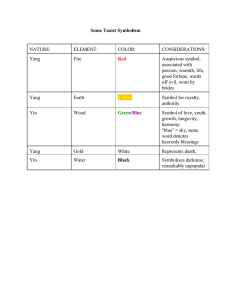

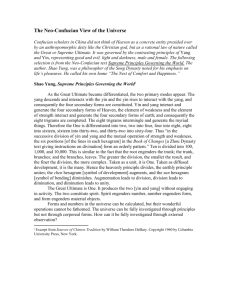

Fire Noon Summer South Metal Evening Autumn West Wood Morning Spring East Water Midnight Winter North Jue Yin Disease Wu Mei Wan (Mume Pill) defined by Arnaud Versluys The jue yin chapter of the Shang Han Lun is one of the most enigmatic in Han-dynasty clinical literature. The chapter is apparently confused and many attempts at explaining it fail in the face of the seeming disconnect between the standard description of jue yin disease in these lines1 and the formulas contained within the actual chapter. Even if one succeeds with an intellectual understanding of the chapter and its core concept of jue yin disease, most practitioners still fail to gain a visceral comprehension of the identification and treatment of jue yin disease in everyday clinic. Jue yin physiology Jue yin jing ( ) is the jue yin conform­ ation of the wind wood of the east. Its branches (biao ) on the body’s periphery are the foot jue yin Liver and hand jue yin Pericardium channels, while its root (ben2 ) is wind. Contained within jue yin is the middle qi (zhong qi3 ) of the shao yang 28 Vol 5–3 ministerial fire (xiang huo4 ). Jue yin is the unity of wind and ministerial fire. It is the fanning force behind the circulation of ministerial fire in the hollow yang realm, as well as the warm rising of blood within the solid yin realm in the body. Jue yin contains and steers blood, which it spreads freely in all four directions: up, down, in and out. The driving force behind this distribution of blood is the moving warm qi contained within the blood, or in other words shao yang within jue yin. Jue yin is born from water and gives birth to fire.As such it is the bridge between water and fire and the eastern pathway through which rising water of the north communicates and connects with descending fire of the south. The yin segment of the jue yin tract belongs to the Liver, which stores and moves blood. The yang segment of the jue yin tract belongs to the Pericardium which stores the nutritive (ying/rong ) ������������������������������ which it holds closely around the Heart to provide protection and cooling to the emperor. In the separation and union (li he ) feature sequence of yin and yang, the function of jue yin is to close (he5 ) yin. Jue yin is the resolution of yin, the death of yin. As such it is the precursor to the birth of yang just as on a material level blood is the mother of qi. Yang is born from the water within the earth at the midnight (zi6 ) time as represented by the hexagram (fu )or “the recovery”7. Jue yin wood fans the birth of this initially lesser fire allowing it to increasingly warm and ascend the steaming and boiling fluids of the northern water element. The ascent of this decreasingly yin and increasingly warm water will ultimately spur the growth of shao yang Gallbladder wood and the consecutive birth of tai yang fire. Hence the Shang Han Lun says that the resolution time of jue yin, or in other words the period during which jue yin fulfills its function of resolving yin and fanning yang, happens from chou time to mao time.8 This is the end of night until the break of dawn, during which time yang rises from within the water upwards through the earth to arise from the horizon and form the yang conformations. Of all yin conformations, jue yin thus holds the most yang and the least yin, and its overall direction is upward and outward, such is the quality of its root qi wind. Jue yin pathology Jue yin and yang ming are the only exceptions to the first two rules of biao-ben-zhong qi transformation as outlined in chapter seventy-four of the Su Wen9. That is, they do not follow the first rule and transform from the root, nor do they follow the second rule and transform from either from the branch or from the root. Rather, due to the opposing yin and yang natures of jue yin’s biao and ben qi, i.e. yin branch jue yin channels and yang root wind qi, jue yin transforms from its middle qi of shao yang ministerial fire. Physiologically this means that the warming and moving qualities of the ministerial fire are exclusively responsible for the warming of the yin channels of jue yin as well as the production of wind wood internally. In pathology, this means that jue yin disease is a disease of ministerial fire, precisely ministerial fire contained within jue yin. From a functional anatomical perspective, jue yin disease manifesting either too much or too little ministerial fire always occurs from the jue yin organ within shao yang ministerial fire, i.e. the Pericardium. The second rule of biao-ben-zhongqi pathophysiology could conceivably be applied to jue yin disease, for example in relation to a peripheral jue yin channel pathology as treated by Dang Gui Si Ni Tang (Dang Gui Decoction for Frigid Extremities) or an internal jue yin wind pathology as treated by Wu Mei Wan. But even when this is the case, the expression of the pathology inevitably revolves around the Pericardium’s inability to warm the blood and the experience of cold extremities due to the lack of fire within the blood, or alternatively a reversal flow of qi striking the Pericardium, the Heart’s proxy, due to an excess of internal wind. Consequently, when ministerial fire is stirred in jue yin disease, the flaring fire can invade metal along the control cycle of the phases and either lead to suppuration and bleeding from the metal Lung as is treated with Ma Huang Sheng Ma Tang (Ephedra and Cimicifuga Decoction)10 or will invade the metal Large Intestine and create dysentery with pus and bleeding as is treated by Bai Tou Weng Tang (Pulsatilla Decoction)11. The relationship and sequence between the aforementioned throat obstruction (hou bi ) and the latter pus and blood in the stool (bian nong xue ) are evident in 12 line 334 of the original text. From the perspective of jue yin’s function of closing yin to prepare for the birth of the yang conformations through the pivot of shao yang, when jue yin closes too much, or too prematurely, yang is not born due to absence of resolution of the yin stage. This results in blood remaining too cold and too stagnant, unable to rise and float and failing to warm and nourish the extremities and the surface such as in Dang Gui Si Ni Tang. When jue yin fails to close, the upward rising of internal wind as the fanning force of the rising blood will be left uncontrolled and thus will stir excessively. This then results in the upward rising of reversal qi striking the Heart13; the fanning of disturbing fire in the Pericardium with vexing heat and pain14; vomiting or at least the inability to get food down15; and the upward crawling of restlessly moving roundworms16 disquieted n Dr Versluys joins Dan Bensky and Craig Mitchell in presenting next year’s seminar series in Australia, Core patterns of the Shang Han Lun – a clinical approach. See Page 39. n Dr Versluys is one of the very few Western scholars to have received his full medical training in China. He respectively spent more than 10 years at the Chinese medical universities of Wuhan, Beijing and Chengdu, where he consecutively pursued his Bachelor, Master and Doctorate degrees in Chinese medicine. He also trained in traditional Shanghan Lun discipleship for many years. Dr Versluys’ scholastic passion is the Han-dynasty canonical style of Chinese medicine. During the past five years, he worked as assistant professor at the School of Classical Chinese Medicine at the National College of Natural Medicine in Portland, OR, USA. He is in private practice in Portland, and teaches seminars domestically and internationally. Arnaud can be reached at info@ arnaudversluys.com. The Lantern 29 feature ‘’ As internal wind fans the flare-up of shao yang ministerial fire, it consecutively produces more hot wind. This is a perpetuating vicious cycle that requires immediate and precise treatment. by the fanning wind, all as treated with Wu Mei Wan. Jue yin reversal or counterflow is internal wind. As internal wind fans the flare-up of shao yang ministerial fire, it consecutively produces more hot wind. This is a perpetuating vicious cycle that requires immediate and precise treatment. Much can go wrong. For example, since jue yin wood relates to the functions of tai yin earth along the control cycle of the phases, when the pattern is purged with bitter herbs, jue yin will not only fail to close but its ability to close can be broken permanently. When this happens, like a closed door kicked open by force, the controlled opening function of tai yin will be damaged, and this can result in incessant downpour diarrhea.17 In the worst case scenario this can result in irreparable damage not only to tai yin but also to the shao yin pivot, such that yin perishes from below and separates from yang, leading not only to diarrhea but the incessant downpour of clear fluids and undigested food (xia li qing gu18, 19 ) typical of certain shao yin patterns. Wind Wind in nature does not exist as an independent force but is rather the natural effortless product of the interplay between opposing forces. When in one region there is a dominant cold front with low temperatures and low barometric pressure, while in another not-too-distant location there is a predominant heat front with higher temperatures and higher barometric pressure, then a current is created from the low-pressured front towards the highpressured front, or in other words from the cold locale to the hot locale. This movement in nature is called wind. It is exactly the same in the human body: all upward moving forces are the product of the temperature and pressure differential between the human body’s cold and hot fronts, i.e. the water element and the fire element. Nothing in human physiology has to do anything actively to produce wind, as it suffices to merely possess a healthy Heart in the hot south and healthy Kidneys in the colder north of the body. Wind is then created because of their opposing qualities and their relative proximity to each other. 30 Vol 5–3 A current will then move from the lower burner to the upper burner, causing qi and blood to ascend. This is exactly like the pumping mechanism of a tree, in the way that it can draw water from the ground to the tips of the leaves on its branches high in the sky. Any change, however, in this temperature differential will lead to a change in this current of upward-flowing qi. When the fire element of the south drops in temperature due to yang deficiency of the Heart, the temperature difference between Heart and Kidneys equalises and wind stills, resulting in the cold stagnation of blood failing to ascend and spread. This is a Dang Gui Si Ni Tang pattern. But when the temperature of the Kidney water drops and the temperature differential between fire and water therefore increases, then the subsequent current of upward surging wind gains pathological strength. This is the actual mechanism behind a Wu Mei Wan pattern pathology which manifests with a multitude of internal wind symptoms and reversal upward flow of qi and blood. This is the explanation of the working mechanism behind the common understanding of jue yin disease being cold below with heat on top. The functional treatment of wind wood is specified in the Huang Di Nei Jing. According to chapter 22, encouraging the dispersing movement of the Liver is fulfilled through the administration of a pungent flavour, while the reduction of such movement, in other words the stilling of Liver’s wind, is achieved through the application of a sour flavour.20 And from the six qi perspective presented in chapter 74, when wind is in the spring (which is when wind is internal) treatment is to be conducted with a sour and bitter combination.21 In even greater detail, the treatment of dominant internal wind is done through the carefully balanced administration of a sour formula of warm qi with the assistance of bitter and sweet, along with the check-and-balance of a pungent flavour.22 The mechanism of redressing deficient jue yin closure is through the sour astringing of wind directly, assisted by the bitter descent of fire and sweet tonification of earth accompanied with mild pungent dispersal to prevent excessive therapeutic closure of the circulation of qi and blood. feature The warmth of the overall formula is created by choosing a majority of warm herbs as well as through the pungent flavour of these herbs. But since too much fire can also create wind, the warmth of the formula is balanced by choosing cold-natured bitter herbs to lead physiological fire downwards and inwards. The internalisation of the physiological fire needs to be done to reestablish the physiological warming of the water specifically and the yin conformations in general. Wu Mei Wan architecture From the original text in the Shang Han Lun it is obvious that Wu Mei Wan can treat the acute proliferation of roundworm infestation23 in the human body. But every serious practitioner must have wondered at some point as to whether this prescription could not have a broader clinical application than in the field of parasitology and the occasional “long-standing diarrhea”24. Line 338 of the Shang Han Lun starts by clearly distinguishing between Roundworm Reversal (hui jue ) pattern and Visceral Reversal (zang jue ) pattern. It is made clear that Wu Mei Wan does not exclusively treat Visceral Reversal since that treatment is in the realm of shao yin disease. However, the fact that the opening part of the clause makes this distinction indicates the need to clarify and prevent this kind of confusion. This is mainly because, as the second sentence implies, Roundworm Reversal occurs on the basis of Cold Viscera (zang han )25 or cold yin organs. Cold yin organs are the condition of cold of the deepest solid yin level in the body. In the Shang Han Lun this is mentioned in one other location, namely in Tai Yin chapter’s line 277 where cold of the solid organs is to be treated with prescriptions of the Si Ni family (si ni bei Frigid ����������������������������� Extremities formulas).26 Tai yin is the ultimate yin. It contains both water and earth and is also identified in Su Wen chapter four as the Ultimate Yin (zhi yin ),27 which is even more yin than Kidney water which is identified as “just” yin within ‘’ Encouraging the dispersing movement of the Liver is fulfilled through the administration of a pungent flavour, while the reduction of such movement, in other words the stilling of Liver’s wind, is achieved through the application of a sour flavour. Chinawest Concentrated Chinese Herbs Exclusively for TCM Practitioners Are you using patent pills? Why not dispense your own herbs with your own clinic label and give your patients Chinaʼs hospital grade herbs. Over 600 leading Chinese Hospitals use our herbs. $0* Dispensary start-up! (For new graduates and established TCM practitioners) “.... my patients are VERY happy with the herbal medicine and so am I. This is the first time I have found granules similar to actual raw herbal decoctions.” LB, Sydney. *conditions apply. www.chinawest.com.au Free Call: 1800 888 198 Ask about our 10% Discount. e-mail: info@chinawest.com.au The Lantern 31 feature ‘’ Interestingly enough, wind does not exclusively move up in the body. The temperature differential exists not only along a vertical axis between Heart and Kidney, but also along an in-and-out axis between solid (yin) organs and hollow (yang) organs. 32 Vol 5–3 yin.28 As such, when: 1) yin organs are cold, 2) this visceral cold in the Shang Han Lun is considered to belong to tai yin, and 3) its treatment is performed by treating the shao yin mother of earth; then: 4) healthy wood cannot be generated by ice water inside a frozen earth, which will 5) result in the pattern called Cold Viscera, thus increasing the fire-water temperature differential, and 6) function as the foundation for Roundworm Reversal. With the northern waters freezing over, internal wind is thus engendered due to an increase in the temperature differential between north and south. And due to this temperature difference, the rising current in the body increases furiously and rushes to the relatively warmer region of the south, creating the upwards surging of wind from lower to upper burner. This surge of wind then stirs a pathological flare-up of ministerial fire in the Pericardium, as well as thrusting upward at earth and impeding the proper descent of food, thus leading to an inability to get food down. But, interestingly enough, wind does not exclusively move up in the body. The temperature differential exists not only along a vertical axis between Heart and Kidney, but also along an in-and-out axis between solid (yin) organs and hollow (yang) organs. The internal wind stirs ministerial fire which also circulates in the hollow realm of the yang conformations as qi. The solid yin organ interior is cold and the hollow exterior realm becomes hotter, thus also producing the outward movement of wind. This is treated with cold-natured bitter herbs that will drive ministerial fire inwards and downwards. So it becomes clear that the nominal concept of clearing heat with a bitter cold herb is nothing more than to drive fire inwards and downwards and submerse it within water. This is why, in Nei Jing chapter 22, a bitter flavour is considered to tonify the water element since this refers to the function of communicating fire with water by symbolically benefiting water with a fire flavour. This is echoed in the Decoction Classic (Tang Ye Jing )29 from which Zhang Zhong-Jing drew most of his formulaic knowledge and in which bitter herbs like Huang Lian (Coptis) and Huang Qin (Scutellaria) and so on are considered to be functional Kidney tonics and are listed as bitter water-category herbs.30 Zhang Zhong-Jing’s prescriptions are in large part the fruit of his lifelong study and research of all formula and prescription literature available to him. Research31,32, 33,34,35,36 has shown that the formulas for the treatment of the six conformations are to a large extent based on six pairs of prescriptions named after star constellations whose celestial movements were deemed to govern the six types of qi of this planet’s weather patterns. This is evident in remnant prescription names such as Qing Long Tang (Blue-Green Dragon Decoction ), Bai Hu Tang (White Tiger Decoction ), and Shen Wu Tang (Black (True) Warrior Decoction ). The research mentioned above shows that these prescriptions were originally listed in identical or slightly varied form in the aforementioned work named the Decoction Classic (Tang Ye Jing) written by unidentified authors in the western Han dynasty. This book was lost to the ravages of time but parts of it were preserved in Tao HongJing’s37 writings called Secret Instructions for Assisting the Body and Essential Methods for the Application of Herbs for Yang and Yin Organs (Fu Xing Jue Zang Fu Yong Yao Fa Yao )38 retrieved in the 1930s from the Dun Huang caves in Northwest China. In this book, the authors list a table of 25 herbs outlined along a five phase-five flavours grid. Of these categories, the wood category of herbs is a collection of pungent herbs to stir wind with the objective of reviving fire through the functional tonification of its wood mother. The herbs in this category then each have an elemental affinity through their respective signatures conditioned by their natural appearance in the phenomenal world. The five herbs of the wood class are: Gui Zhi (Cinnamomi Ramulus) as the wood herb of the wood class and the governor of the category through its woody branch-like signature; Shu Jiao or Chuan Jiao (Zanthoxyli Pericarpium) is the most spicy fire herb of the wood class linked with the Heart through its hollow, chamber-like shape and red color; Jiang, ginger, both raw and dried, is the earth herb of the wood class because of its yellow colour and earth feature warming action; Xi Xin (Asari Herba) is the metal herb of the wood class with its Lung affinity conditioned by its leaves; and Fu Zi (Aconiti Radix Lateralis Preparata) is the water herb of the wood class, pungent hot to warm the Kidneys through its black colour of the water element. These five herbs are the core herbs to warm Wu Mei Wan and provide the necessary pungency to balance the strong dominant sour and bitter flavours. Since in Wu Mei Wan all five solid organs of the yin conformations are cold as established in the aforementioned line 338 of the Shang Han Lun, these five herbs warm the five solid organs, one each. And then finally the formula contains sweet herbs in compliance with Nei Jing chapter 22 instructions on flavour architecture to moderate the Liver39 and nourish earth40. Dang Gui (Angelicae Sinensis Radix) is the core jue yin blood nourishing and wood urgency moderating herb, while Ren Shen (Ginseng) is the sweet earth herb of the herb class41 to replenish nutritive qi within the tai yin conformation. Expanded clinical use of Wu Mei Wan The Shang Han Lun indicates the use of Wu Mei Wan for the treatment of visceral cold resulting in Roundworm Reversal. It also mentions its applicability in the treatment of chronic diarrhoea (the latter indication being unverifiable as to whether this was added during the later editions of the Shang Han Lun by other authors). But in clinic, once the mechanism of jue yin disease and the treatment of wind is understood properly, the application of Wu Mei Wan can be opened up to a larger variety of disorders. A quick glance at recent research literature from China reveals articles pertaining to the use of Wu Mei Wan in the treatment of the following selection of illnesses, to name but a few: roundworm infection42, chronic cholecystitis43, chronic diarrhoea44, chronic asthma45, diabetic gastroparesis46, chronic atrophic gastritis47,48, chronic renal failure49, chronic colitis50, ulcerative colitis51,52,53, angina54, urticaria55, menorrhagia56, etc. Following are three anecdotal case histories from personal practice illustrating the use of Wu Mei Wan in greatly differing conditions. Case 1: Interstitial cystitis and idiopathic vertigo A female patient, 55, presented with severe lower abdominal pain and urinary frequency. The pain was strongly contracting. Urinary frequency was about once every half hour during daytime and up to 10 times at night. The urine was clear. She also suffered from insomnia with some difficulty falling asleep and frequent waking. Furthermore, she had an idiopathic “vestibular disturbance” causing severe bouts of vertigo. The vertigo could be severe at times causing loss of balance and falling over. Accompanying the vertigo was a sense of vibration in the thoracic and cervical spine contributing to the restlessness and insomnia at night. Lastly, the patient suffered from heartburn due to acid reflux, often feeling a sense of pressure on the stomach. Pulses overall were weak. There was a wiry and slightly hollow quality on the left guan (medial pulse), along with a deep cun (distal pulse) and deep but slightly tight chi (proximal pulse). The right hand pulses were thin wiry at guan with a deeper cun and thin wiry deeper chi position. The diagnosis was jue yin disease with visceral reversal: zang jue. The prescription was Wu Mei Wan with Zhen Wu Tang (True Warrior Decoction) incorporated as modification. Ban Xia (Pinellia) was added to introduce the core structure of Ban Xia Xie Xin Tang to drain the epigastrium, treat reflux and promote sleep. Wu Mei Huang Lian Huang Qin Gui Zhi Chuan Jiao Xi Xin Fu Zi Gan Jiang Ren Shen Ban Xia Dang Gui Bai Shao Bai Zhu Fu Ling 48g 3g 9g 3g 1g 3g 15g 9g 3g 12g 3g 9g 9g 9g ‘’ The wood category of herbs is a collection of pungent herbs to stir wind with the objective of reviving fire through the functional tonification of its wood mother. Mume Fructus Coptidis Rhizoma Scutellariae Radix Cinnamomi Ramulus Zanthoxyli Pericarpium Asari Herba Aconiti Radix Lateralis Prep. Zingiberis Rhizoma Ginseng Radix Pinelliae Rhizoma Prep. Angelicae Sinensis Radix Paeoniae Radix Alba Atractylodis Macrocephalae Poria The patient returned after one week and had experienced great improvement. The The Lantern 33 feature ‘’ In clinic, once the mechanism of jue yin disease and the treatment of wind is understood properly, the application of Wu Mei Wan can be opened up to a larger variety of disorders. 34 Vol 5–3 abdominal pain was all but gone. Urination had reduced to about five or six times per day; nocturia was still four to five times per night. The dizziness was slightly better. The vibrations in the spine were slightly better. The insomnia had improved, although the patient still used sleeping medication. The heartburn had recently flared up with some increased pressure in the chest but this might have been due to diet. The pulse showed overall similar qualities with slight less hollow left guan, though wiriness was now more emphasised. The same prescription was dispensed. On the next visit, the patient reported no more abdominal pain. Urination during the day had normalised. Night-time urination varied between two and four times per night. The daytime loss of balance was less noticeable. Night-time vibrations in the spine still persisted but had also improved. Insomnia was on and off. Some nights she slept well, even without medication. Other nights she needed her medication. The problem now was mostly with falling asleep. The pulses were overall less excessive and softer though the main trend was still the same. The actual shao yin conformation quality of faintness and depth was starting to appear more prominently. The patient was advised to continue taking this prescription. After a period of about two more months, the improvements had mostly stabilised. The stomach was now completely normal. Now the main problem was clearly the dizziness, poor balance and occasional insomnia. Pulses showed an overall deep thin wiry left guan. Left cun was deep and weak. Left chi was deep and slightly tight. All pulses were weak. Right hand cun was deep weak, guan was thin wiry and chi was deep weak and slightly tight. Left guan was weaker than right guan. Wu Mei Wan was continued for another few months with increased emphasis on Zhen Wu Tang and Fu Zi (Aconiti Radix Lateralis Preparata) in particular through its increased dosage to 30 grams. After the use of Wu Mei Wan was halted, the treatment then carried on with variations of Zhen Wu Tang, sometimes combined with Dang Gui Shao Yao San (Dang Gui and Peony Powder). The patient is still under continued care. The urinary bladder flares less than once a year. Case 2: Hypertension and diabetes A male patient, 65, presented with chronic hypertension unresponsive to treatment. He was diabetic and suffered mild druginduced kidney function impairment as evident in blood tests. Hypertension was diagnosed 20 years ago, while the diagnosis of diabetes was made 10 years previously. Average blood pressure was 180/95 mmHg with spikes of up to 250/140 mmHg. The patient was taking multiple medications for hypertension such as Benicar 20 mg qd (Olmesartan Medoxomil, ACE inhibitor), Corec 20 mg qd (Carvedilol Phosphate, beta-blocker) and Aldectone 75 mg qd (Spiro­nolactone, aldosterone antagonist), but all to limited or no avail. Currently the patient was trying to manage his diabetes with proper diet but glucose levels hovered around 300 mg/100ml fasting. He had seen an unrelenting increase in both blood pressure and blood glucose in the past six months. The patient suffered asymptomatic brachycardia and arrhythmia of which he was mostly unaware but discovered when he saw a cardiologist for his fatigue and shortness of breath. However, further findings were inconclusive. The patient urinated three to five times per night; urine colour was generally clear. Pulses showed a deep left cun, with tight wiry and somewhat hollow left guan, and a deep tight left chi. Right hand pulses showed a deep tight cun, with a deep thin and wiry tight guan, and a deep chi position. Diagnosis was jue yin disease with visceral reversal: zang jue. The prescription was Wu Mei Wan plus Zhen Wu Tang to address Kidney water metabolism. Wu Mei Huang Lian Huang Bai Gui Zhi Chuan Jiao Gan Jiang Xi Xin Fu Zi Ren Shen Dang Gui Bai Shao Bai Zhu Fu Ling 48g 6g 3g 6g 1g 3g 3g 6g 3g 3g 6g 6g 12g Mume Fructus Coptidis Rhizoma Phellodendri Cortex Cinnamomi Ramulus Zanthoxyli Pericarpium Zingiberis Rhizoma Asari Herba Aconiti Radix Lateralis Prep. Ginseng Radix Angelicae Sinensis Radix Paeoniae Radix Alba Atractylodis Macrocephalae Poria feature The patient returned after one week and reported a steady decline in blood pressure readings to an average of 160/90 mmHg with occasional drops as low as 145/85 mmHg. Blood glucose averaged 180 mg/100 ml about three hours after his meals. His nocturia had decreased to once or twice per night. The left pulse showed a deep cun failing to rise, along with a deep wiry tight guan, and a deep tight chi. Right pulses displayed a deep tight cun, with a deep wiry tight guan, and a deep weak chi. The pulses also showed an emphatic knotted (jie ) quality. The previous prescription was continued. At week two, the patient returned and reported an average blood pressure of 140/85 mmHg with occasional lows of 135/80 mmHg. The heart rate however had slowed to around 40 bpm with lows of 35 bpm. The overall pulse quality was similar to the previous two weeks but there was again an emphatic knotted quality. It was concluded that the sour flavour of Wu Mei strongly reduced the wind of the wood element and as a result slowed down the heart rate. Wood is the mother of fire and direct reduction of wood here seemed to negatively influence fire. The prescription was modified to support Heart yang by increasing Gui Zhi to 12 grams. The patient returned at week three and reported an average blood pressure of 115/75 mmHg. Heart rate had picked up to an average of 65 bpm. The patient’s physician had decreased the dose of Spironolactone to 50 mg qd. The same prescription was continued. The next week, the patient was reporting a steady average blood pressure of 110/75 mmHg with lows of sometimes 100/70 mmHg. The treatment with Wu Mei Wan was continued for another six months after which it was decided to shift treatment to focus more on management of diabetes and recovery of Kidney functions. Ultimately, the patient was taken off of Spironolactone and received decreased doses of his two other medications. Even if he was never fully taken off the drugs, there is obvious causality detectable between the introduction of Chinese herbs into his picture and the steady but rapid decline in his blood pressure. Although the use of Wu Mei Wan in the treatment of diabetes is suggested in contemporary Chinese literature,57 in this patient’s case, the ultimate prescription that lowered blood glucose to satisfactory levels as well as decreased creatinine and BUN values to within normal was Shen Qi Wan (Kidney Qi Pill). Case 3: Myoclonus and spontaneous orgasm Myoclonus is a symptom and not a diagnosis of a disease. It is the sudden and involuntary jerking of a muscle or group of muscles. Myoclonic jerks usually are caused by sudden muscle contractions, called positive myoclonus. The twitching cannot be controlled by the person experiencing it. Commonly the symptom is of neurological nature, caused by the central nervous system. Presenting at the clinic was a female patient, 28, who had been experiencing negative myoclonus triggered by muscle relaxation for an undefined number of years. Physicians suspected a case of cortical reflex myoclonus but tests were inconclusive. The myoclonus manifested with a sudden strong contraction of the rectus abdominis muscles that looked as if the person was trying to sit up from lying down. She also suffered spontaneous repetitive orgasms during the night without any external stimulation whatsoever. She was personally unaware of the fact but her partner noticed the events up to 20 times per night. She had mild acid reflux and heartburn. She also suffered poor balance with a tendency to fall over, as well as vertigo. On the first visit, pulses were slippery rolling upwards from both cun onto the thumbs. The initial diagnosis was Running Piglet (Bentun ) and Ben Tun Tang (Running Piglet Decoction) was prescribed. This Jin Gui Yao Lue prescription treats adverse flow of internal wind and ministerial fire rushing upward. After one week the patient returned with only mild improvement, mostly on the level of more relaxed back muscles. The myoclonus was unchanged. The patient was experiencing bloating in the lower abdomen and slow bowel movements. Pulses were similar to the first week and displayed an ‘’ The heart rate however had slowed to around 40 bpm with lows of 35 bpm. It was concluded that the sour flavour of Wu Mei strongly reduced the wind of wood element and as a result slowed down the heart rate. Wood is the mother or fire and direct reduction of wood here seemed to negatively influence fire. The Lantern 35 feature ‘’ One can only gain mastery of the full breadth of a prescription’s clinical applicability when one has a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of a conformation from all possible angles. additional wiry quality across all positions. The diagnosis now was changed to jue yin disease with visceral reversal: zang jue. The prescription was Wu Mei Wan plus Zhi Shi Shao Yao San (Unripe Bitter Orange and Peony Powder) for the lower abdominal fullness and pain, along with the addition of Zhi Gan Cao to encourage Shao Yao Gan Cao Tang (Peony and Licorice Decoction) to relax muscle spasms. Wu Mei 48g Mume Fructus Huang Lian 6g Coptidis Rhizoma Huang Bai 3g Phellodendri Cortex Gui Zhi 6g Cinnamomi Ramulus Chuan Jiao 1g Zanthoxyli Pericarpium Gan Jiang 3g Zingiberis Rhizoma Xi Xin 3g Asari Herba Fu Zi 6g Aconiti Radix Lateralis Prep. Ren Shen 3g Ginseng Radix Dang Gui 3g Angelicae Sinensis Radix Bai Shao 15g Paeoniae Radix Alba Zhi Gan Cao 9g Glycyrrhizae Radix Prep. Zhi Shi 9g Aurantii Fructus Immaturus The patient returned at the end of the second week reporting good progress. The muscles in her lower back were more relaxed and her bowel movements much easier. The abdominal pain had disappeared. She was still having the myoclonus but both frequency and intensity had decreased markedly. The pulses were less slippery and rolling upwards onto the cun positions on both hands. The left hand guan position showed an increased wiry and hollow quality while the right hand guan was hollow overall but weak and empty. Wu Mei Wan was refilled with the original modifications, but since internal wind was still strong it was decided to increase Shao Yao Gan Cao Tang in the prescription by increasing Bai Shao to 30 grams. At week three, the patient was reporting continued improvement of the myoclonus to the point where some days it was hardly noticeable. The pulse, however, was still very wiry and hollow and Bai Shao in the prescription was increased to the same amount as Wu Mei – 48 grams. This prescription with occasional modifications was continued for six more months until the patient experienced no more myoclonus. The spontaneous orgasms decreased in 36 Vol 5–3 frequency with the addition of Long Gu and Mu Li but never fully disappeared. Conclusion This article has hopefully succeeded in demonstrating that jue yin disease deserves as much attention as any other chapter in the Shang Han Lun, and that its premier prescription Wu Mei Wan (Mume Pill) is clinically applicable for much more than simply roundworm infection or chronic diarrhoea. Knowing the mechanisms involved in the pathology is the key. One can only gain mastery of the full breadth of a prescription’s clinical applicability when one has a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of a conformation from all possible angles. Endnotes 1. Shang Han Lun, line 326: “In jue yin disease, there is consumptive thirst (xiao ke), qi surging upwards striking the heart, painful heat in the heart, hunger without desire to eat, vomiting of roundworms after eating, and if purged there will be incessant diarrhea.” 2. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 68: “Over shao yang, fire qi rules, and in the middle is seen jue yin. Over yang ming, dry qi rules, and in the middle is seen tai yin. Over tai yang, cold qi rules, and in the middle is seen shao yin. Over jue yin, wind qi rules, and in the middle is seen shao yang. Over shao yin, heat qi rules, and in the middle is seen tai yang. Over tai yin, damp qi rules, and in the middle is seen yang ming.” 3. Ibid. 4. Ibid. 5. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 6: “So it is that in the separation and union of the three yin, tai yin opens, jue yin closes and shao yin pivots.” 6. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 49: “Taiyin is zi, for in the 11th [lunar] month the ten thousand things are all stored within the centre.” 7. In the Yi Jing hexagram 24, Fu, is “zhen [earthquake] below and kun [earth] above” gang zhen xia kun shang. It is also known as “thunder within the earth” lei zai di zhong. Kun is the second hexagram and indicates earth. As the Yi Jing states: “earth is power of kun” di shi kun. While the 51st hexagram Zhen or earthquake, is considered to be “thunderous like flowing water” jian lei, thus forming the overall feature picture of the thunderous stirring of quelling water from within the earth and the recovery of yang-like upward movement from silent yin-like inactivity. In Fu, one solid line appears under five broken lines, and is the result of the extreme yin that engenders lesser yang. This one yang line represents shao yang ministerial fire within the earth, and resonates with the Gallbladder. 8. Shang Han Lun, line 328: “Jue yin disease tends to resolve between chou time [1am] to mao time [7am].” 9. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 74: “The emperor says: The branch and root of the six qi follow different [rules], how so? Qi Bo answers: The qi can follow the root, some follow branch and root, and some do not follow branch or root. The emperor says: I would love to finally hear about this. Qibo says: Shao yang and tai yin follow the root; shao yin and tai yang follow the root or the branch; yang ming and jue yin do not follow root or branch but follow the middle qi. So for those that follow the root, the transformation is engendered from the root, those that follow branch and root, can transform from branch or root, and those that follow the middle, will transform as their middle qi.” 10. Shang Han Lun, line 357: “When in cold damage that has lasted six or seven days, after great purgation, when the cun pulse is deep and slow, and there is mild reversal flow of hands and feet, and the lower division pulses fail to arrive, the throat is obstructed, and there is spitting up of pus and blood, along with incessant diarrhea, then this is difficult to treat, and Ma Huang Sheng Ma Tang governs.” 11. Shang Han Lun, line 371: “For hot diarrhea, with downward heaviness, Bai Tou Weng Tang governs.” 12. Shang Han Lun, line 334: “In cold damage, when there first is reversal and then fever, then diarrhea imperatively will arrest spontaneously. But when there adversely is sweating, for who has a sore throat, then this is throat obstruction. When there is fever without sweating, then downpour imperatively arrests spontaneously, if it does not stop, then there imperatively will be pus and blood. For who has pus and blood, the throat will not obstruct.” 13. See Endnote 1. 14. Ibid. 15. Ibid. 16. Ibid. 17. Ibid. 18. Shang Han Lun, line 225: “When the pulse is floating but slow, there is fever on the surface but cold in the interior, and downpour of clears and grains, Si Ni Tang governs.” 19. Shang Han Lun, line 317: “In shao yin disease, there is downpour of clears and grains, with cold on the interior and fever on the exterior, the hands and feet have reversal flow, and the pulse is faint with a tendency to expire…” 20. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 22: “Liver disease is better at dawn and worse at dusk; it is peaceful at midnight. When the Liver desires to disperse, swiftly eat pungent to disperse, for it is tonified with pungent and reduced with sour.” 21. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 74: “When jue yin is in the spring … its treatment is [with] sour and bitter…” … 22. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 74: “When wind steers the earth … treat with sour warm, assisted by bitter sweet, and balanced by pungent.” 23. Shang Han Lun, line 338: “When in cold damage, there is a faint pulse and reversal, and at seven or eight days the skin is cold and the person does not have even temporary periods of peace, this indicates visceral reversal, not roundworm reversal. In roundworm reversal, the person should vomit roundworms. Now the person is still, and then has periodic vexation, which indicates visceral cold. Roundworms ascend and enter one’s diaphragm, so there is vexation, but wait a moment and it will stop. After receiving food, there is retching and again vexation, because the roundworms smell the malodor of food, and the person often spontaneously vomits roundworms. For roundworm reversal, Wu Mei Wan governs. It also governs long-standing diarrhea.” 24. Ibid. 25. Ibid. 26. Shang Han Lun, line 277: “Spontaneous diarrhea without thirst belongs to tai yin, for there is cold in the solid organs, which needs to be warmed, and for which the Si Ni family is indicated.” 27. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 4: “The abdomen is yin, the ultimate yin within yin, is the Spleen.” 28. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 4: “The abdomen is yin, and yin within yin is the Kidney.” 29. Decoction Classic (Tang Ye Jing ) – also referred to as Yi Yin Decoction Classic (Yi Yin Tang Ye Jing ) or Methods of the Decoction Classic (Tang Ye Jing Fa ) – is Chinese medicine’s first formula classic written in WesternHan dynasty by unknown authors. The book is named after Yi Yin who was a Shang (1766 BCE–1027 BCE) dynasty historical figure and the patriarch of Chinese cuisine. The book was structured along three classes (san pin ) of prescriptions in similar fashion as its counterpart Divine Farmer’s Classic of Materia Medica and recorded a total of 360 formulas. It is considered Ante Babic’s Tips for running a successful clinic ... Study the classics! The Lantern 37 feature the blueprint for Zhang Zhong-Jing’s work. There is no extant copy of the work but records of up to 56 of its prescriptions were included in the works of Tao Hong-Jing, which were subsequently unearthed from the Cave for Sutra Storage (cang jing dong ) at the Dun Huang cave complex in NW China. 30. Cullen, Lo (eds) (2005). Medieval Chinese Medicine, pp. 293-305. London & New York: Routledge Curzon, London & New York. 31. Ibid. 32. Versluys, A. (2006). The Transmission Lineage of the Canonical Formulas: An Investigation into the Source of Zhong Jing’s Formulas (Jing Fang Zhi Chuan Cheng Mai Luo: Zhong Jing Fang Tan Yuan) Beijing: China State Library, Collection of Postgraduate Dissertations. 33. Ma, Ji-Xing. (1988). Philological Study of the Ancient Dun Huang Medical Texts (Dun Huang Gu Yi Ji Kao Shi ). Nanchang: Jiangxi Science and Technology Press. 34. Jiang, Chun-Hua. (1985). Shang Han Lun and Tang Ye Jing Shang Han Lun Yu Tang Ye Jing . Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Zhong Yi Za Zhi 10, p.61. 35. Xu, Chun-Lin (1984). Discussing Yi Yin Decoctions (Lun Yi Yin Tang Ye ). Journal of Chinese Medicine History (Zhong Hua Yi Shi Za Zhi , 14 (3), p. 150. 36. Wang, Shu-Min. (1991). Examination of the Dun Huang Scroll of Assisting the Body and Essential Methods for the Application of Herbs for Hollow and Solid Organs (Fu Xing Jue Zang Fu Yong Yao Fa Yao ), Shanghai Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Shang Hai Zhong Yi Yao Za Zhi , 3, p.36. 37. Tao, Hong-Jing. (456-536 CE). Southern Dynasty herbal medicine scholar and Daoist layman responsible for the preservation of and the elaboration upon the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing. His most famous works include Separate Recordings of Famous Physicians Ming Yi Bie Lu , and Collected Annotations on the Materia Medica Classic Ben Cao Jing Ji Zu . 38. See Endnote 36. 39. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 22: “The Liver rules spring, and governs the foot jue yin and shao yang channels, its days are jie and yi, for when the Liver suffers urgency, swiftly eat sweet to moderate.” 40. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, chapter 22: “[When] the Spleen desires to be moderated, swiftly eat sweet to moderate, for bitter is used to drain, and sweet is used to tonify.” 41. See Endnote 36. 42. Yin, You-Xue. 38 Vol 5–3 (1995). The Treat­ ment of 11 Cases of Roundworms in the Bileduct with Wu Mei Wan Modified . New Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Xin Zhong Yi ) 1995-1. 43. Yang, Jin-Huan , (2006). The Treatment of 69 Cases of Chronic Cholecystitis with Modified Wu Mei Wan . Henan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Henan Zhong Yi ) 2006-1. 44. Zhang, W. (2006). The Treatment of 48 Cases of Chronic Diarrhea with Wu Mei Wan . Yunnan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica (Yunnan Zhong Yi Zhong Yao Za Zhi ) 2006-6. 45. Peng, X , Wang, Hong-Bei et al, (2005). Experimental Research on Zhang Zhong Jing Formulas pp. 592-593. Beijing: China Medical Science and Technology Publishing House (Zhong Guo Yi Yao Ke Ji Chu Ban She ). 46. Zou, Shi-Chang (2002), Treatment of Diabetic Gastroparesis by Wu Mei Pill: A Clinical Observation of 42 Cases . New Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Xin Zhong Yi ) 2002-2. 47. Yang, Kuo-Mei. (2004). The Treatment of 78 Cases of Chronic Atrophic Gastritis with Wu Mei Wan Modified . Shaanxi Journal Traditional Chinese Medicine (Shaanxi Zhong Yi ) 2004-1. 48. Li, S. (2004). Clinical Observation of Modified Wu Mei Decoction in the Treatment of 46 Cases of Chronic Atrophic Gastritis . Hunan Guiding Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology (Hunan Zhong Yi Yao Dao Bao ) 2004-8. 49. Yang, Kuo-Mei (2006). The Treatment of 71 Cases of Chronic Renal Failure with Wu Mei Wan Modified . Henan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Henan Zhong Yi) 2006-2. 50. Liu, Gui-E (2001). The Treatment of 32 Cases of Chronic Colitis with Wu Mei Wan Modified . Anhui Clinical Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Anhui Zhong Yi Yao Lin Chuang Za Zhi ) 20014. 51. Chen, Ya-Bing Chen, Yi-Feng (2005). The Treatment of 46 Cases of Ulcerative Colitis with Wu Mei Wan Compared with Control Group of 45 cases of Western Medicine Treatment . Zhejiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Zhejiang Zhong Yi Za Zhi) 200510. 52. Yang, Hong-Bo , Luo, Yu-Mei , Wang, Jing-Bo (2007) The Treatment of 44 Cases of Ulcerative colitis with Modified Wu Mei Wan . New Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Xin Zhong Yi 2007-1. 53. Gao, Xian-Zheng , Guo, Xing (2006). Fructus Mume Pills in the Treatment of Chronic Ulcerative Colitis: Therapeutic Effect Observation of 120 Cases . Modern Traditional Chinese Medicine (Xian Dai Zhong Yi Yao )2006-5. 54. Liu He-Qiang (1994). The Treatment of One Case of Recalcitrant Angina with Wu Mei Wan . New Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Xin Zhong Yi ) 1994-3. 55. Lao, Chang-Hui (1995). The Treatment of 27 Cases of Chronic Urticaria with Wu Mei Wan . New Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Xin Zhong Yi ) 1995-6. 56. Han, Mei-Ying , Zhang, M. , Zhang, Lan-Ju (1998). The Treatment of Menorrhagia and Oligomenorrhea with Wu Mei Wan . Inner Mongolia Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Nei Meng Gu Zhong Yi Yao )1998-3. 57. Liu, Li-Hong (2002). Contemp­ lating Chinese Medicine pp. 458459. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Publishing House (Guangxi Shi Fan Da Xue Chu Ban She ). Bibliography Meng, Jing-Chun , Wang, Xin-Hua , et al (1987). Translation and Explanation of the Plain Questions of the Yellow Emperor’s Internal Canon (Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen Yi Shi ). Edition used is edited by the Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Taipei: Taiwan Wenguang Book Company, Ltd (Wen Guang Tu Shu You Xian Gong Si ). Liu, Du-Zhou et al (1991). Shang Han Lun Revision and Annotation (Shang Han Lun Jiao Zhu ). Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House (Ren Min Wei Sheng Chu Ban She ). Qian, Chao-Chen , Wen, Chang-Lu , et al, (2004). Zhang Zhong-Jing Research Compendium (Zhang Zhong-Jing Yan Jiu Ji Cheng ). Beijing: China Medical Classic Publishing House (Zhong Guo Gu Yi Ji Chu Ban She ). Qiu, Pei-Ran , et al, (2002). Great Encyclopedia of Chinese Medical Works (Zhong Guo Yi Ji Da Ci Dian .) Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press (Shanghai Ke Xue Ji Shu Chu Ban She ). Yang, L. (1989). Zhouyi and Chinese Medicine (Zhou Yi Yu Zhong Yi Xue ). Beijing: Beijing Science and Technology Press (Beijing Ke Xue Ji Shu Chu Ban She ). Mitchell, C., Wiseman, N., Feng, Y. (1999). Shang Han Lun: On Cold Damage. Brookline, MA: Paradigm Lo, V., Cullen, C. et al (2005). Medieval Chinese Medicine: The Dunhuang Medical Manuscripts. London and New York: Routledge Curzon.