with a religion. Voodoo satisfies fully all of those criteria. But if it is referred to as antireligious action which tries to manipulate the divine, let us state right away that this kind of magic does not belong to the Voodoo. Mauss (1966:11) points out that where Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 4) T h e fourth class of priest, that of theHoungan, constitutes the lowest form of priesthood. It puts into a privileged relationship with the Loua an initiate who has been entrusted with a specific sector supervised by a god-protector for the benefit of his devotee. T h e analysisjust made suggests to us the following conclusions: T h e Divin6 is in c h a r g e of the world of Men. T h e B£243takes charge of the world of Nature (the busb). T h e Sbvit&-Gh›233has jurisdiction in the domain of the Dead. T h e Houngan is connected with the Loua in a more general way. In this perspective in which the social is the reflection of the mystical, we can say that the four priesthoods correspond to the four compartments of the world which are completely different. But the delegate god, Legba, supervising each sector, helps to relate all the various parts in order to bring about unity and communication. CARIBBEAN RELIGION: THE VOODOO CASE 35 p r a y e r can be found, there is no place for witchcraft. T e m p e l s (1949:31) notes, in addition, that what the E u r o p e a n calls magic is for the Black m a n nothing else than the h a r n e s s i n g of the s u p e r n a t u r a l forces p u t at the disposition of m a n by God for the r e i n f o r c e m e n t of h u m a n life. D u r k h e i m along with Caseneuve gives the same idea o f religion. As for J.B. Pratt, he defines ir as attitude toward the power of powers which people conceive as having ultimate control over their interests and destinies. REFERENCES Balandier, Georges. 1955. Sociologie actuelle de l'Afrique Noire. Paris: P.U.F. Bastide, Roger. 1958. Le Candombl› de Bahia. Paris: Mouton. 1960. Les Religions Afro-bresiliennes. Paris: P.U.F. 1967. Les Am› Noires. Paris: Payot. Bijou, Legrand. 1963. Psychiatrie Simplifi› Port-au-Prince: S› Adventiste. Caseneuve, Jean. 1967. L'Ethnologie. Paris: Larousse. Courlander, Harold. 1955. The loa of Haiti: New World African deities. Havana. De Leusse, Henri. 1967. Leopold S› Senghor, L'Africain. Paris: Hatier. Denis, Lorimer. 1946. "Ethnographie afro-haitienne." Port-au-Prince: Bulletin Bureau d'Ethnologie (Dec.). Deren, Maya. 1953. The living gods of Haiti. London: Thames & Hudson. Gusdorf, Georges. 1953. Mythe et M› Paris: Flammarion. Labat, Jn. Baptiste. 1722. Voyage aux Antilles. Paris: Cavelier. Lanternari, Vittorio. 1962. Les Mouvements religieux des peuples opprim› Paris: Masp› Mauss, Marcel. 1966. Sociologie et Anthropologie. Paris: P.U.F. Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 If, then, in a psychosociological perspective, the V o o d o o religion a p p e a r s as the expression of the racial and cultural resistance of a g r o u p whose significant and vital cultural emphasis is religion, h e r e we must acknowledge the role a d j u s t m e n t plays for ah o p p r e s s e d class of people within a hostile society. But, on a m o r e theological level, its religious nucleus presents a striking coherence. T h e four d i f f e r e n t categories of priests in our inquriy suggest, in a system where social life is a reflection of a mystical thought, f o u r divisions of Reality. T h e s e ate Man, Nature, the Dead and the Gods. T h e y are in constant relationship although a certain priority of the gods, who a p p e a r as the s u p e r n a t u r a l vassals of the Gran-M› the absolute source of life, is verified. T h e r e f o r e the Voodoo cosmology shows itself as one where "the real" is completely w r a p p e d up within a s u p e r n a t u r a l network. Besides, in the V o o d o o context, h u m a n personality grows perfect when in the process of divinization. T h e intense search for g o i n g - b e y o n d the h u m a n condition has m a d e the Voodoo a Messianism and it is not surprising that it has b e e n the very root f r o m which s p r a n g up the slave revolt in 1791 which c u l m i n a t e d in the Haitian indep e n d e n c e in 1804. Voodoo today has been domesticated and commercialized. Should it h a p p e n that ir finds again a less c o m p r o m i s e d V o o d o o ctergy it will not be an o p i u m any more. Rather, it will be a help for liberation once again a n d with it, once again, "1791" may well recur. 36 SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS Downloaded from http://socrel.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sussex on September 4, 2012 M› Alfred. 1958. Le Vaudou Haitien, Paris: Gallimard. 1963. "Le Vaudou, espoir des fils d'esclaves." Ecclesia 177:105-115. Moreau de St. M› Louis-Elie. 1797. Description de la partie francaise de l'ile de St. Domingue. Paris: Maurel 1963. Peters, Edward. 1941. Lumi~re sur le houmfort. Port-au-Prince: Ch› 1956. Le Service des loas. Port-au-Prince: Telhomme. 1960. La Croix contre L'Asson. Port-au-Prince: La Phalange. Pinto, Roger. 1967. Me[hode des Sciences SociaLes. Paris: Dalloz. Romain,J.B. 1958. Quelques moeurs et coutumes des Paysans Haitiens Port-au-Prince: Imp. de l'Etat. Senghor, Leopold Sedar. 1946. "L'Esprit de la Civilisation ou les lois de la Cuhure N› Presence Africaine (Dec.). Tempels, David. 1949. La Philosophie Bantoue. Paris: Pr› Africaine. Thomas, Louis-Vincent. 1969. Les Religions d'Afrique Noire. Paris: Fayard. Zahan, Dominique. 1963. La dialectique du Verbe chez les Bambaras. Dijon: Daranti/~re. 1966. Le Feu en Afrique Noire. Strasbourg: Cours Universitaire.