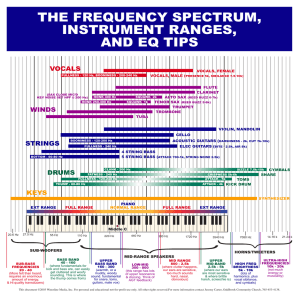

2 This is revision V 1.0.1g If you bought this eBook, future updates will always be free. For support and questions, please e-mail team@mixedbymarcmozart.com Copyright © 2014 - 2015 by Mozart & Friends Limited Written by Marc Mozart http://www.mixedbymarcmozart.com Cover and Book design by Peter "Fonty" Albertz https://www.facebook.com/Fontysound Editing by Peter "Fonty" Albertz, Marc Mozart, Tim Lochmueller All rights reserved. This eBook is protected by international copyright law. You may only use it if you have bought a licensed version from the mixedbymarcmozart.com site. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions” at the address below. This eBook is published by Mozart & Friends Limited Riegelpfad 8 35392 Giessen, Germany Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time, the author and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com THANK YOU 3 As strategically planned this book might look, it started out by many of my friends asking me the following question, or similar, on a daily base: „Hey bro, you know I’ve been doing this for a while, and I’m really happy how my songs turn out, and feel I’ve come a long way as a producer. But my mixes suck. Do you have any basic advice how to improve my mixing?“ The content of this book is what I tell my friends. In classic Grammy-fashion, I would like to dedicate this book to friendship, loyalty and the following people: Andy Henderson, Andy Kostek, Alex Geringas, Artur D'Assumpção, Chris Edenloff, Hazel Ward, Ina Sentner, ISC crew, Jack Ponti, John Brandt, Jos FungJorgensen, Kyle Kraszewski, Manager Tools, Mattia Sartori (forum.sslmixed.com), Michael Dühr, Nick Hepfer, Ömür Akman, Val del Prete, Swen Grabowski, Terance Amalanathan, Thanh Bui, Tim Lochmueller, Ulrich Mizerski, Vincent "Beatzarre" Stein & Konstantin Scherer The amazing graphics design and logo for this project was done by Peter "Fonty" Albertz, whose work and dedication catapulted him into my personal „book of legends“ in no time. Finally, my incredible family for putting up with me for such a long time. Marc Mozart, January 2015 Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com 01 02 03 04 05 Monitoring, loudness and your ears • • • • • Steal mom’s kitchen radio! From small window to magnifying glass Listening Levels Switching Speakers Essential Monitoring Setup Creating the “good enough” mix room • • • • Room Acoustics – Ghetto Style Speaker Setup, Absorbers & Bass Traps Improving the low-end of your room The 10-minute room test Preparing your Mix Session • • • • • Micro- & Macro-Management of your mix Building a DAW-template Importing the files The concept of "handles" and complete control References and A/Bing The Magic of the 1st listen • • • • • The 1st listen experience Mixing for someone else 1st listen - emotional 2nd listen - analytical Mixing your own song We are mixing! The Foundation, Bass and Gain Staging • • • • • Low-end analysis and balance Shaping Kicks, mixing bass Drum Replacement Side Chaining Gain Staging Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com 4 06 07 08 09 10 It’s all about the Vocals • • • • • A quick excusion into vocal recording Building the Lead Vocal-chain Parallel Compression Vox against the world Backing Vocals Continuity • Correcting levels pre plug-in chain • Careful Limiting • Nulling your faders Parallel Processing • Blending clean and compressed sounds • How to check if your DAW software can do this • Parallel Processing on vocals and drums Colors, Dimension + the Dynamic of your Mix • • • • • EQing: Pultec-Type EQs, Console EQs, Liniar Phase A different look at compressors Magic Chains, Reverbs, Delays, Modulation Stereo Bus magic? Automation Stems, Mastering and Delivery • • • • • Client Feedback on your Mix: ready for anything! Deadlines: how to survive them Stems, Mastering and Delivery Client: „There’s one more thing…“ Facebook Support Group Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com 5 1 6 CHAPTER 01 MONITORING, LOUDNESS AND YOUR EARS Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com CHAPTER 01 MONITORING, LOUDNESS AND YOUR EARS D iscussions around studio monitor speakers should be added to the unholy trinity of conversation topics (sex, politics, religion). Most people swear by the pair they use, and roll their eyes upon listening to anything else. Let’s just start by saying that you probably all have a „standard“ pair of nearfield studio monitors. Most likely some type of Yamahas (with the iconic white woofer), or Dynaudio, KRK, Adam, Focal, Genelec, Tannoy, Mackie. You have learned to deal with them, more or less. And you won’t hear a recommendation from me at this point. None of them are „perfect“ - for mixing, nearfields are just one of several reference points. What I’m proposing is that you add another pair of monitors, and not only will those be the most important monitors you will ever own, they will also help you to draw better conclusions from what you hear on your pair of nearfields. „Another pair of monitors? Oh shit - thats expensive, right?“ No, it’s not. Maybe 50 bucks on eBay. Not more. What you need to add is a very honest small portable - „honest“ meaning from the time before manufacturers started using „psychoacoustic“ digital gimmicks from „super mega bass“ to „maxx bass“. There are thousands of different models that would fit the bill, and you might have to try a few. Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com 1 7 Actually, look at what mom is listening to in the kitchen. And steal it. If mom insists on keeping the kitchen radio where it is, there’s a good chance you can get one for cheap at a flea market/garage sale. Here’s the profile for your new monitor system: • • • • • • • • • • 1990s portable audio system, can be mono or stereo not the „super bass“-type breakdance ghettoblaster… single woofer, no ported speaker design (1-way) keep EQ flat switch off „bass boost“ or similar smaller = better mono or stereo, both works small enough to fit in a 19“-rack external AUX input (1/4 Inch-jack or RCA) less than $ 50 on eBay Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com 1 8 EXAMPLES FOR SPECIFIC MODELS: I keep getting e-mails asking about specific models that fit the bill. But really, go on eBay, buy a few and test them. I use a Sony ZS-D7 that cost me €40 and does a great job, but there are many other types and brands. Some of you might have heard about the Sony ZSM1 that Chris Lord-Alge uses - these are getting super expensive now and are almost impossible to find - I think Chris bought them all. Sony ZS-M1 (impossible to find, CLA bought them "Tivoli Audio" (entire range - expensive hipster kitchen radios) http://tivoliaudio.de "clones of Tivoli Audio aka „kitchen radio“ (Aldi, Lidl discounters sell these on a regular base) The old masters of engineering used the original "Auratone“-speakers for similar purposes, and there are a bunch of Aurotone-clones around (active/passive, and even some DIY-plans floating around the web). Don’t get too nerdy on this though… http://www.trustmeimascientist. com/2012/02/06/auratone-avantone-behritone-review/ Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com 1 9 You: „nothing to worry for me, I’m al ready sorted - I always listen to my mixes on a pair of computer speakers!!“ No! Not modern computer speakers or iPod/iPhone-dock speakers!! You: „why not?“ • The inexpensive ones are generally lacking in quality. • The great ones (like B&W Zeppelin) don’t have that 1-way speaker „kitchen radio“ vibe. • many use psychoacoustic technologies that make your mix sound better than it actually is ( boosting bass and treble, fake stereo width, etc.) • most involve a cheap frequency crossover (separating tweeter and woofer information), which at this pricepoint, introduces bad phasing and comb filtering. Licensed to flemming pedersen. Email address: flemming.oe.pedersen@gmail.com 1 10 1 11 I WANT YOU TO MIX LIKE SOMEBODY WALKING BY Here’s what I recommend: monitor on the portable as long as you can, at the lowest possible volume. You will find that when you’ve build your mix on the portable, then later on switch to the Nearfields, you have far less to correct than when you do it the other way around. ONLY use the Nearfields when absolutely necessary. The difference is similar to being ON a stage with a band versus walking by along the street seeing a band play from a distance. I want you to mix like somebody walking by. OVERVIEW: MONITOR SPEAKERS - FROM SMALL WINDOW TO MAGNIFYING GLASS. • • A. Different size studio monitors are tools for SPECIFIC purposes. the following assumes listening levels that don’t require you to raise your voice for a conversation 1990S PORTABLE AKA MOMS KITCHEN RADIO Your „window to the world“ - this is how most people will hear your mix. 1 12 +++ POSITIVES +++ 1 13 • great for all of the big decisions and the overall balance • good for 8+ hours of mixing/day without experiencing ear fatigue • much less susceptible to room acoustic problems (simply because they don’t have extended low-end) • use 50% of your mixing timeNote: place these on the side or behind you - - - NEGATIVES - - • not suitable for adjusting or revealing lowend issues (under 60 Hz) • not suitable for dialing in the final amount of top-end you want in your mix (12kHz and higher) NOTES • place them behind or to the side of your sweet spot • check how full and loud the best mixes by worldclass mix engineers sound on this • keep switching back and forth between a library of references and your own mix • find out where your own mix stands relative to top quality mixes. (we’ll be talking more about mix references in Chapter 3) I want to point out that once you decided for a certain model of portable/kitchen radio, you have to listen to a lot of reference mixes on it and just spend time with them. I'm listening to a lot of chart stuff on my portable and know exactly how my references sound on it. It can take a few weeks to really dial in on a system, and it takes longer, the more expensive and bigger the speakers (as they are more complex to understand). MOM’S KITCHEN RADIO SPECIAL TIP: 1. Listen to some proven famous reference mixes and turn volume until it collapses (distorts) 2. Compare how much you can turn your own mixes up until they distort. 3. Adjust! (If your mix allows for more undistorted loudness, it doesn’t have enough low-end) 1 14 B. STANDARD NEARFIELD SPEAKERS 1 15 • what most musicians are used to work with • many people assume that maximum linearity and neutrality would be ideal for those. • actually, it doesn’t matter when they’re a bit coloured. • the classic Yamaha NS-10Ms have agressive high mids that put vocals in the spotlight and worked well for engineers over the last 30 years. • what you chose as your main nearfield speakers is a subjective choice. • many people have two different types of nearfields, or add a subwoofer to them. + + + POSITIVES + + + • • good for 4+ hours of mixing/day without experiencing ear fatigue use 30% of your mixing time 1 C. FULL RANGE AUDIOPHILE HIGH-END SPEAKERS • I wouldn’t say that this third pair of monitors is optional, but they add considerable cost to your setup. • These are not speakers you can carry around in a flightcase, or setup quickly by placing them on the meterbridge of the console. • your „magnifying glass“ - unveals tiny details difficult to spot on the smaller systems • not suited for more than 1 hour of listening • use 10% of your mixing time They’re either • flush-mounted speakers (build into the wall) that have been part of the studio’s acoustic design • or free-standing floor-speakers 16 + + + POSITIVES + + + 1 17 • great for EQing sources, surgical finding and removing unwanted resonances • judging and adjusting low-end balance • finetuning - - - NEGATIVES - - • not suitable for starting a mix (you will rely too much on a low-end that doesn’t work in the real world) • not representative for what 99 % of people listen on LISTENING LEVELS 1 18 „Listening at loud levels is a form of drug consumption.“ • listen at the lowest possible level (example: you can still hear the fan-noises of your external harddrives) • you should always be able to have a conversation without having to speak up while the music is playing • at these levels you will be able to do 8 hours of mixing without a long break • you will find that the mixes you create at these levels sound full and huge at loud levels Warning: • the more you start turning levels up, the more your judgement will be clouded • listening at loud levels is a form of drug consumption: the joy of loud levels overrides your ability to objectively judge the mix Disclaimer: Keep in mind: we are talking about mixing here - I’m totally aware that during production, „beat-making“, songwriting, arranging etc. many of you are inspired by loud levels, and there is nothing wrong with that. Mixing is not creating though - we’re trying to improve the sonics of something that has already been created, and to make sure it translates to a wide variety of situations. There’s no better feeling than turning up a mix that has been created at low levels - I know you’ll be tempted. Resist it! 1 19 When listening at loud levels works: • five minutes before you have a break • at the end of your work-day SWITCHING BETWEEN SPEAKERS Remember what I’ve said above - divide mixing time as follows: 50% moms kitchen radio 40% nearfields 10% full range audiophile speakers 1 • that said, switch back and forth between the different systems A LOT • you need to be able to A/B/C-switch between these 3 sets of speakers • they need to be level-matched (= when you switch the speaker set, the perceived level remains exactly the same) • a „dim“-functionality that allows to switch between two pre-set listening levels is very helpful Traditionally, in professional studios this is something the Console Centre Section of a large format console does. 20 1 • shocking, but DAW manufacturers have forgotten to include the functionality of a console monitor section, although there are a few exceptions • there are a number of „monitor controllers“ on the market in all price ranges • a small mixing console can also do this job, note that used recording consoles can be a bargain these days 21 If you don’t have a console or monitor controller, passive speaker switchers are inexpensive and do the job. ESSENTIAL MONITORING SETUP The minimum recommended setup can switch between two speakers: 1. your main nearfield speakers, optionally with a subwoofer 2. a small portable stereo or kitchen radio with aux input (one way speakers, no speaker ports, traditionally studio have been using the Aurotones or a small Sony Portable) An extended setup would utilize 3 or more sets of speakers. 1 22 FAQ 1 23 Why place the portable / kitchen radio off to the side or behind you as opposed to in front of you? It's a philosophical thing - the portable shouldn’t be in your mental focus. The mix needs to catch your attention on semi-muddy speakers that are not pointing to your ears directly. Thats the whole point of the little kitchen radio in an odd place. Good Mixing translates the production for the consumer. As I said in this chapter, I want you to mix like somebody "walking by“, not like you’re the performer on stage. We need to stay very objective and use many tricks to not get involved too deeply. Even more important when we are mixing your own production or song. That said, once you got the basics sorted out on the portable, by all means move on and get the subs working! More on that in a later chapter. Do you usually start your mix listening on the portable? During the first 50% of the mix, I do anything on the portable that doesn’t require a „magnifying glass“ into the low-end (below 60Hz) or high-end. Later on, more nearfield and full-range, but even when you end up much less than 50%, make sure to always keep coming back to the portable. How do you deal with „ear/mind fatigue“? Take a walk, breaks are important. Leave the studio environment and reset your brain as often as possible - for me every two hours, up the point when the mix really starts coming together and I’ll dance around the room like a mad man. I've always done my mixes at quiet levels but never understood why, aside from listening/ear fatigue. What is the science behind it? Room acoustics are linear, frequency curves of a room stay the same regardless the levels. The difference is in the perception. By mixing at low levels you have a competitive advantage - you want the consumer to identify how great your song/mix is even when they hear it somewhere on the street, in the kitchen, in the background at a restaurant, at any level. You mix from a consumer perspective. It makes you focus on the things that are important in the mix. Rarely do we get the chance to sit a consumer between two great speakers that are fully turned up. It's a real challenge to get a kick to have punch and attack when listening at a low level, and to level the vocals consistently so you can understand every word. But once you get these right on the portable, you have a real winner in your hand. Aurotones and their clones - should I buy one and use them in mono, or get two for stereo? both works - and if you buy two still keep them very close together, so you can test your panning/stereo effect decisions in a narrow window. What about listening in your car? Listening in your car is worth talking about. As many of you already know - it works very well for checking mixes. 1. if you’re listening to music in your car a lot, you know how it’s supposed to sound and will spot problems in your mix instantly 2. you’re listening outside your studio environment, and similar to consumer habits 3. cars are pretty good listening rooms, even from a 1 24 room acoustics perspective (no parallel walls to begin with) 4. probably the highest quality listening for consumers, considering Hi-Fi culture is not mainstream any more (as it was in the 80s) Do you recommend having fixed listening levels and how would you achieve that? I personally use the DIM button to switch between lower and higher listening levels. It's great to be able to program the relative DIM level. My general recommendation is to listen as low as possible, for as long as possible. I wouldn’t go OCD over measuring exact listening levels. That said, here’s an article where Bruce Swedien touches on the topic: http://www.prosoundweb.com/article/print/make_ mine_music_part_2 1 25 2 26 CHAPTER 02 CREATING THE “GOOD ENOUGH” MIX ROOM CHAPTER 02 CREATING THE “GOOD ENOUGH” MIX ROOM H ere comes a HUGE DISCLAIMER at the beginning of this chapter: this book is focussed on mixing, not room acoustics. Room acoustics is a complex science, and if you are planning to get nerdy over designing a perfect mix room, and you’re prepared to stop making music for a year, or you have put $ 50.000 aside for that purpose, then this chapter will not teach you all of what you need to know! Just know that professional studio design starts with building a room that has mathematically perfect room ratios, so its frequency response and reverb times are 100% predictable. That said, what you will learn in this chapter is totally aligned with what a professional studio and room acoustics consultant will tell you. 2 27 NOW THAT WE GOT THAT OUT OF THE WAY – HERE WE GO: • Lack of Acoustic Room Treatment is the single biggest cause of frustration during the mixing process • Records are made inexpensive at people’s homes today, and with the music industry on a “Titanic”course, this won’t change any time soon. • The majority of producers are set up in an untreated small or midsize bed- or living room. ROOM ACOUSTICS - GHET TO ST YLE The TOTAL COST of a Basic Room Treatment I’m discussing in this lesson is $ 300. And I bet you it easily beats many $ 1000 pre-made room treatment set you can buy. This article is not gonna give you an in-depth theory-lesson on room acoustics – instead I will show you the cheapest way to give your mix room a massive improvement – without breaking the bank. 2 28 FIRST RULE 2 29 The speakers and you have to build an equilateral triangle. If possible, face the small side of the room, and set the speakers up so that the distance to the left and right side-walls are equal. Self explaining, right? I’m sure you’ve seen this before! EARLY REFLECTIONS FROM THE SIDES This picture explains the problem best… right side is treated, left side is untreated:  Ideally, we only want the direct sound that comes from the speakers (-> green arrows) to reach our ears. But unfortunately, some of the sound goes to the sidewall and bounces back from the wall to your ear (-> red arrows), and that journey adds a millisecond of a delay to the direct signal, which causes some nasty phase cancellations – NOT GOOD! The graphic shows an „early reflection panel“ mounted on the right hand side to the listener (producer/engineer), and you can see how it doesn’t reflect back anymore (-> yellow arrows). SOLUTION A relatively basic early reflection panel does the job. This could be a self-made wooden frame covered with cloth, and some Rockwool behind (or Owens Corning 703 fiberglass boards). Note: this is NOT, and doesn’t have to be a Bass Trap. One layer of Rockwool is sufficient. $ 20 half a pack of rockwool $ 20 squared timber $ 5 cloth $ 5 misc. ––––– $ 50 EARLY REFLECTIONS FROM THE CEILING Yep, the ceiling has the same effect as the side-walls. Sound bounces back from the ceiling and mixes with the direct signal when arriving at your ear. That's why we put another absorber above your head. 2 30 It’s called an “Acoustic Ceiling Cloud”. 2 31 For my own mix room I have built a 3 x 3 meter ceiling cloud made of a timber frame, covered with cloth, and adding a layer of Rockwool on the back of it. I made it that large mainly because the console underneath is almost 4 meters wide. The one thing you need to be extremely careful with, is assuring that the ceiling cloud can’t fall down on your head. In my own room we drilled 6 massive hooks into the structure of the ceiling and used them to attach the ceiling cloud. The cloud in your own room doesn’t have to be that large - if it covers your listening area above the speakers, it will do the job. Breakdown of the material list would be similar to the two Absorbers: $ $ $ $ 20 half a pack of rockwool 20 squared timber 5 cloth 5 misc. ––––– $ 50 IMPROVING THE LOW-END OF YOUR ROOM This is easy; • make sure you have at least 50 centimeters of free space between the wall you’re looking at, and your equipment/speakers • stack 4 large packs of Rockwool in each corner (8 packs total) • find a way to secure the Rockwool-packs, so they can’t fall on your equipment • if you (or your spouse) don’t like the look, mount a curtain to cover them 8 packs of Rockwool are about $ 200, which adds the total cost of our Ghetto-Style room treatment up to roughly $ 300. 2 32 THE FINAL PL AN FOR YOUR N EW ROOM 2 33 Optionally, as you can see in the drawing, you can plaster the entire back wall with Rockwool. It will add a few hundred $ more to your bill and can further help to smooth out the low-end in your room. As a rule of thumb, a minimum of 20% of the 5 treatable room surfaces should be covered. THE 10-MINUTE ROOM TEST 2 34 Here’s a link to a YouTube-clip with test tones I’ve created with Logic Pro – you can playback this clip to do the test I’m describing below, if you want to skip setting this up in your DAW. Be careful – as this clip starts with subsonic frequencies you won’t hear in most rooms! In about 47 seconds you will learn something about your room. Listen to see if the volume of the test tone is perfectly consistent. http://youtu.be/8Olibnhhm7A 1. Find a test tone generator in your DAW software. Most DAWs come with an oscillator or test tone generator for creating a basic sine-tone (if in doubt, google „test tone generator daw“ + the name of your software). The frequency of the oscillator can be set. (You can also use a synth playing a sinewave, THIS LIST shows the range of notes needed) 2. Turn the volume of your speakers fully down. to not destroy the speakers or your ears, as test tone generators can produce some nasty high tones! (which we don’t need for what we’re doing today) 3. Set the test tone generator (or synth) up.In Logic Pro, for example, the oscillator can be inserted as a plug-in, in any track or even output. Set the output level of the test tone to -18dB and start with a frequency of 100Hz (G2 on a keyboard). 4. Turn your speakers up slowly, until you can just hear the low 100Hz tone clearly. Do not turn it up too much – at a low volume it will be easier for you to notice changes in level, which will be important. 5. 6. Bring the frequency of the oscillator down, slowly – step by step. Take your time, change the frequency gradually from 100Hz down to the lowest available frequency, but take a minute to do that. Notice how the level of the tone keeps changing? On some frequencies the signal might seem to disappear completely, on others it’s louder than the original 100Hz tone. If you are listening on small speakers, the tone will disappear completely when you reach a certain frequency, this could be around 40/50Hz if you don’t have a subwoofer. Keep going down to perhaps 20Hz, even if you don’t hear the tone any more. Take notes of what you hear. I’m now explaining you how to write down what we hear. Finish reading the rest of this article before you start. It’s quick and easy but there are a few steps involved. Starting with a test tone of 20Hz, we will gradually move up the frequencies – and make notes about how we hear the volume changing. We take notes using the simple categories “NO TONE” – you don’t hear a test tone “LOW” – you can hear it, but it’s lower than the average “NORMAL” – the average level of the test tone throughout all frequencies “HIGH” – when it’s louder than average 2 35 Check out the chart below. (the left arrow going up shows the level you are hearing, the arrow in the middle going to the right is for the frequency of the test tone, starting at 20Hz, going up to 293Hz)  You can draw this chart in 2 min or print it from here: http://i1.wp.com/www.mixedbymarcmozart.com/ wp-content/uploads/2014/09/room_measurement_ LQ.jpg Start going up with the frequency from 20Hz all the way to 300Hz making corresponding little crosses on your printed chart. The only slight challenge is that you have to look at your computer screen to see the current test tone frequency displayed in the test tone generator, while making a subjective judgement of the perceived volume. Here is an example of how the chart of my own test looked:  2 36 (for example, at 20Hz I heard “NO TONE” hence the cross on the bottom left, at 130Hz the tone was really “HIGH”… you get the idea) BTW, just in case you are wondering why we won’t go above 300Hz… the low end spectrum is most important for the overall balance of your room, and it takes a lot more effort to fix this, while getting the mids and treble right (in comparison) is almost a trivial task when it comes to room treatment. 7. Once you’re done, connect the dots, and voilà – here’s the low end frequency curve of your room!!  Note, this is the frequency response at your listening position. The measurement curve can look different by changing your listening position even a few inches. Also, the graph doesn’t tell you anything about the reverb-time of the room which is equally important (we’ll measure that in the next part). For the graph above I did the test in my home office, which is a completely untreated and small square room with a pair of cheap active computer speakers. The results are really bad, the peak at 130Hz as well at the notch around 207Hz would make this room a serious headache to mix in. 2 37 ADDENDUM ROOM MEASUREMENT TOOLS • • REW Room EQ Wizard (free room acoustics software; PC/Mac, Java-based) FuzzMeasure Pro Audio and Acoustical Measurement Application (Mac) MANUFACTURERS • • • ROCKWOOL (Insulation Products) REALTRAPS (Bass Traps, Diffusers, Acoustics Articles/Videos) GIK ACOUSTICS (Bass Traps, Diffusers, Acoustics Articles/Videos) FORUMS • • • Gearslutz Studio Building / Acoustics Sub-Forum The Acoustics Forum at PRW (moderated by Thomas Jouanjean/Northward Acoustics) Recording Studio Design Forum (by John Sayers) STUDIO DESIGNERS • John H. Brandt Acoustic Designs ROOM ACOUSTICS THEORY • Wikipedia Article 2 38 FAQ 2 39 Room Acoustics are linear. The laws of physics are stable. While - as described in lesson 1 - mixing at low levels is highly recommended, it does NOT take the characteristics of your room out of the equation. The difference you might perceive is rather related to the Fletcher-Munson curves, aka the ISO certified Equal-loudness contour. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fletcher–Munson_curves http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equal-loudness_contour You can’t have „too much“ bass trapping. More bass trapping does NOT reduce the level of bass, but it makes it more balanced and reduces it’s reverb time. Which is always a good thing. Bass Trapping is most efficient in room corners. Note: there are 12 corners in each room. Please be aware that when looking at commercial studios, the „walls“ that you see are often fake walls made of fabric or wood slats with gaps. Behind those, a lot more bass trapping might be going on. In order for subsonic frequencies to not bounce back from a wall, you need rock wool or hanging bats several foot deep from floor to ceiling. Health Considerations Glasswool is made from sand. Rockwool from basalt. It may be irritating while you install it in your room, but it is NOT carcinogenic. The binder used in each formulation may have some toxicity but if you air out the stuff before you put it in your room it won't affect you. If you have allergies or are asthmatic, take precautions - cover well when working with it. If you want to ensure that no fibers escape from the bass traps you build, first apply one layer of ticking fabric before the 'dress' covering of burlap or your choice of material. The fabric that you choose must have a very low gas flow resistivity (GFR). Place the cloth you wish to use over your face and if you can breathe comfortably - use it. If you have difficulty breathing through the fabric, don't use it. Buying ready-made acoustic panels/bass-traps Whatever ready-made acoustic panels or bass traps you buy, make sure to find some testing data from an independent lab. Testing labs use standardized procedures so that you can compare different materials with each other. 2 40 2 41 3 42 CHAPTER 03 PREPARING YOUR MIX SESSION CHAPTER 03 PREPARING YOUR MIX SESSION M ixing is 80% preparation and 20% inspiration: there is a good reason why I made this the subtitle of this book. However, mix preparation is NOT mixing. Ideally, it is a process separate from the actual mixing. Many top engineers delegate this to their assistants, to be able to start the mix with fresh ears. It's NOT a trivial task - those assistants working with the world’s best mix engineers are top engineers in their own league! 3 43 WHAT IS MIX PREPARATION? 3 44 Mix preparation is drawing the final line between the definite end of production, and the start of the mix, and has two primary objectives: 1. Micro-Management: to check the individual audiotracks of the production „under the microscope“ and fix obvious flaws 2. Macro-Management: to make the mix manageable example: song structure example: tracks organized by colors and instrument groups MIX PREPARATION - BASIC FIRST STEPS 3 45 Before we go into the details - here are the basic first steps: • downloading the files: files will usually be supplied through a download-link or a shared web-space like Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive, box.com or similar. Do not worry if the files comes as a .zip or .rar-file. Those compress the size of the files into a smaller package, but once decompressed, the audio files are the same as the original. • ALWAYS import the audio files of the production into an entirely new session • work in 24bit (or higher) and in the sample-rate that was used by the producer, most commonly 44.1 or 48kHz • you may get files in a „high sample rate“ (88.2, 96, 176.4, 192 or even up to 384kHz), it all depends on the CPU-Power of your computer • if in doubt, convert down to 44.1kHz, as constant „CPU Overload“ messages will seriously disrupt your workflow MIX PREPARATION - MICRO MANAGEMENT 3 46 This first part of Mix Preparation only takes a lot of time if the producer hasn’t done his homework - it’s easy for the producer to do this at his end of the production, as part of printing the individual track files. Oh, maybe you are the producer. We will have some thoughts on mixing your own production in Chapter 4, but for now just keep in mind that it is all about making production and mix two completely separate jobs. The tasks involved here are overlapping with what many producers do when they print their files for mixing: • removing unwanted noises and clicks • if necessary, replacing clicks and transitions between noise/silence and signal with little fades or crossfades. • removing low-end rumble with a High Pass Filter. Be careful not to cut too high, and use a linear phase EQ. An analyzer can help to visually show you what’s useable signal, und whats just useless low-end rumble. • fix obvious flaws related to tuning and timing, unless they are intended. Keep in mind that there is a fine line between fixing a flat or sharp note, and overdoing tuning. • you can do some very broad EQ-ing at this stage, if you feel it’s necessary - just as an example, tracks of Electric Guitars, Piano and Bass Guitar typically lack High Frequencies. If you feel confident about doing broad EQ strokes at this point - go for it. Don’t touch EQ of drums or vocals though. They’re too complex to make broad decisions on at this point. • every now and then I receive vocals that are severely over-compressed and/or over-EQ’d, and you can always spot that in the quality of the „Esses“ aka sibilance. If the vocals you have to start with already have a problem in this area, they need extra attention • print all the changes you’ve made here to a new audio file, and re-import it • if you find ways to reduce the numbers of tracks you have to deal with: do it! Example: convert two mono backing vocals into a stereo-file hard-panned L/R. CONCEPTS FOR FIXING VOCALS THAT SEEM HOPELESS: Fixing a vocal with excessive Sibilance (Esses) The problem is often that when the lead vocal has already been compressed during tracking, and has excessive sibilance, a DeEsser can’t reliably detect the Esses in the recording 1. first create different versions of the vocal-track you want to rescue using a De-Esser, next print the DeEssed versions to new files as follows: A: untreated B: light De-Essing applied C: extreme De-Essing applied 2. Stack the audio-files as tracks underneath each other in your DAW, keep all the tracks selected and cut them at the same time to separate the Esses out. 3 47 You can see in the waveform-graphics where an „Ess“ starts. Always try to cut at a point where the waveform crosses the „zero“-line in the middle. 3. Select the „Ess“ that sounds most natural to you, and move it in place to the original one. DE-COMPRESS VOCALS Yes, you can bring back lost dynamics into over-compressed vocals. You simply lower the parts in the audiofile that are too loud. Depending on what your DAW offers, there are two ways: A. Cutting between syllables is an option when your DAW offers an individual volume/gain setting for each audio „snippet“. Of course you have to create very short crossfades between the snippets, to avoid clicks. B. Automation nodes are available in most programs. Where in example A you would just make a cut, you will have to create two automation nodes. This technique for de-compression can of course be used for any type of recording, not just vocals 3 48 MIX PREPARATION - MACRO MANAGEMENT 3 49 There is a presumption amongst many musicians that mixing is a very complicated process. I guess this stems from pictures of massive studios with 80 Channel mixing-consoles, or the mental overload created by a DAWsession that has 200+ tracks. However many tracks the source-material has, the objective is to reduce the DAW session to a size that allows us to make quick and intuitive decisions. As soon as the creative mixing process starts, time works against us. This is because objectivity disappears the more we get emotionally attached to the song we work on. You can’t just mess about for hours and not make progress. DAWs have turned audio material, tracks, and many more aspects of a production into visuals. This can be both useful and distracting. When it comes to getting organized, a good visual representation of your song structure and the type of audiotracks in the song is very useful. On the other hand, 200 tracks can turn into a nightmare if you are not properly organizing the material in your DAW. Let me repeat: this is a process for which the best mix engineers in the world use their (world class) assistants. I do of course not assume you have one of those at hand, and my recommendation is to do this a day before the actual mix. At the very least schedule a break after. It can be done in 10 minutes. BUILDING A DAW TEMPLATE Once you have done the process of mix preparation a couple of times, you should start creating a template that you use every time you start a mix. The template will have things set up that are pretty much the same for all your mixes, from the way you graphically display the songs structure along with the tracks, subgroups or VCA-groups already configured, colors for these groups assigned, to aux sends and returns for your most commonly used FX pre-configured. LET ME GUIDE YOU THROUGH IT. • you need to create quick access to the structure of the song: a template can have a standard song structure already set up, so you can move pre-labeled markers „You can’t just mess about for hours and not make progress.“ around (INTRO, VERSE, BRIDGE, CHORUS, etc.), once the audio is imported. In Logic Pro, the song position of those markers can directly be navigated to via the Keyboards numerical keypad. Extremely useful during mix. • setup basic routing and grouping: you can route groups of instruments (e.g. drums) to the same audio subgroup, and same DAWs offer VCA faders - I personally route groups of instruments to dedicated inputs on my SSL console, and group them using the VCA grouping on the console. • setup a selection of your most important FX sends/ returns 3 50 Here’s an example: 3 51 Send 1 Standard Reverb (whatever you’ve used for years) Send 2 Standard Delay (1/2 or 1/4 Note) Send 3 Chorus, HPF at 300Hz Send 4 Small Room Send 5 Mid Size Concert Hall Send 6 Long Church Reverb Send 7 Large Concert Hall Send 8 Speciality Reverb (e.g. 3D, Gates Reverb) Send 9 Slap Back Delay (1/16 Note or shorter) Send 10 Special FX Delays (Ping Pong, etc.) other options would be specialised reverbs for Snare, Amp Chambers, etc. - I personally have set up 3 banks of 10 Sends each, for a total of 30 Send FX, send 1, 11, 21 are standard reverbs, send 2, 12, 22 are different delays, you get the idea... • set up most commonly used plug-ins on the stereo buss by default, but keep them bypassed for now • save the empty template (without any audio) to your harddrive to use with all your future mixes; keep improving your template as you use new plug-ins or change your workflow IMPORTING THE FILES • import or drag the audio-files into your template (in Logic, dragging them all into the arrange windows creates blank tracks - very useful.) • save the mix-session to your primary data drive, always make sure that all required files for your project are included in one folder (to be able to back them up to another drive by just dragging one folder over…) • backup the folder above with all files on an external drive every few hours • bring the imported audio into a defined order of tracks in your DAW software, build groups for the following instrument groups, label the tracks clearly and color-code them as follows: Drums red Sound FX yellow Bassdark green Guitarslight green Keyboards blue Orchestra orange Backing Vocals purple Lead Vocals pink 3 52 (yeah use different colours if you want, but know I’ve consulted an expert in colour psychology to find those colours) • use meaningful track names (Routing, Instrument Name) and Icons -> BUS 33 Vocals Lead • generate triggers tracks for Kick and Snare for use with Drum Replacement Plugins - just generate the triggers for now, it is not the time to pick drumsounds 3 53 If you use a console (like I do), you can assign the most important elements of the mix to individual channels, but make sure stereo outputs 1/2 go to untreated channels of your console that are set at unity gain. With everything in your DAW routed to stereo outputs 1/2 at the beginning, you can start using this default input on your console, and only route selected tracks to individual console channels. Your reverb returns for example would still come through the default stereo outputs 1/2. 3 54 THE CONCEPT OF „HANDLES“ AND COMPLETE CONTROL Starting with Chapter 5 of this book, we are going through the various dimensions that can be controlled for every sound-source in the mix, and also on busses, subgroups and the 2-bus/master. JUST A FEW EXAMPLES • • • • • • tonal balance - EQ, Filter dynamics - Compressor, DeEsser, Gate transients - Limiter, Saturator, Transient Shaper volume - Faders, Routing, Gain Staging room placement - Reverb, Delay, Panning, Stereo Width modulation - Chorus, Flanger Each of those require a dedicated processor (plug-in or outboard device). While some of these can be inserted as needed, you can save a lot of time by including the commonly used standards in your template, that are bypassed by default. You bypass them by default as when the signal fits in the mix as is, you might not need anything in the signal chain. This is what I refer to creating a „handle“ on a specific aspect of your source. Creating a handle never consists of a single „knob“ or control - even drastic changes usually consist of a number of processors with subtle settings and also, even when you apply drastic settings, subtle corrections need to be made. Basic terms like „transients“ or „dynamics“ are very technical, and rarely used by people to describe sound. 3 55 Think about how you would deal with the following requests: • • • • „The vocal needs more attitude“ „The sax doesn’t sound confident enough“ „Can you give the kick more knock“ „I want more of a 60s vibe to it“ You need a handle on all of these. The lead vocal won’t magically sound like „more attitude“ - there is no single knob for that. The „handle“ on „lead vocal attitude“ would consist of a number of processors combined that push the sound in a certain direction. While terms like „attitude“ will never be 100% objective, on this particular example I would first create a rich and full bottom to the sound, then add a lot of mid energy, probably around 2, 4 and 8kHz with an analogue EQ, and after that push the signal into a compressor that adds harmonics and saturates, even distorts the vocal. A final brickwall-limiter on the vocal chain would make double-sure that the vocal is always pushing and upfront, like someone with an attitude would stand right in front of you and not back off an inch. More „knock“ on the kick? Well, perhaps knock a wooden door, and think about what frequencies are involved? These are just two examples for the concept of handles, but once you have mastered a variety of audio tools you will be able to create a handle on everything you need to manipulate, even when attributes used to describe the desired sound are not technical, but rather referring to emotions. 3 56 REFERENCES AND A/B-ING What do I need to reference? You need to be able to switch between • the rough mix of the song you are mixing • the untreated and mastered versions of your stereo bus • a selection of references • if you have a console or monitor controller, utilise the external inputs (drag reference songs into your mix sessions, send them to a spare pair of outputs that are patched into the external inputs) • if you don’t have external inputs, use a software solution like "Magic AB" for that - it's saves you a ton of money purchasing extra converters, hardware etc. - you just use it as your last plug-in on the master, and it handles all your A/B-comparisons and references. What songs to pick as references? • • • • • build a library of reference songs include some of the worlds biggest radio hits in your library, to have a general reference for current loudness and frequency curves include some well known songs in the genre of the song you’re about to mix include some of your personal favourites if the client gave you a reference for the mix, add that too 3 57 I use the plug-in Magic AB, which allows you to compile a selection of references, and save them as a plug-in setting. • Magic AB will be inserted as the last plug-in on your stereo bus, and allows you to not only A/Bcompare between your own mix and a reference, but also between several references with one click • you can save a plug-in setting for different genres, and it will load all the songs with one click • you can add all types of audio-files, even iTunes AACs that you purchased • the audio-files can remain at their original locations on the hard drive • you can loop specific section of a reference song • each reference can be level-matched to your own mix by ear • you can globally compensate for the added loudness the references will have due to the fact they are mastered 3 58 3 59 FAQ 3 60 What kind of DAW computer do you recommend for mixing? CPU types: • • • • • • • in general, Intel i7 outperforms i5 and i3 by far because of virtual cores CPUs in Macs are usually clocked quite low (for less power consumption and reliability) higher clocked models can be build to order at the Apple Store CPUs with 6, 8 or 12 cores, including Xeon and Haswell-E are clocked slower than those with 4 cores. The machine with more cores is not always the better choice, especially considering the higher cost. all current MacBook Pro’s and iMacs with i7 CPU are great computers for mixing all versions of current Mac Pro of course fantastic machines, but very pricey and you have to add Thunderbolt to PCIe-converter if you want to use a PCIe sound card if you want to spend less, consider building your own computer around an i7 Haswell-processor. Harddrives: • • • • • • 1x SSD drive (at least 120GB) for the operation system and apps 1x SSD drive ONLY for the current projects you’re working on Harddrives for backups, can be internal or external, even USB Audio Settings: I usually start with 256 samples buffer, if needed increase to 512 samples later buffer-size can be large for mixing, as we do not • • • • track or play virtual instruments Plugin Latency Compensation set to „ALL“ (otherwise the Aux-busses and groups are adding a delay) using the „Track Freeze“ feature on every track that has plug-ins inserted Freeze (in Logic Pro X) renders your pre-fader channel signal with all plug-ins as a 32-bit file on the harddrives - that track will not require CPU-power, only a fast SSD drive if you freeze a lot of tracks; current SSDs are capable of playing back 100+ tracks in realtime note: auxes and busses always need realtime CPUpower: you can’t use freeze on those Audio Interfaces: • PCIe and Thunderbolt-solutions perform best, I recommend to avoid USB but it depends on your budget I produce house music with Logic Pro X, and often create „creative fx“ via aux send/return which play an integral role in the production. How do I deal with these? Creative FX in house music or techno - often involving automation/filters etc. - are not the "standard" category of reverbs/delays. I recommend to bounce them as an "FX only"-stem. You can either achieve this by soloing the track on which you use the send and sending the dry signal to "no output", or you could use the following trick: create a track for the FX aux return in your arrangement, then put an empty MIDI region on that track. You can then use the menu FILE -> EXPORT -> "All tracks as audio files..." and it will include your "FX only"-audio file in the folder of bounced files. Question on how to route to busses & fx - example: 3 61 you balanced the drums and added fx to them... Do you send the fx returns also to your drum buss? If not, don't you need to adjust your sends if you adjust volume on the busses? What about that if you like sharing fx (drums and others in the same room etc...) Use pre-fader sends, use the drum fx exclusively for drums, and route their returns to the drum bus as well, and/or put them on the same VCA group. Same goes for parallel compression busses, the sends to them are prefader, not following automation, but the returns follow the automation of the source - I do that via the Drum VCA group, but an audio subgroup would also work. I personally don't have a drum-bus, instead using VCA Groups on the SSL. The main point is to keep those aux returns that you use for drums (could be reverbs, parallel compression, etc.) exclusive to the drums. Even if the setting might be similar to the vocal reverb, I would be copying the setting and group all the tracks that are related to the drums, to the drum subgroup, or in my case, drum VCA fader. By keeping all FX separate and assigned to the instrument group they belong to, you get the added bonus that you can treat the FX returns for each group of instruments separately. We want total control in mixing. Also, you don’t need to create a new send for every reverb - you can send, for example, to 20 different snare reverbs from „Send 5“, and then just unmute and mute them at the aux return, one at a time, until you find what you’re after; this is a very fast and intuitive process, and gives you the option to use one or several reverbs at the same time, and level their balance at the different reverb returns. What are your thoughts on inserting reverbs right on the channel strip, and adjust with the mix parameter? 3 62 3 Nothing wrong with it. Only disadvantage I see is that you can't EQ or compress the reverb-signal separately. When using references, does the song I’m referencing have to be in the same key as the song I’m mixing? Wrong direction, you're looking at referencing too literally. Also, don’t ever reference against just one song. Look as references as another way to distract you from getting too focussed on the track you’re mixing. analogue/console vs. ITB: when do you recommend mixing on a console, and are there cases where you would prefer mixing ITB („In The Box“ = completely in the DAW) • • • • • • • • • great mixes can be created on both „console“ always means hybrid (plugins ITB + tracks fed and summed in console) even amongst the world’s Top 10 engineers, it’s 50/50 now all of these learned on analogue consoles though, and replicate that routing ITB ITB is often an economical decision, and recalls are very easy some people are fast with a mouse, some like knobs and faders = matter of taste gain staging is more critical ITB rock mixers lean towards consoles EDM producers are mostly ITB 63 4 64 CHAPTER 04 THE MAGIC OF THE 1ST LISTEN CHAPTER 04 THE MAGIC OF THE 1ST LISTEN U p until the early 1980s, Mixing commonly hasn’t been a process separate from production. The one guy that first put the specialised profession known as Mix Engineer into the spotlight was Bob Clearmountain, and around the same time, huge SSL-Consoles and the advent of sampling and harddisc recording, all of which are concepts and technologies that resulted in the modern DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) as we know it. You will see that one recurring theme in this book is the dividing line between production and mixing. We cannot mix what hasn’t been produced, and blurring the line is affecting the quality of your mix and the final product. 4 65 THE 1ST LISTEN EXPERIENCE A little philosophical discours before we dive into the technical details of mixing. Think about this: the greatest experience for anybody involved in music production is the „first-listen experience“. When you are listening to a song for the first time, it is the only time you are hearing it like the consumer out there, the person who we want to win over with our final product. But what happens when you’ve already worked on a production for a bunch of days, and maybe you are even a co-writer on the song and played/programmed most of the parts? You know where I’m going with this one, right? By the time your roughmix is done, you’re married to the song. In the worst way. The song keeps spinning in your sleep and you could not be further away from hearing your production with a fresh ear. At this point you do not hear it like a record-label A&R, a radio programmer, and certainly not like a consumer. You are emotionally connected to your work. You might be in love with it, proud of your drum-sound, the amount of bass in the mix or some of the production tricks you’ve used, or even worse, the opposite, you could be totally frustrated and tired of the damn thing! Solutions? 4 66 A. MIXING FOR SOMEBODY ELSE When you mix a song for somebody else, you are indeed having the great advantage of the “FIRST-LISTEN EXPERIENCE” A great mix engineer, within seconds of his first listen, will understand where the producer wants the mix to go, spots problem areas of the mix, and as part of his craft has the skill and the tools to translate his impressions quickly into a mix with improved audio quality. Add to that other advantages a paid mix engineer has that help him to get the job done. "What else helps the mix engineers judgement? • An environment specifically created for the task of mixing • He is mixing records to a high standard EVERY DAY. • He gets paid! Wow, who would have thought that! „Why should that make the outcome of his work any different?“ you might ask. Well, this one is easy. Let’s look at exactly what a mix engineer gets paid to do… 4 67 (just some examples of what clients request) 4 68 The mix engineer gets paid to improve the audio quality while respecting the integrity and intention of the production. His job is NOT to judge or criticise the quality of the song, production or instrumentation. Somebody who spends money on a mix engineer usually BELIEVES in what they deliver, while they are realistic enough to know that there is room for improvement I’m sure you can see why a paid mixer (whose only focus is on mixing the song for somebody else) is in a much better position to do a quality job compared to someone doing the mix as a task within a bigger project. To summarise, before you start to do any work on the mix, ask the producer to provide you with a rough mix of the song, the one the client likes best so far, the one that represents where the producer wants to go with it. Your first listen is for emotional input from the rough mix. The second listen is analytical. 1ST LISTEN – EMOTIONAL 4 69 Have a listen to the roughmix through the speakers you are most familiar with – this could be your portable stereo in the kitchen as well as your car stereo or your main studio speakers. Try not to listen with an analytical or technical ear, don’t focus on anything specific, just relax while you’re listening, and await your natural emotional response. Now go and do something else. Have a coffee, eat, do your tax return. Something fun. Let the first impression settle. 2ND LI STEN – ANALY TICAL If the rough mix made you enthusiastic and singing along, dancing or playing air-guitar, there is not much to worry about for now. For the second listen, switch back and forth between your different sets of speakers as discussed in chapter 1. The mix might not work on all systems, which can be a hint for areas of improvement. Find out why it works so well, and be careful – going forward – not to fix things that are not broken. Anyway, it will be fun to explore the multitracks, and you won’t have to re-invent the wheel on this mix. ROUGH MIX SUCKS? In the more common scenario, the 1st listen left you with mixed emotions. Maybe not exactly giving you a headache, but close to that: a feeling that something is not quite working in this rough mix. On the 2nd listen, focus on why it’s not quite working. You might not get to the bottom of the problem immediately. But further observations will get you closer. Make notes as you’re listening. Switch between different speakers. 4 TAKE NOTES! Here are some observations that I would typically come up with during the 2nd listen - take notes! (these notes are taken straight from projects I worked on in the last few months) • No lift when chorus hits. Impact even drops! First vocal note in chorus out of tune and too late. • Vocaltiming doesn’t sit tight on the beat. Esses conflicting with hi-hat and throwing the groove off. • Several Kicks and bass synth fighting for the low end. • Bass notes vary in loudness. • Drums and vocals sounding one-dimensional and squashed. • Instrumental hook too far in the back. Doesn’t shine. 70 4 B. MIXING YOUR OWN SONG There is a lot of confusion around the point that separates production from mixing. The general answer to that is very simple: production and mix are done by two different people looking at the process in a different way. Every producer is EQing, compressing, grouping, applying mixbus-treatment etc. and ending up with the best mix they could do. The mix engineer is then supposed to take that and get it to another level. Producers usually send me all of their instruments EQ’d and compressed as in the rough mix. That includes the dynamics of sidechained instruments in electronic genres - the vibe of the sidechain is certainly part of the production. Reverbs and delays are not printed, unless they create a very specific vibe that is part of the sound (example: spring reverb on a guitar). Drums and vocals would be an exception - I prefer to receive them with all plugins bypassed. A lot of my mix-work involves „recreating“ the vibe of the rough mix, but at a better quality and higher resolution. For those of you who write, produce + mix their own music, I recommend wearing two „different hats“ for those tasks. When wearing the „producer hat“, don’t be concerned with the stuff we’re discussing here. Create a vibe, go to extremes, try a lot of things, be innovative, open 100 virtual instruments, etc… your rough mix can be messy and purposely ignoring a lot of „classic audio rules“. 71 4 But when wearing the „mix engineer hat“, the focus is on retaining the vibe of the rough mix, improving the audio quality and compatibility to the various mediums the music will be played on. That involves a lot of deconstructing and rebuilding. With that, let’s dive into the details of this issue. PROBLEM – NO 1S T LISTEN EXPERIENCE • there’s no „1st listen“-experience; you will never hear your own song the same way as someone else when they hear it for the first time! SOLUTION – DISTANCE YOURSELF FROM YOUR WORK • at the point where the production is done, and ready for mixing: STOP listening to it AT ALL. PERIOD. • work on a few other songs, get away from it as long as you can, the longer the better! • even in case of a pressing deadline, DO SOMETHING ELSE for a moment, listen to lots of other music, take a walk, get a coffee: your musical brain needs a reset! 72 BEFORE THE MIX • decisions around instrumentation are part of the production, NOT the mix • print all tracks to audio-files, this will not only force you to make decisions, but will free up your computer from CPU-load you need for mixing • before you print the individual tracks, make absolutely sure, timing and tuning are where you want them, and unwanted noises and clicks are removed. • you can print some tracks as groups, for example bounce down 12 doubled backing vocals as one stereo file; you will end up with less files in your mix session and make it more manageable – reducing the size of your sessions always wins! • open the printed files in a completely new and empty session, ideally a template costumized for mixing-duties (we discussed this in Chapter 3) AFTER THE MIX • when your mix is done, consider moving your DAW into a great mastering studio and spend a few hours WITH the mastering engineer to finetune your mix. Typically, low end and vocal levels, amount of reverb and bus compression are things to discuss with the mastering engineer, plus you will hear your work in a different (and great) listening room. If you use a lot of analogue gear and outboard, you can print stems of your individual tracks and take those into the mastering session. Once all issues are resolved, leave the mastering engineer with the track for half an hour, and he’ll sort out the master. 4 73 5 74 CHAPTER 05 WE ARE MIXING! THE FOUNDATION, KICK, BASS AND GAIN STAGING CHAPTER 05 WE ARE MIXING! THE FOUNDATION, KICK, BASS AND GAIN STAGING D uring this chapter, we are building the foundation for the mix. What we’re doing now can be described as a frame in which we’ll be able to neatly insert a picture (the vocals) in the following chapter. While there are many elements that we can finetune and treat „on the fly“, the boundaries of our mix are defined by the low-end foundation and our gain staging skills. If the low-end doesn’t work, whatever sugary cream and icing we put on top will not make up for it. Before we’re starting, please get a quick idea of which key and harmony-progressions the song is using, the notes/frequencies played by the bass, and where the kick sits relative to this. If you don’t have a lot of experience with this, here’s an example on how an analysis like this can be done. The following was part of a mix analysis of the song „All About That Bass“ by Meghan Trainor, a song nominated for a Grammy in 2015. 5 75 KEY OF THE SONG + CHORD PROGRESSION 5 76 The song is in A major, based on the chord progression A major / b minor / E major / A major BASS NOTES USED + THEIR FREQUENCIES The lowest notes the bass plays are (from lowest to highest): E1 41.2 Hz (root note of E major, the dominant chord) G1 48.9 Hz (minor 3rd to E major, used as a blue note) G#1 51.9 Hz (major 3rd to E major) A1 55 Hz (root note to A major, the tonic chord) B1 61.7 Hz (root note of b minor, the minor parallel of the subdominant chord; also 5th to E major) C2 65.4 Hz (minor 3rd to A major, used as a blue note) C#2 69.2 Hz (major 3rd to A major) D2 73.4 Hz (minor 3rd to b minor) E2 82.4 Hz (5th to A major) F#2 92.4 Hz (5th to b minor) BASS SOUND 5 77 The bass sound used is a double bass played pizzicato style. The frequency-spectrum of the double bass is dominated by the 2nd harmonic (octave up, see below) and 1st harmonic (the frequencies listed above). Other than a tiny and very short plugging noise that happens around 4-8kHz, there’s not much that can be boosted to bring the bass upfront in the mix. Compare that to a bass guitar, where you can feature the mids or even run a parallel track through a distortion pedal or guitar amp. FREQUENCIES OCCUPIED BY BASS + KICK This is the complete list of frequencies the bass and kick in “All About That Bass” occupy in the mix: 41.2 Hz 48.9 Hz 51.9 Hz 54 Hz 55 Hz 61.7 Hz 65.4 Hz 69.2 Hz 73.4 Hz 82.4 Hz 88.4 Hz 92.4 Hz 98 Hz 103.8 Hz 108 Hz 110 Hz 123.4 Hz 130.8 Hz 138.6 Hz 146.8 Hz 164.8 Hz 185 Hz E1 (fundamental frequency) G1 (fundamental frequency) G#1 (fundamental frequency) KICK (fundamental root note) A1 (fundamental frequency) B1 (fundamental frequency) C2 (fundamental frequency) C#2 (fundamental frequency) D2 (fundamental frequency) E2 (fundamental frequency) 2nd harmonic of E1 F#2 (fundamental frequency) 2nd harmonic of G1 2nd harmonic of G#1 KICK (pressure point) 2nd harmonic of A1 2nd harmonic of B1 2nd harmonic of C2 2nd harmonic of C#2 2nd harmonic of D2 2nd harmonic of E2 2nd harmonic of F#2 5 LISTENING Now, have a listen to the song (best to buy the track on iTunes as it’s a great reference song) – that bluesy bassline played by the double bass is totally dominating the low end frequency spectrum of the mix, and a purely theoretic frequency analysis confirms that. LET’S LOOK AT SOME FREQUENCY CURVES! This curve is made from the intro of the song and shows JUST bass and vocals (using LogicPro X’s Match EQ “learn”-feature):  There is definitely a High Pass Filter (HPF) used that cuts even into the lowest bass note. The HPF plus the notch just below 200Hz give the bass a very defined place in the frequency spectrum of the mix. 78 5 Let’s look at the Kick Drum in comparison:  The fundamental note of the Kick sits at 54Hz, just below the root note of the song key, with the pressure point an octave higher, at 108Hz. The Kick is very compressed and sits “behind” the bass, to never dominate the low end of the track. There is another bump below 200Hz which works perfectly as the bass has a notch at the same place. The Kick is a very rich sound with lots of noises and higher harmonics, so it still sticks out, but definitely not because anything would be boosted in the low end. Note how there is nothing notable happening below 50Hz. Here’s what I’ve done to find out at what frequencies the Kick exactly sits, which wasn’t as easy as usual. 79 Logic Pro’s Channel EQ Analyser, looking at the track in a section where there’s no bass.  Next, I’m creating a very small EQ band, fully boosted (keep your speakers at low level to not blow them), then slide the frequency through the low end until I find the exact resonance frequency. I repeat this with a second EQ band and find the next big resonance above. Obviously looking at the analyser helps. When you do this, watch how the analyser reacts. Between 54Hz and 55Hz there was only a small difference, but clearly the resonance sits closer to 54Hz.  5 80 When you change the EQ gain from + 24dB to -24dB, you can completely suck the life out of the kick with an EQ notch, further proof that we found the right spots.  In my own mixes, I’m going through the same process, take a look at the song key, the frequencies and plan how to fit Kick and Bass together. Sometimes the Kick lacks clear distinctive frequencies for fundamental note and pressure point. In that case, I locate them, and boost a little bit. Sometimes though, I receive Kicks that have too much of a boost on the fundamental note or pressure point. They can be easily tamed by setting a notch EQ on the frequency and then just backing off 1-2dB. 5 81 DRUM REPLACEMENT • the whole point of Drum Replacement is to have access to a high quality recording of a great drumset with multiple microphones that can separately be accessed. You can add just a pair of overhead or room mics to give the existing drums some depth and dimension, you can add the bottom snare mic for some noise component, bring in a Kick that has defined and tuneable fundamental note, etc. • Drum Replacement Plugins can extend the repertoire of sounds you have at hand for the mix. They can help to add excitement and punch to the mix. Use them to add to what’s there, not to completely replace. • that said, if your original Kick is badly recorded or out of tune, you will always find a sound that has a similar vibe and works better; in that case, replace! Drum Replacement really means two separate elements: 1. the trigger generator, a plug-in that turns the audio tracks of your existing drums into dynamic MIDInotes if everything is set right, the trigger generator captures the full dynamics of a real drummer 2. secondly, a drum plug-in that provides you with multi-channel outputs that are identical to the multitrack recording of a VERY GOOD drum recording a great drummer playing a great fine-tuned drumset in a great acoustic space, the microphones set up by a great engineer, recorded with the best pre-amps and the best console through very good converters. These plug-ins usually provide a huge number of different samples in all dynamic ranges, multiple samples for each dynamic range, so that even if you play the same 5 82 16 MIDI-notes with the same velocity in a drumroll, it will still sound organic as no sample was used twice. Of course, you can use drum replacement to completely replace the original drumset (I personally rarely do that). The trick is to use it very subtle so that even the producer of the song won’t notice that samples are involved. Examples: • bottom snare mic, overheads, room mics • adding an organic touch to synthetic drums • provides you with a set of organic signals 5 83 SHAPING KICKS Next up, let’s deconstruct the components of a Kick sound, and look at what type of „handles“ you can create to control it in the mix. The Kick is of extreme importance, and it’s worth – as part of building your mix – to spend a few minutes creating the „handles“ to control the parameters we’re talking about in this article. What you need to control will develop as you’re progressing with your mix, but it’s important to have those controls at hand when needed, and to know how to use them. KICK TONES: FREQUENCIES + TUNING Think of the Kick Drum Sound consisting of 3 different frequency components! 1. the fundamental root note in the low end (45 – 75 Hz), 2. the pressure point (an octave higher, 90 – 150 Hz) 3. harmonics and noise (anything above). 5 84 Think of them like an ensemble of tones and frequencies, like a string section that has a bass, celli, violas and violins. To place the Kick perfectly in your mix, it helps to look at and treat those 3 distinct components separately. Some producers use different samples for these components, and I often get them as separate tracks for my mix sessions. But even if your tracks come with a single Kick, you can create a copy of your Kick track on another track. By cutting (HPF) everything below 150Hz you can exclusively treat the harmonics and noise-component (3.). Experiment with various treatments from Tape Simulation to Distortion, Compressing/Limiting, then add that channel to the original sound. Just as an example for the separation of the 3 distinct frequency components: the screenshot below shows the fundamental removed with a HPF, pressure point (138 Hz) dipped by 5 dB, and a broad boost of the “noise” of + 5.1 dB at 2500 Hz. 5 85 The fundamental (1.) and pressure point (2.) are both an essential component of modern music and need their resonance frequencies for themselves to really cut through the mix. The harmonics and noise components (3.) are very important to „find“ the Kick in your mix, especially on small consumer devices like laptops, smartphones, small portable stereos and cheap earbuds. I sometimes separate those three components to 3 distinctive tracks that sit on 3 large faders on my SSL console – top engineers have done this for many years and it’s quite easy to achieve on an SSL, you just send the signal to the routing matrix via the „small fader“, and „mult“ it to another 2 faders. Thats without even considering added parallel compression channels, and virtual overhead and room mics generated from a Drum Replacement Plugin (another future post). 808 Kicks typically have a strong fundamental, but lack harmonics and noise. Synthetic Kick Drums, like of a Roland TR-808/909 have a very clean and defined fundamental tone. It often gets bend down after the initial attack though (an Envelope Generator modulating the pitch), which means the fundamental tone of the sound sweeps through the low end, for example from 80Hz down to 10Hz. A bend can make those Kicks more difficult to mix, and I recommend to always carefully watch and use an analyzer while listening for the right balance. This is where a good sounding room is a huge advantage. There are all kinds of boxes (or their plug-in versions) that generate harmonics – from subtle Pultec EQ, Fairchild Compression, or Analogue Tape Simulation, to more extreme treatments like a Guitar Amp or Distortion Pedal Simulation. 5 86 Sometimes creating a copy of your Kick through a distortion pedal or amp simulation, mixed slightly in the original sound brings up exactly the harmonics needed to make your Kick easier to „find“ in the mix. Real Kick Drums are a lot more complex than 808/909 -sounds. A real Kick Drum is a small physical space in itself, with two resonating drum heads interacting within the recording room, which also adds to the sonic characteristics. The result are very complex harmonics, and sometimes a few neighbouring fundamentals and pressure points compete for each other in the mix. While the complexity of tones modulating, adding to and cancelling each other adds to what we perceive as a real sounding Kick Drum, there is a lot more that can be done to those sounds in the mix. Use a digital EQ with a very high Q-Factor (a narrow band) to identify the fundamentals and pressure points of the sound. Yes, there can be several competing ones, and which ones to boost and cut is depending on many factors, like the key of the song, where the frequencies of the bass guitar or bass synth sit in the mix, and of course most importantly your taste and the genre of music. Even a Kick that is totally out of tune with the key of the song and the rest of the instruments can be spot on in the mix, if it fits the genre and has the right attitude. However, tuning those frequencies in harmony with the key of the song is something many successful producers and engineers do. For more on this, have a look at my recent blog posts analyzing the low-end of the two biggest hits of 2014, „All About That Bass“ (Meghan Trainor) and „Shake It Off“ (Taylor Swift). 5 87 BTW, „convert audio into sampler track“ is a sensational feature in Logic Pro – it basically imports your audiotrack into Kick Notes in Logics EXS24-sampler, and triggers them via internal MIDI. Now that they’re in the EXS24, you can tune them in the sampler plug-in. Works great if your Kick is for example, a semitone too high, colliding with the key of the song, you just transpose it „-1“ in the EXS24 and your low-end alignes magically - sometimes 10 cent of a semi-tone can make a huge difference. 5 88 Keep in mind, low end instruments have a lot of energy, and you don’t want them to collide and modulating by not being properly fine-tuned. Regardless of how you end up balancing the different components of the Kick, make sure to find the frequencies of the 3 main components so that later on in the mix you have handles in place to balance your Kick. You can easily identify those frequencies with a digital EQ, and an analyser obviously helps. In Logic Pro X, the Channel EQ in conjunction with the built in analyzer works great for finding resonances (as the Channel EQ is creating strong resonances like an analogue EQ), however, to boost or reduce them in level I recommend using the Linear Phase EQ, which works a lot cleaner and precise which is important when balancing the low-end. Concepts to use here are to pinpoint EQ-bands to the exact frequencies of the fundamental and pressure points, and boost or cut them depending on whats needed. Also, you can make the Kick more defined by cutting the frequencies between the fundamental and the pressure points – make sure to use very high Q-factors! Again, a high-quality Linear Phase EQ is your friend. The one in Logic Pro is great, but there are many others on the market. One more thing… The final boosts and cuts should be performed when all tracks of your mix are playing, or at least Kick, Bass and Vocals. “The final boosts and cuts should be performed when all tracks of your mix are playing, or at least Kick, Bass and Vocals.” 5 89 KICK DYNAMICS: AT TACK AKA THE TRANSIENT The transient is the initial attack of your Kick. On a reallife Kick Drum, a pedal-controlled beater hits the drumskin, and that short initial impact creates the transient in the audio. On electronic Kick-sounds, the transient is either the fast ramp-up of an envelope which results in a tiny click noise (808/909) or an added noise generator with a very short envelope. In both cases, a very short click noise is the result. The added click noise was first used on a drum-synthesizer by Dave Simmons in the early 80s, if you’re old enough you might remember the SIMMONS Drumset which was basically a 5 or 6 channel synthesizer with one voice for every drum-instrument. The sounds were created by mixing short click noises (simulating the stick or beater hitting the drumskin) with tones that could be tuned and connected to a pitch envelope generator, plus longer noise sounds added to the tones. You might have heard some of those iconic „laser-gun“ or “spitting”-type of sounds from the 80s. The SIMMONS Kick-sound was somewhere in between 808/909 and a modern progressive metal Kick. 5 90  TOOLS TO CONTROL TRANSIENTS If you want to bring the transient in the Kick up or down in the mix, there are 3 ways to achieve this: 1. Transient Designers There are several of those plug-ins on the market, the most popular being SPL Transient Designer, which is based on the original 4-Channel hardware unit. Many plug-in companies offer tools to achieve similar results, I personal like the original hardware best (and there is a plug-in version of that as well) 2. Noise Gates If you copy the Kick to a second DAW track and use a noise gate to make it extremely short, you can turn the transient up by mixing the noise gate track with the original sound. If you phase reverse the noise-gated sound, you can remove the transient or at least soften it slightly. 3. Sampling If your Kick is in a sampler, you can just shorten the envelope of the sound in the sampler plug-in. See the feature we discussed above (converting an Audio Track into a Sampler Track) 5 91 KICK DYNAMICS 2: LENGTH AKA DECAY TIME To control the length of the KICK TONE is of course of utmost importance. The Decay Time of the Kick can make or break the groove, and again – it’s helpful to be able to control the three tone components of the Kick separately in length. The tools to use are somewhat similar to the Transient Control, but of course you can just go into your Waveforms and cut it where you want tone Kick to end, and apply the desired Fade to the audio. Another useful feature in Logic Pro… “Remove Silence from Audio Region”  5 92 5 93 Automatically separates the silence between the Kicks below the threshold that you can set.  Applying a fade to the separated Kicks.  Finally, the Kick sits in the middle, mono, period. At least the direct and low end component of the Kick. If necessary, split the Kick at 300Hz, keep the fundamental and pressure point mono and only leave noise and harmonics from 300Hz upwards Stereo. Set up a Sidechain. I recommend to always feed a sidechain bus with your Kick. In my personal mix template, the first send in the channel strip is set to 0dB (unity gain) and sends to Bus 64. Bus 64 doesn’t send to an output, disable the output. The busses 64, 63, 62, 61 are my standard sidechain busses for Kick, Snare, Vocals, and whatever else needs to push other elements to the back of the mix). I’m not always using it, but when I need it, it’s already setup by default.  5 94 5 95 Without going into detail here, just know you would assign Bus 64 as your sidechain, most commonly on the bass guitar or bass synth, and push the bass a few dB back, triggered by the sidechain signal. Again, Logic Pro’s standard compressor works great for that, but this technique works of course very well with a multiband compressor/EQ like the „Waves C6 Sidechain“.  These techniques will give you the handles on important parameters, and it will be a lot easier to get a great balance between Kick and Bass. Please keep in mind that having the handles in place doesn’t mean to have to use and tweak all of them. There are some genius producers out there who deliver Kicks that are sitting perfectly in the mix. In that case, turn it up and be done. BASS Getting the bass to sit right in the mix is largely depending on how much space the Kick takes, and where the bass-notes are sitting relative to that in terms of frequencies. If you haven’t fully understood that concept, please go back to the beginning of this chapter, and analyze a few songs the way I showed it. In addition to that, here’s a shortlist of things you should look at: • it requires an extremely good listening room, and full range speakers to judge the level of each bass note in the mix - you can’t trust most rooms, and while analyzers and meters are a helpful tool, you shouldn’t trust them either • here’s actually a great application phones: listen through the song to end, and level the bass - each vidually - for an even level across • the Bass does usually not have a lot of energy at the subsonic range - and if it has - it might be clever to clean it up or at least control it for headfrom top note indithe song 5 96 • while speaker systems can handle short impulses of sound below 30/40 Hz. any sustaining sound that has excessive amount of subsonic needs to be reduced to an amount that doesn’t interfere with the rest of the signals in the mix. • one way to make subsonics more dominant in the mix is to add harmonic distortion that happens in higher frequency bands • even if the fundamental notes of the bass are happening below or around 60Hz, the biggest role in how loud you perceive the bass in the mix happens an octave higher, at the so-called „1st harmonic“ • in Chapter 9, we are looking into using compressors for generating harmonics, a technique that is very relevant to bass-sounds • Sidechaining, unless used as an effect, should be a „last resort“-type of solution. You shouldn’t completely rely on it to balance Kick and Bass. • Especially in electronic genres, the key to a good balance is correct fine-tuning between kick and bass. Dissonances between the two will cost you valuable head-room in the low-end, and you won’t get your mix as smooth as you will want it. • reserve the low-end for instruments on which you can hear it. You should know without looking which elements of your mix have components of low end frequencies (below 120Hz). It shouldn’t be many - if you can’t hear the low-end on an instrument within the arrangement, filter it with a High Pass-Filter. We need that space. 5 97 The Goal at this point is to have a healthy overall balance between Kick and Bass, note, we are not determining the final amount of Low End that you want to have in your mix. Stay away from boosting any low frequencies at this point. Whether the overall amount of low-end in your mix is correct or not will be determined at a later point of time. It’s not the time for those decisions now. GAIN STAGING (DAMN – IF ONLY YOUR BANK ACCOUNT HAD ENOUGH HEADROOM!) But you’re hitting “red” all too often, start calculating and things become uncomfortable. Sounds familiar? „Digital Red“ means you’ve maxed out the bank account of your available dBs – no more credit!" Exactly how people feel about their Gain Structure in mixing – „Gain Staging“ being the strategy you chose to use your bank account of dBs, if you even have a strategy… Like your bank account, the Gain Structure of your mix needs enough headroom to be able to deal with crazy or unexpected events. The Drums are buried in the mix, and the artist wants them „waaaay“ upfront? OK, you start turning them up, and by the time they are where you need them, the drum-levels are up 6dB – hitting digital red on the mix bus! 5 98 I’ll start with some underlying history and theory. And then tell you exactly what to do about the problem… Just before Digital Audio took over as a standard, early DAW manufacturers in the 1990s made a historic mistake in laying out the wrong scales for digital level meters: no warning all the way up until 0dB, so you don’t know you’re in trouble until it’s too late. Whereas 0dBVU in analogue used to be a reference point for solid level, early Digital Audio Workstations used 0dBFS (FS for "full scale") as the “point of no return”. Sony and Studer DASH-machines did a lot better, but they were six-figure digital multitrack-recorders that were the industry-standard until DAWs took over. Fast forward – DAWs took over between 1991 and 1998 – Digidesign ProTools being the first and most popular one, others like Cubase and Logic followed by extending their MIDI-based sequencers with “audio”-features. What all of them should have done from the beginning, is declaring levels higher than -18/-15dB as „yellow zone“, and -8/-5dB as „red zone“ and also make “-18 dB” = 0dBFS, as this is exactly what happens once the audio leaves the D/A-converter. By setting the 0dB-reference to Digital “RED”, DAW designers made a historic mistake that affects the quality of audio to this day. Prior to Digital Audio, people were not leaving a lot of headroom in analogue as it would bring up noise, and driving a signal hard to tape even had pleasant side-effects for certain types of music (tape compression, softclipping transients, added harmonics). 5 99 Early Digital Audio was at 16bit Resolution (96dB of dynamics in theory), and people still felt it wasn’t clever to leave a lot of headroom. They were partly right, as the combined dynamics of 16bit and early converter designs were barely reaching 90dB, best case. From the early 2000s on though, the processing of ALL DAWs was operating at a minimum of 24bit resolution, which means you have 144dB of dynamic at hand at any time. 144dB of dynamic at hand, and people complain about not having enough headroom! That of course exceeds what analogue circuits are capable of reproducing. Even the best OP-Amps used in AD/DA-convertors can only go as far as 125dB (e.g. the LME49720), so we can plan with as much headroom as we like, it won’t affect the quality of the audio. To cut a long story short – here’s what you need to start doing: GUIDE TO SOLID GAIN STAGING STAGE 1 – TRACKING When you’re tracking vocals or instruments, keep average levels around -15dB to -18dB, peaks shouldn’t go higher than -8dB to -5dB. STAGE 2 – YOUR INDIVIDUAL TRACKS most individual tracks people send me for mixing are too loud – once I start summing them, I’m at least 6dB into the digital red. I do not compensate for that with gain reduction in my master or summing bus! With the channel fader set to unity gain (= 0dB), each single element needs to have a solid headroom of about 12 – 18 dB. I recommend putting a simple gainer plugin in the second slot of your plug-in chain (always leave 5 100 the first slot free). Producers usually send me their individual tracks pretty hot, with peaks close to 0dB, and I have made it a habit to put a gainer plugin across every individual track that reduces levels by 15dB (set to -15dB). That ensures lots of headroom in the master-bus when mixing/summing the individual signals.  STAGE 3 – YOUR MIX BUS The Mix Bus is where your Bus Compressor (if you’re using one) is inserted, and it will have other processors, from EQs to subtle Tape Compression, etc. (which is not the topic of this chapter). You need headroom coming into the mix bus (which you have assured in „STAGE 2“), but also coming out of the mix bus. Take a situation where your mix sounds great and is very balanced overall, but as you are comparing the mix to references, it lacks bass. Like, the kind of bass you would get by cranking up the bass on a HiFi Amp. That is not really a big deal – I would probably insert a Linear Phase EQ, and create a very broad boost of the lower frequencies. 5 101 This looks dramatic (+ 8dB at 30 Hz), but since this is a linear phase EQ, and the curve is very broad, it’s not: 100 Hz is only boosted 2 dB relative to 400Hz.  This „not so dramatic“ EQ curve adds about 8 dB of level to the mix bus though! Added low end needs lots of headroom. Each processor inserted on the mix-bus gives you – of course – handles to get some headroom back. I’m talking about the Input and Output-controls of a plug-in. Back off 1 dB on each of those to get some headroom back if you’re getting near the trouble-zone. When all processing is done, and you end up with 3dB of headroom at the end of your mix bus, you’ve done a solid job. 5 102 More is nice, but what we’re talking about here is the headroom you leave for the mastering engineer to do his thing. In light of 20 years of loudness wars, these guys are happy if you leave them ANY headroom. They will love you for 0.3 dB of a ceiling and no brick wall limiter used! If you make it a habit to shoot for the -3 to -5 dB range going OUT of the mix bus, you will have more space for unexpected events though. MORE THAN ONE MIX BUS I make a clear distinction between MIX BUS and MASTER BUS. One of the reasons for that is – there are engineers who work with SEVERAL master busses. Without going into detail here, this is something pioneered by mix engineer Michael Brauer on SSL consoles that have several stereo mix busses, like the SSL 6000E/G, 8000G and 9000J/K. Just as a quick example for adding a second mix bus: your track has punch, solid glue and a great low end – the bus compressor and EQ work great, BUT UNFORTUNATELY NOT for the lead vocals, they are too affected and squashed by the bus compressor. What you do is route them around your main mix bus and create a second mix bus. The second mix bus (for the vocals) will of course add some level, has it’s own signal chain, and the sum of both mix busses feeds the master bus. For that to work, you need a healthy gain structure! 5 103 STAGE 4 – YOUR MASTER BUS 5 104 OK, the master bus is where you finally mess up your audio to compete in the loudness war, right? Oh well, I’m just joking of course – or not? I personally always have a brickwall-limiter on my master bus, and thats about it. I’m limiting maybe half a dB as a standard, not more. Usually that gives me the average loudness I set out to achieve. If I want MORE RMS (average) level, I either reduce some peaks on individual tracks, or carefully adjust the MIX BUS, but NEVER do that by slamming the final Brickwall-Limiter. For the final mix pass, I just take the limiter off, and print a WAV (to hand on to the mastering engineer). ITUNES SOUNDCHECK 5 105 The easiest way to find out (in plain numbers) what type of final loudness you want to achieve, is iTunes. 1. launch iTunes on your computer 2. go to the preferences…/Playback, make sure „Sound Check“ is ON 3. create a playlist with references of songs in a genre similar to the song you're mixing. (we’ll talk more about picking references in another chapter) 4. “Get Info“ for the song (command + i on the keyboard), chose the „File“-Tab and check the „volume“-value 5 106 5. compare these values to the value that your mix shows when you play it in iTunes. If your references sit around – 7,4 dB, and your own mix is at – 11,3 dB, you’re too loud. If your own mix sits at – 0,4 dB, you need to find about 5dB in volume (maybe the Limiter is not making up for the headroom gain) HERE’S WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT ITUNES SOUNDCHECK AND MASTERING LEVELS: • in iTunes (the app), the „Sound Check“-option that automatically corrects all songs in your libary to similar subjective playback-levels DOES affect the prelistening in the iTunes Store as well – so no „Loudness-war“ happening on iTunes any more really. • ALL Apple-devices have the “Sound Check”-option • levels are not as crazy as they were, and differ from genre to genre SOME INTERESTING EXAMPLE S OF LEVELS… The original album-master of “Billy Jean” gets almost no level-change by iTunes. 5 107 The remastered version of Billie Jean… (picture below) duh, 8,5 dB louder!! That screams “Loudness-War”. The transients are really squashed on this one, and the snare reverb brought up in a very unpleasant way. I can’t listen to this!  Not too bad really for an EDM-record - I've seen many records in this genre at -10 dB and more.  5 108 Big mainstream hit-records don’t need to be squashed!  Another example for a dynamic mainstream No.1-hit. What I’m proposing here is of course not new – mastering engineer Bob Katz has done incredible work in educating audio engineers, and his „k-system“ dB-scales are implemented in a number of plug-ins you should be using to improve your gain-staging. The K-system goes beyond levelling, it even includes standardized listening levels. 5 109 In short, what you can utilise is that iTunes has a very intelligent algorithm that measures RMS, and adjusts ALL tracks in a way that regardless of what song you’re listening to, they will all appear roughly in the same perceived loudness. I think, they did a good job, and I’m planning to release an album on iTunes with just test-material at different levels to find out EXACTLY what happens. The most important thing to know about this is that when your mix is extremely squashed with high RMS and little headroom, iTunes will turn it down and it will end up lower than other tracks. 5 110 FAQ 5 111 When working with acoustic drums, I can find the tone of the kick with the EQ and Analyser BUT how would I tune it (the hole kick file) and if I tune it, wont it be messing with the phase of the tone captured by the OH and ROOM mics? Absolutely correct, if working with a live drum set, you can't tune the kick in the mix - it has to be done before tracking, on the actually drum skin. You can "semitune" acoustic kicks though by setting a resonance and notches surrounding it.   6 112 CHAPTER 06 IT’S ALL ABOUT THE VOCALS CHAPTER 06 IT’S ALL ABOUT THE VOCALS O nce we have created a frame for our mix as described in Chapter 5, it’s time to focus on the vocals - in many cases the most important instrument in the mix. The human voice is the most complex instrument we have to deal with, and you have to understand a number of important concepts when dealing with vocals. 6 113 A QUICK EXCURSION INTO VOCAL RECORDING Let’s have a quick excursion at vocal recording. Mix engineers often have to suffer and repair the results of a bad vocal recording, and it’s worth pointing out common mistakes: 1. TOO MUCH TREBLE AND ESSES Vocal sounds are a matter of trends. For years, the Sony C800G tube microphone has been very popular due to it’s emphasis and fine resolution on higher frequencies. Without a doubt, one of the best mics ever made, but at the same time, depending on the type of vocal, at many times, there is excessive sibilance on the vocal-tracks. A mic that emphasizes the highs is not the main source of trouble here - it’s excessive sibilance pushed into a tracking compressor that creates the problem. I don’t really recommend a tracking compressor at all when trying to achieve a vocal sound with crisp highs. Along with more organic sounding records, recent years brought a more organic vocal sound back, with less emphasized treble in the vocals. 2. NO POP SHIELD If you don’t use a pop shield in front of your vocal mic, chances are you will literally have dropouts in your audio signal. 3. RECORDING IN A VOCAL BOOTH Most small home-made vocal booths are not really properly absorbing the sound across the entire frequency range. All they do is dampening the highs, leaving you not only with a boomy sound, but also with comb-filtering that results in resonances across the mids. Vocals 6 114 sound better recorded in a larger room, and it is a lot easier dealing with a few more reflections from a large room than removing resonances from comb-filtering. 4. USING A TRACKING COMPRESSOR Again, if in doubt, don’t use a tracking compressor - it’s a habit from the analogue tape tracking age. Set your mic-pre and tracking levels carefully, and make sure you have plenty of headroom even during the loudest vocal parts of the song. TUNING Tuning vocals is more like fixing the performance than it is mixing, but since it’s technically possible, it’s part of our repertoire of tools and makes us and our work look better when done at the right places. I you haven’t done it, look into automating the responsetime of your tuning plug-in. When using tuning plug-ins, avoid having all doubles of the same vocal-line tuned. Especially on a backing vocal, if you have two doubled takes, only tune one of them. If you have more than two, only tune half of them, and between the tuned ones, fine-tune them against each other (for example: left BV at -5 cent, right BV at +5 cent). BUILDING THE L E A D V O C A L- C H A I N All of the following, please do at a low listening level. I always use my small portable stereo-speakers for that. Start by leveling the untreated lead vocal so that it sits a little low in the track, just loud enough so you can understand the lyrics and follow the melody. I say this now, and I’ll say it a few more times in this book: keep going back between these building blocks for fine 6 115 tuning. Just as an example, you will need to re-adjust the sibilance once you’ve added the final „attitude“compressor. That goes for each building block. Go back and forth between the building blocks and re-adjust. Also, watch your gain staging - make sure the level that comes in at each building block is similar to the output. This chain has 3 dynamics processors with EQs in between, they are kind of „sharing“ the work that has to be done. None of these building blocks need to do the „heavy lifting“ on their own, each has their own role, and less is more. Bypassing one or more building blocks is an option. Many times you don’t need all of them. 1. CONTINUIT Y Starting with the untreated, „naked“ lead vocal-track, I want you to first understand the concept of having two types of volume automation on a vocal: before the processing chain, and after it. This first one evens out the performance of the singer. You could say it creates the continuity of levels in the vocal that you wished the singer had delivered in the first place. This is something that overlaps and goes back to mix preparation, and there is a fair chance that this is already largely fixed. To confirm this, run the mix, go through the song from start to end and find spots where phrases or syllabels of the lead vocals drop in level, or jump out considerably. Correct these phrases in whole db-values - in other words, don’t go too much into details, don’t draw complex automation curves etc., this is just one small step to even out the lead vocal across the song. 2. SIBIL ANCE Do you feel the sound of the vocal leans towards too much sibilance? Time to use a De-Esser, which is a specialized compressor that has an EQ in the sidechain resulting in reducing passages with a lot of treble between 6 116 5-12kHz to be reduced in level. The frequency that you want to reduce can usually be set, as well as the threshold (minimum level at which it starts working) and the amount of reduction in dB. Use an analyzer to determine at what frequencies the esses are jumping out and reduce them considerably. Alternatively, reducing the esses pre plug-in chain is a more precise way to do this. In Logic I usually isolate the esses to their own regions which I drag to a separate track but same channel strip (so I can select all esses at the same time). I reduce the gain on these regions between 6 - 10 dB, depending on how much the vocal gets compressed in the mix. You want to set them low enough to run below the compressor/s threshold (referring to the compressors to be added later on in the plug-in chain). If you can get a De-Esser to achieve the same - use this technique! You can also completely isolate Esses to another channel strip and EQ/compress them differently. Same goes for breathing noises. 3. WARMTH With the vocal sitting a little low in the track, we now need to develop a feel for what’s missing. We do that by adding frequencies using EQs, starting from the low mids. A. Broad boost between 200 - 500 Hz The Pultec MEQ 5 is usually my first EQ in the vocal chain, but you can simulate these (broad) curves with many stock EQs that come with your DAW. I don’t ever go lower than 200 Hz, and occasionally up to 700Hz. The effect we want to get here is that the vocal gets more weight and warmth in the mix. If the vocal is well tracked, it comes with a lot of that quality in the recording and you may not need to do anything here. This is why people use Neve 1073s and various tube-based 6 117 equipment (from Tube Mics to EQs/Compressors) during tracking. However, a lot of modern vocal recordings sound rather thin, and a nice boost in the low mids fixes it. If you like the character you’re adding with the boost, you can even do a little bit too much off it. We’ll counterbalance it in the next steps. In case the vocal already sounds overly „muddy“ or „boomy“, add a Linear Phase EQ at the beginning of the plug-in chain, locate and remove the frequencies that cause this effect. Watch the interdependence of that - once you’ve removed resonances, you have more leeway again to use that broad Pultecboost again. B. Tube compressor for tone After the boost, insert a compressor for tone - we are not after compression for level automation here, but want to add harmonics on top of the low mid boost and create a sense of glue. The classic Fairchild 660/670 works great here, but don’t limit yourself - many compressors can do the job. Just make sure that it’s not noticeable as compression. Light tape saturation can also work. 4. PRESENCE In a dense mix, this is were we create the frequencies that make the vocal cut through the rest of the instruments. We can go to extremes here, but before you start playing with the mid boost, set up the compressor that follows it right away. It’s needed to tame the mid boosts as they can get very harsh. Often, less or no boosting in the mids is needed in less populated parts of the song, but when the vocals are up against a wall of sound, you will need a musically composed texture of „cut through“ frequencies there. 6 118 A. Various boosts between 1k and 8k (SSL EQ) This is more complicated to get right, compared to creating warmth. Start with an SSL-type EQ and boost the high shelf at 8k +10dB, then pull back again to 0dB and find a great setting for it somewhere in the middle. Try switching between BELL and SHELF characteristics (BELL will just boost around the set frequency, while shelf also includes all frequencies above. If 8k is boosting sibilance too much, go a tiny bit lower. Continue by using the HMF band to boost at 4k. And the LMF to boost 2k. Move these around until you find a good balance - but keep in mind, not boosting anything is always an option. The goal is to create a cluster of mid-boosts that really becomes one colourful and musical texture of midboosts between 1 and 8k. You can achieve good results with stock EQs of your DAW, but there is a reason why SSL EQs are famous for their musicality in the mids. API, Neve works as well. Not a job for a Pultec. B. Compression. This compressor’s job is to tame the mid-boosts we just created. We want to see it work hard and fast, but it needs to have a lot of musicality to reduce the harshness of the mid boosts. My favorite one is the Gates or Retro Sta-Level, but I also like the LA-3A. The LA-2A and Summit TL-100A can work as well - if in doubt, try a few different ones. The Sta-Level can reduce ridiculous amounts of gain while you won’t notice any pumping, even when compressing 20dB or more. If in doubt, set the compressor to less gain reduction. This is one step in the vocal chain where the quality of the compressor makes a difference in how much you can go to the edge. In general, I love to give recommendations that are inexpensive, but in reality there are situations where highend equipment has the edge. This is similar to equipment for video and photography. On high quality equipment, 6 119 even a random grainy picture all of a sudden has an articistic vintage quality about it. The goal of using this compressor-stage is to create a balance of power between the warmth and presence we created in steps 3 and 4. 5. AT TITUDE Some sort of 1176 compressor can work at this stage, especially if you need the vocal to cut through a dense and/or agressive track. A blue stripe for more harmonics and distortion, or a black face for smoother tones. There are tons of interpretations of the classic 1176 compressor - you can try them all. 6. FINAL TONE AND DYNAMICS CONTROL A. EQ A final EQ can round off highs and mids. I like a Pultec EQP-1a here, to boost at 20Hz, and Attenuate at 20kHz. Your vocals will sound more analogue when you roll off the top end slightly. Both the boost at 20Hz, and the attenuation at 20kHz should not affect the essence of the tone you have created. The boosts can add little bit of weight, and the cut removes top end energy that only hurts at loud volumes. B. Brickwall Limiter When optionally using the 1176 in stage 5, it might add some sparkle, appearing as a mixture of transients and added harmonics, so you can use a limiter at the end of the chain to catch occasional peaks that jump out. ONLY catch ocassional peaks, and set the release time higher than 100ms. A modern digital brickwall limiter works well here. 6 120 IMPORTANT NOTE! 6 121 The plug-in chain outlined above is pretty complex. There is of course the possibility of processing the vocals too much with a signal chain like this. When you want a really natural vocal sound, you might just need 3B (the subtle tube compressor) and 6A (Pultec for basic tone control). A natural vocal sound requires a very good recording though, and we rarely have an influence on that as mix engineers. On the other hand, the plugin chain is designed to be able to deal with any type of vocal, and when the vocal needs to cut through a dense mix, processing is absolutely necessary. However, subtle settings in each plug-in can still cumulate in a drastic overall effect, while retaining the maximum amount of natural tone. PARALLEL COMPRESSION Chapter 8 is entirely dedicated to parallel processing, but it's worth mentioning here - once you really learned to work the vocal chain above, parallel compression will bring your vocal skills to another level: On most songs that have a certain dynamic, and specifically ballads that start soft and end in a big showdown involving an entire band, orchestra, choir backing vocals, etc., I've made the following experience: • the vocal chain for the (light) first verse, that has only a singer with a piano and (maybe) light drums, is found very quickly. A natural vocal sound utilizing 3B and 6A in our chain often works very well. • as the singer hits higher (and louder) notes, I need to add more elements of the vocal chain to control the dynamics, and also to tame certain resonances that come with loud and high notes 6 • on the chorus, especially towards the end, the vocal has to cut trough a wall of sound, and several compressors are working in the chain • the solution for the dilemma are two separate vocal channels: a natural one, and a processed one! • anything between the two is using a mix of those two channels - by automate both levels you can create the right mixture of them for each section or even single notes • use this technique when the singer performs across a wide range of notes, switching into falsetto, shouting, hitting rough rock notes, etc. • just use a separate track for each of those styles, so you can vary settings and create a balance out of them • more details on this are coming in Chapter 8 VOX AGAINST THE WORLD I have worked on songs where the backing track was such a big and dense „wall of sound“, that the vocal would not stick out of the mix, regardless the treatment on the track. There are two secret weapons for that: 1. The Retro StaLevel Gold Edition compressor - while this might be unuseful info for you, as nobody could manage to make a plug-in version of it yet - if you can get your hands on one of these, try the „Triple Mode“ and a mid to fast time constant. It is my ab- 122 solute favorite compressor for lead vocal in a dense mix. The StaLevel is also useful on a lot of other sources, sounds extremely clean and precise, and I’ve seen it compress 30dB without messing with the integrity of the signal! 2. Multiband Sidechaining: there are a bunch of plugins that can do this, the most known one is Waves C6 Sidechain. First check where the lead vocal has it’s energy in the mids, this could be anywhere between 1k and 5k. Find the right frequency by sweeping through those frequencies with an EQ. Don’t use that EQ on the vocal. Feed the vocal sidechain into the multiband Compressor/EQ and set it so that it reduces exactly this frequency broadly but in a subtle way. BACKING VOCALS All Vocals please sing the same song, at the same time! Backing Vocals are a lot easier to deal with compared to lead vocals - they usually come in groups of 3 and more, and they have to sit behind/underneath the lead vocals. Whereas we strive to create a lot of dynamics, and preserve transients on lead vocals, the backing vocals can be more heavily treated. You can even merge several layers of backing vocals into one file for easier handling. However, there is one thing that you can’t be sloppy with and that’s timing! I’m really sorry to reveal this to you now, but you have to zoom into the waveforms, and match the timing of the backing vocals and lead vocal doubles to the lead vocal! 6 123 While there’s several software tools that promise to do this for you, you always have to double check if you want a flawless result: • esses need to sit exactly in sync with where they sit in the lead vocal - otherwise those messy esses will jump out of the mix left and right like the snakes on my favourite movie „Snakes on a Plane“; in addition to that, reduce them in level, they must not interfere with the sibilance of the lead vocal! • breathing noises in backing vocals? pretty useless! You might enjoy the lead singer’s breathing, but not 20 of them! remove them! BACKING VOCAL CHAIN As far as processing, backing vocals are a lot more forgiving. I usually copy and paste the lead vocal chain to the backing vocals as a starting point, then costumize on the following parameters: (the numbers are referring to the plug-in order of the lead vocal chain, which we use as a starting point) 6 124 6 1. Continuity Equally important for the backing vocals - treat same as lead vocals. 2. Sibilance Definitely use a De-Esser - backing vocals should have a lot less sibilance compared the lead vocals. 3. Warmth A. The Pultec-boost Boost at a different frequency relative to the LVboost. If the lead vocal has a „warmth“-boost at 300Hz, try 200Hz or 500Hz. If you have several backing vocals or LV doubles, try to boost them at different points, so that the boosts are spread across a wide range. B. Tube compressor for tone Same as LV, but a bit more gain reduction. 4. Presence. Here’s where we go counter to the boosts of the lead vocal. Reduce the frequencies you have boosted on the LV. A. Reduce where the LV is boosted (SSL EQ) B. Compression Same as LV 5. Attitude = Bypass! 6. Final Tone and Dynamics Control A. EQ. Adjust this while running all vocals. Attenuate the treble even more relativ to the lead vocal. Try to boost at 12kHz or 16kHz to create some „shine“ if applicable to the genre. B. Brickwall Limiter. You can limit a lot more on the backing vocal. 125 FAQ 6 126 Question on filters and eq etc... The question is general but I'll use a high pass filter as an example. Going on older desks and outboard I've used, there was always some bleed that came through the filters, but with advancements and especially in the digital domain the cut is now sonically precise. I generally keep a little of the original there, especially with stems because that's what I've become used to. To me it feels less clinical but also ends up a warmer tone. (or maybe I am imagining it) I even allow a tiny bit of bleed into the vocal tracks! So thinking ITB, and with all the tools there, is there any real danger of being too clinical and is there a better way of avoiding it? What you're referring to as bleed is simply a less step filter (12dB/oct was sort of standard in analogue); in general you did the right thing - however, the harder you compress the signal later on in the plug-in chain, the more important it is to really get rid of the low rumble for example in a vocal, and in any recording made with a mic; you don't want this stuff to come back at you and start triggering the threshold of the compressor. So, yes you could indeed end up with a less warm signal when you cut hard; I personally cut very hard with a 48db/oct linear phase eq plugin, and I go very high with the cut, to the the point where I cut into the lowest note of the vocal. I compensate for that with a Pultec tube EQ emulation as the first stage after that, and boost around the range of the fundamental note (between 200 - 700 depending on the range of the vocal) to bring that warmth back in a very controlled way. When Mixing full album of varied dynamic material - what’s the methodology of achieving a consistent vocal level throughout. Would you start the first mix using the more populated tracks as regards to instrumentation or the more open tracks with just stripped back instruments and use that vocal level for the rest of the album tracks? Start with the more populated tracks, save plugin-chains of your lead vocal and start with a similar setting on the next song. Keep the songs you've already worked on at hand as a reference. 6 127 7 128 CHAPTER 07 CONTINUITY CHAPTER 07 CONTINUITY B efore you create dynamics, you have to create control: we have a good foundation and groove at this point, the central element in our mix - the vocal - is in control, and we can now start defining the levels of all the other elements of the mix. The best place to start is a loud and dense part of the song. If you deal with a song that has a traditional structure, that would typically be the chorus, so loop that and try to find one level for each instrument that works best. There is no particular order in which you build the levels of the mix, you can just bring them all up at the same time and then focus on one instrument at a time, going back and forth. „Before you create dynamics, you have to create control" 7 129 ONCE YOU HAVE ONE PART OF THE SONG WORKING, YOU WILL MOST LIKELY NOTICE THE FOLLOWING ISSUES: Problem 1: The level that works in the chorus might be completely wrong for that same instrument in a different songpart. Solution: if the same instrument has completely different roles in different song-parts, create duplicates of that track, and use a separate track for each „role“. Example: guitar goes from picking in verses to power chords in the chorus. Problem 2: the level is not consistent even within one song-part Solution: this is what this chapter is about - the goal of this chapter is to create a natural continuity in all the sources from start to end. This is similar to the procedure described as „continuity“ on the vocals in chapter 6 - the same will now be done on all elements of the mix. The continuity of ALL elements in the mix is the foundation for balancing our individual levels, and even further treating the individual elements. Important note - we are NOT creating any kind of DRAMATIC automation or dynamics yet - the focus is completely on sections or notes that noticable stick out or drop in an unnatural way. We are correcting and automating levels PRE and POST plug-in chain. PRE is to create a consistent performance, compensating for volume drops in the performance BEFORE building a plug-in chain, or taming parts that jump out. 7 130 By correcting these issues throughout the track, compressors in the signal path will have to work less hard, and will be sounding more natural. The POST plug-in chain automation, which we’re NOT dealing with in this chapter, is to create your dynamics for the song. A gainer plug-in before the automation fader gives you access to the relative level of the entire track - as this is much easier than always correcting the automation. Also, instead of creating automation for the verse guitar (when it’s different ot the chorus guitar), just copy the channel settings and have an extra channel for different song-parts. This chapter is about correcting levels PRE plug-in chain. Once again, run the mix, go through the song from start to end, one track/instrument at a time, and find spots that drop in level, or jump out considerably. Correct these in whole db-values - and again, don’t go too much into details, don’t draw complex automation curves etc., this is just one first step to even out the performance of each instrument. • • • • as always, start „bottom first“ with bass next guitars, or synth pads orchestra-type instruments, strings, brass, etc. sound FX last In general, this is a perfect routine to use your little portable speakers for - with one exception: creating consistency in the level of the bass is the one place in mixing where a quality headphone is really useful. It has to be one that has a great low-end balance I’m personally using a Beyerdynamic DT990 Pro for that. 7 131 Once you’ve done this on all tracks, use the channel faders to find a rough balance for all instruments that you like. CAREFUL LIMITING On the odd occasion where you have reduced a peaking level in a track, and your level correction at the source still sounds like an unnatural jump in level, reduce the peak less so that it still sounds natural. Try a compressor at a 2:1 ratio with the threshold set so it catches only that particular peak. Adjust attack/gain for a natural sound. NULLING YOUR FADERS This is the final step of this Chapter. „Nulling your faders“ means that you end up with all faders in „default“position while retaining the balance you’ve created. We're doing this in preparation of the final mix automation which will follow A LOT later in the process. However, when our channel faders sit at 0dB, overall levels are a lot more easy to manage, as the fader has a much higher resolution around its default-position. Here’s how to do it: 1. Look at the value of each track’s fader, for example „- 21dB or + 2dB“ 2. Insert a gain-plugin as the last plug-in in your chain, and copy the value above. 3. Set your fader to default position (= 0 dB) 4. As you progress with your mix, you might have to go through the "nulling procedure" one more time. 7 132 7 133 8 134 CHAPTER 08 PARALLEL PROCESSING CHAPTER 08 PARALLEL PROCESSING H ave you ever listened to a great mix and wondered how the vocals were upfront and in your face, had tons of attitude and at the same time still sounded natural and relatable? Many times, the secret behind that was Parallel Processing aka Parallel Compression. Philosophically speaking, you combine a number of specialised techniques and technologies to achive one goal - similar to driving a brand-new S 600 Mercedes that is using an endless list of crazy technologies, but most of them you never recognize: the car is fast like a Ferrari, smooth like a Rolls-Royce, comfortable like a sofa, and safer than Fort Knox. You just keep wondering how they did it. „The beauty of Parallel Processing lies in the simplicity of the concept.“ 8 135 AT THE CORE OF IT, HERE’S WHAT PARALLEL PROCESSING IS ABOUT let’s take a Lead Vocal-track for example: 01. Duplicate your original vocal-track, so it playback on two audio channels. 8 136 02. Leave the original version untreat ed (= no plug-ins), but treat the shit out of the duplicated track, e.g. compress it hard, add frequencies that give the vocal some attitude (just as an example – add whatever you’re after). While you’re treating the duplicate, mute the original, and have no mercy – go to extremes with the treatment, to the point where you couldn’t use the signal in the mix on it’s own. 8 137 8 138 03. Turn the duplicated track fully down, then carefully start blending it with the untreated original by slowly bringing the fader up. Use this the way you would add sugar and salt when cooking – it’s about subtly pushing the original signal in a certain direction without affecting it’s integrity and natural dynamics.  That’s really easy to do, right? Congratulations, you’ve just learned Parallel Processing. „Duplicate the track you want to compress. Compress the shit out of A, leave B clean. Mix. HOW TO CHECK IF YOUR DAW SOFTWARE CAN DO THIS The technique of Parallel Processing aka Parallel Compression was first used in the internal circuit of Dolby A Noise Reduction (introduced in 1965). In 1977 it was first described by Mike Bevelle in an article in Studio Sound magazine, and later dubbed “New York Compression”, around the time when mixing consoles started to feature an extensive routing matrix. On the SSL 4000 E/G-Series, which was first introduced in 1979, you simply press any of the channel’s routing buttons, for example Ch. 1 (like shown below on Channel 9) and get a duplicate of your signal through the large fader on the channel you just selected (by choosing Subgroup on that Channel as your input source). 8 139 WHY DOES THIS NOT WORK ON MY DAW? While duplicating a track is something you can do in every DAW, early DAWs had issues with Parallel Processing. People still have trouble with it on some platforms, but it works great in Logic Pro X and most others, and I’ll guide you through the necessary changes in the audio preferences. HERE I S THE PROBLEM: Every plugin you’re adding to a track adds a tiny delay to the signal. Time required for the plugin to calculate the audio. BUT: your DAW has settings in the Audio Preferences that will make sure the software is compensating the exact delay that the plug-ins create – what they do is starting the audio of a track that has a lot of plug-ins ahead of the others, so it comes out exactly in time… If those calculations are not precise, Parallel Processing won’t work, as you’ll get phase cancellation between the two similar signals you’re mixing. Even a tiny delay of one sample will render the technique useless! Today’s DAWs have a feature called “Plugin Delay Compensation”, and you need to make sure it’s activated: 8 140 8 141 To take Logic as an example, we have 3 options for the “Plug-in Latency Compensation”, as Apple calls it: • • • Off (no compensation) Audio and Software Instrument Tracks (compensates Audio and Software Instrument Tracks, but not Auxes or Output Objects) All (compensates everything) I usually use the „Audio and Software Instrument Tracks“Option during Recording & Arranging, and switch to ALL when I’m mixing. The software will now fully timealign ALL Audio Tracks, Software Instruments, Aux Busses and Outputs. Which means that I can use an Aux to send my Original Signal to another Channel Strip, and treat that signal like the duplicated track in the example above. Very similar to how you would do this on an analogue console. Of course, the analogue console does all this without any latency. Which means, you can use all these tricks even during a live recording. To assure that you’re on the safe side, you can do a test with your DAW software. Add a bunch of EQ plug-ins to the duplicate track, but do not EQ the signal (leave the EQs switched in but flat), and invert the phase polarity on one of the tracks – in the picture below I’m using Logic’s “Gain”-plugin: As you can see, the result of playing two similar tracks back (one of them with inverted phase) should be silence on the output – when you reverse the polarity on one of two similar audio tracks, they cancel each other out. 8 142 “The concept of Parallel Processing is to design two or several signal chains of the same source that go for different aesthetic goals” THE PHILOSOPHICAL DIMENSION Parallel Processing is the solution to a problem that I remember experiencing with compressors since the first time I used one in the 80s (a cheap dbx 163X): 1. on extreme compression settings, the signal has great punch, tone and attitude, but at the same time you really can’t use it like that, it just sounds too manipulated and processed. 2. without compression, the audio sounds clean and natural but lacks punch and attitude Parallel Processing takes some weight from the mix engineers shoulder – by separating the clean and compressed audio, the audio-source becomes easier to manage. You start to take more risks during your mix – you can just experiment on an additional parallel-chain for fun. If it doesn’t work – throw it away! You never feel like you’re messing with the original signal. Be careful though - often, when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Parallel Processing is not for all of your signals in the mix - some instruments work well when transients are squashed by compression or limiting. You can’t have too many transients compete with each other in the mix. Examples would be backing vocals, doubled lead vocals, keyboard pads, heavy guitars - on those, transients need to be controlled. 8 143 If you spread a group of guitars or backing vocals over the stereo panaroma, you can contrast a track with strong transients with a double that has „squashed“ transients. The key is to create a healthy balance between excitement and steadyness in your mix. The typical cases that require both at the same time are lead vocals, and drums. PARALLEL PROCESSING ON VOCALS On the first example, at the beginning of this article, I left the original signal completely untreated. That was of course an extreme example to illustrate the principle of parallel processing. While you might not use any compression on your clean (original) signal, you still want to make sure the audio delivers a consistent performance. Never use a parallel chain to be a substitute for automation or other audio housekeeping. Use automation for parts that drop too much in volume, and never forget to do the necessary EQing / filtering (like removing low end rumble or doing some DeEssing). The concept of Parallel Processing is to design two or several signal chains of the same source that go for different aesthetic goals – here are some ideas: A– B– C– D– E– treat for uncolored, natural, dynamic treat for extreme, coloured, saturated, or even distorted. Of course, you can create even more duplicates of your signal that are differently treated – some examples: run through a guitar amp plug-in for distortion separate breathing noises from the actual „tones“ in the vocal, and keep as untreated and natural as possible (use automation to level bits that jump out) create a duplicate specifically to send to Echos and Reverbs 8 144 I like to think of Echos and Reverbs like a blurry shadow on a photography – hence DON’T send to them from your „upfront/punchy“ vocal channel. Create something more cloudy/blurry that has a stark contrast to your direct vocal signal. PARALLEL PROCESSING ON DRUMS I gave you plenty of ideas in the sub-chapter on „Mixing Kicks“. Just a few examples: • create a duplicate to bring out the transient • separate the duplicates into different frequency ranges • use a duplicate to bring out harmonics (check my post on that) Try sending your entire Drum Submix to a Parallel Compression Chain. This can give your drums great stability in the mix, while transients are unaffected. My starting point on the SSL-console has 4 parallel compressors set up. • 1 for the kick • 1 for the snare • a stereo pair for overheads and/or room mics I send to them from an aux send - in my particular case, using the small fader on the SSL as an aux send via the routing matrix. 8 145 9 146 CHAPTER 9 COLORS, DIMENSION + THE DYNAMIC OF YOUR MIX CHAPTER 9 COLORS, DIMENSION + THE DYNAMIC OF YOUR MIX Let’s look back on the what we have tried to achieve in the previous chapters: • improving room acoustics and listening experience that allows for an „objective as possible“ judgement of our mix • creating a well organized mix session in our DAW that assures we can apply our sonic ideas quickly • building a strong foundation for our mix by balancing the low end, and saveguard our creativity by always retaining plenty of headroom • giving special attention to the lead vocals, assure they have a round tone, cut through the mix, and have plenty of attitude • creating continuity throughout the mix • using parallel compression to add weight and impact on our most important elements in the mix We now have a very solid foundation, but the mix still sounds static and one dimensional at this point - which is what we’re working on in this chapter to finalize our mix. 9 147 EQ-ING Here’s something you need to get your head around. We’re mixing MUSIC. Try to see the following in every element of your mix: • fundamental note/tone • harmonics on top of that (often in form of a triad) • a noise component added to that, mainly in the high frequencies The frequencies in your mix should form a smooth texture where the different instruments add up to a rich spectrum of colours. Don’t take this too literally, but think in musical terms when EQing, and keep that in mind while we go through the tools available to create this. Boost frequencies that build a triad, spread wider in the low register, and you can go more narrow in the higher mids. EQ-ing treble is a matter of asking if you want highs on this instrument or not? If yes, how much until they hurt your ears?“ The chart below can help, but always keep in mind, don’t take this too literal. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies Before we have a look at the important types of EQs, and where to use them, know that you will need to use a combination of these to cover all your EQ-needs in a mix. If you are not yet familiar with those classifications, take some time to explore the possibilities of these on different sources. In the context of setting final levels in the mix, which we get to at the end of this chapter, EQs can be used 9 148 in a very basic way. When you level for example a piano or guitar in the mix, this is as simple as having the upper range of the instruments, including the noise component (piano hammer noises, guitar picking noises) sit right in the mix first, and then use a broad EQ between 200 - 400Hz to adjust the lower range of the instrument by boosting or cutting. „PULTEC“-T YPE EQS Probably the EQs I personally use the most in my mixes - the hardware-versions of these are tube-compressors that come in two basic types: 1. the EQP-1 „Program Equalizer“ can boost and reduce bass at the same time (in steps from 20 to 100Hz), and has similar controls plus a bandwidth-parameter for treble (switchable boost for 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, 16kHz, Attenuation/Reduction for 5, 10, 20kHz). 2. the MEQ-1 „Midrange Equalizer“ is an EQ for mids - it has a boost (here called „Peak“) for selectable lower mids (200, 300, 500, 700, 1000Hz), a selectable „DIP“ (reduction) for 200, 300, 500, 700Hz, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7kHz and another boost for high mids (switchable between 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5kHz). Pultec-type EQs are great for shaping tones in a very natural way. It is difficult to get a bad-sounding result out of them. Even when frequencies are fully boosted, the boost still has a smooth and natural character about it. The reason for this are the Pultecs broad EQ curves. Even when you boost below 100Hz, the boost reaches up to 700Hz. While these EQs have their own character, you can learn from them even if you don’t own one. Simply try out broader curves (smaller Q-factors) with the EQ you have at hand. 9 149 The EQ-part of the Pultec consists of „passive“ electronics that reduces gain internally, and the tubes are used for a 2 stage line amplifier to make up for the gain lost in the passive EQ-circuit. There are a couple known variations of these from known manufacturers, and an almost endless number of plug-in versions. While the original hardware-versions are amongst the most expensive EQs you can buy for money, plug-ins are of course a way to use these on pretty much every source in your mix. Note that Pultecs add a very desirable and subtle tube saturation to your signal even when the EQ is set flat. CL ASSIC CONSOLE EQS (SSL, NEVE, API) These are the EQs found on the most popular large format recording consoles from the 1970s until today. You don’t need to own a recording console as all of these are available as hardware from the original manufacturers, for example in the popular 500-series format. Console EQs were designed to be able to shape all kinds of signals. They usually have a shelf EQ for the lows and highs, and 1 or 2 bands or fully parametric EQs for the mids. These can often reach as high or low as the low and high shelf EQs. Today, most people learn about and use them in the form of plug-ins, some of them developed with SSL, Neve or API. I might be a bit simplifying here - but you mainly use these when you want to boost or shape a sound more narrow, or more agoressively than what can be achieved with the Pultec-type EQs. 9 150 LINEAR PHASE EQS 9 151 These are digital EQs, and they were first introduced as super expensive digital outboard boxes for mastering engineers, who have used them for many years. Like everything expensive and digital, it is now available in plug-in form, and for example Logic Pro has a very good linear phase EQ that comes with the software. There is a ton of technical info on linear phase EQs on the web, none of which will help you improve your mix. One thing they all have in common is adding a significant latency to your signal that needs to be compensated by your DAW. This is a problem when using it on live instrument, but not in mixing. As shown in the chapter on parallel compression, just make sure your plugin delay compensation is switched on across all types of audio tracks, and you’ll be fine using it. The reason for the added latency is that instead of „post ringing“ which we see in traditional EQs, the linear phase EQs adds „pre ringing“, which in turn keeps the phase response linear. All you need to know is that the linear phase behaviour makes these sound more neutral and less drastic. They don’t add harmonics and resonances - their effect is totally isolated to the frequency range you have selected. They can be used for boosting and attenuating, both broad and narrow. FILTER S To list filters here is somehow redundant. Filters always come in the package of most EQs, except the Pultectype. You use them to remove frequencies below a certain frequency (HPF = High Pass Filter = high frequencies are „allowed“ to pass) or above (LPF = Low Pass Filter = low frequencies are passing). The most popular application is a HPF on vocals, to remove low rumbling frequency, commonly below 60 120 Hz. 9 On many, if not most of my DAW-channels, I’m using ALL of these EQs at different stages of the plug-in chain. A DIFFERENT LOOK AT COMPRESSORS We all have a basic idea of what a compressor does and how to use it, right? I’ve googled „what does a compressor do?“ and the „top“-results are pretty much all similar but still all wrong. Something along these lines: „Compression controls the dynamics of a sound, it raises low volumes, and lowers high volumes“ If you’ve read a few of my articles, you know that I’m questioning some things – and if necessary hit you with raw data to destroy popular myths ;-) This sub-chapter is about compressors as a tool to shape the tone of a signal via adding harmonics. There might still some level correction involved, but as pointed out in Chapter 7, correcting drops or peaks of level at the source is preferable to using a compressor for that. Personally, I think of different models of compressors in terms of „how they feel“. The choice becomes intuitive, as a compressor imparts a distinct characteristic on a sound, pushes it into a sonic direction. It took me years of practise to develop that feel for certain types of gear. It’s more difficult to develop when you use only plug-ins, but you can still get to similar results with both hardware and plug-ins. The original hardware counterparts are different in that they show a lot more color and distortion when you drive them to extremes. Those extremes helped me to learn the characteristics. 152 9 Since that won’t help you - unless you have access to a studio with a large analogue outboard collection - this post is taking an analytic look into popular compressor plug-ins and their characteristics. TEST S ETUP & PROCEDURE Let’s run some popular compressor plug-ins through a test setup and procedure, then look at what the results tell us! (BTW, I’ll give you the test setup as a Logic-Template for download so you can test your own plug-ins – just subscribe to the newsletter!)  THE TEST OSCILL ATOR IN LOGIC PRO X FEEDS A COMPRESSOR WITH A TEST-TONE • • • • the test tone is a sine-wave (as you know, a sinewave has no added harmonics). we cycle through 55 Hz, 110 Hz, 220 Hz, 440 Hz tones then a sweep from 20 Hz to 20.000 Hz ending the cycle with a 100 Hz tone WE CYCLE THROUGH THIS 3 TIMES, WITH RISING LEVELS 1ST CYCLE • • • Oscillator hits Compressor with - 18 dB of level Compressor Threshold is set JUST BEFORE compression for the compressor NOT to compress (unity gain) 2ND CYCLE • Oscillator hits Compressor with - 12dB of level (6 dB more than on the previous cycle) 153 • Compressor settings stay the same, but of course compression now kicks in!! 3RD CYCLE • • Oscillator hits Compressor with – 2 dB of level (another 10dB added on top of the previous cycle) Compressors settings remain the same, but now hitting compression quite hard! The upper track you can see in the videos is the automation curve for the Test Oscillator’s frequencies and levels, the lower track shows a huge analyzer plug-in after the output of the compressor (using Logic Pro X’s Channel EQ), and that shows as the frequency spectrum in realtime. BTW: – 18 dB in your software is a GREAT average level for your recordings and signals in ALL situations. It assures clean and pristine sound and compatibility with all plug-ins. More on this another time when I hit your head with a bat called GAIN STAGING. Summary: on the first cycle, the compressor doesn’t actually change the level of the signal, on the 2nd cycle there is some compression, and on the 3rd cycle: a lot. Every cycle ends with a 100 Hz tone – that makes it easy to read the added harmonics on the analyzer. 2nd harmonic = 200 Hz 3rd harmonic = 300 Hz 4th harmonic = 400 Hz 5th harmonic = 500 Hz n th harmonic = 100 Hz x n Just for reference, here’s what the test procedure looks like with NO COMPRESSOR inserted in the signal path. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fPChmBi3yKU 9 154 9 As you can see, the analyzer just shows basic sine-tones, with no added harmonics. Music theory and physics calls this is the 1st “harmonic” – but don’t be confused, that is the term for the original frequency of the sine-tone. FAIRCHILD 670 COMPRESSOR (1959) – THE ROYAL HARMONICS ORCHESTRA To give you a proper contrast – here’s what this looks like with a plug-in clone of the legendary Fairchild 670 compressor, as some of you might know, the most expensive and sought after vintage tube compressor on the market. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6IR0nRGjOms I bet you that the designers of this plug-in looked at a spectrum like that forever, and did endless coding and testing until the plug-in matched the original hardware closely. You can already see some harmonics even when the compressor doesn’t compress, but they really kick in the more you compress. Note: the lower the sine-tone, the more harmonics show up – I can count 13 added harmonics in the 3rd cycle on top of the 50 Hz sine tone. When the oscillator reaches 2000 Hz, the Fairchild doesn’t add more harmonics on top, at least not visible anymore in the spectrum.  If you look at the rich harmonics added by the Fairchild, you start understanding how it gives a dull bass-sound or a 808 subsonic kick a richer frequency spectrum. This is very useful as it helps low-end to subsonic sounds to translate better on smaller systems (think laptop, tablet, smartphone, kitchen radio). 155 At the same time, a Fairchild might not be the ideal compressor to purely control volume, because the more you compress, the more it changes the sound of the source. This is not typically what you need if your goal is to level something that is dynamically uneven. On the contrary, you want to make sure that your source is already in control dynamically BEFORE you even hit the Fairchild. There are other ways to achieve a consistent loudness in a performance. Look at waveforms of your recording and just bring the lower parts up in level, reduce loud sections, automate, and a lot of times, a consistent level is what a great performer brings to the table! If your signal is well-levelled and even, you can alter its tone by the amount of drive the signal into compression. I’m almost ready to go into detail on parallel compression at this point – imagine a setup where you’re bring the same low 808 Kick into two mixer channels. The first channel kept unprocessed, the second channel pushed hard into a tube compressor like the Fairchild – the added tube channel will make the 808 come through on smaller systems and adds a nice texture to a sound thats pretty close to a sine-tone. On the parallel channel you can even cut off the low end and just add the harmonics (of course cut off POST compression) – more about that in Part 2 of this article. Essentially, what the added harmonics do is adding frequencies to the original sound that weren’t there before. PUT THE COMPRESSOR IN THE MIDDLE OF THE SIGNAL-CHAIN A typical signal chain around a compressor like the Fairchild would look like this: Source Signal -> Surgical EQ (to remove unwanted frequencies) 9 156 -> Compressor (adding harmonics) -> EQ (for color and tonal balance) PRE COMPRESSION: SURGICAL EQ REMOVES UNWANTED FREQUENCIES It’s very important to put an EQ BEFORE the compressor. Use this EQ to remove unwanted frequencies. Typical example would be a High Pass Filter that removes rumbling impact noise on vocal recordings. Imagine how the Compressor would add harmonics to a rumbling noise at 30 Hz and really bring it out – you don’t want that. Same goes for unpleasant room resonances – find them using a narrow EQ boost then set a small notch to remove them. This so-called „surgical EQing“ works best with „Linear Phase EQs“ – many plug-in manufacturers make them, they don’t add coloring resonances. I like the one that comes with Logic Pro X a lot. POST COMPRESSION: EQ FOR COLOR AND TONAL BAL ANCE Going back to the example of a low 808 subkick, which is a sound that is very similar to the sine-tone used in our test, there would be no point in EQing a pure sinetone, right? You can’t add frequencies that are not there – in contrast to a tube compressor, an EQ does NOT generate any frequencies, it can only adjust the tonal balance of the given frequency-content. With that, we have once again turned common audioknowledge upside down: • Compressors can add color to any frequency 9 157 • EQs are static, all they do is adjust the tonal volume 9 158 That rule is of course not totally holding its own once we look at a few more types of compressors. What we’re interpreting in this article focusses on frequencies and harmonics, which is just one aspect of compressors. The other one is the actual ability of a compressor to level, limit or „grab“ a signal, attributes that all refer to the volume of the sound. UNIVERSAL AUDIO/UREI L A-3A (1969) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dUoaFsZb4R0 The Waves CLA-3A is a plug-in clone of the original Universal Audio LA-3A Compressor/Limiter. In contrast to the Fairchild, it’s a lot better suited for levelling a signal. The LA-3A adds only one harmonic (the 3rd one). The Fairchild and the LA-3A can co-exist in a signal chain. Use the LA-3A to even out levels, then hit the Fairchild. The LA-3A is typically used as leveller for bass, guitars and even vocals. Less suitable for percussive sounds – it’s not following fast enough to control a drum sound. TELETRONIX L A-2A (1965) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F5W-fP-MCno The Waves CLA-2A is a clone of the Teletronix LA-2A. The design is a few years older than that of the LA-3A. It adds more harmonics than the LA-3A, but still a lot less than the Fairchild. Typically used to control bass, backing vocals or laidback lead vocals. A fairly slow and laid-back tube compressor. UNIVERSAL AUDIO 1176 REV. A BLUE STRIPE (1967) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPmKEMYWfS0 The Waves CLA-76 is a clone of the Universal Audio/ UREI 1176. Various revisions were made, the „blue stripe“-version being the first one ever created. Nearly every plug-in manufacturer offers a clone of the 1176. I like the ones made by Waves, and they got their name because Waves developed them with Mr. CLA aka Chris Lord-Alge. The 1176 displays extremely rich harmonics. In comparison to the Fairchild 670, it sounds a lot more agressive and levels superfast. That makes the 1176 very flexible – it can be used on almost any source. Like the Fairchild, the 1176 is a true studio classic and it would be worth writing a dedicated chapter about it. If you have a bunch of those in your rack (or a great plug-in clone in your collection), you could mix an entire project exclusively with those. One of the things it works very well for is making vocals agressive and bring them upfront. You can drive it hard into a lot of compression, and as a result will see a lot of harmonics. It would not be the only compressor in the chain, I’m usually running another compressor for levelling before the 1176. 9 159 SOLID STATE LOGIC SSL E/G-SERIES BUS COMPRESSOR (1977) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vf1daI2SNrg This is of course one of the most famous compressors ever build. Waves teamed up with SSL to create one of the first true emulations of an original hardware, and this plug-in (as part of the Waves SSL-bundle) is now a classic, just like the original SSL 4000E and G-Series consoles. It does – of course – a great job levelling a signal, and adds more harmonics the harder you hit it. The trick with the SSL Bus Compressor is hit compression with your peaks in your finished mix, e.g. the kick drum. What happens is that the SSL „grabs“ and reduces the peaks in a very clever way, while adding harmonics to them. The SSL bus compressor controls the dynamics and makes the bits it compresses more punchy by enriching it with harmonics (almost like compensating for the lost level). This effect has widely been described as mixbus-“glue” and the reason why everybody loves SSL Bus Compressors. SOLID STATE LOGIC SSL E-SERIES CHANNEL COMPRESSOR (1977) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJdCSCbZNVo The SSL Channel Compressor, also a part of the Waves SSL-bundle, adds a healthy portion of bright and agressive harmonics, and is capable of controlling and “grabbing” percussive signals like no other compressor. Widely used by famous mix engineers on Kick, Snare and 9 160 any type of percussion – the SSL gives drum sounds a prominent place in the mix, makes drums punchy and cut through. SUMMIT AUDIO TL A-100A (1984) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V_TxskKMd3I The Summit TLA-100A is a very subtle tube compressor. The original analogue hardware has been used by engineer Al Schmidt as a tracking compressor on many of his Grammy-winning projects, for example on Diana Krall’s vocals, to catch some peaks with light compression during vocal recording. The Summit adds some harmonics when you drive it, and works well on a wide selection of sources with 3 easy settings for both attack and release-time. A very subtle leveler for tracking and mixing. LOGIC PRO X COMPRESSOR (PL ATINUM MODE, 1996) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JLXcXrclbCs This is the original compressor plug-in that came with the first version of Logic, so the design goes back to the mid-90s. It’s actually the ONLY plug-in in our test that does not colour the signal AT ALL. Contrary to all other compressors tested, this is a compressor suitable for applications where you want to iron out the dynamics of a track without adding harmonics. The later versions of this plug-ins (like the current one in Logic Pro X) added a few more modes you can select, and when you switch from the “Platinum Mode” in any of the others (like “VCA”), the plug-in starts adding harmonics, trying to mimic some of the compressors I just introduced. 9 161 U-HE PRESSWERK (2015) 9 162 If you don’t have a huge collection of outboard and/or plug-in compressors, you can start with just one that delivers a broad range of application. I personally very much like u-he PRESSWERK which is currently the only compressor plug-in on the market, where the amount, dynamics and shape of the added harmonics can be set independently from the amount of compression. If you look at the block diagram, you will see that PRESSWERK unites all the features and topologies found in classic 1950 – 1970 compressors, while giving the user full control over these features and clear labels to access these in detail. I can see PRESSWERK becoming popular in audio schools, as there’s no other plug-in that will make it that easy to educate someone about the details of ALL vintage compressors in one plug-in. All of the emulations I’ve tested earlier in this chapter, except one, generated harmonic distortion, and these would usually increase in level the more gain reduction (= compression) you’re applying. With PRESSWERK, you have total control over the amount of harmonics that are added, and the DYNAMICS-control can seamlessly adjust between „depending on the volume of the source material“, and „harmonics always added“. The basic harmonics added look somewhat similar to these of a classic UREI 1176 blue stripe, but the various controls of PRESSWERK’s saturation section can highly customize them, for example apply them either PRE or POST compression, statically or following the dynamics of the material, and you can also balance the spectrum of the harmonics slightly using the COLOR-control which is essentially a „tilt“-type filter/EQ. When you watch the clip, pay attention at me playing with the Saturation-section of PRESSWERK starting at around 1:11min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HCG_H7_v1e4 You can download a demo of PRESSWERK here: http://tinyurl.com/kcbjjky Saturation is of course something that occures - more or less - in all analogue signal processors, not only compressors. It’s worth mentioning a few more „standalone“ boxes/plug-ins that can be used to generate harmonics via saturation. 9 163 TAPE SATURATION 9 164 Reel to reel analogue tape machines - remember those? A magnetic recording „head“ magnetizes a magnetic tape that can run at different speeds. Analogue tape, when pushed with extreme levels, doesn’t distort the same way as a digital converter does. The more you enter the „red zone“ of a tape machine, you get an effect called „tape saturation“. The sound of tape saturation varies of course with the type of tape recorder, width of tape, and tape speed. The classic analogue studio standards by STUDER or AMPEX are still loved for their sound, but rarely ever used these days. Plug-in emulations have come a long way and do a really good job getting this type of sound in your DAW. MIC PRES Microphone Amplifiers or short „mic pre’s“ come in flavours similar to compressors (minus the gain reduction circuit) - they can be build with tubes, transformers, transistors or modern OP-amps, or a mixture of all of these technologies. Some of them can also be used at line-levels, and also make a great colour in your palette - especially if you do vocal recording as well. The various Neve-models come to mind, they are amongst the most legendary studio classics. While the original versions are extremely costly, both AMS Neve and various other companies build stripped-down alternatives such as 500-series modules. The classic Neve 1073 is also widely been modelled as a plug-in. MAGIC CHAINS 9 165 As you expand your knowledge about processing and plug-in chains, I recommend that whenever you have found a combination of settings that works in a mix, save the entire channel strip as a plug-in chain in your DAW. Make sure the name you’re using reminds you about what the application for this preset could be. Over time you will develope a library you can always go back to and further refine. REVERBS AND DEL AYS Most producers have a very basic set of Reverb Sends and Returns in their DAW sessions: a standard reverb (mostly plate or concert hall), one delay for throws, and maybe a small room simulation with early reflections. All the tracks in the arrangement are accessing the same reverb and delay, if needed. Thats totally fine for arranging and producing, but forget that concept in mixing. If you want to create an impression of a 3-dimensional mix, with lots of space and separation, here are some things you need to think about: • • • • you need a huge palette of different reverbs and delays, add to that some modulation FX the reverb you end up with will be a mixture of several reverbs that differ in many ways, from colour and density to reverb time the most important tracks in your mix are accessing completely different reverb and delay sends and returns you need to have banks of different reverbs ready in your DAW template, specialized for different sources like drum room, snare, toms, lead vocals, pads, lead synth, orchestral instrument • • • • group the reverb returns together with the instruments they belong to - if you have a drum subgroup or VCA group, the reverb returns for the drums belong to that, and exclusively to that also, you don’t need to create a new send for every reverb - you can send, for example, to 20 different snare reverbs from „Send 5“, and then just unmute and mute them at the aux return, one at a time, until you find what you’re after; this is a very fast and intuitive process, and gives you the option to use one or several reverbs at the same time, and level their balance at the different reverb returns for subgroups or VCA groups to really work, FX belong mostly exclusively to their sources - if you mute the drum group, you mute all drum reverbs with it, but of course NOT the vocal reverb it’s essential to stay very organized in that respect All of the above probably sounds my mixes are drowning in reverb. Don't be fooled - some of these are very subtle. Also, don't be afraid of long reverb times, but keep them super low in level. Many of these you only hear when you switch them off. Here are some examples for types of reverbs that are useful to have at hand, all at the same time: • most reverbs deliver sounds in categories like plate, chamber, ambience, rooms, concert halls, church, etc. • most classic reverbs (e.g. Lexicon 224, 480, EMT, AMS RMX) are great at less defined, „cloudy“ reverbs, regardless at which reverb time • modern reverb plug-ins and hardware reverbs (Bricasti M7 is my favourite) are great at super-realistic room simulation • plug-ins using IRs (Impulse Response) can do both IRs are basically just samples or „fingerprints“ of the original reverbs or even real rooms 9 166 • What I personally have done over the years was simply try a lot of different reverbs and especially IRs, and everytime I heard something that I liked, I saved the channel strip settings, reverb, EQ and some compression, to a channel strip preset in Logic. Doing this will allow you to keep developing a goto library, and certain reverb chains you can not live without after a while, and these make it to your DAW mix template. Delays also come in many different flavours: • the typical 1/2, 1/4 or 1/8-note delay „throw“, often used on the last word or sylabel of a vocal-line. • short slap-back delay • complex delays with polyrhythmic patterns, or even unpredicted „weird“ stuff happening in the feedback loop Reverbs and delays are to your mix, what a shadow is in a photography, you don’t want them as sharp and shiney as your main object. Most of my delay returns are sending to reverbs as I don’t like them to be a totally dry „sampled“ copy of my original signal. Look at reverbs (and delays) similar to a shadow in a photography, you don't need them 100% upfront, shiny and dynamic, their purpose is to give you a sense of subliminal depth. Compressing them helps that a lot. I also EQ them contrasting to the direct signal for that reason, so if you've worked hard to make your lead vocal upfront, direct and "in your face", you don't want to send your reverb from that direct signal. BTW, this is one reason why older "vintage" reverbs/delays are still popular - they have a low-res, "grainy" feel about them (example Lexicon 224 or AMS DMX1580). Compressing reverbs also makes them more controllable - you can get away with less reverb in the mix, if you compress the reverbs that you are using. 9 167 CREATING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL SOUND 9 168 There are obviously a lot of small details involved, but for a start, get your head around the following concept: 1. 2. important stuff goes to the center: Kick, Bass, Lead Vocals try panning everything else hard left or right Sounds crazy I know. Try panning a guitar hard left, send it to a small room and pan the room hard right. Now bring the reverb a tiny bit more to the center until it feels well-balanced. The second guitar you might have: pan the dry one hard right, send it to another small room (or delay or chorus) and pan the effect hard left. You get the idea… this works for guitars, keyboards, percussions, noise fx, etc. - I use small rooms/chambers/ spaces from the Bricasti M7 reverb for that. There are Impulse Responses for the Bricasti out there - for free, and officially authorized by the guys who designed that reverb. MODUL ATION FX 9 169 re: rhythmic gating, the Tremolo (modulates only volume) in Logic Pro is a secret weapon. I use this all the time on lifeless or over-compressed tracks - brings some subtle movement into them. From pads to static synth basses to heavy guitar chords to backing vocals. You can even make reverbs groove subtly with the beat. SUBGROUPS, FX BUSSES AND ROUTING 9 170 As the number of different reverbs (delays, etc.) you are using grows, you need to keep the routing strictly organized. Using the same reverb on several sources quickly becomes messy. You might need to EQ or compress your main reverb in a certain way to improve its sound on the vocals, but as you have used that same reverb on other instruments you are suddenly affecting the balance and sound of your entire mix. I know it sounds counter-intuitive, but you’re better off separating the reverbs you are using for the different instrument groups, which includes the routing and grouping. On my console, I have a pair of channels dedicated to vocal reverbs, another pair for drum reverbs, and they are assigned to their respective VCA groups. On the drums use pre-fader sends, use the drum fx exclusively for drums, and route their returns to the drum bus as well, and/or put them on the same VCA group. Same goes for parallel compression busses, the sends to them are pre-fader, not following automation, but the returns follow the automation of the source - I do that via the Drum VCA group - you get the added bonus that you can treat the FX returns for each group of instruments separately. We want total control in mixing. STEREO BUS MAGIC? A very popular question… „What’s on your mix bus? Are you using PRODUCT X or PRODUCT Z like I do?“ „All in one“ mix bus processors promised to be the one stop solution since the first TC Finalizer that came out in the 90s. You all know the various modern plug-in equivalents of that, and to a certain degree, they work really well. A quick preset can make a song demo more presentable. Things that are involved in these proces- sors are multiband-compression, stereo processors for more width, psychoacoustic loudness treatment, and of course EQs, compressors, limiters, etc. The disappointing truth is that you really need to make your mix happen before the signals gets to the stereo bus. If the mix is rotten at the core - and I refer you to all the things we’ve looked into from the Chapters 3 to this point, multi-band compression can create more density and loudness, but never solve problems that were ignored in the first place. With that, let’s go through my common mix bus signal chain, and allow me to add that every single processor used here is doing only extremely subtle things. 1. LOUDNESS METER From the very start, embedded in my template, the first plug-in on my mix bus is a loudness meter - it monitors the level of the signal that comes in. We talked about Gain Staging in Chapter 5, so you know what to look for. Also, at this point let me remind you about best A/Bing practise as discussed in Chapter 3: we can A/B between a treated and untreated version of our mix bus, at matched levels. This is essential when working with plug-ins on the mix bus - you might not need ANYTHING here. 2. BL ANK I’m not joking. It’s a blank plug-in slot with no plug-in inserted. Leave it like that because if anything comes up, you can insert whatever you might need later on. 3. MIDRANGE The combination of plug-ins I use here is EXACTLY the same that I’m using on vocal-chains: 9 171 A. Pultec MEQ 5 Remember, this was where on the vocal chain, a Pultec is boosting when „warmth“ is needed. Test if our mix bus lacks anything between 200Hz and 700Hz by switching through the frequencies. Don’t boost anything just because you can. Try the same with the upper band as well - sometimes a subtle boost between 1.5k and 7k adds some energy. On all accounts, I’m talking about a +2 or +3dB boost here at best - which is still a very subtle amount on the Pultec. B. Tube compressor for tone I use a plug-in version of the classic Fairchild here, and settings could be called „esoteric“. The gain reductionneedle is hardly ever moving, but when I A/B, it ALWAYS sounds better with the Fairchild in the chain. The category here is mid-range, as it adds harmonics. 4. FINAL TONE AND DYNAMICS CONTROL A. EQ Again the Pultec EQP-1a (don’t confuse it with the MEQ used in step 3!) does a subtle boost here, usually 2dB at 20Hz, and I attenuate treble by 2dB at 20kHz. Another very „esoteric“ setting, the Pultecs on my mix bus are mainly used to add an analogue vibe. B. Final Dynamics I happen to use Slate FG-X as a final bus compressor, and also use the Transient, ITP and Dynamic Perception Controls to fine tune. I am NOT using FG-X as a brickwall limiter, and my signal is leaving this plug-in with the same amount of headroom left as it’s entering it. The „constant gain monitoring“-button is always pressed for that reason. 9 172 C. Linear Phase EQ This is my final control for the overall frequency curve of the mix. I usually add a very broad and subtle boost on the bass. And one more time: keep going back between these building blocks for fine tuning. Watch the gain staging! AUTOMATION Let’s go back to a concept that was introduced in chapter 7 - correcting and automating levels PRE and POST plug-in chain. PRE is to create a consistent natural sounding performance, which we already dealt with. The automation we are now working on is the POST plug-in chain automation that creates your dynamic for the song. Of course, even once you start activating the fader automation in your DAW, there will be situations where you need to change the entire relative volume of the track. A simple gain plug-in before the automation fader gives you easy access to the relative level of the entire track - which is a lot easier than always correcting the entire automation. The way this is handled differs slightly between DAWs, and console automation might have other ways to deal with relative levels. Make sure though to find out how to independently deal with relative levels and automation, both POST plug-in chain of course. Another issue we have already dealt with in Chapter 7, but I’ll repeat it here again - if one instrument has completely different levels or settings in different songparts, instead of creating automation for that, just copy the channel settings and have an extra channel for different song-parts. 9 173 9 And… another reference to an earlier chapter: automation is best performed or programmed while listening at low levels on your small portable speaker. Automation is a great place to emphasize the natural dynamics of the song. Let’s face it - on a rock-song, the drummer will hit the drums harder on the last chorus. Keep in mind that this is not totally depending on levels, as more intense drumming will reflect in brighter drum tones. But still, a subtle push in volume on the final chorus can create extra excitement. This is where the final balance and automation of the mix can be compared to car racing, and you will face the same dilemma as the race car driver: you want to drive as fast and risky as possible, without destroying the car. Luckily, with a few safety features in place, automating a mix is still a very enjoyable ride (and much less dangerous compared to car racing). 174 These are the safety features: 9 175 • if you have „nulled“ your faders, like described in Chapter 7, and maintained solid gain staging throughout adding treatment of the individual channels, you have a „unity gain“ default position for your faders, which means there is zero chance to destroying the solid balance you have already created up to this point - you can always go back to start. When you work your automation around the 0dB position of your fader, you have a much broader range to do subtle fader movements. 3dB is still a bit of movement around the 0dB-point - try to perform a 3dB increase when your level sits at -30dB default! Impossible. That goes for both physical faders and visual automation data in your DAW • oh yeah, you have of course saved your project under a new version number on a regular base - so that you can always go back in case your mix gets worse • the stereo bus treatment we’ve setup in this chapter will make sure that your dynamics stay within a certain range. If your bus-compressor has the right setting, it will subtly keep your dynamics within the frame of good gain staging - in other words, if you push signals into the stereo bus with more level, the increased level at the channels will partly be compensated for by the ratio set on the bus compressor. • and one more last time: your portable speakers at low levels will assure that you’re staying in the right frame with your automation With that - go and create excitement in your automation! Go for bold moves! Definitely start learning to automate with faders. Drawing automation with a mouse will never replace your hand on a fader while closing your eyes and listening to the song at low volume. As a final note on automation, know that you will also have to go back and forth between setting levels and EQing. Whenever there is a situation where you feel the track sits great in the mix, but the bottom is to thick or thin, you know where to find the handle for that. The levels of the track are right when you can even hear very subtle level-changes. As long as you can still move the levels of an instrument up and down a few dB, and it makes no difference for the mix, you need to go back to the start of this chapter and use tools other than level to make the signal sit right in the mix. 176 FAQ 177 Order of operations: first EQ and then compression? and why? there is no fix rule for that - before anything else in the signal chain, you remove problem frequencies, any boost you apply via EQ will also sit better in the signal with a tiny bit of compression applied afterwards. Then there are compressors for tone, adding harmonics - they can be followed up by an EQ, to emphasise some of the harmonics that weren't even there before the compressor was in the signal chain. Do you have ideas how to sort out the midrange on a busy mix? vocals: you will have to boost some presence for them to cut through on a busy mix; we’ll discuss in a later lesson how to build the plug-in chain for lead vocals Waves C6 Sidechain works great for side-chaining the mid-band to the vocals; for example when you have some mid-heavy distorted guitars, whenever the lead vocal comes in, the presence of the guitars gets pushed back to make space for the vocals; because only a certain frequency band is affected, the side-chaining is not noticeable in the mix - the weight of the guitars in the mix stays the same / you can apply the same to push back pianos, keyboard pads, string orchestra, etc... if you need to make space in the lower midrange, you can use that same side-chain eq to make space for that; frequency selective side-chaining is only last resort though; ideally every instrument/vocal "sticks out" at a different frequency. For example when stacking harmony/backing vocals do NOT boost the same low mid frequency on all of them, use for example 300Hz for the lowest, 500Hz for the middle one and 700Hz for the high backing vocal; that way you create a nice texture across the mids where all tracks can co-exist. 10 178 CHAPTER 10 STEMS, MASTERING AND DELIVERY CHAPTER 10 STEMS, MASTERING AND DELIVERY Y our mix is done. You’re happy with it and ready to play it to get feedback from the client. I hope you didn’t prematurely send any half-done rough „outtakes“ up to this point – which would be as unprofessional as a chef asking you to come to his kitchen while cooking to check if his soup is „going into the right direction“. Unless the client is personally listening to the mix in the studio, the mix will be most commonly delivered through e-mail, either by sending mp3s, or a downloadlink to an mp3. The first pitfall to avoid is sending the mix to the wrong people, in the wrong order. 10 179 WHO TO SEND THE MIX, AND WHOSE FEEDBACK TO CONSIDER THE CLIENT PAYS The CLIENT is the person or company/organisation PAYING your mix – treat them with the HIGHEST PRIORITY. RESPECT THE ARTIST In case the client paying for your mix is NOT the artist, always BE RESPECTFUL OF THE ARTIST in your communication, ask the client „Do you want me to send this mix to the artist for feedback?“ STAY OUT OF CONFLICTS If the client that pays your mix (e.g. record label, A&R or producer) does not want to include the artist in the conversation, respect that. The client might want to sort all his feedback out with you before getting the artists approval. 10 180 ARTIST CALL 10 181 However, be prepared for the artist to call or e-mail at you any time. In case the artist contacts you… 1. listen to and respect what the artist has to say 2. politely ask the artist to inform the paying client about his feedback 3. wait a few minutes, to give the artist time to consult with his sponsor 4. after not more than 15 minutes, inform the client about the artist feedback 5. offer to consider the artist’s feedback to the paying client – ask „Do you want me to do an alternative version making the changes the artist is asking for?“ If the answer from the client is still a „No“, leave it at that. When the shit hits the fan, you can earn your degree in diplomacy. Take no ones side, STAY OUT OF CONFLICTS. Be like Switzerland, wait until they have sorted out everything. Just don’t wait to send the updated version to the paying client. KNOW THE HIERACHY If the client is a company (like a record label), be aware that there is a 10 182 HIERACHY INSIDE EVERY COMPANY. You could be communicating with a Junior A&R who commissioned your mix, and when you send your mix for feedback, suddenly one of her bosses chimes in (e.g. “A&R director”, “VP of A&R” or the President or CEO, or all of them at the same time…) via e-mail, or even calls you directly. In that case, e-mail both the Junior A&R AND her boss. Put all of them in the first line of the e-mail (not in Cc or Bcc) and in the order of internal hierachy. The higher person in the company ALWAYS overrules the rest. It helps to have good relationships with the people involved, and to have a bit of an idea of everybody’s role within the company. MOM IS CALLING There can be a ton of other people who suddenly come out of nothing and give you input – from the artists mom/dad/uncle to various people inside the record company, even radio stations or radio promoters sometimes call and ask for a change in the mix! If you follow the rules above, and do great work, you’ll be pretty safe. Also keep in mind that when an artist manager is asking you to do a mix, they are representing the artist who is ultimately paying you. Often the manager might deal with the first round of feedback, but the artist will very likely have the final say, so expect them to join at any point. 10 183 E-MAIL DO’S AND DONT’S For delivering the first completed version of my mix, I stick to this template most of the times. 10 NO EXCUSES • NO EXPLANATIONS OR EXCUSES, don’t send the mix unless you’re fully convinced it’s the best you can do! • Act as if this is the final version – reflect this in the name of the file you sent, the first version I am sending to the client is called „ARTIST – Songtitle (Mixed by Marc Mozart)“ • After the first revision, addressing client changes, the name changes to „ARTIST – Songtitle (Mixed by Marc Mozart) UPDATE” • Next one is called UPDATE 2, then UPDATE 3 DON’T BE STUPID AVOID the following names: • bounce_output_1-2.wav (WTF? And don’t ever e-mail a WAV!) • songtitle_mix_version_43 (your internal version # is not the client’s business) • songtitle_final_master (who says it’s final? never call anything a master unless it IS the master) 184 KEEP YOUR ADDRESS BOOK CLEAN 10 185 Before you send the e-mail, add your client with his full name in your computer’s address book. The name you’re given the client in your address book will show in the e-mail your client receives. You don’t want the e-mail of your client to show up in their device as “info@artist-domain.com (Amanda hot huge rack)” or “ar@recordlabel.com (whacky idiot)”. SERIOUSLY! After you’ve sent the e-mail, it is OK to send a reminder after 6-9 hours and it’s also OK to call or text the client the next day if you haven’t heard back from them. After all, your e-mail could have landed in their spamfolder, while it’s totally possible the client was very busy and didn’t find the time (yet) to listen to your mix or write an e-mail for feedback. It is professional to expect timely feedback, however, if it takes longer than you like, there is nothing you can or should do. Just make sure the client has received your e-mail, and wait for the feedback. FEEDBACK: WHAT TO EXPECT Be ready for anything – client feedback comes in many different shades! I recommend to acquire a deep understanding of the different communication styles we find in people. One of the most widely accepted models around communication types is the „DISC“-model, which categorises four main types of communication styles by two critieria: • • Is the person outgoing or introverted? Is the person task-oriented or people-oriented? Here’s an introduction podcast you can listen to online from the very respected management consulting firm Manager Tools. I've been a huge fan of their work for many years, and I promise it’s worth every second looking into it: Manager Tools – Improve Your Feedback With DiSC http://www.manager-tools.com/2006/02/improveyour-feedback The team from Manager Tools had a huge impact on my career, as their podcasts helped me to get my head around dealing with corporate management structures, which is a field that freelancing artists usually massively struggle with. Back to DISC - there is an actual test you can do to determine which style you are, and at the core of all this, you have to develop the skill to adapt your communication (things you say, how you say them, your body language) to ALL the different types of communicators that exist in the world, and specifically those we work with. This is a skill that differentiates the most successful professionals in any field from the ones that struggle – at least when the job includes dealing with people. The first thing you do after receiving e-mail feedback is to carefully read the e-mail a couple of times, and then reply, thank them for their feedback and confirm you understood it, or ask questions if you didn’t. Give them a time-frame of when you’ll be able to get back to them with an updated mix. 10 186 EXAMPLES FOR CLIENT FEEDBACK EXPERIENCED PROFESSIONALS (A&R, PRODUCER) …will get back to you very quickly and e-mail you a list of the most important bullet points. They know what they want and usually, after listening to the mix twice, know what changes they want. This type of feedback is very easy to deal with. You go through the different bullet points and offer a fix or solution to it. Reply to the e-mail in quote-style and explain how you addressed each bullet point. You can stick mostly to technical terms in your response. Above: feedback example of a very experience established artist/producer. 10 187 ARTISTS 10 188 Artists, unless they are very experienced and through a lot of albums, will tend to take a lot more time to consider their feedback. They also tend to listen to the mix many many times, and often respond in great detail with how they feel about the mix. I often get long e-mails with great backround information on how they felt and what they thought when they wrote the song, and how these feelings relate to the current version of the mix. You need to invest time to careful read their feedback and try to break up their prose style of language into executable bullet points of feedback. Make sure to fully address their thoughts and how you translate them into any technical terms of mixing. You can include technical terms, but don’t forget to talk about how and why what you’ve done FEELS that way, “I’ve added a 3D-type of echo with reverb to the Lead Vox in the chorus, to give it that “spacy astronaut feel” you’ve mentioned in your feedback.” EGOMANIC T YPES OF CLIENTS Egomanic types of characters, guess what, they exist in the music industry. “Can you please tilt the lead vocal reverb trapezoidshaped in the depth of the room!” I remember a mix (and production) I worked on, that would end up becoming a Top 5 record for a major pop act. The mix was long approved by pretty much everybody at the label, and there were a lot of people involved from “VP of Marketing” to “Label President”. But one A&R guy who was (kind of) assigned to the record, wanted to keep arguing with me – I think he didnt feel his influence on the mix wasn’t big as his ego yearned for. Anyway, beyond approval by all of his bosses, he kept asking for changes that would not really make a difference (example “move the lead vocal 1 degree left in the stereo field”) and his feedback culminated in the following request: “Can you please tilt the lead vocal reverb trapezoidshaped in the depth of the room!” When he said that on the phone, I had no idea what he meant, but at the same time I knew that I could not openly tell him my thoughts about what type of person I thought he was, and where exactly I’d like him to stick his feedback. I said: “Oh yeah, I know EXACTLY what you mean. That’s great feedback. Let me work on that and get back to you.” After the phone call, I literally ROFLed for a few minutes. Obviously I had no idea what he referred to with “trapezoid-shaped reverb” but I had to find a solution for the dilemma. The lead (rap) vocal that this song had was sounding direct, had impact and whatever “reverb” he was after could only mess it up. I played with the “small room”reverb that was already on it, and (perhaps) added a tiny bit of a pre-delay to it when it suddenly struck me! Emagic’s Logic was at V4.7 at the time and it had a reverb plugin called “Platinum Verb” which had a GUI of the plug-in that would show different shapes of rooms. OH MY GOD! THIS MUST BE IT! THIS IS WHAT THE GUY HAS SEEN SOMEWHERE!!! 10 189 I didn’t actually change anything and certainly did NOT use “Platinum Verb” in the mix, but I sent him an update, called him and said: “I’ve played around with adding a tiny bit of room sound on the Lead Vocal, and I found that the Platinum Verb plug-in sonically does exactly what you’re were after. Have a listen and let me know!” 5 minutes later I had a reply in my mail saying: “Spot on – you’ve nailed it! I love Platinum Verb. Mix is approved!” 10 190 DEADLINES: HOW TO SURVIVE THEM When you’re mixing for a client, a delivery deadline is always part of the process, whether you perceive the deadline as tight or not. ASK FOR A DEADLINE There are cases where a steady client just sends you a Dropbox-Link with the files and no further comment. Make sure to confirm the receipt of the files and try to get an exact deadline from them. I’m not sure what to think of a client who doesn’t give you a deadline, or at least a rough time-frame. It’s not professional. That said, if you have received an advance payment, there is nothing to complain - the money does the talking and says: „Get started.“ WHEN YOU HAVE A LOT OF TI ME There are projects where the deadline is not pressing. Whether the song is part of an album that is nowhere near finished, or other factors are involved („we are still looking for a feature rapper“, „Slash might do a guitar solo on this“ etc.), there is one thing you can do to take advantage of the chilled situation. Do your mix preparation (-> Chapter 3) as soon as you can! That way, you can leave plenty of time between mix preparation and doing the actual mix, which, for all the reasons we discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, will improve and speed up your mix process. 10 191 IMPOSSIBLE DEADLINES Every now and then we get offered a job that comes with what we perceive to be an „impossible“ deadline. I recommend to look at the following aspects: A: amount of work involved B: amount of money paid C: prestige attached to the credit D: quality of the song/production WHEN YOU HAVE NO TIME OK, here you go. Let’s say, after juggling with A, B, C and D, you decided to accept the job. Here’s how to survive: 1. Never skip preparation. Here’s where the top mix engineers in the world are winning the game early. They have world class assistants who can start preparing the mix session while the master mixer has a huge plate of spaghetti. By the time somebody like Chris-Lord Alge arrives at the studio, the session is ready for him to mix, tracks assigned to faders, computers booted, coffee on the table. OK, you’re not that guy… don’t skip your mix preparation though. Yes, go through it a bit quicker than usual, skip assigning nice little icons to your tracks and other OCDrelated stuff, but do it. Consider to do more grouping of tracks in the preparation time than usual. Bounce all those backing vocals to a stereo file, they are not a priority! Same for the 15 shakers. Pan the individual ones hard left or right (you can always make them more narrow if needed) but don’t get lost in them! The less time you have to do the mix, the more premixing you can do during mix preparation. 10 192 10 Same thing during the mix - group more stuff than usual. You can deal with 8 faders when you got 2 hours to do the mix, but you’ll go crazy looking at 80! 2. Don’t work through the night Don’t work through the night, don’t change your sleep pattern. It will mess up the next few days. If you really need more time, sleep less, but sleep. Even one or two hours of sleep aka "power nap" can make a huge difference. 3. Take regular breaks Taking a quick 10 min walk every 2-3 hours, picking up a coffee to go, and especially having your lunch and dinner at your usual times is essential when in a tight deadline. Don’t get sloppy though, a tight deadline is like preparing for the world cup. 4. Keep in touch with the client The client likes and needs reassurance that you’re on schedule. A quick message or call helps them to keep calm. Even under a tight deadline, don’t ever prematurely send unfinished mixes. Keeping in touch during the process will also assure that when you’re finally ready for client feedback, they can provide that quickly. Nothing worse than working hard to meet a deadline, and then waiting around forever to get client feedback. 193 PRINTING STEMS 10 194 The so-called „STEMS“ (short form or for "STEreo MixeS") that I’m referring to in this chapter are a collection of audiofiles that, summed together, result in your uncompressed and unmastered Full Mix. Once you have printed stems of your mix, by using these your mix is fully recallable for anybody who has a basic DAW. As a standard, I personally print the following Stems, all with FX except were noted: • • • • • • • • • • • Kick Snare Rest of Drums/Percussion Bass Guitars Keyboard-Pads Keyboard-Leads Orchestral Instruments Backing Vocals incl. LV Doubles LV (Dry) LV (FX only) I print them as WAV-files, in the work sample rate of the mix project. • each of the listed Instruments are recorded as a stereo-file while all other instruments are muted • bypass the compressor on the master bus and everything that follows it in the signal chain • start the recording or bouncing of file exactly 1 bar before the music • leave at least one bar of silence after the end of the music, make sure to not cut any sound off, including reverb tails each starts • This is kind of the minimum setup, as there are certain typical situations for which we will need to access the stems. EXAMPLES: • weeks, months or years after approval of your final mix, changes are requested. • this could go as far as new lyrics, a completely different singer, the song being recorded in a different language, foul language that needs to be edited out (clean versions), etc. • 10 195 • stems are also essential for creating special versions/edits for radio, TV, medleys, megamixes as well as syncs for adverts and movies; if the song you’ve mixed becomes a huge commercial success, you might receive numerous editing requests on a regular base. • I also print stems when a client takes very long to get back to me with feedback and I need to free up the analogue console for another project. This of course only makes sense when your mix is already close to a finished state. In cases like that, I might be doing more stems than stated above, to retain more flexibility for changes. • Don’t forget you can always 100% rebuild parts of your mix using the stems, while completely remixing other parts. Again, a typical example would be to record a version of a song in a different language while keeping the mix balance of the backing track fully intact. • Don’t EVER skip printing stems of your mix. To have them is a regular life saver for me, not to mention that most industry contracts for mixers or producers require you to deliver stems along with mixes and masters. PRINTING MIXES I’ve made it a habit to print the final mixes AFTER I’ve done the stems. Printing stems should be done in realtime to become an additional internal quality control you are listening to the major instrument groups of your mix in solo, and chances are that you are hearing a few minor flaws that you want to fix. Some of these might be things that no one ever notifies when all instruments are playing, but it’s good to have another look at it. 10 196 Many times I print the final mixes from the stems, even when the mix was done on the analogue console. There is a tiny difference in tone and dynamics - the mix summed from the stems usually sounds a bit harder and more direct, and is of course fully recallable from your DAW software. There are even situations when the producer of the song wants to have access to the stems of your mix to do the „final edit of the final version“ of the mix - sounds complicated, but it’s really not. Often some time has passed since the producer sent you his session for mixing, and with a fresh mind the producer changed his mind about some aspects of the song. If that happens, just go along with it - it’s part of being a great team-worker. Anyway, at one point final mixes will be printed, and here are some guidelines for that: • • • use your work samplerate (if that was a high-res rate like 96kHz, print your mixes at that) WAV files don’t include fades at start and end (those are part of mastering) 10 197 MASTERING The most important aspect of mastering is very similar to the separation of production and mix - it’s simply two different people looking at it from different perspectives. You are always sending your client a „mastered“ mix for approval - mastered in terms of normalizing the level with a brickwall-limiter at the end of your stereo-bus. If there’s a mastering engineer involved, he will work with your mix that does NOT have your brickwall-limiter applied and ideally a few dBs of headroom. Anything you have had on your stereo-bus chain during mix is totally fine to stay there (except your final brickwall limiter), but I don’t recommend you take that „extra step“ of mastering your own mix. That is likely to go wrong as you have heard your mix too many times, and the point of mastering is really to have another fresh engineer look at your work - a mastering engineer specialised on the task of optimizing finished stereomixes. The attempt of most mix engineers to master their own albums (or even producers, who mix their own album) mostly goes terribly wrong. If there’s no budget for a mastering engineer, take your mixes as they are, and use your final brickwall limiter that you had on the mix, to correct volumes. Don’t add more than 1 dB of Limiting, compared what worked for you on the mix. You can of course, always reduce volume of some of your mixes, by either reducing the amount of final brickwall limiting, or just lowering volume. Selecting a mastering engineer to work with isn’t easy - I often felt they severely destroyed my mixes. It’s not always your decision though - the client might have 10 198 a goto person, and there is not much you can do, especially if it’s a known mastering engineer who has a strong relationship with your client. It’s a good idea to build relationships with a handful of mastering engineers. With the stems in your pocket, you can always take your mix session to a mastering studio, and get his input on it. Together you can correct a few things and record your mix into his system, and he can continue by mastering your mix while you have a coffee in the lounge. A great way to do final quality control of your mix, and you are building a relationship with a mastering engineer at the same time. DELIVERY Deliver to the client ONLY what they really need. Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong. Before you determine what file-types you are giving to the client, know exactly what the client is planning to do with your mixes/masters. These are things that happen on a regular base: • clients converting mp3s to WAVs to to upload them for digital distribution • clients sending mastered WAVs to a mastering engineer • clients sending random rough-mixes to the label If you know that the digital distributor the client is using is only accepting 16bit WAV-files, ONLY deliver this file-type. Many independent aggregators including The Orchard and Believe Digital only accept 16bit WAV-files for upload, not 24bit WAVs. 10 199 The Orchard also accepts Apple Lossless AACs, and you could create that from a 24bit WAV-file. If you upload to iTunes directly using iTunes Producer, you can of course use 24bit WAV-files, even with high sample-rates. FILES Here’s a complete list of files that I recommend printing once your mix is approved: Unmastered versions, all 24bit WAV: • for delivery to a mastering engineer • bypass brickwall limiter in the 2-bus chain, keep at the very least 1dB headroom • FULL MIX • INSTRUMENTAL • ACAPELLA • optionally: VOCAL UP MIX, VOCAL DOWN MIX Mastered versions, both 16bit dithered + 24bit: • for delivery to a record label or upload to a digital distributor • for red book-compatible audio CDs, 16bit dithered files are required • FULL MIX • INSTRUMENTAL • ACAPELLA • optionally: VOCAL UP MIX, VOCAL DOWN MIX Stems, printed „pre 2bus“ chain: • FULL MIX • INSTRUMENTAL • ACAPELLA • KICK • SNARE • REST OF DRUMS/PERCUSSION 10 200 • • • • • • • BASS GUITARS KEYBOARD PADS KEYBOARD LEADS BACKING VOCALS + LV DOUBLES LEAD VOCALS (DRY) LEAD VOCALS (FX ONLY). Again, I don’t recommend sending all of these to the client. Securly archive these files on several mediums, online and offline, and let the client know you have some optional files archived if ever required. ARCHIVING AND BACKUPS As I just mentioned, consider archiving all the printed files as a part of your job. While technically, it might not be your job, you will be an award winning life-saver everytime you can help your client out with the files. You’d be surprised, how even record labels have sometimes no idea how to get hold of multitrack-files or even stems of some of their biggest hits. CLIENT: „THERE’S ONE MORE THING…“ Some of your clients will come back months, sometimes even years after you’ve mixed their song, and will have all kinds of requests to add or change things to the mix. Sounds crazy, but it’s just business as usual. A song needs an edit for a commercial, or film sync, a foreign language version will be recorded, or some territory’s censorship requires to edit out words, etc. - it happens all the time. If you have followed all of the guidelines in this chapter, you’ll be fine, and most requests take no more than 15 minutes do deliver. 10 201 THE END Thanks for taking the time to study this book. This is actually not the end, as I am inviting you to join the online support group [YOURMIXSUCKS] on Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/1511612519104171/ On the group you can ask specific questions about the book, and I will continue to update the book as your questions are coming in. The goal is to create a complete software compendium on mixing that will stand the test of time. You will receive lifelong updates. Things that are planned are bonus chapters specific to certain DAWs, and versions in Spanish and German. All free updates for licensed users. This is Version 1.0, and you can expect a minor update within a month. Marc Mozart, January 2015 10 202