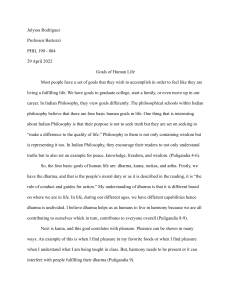

Journal of Dharma Studies https://doi.org/10.1007/s42240-019-00058-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Defining Dharma Yuddha: a Taxonomical Approach to Decolonizing Studies on Hindu War Ethics Arunjana Das 1 # Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract Extant scholarship on Hindu war ethics uses the term dharma yuddha as a synonym of the term, just war, as conceptualized within Christian theo-ethical frameworks developed primarily in the Western academy. Dharma in the term dharma yuddha is presented as equivalent to the term just in just war, and an antonym of adharma or kuta, i.e., unjust. I track the documentary origins of the term dharma yuddha by surveying the usage of this and similar terms in ancient Hindu sources, including the Mahabharata, the Arthashastra, and selected Dharmasastras. I find that the usage of the term dharma yuddha in primary Hindu sources is markedly different from how it is used in contemporary scholarship: the texts mention a range of types of war that are closely related to, but not the same as, the concept of dharma yuddha; this taxonomical richness and complexity is not captured by a binary analytical framework of just versus unjust. In addition, the relationship between dharma and war remains under-explored and merits a more nuanced study than a one-to-one comparison with Christian just war ethics. I, hence, offer a taxonomical model for dharma yuddha, which places it as part of the yuddha family; the model presents attributes of dharma yuddha that are necessary and/or sufficient and which bear conceptual similarities with attributes of other members in the yuddha family. The model presents these attributes in a hierarchical fashion as is reflected in the texts surveyed. The paper makes two types of contributions: firstly, theoretically, it fills a lacuna in the scholarship on Hindu war ethics by presenting a taxonomical and constructive framework to study war that draws from a systematic survey of wars as presented in the Hindu canon; secondly, methodologically, it seeks to decolonize studies on Hindu ethics by studying the texts on their own terms, as opposed to seeing them through the eyes of Christian and, primarily, Western, analytical categories of war. Keywords Just war . Hindu war ethics . Righteous war . Decolonization . Taxonomy * Arunjana Das ad1562@georgetown.edu; Arunjana.das@gmail.com 1 Department of Theology and Religious Studies, Georgetown University, Washington DC USA Journal of Dharma Studies Introduction: Why Theorization sans Comparison? Numerous studies in sociology and political science suggest ways that religion and religious arguments have been used to justify political positions and policies. Some of these policies include decisions related to going to war, conduct of war, and its aftermath. Just war theories remain as the most significant theories used by the modern nation state to justify going to war or using force for political means. In the Western world, these theories have taken form from the writings of Augustine, Aquinas, and other Christian thinkers. In the non-Western world, however, there is a rich corpus of materials that deal with questions regarding war and peace. Ancient Hindu sources on ethics, morality, and law have engaged with such questions and have a great deal of promise and potential in enriching the current corpus of constructive ethics on war and peace. Given the plethora of literature on war and peace in Christian ethical thinking, part of the extant scholarship on Hindu ethics has undertaken a comparative and constructive project that engages this thinking in theorizing on Hindu ethical frameworks on war and peace. Such a comparative approach is laudable in its attempt to engage other theological traditions, and it is a worthy pursuit in its own right. In light of the extant religious diversity and availability of an abundance of theological texts, Clooney (2010) emphasizes the need for interreligious learning by arguing, “Because diversity is an objective feature of the world around us, we need to keep looking outward, learning to be as intellectually engaged as possible in studying it in the small and manageable ways that are possible for us” (7, 8).1 As Yearley (1990), however, argues comparing two traditions can have its “own flourishing and stunted forms” (2). One of its stunted forms involves likely methodological pitfalls that one might encounter where one area of comparison is more developed than the other in contemporary scholarship. Such a pitfall comprises seeing the other through one’s own analytical lenses, and explicitly or implicitly imposing one’s analytical tradition on the other instead of seeing the tradition on its own merit, strengths, and weaknesses. An example of the above is the comparison between just war concepts prevalent in Christian thinking with those apparently present in Hindu ethics. Contemporary scholars have used the term dharma yuddha as a Hindu equivalent of just war citing its usage in the Mahabharata and other parts of the Hindu canon, and embarking on a constructive enterprise that, firstly, engages in a one-to-one comparison with Christian just war thinking, and secondly, based on such a comparison, conceptualizes precepts of what constitutes a dharma yuddha. Doctrines on war and peace within Hinduism and Christianity are certainly similar in their approach to questions regarding when and what kind of war is permissible; concepts of jus ad bellum2 and jus in bello3 prevalent in Christian just war thinking, however, do not neatly travel across to concepts related to justice, righteousness, and fairness when it comes to Hindu thinking on war. More broadly, although there are common themes in the Western conception of justice and 1 Similar to Francis Clooney, I am writing this paper as a Christian and, unlike Clooney, a former Hindu writing on Hinduism. Clooney 2010. Comparative theology: Deep learning across religious borders. John Wiley & Sons. 2 Rules for going to war. 3 Rules of conduct during war. Journal of Dharma Studies the Sanskritic conceptions of dharma, they also differ in ways that are significant and not always reflected in the extant scholarship. Yearley (1990) says, “When I asked myself, or others asked me, what was really at stake in my work, I began to realize just how important it is to develop the virtues and skills that can enable us to compare different visions of the world” (p. 2). Before comparing and contrasting religious ethics on war and peace, there is, hence, a prerequisite in the form of understanding the visions of the world presented by the individual traditions that are the subject of comparison. This paper is, hence, an attempt to, first and foremost, understand the Hindu vision of what constitutes ethics on war. This project is also important in its own right in terms of contributing to answering one of the most enduring questions of the world: How is war to be eliminated, and peace to be made? This question is important not just to persons identifying with faith traditions, but also to those who do not explicitly or implicitly subscribe to any faith traditions. With the above goal in mind, in this paper, I conduct a survey of the various kinds of war that are mentioned in part of the Hindu canon that engages with questions on war and peace. The following texts serve as my primary source documents: the Mahabharata, Arthashastra4, and the following Dharmasastras: Manu-smriti, Vishnusmriti, Yajnavalkya-smriti, Angiras-smriti, Narada-smriti, and Brihaspati-smriti. I situate dharma yuddha among the various types of wars mentioned in the canon and explore the conceptual similarities and dissimilarities between these types. Based on the analysis of the findings from the survey, I propose a constructive conceptualization of dharma yuddha as a taxonomy of necessary and/or sufficient attributes that constitute the yuddha family tree. In terms of methodology, I search for the words yuddha, and its synonyms, vigraha, ahava, and sangrama in my primary sources. In light of the conceptual discombobulation and ambiguity present in the contemporary literature on dharma yuddha, this paper traces the origins of the term back to the primary texts in the Hindu canon. It conducts a survey of different war types in selected texts from the canon and presents a conceptualization of dharma yuddha building on the conceptual clarity and insights provided by the survey. Instead of presenting a static definition, the paper proposes a taxonomic definition that acknowledges the degree to which various conceptual similarities serve as family resemblances in the yuddha family in the canon. This taxonomic definition comprises a hierarchy of attributes based on necessary and sufficient conditions that are gleaned from the context in which yuddha and its synonyms along with the different war types are used. The paper contributes to the project of decolonization in the following ways: firstly, theoretically, it proposes a definition for the term dharma yuddha that takes into account the multiplicity of typologies of war found in the Hindu canon, thereby advancing the extant literature on Hindu ethics on war and peace. Secondly, methodologically, the paper avoids using analytical categories originating in Christian theological thinking, such as just and unjust wars, in coming up with its theoretical framework; instead, the paper builds up on a survey of war as presented in the Hindu canon and uses the original Sanskrit terms for the war types mentioned in the canon. It, hence, avoids drawing a direct equivalent between the Sanskritic conceptualization of dharma and the Western notion of justice. Thirdly, by seeing dharma in its own cultural 4 The earliest known treatise written in the subcontinent on statecraft and grand strategy dating back to 300 BCE. Journal of Dharma Studies context, it snatches the term out of the ivory cage of a Western construction, and lets it fly free in its multicolored conceptual plume. Usage of Dharma Yuddha in Contemporary Literature and Hindu Primary Texts Contemporary scholarship on the conceptualization and articulation of dharma yuddha as an equivalent of just war comprises one or more of the following three intellectual pivots: citing the usage of dharma yuddha in the canon and contrasting the concept with that of kuta yuddha as presented in the Arthashastra, drawing an equivalence between justice and dharma, and constructing a theory on dharma yuddha based on related concepts from the Mahabharata and the Dharmasastras drawing from terms prevalent in Christian just war thinking. Contemporary scholars have presented kuta yuddha as the opposite of a just war and used the term adharma yuddha interchangeably with it. In the following sections, I discuss each of these intellectual pivots, and compare and contrast this usage with how the terms are used in the original texts. Roy (2007) defines dharma yuddha as a “righteous war that is waged in accordance with certain clear-cut rules... A righteous ruler is supposed to wage dharmayuddha in accordance with high moral principles. The laws and customs governing dharmayuddha aim to curtail the lethal effects of warfare and emphasize humanitarian principles. Laws cover such issues as the protection of prisoners of war, avoiding harm to non-combatants, not using the latest weapons, avoidance of nocturnal attacks, etc. The focus is on the fighting of clear-cut battles with the hereditary class of warriors, where the objective is not total annihilation of the enemy. Dharmayuddha involves the use of moderate amounts of force in proportion to the amount of punishment to be delivered to the enemy” (p. 242).5 In proposing this definition, Roy (2007) cites from a range of sources and concepts: Emperor Asoka’s pacifist concept of dhammavijaya (conquest by the spiritual force of non-violence), the Laws of Manu (or Manu-smriti)6, and Kamandikiya’s Nitisara. It is to be noted, however, that the definition proposed by Roy is a constructive one since the texts he cites do not actually explain the term dharma yuddha, although they do articulate ethical principles related to going to war and conduct during war. Subedi (2003) defines the “Hindu concept of just war” thusly, “a war fought in accordance with the laws of war to uphold dharma and justice, rather than a war waged to spread the Hindu religion or to contain the spread of another religion” (p. 348). Subedi, hence, clarifies that dharma yuddha is not to be spoken of in the same vein as jihad since this kind of war is not against people of other faiths or nations; it is a war fought to uphold dharma. These scholars have articulated wars within Hindu ethics to be just only if they follow certain rules, and when these rules get violated, the wars are articulated as unjust, or adharma or kuta. Roy (2007) states, “In Hindu philosophy, there exists a continuous tension between dharmayuddha and kutayuddha. These two terms might 5 Roy, K. 2007. Just and unjust war in Hindu philosophy. Journal of Military Ethics 6, 3, 232–245 One of the Dharmasastras composed at the beginning of the Common Era. The authorship of this text is attributed to the sage, Manu. 6 Journal of Dharma Studies roughly be translated as just and unjust war, respectively... Dharma stands for right conduct in order to maintain cosmic harmony, while kuta means bad or evil” (pp. 232, 233).7 Drawing from Kautilya, the author of the Arthashastra and a well-known ancient thinker of the Hindu canon, Roy (2007) defines kuta yuddha thusly: “waging war through duplicity, treachery, and trickery.” Similarly, Subedi defines kuta yuddha as, “Wars fought with deceptive means, crafty methods, under charms and spells of Maya and Indrajal, and using lethal and deadly weapons” (p. 356).8 In making a contrast to dharma yuddha, kuta yuddha as used by Kautilya in the Arthashastra is, hence, often cited. Roy (2007) states further, “In Kautilya’s theory, kutayuddha is situated at one end of a spectrum that has dharmayuddha at its opposite end.” Subedi (2003) states that there has been a social sanction at various times against prestigious and well-known monarchs from civilized societies engaging in adharma yuddha; only asuras, or demons, are thought to engage in adharma yuddha. Both Roy and Subedi conflate justice, or rather just, with dharma. In addition, some of the related terms, such as prakasa yuddha, or open war, are also conflated with that of righteous war and just war. Quoting Kangle (2000), Roy (2007) states: “Kautilya took pains to define dharmayuddha as prakasa yuddha (open or regular warfare). By this was meant a frontal clash between opposing armies at a place and time decided in advance by the two sides. This sort of warfare was considered to be righteous.” There are certainly common themes in the Western conception of justice and the Sanskritic conceptions of dharma; they, however, also differ in significant ways that the above scholars and others making the above linkage have not considered.9 The Enlightenment views of justice are some of the earliest conceptions of justice in the Western academy. Winthrop (1978) summarizes the Aristotlean view thusly: “distributive justice provides the principle underlying the distribution of goods and honors in a political community; it is the principle embodied in a regime. The general principle, that equal persons must have equal shares and unequals, unequal shares, can be stated with the certitude, clarity, and precision of a mathematical formula. Distributive justice is a proportion. Corrective justice provides the principle applied in courts of law when contracts must be rectified. Here persons are not to be taken into account, but the gain reaped from inflicting loss on a partner in contract is to be equalized by a judge who, again with impressive mathematical rigor, imposes a fitting loss on the one who has gained unjustly” (p. 1204). Contemporary scholars have approached the question of justice in a number of ways, most of which Barry (1991) condenses into the following two broad categories: justice as impartiality and justice as mutual advantage.10 Justice as impartiality which requires an individual to extricate themselves from their contingently given positions and consider perspectives outside of their own position is a Kantian notion—John Rawls and Robert Nozick being more contemporary champions of the notion.11 For 7 Roy, 2007. Ibid. 9 An in-depth discussion on the differences in the ideas of justice and dharma is beyond the scope of this paper but can potentially serve as part of a future research agenda. 10 Barry, Brian. Theories of justice: a treatise on social justice. Vol. 16. Univ of California Press, 1991. Others have provided more approaches to the question of justice. For a discussion of these approaches, see Lebacqz, Karen. Six theories of justice: perspectives from philosophical and theological ethics. Augsburg Books, 1986. 11 See Political Theory (Nov., 1977) for a comprehensive bibliography of literature building up on John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice. 8 Journal of Dharma Studies Rawls, however, as Barry (1991) argues, impartiality is a condition associated with the situation of an individual as opposed to the individual themselves. Summarizing the justice as mutual advantage view, Barry states that justice “represents terms of rational cooperation for mutual cooperation under the circumstances of justice” attributing the idea to both Hume and Rawls (p. 16). Both the above approaches to justice have been around for a long time and have been manifestly built upon and applied in the extant literature.12 Theories on legal rhetoric, jurisprudence, and social justice13 are derivatives of the idea of justice as impartiality. Other, what I would call “second order” theories of justice, for example, theories of environmental justice, combine the notion of justice as impartiality with that of mutual advantage, and explicate the economic, social, political, and moral dimensions of this order of justice.14 Dharma, on the other hand, lacks a precise Western equivalent, though not for the lack of trying. Edgerton (1942) defines dharma as: “propriety, socially approved conduct, in relation to one’s fellow men or to other living beings (animals, or superhuman powers). Law, social usage, morality, and most of what we ordinarily mean by religion, all fall under this head” (p. 151). Other definitions of dharma either comprise various permutations of the above definition or tend to equate dharma to the Western understanding of ethics and ethical conduct.15 Irawati Karve talks about the naturalistic and normative aspects of dharma. The naturalistic aspect entails the necessary attribute or the innate quality of an entity or being whereas the normative aspect comprises one’s social and/or moral duty or responsibility. Whereas ideas of distributive and corrective justice, and impartiality and mutual advantage are encompassed within some of the aspects of dharma, it becomes quickly clear that dharma and justice are two different categories with some similarities. Comparativists, hence, need to see dharma as its own category, and understand the normative and naturalistic aspects and the group of concepts that dharma encompasses. Scholarship in the last few decades had already realized the need to not push dharma into any of the pre-existing Western conceptual boxes. Creel (1972), for example, asks us to be circumspect, and states, “premature identification with Western concepts tends to blind one to the particular multifaceted structure of meanings in the Hindu dharma” (p. 2). Reflecting upon dharma and the Western understanding of ethics, Creel stated most profoundly in 1972: “the lesson to be learned seems to be that one must be continually on guard against taking categories of one culture and imposing them upon another. It would 12 For further discussion of Enlightenment thinkers and their approaches to the question of justice, see Winthrop, Delba. “Aristotle and theories of justice.” American Political Science Review 72, no. 4 (1978): 1201–1216 and Cooper, John M. “Two theories of justice.” In Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 3–27. American Philosophical Association, 2000. See also, for example, Kolm, Serge-Christophe. Modern theories of justice. MIT Press, 2002 and Roemer, John E. Theories of distributive justice. Harvard University Press, 1998. 13 See, for example, Capeheart, Loretta, and Dragan Milovanovic. Social justice: theories, issues, and movements. Rutgers University Press, 2007 and Miller, David. “Recent theories of social justice.” British Journal of Political Science 21, no. 3 (1991): 371–391. 14 See, for example, Liu, Feng. Environmental justice analysis: theories, methods, and practice. CRC Press, 2000. 15 For a discussion on the definitions of dharma, see Holdrege, Barbara A. “Dharma.” In The Hindu world, pp. 225–260. Routledge, 2004. Journal of Dharma Studies appear to be less fruitful to explore dharma as ‘an ethical category’ than to examine the concept in its own cultural context. Perhaps then comparative work, which will be fruitful, may begin. This is simply to say that we do not have some universal framework as to what constitutes ethics, from which lofty pinnacle we may then look down upon Indian and Western and Chinese manifestations. There is a great danger that the interpreter will take some parochial view of ethics-not in this case as moral teachings but as the form of a discipline of inquiry-and treat this as if it were universal. Doubtless we are never free of the tendency, but we are least free when we ignore the problems and most free when we bring some self-consciousness and cultural perspective to our work. Then, after attending as faithfully as we can to what dharma has meant, our understanding of dharma may serve to alter our understanding of ethical categories” (p. 168). The above understanding has perhaps not percolated to comparative scholarship on Hindu and Christian ethics on questions related to war and peace. In this context when scholars conflate justice with dharma, they are not, however, making a mere semantic choice; they are making a choice that carries conceptual luggage, for the term, just, in Christian ethical thinking on war involves very specific precepts. This conflation has, hence, opened the door to making a direct comparison of Hindu ethics with the Christian just war thinking on jus ad bellum and jus in bello.16 In Christian ethical thinking, in order for a war to be called just, it needs to fulfill the requirements of jus ad bellum and jus in bello. Jus ad bellum prescribes rules for going to war, which include legitimation from a just authority, fought for a just cause, having a just or right intention, and used as a last resort. Whereas Augustine saw God as a legitimate authority seeing God’s divine directive as sufficient for going to war, Aquinas saw this legitimacy invested in a prince or a monarch. More contemporary thinking on legitimate authority considers entities, such as heads of nation states and international organizations, serving as legitimate authority as well, especially in light of new challenges in the form of intra-state conflict.17 A just cause can comprise selfdefense, pursuit of the common good, or establishing a “right” order in society.18 In 16 Most Christian norms related to just war can be divided into two categories: rules regarding going to war, also known as jus ad bellum, and rules prescribing norms for conduct during war, also known as jus in bello. 17 As derived from the writings of Augustine and Aquinas. Other scholars have questioned ideas of sovereignty in a post-Cold War world. See Augustine, St. 1887 Contra Faustum Manichaeum, tr. Richard Stathert, pp. 151–365 in Philip Schaff (ed.) The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol. IV. Buffalo: Christian Literature; Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, Q. 40. On War. available at http://www.newadvent. org/summa/3040.htm and Hehir, J. Bryan. “Just war theory in a post-Cold War world.” The Journal of Religious Ethics (1992): pp. 237–257. 18 Augustine had, what John Langan argues, a punitive conception of war, i.e., he saw war as the means not for self-defense, but to set a wrong right. Augustine, in fact, was categorical in arguing that war for selfdefense is not a just war. Augustine differentiated between a “right” or “just” peace and an “unjust” peace. Peace if it is unjust needed to be changed through the use of force. From a Thomistic perspective, however, self-defense is a just cause as long as the means used are proportional to what is needed for self-defense. For Aquinas, defending and preserving the self is natural; the onus is on the natural law of what is just. Selfdefense/self-preservation is aligned with the natural law, and, hence, serves as a just cause for war. Within Thomistic conceptions, seeking the common good is a just cause for war; such a common good could be protecting a state from outside aggressors, or protecting victims of oppression in foreign lands from an aggressive government. Thomistic ideas find resonance in several contemporary debates on just cause. See Langan, John. “The elements of St. Augustine’s just war theory.” The Journal of Religious Ethics (1984): pp. 19–38. Journal of Dharma Studies terms of right intentions, the intended effect should be aligned with moral action.19 Lastly, war should be the last resort after all other means, i.e., diplomatic, economic, and others, have been explored and found to be wanting. 20 Jus in bello prescribes rules for conduct of war, which includes proportionality of force used, and discrimination between combatants and non-combatants. For a war to be just, the amount of force used should be proportionate to what is required in order to subdue the adversary. 21 Lastly, the tactics used in war should make a differentiation between combatants and non-combatants.22 As contemporary scholars have pointed out, all the precepts that constitute jus ad bellum and jus in bello are already present in some shape or form in the Hindu corpus of ethical writings. Where this scholarship treads slippery ground is when these preformed categories of rules of warfare are used to look at how principles of warfare are conceptualized in the Hindu canon. This is on account of the following three reasons: firstly, as my survey of the Hindu canon demonstrates, there is many a type of war betwixt the righteous and the non-righteous that a binary conception cannot capture. Secondly, the conception of just and unjust as it relates to war does not have the same connotations in the Hindu canon as it does in Western, Christian paradigms; a 19 For Augustine, the objective of conducting a just war is the creation of just peace where inner attitudes of citizens are aligned with what God intended and ordained. Aquinas talked about intended and unintended effects, also known as the principle of double effect. Killing someone in self-defense has two effects: selfpreservation and killing the aggressor. As long as the intended effect is aligned with moral actions, it is a lawful act. It is, hence, lawful to kill in self-defense since the intention is self-preservation, which is a natural (and, hence, moral) action. Responsibility of the warring actor to ensure that the action has behind it intentions to produce good consequences and not bad, and the good must be more than the bad side effects. See Aquinas, Thomas, Richard J. Regan, and William P. Baumgarth. On law, morality, and politics. Hackett Publishing, 2003. 20 Most historical and contemporary just war theorists, with a few modern exceptions, are in agreement that war should be the last resort after all peaceful means have been exhausted. O’Brien (1981), for example, argues: “Every reasonable peaceful alternative should be exhausted” (p. 33). Similar to O’Brien, Orend (2000) says: “A state may resort to war only if it has exhausted all plausible, peaceful alternatives to resolving the conflict in question, in particular through diplomatic negotiation” (49). See O’Brien, William Vincent. “The conduct of just and limited war.” (1981), and Orend, Brian. “Jus post bellum.” Journal of Social Philosophy 31, no. 1 (2000): pp. 117–137. 21 Aquinas argues that although it is lawful to kill in self-defense since the intention is self-preservation, which is a natural (and, hence, moral) action, it is, unlawful to use force that is much greater than what is required to defend oneself, and thereby, kill someone when a lesser force would have sufficed for self-preservation. In contemporary thinking on just war, proportionality features as a fundamental principle governing the conduct of war. It arises from the principled notion, as advanced by Aquinas and others after him, that belligerents should not have unlimited liberty in terms of choosing the means and size of damage that they can inflict on the adversary. Modern developments in international law governing use of force across international borders are guided by this principle. See Aquinas, Thomas, Richard J. Regan, and William P. Baumgarth. On law, morality, and politics. Hackett Publishing, 2003, and Gardam, Judith Gail. “Proportionality and force in international law.” American Journal of International Law 87, no. 3 (1993): pp. 391–413. 22 Questions about non-combatant immunity have a genesis in discussions on Aquinas’ principle of double effect applied to war. Ramsey (1976) argues that most Protestant and secular discussions around just war and killing of non-combatants revolve around justification of direct killing of non-combatants in war; “we only have to know that there are non-combatants, not exactly who or where they are, in order to know that warfare should be forces and counter-forces warfare, and attack be limited to legitimate military targets” (p. 68). Whereas a war conducted with the objective of defending victims of aggression can be justified, an objective such as securing freedom for the oppressed cannot. He argues for aggression, in such cases, to be defined in terms of the rival nation’s first resort of arms and/or a challenge by a rival nation to one’s laws and order of peace and justice (p. 90). Only aggression defined in such terms could warrant resort to an armed response. See Ramsey, Paul. “War and the Christian conscience: how shall modern war be conducted justly?” (1976). Journal of Dharma Studies simple translation of just as dharma defenestrates the nuanced relationship that dharma has to war in the Hindu conception and binds it in the straitjacket of a pre-formed, Western terminological and analytical system. Thirdly and related to the last point, dharma, in the entirety of its cosmic significance, bears an intimate relationship to principles of warfare in the Hindu canon. In this context, paying short shrift to the differences in the notions of dharma and justice by engaging in a terminological shortcut without acknowledging or addressing the conceptual consequences can lead to not only analytical frameworks that have no real empirical foundation in the canon, but also a loss of the opportunity to explore the theoretical richness that the canon offers. Ignoring this promise of theoretical enrichment goes against the dharma of the scholar, if you will. The Yuddha Family Tree: a Taxonomical Approach to Conceptualizing Dharma Yuddha Theoretical Framework The universe of war types mentioned in the Hindu canon are as follows: dharma yuddha, suyuddha, arya yuddha, prakasa yuddha, kuta yuddha, and mantra yuddha. Each war type bears a kind of conceptual relationship to at least one other war type; this relationship is, at times, either synonymic or antonymic. The synonyms vigraha, sangrama, and ahava are also used for the word yuddha. In the quest to understand how the canon presents the concept of dharma yuddha in the midst of this taxonomical richness and complexity, the following pitfalls are encountered: firstly, there is a lack of consistency in terms of the conceptual clarity that the canon offers for each of the war types. Whereas a term such as arya yuddha is used in a fashion that makes its meaning and significance relatively clear, for terms such as dharma yuddha and suyuddha, that is not the case. Secondly, one war type may share an attribute that is common to a few others in some shape or form, but this attribute may not be shared by all the war types. Thirdly, the attributes themselves may share a complex relationship with one another that is assumed in the text but not explicitly stated. For example, the concept of fairness has several attributes of its own as used in the canon that may not be explicitly stated but are assumed. This concept may also be assumed to have some sort of a resemblance to concepts such as legitimacy, honor, valor, and duty of a warrior, i.e., raja dharma. In light of the above, I propose that instead of seeking to arrive at an objective and static definition of dharma yuddha, it is more accurate to see it as a war type that is a combination of attributes that it shares, to some degree, to other war types. It is, hence, useful to think about yuddha as a family tree of war types, wherein dharma yuddha and other war types are members. Each of the war type shares conceptual attributes, i.e., family resemblances in Wittgensteinian terms, to one or more war types. This model of the yuddha tree, however, departs from the Wittgensteinian idea of family resemblances in proposing an “attributal hierarchy” for its members. This is key in proposing a conceptualization of dharma yuddha: the conceptual attributes do not have equal weight; some are given more and explicit contextual coverage, and are presented as necessary attributes, whereas others are either implicit, or given less contextual coverage. These latter attributes Journal of Dharma Studies may not be necessary, sufficient, or are sufficient only in combination with other attributes. A careful study of the various contexts within which the terms are employed is, hence, warranted, and teasing out the conceptual attributes presented in the context is key to arriving at a conceptual rubric for these terms. I, hence, offer a taxonomical model for dharma yuddha, which places it as part of the yuddha tree, and present conceptual similarities among members in a hierarchical fashion as part of, what I call, a ladder of attributal hierarchy. It is to be noted, however, that this hierarchy can be inferred from the texts based on their explicit mention and contextual coverage only in case of some of the conceptual attributes and war types, not all.23 War Types in the Hindu Canon: a Survey24 (a) Suyuddha: The term is mentioned more than twenty-seven times in the Mahabharata, and once in the Arthashastra. In most translations, suyuddha is translated as a fair fight, fighting fair, or righteous war. None of the major translations used the term just war for suyuddha, whereas the term righteous war is used for both dharma yuddha and suyuddha. This is an example of where looking at the context of usage is fruitful instead of simply relying on how the term is being translated. In the primary sources, the term is used in the following contexts: fairness in fighting, increasing happiness, winning fame and merit, being righteous, heroic, and sinless, entering heaven, and protecting people. At the end of studies well-learned, battles well-fought, acts well-done, austerities well-observed, happiness increases.25 Suyuddha is translated here as battles well-fought. In other instances, it is translated as a good fight or a fair fight.26 Although the corresponding text does not explain what is meant by a good fight, a fair fight, or a battle well-fought, other sources in the canon, for example, Manu-smriti provide certain postulates of fairness in battle. These postulates extend to how war is started, how it is conducted, and its aftermath. Engaging in a suyuddha is also associated with going to heaven; one who dies fighting in a suyuddha is said to enter heaven. The Pandavas have now disposed their forces in counter array agreeably to what is laid down in the scriptures. Ye sinless ones, fight fairly, desirous of entering the highest heaven.27 23 A broader and deeper study of the canon could potentially lead to the construction of such a hierarchy, but that is outside the scope of this paper. 24 Many thanks to Dr. Brahmachari Sharan, professor in Georgetown University, who not only kindly agreed to guide me on this paper, but also helped me look up Sanskrit terms in the primary texts available online. 25 Mahabharata n.d.-e, Book 5, Section 36, verse 2 26 Suyuddha is mentioned in the following verses in the Mahabharata: 1.128.4; 1.128.18; 3.13.103; 3.171.12; 5.36.52; 5.132.26; 5.165.25; 6.22.2; 7.5.6; 7.16.25; 7.29.33; 7.164. 13; 7.165.13; 8.26.69; 8.55.5; 8.57.44; 8.68.43; 9.4.25; 9.4.33; 9.4.45; 9.11.43 12.25.24; 12.59.46; 12.100.11; 12.138. 12; 13. 120.9* (0603-1); 13.134.57* (15-981); 14.92.13). 27 Mahabharata n.d.-g, Book 6, Section 2, verse 2 Journal of Dharma Studies The Arthashastra, Manu-smriti, and Vishnu-smriti also mention suyuddha in the context of being heroic as a warrior and going to heaven.28 Heroic warriors who lay down their lives in righteous wars will in a moment reach even beyond the worlds attained by Brahmanas desirous of heaven through a multitude of sacrifices, through ascetic toil, and through numerous gifts to worthy recipients.29 In addition, the Mahabharata mentions suyuddha in terms of being sinless and protecting people. That high-souled one, O Karna, achieving great glory and slaying large numbers of my enemies protected us by fair fight for ten days.30 (b) Arya yuddha: The Mahabharat mentions arya yuddha nine times and in two related contexts: wars fought by aryas, kshatriyas or warriors, and wars that are noble or righteous.31 In its articulation in the canon, this bears a conceptual resemblance to dharma yuddha in the sense that this is a war fought by the warrior class, whose dharma is to engage in a righteous war. The text associates the following conceptual attributes to this war type: raja dharma and righteousness as a feature of the war itself. The concept of heroism and valor is also implicitly present in the contextual vicinity of mentions of arya yuddha. The Mahabharata, for example, says: Thou have been told the reason why those heroes (Nara and Narayana)32 are invincible and have never been vanquished in battle, and why also, O king, the sons of Pandu are incapable of being slain in battle, by anybody.33 Another such instance is when Karna, one of the brave commanders and warriors, when challenged to battle says: I tell thee that I am incapable of being frightened by thee in battle with thy words. If all the gods themselves with Vasava with fight with me, I would still not feel any fear, what need be said then of my fears from Pritha and Kesava?34 28 Manu-smriti mentions suyuddha in the following verses: 7.176; 7.190; 7.198; 7.199; 12.46. Vishnu-smriti mentions it in 3.16. Yama and Angirasa do not mention yuddha or any of its synonyms. 29 Arthasastra, Book 10, Section 3, verse 30 30 Mahabharata n.d.-b, Book 7, Section 5, verse 6 31 Aryayuddha or aryam yuddham is mentioned in the following verses in the Mahabharata: 6.68.31; 6.82.30; 7.21.2; 7.77.13; 7.86.11; 7.100.18; 7.164.9; 8.43.46; 12.272.24. 32 Incarnations of Lord Vishnu 33 Mahabharata n.d.-c, Book 6, Section 68, verse 31 34 Mahabharata n.d.-d, Book 8, Section 43, verse 46 Journal of Dharma Studies In the above and other instances when arya yuddha is used, there is, hence, an accompaniment of valor and heroism, mostly implicit, that serves as a conceptual attribute of those who engage in this war type. (c) Prakasa yuddha: The Arthashastra mentions prakasa yuddha in terms of a war that is open. Prakasa is the Sanskrit term for light, or in the open. The defining attribute of such a war is, hence, openness, which the Arthashastra conceptualizes in the context as a war where the time and place are known. The Arthashastra also associates such a war with righteousness. War at a preannounced time and place is however the most righteous.35 In calling prakas yuddha righteous, the Arthashastra presents righteousness in an antonymic relationship to two other war types: kuta yuddha and mantra yuddha. (d) Kuta yuddha: Translated as treacherous fights or covert war, the Arthashastra presents kuta yuddha as the opposite of a righteous war and conducted through treacherous means. The Arthashastra, however, adopts a strategic and realpolitik view in providing a list of tactics oriented toward victory by all means as opposed to victory through only righteous means. When he has the stronger military force, when secret instigations to sedition have been carried out, when precautionary measures have been taken with regard to the season, and when operations are carried out on terrain suitable for himself, he should undertake open military operations; in the opposite case, covert military operations.36 The chapter, On War, in the Arthashastra provides similar guerilla tactics verging on secret, covert, and treacherous fights for the warrior and king. Although 10.3.26 claims that prakasa yuddha is the most righteous, the Arthashastra does not explicitly claim or mention that engaging in kuta yuddha is against raja dharma; one can, however, infer from how raja dharma is conceptualized in the canon that engaging in kuta yuddha is against raja dharma. The text, hence, associates the following conceptual attributes to this war type: synonymic relationship with treachery and deceit, and an antonymic relationship with righteousness as a feature of the war itself and raja dharma (inferred relationship). (e) Mantra yuddha: This war type can be seen as a sub-set of kuta yuddha. It refers specifically to a battle of intrigue, or a war of wits. It is mentioned in the Arthashastra in the context of what a warrior or king is to do if the adversary does not agree to a peace pact. The warrior is encouraged to exhort the adversary to be righteous and exhibit exemplary qualities that are becoming of a warrior in order to constrain the adversary and trick them into leaving their allies and acceding to a peace treaty or alliance. In effect, the text encourages the warrior to employ righteousness as a tool of deception. 35 36 Arthashastra n.d.-c, Book 10, Section 3, verse 26 Arthashastra n.d.-d, Book 10, Section 3, verse 1 Journal of Dharma Studies Under the topic of War of Wits, the text says: Pay attention to what is righteous and profitable, for those who urge you to do things that are reckless, unrighteous, and detrimental to profit are enemies in the guise of allies.37 (f) Dharma yuddha: The term is mentioned three times in the Mahabharata, including once in the Bhagavad Gita. It is also mentioned once in Brihaspati smriti. In most translations, dharma yuddha is translated as righteous war instead of just war. In the Mahabharata, it is used in the context of a war to uphold dharma, and a war that is to be waged by a kshatriya, a warrior or a king. In Brishaspati Smriti, it is used in the context of a prohibition against killing a learned Brahmin from among one’s adversary in the Kali Yuga. Similar to other instances of mentions of dharma yuddha, Brihaspati does not explain what is meant by a dharma yuddha.38 Further, having regard to your own duty, thou shouldst not waver, for there is nothing higher for a Kshatriya than righteous war. (Bhagavad Gita II. 31.)39 The Mahabharata further associates dharma yuddha with fighting fairly. Alas, having summoned thee to a fair fight, Bhimasena, putting forth his might, fractured thy thighs.40 The following conceptual attributes are, hence, used in the context of a dharma yuddha: raja dharma, upholding of dharma as justice and righteousness, fairness, and righteousness as an attribute of the war itself, and going to heaven when fighting bravely and dying in a dharma yuddha. The concept of heroism and valor is implicit in the concept of raja dharma and can be inferred from it. Conceptualizing Dharma Yuddha: a Ladder of Attributal Hierarchy Based on Necessary and Sufficient Attributes From the survey above, the following conceptual attributes of the yuddha tree can be teased out: dharma as duty, i.e., raja dharma, dharma as righteousness and justice, going to heaven, fairness, openness, heroism and valor, and deception, treachery. These conceptual attributes are present, in some degree, in the articulation of at least one of the members of the Yuddha tree in the canon. The two attributes of highest contextual coverage in defining dharma yuddha are dharma as duty and dharma as righteousness and justice. I call them first-order attributes, i.e., attributes that are necessary for a war to be qualified as a dharma 37 Arthashastra n.d.-d, Book 12, Section 2, verse 2 Brihaspati Smriti (n.d). Book 1, Section 23, verse 4 39 Bhagavad Gita n.d.-e, Chapter 2, verse 31 40 Mahabharata n.d.-a., Book 10, Section 9, verse 23 38 Journal of Dharma Studies yuddha. Other attributes which are provided less contextual coverage but are implicitly stated in the context of a dharma yuddha are as follows: fairness, openness, and heroism and valor. I call them second-order attributes, i.e., attributes that may be necessary but not sufficient, or are sufficient in combination with other attributes for a war to be qualified as a dharma yuddha. First-Order Attributes: Necessary Attributes Based on Explicit Contextual Coverage, i.e., Dharma as Duty and Righteousness The Gita begins by describing the battlefield as a dharma kshetra, or the field of righteousness. Dharma as duty and righteousness are given equal weightage in the canon as the term relates to war. In talking about dharma, translated as duty, the canon talks about kshatriya dharma, raja dharma, or the duty of a warrior.41 As the Pandavas and their cousins, Kauravas, are about to engage in war, Arjuna grows despondent while pondering over the indiscriminate loss in lives that the war he was about to fight would bring, and more importantly, a number of lives that are at stake on account of the war, including those of his own cousins, the Kauravas, elders, such as Bhisma, and other loved ones. He sees it as highly immoral to wage war against one’s own near and dear ones, even though they have done evil, and says: Alas, what a great sin are we resolved to commit! ... Why should we not have the wisdom to turn away from this sin?... Only sin shall we incur by killing these evildoers?42 In his despondency, he finds even the killing of evildoers to be sinful. He, hence, asks Lord Krishna: Being bewildered about righteousness, I ask Thee. Tell me for certain wherein lies the good? On hearing this, Krishna replies that as a warrior, it is his righteous duty to fight the war. He should be detached from the fruits of his action and dedicate himself to his duty since as a warrior it is sinful for him to not execute his duty and give in to despondency as result of his attachments to the material reality. Krishna says, “For those who deserve no grief thou hast grieved, and words of wisdom thou speakest. For the living and for the dead the wise grieve not. Never did I not exist, nor thou, nor those rulers of men; and no one of us will ever thereafter cease to exist. Just as in this body the embodied (Self) passes into childhood and youth and old age, so does He pass into another body. There the wise man is not distressed. These bodies of the embodied (Self) who is eternal, indestructible and unknowable, are said to have an end. Whoever looks upon Him as the slayer, and 41 Each of these terms is an inherently complex term with theological, philosophical, social, and political import, which given the scope of the current paper, I cannot do justice to. 42 Bhagavad Gita n.d.-c, Chapter I, verse 45, 39, 36 Journal of Dharma Studies whoever looks upon Him as the slain, both these know not aright. He slays not, nor is He slain”43 The Gita itself does not clearly specify what comprises a righteous war, but available commentaries on the Gita have theorized that protection of innocent people and pursuit of justice could serve as likely goals or attributes of a righteous war. Ramanuja, for example, says: Even considering svadharmam, your own duty, the duty of a Ksatriya, viz battle — considering even that — you ought not to waver, to deviate from the natural duty of the Ksatriya, i.e. from what is natural to yourself. And since that battle is not devoid of righteousness but is supremely righteous — it being conducive to virtue and meant for protection of subjects through conquest of the earth – therefore, there is nothing else better for a ksatriya than that righteous battle.44 It is very clear from the Gita that it is only monarchs or those from the warrior class who can engage in war. It is indeed their dharma to declare a righteous war, when necessary, and fight it.45 Thus, the Gita exhorts the warrior to engage in his duty to fight a righteous war for the sake of the duty itself. The war is righteous because it is against evildoers and in the pursuit of justice. When fighting such a war, the warrior has to practice renunciation in terms of their attachment to the outcomes of their actions. This inner attitude is key to participate and execute the dharma of a kshatriya. In relation to the warrior’s duty, the Gita also talks about Yoga, or discipline, karma, or action; and tyaaga, or renunciation and detachment to the fruits of one’s action. The Gita lays a great deal of emphasis on maintaining this inner attitude of renunciation and detachment to the fruits of one’s action. Krishna says: “Treat alike pleasure and pain, gain and loss, victory and defeat and then get ready for the battle. Thus, you shall not incur sin.”46 “He who is not selfconceited, whose mind is not attached, even though he slays these worlds, he neither slays nor is he bound.”47 Second-Order Attributes: Necessary but Not Sufficient Attributes with Lesser but Implicit Contextual Coverage, i.e., Fairness, Openness, Heroism and Valor, and Going to Heaven Emphasizing the importance of fairness and openness in war, Manu-smriti underscores that fighting should occur only among equals; a more powerful entity is prohibited from declaring war on a less powerful one. Manu is also against any surprise attacks or use of 43 Bhagavad Gita n.d.-d, Chapter 2, verses 12–19 Commentary by Sri Ramanuja of Sri Sampradaya on Gita II. 31. Available at https://www.bhagavad-gita. us/bhagavad-gita-2-31/. 45 Ibid. 46 Bhagavad Gita n.d.-a, Chapter 2, verse 38 47 Bhagavad Gita n.d.-b, Chapter 18, verses 17 44 Journal of Dharma Studies Table 1 Conceptualization of dharma yuddha as a hierarchy of conceptual attributes Conceptual attributes of dharma yuddha 1st order Dharma as duty 2nd order Fairness Dharma as righteousness Openness Heroism and valor Going to heaven weapons by one side that are more powerful than weapons used by the adversary. There are also strict rules on who can fight whom on the battlefield and who can be attacked and how; a warrior is to spare those who surrender or those who are helpless. In addition, there is also a call for the land, artifacts, people, and property in occupied land to be respected. They are not to be harmed, and they are to be allowed to continue their beliefs, traditions, and practices. This is an important aspect of fair play in terms of what happens in the aftermath of a war.48 There is also a strict protocol for initiating war. In the Gita, war is declared by sounding of conch shells, following which the commanders from both the Pandavas and Kauravas side advance toward each other to fight on the battlefield. Kautilya, the advocate of kuta yuddha, however, argues for violating such protocol and using treacherous or guerilla tactics to get the best of the adversary.49 Implicit in the concept of raja dharma are also the concepts of heroism and valor in battle. A warrior is generally expected to follow rules of comportment that conform to what is expected of a righteous king. Part of this heroism in battle is to fight fairly, and to not turn one’s back in battle.50 Fighting according to the arya codes and displaying heroism in battle will lead them to enter heaven; else, they will incur demerit, which will manifest as rebirth. Table 1 below presents a visual illustration of the proposed conceptualization of dharma yuddha. Conclusion In light of the conceptual discombobulation and ambiguity present in the contemporary literature on dharma yuddha, this paper traces the origins of the term back to the primary texts in the Hindu canon. It conducts a survey of different war types in selected texts from the canon and presents a conceptualization of dharma yuddha building on the conceptual clarity and insights provided by the survey. Instead of presenting a static definition, the paper proposes a taxonomic definition that acknowledges the degree to which various conceptual similarities serve as family resemblances in the yuddha family in the canon. This taxonomic definition comprises a hierarchy of attributes based on necessary and sufficient conditions that are gleaned from the context in which yuddha and its synonyms along with the different war types are used. This paper also serves as an attempt to decolonize the scholarship on Hindu ethics by avoiding the use of analytical categories envisaged within a Christian theological framework. A future research agenda could comprise further clarification of the conceptual attributes, and a conceptual mapping of all war types in the yuddha family. 48 The Laws of Manu (1991) translated, annotated, and introduced by W. Doniger with B. K. Smith (New Delhi: Penguin). 49 Arthashastra n.d.-a, Book 10. 50 Manu-smriti n.d., 7.88–89 Journal of Dharma Studies Compliance with Ethical Standards Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. References Aquinas, T., Regan R. J., and Baumgarth W. P. (2003). On law, morality, and politics. Hackett Publishing. Arthasastra (n.d.). Book 12, Section 2, verse 2. Arthashastra (n.d.-a). Book 10. Arthashastra (n.d.-c). Book 10, Section 3, verse 26. Arthashastra (n.d.-d). Book 10, Section 3, verse 1. Barry, B. (1991). Theories of justice: a treatise on social justice. Vol. 16. Univ of California Press. Bhagavad Gita (n.d.-a). Chapter 2, verse 38. Bhagavad Gita (n.d.-b). Chapter 18, verses 17. Bhagavad Gita (n.d.-c). Chapter I, verse 45, 39, 36. Bhagavad Gita (n.d.-d). Chapter 2, verses 12–19. Bhagavad Gita (n.d.-e). Chapter 2, verse 31. Brihaspati Smriti (n.d.). Book 1, Section 23, verse 4. Clooney, F. X. (2010). Comparative theology: deep learning across religious borders. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. Cooper, J. M. (2000). Two theories of justice. In Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 3–27. American Philosophical Association. The Laws of Manu (1991) translated, annotated, and introduced by W. Doniger with B. K. Smith (New Delhi: Penguin). Creel, A. B. (1972). Dharma as an ethical category relating to freedom and responsibility. Philosophy East and West, 22(2), 155–168. Edgerton, F. (1942). Dominant ideas in the formation of Indian culture. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 62(3), 151–156. Gardam, J. G. (1993). Proportionality and force in international law. American Journal of International Law, 87(3), 391–413. Holdrege, B. A (2004). Dharma. In The Hindu world, pp. 225–260. Routledge, Abingdon. Kangle, R. P. (Ed.). (2000). The Kautilya Arthasastra, part III, an english translation with critical and explanatory notes. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidas. Karve, I. (1961). Hindu society-an interpretation. Poona: Deccan College. Kolm, S.-C. (2002). Modern theories of justice. Cambridge: MIT Press. Lebacqz, K. (1986). Six theories of justice: perspectives from philosophical and theological ethics. Minneapolis: Augsburg Books. Liu, F. (2000). Environmental justice analysis: theories, methods, and practice. Boca Raton: CRC Press. Mahabharata (n.d.-a) Book 10, Section 9, verse 23. Mahabharata (n.d.-b) Book 7, Section 5, verse 6. Mahabharata (n.d.-c) Book 6, Section 68, verse 31 Mahabharata (n.d.-d) Book 8, Section 43, verse 46 Mahabharata (n.d.-e) Book 5, Section 36, verse 2 Mahabharata (n.d.-g) Book 6, Section 2, verse 2 Manu-smriti (n.d.) 7.88-89 Miller, D. (1991). Recent theories of social justice. British Journal of Political Science, 21(3), 371–391. Roemer, J. E. (1998). Theories of distributive justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Roy, K. (2007). Just and unjust war in Hindu philosophy. Journal of Military Ethics, 6(3), 232–245. Subedi, S. P. (2003). The concept in Hinduism of ‘just war’. Journal of Conflict and Security Law, 8(2), 339– 361. Winthrop, D. (1978). Aristotle and theories of justice. American Political Science Review, 72(4), 1201–1216. Yearley, L. H. (1990). Mencius and Aquinas: theories of virtue and conceptions of courage. Vol. 2. Albany: Suny Press. Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.