Sabbioneta & Palmanova: Classical Influence on Renaissance Urban Design

advertisement

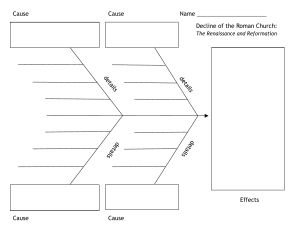

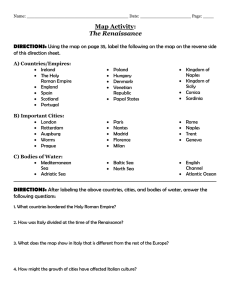

University of Bath, BSc (hons) Architecture AR20364: Architectural History & Theory 2 How do the urban designs of Sabbioneta and Palmanova demonstrate continuity with Classical example and theory? Question 1: How did ancient Roman architecture lend itself to the architectural design of cities and large urban buildings from the Renaissance onwards? Word Count: 1650 (inc. text in footnotes) Candidate Number: 10719 The model cities of Palmanova and Sabbioneta present two differing Renaissance ideals of urban design, contrasting dramatically in form, using a radial-concentric and a grid plan respectively. This essay examines the degree of influence that the work of Vitruvius, among other Classical theorists, had on these ideal cities and how this displays continuity with Classical urbanism. Palmanova and Sabbioneta, both designed in the second half of the cinquecento and both newly established cities, provide complete examples of Renaissance urban theory, and are crucial in examining differing schools of thought existing in urbanism during the period. The most significant treatise on Roman architecture and urban planning, Vitruvius's De architectura, was recovered from a monastery in St Gallen, Switzerland in 1416 1 and subsequently had a dramatic impact on Renaissance urban planning. The 'extremely laconic' 2 description provided by Vitruvius within chapters IV-VII of book I 3 allows differing models to be constructed from the text, and established two interpretations: the city as radial-concentric and the city arranged using a grid plan. Palmanova (fig.1) , constructed between 1593-1613, perfectly represents one of these schools of thought in interpreting Vitruvius' description of the ideal city. This line of thought can be traced back to De re aedificatoria, where 'Alberti’s interpretation of the Vitruvian city [...] integrates the Roman tradition of the cross-shaped cosmic complex of the cardo and decumanus' 4 and is radial-concentric, 'inspired by Plato’s cosmic ideal city-state in the Laws' 5 and description of Atlantis 6 (fig. 2). Alberti's proposals were fundamental for the establishment of the Renaissance model city, and through the work of other architects of the quattrocento, such as Filarete, the radial plan was confirmed as a dominant model of Renaissance urban thought. The radial city proposed by Filarete, "Sforzinda" (fig. 3), was further revised by Francesco di Giorgio 7 and 'Palmanova was little more than a variation on one of Francesco's themes' 8. In Alberti and Filarete's emphasis on applying 'Vitruvian principles to contemporary requirements' 9, Vitruvius' influence on the design of Palmanova is explicit. Sabbioneta (fig. 4), built between 1556 and 1591, symbolises an alternate interpretation to Vitruvius' discussion of urban planning, and embraces the grid plan for urban organisation. 'Vespasiano’s design for Sabbioneta was heavily influenced by Roman city planning', and this 1 Balchin, P.N., 2008. Urban Development in Renaissance Italy. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons. p. 157 Lagopoulos, A., 2009. The semiotics of the Vitruvian city. Semiotica, 175(1), pp.193-251. p.193 3 Ibid. p. 195 4 Ibid. p. 208 5 Ibid. p. 208 6 Lehmann-Hartleben, K., 1943. The Impact of Ancient City Planning on European Architecture. Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians, 3(1), pp. 22-29. p. 28 7 De La Croix, H., 1960. Military Architecture and the Radial City Plan in Sixteenth Century Italy. The Art Bulletin, 42(4), pp. 263-290. p. 270 8 Ibid. p. 271 9 Balchin, P.N., 2008. Urban Development in Renaissance Italy. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons. p. 158 2 inspiration is most clear in the Via Giulia, a straight road that crosses the city from east to west, can be read as a direct correspondence to the Decumanus Maximus, a fundamental characteristic of Roman urban planning 10. During the cinquecento 'the orthogonal network plan was privileged', as it aligned with most interpretations of the ancient city, 'according to Vitruvius' 11 . Whilst 'the pressure of the text pushes us towards the radial plan' 12, several theorists of the cinquecento 'interpreted the Vitruvian text in the traditional gridiron manner' 13, and this corroborates with modern scholarly thought 14. Therefore Sabbioneta can be recognised as a consequence of this line of reasoning, and more closely reflects Roman urban practices, visible in knowledge gained from the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii 15. However, the fact that Sabbioneta is a more accurate realisation of Roman city planning does not detract from the detail that Palmanova was heavily influenced by Roman theory. The radical contrast between the designs of Palmanova and Sabbioneta can be explained with the differing ancient supplementary inspirations to each model. In Palmanova, Plato's description of Atlantis in Critias and ideal city state in the Laws are both described as radial and fortified, and informed Alberti's ideal city 16,17. However, the Platonic radial-concentric model was purely theoretical, and the actual model realised throughout the Classical world was the Hippodamian grid plan 18,19, and it is in Sabbioneta's design that the influence of Hippodamus of Miletus is exhibited. Hippodamus' native city, laid out by him 20, is referenced several times in De architectura 21. Hippodamus' urban planning is also mentioned in Aristotle's Politics, and given Vespasiano’s 'strong classical education' 22, this would have certainly been a reference of his. Therefore, the urban design of Palmanova can be described as Vitruvian with Platonic characteristics, and Sabbioneta Vitruvian with Hippodamian characteristics. Continuity with Roman city planning can be further elaborated in the spiritual principles reflected in the design of Sabbioneta and Palmanova. Cosmology was a significant influence to ancient urban planning, articulated in book IX of De architectura 23. The Romans inherited much of the 'mythic significance' 24 of the urban plan from Greek theory that 'reflected religious and spiritual 10 Schutten, J., 2021. The Ideas of the Renaissance in Urban Planning: An Analysis of Three Centres of the Renaissance. Thesis (M.Sc.). Delft University of Technology. p. 18 11 UNESCO, 2008. Mantoue et Sabbioneta Proposition d’Inscription à la Liste des Biens Culturels et Naturels du Patrimoine Mondial (Olivia Robertson, Trans.). Paris: UNESCO. p. 718 12 Lagopoulos, A., 2009. The semiotics of the Vitruvian city. Semiotica, 175(1), pp.193-251. p. 213 13 De La Croix, H., 1960. Military Architecture and the Radial City Plan in Sixteenth Century Italy. The Art Bulletin, 42(4), pp. 263-290. p. 263 14 Lagopoulos, A., 2009. The semiotics of the Vitruvian city. Semiotica, 175(1), pp.193-251. p. 215 15 As Herculaneum was discovered in 1709, and Pompeii identified in 1763, the urban plan of Sabbioneta could not have used these cities as precedent. However, with our modern understanding of Roman urban planning informed by these discoveries, and only example of radial-concentric planning in Italy before the Renaissance of the Bronze Age Castellieri culture (Lehmann-Hartleben, K., 1943, p. 28), one can apply modern insight and confirm the grid plan as dominant in Roman urbanism. 16 Lagopoulos, A., 2009. The semiotics of the Vitruvian city. Semiotica, 175(1), pp.193-251. p. 208 17 Lehmann-Hartleben, K., 1943. The Impact of Ancient City Planning on European Architecture. Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians, 3(1), pp. 22-29. p. 28 18 Lagopoulos, A., 2009. The semiotics of the Vitruvian city. Semiotica, 175(1), pp.193-251. p. 213 19 Higgins, H.B., 2009. The Grid Book. Cambridge: The MIT Press. p. 57 20 Ibid. p. 58 21 Vitruvius, 1914. The Ten Books on Architecture (Morgan, M.H., Trans.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 77, 103, 200 22 Cowan, J., 2016. Hamlet’s Ghost Vespasiano Gonzaga and his Ideal City. Thesis (Ph.D.). University of Queensland, Brisbane. p. 162 23 Vitruvius, 1914. The Ten Books on Architecture (Morgan, M.H., Trans.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 251-273 24 Higgins, H.B., 2009. The Grid Book. Cambridge: The MIT Press. p. 57 principles and motivations' 25,26. This influence is visible in Sabbioneta, with the grid axis at a slight inclination orientated in order to correspond with the south azimuth of the sunrise on the 6th of December, with Vespasiano born on this day 'shortly after sunrise'. This practice was common for Roman city founders, 27 and in Vespasiano's egoism and classical education his imposition of 'ancient metaphysical concepts' 28 is a clear influence on the plan of Sabbioneta. Present within the theory guiding the construction of Palmanova is the assertion of 'harmony between the spiritual and material worlds' 29, and this intention is also referred to in De re aedificatoria. In Alberti's interpretation of the Vitruvian city and its greatest manifestation in the urban model of Palmanova, his ambition to discover the 'harmonic order of the universe' 30, certainly does inform the city's urban layout, and is a direct continuation of thought from the Classical period. The radial-concentric model - along with the grid-plan city - is built on foundations of 'symbolic matters and the cosmic code' 31, and these principles are fully embodied within the urban plans of Sabbioneta and Palmanova. The importance of militaristic interests in the development of Roman urban planning is another avenue that exerts influence on the plans of the Renaissance. The strategic motivations present in Roman urbanism is demonstrated by the grid plan dominating Roman military encampments (castra), with many then proceeding to develop into permanent cities 32,33. This model is viewed as being the typical Roman city as it was the basis of 'the majority of the cities established and developed during the Roman period' 34, and so association can be agreed between Roman urban planning and militarism. Using classical urban theory as precedent, both Sabbioneta and Palmanova incorporate military theory into their architecture. Whilst Sabbioneta was 'created with the features of the ideal city', this was subservient to 'concrete and detailed requirements of military defence' 35, and was designed as a capital of a small independent state in a backdrop of 'persistent wars' 36 plaguing the italian peninsula during the first half of the cinquecento. The layout of the city, an 'obvious recovery of the model of the 25 26 Higgins, H.B., 2009. The Grid Book. Cambridge: The MIT Press. p. 57 How this text is presented by Higgins is in the context of Hellenistic urban planning, that she then proceeds to contrast with Roman urban theory, communicated as entirely 'pragmatic' and rational (Higgins, H.B., 2009, p. 60). However, this explanation can be refuted in the work of Lagopoulos (2009, pp.234, 238, 242), Schutten (2021, p.18) and is unjustifiable given the syncretistic nature of De architectura (Visone, M., 2011. p.62), the greatest example of Roman urban planning available to us. In the influence of classical Greek theory and example on the work of Vitruvius (Lagopoulos, A., 2009, pp.194, 246, 247; Vitruvius, 1914, pp. 25-27), there is great level of preservation of Greek ideals present in Roman theory, and is made more evident in De architectura's use of Greek terminology (Lagopoulos, A., 2009, p. 196; Kruft, H.W., 1994, p. 21). As both Vitruvius and ancient Greek urban planners used spirituality to justify organisation of the city (Higgins, H.B., 2009, p.57; Vitruvius, 1914, p. 31), the rationality proposed by Higgins of Roman urban planning in contrast to Greek is erroneous, and Hellenistic principles can be seen as corresponding to Roman motivations. No citations are used by Higgins to support her claim. 27 Schutten, J., 2021. The Ideas of the Renaissance in Urban Planning: An Analysis of Three Centres of the Renaissance. Thesis (M.Sc.). Delft University of Technology. p. 18 28 Cowan, J., 2016. Hamlet’s Ghost Vespasiano Gonzaga and his Ideal City. Thesis (Ph.D.). University of Queensland, Brisbane. p. 58 29 UNESCO, 2017. Venetian Works of Defence between the 16th and 17th Centuries: Stato da Terra – Western Stato da Mar. Paris: UNESCO. p. 253 30 Pearson, C., 2011. Humanism and the Urban World: Leon Battista Alberti and the Renaissance City. State College, Penn State University Press. p. 191 31 Lagopoulos, A., 2009. The semiotics of the Vitruvian city. Semiotica, 175(1), pp.193-251. p. 234 32 Higgins, H.B., 2009. The Grid Book. Cambridge: The MIT Press. p. 60 33 Cavaglieri, G., 1949. Outline for a History of City Planning. From Prehistory to the Fall of the Roman Empire: IV. Etruscan and Roman. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 8(3), pp. 27-42. p. 29 34 Ibid. p.32 35 UNESCO, 2008. Mantoue et Sabbioneta Proposition d’Inscription à la Liste des Biens Culturels et Naturels du Patrimoine Mondial (Olivia Robertson, Trans.). Paris: UNESCO. 36 Balchin, P.N., 2008. Urban Development in Renaissance Italy. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons. p. 237 Roman castrum' 37, reflects this, and demonstrates a consistency of thought relating to the defensive territorial ambitions of the Roman Empire. Established in 1593, with the Ottoman's expansion into Europe at its greatest extent, Palmanova was established at the Venetian Republic's 'eastern frontier against the threat of Turkish aggression' 38, and made it necessary that the city 'was planned first and foremost as a fortress' 39. In the design of Palmanova 'civil and military prerogatives co-existed in perfect harmony' 40, a characteristic shared with the imperialistic settlements of ancient Rome. What is evident in Palmanova and Sabbioneta is not just the desire to encompass an urban context within a fortress but additionally to establish concordance between civilian and military demands, and Classical urban theory forms the foundation of this inquiry. The juxtaposition between the urbanism of Palmanova and Sabbioneta and military architecture of Mediaeval and Early Renaissance Europe proceeding these models demonstrates a unique approach using new sources of information, informed by ancient precedent. However, a distinction to the military architecture of the Renaissance is the utilisation of arrowhead bastions, evidencing reaction to advancements in weaponry alongside the use of Classical precedent. In conclusion, continuity with Classical theory is demonstrated in two model cities of the cinquecento - Palmanova and Sabbioneta. The work of Vitruvius cannot be understated in its influence on the two cities, and when infused with other Classical references generates two opposing models of urbanism. It would be incomplete to present Roman urban planning theory without the Greek urbanism that informed it, and this approach provides explanation to the contrast that exists between Palmanova and Sabbioneta, with the former having Platonic influence and latter Hippodamian, both through the lens of Vitruvius. However, differing conclusions does not discount the fact that both Palmanova and Sabbioneta heavily rely on Classical theory. Uniformity between the urban theories of ancient Greece and Rome and ideas of the Renaissance can be viewed in the cosmic significance ingrained in the designs of Palmanova and Sabbioneta, along with militaristic ambition. The conditions of the Italian peninsula during the cinquecento made defence a necessary consideration in urban planning, and the availability of Classical texts at this time was a great influence to military architecture. 37 UNESCO, 2008. Mantoue et Sabbioneta Proposition d’Inscription à la Liste des Biens Culturels et Naturels du Patrimoine Mondial (Olivia Robertson, Trans.). Paris: UNESCO. p. 129 38 De La Croix, H., 1966. Palmanova: A Study in Sixteenth Century Urbanism. Saggi e Memorie di storia dell'arte, 5(1), pp.24-41. p. 25 39 Ibid. p. 36 40 UNESCO, 2017. Venetian Works of Defence between the 16th and 17th Centuries: Stato da Terra – Western Stato da Mar. Paris: UNESCO. p. 331 Figure 1 V.M. Coronelli, 1708. Palma [Engraving] Historical Museum, Palmanova. Figure 2 Alberti’s ideal city. Lagopoulos, 1993, cited by Lagopoulos, A., 2009. The semiotics of the Vitruvian city. Semiotica, 175(1), pp.193-251. p. 209 Figure 3 Filarete’s Sforzinda. Akkerman, A. and Shao, J., 2021. The Bagua as an Intermediary between Archaic Chinese Geomancy and Early European Urban Planning and Design. Journal of Chinese Architecture and Urbanism, 23(1). p. 12 Figure 4 Aerial view of Sabbioneta. ICOMOS, 2008. Mantua and Sabbioneta (Italy). Paris: UNESCO. Bibliography Balchin, P.N., 2008. Urban Development in Renaissance Italy. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons. Cavaglieri, G., 1949. Outline for a History of City Planning. From Prehistory to the Fall of the Roman Empire: IV. Etruscan and Roman. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 8(3), pp. 27-42. Cowan, J., 2016. Hamlet’s Ghost Vespasiano Gonzaga and his Ideal City. Thesis (Ph.D.). University of Queensland, Brisbane. De La Croix, H., 1960. Military Architecture and the Radial City Plan in Sixteenth Century Italy. The Art Bulletin, 42(4), pp. 263-290. De La Croix, H., 1966. Palmanova: A Study in Sixteenth Century Urbanism. Saggi e Memorie di storia dell'arte, 5(1), pp.24-41. Higgins, H.B., 2009. The Grid Book. Cambridge: The MIT Press. Kruft, H.W., 1994. A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. Lagopoulos, A., 2009. The semiotics of the Vitruvian city. Semiotica, 175(1), pp.193-251. Lehmann-Hartleben, K., 1943. The Impact of Ancient City Planning on European Architecture. Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians, 3(1), pp. 22-29. Pearson, C., 2011. Humanism and the Urban World: Leon Battista Alberti and the Renaissance City. State College, Penn State University Press. Schutten, J., 2021. The Ideas of the Renaissance in Urban Planning: An Analysis of Three Centres of the Renaissance. Thesis (M.Sc.). Delft University of Technology. UNESCO, 2008. Mantoue et Sabbioneta Proposition d’Inscription à la Liste des Biens Culturels et Naturels du Patrimoine Mondial (Olivia Robertson, Trans.). Paris: UNESCO. UNESCO, 2017. Venetian Works of Defence between the 16th and 17th Centuries: Stato da Terra – Western Stato da Mar. Paris: UNESCO. Visone, M., 2011. Vitruvianism: Its Origins and Transformations. EAHN Newsletter, 3(11), pp. 62-65. Vitruvius, 1914. The Ten Books on Architecture (Morgan, M.H., Trans.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.