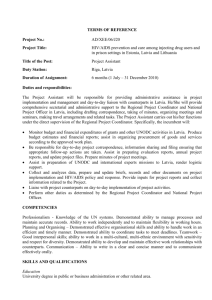

Europe-Asia Studies ISSN: 0966-8136 (Print) 1465-3427 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ceas20 Identity and Media-use Strategies of the Estonian and Latvian Russian-speaking Populations Amid Political Crisis Triin Vihalemm, Jānis Juzefovičs & Marianne Leppik To cite this article: Triin Vihalemm, Jānis Juzefovičs & Marianne Leppik (2019): Identity and Media-use Strategies of the Estonian and Latvian Russian-speaking Populations Amid Political Crisis, Europe-Asia Studies, DOI: 10.1080/09668136.2018.1533916 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2018.1533916 Published online: 07 Jan 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 21 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ceas20 EUROPE-ASIA STUDIES, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2018.1533916 Identity and Media-use Strategies of the Estonian and Latvian Russian-speaking Populations Amid Political Crisis & MARIANNE LEPPIK TRIIN VIHALEMM, JANIS JUZEFOVICS Abstract In this essay, we examine the connections between media use and trust strategies, and the identity development of the Russian-speaking populations in Estonia and Latvia in the context of the political crisis in Ukraine. We argue against the levelling, uniform view of Russian-speaking audiences as being completely under the influence of Russian media and thereby politically identifying themselves with the Kremlin. We present a typology of Russian-speaking audiences, explain how they construct their identities as audience members within these types in times of political crisis, and discuss how this self-identification as audience members shapes the development of broader civic and ethnic identities among the Estonian and Latvian Russian-speaking populations. THE SOVIET-ERA RUSSIAN-SPEAKING SETTLERS AND THEIR DESCENDANTS in the Baltic countries of Estonia and Latvia currently form 33% and 37% of their total populations respectively, numbering approximately 1.48 million people. They constitute a heterogeneous group in terms of citizenship status, language knowledge, immigration generation and degree of ethno-linguistic concentration. Many researchers who investigated the identities of Russian-speaking populations in the Soviet Union successor states in the 1990s forecast a diversity of identity formations among these populations instead of the development of a common group consciousness (Subbotina 1997; Laitin 1998; Lebedeva 1998; Poppe & Hagendoorn 2001; Kosmarskaya 2002; Vihalemm & Kalmus 2010). However, Russianspeaking populations share a common, potentially unifying, communicative base: the Russian language and mass media. The majority of Russian-speakers spend several hours per day watching Russian television channels.1 At the same time, most of them follow these channels in conjunction with local—mainly Russian-language—media channels and, to a lesser extent, Western media outlets (Juzefovics 2017; Leppik & Vihalemm 2017). This work was supported by research funding from the Estonian Research Council (PUT1624). The survey ‘Me. The World. The Media’ (2014) cited in the essay was supported by an Institutional Research Grant (IUT20-38) from the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research. 1 On average, ethnic minority audiences in Latvia spend 2 hours 55 minutes per day watching Russian television channels and 1 hour 5 minutes watching national channels (TNS Latvia, January–June 2016). # 2019 University of Glasgow https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2018.1533916 2 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. The recent Russia–Ukraine conflict has triggered debates about the consolidating impact on identity of propagandistic messages aimed at Russian-speaking audiences in the Baltic states (Rozukalne 2014; Dougherty & Kaljurand 2015; Juzefovics 2017; J~oesaar 2015a, 2015b; Berziņa 2016a, 2016b). In the local media and political discourses, media use among Russian-speaking audiences2 has been seen as having a negative effect on their identity-construction processes—that is, weakening their local civic loyalty and consolidating their identities around Russia—and, hence, is conceived of as a threat to national security. In these discourses, Russian-speaking audiences are often portrayed as susceptible to ‘Kremlin propaganda’. For this reason, the Russian state-controlled television channel Rossiya RTR was twice banned in Latvia: for three months in 2014 and six months in 2016.3 Cheskin (2012) has stated that the influence of Russia should not be ignored but also not overestimated in the identity-formation processes of Russian-speakers in the Baltic states. We agree with this statement and offer a more complex typology of how Russian-speaking audiences construct their identities as audience members and explain the relationship between their strategies of media use and broader identity construction patterns. For contextualising purposes, we first explain the transnationalism approach to the study of migrant identities and provide an overview of the literature on the identity (trans)formation perspectives of Estonian and Latvian Russian-speaking populations, as well as introducing an overview of their media-use strategies based on a secondary analysis of survey data. The original empirical evidence comes from a qualitative focus group study on the quotidian identity construction strategies of audience members. Transnationalism as an explanatory framework Most research on the identity and integration perspectives of Estonian and Latvian Russian-speakers has been conducted from a nation-centric position. Here, the acquisition of Estonian/Latvian language, naturalisation, frequent communication with ethnic Estonians/Latvians, and consumption of national, public broadcast media are taken as the ideal. Consequently, other activities are interpreted in a somewhat utilitarian manner, either as supporting or hindering factors in achieving these goals. Only recently, and in a few studies, has the concept of transnationalism figured in Estonian and Latvian academic discourses (Lazda 2009; Birka 2013; Bela 2014; EHDR 2017). 2 The ethnic make-up of the Russian-speaking minority in Latvia and Estonia is very diverse, including ethnic Ukrainians, Byelorussians and other ethnicities. The mass survey data cited in this essay do not provide statistically relevant information regarding the breakdown of Ukrainians and other ethnic groups. The sample of focus-group participants included people with relatives in Ukraine. However, a detailed discussion of the media use and media-related practices of ethnic Ukrainians in particular is beyond the scope of this essay. 3 For further details see, ‘The Rebroadcasting of Rossiya RTR in Latvia Restricted’, NEPLP, 5 October 2014, available at: https://neplpadome.lv/en/home/news/news/the-rebroadcasting-of-rossiya-rtr-inlatvia-restricted.html, accessed 21 September 2018; ‘NEPLP Restricts Rebroadcasting and Distribution of Rossiya RTR in Latvia for Six Months’, NEPLP, 19 April 2016, available at: https://neplpadome.lv/en/ home/news/news/neplp-restricts-rebroadcasting-and-distribution-of-rossiya-rtr-in-latvia-for-six-months. html, accessed 21 September 2018. IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 3 The central argument of the transnationalism concept is that instead of progressive movement from one society to another, migrants create and maintain parallel ties (business, family, religious and so forth) across individuals’ societies of origin and settlement (Glick Schiller 1992; Guarnizo & Smith 1998; Vertovec 2001). Transnationalism can be conceptualised as a persistently dynamic and fraught condition, where people’s expectations, norms, values and interactions develop in a configuration of two or more socio-political and economic systems (Levitt 2011). Media-use strategies are considered to play a crucial role in the formation of transnational identities. Scholars point to the different possible effect of transnational media practices on the development of broader identity-formation processes of these audiences. According to some previous studies, transnational audience members use ‘interpreting lenses’ based on either the values and perceptions of the society of descent (Vertovec 2004), or on the media culture of the host society (Adams & Ghose 2003; Hepp et al. 2011). Thus, we may hypothesise that, in the longer term, transnational audiences will develop into more diasporic or more localised subgroups. However, other studies provide a counter-argument: they show that transnational audiences are involved in the process of autonomy-seeking by developing ‘double consciousness’ (Golbert 2001): a comparative, critical view of the media content of both sending and receiving societies (Robins & Aksoy 2003). Empirical studies of the Russian-speaking audience in Estonia provide a basis to argue that parallel consumption of Russian, local and sometimes Western media outlets is connected with autonomy-seeking, both as audience members and citizens (Vihalemm & Leppik 2018). The use of different information channels, especially in times of crisis, is rationalised by an awareness of complex interwoven relations of power, with no sole attributable control centre. This raises suspicions regarding the limits of knowledge and the control of messengers, regardless of their geopolitical or institutional origin (Vihalemm & Hogan-Brun 2013a; Kiisel & Vihalemm 2014). Consequently, the exercise of a critical, comparative interpretation of media content can support the construction of multiple, hybrid identities. The studies refer to the possible development of new distinctive (hybrid) identities as a consequence of transnational practices of ‘in-between-ness’ (L€ofgren 2001; Nederveen Pieterse 2003; Elias & Zeltser-Shorer 2006; Glick Schiller & Salazar 2013). However, in times of political crises, the users of media of various geopolitical origins frequently experience essentialising and polarising media discourses. Some authors argue that the maintenance of a hybrid identity, in the context where one frequently faces racist essentialising discourses, is not realistic (Madianou 2006). Indeed, scholars investigating identity changes among young people of Muslim background in Britain have reported that, amidst a backdrop of fear of rising political radicalism, national ‘securitisation’ discourses demolish the hybrid, civic–ethnic–religious identities formed during socialisation. Instead, they encourage the consolidation of essentialising religious identities (Mythen 2012). These reports confirm reactive identity theory, which conceptualises the growth of ethnic resentment and the renaissance of ‘historical’ solidarities and identity symbols as a reaction of members of the minority group to growing hostility and discrimination in the host society (Portes & Rumbaut 2001). 4 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. In this study, we investigate how Estonian and Latvian Russian-speakers reflect on their media-use strategies (their selection of news sources and interpretation of information) in the context of the Ukraine crisis and the accompanying media/ information warfare, something we define here as a clash of ideologically opposed media narratives that may involve political instrumentalisation of media institutions and weaponisation of information operations for the sake of geopolitical gains. In doing so, we aim to forecast their future identity developments. Firstly, we ask how previously heterogeneous information selection strategies change in times of political crisis: towards consolidation around particular information channels or towards diversification of information channels and navigation between various ideological discourses in the media. We assume that there are different strategies to manage the situation and aim to describe these approaches. Secondly, we ask how these different strategies of media use and information retrieval are connected with civic and ethnic identity development. Identity developments and media use among Estonian and Latvian Russian-speaking populations The cultural and political allegiances of Russian-speakers living in post-Soviet successor states and their possible political mobilisation have been subject to extensive academic discussion since the 1990s, when the nation- and state-building process in Estonia and Latvia formally commenced (Rose & Maley 1994; Laitin 1998; Pilkington 1998; Kolstø 2000; Poppe & Hagendoorn 2001; Kosmarskaya 2002, 2011; Commercio 2008; Muiznieks 2010; Cheskin 2016). Much of the scholarly literature has emphasised questions of identity, loyalties and the political mobilisation potential of this group. Since the very beginning of the nation-building process in Estonia and Latvia, researchers have pointed out the accommodationist nature of the social practices of Russian minority members (Rose & Maley 1994; Laitin 1998; Romanov 2000). Although the situations of the Russian-speaking populations somewhat differ in Estonia and Latvia (Muiznieks et al. 2013; Vihalemm & Hogan-Brun 2013b), researchers generally agree that during the two decades of the transition, the ethno-linguistic minority has primarily used individual, not collective, strategies to manage problems of education, language and citizenship. This helps to explain why mass-protest mobilisations have been short-term and rare. It is worth recalling the discussions of the early 1990s, when most scholars anticipated the gradual transformation of post-Soviet, state-led identity into new forms of identities among the Baltic Russian-speakers. In contrast to the Soviet legacy view, some scholars countered this thesis by noting that settlers who came to the Baltic states had already became ‘Balticised’ in Soviet times, and that they largely maintained localised territorial identities and communication networks during the transition period (Melvin 1995). Some authors have pointed to ‘locality’ as a hybrid form of identification: ‘a form of living that is more complex than “community”, more symbolic than “society”; more connotative than “country”; less patriotic than “patrie”’ (Bhabha 1990, p. 292). Local communication networks and self-positioning may also contribute to how individuals make personal sense of the media war and discourses of identification. IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 5 Although there are no directly comparable data, existing research (Vihalemm & Masso 2007; Vihalemm 2008; Tabuns 2010; Vihalemm & Kalmus 2010) suggests that before the onset of the political crisis in Ukraine, there were four basic patterns of identity development among the Russian-speaking populations of Estonia and Latvia: an ethno-cultural (minority) identity, mainly referring to commonly shared and distinctive cultural attributes, such as language and religion; an emerging civic identity, combining elements of ethno-linguistic distinctiveness and territorial/local identity; a diaspora identity, fed by Soviet nostalgia and attachment to Russian imperial attitudes and worldview; and a cosmopolitan identity, constructed from a European or global standpoint and correlated with consumerist values. The survey evidence in Estonia shows that self-identification with the general category of ‘Russians’ (without any specification of country of habitation) increased from 56% in 2003 to 75% in 2014 (University of Tartu 2014). The sense of togetherness with the local ethnic minority group ‘Estonian Russians’ remained the same (52% in both years). At the same time, solidarity with the broader civic category ‘all inhabitants of Estonia’ became less widespread (42% in 2003, and 41% in 2014). A cosmopolitan self-identification with Europeans increased from 18% in 2003 to 28% in 2014. In a similar survey conducted in Latvia in 2010, Latvia’s Russians expressed a far stronger ‘we-group’ sense of belonging to the ethnic minority group ‘Russians living in Latvia’ (68%) than to the broader civic group ‘all citizens of Latvia’ (32%), Russians living in Russia (31%), Russian-speakers all around the world (25%) or to Europeans (16%) (University of Latvia 2010). However, we lack more recent data to judge whether the recent geopolitical tensions have affected the solidarity felt by Latvia’s Russians with various groups. As mentioned above, cosmopolitanism is an important factor in analysing identity developments. As survey data indicate, especially among the younger generation, cosmopolitan or ‘Western’ aspirations are attractive, often including an emancipatory resistance to the restored nation-state construct (Vihalemm & Kalmus 2010). National identity, as constructed by ethnic Estonians and Latvians, has been strongly centred around the language and culture of the ethno-linguistic majority. The motivation to learn Estonian or Latvian language because of the desire to belong to the same group as ethnic Estonians or Latvians is low among the Russian-speakers (Vihalemm 2012). This may enhance the formation of ethno-cultural identity as a defensive minority identity (Castells 1997). Some empirical studies suggest that Russian-speakers have used the same pattern as the titular groups in their identity construction: making the Russian language a central attribute of positive self-esteem, they develop an ‘ethnicised’ identity, identifying themselves as a local ethnic minority (Vihalemm 2008; Vihalemm & Kalmus 2010). The ‘ethnicisation’ tendency has been paradoxically supported by Russia: in the Yel’tsin era, the policies and messages addressed to those who remained outside the borders of the Russian Federation were unsystematic and vague and therefore did not offer Russian-speakers living in Estonia and Latvia a substitute for their lost Soviet identity (Kosmarskaya 2002; Jakobson 2002). Today, Putin’s strong Russian assertiveness is attractive to segments of the Russian-speaking minority but it came fairly late, preceded by a decade of ethnic, language-centred minority identification among Russians living in the Baltic states. Empirical measurements have shown that the 6 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. restructuring of these identities and value structures has developed considerably more slowly than the changes to Russia’s institutional approach (Vihalemm & Kalmus 2010). Thus, it is hard to estimate how the local minority identity that started forming in the 1990s has changed in the context of the more imperialistic ideology of the Russian Federation that was cultivated from the start of the 2000s and, finally, how it is currently developing amidst the on-going geopolitical tensions. One possible path of development is the polarisation of Russian-speaking audiences into more Russia-oriented and more locally oriented subgroups.4 Another path is the formation of common local group solidarity, based on the desire to maintain stability and physical security. This kind of common solidarity requires a certain anti-essentialism and a readiness to accept different, mixed forms of self-identification. Comparative research into individual identity representations of Russians living in the Russian Federation and Estonia shows that Estonian Russian-speakers tend to avoid the use of essentialising categories when defining their ‘Russianness’ compared with Russians living in Russia (Vihalemm & Kaplan 2017). The analysis below is aimed at clarifying how Russian-speaking audiences in Estonia and Latvia explain their information selection and interpretation strategies within the framework of essentialising compared to mixed and negotiable identity constructs: as citizens, ethnic group members and media consumers. The identity developments of Russian-speakers in the Baltic states shape and are shaped by their media usage practices. The spread and development of national language skills among local Russians have proceeded rather slowly in both Estonia and Latvia (Vihalemm & Hogan-Brun 2013b), and the media systems (in terms of institutions, journalistic culture and media use) have remained linguistically rather separated (Vihalemm & Hogan-Brun 2013a). Following the Soviet era, local Russian-language media systems in both countries were (trans)formed by market forces and technological developments. The newspaper and magazine consumption that prevailed in Soviet times and in the early 1990s (Vihalemm 2012) declined quickly. Today the media habits of Estonian and Latvian Russian-speakers are generally characterised by the consumption of broadcast and online media channels, the spread of personalised media devices, and the fragmentation and optimisation of information offered by media enterprises. As noted earlier, according to their media-related practices, the Russian-speaking populations in both countries can be considered transnational. Indeed, 92% of the Russian-speaking population in Estonia claims to follow at least one media channel originating in Russia every day, 89% of Russian-speakers in Estonia claim to use at least one local media channel either in the Estonian or Russian language on a regular basis, and 49% report regularly following at least one non-Russian foreign channel (University of Tartu 2014). Similarly, in Latvia, 59% of its Russian-speakers report regularly using Russian media for news and 48% say the same about Latvian media, while 10% report using Western media as a news source on a regular basis. According to this same survey, 97% of Russian-speakers in Latvia get their news from Russian-language media, both homegrown and Russian-origin, and 54% use Latvian-language media (Berziņa 2016a). The 4 Local orientation here does not necessarily signify pro-Estonia/Latvia or pro-Western political loyalties, but rather deliberation and frequent communication on political events from the perspectives of local security and stability. IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 7 TABLE 1 TRUST IN MEDIA CHANNELS AMONG RUSSIAN-SPEAKING AUDIENCES IN ESTONIA AND LATVIA, 2008 AND 2014 Estonia Trust in media channels Local PSB television channels Russian-language broadcasts on local PSB channels Local commercial television channels (including Russian-language TV5 in Latvia)3 Russian television channels (excluding PBK) PBK Western news media Local PSB radio (including a Russianlanguage channel) Local Russianlanguage news portals Social media Latvia 2008 20111 2014 20152 2008 2014 19% 19% 59% 29% 60%1 25%2 Missing data Missing data 15% 16% 57% 50% 54%1 51%2 74% 71% 70%1 Missing data 55%1 45%2 18%2 26%2 64% Missing data 49% 77% 22.5% 27% 47%1 21%2 43% 34% Missing data 18% Missing data 23% Sources: For Latvia: Human Development Report, University of Latvia/SKDS (2008); ‘Audit of Democracy’, University of Latvia/SKDS (2014); ‘Attitude towards Television’, State Chancellery/SKDS (2014). For Estonia: ‘Me. The World. Media’ (2008, 2014), University of Tartu/Saar-Poll; Integration Monitoring, Ministry of Culture/Emor TNS (2011); Integration Monitoring, Ministry of Culture/Turu-uuringute AS (2015). Notes: 1The data are from Integration Monitoring 2011 survey. Respondents were asked if they trusted the named channel as a source of information on the problems and future of Russian-language schools. 2The data are from the Integration Monitoring 2015 survey. Respondents were asked if they trusted the named channel as a source of information about events in Ukraine. 3In early 2016 the channel was closed due to financial difficulties. Answers were placed on a four-point scale from ‘trust completely’ to ‘rather trust’. Please note that in Estonia questions about trust in information sources were asked in relation to a particular topic: in 2011 about the problems and future of Russian-language schools and in 2015 about the events in Ukraine. media use of Russian-speakers in both countries has been thoroughly analysed elsewhere (Jakobson 2002; Sulmane 2006, 2010; Juzefovics 2012, 2017; Vihalemm 2012; Vihalemm & Hogan-Brun 2013a; Rozukalne 2014; J~oesaar & Rannu 2014; J~oesaar et al. 2014). In order to provide an empirical, quantitative framework for this study we have compiled a comparative picture of the attitudes of Russian-speaking audiences towards different information sources (see Table 1). The answers examine trust and may reflect general evaluations more than the frequency of actual use: some highly valued channels may be used only in extraordinary situations, while otherwise frequently used channels are considered less trustworthy (Vihalemm 2012). Thus the proportions in Table 1 reflect 8 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. imagined ‘normalities’: which channels are more trustworthy and important in forming the ‘personal infrastructure of knowledge’. Over the years, Russian television channels have continued to be trusted sources of news for Russian-speakers in both countries, although Estonian Russian-speakers, in the context of political crisis in Ukraine, tend to be more sceptical of Pervyi Baltiiskii Kanal (PBK), the Baltic version of the state-owned, pro-Putin Russian Pervyi Kanal. We cannot compare the trends in trust of Western news channels as they were not included in the 2008 surveys, but their credibility is low, close to the local public state broadcasting (PSB) channels. Although social media are considered relatively important news sources, social normativity seems to evoke scepticism concerning the information coming from them. Trust in local PSB television channels has recently decreased remarkably; this is likely (partly) due to the poor relationships between the Baltic states and Russia amid the political conflict over Ukraine. The difference in trust in Russianlanguage broadcasts when they cover local educational questions and the Ukraine crisis demonstrates the shift vividly. The low trust in the local public television channel in Estonia indicates that what is seen as ‘state television’, mainly airing Estonian-language content, is regarded with scepticism. This is also the case with Latvia, where, in the eyes of Russian-speakers, the Latvian public television channel LTV is heavily associated with the power elite, much distrusted by both the ethno-linguistic minority and majority (Juzefovics 2017). This, combined with their focus on entertainment, also explains why in Latvia local private television channels, especially the Russian-language TV5, are more trusted than PSB channels. To sum up, according to the analytical categories described by Moring and Godenhjelm (2011, p. 184) in their study of minority media landscapes, the Estonian and Latvian media systems can be characterised as being very close to ‘institutional completeness’, wherein a country provides media services for a minority (language) group, but quite far from ‘functional completeness’, wherein the group depends on these services in its media use (Juzefovics 2017). At present, a self-sustaining condition has formed: the relatively small Russian-language media market (with fewer than 1.5 million consumers) is fractured into various public and private substructures. This is also mirrored on the demand side: the media consumption patterns of Russian-speakers are heterogeneous. It requires considerable (subsidy) capital from the new content producers, such as the ETV þ venture, Estonia’s recently launched public service Russian-language television channel, to enter the market successfully, whereas the fragmentation trend is part of wider global trends and cannot be stopped. Another important trend is that participation in the public information sphere is temporally limited and fragmented: increasingly, people do not follow daily news on conventional media outlets but get their information from social media. For instance, 54% of Estonia’s Russian-speakers do not follow, on a daily basis, national Estonian news through established media organisations (University of Tartu 2014). Thus, information gathering is situational, occurring in an ad hoc manner through following the online posts of friends and acquaintances. Below, we analyse the impact of these patterns on information-seeking and interpretation strategies in the context of the political crisis in Ukraine, accompanied by IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 9 ideological battles in the media. To address these issues a qualitative approach was employed, allowing participants a more active role. We aimed to explain how members of the Russian-speaking audience imagine the power relations between media institutions and state powers, how they discuss journalistic work practices, and how they define the nature of media texts/images: do they consider them to be artefacts constructed by media professionals or reflections of reality? Likewise, we wanted to know how they think and talk about themselves as media consumers, viewing media consumption as a crucial element in identity construction. Methodology Informal interviews were chosen as an appropriate means to look at the issue from the perspective of individual media users. Since the focus of our study was how implicit social norms shape individuals’ identity constructions, focus group interviews were chosen because of their semi-public and interactive nature. In employing this method, we were, however, aware that the participants’ responses would be articulated in a particular context: informal conversations with people of similar ethno-linguistic backgrounds on politically delicate topics. The empirical analysis is based on a series of focus group discussions with members of Russian-speaking communities in Latvia and Estonia from late 2014 to early 2015: a time when the Russia–Ukraine crisis featured prominently in national, Russian, Ukrainian and Western news media. The focus groups were carried out in the capital cities Rıga and Tallinn and also in other cities with significant Russian-speaking minority populations (see Appendix). In Latvia, focus groups were conducted by the local public opinion research company SKDS, who were commissioned by the Latvian authorities amid the Ukraine crisis and in the context of plans by Latvian public television to open a new Russian-language channel. During these focus group discussions, members of the Russian-speaking community were asked about their television viewing habits and their attitudes towards various offerings on television. Our study uses a secondary analysis of transcripts of these group discussions. In Estonia focus groups were carried out as part of a University of Tartu research project. Participants were invited to discuss representations of the Ukraine crisis on the basis of different texts, and to reflect on their news media practices more generally. In both countries, the main focus was on informants’ media practices and media-related perceptions: namely, how Russian-speaking audiences make sense of news media institutions and their messages and, equally important, how these audiences position themselves as media users. We are aware of the limitations of a cross-country comparative study of the kind presented in this essay. We acknowledge that given the differences in fieldwork design, as well as other, more general differences between the Latvian and Estonian cases, data from both countries are not directly comparable. However, we believe that the prevailing discourses that emerged from the focus group interviews allow us to make general comparisons. After a close reading of the interview texts, a coding framework was developed on the basis of empirical evidence and theoretical concepts (explained below). The 10 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. recurring topics that emerged after the initial close examination of the transcripts were later explored further and interpreted with the help of analytical tools of discourse and narrative analysis. The categories of analysis used in this essay are: personal standpoints regarding the Russia–Ukraine conflict; self-positioning regarding ‘competing truths’, that is, the conflicting conceptions of the crisis as mediated via different news sources; understanding of the nature of media texts as reflections of reality or constructed artefacts; plurality of news media repertoire; self-positioning as ‘expert’ media users or as confused ‘layman’ users; and self-reported levels of uncertainty, weariness and escapism in regard to the media coverage of the political crisis in Ukraine. The standpoints regarding the Russia–Ukraine conflict were divided into pro-Kremlin and anti-Kremlin/pro-Ukrainian positions as two opposing poles and more uncertain inbetween positions. These positions are closely connected with self-positioning regarding the conflicting conceptions of the crisis as mediated via different news sources and selfreported levels of uncertainty, weariness and escapism. The news media repertoire was coded as either heterogeneous or homogeneous, with the former being defined as a media diet consisting of news sources of different geopolitical leanings that most often included news media of different geopolitical origins (and in different languages). Accordingly, the homogeneous media repertoire was defined as a non-plural media diet containing sources of news of uniform geopolitical orientation. The understandings of the nature of media texts, trust-building strategies and selfpositioning as media users were interconnected. In creating the category of how the news media was understood, we drew on the basic categories used in reception analysis studies that are incorporated into conceptual mapping by Michelle (2007). Firstly, there are strategies built on the conviction that media texts mirror reality (the belief that more authentic information is more reliable). Secondly, there are strategies that are built on the conviction that media texts/images are social constructions produced by journalists and other content creators (the belief that there is no objective reality). Self-positioning regarding the conflicting conceptions of the crisis as mediated through different news sources was analysed via convictions regarding the ‘truth’, where the conviction that ‘there is no truth at all’ is at one end of the continuum and the conviction of the existence of a firm ‘truth’ is at the other end. By ‘trust-building strategies’ we mean the rationalisation of trust in information presented in the media (‘why I trust … ’), in other words, the decisions about objectivity, authenticity and political motivation behind information production. Uncertainty depended to a great extent on the convictions regarding the ‘truth’ in media texts. In analysing moments of identity construction as media users, we were influenced by positioning theory (Harre & Van Langenhove 1999). During the analysis, we developed two empirical positions: the expert position, demonstrated via the skills and will to determine truth and avoid media indoctrination; and the layman position, demonstrated via a lack of expertise and will to ‘sort out’ contradictory representations of reality in the media. It is best to think of these trust-building and self-positioning strategies as situated along a continuum instead of being dichotomous. In the following analysis, we first explain the categories and then present a typology based on the interrelations of these categories. IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 11 Results Respondents admitted that the political crisis in Ukraine, characterised by an overload of conflicting news messages, made them more active news media users. Consequently, they followed news more frequently and expanded their news media repertoires. Ukraine-related news from different sources was compared. In addition to Russian and national Russian-language (and in some cases also titular-language) news sources, respondents mentioned the use of Western, Ukrainian and Belarusian media outlets and word-of-mouth information obtained via online and offline social networks. Russianspeaking audiences’ activation of transnational communication and information-seeking during the Ukraine crisis was similar to ‘expanded transnationalism’, defined by Guarnizo and Smith (1998) as temporarily increased and widened following of the media of the historical homeland among diasporic audiences during political crises or natural disasters. This extensive exposure to conflicting information had varying durations. Some respondents reported weariness and confusion, which they resolved by no longer following political news, a fact that was emphasised in their self-positioning during group discussions. Other respondents actively engaged with political news, following discussions about news topics or political debates on television and in other media. Strategies of (dis)trust Strategies of trust regarding everyday decisions about objectivity, authenticity and political motivation behind the news were closely linked with general understandings of the nature of media texts. Respondents’ understandings of the nature of media texts, in the context of an ideological conflict, were divided broadly into three subgroups: those who made a distinction between constructions and reflections; those who made a distinction between more and less truthful constructions; and those who saw all media texts as equally untruthful constructions. Audience members in the first group believed ‘depicted persons and events … to be transparent reflections of an external “real” world’ (Michelle 2007, p. 196) if this information came from ideologically trusted media channels. Unmediated real-life encounters, be they personal experience or eyewitness accounts via interpersonal communication, were considered significant sources of authenticity, or ‘sources of referential information’ (Michelle 2007, p. 200). Even if, in some cases, the limited capacity of ‘witnesses’ was recognised, their physical proximity to the events provided them with credible ‘authenticity’ (for example, relatives living close to the battlefield). News coming from ideologically mistrusted media channels was considered to be constructed by journalists, lacking authenticity and untrustworthy. The members of the second subgroup did not draw clear distinctions between media reflections and media constructions. Their trust strategies were based on the belief that some media constructions were more truthful (closer to reflections of reality) than others. Accordingly, alongside convincing visual evidence, it was a mixture of expertise (being well-informed, proximity), performance and charisma that made news messages on Russian television more trustworthy than on the national channels. The use not of neutral mediators but of journalistic opinion-leaders mixing the roles of expert and 12 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. performer also attracted audiences to a confrontation of different worldviews on Russian television. Audience members belonging to the third subgroup saw all media texts as equal constructions of reality. Instead of relying on first-hand, unmediated experiences of reality, they relied primarily on their own analytical capacities to ‘sort out’ the mediated reality of mass media. In group discussions, these individuals talked about their personal encounters with cynical propaganda in the media, for example, digitally altered images or broadcasts of videos taken from other contexts (such as Chechnya) as evidence of the events in Ukraine. Self-positioning as a media user Two dominant strategies of self-positioning as media users emerged in the context of excessive volumes of diverse and clashing conceptions of the Ukraine crisis as mediated through different information sources: the ‘smart’ media user (‘expert’) and the ‘helpless, confused’ media user (‘layperson’). The smart user/expert positioning involved elements of critical and selective media use: the ability to distinguish between media reflections and media constructions; the capacity to separate more ‘truthful’, realistic media constructions from those less ‘truthful’; and the aptitude to ‘discover the truth’ between various media constructions. This also appeared to be the strategy of neutralising media indoctrination (or at least producing a feeling of being immune to it). In the following example, the respondent talks about her use of multiple news sources and the employment of rigorous information processing procedures in order to negotiate incompatible streams of information. Interestingly, this is presented as a skill inherited from her experience under Soviet rule: I watch both Latvian and Russian channels. To balance … . Just like during Soviet times people listened to BBC radio and Russian [Soviet] media, then put it all together and divided by two, and then they got something … . Today we have the same situation with Latvian and Russian channels. Political motives are present in both cases. That’s for sure. On Russian channels there is pro-Russian news, while Latvian channels provide news from the point of view of Latvia. Hence, you need to listen to both, and then you get something that is in between.5 In the eyes of some respondents, non-mainstream news sources, including social media, are of greater value than established news media. There are also some extreme examples in which individuals replaced the gathering of political information from media organisations with learning via word-of-mouth. Additionally, individuals emphasised their independence from mainstream news sources to differentiate themselves positively from fellow audience members, as ‘experts’ rather than ‘dupes’. Another self-positioning consisted of a self-reported lack of interest and/or lack of expertise in geopolitics and news, confusion and uncertainty, as well as other forms of civic self-disempowerment. For example, 31-year-old Yuliya from Tallinn, in discussing the news about NATO’s increased presence in Estonia, positioned herself as an average, Irina, 56, Rıga. 5 Self-positioning as ‘expert’ media user or as confused ‘layman’ user Self-reported level of uncertainty in regard to media coverage of the political crisis in Ukraine Self-positioning regarding ‘competing truths’ Plurality of news sources Understanding of the nature of media texts: reflections of reality or constructed artefacts Standpoint regarding the Russia–Ukraine conflict Subtype 2 ‘moderate loyalist’ Constructed (though reality constructions of ‘our’ news sources are more truthful than reality constructions of ‘their’ news sources) Smart, expert Moderate ‘Our’ news sources as reflections of reality No or low Smart, expert High Little Strong geopolitical Moderate geopolitical allegiance: proallegiance: proKremlin/antiKremlin/antiWestern Western sentiments or sentiments or vice versa vice versa ‘There is one truth ore truthful than others’ Subtype 1 ‘hardline loyalist’ ‘Loyalist’ Subtype 2 ‘neutral optimistic’ High ‘There is a truth in-between’ High Smart, expert Constructed Helplessconfused, layman ‘There is no truth’ Impartial self-positioning Subtype 1 ‘neutral pessimistic’ ‘Neutral’ TABLE 2 TYPOLOGY OF RUSSIAN-SPEAKING AUDIENCES IN LATVIA AND ESTONIA High Helplessconfused, layman Not discussed ‘Do not (want to) know where the truth is’ Little Apolitical selfpositioning ‘Apolitical’ IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 13 14 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. worried citizen who has little expertise in understanding complicated, contradictory political issues and who, in common with other laypeople, is a passive object in the hands of elites who are motivated by money: Naturally, we are carefully following what is going on in Ukraine, because it really is very disturbing. This is geopolitics, which is difficult to comprehend and evaluate. Anyway we understand now that all this is going on for money, for someone’s ambitions or desires, and the people here are like raw material. Of course, we are in the Alliance area, and we need to understand the risks to our security. But can you ever, following the developments in Ukraine, know what’s really going on? … Russian, American and Ukrainian media each give one type of information, and Estonians give another.6 It was typical of respondents presenting themselves as non-experts to take a distanced, somewhat non-committal position towards complicated, uneasy questions about the Ukraine crisis in the group discussions. Audience typology in the context of political crisis The media trust strategies and self-positioning as media consumers, as described above, interacted in various ways with ideological positions vis-a-vis the Russia–Ukraine conflict and the self-reported levels of uncertainty, weariness and escapism. The typology presented below explains these combinations. These types are not clear-cut and fixed entities; they overlap and a single audience member may opt for different strategies under different circumstances. However, in the context of the political crisis in Ukraine, transnational audiences crystallised into distinct types (see Table 2). The first type represents the consolidated loyalty position, characterised by little plurality in personal news sources, and an understanding of the news media as instruments in the hands of the power establishment. Trust in news sources supporting one’s geopolitical allegiances (either pro-Kremlin/anti-Western sentiments or vice versa) was very strong. For these respondents, ‘if what is on the news corresponds to my worldview, then that for me is the truth’.7 In the context of an ideological conflict, facts and opinions that were provided by the news sources of supported parties were assumed to be ‘transparent reflections of an external “real” world’ (Michelle 2007, p. 196), while the opponents’ information was seen as constructed. These respondents positioned themselves as smart media users able to distinguish between the two. Many such users held strong pro-Kremlin views and were highly loyal followers of Russian state television. In this respect, we can observe some link with the identity pattern we earlier labelled ‘diaspora identity’ in combination with elements of the ethnocultural (minority) identity pattern. The Estonian survey data reported above indirectly support this assumption, showing a recent increase in self-categorisation as ‘Russian’ (without any specification of country of habitation), while the self-identification with ‘Estonian Russians’ remained stable. Other survey data show that Latvia’s Russianspeakers were more ready to accept official Russian news discourse when it came to the Ukraine crisis, but were more resistant when it dealt with Latvian national issues 6 Yuliya, 31, Tallinn. Alla, 51, Rıga. 7 IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 15 (Berziņa 2016a, 2016b). Consequently, while a number of focus group respondents in the eastern region of Latgale, bordering Russia, expressed strong pro-Kremlin attitudes, they opposed any potential separatist sentiments in their region. Nevertheless, holding a consistent pro- or anti-Kremlin position was not necessarily connected with homogeneous news media repertoires. Another subtype of audience members holding certain ideological sentiments can be labelled moderate, characterised by the use of plural news sources because of an interest in diverse viewpoints, including oppositional ones. Members of this group acknowledged that at the global level there were plenty of different media institutions offering information and viewpoints framed in various and conflicting ways for consumers to choose in order to ‘form your own opinion’.8 These globally focused, consumerist sentiments resemble some elements of the identity pattern we earlier categorised as ‘emancipatory identity’. However, rather than articulating pro-Western sentiments, audience members with multiple media repertoires and emancipatory orientations were also the most critical of media institutions, and the most likely group to express disappointment about what was published in the media (Leppik & Vihalemm 2017). Negotiated and conditional trust-building strategies were often paired with a general understanding of news media operations as politically or economically motivated. In these cases, the audience members’ own selective assessment of media content was often presented as a source of autonomy (agency), allowing the media user to be (or at least to feel) immune and resistant to media propaganda or ‘mass indoctrination’.9 Various trust-building strategies were thus employed, such as attempts to assess visual evidence or preferring information providers who were physically close to the events, and the watching of court-like confrontational, infotainment-style political debate shows; this all produced feelings of authenticity that, in turn, allowed consumers to ‘pick sides’. For example, for 57-year-old Dimitrii from Tallinn: I like ‘Echo of Moscow’, a radio station; I recommend it! There is an opportunity to express opposing opinions, even extremely contradictory opinions, and you have a right to choose. The opportunity to analyse, to think, to choose, to understand the situation.10 The literature notes that emotional engagement (signified by referential reading) in conjunction with intellectual analysis (signified by critical reading) can support learning, that is, the acquisition of new knowledge (Parsemain 2016). In such cases, individuals are able to shift between referential (media as mirror of real life) and critical, constructivist approaches. It is the shifting modalities of reception that characterise the moderate audience subtype, facilitating civic engagement and curiosity. Here the belief that all news media institutions are politically orchestrated (often derived from the Soviet experience) combines with a feeling of being part of an imagined transnational audience with free choices regarding information sources and meaning-making. It is likely that, despite moments of uncertainty and fatigue, people enjoy this: this audience subtype is characterised by interplays and juxtapositions between enthusiasm and fatigue Nikolai, 37, Rıga. Vladimir, 47, Rıga. 10 Dimitrii, 57, Tallinn. 8 9 16 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. regarding news flows. This can be seen in the following example, where trust in Russian state media is mixed with confusion and escapist sentiments: Don’t know whom to believe, to be honest. [I believe] Russian channels more. But I still don’t know whom to believe. Sometimes I switch off the television when I think ‘I’m sick and tired of the news and will stop watching it’. In the evening I manage to do without the news but then the next morning [I watch it again] … . It’s an addiction.11 This may be another side of the identity pattern combining the enjoyment and compulsion arising from the exercise of institutionally non-prescribed individual freedom as media consumers. This also has some connection with the emancipatory identity pattern. There are also two subtypes of ‘neutral’ audience. These groups are characterised by scepticism towards media channels and reticence in taking sides regarding the conflict between Ukraine and Russia. In these cases, the ideal of a liberal media system with neutral journalistic practices for the sake of the public interest is hardly compatible with the realities of a political crisis and mediated ideological opposition. This creates a sense of pessimism, uncertainty and general distrust. At the same time, the hope of discovering ‘some grain of rationality’12 or ‘a piece of truth’13 adds a temporary optimism. Such ‘neutral’ audience members fluctuated between the more pessimistic and more optimistic subtypes. The use of diverse news sources is not a source of enjoyment, as it is for the previous ‘moderate loyalist’ subtype; the crisis situation is accompanied by a high level of uncertainty and, in the case of the ‘pessimistic’ state, a sense of helplessness. As media users, they are aware of the constructed nature of media content and the limits of audience members in deconstructing these messages and assessing their authenticity. For audiences of the pessimistic subtype, the only possible response to contradictory interpretations of reality is scepticism and suspicion regarding media institutions and their messages: Are there any Russian troops (in Ukraine)? … it is not clear where the truth is. There is not much to talk about; the topic is too controversial. … everyone will defend his point of view, and we ordinary readers, who are not present in the Donbas, cannot check if the Russian troops are there. This is probably the main disadvantage of modern [mass media].14 Similar to the loyalist type of audiences, everyday experience is highly valued in the pessimistic subtype of neutral audiences. This is seen in the conviction that there are no reliable representations of the conflict as mediated via media organisations, and that you can only rely on personal experience: the belief that one has to go to Ukraine and see with one’s own eyes. The optimistic subtype group employ similar understandings and ideals about the media system and the constructed nature of media texts. However, they also exercise a smart consumer self-positioning by hoping, via encounters with a miscellaneous 11 Igor, 41, Liepaja. Boris, 65, Rıga. 13 Anastasiya, 30, Rıga. 14 Alexei, 25, Tallinn. 12 IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 17 collection of news sources, to extract ‘the truth’ in between: an ‘average/middle’ viewpoint, or a grey zone, where black-and-white extremes can be negotiated and reconciled instead of having to choose between opposing viewpoints. In so doing, these audience members also employ elements of the ‘emancipatory identity’ pattern; they tend to avoid essentialising identities and, instead, prefer hybrid identities which provide a space in between different national allegiances: ‘I intentionally read both the Latvian [-language] and Russian [-language] [local internet news site] Delfi. … When there are highly different opinions, none of the sides are right’.15 In contrast to loyalist audience members who rely heavily on word-of-mouth as a source of news, along with established institutional news sources, ‘neutral optimistic’ audiences rely primarily on their own analytical capacities on the basis of mediated contents. Finally, there is a group of audience members who position themselves as being neither loyalist nor neutral but ‘apolitical’ in their geopolitical attitudes. These people report little interest in, and also little understanding of, the conflict, as well as its representations in the media. Here little variety in news sources correlates with a high degree of confusion and escapist sentiments. This shows that individuals who do not even engage in the practice of following various sources of news can suffer from significant confusion. This conclusion is supported by the findings of survey research done in Estonia examining the connections between the use of multiple news sources and opinion formation about the news on the shooting down of the Malaysian passenger aeroplane MH17 in Ukraine in the summer of 2014 (Vihalemm & Leppik 2018). Here the state of confusion might be as much a cause as an effect of the absence of a multiplicity of news sources. While Guarnizo and Smith (1998) note that ‘extended transnationalism’ emerges in times of crises, it is important to understand that, in the case of the Ukrainian conflict, the crisis has lasted for a long time; people admit that they are getting tired and confused and report avoiding news about Ukraine. Some of the respondents who fell into the apolitical subtype claimed their avoidance to be a temporary condition: from time to time, they opted in and out of following the news about the events in Ukraine. This seemed to also be the experience of 55-year-old Nadezhda from Daugavpils. For her, (temporary) escapist sentiments seemed to be the result of the conflicting bilingual, Latvian-language and Russian-language news flows her family was exposed to in their day-to-day news media practices: I prefer watching Discovery. You watch one channel—they say this, then you watch another channel—they say something different. Why should I watch it? … It’s better to watch something about nature and enjoy it … . Sometimes, of course, you want to know what will happen there [in Ukraine] next.16 For others, opting out of news and politics was something that coincided with their general media practices during ‘peaceful’ (non-crisis) times. Here, the political crisis in Ukraine had simply amplified their pre-existing apolitical sentiments. However, as the case of 30-year-old Nikita from Rıga suggests, because of the omnipresence of political Lana, 60, Rıga. Nadezhda, 55, Daugavpils. 15 16 18 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. information during the time of crisis, some individuals may have experienced a shortlived wave of politicisation: I do not follow politics much, only recently … . It is senseless [to follow politics] as you cannot influence it much. I was initially interested in the situation in Ukraine. I followed it for some time but then realised that there was no sense in it … . I understood the essence of the conflict, the positions of all sides … . And I stopped watching [the news about the events in Ukraine]; the story is not interesting to me anymore.17 This kind of escapist strategy, compensating for unpleasant media content by replacing it with less painful content, may also be a way to maintain hybrid, in-between identities and avoid the consolidation and essentialisation of one’s identity which implicitly appears in media discourses. As observed in previous research, both in Estonia and Latvia consumerist mental patterns are used to maintain positive self-esteem (Kalmus & Vihalemm 2008). This approach may therefore also help to deal with complicated issues of geopolitics. Conclusions The depiction of the Russian-speaking population as a pro-Russia loyalist audience, which dominates Estonian and Latvian public discourse, is only partly justified. This analysis, instead, reveals five subtypes of audiences and shows different ways the audience members strove towards autonomy as media users. Audience members holding consolidated ideological loyalties can be divided into two subtypes. The first subtype is characterised by a narrow media repertoire and a strong belief that media texts of ‘our’ side are mirrors of life, but are artificial constructs when they carry oppositional ideology. These media-related strategies support the consolidation of ethno-diasporic identity. This type generally corresponds with the popular view of the ‘Russia-minded’ audience in Estonian and Latvian societies. The members of the second subtype also hold a certain ideological allegiance, but their media-use strategies are characterised by endeavours for a plurality of information sources and opinions, motivated by the wish to draw individual conclusions and locate information that they consider authentic. Thus, some of the loyalist audience are somewhat emancipated. Considering the wide geopolitical circle of information sources (occasionally) consulted, and the fact that following the news is an important citizenship practice, we may call this an exercise in quotidian transnational media citizenship. This kind of media-related practice may combine with more general ethnic and civic identity constructions in various ways: to support emancipatory identity as a reactive anti-national identity or to support consolidation of a certain local identity around the idea of stability and security in the region. The two subtypes of the more neutral ideological position are divided similarly according to their trust strategies and self-identification as media consumers. It is Nikita, 30, Rıga. 17 IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 19 noteworthy that, in the context of the political crisis in Ukraine, the acknowledgement that the media does not properly serve public interests nor convey neutral information makes individuals feel that their ability as media users to decode biased media production is in fact limited. Therefore, the civic engagement of the members of neutral audiences is deliberate but emotionally distant (not taking sides), although they actively follow the news. The more pessimistic subtype, who are closer to civic cynicism, and the more optimistic subtype, who feel occasional fatigue, can be differentiated as ideal types. It is likely that these positions are not static and vary from situation to situation. Both aforementioned types can be, at certain times, motivated to escape from disturbing news streams and seek out substitute media products—such as the Discovery channel—thus avoiding essentialising media discourses. Therefore, the fifth type, ‘apolitical’ audience members who distance themselves from the following of political news, at least about the Ukraine crisis, may include people who otherwise may not belong to this group. In general, it seems unlikely that the political conflict between Russia and Ukraine and Russia and Western countries and the media coverage of the relevant issues will have a longer-term homogenising social impact on the transnational population. Rather, it will maintain its previous, multi-directional identity development patterns. In parallel with the consolidation of ethno-diasporic identities, media-related strategies aimed at maintaining local civic or emancipatory identities are utilised. The geopolitically plural media menus provide an opportunity for one segment of the Russian-speaking audience to maintain civic dignity as audience members and to reconstruct quotidian in-between-ness, as well as to negotiate hybrid identification in the context of essentialising media discourses. We agree with other authors (Panagakos & Horst 2006; Vathi 2013) that hybridity and reflexivity may become tiring; in our study, we found two modes of management during the political crisis in Ukraine that we call emancipatory and escapist strategies. In the case of the emancipatory strategy, heterogeneity has become a self-sustained aim, sometimes approaching an obsession. These audience members may look critically both at attempts by the local PSB media to ‘domesticate’ Russian-speaking audiences and at pro-Russia reporting by Russian media, but at the same time follow their journalistic production enthusiastically since such media practices help these audiences reproduce their identity. The other strategy to avoid taking sides is escapism. This can be exercised in either hedonist/consumerist or depressive modes. Both the hedonistic and cynical subtypes of audiences avoid taking sides but this may lead to uncertainty and selfdistancing from public issues and thus to the erosion of civic identity. Paradoxically, holding to the normative ideal of liberal media seems to lead to escapist strategies and to discourage emancipatory strategies. Thus, during the conflict between Russia and Ukraine and the media war that has accompanied it, part of the Russian-speaking population has demonstrated an ability to maintain transnational ‘in-between-ness’, exercise quotidian acts of citizenship as audience members and emancipatory identity construction strategies. The nature of the qualitative evidence does not allow us to speak authoritatively about the proportions of 20 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. different identity strategies. However, the rich data present a general picture that is far from black and white. The evidence suggests that Russian-speakers engage with media in a variety of ways, reflecting their multidimensional and complex identities. TRIIN VIHALEMM, Institute of Social Studies, University of Tartu, Lossi 36, Tartu 51003, Estonia. Email: triin.vihalemm@ut.ee , Institute of Social Studies, University of Tartu, Lossi 36, Tartu JaNIS JUZEFOVICS 51003, Estonia. Email: janis.juzefovics@ut.ee MARIANNE LEPPIK, Institute of Social Studies, University of Tartu, Lossi 36, Tartu 51003, Estonia. Email: mari19@ut.ee References Adams, C. P. & Ghose, R. (2003) ‘India.com: The Construction of a Space Between’, Progress in Human Geography, 27, 4. Bela, B. (2014) ‘Starptautiska migracija un nacionala identitate: transnacionalas piederıbas veidosanas’, in Rozenvalds, J. & Zobena, A. (eds) Daudzveidig as un mainig as Latvijas identit ates (Rıga, University of Latvia). Berziņa, I. (ed.) (2016a) The Possibility of Societal Destabilization in Latvia: Potential National Security Threats (Rıga, Centre for Security and Strategic Research, National Defence Academy of Latvia). Berziņa, I. (2016b) ‘Perception of the Ukrainian Crisis within Latvian Society’, Estonian Journal of Military Studies, 6, 2. Bhabha, H. (1990) ‘DissemiNation: Time, Narrative, and the Margins of the Modern Nation’, in Bhabha, H. (ed.) Nation and Narration (London & New York, NY, Routledge). Birka, I. (2013) Integration and Sense of Belonging—Case Study Latvia, PhD thesis manuscript (Rıga, University of Latvia), available at: www.szf.lu.lv/fileadmin/user_upload/szf_faili/Petnieciba/Birka_ Ieva_2014.pdf, accessed 3 September 2018. Castells, M. (1997) The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. The Power of Identity (Oxford, Blackwell). Cheskin, A. (2012) ‘Synthesis and Conflict: Russian-speakers’ Discursive Response to Latvia’s Nationalising State’, Europe-Asia Studies, 64, 2. Cheskin, A. (2016) Russian Speakers in Post-Soviet Latvia: Discursive Identity Strategies (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press). Commercio, M. (2008) ‘Systems of Partial Control: Ethnic Dynamics in Post-Soviet Estonia and Latvia’, Studies in Comparative International Development, 43. Dougherty, J. & Kaljurand, R. (2015) Estonia’s ‘Virtual Russian World’: The Influence of Russian Media on Estonia’s Russian Speakers (Tallinn, International Centre for Defence and Security). EHDR (2017) Estonian Human Development Report 2016/2017. Estonia at the Age of Migration (Tallinn, Cooperation Assembly Foundation). Elias, N. & Zeltser-Shorer, M. (2006) ‘Immigrants of the World Unite? A Virtual Community of Russian-speaking Immigrants on the Web’, Journal of International Communication, 12, 2. Glick Schiller, N. (1992) ‘Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 645. Glick Schiller, N. & Salazar, N. B. (2013) ‘Regimes of Mobility Across the Globe’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39, 2. Golbert, R. (2001) ‘Transnational Orientations from Home: Constructions of Israel and Transnational Space among Ukrainian Jewish Youth’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27, 4. Guarnizo, L. & Smith, M. (eds) (1998) Transnationalism from Below, Comparative Urban and Community Research V6 (New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers). Harre, R. & Van Langenhove, L. (1999) Positioning Theory (Oxford, Blackwell). Hepp, A., Bozdag, C. & Suna, L. (2011) ‘Cultural Identity and Communicative Connectivity in Diasporas: Origin-, Ethno- and World-oriented Migrants’, paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Boston, 25 May. IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 21 Jakobson, V. (2002) ‘Role of the Estonian Russian-language Media in the Integration of the Russianspeaking Minority into Estonian Society’, Acta Universitatis Tamperensis, 858. Juzefovics, J. (2012) Ziņas sabiedriskaj a televızij a: paaudzu un etnisko (lingvistisko) grupu ziņu mediju izveles Latvija (Valmiera, Vidzeme University of Applied Sciences). Juzefovics, J. (2017) Broadcasting and National Imagination in Post-Communist Latvia: Defining the Nation, Defining Public Television (Bristol & Chicago, IL, Intellect). J~oesaar, A. (2015a) ‘One Country, Two Polarised Audiences: Estonia and the Deficiency of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive’, Media and Communication, 3, 4. J~oesaar, A. (2015b) ‘Telekanalite vaadatavus Eestis enne ja p€arast 28. septembrit’, Riigikogu Toimetised, 32. J~ oesaar, A., Jufereva, M. & Rannu, S. (2014) ‘Media for Russian Language Minorities: The Role of Estonian Public Broadcasting (ERR) 1990–2013’, Central European Journal of Communication, 7, 2. J~oesaar, A. & Rannu, S. (2014) ‘Estonian Broadcasting and the Russian Language: Trends and Media Policy’, in Horsti, K., Hulten, G. & Titley, G. (ed.) National Conversations. Public Service Media and Cultural Diversity in Europe (Bristol & Chicago, IL, Intellect). Kalmus, V. & Vihalemm, T. (2008) ‘Patterns of Continuity and Disruption: The Specificity of Young People’s Mental Structures in Three Transitional Societies’, Young, 16, 3. Kiisel, M. & Vihalemm, T. (2014) ‘Why the Transformation of the Risk Message is a Healthy Sign: A Model of the Reception of Warning Messages’, Health, Risk and Society, 16, 3. Kolstø, P. (2000) Political Construction Sites: Nation Building in Russia and the Post-Soviet States (Boulder, CO, & Oxford, Westview). Kosmarskaya, N. (2002) ‘Russkie Diaspory: politicheskie mifologii i realii massovogo soznaniya’, Diasporas—Diaspori, 4, 2. Kosmarskaya, N. (2011) ‘Russia and Post-Soviet “Russian Diaspora”: Contrasting Visions, Conflicting Projects’, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 17, 1. Laitin, D. (1998) Identity in Formation: The Russian-Speaking Populations in the Near Abroad (Ithaca, NY, & London, Cornell University Press). Lazda, M. (2009) ‘Reconsidering Nationalism: The Baltic Case of Latvia in 1989’, International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 22, 4. Lebedeva, N. (1998) ‘Russkie v stranakh blizhnego zarubezhya’, Vestnik RAN, 4. Leppik, M. & Vihalemm, T. (2017) ‘Venekeelse elanikkonna hargmaine meediakasutus’, in Vihalemm, P., Lauristin, M., Vihalemm, T. & Kalmus, V. (eds) Eesti € uhiskond kiirenevas ajas: Eesti elaviku muutumine 2002–2014 uuringu Mina. Maailm. Meedia tulemuste p~ ohjal (Tartu, Tartu University Press). Levitt, P. (2011) ‘A Transnational Gaze’, Migraciones Internacionales, 6, 1. L€ofgren. O. (2001) ‘The Nation as Home or Motel? Metaphors of Media and Belonging’, Sosiologisk Årbok, 1. Madianou, M. (2006) ‘Contested Communicative Spaces: Rethinking Identities, Boundaries and the Role of the Media among Turkish Speakers in Greece’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31, 3. Melvin, N. (1995) Russians Beyond Russia: The Politics of National Identity (London, The Royal Institute of International Affairs). Michelle, C. (2007) ‘Modes of Reception: A Consolidated Analytical Framework’, The Communication Review, 10. Moring, T. & Godenhjelm, S. (2011) ‘Broadcasting for Minorities in Big and Small Countries’, in Lowe, G. F. & Nissen, C. S. (eds) Small Among Giants: Television Broadcasting in Smaller Countries (Gothenburg, Nordicom). Muiznieks, N., Rozenvalds, J. & Birka, I. (2013) ‘Ethnicity and Social Cohesion in the Post-Soviet Baltic States’, Patterns of Prejudice, 47, 3. Muiznieks, N. (ed.) (2010) How Integrated is Latvian Society? An Audit of Achievements, Failures and Challenges (Rıga, University of Latvia). Mythen, G. (2012) ‘Identities in the Third Space? Solidity, Elasticity and Resilience amongst Young British Pakistani Muslims’, The British Journal of Sociology, 63, 3. Nederveen Pieterse, J. (2003) Globalization and Culture: Global Melange (Lanham, MD, Rowman & Littlefield). Panagakos, A. N. & Horst, H. (2006) ‘Return to Cyberia: Technology and the Social Worlds of Transnational Technology and the Social World’, Global Networks, 6, 2. Parsemain, A. L. (2016) ‘Do Critical Viewers Learn from Television?’, Participations, 13, 1. Pilkington, H. (1998) Migration, Displacement and Identity in Post-Soviet Russia (London & New York, NY, Routledge). 22 TRIIN VIHALEMM ET AL. Poppe, E. & Hagendoorn, L. (2001) ‘Types of Identification Among Russians in the “Near Abroad”’, Europe-Asia Studies, 53, 1. Portes, A. & Rumbaut, R. (2001) Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation (Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA, & New York, NY, University of California Press and Russell Sage Foundation). Robins, K. & Aksoy, A. (2003) ‘Banal Transnationalism: The Difference that Television Makes’, in Karim, K. (ed.) The Media of Diaspora (London, Routledge). Romanov, A. (2000) ‘The Russian Diaspora in Latvia and Estonia: Predicting Language Outcomes’, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 21, 1. Rose, R. & Maley, W. (1994) Nationalities in the Baltic States: A Survey Study (Glasgow, Centre for the Study of Public Policy). Rozukalne, A. (2014) ‘Krievijas mediji Latvijā : ıpasnieki, regulā cija, ietekme’, in Kudors, A. (ed.) Krievijas publiskā diplomā tija Latvijā : mediji un nevalstiskais sektors (Rıga, The Centre for East European Policy Studies, University of Latvia Press). Subbotina, I. (1997) ‘Russkiye v Estonii: alternativy I perspektivy’, in Tishkov, N. (ed.) Vynuzdennye migranty: integratsiya I vozvrasheniye (Moscow, Institute of Ethnography, Russian Academy of Sciences). Sulmane, I. (2006) ‘The Russian Language Media in Latvia’, in Muiznieks, N. (ed.) Latvian–Russian Relations: Domestic and International Dimensions (Rıga, University of Latvia Press). Sulmane, I. (2010) ‘The Media and Integration’, in Muiznieks, N. (ed.) How Integrated is Latvian Society? An Audit of Achievements, Failures and Challenges (Rıga, University of Latvia Press). Tabuns, A. (2010) ‘Identity, Ethnic Relations, Language and Culture’, in Muiznieks, N. (ed.) How Integrated is Latvian Society? An Audit of Achievements, Failures and Challenges (Rıga, University of Latvia Press). University of Latvia (2010) Survey for the Human Development Report (Rıga, University of Latvia/ SKDS) University of Tartu (2014) Survey for the ‘Me. The World. Media’ Research Project (Tartu, University of Tartu, Saar Poll Ltd). Vathi, Z. (2013) ‘Transnational Orientation, Cosmopolitanism and Integration among Albanian-Origin Teenagers in Tuscany’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39, 6. Vertovec, S. (2001) ‘Transnationalism and Identity’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27, 4. Vertovec, S. (2004) ‘Migrant Transnationalism and Modes of Transformation’, International Migration Review, 38, 3. € Vihalemm, P. (2012) ‘Meedia ja infov€ali’, in Integratsiooni Monitooring 2011 (Tallinn, Tartu Ulikool, Praxis, Emor). Vihalemm, T. (2008) ‘Crystallizing and Emancipating Identities in Post-Communist Estonia’, Nationalities Papers, 35, 3. Vihalemm, T. & Hogan-Brun, G. (2013a) ‘Dilemmas of Estonian Nation Building in the Open Media Market’, Sociolinguistica. Internationales Jahrbuch f€ ur Europ€ aische Soziolinguistik, 27, 1. Vihalemm, T. & Hogan-Brun, G. (2013b) ‘Language Policies and Practices Across the Baltic: Processes, Challenges and Prospects’, European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1, 1. Vihalemm, T. & Kalmus, V. (2010) ‘Cultural Differentiation of the Russian Minority’, in Vihalemm, P. & Lauristin, M. (eds) Estonia's Transition to the EU: Twenty Years On (London & New York, NY, Routledge). Vihalemm, T. & Kaplan, C. (2017) ‘Russian Ethnic Identity: Subjective Meanings from Estonia, Russia and Kazakhstan’, in Kannike, A. & V€astrik, E.-H. (eds) Body, Personhood and Privacy: Perspectives on Cultural Other and Human Experience. Approaches to Culture Theory 7 (Tartu, Tartu University Press). Vihalemm, T. & Leppik, M. (2018) ‘Multilingualism and Media-Related Practices of the Estonian Russian-Speaking Population’, in Marten, H. F. & Lazdina, S. (eds) Multilingualism in the Baltic States: Societal Discourses, Language Policies and Contact Phenomena (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan). Vihalemm, T. & Masso, A. (2007) ‘(Re)Construction of Collective Identities after the Dissolution of the Soviet Union: The Case of Estonia’, Nationalities Papers, 35, 1. IDENTITY AND MEDIA USE 23 Appendix TABLE A1 THE SAMPLE OF THE FOCUS GROUPS Total number of people who participated in focus groups Time period of focus groups Locations of focus groups Estonia Latvia 33 80 6 January–11 March 2015 3–27 November 2014 Tallinn (four groups); Kohtla-J€arve Riga (five groups); Daugavpils (one group) (two groups); Liepaja (one group); Rezekne (one group) Gender Male Female 15 18 37 43 Age Up to 35 36–55 years 56þ years 17 11 5 25 35 20 Education Basic Secondary Higher 1 18 14 2 41 37