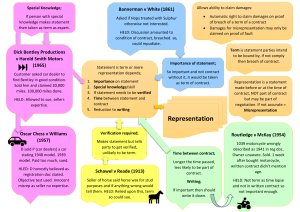

Contract law Roger Halson Catharine MacMillan Richard Stone The 2016 and 2017 revisions to this module guide were prepared for the University of London International Programmes by: uu Roger Halson, Professor of Contract and Commercial Law at the University of Leeds. In the 2004 edition of this guide Catharine MacMillan was primarily responsible for Chapters 1–2, 4–5, 7–8, 10–14 and 16–17. Richard Stone was primarily responsible for Chapters 3, 6, 9 and 15. Catharine MacMillan was responsible for the 2009, 2012, 2013 and 2014 revisions. The 2015 updates to the guide were prepared by Anne Street. This is one of a series of module guides published by the University. We regret that owing to pressure of work the authors are unable to enter into any correspondence relating to, or arising from, the guide. If you have any comments on this module guide, favourable or unfavourable, please use the form at the back of this guide. Acknowledgements Figure 8.1 has been reproduced by kind permission of: uu Jan Daniëls © MarineTraffic.com Figures 16.1, 16.2 and 16.3 have been reproduced by kind permission of: uu Hugh Conway-Jones © www.gloucesterdocks.me.uk University of London International Programmes Publications Office Stewart House 32 Russell Square London WC1B 5DN United Kingdom www.londoninternational.ac.uk Published by: University of London © University of London 2017 The University of London asserts copyright over all material in this module guide except where otherwise indicated. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. We make every effort to respect copyright. If you think we have inadvertently used your copyright material, please let us know. Contract law page i Contents Module descriptor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v 1 Introduction and general principles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 1.1 Studying the law of contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 1.2 Reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 1.3 Method of working . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 1.4 Some issues in the law of contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 1.5 Plan of the module guide . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 1.6 Format of the examination paper . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15 Part I Requirements for the making of a contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20 2.1 The offer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 2.2 Communication of the offer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 2.3 Acceptance of the offer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.4 Communication of the acceptance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 2.5 Exceptions to the need for communication of the acceptance . . . . . . . . 27 2.6 Method of acceptance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30 2.7 The end of an unaccepted offer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 30 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39 3 Consideration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42 3.1 Consideration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43 3.2 Promissory estoppel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56 4 Other formative requirements: intention, certainty and completeness . 57 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58 4.1 The intention to create legal relations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59 4.2 Certainty of terms and vagueness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62 4.3 A complete agreement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .63 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67 Part II Content of a contract and regulation of terms . . . . . . . . . . 69 5 The terms of the contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70 5.1 Is a statement or assurance a term of the contract? . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71 5.2 The use of implied terms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.3 The classification of terms into minor undertakings and major undertakings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78 74 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84 page ii University of London International Programmes 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86 6.1 Indirect common law controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87 6.2 Statutory control . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103 Part III The capacity to contract – minors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105 7 Contracts made by minors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106 7.1 Contracts for necessaries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107 7.2 Beneficial contracts of service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.3 Voidable contracts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108 7.4 Recovery of property . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108 107 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110 Part IV Vitiating elements in the formation of a contract . . . . . . . . . 111 8 Mistake . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112 8.1 Some guidelines on mistake . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113 8.2 Bilateral mistakes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114 8.3 Unilateral mistakes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119 8.4 Mistake in equity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129 9 Misrepresentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132 9.1 Definition of misrepresentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133 9.2 Remedies for misrepresentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138 9.3 Exclusion of liability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147 10 Duress and undue influence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150 10.1 Duress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151 10.2 Undue influence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160 Part v Who can enforce the terms of a contract? . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161 11 Third parties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162 11.1 The doctrine of privity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163 11.2 The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164 11.3 Rights conferred on third parties at common law . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167 11.4 Liability imposed upon third parties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 176 Contract law page iii Part VI Illegality and public policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177 12 Illegality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178 12.1 Statutory illegality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179 12.2 Common law illegality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181 12.3 The effects of illegality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187 13 Restraint of trade . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190 13.1 General principles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191 13.2 Employment contracts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191 13.3 The sale of a business . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 193 13.4 Other agreements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 196 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197 Part VII The discharge of a contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199 14 Performance and breach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200 14.1 The principle of substantial performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201 14.2 When a breach of contract occurs (‘actual breach’) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202 14.3 What occurs upon breach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204 14.4 Anticipatory breach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 205 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 208 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209 15 Frustration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 212 15.1 The basis of the doctrine of frustration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 213 15.2 The nature of a ‘frustrating event’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214 15.3 Limitations on the doctrine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217 15.4 The effect of frustration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 218 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 224 Part VIII Remedies for breach of contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225 16 Damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 226 16.1 The purpose of an award of damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227 16.2 Two measures of damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227 16.3 When is restitution available? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 230 16.4 Non-pecuniary loss . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231 16.5 Remoteness of damage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232 16.6 Mitigation of damage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235 16.7 Liquidated damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 236 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243 page iv University of London International Programmes 17 Equitable remedies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 246 17.1 Specific performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247 17.2 Damages in lieu of specific performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249 17.3 Injunctions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 250 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 252 Feedback to activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253 Chapter 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255 Chapter 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255 Chapter 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 257 Chapter 4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 260 Chapter 5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262 Chapter 6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264 Chapter 7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267 Chapter 8 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267 Chapter 9 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271 Chapter 10 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 273 Chapter 11 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275 Chapter 12 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277 Chapter 13 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 278 Chapter 14 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279 Chapter 15 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280 Chapter 16 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 283 Chapter 17 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285 Contract law Module descriptor Module descriptor GENERAL INFORMATION Module title Contract law Module code LA1040 Module level 4 Contact email The Undergraduate Laws Programme courses are run in collaboration with the University of London International Programmes. Enquiries may be made via the Student Advice Centre at: www.enquiries.londoninternational.ac.uk Credit value 30 Courses on which this module is offered CertHE, LLB, EMFSS Module pre-requisites None Notional study time 300 hours MODULE PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW Contract law is one of the seven foundation modules required for a qualifying law degree in England and Wales and is a core requirement of the University of London LLB and CertHE Common Law courses. This module covers the key underlying principles of English contract law and includes key topics such as formation of contracts, consideration, privity, breach of contract and remedies for breach of contract. MODULE AIM This module introduces students to the principles of contract at common law and in equity and helps them to understand how these principles are applied to agreements. LEARNING OUTCOMES: KNOWLEDGE Students completing this module are expected to have knowledge and understanding of the main doctrines, concepts and principles of contract law. In particular they should be able to: 1. Describe the essential elements of a contract and explain how a contract is formed, modified and terminated; 2. Identify and explain appropriate remedies for breach of contractual obligations; 3. Describe the general (economic, social and political) context in which contract law is applied and the current issues affecting contract law; 4. Demonstrate understanding of the development of contract law and discuss its possible future direction(s). page v page vi University of London International Programmes LEARNING OUTCOMES: SKILLS Students completing this module should be able to demonstrate the ability to: 1. Summarise standard legal materials and arguments; 2. Analyse statutes and cases concerned with contract law; 3. Identify issues raised by legal questions and problems and provide reasoned solutions; 4. Carry out straightforward research tasks, using internet-based resources; 5. Reflect on their own learning, responding appropriately to formative testing and feedback. BENCHMARK FOR LEARNING OUTCOMES Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) benchmark statement for Law (2015). MODULE SYLLABUS a. The formation of contracts. Offer and acceptance. Consideration. Certainty of agreement. Intention to create legal relations. b. The content of the contract. Conditions, warranties and intermediate terms. Exemption clauses. Implied terms at common law. Collateral contracts. Statutory implied terms with regard to the quality of goods sold and goods or services supplied. c. Vitiating factors. Mistake. Misrepresentation. Duress and undue influence. d. Illegality and public policy (excluding gaming and wagering). Contracts illegal at common law. Consequences of illegality. Contracts in restraint of trade. e. Capacity to contract, with particular reference to the capacity of minors. f. Third parties (excluding agency and assignment). g. Performance and breach. Substantial performance. Repudiation and anticipatory breach. Discharge by breach. Discharge under the doctrine of frustration. h. Remedies for breach of contract. General principles governing the assessment of damages. Remoteness of damage. Damages for non-financial loss. Mitigation. Restitutionary remedies. Liquidated damages and penalties. Specific performance. LEARNING AND TEACHING Module guide Module guides are the student’s primary learning resource. The module guide covers the entire syllabus and provides students with the grounding to complete the module successfully. It sets out the learning outcomes that must be achieved as well as providing advice on how to study the module. Each chapter of the guide includes essential and further reading and a series of activities designed to test knowledge and develop relevant skills. Feedback on activities is provided at the end of the guide. In addition, each chapter contains sample examination questions with guidance on how to answer, self-assessment questions to enable students to judge if they are ready to move on, and multiple choice quizzes, with answers provided on the VLE. The module guide is supplemented each year with the pre-exam update, also made available on the VLE. The Laws Virtual Learning Environment The Laws VLE provides one centralised location where the following resources are provided: uu a module page with news and updates, provided by legal academics associated with the Laws Programme; Contract law Module descriptor uu a complete version of the module guides; uu online audio presentations; uu pre-exam updates; uu past examination papers and reports; uu discussion forums where students can debate and interact with other students; uu Computer Marked Assessments – multiple choice questions with feedback are available for some modules allowing students to test their knowledge and understanding of the key topics. The Online Library The Online Library provides access to: uu the professional legal databases LexisLibrary and Westlaw; uu cases and up-to-date statutes; uu key academic law journals; uu law reports; uu links to important websites. Core reading Students should refer to the following core text. Specific reading references are provided in each chapter of the module guide: ¢¢ McKendrick, E. Contract law. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) twelfth edition [ISBN 9781137606495]. ¢¢ Students should also buy the following case book: ¢¢ Poole, J. Casebook on contract law. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017) thirteenth edition [ISBN 9780198732815]. ASSESSMENT Learning is supported by means of a series of activities in the module guide, including self-assessment activities with feedback and multiple choice questions with answers provided on the VLE. These activities test the skills outcomes 5–9. The formative activities also help to prepare students to achieve the module learning outcomes tested in the summative assessment. Summative assessment is through a three hour and fifteen minute unseen examination. Students are required to answer four questions out of eight. The questions include both essay and problem-based questions and test in particular the knowledge outcomes 1–4 and skills outcomes 5–9. Permitted materials Students are permitted to bring into the examination room the following specified document: Core statutes on contract, tort & restitution 2017-18 (Palgrave Macmillan). page vii page viii Notes University of London International Programmes 1 Introduction and general principles Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 1.1 Studying the law of contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 1.2 Reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 1.3 Method of working . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.4 Some issues in the law of contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 1.5 Plan of the module guide . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 1.6 Format of the examination paper . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15 8 page 2 University of London International Programmes Introduction This module guide is designed to help you to study the Contract law of England and Wales. This guide is not a textbook and it must not be taken as a substitute for reading the texts, cases, statutory materials and journals referred to in it. The purpose of the guide is to take you through each topic in the syllabus for Contract law in a way which will help you to understand contract law. The guide is intended to ‘wrap around’ the recommended textbooks and casebook. It provides an outline of the major issues presented in this subject. Each chapter presents the most important substantive aspects of the topic and provides guidance as to essential and further reading. Each chapter also provides you with activities to test your understanding of the topic and self-assessment exercises designed to assist your progress. Feedback to many of these activities is available at the back of this guide. There are also sample examination questions, with appropriate feedback, which will assist you in your examination preparation and quick quizzes to measure your progress, with answers on the virtual learning environment (VLE). The method of study described is the result of the accumulated experience of highly experienced teachers and writers on this topic. Your knowledge of the subject will be maximised when you use this guide in the intended way. Any other approach (e.g. reading the feedback before or alongside the self-assessment) might give false confidence in your knowledge and ability to answer questions under examination conditions. In the study of contract law, it is essential to try to gain an understanding of the underlying basis of contract law – what the law is trying to do in response to particular issues. This is then supplemented and exemplified by a more detailed knowledge of its substantive principles. The rote memorisation of rules and cases alone will not equip you to analyse a legal problem or statement of the sort that form the basis of formative and summative examination in this subject. To do this you need to acquire an overview of the topic, understand its structure, parts and inter-relationships. When this is supplemented by a more detailed knowledge and skills of analysis you will be able to apply the law in written answers that gain maximum credit. To do this it is most likely that you will need to read passages or chapters in the guide (and the relevant suggested reading materials) several times in order to understand the principles of law being covered. Contract law 1 Introduction and general principles 1.1 Studying the law of contract As already stated, this guide is not a textbook nor a substitute for reading the primary materials that comprise the law of contract (i.e. cases and statutory materials). Its purpose is to take you through each topic in the syllabus for Contract law in a way which will help you to understand and apply contract law. It provides an outline of the major issues presented in this subject. It will also help you prepare to answer the kind of questions the examination paper is likely to contain. Note, however, that no topic will necessarily be included in any particular examination and that some are more likely to appear than others. Examination questions may take different forms, though most in the past have been of a traditional ‘problem’ or ‘essay’ style. The examiners are bound only by the syllabus and not by anything said in – or omitted from – this guide. What do we mean by ‘taking you through’ a topic? Very simply it is to spell out what problems or difficulties the law is seeking to provide a solution for and to give a structured guide to the materials (textbooks, cases and statutes). You must read these in order to appreciate how English law has dealt with the issues and to judge how satisfactory the solutions are in terms of overall policy. How to use this module guide Each chapter begins with a general introduction to the topic covered. Following that, the topic is divided into subsections. Each subsection provides a reference to the recommended readings in McKendrick’s textbook and Poole’s casebook (see Section 1.2 below). At a minimum, you should read these; in many cases you will probably find that you need to re-read them. It is often difficult to grasp some legal principles and most students find that they need to re-apply themselves to some topics. In addition, at the end of each chapter, there are recommendations for further reading. This will always cover the relevant chapter in the most appropriate more detailed text. You may find it desirable to review this second textbook from time to time because it is sometimes easier to grasp a point that you have found difficult when it is explained in a different, even if more detailed, fashion. Some recommended readings are also included in the Contract law study pack. Throughout each chapter, self-assessment questions and learning activities are provided. Feedback is also given with regard to the learning activities to allow you to check your comprehension of a particular matter. You will find this process most helpful if you attempt to answer the question before you check the feedback. This approach provides invaluable examination practice. If instead you get into the habit of simply reading the question and then immediately checking the feedback this will not help you improve your question answering technique and may give you a false confidence. The unsubstantiated reflection: ‘oh yes I would have written that in an exam’ is not the same as actually demonstrating that you could have done so. The object of your studies is to understand, rather than memorise, the law. This requires a sufficiently detailed knowledge of the substantive law which you are then able to apply to answer legal questions. At the end of each chapter, some advice is given with regard to possible examination questions on this topic. The fact that this constitutes advice about possible examination questions cannot be stressed enough. The quick quizzes at the end of each chapter are designed to help you reflect on your learning. Again, answer the questions before looking at the answers and feedback on the VLE. The ‘Am I ready to move on?’ section is for you to reflect on what you have learned and ensure you have sufficient knowledge of the areas covered in each chapter before you move on to the next one. There is no feedback for these questions but you should be honest in your self-reflection. The reasons for studying the principles of the law of contract are readily apparent: as individuals we enter and perform contractual obligations every day of our lives and contracts are the foundation of most commercial activity. Many specialist areas of law are built upon a contractual foundation e.g. insurance law, employment law and landlord and tenant law. page 3 page 4 University of London International Programmes Activity 1.1 How many contracts did you think about entering yesterday? Did you enter any contracts yesterday? How many contracts did you (at least partially) perform yesterday? Did any contracts to which you are a party ‘end’ yesterday? If so why did they end? Reflection upon this series of questions will make you aware of how much the law of contract lays behind ‘everyday life’. Perhaps you looked in a shop window or at a website, rang up a shop or business to ask about the availability of some good or service. All of these actions are preparatory to entering a contract. If you purchased any good (newspaper, drink, lunch or shopping) or service (getting on a bus or train with a ticket) you will have entered a contract. Remember that contracts may be formal in the sense of a signed document or informal such as an oral agreement. If you are employed to work you will have (hopefully) performed some contractual duties yesterday. If you ‘returned’ a purchase to a shop or posted it back to an online supplier, if your contract with a mobile network supplier came to an end or you were ‘sacked’ from your employment you have participated in the termination of a contract as a result of breach of contract (returned goods and sacking) or performance (mobile phone). Activity 1.2 Look at a newspaper and identify any stories/subjects/parts which might be better understood with knowledge of contract law or where that area of law is the essential background. How would you describe the ‘status’ of the parties to these contracts? Most newspapers carry advertisements which aim to persuade readers to purchase goods and services. If untrue statements are made (called misrepresentations) the law of contract may provide a remedy to the disappointed purchaser. The business pages will directly discuss lucrative contracts concluded between businesses: perhaps the purchase of valuable TV broadcasting rights or the takeover (by the purchase of shares) of one company by another. Other sections of the newspaper may less obviously ‘involve’ contract law, for example the sports pages may discuss the ‘transfer’ of football players for large sums of money. Such a transfer is of course a contract entered between (at least) the player, and selling and purchasing clubs. Newspaper advertisements are often placed to stimulate sales by a business to consumers (i.e. private individuals); these are known as B2C contracts. The purchase of broadcasting rights and the takeover of companies are concluded between businesses and so are known as B2B contracts. The importance of case law It cannot be too strongly emphasised that the law of contract in England and Wales was established through the decisions of the courts. There are a small number of important statutory provisions. Older statutes such as the Sale of Goods Act 1979 (originally 1893) were themselves codifications of previous case law. More recent statutes have been enacted in order to effect reforms in the law of contract either to implement the recommendations of law reform agencies or as required by particular European Directives. Nevertheless, the law of contract remains predominantly a case law subject and the examiners will, primarily, be seeking to test your understanding of how the judges in the leading cases have formulated and refined the relevant principles of law. You should attempt to read the important cases. The Online Library (which you can access through the student portal) will give you access to the relevant cases. This subject presents an ideal opportunity for you to take the first steps towards developing the essential transferable skills of understanding and applying the judgments of courts and, to a lesser extent, of interpreting statutes. To be explicit, there are no shortcuts to gaining an adequate knowledge of the development of the case law. If the job is to be well done, it will be time consuming. Individuals vary, obviously, but it would probably be exceptional to cover the whole syllabus thoroughly in less than 200–250 hours of study. Contract law 1 Introduction and general principles 1.2 Reading You should begin your reading with this module guide. Start at the beginning and work through the guide sequentially, reading the textbook and doing the activities as directed. Activity 1.3 Review Activity 1.1 above to see if you can identify different stages in a contract, especially a long term one such as a lease or mortgage. A contract, particularly one between parties with equal bargaining power, is often preceded by a period of negotiation. If successful, a contract may be agreed. It must then be performed. If the contractual performance is to take place over a long period of time, altered external circumstances, or the changing preferences of the parties, may result in some agreed modifications. The contract may then end when performance is complete or if it is breached in a serious way, in which case the ‘guilty’ party may be required to pay damages. This highly abbreviated account of the ‘life’ of a contract describes four important stages: negotiation, formation, modification and termination. Since a contract has distinct phases it must be studied and problems analysed in a roughly chronological order. Until a contract comes into existence it is meaningless to talk about its modification or termination. So while it may be tempting to start with, say, illegality or incapacity, this is not a good idea. The subject builds on the basic foundations, without which particular topics later in the subject cannot be understood. You will also derive assistance from the selected readings provided in the Contract law study pack and the Newsletters on the Contract law section on the VLE. No feedback provided. 1.2.1 Books for everyday use The core text for this subject is: ¢¢ McKendrick, E. Contract law. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) twelfth edition [ISBN 9781137606495]. (Referred to in this module guide as ‘McKendrick’.) This text forms the foundation text for this subject. It sets out the law in a clear way and examines all the major issues in reasonable, but not confusing, depth. It is advisable to read and re-read this text to allow the material to be thoroughly understood. You should also buy a casebook. This guide is structured around: ¢¢ Poole, J. Casebook on contract law. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016) thirteenth edition [ISBN 9780198732815]. (Referred to in this module guide as ‘Poole’.) You will find it most beneficial to refer from time to time to the more advanced texts set out in the next section. 1.2.2 More advanced books On occasion you may want to refer to more detailed accounts of the law. Chapters or passages from the following medium and longer length books may be referred to in the Further reading at the end of each chapter. Two ‘medium’ sized accounts by other authors you might wish to use are: ¢¢ Chen-Wishart, M. Contract law. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015) fifth edition [ISBN 978019989163]. ¢¢ Halson, R. Contract law. (Harlow: Pearson, 2013) second edition [ISBN 9781405858786]. The areas covered by the standard textbooks are all very similar. The differences between the various books are in their arrangement, depth, presentation and style. To illustrate: Chen-Wishart above makes extensive use of flowcharts, diagrams and tables while Halson analyses a contract as a transaction with distinct phases. The extent to page 5 page 6 University of London International Programmes which you will choose to refer to textbooks beyond the core text by Mckendrick will depend upon your needs and your liking for the author’s approach and style. The following books contain an even greater depth of discussion. To illustrate this all contract law textbooks will contain a discussion of the so called ‘parol evidence rule’ which states that parties to a written contract may not rely upon evidence outside the contract, usually oral (parol) statements, to contradict the written document. You will soon realise that all legal rules are subject to exceptions though some will be more important than others. McKendrick, the recommended textbook for this subject, describes seven major exceptions to the parol evidence rule. In contrast, the compendious Treitel, below, adds a further 9! ¢¢ Andrews, N. Contract law. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015) second edition [ISBN 9781107660649]. ¢¢ Beatson, J., A. Burrows and J. Cartwright Anson’s law of contract. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016) 30th edition [ISBN 9780198734789]. ¢¢ Furmston, M. Cheshire, Fifoot and Furmston’s law of contract. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017) 17th edition [ISBN 9780198747383]. ¢¢ Peel, E. Treitel: the law of contract. (London: Sweet & Maxwell, 2015) 14th edition [ISBN 9780414037397] (referred to as ‘Treitel’). You may also find it useful to refer to a volume concerned with leading contemporary issues in contract law: ¢¢ Morgan, J. Great debates in contract law. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) second edition [ISBN 9781137481597]. You may also wish to consult a more detailed casebook. Here the choice lies between: ¢¢ Burrows, A. A casebook on contract. (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2016) fifth edition [ISBN 9781509907700]. ¢¢ McKendrick, E. Contract law: text, cases and materials. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016) seventh edition [ISBN 9780198748397]. ¢¢ Brownsword, R. Smith & Thomas: A casebook on contract. (London: Sweet & Maxwell, 2015) 13th edition [ISBN 9780414035324]. It is not suggested that you purchase the books mentioned in this section: they should be available for reference in your college or other library. 1.2.3 Statute books You should also make sure you have an up-to-date statute book. Under the current Regulations you are allowed to take one authorised statute book into the examination room. Information about the statute books and other materials that you are permitted to use in the examination is printed in the current Regulations, which you should refer to. Please note that you are allowed to underline or highlight text in these documents – but you are not allowed to write notes etc. on them. 1.2.4 Other books At the other end of the scale, many shorter books have been published in recent years aimed at the student market. If you are using McKendrick and Poole, you will generally not find that there is much benefit to be gained from these other works. However, for the particular purpose of practising the art of writing examination answers, you may find it helpful to have: ¢¢ McVea, H. and P. Cumper Exam skills for law students. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006) second edition [ISBN 9780199283095]. ¢¢ Finch, E. and S. Fafinski Legal skills (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017) sixth edition [ISBN 9780198784715]. Contract law 1 Introduction and general principles But do not be misled into thinking that any book will provide you with ‘model answers’ which can be learned by heart and reproduced from memory in the examination. From a study of past papers you will be aware that certain broadly defined topics are often examined. However, you will not be able to anticipate the exact questions that will be asked and every examination question requires a specific answer. If you do commit to memory and reproduce ‘pre-packaged’ answers these will be to questions other than the exact question posed. Such answers will contain irrelevant, and omit relevant, material. The criterion of relevance is applied strictly by examiners and so such pre-prepared answers will not score highly. References to the recommended books in the guide This guide is designed for use in conjunction with McKendrick’s textbook and Poole’s casebook. The readings in this module guide were set around the 11th edition of McKendrick’s textbook and the 13th edition of Poole’s casebook. In the event that you have a later edition of the textbook (i.e. a new edition of the textbook publishes before the next edition of this module guide), the subject headings set out in the readings should refer to the relevant portion of a later textbook. For example: ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 11 ‘Exclusion clauses’ – Section 11.7 ‘Fundamental breach’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 8 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 2 ‘Consequences of breach’. 1.2.5 Other sources of information Journals It is useful to consult journals regularly to improve your understanding of the law and to be aware of recent developments in the law. Journals which may prove useful to you for their articles and case notes are: ¢¢ Cambridge Law Journal ¢¢ Journal of Contract Law ¢¢ Legal Studies ¢¢ Law Quarterly Review ¢¢ Lloyd’s Maritime and Commercial Law Quarterly (not available in the Online Library) ¢¢ Modern Law Review ¢¢ New Law Journal ¢¢ Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. Do not worry if you come across material that you do not understand: you simply need to re-read it and think about it. Online resources As mentioned earlier, you will find a great deal of useful material on the VLE and Online Library. These are both accessed through the Student Portal at http://my.londoninternational.ac.uk The Online Library provides access to cases, statutes and journals as well as professional legal databases such as LexisLibrary, Westlaw and Justis. These will allow you to read and analyse most of the cases discussed in this guide and the relevant materials. Students are also able to access newsletters on the VLE that deal with matters of contemporary interest. Use of the internet provides the external student with a great deal of information, as a great deal of legal material is available online. Although the sites change on an almost monthly basis, some useful ones at the time of writing this guide are: page 7 page 8 University of London International Programmes uu www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga provides the full text of UK Acts back to 1991 uu www.parliament.uk the sitemap for the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which will provide you with access to a range of legislative information uu www.lawcom.gov.uk the Law Commission’s website; this provides information about law reform. In addition to these sites, a growing number of private publishers provide legal information and case updates. A site where useful information about recent cases and developments in the law can be found is: uu www.bailii.org Bailii is a freely available website which provides access to case law legislation and also provides a recent decisions list (www.bailii.org/recent-decisions.html) and lists new cases of interest (www.bailii.org/cases_of_interest.html). Several publishers grant access to online resources when a particular textbook is purchased. Examples include Pearson’s My Law Chamber and the online resource centre promoted by Oxford University Press. It should, however, be noted that the extent to which all advertised online resources are kept updated is at present inconsistent. One helpful source of up-to-date practical commentary on recent cases is the websites of the major law firms. If you search under a case name you will likely be directed to some commentary written by a practitioner at one of these firms primarily for the benefit of clients. 1.3 Method of working Remember that your main objective is to understand the principles that have been laid down in the leading cases and to learn how to apply those principles to a given set of facts. As a rule of thumb, leading cases for this purpose may be defined as those which are included in the relevant sections of McKendrick and Poole, together with any other (generally more recent) cases cited in this module guide. At a more practical level the leading cases are those which Examiners would probably expect the well-prepared candidate to know about. In the nature of things, just as different lecturers will refer to a different selection of cases, there can be no absolutely definitive list of such cases. However, there will always be agreement on the importance of many of the cases and in general terms, ‘core’ cases are named in the guide. Space is limited and omission from the guide should not be taken to mean that a case is not worth knowing. It is suggested that the study of the cases should be approached in the following steps. 1. Read the relevant section of this module guide. 2. Read the relevant passages of McKendrick’s textbook and Poole’s casebook – it may also be advisable to examine some cases in full following this. 3. Re-read the relevant passages in McKendrick. 4. Attempt to answer the relevant activities or self-assessment questions. 5. Repeat this process for each section of the module guide. A further description of the process in each of these steps is set out in further detail below. Step 1 Start with the relevant section of this module guide – this will give an idea of the points you need to look for. Take one section at a time – do not try to digest several at once. Step 2 Read the textbook passage referred to. Look in particular for the cases upon which the author places special emphasis. Typically these will be decisions of higher appeal courts such as the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court (formerly the House of Lords). Contract law 1 Introduction and general principles Read the cases in the casebook (together with any others mentioned in the module guide – particularly the more recent ones). You should generally be able to find the case in the Online Library. The importance of reading the primary materials of the law – cases and legislation – cannot be overemphasised. Learn as much as possible about each case. Make a special effort to remember the correct names of the parties, the court which decided the case – particularly if it is a Supreme Court (or House of Lords) or Court of Appeal decision – the essential facts, the ratio decidendi and any important obiter dicta. It is also important to note any other striking features, such as, for example, the existence of a strong dissenting judgment, the overruling of previous authority or apparent inconsistency with other cases. It is most important that you understand not only what the court has decided but also why it has decided that. Knowing ‘the rules’ is not enough: it is essential to study the judgments and understand the reasoning which led the court in a particular case to uphold the arguments of the successful party and reject the contentions put forward – no doubt persuasively – on behalf of the unsuccessful party. It is also important to be critical when studying the cases: ask yourself whether the result produces injustice or inconvenience; whether there are any situations in which you would not want the result to apply and, if so, how they could be distinguished. If it is an older case, you should also ask yourself whether the reasoning has been overtaken by changes in social and commercial life generally. Lastly, pay attention to the impact of other cases in the area. How strong is an authority in light of subsequent decisions? Step 3 Read the textbook passage again and ask yourself, ‘Does the book’s statement of the effect of the cases correspond with my impression of them?’ If it does not, read the cases again. Step 4 You will find activities and self-assessment questions throughout the guide. These are intended not only to build up your knowledge of the material but also to provide you with an opportunity to measure your knowledge and understanding of the particular section. An activity requires you to think about a particular question and prepare an answer which extends beyond a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Feedback is provided for these activities at the end of the guide. Self-assessment questions are designed to test your memory of the material which you have covered. No feedback is provided for these questions as they have sample answers available in the textbook or casebook. With both forms of exercise, you will find that your knowledge is enhanced if you complete the exercises as you encounter them in the particular section. You will note that each chapter of McKendrick also includes some exercises for self-assessment: completing these will further develop your legal knowledge and skills. Step 5 Repeat the process for each section of the chapter in turn. 1.4 Some issues in the law of contract 1.4.1 Statutes Although most of the syllabus deals only with principles developed by the courts, there are also a few statutory provisions which need to be considered because they contain rules affecting contracts generally. Cases and statutes come into existence in different ways and so must be treated differently. Judgments in cases consist of the reported speech of judges and can be very lengthy. The challenge for the reader is often to distil from these long judgments the exact point of law that was applied in the case. Statutory provisions are often short (e.g. the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943 and Misrepresentation Act 1967 have three main sections), yet each effects substantial changes in the law. Statutes are usually written by parliamentary draftsmen, working in pairs, who spend a great deal of time trying to express in as few page 9 page 10 University of London International Programmes words as possible the change in the law they have been instructed to effect. Many weeks might be spent drafting, criticising and then redrafting a single section. Statutes therefore cannot be speed read because every word and even every punctuation mark was inserted for a particular reason. When the topic of misrepresentation is studied you will see that the inclusion of the word ‘so’ in s.2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act effectively dictates the measure of damages available under that section. Therefore, it is suggested that you read and reread statutory sections from the perspective that every word was likely included for a purpose. Ultimately though, we must remember that in English law it is the judges who decide what Parliament meant by the words of the statute. 1.4.2 European Union law The syllabus refers to the inclusion of relevant European Union legislation. The law of contract has not been affected by this legislation to the extent of other areas of law, especially public and human rights, law. At present, the most significant part of the general law of contract which is directly affected by European law is that dealing with consumer rights and unfair terms. For this reason the further effect of ‘Brexit’ (the abbreviation for ‘British exit’ referring to the June 2016 referendum vote by British citizens to leave the European Union) when implemented will not have a great impact upon the general law of contract. The obligation to comply with European legislation derives ultimately from membership of the European Union. However, European Directives may be transposed into domestic law in different ways. This is well illustrated by the European Directive on Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts (93/13 EEC). The first attempt to implement the Directive in domestic law showed a distinct lack of imagination, using the ‘copy out’ technique. The provisions of the Directive were simply repeated, mostly verbatim, in a statutory instrument: the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1994 (SI 1994/ 3159). The ‘copy out’ approach creates many problems as there is no attempt to integrate the measure with the existing domestic law on the subject. These issues of integration were not addressed when the 1994 Regulations were replaced by a new statutory instrument with the same name but a different date in 1999 (SI 1999/2083). As a consequence the Law Commissions of England and Wales and Scotland proposed legislation that integrated the substance of the 1999 Regulations with the existing domestic legislation, principally the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (UCTA 1977). Their basic proposal to ‘tidy up’ this area of law was accepted but their preferred technique of a single domestic statute dealing with unfair contract terms, especially so called exemption clauses (clauses which seek to remove or limit a contractual liability), was not used. Instead, Part 2 of the Consumer Rights Act 2015 revoked the 1999 Regulations and UCTA 1977 in so far as it applied to contracts between businesses and consumers (B2C contracts) and has produced a unified statutory protection for consumers. The provisions of UCTA 1977 will continue to apply to contracts concluded between businesses (B2B contracts). This is an important recent change in the law that will be referred to in more detail at several places in this module guide. The reception into English law of the European Directive on Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts was clearly complex and untidy but also illustrates a more general problem with all European legislation. This arises from the distinct ways in which English and continental courts approach statutory interpretation. Historically, the approach of common law courts has been more narrow, with great emphasis upon the exact words used as opposed to the inherent purpose or ‘spirit’ of the legislative provision. The European Court of Justice follows a continental, or civil law, approach and puts greater emphasis on the underlying purpose of the provision even where this cannot easily be supported by the actual words used. A question arose as to whether the 1994 Regulations applied to contracts for the sale of land. The 1994 Regulations – derived from the English text of the European Directive – referred only to ‘goods’ and ‘services’ and not to land. The usual English approach to legislative interpretation would lead to the conclusion that contracts for the sale of land were not covered by the Regulations. However, the French text of the Directive referred to the ‘vendeur de biens’ which Contract law 1 Introduction and general principles would cover a seller of goods or land. In London Borough of Newham v Khatun [2004] EWCA Civ 55 the Court of Appeal avoided the possibility of different interpretations of the same Directive being upheld in different member countries and held that the Regulations (and so by inference now the Consumer Rights Act 2015) apply to contracts for the sale of land. The episode illustrates the difficulties that can arise from the implementation of EU law. 1.4.3 A law of contract or a law of contracts? The law of contract described in this guide consists of many principles of general application. In this sense we can say that there is a single law applicable to all types of contract. However, in many specialised areas these general principles are disapplied and supplemented by specific extra rules. For this reason, authors write books which focus upon particular contracts only (e.g. the contract of employment, charters of ships, contracts to lease land). Indeed, this process of fragmentation is exactly what was mentioned above where the law on unfair contract terms could be described as now comprising consumer contract law (for B2C contracts) and business contract law (for B2B contracts). However, it is important to realise that this is not a one way process. Over recent years there has been evidence of an increasing contractualisation of the relationship between the individual and the state (e.g. the introduction of a market for healthcare where health authorities and fundholding doctors’ practices purchase healthcare from private and NHS trust hospitals). Consequently, it is not possible to say whether we have a law of contract or a law of contracts. It might be safer to say simply that the general principles of contract remain important both as a part of more specific contract regimes and also as the ‘default’ law applicable to contracts which are not regulated in a special way. 1.4.4 The real world This module guide describes the legal rules that collectively make up the law of contract. However, you should be careful when making inferences based upon those rules as to how contractors behave in the real world. The small number of empirical studies that have been undertaken to investigate the actual behaviour of contractors reveal that they are frequently more co-operative and flexible than the formal legal rules would seem to anticipate. In the first such study, Stewart Macaulay described the views of manufacturing companies in Wisconsin. His conclusion, confirmed by the small number of other empirical studies, was that some of the usual assumptions made about contractors’ actions and the effects of legal rules ‘are just wrong or …greatly overstated…’. In general, contractors are more flexible and accommodating to changing circumstances and preferences than might be expected. Another American commentator, Ian MacNeil, pithily summarised the behaviour of contractors: ‘they do not go for the jugular when trouble arises’. 1.4.5 The ‘consensus’ theory of contract and objective interpretation In the past, many writers and courts placed much emphasis on the need for a ‘meeting of minds’ or ‘consensus ad idem’ for the making of contracts. This reliance on actual intention was an expression of laissez-faire philosophies and a belief in unfettered freedom of contract. This subjective approach to the making of contracts has now largely been abandoned, though its influence can still be detected in certain rules. In general, what matters today is not what meaning a party actually intended to convey by his words or conduct, but what meaning a reasonable person in the other party’s position would have understood him to be conveying. This is known as the process of ‘objective interpretation’. When analysing contractual problems judges often reflect in their speech the subjective approach: they speak of trying to discover the intention of the parties. However, it is crucial to understand that this intention is ascertained objectively. My intention is taken to be not what I secretly intend but what a reasonable interpretation of my words and deeds would suggest I am intending. For example, I offer to sell you ‘my car for £10k’ while I am sitting on the bonnet of a Ford Fiesta. You agree to buy ‘my car for £10k’. I then go round the corner and bring back an old wreck page 11 page 12 University of London International Programmes of a car worth £200 which I tell you is the only car I own. The law would, in words usually attributed to Charles Dickens, be an ‘ass’ if on these facts you had entered a contract to buy the old wreck for £10k; fortunately it is not and you have not. The contractual offer I will be held in law to have made is not the one that I secretly intend (i.e. to sell the car round the corner), but rather is the offer that a reasonable individual would think I was making (i.e. to sell the car which I was sitting on at that time). 1.4.6 Law and equity At one time in England and Wales, there were two separate court systems which dealt with contract cases: courts of equity and courts of common law. In the latter part of the 19th century, these two courts were amalgamated and one court dealt with both law and equity. Equity had developed its own principles, considerations and remedies to contractual problems. Equity is said to supplement the common law where it is deficient. In the course of studying contract law you will see many equitable principles in place (see, for example, estoppel, undue influence and the remedy of ‘specific performance’, the courts’ order that the promisor perform the actual obligation undertaken). Equitable intervention in a contractual problem is based on the conscience of the parties; accordingly, equitable relief is discretionary and may be more flexible. Some legacies of this old distinction remain (e.g. with respect to the remedies available for breach of contract). The primary remedy, an award of damages, which originated in the common law courts, is said to be available as of right. In contrast, specific performance, which originated in the courts of equity, is said to be available at the court’s discretion. The availability of equitable relief is bound by a distinct series of considerations sometimes referred to as a maxim. One such maxim is that ‘he who comes to equity must come with clean hands’; that is to say, he who seeks equitable relief must himself not be guilty of some form of misconduct or sharp practice. You will see the particular restrictions placed upon the granting of equitable relief as you proceed through the module guide (see, for example, rescission for misrepresentation). 1.4.7 Human rights and contract law From October 2000 the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), which incorporates into English Law the European Convention on Human Rights, has had legal effect. The HRA creates Convention Rights (CRs) which are enforceable under domestic law. The main rights are: protection of property; right to life; prohibition of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment; prohibition of slavery or forced labour; the right to liberty/security; right to a fair trial and hearing, and no punishment without lawful authority; respect for private/family life, home and correspondence; freedom of thought, conscience and religion; freedom of expression; freedom of assembly/association; freedom to marry; and prohibition of discrimination in enjoyment of CRs. The wide ranging freedoms which are guaranteed by the HRA might have a considerable impact upon the law of contract depending on their so called ‘horizontal’ effect. HRA s.6(1) provides that it is ‘unlawful for a public authority to act in a way that is incompatible with a Convention Right’ and so clearly applies to the relationship, including a contractual one, between a public body and an individual. The extent to which the HRA will have impacted upon the law of contract is related to the extent that the HRA has a horizontal effect (i.e. to the extent that it affects relationships, including contractual ones between individuals, including companies). It has so far been recognised that CRs have some horizontal effect (e.g. the House of Lords has recognised that the Article 3 right to respect for private and family life required that legislation regarding the succession to rented property must be applied in the same way to same sex relationships as it is to heterosexual relationships). The precise extent of the horizontal effect of the HRA is a contentious issue. Further development of the extent of horizontal effect will, if it occurs, increase the importance of human rights protection upon the law of contract. An example of how the HRA’s protection of CRs has affected contracting activity is provided by the Court of Appeal’s recent decision in Dept of Energy and Climate Contract law 1 Introduction and general principles Change (DECC) v Breyer Group plc [2015] EWCA Civ 408. When the DECC introduced a subsidy scheme designed to encourage the small scale generation of electricity from renewable resources it underestimated the likely ‘take-up’, and so the cost to the Government, of the scheme. The DECC, contrary to earlier commitments, sought to save £1.6 billion by reducing the level of subsidy to be paid for electricity produced from such sources. Companies supplying this technology claimed that they had suffered £195 million losses through abandoned installations. The Court of Appeal held, based upon assumed facts, that the implementation of the changes had unjustifiably interfered with the companies’ right to the protection of property guaranteed by Article 1 of the First Protocol of the European Convention on Human Rights (known as an A1P1 right) and so, in principle, those companies affected were entitled to damages. 1.4.8 The codification of contract The English law of contract is found in the decisions of the courts supplemented by a small number of statutory measures, some of the latter which have their origins in European Directives. The domestic law applicable in many European countries is so called ‘civil’ law derived from Roman law. Figure 1.1 A map of the world’s different legal families Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LegalSystemsOfTheWorldMap.png A distinctive feature of these systems is the place of ‘codes’ which in an authoritative way state the law on a particular topic such as contract or tort: in France the code civil established under Napoleon 1 in 1804 and so known as the Napoleonic Code and in Germany the Burgerliches Gesetzbuch (the ‘BGB’). The idea of a single source for all the legal principles on a topic has an instant, but misleading, appeal. A code is not able to provide for all possible cases and circumstances. Rather its necessarily general principles must subsequently be interpreted by courts before they are applied in concrete cases. The need to refer to such interpretations and the different stances that may be taken complicate the original code. This was acknowledged by Napoleon himself who, when the first commentary on his code was published, is claimed to have said: ‘Mon Code est perdu’ (My Code is lost). The only common law jurisdictions in Europe are England and Wales, Cyprus and Ireland (Scotland is a mixed (i.e. common law and civil law) jurisdiction). With civil law jurisdictions in the majority it was perhaps inevitable that there would be pressure to enact a single contract code for all of Europe. To this end the private work of page 13 page 14 University of London International Programmes collections of lawyers aimed at producing such a code, the best known being Lando’s Principles of European Contract Law (the ‘PECL’). This work was eventually supported and endorsed by the European Commission with strong support from the European Parliament. After other initiatives in 2011, 10 years after its first communication on contract law, a Regulation on a Common European Sales Law (CESL) was published by the European Commission in order to facilitate contracting across national boundaries. Current trade within the EU is said to be worth over €2 trillion. It was asserted that different national systems of contract law impeded such trade and so the potential gains from codification, especially in the context of European economic recovery, seemed great. However, this potential reduction in transaction costs is illusory for two reasons. The imposition of a single contract law in Europe is not politically possible. Therefore, what has been proposed is an optional code that parties may choose to adopt. The illusory nature of any supposed transaction cost saving is clear when it is realised that the proposal, instead of replacing the 28 current domestic contract regimes with a single new system, instead introduces a further (i.e. 29th) possible contract framework. An interesting perspective on this debate is provided by the World Bank’s annual Doing Business survey which compares the ease of doing business in 190 countries. This is judged by reference to 10 metrics including enforcing contracts and trading across borders. Although common law jurisdictions comprise less than 20 per cent of the countries surveyed, nevertheless five of the top eight rated countries for ease of doing business were common law based (Singapore, New Zealand, Hong Kong, US and UK) in the latest 2017 survey. In contrast, the major European civilian jurisdictions of France and Germany ranked respectively 29th and 17th. This preference on the part of business for common law, noncodified, systems of law would appear to further support arguments against the codification of contract law across Europe. It is perhaps not surprising that the scope of the CESL has subsequently been reduced and will only apply in the main to distance and online contracts and even then only if the parties so choose. A different approach to codification is provided by the Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits (the Uniform Customs). The Uniform Customs apply only to one particular type of commercial contract – called a documentary credit – which is a guarantee provided by a buyer’s bank to the supplier of goods that the price will be paid so long as specified documents are tendered. The Uniform Customs which were drafted by the International Chamber of Commerce are possibly the most successful example of contract codification in existence. The standard form of documentary credit supported by the Uniform Customs is almost universally adopted. The most successful general contract code is probably the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (known as either the Vienna Convention or CISG). Once this Convention is ratified by a country it will apply to all transactions for the international sale of goods to which that jurisdiction’s law would apply unless the contract specifically provides otherwise; it is an ‘opt out’ rather than an ‘opt in’ measure. All the major trading nations except one have ratified the CISG including the US, China, France and Germany. The only major trading nation that has chosen to resist ratification is the UK. 1.5 Plan of the module guide In line with the order of topics in the syllabus, the guide is structured as follows. uu Part I of the guide deals first with the requirements for the making of a contract (Chapters 2, 3 and 4). uu Part II deals with the content of a contract and some of the regulations of the terms of a contract (Chapters 5 and 6). uu Part III deals with the capacity to contract – the emphasis placed is upon minors’ contracts (Chapter 7). Contract law 1 Introduction and general principles uu Part IV deals with vitiating elements in the formation of a contract (Chapters 8, 9 and 10). uu Part V deals with the question of who can enforce the terms of a contract (Chapter 11). uu Part VI deals with illegality and public policy (Chapters 12 and 13). uu Part VII deals with the discharge of a contract (Chapters 14 and 15). uu Part VIII deals with remedies for a breach of contract (Chapters 16 and 17). Topics not included in the syllabus Although the following topics are touched upon in the recommended books (and covered in some detail in the larger books), they are excluded from the present syllabus. uu Requirements as to the form of contracts. uu Gaming and wagering contracts. uu Assignment (including negotiability). uu Agency. 1.6 Format of the examination paper Important: the information and advice given here are based on the examination structure used at the time this guide was written. Because of this we strongly advise you to always check both the current Regulations for relevant information about the examination, and the VLE where you should be advised of any forthcoming changes. You should also carefully check the rubric/instructions on the paper you actually sit and follow those instructions. Past examination papers can be a useful pointer to the type of questions which future papers will probably include, but you should take care not to read too much into the style and format of past papers. Remember that, in this as in other subjects, the examiners may change the format from year to year – for example, by requiring a different number of questions to be answered, by splitting a paper into Part A and Part B (with some questions to be answered from each part) or by making some questions compulsory. You must always read and comply with the instructions for the particular paper you are taking. The annual Programme handbook will normally give advance warning of major changes in the format of question papers, but the examiners will have no sympathy with a candidate who does not read the instructions properly. 1.6.1 Difficult facts Many of the older cases that you will study conveniently arise from a simple set of facts. One of the most celebrated cases you will encounter involves the sale of a ‘quack’ medicine, consumption of which was ‘guaranteed’ to avoid the catching of influenza (the flu) (Carlill v Carbolic Smokeball Co [1893] 1 QB 256). Students rapidly develop an understandable preference for such cases where the factual background is easy to understand and the application of law to those straightforward facts simple to follow and relate. Litigation is, however, very expensive and cases rarely reach appellate courts unless the sums at stake are very large and such large commercial disputes rarely arise from simple sets of facts. An important skill to practice and develop is how to summarise such complex sets of facts. Commercial disputes often involve multiple parties and you may find, as most law teachers do, that it is easier to understand such facts if you draw a diagram. This should help you to focus upon what the case is really about and the relevant legal doctrine. page 15 page 16 University of London International Programmes Pao On Subsidiary (Indemnity) Agreement Lao Yiu Long Fu Chip Shares Main agreement Factory Shing On Shing On Shares Fu Chip Figure 1.2 Pao On v Lau Yiu Long [1980] AC 614 presents as challenging a set of facts as you will meet. Yet the case is really about a simple issue: the purchase of a factory by an individual called Lao Yiu Long. However, this transaction was effected in a complicated way. The factory was the principal asset of a private company called Shing On which was owned by Pao On. A contract (the main contract) was entered to exchange all the shares in Shing On (and so transfer the factory) in exchange for a large number of shares in Fu Chip, a public company in which Lao Yiu Long was a major shareholder. The legal issue in the case was whether a subsidiary agreement (called an indemnity) was enforceable under which Lao Yiu Long agreed to make good any losses that were caused by a fall in the value of Fu Chip shares before Pao On was entitled to sell them. The last three sentences are a summary of the facts of a case which are stated over many pages of the law report. It is a summary that most law teachers can only assimilate with the use of a simple diagram such as that above. You should not produce such a diagram in an examination answer but it is a valuable aid to study. 1.6.2 ‘Spotting’ questions As we mentioned at the beginning of this Introduction, there is no guarantee that there will be a question on any particular topic in any given examination paper. It is a mistake, therefore, to assume that topic A is so important that the examiners are bound to set a question on it. You should bear this in mind when deciding how many topics you need to have thoroughly revised as you go into the examination. It is also worth noting that questions may easily involve more than one topic. 1.6.3 Examination technique in general Make the most of your knowledge by observing a few simple rules: 1. Write legibly, using a good dark pen. If necessary, write more slowly than normal to improve legibility. If the examiners cannot read what you have written there is nothing for them to mark. You may as well have left the answer book empty. 2. Read the question carefully and at least twice. Look for hints as to the particular issues the examiners hope you will discuss. Think about what the examiners are asking you to do: what is the question about? Treat it like a passage in a foreign language. When ‘translating’, the sense of the text you are reading becomes much clearer on the second reading. This also helps to avoid misreading. Read the rubric or instruction many times. Sometimes it is broad (e.g. Discuss or Advise X), but sometimes it is directed. Never start writing before you have finished reading, Contract law 1 Introduction and general principles even if the person at the next desk has already completed one page of writing. It is not the quantity you write but how well you analyse the question and identify the relevant issues that will determine the quality of your answers. 3. Complete the required number of questions, including all parts of questions with two or more parts. 4. Poor timing is the main cause of students not achieving their full potential. Plan your time so that you spend about the same amount of time on each question. One of the worst mistakes you can make is to overrun on the first two answers: you are not likely to improve much on the quality of those answers and you will only increase the pressure and tension while you are trying to finish the other questions with inadequate time remaining. 5. Make sure that you answer the question which the examiners have asked. It is often very inconsiderate of examiners not to ask the question you wanted them to ask. However, never be tempted to answer the question you would have preferred them to ask. The criterion of relevance is applied mercilessly: only relevant material gains credit. There are no consolation marks. Think carefully about what the question asks of you and provide an answer to that question – not to a related (or even worse, unrelated) topic. 6. It is very important to plan out your answer in a rough form (on separate pages) before you begin to write your answer. An essential technique is to write out a ‘shopping list’ of the points – and the cases – which you intend to cover. If there is a significant chronology in the question, make a list of the sequence of events with their dates/times. You should develop a logical order of presenting your points: many points will have to precede others. 7. Begin your answer with a very short but focused introduction. Show confidence here as first impressions are important. ‘This question concerns whether certain promises are enforceable’ is bad, whereas, ‘This question concerns the modification, as opposed to the creation or termination, of contractual obligations. More particularly it considers the enforceability of contractual modifications which have the effect of either enlarging (‘increasing’ modifications) or decreasing (‘reducing’ modifications) the obligations assumed by one party under the original contract. The doctrines of consideration and economic duress will be discussed in relation to increasing modifications and the doctrine of promissory estoppel in relation to reducing ones.’ is good. 8. Remember above all that the examiners are particularly interested in how well you know the case law: always try to argue from named cases. Give an accurate and concise account of the ratio decidendi and, if relevant, obiter dicta of the cases you mention. 9. A good answer has balance. On the one hand it avoids the needless duplication of authorities to support settled propositions of law but also investigates in detail areas of open texture where the law is uncertain. In order to achieve this balance you might find it helpful to distinguish points from issues. A problem raises a point if it is directly covered by a case or statute which may be complicated but over which there is little or no doubt. A problem raises an issue where either no case or statute directly covers the problem, or where conflicting or unclear cases or statutory provisions need to be considered. Issues justify more lengthy treatment than points. 10. Repetition of the facts of the problem gets no credit and irritates the examiners who think you believe they cannot read! Also do not waste time setting out the whole of the law on a topic when the question is only about part of it. Irrelevant material not only earns no marks but actually detracts from the quality of the answer as a whole. page 17 page 18 University of London International Programmes 11. Remember that arguments – the exploration of possibilities – are more important than conclusions, so you should not feel obliged to come down too firmly on one side nor should you be inhibited by the fact that you are not sure what the ‘correct’ answer is. It is in the nature of the English system of judicial precedent that there is nearly always room for argument about the scope of a previous ruling, even by the House of Lords or Supreme Court, so that it is quite possible, even likely, that more than one view is tenable. It is far better to put forward a reasoned submission which the examiners may perhaps disagree with than to try and dodge the issue by saying – as surprisingly many candidates do – ‘As the law is unclear (or, the authorities are conflicting) it will be for the court to decide’. Remember, it is important to check the VLE for: uu up-to-date information on examination and assessment arrangements for this module uu where available, past examination papers and Examiners’ reports for the module which give advice on how each question might best be answered. Enjoy your studies – and good luck. Part I Requirements for the making of a contract 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20 2.1 The offer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 2.2 Communication of the offer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 2.3 Acceptance of the offer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 2.4 Communication of the acceptance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 2.5 Exceptions to the need for communication of the acceptance . . . . . . 27 2.6 Method of acceptance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30 2.7 The end of an unaccepted offer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39 page 20 University of London International Programmes Introduction The law of contract defines the circumstances when a promise or promises are enforceable. However, not all promises are enforced by courts. For a promise or promises to be initially enforceable as a contract certain elements must be present. There must be: uu agreement, constituted by a corresponding offer and acceptance, supported by uu consideration, being the mutual exchange of something which the law recognises as having a value and uu an intention to create legal relations. These are cumulative requirements (i.e. each must be present for a contract to exist). However, the identification of a contract by reference to these elements is sometimes a somewhat artificial process. Sometimes, courts will find that some agreements simply look like contracts and they then reason backward – and find the elements necessary to form a contract. The process of agreement begins with an offer. An offer may be addressed to a single person or to many people. For a contract to be formed, this offer must be unconditionally accepted. The law imposes various requirements as to the communication of the offer and the acceptance. Once there has been a valid communication of the acceptance, the law requires: uu consideration (covered in Chapter 3) and uu an intention to create legal relations (covered, alongside other sometimes applicable requirements, in Chapter 4). If these elements are not present, a court will not find that a contract exists between the parties. In the absence of a contract, neither party will be bound to the tentative promises or agreements they have made. It is thus of critical importance to determine whether or not a contract has been formed. An important distinction is that between a ‘unilateral’ and a ‘bilateral’ contract. A unilateral contract is an exchange of a promise for an act. A typical unilateral contract would be the offer of a reward for the return of lost property. It is a frequent, but not a necessary, feature of a unilateral contract that the offer, such as that of a reward, is made to a large group of people. As a unilateral contract, by definition, involves a promise by one party only it follows that it generates an obligation for one party only. The offer of a reward for the return of lost property does not oblige anyone to look for that property. The only obligation it creates is a contingent one upon the offeror to pay the stipulated reward to any person who chooses to perform the stipulated act (i.e. return the lost property). In several respects the rules of offer and acceptance discussed below are modified in the case of unilateral contracts (see especially Section 2.7.1 below). Learning outcomes This chapter introduces the topic of contractual agreement to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The definition of a contractual offer. uu The distinction between a unilateral and a bilateral offer. uu The difference between an offer and other communications. uu The moment of effective communication of an offer. uu What is (and is not) a valid acceptance. uu The requirement of communication of acceptance and its exceptions. Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance 2.1 The offer Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 3 ‘Offer and acceptance’ – Section 3.1 ‘Offer and invitation to treat’ to Section 3.7 ‘Acceptance’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 2 ‘Agreement’ – Section 1 ‘Subjectivity versus objectivity’ to Section 4 ‘Acceptance’. 2.1.1 What offer? It is important to remember (see Section 1.4.3) that it is not the subjective intentions of the parties that determine the legal effect of their words or actions but the reasonable inference that they would support. This is the so called ‘objective’ theory of agreement associated with Smith v Hughes (1871) and more recently summarised in the Supreme Court by Lord Clarke (RTS Flexible Systems Ltd v Molkerei Alois Muller Gmbh & Co KG [2010] UKSC 14 at [45]. Whether there is a binding contract between the parties and, if so, upon what terms depends… not upon their subjective state of mind, but upon a consideration of what was communicated between them by words or conduct, and whether that leads objectively to a conclusion that they… had agreed upon all the terms which they regarded…as essential. This approach was applied in Centrovincial Estates v Merchant Investors Assurance Co [1983] Com LR 158 where the claimants had bought commercial premises let to the defendants for a rent of £68,320 pa subject to review. When the claimants mistakenly proposed a new rent of £65k pa instead of the £126k pa they intended to propose, the defendants predictably ‘accepted’ the mistaken offer. The claimants argued that no reasonable tenant would have expected the rent to be reduced; the defendants responded that this was a reasonable expectation in light of their communicated dissatisfaction with the previous letting. The Court of Appeal accepted the defendants’ arguments that it was at least arguable that an offer to let premises for £65k pa meant exactly that. Subsequent cases have made explicit that in a so called B2B contract (i.e. between two businesses) the interpretation of an offer upon which the offeree is entitled to rely is that of a hypothetical and reasonable businessman in the position of the offeree (Dhanani v Crasnianski [2011] All ER (Comm) 799). It should be noted, however, that there is one circumstance when the courts will depart from the usual objective approach and take account of the actual subjective knowledge of the offeree. Under this approach, sometimes known as the ‘snapping up’ doctrine, an offeree is not allowed to accept an offer which he knows is mistaken as to its terms (Hartog v Collins and Shields [1939] 3 All ER 566). This last factor is important and is what limits the scope of this disapplication of the usual objective approach. It is not enough to come within this exception that the offeree was aware that the offeror had made a mistake; the exception will only apply where the offeree is aware that the offeror is mistaken as to the terms he intended to offer (Statoil ASA v Louis Dreyfus Energy Services LP (The ‘Harriette N’) [2008] EWHC 2257 (Comm)). The doctrine will apply both where, as in Hartog, the offeree is aware of the offeror’s mistake as to the terms he is offering but also where, as in Scriven Bros v Hindley [1913] 3 KB 564, the offeree should know that the offeror is mistaken as to the terms he has offered perhaps because, as in Scriven, the offeree induced that mistake by his own carelessness (in Scriven, contrary to accepted trade custom, marking two distinct commodities with the same shipping mark). 2.1.2 Offers and invitations to treat An offer is an expression of willingness to contract on certain terms. It must be made with the intention that it will become binding upon acceptance. There must be no further negotiations or discussions required. The nature of an offer is illustrated and encapsulated by two cases involving the same defendant, Manchester City Council. page 21 page 22 University of London International Programmes The Council decided to sell houses that it owned to sitting tenants. In two cases, the claimants entered into agreements with the Council. The Council then resolved not to sell housing unless it was contractually bound to do so. In these two cases the question arose as to whether or not the Council had entered into a contract. In one case, Storer v Manchester City Council [1974] 3 All ER 824, the Court of Appeal found that there was a binding contract. The Council had sent Storer a communication that they intended would be binding upon his acceptance. All Storer had to do to bind himself to the later sale was to sign the document and return it. In contrast, however, in Gibson v Manchester City Council [1979] 1 All ER 972, the Council sent Gibson a document which asked him to make a formal invitation to buy and stated that the Council ‘may be prepared to sell’ the house to him. Gibson signed the document and returned it. The House of Lords held that a contract had not been concluded because the Council had not made an offer capable of being accepted. Lord Diplock stated: The words ‘may be prepared to sell’ are fatal … so is the invitation, not, be it noted, to accept the offer, but ‘to make formal application to buy’ on the enclosed application form. It is …a letter setting out the financial terms on which it may be the council would be prepared to consider a sale and purchase in due course. A key distinction between the two cases is that in Storer’s case there was an agreement as to price, but in Gibson’s case there was not. In Gibson’s case, important terms still needed to be determined. It is very important to realise from the outset that not all communications will be offers. They will lack the requisite intention to be bound upon acceptance. If they are not offers, what are they? At this point, we will distinguish an offer from other steps in the negotiation process. Other steps in the negotiation process might include a statement of intention, a supply of information or an invitation to treat. We will examine these in turn. A statement of intention In this instance, one party states that he intends to do something. This differs from an offer in that he is not stating that he will do something. The case of Harris v Nickerson [1873] 37 JP 536 illustrates this point. The auctioneer’s advertisement was a statement that he intended to sell certain items; it was not an offer that he would sell the items. 2.1.3 A supply of information In this instance, one party provides information to another party. He supplies the information to enlighten the other party. The statement is not intended to be acted upon. See Harvey v Facey (1893) where one party telegraphed, in response to the query of the other, what the lowest price was that he would accept for his property, if he were to sell it. This alone did not imply an assurance that he would sell at this price. 2.1.4 An invitation to treat This is a puzzling term. An invitation to treat is an indication of a willingness to do business. It is an invitation to make an offer or to commence negotiations. Courts have considered whether or not a communication was an offer or an invitation to treat in a wide variety of circumstances. You should examine the following instances where courts have found that the communication was not an offer but an invitation to treat. a. A display of goods is generally an invitation to treat. See Pharmaceutical Society v Boots [1953] 1 QB 401 (note the rationale behind treating the display as an invitation to treat rather than as an offer) and Fisher v Bell [1961] 1 QB 394. In contrast, where the display is made by a machine, the display will probably be an offer (Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking [1971] 2 QB 163). Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance Activity 2.1 Your local grocery shop places a leaflet through your letterbox. On the leaflet is printed ‘Tomorrow only, oranges are at a special low, low price of 9p/kilo’. Has the grocery shop made you an offer? If you visit the shop, must they sell you oranges at this price? b. An advertisement is an invitation to treat where a bilateral contract is anticipated. Figure 2.1 Partridge advertised ‘Bramblefinch cocks, Bramblefinch hens, 25s ea’ See Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 2 All ER 421 – the advertisement of a bilateral contract. Where, as in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company [1893] 1 QB 256, a unilateral contract is contemplated the advertisement may be an offer. See the Introduction above for the distinction between unilateral and bilateral contracts. By way of background you should be aware that the broader law of consumer protection prohibits misleading advertisements. In particular, the Unfair Trading Regulations 2008/1277, Part 2, prohibits misleading advertisements aimed at consumers. The European Court of Justice has said that it would be a breach of European consumer protection law if in a shop a consumer was refused a product under the advertised terms (Trento Svilippo srl v Autorita Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato [2014] 1 All ER (Comm) 113). Activity 2.2 How were the facts of Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company different from the usual situation involving an advertisement? c. A request for tenders is an invitation to treat and the tender is the offer. See Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Co of Canada Ltd [1985] Ch 103. Note, however, that the invitation to treat may contain an implied undertaking to consider all conforming tenders, as in Blackpool and Fylde Aero Club Ltd v Blackpool Borough Council [1990] 3 All ER 25. d. An auctioneer’s request for bids is an invitation to treat. The bid is an offer; when the auctioneer brings his hammer down he has accepted the offer. In the case of auctions without a reserve price, the auctioneer enters into a collateral (or separate) contract. The nature of the collateral contract is that the auctioneer will accept the highest bid. See Warlow v Harrison [1859] 1 E&E 309 and Barry v Davies [2000] 1 WLR 1962. page 23 page 24 University of London International Programmes Figure 2.2 The advertisement for Carbolic Smoke Balls Activity 2.3 A store mistakenly advertised Sony televisions for sale on its website for £2.99 each rather than the £299 they intended. Has the store entered a contract to supply the televisions at the mistaken price with customers who purported to ‘buy’ the TVs online? Self-assessment questions 1. How does an invitation to treat differ from an offer? 2. Does a railway or airline timetable constitute an offer? 3. Do courts treat the display of goods in a shop window differently from a display in an automated machine and if so, how? Summary A contract begins with an offer. The offer is an expression of willingness to contract on certain terms. It allows the other party to accept the offer and provides the basis of the agreement. An offer exists whenever the objective inference from the offeror’s words or conduct is that she intends to commit herself legally to the terms she proposes. This commitment occurs without the necessity for further negotiations. The first step in finding a contract is to establish that there is an offer and who is making it. Many communications will lack this necessary intention and thus will not be offers. They may be statements of intention, supplies of information or invitations to treat. Although the distinction between an offer and other steps in the negotiating process is easy to state in theory, in practice, difficult cases arise. Further reading ¢¢ Winfield, P.H. ‘Some aspects of offer and acceptance’ (1939) 55 LQR 499. Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance 2.2 Communication of the offer Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 3 ‘Offer and acceptance’ – Section 3.9 ‘Acceptance in ignorance of the offer’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 2 ‘Agreement’ – Section 4C ‘Acceptance must be made in response to the offer’. To be effective an offer must be communicated: there can be no acceptance of the offer without knowledge of the offer. The reason for this requirement is that if we say that a contract is an agreed bargain, there can be no agreement without knowledge. There can be no ‘meeting of the minds’ if one mind is unaware of the other. Stated another way, an acceptance cannot ‘mirror’ an offer if the acceptance is made in ignorance of the offer. The authorities are, however, divided on the need to communicate the offer. In Gibbons v Proctor (1891) it seems as if a policeman was allowed to recover a reward when he sent information in ignorance of the offer of reward. The better view is thought to be expressed in the Australian case of R v Clarke [1927] 40 CLR 227: there cannot be assent without knowledge of the offer; and ignorance of the offer is the same thing whether it is due to never hearing of it or forgetting it after hearing. The case of Tinn v Hoffman [1873] 29 LT 271 deals with the problem of cross-offers. Activity 2.4 How might the decision have been different in R v Clarke if Clarke had been a poor but honest widow? 2.3 Acceptance of the offer Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 3 ‘Offer and acceptance’ – Section 3.7 ‘Acceptance’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 2 ‘Agreement’ – Section 4 ‘Acceptance’. For a contract to be formed, there must be an acceptance of the offer. The acceptance must be an agreement to each of the terms of the offer. A communication which falls short of this e.g. by merely expressing gratitude for ‘instructions’ will not constitute acceptance (Arcadis Consulting v AMEC (BSC) [2016] EWHC 2509 (TCC)). It is sometimes said that the acceptance must be a ‘mirror image’ of the offer. See also Reveille Independent LLC v Anotech International (UK) Ltd [2016] EWCA Civ 443 where it was held that a draft agreement was accepted by subsequent conduct that sufficiently indicated assent to its terms even though the draft expressly stated that it was only binding when signed. Contractual acceptance, like a contractual offer, is established objectively. So acceptance occurs when the offeree’s words or conduct give rise to the objective inference that the offeree assents to the offeror’s terms. The acceptance can be by words or by conduct. See Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Company (1877), where the offeree accepted the offer by performance and Claxton Engineering Services Ltd v TXM Olaj-ES Gazkutato KFT (2010) where the choice of a Hungarian company to continue trading with its English counterpart after the latter had rejected a proposal for the arbitration in Hungary of any disputes was held to be an acceptance of the English company’s counter offer that the resolution of disputes should be subject to English jurisdiction only. If the offeree attempts to add new terms when accepting, this is a counter-offer and not an acceptance. A counter-offer implies a rejection of the original offer, which is page 25 page 26 University of London International Programmes thereby destroyed and cannot subsequently be accepted. See Hyde v Wrench (1840) 49 ER 132. Where the offeree queries the offer and seeks more information, this is neither an acceptance nor a rejection. It is merely an enquiry as to whether the offeror would be prepared to vary the offer and the original offer stands. See Stevenson, Jacques & Co v McLean [1880] 5 QBD 346. The majority of the Court of Appeal in Butler Machine Tool v Ex-Cell-o [1979] 1 All ER 965 held that the ‘last shot’ wins this ‘battle of the forms’. The minority judgment of Lord Denning MR in Butler criticised the ‘all or nothing’ approach of the old ‘mirror image rule’ whereby a contract was concluded on either the buyer or the seller’s terms. He preferred to look at the communications as a whole and hold there to be a contract when there is substantial agreement on all material points. If the remaining differences are irreconcilable Lord Denning thought they should be replaced by ‘reasonable implication’. Lord Denning’s radical approach has not been followed elsewhere and in Tekdata Interconnections Ltd v Amphenol Ltd [2009] EWCA Civ 1209 the Court of Appeal reasserted the traditional approach emphasising the importance of certainty in commercial transactions. If it is found that there is no contract between the parties it does not follow that they will not have to pay for any benefits received. A different branch of the civil law of obligation, known as the law of restitution, may impose on the recipient of a benefit an obligation to pay something to the party who conferred that benefit irrespective of whether a contract comes into existence to bind the two parties (BSC v Cleveland Steel [1984] 1 All ER 504). Note, also, that in some cases courts have held that particular relationships are not capable of contractual analysis. In The Eurymedon [1975] AC 154 Lord Wilberforce noted that English law ‘having committed itself to a rather technical and schematic doctrine of contract’ nevertheless ‘takes a practical approach, often at the cost of forcing the facts to fit uneasily into the marked slots of offer, acceptance…’ On rare occasions the traditional analysis is abandoned altogether. In President of the Methodist Conference v Preston [2013] UKSC 29 the Supreme Court held that the manner in which a Methodist minister was engaged was incapable of being analysed in terms of contractual formation. Activity 2.5 A wrote to B offering 300 bags of cement at £10 per bag. B wrote in reply that she was very interested but needed to know whether it was Premium Quality cement. The following morning, soon after A read B’s letter, B heard a rumour that the price of cement was about to rise. She immediately sent a fax to A stating, ‘Accept your price of £10 for Premium Quality’. Assuming that the cement actually is Premium Quality, is there a contract? If so, does the price include delivery? Explain your reasoning. Activity 2.6 What is the position under the ‘last shot rule’ if, after the exchange of forms, the seller fails to deliver the goods? 2.4 Communication of the acceptance Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 3 ‘Offer and acceptance’ – Section 3.8 ‘Communication of the acceptance’, and Section 3.10 ‘Prescribed method of acceptance’ to Section 3.14 ‘Termination of the offer’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 2 ‘Agreement’ – Section 4D ‘Communication of the acceptance to the offeror’. The general rule is that acceptance is not effective until it is communicated to the offeror. This is sometimes expressed by saying that the acceptance cannot be made Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance through silence and Felthouse v Bindley is often cited to support this proposition. Such a statement is, however, too broad and the true rule of law is discoverable by reflection upon what is ‘wrong’ with saying that silence cannot amount to acceptance. Most people would agree that is inconsistent with the view of a contract as a voluntarily assumed obligation to allow one party to ‘force’ a contract upon a party that that party does not want at the time of contracting. If a lecturer and author was able to say to his contract class that he will assume that all his audience want to buy a copy of his book unless they say not in the next five seconds it is perhaps obvious that she should not be able to rely upon those five seconds silence as evidence of acceptance of an offer to sell a copy of her book. The so called rule (i.e. that silence cannot constitute acceptance) should extend only as far as the policy that justifies it (i.e. that the law should not allow an offeror to force a contract on an unwilling offeree). So qualified the proper rule becomes: silence will not constitute acceptance when to so hold would involve forcing a contract on an unwilling party. It then follows that silence can constitute acceptance when this does not involve forcing a contract upon an unwilling party. In Rust v Abbey Life [1979] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 334 the Court of Appeal, by way of obiter dicta, approved this more limited statement of the ‘silence as acceptance’ rule. Where the law of contract insists on communication either as here in relation to acceptance or in relation to the revocation of a contractual offer (Section 2.7.1 below) a question can arise as to the timing of communication when it is received by a machine (e.g. a fax or email), maybe outside of usual office hours. By analogy with a case, in Tenax Steamship Co v Owners of the Motor Vessel Brimnes (The Brimnes) [1975] QB 929, concerning the notice of the withdrawal of a ship under a ship charter, it is suggested that communication to any ‘unmanned receptor’ is effective from the time at which it is reasonable to expect that machine to be checked. Therefore, if it is not reasonable to expect a computer to be checked out of usual business hours a communication sent at this time may only be regarded as communicated after the next opening of the office concerned. Activity 2.7 You offer to buy a kilo of oranges from your local shop for 9p. Nothing further is said, nor do you receive any written correspondence. The next day, however, a kilo of oranges arrives at your house from the local shop. Is there a valid acceptance of the contract? Has there been a communication of the acceptance? See Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Company [1877] 2 App Cas 666. Self-assessment questions 1. What was the detriment to the offeree in Felthouse v Bindley? 2. Could an offeror use this case to avoid liability? 2.5 Exceptions to the need for communication of the acceptance Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 3 ‘Offer and acceptance’ – Section 3.12 ‘Exceptions to the rule requiring communication of acceptance’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 2 ‘Agreement’ – Section 4D ‘Communication of the acceptance to the offeror’. As we saw above, the general rule is that for an acceptance to be valid it must be communicated to the offeror. It must be brought to the offeror’s attention. To this general rule there are certain exceptions – situations where the law does not require communication of the acceptance. page 27 page 28 University of London International Programmes 2.5.1 Where the offeror has waived the requirement of communication As we have seen above, in certain circumstances the offeror may waive the necessity for communication. This is what occurred in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co which was a case involving a unilateral offer. 2.5.2 Unilateral offers A unilateral contract is one where one party makes an offer to pay another if that other party performs some act or refrains from some act. The other party need make no promise to do the act or refrain from the act. In these cases, acceptance of the offer occurs through performance and there is no need to communicate acceptance in advance of performance. An example of the offer of a unilateral contract is an offer of a reward for the return of a lost cat. In the case of Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company (1893) it was established that full performance is the acceptance of the offer and there is no need to communicate the attempt to perform. Communication of the acceptance is waived because it would be unreasonable of the offeror to rely on the absence of a communication which would have been superfluous or which no reasonable person would expect to be made. The other principal exception is the postal acceptance rule. 2.5.3 The postal acceptance rule Communication by post gives rise to special practical difficulties. An offer is posted. The offeree receives the offer and posts her acceptance. The letter of acceptance will take several days to arrive. At what point is the acceptance good? If one waits until the offeror receives the letter, how will the offeree know when this is? The offeree has known from the time she posted the letter that she has accepted the offer. There is also the occasional problem of the letter that never arrives at its destination. To overcome these problems, the courts devised an exception to the general requirement of communication (which would have been that the acceptance is only good when the letter arrives). The exception was devised in the cases of Adams v Lindsell [1818] 106 ER 250 and Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Co Ltd v Grant [1879] 4 Ex D 216. These decisions establish the ‘postal acceptance rule’, that is, that acceptance is complete when posted. This puts the risk of delay and loss on the offeror. It is important to understand that the rule is an exception to the general rule requiring communication. The postal acceptance rule will only prevail in certain circumstances. It will prevail where use of the post was reasonably contemplated by the parties or stipulated by the offeror. See Household Fire Insurance v Grant (1879). It may be that the post is the only reasonable form of communication available. See Henthorn v Fraser [1892] 2 Ch 27. The postal acceptance rule will not allow a contract to be concluded by posting the acceptance where the letter is incorrectly addressed by the offeree. The offer may accept the risk of delay occasioned by the post but not the carelessness of the offeree: LJ Korbetis v Transgrain Shipping BV [2005] EWHC 1345. The operation of the postal acceptance rules creates practical difficulties. The greatest problem is that contracts can be formed without the offeror being aware of the contract. For example, an offeror makes an offer. Unbeknown to him, the offeree accepts. The offeror then revokes the offer before receiving the postal acceptance. The offeror contracts with another party over the same matter – and then receives the postal acceptance from the original offeree. The offeror is now in breach of his contract with the original offeree. Partly because of these problems and partly because of technological advances (the post is no longer a such crucial method of communication), courts seem to Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance be confining the scope of the postal acceptance rule. This is a rationale behind the decision in Holwell Securities v Hughes [1974] 1 WLR 155. In this case, the postal acceptance rule did not apply because the offeror did not intend that it would apply. While this case is authority for the proposition that the terms of an offer must be met for acceptance to be valid, it also illustrates the reservations modern courts have over the postal acceptance rule. In an early case involving a telegram, a form of the postal acceptance rule was applied (Bruner v Moore [1903] 1 Ch 305) but in later cases involving telexes, the courts refused to extend the application of the postal acceptance rules. See Entores v Miles Far East Corp [1955] 2 QB 327 and Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl [1982] 2 WLR 264. As modern forms of communication such as fax and email have become almost instantaneous, courts have shown a marked reluctance to extend the postal acceptance rule to these new forms of communication. In JSC Zestafoni Nikoladze Ferroalloy Plant v Romly Holdings [2004] EWHC 245 (Comm) an acceptance by fax was held to be an instantaneous communication. In Thomas v BPE Solicitors [2010] EWHC 306 Blair J said obiter that the postal rule should not apply to contracts concluded through the exchange of emails and this is supported by the Singapore decision of Chwee Kin Keong v Digilandmall. com Pte Ltd [2004] 2 SLR 594. Regulations governing internet trading (i.e. the purchase of goods or services from websites), principally the Electronic Commerce (EC Directive) Regulations (2002) do not identify at what stage acceptance is effected. However, Regulation 11(2) provides that in contracts with a consumer the order and acknowledgment of the order are deemed to be received when the addressee is able to access them. This reference to receipt in the Regulations would appear to indicate that the default rule that acceptance is effective upon receipt, rather than as with the postal rule on sending, should apply to all internet sales. English contract law awaits a definitive case involving an almost instantaneous communication – such as a fax or an email. It is clear that a contract can be formed through such mediums (see, for example, Allianz Insurance Co-Egypt v Aigaion Insurance Co SA [2008] EWCA Civ 1455). Because of the technology involved in both these forms of communication they are not entirely instantaneous. An email, in particular, may take some time to arrive at its destination, depending upon the route it takes to its recipient. As Poole has suggested, there are two possible approaches to the email communication of the acceptance: postal analogy or receipt rule. Activity 2.8 What rules do you think courts should adopt for communication by fax or email? Self-assessment questions 1. What reasons have been given by the courts for the postal acceptance rule? 2. A posts a letter offering to clean B’s house. B posts a letter accepting A’s offer. Later in the day, B’s house burns down and B now no longer needs a house cleaner. B immediately posts a letter to A rejecting A’s offer. Both of B’s letters arrive at the same time. Is there a contract or not? See Countess of Dunmore v Alexander (1830). 3. In what circumstances will the postal acceptance rules not operate? 4. When, if ever, can an offeror waive the need for communication? Summary For a contract to be formed, the acceptance of an offer must be communicated. There are exceptions to this general rule. The most significant of these exceptions is the postal acceptance rule. The postal acceptance rule is, however, something of an anachronism in the modern world and is unlikely to be extended in future cases. Further reading ¢¢ Gardner, S. ‘Trashing with Trollope: a deconstruction of the postal rules’ (1992) 12 page 29 page 30 University of London International Programmes OJLS 170. ¢¢ Poole, J. Textbook on contract law. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) 12th edition [ISBN 9780199687220] Chapter 2, Section 2.4 ‘Acceptance’. ¢¢ Mik, E.K. ‘The effectiveness of acceptances communicated by electronic means, or - does the postal rule apply to email?’ (2009) 26 JCL 68. ¢¢ Nolan, D. ‘Offer and acceptance in the electronic age’ in Burrow and Peel (eds) Contract formation and parties. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010) [ISBN 9780199583706]. 2.6 Method of acceptance Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 3 ‘Offer and acceptance’ – Section 3.10 ‘Prescribed method of acceptance’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 2 ‘Agreement’ – Section 4B ‘Offeror prescribes the method of acceptance’. Sometimes an offeror may stipulate that acceptance is to be made using a specific method. See Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments [1970] 1 WLR 241. In other cases the required method for communicating acceptance may also be inferred from the making of the offer. See Quenerduaine v Cole [1883] 32 WR 185. The problem that arises is this: if the offeree uses another method of acceptance, does this acceptance create a contract? The answer is that if the other method used is no less advantageous to the offeror, the acceptance is good and a contract is formed. This is the result unless the offeror stipulates a certain method of acceptance and further stipulates that only this method of acceptance is good. See Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments (1970). Self-assessment questions 1. Where a method of acceptance has been prescribed by the offeror: a. May the offeree choose to use another (equally effective) method of communicating his acceptance? b. What does equally effective mean? c. Whose interest should prevail? 2. Can an offer made by fax be accepted by letter? Summary If an offeror intends that a certain method of acceptance is to be used, he must stipulate this method and that only an acceptance using this method is to be used. If he only stipulates a method, an offeree can use another method provided that the other method is no less advantageous than the method stipulated. 2.7 The end of an unaccepted offer Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 3 ‘Offer and acceptance’ – Section 3.14 ‘Termination of the offer’. Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 2 ‘Agreement’ – Section 5 ‘Revocation of an offer’. Offers do not exist indefinitely, open for an indeterminate time awaiting acceptance. Indeed, some offers may never be accepted. What we will consider at the conclusion of this chapter is what happens to an offer before it has been accepted. There is no legal commitment until a contract has been concluded by the acceptance of an offer. 2.7.1 Change of mind Because there is no legal commitment until a contract has been formed, either party may change their mind and withdraw from negotiations any time before there is acceptance (Payne v Cave [1789] 100 ER 502). In situations where an offeror has stipulated that the offer will be open for a certain time period, he or she can nevertheless withdraw the offer within this time period. This will not be the case, however, where the offeror is obliged (by a separate binding collateral contract) to keep the offer open for a specified period of time: Routledge v Grant [1828] 172 ER 415. If a time has been set by which to accept then the offer will automatically lapse at the end of that period. For the revocation of an offer to be effective, there must be actual communication of the revocation. See Byrne v van Tienhoven [1880] 5 CPD 344. It is not necessary for revocation to be communicated by the offeror. Communication to the offeree through a reliable source is sufficient. See Dickinson v Dodds [1876] 2 Ch D 463. Unilateral contracts pose particular problems here. As the act stipulated as acceptance of a unilateral offer may take some time to complete, the situation may arise where the offeror tries to revoke the unilateral offer after the offeree has begun, but before he has completed, performance of the stipulated act. Intuitively it might seem unjust if revocation was allowed in these circumstances and in most cases it is not (see Errington v Errington [1952] 1 KB 290 and Soulsbury v Soulsbury [2007] EWCA Civ 969). However, the way in which such revocation is usually prevented means that revocation is not always impossible. In Luxor (Eastbourne) Ltd v Cooper [1941] AC 108 the House of Lords explained that the revocation of a unilateral offer after the offeree has begun performance of the act stipulated would not be possible in most cases because a term would be implied into the contract that the offeree would not seek to revoke his offer (or otherwise prevent the completion of performance) once that performance had begun (see also Daulia v Four Millbank Nominees [1978] Ch 231). Such a term will be implied where it is necessary to make the agreement commercially effective (‘to give it business efficacy’). It follows that where it is not necessary to imply any such term, as Luxor – the offeror – is free to revoke the offer after performance has begun. In Luxor the House of Lords said that it would not be appropriate to imply such a term where a very large consideration was being offered for a small amount of work. The Court of Appeal in Schweppe v Harper [2008] EWCA Civ 442 emphasised that cases such as Luxor where the offeror is able to revoke after performance has begun will be rare. Activity 2.9 Your neighbour offers to sell you her car for £10,000. She tells you to ‘think about it and let me know by Monday’. On Saturday, she puts a note under your door to say ‘forget it – I want to keep my car’. Can she do this? Explain. By what process must the offeror of a unilateral contract revoke his offer? The problem of an appropriate process exists when the offer is made to the world. In this situation, what must the offeror do to alert ‘the world’? English law provides no answer to this question, but it is thought that the principle of Shuey v USA [1875] 92 US 73 would also apply in the UK (i.e. that revocation may be effected by giving the same prominence to the revocation as was given to the original offer). If this is done then revocation, contrary to the usual rule, may be effective even if it does not actually come to the attention of the offeree. If the offeree rejects an offer, it is at an end. A counter offer (i.e. an offer substantially at variance with an earlier offer) is simultaneously a rejection of the original offer and page 31 page 32 University of London International Programmes also a new offer (see Section 2.3 above). Activity 2.10 Analyse all the communications in Hyde v Wrench (1840) and state whether they are: an invitation to treat, a contractual offer, a counter offer, a rejection or an acceptance. Different problems arise when it is the offeree who changes his or her mind. For example, if after posting a letter of acceptance, the offeree informs the offeror by telephone, before the letter arrives, that they reject the offer, should the act of posting an acceptance prevail over the information actually conveyed to the offeror? In the absence of English cases the books refer to a number of cases from other jurisdictions – see Dunmore v Alexander [1830] 9 S 190 (Scotland) and Wenkheim v Arndt [1873] 1 JR 73 (New Zealand) – but when citing them, it is important to emphasise that they are not binding, and indeed have very little persuasive authority. The question must therefore be answered primarily as a matter of principle. Treitel suggests that ‘the issue is whether the offeror would be unjustly prejudiced by allowing the offeree to rely on the subsequent revocation’. 2.7.2 If a condition in the offer is not fulfilled, the offer terminates Where the offer is made subject to a condition which is not fulfilled, the offer terminates. The condition may be implied. See Financings Ltd v Stimson (1962). In this case, the offeror purported to accept an offer to purchase a car after the car had been badly damaged. 2.7.3 Death: if the offeror dies, the offer may lapse This is a point on which the cases divide. On the one hand, Bradbury v Morgan (1862) 158 ER 877 (Ex) held that the deceased offeror’s estate was liable on the offer of a guarantee after the death of the offeror. However, obiter dicta in Dickinson v Dodds (1876) state that death of either party terminated the offer because there could be no agreement. The best view is probably that a party cannot accept an offer once notified of the death of the offeror but that in certain circumstances the offer could be accepted in ignorance of death. The death of an offeree probably terminates the offer in that the offeree’s personal representatives could not purport to accept the offer. 2.7.4 Lapse of an offer The offeror may set a time limit for acceptance; once this time has passed the offer lapses. In many cases, the offeror can revoke the offer before the time period lapses provided that the offer has not been accepted. See Offord v Davies (1862). In cases in which no time period is stipulated for the offer, an offeree cannot make an offeror wait forever. The offeror is entitled to assume that acceptance will be made within a reasonable time period or not at all. What a reasonable time period is will depend upon the circumstances of the case. See Ramsgate Victoria Hotel v Montefiore [1866] LR 1 Ex 109. Self-assessment questions 1. Why can the offeror break his or her promise to keep the offer open for a stated time? 2. In a unilateral contract which is accepted by performance, when has the offeree started to perform the act (so as to prevent revocation by the offeror)? Does the offeror need to know of the performance? 3. How can the offeror inform all potential claimants that the offer of a reward has Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance been cancelled? 4. Will there be a contract if the offeree posts a letter rejecting the offer but then informs the offeror by telephone, before the letter arrives, that he accepts the offer? 5. What is the purpose of implying that the offer is subject to a condition? Summary Until an offer is accepted, there is no legal commitment upon either party. Up until acceptance, either party may change their mind subject to the next sentence. An offeror may not revoke a unilateral offer after performance has begun whenever the offeror has undertaken, perhaps impliedly, not to do so. An offeree may reject an offer prior to acceptance and may do so by making a counter offer. uu An unaccepted offer expires either: uu at the end of any time period stipulated, or uu within a reasonable time period where no time period is stipulated. uu An offer will lapse where it is made on an unfulfilled condition. uu An offer may lapse when the offeror dies. Further reading ¢¢ Halson, Chapter 3 ‘Agreement: offer and acceptance’. Examination advice The detailed rules of offer and acceptance provide a ready source of problems and difficulties on which examiners can draw. Here are some examples. uu Is a particular statement an offer or an invitation to treat? uu Is there a counter-offer or is it merely an enquiry? uu When does a posted acceptance fall outside the postal rule? uu Was the offeror or offeree free to have second thoughts? uu When is a telephone call recorded on an answering machine actually received? uu When is an email received? There are also several everyday transactions where the precise contractual analysis is not immediately apparent – the motorist filling up with petrol (gas), the passenger riding on a bus, the tourist buying a ticket for the Underground (subway) from a machine and so on. The fact that some of these problems are not covered by authority does not make them any less attractive to examiners – indeed, the opposite might well be the case. The key to most problems of offer and acceptance is the idea that the law should give effect to actual communication wherever possible. Sample examination questions Question 1 Alice wrote to Bill offering to sell him a block of shares in Utopia Ltd. In her letter, which arrived on Tuesday, Alice asked Bill to ‘let me know by next Saturday’. On Thursday Bill posted a reply accepting the offer. At 6pm on Friday he changed his mind and telephoned Alice. Alice was not there but her telephone answering machine recorded Bill’s message stating that he wished to withdraw his acceptance. On Monday Alice opened Bill’s letter, which arrived that morning, and then played back the message on the machine. page 33 page 34 University of London International Programmes Advise Alice. Question 2 Cyril, a stamp dealer, had a rare Peruvian 5 cent blue for sale. He wrote to Davina, a collector who specialises in Peruvian stamps, asking whether she would be interested in purchasing it. Davina wrote in reply, ‘I am willing to pay £500 for the “blue”; I will consider it mine at that price unless I hear to the contrary from you and will collect it from your shop on Friday next week.’ Advise Davina as to the legal position: a. if Cyril disregarded Davina’s letter and sold the stamp to Eric for £600 b. if Cyril put the stamp on one side in an envelope marked ‘Sold to Davina’ but Davina decided that she no longer wished to buy it. Question 3 a. On 1 January A writes to B saying, ‘I am considering selling my horse, Philocretes, and I wonder whether you would like to buy him. I would expect to receive about £500 for him’. On 2 January B writes back, ‘I accept your offer and will send you the money in a few days’. On 3 January A writes to B: ‘Don’t be ridiculous, I wasn’t offering the horse for sale, and anyway I want £750 for him. To avoid misunderstanding, do not write back unless you do not want the horse at this price’. B was so annoyed on reading the first sentence that he tore up the letter without reading further and did not reply. Three weeks later A came round and demanded £750, offering to deliver the horse. Advise B. b. Would your answer be any different if upon reading A’s second letter B decided to purchase the horse for £750 and A now refuses to deliver it? Advice on answering the questions It is important to break the question down into its constituent issues. You are considering each of these issues with a view to determining whether or not a contract has been formed. Bill will argue that he is not obliged to purchase the shares because no contract has been formed. Communications must be considered chronologically because the proper legal analysis of a later communication will often depend upon that of a prior one. A communication from A to B cannot be an acceptance unless there has been a prior communication from B to A that constitutes an offer; a communication from A to B cannot be a counter offer unless B has previously made an offer to A. Sometimes it may not be possible to come to a firm conclusion as to the proper analysis of a communication, in which case two alternatives may need to be considered, of the type: if A’s letter to B is an offer then B’s reply may be an acceptance, but if A’s letter to B is only an invitation to treat (negotiate) then B’s reply may be a contractual offer, etc. Question 1 The issues in this problem are: a. What is the effect of Alice writing to Bill to offer to sell him shares? b. What is the effect of Alice’s stipulation as to the time the offer is open? c. What is the effect of Bill’s posting a reply? d. What is the effect of Bill’s change of mind? Is there effective communication when a message is left on an answering machine? e. Which of Bill’s two communications is determinative? When the issues are listed in this form it is apparent that the biggest issue is whether or not a contract has been formed. This is dependent upon whether Alice’s offer has been accepted. This, in turn, depends upon whether Bill has communicated his acceptance or his rejection. We will examine these issues in turn. Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance a. Alice’s letter appears to be an offer within the criteria of Gibson v Manchester City Council and Storer v Manchester City Council. You should outline these criteria and apply them to the facts – sometimes the designation of an ‘offer’ in a problem question or in everyday life turns out not to be an offer in the legal sense. b. Alice’s stipulation that the offer is open for one week is not binding (apply the criteria in Offord v Davies) unless there is a separate binding contract to hold the offer open. There does not appear to be such a separate binding agreement. c. Because Bill posts his letter of acceptance, we need to consider whether or not the postal acceptance rules apply. Consider the criteria in Household Fire Insurance v Grant. Does the case apply here? In the circumstances, it probably does. Alice has initiated communications by post and thus probably contemplates that Bill will respond by post. In these circumstances, the acceptance is good when Bill posts the letter – it is at this point that a contract is formed. It does not matter that the letter does not arrive until Monday (at which point the offer will have expired, given Alice’s stipulation as to the time period). A possible counter argument to this is that Alice asked Bill to let her know by Saturday – and this ‘let me know’ means that there must be actual knowledge of his acceptance – that it must really be communicated. This necessity for actual communication means that Bill’s acceptance is not good until Monday when Alice actually opens the letter. To apply this counter argument, one needs to consider the criteria set out in Holwell Securities v Hughes. One might also note that since that decision, courts are reluctant to extend the ambit of the postal acceptance rule. d. Bill changes his mind. Here there is no authority as to the effect of his change of mind. In addition, given the two possible positions in point (c) above, two possible outcomes exist. If the postal acceptance rules apply, then a contract has been formed and Bill’s later change of mind cannot upset this arrangement. However, this seems a somewhat absurd result since Alice learns almost simultaneously of the acceptance and the rejection. Bill has attempted to reject the offer by a quicker form of communication than the post. In these circumstances, you could apply the reasoning of Dunmore v Alexander and state that no contract has been formed between the parties. In addition, given the reservations of the court in Holwell Securities v Hughes, it seems improbable that a court would rely upon the postal acceptance rule, an unpopular exception to the necessity for communication, to produce an absurd result. The second possible outcome here is that the postal acceptance rules never applied and no contract could be formed until Alice opened the letter. Since she received the rejection at almost the same time, she is no worse off (see reasoning above) by not having a contract. You might also wish to consider the application of the rules for instantaneous communications in Entores v Miles Far East Corp and Brinkibon v Stahag Stahl [1983] 2 AC 34. Should the communication made by telephone be deemed to have been the first received? If so, there is no contract. e. This is really the answer to the question. For the reasons stated above, the rejection should be determinative. Accordingly, no contract arises in this situation and Bill is not obliged to buy the shares in Utopia Ltd. Question 2 Note at the outset that in two-part questions such as this you must answer both parts (unless clearly instructed that candidates are to answer either a or b). Again, your approach should be to break down the question into its constituent parts: uu The effect of Cyril’s letter – is it an offer or an invitation to treat? uu The effect of Davina’s letter – is it an acceptance? Does the postal acceptance rule apply? Is Davina’s letter a statement of intention? uu Is Davina’s letter an offer? Can she waive the necessity for the communication of the acceptance? page 35 page 36 University of London International Programmes By considering these issues, you can determine whether a contract has been formed or not. With respect to part (a), if a contract has been formed, then Cyril is in breach of this contract when he sells the stamp to Eric. You need to consider whether Cyril has made an offer – has he exhibited a willingness to commit on certain terms within Storer v Manchester City Council (1974)? Or is his communication an invitation to treat or a step in the negotiation of a contract? If his letter is an offer, it seems reasonable that he expects an acceptance by post and the postal acceptance rules will apply: Household Fire Insurance v Grant (1879). On balance, it seems unlikely that his letter is an offer – it is phrased in terms that seek to elicit information and not to be binding upon further correspondence from Davina. Davina may have made an offer and waived the necessity for further communication – see Felthouse v Bindley (1862). It is, however, possible that either Davina never made an offer to buy the stamp (she was merely giving an indication of her top price) or that Cyril never accepted the offer. In these circumstances, no contract has been formed with Davina and Cyril is free to sell the stamp. With regard to part (b), if Davina has (and can, given the law in this area – see Felthouse v Bindley (1862) and Rust v Abbey Life (1979)) made an offer, then Cyril has (if possible) accepted the offer when he takes the step of setting aside the stamp. In these circumstances, a contract has been formed and Davina is obliged to buy the stamp. There are, however, significant weaknesses in reaching this conclusion – primarily that she seems to be indicating the top price she would pay for the stamp and that if a broad interpretation is taken of Felthouse v Bindley (1862) (but this would be contrary to the obiter dicta in Rust v Abbey Life) she cannot waive the necessity for communication of the acceptance. Question 3 A-B Jan 1 Is this an offer or an invitation to treat? You should define each and consider Gibson v Manchester City Council and Storer v Manchester City Council. On the authority of Gibson words such as ‘considering’, ’wonder’, ’expect’ are likely to be considered too equivocal to support the existence of an offer so this communication will be an invitation to treat. B-A Jan 2 This is phrased as acceptance but the law looks to the substance not the form of communications. For example, in Hyde v Wrench a purported acceptance was held to amount to an offer only and in Pickford v Celestica [2003] EWCA Civ 1741 a purported acceptance was held to be a counter offer. Here the purported acceptance must be an offer to buy. A-B Jan 3 This is a counter offer as it is substantially different to the previous offer, see Hyde v Wrench; it cannot be a ‘mere enquiry’ as in Stevenson v McLean. Was this offer accepted? B’s silence cannot constitute acceptance: Felthouse v Bindley. If B’s silence amounted to acceptance then this would involve forcing a contract on an unwilling party. This is the wrong which the rule that silence should not amount to acceptance aims to avoid. What if? In this variation the offeree B wants to waive the protection usually offered by the Felthouse v Bindley rule, so here B’s silence could constitute acceptance on the authority of Rust v Abbey Life. Quick quiz Question 1 Which of the following statements provides the most appropriate definition of an offer in a contract? a. Where one party (A) offers the other party (B) the opportunity to enter into negotiations for the purchase of property. b. Where one party (A) puts a proposition to another party (B) which is coupled by Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance an indication that they (A) are willing to be held to that proposition. c. Where one party (A) sees an advert in a newspaper by (B) offering for sale a wild live bird. d. Where one party (A) thinks the other party (B) will accept a lower price for property that he is preparing to sell. e. Don’t know. Question 2 How did Parker LJ in the case of Fisher v Bell (1961) explain the status of an article as part of a display in a shop window? a. Contract law has never been clearer as to the fact that any display in a shop window must constitute an offer. To decide otherwise would place shoppers in peril as it would entice them into shops to purchase goods, only to discover the goods were on sale for a different, probably higher, price. b. In the case of an ordinary shop, although goods are displayed and it is intended that customers should go and choose what they want, the contract is not completed until, the customer having indicated the articles which he needs, the shopkeeper, or someone on his behalf, accepts that offer. c. It is perfectly clear that according to the ordinary law of contract the display of an article with a price on it in a shop window is merely an invitation to treat. It is in no sense an offer for sale, the acceptance of which constitutes a contract. d. The display of goods constitute an offer which could not be accepted before the goods reach the cashier. Until then the customer is free to return an article to the shelf even though they have put it in the basket. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following statements explains how the law of contract treats auction sales? a. The advertising of the auction sale is the point at which the contract begins. If the claimant presents themselves for auction to discover there is no longer any property for auction they can claim damages from the auctioneer for loss of expectation. b. Once the auction begins the auctioneer is bound to sell to the highest bidder even if the reserve price is not met. c. Once the auction has begun the highest bidder has the right to enforce the contract even if they acquire property for £200 which is actually worth £14,000. d. Once the auctioneer’s hammer has fallen then the highest bidder has the first opportunity to enter into negotiations with the auctioneer as to what price they should pay for the property up for sale. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Which of the following statements was specifically made by Bowen LJ in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co (1893) and attempts to defeat claims in that case that the advertisement was an invitation to treat rather than an offer? a. Any act of the plaintiff from which the defendant gains any benefit or advantage, or any work, detriment, or inconvenience suffered by the plaintiff, provided such act is performed or such inconvenience sustained by the plaintiff, with the consent, express or implied of the defendant. page 37 page 38 University of London International Programmes b. In the advertisement cases ... there never was any problem with thinking that the advertisement was a promise to pay the money to the person who first gave information. The difficulty suggested was that it was a contract with all the world. But that of course was soon overruled. c. It follows from the nature of the thing that the performance of the condition is sufficient to acceptance without the notification of it and a person who makes an offer in an advertisement of that kind makes an offer which must be read by the light of that common sense reflection. d. I am of the opinion that an offer does not bind the person who makes it until it has been accepted, and its acceptance has been communicated to him or his agent. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Which of the following statements about unilateral contracts are true? a. A unilateral offer can never be revoked after it has been made. b. Revocation of a unilateral offer is only effective if the offeree receives actual notice of revocation. c. Revocation of a unilateral offer is effective when the offeree receives actual notice of revocation and also if he does not but the offeror attempts to communicate the revocation by the same means used to publicise the original offer. d. Revocation of a unilateral offer is effective when the offeree receives actual notice of revocation and also if he does not but the offeror attempts to communicate the revocation by the same, or more effective, means used to publicise the original offer. e. A unilateral offer can never be revoked once the offeree has begun performance of the stipulated act. f. A unilateral offer cannot be revoked once the offeree has begun performance of the stipulated act whenever a term or collateral promise to that effect can be implied. Question 6 Which of the following statements is made by Denning LJ in Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corporation [1955] 2 QB 327 to explain the requirement, or not, of communication of an acceptance to an offer made in a contract? a. He who shouts loudest, shouts longest and if someone shouts their acceptance and the Concorde aeroplane flies over and their acceptance is muffled by the breaking of the sound barrier then that acceptance has still been delivered. b. To err is human, to forgive divine and just because the other party has faithfully conveyed the acceptance to the offer, if that acceptance is not communicated effectively, a contract is not formed. c. It appears to me that both legal principles, and practical convenience require that a person who has accepted an offer not known to him to have been revoked, shall be in a position safely to act upon the footing that the offer and acceptance constitute a contract binding on both parties. Contract law 2 Agreement: offer and acceptance d. Suppose, for instance, that I shout an offer to a man across a river or courtyard but I do not hear his reply because it is drowned by an aircraft flying overhead. There is no contract at that moment. If he wishes to make a contract he must wait till the aircraft is gone and then shout back his acceptance so that I can hear what he says. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the subject module or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is a contractual offer? 2. What is the difference between a unilateral and a bilateral offer? 3. What is the difference between an offer and other communications? 4. How do you know when an offer has been communicated? 5. What is (and is not) a valid acceptance? 6. What is the necessity of communicating the acceptance? 7. What are the exceptions to the necessity of communicating the acceptance? 8. What occurs when the offeror stipulates a certain method of acceptance? 9. What happens to an offer which is not accepted? 10. When does an offer expire? page 39 page 40 Notes University of London International Programmes Part I Requirements for the making of a contract 3 Consideration Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42 3.1 Consideration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43 3.2 Promissory estoppel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56 page 42 University of London International Programmes Introduction The concept of ‘consideration’ is the principal way in which English courts decide whether an agreement that has resulted from the exchange of offer and acceptance (as explained in Chapter 2) should be legally enforceable. It is only where there is an element of mutuality about the exchange, with something being given by each side, that a promise to perform will be enforced. A promise to make a gift will not generally be treated as legally binding. It is the presence of consideration which makes this promise binding as a contract. It is possible to see consideration as an important indication that the parties intended their agreement to be legally binding as a contract. Although there is a separate requirement of an intention to create legal relations (discussed in Chapter 4), it is clear that historically this requirement was also fulfilled by the requirement of consideration. While the doctrine of consideration is crucial to English contract law, it has been applied with some flexibility in recent years. At common law a promise is only enforceable if supported by consideration. A B A promises to paint B’s garden fence. The promise to do this is consideration moving from A to B. For this to form the basis of a binding agreement there must be a promise from B, perhaps to pay A for the work, for this to be a binding agreement. There is then consideration moving from B to A. In some circumstances, English courts will find that a promise given without consideration is legally binding and this chapter concludes with an examination of these instances. These instances are decided upon on the basis of the doctrine of ‘promissory estoppel’ and in this area the courts are concerned to protect the reasonable reliance of the party who has relied upon the promise. These instances arise where there is a variation of existing legal obligations. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the doctrine and requirement of consideration to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The basic definition of consideration. uu The significance of consideration to the English law of contract. uu The acts which the courts have recognised as sufficient to constitute good consideration. uu Situations where the performance of, or promise to perform, an existing obligation amount to consideration for a fresh promise. uu The definition of ‘past consideration’ and its exceptions. uu The role of consideration in the modification of existing contracts. uu The essential elements of the doctrine of ‘promissory estoppel’. uu How the doctrine of promissory estoppel lead to the enforcement of some promises which are not supported by consideration. Contract law 3 Consideration 3.1 Consideration Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 5 ‘Consideration and form’ – Section 5.1 ‘Requirements of form’, Section 5.20 ‘Reliance upon non-bargain promises’, Section 5.21 ‘The role of consideration’ and Section 5.29 ‘Conclusion: the future of consideration’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 4 ‘Enforceability of promises: consideration and promissory estoppel’ – Section 1A ‘What is consideration?’. Consideration has been called the ‘badge of enforceability’ in agreements. This is particularly important where the agreement involves a promise to act in a particular way in the future. In exchanges where there is an immediate, simultaneous transfer of, for example, goods for money (as in most everyday shop purchases), the doctrine of consideration applies in theory but rarely causes any practical problems. This immediate exchange is sometimes referred to as executed consideration. However, if somebody says, for example, ‘I will deliver these goods next Thursday’ or ‘I will pay you £1,000 on 1 January’ (executory consideration) it becomes important to decide whether that promise is ‘supported by consideration’ (that is, something has been given or promised in exchange). A promise to make a gift at some time in the future will only be enforceable in English law in absence of consideration if put into a special form, that is, a ‘deed’. (For the requirements of a valid deed, see s.1 of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989.) Where a promise for the future is not contained in a deed, then consideration becomes the normal requirement of enforceability. 3.1.1 The definition of consideration Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 5 ‘Consideration and form’ – Section 5.2 ‘Consideration defined’ to Section 5.6 ‘Consideration must be sufficient but it need not be adequate’ and Section 5.19 ‘Consideration must move from the promisee’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 4 ‘Enforceability of promises: consideration and promissory estoppel’ – Section 1A ‘What is consideration?’ and Section 1B ‘Consideration distinguished from a condition imposed on recipients of gifts’. Look at the traditional definition of consideration as set out in Currie v Misa (1875): a valuable consideration, in the sense of the law, may consist either in some right, interest, profit or benefit accruing to the one party, or some forbearance, detriment, loss of responsibility given, suffered or undertaken by the other. You will see that it is based around the concept of a ‘benefit’ to the person making the promise (the promisor), or a ‘detriment’ to the person to whom the promise is made (the promisee). Either is sufficient to make the promise enforceable, though in many cases both will be present. This is generally quite straightforward where one side performs its part of the agreement. This performance can be looked at as detriment to the party performing and a benefit to the other party, thus providing the consideration for the other party’s promise. More difficulty arises where the agreement is wholly ‘executory’ (that is, it is made by an exchange of promises, and neither party has yet performed). It is clear that English law treats the making of a promise (as distinct from its performance) as capable of being consideration – see the statement of Lord Dunedin in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v Selfridge & Co Ltd (1915) p.855. Thus, in a wholly executory (i.e. unperformed) contract, the making of the promise by each side is consideration for the promise made by the other side (so rendering both promises enforceable). This leads to a circular argument. A promise cannot be a detriment to the person making it (or a benefit to the person to whom it is made) unless it is enforceable. But it will only be enforceable if it constitutes such a detriment (or benefit). For this reason it is perhaps better to regard the doctrine of consideration as simply requiring ‘mutuality’ in the agreement (that is, something being offered by each side to it, the exchange principle) rather than trying to analyse it strictly in terms of ‘benefits’ and ‘detriments’. page 43 page 44 University of London International Programmes Another principle of consideration is that to be able to enforce a promise it must be proven that the promisee has provided consideration for that promise (Tweddle v Atkinson). This principle is closely linked to the doctrine of privity, as Tweddle v Atkinson is held to prove that consideration must move from the promisee but not necessarily to the promisor and that only those party to the contract can enforce the obligations of the contract. This is explored more fully in Chapter 11 but it is important to see the connection between the two principles. Activity 3.1 Suppose that A arranges for B to clean A’s windows, and promises to pay B £30 for this work. B does the work. How does the analysis of ‘benefit’ and ‘detriment’ apply in identifying the consideration supplied by B for A’s promise of payment? Activity 3.2 As in 3.1, but this time A pays the £30 immediately, and B promises to clean the windows next Tuesday. What is the consideration for B’s promise? Activity 3.3 As in 3.1, but A and B arrange for the windows to be cleaned next Tuesday, with A paying £30 on completion of the work. Suppose B does not turn up on Tuesday. Is B in breach of contract? 3.1.2 Consideration must be ‘sufficient’ but need not be ‘adequate’ Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 5 ‘Consideration and form’ – Section 5.6 ‘Consideration must be sufficient but it need not be adequate’ to Section 5.9 ‘Compromise and forbearance to sue’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 4 ‘Enforceability of promises: consideration and promissory estoppel’ – Section 1C ‘Consideration must be sufficient but need not be adequate’. These words can seem interchangeable at first glance but they actually mean something very different in this context. The requirement that consideration must be ‘sufficient’ means that what is being put forward must be something which the courts will recognise, or have recognised as legally capable of constituting consideration. The fact that it need not be ‘adequate’ indicates that the courts are not generally interested in whether there is a match in value between what is being offered by each party, so no need for proportionality. Thus in Thomas v Thomas (1842) the promise to pay £1 per annum rent was clearly ‘sufficient’ to support the promise of a right to live in a house: the payment of, or promise to pay, money is always going to be treated as being within the category of valid consideration. On the other hand, the fact that £1 per annum was not a commercial rent was irrelevant, because the courts do not concern themselves with issues of ‘adequacy’. Consider the case of Chappell v Nestlé (1960). You will see that Lord Somervell justifies the courts’ approach to the issue of ‘adequacy’ by reference to ‘freedom of contract’: ‘A contracting party can stipulate for what consideration he chooses’. The courts will not interfere just because it appears that a person has made a bad bargain. The person may have other, undisclosed, reasons for accepting consideration that appears inadequate. In the case of Chappell v Nestlé the reasoning was presumably that the requirement to send in the worthless wrappers would encourage more people to buy the company’s chocolate. It is sometimes suggested that consideration will not be sufficient if it has no economic value. This explains White v Bluett (1853) where a son’s promise to stop complaining to his father about the distribution of the father’s property was held to be incapable of amounting to consideration. But it is difficult to see that the wrappers in Chappell v Nestlé had any economic value either. Contract law 3 Consideration Activity 3.4 Read the case of Ward v Byham (1956). Identify the consideration supplied by the mother. Does the consideration meet the requirement of having economic value? Activity 3.5 Read the case of Edmonds v Lawson (2000). What consideration was supplied by the pupil barrister? Does the consideration meet the requirement of having economic value? 3.1.3 Existing obligations as good consideration Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 5 ‘Consideration and form’ – Section 5.10 ‘Performance of a duty imposed by law’ to Section 5.18 ‘Past consideration’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 4 ‘Enforceability of promises: consideration and promissory estoppel’ – Section 1C ‘Consideration must be sufficient but need not be adequate’ and Section 1D ‘Part payment of a debt’. ¢¢ Chen-Wishart, M. ‘Consideration: practical benefit and the Emperor’s new clothes’, in your study pack or Chen-Wishart, M. ‘A bird in the hand: consideration and contract modifications’, in your study pack. ¢¢ Luther, P. ‘Campbell, Espinasse and the sailors: text and context in the common law’ (1999) 19 Legal Studies 526. There are three aspects to this topic, dealing with three different types of existing obligation which may be argued to constitute ‘consideration’. 1. Obligations which arise under the law, independently of any contract. 2. Obligations which are owed under a contract with a third party. 3. Obligations to perform an existing obligation under a contract to the same contracting party. The third situation is, essentially, concerned with the variation of existing contractual obligations as between the parties and the extent to which such variations can become binding. These three situations will be considered in turn. 1. Obligations which arise under the law An example of the first type of existing obligation would be where a public official (such as a firefighter or a police officer) agrees to carry out one or more of their duties in return for a promise of payment from a member of the public. In that situation the promise of payment will not generally be enforceable. This is either because there is no consideration for the promise (the public official is only carrying out an existing duty) or, more probably, because public policy generally suggests that the law should not encourage the opportunities for extortion that enforcing such a promise would create. Where, however, the official does more than is required by the existing obligation, then the promise of payment will be enforceable, as shown by Glasbrook Bros Ltd v Glamorgan CC (1925). This position at common law is now, in relation to police services, enshrined in statute. Section 25 of the Police Act 1996 distinguishes between performing their duty of doing what is necessary to prevent crime for which they cannot charge and doing something else at the request of an individual for which they can charge. This provision and its identical predecessor has been considered in a number of cases concerning undertakings by football clubs to pay for police services on match days. In the latest case of Leeds United FC v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire [2013] EWCA Civ 113, the Court of Appeal held that the police were under a duty to prevent crime, maintain law and order and protect page 45 page 46 University of London International Programmes property which extended to providing protection in the vicinity of land owned by the club. Consequently, the provision of police services in areas adjacent to the football ground which the club neither owned or controlled could not be charged for. Activity 3.6 In Collins v Godefroy (1831), why was the promise of payment unenforceable? Activity 3.7 In Ward v Byham (1956), why was the father’s promise enforceable? 2. Obligations which are owed under a contract with a third party In the second type of situation, which regards the performance of, or promise to perform, an existing obligation owed under a contract with a third party, the position is much more straightforward. The courts have consistently taken the view that this can provide good consideration for fresh promise. Thus it has been applied to the fulfilling of a promise to marry (Shadwell v Shadwell (1860) – such a promise at the time being legally binding) and to the unloading of goods by a firm of stevedores, despite the fact that the firm was already obliged to carry out this work under a contract with a third party (The Eurymedon (1975)). The Privy Council confirmed, in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long (1980), that the promise to perform an existing obligation owed to a third party can constitute good consideration. A B A promises B to teach for one hour at the University. B promises to pay £X for that teaching. A C C, one of the university students, promises to pay £Y for the hour of teaching. A agrees to do the teaching. In this situation if A does the promised hour of teaching they can claim both £X from B and £Y from C. Although A has done no more than contractually obliged to do under the contract with B, this is held to be valid consideration for the promise by C to pay £Y. The consideration from A can be seen as the ‘detriment’ of being open to liability for breach of contract to both B and C should A fail to perform. 3. Obligations to perform an existing obligation under a contract to the same contracting party This is essentially where there is a variation to an existing contractual obligation between contracting parties – this is the most difficult to employ as consideration. This results from the fact that a principle which was clear, though impractical in some circumstances, has now been modified and the extent of this modification is unclear. Performance of an existing obligation The general rule in relation to the variation of existing obligation can be seen in the case of Stilk v Myrick (1809) (which you should read in full). Contract law 3 Consideration Stilk v Myrick was long accepted as establishing the principle that the performance of an existing contractual obligation could never be good consideration for a fresh promise, to pay more in this case, from the person to whom the obligation was owed. The sailors’ contract obliged them to sail the ship back home. Thus in bringing the ship back to London they were doing nothing more than they were already obliged to do under their original contract. This could not be good consideration for a promise of additional wages. Only if the sailors had done Figure 3.1 Stilk was contracted to something over and beyond their existing work on a ship owned by Myrick obligation could the variation (the promise of extra payment) become enforceable, their extra work constituting fresh consideration for the promise to pay extra (Hartley v Ponsonby). Activity 3.8 What other explanation can there be for the decision in Stilk v Myrick? Activity 3.9 How can Stilk v Myrick be distinguished from the factually similar case of Hartley v Ponsonby (1857), where the recovery of additional payments was allowed? However, this rule has now become less certain since the important decision of the Court of Appeal in Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd (1991). This case raised the question of whether Stilk v Myrick could still be said to be good law. The plaintiff carpenters, in completing the work on the flats, appeared to be doing no more than they were already obliged to do under their contract with the defendants. How could this constitute consideration for the defendants’ promise of additional payment? The application of Stilk v Myrick would point to the promise being unenforceable. Yet the Court of Appeal held that the plaintiffs should be able to recover the promised extra payments for the flats which they had completed. The Court came to this conclusion by giving consideration a wider meaning than had previously been thought appropriate. In particular, Glidewell LJ pointed to the ‘practical benefits’ that would be likely to accrue to the defendants from their promise of the additional money. They would be: uu ensuring that the plaintiffs continued work and did not leave the contract uncompleted uu avoiding a penalty clause which the defendants would have had to pay under their contract with the owners of the block of flats uu avoiding the trouble and expense of finding other carpenters to complete the work. The problem is that very similar benefits to these could be said to have accrued to the captain of the ship in Stilk v Myrick. The main point of distinction between the cases then becomes the fact that no pressure was put on the defendants in Williams v Roffey to make the offer of additional payment. In other words, the alternative explanation for the decision in Stilk v Myrick, as outlined in the feedback to Activity 3.8, above, is given much greater significance. The effect is that it will be much easier in the future for those who act in response to a promise of extra payment, or some other benefit, by simply doing what they are already contracted to do, to enforce that promise (it is important to cross reference your reading here with Chapter 10 in relation to economic duress). page 47 page 48 University of London International Programmes You should note that Glidewell LJ summarises the circumstances where, in his view, the ‘practical benefit’ approach will apply in six points, which relate very closely to the factual situation before the court and emphasise the need for the absence of economic duress or fraud. The application of Williams v Roffey was held to apply when: 1. There was a contract for the supply of goods or services. 2. A was unable to perform as promised (which can include economic reasons). 3. B agreed to pay more. 4. B obtained a practical benefit from that promise (as outlined above). 5. There was no fraud or duress by A to obtain that promise. 6. If the above are satisfied then consideration is found. There is no reason, however, why later courts should be restricted by these ‘criteria’ in applying the Williams v Roffey approach. It was previously thought that Williams v Roffey had not affected the related rule that part payment of a debt can never discharge the debtor from the obligation to pay the balance – see Re Selectmove (1995). However, in MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd [2016] EWCA Civ 553 the Court of Appeal held that a property owner was bound by an oral agreement with the occupier who had failed to make payments as provided by the parties’ original written agreement to accept a late payment and a revised schedule of further payments. It was said that the subsequent agreement conferred practical benefits upon the land owner who recovered some of the arrears immediately and benefitted because the premises would not now be left empty for a period. Arden LJ alone characterised the subsequent agreement as a ‘collateral unilateral contract’. It was collateral because it was distinct from the original licence to occupy the premises agreed between the parties; it was unilateral because, so long as the licensee did an act i.e. occupied the premises and paid the renegotiated fees, the land owner would be bound by his promise to accept the deferral of the arrears. Part payment of debt This rule does not derive from Stilk v Myrick but from the House of Lords decision in Foakes v Beer (1884). As with the general rule about existing obligations, if something extra is done (for example, paying early, or giving goods rather than money), then the whole debt will be discharged (as held in Pinnel’s Case (1602)). But in Foakes v Beer (1884) it was said that payment of less than is due on or after the date for payment will never provide consideration for a promise to forgo the balance. In Foakes v Beer the House of Lords held, with some reluctance, that the implication of the rule in Pinnel’s Case was that Mrs Beer’s promise to forgo the interest on a judgment debt, provided that Dr Foakes paid off the main debt by instalments, was unenforceable. This common law rule has been regarded with some disfavour over the past 100 years and in some circumstances its effect can be avoided by the equitable doctrine of promissory estoppel (discussed below, at Section 3.2). It was seen above that it is further qualified by the interpretation of Williams v Roffey which was used by the Court of Appeal in MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd (2016) because in many situations it may be to the creditor’s ‘practical benefit’ to get part of the debt, rather than to run the risk of receiving nothing at all. In such circumstances, the agreement to accept less will be supported by consideration and so will be contractually binding. Some doubt surrounds the decision in Williams v Roffey. Most recently in MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd (2016) the Court of Appeal expanded its area of application when in the past the same court in Re Selectmove (1995) confined the ambit of the decision. Further, South Caribbean Trading Ltd (‘SCT’) v Trafigura Beeher BV (2004) Colman J doubted the correctness of the decision in Williams v Roffey. In particular, Colman J noted that the decision was inconsistent with the long-standing rule that consideration must move from the promisee. Contract law 3 Consideration Activity 3.10 Read the case of Foakes v Beer, preferably in the law reports – (1884) 9 App Cas 605 (although extracts do appear in Poole). Which of the judges expressed reluctance to come to the conclusion to which they felt the common law (as indicated by Pinnel’s case) bound them? What was the reason for this reluctance? Activity 3.11 Why do you think that in the past the Court of Appeal has been reluctant to overturn the decision in Foakes v Beer? Do more recent cases exhibit a more flexible approach? 3.1.4 Past consideration Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick Chapter 5 ‘Consideration and form’ – Section 5.18 ‘Past consideration’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 4 ‘Enforceability of promises: Consideration and promissory estoppel’ – Section 1C ‘Consideration must be sufficient but need not be adequate’. A further rule about the sufficiency of consideration states that generally the consideration must be given after the promise for which it is given to make it enforceable. A promise which is given only when the alleged consideration has been completed is unenforceable. The case of Re McArdle (1951) provides a good example. The plaintiff had carried out work refurbishing a house in which his brothers and sister had a beneficial interest. He then asked them to contribute towards the costs, which they agreed to do. It was held that this agreement was unenforceable, because the promise to pay was unsupported by consideration. The only consideration that the plaintiff could point to was his work on the house, but this had been completed before any promise of payment was made. It was therefore ‘past consideration’ and so not consideration at all. As with many rules relating to consideration, there is an exception to the rule about past consideration. The circumstances in which a promise made after the acts constituting the consideration will be enforceable were thoroughly considered in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long (1979). Lord Scarman laid down three conditions which must be satisfied if the exception is to operate. 1. The act constituting the consideration must have been done at the promisor’s request. (See, for example, Lampleigh v Braithwaite (1615).) 2. The parties must have understood that the work was to be paid for in some way, either by money or some other benefit. (See, for example, Re Casey’s Patents (1892).) 3. The promise would be legally enforceable had it been made prior to the acts constituting the consideration. The second of these conditions will be the most difficult to determine. The court will need to take an objective approach and decide what reasonable parties in this situation would have expected as regards the question of whether the work was done in the clear anticipation of payment. Activity 3.12 Why was the approach taken in Re Casey’s Patents not applied so as to allow the plaintiff to succeed in Re McArdle, since it was obvious that the improvement work would benefit all those with a beneficial interest in the house? Activity 3.13 Jack works into the night to complete an important report for his boss, Lisa. Lisa is very pleased with the report and says ‘I know you’ve worked very hard on this: I’ll make sure there’s an extra £200 in your pay at the end of the month’. Can Jack enforce this promise? page 49 page 50 University of London International Programmes Self-assessment questions 1. What is an ‘executory’ contract? 2. Is the performance of an existing obligation owed to a third party good consideration? 3. What principle relating to consideration is the House of Lords’ decision in Foakes v Beer authority for? Summary The doctrine of consideration is the means by which English courts decide whether promises are enforceable. It generally requires the provision of some benefit to the promisor, or some detriment to the promisee, or both. The ‘value’ of the consideration is irrelevant, however. The performance of existing obligations will generally not amount to good consideration, unless the obligation is under a contract with a third party, or the promisee does more than the existing obligation requires. This rule is less strictly applied following Williams v Roffey. Part payment of a debt can never in itself be good consideration for a promise to discharge the balance. Consideration must not be ‘past’, unless it was requested, was done in the mutual expectation of payment and is otherwise valid as consideration. Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 4 ‘Consideration and promissory estoppel’. 3.2 Promissory estoppel Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 5 ‘Consideration and form’ – Section 5.22 ‘Estoppel’ to Section 5.29 ‘Conclusion: the future of consideration’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 4 ‘Enforceability of promises: consideration and promissory estoppel’ – Section 2 ‘Promissory estoppel’. 3.2.1 The equitable concept of promissory estoppel The doctrine of promissory estoppel is concerned with the modification of existing contracts. The position under the classical common law of contract was that such modification would only be binding if consideration was supplied and a new contract formed. Thus in a contract to supply 50 tons of grain per month at £100 per ton for 5 years, if the buyer wanted to negotiate a reduction in the price to £90 per ton, because of falling grain prices, this could only be made binding if the buyer gave something in exchange (for example, agreeing to contribute to the costs of transportation). Alternatively the two parties could agree to terminate their original agreement entirely, and enter into a new one. The giving up of rights under the first agreement by both sides would have sufficient mutuality about it to satisfy the doctrine of consideration. These procedures are a cumbersome way of dealing with the not uncommon situation where the parties to a continuing contract wish to modify their obligations in the light of changed circumstances. It is not surprising, therefore, that the equitable doctrine of promissory estoppel has developed to supplement the common law rules. This allows, in certain circumstances, promises to accept a modified performance of a contract to be binding, even in the absence of consideration. The origin of the modern doctrine of promissory estoppel is found in older cases such as Hughes v Metropolitan Railways but was more widely developed in the judgment of Denning J (as he then was) in the case of Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd (1947). The facts of the case concerned the modification of the rent payable on a block of flats during the Second World War. The importance of the case, however, lies in the Contract law 3 Consideration statement of principle which Denning set out – to the effect that ‘a promise intended to be binding, intended to be acted on, and in fact acted on, is binding so far as its terms properly apply’. Applying this principle, Denning held that a promise to accept a lower rent during the war years was binding on the landlord, despite the fact that the tenant had supplied no consideration for it. You should read this case in full. The common law long recognised the concept of ‘estoppel by representation’. Such an estoppel only arises, however, in relation to a statement of existing fact, rather than a promise as to future action: see Jorden v Money (1854). The concept of ‘waiver’ had also been recognised by both the common law and equity as a means by which certain rights can be suspended, but then revived by appropriate notice. See, for example, Hickman v Haynes (1875), Rickards v Oppenheim (1950) and Hughes v Metropolitan Railway (1877). It was this last case upon which Denning J placed considerable reliance in his decision in High Trees House. The concept of waiver, however, had not applied to situations of part payment of debts. Note the suggestion of Arden LJ in Collier v P & MJ Wright (Holdings) Ltd (2007), based upon the obiter dictum of Denning J, that promissory estoppel has the effect of extinguishing the creditor’s right to the balance of a debt when he has accepted a part payment of the debt. Under the modern law the concept of waiver has been effectively subsumed within ‘promissory estoppel’. 3.2.2 The limitations on promissory estoppel The doctrine of estoppel has been considered in a number of reported cases since 1947 and now has fairly clearly defined limits. A most valuable summary of the general effect of these cases was provided by Kitchin LJ in MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd (2016): Drawing the threads together, it seems to me that all of these cases are best understood as illustrations of the broad principle that if one party to a contract makes a promise to the other that his legal rights under the contract will not be enforced or will be suspended and the other party in some way relies upon that promise, whether by altering his position or in any other way, then the party who might otherwise have enforced those rights will not be permitted to do so where it would be inequitable having regard to all of the circumstances. Need for existing legal relationship It is generally, though not universally, accepted that promissory estoppel operates to modify existing legal relationships, rather than to create new ones. The main proponent of the opposite view was Lord Denning himself who, in Evenden v Guildford City FC (1975), held that promissory estoppel could apply in a situation where there appeared to be no existing legal relationship at all between the parties. Need for reliance At the heart of the concept of promissory estoppel is the fact that the promisee has relied on the promise. It is this that provides the principal justification for enforcing the promise. The lessees of the property in High Trees House had paid the reduced rent in reliance on the promise from the owners that this would be acceptable. They had no doubt organised the rest of their business on the basis that they would not be expected to pay the full rent. It would therefore have been unfair and unreasonable to have forced them to comply with the original terms of their contract. It has sometimes been suggested that this reliance must be ‘detrimental’, but Denning consistently rejected this view (see, for example, W J Alan & Co v El Nasr (1972)) and it now seems to be accepted that reliance itself is sufficient. A ‘shield not a sword’ This is related to the first point (concerning the need for an existing relationship). The phrase derives from the case of Combe v Combe (1951). A wife was trying to sue her former husband for a promise to pay her maintenance. Although she had provided no consideration for this promise, at first instance she succeeded on the basis of page 51 page 52 University of London International Programmes promissory estoppel. The Court of Appeal, however, including Lord Denning, held that promissory estoppel could not be used as the basis of a cause of action in this way. Its principal use was to provide protection for the promisee (as in High Trees House – providing the lessees with protection against an action for the payment of the full rent). As Lord Denning put it: consideration ‘remains a cardinal necessity of the formation of a contract, though not of its modification or discharge.’ English courts have resisted attempts to found an action on a promissory estoppel. See Baird Textile Holdings Ltd v Marks & Spencer Plc (2001) although note the different approach taken by the High Court of Australia in Waltons Stores (Interstate) Ltd v Maher (1988). Must be inequitable for the promisor to go back on the promise The doctrine of promissory estoppel has its origins in equitable ‘waiver’. It is thus regarded as an equitable doctrine. The importance of this is that a judge is not obliged to apply the principle automatically, as soon as it is proved that there was a promise modifying an existing contract which has been relied on. There is a residual discretion whereby the judge can decide whether it is fair to allow the promise to be enforced. The way that this is usually stated is that it must be inequitable for the promisor to withdraw the promise. What does ‘inequitable’ mean? It will cover situations where the promisee has extracted the promise by taking advantage of the promisor. This was the case, for example, in D & C Builders v Rees (1966) where the promise of a firm of builders to accept part payment as fully discharging a debt owed for work done was held not to give rise to a promissory estoppel, because the debtor had taken advantage of the fact that she knew that the builders were desperate for cash. Impropriety is not necessary, however, as shown by The Post Chaser (1982), where the promise was withdrawn so quickly that the other side had suffered no disadvantage from their reliance on it. In those circumstances it was not inequitable to allow the promisor to escape from the promise. Doctrine is generally suspensory Whereas a contract modification which is supported by consideration will generally be of permanent effect, lasting for the duration of the contract, the same is not true of promissory estoppel. Sometimes the promise itself will be time limited. Thus in High Trees House it was accepted that the promise to take the reduced rent was only to be applicable while the Second World War continued. Once it came to an end, the original terms of the contract revived. In other cases, the promisor may be able to withdraw the promise by giving reasonable notice. This is what was done in Tool Metal Manufacturing Co Ltd v Tungsten Electric Co Ltd (1955). To this extent, therefore, the doctrine is suspensory in its effect. While it is in operation, however, a promissory estoppel may extinguish rights, rather than delay their enforcement. In both High Trees House and the Tool Metal Manufacturing case it was accepted that the reduced payments made while the estoppel was in operation stood and the promisor could not recover the balance that would have been due under the original contract terms. More recently, however, it was said obiter dicta in MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd (2016) that even though a creditor accepts part payment of a debt by instalments it will not necessarily result in the ‘extinction’ of the creditor’s right to claim the balance of any instalment in respect of which part payment has been been made. Where ‘promise’ is prohibited by legislation Evans v Amicus Healthcare Ltd (2003) concerned the use of embryos created by IVF prior to the breakdown of the couple’s relationship. The man wished the embryos to be destroyed, the woman to have the embryos used. In this context it was found, inter alia, that the man had not given such assurances to the woman as to create a promissory estoppel because the relevant legislation allowed him to withdraw his consent to the storage of the embryos at any time. This judgment contains an important discussion as to the current state of promissory estoppel and its possible future development. Contract law 3 Consideration A clear and unambiguous statement Where the words used to make the statement claimed as the basis for a promissory estoppel were ambiguous and capable of being interpreted in several ways (including one which would not support the estoppel) then the words could not be said to found an estoppel unless the representee sought and obtained clarification of the statement. See Kim v Chasewood Park Residents [2013] EWCA Civ 239 and Closegate Hotel Development (Durham) Ltd v McLean [2013] EWHC 3237 (Ch). Activity 3.14 Why was Denning’s statement of principle in High Trees House seen as such a potentially radical development in the law? Activity 3.15 Do you think that the doctrine of promissory estoppel is still needed, now that Williams v Roffey has made it much more likely that a modification of a contract will be found to be supported by consideration? Self-assessment questions 1. How does ‘promissory estoppel’ differ from common law estoppel, and from ‘waiver’? 2. What is the meaning of the phrase ‘a shield not a sword’ in the context of promissory estoppel? 3. What important statement of principle did Denning J make in the case of Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd? Summary Generally the modification of a contract requires consideration in order to be binding. The doctrine of promissory estoppel, however, provides that in certain circumstances a promise may be binding even though it is not supported by consideration. The main use of the doctrine has been in relation to the modification of contracts, but it is not clear whether it is limited in this way. The doctrine is only available as a shield, not a sword; there must have been reliance on the promise; it must be inequitable to allow the promisor to withdraw the promise; but it may well be possible to revive the original terms of the contract by giving reasonable notice. Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 4 ‘Consideration and promissory estoppel’. Sample examination question Simone owns five terraced houses which she is planning to rent to students. The houses all need complete electrical rewiring before they can be rented out. Simone engages Peter to do this work during August, at an overall cost of £5,000, payable on completion of the work. After rewiring two of the houses Peter finds that the work is more difficult than expected because of the age of the houses. On 20 August he tells Simone that he is using more materials than anticipated and that the work will take much longer than he originally thought. He asks for an extra £500 to cover the cost of additional materials. Simone agrees that she will add this to the £5,000. In addition, because she is anxious that the houses should be ready for occupation before the start of the university term, she says that she will pay an extra £1,000 if the work is completed by 15 September. Peter completes the work by 15 September, but Simone says that she is now in financial difficulties. She asks Peter to accept £5,000 in full settlement of her account. He reluctantly agrees, but has now discovered that Simone’s financial problems were less serious than she made out and wishes to recover the additional £1,500 he was promised. Advise Peter. page 53 page 54 University of London International Programmes Advice on answering the question This question is concerned with the role of consideration in the modification of contracts, and the doctrine of promissory estoppel. There are three separate issues which you will need to consider. uu Was Simone’s promise to pay the extra £500 a binding variation of the contract? uu Was Simone’s promise of an extra £1,000 if the work is completed by 15 September a binding variation of the contract? uu Is Peter’s promise to take the £5,000 in full settlement binding on him? The first two questions involve discussion of what amounts to consideration. If Peter has provided consideration for Simone’s promises, then he will be able to hold her to them. The answer to the third question will depend to some extent on the answer to the first two. If there has been no binding variation of the original contract, then Peter is not entitled to more than £5,000 in any case. If there has been a binding variation, then the question will arise as to whether he is precluded from recovering the extra money because of the doctrine of promissory estoppel. As to the promised £500, you will need to consider whether the fact that Peter is buying additional materials is good consideration for this promise. Simone may argue that it was implicit in the original contract that the cost of all materials needed would be included in the £5,000. The fact that Peter has made an underestimate is not her responsibility. Similarly, in relation to the promised extra £1,000, is Peter doing any more than he is contractually obliged to do, in that it seems likely that the original contract was on the basis that the work was to be done by the end of August? In answering both these questions you will need to deal with the principle in Stilk v Myrick and the effect on this of Williams v Roffey. This will involve identifying any ‘practical benefit’ that Simone may have gained from her promises. If such a benefit can be identified and there is no suggestion of improper pressure being applied by Peter, then the variations of the contract will be binding on Simone. The effect of the subsequent decisions in cases such as Re Selectmove, SCT v Trafigura and MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd (2016) upon Williams v Roffey could also be considered. In relation to the third issue, assuming that there has been a binding variation, you will need to decide whether Foakes v Beer applies (in which case Peter will be able to recover the £1,500), or whether Simone can argue that Peter is precluded from recovery by the doctrine of promissory estoppel. In relation to the latter issue, one of the matters which you will need to consider is whether promissory estoppel can apply in a situation of a debt of this kind, as opposed to money payable under continuing contracts such as those involved in High Trees House and Tool Metal Manufacturing v Tungsten Electric. You will also need to consider whether the fact that Simone may have not been fully truthful about her financial position may make it ‘inequitable’ for her to rely on promissory estoppel (see D & C Builders v Rees). The suggestion of Arden LJ in Collier v P & MJ Wright (Holdings) could also be considered. Quick quiz Question 1 In Currie v Misa (1875) it was said that a valuable consideration, in the sense of the law, may consist either in some right, interest, profit or benefit accruing to the one party, or some forbearance, detriment, loss or responsibility given, suffered or undertaken by the other. Which of the following statements best represents what this statement means? a. Consideration involves the signalling of equal exchange of goods to ensure that all contracts are fairly enforceable. b. Consideration allows all promises to be enforced by showing that one party was thoughtful about the other when they entered into negotiations. Contract law 3 Consideration c. Consideration is some benefit accruing to one party or some detriment suffered by the other. It is a badge of enforceability. d. Consideration involves a profit being obtained by one party at the expense of the other. No exchange is required for the contract to be enforced. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Which of the following scenarios, in light of the law on consideration, would most likely allow K, in contract law, to enforce a contract for a new mobile phone? a. J promises K a brand new mobile phone. b. J promises K a brand new mobile phone if he takes it out of the box that it came in. c. J promises K a brand new mobile phone for £5 which is far below its market value. d. J promises K a brand new mobile phone worth £150 because he gave him £150 worth of compact discs last year. K had no idea of this when he gave the compact discs to J. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following statements represents the common law view of part payment of debt? a. If one party (A) suggests that (B) be let off part of the payment of an existing debt then (A) cannot then sue for recovery of that debt. b. If one party (A) suggests that (B) be let off part payment of an existing debt then (A) cannot sue for recovery of that debt before 25 years have passed. c. If one party (A) suggests that (B) be let off part payment of an existing debt then (A) can only sue for recovery of that debt if she can show that (B) was lying about his financial situation. d. If one party (A) suggests that (B) be let off part of the payment of an existing debt then (A) can sue for recovery of that debt. e. Don’t know. Question 4 In the case of The Eurymedon (1975) Lord Wilberforce said: ‘An agreement to do an act which the promisor is under an existing obligation to a third party to do may quite well amount to valid consideration and does so in the present case: the promise obtains the benefit of a direct obligation which he can enforce.’ Which of the following scenarios best reflects this view? Choose one answer. a. If a carpenter has a contract with a builder who has a contract with a homeowner to fit the kitchen in that house then if he receives £500 in addition to his original fee, just to get the job done on time, he will have provided sufficient consideration for this additional £500. b. If a carpenter has a contract with a homeowner to fit the kitchen in that house then if he receives £500 in addition to his original fee, just to get the job done on time, he will have provided sufficient consideration for this additional £500. c. If a carpenter has a contract with a builder who has a contract with a homeowner to fit the kitchen then any promise to give £500 would be unsupported by consideration and so not enforceable by the carpenter. page 55 page 56 University of London International Programmes d. If the carpenter has a contract with a builder and he finishes the fitting of the kitchen of the householder and the builder says ‘I will give you a bonus for fitting the kitchen’. The builder later refuses. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Which of the following statements is made by Russell LJ in Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd (1990) to reflect the current view of the courts in the requirement of consideration in any contract? Choose one answer. a. Consideration remains the cornerstone of English contract law. Any attempt to remove the requirement of its presence has always been defeated. b. It would be wrong to extend the doctrine of promissory estoppel, whatever its precise limits at the present day, to the extent of abolishing in this back handed way the doctrine of consideration. c. Consideration there must still be but, in my judgement, the courts nowadays should be more ready to find its existence so as to reflect the intention of the parties to the contract where the bargaining powers are not unequal and where the finding of consideration reflects the true intention of the parties. d. If it be objected that the propositions above contravene the principle in Stilk v Myrick, I answer that in my view they do not: they refine and limit the application of that principle but they leave the principle unscathed. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the subject guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What are the essential elements of the concept of ‘consideration’? 2. What is the significance of consideration to the English law of contract? 3. What types of behaviour will the courts treat as valid consideration? 4. In what situations will the performance of, or promise to perform, an existing obligation amount to consideration for a fresh promise? 5. What is the definition of ‘past consideration’? 6. What is the role of consideration in the modification of existing contracts? 7. What are the essential elements of the doctrine of ‘promissory estoppel’? 8. How does the doctrine of promissory estoppel lead to the enforcement of some promises which are not supported by consideration? Part I Requirements for the making of a contract 4 Other formative requirements: intention, certainty and completeness Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58 4.1 The intention to create legal relations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59 4.2 Certainty of terms and vagueness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62 4.3 A complete agreement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67 page 58 University of London International Programmes Introduction We have examined many of the basic requirements necessary for the formation of an enforceable contract: offer and acceptance (Chapter 2) and consideration (Chapter 3). To these requirements we must add three more: 1. That the parties intend to create legal relations; 2. That the terms of their agreement are certain and not vague; and 3. That their agreement is a complete agreement that does not need further development or clarification. Once all of these requirements are present, courts will, in the absence of any vitiating elements, recognise an agreement as an enforceable contract. We will examine each of these new requirements in turn. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the other formative requirements: intention to create legal relations, certainty and completeness to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu Why courts require an intention to create legal relations. uu The difference between domestic agreements and commercial agreements with regard to an intention to create legal relations. uu The key factors in determining whether or not an intention to create legal relations exists. uu What is meant by ‘certainty of terms’ and the difference between contracts where there is certainty of terms and those where there is not. uu Why courts insist upon certainty of terms. uu The concept of ‘vagueness’ in relation to contractual provisions. uu The rationale behind the requirement of contractual completeness. uu Whether, and if so when, a court may ‘complete’ an agreement. Contract law 4 Other formative requirements: intention, certainty and completeness 4.1 The intention to create legal relations Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 6 ‘Intention to create legal relations’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 5 ‘Intention to be legally bound and capacity to contract’ – Section 1 ‘Intention to be legally bound’. ¢¢ Hedley, S. ‘Keeping contract in its place – Balfour v Balfour and the enforceability of informal agreements’ (1985) 5 Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 391. This article can be found in HeinOnline using the Online Library. In Chapter 2 we examined the importance of intention in relation to an offer: for a statement to be an offer, it must be made with the intention that it be binding upon acceptance. It is also essential that all the parties to an agreement have an intention to create legal relations. What this means is that the parties intend that legal consequences attach to their agreement. In short, the parties intend that the agreement will be binding with recourse to some external adjudicator (a court or arbitrator) for its enforceability. The necessity for intention is most evident in domestic and social agreements. These are agreements between friends (e.g. A agrees to host the bridge club at her house if B will bring the food to feed the club) or agreements made between family members (e.g. sister agrees with brother that she will not play her radio loudly if brother will keep his hamster securely in its cage). In this context there is generally an offer by one party, which is accepted by the other party and supported by consideration. So far, the agreement looks like an enforceable contract. The parties, however, probably do not intend a breach of the agreement to result in legal action. Their agreement lacks an intention to create legal relations and is thus not a contract because they did not intend it to be. The agreement has no legal effect at all. Traditionally, the law has distinguished between domestic and social agreements and commercial agreements. In the case of domestic and social agreements, it is presumed that there is not an intention to create legal relations. In the case of commercial agreements, it is presumed that there is an intention to create legal relations. In either instance, the facts of the case may displace the presumption the law would otherwise make. For example, it may be that when neighbour A agreed to mow neighbour B’s lawn in exchange for the apples on B’s apple tree, both parties intended that this agreement would be legally enforceable. The determination of whether or not the parties intended to enter into legally binding relations is an objective one and context is all-important. What this means is that the courts will not examine the states of mind of the parties to the agreement (a subjective approach), but will ask whether or not reasonable parties to such an agreement would possess an intention to create legal relations. See Edmonds v Lawson [2000] EWCA Civ 69. In President of the Methodist Conference v Preston [2013] UKSC 29 the Supreme Court held that it was necessary to consider the appointment of a Methodist minister in the context of the factual background. In so doing, the Court found that there was no contractual intention. This objective approach applies regardless of whether the agreement is a social or domestic one or a commercial one. Social and domestic agreements The leading case is Balfour v Balfour [1919] 2 KB 571. Here, because the husband would be working overseas, he promised to pay his wife an amount of money each month. When the parties separated, the wife sued the husband for this monthly amount. The court refused to allow her action on the grounds that the agreement was not an enforceable contract because, at the outset of their agreement, it ‘was not intended by either party to be attended by legal consequences’. The parties did not intend that page 59 page 60 University of London International Programmes the agreement was one which could be sued upon. The judgment of Atkin LJ really seems to rest upon public policy arguments – that as a matter of policy, domestic agreements, commonly entered into, are outside the jurisdiction of the courts. His judgment also highlights a judicial concern that if such agreements could be litigated in the courts, the courts would soon be overwhelmed by such cases. Similar reasoning was applied in the case of Jones v Padavatton [1969] 2 All ER 616 to find that the agreement between a mother and her adult child did not create a contract. See also Coward v MIB [1963] 1 QB 259 where the court found that an agreement to take a friend to work in exchange for petrol money was an arrangement which lacked contractual intention. Increasingly in the modern world, domestic arrangements are beginning to take on a basis in contract law. Balfour v Balfour must be seen as a case which establishes a rebuttable presumption† that domestic agreements are not intended. An example of a situation in which the presumption was rebutted can be found in the decision in Merritt v Merritt [1970] 2 All ER 760. In this instance the spouses were already separated and the agreement was found to have an intention to create legal relations. A similar result followed in Darke v Strout [2003] EWCA Civ 176 as the court found that an agreement for child maintenance following the breakdown of a couple’s relationship did not lack an intention to create legal relations given the formality of the letter. Nor could it be said to be unenforceable for want of consideration since the woman had, in entering the agreement, given up statutory rights to maintenance. In Soulsbury v Soulsbury [2007] EWCA Civ 969 the Court of Appeal found that there was an intention to create legal relations between two former spouses when one agreed to forego maintenance payments in return for a bequest in the other’s will. It can be seen that in many of these cases between spouses the usual presumption is rebutted after the breakdown of the marriage relationship. A modern development concerns the legal enforceability of an agreement that precedes, rather than follows, the entering of a marriage known as a pre-nuptial agreement (colloquially a ‘pre-nup’). In Radmacher v Granatino [2010] UKSC 42 the Supreme Court upheld a decision that the husband was not entitled to an award of £5.5 million after the breakup of the marriage because such an award would give insufficient weight to the pre-nuptial agreement. This agreement acknowledged that neither party would acquire any benefit from the other’s property during the marriage and its execution was a condition of a substantial transfer of family wealth to the wife. Lady Hale dissented, arguing that there remained important policy considerations sufficient to justify a different approach to agreements made before and after marriage. When agreements are entered between non-family members with respect to what might be considered more trivial subjects such as the division of the proceeds of joint betting, the cases are less clear. In Simpkins v Pays [1955] 3 All ER 10 it was found that there was a contract where three co-habitees entered a competition together, whereas in Wilson v Burnett [2007] EWCA Civ 1170 it was held that there was no binding agreement to share bingo winnings. Activity 4.1 Think of the last three promises you have made to friends or family. Did these promises form agreements intended as contracts? Why (or why not)? Activity 4.2 How does Simpkins v Pays differ from Coward v MIB? Activity 4.3 A and B are married to each other. They agree that A will make all the mortgage payments on the marital home and that B will pay all other household bills. This arrangement carries on for two years whereupon A refuses to make any more mortgage payments. Can B sue A? † A rebuttable presumption is a presumption made by courts as to a certain state of facts until the contrary is proved. Contract law 4 Other formative requirements: intention, certainty and completeness Activity 4.4 A and B are married to each other. They agree that A will pay all the household expenses and that B will remain at home to care for their children. B subsequently takes up paid employment outside the home and another person cares for the children. Must A continue to pay the household expenses? Commercial agreements In relation to commercial agreements, courts will generally presume that an intention to create legal relations is present. See Esso Petroleum Ltd v Commissioners of Customs and Excise [1976] 1 All ER 117. This is an especially strong inference when the commercial context is an ongoing employment relationship (Dresdner Kleinwort Ltd v Atrill [2013] EWCA Civ 394). Exceptionally, the facts may disprove such an intention. In a sale of land, agreements are normally made ‘subject to contract’. This wording expressly displaces any presumption of contractual intention. In other situations, courts have found that the specific wording of the agreement in question displaced any contractual intention. See, for example: uu a comfort letter – Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Malaysia Mining Corporation Berhad [1989] 1 All ER 785 uu an honour clause – Rose and Frank Company v JR Crompton and Brothers Ltd [1925] AC 445. In most cases where the parties deal at arm’s length (i.e. they have no existing ties of family, friendship or corporate structure) the court will find a contractual intention. See Edmonds v Lawson (2000). Activity 4.5 Why might a commercial party not want an agreement to be an enforceable contract? Is such an agreement of any practical value? Summary Ultimately, the question of contractual intention is one of fact. The agreement in question must be carefully scrutinised to determine the nature of the parties’ agreement. Without an intention to create legal relations, there will not be a contract. Self-assessment questions 1. To what extent are courts examining whether or not the parties intend to take any dispute to a court for resolution? To what extent are the courts determining whether or not the agreement has certain terms? 2. Are courts influenced by the reliance of one party upon the promise of another in determining that a contractual intention is present? 3. Is the reasoning of the judges in Balfour v Balfour and Esso Petroleum v Commissioners of Customs and Excise based on public policy considerations or on the intentions of the parties to the agreements? 4. What factors do courts consider important in negativing contractual intention? Further reading ¢¢ Freeman, M. ‘Contracting in the Haven: Balfour v Balfour revisited’ in Halson, R. (ed.) Exploring the boundaries of contract. (London: Dartmouth Publishing Company, 1996) [ISBN 9781855217126]. page 61 page 62 University of London International Programmes 4.2 Certainty of terms and vagueness Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 4 ‘Certainty and agreement mistakes’ – Section 4.1 ‘Certainty’ and Section 4.2 ‘Vagueness’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 3 ‘Agreement Problems’ – Section 1 ‘Certainty’. An enforceable contract requires certainty of terms. That is to say, for an agreement to be a contract, it must be apparent what the terms of the contract are. If an important term is not settled, the agreement is not a contract. A statement cannot be an offer unless it is sufficiently certain. In Scammell v Ouston [1941] AC 251 the court found that the agreement was not enforceable because the terms were uncertain and required further agreement between the parties (see the discussion in Chapter 2). Viscount Maugham explained that because the terms were uncertain, there was no real agreement (a consensus ad idem) between the parties. The underlying rationale for this area of law can be seen in that if the terms cannot be determined with certainty, there is no contract for the court to interpret. It is not the role of the court to create the terms of the contract – for this would be to impose a contract upon the parties. Courts will nonetheless try to give legal force to the parties’ attempt to make a contract unless it is ‘legally or practically impossible to give [it] any sensible content’ (Scammel v Dicker [2005] EWCA Civ 405 at [30]). On this basis in Durham Tees Valley Airport v bmibaby (2010) it was held that an agreement to operate two aircraft from an airport for 10 years was not void for uncertainty because it did not specify a minimum number of passengers or flights. In some circumstances, particularly where the parties have relied upon an agreement, courts will more readily imply or infer a term or find that the essentials of a contract have been established. This can be seen in the decision in Hillas v Arcos [1932] All ER 494. Here, the agreement had been relied upon and the court was able to infer the intention of the parties based upon the terms in their agreement and the usage in the trade. Similarly, in RTS Flexible Systems Ltd v Molkerei Alois Muller Gmbh & Co KG [2010] UKSC 14 agreement had been reached on all terms of ‘economic significance’ and performance commenced. The Supreme Court said that an objective interpretation of the parties’ words and deeds suggested that they intended to enter a binding contract despite the fact that certain terms were not yet confirmed. Even if performance is almost complete and the parties throughout confidently expected to agree upon key terms, their actual failure to do so will mean that no contract comes into existence (British Steel Corp v Cleveland Bridge and Engineering Co Ltd [1984] 1 All ER 504). Activity 4.6 You agree with Z that you will buy a shirt from Z’s summer collection for £25. No size is specified in your agreement. Have you a contract? Explain. Activity 4.7 What is the difference between the decisions in Hillas and Scammell? Are there convincing reasons for deciding these cases differently? It may be that the agreement provides a mechanism, or machinery, to establish the term. In such a situation, there is certainty of terms. Thus, if interest on a loan is to be set at 1% above the Bank of England’s base rate on a certain date, then this is a certain term. It cannot be stated at the outset of the contract what the interest rate is, but certainty of terms exists because, on the relevant date, the interest rate can be determined by an agreed mechanism. There is a difference between a term which is meaningless and a term which has yet to be agreed. Where the term is meaningless, it can be ignored, leaving the contract as a whole enforceable. See Nicolene Ltd v Simmonds [1953] 1 QB 543. Contract law 4 Other formative requirements: intention, certainty and completeness Summary If the terms of an agreement are uncertain or vague, courts will not find a contract exists. Courts will not create an agreement between the parties. In a number of circumstances, courts will use various devices to ensure that terms which might appear uncertain are, in fact, certain. It may be possible to determine what the term is from the usage in the trade. A vague or meaningless term may be ignored. Self-assessment questions 1. Would an agreement to ‘use all reasonable endeavours’ to achieve a certain objective be enforceable? 2. What are the arguments in favour of allowing a court to establish the essential terms of an agreement? 4.3 A complete agreement Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 4 ‘Certainty and agreement mistakes’ – Section 4.3 ‘Incompleteness’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 3 ‘Agreement problems’ – Section 1C ‘Incompleteness’. To create an enforceable contract, parties must reach an agreement on all the major elements of their contract. The agreement must, in other words, be complete. There must be nothing left outstanding to be agreed upon at a later date. Completeness is an aspect of certainty of terms: unless an agreement is complete, a court is unable to state with certainty what agreement has been made between the parties. If there is no agreement on all of the essential elements of a bargain, there is no contract. There must be an agreement on matters such as price, either by fixing the price or establishing a mechanism to fix the price. What is essential in a contract will depend upon the nature of the contract. It is not possible to turn an incomplete bargain into a legally binding contract by merely adding together express and implied terms. Rather, a complete bargain must exist which may be supplemented by further implied terms Wells v Devani [2016] EWCA Civ 1106. There is no such thing as an agreement to agree. In Courtney & Fairbairn Ltd v Tolani Brothers (Hotels) Ltd (1975) it was held that there was no contract where the parties had simply agreed to negotiate. Their agreement was not enforceable as a contract. In Barbudev v European Cable Management Bulgaria EOOD [2012] EWCA Civ 548 a communication offering investment on ‘terms to be agreed’ was said to be no more than an unenforceable ‘agreement to agree’. The reason for this probably lies in the practical consideration that if the agreement is incomplete, it is not for the court to complete the agreement because the court would then be creating, rather than interpreting, the contract. In Walford v Miles [1992] 2 AC 128 Lord Ackner noted that the parties to negotiations had diametrically opposed aims and so their opposing interests could not be reconciled sufficiently to support in Walford an implied obligation to continue to negotiate in good faith with a particular party. In contrast, an undertaking not to negotiate with third parties (called a ‘lockout’ agreement) was, if for a fixed period, sufficiently certain to be enforceable (Pitt v PHH Asset Management Ltd [1994] 1 WLR 327). Activity 4.8 Your milkman leaves you a note to ask if you would like an order of bread at some point in the future. You reply that you would and you agree to pay his price of £1 per loaf. Is your agreement a contract? When will the bread be delivered? page 63 page 64 University of London International Programmes Activity 4.9 You offer to pay £200,000 for a house ‘subject to contract’. Although the house looks fabulous on a first viewing, subsequent inspection of it reveals that it suffers badly from damp. The vendor insists that you must buy the house as she has accepted your offer. Must you? In some instances, legislation or case law will enable the court to add the necessary term to the agreement. An example of this can be seen in s.8(2) of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 which provides that where the price in a contract for the sale of goods has not been determined the buyer must pay a reasonable price. Where this occurs, the agreement can be completed and an enforceable contract exists. In other instances, where the parties have acted in reliance upon what otherwise might be considered to be an incomplete agreement, courts have found that they were able to imply the necessary terms. For examples of this, see the decisions in Foley v Classique Coaches Ltd [1934] 2 KB 1 and British Bank for Foreign Trade Ltd v Novinex Ltd [1949] 1 KB 623. There are two different ways of rationalising what courts are doing in these instances. uu The first is that courts are protecting the parties’ reasonable reliance upon an agreement uu The second is that, because the parties have relied upon the agreement, it is easier to imply with certainty what the parties would originally have agreed upon as the essential terms. Activity 4.10 What elements have courts found essential in determining whether the agreement is complete? Why are these elements essential? Activity 4.11 In what instances have courts been prepared to ‘imply’ or ‘insert’ what appears to be an otherwise missing essential element? Why was the court prepared to do this? Summary The agreement must contain all the essential terms necessary to execute the agreement with certainty. If the agreement does not contain all the necessary terms, it will not be an enforceable contract. Courts will not create the contract between the parties. Self-assessment questions 1. Once the parties have begun to perform an agreement, are courts concerned to protect the reliance of the parties? 2. How do the previous dealings of the parties or the custom within a particular trade assist the court? See Scammell v Ouston (1941). Examination advice The matters considered in this chapter are unlikely to appear as a separate question on the examination paper. This does not mean that they are not important. They must be present in order to form an enforceable contract. The fact that the law insists upon their presence (and the circumstances in which the law ‘creates’ these elements) tells us a lot about the consensual nature of contract law. For examination purposes, however, the matters covered in this chapter are likely to appear as issues in a larger question involving a bigger issue. You must think about how these smaller issues fit within the larger issue. Thus, for example, does an intention to create legal relations also indicate a greater problem with the adequacy of consideration? Contract law 4 Other formative requirements: intention, certainty and completeness When you read examination questions that refer to an agreement, check to see if the agreement is domestic or social in nature – will intention to create legal relations be an issue in the context of that question? A party seeking to avoid contractual liability may do so on the ground that there was no intention to create legal relations. Where the agreement is between commercial parties, consider whether or not there are factors which displace the presumption of intention. With respect to ‘certainty’ and ‘completeness’, situations will arise where the words may be ambiguous. You must ask yourself whether this ambiguity creates a problem of certainty, or possibly a mistake. Always check to make sure an agreement is complete. Is there anything essential which remains outstanding? If there is, can a court imply or infer what this term should be? Sample examination question A promises her son B £1,000 per month if he begins his engineering studies at university. A’s brother, C, offers B a place in his house if B promises to finish his studies. B offers his girlfriend D £50 per month if she will drive him to the university each morning. Are any of these agreements enforceable? Advice on answering the question The best approach to an examination question of this nature is to break it down into its component parts. There are three agreements in question. Consider each in turn. Do not be afraid to use sub-headings to assist the clarity of your answer. 1. Agreement between A and B A is B’s mother and automatically creates an issue of intention. You should consider the general nature of the test set out by Lord Atkin in Balfour v Balfour. Next, consider the similar facts of Jones v Padavatton. Without some element to distinguish it from Jones, it is likely that a court would reach the same outcome. Is such an element present? Note, however, the more general focus of intention (as opposed to the relationship of the parties) in Edmonds v Lawson. 2. Agreement between C and B C is B’s uncle; again, intention to create legal relations becomes an issue. However, an uncle is one step removed from a parent or a spouse and courts might more readily infer such an intention. You need to consider what is established by the cases cited above in (1). An additional problem present here is that the agreement may not be certain in its terms. How long can B stay in the house? What part of the house can B occupy? How does Scammell v Ouston apply to this situation? This lack of certainty suggests that this is not a complete agreement. Is there a way for the court to infer what these terms (such as the length of B’s tenure) are? See Foley v Classique Coaches Ltd. 3. Agreement between B and D D is B’s girlfriend – the agreement thus occurs within a social context. In this sense, it is similar to Coward v MIB. Here, the House of Lords found that, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, they would be reluctant to infer that agreements to take one’s friend to work in exchange for remuneration gave rise to a contract. The relationship lacked intention – neither party contemplated that they were entering into legal obligations. Note, however, Lord Cross’s judgment in Albert v MIB – does it provide a ground for allowing that the B/D arrangement is a contract? page 65 page 66 University of London International Programmes Quick quiz Question 1 Which of these statements was made by Denning LJ in Merritt v Merritt (1970) to indicate the view of the courts when deciding whether parties had an intention to create legal relations? a. A husband’s word is his bond. Even if a man promises his wife flowers daily at the beginning of their marriage there is no reason why a wife could not sue on that promise 25 years later when all he brings her is complaints of the quality of her cleaning. b. Contracts should not be ... the sports of an idle hour, mere matters of pleasantry and badinage, never intended by the parties to have any serious effect whatever. c. It is necessary to remember that there are agreements between parties which do not result in contracts within the meaning of that term in our law [including] arrangements that are made between husband and wife. d. In all these cases the court does not try to discover the intention by looking into the minds of the parties. It looks at the situation in which they were placed and asks itself would reasonable people regard this agreement as intended to be binding. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Which of these statements best summarises the reasons why the House of Lords refused to enforce the husband’s promise to his wife in Balfour v Balfour (1919)? a. The law does not interfere in the relations between family members and promises made between family members are binding, if at all, only as a matter of honour and not law. b. When the husband made the promise to his wife, the couple had not yet separated and the husband was not bound to pay his wife any money. c. When the husband promised to pay his wife an allowance he did so without any intention to create legal relations. d. When the husband promised to pay his wife an allowance he did so without any intention to create legal relations and his wife provided no consideration for his promise. e. Don’t know. Question 3 In Jones v Padavatton (1969) Fenton Atkinson LJ found that the presumption against an intention to create legal relations in domestic agreements was not rebutted because: a. A promise by a parent to pay a child an allowance during the course of their studies was no more than a family arrangement not intended to give rise to legal consequences. b. The daughter provided no consideration to support her mother’s promise to pay her an allowance during her studies. c. In examining the subsequent history of events between the mother and daughter, it was apparent that the parties had not exhibited an intention to create legal relations at the time the mother promised to fund the daughter’s studies. Contract law 4 Other formative requirements: intention, certainty and completeness d. While there was an intention to create legal relations when the mother’s promise was made, the subsequent alterations in the ‘method’ by which the mother funded the daughter’s studies removed this intention. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Which of the following most accurately states the position in relation to uncertain and incomplete agreements? a. A court will never enforce an agreement which omits any term. b. Courts distinguish between executor agreements and partially executed agreements in determining whether an agreement is too uncertain to enforce. c. A court will never enforce an agreement which omits an essential term. d. Courts will not enforce an agreement unless all the terms are written. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Which of the following is not a method by which a term, seemingly uncertain or vague, can be given certainty? a. That the parties agree that one of the parties resolve the issue. b. That the matter is resolved by legislation provision. c. That the agreement provides that the term be resolved by judicial decision. d. That the agreement provides that the resolution of a particular matter is determined by a third party to the contract. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the subject module or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is meant by ‘an intention to create legal relations’? 2. Why do courts require an intention to create legal relations? 3. What is the difference between domestic agreements and commercial agreements with regard to an intention to create legal relations? 4. What are the most important factors in determining whether or not an intention to create legal relations exists? 5. What is meant by ‘certainty of terms’? 6. What is the difference between contracts where there is certainty of terms and those where there is not? 7. Why do courts require certainty of terms? 8. What is the concept of ‘vagueness’? 9. Why must the agreement be complete? 10. In what circumstances can a court ‘complete’ an agreement? page 67 page 68 Notes University of London International Programmes Part II Content of a contract and regulation of terms 5 The terms of the contract Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70 5.1 Is a statement or assurance a term of the contract? . . . . . . . . . . . .71 5.2 The use of implied terms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74 5.3 The classification of terms into minor undertakings and major undertakings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84 page 70 University of London International Programmes Introduction In the last three chapters we have considered the basic elements necessary to form an enforceable contract: offer and acceptance (Chapter 2), consideration (Chapter 3) and certainty and intention (Chapter 4). We will now examine the content, or terms, of the resulting contract to ascertain the extent of the obligations undertaken. What are the parties to the contract obliged to do or not do? It is of critical importance to establish the terms of any contract because the question of whether or not the contract has been breached depends upon whether one party has failed to perform according to the terms of the contract. In addition, the rights that an injured party has following a breach of contract by another party depend upon whether the term breached was a major term or a minor term. This chapter deals with three areas concerning the content of the contract. These are: uu whether a particular statement made or assurance given in the course of the negotiations leading up to the contract forms part of the contract uu how terms (and equivalent obligations) can be implied into a contract either by operation of a statute or by common law uu how, and why, the major or essential undertakings of a contract are distinguished from the minor or inessential ones. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the terms of a contract to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu Being able to identify when a statement forms a part of the contract (and when it does not). uu The remedial consequences of the classification of a statement as respectively, a term and (in outline at this stage) a ‘mere’ representation. uu Why and when will courts imply terms into contracts. uu The limits upon courts in implying terms into contracts. uu The different categories of contractual terms. uu How to determine within which category a particular term should be placed. uu The consequences of this classification. Contract law 5 The terms of the contract 5.1 Is a statement or assurance a term of the contract? Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 8 ‘What is a term?’ and Chapter 9 ‘The sources of contractual terms’ – Section 9.1 ‘Introduction’ and Section 9.2 ‘The parol evidence rule’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 6 ‘Content of the contract and principles of interpretation’ – Section 1 ‘Pre-contractual statements: terms or mere representations?’ and Section 2 ‘Written contracts’. Contracts in practice are never as straightforward as the examples explained in legal textbooks. Textbooks leave the reader with the impression that the contractual process is an orderly process commencing with an invitation to treat, followed by an offer and a corresponding acceptance. The reality of many situations, however, is one of statements forming lengthy, sometimes contradictory, exchanges and negotiations prior to the formation of a contract. In this chapter we determine which of these statements form a part of the contract and which do not. This determination is important because those statements that form a part of the contract are terms – and breach of a term of a contract gives rise to a right to damages and, possibly, a right to terminate the contract (see Chapter 13: ‘Performance and breach’). If the statement does not form a part of the contract, it is said to be a mere representation. If a mere representation is not true, there is not a breach of contract because the representation is not a part of the contract. Someone who suffers loss as a result of their reliance upon a mere representation will not be able to sue for breach of contract but will have other remedies available. These remedies for misrepresentation (a misrepresentation is an untrue representation) are examined in Chapter 9. When you study misrepresentation it is important to link your reading of that chapter to this section of Chapter 5. The range of remedies for misrepresentation is introduced in Section 5.1.1 below. A brief observation on terminology. You will notice in your reading on this topic that many of the cases discuss whether the statement is a warranty (by which they mean a term of the contract or of a separate, collateral, contract) or a representation (a ‘mere puff’; a statement which has no legal significance). Use of the term ‘warranty’ has been avoided here because it confuses the discussion set out in Section 5.3: ‘The classification of terms into minor and major undertakings’, in which the term ‘warranty’ is used to mean something slightly different. 5.1.1 False representations Prior to the enactment of the Misrepresentation Act 1967, and the development of the tort of negligent misstatement in Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd [1964] AC 465, a misrepresentation had to be fraudulent in order for the injured party to receive damages and the proof of fraud was very difficult. Because of this, the older cases are concerned with attempts by the injured party to establish that the statement was a contractual term (for which damages were available) rather than a representation. Lord Denning MR described these attempts in Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] QB 801. At present, however, the matter is not so clear-cut. In many circumstances it is now advantageous for a party to establish that the statement is a representation and actionable as a misrepresentation under the Misrepresentation Act 1967. A point examined further in Chapter 9. Examination advice We have just seen that a finding that a statement made in negotiations is not a term is not now so serious for the party who relied upon it because the victim of a misrepresentation now has a greater range of remedies available than in the past. Nonetheless, the proper classification of the statement made in negotiations is of great importance when answering problem type questions. If in your answer page 71 page 72 University of London International Programmes you wrongly classify a statement made in negotiations as a term when it is a mere representation this will lead you to write about the remedies available for breach of contract which are not relevant and so you will gain little or no credit. The criterion of relevance is applied strictly by markers. There are no ‘charity marks’ for a discussion of an area of law, no matter how well written and supported by cases, if it is not relevant to the question asked. It is a feature of many legal problems that a piece of initial analysis is a ‘signpost’ that directs the rest of your answer in a particular direction. Any such ‘signpost’ must be identified and conclusions reached after careful application of the relevant principles. Finding the intention of the parties If, then, it is of critical importance to establish if the statement is a term of the contract or a ‘mere’ representation which is not a part of the contract, how is this ascertained? At one level the answer is simple, it all depends on the intention (objectively ascertained of course) of the parties. Do their words and conduct indicate to a reasonable person that the statement was intended to be mere representation or, alternatively, that it was intended to be a contractual term? Difficulty arises in the application, as opposed to the statement, of this test. The courts have utilised a small number of factors or ‘rules of thumb’ to assist them. It is important to emphasise that these are factors, not rules. If one of these factors applies it inclines to a conclusion that the statement was intended to be either a mere representation or a term. They are not rules which would dictate a certain conclusion. When applied to a set of facts one factor might suggest the statement was intended to be a term, another that it was a mere representation. In such cases the competing factors must be weighed one against the other to see which, on the facts, is the stronger. The factors referred to by the courts include the following. The cases suggest that the first factor may be the most important. uu Whether the statement maker has special knowledge of the matter in question – where the representor has greater knowledge of the matter than the other, this is indicative that the statement is intended to be a term – Dick Bentley v Harold Smith Motors [1965] 2 All ER 65; where the representee has greater knowledge of the matter than the other, this is indicative that the statement is intended to be a mere representation – Oscar Chess Ltd v Williams [1957] 1 All ER 325). uu Whether the maker of the statement accepted responsibility for the soundness of the statement – where such responsibility is assumed, this indicates that the statement was intended to be a term (Shawel v Reade [1913] 2 IR 64). uu The importance attached to the statement – the more important the matter, the greater the likelihood that the parties intended the statement to be a term (Bannerman v White [1861] 142 ER 685). uu Where the statement is accompanied by a recommendation that its truth be verified – the statement is more likely to be a mere representation (Ecay v Godfrey [1947] 80 LI L Rep 286). uu Where one party clearly relied upon the other, this is indicative that the statement was intended to be a term (Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] QB 801). Again, it is important to recognise, as Lord Moulton observed in Heilbut, Symons & Co v Buckleton [1913] AC 30, that none of these factors are decisive tests. The presence or absence of these factors is not conclusive of the intention of the parties: the intention of the parties is deduced from the totality of the evidence. The parol evidence rule If the parties have chosen to place their contract in a written document, courts have held, as a general rule, that they cannot provide extrinsic evidence to add to, vary or contradict the written document; the document is the sole source of the terms of the contract. This is known as ‘the parol evidence rule’ (see, e.g. Jacobs v Batavia & General Plantations Trust Ltd [1924] 2 Ch 329). While the rule is intended to promote certainty, it has the potential to produce injustice in some instances. Contract law 5 The terms of the contract To minimise these injustices a number of exceptions to the rule exist. First, where the written document was not intended to cover the whole of the agreement the rule does not apply: Allen v Pink [1838] 150 ER 1376. Second, parol evidence is admissible to prove terms or a custom which must be implied into the agreement. Third, parol evidence may be admitted to show that the contract is void by reason of a misrepresentation, mistake, fraud, or non est factum (see Chapters 8 and 9). Fourth, parol evidence may also be admitted to show that a contract has not yet come into operation or has ceased to operate. Fifth, parol evidence may be admitted to prove the existence of a collateral contract. The parol evidence rule is said to promote certainty (AIB Group plc v Martin [2001] UKHL 63 at [4]). Evidence to support the benefit of such certainty is provided by the fact that many commercial contracts incorporate an express clause to similar effect called ‘an entire obligation clause’. This is a contractual term which expressly provides that the written contract records the totality of their legally enforceable agreement. Such a provision is valuable in preventing parties from ‘threshing through the undergrowth [for] some …remark or statement (often long forgotten …) upon which to found a claim’ (Inntrepeneur Pub Co v East Crown Ltd [2000] 3 EGLR 31 per Lightman J). In Axa Sun Life Services v Campbell Martin [2011] EWCA Civ 549 the Court of Appeal applied this dictum emphasising that such clauses will help reduce litigation and associated costs. 5.1.2 Terms of collateral contracts We have thus far distinguished between contractual terms and representations on the basis that if the statement was a contractual term then it was a term of that particular contract. It is also possible that the statement is a term of a separate contract – a contract collateral to (i.e. running beside) the main contract. For example, it may be that I contract to sell you my antiquarian bookshop. I provide you with figures demonstrating past sales. This statement is not included in the contract of sale; however, it was made with contractual intent and it forms the basis of a collateral contract. If the figures are incorrect, if I have improperly warranted the past sales, this is actionable as a breach of the collateral contract. See Heilbut, Symons & Co v Buckleton [1913] AC 30 and Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] QB 801. Activity 5.1 Think of the circumstances in which a purchaser will rely upon a seller’s expertise as to the good being sold. In what situations will a purchaser rely upon a seller? Activity 5.2 Is it relevant to ask, as Lord Denning does in cases such as Dick Bentley Productions v Harold Smith (Motors) Ltd [1965] 1 WLR 623, whether the defendant was ‘innocent of fault’ as an aid to determining the existence of contractual intention? Does this shed any light on the way judges decide what is the ‘proper’ inference? Activity 5.3 Apply the relevant factors to determine whether the statement made by the private seller of a car to a private buyer that it is a ‘[Triumph] Herald convertible, white 1961’ would be classified as a term or a mere representation when it later transpires that the car is not a 1961 model? Activity 5.4 What is the ‘parol evidence rule’? Is it still important? If not, why not? Summary It is important to determine whether a statement or assurance is a term of the contract or a representation because this determines the remedy available to the injured party. If the statement is a term of the contract, or of a collateral contract, the injured party may bring an action for damages. If it is a representation, the injured party must establish that the statement is an actionable misrepresentation. page 73 page 74 University of London International Programmes Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 5 ‘The terms of the contract’. 5.2 The use of implied terms Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 9 ‘The sources of contractual terms’ – Section 9.8 ‘Implied terms’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 6 ‘Content of the contract and principles of interpretation’ – Section 4 ‘Implied terms’. We have, thus far, thought of contractual terms as express terms. I order a pair of roller skates from a local sports equipment shop. I stipulate that they are to be a size 42, have four in-line wheels and that the colour will be black. I agree to pay £99 for the skates. The shopkeeper stipulates that he will deliver them on Friday. All of the matters in this exchange amount to express terms – terms the parties have explicitly agreed upon. These express terms, however, do not necessarily form the entirety of the contract between the shopkeeper and myself. In certain circumstances, a court will imply terms into a contract. Thus, in the example above, the courts will use the Consumer Rights Act 2015 to imply a duty, as between a business and consumer to provide goods of a satisfactory quality (s.9(1)), only that the roller skates were fit for purpose. In this section we will consider the circumstances in which courts will imply duties and terms into a contract. In examining this area, it is important to bear in mind that courts are generally reluctant to imply terms into a contract. The courts generally consider their role to be that of an interpreter of contracts rather than a maker of them. The more frequently terms are implied into a contract, the greater the extent to which the court has created the contract rather than merely interpreted it. In Crossley v Faithful & Gould Holdings Ltd [2004] EWCA Civ 293 the Court of Appeal declined to find that there was an implied term within the contract of employment which provided that an employer ought to take reasonable care of an employee’s economic well-being. The introduction of such a term would be a major extension of the existing law and would place an intolerable burden upon employers. Dyson LJ observed that courts in cases involving implied terms ought not to ‘focus on the elusive concept of necessity’ but to ‘recognise that, to some extent at least, the existence and scope of standardised implied terms raise questions of reasonableness, fairness and the balancing of competing policy considerations’. These important comments were endorsed by Lady Hale in the Supreme Court in Geys v Societe Generale [2012] UKSC 63 at [56]. Courts will imply terms into contracts either by operation of the common law or by statute law. These situations include the following: uu where there is an established trade usage uu because of the relationship between the parties uu to give effect to an unexpressed intention of the parties uu by operation of statute. We will examine these in turn. 5.2.1 Implied terms in common law Trade usage The courts may imply terms into the contract where an established trade usage can be demonstrated. This is particularly common in commercial and mercantile contracts. Here, the standardised implied term functions as a kind of default rule. An example of Contract law 5 The terms of the contract such a situation would be that the vendors of a certain type of good always paid the broker’s commission with regard to the sale; absent a term to the contrary, courts will imply such a term into this type of contract. The nature of the relationship Similarly, some terms will be implied because of the nature of the relationship between the parties: they are ‘general default rules’ arising from ‘particular forms of contracts’ according to Lord Steyn in Equitable Life Assurance Society v Hyman [2002] 1 AC 408. Two relationships have been particularly productive here: landlord and tenant and employer and employee. In Liverpool City Council v Irwin [1976] AC 239 the House of Lords implied a duty to take reasonable care of the so called common parts (stairs, hallways and lifts, etc.) on the landlord (here a local authority) of premises with multiple occupants. Terms have been implied into contracts of employment to the effect that an employer should not: overwork its staff in a way that damages their health (Johnstone v Bloomsbury Health Authority [1992] QB 333); conduct business fraudulently (Malik v Bank of Credit and Commerce International SA (In Liquidation) [1997] 3 WLR 95); or go back on an earlier promise to provide a large ‘bonus pool’ (Attrill v Dresdner Kleinwort Ltd [2012] EWHC 1468) in a manner likely to destroy or seriously damage the relationship of confidence and trust between employer and employee. In this area the courts are sensitive to the point that the law of contract is generally understood to be about enforcing contracts which the parties, not the courts, have fashioned for them. To minimise any necessary usurpation of the parties’ general right to create their own contract, a narrowly framed contract term is more likely to be implied by law than an overly broad one. In Scally v Southern Health Board [1992] 1 AC 294 a term was implied that the employer was obliged to alert employees to a particular ‘trap’ in their pension scheme whereby, if they did not act promptly, they would fail to secure a large benefit. In contrast in Crossley v Faithful & Gould Holdings Ltd (2004) the Court of Appeal declined to impose a term on the basis of a more general duty on employers to look out for their employees’ financial well-being. The unexpressed intention of the parties and the ‘officious bystander’ The courts may imply terms into the contract to give effect to what appears to be the unexpressed intention of the parties. In some circumstances, the contract will not function unless the term is implied; the term is necessarily implied to give ‘business efficacy’ (i.e. effectiveness) to the contract. On this basis in The Moorcock [1889] 14 PD 64 a term was implied into a contract for the use of a tidal dock that the owner of the facility had taken reasonable steps to check that the river bottom was safe for a ship to settle on after the tide had gone out. Consequently, the ‘business efficacy’ test is sometimes also known as the Moorcock test. A different test was proposed in the much quoted judgment of MacKinnon LJ in Shirlaw v Southern Foundries (1926) Ltd [1939] 2 KB 206: Prima facie that which in any contract is left to be implied and need not be expressed is something so obvious that it goes without saying; so that, if, while the parties were making their bargain, an officious bystander were to suggest some express provision for it in their agreement, they would testily suppress him with a common ‘Oh, of course’. [1939] 2 KB 206, 227. In an important judgment in Attorney General of Belize v Belize Telecom Ltd [2009] 1 WLR 1988, Lord Hoffmann sought to re-state the law relating to the implication of terms at common law. The implication of a term is an exercise in the construction of the contract as a whole. Previous cases establish not a series of independent tests to be met ‘but rather …a collection of different ways in which judges have tried to express the central idea that the proposed implied term must spell out what the contract actually means’. A term may be implied to give effect to the overall purpose of the document as understood by a reasonable person. However, that reasonableness alone is not a sufficient basis for implication was reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in Marks and Spencer plc v BNP Paribas Securities Services Trust Company [2015] UKSC 72. page 75 page 76 University of London International Programmes It is difficult to assess the impact of Lord Hoffmann’s restatement of the proper way to approach the issue of the implication of terms into contracts. It is perhaps inconsistent with the longstanding usage of the ‘officious bystander’ test in commercial contracts. Despite the broader approach urged it is unlikely to change the courts’ general refusal to interfere with detailed written documents that express a negotiated compromise between commercial parties with opposed objectives (Philips Electronique Grand Public SA v British Sky Broadcasting Ltd [1995] EMLR 472 and Mediterranean Salvage & Towage Ltd v Seamar Trading & Commerce Inc (The Reborn) [2009] EWCA Civ 531). In Marks and Spencer plc v BNP Paribas Securities Services Trust Company [2015] UKSC 72 the Supreme Court emphasised the correctness of the traditional restrictive approach to the implication of terms and so rejected any expansive interpretation of Lord Hoffmann’s comments. Lord Neuberger said: I accept that both (i) construing the words which the parties have used in their contract and (ii) implying terms into the contract, involve determining the scope and meaning of the contract. However, Lord Hoffmann’s analysis in the Belize Telecom case could obscure the fact that construing the words used and implying additional words are different processes governed by different rules. The situation is different where the written document is less expansive. In Yam Seng Pte Ltd v International Trade Corp [2013] EWHC 111 Leggatt J said that terms will be more easily implied into an agreement which itself is ‘skeletal’, arguing for the implication into all commercial agreements of a general duty to perform the contract in good faith. Predictably, the general disinclination to interfere with commercial dealings has been re-asserted and the broader general duty suggested by Leggatt J has been denied (Mid Essex Hospital Services NHS Trust v Compass Group UK and Ireland Ltd [2013] EWCA Civ 200 and MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company SA v Cottonex Anstalt [2016] EWCA Civ 789) or at least limited to long term contracts where there is considerable interdependence of the parties, called ‘relational contracts’ (Hamsard 3147 Ltd (t/a Mini Mode Childrenswear) v Boots UK Ltd [2013] EWHC 3251). Activity 5.5 Why did the House of Lords reject the ‘variety of implication’ that the law implies a term on the basis that it is reasonable to do so, favoured by Lord Denning MR? (The rejection is made by Lord Wilberforce in Liverpool City Council v Irwin (1977).) Activity 5.6 A contracts with B to assemble bicycles to B’s specifications. One of these specifications is that the bicycles will be fitted with a unique gear system. B manufactures these gear systems. Is there an implied term that B will supply A with this gear system in sufficient quantities to manufacture the requisite number of bicycles? Further reading ¢¢ Peden, E. ‘Policy concerns behind the implication of terms in law’ (2001) 117 LQR 459. 5.2.2 Terms implied by operation of statute The above three instances are circumstances where the term is implied by operation of the common law. Terms may also be implied, or equivalent duties imposed, in contracts by operation of legislation. In these instances, the terms are implied or duties imposed because Parliament legislates that the term will be in the contract. To a certain extent, this is to provide a standardisation of terms in certain kinds of contracts. It also provides a measure of protection for certain categories of parties, such as consumers. Prior to the passing of the Consumer Rights Act 2015 the key legislative provisions were applicable (though to different extents) to contracts between two businesses (so called B2B contracts) and also to contracts between businesses and consumers (so called B2C contracts). Since the Consumer Rights Act 2015 came into force in October 2015 B2B and B2C contracts will be subject to separate statutory regimes. Contract law 5 The terms of the contract B2B contracts As between a business and another business the earlier legislation of Sale of Goods Act 1979 (SGA) and Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982 (SGSA) will apply. In a contract for the sale of goods the following terms are implied: uu SGA s.12 – an implied term that the seller has the right to sell the goods. uu SGA s.13 – an implied term that the goods will conform to any description given. In a number of older cases the courts required the strict and exact fulfilment of any description used by the seller. Although ‘microscopic variations’ would be disregarded it was said that ‘A ton does not mean about a ton’ (Arcos v EA Ronaasen & Son [1933] AC 470). Subsequent cases suggest that words of description fall within s.3. Rather the section only applies if they constitute ‘a substantial ingredient of the “identity” of the thing sold’ Reardon Smith Line Ltd v Hansen-Tangen (The Diana Prosperity) [1976] 1 WLR 989. uu SGA s.14(2) – an implied term that the goods are of satisfactory quality. According to s.14(2A) and 14(2B) in assessing whether the goods are of satisfactory quality the court should take account of any description use which might serve to increase (e.g. ‘first class’) or decrease (e.g. ‘seconds’) the standard expected. The courts are also instructed to take account of ‘the price (if relevant)’. The word ‘if’ was possibly used to prevent a seller arguing that sale goods could be of a lower quality than non-sale goods. Goods are required to be fit for all the purposes for which goods of that kind are commonly supplied and account may be taken of the goods’ appearance and finish as well as their safety and durability. uu SGA s.14(3) – an implied term that the goods are reasonably fit for any particular purpose which the buyer made known to the seller. If clothing was bought and the buyer asked and was assured that it could be washed in a washing machine then a term to that effect will be implied. IMPORTANT The terms implied by s.14(2) and 14(3) (and also that implied by the Sale of Goods and Services Act 1982 s.13 below) only arise where the sale is in the course of a business. A sale may still be made in the course of a business where it is an infrequent dealing such as the sale of a fishing boat by a fisherman in Stevenson v Rogers [1999] QB 1028. Where goods are supplied in the course of a business the requirement that they be of satisfactory quality does not extend to defects brought to the buyer’s attention, or more importantly, defects which a pre-purchase inspection that was undertaken should have revealed (Bramhill v Edwards [2004] EWCA Civ 403). In a contract for the provision of a service the following term is implied: uu SGSA s.13 – an implied term that any service provider will carry out the service with reasonable care and skill. This term will only be implied where the service is provided in the course of a business. B2C Contracts The CRA 2015 imposes duties upon traders contracting with consumers that correspond to the implied terms described above for B2B contracts. The CRA 2015 uses the language of duties rather than implied terms but the substance of the obligation should be the same. The duties are: uu CRA s.11(1) – a duty on the trader to supply goods that conform to any description given. uu CRA s.9(1) – a duty on the trader to supply goods of satisfactory quality. Satisfactory quality is to be assessed by reference to a non-exhaustive list of factors set out in s.9(2)-(7). uu CRA s.10(1) – a duty to supply goods that are reasonably fit for any purpose made known to the trader by the consumer. uu CRA s.49(1) – a duty on the trader to perform any service with reasonable care and skill. The CRA itself limits the extent to which these duties can be excluded. This is discussed further in Section 6.2.1. page 77 page 78 University of London International Programmes Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, Chapter 23, for a complete and detailed overview of the CRA 2015. Self-assessment questions 1. Place the circumstances in which terms will be implied into a contract into two categories – first, those implied by law and secondly, those implied by fact. If necessary, refer to McKendrick, Chapter 9, Section 9.8 ‘Implied terms’. 2. On which party is the onus of proving the existence of an implied term? 3. Does the implication of terms into a contract resolve problems or create them? Summary Courts will, in certain circumstances, imply terms into a contract. The terms will be implied either by operation of the common law or by statute. Once the terms are implied, they are effective as a contractual term. 5.3 The classification of terms into minor undertakings and major undertakings Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 10 ‘The classification of contractual terms’. ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 19 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 19.6 ‘The right to terminate performance of the contract’ to Section 19.8 ‘The right of election’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 8 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 3 ‘Identifying repudiatory breach and the classification of terms’. We began this chapter by examining how statements and exchanges become terms of contracts. We conclude by examining how these terms are classified. In general, terms will be classified into minor and major undertakings (or obligations). To understand the discussion of the classification of contractual terms it is necessary to start with the remedies for breach. A contractual term is a ‘primary’ obligation. Every breach of a ‘primary’ obligation gives rise to a ‘secondary’ obligation to pay damages for the loss caused. In some cases this is the only remedy, but in others there is the further remedy of ‘terminating’ (ending or rescinding) the contract. That is to say, some breaches of contract provide the injured party with an option. He or she can either (a) terminate the contract and claim damages or (b) affirm the contract (accept the breach and insist on continued performance of the contract) and claim damages. The classification of terms is important because the injured party is only given this option when the term breached is a condition or there is a sufficiently serious breach of an innominate term (see Section 5.3.2 below). The injured party is not given the right to terminate the contract for breach of a term that is a warranty. We will return to these concepts in Chapter 14 where we examine the performance and breach of contracts. Before examining what the terms ‘condition’, ‘innominate term’ and ‘warranty’ mean, it is important to consider the different concepts of rescission. The words ‘rescind’ and ‘rescission’ have different meanings in different contexts. Rescinding or terminating for breach means that the injured party is entitled, if he so wishes, to treat the contract as discharged (i.e. brought to an end) and to refuse to make further performance of his own obligations or to receive further performance of the other party’s obligations. This is different from rescission (rescinding) for misrepresentation, which, when effected, means that the contract is cancelled from the very beginning. For this reason in this context termination is preferred as a term over rescission. Termination for breach is a drastic remedy. The severity of the situation may be exacerbated when an ‘injured’ party uses his right to rescind simply to escape from Contract law 5 The terms of the contract what has become a bad bargain. For example, a person who has arranged delivery of coal at a time when coal is scarce and prices are consequently high may later find that coal has become more plentiful and prices are lower. Such a person may seek to use a technical breach of contract (that is to say, a breach which does not really harm him) to end the contract. 5.3.1 The distinction between conditions and warranties For this reason it is most important to define the breaches which will give the injured party the right to refuse further performance. A solution to this was found in the 19th century by classifying the terms of a contract into the two following types. uu Conditions: breach of which gave the right to refuse further performance. uu Warranties: for breach of which damages were the only remedy. Note that a party rescinding for breach need not show that the breach of condition has actually caused any loss. See Bowes v Shand [1877] 2 App Cas 455 and Re Moore and Landauer [1921] 2 KB 519. This classification into conditions and warranties was extensively used by the drafters of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 (and previously 1893), where the principle is that the most important terms are conditions and the less important ones are warranties. (‘Condition’ is another word used in several senses: the present sense is highly artificial, but more important for our purposes than the natural meaning of a ‘suspensive’ condition.) At common law, however, it is clear that the ultimate test is the parties’ intention: if the intention is clearly expressed, a term will be a condition, however unimportant it is. This intention may be expressed in different ways. Where a term is called a condition this is highly persuasive, but not always conclusive evidence, to infer that the parties’ intention was that it should be a condition (L Schuler v Wickman Machine Tool Sales [1974] AC 235). The next most compelling means of expressing such an intention is if the parties use words that indicate the importance of a clause. Where a contract expressly provides that ‘time is of the essence’ this has been held to be a sufficient demonstration of intention to render prompt performance a condition of the contract (Lombard North Central plc v Butterworth [1987] QB 527). However if the intention is not clearly expressed, the court will again have to draw the ‘proper inference’. See Behn v Burness [1868] 122 ER 281; Bettini v Gye [1876] 1 QBD 183 and Poussard v Spiers [1876] 1 QBD 410. 5.3.2 Innominate terms It was implicit in this 19th-century approach that a breach of a contractual term that was not classified as a condition gave no right to refuse further performance, however serious the consequences for the injured party. This assumption was rejected in the Hong Kong Fir case in 1962 (Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [1962] 1 All ER 474), where the Court of Appeal recognised a new category of terms that are neither conditions nor warranties. Such ‘unclassified’ terms are usually referred to as ‘innominate’ or ‘intermediate’ terms. For breach of such terms the court will decide whether the injured party has the right to rescind in the light of the seriousness of the consequences of the breach. See also Cehave v Bremer Handels GmbH (The Hansa Nord) [1976] QB 44, where this analysis was applied to a term in a contract for sale of goods which did not fall within the statutory ‘conditions’. The Hong Kong Fir approach may make it less easy for a contract to be rescinded for breach on a mere technicality but it inevitably introduces greater uncertainty into the law. In some cases the need for certainty must prevail. See Maredelanto Compania Naviera SA v Bergbau-Handel GmbH (The Mihalis Angelos) [1970] 2 WLR 907; Bunge v Tradax Export SA [1981] 1 WLR 711; Cie Commerciale Sucres et Denrees v C Czarnikow Ltd (The Naxos) [1990] 1 WLR 1337 and Barber v NWS Bank [1996] 1 WLR 641. But contrast page 79 page 80 University of London International Programmes Torvald Klaveness v Arni Maritime Corp (The Gregos) [1994] 1 WLR 1465 where the House of Lords held that the obligation to re-deliver a time-chartered ship on the due date was probably not a condition. It is important to note that the Hong Kong Fir case has not changed the law on the question of what is a condition. It does, however, seem to have had a ‘knock-on’ effect on the application of that law by the courts. See Reardon Smith v Hansen-Tangen [1976] 1 WLR 989 where words identifying the yard where the ship was to be built were held not part of the ‘description’ so as to amount to a condition of the charter party. A similar reluctance to permit rescission on a technicality may have influenced the approach of the House of Lords to the construction of the express condition in L Schuler v Wickman Machine Tool Sales [1974] and the express termination clause in Rice (T/A Garden Guardian) v Great Yarmouth BC [2003] TCLR 1. Contrast the more traditional approach in the following cases. uu Lombard North Central v Butterworth [1987] QB 527: punctual payment was made a condition. Note that the hirer was also liable in damages for the entire loss caused to the plaintiffs by the ‘rescission’ of the contract. uu Union Eagle v Golden Achievement [1997] 2 All ER 215: a 10-minute delay was too much. Time was of the essence: as the time for performance had passed, so too had the right to performance. Activity 5.7 Why was the unseaworthiness of a chartered ship (in Hong Kong Fir) considered less important than the owner’s estimate of when she would be ready to load the charterer’s cargo? Activity 5.8 If the time charterer is late in redelivering the ship, what are the practical consequences for the owner? Activity 5.9 What more could Schuler (in L Schuler v Wickman Machine Tool Sales) have done to achieve the effect of making the visits genuinely a condition of the contract? Activity 5.10 Compare the decision in Schuler with that in Lombard. How are they different? Summary Contractual terms are categorised as conditions, warranties or innominate (or intermediate) terms. The categorisation is important because it determines whether or not the wronged party is entitled to terminate the contract upon breach. Only the breach of a condition or a sufficiently serious innominate term justifies the termination of the contract. The principal difficulty posed with this area of the law is one of certainty: it is often hard to ascertain whether or not there has been a sufficiently serious breach of an innominate term as to justify termination. Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, G. Some landmarks of twentieth century contract law. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002) [ISBN 9780199255757] Chapter 3 ‘Types of contractual terms’. Examination advice The matters considered in this chapter are unlikely to appear as separate issues in examination questions. However, the material considered in this chapter is very important and virtually all examination papers on the law of contract contain questions on the incorporation of terms in a contract or the classification of terms and the consequences of breaching different terms. Contract law 5 The terms of the contract It is of prime importance in any situation to establish what the terms of a contract are. Without establishing the terms of the contract it is impossible to ascertain what the parties are obliged to do and whether or not they have performed the contract. Consequently, you will find that a careful study of this area of the law is important. A review of past examination papers indicates that the examiners have frequently combined an issue involving the terms of the contract with other issues. While this advice is not exhaustive, these other areas have often been the regulation of terms, issues involving the performance and breach of the contract and the issue of damages. The scope for combining an issue of terms with other issues is very wide. Because of this breadth, three different questions involving terms have been provided below. You will not, at this point, be able to answer Question 2 (below) fully: they are provided simply to show you how an issue involving terms can be combined with other issues. You should return to these questions when you have completed these other areas and review the questions again. In attempting a problem question, you should carefully study the facts provided and determine what terms are incorporated into a contract. If the statement is not a term of the contract, is it possible that it may be a misrepresentation? In examining the terms of a contract, you should bear in mind the possibility that terms might be implied into the contract – if this is the case, what effect do these terms have? Lastly, with regard to the classification of terms, you will need to consider the importance of the term. A review of past examination papers reveals that essay questions have often been a variation on the theme, ‘Why is certainty so important in commercial contracts?’. It is most important to have thought, before the examination, about such issues as whether the essentially flexible concept of innominate terms does not introduce an undesirable degree of uncertainty into the law. Sample examination questions Question 1 Alban is a surveyor. Four months ago he bought a nine-month-old ‘Landmaster’ car from Brenda’s Garage Ltd for use in his practice. He paid £12,500 for the car and was given a written guarantee in the following terms. ‘Brenda’s Garage Ltd guarantees that, for three months from the date of purchase, it will put right free of charge any defects in the vehicle which cannot be discovered on proper examination at the time of purchase. Thereafter all work and materials will be charged to the customer.’ The sales manager recommended to Alban that he should take out the ‘special extended warranty’ under which, for payment of £350, the car would have been guaranteed in respect of all defects for a further two years, but Alban declined. Last week the engine and gearbox seized up. The repairs will cost £2,000. Advise Alban. Would your answer differ if he also used the car to take his wife shopping on Saturdays? Question 2 ‘The present legal rules allowing an innocent party to bring a contract to an end for breach are unclear and in need of reform. Fortunately, the rules concerning measure of damages for breach are clear.’ Discuss. page 81 page 82 University of London International Programmes Advice on answering the questions Question 1 You should begin this problem by considering the facts given. Note that at the end of the problem, a variant on the facts is provided. The variant involves the personal use of the car – this is likely to give rise to issues about the legal treatment of consumers by statute law. The first thing to establish is whether or not there has been a breach of contract when the engine and gearbox seized up. To establish this, it is necessary to determine what the terms of the contract are. An express term is that Brenda’s garage will put right any problem which occurs within three months. This term is of no use to Alban because his problem has occurred outside the three months. The issue then becomes, in the absence of any other express term, whether or not a term can be implied into the contract. This contract is for the sale of goods and is not a sale by a trader to a consumer. Therefore you must consider the Sale of Goods Act 1979 and not the Consumer Rights Act 2015. Section 14(2) provides that where the seller sells in the course of a business, ‘there is an implied term that the goods supplied under the contract are of satisfactory quality’. You need to consider whether or not satisfactory quality is established here (by applying ss.14(2A), (2B) and (2C) of the Act). You need to consider whether or not the statutorily implied term is negatived or varied by the express agreement between the parties. If this is a consumer sale (as per the variant), the statutorily implied terms are subject to the Consumer Rights Act 2015. If this is not a consumer contract, the statutorily implied term can be excluded to the extent that it is reasonable to do so. If this is not a consumer sale and the term is implied (and not negated by the presence of the express terms) then the buyer, Alban, cannot reject the goods where the breach of a condition implied by s.14 is so slight that it would be unreasonable to reject them (by reason of s.15A of the Sale of Goods Act). With regard to the variant to the question, you need to consider whether or not the use of the car to take his wife to the market on Saturdays removes the contract from one made in the course of a business. Question 2 This question calls for an examination of when an innocent party can end a contract and the rules for ascertaining the measure of damages (a topic you have yet to consider in this guide). The question invites a comparison between the apparent lack of clarity an innocent party faces in knowing when he or she is able to end the contract (the warranty/condition approach or the Hong Kong Fir approach) and the clarity in the rules surrounding the calculation of damages. The principal challenge in answering this question lies in clearly synthesising and analysing a wealth of case law. You will need to examine and compare two areas of law (terms and damages). A good answer to this question provides some analysis as to why there is a lack of clarity in ascertaining when a contract can be terminated – you could, for example, discuss whether this apparent lack of clarity provides courts with the flexibility to reach a just result by preventing parties from terminating a contract for what is actually a trivial breach. With regard to the area of damages, it is by no means certain what an appropriate measure of damages will be in many cases. As you will see when you reach this topic, recent case law has, in some ways, rendered this issue more confusing. Contract law 5 The terms of the contract Quick quiz Question 1 Which of the following statements provides the most appropriate definition of an ‘innominate term’? Choose one answer. a. The major or main obligation in the contract where breach will give the right to refuse further performance. b. A more or less important obligation depending upon the effects of breach. c. A less important obligation where breach will only provide damages as the remedy. d. An obligation which the courts will read into the contract so as to support the intention of the parties. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Which of the following actions is most likely to be a suitable degree of notice to ensure that an exclusion clause could be relied upon by the party attempting to exclude liability? Choose one answer. a. A statement excluding liability for loss or theft of articles from a hotel room is placed on the wall of a hotel bedroom you have secured for the night. b. A statement excluding liability for accident or damage for the hire of a chair is on the back of a ticket handed over to you at the point of hire. c. A statement excluding liability is found on a written sale note sent after an oral contract has been concluded with a company that you have previously contracted with. d. A statement excluding liability for loss or damage to your car is found on the back of the ticket you obtain from the automated car parking machine when you enter the car park. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following is not considered significant by courts in establishing whether or not a statement is a term of the contract? a. Whether the maker of the statement accepted responsibility for the soundness of the statement. b. Whether or not the parties to the contract have written the statement down after it was discussed. c. Whether or not the parties attached importance to the statement. d. Whether or not one party clearly relied upon the other. e. Don’t know. Question 4 In The Moorcock (1889), Bowen LJ implied a term into the contract between the parties because: a. The relevant legislation required him to do so. b. As a matter of public policy concerning the use of the jetty it was important to imply the term. page 83 page 84 University of London International Programmes c. Because of the presumed intention of the parties. d. Because of the presumed intention of the parties and because it was necessary in the circumstances. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Which of the following statements is false? a. The origins of innominate terms are doubtful. b. Innominate terms are substantially the same as intermediate terms. c. The identification of intermediate terms by the Court of Appeal in Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd (1962) was an important factor in introducing a degree of certainty to the rights of an injured party. d. Whether or not an injured party can terminate a contract for the breach of an intermediate term depends upon the seriousness of the particular breach. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. When does a statement form a part of the contract (and when does it not)? 2. What are the effects of a statement which is a term – and a statement which is not a term – of the contract? 3. Why and when will courts imply terms into contracts? 4. What are the limits upon courts in implying terms into contracts? 5. What are the different categories of contractual undertakings (terms)? 6. How is it determined within which category a particular term should be placed? 7. What are the consequences attendant upon a breach of each of these different categories of undertakings? Part II Content of a contract and regulation of terms 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86 6.1 Indirect common law controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87 6.2 Statutory control . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103 page 86 University of London International Programmes Introduction The law of contract is distinguished from other areas of private law because it is about the enforcement of consensual agreements. In theory the parties to a contract are free to choose their own contractual terms and are then bound by these terms. However, such a ‘pure’ theory of voluntarily assumed obligations must immediately be qualified. It became clear by the late 19th century that many individuals were bound to terms with which they had no practical choice but to agree to or of which they had no actual notice. This was exacerbated by the rise of standard form contracts (i.e. contracts used by businesses which were not individually negotiated and the terms of which were rarely modified). Such contracts often offered on a ‘take it or leave it basis’ are a common part of day to day life. If you doubt it, when you next take a train try to ‘renegotiate’ the standard forms of carriage contract before buying your ticket! In the past, judges at common law had no means directly to control these clauses and practices to free individuals from such terms. Consequently, they relied upon indirect means of control. Courts went to great lengths to find a particularly onerous clause was not incorporated into the contract or that the clause, properly construed, did not cover the actual event which had occurred. Clauses whereby a contractor sought to exclude (so called ‘exclusion’ or ‘exemption’ clauses) were a particular source of concern, especially when a party sought to exclude liability for their own negligence or for a fundamental breach of contract. Exclusion (or exemption) and limitation clauses which seek either to exclude, or perhaps only to limit the liability of a party in breach of contract will be the main focus of this chapter. A short review of the direct control of exclusion clauses (hereafter to include limitation clauses unless separately discussed) is necessary now to understand the discussion in this chapter of the current law and to relate it to any textbooks you choose to read. In 1977 the Unfair Contracts Terms Act (UCTA 1977) was enacted. Despite the Act’s title it did not seek to regulate all unfair contract terms but rather focused upon exclusion clauses. When introduced, UCTA 1977 regulated contracts entered between two businesses (so called B2B contracts) as well as those between businesses and consumers (so called B2C contracts). As you would expect, businesses were subject to less constraint when dealing with other businesses than they were when contracting with consumers. In 1993 a European Directive on Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts (93/13 EEC) required all member states to enact a minimum level of consumer protection including but also extending beyond the control of exemption clauses, in furtherance of the European single market. The Directive’s transposition into domestic law was late and untidy. It was implemented in 1994 (and later again in 1999) by statutory instruments, the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations (respectively SI 1994/3159 and SI 1999/2083, hereafter ‘the Regulations’) that simply ‘copied out’ the originating Directive. This resulted in two parallel systems for the regulation of exclusion clauses in B2C contracts represented by UCTA 1977 and the Regulations, which the Law Commission criticised as ‘unacceptably confusing’. The Law Commission therefore drafted a single statute integrating both regimes. The criticism, but not the solution, was accepted by the government and a different approach was enacted in the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (CRA 2015). Most of the provisions of the CRA 2015 came into force on 1 October 2015. The CRA 2015 is the most significant reformulation and consolidation of the contractual protection of consumers that has been attempted in English law. It is therefore important to understand the purpose and structure of this new provision. In the accompanying explanatory notes it is stated that Part 2 of the Act: Consolidates the legislation governing unfair contract terms in relation to consumer contracts which currently is found in two separate pieces of legislation, into one place, removes anomalies and overlapping provisions in relation to consumer contracts The CRA 2015 avoids the previous overlapping regimes of UCTA 1977 and the Regulations applicable to B2C contracts by amending UCTA 1977 to make it applicable to B2B contracts only (CRA s.75 and Schedule 4). The CRA 2015 repeals the Regulations and enacts a new regime (ss.61–69 and Schedule 2) based upon them but containing Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract additions such as an expanded list (the so called ‘grey list’) of presumptively unfair terms and other clarifications. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces regulation of the terms of a contract to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: The basis upon which courts decide whether a clause has been incorporated into a contract. uu The approach taken by the courts when interpreting exclusion clauses. uu The concept and current relevance of ‘fundamental breach’. uu The background to and key provisions of the CRA 2015. uu The key provisions of the UCTA 1977 and their previous and current application. uu The relationship between the CRA 2015 and UCTA 1977. uu What kinds of clauses are invalidated by the CRA 2015 and UCTA 1977. uu What kinds of clauses are required to be ‘reasonable’ by the UCTA 1977 or fair under the CRA 2015. Activity 6.1 List the reasons why it might be undesirable to allow a party to exclude or limit liability for breach of contract. Are there any reasons why it might be desirable to allow such exclusion or limitation? SELF-ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS What statutory regime regulates the use of exclusion clauses in B2B contracts? What statutory regime regulates the use of unfair contract terms, including exclusion clauses, in B2C contracts? Having introduced the new regime of direct control exemption clauses we will begin a more detailed examination of the control of exemption clauses by looking at the different techniques of indirect control. 6.1 Indirect common law controls Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 11 ‘Exclusion clauses’ – Section 11.1 ‘Exclusion clauses: defence or definition?’ to Section 11.8 ‘Other common law controls upon exclusion clauses’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 7 ‘Exemption clauses and unfair contract terms’ – Section 1 ‘The general approach to exemption clauses’ to Section 3 ‘Construction: on its natural and ordinary meaning, the clause covered what happened’. In the past the courts did not have available to them the statutory schemes introduced above which would allow them to deny enforcement to harsh exclusion clauses. Instead they developed rules relating to the ‘incorporation’ (is the clause a part of the contract?) and ‘construction’ (does the clause cover the breach?) of clauses, as a means of controlling their effect while still ostensibly supporting the parties’ right to contract on whatever terms they chose, often summarised as the parties’ ‘freedom to contract’. At one stage the courts went further and developed a rule of law that prevented a party from relying upon an exclusion clause when that party was himself in ‘fundamental breach’ of contract (is the breach so serious that the exclusion clause cannot apply?). The potential of this approach was, however, severely limited by the House of Lords, as is explained in Section 6.1.3 below. It is important to note that the rules applied in this area are based on rules which potentially apply to all clauses within a contract: even though their most common use is in relation to exclusion and limitation clauses. For this reason, one of the leading page 87 page 88 University of London International Programmes modern cases on incorporation, Interfoto Picture Library v Stiletto Visual Programmes [1988] 2 WLR 615, deals with the question of whether a so called penalty, rather than an exclusion, clause was included in the terms of the parties’ contract. 6.1.1 Incorporation Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 9 ‘The sources of contractual terms’ – Section 9.3 ‘Bound by your signature?’ to Section 9.5 ‘Incorporation by a course of dealing’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 6 ‘Content of the contract and principles of interpretation’ – Section 2B ‘The effect of signature’ and Section 3 ‘Oral contracts: incorporation of written terms’. In order for an exclusion clause to have any effect it must be a term of the contract. Where the contract has been signed, as in L’Estrange v Graucob [1934] 2 KB 394, the party signing will be bound by the clause, even if it has not been read or understood, so long as the party seeking to rely upon the clause has not made any misrepresentation as to its effect (as in Curtis v Chemical Cleaning & Dyeing Co [1951] 1 KB 805). On this basis the inexperienced purchaser of an investment product was held bound by the contract he signed despite his reliance upon an earlier, and different, telephone description of the product (Peekay Intermark Ltd v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 386). However, many exclusion (and other onerous) clauses may be contained in unsigned documents or notices. Look for these if you are in a car park, hotel or are leaving something at a left luggage facility or dry cleaners. Such unsigned documents or notices may become incorporated into the contract upon the principles which were restated in the Interfoto case. Incorporation occurs when all of the following three conditions are satisfied. 1. Notice – The party seeking to rely upon the unsigned document or notice must take reasonable steps to bring it to the attention of the other party. The test of what is reasonable was first stated in Parker v South Eastern Railway Co [1877] 2 CPD 416 and is clearly a question of fact to be determined in the light of all the circumstances. It was held in Thompson v London, Midland and Scottish Railway Co [1930] 1 KB 41 that the clause itself does not have to be on the document put forward: it is sufficient that the document indicates the existence of the clause and where it can be consulted. A number of cases have made it clear that the more unusual or onerous the clause, the more that must be done to draw it to the other party’s attention. This was captured by Lord Denning who said that for some clauses he had seen to be valid they ‘would need to be printed in red ink on the face of the document with a big red hand pointing’ at them (J Spurling Ltd v Bradshaw [1956] 1 WLR 461 and later see Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking [1971] 1 QB 163). It does not only apply in the context of consumer contracts, as shown by Interfoto Picture Library v Stiletto Visual Programmes (1988) (though the clause in this case was not an exclusion clause) and AEG (UK) Ltd v Logic Resource Ltd [1996] CLC 265. 2. Timing – Any term which is to be part of the contract must be brought to the attention of the parties before or at the time of contracting. See Olley v Marlborough Court Hotel [1949] 1 KB 532 and Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking (1971). 3. Nature of the document – If the terms are in a written document then that document must be one which the party would reasonably believe to have contractual force. In Chapelton v Barry Urban DC [1940] 1 KB 532 the ticket containing the contractual notice was one used to prove payment. The court found that this was not generally believed to be contractual in nature. It is not merely because it was a receipt, as some receipts are contractual, it was the purpose of the receipt. Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract A different way in which a clause may be incorporated is through a ‘course of dealing’. If the parties have dealt with each other in the past, and an exclusion clause has been used, this may in itself lead to a presumption that the clause will be incorporated in any new contract, even if on this occasion reasonable notice of it has not been given. The course of dealing in the past must however be both regular and consistent. In Kendall (Henry) & Sons v Lillico (William) & Sons Ltd [1969] 2 AC 31 it was held that 100 dealings over three years were sufficiently recurrent to be ‘regular’ but in Hollier v Rambler Motors (AMC) Ltd [1972] 2 QB 71 that three or four dealings over five years were not. In McCutcheon v MacBrayne [1964] 1 WLR 125 there were regular dealings, but the document containing the exclusion clause was not always used: it was held that the clause had not been incorporated. These requirements may be applied less strictly where both parties are commercial entities (i.e. it is a B2B contract (British Crane Hire Corp Ltd v Ipswich Plant Hire Ltd [1975] QB 303)). Activity 6.2 Marika, a Polish woman who understands very little English, buys a ticket for entry to Upton Castle (a theme park). The ticket states on it that no liability is accepted for the loss of, or damage to, property belonging to entrants. Will this clause be regarded as being incorporated into Marika’s contract? Activity 6.3 Angela takes her car for repair at Magna Garages. She is asked to sign a contract which states that Magna ‘accept no liability for minor damage to the bodywork of vehicles left for repair, howsoever caused’. When she queries this, she is told, incorrectly, by an employee of Magna, that it only applies to damage by third parties while the car is parked in Magna’s car park. Angela signs the contract. Is Angela bound by the clause? Activity 6.4 David has used a particular supermarket car park for his monthly shop since moving to the area two years ago. At the entrance there is a large noticeboard which warns that ‘All cars are parked at the owner’s risk’. This is repeated on the ticket David purchases after entering the car park. On the last occasion David visited the car park it was windy and the notice had been blown down. While he was shopping, the supermarket’s poorly maintained advertisement hoarding fell on David’s car. Is this event a part of any contract David has entered with the supermarket? Would the answer be different if David was delivering supplies from his farm for sale in the supermarket? 6.1.2 Construction Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 9 ‘The sources of contractual terms’ – Section 9.4 ‘Incorporation of written terms’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 7 ‘Exemption clauses and unfair contract terms’ – Section 3 ‘Construction: on its natural and ordinary meaning, the clause covered what happened’. If a particular clause is found, on the principles outlined above, to be a part of the contract, it must then be decided whether, on its true construction, the clause covers the particular breach which has occurred. The courts have traditionally been strict in this area and interpret any ambiguity against (contra) the person trying to rely on the clause (the proferens); hence the principle is sometimes called the contra proferentem rule. In Andrews v Singer [1934] 1 KB 17, for example, a clause excluding liability in relation to implied terms was ruled ineffective to exclude liability for breach of an express term. page 89 page 90 University of London International Programmes Unfortunately the contra proferentem rule is easier to state than it is sometimes to apply. When studying its application in the following paragraphs you should remember the following points. uu That though its application may appear complex the underlying principle is simple (i.e. that any ambiguity in an exclusion clause is to be interpreted against the person seeking to rely upon it). uu There is an increasing tendency to look at the issue of contractual interpretation more generally. In other words, the construction of exclusion clauses must be related to the approach to the interpretation of all contractual provisions which was discussed in Chapter 5. uu Consumers are now protected by dedicated legislative provisions, chiefly the CRA 2015. Courts have indicated that since the precursors of this latest protection were introduced the need to adopt ‘strained’ constructions of clauses in order to limit their scope is reduced. See, for example, the comments of Lord Wilberforce in Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd [1980] AC 827 at 843. uu Courts have suggested that a more relaxed view can be taken of clauses which merely limit liability, as opposed to excluding it altogether (see Ailsa Craig Fishing Co Ltd v Malvern Fishing Co Ltd [1983] 1 WLR 964). Such a view may cause difficulties in application because a limitation of liability to a very modest amount is in effect almost indistinguishable from a full exclusion of liability and so it has not been followed in Australia – see Darlington Futures Ltd v Delco Australia Pty Ltd [1987] 161 CLR 500. A particular problem arises where a contractor seeks to exclude liability in respect of his own negligence. In Canada Steamship Lines Ltd v The King [1952] AC 192 Lord Morton stated a number of principles to guide the process of interpretation in such cases: uu if the clause contains express language exempting a person from the consequence of the negligence, effect must be given to it uu if there is no express reference to such negligence, the court must consider whether the words used are wide enough, in their ordinary meaning, to cover it uu if the words used are wide enough, the court must then consider whether liability may be based on some ground other than negligence; if so, this will prevent reliance on the clause in relation to negligence. An example of the application of the second and third rules was White v John Warwick [1953] 1 WLR 1285. In a contract for the hire of a bicycle, a clause exempting the owners from liability for personal injuries was held to cover only breach of strict contractual liability as to the condition of the bicycle, and not injuries resulting from negligence in the fitting of the saddle. The usual implication of the rules were subverted (e.g. in Hollier v Rambler Motors (1972) it was said, obiter dicta, that where the only possible liability was liability for negligence an exclusion clause was ineffective to exempt such liability because it could ‘be given adequate content by construing [it] as a warning’ (i.e. that there would be no liability in the absence of negligence)). The tendency to subvert the approach taken in Canada Steamship has increased to the extent that it is not at all clear now what weight, if any, must be given to the Canada Steamship rules. In Australia, Lord Morton’s guidance has been expressly discarded; in England and Wales the process has been more subtle. For while ‘lip service’ is still given to his words (e.g. EE Caledonia Ltd v Orbit Valve Co Europe plc [1994] 1 WLR 1515) the House of Lords qualified their application in HIH Casualty and General Insurance Ltd v Chase Manhattan Bank [2003] UKHL 6 (see also Greenwich Millennium Village v Essex Services Group [2014] 1 WLR 3517) by emphasising the overriding importance in giving effect to the intention of the parties. The clear implication of this is that where there is a conflict between that intention and the result indicated by Lord Morton’s approach, the former should prevail. Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract 6.1.3 Fundamental breach Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 11 ‘Exclusion clauses’ – Section 11.7 ‘Fundamental breach’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 7 ‘Exemption clauses and unfair contract terms’ – Section 3E ‘Fundamental breach’. At one time the courts, and in particular the Court of Appeal, developed a rule of law by which it was held that an exclusion clause could never be effective against a particularly serious breach of contract – a ‘fundamental’ breach. A fundamental breach could be one where: the breach relates to a particular obligation which is central to the contract (Karsales (Harrow) Ltd v Wallis [1956] 1 WLR 936), the consequences of the breach are exceptionally serious (Harbutt Plasticine Ltd v Wayne Tank and Pump Co Ltd [1970] 1 QB 447) or a deliberate refusal to perform obligations under the contract (Sze Hai Tong Bank Ltd v Rambler Cycle Co Ltd [1959] AC 576). This approach to fundamental breaches was reviewed by the House of Lords in Suisse Atlantique Société d’Armament Maritime SA v Rotterdamsche Kolen Centrale NV [1967] 1 AC 361 and Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd [1980] AC 827. The House rejected the Court of Appeal’s assertion that there was a rule of law in this area preventing reliance on an exclusion clause following a fundamental breach. For some time it was thought that the doctrine of fundamental breach survived, not as a rule of law, but rather as a presumption against any exclusion clause being interpreted to cover a fundamental breach of contract. However, this has now explicitly been denied (AstraZeneca UK Ltd v Albemarle International Corp [2011] 1 All ER (Comm) 510). Rather, the question was one of construction. Does the clause cover the breach which occurred? Although it may be difficult to convince a court that an exclusion clause was intended to cover a breach which has deprived the other side of all benefit, ‘… but, if it does, it is no longer permissible at common law to reject or circumvent the clause by treating it as inapplicable to “a fundamental breach”’ (Neill LJ in Edmund Murray Ltd v BSP International Foundations Ltd [1992] 33 Con LR 1). It is therefore now an overstatement even to say that there is a ‘presumption’ against a clause. Activity 6.5 Read the case of Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd (1980). a. What type of fundamental breach was involved in this case? b. Why did the House of Lords think that it may well have been the parties’ intention that Securicor would have a very minimal level of liability under the contract? The approach adopted in Photo Production v Securicor may be justified by the fact that there are now statutory protections for consumers in relation to very broad exclusion clauses and that commercial contracts may appropriately be left to be governed by the principle of ‘freedom of contract’. The approach is therefore most appropriate where the parties are businesses contracting on equal terms. The effect of the Consumer Rights Act 2015 is that in all consumer contracts an exclusion clause which attempts to exclude liability for a fundamental breach will either be automatically void or subject to a test of ‘fairness’. Self-assessment questions 1. What is the effect of signing a contract? 2. What conditions must be fulfilled before an unsigned document or notice may be said to be incorporated into a contract? 3. What is the relevance of prior contracts entered between the parties? How can an unwritten clause be incorporated into a contract ‘in the course of dealing’? 4. What is the contra proferentem rule? 5. What is the present status of the so called doctrine of ‘fundamental breach’? page 91 page 92 University of London International Programmes Summary The common law controls the use of exclusion clauses by means of the rules of incorporation and construction. The rules relating to incorporation require close attention to be given to when the clause was put forward and the notice that was given of it. The rule of construction is based around the contra proferentem rule and according to a traditional approach is applied more strictly where the defendant alleges that liability for negligence has been excluded. More recently the courts have declined to apply this approach so strictly. Where there is a fundamental breach, an exclusion clause does not automatically cease to apply but if the parties use very clear language to express their intention that the protection of an exclusion clause should extend to such a breach that intention will now be respected (subject to the statutory controls examined below). Further reading ¢¢ Chen-Wishart, Chapter 10 ‘Identifying and interpreting contractual terms’, Section 10.6 ‘Interpretation of exemption clauses’. 6.2 Statutory control Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 11 ‘Exclusion clauses’ – Section 11.9 ‘The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977’ to Section 11.16 ‘Conclusion’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 7 ‘Exemption clauses and unfair contract terms’ – Section 4 ‘Clause in a B2B contract must not be rendered unenforceable by the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977’. The statutory controls examined in this section only become relevant if it is first established that the exclusion clause is a term of the contract (by signature, incorporation or course of dealing) and, properly construed, it would otherwise operate to protect the party in breach from liability. For further guidance on how to answer questions involving exclusion clauses see the concluding section of this chapter. The Introduction above should be re-read at this point. It contains an overview of recent statutory developments, particularly the CRA 2015. From this section you will have learned that the regulation of contractual exclusion clauses is effected differently depending upon whether the clause is contained in a contract between a business and a consumer or a contract between two businesses. To repeat this fundamental point: Business to consumer (B2C) If the contract is between a business and a consumer it will be necessary to look at the CRA 2015. Business to business (B2B) If the contract is between two businesses then the relevant legislation is the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (UCTA 1977). 6.2.1 The Consumer Rights Act 2015 Most of the provisions of the CRA 2015 came into force in October 2015. The background to these provisions in a European Directive and two sets of implementing Regulations (the latter repealed by the CRA 2015) have been described in Chapter 1, Section 1.4.2. The CRA 2015 has three parts: uu Part 1 Goods, Services and Digital Content – This part simplifies and clarifies the law over consumer rights arising from the purchase of goods, services and digital content. Existing legislation (e.g. the Sale of Goods Act 1979 and the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982) is amended or repealed and new rights are created by the CRA 2015 to apply to all B2C contracts. Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract uu Part 2 Unfair Protection – This part contains provisions relating to unfair terms which reflect recommendations made by the Law Commission and Scottish Law Commission. The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (UCTA 1977) is repealed so far as it affected B2C contracts. A single regime is enacted to regulate unfair terms which is based on, but has a wider application than, the repealed 1999 Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations (UTCCR 1999). uu Part 3 Enforcement/New Civil Remedies – This part covers the enforcement powers of public enforcers as well as the reform of consumer collective actions for anticompetitive behaviour. The changes effected by Part 1 in regard to the statutory implied terms have been examined in Chapter 5. The changes introduced by Part 2 will now be examined. The core provision of Part 2 is s.62(1) which provides that: ‘An unfair term of a consumer contract is not binding on the consumer’. This simple statement begs a number of questions. What is a consumer contract? A consumer contract is one entered between a ‘trader’ and a ‘consumer’ (CRA 2015, s.61(1)). A trader is defined as a ‘person acting for purposes relating to that person’s trade, business, craft or profession…’ (s.2(1), made applicable by s.76(2)). A ‘business’ expressly includes any government department, local or public authority (s.2(7)). A ‘consumer’ is defined as the converse of a trader (i.e. ‘an individual acting for purposes that are wholly or mainly outside the individual’s trade, business, craft or profession’ (s.2(3), made applicable by s.76(2)). The reference to an ‘individual’ means that a company cannot now be considered a consumer. The definition of a consumer has been extended to cover someone who is ‘mainly’ acting outside their ‘trade, business …’, etc. This will affect the level of protection offered to persons who purchase goods for mixed purposes. For example, if a car is purchased primarily for private use but is nonetheless sometimes used for business purposes, the contract will still be subject to Part 2 of the CRA 2015. The European Directive (93/13 EEC) and the now repealed UTCCR (SIs 1994/3159 and 1999/2083) stated that a term could only be set aside as unfair where that term was not ‘individually negotiated’. A term drafted in advance in circumstances where the consumer was unable to influence its substance was not regarded as individually negotiated. It is of potential significance that this pre-condition is not simply reproduced in the CRA 2015. Following the CRA 2015 a consumer may challenge a clause as unfair even though it was individually negotiated. The change effected to the law may however be small as the fact of individual negotiation, though no longer an absolute bar to challenge, may be one of many factors relied upon by the trader as evidence that the term was not unfair. What makes a contract term ‘unfair’? The CRA s.62(4) defines an unfair term as one which: contrary to the requirement of good faith… causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations under the contract, to the detriment of the consumer. This formulation suggests that an unfair term has two key elements: a requirement of good faith and that the offending term would otherwise result in a ‘significant imbalance’ between the parties’ rights and obligations. The requirement of good faith may itself be said to have two parts: a procedural and a substantive aspect. The procedural aspect is in issue when a term’s existence came as a surprise to the party subject to it. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) considered the appropriate test in a case where a mortgagor who had defaulted on payments challenged a clause that increased the applicable rate of interest to almost 19 per cent per annum. The CJEU advised that the national court applying this requirement had to assess whether the seller or supplier, dealing fairly and equitably page 93 page 94 University of London International Programmes with the consumer, could reasonably assume that the consumer would have agreed to such a term in individual contract negotiations (Aziz v Caixa d’Estalvis de catalunya, Tarragona I Manresa (Catalunyacaixa) [2013] 3 CMLR 5). In West v Ian Finlay & Associates [2014] EWCA Civ 316 the Court of Appeal held that a term in a contract for architectural services was not unfair ‘…bearing in mind the savvy nature of the Wests …’ (at [60]) who were a professional couple comprising a successful banker and his wife, a neuroscientist. In contrast in Office of Fair Trading v Ashbourne Management Services Ltd [2011] All ER (D) 276 terms in gym membership agreements setting minimum membership periods of one, two or three years were considered unfair. The Court emphasised the defendant’s business model which was ‘calculated to take advantage of the naivety and inexperience of the average consumer using gym clubs at the lower end of the market.’ Where a term is put forward by either the consumer or the consumer’s professional advisers the element of unfair surprise will be absent and the clause most unlikely to be found to be unfair (Bryen & Langley Ltd v Boston [2005] EWCA Civ 973). The substantive aspect of the requirement of ‘good faith’ means that there will be some terms that will always be regarded as unfair whatever steps are taken to publicise them. Any such term is, however, likely to offend the second element of ‘unfairness’ (i.e. that the clause causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations). In this way there would appear to be a considerable overlap between the two requirements according to Lords Steyn and Bingham in Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank plc [2001] All ER (Comm) 1000 (at [17] and [37]). In OFT v Asbourne Management Services, considered above, the court emphasised the requirement that the imbalance in the parties’ rights must be a significant one. Terms in contracts for gym membership which prevented termination before the end of lengthy minimum membership periods had this effect whereas terms which permitted termination in defined circumstances before this period had elapsed might evidence an imbalance in the parties’ rights, but not a significant one (at [17]). Further explicit guidance on how to ascertain if a contract term is unfair is provided by s.62(5) which requires the court to take ‘into account the nature of the subject matter of the contract’ and ‘all the circumstances existing when the term was agreed and… all of the other terms of the contract…’. The timing mentioned here is important. The assessment of fairness is made when the contract is concluded; it is not a retrospective judgment and so cannot take account of circumstances that arise after the contract was entered. More specific guidance in the first version of the implementing Regulations expressly referred to: the bargaining positions of the parties; whether the consumer had an ‘inducement’ to accept the term; whether the goods or services were made to special order; and the extent to which the seller or supplier had acted fairly. These factors reflected parallel considerations under UCTA 1977 (see below). Though the factors may still be relevant under the CRA 2015 they are not expressly referred to in the Act. The ‘grey list’ The Regulations which preceded the CRA 2015 contained a list of terms which will be presumed to be unfair which became known as ‘the grey list’. An expanded version of this ‘indicative and non-exhaustive list of terms of consumer contracts that may be regarded as unfair’ is now found in CRA 2015 Schedule 2 Part 1. The list of presumptively unfair terms demonstrates the breadth of the CRA 2015 and extends beyond terms intended to exclude or restrict a trader’s liability for death or personal injury which are described in para.1 of the ‘grey list’. This provision does not affect a trader’s attempt to exclude liability for death and personal injury arising from negligence which is rendered unenforceable by s.65(1), as opposed to being presumptively unenforceable under Schedule 2. The ‘grey list’ refers to 20 different types of contractual provision including: Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract uu a term which permits the trader to retain, without compensation, sums paid by the consumer if the consumer decides not to continue with the contract (para.4) uu a term which requires a consumer who does not fulfil his obligations to pay a disproportionately high sum in compensation (para.6) uu a term which has the effect of binding the consumer to terms which the consumer, before contracting, had no real opportunity of becoming aware of (para.10) uu a term which allows the trader without a valid reason specified in the contract unilaterally to alter the contract terms (para.11) uu a term which permits the trader to increase the price of goods or services without the consumer having a corresponding right to cancel if the price demanded is too high compared to that first agreed (para.15). The terms added by the CRA 2015 to the ‘grey list’ are: uu a term which requires a consumer who does not fulfil his obligations to pay a disproportionately high sum in compensation for services that have not been supplied (para.5) uu a term which permits the trader to determine the characteristics of the contractual subject matter after the consumer has become bound by the contract (para.12) uu a term giving the trader a discretion to determine after the consumer has entered the contract the price payable where no method of price determination was made known before contracting (para.14). The consequence of unfairness Where a term is found to be unfair the rest of the contract ‘…continues, so far as practicable, to have effect in every other respect’ but the unfair term is ‘…not binding on the consumer’ (s.67). In Unicaja Banco SA v Hidalgo Rueda [2015] All ER (D) 142 the European Court of Justice, in a case involving a term in a mortgage that upon the debtor’s default increased the applicable rate of interest to 18 per cent, held that Directive 93/13 did not empower a national court to vary a term that is held to be unfair. Rather, the national court must ‘exclud[e] the application of that clause in its entirety with regard to that consumer’. However, a national court may, having ‘deleted’ an unfair term, substitute for it a supplementary provision of national law according to the same court’s decision in Kasler v OTP Jelzalogbank [2014] WLR (D) 180. In the latter case (at[79]) it was explained that a simple power of revision would compromise the primary purpose of the Directive because it would tempt sellers or suppliers (now ‘traders’) to use unfair terms in the knowledge that even if they were held invalid the contract would nevertheless be adjusted. Exclusion from the assessment of fairness under the CRA 2015 Certain terms do not, subject to certain conditions, fall within the power of review created by the CRA 2015. The most important category, which under the previous Regulations gave rise to extensive (and expensive – see Office of Fair Trading v Abbey National plc [2009] EWHC 36 (Comm), below) litigation, is now found in s.64(1). A contract may not be assessed for fairness …to the extent that: it specifies the main subject matter of the contract, or the assessment is of the price payable under the contract by comparison with the goods, digital content or services supplied under it. Significantly, this exclusion will only apply to terms that are ‘transparent and prominent’ according to s.64(2) (previously under the Regulations it needed to be in ‘plain intelligible language’). It is not certain whether this change of language has resulted in a change of meaning. However, both tests seem to provide for a high standard of comprehensibility that reaches beyond the common law doctrine of page 95 page 96 University of London International Programmes contra proferentem, discussed in Section 6.1.2, which merely resolves any ambiguity against the party relying upon the exclusion clause. In Kasler v OTP Jelezalogbank Zrt (2013) the European Court of Justice interpreted Directive 93/13 as requiring not only that the relevant term should be ‘grammatically intelligible’ to the consumer but further that it ‘should set out transparently the specific functioning [of the term] so that that consumer was in a position to evaluate, on the basis of clear, intelligible, criteria, the economic consequences’ (at [75]). This section states an important limit upon the scope of the CRA 2015. The CRA 2015, the preceding Regulations and the originating European Directive, provided that where certain tests are satisfied, terms in a contract which operate to the disadvantage of consumers will not be enforced. If the scope of this power of review is not precisely defined it would create uncertainty by leaving many contractual provisions at the core of a contract as liable to challenge. The purpose of CRA 2015 s.64 is to avoid putting in jeopardy of review all contractual provisions. This is achieved by providing that certain central or core matters are excluded from assessment as unfair. It is important to appreciate the effect of a wide, as opposed to a narrow, interpretation of these ‘exclusions’. If the excluding provision is interpreted broadly it would protect from review so many clauses that it might negate the very object of the original Directive. For this reason Lord Bingham, in Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank [2001] 1 All ER 240 cautioned that the ‘object of the regulations [then in force, now the CRA 2015] would plainly be frustrated if [the core exception was] so broadly interpreted as to cover any terms other than those falling squarely within it’ (at [12]). Consequently, the House of Lords held that a contractual provision providing that upon the debtor’s default on a loan the bank was entitled to recover the balance of the loan as well as outstanding interest and the cost of obtaining judgment did not define the main consideration which the bank anticipated from the loan. Rather it was a default provision whose operation was contingent upon the creditor’s breach. As it was not a core provision within the then applicable Regulations it was susceptible to review as an unfair term. A similar approach was applied in Office of Fair Trading v Foxtons Ltd [2009] EWHC 1662 (Ch) where a standard agreement with a letting agent provided for the payment by the landlord to the agent of a commission upon the introduction of a suitable tenant and again if that tenant renewed the lease. It was the requirement to pay a second or successive commission on renewal that was in dispute as this required no, or little, extra work by the agent. Again it was concluded that the provision for further payment was not a core term and so was susceptible to review. The judge emphasises the parties’ belief that the term would operate only in exceptional circumstances as well as its lack of conspicuousness. The Supreme Court’s decision in Office of Fair Trading v Abbey National plc (2009) would appear to conflict with the narrow interpretations of the core provisions’ exclusion examined in the previous two cases. The case concerned terms in contracts for the provision of personal banking services under which banks levied charges for so called ‘unauthorised overdrafts’ and was of huge commercial importance, involving all the leading UK banks, the smallest of which, Clydesdale bank, had over 2.4 million UK customers! In a decision that was, perhaps, popular only with the banks and the ‘all star’ legal cast representing them (at first instance including 11 Queen’s Counsel and all the major commercial firms of solicitors) the Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Court of Appeal. The Supreme Court held that it was not possible to distinguish between the different ways in which a bank charged for its services. The provision which was challenged, under which fees were charged for unauthorised overdrafts, contributed to the undifferentiated consideration the banks received in exchange for the provision of services. Consequently, the provision was a core term and so immune from challenge under the then prevailing Regulations as being unfair. The decision in Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank was distinguished, rather unconvincingly, on the basis that the case dealt with a clause that defined an ‘ancillary’ (at [113]) rather than the main consideration of the contract. Such a formal distinction would seem to push the courts in the direction which Lord Bingham was at pains in First National to avoid (i.e. an approach which seems to ‘frustrate’ the object of consumer protection that lies at the core of the original European Directive (93/13 EEC)). Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract In addition to the core terms, discussed above, which are excluded from review on the basis of unfairness, the CRA 2015 prohibits the exclusion of some liabilities. Section 65 provides that a trader cannot by a term in a consumer contract exclude liability for death or personal injury caused by negligence (reflecting the parallel provision in the UCTA 1977 s.2 now applicable only to businesses). Terms in contracts for the supply of goods to a consumer by a trader which exclude or limit the liability of the trader in respect of the goods’ unsatisfactory quality (s.9), fitness for a particular purpose (s.10) and conformity to description (s.11) or sample (s.13) may not, according to s.31, be excluded. This and associated prohibitions upon exclusion is sometimes referred to as a ‘black list’ in contrast to the presumptive unfairness of terms in the so called ‘grey list’ examined above. The obligations arising under ss.9, 10,11 and 13, whose exclusion is prohibited, correspond to terms formerly implied into contracts for the sale of goods by the SGA 1979 ss.11–14. The CRA 2015 contains parallel provisions to the s.31 prohibition on exclusion of liabilities arising under contracts for the sale of goods in ss.47 and 57 which apply to contracts under which a trader agrees to supply a consumer with, respectively, digital content and services. Enforcement The CRA 2015, like the Regulations it supersedes, both makes an ‘unfair’ term unenforceable in individual cases but also permits certain ‘regulators’ to take action against the use of such terms. We have seen that several of the important cases on the Regulations were brought by the Office of Fair Trading (OFT). The OFT was closed in 2014 pursuant to the Government’s policy of reducing the number of ‘quasi governmental’ bodies, or quangos. The successor to the OFT’s powers of intervention and enforcement is now the Competition and Markets Authority. Actions brought by such bodies may have wide market effects. In an action brought by an Austrian consumer organisation, Verein für Konsumenteninformation v Amazon EU Sarl (Case C-191/15) the European Court of Justice held that a clause in Amazon’s standard terms and conditions was unfair because it failed to alert the purchaser that private international law principles do not allow the exclusion of certain important principles of otherwise applicable national law. 6.2.2 The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 In contrast to Part 2 of the CRA 2015 which will render unenforceable by a trader against a consumer any unfair term, the UCTA 1977 is primarily concerned with only one type of ‘unfair’ term, namely, exclusion and limitation clauses, rather than ‘unfair terms’ in general. The scope of the UCTA 1977 has been further reduced by the CRA 2015 so that it will now apply only to contracts between businesses (so called B2B contracts (Schedule 4)). Certain types of contract are excluded from the main protective provisions of the UCTA 1977. These include contracts of insurance, contracts concerning land and international supply contracts (s.26 and Schedule 1). If the contract requires goods to be carried from one state to another it is classified as an international supply contract – as is a contract where, at the time of signing, it is expected, but not stipulated, that the goods will be so transported (Trident Turboprop (Dublin) Ltd v First Flight Couriers Ltd [2009] EWCA Civ 290). A preliminary question to ask, therefore, when considering the impact of the UCTA 1977 on an exclusion clause, is whether the Act applies to the contract at all. 6.2.3 Negligence liability The UCTA deals with clauses which attempt to exclude liability for ‘negligence’ in s.2. ‘Negligence’ is defined as covering: an obligation to take reasonable care in the performance of a contract; the tort of negligence; and liability under the Occupier’s Liability Act 1957. Under s.2(1) any contract term or notice which seeks to exclude or restrict liability for negligence causing death or personal injury is void. In contrast, s.2(2) provides that page 97 page 98 University of London International Programmes any contract term or notice which aims to exclude or restrict liability for negligently inflicted damage to property is not automatically rendered void. Instead it is subject to the reasonableness test. If the clause satisfies that test it is enforceable, if it does not, it is void. Section 2(2) of the UCTA deals with negligence giving rise to loss or damage apart from death or personal injury. We are talking here about damage to property or financial losses (lost profits, etc.). In relation to such loss or damage, s.2(2) provides that a clause purporting to restrict liability will only be effective ‘in so far as [it] satisfies the requirement of reasonableness’. The requirement of reasonableness is discussed below. 6.2.4 The ‘reasonableness’ test The standard of reasonableness referred to in s.2(2) is utilised throughout UCTA. Section 11 defines it as a requirement that the term was: a fair and reasonable one to be included having regard to the circumstances which were, or ought reasonably to have been known to… the parties when the contract was made. Three preliminary points should be noted before examining this important standard in more detail. First, the reasonableness of the term will be judged by reference to the time of entering the contract, without the benefit of hindsight (Stewart Gill Ltd v Horatio Myer & Co Ltd [1992] QB 600). This is clear from the wording of the section. Second, the burden of proving that the clause is reasonable is borne by the party relying upon it (s.11(5)). Third, it is difficult to generalise about the application of the standard of reasonableness because each case very much depends upon its own facts. The emphasis upon the facts of the case as found by the judge at first instance means that courts of appeal are reluctant to interfere with the decision of the trial judge ‘… unless satisfied that [he/she] proceeded on some erroneous principle or was plainly and obviously wrong’ (George Mitchell Ltd v Finney Lock Seeds [1983] 2 AC 803). Fortunately, UCTA itself provides some further guidance. When considering a limitation, as opposed to an exclusion, clause s.11(4) provides that the court should take account of the resources of the person who may be subject to liability as well as the extent to which that liability might have been covered by insurance. However, the availability and cost of insurance has been referred to many times in relation to cases involving exemption clauses (e.g. Smith v Eric S Bush (1989)). Section 11(2) refers to a number of guidelines contained in Schedule 2 which should be taken into account in assessing reasonableness. This checklist is only expressly said to be relevant when considering the concept of reasonableness to be applied under UCTA ss.6 and 7 (dealing with the exclusion of statutory implied terms). This formal position has been ignored and the checklist is considered to be relevant to any section of UCTA that seeks to apply the standard of reasonableness (see Overseas Medical Supplies Ltd v Orient Transport Services Ltd [1999] Lloyd’s Rep 273). A key factor is the relative bargaining positions of the parties. Recent cases have paid particular attention to this factor, which has been said to be ‘the starting point’ for any enquiry into the reasonableness of a contractual exclusion (Axa Sun Life Services v Campbell Martin (2011) at [59]). In Watford Electronics v Sanderson [2001] EWCA Civ 317 the claimant sought damages of over £5.5 million including loss of profits for breach of a contract to supply a bespoke software system. The Court of Appeal held that clauses which excluded liability for indirect or consequential loss and which also limited any other liability to the contract price of £104,600 were reasonable. The parties to the contract were experienced business people who had decided to allocate the risks of defective or non-performance in a particular way which the court should not upset. Chadwick LJ (at [54]) said that the court should only interfere when satisfied that ‘one party has, in effect, taken advantage of the other’ or where ‘the term is so unreasonable that it cannot properly have been understood or considered’. Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract This approach of respecting, and so enforcing, the terms negotiated by commercial contractors of roughly equal bargaining power is a further application of the approach to fundamental breach that was applied in Photo Production v Securicor [1980] 3 All ER 146 (see above Section 6.1.3). Other recent applications include: uu Sterling Hydraulics Ltd v Dichtomatik [2006] EWHC 2004. Clauses in a contract for the sale of engine seals similar to those in Watford Electronics v Sanderson were upheld. uu Regus (UK) v Epcot Solutions [2008] EWCA Civ 361. In a contract for serviced office accommodation clauses limiting liability for loss of profit and commercial losses were held to be reasonable. The Court of Appeal was possibly influenced by the fact that the party subject to the clause used a similar provision in his own business! 6.2.5 Contractual liability The exclusion of contractual liability other than through negligence is covered by s.3 of the UCTA. This will now only apply in a business context where one of the parties deals on the other’s ‘written standard terms of business’. This implies two preconditions: that the relevant party has written standard terms of business and that, on this occasion, he contracted on the basis of them. Where the contract is preceded by negotiations that leave the ‘general conditions… substantially untouched’ the parties will still be held to be contracting on written standard terms of business (St Albans City and District Council v International Computers Ltd [1996] 95 LGR 592). However, ‘any significant difference’ between the terms proposed and agreed will indicate that the contract was not on the other’s written standard terms (Yuanda (UK) Co Ltd v W W Gear Construction Ltd [2011] 1 All ER (Comm) at [26]). Section s.3(2) makes any attempt to exclude or limit liability subject to the requirement of reasonableness – s.3(2)(a). It also subjects to the same test clauses which purport to allow a party ‘to render a contractual performance substantially different from that which was reasonably expected’, or ‘to render no performance at all’ – s.3(2)(b). There is an important distinction between the provisions contained in s.3(2)(a) and s.3(2)(b). It appears that s.3(2)(a) is aimed at the ‘classic type’ of exclusion clause ‘exonerating a contractual party in default from the ordinary consequences of that default’ according to Bingham MR in Timeload Ltd v British Telecommunications plc [1995] EMLR 459. The proper interpretation of s.3(2)(b) has been more problematic. It must be intended to apply to situations where the party seeking to rely on the clause is not himself in breach of contract, otherwise it would add nothing to s.3(2)(a). In Axa Sun Life Services v Campbell Martin [2011] EWCA Civ 133, the Court of Appeal held that a so called ‘entire agreement clause’ (i.e. one stating that a particular document contained all the parties’ contractual terms) is not subject to s.3(2)(a) because it seems to prevent any collateral contract from arising, but it could nonetheless be caught by s.3(2)(b). In AXA Sun Life Services plc v Campbell Martin Ltd (2011), the Court of Appeal began its consideration of reasonableness with the recognition that the agreements were made between commercial organisations in a commercial context, although the claimant was a larger entity than the defendants. Activity 6.6 A Ltd engages B Ltd to service the machines in A Ltd’s factory. The contract is based on a written contract put forward by B Ltd. There is, however, considerable negotiation over the price and the periods between services before the contract is agreed. Will it fall within the scope of s.3 of the UCTA? Activity 6.7 C Ltd contracts with D Ltd for D Ltd to paint the exterior of C’s office premises. The contract is made through an exchange of letters. Is the contract within s.3 of the UCTA? page 99 page 100 University of London International Programmes 6.2.6 The supply of goods The UCTA 1977 contains special provisions in ss.6 and 7 dealing with contracts for the sale or supply of goods. This includes hire purchase, hire transactions and contracts for the supply of work and materials. In relation to the statutorily implied terms as to title (ownership) that operate in relation to such contracts, the UCTA prohibits any exclusion of liability. In relation to the implied terms as to description or quality (for example, under ss.13 and 14 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979), then liability under these terms can only be excluded or limited in so far as the clause satisfies the requirement of reasonableness. Previously, UCTA regulated the exclusion of the same terms when the purchaser of goods or services was a consumer. However, since the CRA 2015 came into force both the underlying obligations (as to title, description, quality, etc.) and the control of their exclusion is found in the 2015 Act (see above at Section 6.2.1). Activity 6.8 To answer a question involving an exemption clause requires a number of questions to be asked. What are these questions and in what order should they be asked? If you find it helpful you may wish to present these as a flow chart. Activity 6.9 Xerxes plc includes an exclusion clause in all its contracts stating that ‘Xerxes plc is in no circumstances liable for any losses whatsoever resulting from the breach of this contract, whether resulting from negligence or any other cause.’ Xerxes has broken a contract with Zenon Ltd. The contract is worth £50,000 to Zenon. Xerxes’ breach, which is not caused by the negligence of Xerxes or any of its employees, causes Zenon a loss of £2,500. Zenon claims this amount from Xerxes. Can Xerxes rely on the clause? Self-assessment questions 1. Name three types of contract that are not covered by the provisions of the UCTA. 2. What is the general attitude of the courts to those who make contracts by way of business? 3. What, in general, do exclusion clauses purport to exclude? Summary The CRA 2015 has made many changes and we have yet to see the true impact and application of this Act. The protection offered by this Act is much broader in its control of consumer contracts than the UCTA. The UCTA now applies to certain contracts concluded between parties acting in the course of business. Clauses are either rendered invalid or made subject to the requirement of reasonableness. Clauses which are invalid are those excluding liability for negligence causing death or personal injury and those excluding liability for the implied terms in supply of goods contracts with consumers. Clauses which are subject to the test of reasonableness include those excluding liability for negligence causing loss or damage to property; clauses excluding contractual liability in relation to those contracting on the other party’s written standard terms; and clauses excluding liability for the implied terms in supply of goods contracts with business customers. The test of reasonableness looks at all the circumstances of the case, but inequality in the strength of bargaining power is likely to be a particularly strong consideration. Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, Chapter 23 ‘Consumer Rights Act’. Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract Sample examination question Andrew is a surveyor. Four months ago he bought a nine-month old ‘Landmaster’ car from Brenda’s Garage Ltd for use in his practice. He paid £12,500 for the car. As part of the contract for the purchase of the car he was given a written guarantee in the following terms: ‘Brenda’s Garage Ltd guarantees that, for three months from the date of purchase, it will put right free of charge any defects in the vehicle which cannot be discovered on proper examination at the time of purchase. Thereafter all work and materials will be charged to the customer.’ The sales manager recommended to Andrew that he should take out the ‘special extended warranty’ under which, for payment of £350, the car would have been guaranteed in respect of all defects for a further two years, but Andrew declined. Last week the engine and gearbox seized up. The repairs will cost £2,000. Advise Andrew. Would your answer differ if he also used the car at the weekends for domestic purposes? Advice on answering the question In answering questions of this type you should start by indicating the way in which the potential defendant is in breach of contract. Here it is to be assumed that Brenda’s Garage is in breach of contract as regards the implied term of satisfactory quality under s.14 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979. The question then becomes whether Brenda’s Garage can take advantage of the exclusion of liability which is included in the ‘guarantee’. This aspect of the question was examined in Chapter 5. We turn now to the issues of whether or not the clause was incorporated and, if so, how the clause is regulated by the legislation. As regards the common law rules, the main issue would seem to be that of ‘incorporation’. Was the ‘guarantee’ and the exclusion clause which it contains part of Brenda’s Garage’s contract with Andrew? This will depend on whether the clause was shown to Andrew before or at the time when he entered into the contract. If it was handed to him after he had made the contract for the purchase of the car then it would probably not be incorporated, and would therefore be ineffective (Olley v Marlborough Court). One argument against this which the garage might use would be that there was a separate unilateral contract under which Brenda’s Garage Ltd said, ‘we will give you a three month full guarantee, in return for your acceptance of the limitation of our liability after three months’. Assuming that the exclusion clause was incorporated, there would not seem to be any argument that it covers the breach which occurred. Any detailed discussion of the rules of construction is therefore unnecessary. The main focus in answering this question should be the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977. (Note that the Consumer Rights Act 2015 does not apply, since Andrew is not a consumer for the purposes of those regulations.) Since the contract is for the sale of goods, then the relevant provision is s.6. This requires you to decide whether Andrew is contracting as a consumer (as defined in s.12 of the UCTA) or not. Is he buying the car in the course of his business as a surveyor? It seems likely that he is (but see R & B Customs Brokers Co Ltd v United Dominions Trust Ltd [1988] 1 All ER 847). If so then the clause limiting liability must satisfy the requirement of reasonableness. In applying this test, as well as thinking about the matters set out in Schedule 2 to the UCTA, you should note the offer of the extended guarantee. Does Andrew’s rejection of this opportunity mean that the exclusion contained in the guarantee is more reasonable? The alternative scenario increases the likelihood that Andrew will be treated as contracting as a consumer under the R & B Customs Brokers’ approach. If he is contracting as a consumer then the Garage will be unable to exclude its liability under the Consumer Rights Act 2015. page 101 page 102 University of London International Programmes Quick quiz Question 1 Which of the following is not a statutory guideline for the purpose of explaining the reasonableness test in the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977? Choose one answer. a. The parties’ respective bargaining power, taking into account any alternative means of meeting the customer’s requirements. b. Whether the customer offered the seller a financial inducement to waive the exemption clause. c. The availability and efficiency of insurance. d. Whether the customer knew or ought reasonably to have known of the existence and extent of the term. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Review the House of Lords’ decision in Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank (2001) and decide which of the following statements best describes how the court will decide that a contractual term is unfair under the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contract Regulations 1999, which may inform the application of the Consumer Rights Act 2015? a. The term is unfair where there is an inequality in the strength of the bargaining positions of the parties relative to each other, where the customer has received an inducement to agree to the term and where the customer did not know of the existence and extent of the term. b. The term is unfair if it causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations under the contract to the detriment of the consumer in a manner or to an extent which is contrary to the requirement of good faith. c. The term is unfair if there is a general inequality of bargaining power and the court feels compelled to set the term aside if it is relied upon. d. The term is unfair if the party who relied on it did not bring it to the attention of the other party to the contract when the negotiations were taking place. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following statements is false? a. There was a substantial overlap between the provisions of the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 and the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977. b. The Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 only worked to protect consumers whereas the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 could sometimes protect a business. c. The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 is largely concerned with exemption clauses while the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 extended to a much wider range of contractual clauses. d. Reasonableness under the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 was exactly the same as fairness under the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999. e. Don’t know. Contract law 6 The regulation of the terms of the contract Question 4 Which of the following is not a principle in deciding whether a clause covers liability for negligence in the performance of a contract? a. If the clause contains express language exempting a person from the consequence of the negligence, effect must be given to it. b. If there is no express reference to such negligence, the court must consider whether the words used are wide enough, in their ordinary meaning, to cover it. c. If there is no express reference to such negligence, the court must consider whether the words used are wide enough, in their ordinary meaning, to exclude it. d. If the words used are wide enough, the court must then consider whether liability may be based on some ground other than negligence; if so, this will prevent reliance on the clause in relation to negligence. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Which of the following statements is true? a. From the last quarter of the 20th century, courts increasingly relied upon Parliament to regulate the content of contracts for substantive fairness and reasonability rather than devising their own means to do so. b. The doctrine of fundamental breach, expounded in decisions such as Harbutt’s Plasticine Ltd v Wayne Tank and Pump Co Ltd (1970) per Lord Denning, provides that once there has been a fundamental breach of contract, no exclusion clauses can operate as a defence to that breach. c. If a party agrees to a term in a contract, then that party is absolutely bound by the term by reason of this agreement. d. Contractual terms are interpreted against the party who accepts the term proffered. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. How do the courts decide whether a clause has been incorporated into a contract? 2. What are the rules for the construction of exclusion clauses? 3. Give examples of a ‘fundamental breach’ of contract and explain its effect on an exclusion clause. 4. What kinds of clauses are invalidated by the UCTA and Consumer Rights Act? 5. What kinds of clauses are required to be ‘reasonable’ by the UCTA or fair under Consumer Rights Act? 6. What is the test of ‘unfairness’? 7. Give examples of the kinds of clauses which are invalidated by the Consumer Rights Act. page 103 page 104 Notes University of London International Programmes Part III The capacity to contract – minors 7 Contracts made by minors Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106 7.1 Contracts for necessaries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107 7.2 Beneficial contracts of service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107 7.3 Voidable contracts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108 7.4 Recovery of property . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110 page 106 University of London International Programmes Introduction A minor is a young person under the age of 18 years. A minor is not considered to have the same capacities as an adult. One of these capacities is the ability to enter into a legally binding contract. An adult with full mental capabilities has capacity to enter into a contract. Certain persons do not have full contractual capacity. They include the drunk, the mentally disordered, minors, unincorporated associations, corporations, the Crown and public authorities. Within this category of persons who lack capacity, the syllabus of this course only considers minors. Important changes to this area were made by the Minors’ Contracts Act 1987. The general rule is that a minor is not bound by a contract he enters into during his minority. The purpose of the rule is to protect minors against their own inexperience and improvidence by relieving them of liability on contracts made by them but, in some cases, the rights of the other party must in fairness be allowed to prevail over this policy of protection. The issues to concentrate upon are: uu contracts for necessaries uu beneficial contracts of service uu voidable contracts uu the recovery of money paid or property handed over in pursuance of a non-binding contract. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the regulation of contracts made by minors to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu Contracts for necessaries and beneficial contracts of service. uu The consequences of failure by the minor to pay for goods or services. uu The differences between the effect of contracts which have been performed and those which are still unperformed. uu Whether the supplier has any prospect of recovering the goods from the minor. Contract law 7 Contracts made by minors 7.1 Contracts for necessaries Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 16 ‘Capacity’ – Section 16.1 ‘Introduction’ and Section 16.2 ‘Minors’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 5 ‘Intention to be legally bound and capacity to contract’ – Section 2 ‘Capacity to contract: minors’ contracts’. The rule with regard to necessaries in contracts for the sale of goods is defined by s.3(3) of the Sale of Goods Act 1979. The definition states that necessaries are ‘goods suitable to the condition in life of the minor ...and to his actual requirements at the time of the sale and delivery’. Note that ‘necessaries’ do not mean ‘necessities’ but goods which are suitable to the minor’s ‘condition in life’ and his actual requirements (Peters v Fleming [1840] 6 M & W 42). The emphasis upon the individual minor’s status means that the older cases appear odd to a modern reader and contain many ‘quaint examples of a bygone age’ (Allen v Bloomsbury Health Authority [1993] 1 All ER 651). Examples include Hands v Slaney (1800) 8 Term Rep 578 where a servant’s uniform was a necessity when purchased by a gentleman and Nash v Inman [1908] 2 KB 1 where the court decided that the purchase of several ‘fancy waistcoats’ was not a purchase of necessary goods when the buyer owned several already. The liability is to pay a reasonable price, not the contract price. You will note that necessaries may include services and that the beneficial contracts of service considered in the next section are also regarded as another form of necessaries. See, for example, Roberts v Gray [1913] 1 KB 520 where the minor was held liable for breach of an executory contract. Activity 7.1 How can the supplier know whether young Inman already has enough waistcoats? Is the law perhaps being overprotective here? Activity 7.2 Would the decision in Roberts v Gray also apply to an executory contract for necessary goods? Summary At common law, minority was not a defence where the contract was for necessaries. Necessaries could either be goods or a contract for services. Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 7 ‘Incapacity’. 7.2 Beneficial contracts of service Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 16 ‘Capacity’ – Section 16.2 ‘Minors’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 5 ‘Intention to be legally bound and capacity to contract’ – Section 2 ‘Capacity to contract: minors’ contracts’. A minor is generally bound by a contract of employment where that contract is beneficial to them. This category includes contracts of apprenticeship, training or employment and professional engagements. As to the overriding requirement that the contract as a whole must be beneficial to the minor, see, for example, Doyle v White City Stadium [1935] 1 KB 110, and Chaplin v Leslie Frewin (Publishers) [1966] Ch 71 and contrast De Francesco v Barnum [1880] 43 Ch D 165. In Proform Sports Management Ltd v Proactive Sports Management Ltd [2006] EWHC 2903 it was held that a player representation contract entered into by the footballer Wayne page 107 page 108 University of London International Programmes Rooney at the age of 15 was not enforceable against Rooney as he was a minor but was voidable at his option. In addition, the contract was not analogous to a contract for necessaries nor was it a contract of apprenticeship, education or service since Rooney was already with a football club and could not become a professional footballer because of his age. Note that trading contracts are not included. Activity 7.3 Why should trading be treated differently from exercising a profession? Summary A minor will generally be bound where the contract is one of employment which is beneficial to them. Trading activities are excluded from this category. Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 7 ‘Incapacity’. 7.3 Voidable contracts Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 16 ‘Capacity’ – Section 16.2 ‘Minors’. In this very mixed group of contracts, the minor may rid himself of his obligations if he repudiates the contract before attaining the age of 18 or within a reasonable time after that. What this means is that the contracts are voidable at the minor’s option. A voidable contract is a contract which exists, but which one party has a right to set aside or render void. This right can be lost in certain circumstances. The most common of these circumstances is the intervention of a third party who has acquired rights following from the voidable contract. A voidable contract is different from a void contract in that a void contract is an entity which was never a contract. The term is, therefore, a paradox. The distinction between void and voidable is discussed again in Chapter 8 in relation to ‘mistake’. There seems to be no convincing explanation for the separate treatment of this group. If the minor needs protection, why are the contracts not simply void? 7.4 Recovery of property Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 16 ‘Capacity’ – Section 16.2 ‘Minors’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 5 ‘Intention to be legally bound and capacity to contract’ – Section 2 ‘Capacity to contract: minors’ contracts’. Previously, at common law, all other contracts (i.e. those neither for necessaries nor falling within the anomalous class of voidable contracts) were not binding on the minor unless he ratified them after reaching majority, but they could be enforced by the minor if he chose. The Infants Relief Act 1874 did away with ratification and made many of the contracts ‘absolutely void’ but the Minors’ Contracts Act 1987 restores the possibility of ratification and provides (s.3) a new remedy of restitution in favour of the other contracting party. This remedy is discretionary but cases such as Stocks v Wilson [1913] 2 KB 235 and Leslie v Sheill [1914] 3 KB 607 illustrate the factors which will be taken into account. Activity 7.4 What is the position of a minor who purchases, and pays for, non-necessary goods but who now wants to cancel the transaction? Contract law 7 Contracts made by minors Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 7 ‘Incapacity’. Examination advice A review of past examination papers indicates that this is a topic which has usually occurred as part of a problem involving other issues. Sample examination question Linda left school last year at the age of 16. She took a job as a trainee kitchen assistant in a hotel. Her wages are £50 a week and she is required to give three months’ notice to terminate her employment. She recently agreed to buy an ‘Osaka’ motorcycle so that she could spend more time with her boyfriend Malcolm, who is mad about motorcycles. She also signed a written agreement to buy a one-quarter share in a racing greyhound called Dingo. Linda has now been offered a job as a cook in a restaurant at £100 a week, provided she can start immediately. She has failed to pay for the motorcycle or the share in Dingo. Advise Linda. Advice on answering the question This question presents the issue of incapacity by reason of Linda’s minority in three different contracts. You need to deal with each in turn because they raise slightly different issues. With the first contract, you need to consider whether or not her job as a trainee kitchen assistant is a necessary in that it is a contract of employment beneficial to her. You need to consider the case law in this area, notably Roberts v Gray (1913). The balance of probabilities favours this being a contract of employment from which she will benefit. Accordingly, it is binding upon her. With regard to the motorcycle, you need to consider whether or not this is a necessary within the meaning of s.3 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979, in light of the decision in Nash v Inman. On the one hand, the motorcycle seems something of an extravagance; on the other hand, it is possible to argue that she needs it for transportation (possibly to her employment). The reason given is that she needs it to spend time with her boyfriend Malcolm, which works against the argument that it is a necessary. The purchase of a share in the racing greyhound would appear to be something in the nature of a trade. Accordingly, this contract is unlikely to be enforceable. Your advice to Linda is that she is bound by her contract of employment, may be bound by the contract to purchase the motorcycle and is unlikely to be bound by the contract to purchase a share in the greyhound. Quick quiz Question 1 When will a contract of employment be binding upon a minor? a. When the contract is viewed as not beneficial to the minor. b. When the contract is viewed as absolutely beneficial to the minor. c. When the contract is viewed as being beneficial on the whole to the minor. d. When the contract is viewed as providing some minimal benefit to the minor. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Which of the following statements is true? a. A minor must always pay the contract price for a necessary. page 109 page 110 University of London International Programmes b. A minor must sometimes pay the contract price for a necessary. c. A minor must pay a reasonable price for a necessary. d. A minor need never pay for a necessary. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which best defines the legal conception of a necessary? a. A necessary is a good suitable to the condition in life of the minor and to her actual requirements at the time of the sale and delivery. b. A necessary is a good unsuitable to the condition in life of the minor and to her actual requirements at the time of the sale and delivery. c. A necessary is a good suitable to the minor’s lifestyle at the time the contract is entered into between the parties. d. A necessary is land suitable for use by the minor. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Which of the following is likely to be a necessary? a. A computer designed to allow a twelve-year-old from a middle income family to play online games. b. A computer used to facilitate online school studies by a twelve-year-old from a poor family which lacks access to an electrical supply. c. A computer used to facilitate online studies by a twelve-year-old from a middle income family which has access to an electrical supply. d. A computer used to facilitate online studies by a twelve-year-old from a wealthy family which has already provided the twelve-year-old with three other computers. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What are contracts for necessaries and beneficial contracts of service? 2. What are the consequences of failure by the minor to pay for goods or services? 3. What are the differences between the effect of contracts which have been performed and those which are still to be executed? 4. When does the supplier have any prospect of recovering the goods from the minor? Part IV Vitiating elements in the formation of a contract 8 Mistake Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112 8.1 Some guidelines on mistake . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113 8.2 Bilateral mistakes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114 8.3 Unilateral mistakes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119 8.4 Mistake in equity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129 page 112 University of London International Programmes Introduction Mistake is a difficult area of contract law. A major reason for the difficulty is that the common law recognises no comprehensive theory of mistake. Consequently, many of the decisions are difficult to reconcile with each other. This difficulty is made worse by the fact that the number of mistake cases is quite small. A further complication is that judges, authors and lawyers often use different terms to describe the same concept (and at other times use the same term to describe different concepts). Consequently, accounts of this area of law are often structured in very different ways giving an impression that different authors have a different view of the underlying law. This is usually a misimpression that arises from a different scheme of organisation and presentation. The same point may be made about the topic of Illegality considered in Chapter 12. For this reason it is recommended that you do not read a second textbook account of these subjects if you are happy that you have understood the first account that you have read. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the effect upon an otherwise valid contract of any mistake made by the contracting parties to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu What is a contractual mistake? uu The relationship between the doctrines of mistake and misrepresentation including the different effects of each if established. uu The different categories of operative mistake including key distinctions between agreement and non-agreement mistakes and the varying vocabularies used to describe key distinctions and concepts. uu The distinction and relevance of the different approaches of law and equity to questions of mistake. Contract law 8 Mistake 8.1 Some guidelines on mistake A few guidelines may assist you as you approach this topic. 1. Mistakes can be either unilateral (a mistake of one party only) or bilateral (a mistake of both parties). In general, the law will only provide relief where the mistake is a bilateral mistake – although there are some important exceptions to this point. 2. The parties may share the same bilateral mistake (it is a ‘common’ or ‘mutual’ mistake) or they may each be mistaken, but with respect to a different point. 3. At common law, an operative mistake will render a contract void. In equity, the effect of mistake may be to render the contract voidable. The distinction bears repeating at this point. A void contract is, of course, one that never comes into existence. A voidable contract is one that comes into existence but is subsequently liable to be set aside. Equity seeks to provide whatever remedy is just in the circumstances. Mistake in equity rendering a contract voidable is, however, doubted in English law at present. 4. Many cases can be explained upon different grounds than that of mistake. 5. Courts are reluctant to find an operative mistake. A possible reason for this is that to do so does, to a certain extent, rewrite the contract between the parties. Another possible reason is that if a court finds that a contract is void for mistake, this may well affect the rights of innocent third parties. 6. Many mistake cases will present the same fact patterns as misrepresentation cases – indeed, in the majority of cases, a claimant would be advised to claim that a misrepresentation had been made rather than a mistake. This is partly because of the availability of damages for a misrepresentation, but also because the changes effected by the Misrepresentation Act 1967 make a misrepresentation easier to prove. (See Chapter 9.) This overlap has clear consequences for how problem answers should be structured. 7. When you have studied this chapter you will see that the English law of contract has a narrow doctrine of mistake. However, the overlap with misrepresentation is significant here. The ungenerous approach to relief that follows from a narrow doctrine of mistake is mitigated by a comparatively broad, and so generous to relief, doctrine of misrepresentation. 8.1.1 Mistake at common law and in equity It may assist you to think about mistake in different categories. The most significant division is between mistake at common law and mistake in equity. We will begin with mistake at common law, because if the mistake is an operative one, the contract is void – and so there is no need to consider mistake in equity. We will also begin with bilateral mistakes and consider different types of bilateral mistakes – that is to say, the circumstances in which courts will find that a mistake of both parties is sufficiently fundamental to invalidate the apparent contract. In these cases, if the mistake is operative it is said to result in what is best described as a paradox: a void contract. Because of the mistake, the apparent agreement of the parties lacks consensus and there is no (nor ever was any) contract. 8.1.2 Mistakes of law and mistakes of fact English contract law long barred relief where the mistake was one of law rather than of fact. Exceptions existed to this bar – a common one was that a mistake as to private rights was not a mistake of fact (e.g. Cooper v Phibbs [1867] LR 2 HL 149). In Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Lincoln City Council [1999] 2 AC 349 the House of Lords allowed recovery of a mistaken payment where the mistake was one of law. In Brennan v Bolt Burdon [2004] 1 WLR 1240 the Court of Appeal applied this decision and held that the contractual compromise of a legal claim could be void as a result of a common mistake of page 113 page 114 University of London International Programmes law. It was a question of construction as to whether or not the mistake made the compromise impossible (Great Peace Shipping Ltd v Tsavliris Salvage Ltd (The Great Peace) [2002] 4 All ER 689). Where there was a doubt as to the law concerned, there was no mistake of law sufficient to render the contract void. 8.2 Bilateral mistakes There are two basic types of bilateral mistakes. In the first case, each of the parties is mistaken, but they do not share their mistake. In the second case, the parties share their mistake. 8.2.1 Absence of genuine agreement Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 4 ‘Certainty and agreement mistakes’ – Section 4.6 ‘Mistake negativing consent’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 3 ‘Agreement problems’ – Section 2A ‘Mutual mistake’. In situations where there is an absence of genuine agreement, the parties are each mistaken, but they do not share a mistake. Their separate mistakes are sufficiently fundamental, however, that no contract can be created. It is sometimes said that the parties are at ‘cross purposes’ and that the offer and acceptance do not correspond. No contract can arise because there is an absence of agreement. A contract cannot be formed in these circumstances because, on an objective interpretation, it cannot be said what was intended by the parties. Another description of this process is that the mistake ‘negatives’ the consent of the parties to contract. They have, in other words, failed to create an agreement. The leading case is Raffles v Wichelhaus [1864] 2 H&C 906. Here, one party bought, and the other party sold, cotton to be shipped on the vessel Peerless from Bombay. Unknown to either party, there were two ships Peerless, and each intended a different ship. The court found that there was no contract. See also Scriven Bros & Co v Hindley & Co [1913] 3 KB 564 (see also Chapter 2, Section 2.1.1). Activity 8.1 Suppose the buyers in Scriven v Hindley had been suing for damages for non-delivery of hemp. Would the contract still have been held to be void? Summary The parties are said to be at ‘cross purposes’ when the offer and acceptance do not correspond. In these circumstances, no contract can arise. 8.2.2 Common mistake Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.2 ‘Common mistake’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 13 ‘Common mistake: initial impossibility’ – Section 2 ‘The theoretical basis for the doctrine of common mistake’. ¢¢ Chandler, A., J. Devenney and J. Poole, ‘Common mistake: a theoretical justification and remedial inflexibility’ (2004) JBL 34–58, available through the Online Library. Common mistake (sometimes, confusingly, referred to as mutual mistake) occurs where both parties to a contract make the same mistake about a critical element of their agreement. The leading case dealing with mistake, and this type of mistake in particular, is Bell v Lever Brothers [1931] 1 KB 557. In this case, Lord Atkin stated that when Contract law 8 Mistake mistake operates upon a contract, it does so to negative or nullify the consent of the parties. Common mistake deals with those situations where an apparent contract lacks consent and consequently the contract is void ab initio (void from the outset). This approach to mistake is dependent upon a consensual theory of contract – that is to say, if a contract exists it is due to the consensus or agreement of the parties. The court enforces the contract on the basis of this consensus. Mistake operates to disrupt this consensus – it removes any consensus and consequently no contract can arise in the circumstances. Because English law has yet to work out any comprehensive theory of mistake, it is best to approach the subject by examining different situations where courts have found that there was no contract. You should keep in mind as you examine these cases that many of them can also be rationalised on grounds other than mistake. 8.2.3 Non-existence of the subject matter Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.3 ‘Mistake as to the existence of the subject-matter of the contract’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 13 ‘Common mistake: initial impossibility’, Section 3A ‘Res extincta’. In some situations, parties may reach an agreement to deal with a subject matter which, unknown to either party, does not exist. These cases deal with the problem of res extincta. Note that in these cases, the contract suffers from an initial impossibility; from the outset it cannot be performed. An example of such a situation is where A, the seller, contracts to sell his horse to B, the buyer. Without A or B’s knowledge, at the time the contract is entered into the horse is dead. It is, therefore, impossible for A to sell B his horse. In the leading case, Couturier v Hastie [1856] UKHL J3, the seller ‘sold’ a cargo of corn to the buyer. Neither party was aware of the fact that, at the time of the ‘sale’ the captain of the ship carrying the corn had sold the corn. This case has been taken to stand for the proposition that in a contract for the sale of goods, where the goods have perished without the seller’s knowledge, the contract is void – s.6 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979. You will note that in Couturier v Hastie the House of Lords did not call the contract void nor did they consider what the position would have been if the buyer had claimed damages for non-delivery. However, this understanding of the case was at least partially incorporated into the 1893 (see now 1979) Sale of Goods Act, s.6, which expressly provides that in a contract for the sale of goods, where the goods have perished without the seller’s knowledge, the contract is void. It should be noted here that s.6 applies to goods that have ‘perished’ (i.e. to goods that once existed and subsequently ceased to exist). It will not apply to goods which the parties mistakenly thought existed but which, in fact, never existed. It is, however, possible to interpret Couturier v Hastie differently and this is what the High Court of Australia did in McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission [1951] 84 CLR 377. The High Court of Australia expressed doubt that Couturier v Hastie involved issues of mistake and that, properly understood, the case was about the proper construction of the contract entered. In McRae the claimants sent a ship to salvage the wreck of a tanker which they had purchased from the defendants. In fact no such tanker existed at the location given and the case proceeds on the basis that neither party was aware of this mistake. The claimant succeeded in their action for breach of contract. The contract was analysed as one for goods that were guaranteed to exist. An alternative construction would have been that the contract was one for the sale of the wreck, if it existed at that location. If this construction had been taken then the claimant’s action for breach of contract would have failed. The subject matter of the contract would then have been a ‘chance’ (sometimes called an ‘adventure’). It may seem odd that a party would purchase such a chance but that in essence is what the purchase of a lottery ticket is, the purchase of a chance of winning. If this had been the construction applied in McRae the claimant page 115 page 116 University of London International Programmes would have no more valid claim for breach of contract than would the purchaser of a lottery ticket who demanded the price back after the draw because the ticket did not win! The result and approach in McRae seems correct. Put slightly differently, the result depends upon which party under the terms of the contract is allocated the risk that the goods may not exist. In McRae this risk was assumed by the seller who guaranteed the goods’ existence and so became liable when they did not exist. This approach was approved by the Court of Appeal in The Great Peace (2002), However, if the Sale of Goods Act 1979 s.6 applies, the court is prevented from taking account of the construction of the contract; the section simply states that the contract is void. The law in this area is therefore untidy with different principles applying when there is a shared mistake as to the existence of the subject matter of the contract where: goods which once existed have subsequently perished (contract is void according to s.6 and so no action may be brought) and goods which never existed (an action may be maintained depending on the proper construction of the contract: McRae). Summary Where the subject matter of the contract does not exist at the time of the contract, courts must find that the contract is void where Sale of Goods Act s.6 applies. In cases falling outside s.6, whether a party may sue for breach of contract will depend upon the proper construction of that contract. Further reading ¢¢ Atiyah, P.S. ‘Couturier v Hastie and the sale of non-existent goods’ (1957) 78 Law Quarterly Review 340. 8.2.4 Mistakes as to ownership Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.5 ‘Mistake as to the possibility of performing the contract’. Like the situation of the non-existent subject matter, these cases involve a situation of initial impossibility. One party agrees to sell and the other party agrees to buy something which, unknown to either of them, is already owned by the buyer. This is described as the sale of a res sua. The agreement cannot be performed because it is impossible to transfer the ownership since the ‘buyer’ already owns the thing. See Cooper v Phibbs (1867) as explained by the Court of Appeal in The Great Peace (2002). Activity 8.2 If the seller of a good which had never existed warranted that it did exist, would the contract of sale be void? Activity 8.3 Is it possible to regard Couturier v Hastie as a case where the seller provided no consideration? Activity 8.4 To what extent, if any, can cases such as Cooper v Phibbs be understood as cases where there is a defective consent to the contract? Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 8 ‘Mistake’. 8.2.5 Mistake as to the possibility of performance Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.5 ‘Mistake as to the possibility of performing the contract’. Contract law 8 Mistake In some circumstances the parties may be mistaken as to the possibility of performance. The parties have a shared misapprehension that performance of their agreement is possible – in fact it is not. Professor Treitel divides these cases into three categories. uu Cases of physical impossibility – see Sheikh Brothers Ltd v Ochsner [1957] UKPC 1. uu Cases of legal impossibility – see Cooper v Phibbs (1867). uu Cases of commercial impossibility – see Griffith v Brymer [1903] 19 TLR 434. Note that it is important, in cases where it is alleged that there is a mistake as to the possibility of performance, to ascertain from the agreement whether one party has assumed the risk of performance. If one party has assumed this risk, the party will probably be in breach of a (valid) contract. We will return to the concept of impossibility when we consider frustration in Chapter 15 of the module guide. As we will see, a contract is frustrated if performance becomes impossible because of a supervening (or later) event. Summary It is possible to regard the situations where the subject matter does not exist, or the thing is already owned by the ‘purchaser’ or situations of physical/legal/commercial impossibilities as instances where the contract is void or invalidated because it cannot be performed. It is important to note, however, that the apparent contract is only void where the mistake is of both parties. Activity 8.5 Outline the circumstances in which courts have found that performance is impossible. Activity 8.6 In Griffith v Brymer, is performance of the contract impossible or is performance of the contract radically different from that which was contemplated by the parties? Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, paras 8-012 to 8-014. 8.2.6 Mistake as to a quality of the subject matter Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.6 ‘Mistake as to quality’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 13 ‘Common mistake: initial impossibility’ – Section 3B ‘Mistakes as to quality’. This is a very difficult area of the law of mistake. The difficulty arises from the House of Lords’ decision in Bell v Lever Brothers Ltd [1931] 1 KB 557. The case presented hard facts to the court. The chairman and vice-chairman of a Lever Brothers’ subsidiary rendered exceptional services to the company but also breached their contracts of employment in such a way that the contracts were terminable at Lever Brothers’ option. Lever Brothers, unaware of this, entered into termination contracts to end the employment of the two men because Lever Brothers were amalgamating the subsidiary with another company. When Lever Brothers later learned that the employment contracts were terminable because of the behaviour of the two men they attempted to set aside the termination contracts and recover the money paid. The mistake was a bilateral mistake as to a quality of the subject matter of the contract. The subject matter of the termination contract was the employment contract and the particular quality was the terminability of the employment contract at Lever Brothers’ option. Because of their breaches of duty, Lever Brothers could have terminated the contracts of the two men without compensation. The jury found that they would have terminated the contracts page 117 page 118 University of London International Programmes without compensation and would never have entered into the termination contracts had they known of the secret trades. The House of Lords was divided 3–2 in favour of finding that the severance contracts were valid. Lord Atkin wrote the leading judgment. In it, he recognises that a mistake as to quality may render the contract void: Mistake as to quality of the thing contracted for raises more difficult questions. In such a case mistake will not affect assent unless it is the mistake of both parties, and is to the existence of some quality which makes the thing without the quality essentially different from the thing as it was believed to be. Lord Atkin then applied this test to the facts before him and found that the mistake in Bell’s case was not sufficient to render the contract void. The problem the case creates is that if the mistake was not sufficient in this case, it almost never would be. It is probably for this reason that there have been so few successful mistake cases in later years. Note that there are some older contrary authorities that do not sit easily with the decision of the House of Lords in Bell: Nicholson & Venn v Smith-Marriottc (1947) 177 LT 189 and Scott v Coulson [1903] 1 Ch 453. In the case of Associated Japanese Bank (International) Ltd v Credit du Nord SA [1988] 3 All ER 902 Steyn J (as he then was) explained the meaning and application of Bell v Lever Bros [1932] AC 161. This is an important case because it provides a comprehensive assessment of contractual mistake. Steyn J discussed Bell v Lever Bros in some detail because of the controversy surrounding the application of the case. He stated that the doctrine of mistake at common law had a narrow ambit – and one into which few cases had fallen. To an extent which has yet to be determined, this case is affected by the decision in The Great Peace (discussed below and in greater detail in Section 8.4 ‘Mistake in equity’). In The Great Peace, the Court of Appeal referred to Bell v Lever Bros with approval, although Lord Phillips MR noted the cases which Lord Atkin relied upon as support for his principles provided ‘an insubstantial basis for his formulation of the test of common mistake in relation to the quality of the subject matter of a contract’. Lord Phillips MR, in The Great Peace, appears to have made the relevant criteria for an operative mistake as to quality even more demanding than those proposed by Lord Atkin in Bell v Lever Bros. Summary Mistake as to a quality of the subject matter creates great difficulties in the common Figure 8.1 The Great Peace law of contract. Very few contracts are found to be void on the ground that there is a sufficiently fundamental mistake as to quality. It is the element of ‘sufficiently fundamental’ that proves so troublesome. This is partly because of the decisions in Bell v Lever Bros and The Great Peace and partly because it is difficult to distinguish a sufficiently fundamental quality from the assumption of a risk which worked to the disadvantage of one or both of the parties. It is because of these difficulties that courts created an equitable device to circumvent the difficulties posed by mistake at law. This device, and especially its reduced scope after The Great Peace, is discussed in Section 8.4. Contract law 8 Mistake Activity 8.7 Summarise the approach provided by Steyn J in Associated Japanese Bank (International) Ltd v Credit du Nord SA as to how cases where mistake is alleged should be resolved. Further reading ¢¢ MacMillan, C.A. ‘How temptation led to mistake: an explanation of Bell v Lever Bros.’ (2003) 119 LQR 625. Self-assessment questions 1. Write a definition of the term ’res extincta’. 2. Compare your definition of ‘res extincta’ with that of ‘consideration’. 3. In what circumstances did Lord Atkin say that consent would be negatived? 4. In what circumstances did he say it would be nullified? 5. What are the differences between these two? Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 8 ‘Mistake’. 8.3 Unilateral mistakes Courts are generally unwilling to find that a contract is void at law where the mistake is the mistake of one party only. To find the contract void would, in most instances, prejudice the non-mistaken party. Accordingly, courts will generally only find the contract void in one of two situations. uu In the first case, the non-mistaken party is aware of the other party’s mistake and proceeds to contract anyway. uu In the second case, the non-mistaken party has created the mistake to induce the (now) mistaken party to contract. The largest group of these cases are those of ‘mistaken identity’. In both of these instances, the non-mistaken party does not have any reasonable expectations to protect. In the first instance, he is aware of the mistaken assumption or promise and acts to take advantage of it. In the second instance, he has deliberately caused the mistake as to identity to form a ‘contract’ between himself and the mistaken party. In neither situation has he a reasonable expectation that the court will seek to protect. Indeed, the entire mistake has come about by reason of his inaction or by his fraud. As you consider this area, be aware of the fact that there are many cases where the contract is valid at law and yet equity may provide some relief to the mistaken party. 8.3.1 Mistaken assumptions or promises Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 2 ‘Agreement: clearing the ground’ – Section 2.1 ‘Who decides that an agreement has been reached?’ to Section 2.3 ‘The objective test’. ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 4 ‘Certainty and agreement mistakes’ – Section 4.6 ‘Mistake negativing consent’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 3 ‘Agreement problems’ – Section 2B ‘Unilateral mistake’. ¢¢ Brownsword, R. ‘New notes on the old oats’, in your study pack. In some circumstances, mistake is said to negative the consent of the mistaken party so that no contract arises. The mistake prevents the contract from arising. Importantly, the non-mistaken party must be aware of the other party’s mistake. page 119 page 120 University of London International Programmes The perplexing case of Smith v Hughes [1871] LR 6 QB 597 illustrates this proposition. The claimant sold the defendant oats after showing him a sample of the oats. The defendant mistakenly thought he was buying old oats; in fact, they were new oats. The claimant had done nothing to induce this mistake and was unaware of it. The Court held that for a mistaken assumption or promise of one party to be sufficient to vitiate a contract (to render it void) the mistake must be known to the other party and it must be a mistake as to what is promised. Thus, in Smith v Hughes, the contract would have been void only if two factors were present. First, if the defendant had been mistaken as to the promise made to him by the claimant. In this case the promise would have been as to the age of the oats. Second, that the defendant knew about the claimant’s mistake as to the nature of the promise made to him by the defendant (sometimes described as a mistake as to terms). As you will see in your readings, while the law appears to require a subjective intention in these cases (that is to say, what is actually in the minds of these parties), it is in fact taking an objective approach (that is to say, what would be in the minds of reasonable parties in these circumstances). Where the mistake is as to an assumption or as to a promise, courts rarely find that the mistake is operative – that is to say, that, because of the mistake, no contract has been created. The entire area displays the extent to which the common law of contract is rooted upon the principle of caveat emptor (let the buyer beware). As long as one party does not misrepresent a state of affairs or defraud the other party, courts will generally find the consensus, the agreement, between the parties which is necessary to form a contract. Indeed, courts will be very reluctant to disrupt an apparent contract in these circumstances, for to do so would be to write the contract for the parties. In some instances, however, it is so readily apparent to the one party that the other is proceeding upon a mistaken basis that the court will find that the apparent contract is void. These are cases where one party ‘snaps’ at the obviously mistaken offer of another. A always sells B grain at a price of x per pound. One day, A offers to sell B grain at x per ton. B, realising that A has made a mistake, snaps at A’s offer and ‘accepts’ immediately. This is a case where the mistake is operative – the mistake negatives A’s consent in such a way that there is no contract. Note that: (i) B is aware of A’s mistake and (ii) B’s conduct is such that it is unconscionable or inequitable for him to hold A to a contract. The cases of Hartog v Colin and Shields [1939] 3 All ER 566 and Centrovincial Estates plc v Merchant Investors Assurance Co Ltd [1983] Com LR 158 illustrate this proposition and were discussed earlier in Chapter 2, Section 2.1.1. Summary This is not an easy area to understand. The mistake of one party is generally not enough to avoid the contract. The mistake must be known to the other party. For the contract to be void, it is not sufficient that the promisor realises that the promisee is mistaken as to an important element of the contract. The promisor must realise that the promisee is mistaken and that he is mistaken as to the promise made by the promisor. It may be that this oddity arises because of the nature of the contract in Smith v Hughes – where the sale of the oats was made by sample. The defendant had examined a sample of the oats when he placed the order. In the circumstances, the only reason that the contract would be void was if the promisor’s conduct verged on the fraudulent – in not explaining to the promisee that he was mistaken about the promise. Courts will usually allow the contract to be avoided for a unilateral mistake in circumstances where the behaviour of the non-mistaken party is such as to indicate that he has no reasonable expectation to protect. Where the non-mistaken party’s actions are such as to indicate that he seeks to take advantage of the mistaken party, there is no reasonable expectation to protect. In other words, a non-mistaken party who ‘snaps’ at the mistaken offer of another will not reasonably have thought the mistaken offer was a legitimate one. Contract law 8 Mistake Activity 8.8 Ace Sportscards hires a new assistant, Blob. Blob places various cards in the shop window and places prices below the cards. He knows nothing about sports cards and places the wrong price tag below some cards. He prices a 1979 Wayne Gretzky rookie card at $5 – the card is worth $500. Crafty, passing the shop, notices the card and enters the shop. He offers Blob $20 for the card; Blob notes the price below it and sells the card to him for $5. Blob later realises his error; Ace Sportscards ask you if there is a contract with Crafty. Activity 8.9 A and B are art collectors. A has a picture that may be an Emily Carr. A offers to sell it to B. Consider the following problems. Distinguish between them and note whether, in any or all of them, a contract arises. a. A says to B: ‘It’s a Carr all right’, whereupon B buys the picture. It is not a Carr. b. A (mistakenly) believes the painting to be a Carr and tells B that it is a Carr whereupon B purchases it for £500,000. c. A thinks it is a ‘school of Carr’ picture, but B thinks it is an original. d. Same as (c) but A knows B thinks it is an original. e. B thinks A is warranting the picture as original. A knows this, and has no intention of warranting it. 8.3.2 Mistakes as to identity Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 4 ‘Certainty and agreement mistakes’ – Section 4.6 ‘Mistake negativing consent’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 3 ‘Agreement problems’ – Section 2C ‘Unilateral mistake as to identity’. This area of law has received recent clarification from the House of Lords in the case of Shogun Finance v Hudson [2003] UKHL 62. Prior to this decision, there was some uncertainty as to the application of a doctrine of mistake as to identity. Virtually all mistake as to identity cases arise as the result of the fraudulent actions of a wrongdoer, the ‘rogue’. In the typical situation a rogue presents himself to an innocent vendor and offers to purchase a good. The rogue deceives the vendor as to his identity. The vendor sells the goods to the rogue and the rogue departs with the goods. The vendor is usually given a cheque which is not honoured. When the vendor seeks the return of the goods from the rogue, he discovers: a. the rogue for what he is b. that the rogue has vanished c. that the rogue has sold the goods to an innocent third party. The court is thus faced with litigation between the (deceived and mistaken) vendor as claimant and the (innocent) third party as defendant in which the claimant seeks the return of his goods. The court must decide which of these two ‘victims’ will bear the cost of the rogue’s deception. If the contract between the rogue and the vendor is good, the cost will be borne by the vendor because by this contract, the rogue acquired good title to the goods and could sell them on to the third party. If the contract between the rogue and the vendor is void, the cost will be borne by the third party because the rogue never acquired title to the goods. The vendor thus recovers his goods from the third party. A decision, as required here, as to which of two victims should bear the full consequences of a fraud perpetrated by a third party will always be a difficult one. This difficulty prompted a suggestion from Devlin LJ in Ingram v Little [1961] 1 QB 31 that a mechanism should be found whereby the loss was effectively shared by these two parties. The suggestion has never been acted on. page 121 page 122 University of London International Programmes You must also note that in these circumstances, misrepresentation is also involved. In the above circumstances, the rogue induced the contract by a misrepresentation. If the contract is not void for mistake, it is voidable for misrepresentation. However, the vendor must then set aside or rescind the contract before the innocent third party contracts with the rogue. If he does not, the first contract can no longer be set aside because of the involvement of the third party’s rights. That is to say, if the third party contracts with the rogue before the contract between the rogue and the vendor is rescinded, then the vendor loses the right to rescind the first contract. This matter will be examined further in the next chapter on misrepresentation in Section 9.2.1. In most mistaken identity cases, the policy arguments will favour protection of the third party. The vendor assumed a normal commercial risk in selling on credit, or accepting a payment by cheque. Because it was the vendor’s choice to assume this risk, there is no valid reason why he should be able to pass the resulting loss on to the third party. This reasoning is less convincing when the third party appears to buy the goods at undervalue. Such a sale should perhaps make the purchaser suspicious. In Lewis v Averay [1973] 2 All ER 229 the sale to the rogue was for £450 but the rogue’s sale of the same property to the ‘innocent’ third party was for £200. The House of Lords in Cundy v Lindsay [1878] 3 App Cas 459, however, found differently. In this case, the rogue presented himself in such a way as to appear to be a legitimate firm. The innocent party thought that they were dealing with a legitimate firm and shipped the goods to the rogue. In these circumstances the House of Lords found that the contract was void because there was a lack of consensus. Cundy v Lindsay thus operates to establish the proposition that: 1. if A thinks he has agreed with C because he believes B, with whom he is negotiating, is C; and 2. if B is aware that A did not intend to make any agreement with him; and 3. if A has established that the identity of C was a matter of crucial importance, 4. then the contract will be void. Note that identity must be material to the formation of the contract: Dennant v Skinner [1948] 2 All ER 29. Later courts often found that in seemingly similar circumstances there was a contract. Thus, a mistake as to the attributes of identity (such as creditworthiness) will generally be insufficient to render the contract void: see King’s Norton Metal Co v Edridge [1897] 14 TLR 98. In addition, in some circumstances the contract is made inter praesentes – that is to say face-to-face – and the vendor meets the rogue and contracts with him. In these cases, courts have frequently said that the rogue is identified by ‘sight and hearing’: see Phillips v Brooks [1919] 2 KB 243 and Lewis v Averay [1972] 1 QB 198. Where the parties are before each other, a presumption arises that the mistaken/deceived party intended to contract with the person before him and a contract has arisen. The existence of such a presumption has been doubted in the past, but it was accepted by the majority of the law lords in Shogun Finance v Hudson. In Shogun Finance v Hudson a rogue entered into a written contract of hire purchase with Shogun Finance to purchase a vehicle on credit. The rogue fraudulently assumed the identity of another person. The majority of the law lords found that in these circumstances, identity was critical to Shogun Finance because it was necessary for them to check the credit rating of their potential borrowers. The apparent contract was a nullity due to the mistake of identity and an absence of consensus. The majority also approved of a presumption that in the face-to-face cases the party deceived intended to deal with the person physically before him and the result is the formation of a voidable contract. The presumption may be rebutted. Shogun Finance, however, was not a case of a face-to-face transaction and the presumption did not arise. A further effect of this decision is that it is unlikely that the Court of Appeal’s decision in Ingram v Little (1961) will be followed in the future. Contract law 8 Mistake The dissenting law lords disapproved of drawing a distinction based on whether the rogue’s fraud was perpetrated in writing or face-to-face. The dissenting law lords were concerned with the effect of fraud upon contractual formation. They also sought to give coherence to an uncertain area of law. Consequently, they disapproved of Cundy v Lindsay and what they viewed as an untenable distinction based on the method by which the rogue perpetrated his fraud. Both dissenting law lords believed that in these circumstances of mistaken identity a voidable contract arose. Summary In reviewing this area, you should keep in mind the distinction between contracts formed between the parties face-to-face and contracts formed at a distance. Where the apparent contract is formed at a distance, and probably in some form of writing, it is likely that the apparent contract is void for mistake. For this to occur, however, the identity of the party must be critical in the formation of the contract. Where the contract is formed between parties who appear before each other, a presumption arises that the mistaken party intends to contract with the person before him. The result is a contract which is voidable at the option of the mistaken party. It is uncertain at this stage what is necessary to rebut this presumption. Activity 8.10 What were the practical and commercial concerns of the dissenting law lords in Shogun Finance v Hudson? Activity 8.11 M sends an order for goods to N on paper which is headed ‘Greenhill & Co’ and shows a picture of a large factory. N sends the goods on credit. Greenhill & Co does not exist. M resells the goods to P and then disappears. Advise N. Activity 8.12 Suppose the rogue pretends to be a person who has (unknown to the parties) already died – would the contract be void or voidable? Activity 8.13 Does it matter if the rogue pretends to be a fictitious person or assumes the identity of a real person? Further reading ¢¢ MacMillan, C.A. ‘Rogues, swindlers and cheats: the development of mistake of identity in English contract law’ (2005) 64 CLJ 711. 8.3.3 Documents signed under a misapprehension as to their contents Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 9 ‘The sources of contractual terms’ – Section 9.3 ‘Bound by your signature?’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 3 ‘Agreement problems’ – Section 3B ‘The plea of non est factum’. Clearly a person must normally take full responsibility for their signature and it is up to them to make sure that they appreciate what they are signing. Exceptionally, however, a person may have been so seriously misled that the document is held to be void under the defence of non est factum (‘it is not his deed’). See Gallie v Lee [1971] AC 1004 where the House of Lords rejected the previous test, based upon a distinction – apparently certain but really meaningless – between contents and character, in favour of an openly flexible criterion. The defence is available to a person who signed the documents with a fundamental misapprehension as to the substance of the document – provided that the person who signed the documents took all due care. You will note that the burden of proof lies on the signer to show that he was not negligent – and this is a burden he will normally be unable to discharge. page 123 page 124 University of London International Programmes A rare successful plea of non est factum was Trustees of Beardsley Theobalds Retirement Benefit Scheme v Yardley [2011] EWHC 1380 (QB) by a party who signed as a guarantor of a lease to his employer after he was led to believe that his signature was necessary only to witness the signatures of others. 8.4 Mistake in equity Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.7 ‘Mistake in equity’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 3 ‘Agreement problems’ – Section 3A ‘Rectification’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 13 ‘Common mistake: initial impossibility’ – Section 3B ‘Mistakes as to quality’. Mistake in equity is not an easy topic to study and there is, at present, considerable uncertainty as to whether or not a contract can be avoided in equity. The uncertainty arises from the decision in The Great Peace. 8.4.1 The end of the equitable jurisdiction to set aside on terms We have seen that the doctrine of common mistake at law operates within narrow boundaries. In the past this strict and ungenerous (i.e. to relief) approach at common law has mitigated the courts’ ability to set aside a contract in equity where there was a common mistake, but not one which is of sufficient importance to render the contract void at law. In Solle v Butcher [1950] 1 KB 671, the Court of Appeal stated that the House of Lords in Bell v Lever Bros was only concerned with mistake at law and not in equity. Lord Denning then recognised a more flexible doctrine of equitable mistake. As this equitable doctrine was the exercise by the courts of a power to set aside a contract the court could do substantial justice between the parties by imposing conditions when exercising the power. An example of its exercise was Grist v Bailey [1967] Ch 532 where a house was sold for £850 in the mistaken belief that it was occupied by a protected tenant. The tenant had, unknown to the parties, died and so, without a sitting tenant, the house was worth £2,250. The sale was set aside subject to the condition that the owner should offer it for sale to the disappointed buyer at the full market value. There was, however, an uneasy relationship between mistake at law and mistake in equity. It was in this context that the Court of Appeal gave their decision in The Great Peace. The case involved two ships. The Cape Providence suffered structural damages and it was feared that she might sink. The defendant was hired to salvage the Cape Providence. To this end, they contracted with the claimant that the claimant’s ship, The Great Peace, would travel to the Cape Providence to escort the vessel and stand by for the purpose of saving lives. At the time the defendant approached the claimant, the defendant (and from them the claimant) mistakenly believed that the ships were 35 miles apart. Shortly after the contract was concluded, the defendant discovered that the ships were 410 miles apart. After they had procured a closer substitute ship, the defendant refused to perform their contract with the claimant. At trial, the defendant asserted that the contract was void for mistake at law or voidable in equity by reason of mistake. The trial judge denied this assertion. On appeal, the Court of Appeal considered the extent of the doctrine of mistake in equity. The Court of Appeal extensively reviewed the cases of Bell v Lever Bros and Solle v Butcher. The concept of mistake in equity was considered both before and after Bell v Lever Bros. Lord Phillips MR concluded that it was impossible to reconcile the two cases. Bell v Lever Bros prevailed; Solle v Butcher was disapproved. The House of Lords in Bell v Lever Bros had not overlooked an equitable right to rescind an agreement which was valid at law. There was no such equitable right and accordingly no separate doctrine of mistake in equity existed to provide relief for a common mistake as to a Contract law 8 Mistake quality of the subject matter of the contract. In the case before them, the difference in the proximity between the two ships as they were believed to be and as they actually were was not a sufficiently fundamental mistake to render the contract void. The contractual venture could still be performed. Accordingly, the appeal was dismissed: the defendant was liable under the contract to pay the cancellation fee to the claimant. In Pitt v Holt [2013] UKSC 26, the Supreme Court stated that The Great Peace had ‘effectively overruled’ Solle v Butcher. 8.4.2 Rectification Equitable relief takes three principal forms. The first is rectification and this is a remedy which is concerned with correcting a mistake which occurs not in the making of the agreement, but in the recording of the agreement. There is little difficulty in ascertaining the principles of this form of relief. The possibility of rectification exists where a written contract or deed fails to express the common intention of the parties. What is important in relation to rectification is that it exists where the mistake is made in the recording of the agreement only. Thus, if A and B negotiate the price of their contract in American dollars, agree on a price in American dollars, but then wrongly provide the price in Canadian dollars in their written contract, the written contract can be ‘rectified’ or fixed to accord with their actual agreement. Note that the mistake must be in the recording of the agreement (e.g. in the documents relating to the negotiation). In Chartbrook v Persimmon Homes Ltd [2009] UKHL 38 the House of Lords held that if the parties had a common continuing intention, objectively assessed, in respect of which rectification was sought, it would be granted. It had to be shown, to receive rectification, that the parties were in complete agreement as to the terms of their contract but that, by an error, incorrectly recorded them. Where the evidence suggests that the parties did agree upon the terms in the contract it is not relevant to a plea for rectification that the claimant misunderstood the meaning of those words. See FE Rose (London) Ltd v William Pim Jnr & Co [1953] 2 QB 450. Exceptionally even a unilateral mistake may be a sufficient basis for rectification where it is known to the other party and that party ‘unconscionably’ fails to draw the mistaken party’s attention to it (Commission for the New Towns v Cooper [1995] 2 EGLR 113), though the Court of Appeal in George Wimpey UK Ltd v VI Components [2005] All ER (D) 272 has said that such cases will be rare. Because rectification is an equitable device the usual restrictions as to its application apply. Such restrictions encompass matters such as a lapse of time (a claim for rectification will be barred when a period of time has elapsed), or the intervention of third party rights (a claim for rectification cannot be made against a bona fide purchaser for value without notice of the mistake) or the conduct of the party who seeks rectification (it is an equitable maxim that he who comes to equity must come with clean hands). In DS-Rendite-Fonds Nr 106 VLCC Titan Glory GmbH & Co Tankschiff KG v Titan Maritime SA [2013] EWHC 3492 (Comm) the court held that an entire agreement clause in a contract was not a bar to rectification. 8.4.3 Specific performance The remedy of specific performance is discussed in Chapter 17. It has its origins in the jurisdiction of the Lord Chancellor, subsequently exercised by the Chancery Division of the High Court, to supplement the remedies available in other courts. The origin of this jurisdiction in the chancery or equity courts has a consequence for its availability today because the principal characteristic of equitable relief is that it is discretionary. To the extent that the exercise of this discretion is influenced by the existence of a mistake it may be thought of as part of the law of mistake. See, for example, the contrasting cases of Denny v Hancock [1870] 6 Ch App 1 and Tamplin v James [1880] 15 Ch D 215. page 125 page 126 University of London International Programmes Summary Since the Court of Appeal’s decision in The Great Peace the jurisdiction to set aside a contract in equity, previously associated with Solle v Butcher, a jurisdiction no longer exists. Rectification is, thus, concerned with mistakes in the recording of the agreement rather than in the making of the agreement. A court of equity may refuse to grant an order for specific performance in circumstances where a mistake is present. Equitable relief is in all cases discretionary and so may be excluded by various circumstances sometimes called bars (e.g. excessive delay, where restitution is impossible and where there is an intervention of an innocent third party purchaser). These factors are discussed further in Chapter 9, Section 9.2.1. Activity 8.14 Victor sells a painting to Peter, an art expert, for £50. It is in fact a masterpiece worth £50,000. To what extent, if any, can a court grant equitable relief? Further reading ¢¢ Chandler, A., J. Devenney and J. Poole ‘Common mistake: A theoretical justification and remedial inflexibility’ (2004) JBL 34. Examination advice Refer to the examination advice given at the conclusion of Chapter 1 of the module guide. With regard to mistake questions generally, you are well advised to follow the approach of Steyn J in Associated Japanese Bank v Credit du Nord [1989] 1 WLR 255 subject to the decision in The Great Peace on the availability of relief in equity. That is to say, consider first whether or not the contract is void at law. It may assist you if you try to consider what type of mistake exists in the given situation and compare it to decided cases where the mistake was found to be operative. Sample examination question Hammer, an auctioneer, sold a collection of paintings by auction. Each painting was fully described in the catalogue. When Hammer invited bids for Lot 15 – described as ‘Country Scene, artist unknown’ – his assistant Mallet inadvertently held up Lot 16 instead for the bidders to see. Lot 16 was described in the catalogue as ‘Village Life, (?) school of Brushman’, but Sickle, who was sitting in the front row, immediately recognised it as a lost masterpiece by Brushman himself. No other bidders noticed Mallet’s error and Sickle’s bid of £25 was accepted by Hammer. When Hammer realised what had happened he refused to let Sickle have the painting, which is worth £5,000. Advise Sickle. Advice on answering the question Begin by considering the position at law. What sort of mistake has been made here? Two mistakes have been made. First, the wrong painting has been exhibited by Hammer’s assistant, Mallet. Hammer is inviting bids for Lot 15, but Lot 16 has been exhibited. It is possible to argue that Sickle is bidding on Lot 16. Following this argument, no contract is made by reason of the decision in Raffles v Wichelhaus [1864] 159 ER 375 – the parties are at cross-purposes; the offer and acceptance do not correspond. In the circumstances, no contract can arise. The weakness with this argument is that the painting has been displayed and Sickle will undoubtedly argue that it was the painting before him which was bought and sold. If the mistake is only of Hammer, it is a unilateral mistake. Generally, the law will not avoid a contract where the mistake is unilateral only. Here, however, it is possible to argue that Sickle has ‘snapped’ at a mistaken offer by Hammer. There is support for this proposition in Hartog v Colin and Shields (1939): on these grounds, the contract is avoided. Sickle has no reasonable expectations which can be protected. The weakness of this argument Contract law 8 Mistake is that there is a double mistake here by Hammer – even if he held up the painting as a part of the right lot, he seems uncertain as to what sort of painting he has. In other words, his offer may not be as mistaken as it first appears. If the mistake is viewed as a common mistake, the contract is unlikely to be avoided because of the decision in Bell v Lever Bros. The painting is the same painting in each case, the artist is only a quality of the subject matter of the painting. It may be possible, using the decision in Nicholson & Venn v Smith-Marriot, to argue that it is by this quality that the painting is identified. This is, however, a weak argument since Hammer is himself confused as to who the artist is (even if he examined the painting as the right lot). It is likely, on balance, that the contract would be avoided on the principles set out in Hartog v Colin and Shields (1939). This result is by no means certain and so the position must also be considered in equity. In equity, following The Great Peace, the court has no ability to rescind the contract on the grounds of mistake in equity. Quick quiz Question 1 Which of the following statements is a definition of common mistake at common law? a. This is where the parties have made a contract about something which has ceased to exist at the time the contract was made. b. This is where the parties are at cross purposes, but neither side is aware of this when they contend they have made a contract. c. This is where the agreement is negatived because one party is aware that the other is mistaken about an aspect of the contract. d. This is where the parties were under a common misapprehension either as to facts or as to their relative and respective rights, provided that the misapprehension was fundamental, and that the party seeking to set it aside was not himself at fault. e. Don’t know. Question 2 If one party (A) buys a car from another party (B) in person and pretends to be (Q) a famous actor, and pays with a cheque, which is then not honoured, which statement best represents the view the court is likely to take when the car has been sold on to a third party (C)? Choose one answer. a. The court will decide that as the contract was between A and B then C will have to return the car to B and sustain the loss. b. The court will decide that as the contract between A and B was voidable, then C will not have to return the car to B and so B will have to sustain the loss. c. The court will decide who is in the strongest bargaining position between A and C before reaching a just and equitable conclusion. d. The court will decide that the car should be sold and all proceeds should be split equally between A and C. e. Don’t know. page 127 page 128 University of London International Programmes Question 3 Which ONE of the following examples of mistakes as to quality might allow a contract to be avoided for a mistake as to quality? Choose one answer. a. Where the complainant purchased oats believing them to be ‘old’ oats rather than ‘new’ oats. b. Where both parties to the sale of a car believe the car to be a 1948 model rather than a less valuable 1939 model. c. Where both parties to the sale of a painting believed the painting to be by the famous artist Constable. d. Where a set of table napkins described as being the property of Charles I were in fact Georgian. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Which of the following is not available as equitable relief for mistake? Choose one answer. a. Rectification of the contract. b. Rescission of the contract. c. Equitable damages for the mistaken contract. d. Refusal of an order for specific performance. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Which statement best summarises the relationship between mistake and misrepresentation? Choose one answer. a. All misrepresentations involve a mistake. b. All misrepresentations involve a mistake but a misrepresentation also involves an element of fault. c. All mis-statements are actionable as either misrepresentations or mistakes. d. All mis-statements are actionable as either misrepresentations or mistakes and it is left to the claimant to decide which action to bring. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Contract law 8 Mistake Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is contractual mistake? 2. What are the effects of mistake compared with the effects of misrepresentation? 3. What is the difference between bilateral and unilateral mistake? 4. What relief will a court provide for an operative mistake in law and in equity? 5. What are the limits of the doctrine of mistake? 6. What is meant by an agreement mistake? 7. What are the circumstances in which an agreement mistake will operate? 8. What is a mutual or common mistake? 9. In what circumstances have courts found a mutual or common mistake to be operative? 10. What is the basis for finding a contract void where a mutual or common mistake operates? 11. What is a sufficiently fundamental mistake as to a quality of the subject matter? 12. In what circumstances will courts find that a contract is void where the mistake is a unilateral mistake? 13. What, if any, is the effect of a mistake as to identity? 14. In what circumstances will courts find a mistake as to identity is operative? page 129 page 130 Notes University of London International Programmes Part IV Vitiating elements in the formation of a contract 9 Misrepresentation Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132 9.1 Definition of misrepresentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133 9.2 Remedies for misrepresentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138 9.3 Exclusion of liability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147 page 132 University of London International Programmes Introduction This chapter is concerned with the effect of express statements made prior to entering into a contract. These statements may become terms of the contract or they may be ‘mere’ representations (i.e. representations only). If they are terms of the contract then a remedy lies for breach of contract should they prove to be false. Technically a remedy for misrepresentation will also be available but may, in many instances, be less valuable to the claimant than the action for breach. If they are ‘mere’ representations then, should they prove to be false, the only remedies available are those for misrepresentation. An actionable misrepresentation is an unambiguous false statement of existing fact or law which induced a party to enter into the contract. In a limited number of circumstances a failure to disclose a matter may also be treated as a misrepresentation. The potential remedies for a misrepresentation are a rescission of the contract and damages. The right to rescind, as an equitable remedy, can be lost. The amount of damages, if any, will depend upon the nature of the misrepresentation, which we explore below. Damages may be available at common law for the torts of deceit or negligent misstatement. The Misrepresentation Act 1967 also provides that damages may be awarded for a misrepresentation. Where a party attempts to exempt liability for a misrepresentation this attempt will generally be subject to the test of reasonableness in the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 by virtue of the Misrepresentation Act 1967 s.3. However, s.3 will not apply to a contract between a trader and a consumer which will be subject to a test of fairness under the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (s.62 and Schedule 4) which was discussed in Chapter 6, Introduction and Section 6.2. Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 12 ‘A duty to disclose material facts?’. ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 13 ‘Misrepresentation’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 6 ‘Content of the contract and principles of interpretation’ – Section 1 ‘Pre-contractual statements: terms or mere representations?’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 14 ‘Misrepresentation’ – Section 1 ‘Actionable misrepresentation’. ¢¢ Hooley, R. ‘Damages and the Misrepresentation Act 1967’ (1991) 107 LQR 547–51, available through the Online Library. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the effect upon an otherwise valid contract of a misrepresentation made prior to the entering of a contract to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The definition of a misrepresentation including when a statement of opinion or intention will be actionable. uu The requirements of the different claims to damages for misrepresentation. uu The requirements of the remedy of rescission for misrepresentation. uu The comparative advantages of the different remedies available for misrepresentation. uu What are the potential remedies for misrepresentation. uu The limits placed upon the exclusion of liability for misrepresentation. Contract law 9 Misrepresentation 9.1 Definition of misrepresentation For the reasons discussed in the Introduction above it is important to know whether a statement made in negotiations becomes a term of any subsequent contract. The principles that determine the answer to this question were discussed in detail in Chapter 5, Section 5.1. It is essential that you familiarise yourself with these again. In any examination answer there is a danger that if you wrongly classify a statement made in negotiations as either a term or a ‘mere’ representation this will lead you to discuss the wrong set of remedies available to the victim when the statement later turns out to be untrue. Therefore it is important to begin by distinguishing between statements which are mere representations and statements which become terms of the contract. 9.1.1 Misrepresentation and contractual terms Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 8 ‘What is a term?’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 6 ‘Content of the contract and principles of interpretation’ – Section 1 ‘Pre-contractual statements: terms or mere representations?’. As explained in Chapter 5 of this guide, the determination of whether or not a precontractual statement was a term of the contract was important before 1967 for a different reason than it is now. Prior to 1967 uu the remedies for misrepresentation were limited; and uu when a misrepresentation was incorporated as a contractual term the remedy of rescission for misrepresentation was lost. As a consequence, parties went to great lengths to persuade courts that statements were intended to be terms in order to secure a remedy. Both of these factors were changed by the Misrepresentation Act 1967. There are now much more extensive remedies in damages available for misrepresentation (under s.2 of the Act) and s.1(a) provides that a contract may be rescinded for misrepresentation, even if the misrepresentation is also a term of the contract. The question, however, is still of great importance. If, for example, the pre-contractual statement is in the form of a promise rather than a statement of fact then a remedy for misrepresentation is unlikely to be available. The only possible argument for the claimant will therefore be to show that the statement had become a term of the contract. For further full discussion of the way in which statements may become part of a contract, see Chapter 5, Section 5.1. 9.1.2 Unambiguous false statement of existing fact or law which induces a contract Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 13 ‘Misrepresentation’ – Section 13.1 ‘Introduction’ to Section 13.5 ‘Inducement’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 14 ‘Misrepresentation’ – Section 1 ‘Actionable misrepresentation’. ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 12 ‘A duty to disclose material facts?’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 14 ‘Misrepresentation’ – Section 1A ‘Unambiguous false statement’. For a misrepresentation to be actionable it must be an unambiguous false statement of existing fact or law. page 133 page 134 University of London International Programmes Unambiguous As with contractual terms a degree of certainty is required. If a party is to prove they have an actionable claim it must be that the term is sufficiently clear. So in Dimmock v Hallett [1886] LR 2 Ch App 21 where the land was described as ‘improvable’ this statement was held to be ambiguous; therefore not actionable. False One issue is when the statement is, on a strict and literal interpretation of the words, true, but misleading. Is the statement false within the requirements of making a claim for misrepresentation? In Dimmock v Hallett (1866) a statement made pre-contract was that the land was ‘let to paying tenants’, which at the time was literally true. However, what the seller did not go on to say is that before the sale the tenants had given notice. This can perhaps be a halftruth. It is clear that the statement, unless explored further by the purchaser, would lead the reasonable person to believe the set of facts continued. Secondly, where a statement, which was true when made, becomes false as a result of a change of circumstances, keeping silent may be treated as a misrepresentation: see With v O’Flanagan [1936] Ch 575 and Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV [2000] EWCA Civ 15. In both these cases a representation (respectively as to the profits being made by a medical practice and the continuing membership of a pop group) were true when made but, due to a change of circumstances, became untrue thereafter but before the relevant contract was signed. Both cases treated the statement as a ‘continuing representation’ by virtue of which, when the change of circumstances occurred, the representor was at that moment treated as making an untrue statement of existing fact. Statement In English contract law there is no general duty to disclose facts (Keates v Earl of Cadogan [1851] 138 ER 234) based on the principle of caveat emptor (let the buyer beware). However, in certain circumstances silence has been found to amount to a ‘statement’. A different rationalisation of the successful claims in With and the Spice Girls cases above is that the parties’ silence or inaction in the face of the changed circumstances was actionable. There are some contracts which are treated as being ‘of the utmost good faith’ (or uberrimae fidei). This means that parties are obliged to disclose relevant information, even if it is not asked for. The most common example of this type of contract is a contract of insurance. The insurer will normally be entitled to rescind the contract if any information relevant to the risk insured is not disclosed, whether or not this has been asked for: see, for example, Lambert v Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd [1975] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 485. There is no general duty when entering into a contract to disclose information so this application is very limited. Recent cases have contained discussions of the desirability of a more general duty upon contractors to act in good faith extending beyond the negotiation of a contract. Leggatt J has been an enthusiastic supporter (Yam Seng Pte Ltd v International Trade Corp Ltd [2013] EWHC 111 and Novus Aviation Ltd v Alubaf Arab International Bank BSC [2016] EWHC 1575 (Comm)), although this enthusiasm has not been echoed in recent appellate decisions (Mid Essex Hospital Services NHS Trust v Compass Group UK and Ireland Ltd [2013] EWCA Civ 200 and MSC v Cottonex Anstalt [2016] EWCA Civ 789). See also Monde Petroleum SA v Westernzagros Ltd [2016] EWHC 1472 (Comm) holding that an express right to terminate a contract did not need to be exercised in good faith. Conduct A statement may be express but may also be made by conduct. In Spice Girls the group’s conduct in continuing to participate in promotional activity constituted a representation that they were not aware that the membership of the group would soon change (Geri Halliwell had in fact already informed the others of her intention to leave the group). Contract law 9 Misrepresentation Fact or law A statement of opinion is not generally a misrepresentation – see Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177. Two exceptions exist. The first is where the person expressing the opinion is aware of facts which indicate that the opinion cannot be sustained. Thus, in Smith v Land House Corporation [1884] 28 Ch D 7 a tenant who, the landlord knew, was behind with the rent could not be described as a ‘most desirable tenant’. The landlord’s statement to this effect was therefore a misrepresentation. Where the representor has particular expertise in relation to the thing said the inference that the representor is aware of facts that support his opinion is more easily raised. On this basis an estimate by an oil company of the future sales that could be expected from a particular petrol station site was held to imply a representation that the oil company was aware of facts (e.g. sales from equivalent venues) that would support this estimate (Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] QB 801). The second exception, which can lead to a statement of opinion being treated as a false statement of fact, is where there is evidence that the person making the statement does not believe it at the time that it is made. Proof that the maker of the statement was aware of contradictory facts may prove that they did not believe the statement was true. See Edgington v Fitzmaurice [1885] 29 Ch D 459, where it was held that the ‘state of a man’s mind is as much a fact as the state of his digestion’. The fact falsely stated in these cases is the speaker’s state of mind. The speaker represents the fact that he or she believes that what is being said is true, whereas in fact no such belief is held. The Edgington v Fitzmaurice approach can also be used to turn statements of intention into misrepresentations, if at the time of making the statement, the person did not have the stated intention. This was, in fact, the situation in Edgington v Fitzmaurice itself in respect of a statement made in a company prospectus that the purpose of soliciting investments in the company was to expand the business when the real motivation was to pay off accrued debts. As the representors, at the very moment they proclaimed their intention, did not in fact have this intention, they were taken to have misrepresented a present existing fact, the state of their mind. For as Bowen LJ remarked ‘the state of a man’s mind is as much a question of fact as the state of his digestion’. Traditionally, statements of law were not regarded as being statements which, if false, will give rise to remedies for misrepresentation. It seems, however, that now that the House of Lords has recognised the possibility of restitutionary remedies for mistake of law (in Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Lincoln City Council [1999] 2 AC 349), the same approach may well apply in the area of misrepresentation. This was the view of the High Court in Pankhania v Hackney London Borough Council [2002] EWHC 2441. In any case, if the statement of law is not believed by the person making it, then the principle in Edgington v Fitzmaurice will apply, so that the statement will be treated as a misrepresentation of the person’s state of mind. Activity 9.1 Consider whether any of the following statements is capable of being a misrepresentation. a. X, who is selling his car, tells a prospective purchaser that the tyres are ‘good for another 3,000 miles’. In fact, the tyres need replacing after another 1,000 miles. b. Y, a salesman for XLO Computer Services, tells a prospective customer that all XLO’s service engineers are trained ‘to the highest standards, including six weeks on the job under supervision’. In fact, the supervised period is only five weeks. c. A new CD is stated on posters displayed in music stores to be ‘The Best Garage Album in the World… Ever!’. Reviews of the CD in the music press are universally hostile. Which induces the contract In order for a misrepresentation to be actionable, it must induce the person to whom it is addressed to make a contract. This simply means that the statement must be one page 135 page 136 University of London International Programmes of the factors which led the person to enter into the contract – it does not have to be the sole or main reason (Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885)). It is not sufficient, however, for the claimant to demonstrate that ‘he was supported or encouraged in reaching his decision by the representation in question’ (see Raiffeisen Zentralbank Osterreich AG v Royal Bank of Scotland plc [2010] EWHC 1392 (Comm)). The representation must play a real and substantial part of the claimant’s decision to enter into the contract. Where a misrepresentation is made by A to B and subsequently B enters a contract with A it is presumed that A’s misrepresentation induced B to enter the contract unless A can prove one of the following: The representee was aware of the untruth of the statement This must be proved strictly. It does not matter that the claimant had the opportunity to discover the untruth of the statement but did not take the opportunity. In Redgrave v Hurd [1881] 20 Ch D 1 the purchaser of a solicitor’s practice had the opportunity to consult documents which would have revealed the falsity of the seller’s statement about the practice’s income. His failure to do so did not preclude his later claim based on misrepresentation. Obiter comments in Smith v Eric S Bush [1990] 1 AC 831 suggest that in certain situations it may be unreasonable not to check, perhaps in commercial or high value transactions. However, treat these comments with caution as the general rule of Redgrave v Hurd is difficult to dislodge. The representee relied upon some other inducement Where the representee who was not aware of the untruth of the statement relies completely upon some other inducement for which the representor is not legally responsible, there is no causal link between the misrepresentation and the representee’s loss. So, in Attwood v Small [1838] 160 ER 633 statements were made by the vendor about the output of a mine. The purchaser sent his agent and the vendor’s statements were supported by the purchaser’s agents. In a claim to rescind for fraud the House of Lords rejected the claim as it was the statements of the agent which had induced the contract, rather than the vendor’s. The ‘representee’ was not aware of the misrepresentation In Horsfall v Thomas [1862] 158 ER 813 the claimant sold a gun which exploded when fired because a metal plug had been used to conceal a defect in the gun’s barrel. The use of such a plug could have amounted to a representation by conduct that the barrel was sound and free of defects. However, as the defendant did not inspect the gun he was not aware of the misrepresentation and so it could not be said to have induced him to purchase it. The representee would have entered the contract even if aware of the untruth To come within this category the representor must prove, not merely assert, that the representee would have entered the contract even if he had been in possession of the full facts (Atlantic Lines & Navigation Co Inc v Hallam Ltd (The Lucy) [1983] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 188). A further requirement is sometimes stated, which is that the misrepresentation, to justify rescission, must be a ‘material’ one (i.e. one upon which a reasonable person might have relied). The requirement of materiality is now best thought of as relevant only to the burden of proof in relation to inducement (Museprime v Adhill [1990] 36 EG 114). In the usual situation the misrepresentation will be a material one (i.e. one upon which the representee might reasonably rely) and, as described above, inducement is presumed unless the representor is able to prove otherwise. However, where the misrepresentation is not a material one (i.e. it is one upon which a reasonable representee would not rely (e.g. this car can really fly)) the burden of proving inducement will shift to the representee who must positively prove that it was reliance upon the representation that caused him to enter a subsequent contract (see Dadourian Group International Inc v Simms [2009] 1 WLR 2967). Contract law 9 Misrepresentation 9.1.3 Categories of misrepresentation Fraudulent – this is the tort of deceit. The requirements in Derry v Peek [1889] 14 App Cas 337 are that the maker of the statement knows or believes that the statement is untrue, or makes it not caring whether it is true or false. The burden of proof remains with the claimant to prove fraud and the burden is a heavy one. Statutory misrepresentation – under the Misrepresentation Act 1967. This Act has created the ‘fiction of fraud’. If a claimant can prove that there was a misrepresentation, bringing a claim under the Act shifts the burden of proof to the representor to prove that they had reasonable grounds to believe and did believe that the statement they made was true. This is a heavy burden of proof, as seen in Howard Marine & Dredging Co Ltd v A Ogden & Sons (Excavations) Ltd [1978] QB 574 and more recently in Foster v Action Aviation Ltd [2013] EWHC 2439 (Comm) where the Court held that where a representor had made a statement on the honest but mistaken belief that it was true (on the basis of the meaning of the term ‘accident’), this was a misrepresentation not made fraudulently but negligently under s.2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967. As will be seen below, the ‘fiction’ is that the remedy provided is the same as if the statement was made fraudulently. Negligent at common law – the maker of the statement and the person relying on it are in a ‘special relationship’ giving rise to a duty of care under the principles of Hedley Byrne v Heller [1964] AC 465 and the maker of the statement acts in breach of this duty. The burden of proof here is on the claimant to prove these elements. Innocent – if the elements of a misrepresentation can be proved but the maker of the statement genuinely believes it is true, and does not act negligently (at common law or under statute, as above) in making it then the action only lies for innocent misrepresentation. Please note that before 1964 an innocent misrepresentation referred to any nonfraudulent misrepresentation because there was at that time no liability to pay damages in respect of anything other than a fraudulent misrepresentation. Liability for negligent misrepresentation now exists at common law under Hedley and under the Misrepresentation Act s.2(1). Consequently the phrase ‘wholly innocent’ misrepresentation is now often used to describe a non-fraudulent and non-negligent misrepresentation. The distinction between these categories is vital in determining the remedies which may be available to the person relying on the statement. This is discussed further in the next section. Activity 9.2 Keith is an international footballer. He enters into a sponsorship agreement with Alpha Sports. A week before signing the sponsorship contract he tells a representative of Alpha that he intends to keep playing for the next five years. Three weeks after the deal is signed Keith calls a press conference and announces his immediate retirement from football. Can Alpha take action against Keith for misrepresentation? Would Alpha’s case be any stronger if evidence appears that Keith had told his manager on the day before he signed the deal with Alpha that he has just decided to retire? Self-assessment questions 1. Define a misrepresentation. 2. What is the presumption of ‘inducement’? How can it be rebutted? 3. Is there a requirement that a misrepresentation be material? If so, what does this mean and how is it applied? 4. What is an ‘innocent’ misrepresentation? page 137 page 138 University of London International Programmes Summary A misrepresentation is an unambiguous false statement of existing fact or law which induces a contract. A statement can be both a misrepresentation and a term of the contract. A misrepresentation may arise from conduct. Statements of opinion are not misrepresentations, provided that the opinion is genuinely held, and not contradicted by facts known to the maker of the statement. Silence does not generally constitute a representation, but representations may be inferred from conduct. Silence may also be treated as a misrepresentation where a statement only reveals part of the truth; where circumstances change, rendering the statement no longer true; or in relation to contracts of the ‘utmost good faith’. A presumption of inducement will arise unless the representor proves that: the representee was aware of the falsity of the statement or, the representee relied upon a different inducement or, the ‘representee’ was not aware of the misrepresentation or the representee would have entered the contract even if aware that the representation was false. Further reading ¢¢ Bigwood, R. ‘Pre-contractual misrepresentation and the limits of the principle in With v O’Flannaghan’ [2005] 64(1) CLJ 94. 9.2 Remedies for misrepresentation The remedies available for misrepresentation will depend on whether it was made innocently, negligently or fraudulently. There are potential remedies available under the common law (both in contract and tort) and under statute (the Misrepresentation Act 1967). The main categories of remedy are first, rescission of the contract and secondly, damages for losses resulting from the misrepresentation. These will be considered in turn. 9.2.1 Rescission The principal common law remedy for a misrepresentation which induced a contract was rescission. This was, and is still, available whether the representation was innocent, negligent or fraudulent. ‘Rescission’ in this context means that the contract is set aside, and the parties put into the position they would have been in had the contract never been made. Any goods or money which have been exchanged must be returned. The equitable remedy of rescission must be sought by the claimant: it does not occur automatically. Until rescission has taken place, the contract will continue to exist. In other words, misrepresentation renders a contract ‘voidable’ rather than ‘void’. Generally speaking the right of rescission will be exercised by giving notice to the other party. There is one authority, however, which holds that rescission can be effected by giving notice to relevant third parties. In Car & Universal Finance Co v Caldwell [1965] 1 QB 525, where the seller of a car wished to rescind the contract when the purchaser’s cheque bounced, it was held that notifying the police and the Automobile Association was sufficient. The seller had done all that he reasonably could to rescind the contract, given that the purchaser had absconded and was untraceable. Limitations on rescission There are some situations where the right to rescind will be lost, sometimes called the ‘bars’ to rescission. uu Where a party to the contract, aware of the other party’s misrepresentation, continues with the contract, and thus ‘affirms’ it: see, for example, Long v Lloyd [1958] 1 WLR 753. Affirmation occurs when the ‘dual knowledge’ test is satisfied (Peyman v Lanjani [1985] Ch 475). It is necessary that at the time of the conduct said to constitute affirmation the representee must be aware of both the circumstance that gives rise to the right to rescind and also to the fact that that right has arisen. Contract law 9 Misrepresentation uu Where there is a significant lapse of time between the making of the contract and the discovery of the misrepresentation. In Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86, for example, the gap was five years. It may well be, however, that a much shorter period would be enough for the right to be lost – unless the misrepresentation is fraudulent. It has recently been suggested that the time at which the representee became aware of the existence of the right to rescind for misrepresentation may affect the operation of this bar to rescission (Salt v Stratstone Specialist Ltd [2015] EWCA Civ 745). uu Where restitution is impossible. Since the idea of rescission is to restore the parties to the position they would have been in had the contract not been made, if property which has been transferred has been consumed or inextricably mixed with other property, rescission will not be permitted. See, for example, Clarke v Dickson [1858] 120 ER 463. The fact that property has been used (rather than consumed), however, will not necessarily prevent rescission, if a payment of money to cover the use can be made. In this sense it is sufficient if substantial restitution may be effected combined with a payment to the representor to cover any diminution in value caused by the representee (Erlanger v New Sombrero Phosphate Co [1878] 3 App Cas 1218 and Salt v Stratstone Specialist Ltd [2015] EWCA Civ 745). uu Where rescission would affect the rights of a third party. The most obvious example is where goods have been sold to the ‘misrepresentor’, who has then sold them on to an innocent third party before the contract has been avoided. The courts will not require the third party to return the goods to the original owner. This is why parties in this type of situation try to argue that the contract is void for mistake (see Chapter 8). Note that the court also has a discretion under s.2(2) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967 to award damages instead of rescission, where it is equitable to do so. This is discussed further in Section 9.2.2. Activity 9.3 In what other circumstances do the courts talk about ‘rescission’ of a contract? How does this differ from ‘rescission for misrepresentation’? Activity 9.4 Why do you think that the remedy of rescission for misrepresentation is subject to so many limitations? Are they justifiable? 9.2.2 Damages The common law was late in recognising a right to damages for non-fraudulent misrepresentations. Originally an innocent misrepresentation provided only an indemnity for necessary expenditures incurred as a part of the contract rescinded by way of monetary compensation: see Whittington v Seale-Hayne [1900] 82 LT 49. Where a misrepresentation was fraudulent, damages were recoverable under the tortious action for deceit. This requires the claimant to prove that the statement was made knowing that it was untrue, without any genuine belief in its truth, or with a reckless disregard for whether it was true or not: see Derry v Peek (1889). Damages for deceit are, of course still available, but where a claimant has a choice of which action to pursue, they will elect to recover damages under Misrepresentation Act s.2(1) because its requirements are easier to prove. The measure of damages for deceit, being tortious, is based on putting the claimant into the position he or she would have been in had the misrepresentation not been made. This is in distinction to putting the claimant in the position he or she would have been in had the statement been true. In general, this precludes the claimant from recovering lost profits on the contract. In some circumstances, however, some damages of this kind may be recovered. In East v Maurer [1991] 1 WLR 461, the fraudulent statement led the plaintiff to buy a business which turned out to be much less profitable than it would have been had the statement been true. The damages recoverable took account of the fact that if the statement had not been made the page 139 page 140 University of London International Programmes plaintiff would probably have bought another business, from which profits would have been made. These potential profits were recoverable, even though the reduced profits on the business actually bought were not. Once it is established that the statement was fraudulent, all losses (calculated on the basis outlined in the previous paragraph) which are directly attributable to the deceit are recoverable. The normal rules of ‘remoteness’ which apply to contract or tort damages do not operate in this situation: Doyle v Olby (Ironmongers) Ltd [1969] 2 QB 158. Activity 9.5 Read the case of Smith New Court Securities Ltd v Scrimgeour Vickers (Asset Management) Ltd [1997] AC 254. What was the difference between the view of the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords in this case? Explain how the measure of damages used by the House of Lords fits in with the principles outlined above. The most important innovation in the Misrepresentation Act 1967 was the introduction of the action for what is generally referred to as ‘negligent misrepresentation’, in s.2(1). In fact, the Act does not use this terminology, but provides that a statement which would form the basis of an action in deceit, if made fraudulently, will also give rise to liability unless the person making it is able to prove that ‘he had reasonable grounds to believe and did believe up to the time that the contract was made that the facts represented were true’. There are two important points to note about this section: the first relates to the burden of proof, noted above; the second to the measure of damages. The burden of proof On the burden of proof, all that the claimant has to do is to prove that a misrepresentation was made and that it induced the contract. The defendant will then be liable for damages under s.2(1) unless he or she can prove that there were reasonable grounds for his or her belief that the statement was true. This may not be easy to satisfy. In Howard Marine and Dredging Co v Ogden and Sons (1978) it was held that reliance on a usually authoritative Register of the details of ships did not amount to ‘reasonable grounds’ for a false statement of a barge’s capacity, when the maker of the statement had access to the correct figure in the shipping documents. The measure of damages As regards the measure of damages, the most important authority is Royscot Trust Ltd v Rogerson [1991] 2 QB 297. Here it was held by the Court of Appeal that damages under s.2(1) should be calculated in the same way as if the statement had been made fraudulently. This means, therefore, that all losses are recoverable, not simply those that were reasonably foreseeable (as would be the case with an action for negligent mis-statement under the Hedley Byrne principle). This conclusion was based on the court’s view of the proper interpretation of s.2(1) and the fact that it appears to require the negligent misrepresentor to be treated in the same way as the fraudulent one. This conclusion is somewhat controversial, and some members of the House of Lords in Smith New Court Securities Ltd v Scrimgeour Vickers (Asset Management) Ltd [1997] indicated doubts about its correctness. It has not as yet been overruled. In Gran Gelato v Richcliff (Group) Ltd [1992] 2 WLR 867 it was suggested that damages under s.2(1) might be reduced to reflect any want of care (contributory negligence) by the representee. This does produce a conundrum as damages in deceit are not reduced to take account of the representee’s contributory negligence (Standard Chartered Bank v Pakistan National Shipping (No 2) (2003)) and yet, according to Royscott the damages available under s.2(1) are the same as those available in the tort of deceit. The law of tort, in Hedley Byrne v Heller (1964), eventually recognised that a negligent misstatement which caused economic loss could be actionable. The action that has developed from this provides another potential remedy for a person who has entered into a contract as a result of a negligent misstatement from the other party. That the action can be used in this way was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Esso Contract law 9 Misrepresentation v Mardon (1976). Generally, however, the claimant in such a situation will be better advised to use the action provided by s.2 of the Misrepresentation Act 1967, since this has advantages in terms of the burden of proof and damages recoverable, as will be indicated below. The one situation where the Hedley Byrne action may be needed is if the statement cannot be categorised as a statement of fact. A negligently given opinion can, for example, be the basis for an action for negligent misstatement under Hedley Byrne, without the need to show that it meets the strict requirements of being a misrepresentation. A further situation where a claimant might choose to pursue an action for damages under Hedley Byrne (or in the tort of deceit) would be where A has suffered loss as a result of reliance upon B’s misrepresentation not through entering a contract with B but rather as a result of entering a contract with C. For example, a financial adviser recommends the purchase of shares. If the advice contains a misrepresentation, damages under s.2(1) are not available as they depend upon the loss being incurred as a consequence of entering a contract with the misrepresentor. In this example the loss results from entering a contract with a third party, the company/person selling the shares. Activity 9.6 In what situations may it be preferable to base an action on ‘fraud’ (that is, using the tort of deceit) rather than on s.2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967? Activity 9.7 Why does McKendrick argue that if the House of Lords does not overrule Royscot v Rogerson then legislation should be used to do so? Section 2(2) of the Misrepresentation Act provides a discretion for a court to award damages in lieu of rescission, where it is adjudged equitable to do so, taking account of the effect of rescission on both parties. The most natural interpretation of the language of s.2(2), however, suggests that damages may only be awarded under s.2(2) ‘in lieu of rescission’ when at the time of award there is a subsisting right to rescission. In other words, such damages are unavailable where there was once a past right to rescind but which right had subsequently been lost because one of the so called ‘bars’ to rescission i.e. affirmation, lapse of time, the impossibility of restitution or the intervention of thirdparty rights (see 9.2.1 above). This interpretation was supported by the Court of Appeal in Salt v Stratstone Specialist Ltd [2015] EWCA Civ 745 thus resolving a longstanding conflict between several first instance decisions on this point. As to the measure of damages under this section, there is similarly no definitive ruling. Section 2(3) states that if damages are awarded under s.2(1) and s.2(2), the latter must be taken into account in assessing the former. This implies that s.2(2) damages will be less than those under s.2(1). In William Sindall plc v Cambridgeshire County Council [1994] 1 WLR 1016 it was suggested that the basic measure under s.2(2) should be the difference in value between what the claimant was misled into believing he or she was receiving under the contract and the value of what was in fact received. This seems sensible as an estimate of the loss of the right to rescind. In this case it was said obiter that the proper measure of damages in lieu of rescission if there had been a misrepresentation as to the existence of a small sewer beneath development land bought for £5 million was the modest cost (£18,000) of re-routing the sewer. Where the misrepresentation is more serious in relation to the contract as a whole damages in lieu of rescission will be refused (Harsten Developments Ltd v Bleaken [2012] EWHC 2704). Self-assessment questions 1. Can a contract be rescinded where a party continues with a contract despite knowing the other party has made a misrepresentation? If so what must be proved? 2. When might a representation be regarded as reckless or negligent? 3. What is the basis of the awarding of damages (in tort) for fraudulent misrepresentation? page 141 page 142 University of London International Programmes Summary The remedies for misrepresentation are rescission of the contract and damages. Rescission is available for all types of misrepresentation, but can be lost by affirmation, lapse of time, impossibility of restitution, or the intervention of third party rights. Damages are available for fraudulent or negligent misrepresentations, under the tort of deceit and s.2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967. The measure of damages is the same in both cases. There is also the possibility of an action for the tort of negligent mis-statement based on Hedley Byrne v Heller. Section 2(2) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967 gives the court a power to award damages in lieu of rescission. Further reading ¢¢ Halson, Chapter 2 ‘Negotiating the contract’, Section ‘The actions for misrepresentation’. 9.3 Exclusion of liability The exclusion or limitation of liability for misrepresentation in contracts between a trader and a consumer will be subject to a test of fairness under the CRA 2015 (s.62 and Schedule 4). For a discussion of the application of this standard see Chapter 6, Introduction and Section 6.2. All other cases are dealt with by s.3 of the Misrepresentation Act 1967, as amended by s.8 of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977. This requires that any clause which attempts to limit liability for misrepresentation must satisfy the requirement of reasonableness set out in s.11 of the UCTA (Chapter 6). In Avrora Fine Arts Investment Ltd v Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd [2012] EWHC 2198 the court considered the criteria set out in Schedule 2 of the UCTA to determine that the clause was reasonable under s.3 of the Misrepresentation Act 1967. Broad attempts to exclude liability have been found to be unreasonable, even if the clauses are drawn from widely used standard conditions: see Walker v Boyle [1982] 1 WLR 495 and Thomas Witter v TBP Industries [1996] 2 All ER 573. In HIH Casualty & General Insurance Ltd v Chase Manhattan Bank [2003] 1 CLC 358, the House of Lords held that the right of a party to exclude damages caused by an innocent or negligent misrepresentation did not extend to a fraudulent misrepresentation. Where there was a fraudulent misrepresentation the party deceived retained the right to rescind the contract and sue for damages. Sometimes the attempt to exclude liability is put into the form of an assertion, for example, that ‘no statements are made other than those contained in the contract itself’. Such ‘entire agreement’ clauses have been considered in a number of cases. Although there is an early authority (on the pre-UCTA version of s.3) which held that such a clause could be effective to restrict liability for statements made by an agent of the party concerned (Overbrooke Estates v Glencombe Properties [1974] 1 WLR 1335), subsequent cases have generally taken the line that an entire agreement clause, or clauses, which attempt to deny that there is any reliance on pre-contractual statements, do fall within the scope of s.3 as far as liability for misrepresentation is concerned. See, for example, Cremdean Properties v Nash [1977] 1 EGLR 58; Inntrepreneur Estates (CPC) Ltd v Worth [1996] 1 ELGR 84; Thomas Witter Ltd v TBP Industries Ltd [1996] 2 All ER 573; Inntrepreneur Pub Co (GL) v East Crown Ltd [2000] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 611. In other cases, however, courts have concluded that clauses which seek to define the applicable duty are outside s.3. See, for example, Watford Electronics Ltd v Sanderson CFL Ltd [2001] EWCA Civ 317 and Overbrooke Estates Ltd v Glencombe Properties [1974] 1 WLR 1335. The conflict between these two positions awaits resolution. See Raiffeisen Zentralbank Osterreich AG v Royal Bank of Scotland (2010) and Avrora Fine Arts Investment Ltd v Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd (2012). Contract law 9 Misrepresentation Summary By virtue of s.3 of the Misrepresentation Act 1967, the exclusion or limitation of liability for misrepresentation is subject to the requirement of reasonableness set out in s.11 of the UCTA. ‘Entire agreement’ clauses are generally regarded as falling within the scope of s.3. Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, Chapter 9, paras 9-123 to 9-134 and Chapter 23, paras 23-002 and 23-064. Sample examination questions 1. Lord Sepulchrave has fallen on hard times. He decides to sell the cherished vintage Bentley which he was given by his brother Barquentine last year. Lord Sepulchrave thinks that it is an example of the very rare 1928 MK I Bentley. In fact it is a very similar 1938 MK II Bentley. Lord Sepulchrave takes the car to Vintage Car Garages. While a garage employee, Flay, is inspecting the car, Lord Sepulchrave says: ‘Don’t worry, I can assure you that it is a perfect MK I Bentley, never had a knock. But I suppose you need to be sure. I’ll leave it with you overnight and you can check it over. You may as well have the documentation as well; that’ll prove it’s a MK I.’ Flay agrees to keep the car overnight as the garage’s Bentley expert will be in the next day. That evening Lord Sepulchrave tells Barquentine of the impending sale. Barquentine is unbothered because he informs his brother ‘it’s had so many knocks it’s hardly in perfect condition.’ The next day the garage’s Bentley expert is off work and so doesn’t inspect the car. Nor does anyone examine the documentation which would have revealed the car’s true model, its age and that the bodywork had been repaired. When Lord Sepulchrave returns to the garage he is offered and accepts £40,000 for the car. The car is in fact worth £10,000. If it were an unblemished MK I it would be worth £60,000. Discuss. 2. Ian, an investment broker, was approached by Vera who asked him whether she should invest in Wander Electronics Ltd. Ian said, ‘You certainly should, Lord Wellybob is a director. It is a very sound company. It is my view that it will go from strength to strength. In fact I own 5,000 shares myself which I can let you have.’ Vera then bought the shares from Ian for £10,000. The company went into liquidation a month later. The shares are now worthless. It now turns out: a. that Lord Wellybob resigned from his directorship a week after Ian’s statement was made b. that Ian’s statement regarding the soundness of the company was based on a report in a financial journal which was intended to refer to Wonder Electronics Ltd but gave the name of Wander Electronics as a result of a printing error. Advise Vera. page 143 page 144 University of London International Programmes Advice on answering the questions 1. The initial identification of the relevant area or areas of law is often the most difficult part of a question. Issues of mistake and misrepresentation often arise together. If no representation is made by either party and one or more of the parties are mistaken only mistake is relevant. However, where, as here, mistaken beliefs result from representations made by the other party, both mistake and misrepresentation are technically relevant. However, the doctrines of mistake that are raised here (i.e. unilateral mistake and common mistake) are very narrow and do not in any event provide for the recovery of damages. So here mistake is of no help to Vintage Car Garages. Vintage Car Garages v Sepulchrave First you should consider the proper classification of the statements made by Sepulchrave. These are that the car is a MK I Bentley and that it has never had any damage. Are these statements terms or mere representations? If they are terms Vintage Car Garages might pursue an action for breach of contract on the basis that they are express terms or that there is a breach of the term implied by s.13 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 that the good sold must conform to any description given. If an action for breach of contract was available it would result in an award of expectation measure damages (i.e. to put the claimant in the position he would have been in if the contract had been performed). This would be an award of £50,000 (£60,000 (the value of the car if it was as described) less £10,000 (its actual value)). In deciding if a statement is a term the courts will consider: a. The parties’ relative skill and knowledge. Where the representor has greater skill and knowledge the statement is more likely to be a term (Dick Bentley v Harold Smith Motors); where the representee has greater skill and knowledge the statement is more likely to be a mere representation (Oscar Chess v Williams). Here the garage, with greater skill and knowledge, is the representee. b. Where a statement is accompanied by a recommendation that it be verified the statement is more likely to be a mere representation (Ecay v Godfroy). Sepulchrave says ‘I suppose you need to be sure’ which is perhaps a weak suggestion to verify. c. Where there is a time lag between the making of the statement and the eventual conclusion of the contract the statement is more likely to be a mere representation (Routledge v McKay). Here there is a day between these events. d. The more important the matter stated the more likely it is to be a term (Bannerman v White). Here the exact model and history are key to its value. Factors 1–3 above suggest the statements by Sepulchrave are mere representations; factor 4 suggests that they are terms. It is therefore most likely that they are representations only so that the only remedies available to the garage are those for misrepresentation. Consider first the general preconditions for liability for misrepresentation (i.e. that there must be an untrue statement of fact that induces the contract (Bisset, Edgington, etc). Here, Sepulchrave makes two untrue statements of fact. It will then be presumed that the contract of sale was induced by reliance upon these misrepresentations. The garage has two options. It might want to rescind the contract (i.e. return the car and receive back the price it paid). Or it might be happy to keep the car and merely receive damages because it paid too much for the car. Rescission is the literal restoration of the parties to their pre-contract position by the mutual re-exchange of goods and money. Mention by name the limits or bars to rescission and note that none arise on the facts of the case. The availability Contract law 9 Misrepresentation of rescission is not lost by the opportunity offered, but not taken, to inspect the property according to Redgrave v Hurd. If the garage seeks damages these may be available under the Misrepresentation Act 1967 s.2(1), in the tort of deceit or in the tort of negligent misstatement. A good answer will display an awareness of the different preconditions for recovery in these actions and advise that s.2(1) is the least demanding to prove. Section 2(1) is subject to a reverse burden of proof (Howard Marine Dredging v Ogden). To escape liability Sepulchrave would need to prove that he had reasonable grounds to believe in the truth of the statement when it was made and that these grounds continued until the contract was made. Even if he can prove the former he could not prove the latter after his conversation with Barquentine. Damages would be the same as those that are available in the tort of deceit (Royscott v Rogerson). These damages may be reduced if the garage’s failure to inspect the car could be considered to be contributory negligence according to Gran Gelato v Richcliff. Consider comparative merits and requirements of tort of deceit, Hedley Byrne and s.2(1). Deceit is only available if Sepulchrave is fraudulent. 2. In order for Vera to have a remedy against Ian for misrepresentation, she will need to show that he has made a false statement of fact which has induced her to contract with him. The statements which Ian makes are: (a) about Lord Wellybob’s directorship; (b) that the company is ‘very sound’; and (c) that it will go from ‘strength to strength’. Lord Wellybob’s directorship. This statement is true when Ian makes it. Is it still true when Vera enters into the contract? This is not clear from the facts, but if she makes the contract after Lord Wellybob has resigned it may be that Ian should have told her about this (see With v O’Flanagan). If she makes the contract before Lord Wellybob resigns, then Ian can only be liable for misrepresentation if at the time he made the statement he knew that Lord Wellybob was planning to resign (see Dimmock v Hallett and Spice Girls v Aprilia). The final issue will be whether the fact that Lord Wellybob was a director was one of the reasons why Vera entered into the contract. This is for her to prove. Company is very sound. Is this an expression of opinion (Bisset v Wilkinson), or a statement of fact? If the former, then Ian’s statement will not be a misrepresentation, unless he is aware of facts that make this opinion untenable (Smith v Land House Corporation). If it is a statement of fact, and is untrue, then did Ian have reasonable grounds to believe that it is true (as required by s.2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967)? He relied on the magazine article – will this be enough to constitute ‘reasonable grounds’? Should an investment broker have more solid bases for making recommendations of this kind? (See Howard Marine v Ogden). Company will go from strength to strength. This is clearly stated as an ‘opinion’. On that basis it will only give a remedy in misrepresentation if Ian did not genuinely hold the opinion (Edgington v Fitzmaurice). Another possibility might be to sue for negligent misstatement under Hedley Byrne v Heller, if Vera can prove that the opinion was negligently given. In any of the above cases, if Vera can establish the misrepresentation, she may wish to rescind the contract. Do any of the bars to rescission apply? The possible bars here are lapse of time, and the impossibility of restitution. You should discuss both of these in considering whether Vera can return the shares and recover her £10,000. In relation to damages, Vera’s argument will presumably be that in the absence of the misrepresentation(s) she would not have bought the shares and that she can therefore recover the full loss she has suffered from the fall in the shares’ value (i.e. £10,000 minus the current value of the shares). Are there any other losses for which she could recover? page 145 page 146 University of London International Programmes Quick quiz Question 1 Which of the following statements is true? Choose one answer. a. A misstatement will only amount to a misrepresentation if it is a statement of fact rather than of opinion and of intention. b. A misstatement will only amount to a misrepresentation if it involves someone failing to disclose all relevant information. c. A misstatement will only amount to a misrepresentation if it is fraudulent or innocent. d. A misstatement will only amount to a misrepresentation if it is the sole reason for the representee entering the contract. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Which of the following statements best explains statutory liability in damages under s.2(1) Misrepresentation Act 1967? a. The misrepresentee has to show that the misrepresentor knew that the statement made was false or had no belief into its truth or made it recklessly where they were indifferent to the truth of the statement. b. The misrepresentee has to show that they were owed a duty of care by the misrepresentor due to a special relationship where it is reasonably foreseeable by the misrepresentor that the misrepresentee would reasonably rely on the statement. c. The misrepresentee will have to secure damages because they will be denied rescission as the courts will not permit them to try and escape a bad bargain. d. The misrepresentee has to show they entered into the contract after the misrepresentation was made. Then the alleged misrepresentor, to evade liability, has to prove that he had reasonable grounds to believe in the truth of the statement made up to the time that the contract was made. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Are the following statements about liability in damages under s.2(2) Misrepresentation Act 1967 true or false? a. Damages are available under this section in addition to a claim for rescission. b. Damages are available under this section whether the statement was made fraudulently, negligently or innocently. c. Damages are available under the section as of right. d. The misrepresentee has to show they entered into the contract after the misrepresentation was made. Then the alleged misrepresentor, to evade liability, has to prove that he had reasonable grounds to believe in the truth of the statement made up to the time that the contract was made. e. It is unclear from the authorities whether for damages to be awarded instead of rescission the recipient must have a continuing or historic claim to rescission. Question 4 Which of the following statements is true? Choose one answer. a. A lapse of time will bar rescission for fraudulent misrepresentation. Contract law 9 Misrepresentation b. Affirmation will always bar rescission. c. If a third party has acquired a right under a contract for value and in good faith then the misrepresentee will lose the right of rescission. d. If complete restitution is impossible then the misrepresentee will lose their right to rescission. e. Don’t know. Question 5 With regard to Morritt V-C’s judgement in the case of Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV (2002), which of the following statements is true? Choose one answer. a. Spice Girls Ltd had a legal duty to disclose that one of their members had already left the group when the contract was concluded and they did not. b. The cumulative effect of the representations which led up to one of the Spice Girls leaving serve as evidence of misrepresentation. c. Aprilia World Service BV expected the line up of the group to remain the same until the transaction came to an end. d. Spice Girls Ltd were not engaged in an actionable misrepresentation because ‘mere silence, however morally wrong, will not support an action in deceit’. e. Don’t know. Question 6 Assuming that A makes a statement (with knowledge of its falsity) inducing B to contract with her (a contract which caused B to suffer loss), which of the following is B best advised to assert in an action against A? Choose one answer. a. That he, B, only contracted with A on the basis of a common mistake. b. That he, B, contracted with A on the basis of a fraudulent misrepresentation. c. That he, B, contracted with A on the basis of a misrepresentation within s.2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967. d. That he, B, contracted with A on A’s innocent misrepresentation. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is a misrepresentation? 2. When is a statement of opinion, or the failure to disclose information, sometimes treated as a misrepresentation? 3. What are the potential remedies for misrepresentation? 4. What are the limitations on the right to rescind for misrepresentation? 5. What are the different measures of damages for misrepresentation? 6. What are the rules which limit the possibility of excluding liability for a misrepresentation? page 147 page 148 Notes University of London International Programmes Part IV Vitiating elements in the formation of a contract 10 Duress and undue influence Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150 10.1 Duress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151 10.2 Undue influence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160 page 150 University of London International Programmes Introduction There is general reluctance to introduce elements of good faith into contract law. Courts are reluctant to set aside a contract between parties of unequal bargaining power solely on the basis of the inequality. At the same time, however, courts will not allow the strong to push the weak to extract agreement and, in certain circumstances, courts will set aside apparent contracts. This is reflective of the idea that there is agreement, genuine agreement. Law and equity developed different responses to the use of illegitimate pressure. Courts of equity would set aside a contract where one party had unduly influenced the other to enter into a transaction. Courts of common law were slower to develop a response to the use of illegitimate pressure but do now recognise, under the doctrine of duress, to render a contract voidable where one party has employed illegitimate pressure during the contractual process. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the effect upon an otherwise valid contract of duress and undue influence to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The development of duress and its expansion to cover economic duress. uu The requirements of economic duress including whether otherwise lawful acts may constitute economic duress. uu The effects upon a contract’s enforceability of a finding of duress. uu The definition and different categories of undue influence. uu The effects, if established, of undue influence. Contract law 10 Duress and undue influence 10.1 Duress Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 17 ‘Duress, undue influence and inequality of bargaining power’ – Section 17.1 ‘Introduction’ and Section 17.2 ‘Common law duress’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 15 ‘Duress, undue influence, and unconscionability’ – Section 1 ‘Duress’. The common law was slow to develop a doctrine of duress. Initially, only duress to the person – a threat to the personal security of an individual – was recognised as duress. Gradually, the law expanded to encompass duress to goods and, more recently, economic duress. We shall examine these in turn. We will begin with the effect of duress upon a contract. 10.1.1 The effect of duress Does duress render a contract void or voidable? This is important because of the potential effect upon a third party. See Chapter 8, Section 8.3.2 ‘Mistakes as to identity’, where this is discussed in relation to mistake.) The better view is that duress renders the contract voidable, rather than void. The apparent consent of the victimised party is treated as revocable. They have the ability to affirm or not to affirm the contract. If they choose not to affirm the contract, it is void. That duress rendered the contract voidable was the position taken in the cases of Universe Tankships of Monrovia v International Transport Workers Federation (The Universe Sentinel) [1983] 1 AC 366 and Pao On v Lau Yiu Long [1980] AC 614. The effect of finding that duress renders a contract voidable creates several important consequences. Two of these are: uu the party subject to the duress must act promptly to set aside the contract – see North Ocean Shipping v Hyundai Construction [1979] QB 705, and uu a third party can acquire good title to goods even though his vendor has acquired those goods pursuant to a contract which was brought about by duress. In Halpern v Halpern [2007] EWCA Civ 909 the Court of Appeal made two observations about duress. The first was that rescission for duress should be no different in principle than rescission for other vitiating factors (such as misrepresentation). The second was that the practical effect of rescission would always depend upon the circumstances of a particular case. If, in the present case, the defendants established that their consent had been procured by duress, it would be ‘surprising if the law could not provide a suitable remedy’. 10.1.2 Forms of duress Duress to the person Duress to the person was the first form of duress recognised by the common law. Duress to the person occurs when one party to a contract forces another to contract with him through threats of violence. The law will find an apparent contract voidable where duress is a reason for the contract. The duress does not have to be the reason for the contract. Where a party enters into a contract for several reasons, of which the duress is only one reason, the contract is still voidable: see Barton v Armstrong [1976] AC 104. Duress to goods Duress to goods may occur where one person takes or destroys, or threatens to destroy or take the goods of another unless a contract is entered into. Duress to goods was recognised in the case of Occidental Worldwide Investment Corp v Skibs A/S Avanti (The Siboen and The Sibotre) [1976] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 293. page 151 page 152 University of London International Programmes Economic duress From the reading of Stilk v Myrick [1809] 170 ER in Chapter 3 it will be remembered that one possible reason (from the Espinasse Report) for not upholding the promise was on policy grounds. However, it is Campbell’s report of this case, based on consideration, that has found acceptance. It has only been in recent years that English courts have accepted that economic duress can be a vitiating factor – that the presence of economic duress will result in a voidable contract. Economic duress as such was recognised in The Siboen and The Sibotre (1976), North Ocean Shipping Co v Hyundai Construction Co (The Atlantic Baron) [1979] QB 705 and Pao On v Lau Yiu Long. The doctrine of economic duress was developed in a small number of cases dealing with the modification, as opposed to the formation, of contracts. For this reason you should cross reference the discussion that follows with that in Chapter 3 on Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) [1991] 1 QB 1 and also the doctrine of promissory estoppel. Both are also concerned with the modification of existing contracts. Economic duress occurs when one party uses its superior economic power to force the weaker party into an agreement. The main difficulty in this area is to draw a line between unacceptable commercial pressures (which amount to economic duress) and acceptable commercial pressures (which do not amount to economic duress): ‘illegitimate pressure must be distinguished from the rough and tumble of the pressures of normal commercial bargaining’ (Dyson J in DSDN Subsea Ltd v Petroleum Geo-Services ASA [2000] BLR 530). In Progress Bulk Carriers Ltd v Tube City IMS LLC (The Cenk Kaptanoglu) [2012] EWHC 273 the court held that what constituted economic duress was to be considered on a fact-specific basis and that there was no requirement that an unlawful act had been committed although it would be unusual to have economic duress in a commercial context without an unlawful act having been committed. Acceptable commercial pressures not amounting to duress were found to exist in the case of Alec Lobb Ltd v Total Oil [1983] 1 All ER 944. In this case, the defendant had extracted hard terms in a contract with the claimant. The defendant had done this because it was reluctant to contract with the claimant. In addition, the commercial pressures upon the claimant had originated with parties other than the defendant. Activity 10.1 Read North Ocean Shipping Co Ltd v Hyundai Construction Co Ltd (The Atlantic Baron) (1979). Summarise in about 250 words the facts and legal issues raised. Duress exists when there is an illegitimate threat to perform an unlawful act unless the other party enters into a contract or varies an existing contract. Consent must be vitiated. It has been said that the victim’s will must be ‘overborne’ such that he does not really consent to the contract: see Lord Scarman’s comments in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long (1980). In more recent decisions, courts have moved away from requiring an overborne will. The reason for this change of position appears to be the recognition that a person who acts under duress does make a choice. Their act is not, in other words, automatic. The choice, however, is one which the law disapproves of and which it thinks they should not have been compelled to make. Lord Hoffmann in R v Attorney General for England and Wales (2003) stated that the ‘wrong of duress’ had two elements: first, ‘pressure amounting to compulsion of the will of the victim’ and ‘the second was the illegitimacy of the pressure’. The difference between acceptable and unacceptable commercial pressures is explained in the speech of Lord Scarman in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long (1980). Lord Scarman stated that commercial pressure was not enough to constitute duress: ‘There must be present some factor “which could in law be regarded as a coercion of his will so as to vitiate his consent”’. Lord Scarman then continued and set out the following indicia as being useful in determining whether or not there was a coercion of the will such as to vitiate consent. Contract law 10 Duress and undue influence 1. Did the person who was allegedly coerced protest at the time? 2. Did this person have an alternative course of action open to him – such as an adequate legal remedy? 3. Was the person independently advised? 4. Did the person take steps to avoid the contract once they had entered it? The decision of the Court of Appeal in CTN Cash and Carry v Gallaher (1994) is of interest because the Court of Appeal was not willing to extend ‘lawful act duress’ to a threat (in this case to withdraw credit facilities) made in a commercial context in pursuit of a bona fide (but mistaken) claim. The Court, however, refused to state that the threat of a lawful act could ‘never’ constitute duress. In Borrelli v Ting (2010), Lord Saville found that the defendant had used illegitimate means to have the claimant enter into a settlement agreement and the illegitimate means consisted of both unlawful and lawful elements. Summary Threats to the person, goods or the illegitimate use of pressure to force a party to contract may result in a contract which is voidable for duress. Economic duress often arises in the context of the modification of contracts. Economic duress has two elements: an illegitimate threat and resulting compulsion of the victim. An otherwise lawful threat might exceptionally amount to an illegitimate threat. Compulsion is established by considering a list of factors including: the presence or absence of protest, any alternative courses of action available to the victim and whether the victim had independent advice. The victim must act promptly to set aside the contract when the duress has been removed or the contract will be considered affirmed and so valid. While courts have recognised a doctrine of economic duress in recent years, it is applied cautiously by the courts. The main difficulty which emerges in these areas is in separating acceptable commercial pressures from unacceptable commercial pressures. Activity 10.2 Would there have been an illegitimate threat for the purposes of the doctrine of economic duress if in The Atlantic Baron the shipyard, instead of threatening not to supply the ship it was building, said that if the extra was not paid the shipyard would terminate ongoing, but not yet concluded, negotiations with the purchaser for the building of a ‘sister ship’? Activity 10.3 Outline the criteria the Privy Council stated in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long (1980) were necessary for duress to exist. Activity 10.4 State the steps necessary for a contract to be avoided (not affirmed) following the decision in North Ocean Shipping v Hyundai Construction (1979). Activity 10.5 Would the Court in Atlas Express v Kafco (1989) have reached the same decision if Kafco were aware that Atlas Express had mistakenly underbid the job? Activity 10.6 Is it helpful to define unlawful pressure by reference to ‘coercion of the will’? Does normal economic pressure not ‘coerce the will’? Further reading ¢¢ Atiyah, P.S. ‘Economic duress and the “overborne will”’ (1982) 98 LQR 197. ¢¢ Halson, R. ‘Opportunism, economic duress and contractual modifications’ (1991) 107 LQR 649. page 153 page 154 University of London International Programmes 10.2 Undue influence Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 17 ‘Duress, undue influence and inequality of bargaining power’ – Section 17.3 ‘Undue influence’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 15 ‘Duress, undue influence, and unconscionability’ – Section 2 ‘Undue influence’. ¢¢ Phang, A. and H. Tjio, ‘The uncertain boundaries of undue influence’, in your study pack. Equity developed a different response to contracts formed where one party was subject to illegitimate pressure during the contractual process. Equity did not focus on the use of force or threats during the making of the agreement but upon the relationship between the parties to the contract. Equity acts upon the conscience and the equitable doctrine of undue influence operates where the people are in a relationship such that one party relies upon the other. Examples of such relationships would be the man inexperienced in financial affairs who relies upon the advice of his bank manager or the aged father who depends upon his daughter to manage his finances. While the common law doctrine of duress is concerned with the procedure by which a contract was agreed, the equitable doctrine of undue influence is focussed upon the relationship between the parties. Lord Nicholls, in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001), describes undue influence as ‘one of the grounds of relief developed by the courts of equity as a court of conscience. The objective is to ensure that the influence of one person over another is not abused.’ In recent years, the House of Lords has twice produced definitive judgments on the doctrine of undue influence. These are Barclays Bank v O’Brien (1993) and Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001). In the past, courts divided undue influence into two categories – actual undue influence and presumed undue influence, based on the decision in Allcard v Skinner (1887). For a period of time, following the decision in BCCI v Aboody (1989), courts divided the cases of presumed undue influence into two sub-categories, class 2A and class 2B. Although the House of Lords adopted this division in Barclays Bank v O’Brien (1993), the House of Lords in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001) re-explained what was meant by this division and disapproved of the labels attached to this category. In one instance, undue influence was presumed as a matter of law by reason of the type of relationship between the parties. In the other instance, undue influence would not be presumed by law, but it was open to a party to establish an evidentiary presumption of undue influence. 10.2.1 Actual undue influence In such cases, the claimant must prove that the wrongdoer actually exerted an undue influence upon the complainant to enter into the transaction in question. In these instances the criteria are: uu that the party to the transaction (or a person who induced a transaction for his benefit) had the capacity to influence the other party uu that he did influence the other party uu that the exercise of this influence was undue uu that it was because of this influence that the transaction was brought about. In a situation of actual undue influence, it is not necessary to show that the transaction was manifestly disadvantageous to the party subject to the undue influence. See: Contract law 10 Duress and undue influence uu Lloyds Bank v Bundy (1975): bank and elderly customer uu CIBC Mortgages v Pitt (1993): husband and wife. This case is also useful for its discussion of manifest disadvantage. Note that there need not be any actual threats made by one party to another. In this regard, actual undue influence is a much broader concept than common law duress. 10.2.2 Presumed undue influence Here the claimant need not prove that there was actual undue influence. These situations, according to Lord Nicholls in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001), may arise in one of two ways. In the first case, the law makes a genuine presumption in relation to certain, defined types of relationships. In the second case, there is a shift in the evidential burden of proof from the complainant to the other party, to show that the transaction was made without improper influence. For this situation to arise two elements are required: firstly that the complainant reposed trust and confidence in the other party, or the other party acquired ascendancy over the complainant; secondly that the transaction is not readily explicable other than as resulting from undue influence. Genuine presumptions The cases where the law makes a genuine presumption of undue influence consist of a small group of prescribed relationships where the law automatically considers the parties to be in a relationship of trust and confidence. Examples of these relationships are: doctor and patient; solicitor and client; trustee and beneficiary; religious adviser and disciple. The law strictly protects the weaker of the parties in such a relationship by establishing a presumption of undue influence. The complainant need not prove he actually reposed trust and confidence in the other party. All the complainant needs to do is to establish the existence of the relationship. In cases where the gift is a small one (such as a birthday or Christmas gift), the presumption will not apply. Where, however, the transaction is more substantial, some explanation will be needed on the part of the donee. In the words of Lord Nicholls ‘the greater the disadvantage to the vulnerable person, the more cogent must be the explanation before the presumption will be regarded as rebutted.’ [para.24] Evidential presumptions In some instances the relationship may not fall within those where undue influence is presumed by law. However, the complainant may prove the de facto existence of: a relationship under which the complainant generally reposed trust and confidence in the wrongdoer, the existence of such relationship raises the presumption of undue influence (per Lord Browne-Wilkinson, Barclays Bank v O’Brien [1994] 1 AC 180, 189). This situation creates an evidential presumption – the complainant establishes the relationship and an inexplicable transaction and the burden of proof then shifts to the other party to disprove the presumption. That the transaction is inexplicable goes to another element which is necessary in cases of presumed undue influence – that the transaction is disadvantageous to the ‘weaker’ party. The presence of disadvantage strengthens the presumption that the only reason for the transaction was the undue influence of the putative wrongdoer. The burden of proof then shifts to the putative wrongdoer to disprove that they did not exercise undue influence, which is done by establishing that the complainant acted independently and understood his or her actions. This is most commonly achieved by showing that the complainant received independent advice before acting. See Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001). page 155 page 156 University of London International Programmes 10.2.3 Undue influence and third parties Thus far we have considered the situation where the undue influence arises between the two parties to the contract. The intervention of a third party gives rise to difficulties. In practice, most litigation occurs where the relationship of undue influence arises between A and B, whereby B enters into a contract with C for the benefit of A. The most common instance of this scenario is when the relationship of undue influence exists between spouses and one spouse induces the other to enter into a transaction with a bank. This often involves the use of the matrimonial home as security for business debts. The issue here is whether or not the transaction with the bank will be set aside because of the relationship with another party. The transaction will be set aside if the bank has actual or constructive notice of the possibility of undue influence. The most common way in which the bank can rebut the possibility of notice is to inform the spouse as to the nature of the transaction and advise them to seek legal advice – see Barclays Bank v O’Brien (1993). The advice offered to banks by the above case has, to a certain extent, been modified by the House of Lords in their more recent decision in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2). In the more recent decision, the House of Lords carefully outlined the steps a financial institution must take to avoid taking a charge with notice of the surety’s claim to set it aside. The House of Lords also provided guidance to solicitors who advise in such transactions (for which see also Padden v Bevan Ashford (2011)). Summary Undue influence is an equitable doctrine. As such, it is concerned with the conscience of the alleged wrongdoer. The focus is upon the relationship between the parties rather than the procedure by which a contract is reached (which is left to duress). Undue influence is a broad doctrine and encompasses two types of undue influence. The first is actual undue influence – where one party has actually exerted an influence over another with regard to a contract. The second is presumed undue influence – an even broader category which includes two sub-groupings. In the first subgrouping, the law irrebuttably presumes that transactions between people who are in certain kinds of relationships are entered into because of undue influence. In the second sub-grouping, an evidentiary presumption is established by the claimant by showing that they reposed trust and confidence in another and that the transaction is disadvantageous to them, or not readily explicable other than on the basis of improper influence. In this second sub-grouping, it is open to the alleged wrongdoer to rebut the presumption by establishing that the claimant entered into the transaction freely with knowledge of the transaction and its consequences. Activity 10.7 What is needed to put the bank on notice as to the rights of the surety? Activity 10.8 Why does the law require proof of disadvantage in relation to presumed undue influence but not actual undue influence? Activity 10.9 Outline the differences and similarities between economic duress and actual undue influence. Further reading ¢¢ Andrews, Chapter 11, Part 3 ‘Undue influence’. Sample examination questions Question 1 ‘Economic pressure is what contractual negotiations are all about: it is futile for the courts to try to intervene.’ Discuss. Contract law 10 Duress and undue influence Question 2 R is a strong-willed and domineering woman. S, the man with whom she lived, left all financial decisions to her. Last year S inherited a holiday apartment in Spain from his aunt A. R insisted that S signed an agreement giving R the exclusive use of the apartment and the right to receive all rent from lettings in exchange for R’s shares in X&Y plc. R and S have now separated. S wants to go and live in the apartment but R will not permit him to use the apartment. The shares in X&Y plc have increased in value. Advise S. Advice on answering the questions Question 1 This question asks you to discuss the doctrine of economic duress and analyse whether or not it should be a ground upon which courts can intervene to invalidate a contract. The common law was slow to recognise ‘duress’ as a ground upon which a contract could be made void. This may be because courts of equity recognised undue influence as a ground upon which a contract could be set aside. Whatever the reason for this, duress, as a ground upon which a contract could be set aside, was recognised in The Siboen and The Sibotre (1976) by Kerr J. In the circumstances of that case, where a charter rate was reduced when the charterer ran into financial difficulties, Kerr J refused to recognise duress. There were great commercial pressures, but not duress, which was defined as ‘a coercion of his will so as to vitiate his consent’. This definition was accepted by Lord Scarman in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long (1980). There are a number of problems with this definition of duress. First, it is by no means clear what is duress and what are great commercial pressures. Secondly, the overborne will theory has been subject to much criticism. Among other problems, it is internally inconsistent. Lord Scarman stated that the commercial pressures ‘must be such that the victim must have entered the contract against his will, must have had no alternative course open to him and must have been confronted with coercive acts by the party exerting the pressure’. In short, ‘it must be shown that the payment made or the contract entered into was not a voluntary act on his part’ [at 636]. Further: in determining whether there was a coercion of will such that there was no true consent, it is material to inquire: [1] whether, at the time he was allegedly coerced into making the contract, he did or did not have an alternative course open to him such as an adequate legal remedy [2] whether he was independently advised [3] whether after entering the contract he took steps to avoid it. [at 635] The reason why this has been criticised as internally inconsistent is that if the victim’s will is truly overborne, how could he realise that there were no alternative courses open or seek independent advice? Professor Atiyah has pointed to other problems with the overborne will theory. A significant one is that if duress operates because the will of the victim has been overborne, surely duress should render a contract void and not voidable? The decision of the Court of Appeal in B&S Contracts & Design Ltd v Victor Green Publications Ltd (1984) indicates that there may be a movement away from the overborne will theory. While this is a logical development, it serves to heighten rather than reduce the difficulties in distinguishing between ordinary commercial pressures and duress. A possible way of differentiating between these two is to say that duress requires an illegitimate threat or pressure. The Olib [1991] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 108 tells us that the threat made must be illegitimate in that it threatens a civil or criminal wrong or the threat itself is a legal wrong. It has also been suggested that a threat may be illegitimate by reason of public policy: The Evia Luck (No 2) [1990] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 319. However, CTN Cash page 157 page 158 University of London International Programmes and Carry v Gallaher (1994) tells us that in certain rare circumstances it may be possible to have a ‘lawful act’ duress claim. See the decision of Lord Saville in Borelli v Ting (2010). While it may be difficult to distinguish between the two, the question also asks you if courts should try to intervene. On the one hand, most contracts are formed under some sort of pressure. Many parties are faced with offers made on a ‘take it or leave it’ basis. Few people are able to negotiate the terms of carriage with the Post Office, or the terms of their mortgage with the Building Society, or the conditions upon which they will receive a telephone service. However, statutes will now protect most consumers in these areas. The real problem will be with small commercial firms – especially when they deal with large enterprises. Here, it is hard to justify allowing the strong to push the weak to the wall. If we accept that contracts are consensual in nature, many of these contracts will not be. If we are concerned about public policy arguments, we have to recognise that the use of illegitimate pressure is objectionable. It is arguable that courts of law have always intervened in these circumstances. Stilk v Myrick (see Chapter 3), although generally regarded as a case in which there was a lack of consideration, may really have been a case where the court was concerned about duress. If courts are going to intervene to prevent the strong from taking advantage of the weak, it must be sound law to do so explicitly, rather than implicitly. Question 2 This question raises issues of undue influence and must be considered in light of the House of Lords’ recent decision in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001). S will want to have the transaction with R declared void. It may be that R has exerted actual undue influence upon S to enter into the contract. S will, thus, want to argue that the undue influence is within that set out in CIBC Mortgages v Pitt (1993). The advantage to S is that once the undue influence is made out, the transaction will be set aside. R cannot in any way ‘rebut’ such a finding. In addition, S will not have to prove that the contract is disadvantageous to him: Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001). This is important since S is financially better off as a result of the contract since the shares in X&Y have appreciated in value. If S cannot prove actual undue influence, he may be able to establish presumed undue influence. His relationship with R does not bring him within those relationships presumed by law to give rise to undue influence. Lord Browne Wilkinson, in Barclays’ Bank v O’Brien (1993), stated that the law accorded spouses ‘tender treatment’ but that it did not presume undue influence. This was repeated in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001). S may be able to establish that he reposed trust and confidence in R (Lloyd’s Bank v Bundy) and that the transaction is not explicable on any other ground. The difficulty S faces here is that financially, the contract has been advantageous to him. He cannot prove that he has been disadvantaged by the contract. In the circumstances, courts will be hesitant to invalidate the contract. Quick quiz Question 1 Which of the following statements provides the most appropriate definition of duress? Choose one answer. a. Where one party (A) explains to the other party (B) that it would be nice of them to enter into the contract because otherwise they (A) will be upset. b. Where one party (A) threatens the other party (B) with physical injury if they do not enter into the contract. c. Where one party (A) feels they have to enter into a contract with the other party (B) otherwise they (A) will not be able to afford to buy a new car. Contract law 10 Duress and undue influence d. Where one party (A) decides to enter into a contract with the other party (B) because the partner of the party (A) has said it is a very good deal. e. Don’t know. Question 2 In Pao On v Lau Yiu Long (1980) what factors did Lord Scarman consider relevant to the determination of whether or not a person acted voluntarily and not subject to economic duress? Choose one answer. a. An extension (of the categories of duress) capable of covering the present case, involving ‘lawful act duress’ in a commercial context in pursuit of a bona fide claim, would be a radical one with far-reaching implications. It would introduce a substantial and undesirable element of uncertainty in the commercial bargaining process. b. It is crucial to establish a strong causative link where pressure comes from one party and the other party feels compelled to act on their instruction. c. It is material to inquire whether the person alleged to have been coerced did or did not protest; whether, at the time he was allegedly coerced into making the contract, he did or did not have an alternative course open to him such as an adequate legal remedy; whether he was independently advised; and whether after entering into the contract he took steps to avoid it. d. The respondent has to demonstrate that they did not force the claimant to enter into the contract and they should do this by providing evidence of the claimant’s careful and deliberate signature upon the contract. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following statements explains how the law of contract defines actual undue influence? Choose one answer. a. This is where the complainant can prove that the other party’s positive exercise of actual pressure induced them to agree to the contract. b. This is where the complainant suggests that because she is married to the man who asked her to sign a set of mortgage papers then this must be actual undue influence. c. This is where one party places trust and confidence in another and so tends to rely on the suggestions of the other party without seeking independent advice. d. This is where the complainant argues that her employer asked her nicely to mortgage her flat as security for the overdraft extension of her employer’s company. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Which of the following statements summarises how the guidelines offered by Lord Nicholls in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2002) would help a bank to avoid a transaction being set aside on the basis of undue influence on a wife following a husband’s attempts to persuade his wife to stand surety for his debts? Choose one answer. a. When the husband realises that his wife is keen to stand surety for his debts then he should ask his own solicitor to reply truthfully and honestly to any questions that his wife may have about the transaction and if the bank believe the wife does understand then they will continue with the transaction. page 159 page 160 University of London International Programmes b. The wife should write to the bank and explain that she wants to stand surety for her husband’s debts and her husband has told her what the ramifications are of her co-operation. Then the bank should send one of their own legal advisers to the couple’s home and speak to them jointly about the potential consequences of default. c. Once the bank become aware that a wife is agreeing to stand surety for her husband’s debts then they should make sure the wife has had the ramifications of her decision explained to her so that she understands what could happen in default. The bank must make sure the solicitor instructed is competent and they will be held responsible for any deficiencies in the advice given. d. Once a bank has been put on inquiry that a wife offers to stand surety for her husband’s debts then they must take reasonable steps to satisfy themselves that the practical implications of the proposed transaction have been explained to the wife in a way which is coherent and comprehensible so that she can enter into the transaction with her eyes open. The bank should rely upon a solicitor to have confirmed that they have advised the wife of the significance of the transaction and should notify the bank that they have done this. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Which of the following statements correctly explains the remedies available in a situation where the bank seeks to enforce its charge over a matrimonial home in circumstances where a wife, subject to undue influence, gave the charge as a guarantee of her husband’s business debts? Choose one answer. a. A contract which is affected by undue influence will be compensated with damages where the courts will instruct the bank to pay the wife a sum of money to refund her for the bill she incurred for the original independent advice. b. A contract which is affected by undue influence is voidable which means that the wife will have to bring an action for rescission to avoid it. c. A contract which is affected by undue influence is void from the outset. d. A contract which is affected by undue influence will be rectified which means the courts will look at the original documentation and ask another solicitor to advise the wife as to the consequences of her decision and then the bank can receive confirmation that the wife now understands the consequences of her action. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is the doctrine of duress? 2. What is the theory behind the doctrine of duress? 3. When will duress vitiate an apparent contract? 4. What are the differences between lawful economic pressure and duress? 5. What is the effect of duress? 6. What is undue influence? 7. Under what circumstances may undue influence vitiate a contract? 8. What approach have courts taken towards undue influence? Part v Who can enforce the terms of a contract? 11 Third parties Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162 11.1 The doctrine of privity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163 11.2 The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164 11.3 Rights conferred on third parties at common law . . . . . . . . . . . . 167 11.4 Liability imposed upon third parties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 176 page 162 University of London International Programmes Introduction Thus far in this guide we have been concerned with three areas of contract law: the formative elements necessary to create a binding contract; the content of a contract; and those elements which vitiate an apparent contract. We turn now to the question of who can enforce the contract. Privity of contract determines who can enforce a contract. This doctrine is easily stated: in general terms only one who is a party to a contract can enforce it. In Chapter 3 we looked, briefly, at Tweddle v Atkinson (1861). In this case, two fathers had entered into a contract, each promising the other to pay their children £100 when they got married. The bride’s father died without paying the money to the couple. The groom sued his estate for the money. Groom’s Father Bride’s Father Groom The court held that the Groom could not sue as he was not party to the contract (also he had not provided consideration for the promise to pay £100). Clearly privity of contract defeated the intentions of the parties to this contract and can lead to substantial injustices. For these reasons many methods have been devised at common law to provide third parties to a contract with a means of circumventing a strict application of the doctrine of privity. The interpretation and employment of these methods and devices has given rise to much complication in English law. It was thus recommended by academics, lawyers and judges that privity of contract should be reformed. The result is the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 which provides parties to a contract with a method of circumventing the doctrine of privity of contract to provide third parties to the contract with a right to enforce contractual terms. It is the breadth of this exception which justifies the title of this chapter as ‘Third parties’. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the rights and obligations which a contract might generate for those who are not a party to that contract to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The doctrine of privity of contract and its two main parts. uu The different justifications, if any, for these two main parts. uu The extent to which the doctrine of privity historically gave rise to problems and the extent to which those problems remain. uu The significance and key provisions of the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999. uu What are the principal provisions of the 1999 Act? uu The major devices by which rights can be conferred on third parties at common law? uu What are the principal strengths and weaknesses of these devices? uu What is the relationship between the rights of third parties at common law and under the 1999 Act? Contract law 11 Third parties page 163 11.1 The doctrine of privity Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 7 ‘Third party rights’ – Section 7.1 ‘Introduction’ to Section 7.5 ‘The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 11 ‘Privity of contract and third party rights’ – Section 1 ‘Origins of the privity doctrine and its relationship with consideration’. The doctrine of privity of contract is primarily concerned with the question of who can enforce a contract. There are two aspects to the doctrine of privity of contract. uu The first is that only parties to a contract are bound by it; A and B cannot, by their contract, compel C (a third party to the contract) to do something or to refrain from doing something (see Figure 11.1). Contract A B n: 0 tio £10 a g li yB Ob o pa t C C Figure 11.1 ‘Only parties to a contract are bound by it’ The obligation on C to pay B £100 in Figure 11.1 is unenforceable because C is not a party to the A/B contract. uu The second is that only the parties to a contract can derive rights and benefits from their contract; A and B cannot, by their contract, confer an enforceable benefit upon C even if A and B clearly intend to confer a benefit upon C (see Figure 11.2). Contract A 0 B : £10 fit ne y C Be o pa Bt C Figure 11.2 ‘Only parties to a contract can derive rights and benefits from it’ The obligation on B to pay C £100 in Figure 11.2 is also unenforceable because C is not a party to the A/B contract. At common law the parties to a contract cannot impose a burden on a third party, nor can they confer a benefit on a third party. See Tweddle v Atkinson (1861). A number of decisions of the House of Lords illustrate the problems created by the doctrine. uu Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre v Selfridge & Co (1915). Dunlop sold tyres to Dew, subject to a retail price maintenance scheme. Dew resold the tyres to Selfridge & Co and sought to impose the same retail price maintenance scheme. Selfridge & Co sold the tyres for a price less than the scheme allowed. Dunlop sued Selfridge & Co on the basis that Dew had contracted with Selfridge & Co as Dunlop’s agent. The House of Lords rejected this argument. In the words of Lord Haldane ‘only a person who is a party to a contract can sue on it’. Lord Haldane also observed that consideration must be provided if a person is to be able to enforce a contract. uu Scruttons Ltd v Midland Silicones Ltd (1962). The House of Lords, Lord Denning dissenting, refused to allow stevedores the benefit of an exemption of a liability clause entered into between the carrier (who hired the stevedores to unload the vessel) and the owner of goods. As a general rule, a stranger to a contract cannot take advantage of its provisions even where the provisions were intended to benefit him. page 164 uu University of London International Programmes Beswick v Beswick (1968). An uncle contracted with his nephew whereby the nephew would receive the uncle’s coal business. In exchange, the nephew agreed to pay a weekly sum to the uncle and, upon the uncle’s death, to the uncle’s widow. After his uncle’s death, the nephew refused to make the payments to his aunt. The House of Lords held that the aunt was not entitled to sue to enforce the obligation to make the payments to her. The aunt was, however, able to succeed in her capacity as the personal representative of her deceased husband’s estate. The first aspect of privity, that the parties cannot by their contract impose liabilities or burdens upon a third party, is intuitively unobjectionable. The circumstances in which justice calls for such a result are very limited. The second aspect, that the parties cannot benefit a third party to the contract, is objectionable. There are many situations in which the parties to the contract clearly intend to confer an enforceable benefit upon a third party. The denial of the benefit to the third party defeated the intention of the contracting parties and often produced manifest injustice and commercial inconvenience. As a result, the common law created a number of devices to overcome the rigorous application of the doctrine of privity. Without these devices, it is doubtful that the doctrine of privity would have survived as long as it did. There were numerous calls for the reform or abolition of the doctrine. After a period of thorough consultation and consideration, the Law Commission recommended a legislative reform of the doctrine of privity (see Law Com No 242, Privity of Contract: Contracts for the Benefit of Third Parties). These recommendations were implemented by the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999. The Act allows the parties to a contract to provide the third party with an enforceable benefit. Activity 11.1 In his speech in Scruttons Ltd v Midland Silicones Ltd (1962) Lord Reid stated that the argument that the carriers had acted as the stevedore’s agent in obtaining for them an exemption clause could be successful if a number of conditions were met. What are these conditions? Were they met in the case before him? Activity 11.2 Consider the arguments in favour of privity of contract and the arguments against privity of contract. Activity 11.3 Why do you think privity of contract has survived in the common law for so long? Summary The doctrine of privity of contract provides that the parties to a contract cannot confer a benefit upon a third party nor can they impose a burden on the third party. Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, G. Some landmarks of twentieth century contract law. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002) [ISBN 9780199255757], Chapter 3 ‘The battle over privity’. 11.2 The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 7 ‘Third party rights’ – Section 7.5 ‘The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999’ to Section 7.15 ‘Collateral contracts’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 11 ‘Privity of contract and third party rights’ – Section 2 ‘Reform of the privity doctrine and the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999’. ¢¢ The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999. Available at www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1999/31/contents ¢¢ MacMillan, C. ‘A birthday present for Lord Denning: The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999’ (2000) 63 Modern Law Review 721. This article is available in HeinOnline through the Online Library. Contract law 11 Third parties The Act implements the recommendations of the Law Commission. It reforms the doctrine of privity; it does not abolish the doctrine. The common law devices which circumvented the effects of privity are, therefore, still effective. The primary reason for reform of the doctrine of privity was to give effect to the intention of the contracting parties. The Act allows contracting parties to provide an enforceable benefit to a third party; the contracting parties cannot impose a burden upon a third party. Two kinds of benefit are available to a third party. The first is a positive benefit and the second is a negative benefit (the protection of an exclusion or limitation of liability clause) (s.1(6)). The Act applies generally to all contracts entered into after 11 May 2000, although certain types of contracts are excluded from its application (s.6). Under the Act, a third party to a contract can enforce a term of the contract in his own right in two circumstances. 1. Where the contract expressly provides that he may (s.1(1)(a)). 2. Where the terms of the contract purport to confer a benefit upon him and nothing else in the contract denies the purported benefit (s.1(1)(b), s.1(2)). The second circumstance is more limited than the first because it is possible, on a true construction of the contract, to rebut the presumption of an enforceable benefit. The right of the third party to enforce a term of the contract is subject to the terms of the contract (s.1(4)). This means that the parties to the contract can impose conditions upon the third party’s ability to exercise his rights under the contract – they could, for example, stipulate that the third party could receive a benefit under the contract only if he applied for it within a certain time period. In Nisshin Shipping Co Ltd v Cleaves & Co Ltd (2003) the Court of Appeal found that a chartering broker was entitled to recover his commission by enforcing a clause under the charterparty between a shipowner and charterer by reason of s.1(1) of the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999. There was no evidence to conclude that the contracting parties intended that the charterer should not be entitled to rely upon the Act. In Prudential Assurance Co Ltd v Ayres (2007) the High Court held that if, on a true construction of the term, it purports to confer a benefit upon a third party, the third party can enforce that term in their own right. The Act does not require that the sole purpose of the term be to confer a benefit upon the third party; in addition it is possible for a term to confer an enforceable benefit upon a third party and some other party. Note the distinction drawn between a contract which purports to confer a benefit upon a party and one which simply improves the position of a third party if the contract is performed – only in the former case will the third party be able to rely upon the Act. For s.1(1)(b) of the Act to apply, it must be one of the purposes of the bargain between the parties to benefit a third party, rather than an incidental effect of contractual performance (see Dolphin Maritime & Aviation Services Ltd v Sveriges Angfartygs Assurans Forening (2009)). The application of s.1(3) of the Act was considered in Avraamides v Colwill (2006). The Court of Appeal held that the s.1(3) requirement of express identification was not satisfied where A had undertaken to ‘pay any liabilities properly incurred by B’. C, to whom the now insolvent B had a liability, could not bring an action against A under the 1999 Act because C was not expressly identified. In contrast, in The Alexandros T, Starlight Shipping Co v Alliannz Marine and Aviation Versicherungs AG [2014] EWHC 3068 (Comm) a settlement agreement between the insurers (called ‘underwriters’) and owners of a ship included a promise by the shipowners not to sue named insurers. When the shipowner sued the insurer’s solicitor and loss adjuster it was held that, properly interpreted, the reference to ‘underwriters’ included their servants and employees and so the solicitors and loss adjusters were sufficiently identified to bring an action under the 1999 Act. The linked nature of a chain of contracts will not preclude the application of the 1999 Act. See: Laemthong International Lines Company Ltd v Artis (The Laemthong Glory) (No 2) (2005), discussed and explained in Great Eastern Shipping Co Ltd v Far East Chartering Ltd (in liquidation) The Jag Ravi (2012). The right of the third party is additional to any right that the promisee might have to enforce any term of the contract (s.4). However, where the promisee has recovered page 165 page 166 University of London International Programmes money from the promisor in respect of the third party’s loss or the promisee’s expense in making good that loss, the court shall reduce any award to the third party to the extent it finds appropriate (s.5). The third party enforces the contract by receiving any remedy that would have been available to him as a party to the contract. The rules relating to that remedy apply accordingly, be it damages, injunctions, specific performance or other relief (s.1(5)). Generally, the parties to a contract cannot rescind the contract or vary it in such a way as to either: 1. deny the right of the third party, or 2. alter the entitlement of the third party once the third party has acquired a right to enforce a term of the contract. In Fortress Value Recovery Fund I LLC v Blue Skye Special Opportunities Fund LP [2013] EWCA Civ 367 the Court of Appeal overturned the lower court’s decision in relation to the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999, s.1 and s.8. In so doing it held that s.1(6) of the 1999 Act established no distinction between a right of action and a contractual defence. The right to take the benefit of an exclusion clause might be subject to a term providing for the arbitration of any disputes. The application of s.8(1) was such that the parties to the contract positively intended that third parties would be bound to the result of arbitration proceedings even if they had not initiated the proceedings in order to secure a benefit apparently conferred upon the third party by the contract. Very clear language was required, however, to bring about the result that for a third party to avail themselves of an exclusion clause in a contract between other parties was, in turn, subject to an arbitration clause in this contract. The third party receives protection from such later changes to the contract in two instances. The first is where the third party has communicated his assent to the term to the promisor. The second is where the promisor is either aware that the third party has relied upon the term or the promisor can reasonably be expected to have foreseen that the third party would rely upon the term and the third party has relied upon the term (s.2(1)). The Act provides that the contracting parties can provide otherwise in their contract. They can contract to allow a rescission or variation of the contract without the third party’s consent or they can obtain the consent in a different manner than that set out in the Act (s.2(3)). Where a third party seeks to enforce his right and brings a claim against the promisor, the promisor can rely on any defence or set-off in the contract and relevant to the term being enforced as if the claim had been brought by the promisee (s.3(2)). In studying the Act, you should keep in mind that it only applies if the contracting parties intend it to provide the third party with the right to enforce a term of the contract. In addition, if the contracting parties intend the Act to apply, they may vary the extent of its application (and thus the extent of the benefit provided to the third party) by a number of means. Firstly, they could provide that the contract could be later varied or rescinded by the contracting parties (s.2(3)). Secondly, the contract could provide that the promisor could avail himself of any and all defences and set-offs available in any action brought by the third party (s.3(3)). Thirdly, the promisor can limit or exclude any liability for negligence (other than death or personal injury) in the performance of his obligation to the third party (s.7(2)). The Act provides an enforceable right to third parties which is given in addition to any right or remedy available at common law (s.7(1)). This means that the various devices developed by the common law to evade the consequences of privity still exist. The Act also allows the common law to develop new devices. Summary The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 represents an enormous change to the common law doctrine of privity because it allows contracting parties to confer an enforceable benefit upon a third party. The intentions of the parties to a contract can Contract law 11 Third parties page 167 prevail, rather than being thwarted by legal doctrine. It is important to remember, however, that the parties must bring themselves within the ambit of the Act and that they can exclude its operation from their contract. In addition, the Act provides the parties with the ability to determine the extent of the benefit conferred upon the third party. Self-assessment questions 1. When is a third party given the right to enforce a term of the contract? 2. What rights are given to a third party? 3. What defences are available to the promisee in an action brought by the third party? 4. To what extent can the parties to the contract vary or rescind the contract? 5. How can the parties to a contract exclude the rights of a third party? Further reading ¢¢ Burrows, A. ‘The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 and its implications for commercial contracts’ (2000) Lloyd’s Maritime and Commercial Law Quarterly 540. 11.3 Rights conferred on third parties at common law Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 7 ‘Third party rights’ – Section 7.14 ‘Rights of the promisee’ to Section 7.24 ‘Conclusion’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 11 ‘Privity of contract and third party rights’ – Section 3 ‘Agency’ to Section 7 ‘Privity and burdens’. As already noted, the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 did not abolish privity. In addition, the Act preserved any rights the third party would have at common law (s.7(1)). This section examines the nature of these rights, most of which derive from various ‘devices’ or methods created in a number of cases for the purpose of circumventing the doctrine of privity of contract. The breadth and utility of these devices varies greatly. 11.3.1 Enforcement by the promisee This is an obvious proposition. It is, essentially, what occurred in Beswick v Beswick. The estate of the promisee was able to enforce the promise. Thus, if A (the promisor) promises B (the promisee) to pay C (the third party) £100, B can sue to enforce this promise. The 1999 Act, s.4, retains the promisee’s right to enforce the contract. While this method eliminates many problems presented by privity it is not without difficulty. A Contract to pa y£ B 10 0 C Figure 11.3 Enforcement by the promisee A (the promisor) contracts with B (the promisee) to pay C (the third party) £100. B can sue A to enforce the promise because of the A/B contract. Two difficulties can arise when the enforcement is to be made by the promisee. 1. The promisee may be unwilling, or unable, to enforce the contract (in these circumstances, there is little C can do to compel B to enforce the contract). 2. The second difficulty is to find an appropriate remedy for B. page 168 University of London International Programmes As we will see in Chapter 16, the general purpose of an award of damages is to put the party where they would have been but for the breach of contract. The problem in these circumstances is that B would never have received the money in the first place. She is thus no worse off when the contract is breached by A than if it were performed by A. Another possible view of this problem is that B has a ‘performance interest’ in the contract and that damages should be awarded to B because this interest has not been realised. Courts are reluctant to recognise such an interest (see Panatown v Alfred McAlpine Construction Ltd (2000)). The problem of an adequate remedy was considered in Beswick v Beswick. Where the promise was made solely for the benefit of the third party, the House of Lords had difficulty in awarding damages. In that case, an order was made for specific performance. This result was agreed, in obiter, by the House of Lords in Woodar v Wimpey Construction (1980). In Radford v DeFroberville (1977), however, the Court held that B’s claim against A for damages was not reduced by the fact that the contract between A and B also conferred a benefit upon C. There are a number of circumstances in which the promisee has been able to receive an award of damages. These are considered below. Multiple bookings In Jackson v Horizon Holidays (1975), Lord Denning recognised that a person who booked a holiday on behalf of himself and family members was able to recover damages on behalf of the family members where the contract was breached. The House of Lords later restricted the ambit of this decision in Woodar v Wimpey Construction (1980). Sellers’ contracts with carriers to take buyers’ goods for delivery In The Albazero (1977), Lord Diplock recognised a limited ability on the part of one party to recover damages on behalf of another. This can occur where, for example, a seller of goods contracts with a carrier to deliver the goods to a buyer. After this first contract has been entered into, the seller enters a second contract of sale with the buyer and sells the goods to the buyer. The buyer has no contract with the carrier. The seller has a contract with the carrier, but because he has transferred the goods to the buyer, he is no worse off if the contract is breached and the goods are in some way damaged. The Albazero recognised that when the seller and carrier contract in contemplation of a second contract with the buyer, the seller can recover substantial damages on behalf of the buyer where the goods are lost or damaged. Contracts where the subject matter will be acquired by a third party The decision in The Albazero was subsequently extended in two cases. First in Linden Gardens Trust v Lenesta Sludge (1993) to cover the situation where A and B contract on the basis that the property which is the subject matter of A’s obligations may at some point be acquired by a third party, C, and on the footing that B should be able to enforce the contract to its full extent for the benefit of C. Second, in Darlington BC v Wilshier Northern (1995), to the situation where it is contemplated that the third party was (as opposed to will become, as in Linden Gardens) the owner of the property. While these extensions initially met with judicial approval, its application has been subsequently limited by the House of Lords’ decision in Panatown v Alfred McAlpine Construction Ltd (2000). Following this case, where the third party has a direct remedy of some sort against the promisor, the exception(s) will not be applied. An order for the promisor to perform In some situations it may be possible for the court to make an order for the specific performance of the contract, as in Beswick v Beswick. In other situations, it may be possible for a court to enforce a promise not to do something. Thus, if the promisor A contracts with promisee B not to sue third party C, B can ask the court to stay the proceedings against C: see Snelling v John G Snelling (1973). This approach is not without difficulty: see Gore v Van Der Lann (1967). In that case, B was said not to have an ‘interest’ unless he had a legal liability to C. Contract law 11 Third parties page 169 Activity 11.4 What is the relationship between the 1999 Act and the common law with regard to the provision of exceptions to privity? Activity 11.5 Is it likely that courts will accept a ‘performance interest’ on the part of a promisee and allow the promisee to recover substantial damages for a breach which deprives the third party of his intended benefit? 11.3.2 Agency Agency is not so much an exception to privity as a general commercial necessity. If A cannot, or does not choose to, negotiate directly with C he may authorise B to do so on his behalf. As a general rule, the resulting contract creates privity between A and C, with B dropping out of the picture. See Shanklin Pier Ltd v Detel Products Ltd (1951). Occasionally legislation uses agency to avoid the difficulties caused by privity. Contract (i) A Contract (ii) A B The agent of C C Figure 11.4 Agency At point (i), A contracts with B as C’s agent. The result is illustrated by point (ii) – A has a contract with C and thus C can enforce the contract. 11.3.3 Exemptions and limitations of liability Where A and B contract for B to perform a service, it may be intended that B will render part of his performance through C, a third party to the contract. For example, if A (the owner of goods) contracts with B (the carrier) to deliver goods from Port 1 to Port 2, C may subcontract the unloading of the goods at Port 2 to a third party (the stevedores). B has two contracts in this example: the first is with A for the carriage of goods and the second is with C for the unloading of the goods. It is common practice for B to seek to limit or exclude his liability for breach of contract through the inclusion of a clause to this effect. B may also seek to extend the benefit of this clause to C. It is at this point that a problem arises, because C is not a party to this first contract. The lack of a contract between A and C is no bar to A suing C in tort should C damage A’s goods. A Contract 1 [A to exclude liability of B and C] Owner B Carrier Contract 2 Carrier A B C Third Party Stevedores C Stevedores Tort C A sues C in Tort Owner Stevedores Figure 11.5 Exemptions and limitations By contract 1, A contracts with B to carry A’s goods and a clause is included which limits or exempts the liability of B and C. By contract 2, B contracts with C to unload A’s goods. page 170 University of London International Programmes Should C damage the goods, A may bring an action in tort against C. C is unable to protect himself using the exemption clause in contract 1 since he is not a party to that contract. Courts have stretched the agency concept in one particular situation to provide the third party with the benefit of the exclusion clause in contract 1. This was established in The Eurymedon, New Zealand Shipping v Satterthwaite (1975) and applied again in Port Jackson Stevedoring v Salmond and Spraggon (1980). In The Eurymedon, the Privy Council established that in the situation outlined above, it may be possible for B to contract with A as C’s agent. Through B, A offered an exemption of liability to C. C, in performing their contract with B and unloading the vessel, accepted this offer and a contract between C and A was formed such that C could rely on the exemption clause. (i) A (ii) C Offer to C of immunity B (C’s agent) Performs Contract 2 (B/C) Accepts A’s offer through performance Result A (iii) Contract 3 whereby A exempts liability of C C Final Result (iv) A Tort C Contract 3 Exemption clause Figure 11.6 The Eurymedon device In Figure 11.6 the following chain of events takes place: uu in (i) A offers immunity to C through B uu in (ii) C unloads the ship and performs contract 2 uu the result is (iii), a contract between A and C whereby C is given some form of immunity from action by A uu the final result is (iv), that should A sue C in tort for any damage, C can defend the action on the grounds of the exemption clause in contract (iii). An excellent summary of the development of the law in this area is provided by Lord Goff in The Mahkutai (1996). Lord Goff observed that in the late 20th century the pendulum of the law swung away from Scruttons Ltd v Midland Silicones Ltd. The effect of the 1999 Act upon this pendulum is, as yet, uncertain. Following the 1999 Act, the third party can, however, still take advantage of an exception clause in a contract for the carriage of goods by sea: s.6(5). It remains to be seen whether it would be possible to use the device in The Eurymedon to confer other benefits (see The Mahkutai (1996)). Activity 11.6 What conditions must be met in order for the exemption clause to protect the third party through The Eurymedon device? Activity 11.7 What was the consideration provided by C to A for the contract of immunity in The Eurymedon? Contract law 11 Third parties Activity 11.8 A contracts with B for B to carry goods between Dover and Calais by sea. Included in this contract is a clause that exempts B and B’s agents, employees and subcontractors from liability for any damage, howsoever caused. B contracts with C for C to unload the ship. The ship carries several cargoes besides A’s goods. In unloading goods belonging to Z, C accidentally destroys A’s goods. What advice do you give to C as to his liability to A for the damage? 11.3.4 Collateral contracts Occasionally a third party may be made liable on the basis that he has made some promise in consideration of the promisee’s entry into the ‘main contract’. See, for example, Andrews v Hopkinson (1957). 11.3.5 Trusts It is possible for the promisee as ‘owner’ of the promise to constitute a trust of the promise (i.e. B holds A’s promise on trust for C). Where this happens, B may recover from A the whole of the loss suffered by C because of A’s non-performance: Lloyd’s v Harper (1880) 16 Ch D 290. Taken to its furthest extent, a trust of a promise negates privity altogether, for the third party must simply assert that B is the trustee of the promise and that the benefit of the promise is the third party’s. Possibly for this reason, this device has not met with favour. There have been few successful decisions since the 1930s. Thus in the case of Re Schebsman [1944] Ch 43 a company promised a retiring employee to pay an annuity to his widow and to his daughter if she (the widow) died within the annuity period. The court held that there was no trust in favour of the widow or daughter. The reason for refusing to find a trust is usually a failure to prove any positive intention to create a trust. This intention to create a trust was originally a fiction in this context: its strict requirement means that there are very few cases where the trust concept will circumvent the doctrine of privity. In Darlington BC v Wiltshier, two members of the Court of Appeal found in obiter that the case could have been resolved on the basis that Morgan Grenfell could, before any assignment to the Council, have sued for damages for the breaches and recovered substantial damages as constructive trustee for the council. This flowed from the particular wording of the covenant. 11.3.6 Legislation For the sake of completeness, you should be aware that in some specific instances, a statute may overcome the problems that would otherwise be posed by privity. Examples of this can be seen in the Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Act 1930 s.56, s.75 Consumer Credit Act 1974 and s.56 Law of Property Act 1925. While you do not need to know the specific details of the operation of these provisions, you should be aware that in particular circumstances the difficulty created by privity may have been overcome by legislation. Summary The harshness caused by a strict application of privity led to the judicial development of a number of devices and approaches to circumvent the application of privity. The application, or the lack of an available application, of these devices and approaches could itself cause injustices to arise. Following the 1999 Act, these devices and approaches continue to exist. Their further development, in situations where the parties have expressly chosen not to avail themselves of the 1999 Act, is questionable. page 171 page 172 University of London International Programmes Activity 11.9 a. Would the widow in Re Schebsman have been better off if there had been a trust? b. In what way, if at all, does the decision in Beswick v Beswick form an exception to privity? c. How would the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 affect the decision in Beswick v Beswick? d. How would the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 affect the decision in New Zealand Shipping v AM Satterthwaite? e. Following the enactment of the 1999 Act, is it likely that courts will continue to devise exceptions to the doctrine of privity? No feedback provided. Further reading ¢¢ Halson, Chapter 9 ‘Third parties’, Section ‘Collateral contracts’ on the Linden Gardens principle. 11.4 Liability imposed upon third parties Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 7 ‘Third party rights’ – Section 7.23 ‘Interference with contractual rights’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 11 ‘Privity of contract and third party rights’ – Section 7 ‘Privity and burdens’. The question here is the extent to which the burden of contracts relating to things other than land can ‘run’ with them in the same way that the burden of restrictive covenants can run with land. The answer is far from clear. See Lord Strathcona Steamship v Dominion Coal (1926), which was not followed in Port Line v Ben Line Steamers (1958). See also Swiss Bank v Lloyds Bank (1979, at first instance). It is the case that in instances where a bailment has occurred that there may be a subbailment on terms. In The Pioneer Container (KH Enterprise v Pioneer Container) (1994) the Privy Council applied principles of bailment to hold that the owner of the cargo was bound by the agreement between the bailee and the sub-bailee, although the owner was not a party to the agreement. The liability upon the owner is imposed as a result of the sub-bailment on terms rather than by contract. Self-assessment questions 1. What are the two aspects of the doctrine of privity? 2. Name three devices used in common law to give enforceable benefits to third parties. 3. What is the main test of whether third parties should be given rights under contract? 4. In relation to the doctrine of privity, what is a ‘performance interest’? 5. Outline the Eurymedon case and when the device created in this decision can be utilised by contracting parties. 6. Can a contract impose a liability on a third party? Summary The number of situations in which liability is imposed upon third parties is limited and is usually dependent upon the knowledge or implied consent of the third party. Contract law 11 Third parties Further reading ¢¢ Halson, Chapter 9 ‘Third parties’, Section ‘Bailment’. Examination advice The material considered in this chapter has frequently come up in examination papers on contract as a question on its own. The questions have taken the form of either: 1. an essay question 2. a problem question. Examples of both are set out below. Because the material in this chapter goes to the very essence of the nature of contract law, it could be combined with issues from many other areas of contract law in an examination question. Sample examination questions Question 1 Last year C entered the employment of D Ltd for a fixed period of six years, his contract providing that, if he should die before the end of the six years, D Ltd would pay his widow £2,000 a year for three years from his death. C died in January this year, but D Ltd has refused to make any payment to his widow (E). Advise E. Question 2 F lives alone in his own house. His house suffers badly from rising damp. Living conditions have become unpleasant. Unfortunately, F does not have sufficient funds to pay for a course of damp proofing. His daughter, G, offers to pay for the damp proofing. F gratefully accepts this offer. G hires Hopeless Builders Ltd to carry out the damp proofing. Hopeless agree to undertake the task for £10,000. G pays Hopeless in advance. Hopeless estimate that it will cost between £7,000 and £10,000 to undertake the damp proofing. They agree to refund any difference between the £10,000 paid and the actual cost. The refund is to be given directly to F. The damp proofing is badly conducted and F’s house is damaged as a result. The actual cost of the damp proofing and related repairs was only £8,000. Hopeless refuse to provide F with any refund. Advise F. Question 3 ‘The doctrine of privity has become largely irrelevant as a result of recent changes.’ Discuss. Advice on answering the questions Question 1 The widow E is a third party beneficiary to the contract between C and D Ltd. As such, privity of contract prevents her from enforcing the contract (Tweddle v Atkinson, Dunlop v Selfridge & Co). There are, however, two possible ways in which she could overcome the problem posed by privity. The first is that she may be able to utilise the device employed in Beswick v Beswick. That is to say, if she is the executrix or administratrix of her husband’s estate she could apply in that capacity for an order for the specific performance of the contract. In this instance, the representative of the promisee’s estate would seek to enforce the contract. The second possible way is if E can bring herself within s.1 of the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999. She would need to establish that she could enforce a term of the contract (that regarding the payment of the annuity to her) because either the contract expressly provided that she could (s.1(1)(a)), or because the term purported to confer a legally enforceable benefit upon her (s.1(1)(b)) and this was not refuted upon a proper construction of the contract (s.1(2)). If this right is given to E, she can receive any remedy which would have been available to her if she had been a party to the contract in question. In this instance, this is likely to be damages, although an order for specific performance might be made instead. page 173 page 174 University of London International Programmes Question 2 There are a number of issues present in this problem. F is a third party beneficiary to the contract between G and Hopeless. F is the intended beneficiary not only of the work to be conducted (the damp proofing) but is also to receive any refund that exists. As discussed above, F will need to bring himself within s.1 of the 1999 Act to sue upon the contract with regard to the deficient work and the damage caused. The likely remedy in this case will be damages. With regard to the payment of the refund, it could be argued that there is not a term of the contract which is intended to confer a benefit upon F. See, for example, White v Jones (1995). Another possible course of action is for G to sue Hopeless and to recover the refund for the benefit of F. The difficulty with this course of action is that it would appear that under the original terms of the contract the money was to go to F – is G, therefore, any worse off when F does not receive the money? See Jackson v Horizon Holidays and Linden Gardens Trust v Lenesta Sludge. Question 3 A good knowledge of the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 is essential in answering this question. You need to consider that the doctrine of privity has not been abolished but merely reformed by the Act. In particular, you would have to consider when the Act applied (s.1(1)) because, in absence of the application of the Act, all the old problems associated with privity of contract would remain. A good answer might also consider the decision of the House of Lords in Panatown v Alfred McAlpine Construction Ltd as an instance of the difficulties which could arise if the Act did not apply. Quick quiz Question 1 In which of the following circumstances would the third party’s claim be successful and not prevented because of privity of contract at common law? Choose one answer. a. A tyre seller sells tyres to a distributor on the basis that they would not be resold below the seller’s list price and if the distributor sold the tyres to a trade buyer the distributor would ensure that the trade buyer would also have a price restriction clause imposed on them. The trade buyers then sell the tyres below the seller’s list price. The seller tries to recover damages in light of the trade buyers selling the tyres below list price. b. A sells his coal business to B and A agrees that upon A’s death B will be able to receive further financial assistance from C, A’s spouse. A dies. B sues C for financial support. c. A vendor agrees to sell land to a contractor for a specified sum and also an additional sum to a third party. A dispute arises between the purchasers and the vendors who brought an action for breach claiming not only the specified sum but also the additional sum owed to the third party. d. A purchaser contracts with a builder for the construction of a large building and office development. Before the building was completed the purchaser assigned his interest to another third party. The purchaser sued the builder, after assignment, for defective work. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Which of the following methods has NOT been successfully used as a ‘device’ to circumvent the rule of privity of contract? Choose one answer. a. Agency. b. Collateral contracts. c. Legislation. Contract law 11 Third parties d. The Trust. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following elements need not be present in order to form a Himalaya clause applying the decision in The Eurymedon? In the statements set out below, assume A is the owner of goods who contracts with B, a carrier, to carry the goods by sea. C is a firm of stevedores who is not party to this contract but who contracts separately with B to unload A’s goods. Choose one answer. a. A must include in the contract a clause which exempts the liability of not only the other party to the contract with B but also servants, agents and subcontractors of B such as C, the stevedores who unload A’s goods. b. The clause exempting the liability of B’s servants, agents and sub-contractors must be contained in a deed in writing. c. B must be authorised to act as C’s agent to receive the offer contained within A’s exemption clause or to receive later ratification by C to so act. d. C must provide consideration to A in order to support the exemption offer made to C through the agency of B. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Which answer best summarises why the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 was enacted? Choose one answer. a. The Contract (Rights of Third Parties) Act was enacted because the Law Commission mandated that Parliament should enact the legislation. b. The Contract (Rights of Third Parties) Act was enacted because European Union law required that English contract law be harmonised with that of other member states of the European Union, all of which recognised a binding third party right in contract. c. The Contract (Rights of Third Parties) Act was enacted because it was thought the best way to facilitate the intention of the contracting parties. d. The Contract (Rights of Third Parties) Act was enacted because it was a suitable birthday gift for Lord Denning. e. Don’t know. Question 5 The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 does not allow which of the following actions? Choose one answer. a. To bind a third party, C, to the obligations created in a contract between A and B. b. A and B, having created by contract a right in favour of C, a third party, can vary their contract to remove the right given to C. c. To allow C to enforce a benefit in a contract between two other parties or to avail herself of a limitation clause in a contract between two other parties. d. To allow a third party, C, to enforce a term of a contract between two other parties where he is not named. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. page 175 page 176 University of London International Programmes Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is the doctrine of privity? 2. What are the two aspects of the doctrine of privity? 3. Is one aspect easier to justify than the other? If so which aspect and why? 4. What are the two major forms of benefit available to a third party? 5. To what difficulties does the doctrine of privity give rise? 6. What is the significance of the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999? 7. What are the principal provisions of the 1999 Act? 8. What are the possible applications of the 1999 Act? 9. What are the major devices by which rights can be conferred on third parties at common law? 10. What are the principal strengths and weaknesses of these devices? 11. What is the relationship between the rights of third parties at common law and under the 1999 Act? 12. In what possible ways can liability be imposed upon third parties to a contract? Part VI Illegality and public policy 12 Illegality Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178 12.1 Statutory illegality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179 12.2 Common law illegality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181 12.3 The effects of illegality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187 page 178 University of London International Programmes Introduction A contract affected by illegality is one that fails for reasons external to the contract and the parties to it. Illegality, as a topic, covers a wide range of different areas. Illegality will affect all of the following contracts. uu A contract to commit a legal wrong (e.g. murder or robbery). uu A contract which promotes immorality. uu A contract which is performed illegally. uu A contract which is not formed in accordance with the procedure prescribed by a statute. In the recent case of Patel v Mirza [2016] 3 WLR 399 a Supreme Court comprised of nine justices took the opportunity to review this area of law which they noted had ‘caused a good deal of uncertainty, complexity and sometimes inconsistency’. In a number of recent cases before the Supreme Court, two distinct approaches had emerged between on the one hand a policy-driven approach to each individual case and on the other ‘a clear cut test’ of enforceability the application of which, although sometimes arbitrary, is commendably certain. The majority of the justices (Lords Toulson, Kerr, Wilson and Hodge as well as Lady Hale) identified two broad policy reasons for the retention of a defence of illegality that: a person should not be allowed to profit from his own wrongdoing and that the law should be coherent and not self-defeating. More particularly, the underlying rationale was the maintenance of the integrity of the legal system and perhaps also some aspects of public morality. The broad effect was to remove conflicting rules, maxims and presumptions and replace them with a single policy-based enquiry as to whether the enforcement of a claim would injure the integrity of the legal system. This single judgment was however multifactorial and Lord Toulson who delivered the leading judgment endorsed a helpful list of factors identified in academic writing including: uu How seriously illegal or contrary to public policy the conduct was. uu Whether the party seeking enforcement knew of, or intended, the conduct. uu How central to the contract or its performance the conduct was. uu How serious a sanction the denial of performance was for the party seeking enforcement. uu Whether denying enforcement will further the purpose of the rule which the conduct has infringed. uu Whether denying enforcement will act as a deterrent to conduct that is illegal or contrary to public policy. uu Whether denying enforcement will ensure that the party seeking enforcement does not profit from the conduct. uu Whether denying enforcement will avoid inconsistency in the law thereby maintaining the integrity of the legal system. But also adding: uu The seriousness of the conduct, its centrality to the contract, whether it was intentional and whether there was a marked disparity in the parties’ respective culpability. The facts of Patel v Mirza (2016) were simple. Patel paid £620,000 to Mirza to gamble on the movement of shares in a bank on the basis of inside information. When that intelligence was not forthcoming, Patel tried to reclaim his money from Mirza. All nine justices agreed that Patel was entitled to the return of his money, the majority on the basis that the enforcement of Patel’s claim would not undermine the integrity of the legal system and the minority on the basis of a narrower rule-based approach. Contract law 12 Illegality This decision of the Supreme Court has not yet been incorporated in many textbooks. Further, different writers use different classifications. For this reason, it is recommended that if you find yourself struggling with one author’s account of the subject you first check whether the author has taken account of the Supreme Court’s decision in Patel v Mirza (2016) and then, making allowance for this, persevere as much as you can before reading another account. The reason is that, if a particular aspect of one author’s analysis of the topic confuses you, it is not always easy to simply read a different account of that aspect written by another author who might have classified the whole topic very differently. In this respect the topic of illegality is similar to that of mistake which was discussed in Chapter 8. The exact status of much of the old case law is now in doubt in light of the approach of the majority in Patel v Mirza (2016). It is likely that the cases discussed below will continue to provide guidance as to the application of the individual factors identified as relevant by the majority of justices. The exception to this are the House of Lord’s decision in Tinsley v Milligan (1994) and the Court of Appeal case of Bowmakers Ltd v Barnet Instruments (1945) which were respectively not followed and disapproved and are discussed further below at 12.3.1. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the concept of restraint of trade and its effect upon contracts entered, to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The different contractual contexts in which restraint of trade can arise. uu The circumstances when an employment contract will be found to be in restraint of trade. uu The circumstances when a contract to sell a business will be found to be in restraint of trade. uu The differences of approach by courts to restraint of trade clauses in an employment contract and in the sale of a business. uu When might a court consider a clause to be an offensive restraint of trade in other circumstances? uu What is an unacceptable restraint of trade? 12.1 Statutory illegality Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 15 ‘Illegality’ – Section 15.1 ‘Introduction’ to Section 15.5 ‘Gaming and wagering contracts’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 16 ‘Illegality’ – Section 1 ‘Illegal contracts’. 12.1.1 Types of illegality It may be helpful to consider certain distinctions that exist within the illegality cases. The first distinction exists between common law illegality (such as a contract to commit a murder or a robbery) and statutory illegality (such as a statute which requires the vendor of a certain good to possess a licence to sell the good). A second distinction exists between contracts that are illegal as formed (such as the contract to commit murder or robbery) and contracts which are legal as formed but illegal as performed (a contract to deliver pizzas then performed by a motorcyclist who exceeded the speed limit). In general terms, courts will not enforce a contract which involves an illegality, nor will they allow the recovery of a benefit conferred by an illegal contract. There are a number of, often overlapping, reasons for this (see generally Parkingeye Ltd v Somerfield Stores Ltd (2012) where Lord Toulson first and, at that time, unsuccessfully proposed a policy-based approach to each case), such as: page 179 page 180 University of London International Programmes uu to deter parties from such conduct uu to prevent parties from benefiting from their own wrong uu to punish wrongdoers uu to preserve the dignity of the court and integrity of the legal system uu for reasons of public policy (where it would be offensive to society and the law for courts to enforce an illegal contract). The refusal to enforce a contract because of illegality can be an unnecessarily harsh and unreasonable response. Should, for example, the recipient of the pizzas delivered by the speeding motorcyclist be able to refuse to pay for the pizzas on the ground that the contract was illegally performed? Because of the harshness that can result, courts will sometimes allow a party to enforce a contract or to recover a benefit conferred. The result is to create a certain inconsistency in cases involving illegality. 12.1.2 Contracts that are illegal as formed Where a contract is illegal as formed it is void ab initio, from the beginning. The illegality is present from the outset of the contract. A statute, for example, may expressly prohibit a certain type of contract. See, for example, Re Mahmoud & Ispahani (1921) and Mohamed v Alaga & Co (A Firm) (2000). In such instances, where the contract is void, the issue is whether or not a party who is innocent of wrongdoing can recover a benefit conferred by the contract. As can be seen by the two decisions above, the result is that sometimes the benefit can be recovered, whereas in other cases it cannot. In the first case, Lord Atkin did not allow the plaintiff to enforce a contract which was expressly prohibited by statute. In the second case, the Court of Appeal found that while any contract to introduce refugees was prohibited by the legislation, it might be possible to recover on a quantum meruit† basis for the translation services provided in relation to the refugees. Translation services were not covered by the legislation and public policy would not be offended by allowing such a recovery. 12.1.3 Contracts that are illegal as performed A contract may be legal in its formation but illegal in its performance. This was the case in St John Shipping Corporation v Joseph Rank Ltd (1957) where a contract for the carriage of goods by sea was lawful in its formation but performed illegally when the shipowner overloaded the ship carrying the goods. The overloading was a statutory offence and the master of the ship was fined for this offence. The court held that the shipowner was entitled to recover the moneys owed for the freight. Devlin J distinguished between contracts which were entered into for the purpose of committing an unlawful act (which were unenforceable) and contracts which were expressly or impliedly prohibited by statute. The shipowner’s case was in the latter class. Because of this, the court needed to determine if the statute prohibited the formation of such contracts and, if so, did the particular contract before it fall within this prohibition. Two questions are involved. The first – and the one which hitherto has usually settled the matter – is: does the statute mean to prohibit contracts at all? But if this be answered in the affirmative, then one must ask: does this contract belong to the class which the statute intends to prohibit? …[here] an implied prohibition of loading does not necessarily extend to contracts for the carriage of goods by improperly loaded vessels. (per Devlin J) In Parkingeye Ltd v Somerfield Stores Ltd (2012) the court held that where a claimant’s contractual performance could have been carried out lawfully (and it had been intended to be carried out mainly lawfully), illegality was not a defence to the claim. In some cases, Parliament will declare that a certain type of contract is ‘void’. It may also provide that no action can be brought to recover a benefit derived from such a void contract. An example is s.4 of the Marine Insurance Act 1906 which provides that every contract of marine insurance by way of a gaming or wagering contract is void. Statutes may also provide that the performance, or a certain mode of performance, is illegal. † Quantum meruit: a partial payment (literal meaning: ‘as much as he/it deserves’). Contract law 12 Illegality Activity 12.1 Bertha is a dealer in poisons. The (fictitious) Control of Poisonous Substances Act 1966 requires that a dealer in poisons be registered under the Act and that no sale of poisons shall be made without the purchaser producing a ‘poison sale authorisation certificate’ from the Poisons Control Board. Bertha is a registered dealer. Arnold, who cannot be bothered to wait for the issue of the certificate, forges one and presents it to Bertha when he contracts with her to purchase rat poison. Bertha accepts the certificate as genuine and sells Arnold rat poison worth £200. Arnold takes the poison away and uses it. He now refuses to pay Bertha for the poison. Can Bertha recover the money owed? Activity 12.2 The same as above, except that Arnold does not produce any certificate, forged or otherwise. Activity 12.3 The same as above, except that Arnold produces a genuine certificate, however Bertha, in delivering the poison to Arnold’s premises, drives her van in excess of the speed limit and thus commits a criminal offence. Summary Contracts may be illegal as formed or illegal as performed. Where they are illegal as formed, and statute prohibits their creation, a court will not allow the recovery of damages under such a contract. Where an innocent party seeks some benefit from this contract, it may be allowed in some circumstances. Where a contract is illegal as performed, the court will seek to establish what was intended by the statute. 12.2 Common law illegality Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 15 ‘Illegality’ – Section 15.6 ‘Illegality at common law’ to Section 15.11 ‘Contracts prejudicial to public relations’ and Section 15.16 ‘The scope of public policy’. ¢¢ Treitel – Extract from Chapter 11 Section 2 ‘Types of illegality’, in your study pack. We are concerned here with those situations where the illegality affects a contract not by way of a statutory prohibition, but by way of a common law prohibition. Professor Treitel divides these situations into two categories. First are those cases involved in the commission of a legal wrong (the contract to commit a murder, for example); second are those cases which involve contracts contrary to public policy. For examples of cases in the first category, see Alexander v Rayson (1936) and Beresford v Royal Exchange Assurance (1938). Of the two, the second category is more troublesome because of the difficulty of ascertaining what the public policy is and whether or not the contract offends against it. Because of the changing nature of public policy, some of the older cases must be treated with care. It is unlikely, for example, that the contract in Pearce v Brooks (1866) to supply a brougham carriage to the defendant for use in her trade as a prostitute would now be considered illegal. Standards of morality may Figure 12.1 A brougham carriage change over time but also prevailing moral standards at one particular point in time will vary geographically as noted by the Malaysian Court of Appeal in Tengku Abdullah Sultan Abu Bakar v Mohd Latiff bin Shah (1996). page 181 page 182 University of London International Programmes Courts have found that public policy is offended in such a way as to make the contract illegal in a number of different areas. Thus, a contract which is contrary to good morals may be illegal. See not only Pearce v Brooks (1866), but also Franco v Bolton (1797) which involved payment by a man to a woman to become his mistress. Contracts to promote sexual immorality are now less likely to be found to be illegal due to the changing public conceptions of immorality. Contracts which are found to be prejudicial to family life are affected by illegality: see Lowe v Peers (1768) and Hermann v Charlesworth (1905). Thus contracts in which there was an agreement to restrain the freedom to marry, marriage brokerages, or some agreements to separate are illegal. Unsurprisingly, courts are concerned with the administration of justice and a contract which attempts to restrain this is illegal. See for example, R v Andrews (1973) and Elliott v Richardson (1870). Courts are particularly suspicious of agreements to oust the jurisdiction of the court. Another area in which contracts have offended public morals are those which tend to injure the state in its relations with other states. A contract with an alien enemy is illegal in time of war and contracts which contemplate hostile action to a friendly foreign country are also illegal. Another area in which public policy can be offended are those situations where the contract imposes a restraint of trade. These will be considered in Chapter 13 of the module guide. Activity 12.4 Compare the cases of Pearce v Brooks (1866) and Tinsley v Milligan (1994). What do these two cases tell us about the changing nature of public morality? Activity 12.5 How does a court determine what public policy is? Summary Contracts which offend public policy are difficult to categorise. Because public policy can change over time, conceptions of those contracts which offend it will also change. Useful further reading ¢¢ Andrews, Sections 20.17–20.18, for the impact of recent legislation concerning bribery. 12.3 The effects of illegality Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 15 ‘Illegality’ – Section 15.17 ‘The effects of illegality’ to Section 15.19 ‘Severance’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 16 ‘Illegality’ – Section 1 ‘Illegal contracts’. 12.3.1 The case law Because there is no single form of ‘illegality’ it is very difficult to ascertain the effect of illegality upon any one contract. The outcomes in the case law are very different. This is not surprising, given that the impropriety involved is very different in its seriousness. Before examining these different outcomes, it is worth bearing in mind that a contract may have both legal and illegal terms. Where it is possible to remove an illegal term or an illegal part of the term, a court can ‘sever’ that term and leave the remainder of the contract standing. Although a court will not generally enforce an illegal contract, in the past it has been possible to provide an ‘innocent party’ with a remedy in some other manner. Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Patel v Mirza (2016) the approach to the circumstances Contract law 12 Illegality of these exceptions may change. The majority of the justices would now rationalise these exceptions by reference to the multifactorial approach to the facts of individual cases which they endorsed. In contrast, the minority would continue to support these exceptions on the narrower and perhaps unnecessarily technical grounds originally articulated in the cases. In Strongman (1945) Ltd v Sincock (1955) the plaintiffs were unable to sue on the contract, but the court allowed them to recover the value of the work done on the basis of the breach of a collateral warranty. In Shelley v Paddock (1980) the innocent party was allowed damages for a fraudulent misrepresentation. Another important point is whether a party can be permitted to recover a benefit conferred upon the other party to an illegal contract. The general rule is that courts will not permit recovery under an illegal contract: Holman v Johnson (1775). There are, however, many cases which illustrate methods by which recovery will be allowed. Where the parties are said not to be in pari delicto (equally guilty) the public policy considerations in preventing illegal contracts may be outweighed by the desire to prevent the other party from retaining a benefit which constitutes an unjust enrichment. Thus in the case of Kiriri Cotton Co Ltd v Dewani (1960) the innocent party to an illegal contract was able to recover the money paid pursuant to the illegal contract. The party was ‘innocent’ in the sense that he was unaware that the contract was illegal. In another set of cases, the party has been allowed to recover a benefit when he withdraws from the contract before the illegality has been committed. See, for example, Taylor v Bowers (1876), Kearley v Thomson (1890) and Tribe v Tribe (1996). Exceptionally a benefit conferred by an illegal agreement may be recovered where the enterprise has become impossible as a result of the action or inaction of third parties so long as the performance of the illegal agreement has not otherwise begun (Patel v Mirza). Finally, cases exist which allow a party to recover a benefit where he can do so without relying on the illegal nature of the contract. These cases stem from the decision in Bowmakers Ltd v Barnet Instruments Ltd (1945) and the principle was extended by the House of Lords to equitable proprietary claims in Tinsley v Milligan (1994). In Patel v Mirza (2016) the majority of the Supreme Court disapproved of the first case and chose not to follow the second. In the circumstances of these two cases, relief could only now be justified by reference to the broader approach of the majority judgments in Patel v Mirza (2016). 12.3.2 Reform of the law The Law Commission considered a process of law reform in the area of illegality in contract. In 1999 The Law Commission produced a consultation paper ‘Illegal transactions: the effect of illegality on contracts and trusts’ (see ‘Further reading’ below). The Law Commission sought the reform of this area of law and made some provisional recommendations. The most important of these recommendations was that courts would possess a discretion to ‘decide whether or not to enforce an illegal transaction, to recognise that property rights have been transferred or created by it, or to allow benefits conferred under it to be recovered.’ This discretion would not, however, be open-ended to allow the court to do what it considered ‘just’ in the circumstances. This discretion would be structured to provide certainty and guidance (and the report considers the nature of this guidance) – and this guidance would apply only where a statute did not expressly prohibit the transaction. The Law Commission in 2009 decided, however, to abandon the proposal for a general discretion with the recommendation that the law be developed by the courts in an incremental fashion. However, as Lord Sumption noted in Patel v Mirza (2016) the multifactorial approach of the majority in that case ultimately derived from the Law Commission’s unimplemented consultation paper. page 183 page 184 University of London International Programmes Self-assessment questions 1. Give an example of a contract that would be illegal as formed. 2. Give an example of a contract that would be illegal as performed. 3. Summarise the matters the Law Commission states a court should consider when exercising the proposed discretion set out in consultation paper 154. 4. What is meant by the term ‘locus poenitentiae’? 5. What is meant by the term ‘in pari delicto’? 6. What general rule is derived from Holman v Johnson (1775)? Summary As a general rule, a contract tainted by illegality cannot be enforced. It is possible, however, that a remedy may be obtained by another course of action. Courts will also, in certain circumstances, allow the recovery of money or property which has been transferred in accordance with an illegal contract. Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 11 ‘Illegality’. ¢¢ The Law Commission’s 1999 consultation paper, ‘Illegal transactions: the effect of illegality on contracts and trusts’ (LCCP No. 154) avaialable from BAILII. Examination advice A review of past examination papers reveals that this area has generally been examined as a question on its own. Past questions have taken two forms. First, problem questions in which candidates have been asked to ascertain the enforceability of illegal contracts and/or the ability to recover a benefit conferred under the illegal contract. Secondly, the examiners have asked essay questions in which candidates needed to critically discuss certain aspects of the law in this area. Sample examination question Peter was a licensed dealer in pet food under the (fictional) Licensing of Pet Food Act 2001. Section 1 of the Act requires any person selling pet food to be licensed and if ‘anyone shall trade in pet food without the appropriate licence he shall be guilty of a criminal offence’. Section 2 requires sales of pet food to be accompanied by a ‘statutory invoice’ which must contain details of the food supplied and a statement of the quantity supplied. a. Peter supplied Queenie with pet food costing £500 but failed to provide a statutory invoice at the time of delivery because it had fallen out of the box in which it had been placed by Peter’s employee. Queenie refused to pay for the pet food. b. Peter supplied Robert with pet food but failed to provide a statutory invoice after Robert said, ‘Between friends no formalities are required’. Robert refused to pay for the pet food and claimed damages from Peter because, he claimed, the pet food was of poor quality. c. Peter was paid £600 by Stefan for pet food to be delivered to Stefan’s restaurant. Peter suspected that Stefan might be using the food for human consumption (which was prohibited by statute). It was subsequently discovered that Stefan was using the pet food for this purpose. Stefan sought the repayment of the £600. d. Peter agreed to supply pet food costing £2,000 to Thomas which Thomas paid for in advance. It was then discovered that, unknown to Peter, his licence had expired. Peter refused to deliver the pet food to Thomas or to return the £2,000 which Thomas had paid in advance. Advise the parties. Contract law 12 Illegality Advice on answering the question The question calls for a determination of the extent to which courts will enforce a contract despite the taint of illegality. Here the illegality is created by statute. The starting point to such an answer is to consider the purpose behind the statutory requirements. Following St John Shipping v Rank, the issue to be considered in all four parts of the question is the purpose behind the statute. Is the statute intended to penalise conduct or to prohibit contracts? The requirement to provide an invoice appears to regulate the conduct of the business rather than the legality of the business. This would indicate that contracts which do not comply with this requirement are illegal as performed rather than illegal as formed. On the other hand, the requirement that the dealer must be licensed indicates that the purpose of the requirement is to make unlicensed agreements illegal as formed. The facts provided do not make clear at what point Peter’s licence has expired. Nor does the question state whether or not the statute provides for the consequences of illegality. Parts (a) and (b) deal with the requirement that the pet food dealer must supply a statutory invoice with the pet food. In part (a) Peter attempts to supply Queenie with the invoice but fails to do so because it falls out of the box in which it has been placed. There has been an attempt to comply with the statute and in this sense Peter may be ‘innocent’ in the sense that he is unaware of the illegality. In some circumstances, courts have allowed such contracts to be enforced (see Archbolds (Freightage) v Spanglett). In other cases, courts have not allowed the contract to be enforced (see Re Mahmoud and Ispahani and Mohamed v Alaga and Co (2000)). Where the statute does not specify the consequences of the illegality on contracts, the better view is that the effects should be determined by reference to the statute. Here it is arguable that the purposes of the statute would not be furthered by denying Peter the remuneration due under his agreement with Queenie. Peter may be able to recover on a quantum valebat basis for the goods supplied (Mohammed v Alaga) but not if public policy would prevent such a restitutionary recovery (Awwad v Geraghty & Co). However, if Peter’s licence has expired, the contract is illegal as formed and thus unenforceable by either party. Part (b) differs subtly from part (a) in that both Peter and Robert are aware that the contract is illegal because it lacks the statutory invoice. Both are assenting to a performance they know is illegal. The parties are in pari delicto and neither can sue on the contract. Peter cannot obtain the remuneration stipulated in the agreement and Robert cannot obtain damages for the allegedly poor quality of the pet food supplied. In part (c), Peter is probably aware that subject matter of the contract will be used for an unlawful purpose and thus the contract is illegal. Peter’s awareness may make him a participant in the illegality (Ashmore, Benson, Pease & Co v AV Dawson Ltd (1973)). The contract is unenforceable and Stefan cannot recover the £600 advanced in contract. However, as the illegality has not been perpetrated with respect to the particular delivery of pet food, Stefan may be able to recover the moneys paid to Peter on a restitutionary basis. Stefan must repudiate the contract before the illegal purpose has been performed. In part (d), Peter’s licence has definitely expired and the contract is illegal as formed and thus unenforceable by either party. page 185 page 186 University of London International Programmes Quick quiz Question 1 In St John Shipping v Joseph Rank Ltd (1957), Devlin J allowed the shipowners to recover the additional cargo carried by the ship when it was overloaded in contravention of the Merchant Shipping (Safety and Load Line Conventions) Act 1932 because (choose one answer): a. The 1932 Act did not prevent the suit upon the contract because the infringement of a statute in the performance of a contract legal when made did not make the contract illegal unless the contract as performed was one which the statute intended to prohibit. b. The shipowners had not intended to contravene the statute and when the vessel left her loading port she had three-eighths of an inch to spare without an offence being committed. c. An offence against the 1932 Act was a trivial matter and ought not to prevent the shipowners from the profit owed to them after completing the voyage and paying the fine. d. The shipowners could sue because they had not intended to commit an offence under the 1932 Act and the owners of the cargo were not disadvantaged by the offence. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Where a contract is legal in its formation but illegal in its performance which of the following statements is true? Choose one answer. a. Neither party can enforce the contract. b. Both parties can enforce the contract. c. The party who has caused the illegal performance can enforce the contract provided he was unaware of the illegality of the performance. d. The party innocent of the illegality in performance can enforce the contract, particularly if he was unaware of the illegality. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following contracts is not necessarily illegal? Choose one answer. a. A contract whereby A wagers with B that A’s dog will run across the town square faster than B’s dog. b. A contract in which A and B agree that, in the event of a dispute, the matter will not be taken to court. c. A contract in which A and B agree that B will murder C in exchange for A’s payment of £10,000. d. A contract in which A and B agree that A will find B a husband in exchange for B’s payment of £10,000. e. Don’t know. Contract law 12 Illegality Question 4 An illegal contract will not be enforced by the courts and a court will not allow any form of recovery in which of the following instances? Choose one answer. a. By allowing the innocent party to sue on a collateral warranty to the main contract. b. By allowing the innocent party to recover damages for fraudulent misrepresentation. c. By allowing the innocent party to bring a restitutionary claim to recover benefits conferred. d. By waiving any knowledge of the illegality the innocent party can enforce the contract. e. Don’t know. Question 5 In Tinsley v Milligan (1994) the court held that the claimant was entitled to an interest in property despite fraudulent claims on the Department of Social Security for which reason? Choose one. a. The House of Lords were unconcerned that the parties to the agreement were homosexuals. b. A claimant to an interest in property, whether based on a legal or equitable title, was allowed to recover where she was not forced to plead or rely on an illegality. c. No court will lend its aid to a man who founds his cause of action upon an immoral or illegal act. d. If A puts property in the name of B intending to conceal his (A’s) interest in the property for a fraudulent or illegal purpose, neither law nor equity will allow A to recover the property, and equity will not assist him in asserting an equitable interest in it. This principle applies whether the transaction takes the form of a transfer of property by A to B, or the purchase by A of property in the name of B. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the subject guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What are the differences between contracts which are illegal in formation and contracts which are illegal in performance? 2. What different effects result from the above distinction? 3. In what different situations will a court find that a contract offends against public policy? 4. What are the consequences of a finding that the contract is illegal? 5. What major reform of the law has been proposed in this area and, if any has, to what extent has it been implemented? page 187 page 188 Notes University of London International Programmes Part VI Illegality and public policy 13 Restraint of trade Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190 13.1 General principles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191 13.2 Employment contracts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191 13.3 The sale of a business . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 193 13.4 Other agreements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 196 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197 page 190 University of London International Programmes Introduction The material considered in this chapter is a species of the public policy considered in the previous chapter on illegality. A contract containing a clause to restrain a person’s freedom to trade may be offensive to public policy and, as such, be unenforceable. For example, one party may contract to sell her business to another. A common clause in such a contract is one which prevents the vendor from then opening a competitive business next door and so ‘siphoning off’ customers of the business that has been sold to another business owned by the vendor. Such a clause restrains the freedom of the vendor to trade. Such a clause is only valid to the extent it is reasonable, since it offends public policy to restrain the freedom of an individual for a disproportionate period of time. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the concept of restraint of trade and its effect upon contracts entered, to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The different contractual contexts in which restraint of trade can arise. uu The circumstances when an employment contract will be found to be in restraint of trade. uu The circumstances when a contract to sell a business will be found to be in restraint of trade. uu The differences of approach by courts to restraint of trade clauses in an employment contract and in the sale of a business. uu When might a court consider a clause to be an offensive restraint of trade in other circumstances? uu What is an unacceptable restraint of trade? Contract law 13 Restraint of trade 13.1 General principles Restraint of trade has been considered primarily in two contexts. The first is in an employment context – an employee may contract with his employer that, among other things, he will not work for a competitor of the employer while employed or for a period of time after his employment has ended. The second is where a business is sold and the purchaser seeks an undertaking from the vendor not to compete with him. Both employers and purchasers have legitimate interests to protect. To an extent, what they are contracting over is the exclusive services of the employee or the lack of competition from the former owner. Where the employee provides unique services to the employer, or where he has valuable inside knowledge of the employer’s business, the employer can act legitimately to confine these services or knowledge. In the case of the sale of a business, the purchaser often buys the established trade and ‘goodwill’ of the business. If the seller were able to establish a rival business in the same area, this trade and goodwill would be valueless. The problem is that the agreements can work against the public interest, in that the public is deprived of the abilities of the other party to the contract. There is a corresponding danger that the restraint works unfairly against the interests of the party restrained. For these reasons, courts will only enforce a restraint of trade clause to the extent that it is reasonable. Thus, the party who seeks to enforce the clause must show that it is reasonable between the parties and reasonable in the public interest. In some cases, it may be possible for a court to sever the term which is in restraint of trade and leave the remainder of the contract in force. In addition, there are statutory controls upon anti-competitive agreements. These are now to be found, principally, in Articles 101 and 82 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (formerly Article 85 and then 81 of prior Treaty Agreements) and the relevant provisions of the Competition Act 1998. These controls are of more recent origin than the common law doctrines and broader in scope. They are principally administered by regulatory authorities. Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, paras 11-105 to 11-109, for the best summary of European and UK competition law as it affects this topic. 13.2 Employment contracts Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 15: ‘Illegality’ – Section 15.12 ‘Contracts in restraint of trade’ and Section 15.13 ‘Contracts of employment’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 16: ‘Illegality’ – Section 2 ‘Contracts void on grounds of public policy: contracts in restraint of trade’. During the employment contract, it is legitimate for an employer to stipulate that he or she requires the exclusive services of the employee. Accordingly, such a restraint will stand unless it is exceptionally onerous – for example, if the restraint has as its purpose the prevention of the employee working altogether. A term will be considered for its reasonableness when it seeks to impose a restraint after the employment relationship has ended. For example, a major computer software company employs a programmer. One of the terms of the contract is that the programmer will not work for another company in the computer business for a period of time after the programmer has left the software company. The computer software company obviously wishes to protect its confidential information and, possibly, its customers, from competition. These can be legitimate interests. The programmer, however, will need to earn a living. The law must balance these two interests. Whether or not the restraint can stand will be determined by two criteria: 1. the restraint must be reasonable between the parties – it must do no more than is reasonably necessary for the protection of the employer page 191 page 192 University of London International Programmes 2. the restraint must not be injurious to the public – it must also be reasonable in the interests of the public. In practice, the first criterion will be more difficult to establish than the second. This is because the courts are generally reluctant to find that a clause which is reasonable between the parties is not reasonable in the interests of the public. There are two criteria to the requirement that the clause must be reasonable between the parties. First, the clause must protect some legitimate interest of the employer. It must not be used simply to prevent competition with the employer. The employee must be free to exercise the general skills and knowledge he possesses. See, for example, Herbert Morris Limited v Saxelby (1916). Secondly, in protecting this legitimate interest, the restriction must be reasonable with regard to three elements: subject matter, area, and duration. See, for example, Mason v Provident Clothing & Supply Company Ltd (1913). Once a court has established that a clause is reasonable between the parties, it is unlikely to find that it is contrary to the public interest. Note, however, the decision in Wyatt v Kreglinger and Fernau (1933) in which this point was considered. In Proactive Sports Management Ltd v Rooney (2011), the Court of Appeal held that a footballer’s ancillary activity of exploiting his image rights was equally capable of protection under the doctrine of restraint of trade as any other occupation. Analogous principles to the above will apply to agency, as opposed to employment, contracts (BCM Group plc v Visualmark Ltd [2006] EWHC 1831). Activity 13.1 Amanda is a saleswoman of exceptional ability. She is able to persuade most people to buy whatever product she has on offer. She works for Plod Products Ltd selling paper products to the public. Her contract of employment prevents her from selling any product within a 300km radius of Plod’s head office for six months after leaving their employment. Amanda is offered a job selling the pen and ink products of FabuMats Ltd. Although FabuMats Ltd sells paper, Amanda will not be engaged in the sale of paper. Amanda resigns her position with Plod Products and takes up the position with FabuMats. Plod Products seeks an injunction to prevent her from selling FabuMats’ products. Advise Amanda. Activity 13.2 Mega-Pharmaceuticals employs Dorothy, a scientist of exceptional ability. Dorothy is hired to undertake research for a cure for HIV/Aids. The contract of employment provides, among other things, that on leaving Mega-Pharmaceuticals, Dorothy will not undertake research privately or for any other employer. This restriction is for a period of five years following her employment with Mega-Pharmaceuticals and applies worldwide. Mega-Pharmaceuticals will pay Dorothy the equivalent of five years’ salary. Dorothy leads the world in this research. When she is very close to a major breakthrough, she is offered a post at Enormo-Pharmaceuticals. Her duties there would include heading a research team engaged in HIV/Aids research. Mega-Pharmaceuticals declares that they would rely on the term of the contract preventing Dorothy from undertaking research in this area. Can they do so? Summary A party who seeks to enforce a restraint of trade clause in an employment contract must establish that: 1. he has a legitimate interest to protect 2. the clause is reasonable between the parties as to subject matter, area and duration, and 3. the clause is not injurious to the public. Contract law 13 Restraint of trade Further reading ¢¢ Smith, S.A. ‘Reconstructing restraint of trade’ (1995) 15 OJLS 565. 13.3 The sale of a business Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 15: ‘Illegality’ – Section 15.14 ‘Contracts for the sale of a business’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 16: ‘Illegality’ – Section 2 ‘Contracts void on grounds of public policy: contracts in restraint of trade’. The modern law in this area was established by Nordenfelt v Maxim Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Co (1894). When a business is sold, the purchaser is wise to insist on a restraint of trade clause to prevent the vendor from drawing the business to another establishment. The purchaser has often bought the goodwill and custom of that business and this is protected by a restraint of trade clause. Not many purchasers would pay significant sums if they thought the vendor could establish a rival business. Because the covenant is a part of what is bought, there is an important difference between clauses in restraint of trade in an employment contract and in a contract for the sale of a business. The result of this difference is that courts are much more likely to uphold a restraint of trade clause found in a contract for the sale of a business than in a contract of employment. The criteria for determining whether or not a restraint of trade clause in a contract for the sale of a business is enforceable are much the same as in an employment contract. The party seeking to enforce the clause must show that the clause is reasonable in the interests of the parties to the contract. In determining this reasonableness, courts will have regard to the consideration paid for the business. The clause must be reasonable in light of the interests of both parties. In Nordenfelt v Maxim Nordenfelt, the House of Lords believed that a covenant not to compete in any future business undertaken by the business was unreasonable because it sought to protect the future activities of the business. The House of Lords did, however, find that a worldwide restriction was reasonable because of the limited number of manufacturers in this area. Once it has been established that the clause is reasonable, it must be established that it is not contrary to the public interest. In practice, it is probably the party who seeks the removal of the clause who will raise this point. Activity 13.3 Taylor Skate Ltd is a company which manufactures ice skates. The company is wholly owned by Cyril Taylor, a metallurgical engineer who has developed most of the Taylor Skate products himself. Mr Taylor sells his company to Mr Shore for £10 million. As a part of the sale agreement, Mr Taylor promises not to open a rival business or to solicit the customers of Taylor Skate Ltd either for himself or in the employ of any other company. In addition, he further promises not to work anywhere in the world in any business which produces any product produced by Taylor Skate Ltd either now or in the future. He agrees to refrain from such activities for a period of 30 years. Four years later, Mr Taylor develops an anti-rust coating for metal exposed to damp. When he forms a new company to develop this product for use, he discovers that Taylor Skate Ltd has begun to develop a similar coating for use on a new product. Taylor Skate Ltd warn Mr Taylor that they will not tolerate such competition. Advise Mr Taylor. Summary The criteria necessary to uphold a restraint of trade clause in the sale of a business are broadly the same as those to uphold the same clause in an employment contract. The difference is that the public interest is less likely to be offended. This may be because the public interest is now considered to be protected by competition legislation. page 193 page 194 University of London International Programmes 13.4 Other agreements Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 15: ‘Illegality’ – Section 15.15 ‘Restrictive trading and analogous agreements’ and Section 15.16 ‘The scope of public policy’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 16: ‘Illegality’ – Section 2 ‘Contracts void on grounds of public policy: contracts in restraint of trade’. Traditionally the doctrine of restraint of trade was applied to employment agreements and agreements for the sale of a business. This doctrine has also been applied to other forms of agreement. The extent of this possible application to other agreements is uncertain. We consider here two forms of agreements to which the doctrine has been applied: solus agreements and exclusive service agreements. One form of agreement to which it has been applied is a ‘solus’ or exclusive dealing agreement. This is a contract whereby one party undertakes to purchase all of its supplies from a certain supplier. In Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Harper’s Garage (Stourport) Ltd (1968), the House of Lords held that such an agreement was within the scope of the doctrine of restraint of trade. In that case, Harper had agreed to buy his petrol exclusively from Esso for a period of four years, five months in relation to one of his garages and for 21 years with respect to another. In relation to the second garage, the promise was given in connection with a loan from Esso. The House of Lords established that the period with respect to the first garage was not a restraint of trade, but that the second one was. Twenty-one years went beyond what was required to protect the interests of Esso. The doctrine of restraint of trade has also been applied to exclusive service agreements. In these agreements, one party promises to provide their services only to the other party and not to work for anyone else. In A Schroeder Music Publishing v Macaulay (1974), the court found that the exclusive service agreement was a restraint of trade and thus unenforceable. In that instance, a young songwriter had contracted with music publishers to provide his exclusive services for five years. During that period, the songwriter assigned copyright in his music to the publishers. The music publishers were under no obligation to do anything with his songs. In the event that the songwriter’s royalties exceeded a certain amount, the contract would be automatically extended for a further five-year period. While the music publishers were able to terminate the contract, the songwriter was not given this right. The House of Lords applied their decision in Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Harper’s Garage (Stourport) Ltd and found that the case was an unenforceable restraint of trade because it went well beyond what was necessary to protect the interests of the music publishers and so severely curtailed the abilities of the songwriter. Summary In a variety of situations beyond employment contracts and contracts for the sale of a business, courts will consider whether or not the clause is a restraint of trade. While the scope of this application is uncertain, the indications are that it will occur in circumstances similar to employment contracts or in situations where one party ties himself or herself to another. Activity 13.4 Review the judgments in Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Harper’s Garage (Stourport) Ltd and A Schroeder Music Publishing Co Ltd v Macaulay. What reasons do the judges give for considering the contractual terms in these cases in light of the doctrine of restraint of trade? Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 11: ‘Illegality’, Section 4 ‘Common law and statutory control of anti-competitive agreements’ (this section contains considerable detail across this topic). Contract law 13 Restraint of trade Self-assessment questions 1. When does a restraint of trade occur? 2. What factors will a court consider in determining the public interest in relation to a restraint of trade clause? 3. How does the approach of the courts differ in dealing with a restraint of trade clause in a sale of a business and that of an employment relationship? 4. Why have courts included other sorts of agreements within the scope of the restraint of trade doctrine? 5. What is the effect of the court finding that a term is an unjustifiable restraint of trade? 6. What legislation will also regulate many restraint of trade clauses and arrangements? Examination advice You are reminded of the general advice given in the first chapter of this guide. In particular, this advice is meant to assist candidates by examining past examination papers. It is in no way determinative of what the examiners in this subject may do in the future. A review of past examination papers reveals that questions involving restraint of trade have tended to form a part of a larger question on the topic of illegality. Sample examination question Bob and Ted were in partnership as surveyors and valuers. Each covenanted with the other that he would not, during the time they were in partnership or within five years thereafter, practise within eight miles (12 km) of their present office or any other office in which the other should thereafter practise. Bob later took on Albert as an articled clerk and Albert covenanted that he would not, while employed by Bob or within 10 years of ceasing to be so employed, practise within eight miles of Bob’s office or any office in which Bob should thereafter practise as a surveyor, valuer or estate agent. A year ago the partnership between Bob and Ted was dissolved and Albert ceased to be employed by Bob. Both Ted and Albert are now practising within eight miles of Bob’s office. Advise Bob. Advice on answering the question Bob will want to enforce both his agreements to ensure that neither Ted nor Albert practise near his office. It is likely that Ted and Albert will argue that their respective agreements are unenforceable because they are an unacceptable restraint of trade. Because there are two agreements, it is best to consider them in turn. In relation to the first agreement between Bob and Ted, Bob will need to establish that this restraint of trade is reasonable. He will need to do this by showing that he has a legitimate interest to protect, that restraint is reasonable between the parties and that it is reasonable in the public interest. While the agreement does not occur within the sale of a business, it occurs within a similar context and thus the cases dealing with these are best considered (such as Nordenfelt v Maxim Nordenfelt). Bob would also be advised to point out that his situation differs greatly from those encountered by the court in the solus agreement cases. It is particularly notable that Bob and Ted have exchanged exactly the same promise – Bob has bound himself to the same conditions. With regard to the second agreement with Albert, this is an employment agreement. Once again, Bob will need to establish that the clause is not an unacceptable restraint of trade. To do this he needs to establish that: (1) he has a legitimate interest to protect; (2) the clause is reasonable between Bob and Albert as to subject matter, area and duration; and (3) that the clause is not injurious to the public (see Herbert page 195 page 196 University of London International Programmes Morris Limited v Saxelby (1916)). Bob’s difficulty here will relate to (2) because it seems unreasonable to bind Albert for ten years and even more unreasonable to extend this to any office in which Bob might work in the future. On balance, it is likely that the first agreement is enforceable, but that the second agreement is not. Quick quiz Question 1 In which of the following circumstances was the contract found to have created a restraint of trade which was unreasonable and thus unenforceable? Choose one answer. a. A solicitor’s managing clerk of a specified place entered into a covenant that after leaving his employer he would not, for the rest of his life, practise as a solicitor within seven miles of the town hall of the specified place. b. A canvasser who is employed to sell clothes in a specified area entered into a covenant that he would not enter into a similar business within 25 miles of the city to which the specified area belonged. c. A highly specialised Swedish seller of armaments entered into a covenant with an English purchaser that they would never sell armaments again. d. A doctor who works as a General Practitioner enters into a covenant not to practise as a General Practitioner again. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Which of the following statements is untrue? Choose one. a. Restraints of trade are no longer prima facie valid but are now prima facie void, but can be justified if they are reasonable and not contrary to the public interest. b. Restraints of trade will be allowed where they are agreed by the parties. c. It is no longer essential that the consideration should be adequate. d. The law no longer establishes as a rule that the restraint must not be general. e. Don’t know. Question 3 In considering whether or not to allow a clause which acts as a restraint of trade in an employment contract, which of the following matters is not a factor considered important by courts in making this determination? Choose one answer. a. The extent of the physical area sought to be covered by the clause. b. The imprecise definition of the physical area sought to be covered by the clause. c. The type of business the employer is engaged in and for the purpose he has hired the employee within this business. d. The duration of the clause. e. Don’t know. Contract law 13 Restraint of trade Question 4 Which of the following statements best summarises the approach taken by courts towards the enforcement of a clause which amounts to a restraint of trade? Choose one answer. a. Courts will enforce the clause where the nature of the industry or business requires it. b. Courts will enforce the clause where the employee has acquired information concerned with the running of the employer’s business. c. Courts will enforce the clause where it is in the national interest to do so. d. Courts will enforce the clause where it is in the reasonable interests of the employer to do so. e. Don’t know. Question 5 In Nordenfelt v Maxim Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Co (1894), Lord Macnaughten made which of the following statements? Choose one answer. a. All restraints of trade are contrary to public policy and therefore void, although the law allows that restraints of trade and interference with individual liberty of action are exceptions to this general rule and may be justified in certain circumstances. b. Restraints of trade are consistent with public policy in a market economy and are thus necessary to protect the functioning of the market. c. Restraints of trade are justified where reasonable and as such allowed. d. Restraints of trade are reasonable with reference to the protection of the public. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. In what different contractual contexts can restraint of trade arise? 2. In what circumstances will an employment contract be found to be in restraint of trade? 3. When will a restraint of trade clause in the sale of a business be unenforceable? 4. What are the differences of approach by courts to restraint of trade clauses in an employment contract and in the sale of a business? 5. When might a court consider a clause to be an offensive restraint of trade in other circumstances? 6. What is the effect upon the contract of an unacceptable restraint of trade? page 197 page 198 Notes University of London International Programmes Part VII The discharge of a contract 14 Performance and breach Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200 14.1 The principle of substantial performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201 14.2 When a breach of contract occurs (‘actual breach’) . . . . . . . . . . . 202 14.3 What occurs upon breach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204 14.4 Anticipatory breach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 205 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 208 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209 page 200 University of London International Programmes Introduction This chapter is concerned with the performance and discharge of contracts. Contracts will be discharged, that is to say, ended, in one of four general ways. The first is through performance; the second is by the agreement of the parties; the third is by breach; and the fourth is by frustration. In the first instance, the parties have fulfilled their contractual obligations and the contract is at an end. Despite the impression you may have from the cases you have already read, complete performance is the most common end to a contract. The parties may also decide to end further performance of their contract by entering into a (subsequent) binding contract to end their first contract. Such an agreement is sometimes confusingly called rescission but must be distinguished from rescission for misrepresentation which we examined in Chapter 9, Section 9.2.1. In the third instance, one or more parties have not performed their contractual obligations and this non-performance arises through the fault of one or more of the parties. In the final instance, the contract is discharged by a supervening event which occurs without the fault of either party. This is known as frustration and is dealt with in Chapter 15. This chapter deals with the first and third ways in which a contract is discharged: by performance and by breach. The categories are closely related of course because breach is no more than a defective performance. The focus of this chapter is primarily upon breach of contract. We are concerned here with situations where the performance tendered is below the standard required by the contract or one party refuses to perform or disables themselves from performing. A party could disable themselves from performing in many ways. They could, for example, take on an additional and conflicting commitment with another party. Alternatively, they might remove the means by which they would perform the contract or give up control over the place of performance. We are concerned with what result in law attends upon one of these events. In examining the material in this chapter, you will find it useful to consider the nature of the terms of the contract discussed in Chapter 5. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the discharge of contractual obligations as a result of the performance or the breach of a contract, to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The concepts of an ‘entire’ contract and substantial performance. uu The standard of performance required in different contracts. uu The definition and operation of repudiatory breaches of contract. uu The circumstances when an innocent party terminates a contract for breach. uu The remedial consequences that occur when there has been a breach of contract. Contract law 14 Performance and breach 14.1 The principle of substantial performance Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 22 ‘Obtaining an adequate remedy’ – Section 22.2 ‘The entire obligations (or “entire contracts”) rule’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 8 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 4 ‘Entire obligations’. A contract requires performance of the promised obligation. One issue is if the performance is sufficient to satisfy the promise. Some contracts are ‘entire obligation’ contracts. This means that nothing but 100 per cent performance will satisfy the obligation. It is said that, as a general rule, a party cannot recover payment for the partial performance of an ‘entire obligation’. What this means is that until the entire obligation is performed, the party performing the obligation cannot recover any payment for it. It may be the ‘entire obligation’ is the whole, or entire, contract. An example of such a situation can be seen in the case of Cutter v Powell (1795). In this case, Cutter contracted with Powell to be the second mate on a ship bound from Jamaica to England. Cutter was to be paid 10 days after the ship arrived in Liverpool provided that ‘he proceeds, continues and does his duty as second mate in the said ship from hence to the port of Liverpool’. Cutter died shortly before the ship reached Liverpool and his widow sued to recover payment for the period of time in which Cutter had acted as second mate. This payment was denied because the contract was not fully performed. There was no pay until the performance was complete: an entire contract requires entire performance to entitle the performer to payment. There is no partial payment for partial performance. These obligations are rare in practice as the rule is harsh. A similar rule may be applied in a domestic context. In Bolton v Mahadeva [1972] 1 WLR 1009 the obligation to install a central heating system was held to be entire. Consequently, the contractor was unable to recover any of the £560 contract price payable on completion when the installation was defective and would cost a further £174 to complete. The ability to stipulate that payment will not be made until performance is complete may be the only effective way householders can ensure the prompt and proper performance of small building works (as noted by Brian Davenport QC in his ‘dissent’ to the Law Commission’s Report on Pecuniary Restitution for Breach of Contract No 121 (1983)). In contrast, most high value commercial contracts will typically involve payment in instalments. In Smales v Lea [2011] EWCA Civ 1325 the Court of Appeal noted that it was ‘relatively unusual’ in commercial construction contracts and contracts for professional services for the payment obligation to be entire. The harshness of this general rule is mitigated by a variety of methods that allow a party to receive some recompense for a partial performance. First, a court may interpret the contract not as being an entire contract, but as a contract which is made up of a series of ‘entire obligations’. The contract is thus divided into a series of stages of performance. When a stage has been completed, the performer can recover payment for this stage. A second method is that courts will allow recovery where a party in breach has substantially performed his obligations. If the performance has been substantially performed then the breach is of minimal consequence (a breach of a warranty). See, for example, Hoenig v Isaacs [1952] 2 All ER 176, where decoration work that was to cost £750 was incomplete in minor ways that would cost £55 to remedy. One issue that is often argued is the performance is not substantial but is in fact only partial performance. Third, the general rule is subject to a statutory exception when the buyer does not contract as a consumer; the buyer is not allowed to reject the goods for a delivery shortfall (or excess) which is so slight that it would not be ‘reasonable’ to do so (Sale of Goods Act 1979 s.30(2A)). The innocent party may be liable to compensate the performer for a partial performance where the innocent party accepts the partial performance. The difficulty with this is that the other party may have no choice but to accept the partial performance, although they contracted not for a page 201 page 202 University of London International Programmes partial performance but for a complete performance. This was the case in Sumpter v Hedges (1898). The Law Commission, in the report referred to above, thought that the requirement in the cases that an ‘accepted’ benefit need only be paid for when the ‘acceptor’ had a real choice whether to accept or not, was too restrictive. They therefore recommended that a more generous right to recovery be enacted but this proposal has not been implemented. However, the Consumer Rights Act 2015 s.25(1) provides that if a trader delivers the wrong quantity of goods to a consumer and the consumer nonetheless accepts them they must be paid for at the contract rate. Summary It is said that where the contract, or obligation, is ‘entire’ then all of the obligation must be performed in order to entitle the performing party to any payment for performance. In practice, however, it may be possible to recover payment in circumstances where the entire contract has not been performed. Further reading ¢¢ Burrows, A.S. ‘Law Commission Report on Pecuniary Restitution on Breach of Contract’ (1984) 47 MLR 76. 14.2 When a breach of contract occurs (‘actual breach’) Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 20 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 20.1 ‘Introduction: breach defined’ to Section 20.3 ‘The consequences of breach’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 8 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 1 ‘Absolute and qualified contractual obligations’. ¢¢ Brownsword, R. ‘Retrieving reasons, retrieving rationality? A new look at the right to withdraw for breach of contract’, in your study pack. It is often difficult to ascertain if a breach of contract has occurred. In some cases, where one party refuses to continue performing or commits an act which prevents further performance, it is clear that a breach of contract has occurred. This is a repudiatory breach. However, in cases where there is a partial performance or an inadequate performance, it is often difficult to determine whether or not such a repudiatory breach has occurred. In this sense, a repudiatory breach is a breach which entitles the innocent party to terminate the contract. A party who alleges that a repudiatory breach has occurred must prove that it has occurred. Whether or not a repudiatory breach has occurred depends upon the terms of the contract. Two matters must be considered in relation to the particular terms or obligations of the contract. The first is the standard of performance to be met in the contract. The second is the type of term breached. The type of breach discussed in this section is sometimes called ‘actual’ breach of contract. This refers to the fact that the time for contractual performance has arrived and the promisor has failed to deliver that performance. As such it is distinguished from so called ‘anticipatory’ breach, discussed below in Section 14.4, where before performance is due the promisor either announces that when that time arrives he will not tender performance or in advance of that date disables himself from being able to give that performance. Standard of performance With regard to the first matter, different terms impose different standards of performance. These can be divided into two general standards: strict liability and a standard of reasonable care. A standard of strict liability is one in which either performance measures up to what is demanded by the contract or it does not. The fault of the party in breach in not measuring up to this standard is irrelevant. A standard of reasonable care, in contrast, imposes a duty on the party to use reasonable care and skill in the performance of her contractual obligations. Contract law 14 Performance and breach Strict liability As a general rule, contracts for the supply of goods impose a strict standard of performance with regard to the quality and quantity of the goods to be supplied. Thus, a contract to supply barrel staves which were half an inch (8/16th of an inch) thick was not performed when the staves supplied were of varying thickness from 7/16ths of an inch thick to 9/16ths of an inch thick (Arcos v Ronaasen (1933)). The fault of the party who supplies the goods is immaterial; that is to say, it does not matter that the barrel staves were the wrong thickness through no fault of his own. It may be that the party in breach exercised all reasonable care to ensure that the goods conformed to the standard required; she is, however, still in breach of contract. The liability is strict and fault need not be proved. A strict standard of performance may be imposed by the legislation – for example, the obligations imposed upon a seller of goods under the ss.13–15 Sale of Goods Act 1979 are strict. Reasonable care and skill In contrast, some contractual terms impose a lower standard of performance – a standard which requires that reasonable care and skill is exercised. In these cases, the fault of the party in breach is relevant. Again, as a general rule, contracts for the supply of services require that the party exercise reasonable care and skill in the performance of her contractual obligations. Thus, s.13 of the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982 requires a party to exercise reasonable care and skill in the supply of a service. With regard to the second matter (i.e. the type of contractual term which has been breached) you should refer to Chapter 5. You will recall that terms can be classified as conditions, warranties or intermediate/innominate terms. The classification of terms is particularly important in relation to a breach of contract because not all breaches give rise to a right to terminate the contract. Only the breach of a condition, or a sufficiently important intermediate/innominate term, gives rise to a right to terminate the contract. Activity 14.1 Mountain Magic Ltd is purchasing a mountain upon which it plans to develop a ski resort. The contract for the purchase requires that it tenders payment of £10 million at 5:00 pm on 3 December at the offices of the vendor, Tighte Fist plc. On 3 December, Mountain Magic Ltd sends a representative with a cheque for payment to the offices of Tighte Fist plc. The representative leaves with plenty of time to reach his destination. Unfortunately, a bomb scare forces police to prohibit all travel in the city for a period of several hours. Consequently, the representative does not reach the offices of Tighte Fist plc until 8:00 pm. Has a repudiatory breach of contract occurred? Would it have occurred if the representative reached the offices at 5:10 pm? Would the result have been any different if Mountain Magic Ltd had telephoned Tighte Fist plc to inform them of the effect of the bomb scare? Summary It is important to ascertain whether a breach of contract has occurred. To determine this, the nature of the term and the standard of performance required must be ascertained. Further reading ¢¢ Campbell, D. ‘Arcos v Ronaasen as a Relational Contract’, Chapter 7 in Campbell, D., L. Mulcahy and S. Wheeler (eds) Changing concepts of contract : essays in honour of Ian Macneil. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) [ISBN 9781137574305]. page 203 page 204 University of London International Programmes 14.3 What occurs upon breach Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 20 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 20.3 ‘The consequences of breach’ to Section 20.9 ‘Anticipatory breach’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 8 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 2 ‘Consequences of breach’. The consequences of a breach of contract are determined by the severity of the breach and the decision made by the innocent party. A breach of contract does not automatically end a contract – no matter how severe the breach (see Decro-Wall SA v International Practitioners in Marketing (1971). Rather, a breach of a condition or a sufficiently serious intermediate/innominate term gives the innocent party the option to terminate the contract. The terms used to describe this option to terminate vary from an ‘election’ to the ‘right to rescind’. Where the right is described as one of rescission, this has different consequences from a rescission which operates in relation to a vitiating element, such as misrepresentation (considered in Chapter 9). A rescission for breach ends only future obligations, leaving past ones remaining. In contrast, rescission for misrepresentation ends all obligations. Certain other consequences also occur upon a breach of contract. The innocent party, regardless of whether or not he decides to terminate the contract, will have the right to sue for damages. This is dealt with in Chapter 16. In addition, it may also be that the party in breach is unable to sue upon the contract. This will occur if the obligations imposed by the contract are dependent upon each other. Obligations are dependent when one party must be willing and able to perform his obligation in order to maintain a suit against the other party for his breach. It is usually the case in contract that the obligations are dependent. In a contract of employment, for example, the contract could provide that the employee is paid weekly. In the event that the employee does not work that week, he or she will be unable to recover their wages. The innocent party must communicate to the party in breach that he has elected to terminate the contract: Vitol SA v Norelf Ltd (1996). A court has to take into account any steps taken by the party in breach to remedy accrued breaches of contract. If a breach of contract is remedied before the injured party purports to exercise the right to termination, then the fact that the breach had been remedied was an important factor for the court to consider: Ampurius Nu Homes Holdings Ltd v Telford Homes (Creekside) Ltd [2013] EWCA Civ 577. The nature of a breach of contract is prospective. That is to say, if the innocent party elects to terminate the contract, future obligations are no longer binding and are discharged. Past obligations, however, remain. The contract has no future, but it does have a past. Those rights which have been unconditionally acquired are still binding. See, for example, the speech of Lord Porter in Heyman v Darwins Ltd (1942) and the decision in Johnson v Agnew (1980). If an innocent party elects to terminate the contract for breach she is no longer bound to accept or make any performance under the contract. What happens if she does not elect to terminate the contract? In this case, she remains bound to her obligations. In addition, she cannot subsequently decide to ‘return’ to the earlier breach and then purport to accept it while the breach remains anticipatory: Stocznia Gdanska SA v Latvian Shipping Co (1997). (An anticipatory breach, considered below in Section 14.4, is a breach which occurs in time before performance is due.) If a party, on the first of the month, commits an anticipatory breach of a contract to be performed on the 15th of the month, the innocent party can terminate the contract or affirm the contract. If the innocent party chooses to affirm the contract, they cannot then claim on the eighth of the month that there has been an anticipatory breach of the contract and purport to then accept the earlier breach. Where the innocent party elects not to terminate the contract, she is said to have ‘affirmed’ the contract. Where, however, an innocent party affirms a breach of contract which is then met by a continued renunciation of the contract, the innocent party can terminate the contract: White Rosebay Shipping SA v Hong Kong Chain Glory Shipping Ltd, The Fortune Plum [2013] EWHC 1355. Contract law 14 Performance and breach In Geys v Societe Generale (2012) the Supreme Court held that in a contract of employment where there existed a good reason and an opportunity for the innocent party to affirm the contract following a repudiation by the employer, the innocent party should be allowed to do so. In reaching this decision the court considered the difference between the two competing types of contractual repudiation. Summary Not every breach entitles the innocent party to terminate the contract. Where the breach is sufficiently serious to entitle the innocent party to terminate the contract, the contract is not automatically terminated. It is only terminated where the innocent party elects to terminate the contract. The effect of this termination is prospective only. When a decision has been made by the innocent party to terminate the contract for an anticipatory breach, they cannot then purport to revive the contract before the time at which performance had been due. Likewise, if they affirm the contract after an anticipatory breach, they cannot then purport to terminate the contract for that anticipatory breach before the time at which performance is due. Activity 14.2 In what circumstances will a party be held to have ‘affirmed’ a contract? To what extent is a party’s election to terminate or to affirm constrained by considerations such as the reasonableness of his decision or conduct? Activity 14.3 What is the importance to the innocent party of determining the nature of the term breached by the other party? 14.4 Anticipatory breach Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 19 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 19.9 ‘Anticipatory breach’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 8 ‘Breach of contract’ – Section 5 ‘Anticipatory breach’. Anticipatory breach occurs when, before a performance is due, a party either renounces the contract or disables himself from performing it. A renunciation must amount to a clear and absolute refusal to perform. This can be either express or indicated by the conduct of the party involved. The inability to perform must involve the breach of a contractual obligation but does not have to be the fault of the party in breach. Thus in the case of Universal Cargo Carriers Corp v Citati (1957), a charterer was held to be in anticipatory breach of his obligation to provide a cargo at the time specified. The breach occurred because of the failure of a third party to provide him with the cargo. An anticipatory breach gives rise to an immediate right of action. The injured party does not have to wait until the time due for performance to terminate the contract. This means that an anticipatory breach gives rise to a right to terminate if its prospective effects are such as to satisfy the requirement of substantial failure in performance. One of the odd features about an anticipatory breach is not that the breach gives rise to an immediate right of action but that the damages are determined and can be claimed at once, before the time is fixed for performance. This is by reason of the decision in Hochster v De la Tour (1853). Termination How does an injured party know when he or she has the right to terminate for an anticipatory breach? This will depend upon the form of the anticipatory breach. In the case of a renunciation, the renunciation must be such as to prove that the party page 205 page 206 University of London International Programmes in breach has ‘acted in such a way as to lead a reasonable man to conclude that he did not intend to fulfil his part of the contract’. The court examines the nature of the refusal to determine whether the injured party was reasonable in their opinion that the refusal was sufficiently clear and absolute to give them the right to terminate. In the case of a prospective inability (where the party is alleged to have committed a breach by disabling themselves from performance) the question of whether or not the injured party can rescind/terminate the contract will depend upon the seriousness of the consequences of the breach. Affirmation One of the effects of an anticipatory breach of contract is that the innocent party may elect to affirm the contract and continue with a performance that he knows is not wanted by the other party: White and Carter (Councils) Ltd v McGregor (1962). The innocent party’s ability to affirm the contract and continue with performance is qualified in two ways according to Lord Reid in White and Carter (Councils) Ltd. First the innocent party cannot carry on with performance where he needs the co-operation of the party in breach: Hounslow LBC v Twickenham Garden Developments Ltd (1971). Second, Lord Reid, in his speech in White and Carter (Councils) Ltd stated that where the innocent party had no legitimate interest in performing the contract other than claiming damages, he ought not to saddle the other party with an additional burden. The innocent party will be found to have an insufficient legitimate interest in performing the contract when such performance would be ‘wholly unreasonable’ (The Odenfield (1978) and The Alaskan Trader (1984)) or ‘perverse’ (The Aquafaith (2012)). In the Twickenham Garden Developments case Megarry J explained (correctly) that Lord Reid’s two qualifications necessarily formed part of the ratio decidendi of the White v Carter decision. Another effect of an anticipatory breach is that if the innocent party elects to affirm the contract, he runs the risk that the contract may later be discharged by frustration (Avery v Bowden (1855) and generally on frustration see Chapter 15). In this event, he will not be able to claim for the earlier breach. Similarly, if the innocent party affirms the contract and subsequently breaches it himself, again, he will not be able to rely upon the other party’s earlier breach of contract. Summary An anticipatory breach occurs when the contract is breached before the time is set for performance. In such a case, the innocent party may elect to affirm the contract and, if possible, carry on with performance. This will only be possible where the innocent party can perform his outstanding duties without the assistance of the other party and where the innocent party is regarded as having a ‘legitimate interest’ in so doing. Alternatively, the innocent party may elect to terminate the contract. In this case, damages will be assessed at the time of the anticipatory breach, rather than the time at which performance is due. Activity 14.4 In The Hounslow Megarry J said that the two qualifications mentioned by Lord Reid in White and Carter are necessarily part of the ratio decidendi of the White and Carter case. Is this statement correct? Activity 14.5 Could the claimant insist on performing, after the defendant had repudiated the contract, if he knew that all his effort and expenditure would simply be wasted? (Compare Clea Shipping v Bulk Oil (1984)). Activity 14.6 What are the risks involved in not accepting an anticipatory repudiation? Contract law 14 Performance and breach Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 15 ‘Discharge by breach’. Examination advice You are reminded of the general advice given in the first chapter to this guide. In particular, this advice is meant to be of assistance to candidates by examining past examination papers. It is in no way determinative of what the examiners in this subject may do in the future. A review of past examination papers reveals that questions involving performance and breach of contract usually involve issues surrounding the nature of the terms of the contract. They have often involved questions as to the assessment of damages. Sample examination questions Question 1 ‘When a party has a right to terminate a contract for breach is far from clear and should be clarified.’ Discuss. What would you propose to improve the current position? Question 2 Rhonda is a plumber. She contracts with Simon to replace the plumbing in his restaurant for £10,000. The work must be completed by the beginning of December to be ready for Christmas bookings at the restaurant. At the beginning of November, she has not yet begun work. Simon rings her office and discovers she is out on a similar job at Thelma’s restaurant. He realises, correctly, that Rhonda cannot complete both jobs by the beginning of December. He tells Rhonda not to bother with the job. Simon then hires Amanda to replace the plumbing in his restaurant for £15,000. Rhonda, aware that she cannot complete both jobs, has now decided not to continue work on Thelma’s restaurant in order to undertake the work for Simon, which is much more lucrative. Simon’s staff allow Rhonda in to replace the plumbing while Simon is on vacation. They refuse to allow Amanda entry. Rhonda completes the work and claims £10,000 from Simon. Amanda sends Simon a bill for £15,000. Advise Simon. Advice on answering the questions Question 1 Whether a contract has been breached is largely dependent upon the particular terms of the contract in question. The breach occurs when one party, without lawful excuse, does not perform what is required from him under the contract, or performs it defectively. The problem that the innocent party is then faced with is whether or not the breach is such as to justify termination of the agreement. If the breach is not sufficient to justify termination of the contract but the innocent party purports to do so, he may then himself have breached the contract (Decro-Wall International SA v Practitioners in Marketing Ltd (1971)). The question thus calls for a discussion of the classification of contractual terms into conditions, warranties and intermediate or innominate terms (Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd (1962)). The difficulty here is for the innocent party to determine in which of these categories the breached term should be placed. This is particularly true where the term is an innominate term and the party must determine whether the breach has been sufficiently serious. Having established the basic framework of the law in this area and explored what is required, a good answer would consider what could be done to improve this situation. Would legislation clearly defining the right to terminate assist (or would it impose an unnecessary rigidity)? Should courts attempt to give greater effect to the manner in which the parties themselves classify terms? Should parties take greater care in specifying the consequences of breaches of certain terms? In these areas, candidates are expected to provide their own thoughts on the matter. page 207 page 208 University of London International Programmes Question 2 The question involves issues of breach and damages. Only the breach issues will be considered at this point, although in an examination, you would be expected to deal with both sets of issues. With regard to the breach issues, the problem presented is which party is in breach of contract? To answer this, the nature of a breach of contract must be considered. Is Rhonda in breach of contract when she takes on the other job? To answer this, you need to consider whether Rhonda has renounced the job or made it impossible for herself to perform. She clearly has not renounced the job: so has she made it impossible for herself to perform it? In considering the decisions in Universal Cargo Carriers Corporation v Citati and British & Benningtons v NW Cachar Tea (1923) it is not clear that she would lead a reasonable person to conclude that the contract is impossible to perform. Simon makes no further enquiry as to her ability to perform, beyond his initial telephone call. In these circumstances, Simon himself is in breach of contract. Does Rhonda have the right to carry on in performing? Following the decision in White and Carter (Councils) Ltd v McGregor (1962) it would appear that she does. However, she requires access to Simon’s property and in this regard she appears to fall within the exception in Hounslow LBC v Twickenham Garden Developments Ltd (1971). However, Simon’s staff do grant her access to the property – should this be regarded as co-operation on his part? Finally, Simon has clearly breached the contract with Amanda by refusing to allow her to perform her obligations. Quick quiz Question 1 Which of the following statements provides the most appropriate definition of an ‘innominate term’? Choose one answer. a. The major or main obligation in the contract where breach will give the right to refuse further performance. b. A more or less important obligation depending upon the effects of breach. c. A less important obligation where breach will only provide damages as the remedy. d. An obligation which the courts will read into the contract so as to support the intention of the parties. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Which of the following statements provides the most appropriate definition of ‘anticipatory breach’? Choose one answer. a. Where a contract is not performed at the time it was due to be performed. b. Where the performance of a contract is complete but defective. c. Where the breach occurs before the date of performance which was prescribed in the contract. d. Where the contract contains an untruthful statement which is deemed to be a term of that contract. e. Don’t know. Contract law 14 Performance and breach Question 3 Which of the following occurs upon a breach of contract? a. Sometimes the injured party can terminate the contract for breach. b. The injured party can always terminate the contract for breach. c. Either party can sometimes terminate the contract for breach. d. The terms of the contract provide what the parties can do in the case of breach. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Which of the following statements is correct in determining whether or not a term is a condition? a. Only where the parties stipulate that a term of the contract is a condition does breach give rise to the injured party’s right to terminate the contract. b. The requisite statute determines whether a term is a condition or a warranty. c. The intention of the parties is critical and trade custom will determine whether or not the term is classified as a condition or a warranty. d. Where the parties have stipulated that a term of the contract is a condition and have manifested their intention to allow the injured party to terminate for a breach of this term, courts will classify the term as a condition. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Faced with a repudiatory breach of contract, which of the following options is not open to the injured party? Choose one answer. a. She may elect to affirm the contract and hold the other party to performance. b. She may accept the repudiation and terminate the contract. c. She must decide within the time set by the contract whether to affirm the contract or accept the repudiation. d. She may maintain the contract for a period of time while reserving the right to repudiate the contract. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is the meaning of the term ‘entire obligations’? 2. What is the principle of substantial performance? 3. What standard of performance is required in different contracts? 4. What are the consequences attendant upon a repudiatory breach? 5. In what circumstances can an innocent party terminate a contract for breach? 6. What consequences occur when there has been a breach of contract? page 209 page 210 Notes University of London International Programmes Part VII The discharge of a contract 15 Frustration Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 212 15.1 The basis of the doctrine of frustration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 213 15.2 The nature of a ‘frustrating event’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214 15.3 Limitations on the doctrine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217 15.4 The effect of frustration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 218 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 224 page 212 University of London International Programmes Introduction The doctrine of frustration provides one of the ways by which contractual obligations end. In contrast to termination for breach, the discharge of the contract does not occur as a result of the wrongful actions of one of the parties. Nor does discharge for frustration depend upon the agreement or action of the parties. Instead, where a contract is discharged by frustration, this occurs automatically by operation of law. The courts decide when a contract has been frustrated and, if they decide that it has, then all future obligations cease. The consequences of this are dealt with by both common law rules and statute, the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.8 ‘Frustration’ to Section 14.18 ‘Conclusion’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 12 ‘Discharge by frustration: subsequent impossibility’ – Section 1 ‘The frustration doctrine: discharge for subsequent impossibility’ and Section 2 ‘The contractual allocation of risk’. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the discharge of contractual obligations as a result of events occurring after the contract was entered under the doctrine of frustration, to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The role of the doctrine of frustration in the termination of contracts. uu The timing and type of event that will ‘frustrate’ a contract. uu The limits upon the operation of the doctrine of frustration including the concept of ‘self-induced frustration’. uu The consequences of frustration under the common law rules. uu The consequences of frustration under the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. uu The limitations of the 1943 Act. Contract law 15 Frustration 15.1 The basis of the doctrine of frustration Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.9 ‘Frustration, force majeure and hardship’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 12 ‘Discharge by frustration: subsequent impossibility’ – Section 3 ‘The theoretical basis for the doctrine of frustration’. ¢¢ McKendrick, E. ‘Force majeure and frustration – their relationship and a comparative assessment’, in your study pack. If, after entering into a contract, the continued performance of a contract becomes impossible as a result of subsequent events, the question arises as to whether one or the other of the parties or neither of them should be responsible for this failure of performance. A strict ‘freedom of contract’ approach might lead to the answer that a party who has undertaken to perform obligations has also undertaken the risk that performance of them will become impossible. On this view, failure to perform should therefore be treated in the same way whether that failure is due to a deliberate action or arises from impossibility caused by some supervening event after the contract has been formed. In other words, both situations involve a breach of contract and should be treated as such. This approach, of an absolute obligation, was the original approach taken by the common law and can be seen in the decision in Paradine v Jane (1647). This strict approach was relaxed in the 19th century in the case of Taylor v Caldwell (1863). In this case a music hall, hired for a series of concerts, was destroyed by fire before the concerts took place. Blackburn J held that this destruction brought the contract to an end and discharged both parties from any further obligations under it. The justification for this approach was that there was an Figure 15.1 Surrey music hall ‘implied condition’ in the contract that the main subject matter (the music hall) should continue to exist. When the subject matter ceased to exist, the parties were discharged from further performance. The effect of the decision was to allow a contract to be discharged but, at the same time, adherence to freedom of contract was maintained by the use of an implied term. In the 20th century it has generally been recognised that the suggestion that there is an implied term covering the frustrating situation is something of a fiction – see, in particular, the speeches of Lord Reid and Viscount Radcliffe in Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham Urban District Council (1956). The point was made with some humour by Lord Sands in James Scott & Sons v Del Sol (1922). He suggests an example where the daily milk delivery to a house is suspended after the escape of a tiger from a travelling circus. The dairy should not be liable for the suspended delivery but ‘it would hardly seem reasonable to base that exoneration on the ground that “tiger days excepted” must …be written into the milk contract’. The preferred analysis now is that in situations where, after a contract is entered into, there is an unforeseen change in circumstances (not attributable to the fault of either party) such that performance of the contract would become impossible, illegal or something radically different from what the parties originally intended, justice requires that the courts should treat the contract as having come to an end. See also National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina (Northern) Ltd (1981). That the courts will in some circumstances bring a contract to an end on the basis of frustration does not mean that the parties’ original agreement will be ignored. First, it is important that the courts determine exactly what obligations were originally undertaken, in order to decide whether the change in circumstances has made any of them radically different. This issue will be explored further in the next page 213 page 214 University of London International Programmes section. Secondly, it is quite possible for the parties themselves to make provision in the contract for what is to happen should the performance of the agreement become impossible, or radically different, as a result of some subsequent event for which neither of them is to blame. This is common in commercial contracts, which frequently use what are known as ‘force majeure’ clauses. Where there is a clause of this type which covers the situation which has occurred, then the courts will give effect to it. In essence this means the event was foreseen. Activity 15.1 Why do you think that both McKendrick and Poole deal with the doctrine of frustration in chapters which also deal with ‘mistake’? Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 14 ‘Discharge by frustration’. 15.2 The nature of a ‘frustrating event’ Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.11 ‘Impossibility’ to Section 14.14 ‘Express provision’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 12 ‘Discharge by frustration: subsequent impossibility’ – Section 4 ‘Frustrating events’. What type of event will be treated as having frustrated a contract? It is impossible to give a comprehensive list, because it is the effect of the event, rather than the event itself, which is in the end the determining factor. As Lord Radcliffe stated in Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham Urban District Council: frustration occurs whenever the law recognises that without default of either party a contractual obligation has become incapable of being performed because the circumstances in which performance is called for would render it a thing radically different from that which was undertaken by the contract …It was not this that I promised to do. In deciding whether or not a contract has been frustrated, courts apply a ‘multifactorial approach’ (see Edwinton v Tsavliris (The Sea Angel) (2007)). What is important is that there must be a break in identity between what was contemplated and the new performance; courts will not easily conclude that such a break has occurred (see CTI Group Inc v Transclear SA (2008)). Factors which courts should take into account include: the terms of the contract itself, its matrix or context, the parties’ knowledge, expectations, assumptions and contemplations, in particular as to risk, as to the time of contract, at any rate so far as these can be ascribed mutually and objectively, and then the nature of the supervening event, and the parties’ reasonable and objectively ascertainable calculations as to the possibilities of future performance in the new circumstances. [per Rix LJ, The Sea Angel, para 111] With this general principle in mind, we can now usefully look at examples from the cases of situations which have, or have not, led to a decision that a contract is frustrated. From these some general impression of the characteristics of a frustrating event can be gained. In all cases, however, it must be that the event has made the contract impossible, illegal or radically different – it is not enough that the contract has simply become more difficult or expensive for one party. In Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham Urban District Council builders who contracted to erect 78 houses within eight months for £94,000 were not allowed to rely on frustration when construction took 22 months and cost the contractors £115,000. Similarly, in Tsakiroglou & Co v Noblee and Thorl (1962) the closure of the Suez Canal did not frustrate a contract for the carriage of goods from Port Sudan to Hamburg. The contract had not specified the route and the fact that the alternative route, via the Cape of Good Hope, would take much longer was not sufficient to frustrate the contract. Contract law 15 Frustration Courts have consistently indicated that a contract will be frustrated only where there is a complete change between what was undertaken in the contract and the circumstances in which it is called upon to be performed. Thus in CTI Group Inc v Transclear SA (2008) the Court of Appeal concluded that a contract to sell cement was not frustrated where the contract remained legally and physically possible but where third party suppliers would not sell the necessary cement to the sellers with the result that the sellers could not supply the buyers with the cement. In MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company SA v Cottonex Anstalt [2016] EWCA Civ 789 the Court of Appeal recognised that the application of such a test ‘may be arbitrary but it is pragmatic’. Destruction of subject-matter The most obvious example is where the main subject-matter of the contract has been destroyed, as in Taylor v Caldwell (1863). If something central to the performance of the contract no longer exists, then it is not surprising that the courts will find that the parties’ obligations should come to an end. Full destruction may not be necessary. In Asfar v Blundell (1896), the contamination of perishable goods, which rendered them unusable, was held to be equivalent to destruction (see also s.7 Sale of Goods Act 1979). Personal incapacity Another clear case of frustration will be where both parties have agreed that the contract is to be carried out by a particular individual, and that individual dies, or is too ill to perform (see Condor v Barron Knights (1966)). The court will need to be satisfied, however, that the contract was not simply for work to be done, but for it to be done by the particular individual who is unavailable. Activity 15.2 On Monday Nathalie arranges for her car to be serviced at Phil’s garage on the following Friday. Jamie, the mechanic who normally carries out services on Nathalie’s car, is taken ill on Thursday and is unavailable on Friday. Will the contract be frustrated? Activity 15.3 On Monday Nathalie arranges to have her hair styled at Phil’s salon on the following Friday. Jamie, the hairdresser who normally styles Nathalie’s hair, is taken ill on Thursday and is unavailable on Friday. Will the contract be frustrated? Non-occurrence of an event A number of cases concerned with the cancelled coronation of King Edward VII in 1903 illustrate this category. In Krell v Henry (1903) a room overlooking the route of the coronation procession had been hired for the purpose of watching it. When the procession was cancelled, the contract for the hire of the room was held to be frustrated (see also Chandler v Webster (1904)). It has subsequently been implied that the decision in Krell is perhaps as far as the doctrine of frustration should be pushed (North Shore Ventures v Anstead Holdings (2011)). Figure 15.2 The coronation of King Edward VII page 215 page 216 University of London International Programmes Again, however, it is important to be clear as to the precise obligations under the contract in order to decide whether a cancellation has this effect. Thus in Herne Bay Steam Boat Co v Hutton (1904) a boat had been hired to tour the fleet and to watch the King’s review of it, which was part of the coronation celebrations. The King’s illness meant that the review was cancelled. In this case, however, the contract was not frustrated. The tour of the fleet was still possible and this was a significant element in the contract. The hirer remained obliged to pay for the use of the boat. Effects of war In time of war a government may make trading with companies based in enemy territory illegal. Contracts with such companies which were made prior to this action will be frustrated: Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v Fairbairn Lawson Combe Barbour Ltd (1943). Similarly, the requisitioning of property which had been allocated to a contract may lead to the frustration of that contract: see Metropolitan Water Board v Dick Kerr (1918) and FA Tamplin v Anglo-American Petroleum (1916) (although in this case the requisitioning of a ship as a troop ship was held not to have frustrated a charter of it, because the requisitioning was not of sufficient length to defeat the whole purpose of the contract). The frustration need not result from direct government action. In Finelvet AG v Vinava Shipping Co Ltd (1983), the continuing war between Iran and Iraq trapped certain ships in the Gulf for a lengthy period. Contracts relating to the charter of these ships were held to be frustrated. Other government action Government action not related to war can frustrate a contract. In Gamerco SA v ICM/ Fair Warning Agency (1995) a stadium which had been booked for a pop concert was closed for reasons of health and safety. It was held that the contract for the hire of the stadium was frustrated. It is also implicit in Amalgamated Investment and Property Co Ltd v John Walker & Sons Ltd (1976) that the listing of a building as being of architectural and historical interest (thus limiting the possibilities for its development) could frustrate a contract for its sale (though on the facts it did not). Other frustrating events Other types of event which have led to contracts being frustrated include industrial action (The Nema (1981)) and the accidental running aground of a ship (Jackson v Union Marine Insurance Co Ltd (1874)). As indicated above, however, the categories of frustrating event are not closed. It will always be possible to argue that some novel occurrence has frustrated a contract, provided that it has had the required effect on the obligations of either or both parties. Activity 15.4 Aaron has booked tickets to attend an event at Highplace Hall. The event is to include a tour of the grounds and a meal in the hall, followed by a concert featuring the famous pianist, Claudio Quays. Is the contract frustrated if the following take place? a. On the day before the event, Highplace Hall suffers a fire and is badly damaged. The grounds are still open, but the Hall is closed, so that the meal and concert cannot take place, or b. On the day before the event Claudio Quays sprains his wrist and is unable to perform. The concert is cancelled. Self-assessment questions 1. What is a ‘force majeure clause’? 2. In what circumstances may government action frustrate a contract? 3. What is the distinction between ‘frustration’ and ‘mistake’? Contract law 15 Frustration Summary The doctrine of frustration operates to relieve parties of further obligations under a contract. It applies when some event which is not the responsibility of either party has made performance of the contract impossible, or radically different from what was originally agreed. Examples of events which will lead to frustration include destruction of the subject matter, the non-occurrence of an event, outbreak of war and government intervention. The contract will not be frustrated if the performance is simply made more difficult or expensive, or if a significant part of the contract survives the frustrating event. Further reading ¢¢ Morgan, Chapter 5. 15.3 Limitations on the doctrine Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.14 ‘Express provision’ to 14.17 ‘The effects of frustration’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 12 ‘Discharge by frustration: subsequent impossibility’ – Section 2 ‘The contractual allocation of risk’. There are two principal limitations on the doctrine of frustration. The first is where the frustrating event has been foreseen and provided for in the contract; the second is where the alleged frustrating event has been ‘self-induced’ by one of the parties, since, as indicated in the quotation from Lord Radcliffe given in Section 15.2, the problem must arise ‘without the default of either party’. Part of the essence of the doctrine of frustration is the fact that the event which has occurred is a surprise. This justifies the conclusion that the risk of the event occurring has not been allocated by the parties and that the court should therefore intervene. If, therefore, the parties have clearly foreseen the possibility of a frustrating event occurring and have made provision for what is to happen in their contract, there will be no room for the doctrine of frustration. An argument that a contract for the development of property was frustrated when there was a ‘crash’ in property values was unsuccessful as the risk was both foreseen and provided for by a clause that permitted the renegotiation of minimum prices in such circumstances (Gold Corp Properties v BDW Trading Ltd (2010)). Thus, as noted at the beginning of this chapter, in the commercial area ‘force majeure’ and similar clauses may well replace the common law and statutory rules on frustration. The courts have tended to narrowly interpret such clauses. In Jackson v Union Marine Insurance Co Ltd (1874) a charter required a ship to sail ‘with all possible dispatch’ from Liverpool to Newport, there to load a cargo for carriage to San Francisco. The ship ran aground off the coast of Newport, was damaged, and not fully repaired for some seven months. The charterer in the meantime used another ship to carry the cargo, on the basis that the contract had been frustrated. The ship owner, however, sued for breach of contract, on the basis that the charter contained a clause stating ‘damages and accidents of navigation excepted’. The court held that this clause could not have been intended to apply in relation to a delay of the length which had occurred. The contract was frustrated and the clause had no application – see also Metropolitan Water Board v Dick Kerr (1918). Another important element in the doctrine of frustration is that the alleged frustrating event must not be attributable to the fault of either party. If it is, then the likelihood is that the party at fault will be in breach of contract and the doctrine of frustration will have no application. The courts have interpreted the concept of ‘fault’ widely in this context: in fact it may be more accurate to say that wherever the alleged frustrating event is attributable to the actions of one of the parties (whether these involved ‘fault’ or not) then the doctrine of frustration will not apply. In Maritime National Fish v Ocean page 217 page 218 University of London International Programmes Trawlers (1935) the defendants chartered a boat from the plaintiffs, but were then unable to use it as planned because they were not granted sufficient fishing licences to cover all the boats they wished to operate. It was held that their contract with the plaintiffs was not frustrated. It was the defendants’ choice as to which boats they used the licences for. The ‘frustration’ of the contract with the plaintiffs was therefore ‘selfinduced’ and ineffective to relieve the defendants of liability to the plaintiffs under the contract. Activity 15.5 Read the case of J. Lauritzen AS v Wijsmuller BV, The Super Servant Two (1990). Why is this case seen as extending (rather than simply applying) the principle established in Maritime National Fish v Ocean Trawlers? Why do you think the decision has been criticised? At one time it was thought that there was a further limitation on the doctrine of frustration, in that it could not apply to leases of land: see Cricklewood Property and Investment Trust v Leighton’s Investment Trusts Ltd (1945). This limitation was rejected by the House of Lords in National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina (Northern) Ltd (1981), though on the facts the contract under consideration in that case was held not to have been frustrated. Summary If the alleged frustrating event has been foreseen and provided for in the contract (e.g. by a ‘force majeure’ clause) the doctrine of frustration will not apply. Similarly, if the alleged frustration can be said to ‘self-induced’ (i.e. it is the result of a decision taken by one of the parties) the contract will not be treated as frustrated. The party which took the decision will be in breach of contract. Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, paras 19-082 to 19-089. 15.4 The effect of frustration Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 14 ‘Common mistake and frustration’ – Section 14.17 ‘The effects of frustration’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 12 ‘Discharge by frustration: subsequent impossibility’ – Section 5 ‘The effects of frustration’. There are two sets of rules relating to the effects of frustration – one under the common law and the other under the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. In most cases the 1943 Act will apply, but there are some situations where the common law is still applicable. It is easiest to understand the effect of the Act by considering the common law rules first, and then to look at the way in which the Act has amended these. 15.4.1 Common law One common law rule which operates even where the Act is also applicable is that a frustrating event terminates the contract automatically, without any need for action by either party. This is in contrast to the position following a repudiatory breach of contract where the innocent party has the option of continuing with the contract or bringing it to an end (see Chapter 14). It follows that any attempt to affirm the contract following frustration will be ineffective. This was confirmed in Hirji Mulji v Cheong Yeong Steamship Co Ltd (1926) and The Super Servant Two (1990). As to the distribution of losses following frustration, the common law started from the position that all future obligations were discharged, but that obligations incurred prior to the frustrating event survived. Where the loss fell would therefore depend entirely on what the contract said about when payment was to be made, or Contract law 15 Frustration page 219 when work was to be done. Thus in Chandler v Webster (1904), which was one of the ‘coronation’ cases, the full obligation to pay for a room to watch the procession arose before the cancellation (in contrast to Krell v Henry (1903) where only a deposit was payable). The hirer of the room was therefore required to make full payment and the entire loss caused by the frustrating event fell on him. For example: January February Deposit Due Instalment 1 Due Event March Instalment 2 Due The payments in January and February have to be paid but the instalment in March is no longer due under Chandler v Webster. The approach taken in Chandler v Webster was, however, modified in Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v Fairbairn Lawson Combe Barbour Ltd (1943). £1,000 had been paid under a contract for the supply of machinery which was frustrated by the German invasion of Poland in 1939. The House of Lords held that where there has been a ‘total failure of consideration’ (that is, the party paying the money has received nothing at all under the contract), then money paid could be recovered. The purchasers of the machinery were therefore allowed to recover their payment of £1,000. Activity 15.6 Sabina makes a contract with Peter for the redecoration of a house which she owns. The total cost is to be £5,000 and, as provided in the contract, she gives Peter an initial payment of £1,500. The balance is to be paid on the completion of the work. The day before Peter starts work, vandals start a fire which totally destroys Sabina’s house. Peter has spent £500 buying materials for the job. What would be the position as to the distribution of losses on the redecoration contract under the common law rules relating to frustration? Activity 15.7 As in 15.6, but the fire takes place after Peter has done one day’s work. The entire job was expected to take four weeks to complete. Activity 15.8 As in 15.6, but the fire takes place on the day before Peter was due to complete the work. The inflexibility of the common law rules, even following the slight modification provided by the Fibrosa case, led to demand for reform. This occurred in the shape of the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. 15.4.2 The Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943 There are some contracts to which the 1943 Act does not apply (see s.2(5)). These include contracts of insurance, some charters of ships (principally charters for a particular voyage) and contracts for the carriage of goods by sea. The exclusion of the shipping contracts exists because there are special rules under shipping law which deal with the situation. The most important exclusion from the effects of the Act is, however, in relation to contracts for the sale of specific goods. In relation to these contracts the common law rules as to the effects of frustration will apply. The two main provisions in the 1943 Act are s.1(2), which deals with money paid or payable prior to the frustrating event, and s.1(3) which deals with benefits conferred prior to that event. They need to be considered in turn. Section 1(2): money paid or payable prior to frustration Section 1(2) provides that where money was paid or payable prior to the frustrating event, it should be returned (if paid), or should cease to be payable (if not paid but owing). Unlike the common law, this is not dependent on there being a total failure of consideration. Not all the money may be recoverable, however. The section provides that if expenses have been incurred towards the performance of the contract, some of the money paid or payable may be retained or recovered, to the extent that a court page 220 University of London International Programmes considers it just in all the circumstances. The amount concerned cannot exceed the amount of the expenses incurred, nor can it exceed the amount paid or payable under the contract (even if the expenses are greater than this). The discretion given to the court is a broad one, as confirmed by Gamerco SA v ICM/ Fair Warning Agency (1995). The case concerned the frustration of a contract to hold a pop concert because of the closure of the specified stadium on grounds of safety. The plaintiffs sought to recover some $412,500 which had been paid. Although the defendants could point to expenses which they had incurred, the judge concluded that in all the circumstances it was just that the $412,500 should be returned in full. It does not follow, therefore, that simply because a party has incurred expenses that it will automatically be allowed to deduct these from sums returnable under s.1(2). The overall justice of the case must be taken into account. Section 1(3): compensation for a ‘valuable benefit’ Section 1(3) deals with the situation where a party has received a benefit other than money prior to the point at which the contract was frustrated. In that situation the section allows the party to recover from the other party ‘such sum …as the court considers just, having regard to all the circumstances of the case.’ In particular the court should take into account any expenses incurred by the benefited party and ‘the effect, in relation to the said benefit, of the circumstances giving rise to the frustration of the contract’. This final consideration which the court must take into account has been interpreted in a way which has significantly reduced the scope for recovery for the provision of benefits. In BP Exploration Co (Libya) Ltd v Hunt (No 2) (1979), Goff J (as he then was), having held that the purpose of the Act was the prevention of unjust enrichment rather than the apportionment of losses, ruled that the value of any alleged benefit under s.1(3) must be assessed in the light of the frustrating event itself. Where, therefore, the frustrating event has had the effect of destroying the benefit, nothing will be recoverable under s.1(3). This interpretation of the Act has been the subject of much criticism – though this is mainly focused on the poor drafting of the legislation, rather than Goff J’s interpretation of it. Activity 15.9 Sabina contracts with Peter for the redecoration of a house which she owns. The total cost is to be £5,000 and, as provided in the contract, she gives Peter an initial payment of £1,500. The balance is to be paid on the completion of the work. The day before Peter starts work, vandals start a fire which totally destroys Sabina’s house. Peter has spent £500 buying materials for the job. What would be the position as to the distribution of losses on the redecoration contract under the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943? Activity 15.10 As in 15.9, but the fire takes place after Peter has done one day’s work. The entire job was expected to take four weeks to complete. Activity 15.11 As in 15.9, but the fire takes place on the day before Peter was due to complete the work. Self-assessment questions 1. Give an example of ‘self-induced’ frustration of contract. 2. Can the doctrine of frustration be applied to leases of land? 3. What is the ‘object’ of the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943? Contract law 15 Frustration Summary The common law rules discharge parties from future obligations, but otherwise leave any losses to lie where they fall. The only exception is the recovery of money paid where there is total failure of consideration. The Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943 provides more flexible rules under which money may be recovered, or payment ordered for benefits which have been acquired. The object of the Act is the prevention of unjust enrichment; it does not always operate, therefore, to distribute losses between the parties. The Act has been much criticised for its unsatisfactory drafting, particularly in relation to s.1(3). Sample examination question Bernard is the owner of a mansion called Stately Grange, which contains a collection of 50 valuable oil paintings. Bernard contracts with Artistic Cleaners Ltd to have all the paintings cleaned and re-hung, at a cost of £200 per painting. He pays Artistic Cleaners £2,000 in advance, with the balance of £8,000 to be paid when all the pictures have been cleaned and re-hung. There is a stable yard in the grounds of Stately Grange from which Bernard runs pony-trekking holidays. Christine books a week’s holiday for herself and her five children for the week 8–15 August. She pays a deposit of £150 with the balance of £850 to be paid at the start of the holiday. Consider the effect of the following events on these contracts. a. On 6 August Artistic Cleaners Ltd have cleaned and re-hung 40 of the paintings. Of the remaining 10, five have been cleaned but remain at Artistic Cleaners’ workshop. The other five are still at the Grange. That evening Stately Grange is badly damaged by fire and all the paintings in the Grange are destroyed. b. The fire means that Christine’s holiday party will not be able to be accommodated in the Grange, as was planned, but will have to use tents in the grounds. In addition an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease on a neighbouring farm means that riding will be restricted to the Grange’s own grounds, rather than including tours of the very attractive local countryside. On learning of this Christine seeks to cancel the holiday and reclaim her deposit. Advice on answering the question While there is some overlap between the two sections of this problem, the facts and the issues involved are sufficiently separate for you to deal with each independently. a. Has the contract with Artistic Cleaners been frustrated? Clearly it cannot be completed, as five of the pictures concerned have not been cleaned and have now been destroyed. Full performance is therefore impossible and this suggests that the contract is frustrated. On the other hand, you might also wish to consider the possibility that this contract is divisible into a series of separate obligations, since the price seems to have been calculated at a rate per painting (see, for example, the discussion of ‘entire obligations’ and ‘substantial performance’ in Chapter 14). On this basis might it be possible to argue that it is only as regards the final five paintings that the contract is frustrated, so that Bernard is obliged to pay for the work that has already been done? If the contract is frustrated, the 1943 Act will apply. Under s.1(2) Bernard could reclaim the £2,000 he has paid. Artistic Cleaners would wish to set off their expenses, but this will only allow them, at a maximum, to retain the £2,000. If they wish to recover for the work done on the 45 paintings which they have dealt with the claim will have to be based in s.1(3). The difficulty is that Appleby v Myers (1867) and BP Exploration v Hunt (1979) suggest that Bernard has not received any valuable benefit, other than in relation to the five paintings in Artistic Cleaners’ workshop. At the contractual rate of £200 per painting this only entitles Artistic Cleaners to £1,000 as a maximum – that is, less than the £2,000 they have already received. It seems unlikely, therefore, that if the contract is frustrated, Artistic Cleaners will be able to do more than retain the £2,000 – and even this is at the discretion of the court. page 221 page 222 University of London International Programmes b. Again, the first question is to ask whether the contract for the holiday has been frustrated? Clearly it has not been rendered impossible. Christine and her family can still stay at the Grange (albeit camping rather than living in the house itself) and can still spend the week riding ponies. Do the changes and restrictions mean that the holiday is ‘radically different’ from what had been contracted for? This will depend to some extent on what exactly was promised in the contract, and how important a part of that contract the elements which have changed were. In the end, however, it is a matter of judgment, which can be argued either way. If the contract is frustrated, again the 1943 Act will apply. Christine will be entitled under s.1(2) to reclaim the £150 she has paid, subject to the deduction of expenses by Bernard (to the extent considered just by a court). She will not be liable to pay any of the balance. Section 1(3) does not seem to have any role to play in this part of the problem. If the contract has not been frustrated, then Christine’s remedies, if any, will depend on whether Bernard is in breach of contract and the seriousness of the breach. See the discussions of breach in Chapter 14 and damages in Chapter 16. Quick quiz Question 1 How did Lord Simon, in the case of National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina (Northern) Ltd (1981), explain when frustration would discharge the obligations of the parties to a contract? Choose one answer. a. Frustration of a contract takes place when there supervenes an event (without default of either party and for which the contract makes no sufficient provision) which so significantly changes the nature (not merely the expense or onerousness) of the outstanding contractual rights and/or obligations from what the parties could reasonably have contemplated at the time of its execution that it would be unjust to hold them to the literal sense of its stipulations in the new circumstances; in such a case the law declares both parties to be discharged from further performance. b. In contracts in which performance depends on the continued existence of a given person or thing, a condition is implied that the impossibility of performance arising from the perishing of the person or thing shall excuse the performance. In none of the cases is the promise in words other than positive, nor is there any express stipulation that the destruction of the person or thing shall excuse the performance; but that excuse is by law implied, because from the nature of the contract it is apparent that the parties contracted on the basis of the continued existence of the particular person or chattel. c. It is not hardship or inconvenience or material loss itself which calls the principle of frustration into play. There must be as well such a change in the significance of the obligation that the thing undertaken would, if performed, be a different thing from that contracted for. d. You must look at the actual circumstances of the case in order to see whether one party to the contract is relieved from its future performance by the conduct of the other; you must examine what the conduct is so as to see whether it amounts to a renunciation, to absolute refusal to perform the contract. e. Don’t know. Question 2 Rix LJ, in Edwinton Commercial Corporation, Global Tradeways Ltd v Tsavliris Russ (Worldwide Salvage & Towage) Ltd (The ‘Sea Angel’) (2007) considered the modern statements of the doctrine of frustration to be found in the words of Lord Simon Contract law 15 Frustration in National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina (Northern) Ltd (1981) and Lord Radcliffe in Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham UDC (1956) and made certain observations as to how a court could consider whether or not a frustrating event has occurred. Which of the following is not an element in Rix LJ’s considerations in The Sea Angel? Choose one answer. a. The concept of justice plays a strong role in the determination of whether or not a contract has been discharged through frustration. b. A particular factor, if sufficiently important, in the factual pattern of the contract can assume such dominance that it can exclude the doctrine of frustration. c. In particular cases of frustration, one can ascertain one, or perhaps more, factors which have driven the result in the particular case. d. The correct approach to determining whether or not a frustrating event has occurred is a multi-factorial approach considering a range of different factors in the context of the particular contract. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following events will NOT result in the doctrine of frustration operating? Choose one answer. a. A pop group are on a year’s tour of the US and one month into the tour the lead singer falls ill. The lead singer is told he can only work a couple of days a week since his illness. The lead singer is prepared to keep on singing seven days a week. The band decide to replace the lead singer. b. A member of the Royal Family decides to get married and so a devoted fan hires a hotel room with a very good view of the procession route. The member of the Royal Family falls ill three days before the wedding is due to take place and the wedding is postponed. c. A businessman contracts with a foreign businessman to supply monthly quantities of oranges for three years. After four months war breaks out between the two countries and the supplying of oranges to the country of the foreign businessman becomes illegal. d. A pending bride places an order with a dressmaker for a wedding dress. Two days before the wedding is due to take place the bride decides she has fallen in love with the best man and calls the wedding off. She decides she no longer wants the dress, which was delivered just as she was calling off the wedding. e. Don’t know. Question 4 This question requires you to apply the law to a particular fact situation in order to determine the likely outcome of the case. Read the facts given below and then decide which statement most accurately summarises how a judge should decide the case. Arabella arrives in London on Monday and wants to rent a flat from Boris. Arabella runs her own escort company where she provides company for gentleman callers of a certain age. Boris suspects that Arabella is actually a prostitute but he is not sure and so agrees. He says that one of the conditions of renting the flat is that she works as his escort girl and only his escort girl. Arabella agrees and she places a £250 deposit with him and says she will pay the first month’s rent of £1,000 when she moves in. She says she will be back on Friday with her belongings to move in. On Wednesday Arabella is mugged by two young men and she loses all her money. They also seriously injure her so that she has to go into hospital. She is left with permanent page 223 page 224 University of London International Programmes disabilities such that she will never work again. Hearing this news Boris is furious because on Tuesday he turned down an offer from Clara to rent the flat for £3,000 per month as she loved the location. Boris wants to recover the money he has now lost for the first month’s rent. Arabella says she cannot now afford to take the flat and is unable, due to the mugging, to be released from hospital. Choose one answer. a. The contract for the lease has been breached by Arabella and she should now pay £2,750 in addition to losing the £250 deposit. b. The contract is illegal because Arabella is a prostitute and so is void and Boris cannot enforce it. c. The contract to provide exclusive sexual services is enforceable despite its attempts to restrain trade. d. The contract for the lease is frustrated and Arabella should be able to recover the moneys already paid minus any expenses claimed by Boris. e. Don’t know. Question 5 With the decision of the court in BP Exploration Co (Libya) Ltd v Hunt (No 2) (1979) the role of the court under s.1(3) is which of the following? Choose one answer. a. To assess whether or not the contract is governed by English law. b. To assess whether or not the contract has become impossible of performance. c. To value the benefit which the defendant has obtained at the expense of the claimant and to award damages to the claimant for that benefit. d. To value the benefit which the defendant has obtained at the expense of the claimant and to exercise its discretion in deciding which proportion of that benefit is recoverable by the claimant. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is the role of the doctrine of frustration in the termination of contracts? 2. What types of event will be regarded as frustrating a contract? 3. What are the limitations on the doctrine of frustration 4. What is meant by ‘self-induced frustration’? 5. What are the consequences of frustration under the common law rules? 6. What are the consequences of frustration under the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943? 7. What are the limitations of the 1943 Act? Part VIII Remedies for breach of contract 16 Damages Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 226 16.1 The purpose of an award of damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227 16.2 Two measures of damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.3 When is restitution available? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 230 16.4 Non-pecuniary loss . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231 16.5 Remoteness of damage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232 16.6 Mitigation of damage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235 16.7 Liquidated damages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227 236 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243 page 226 University of London International Programmes Introduction In Chapter 14 of the module guide, we examined the issue of what constitutes a breach of contract. In general terms, every breach of contract entitles the injured party to claim damages for the loss caused by the breach. The purpose of an award of damages is simple: to put the injured party in the position, as far as money can, they would have been in but for the breach of contract. The difficulty lies in how to measure this loss. The law has traditionally used two measures; one protects expectation interests and the other protects reliance interests (for definitions see Section 16.2 below). Usually, but not invariably, the expectation interest is sought. In some cases, however, the injured party seeks an award based upon a reliance measure. More recently, a restitutionary measure has been used and this differs from an expectation or reliance measure in two ways. First, a restitutionary measure is calculated with reference to the defendant’s gain rather than the claimant’s loss. Second, the circumstances in which a claimant can protect his restitutionary interests are more narrowly prescribed. Regardless of which measure is employed, not all losses will be recoverable. Two devices limit an award of damage. The first device is remoteness. There can be no recovery of losses which are too remote: that is to say, losses which are not foreseeable. This device presents two problems. Not only have different courts appeared to propose different tests concerned with remoteness (a problem of law), but it is also difficult in some cases to determine what is a foreseeable loss (a problem of fact). The second device used to limit the recoverability of loss is mitigation. It is said that a party cannot recover damages for a loss that he could have reasonably avoided. Finally, in addition to the limiting devices of remoteness and mitigation, it is generally said that a party cannot recover damages for non-financial loss (such as injured feelings or distress arising as a result of the breach of contract). The parties to a contract can attempt to avoid the difficulties presented in an assessment of damages by stipulating the amount of damages payable upon a breach of contract. This chapter concludes with an examination of the extent to which courts will enforce these ‘liquidated damages’ clauses. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the remedy of an award of damages for breach of contract, to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The compensatory aim of a basic award of damages for breach of contract. uu The difference between damages awarded on an expectation, reliance and restitution basis including the distinctive and exceptional award of an account of profits made by the party in breach. uu The sub rules applicable to the assessment of damages based upon the three measures above. uu The circumstances when damages may be awarded for non-pecuniary losses. uu The different limitations upon an assessment of damages especially the circumstances in which damages are too remote to be recovered. Contract law 16 Damages 16.1 The purpose of an award of damages Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 21 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 21.1 ‘Introduction’ and Section 21.2 ‘Compensation and the different “interests”’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 9 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 1 ‘The aim of contractual damages’. ¢¢ McKendrick, E. ‘Breach of contract and the meaning of loss’, in your study pack. It is said that contract law is separated from other forms of private obligations such as tort and restitution because contract law seeks to fulfil the expectations created by a binding promise. To this end, the purpose of an award of damages is to compensate the injured party and not to punish the party in breach: see Robinson v Harman (1848). Punitive damages are not available in English law for a breach of contract, even where the defendant deliberately breached the contract. The overriding compensatory aim of damages for actual, as well as for anticipatory, breach of contract (for the distinction see 14.2 and 14.4) was reaffirmed recently by the Supreme Court in Bunge SA v Nidera [2015] UKSC 43. However, it does seem that with the advent of restitutionary damages for breach this principle has been weakened. While the purpose of the award of damages is to compensate the claimant, the difficulty of assessing damages will not prevent their recovery. Damages are normally assessed at the time of breach (Johnson v Agnew (1980)), although this is not an inflexible rule. It was held in Golden Strait Corporation v Nippon Ysen Kubishika Kaisha, The Golden Victory (2007) that in exceptional cases damages would be reduced where it was proven that, between the date of breach and the time of trial, certain events occurred which would have inevitably reduced the damages the claimant could have recovered in respect of its loss. The date of breach is the right date to assess damages where there is an immediately available market for the sale of the relevant asset or for the purchase of an equivalent asset (Hooper v Oates [2013] EWCA Civ 91). Summary The purpose of an award of damages is to compensate the injured party. Further reading ¢¢ McKendrick, E. ‘The common law at work: The saga of Alfred McAlpine Construction Ltd v Panatown Ltd’ (2003) 3 Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal 145. This article is available in HeinOnline through the Online Library. ¢¢ Halson, Chapter 17 ‘Damages for breach of contract’, Section ‘The general compensatory aim’. 16.2 Two measures of damages Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 20 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 20.3 ‘The expectation interest’ and Section 20.7 ‘Reliance interest’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 9 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 2 ‘Expectation loss’ and Section 3 ‘Wasted expenditure’. The question to be answered here is how is the claimant’s loss to be measured? There are two possible bases for assessing damages – the expectation loss and the reliance loss. However, a third approach has been used for breach of contract: the restitution loss. We will consider the first two possible measures here; the third will be examined in Section 16.3. page 227 page 228 University of London International Programmes Expectation loss Expectation loss is the basic measure of contractual damages, sometimes called ‘the contractual measure of damages’ (emphasis added, Lord Nicholls in Nykredit plc v Edward Erdman (1997)). This loss is summarised in Robinson v Harman (1848) 1 Ex 850 as: the rule of the common law is, that where a party sustains loss by reason of a breach of contract, he is, so far as money can do it, to be placed in the same situation, with respect to damages, as if the contract had been performed. (per Parke B at 855) A contract creates an expectation of performance in the promisee. When a defective performance is tendered the promisee may claim damages to be assessed by reference to those disappointed expectations. An award based on the claimant’s expectation interest is compensation for the loss of a bargain. The claimant may thereby obtain the profits he would have received had the contract been performed – damages are assessed in reference to the claimant’s expectation or performance loss. If A contracts to buy a painting from B for £100 and A plans to resell the painting for £200, on the expectation measure of damages, A has lost £100 as this is his profit upon the re-sale. Had he already paid the £100 purchase price, he has lost £200. What is important in these situations is that the law compensates A for the benefit he would have obtained by reason of his contract with B. One issue in deciding expectation is whether the expectation should give you the ‘cost of cure’ or the difference in value. In situations where the defendant does not perform the contract, or performs it badly, the claimant is generally entitled to the cost of cure. This is the amount required to pay a third party to perform what was stipulated in the contract. See, for example, Watts v Morrow (1991). In some instances, however, the courts will not award the cost of the cure where this is wholly disproportionate to any benefit which would be received (where there is little difference in value between the value of the thing contracted for and the thing received). In this situation the courts may award the difference in value. For example, if I buy a blue car from you but you deliver a red car. The cost of cure would be £x amount but the difference in value would be minimal. Very often there is no difference between the two amounts. However, in Ruxley Electronics v Forsyth (1995) the cost of cure far exceeded the original contract price. Mr Forsyth had contracted for a recreational swimming pool of a certain depth. The pool was built to the wrong depth and Mr Forsyth sued for breach of the express term. The cost of cure would have required the original pool to be taken out, re-dug and replaced correctly. This cost far exceeded the original cost of the pool. The difference in value, the court decided, was nil. In trying to ensure that damages are truly compensatory the courts had to ensure that Mr Forsyth was not over-compensated (i.e. that Mr Forsyth had a swimming pool and extensive damages). The outcome may have been different if Mr Forsyth had required the pool to be at a certain depth for reasons other than merely recreational use. Faced with this situation the courts awarded neither cost of cure nor difference in value but awarded damages based on loss of amenity (see Section 16.4; see also Arroyo v Equion Energia Ltd (formerly BP Exploration (Columbia) Ltd) (2013)) for a further suggestion, albeit obiter, that damages for loss of amenity might be awarded when the refusal of cost of cure or reinstatement damages would undercompensate the claimant). Loss of a chance can also form the basis of a claim for loss of expectation. This is unusual but see Chaplin v Hicks (1911) where the plaintiff received damages for the loss of a chance to compete in a competition. Such damages are meant to compensate for the lost opportunity and so, given that there was no certainty that the plaintiff would if she entered have won, the amount recovered will be less than the ‘prize’ for winning. The calculation of such damages will often be very speculative as in Giedo van der Garde Bv v Force India Formula One Team (2010) where damages of $100,000 were awarded. This sum was the court’s best estimate of the lost opportunity of a Contract law 16 Damages Formula One racing driver who was not given at least 6,000 kilometres of test laps. The claimant will not, however, receive substantial damages where the breach of contract has left him no worse off. See C & P Haulage v Middleton (1983) and Sunrock Airline Corp Ltd v Scandinavian Airlines System (2007). Reliance loss In some instances, it will not be appropriate to measure the claimant’s loss on the basis of his expectations. It may be the case, for example, that the claimant is unable to prove the value of his expectations (Anglia Television v Reed (1972)). He cannot establish to what extent he would have been better off had the contract been performed. An alternative basis on which to assess damages is the reliance loss or the loss of expenditure. This basis is usually used when the claimant is unable to prove that a financial benefit would accrue to it had the contract been performed. In Anglia Television v Reed (1972) the plaintiff was unable to establish what profit his television show would have made and consequently claimed for the expenditures he had incurred. On this basis reliance loss damages included: when a contract to install new machinery was breached, the cost of outsourcing work (Bridge UK.com Ltd v Abbey Pynford plc (2007)) and for breach of a franchise contract to sell branded goods, wasted marketing and promotional costs (Yam Seng Pte Ltd v International Trade Corp Ltd (2013)). The claimant is the party who decides whether to seek his reliance losses or his expectation losses: CCC Films v Impact Films (1984). The claimant cannot, however, seek to recover his reliance losses where this would have the effect of allowing him to escape the consequences of a bad bargain: C & P Haulage Co Ltd v Middleton (1983) and Omak Maritime Ltd v Mamola Challenger Shipping (2010). Activity 16.1 The government of the (fictitious) country of Culloden offers for sale the rights to hunt and shoot three bighorn mountain sheep. These very rare sheep are highly prized by big game hunters, who consider the heads of the sheep to be attractive trophies. Damian accepts Culloden’s offer and pays £1 million for the hunting rights. He spends £100,000 outfitting a group for the hunt. After several months of searching, it transpires that the bighorn mountain sheep are extinct, a matter long suspected by some within the Culloden Ministry for the Environment. Advise Damian. Activity 16.2 Emma contracts with Fun Toys Co to purchase 10,000 toys from them. Emma intends to resell the toys in her chain of toy shops. The selection of the toys is to be made within one year by Emma and is to be from Fun Toys’ range of 300 different toys. These toys range in wholesale price from £1.99 to £200. Emma never selects any toys and refuses to do so. Advise Fun Toys Co. Activity 16.3 Why does McKendrick write that ‘In awarding loss of amenity damages it can be argued that the House of Lords (in Ruxley Electronics and Construction v Forsyth (1995)) took one step forwards and one step backwards’? (McKendrick, Section 21.3). Summary The two basic measures by which damages for breach of contract are assessed are the expectation measure and the reliance measure. The expectation measure aims to compensate the claimant for the loss that arises between the difference between no performance and performance – or, in other words, for the profit that the contract would have created for the claimant. Where appropriate this may involve choosing between an award of damages based upon the cost of cure or diminution in value. In other cases damages may be awarded for the loss of chance. The reliance measure compensates the claimant for the wasted expenditures he has incurred. page 229 page 230 University of London International Programmes Further reading ¢¢ Coote, B. ‘Contract damages, Ruxley, and the performance interest’ (1997) 56 CLJ 537. This article is available in HeinOnline through the Online Library. ¢¢ Halson, Chapter 17 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ Sections: ‘The expectation measure: non-pecuniary loss’ and ‘The reliance measure: pecuniary loss’. 16.3 When is restitution available? Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 1 ‘Introduction’ – Section 1.4 ‘Contract, tort and restitution’. ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 15 ‘Illegality’ – Section 15.18 ‘The recovery of money or property’. ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 21 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 21.4 ‘The restitution interest’, Section 21.5 ‘Failure of consideration’ and Section 21.6 ‘Enrichment by wrongdoing’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 10 ‘Remedies providing for specific relief and restitutionary remedies’ Section 3 ‘Restitutionary remedies’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 16 ‘Illegality’ – Section 3 ‘Money or property transferred under an illegal contract’. The circumstances in which a claimant can recover on a restitutionary basis for a breach of contract are strictly limited. Recovery on a restitutionary basis will only occur when the claimant can establish that the defendant was enriched at the claimant’s expense and that it is unjust to allow the defendant to retain his profit without compensating the claimant. A restitutionary reward requires the defendant to disgorge the profit obtained as a result of his wrongdoing. When a contract is terminated because of the defendant’s breach, the claimant may elect to proceed in contract or restitution (Planche v Coburn (1831)). However, the circumstances in which a party can so proceed in a contract case are very limited. 16.3.1 Total failure of consideration In the first set of circumstances, the claimant may seek a restitutionary remedy where there has been a total failure of consideration. The decision in Whincup v Hughes (1871) stands for the proposition that the claimant may seek a restitutionary remedy by saying that the basis upon which he conferred a benefit has failed entirely because of the defendant’s breach of contract. However, to succeed in this, the claimant needs to establish a total failure of consideration. If any part of the contract is performed, or if the claimant has received any part of the consideration, the restitutionary claim is barred. Into this set of circumstances fall many of the illegality cases discussed in Chapter 12. See, in particular, Bowmakers v Barnet Instruments (1945) and Tinsley v Milligan (1993). Note the possibility of the defence of change of position: Lipkin Gorman v Karpnale (1992). 16.3.2 Unjust benefit The second set of circumstances occurs where the claimant seeks a restitutionary remedy on the ground that the defendant has obtained an unjust benefit, or profit, because of his breach of contract. While it had been held that gains-based damages are not generally available for a breach of contract (Surrey County Council v Bredero Homes Ltd (1993)), the House of Lords has now held that the court would order an account of profits where neither equitable remedies (see Chapter 17) nor an award of damages based upon a financially assessed measure of damages would not provide a sufficient remedy (Attorney-General v Blake (2000)). In Blake a former spy for the British intelligence services defected to Russia and published his autobiography which, in breach of a lifelong contractual obligation of confidentiality, revealed many secret matters. An account of profits was ordered which required the wrongdoer Contract law 16 Damages to disgorge the benefit he obtained by the breach of contract. The House of Lords in Blake recognised Wrotham Park Estate Co Ltd v Parkside Homes Ltd (1974) as a rare example where restitutionary damages for breach of contract had been awarded in the past. When land was developed for housing in breach of a restrictive covenant in the sale agreement the developer was ordered to pay 5 per cent of the profit to the estate which had the benefit of the covenant despite the fact that the development did not affect the value of the estate at all. The fractional account of profits ordered in Wrotham Park was the amount which a reasonable person might have asked for the waiver of the covenant. On the exceptional facts of Blake the court’s order was that the defendant had to account for all the profits he made from the publication of his book. In Blake it was emphasised many times that an account of profits would be awarded only in exceptional circumstances; unfortunately, the House of Lords declined to provide more explicit directions as to when this would occur. Later courts have been hesitant to award an account of profits and it may be that Attorney-General v Blake will be confined to its own very unusual facts. In Experience Hendrix LLC v PPX Enterprises Inc (2003) the Court of Appeal ordered a fractional account of profits when recordings of Jimi Hendrix were exploited in breach of a prior contract. In Devenish Nutrition Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis SA (2008) the Court of Appeal held that the remedy was only available where other contractual remedies are inadequate. Recent cases show a reluctance to make an award on the authority of Blake preferring to award compensatory damages for loss of a bargaining position following Wrotham Park (Experience Hendrix LLC v PPX Enterprises Inc (2003); WWF World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund) v World Wrestling Federation Entertainment Ltd (2006 reversed on other grounds in 2007) and One Step (Support) Ltd v Morris-Garner (2014) or to note that the breach of contract though ‘deliberate’ was simply ‘too unremarkable’ to justify an account of profits (One Step (Support) Ltd v Morris-Garner (2014)). Activity 16.4 Write a summary of the House of Lords’ decision in Attorney-General v Blake (2000). No feedback provided. Summary In limited circumstances, a claimant may recover damages assessed on the unjust benefit the defendant obtained by his breach of contract rather than damages assessed on the claimant’s loss. This is a developing area of law with considerable uncertainty at present. Further reading ¢¢ Hedley, S. ‘“Very much the wrong people”: The House of Lords and publication of spy memoirs (AG v Blake)’ (2004) The Web Journal of Current Legal Issues 4 – available at www.bailii.org/uk/other/journals/WebJCLI/2000/issue4/hedley4.html ¢¢ Campbell, I.D. and D. Harris ‘In defence of breach: a critique of restitution and the performance interest’ (2002) 22 Legal Studies 208. 16.4 Non-pecuniary loss Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 21 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 21.13 ‘Damages for pain and suffering and the “consumer surplus’’’ and Section 21.14 ‘Conclusion’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 9 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 8 ‘Non-pecuniary loss’. We are concerned here with non-financial losses, that is to say, loss caused by anxiety, mental distress and hurt feelings. This is an area where the position of the law is changing, although the extent of the change is as yet difficult to ascertain. The page 231 page 232 University of London International Programmes starting point is the House of Lords’ decision in Addis v Gramophone Co Ltd (1909). In this case, the plaintiff was not allowed to recover damages to cover the indignity he suffered because of the manner in which he was dismissed by the defendants. The House of Lords held that injured feelings were not compensable for a breach of contract. Recently the courts have adopted a more relaxed approach to the recovery of damages for non-pecuniary loss by creating numerous exceptions to Addis, causing Lord Cooke to remark that he would now ‘doubt the permanence of Addis in English Law’ (Johnson v Gore-Wood (2002)). The modern case law supports the recovery of damages in the following circumstances. uu Where the provision of a non-pecuniary gain, such as pleasure, is an important, but not necessarily the only, object of the contract (e.g. a contract for the provision of a holiday: Jarvis v Swan Tours (1973) QB 233). uu Where the avoidance of non-pecuniary loss, such as mental distress, is an important, but not necessarily the only, object of the contract (e.g. a contract with a house surveyor: Farley v Skinner (2001); or a lawyer acting in a family law dispute: Hamilton Jones v David & Snape (A Firm) (2003)). uu Where the claimant suffers ‘physical inconvenience’ (e.g. when train passengers had to walk four miles to their destination: Hobbs v London and South Western Rly Co (1875); or a couple’s clothes and cabin on a cruise liner were damaged in a storm: Milner v Carnival plc (2010)). uu Where the distress or discomfort suffered was directly consequential on physical discomfort (e.g. for distress and inconvenience caused while property repairs were effected following a negligent pre-purchase survey: Watts v Morrow (1991)). uu For loss of ‘amenity’ (e.g. Ruxley Electronics v Forsyth (1995) above where the trial judge’s award of £2,500 for ‘loss of amenity’ was not challenged). Activity 16.5 What is the purpose behind preventing a recovery of damages for mental distress where there is a breach of an ‘ordinary’ contract? Activity 16.6 How can Farley v Skinner (2001) be reconciled with Watts v Morrow (1991)? Summary Traditionally, the law prevented recovery of damages for hurt feelings, or for mental distress. In recent years, however, the law has relaxed this restriction to a considerable extent. The result is to allow recovery for a wider range of damages. Further reading ¢¢ Halson, R. ‘The recovery of damages for non-pecuniary loss in the UK: a critique and proposal for a new structure integrating recovery in contract and tort’ (2015) Chinese Journal of Comparative Law 245. 16.5 Remoteness of damage Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 21 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 21.11 ‘Remoteness’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 9 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 6 ‘Remoteness of damage’. Even if the claimant establishes that his loss was caused by the defendant’s breach, damages cannot be recovered for this loss where the loss is held to be too remote. Contract law 16 Damages page 233 The Court of Exchequer established the basic rule in Hadley v Baxendale (1854). In this case the owners of a mill took their broken shaft to a delivery company to send it to engineers in Greenwich. The carriers delayed the delivery and the owners were not able to use the mill during this time. The owners sought damages based on their loss of business during this time. The court held that the owners could not recover damages for the loss of business during the period of the delay because this was not damage which was reasonably foreseeable by the carriers – it would not be within the normal contemplation of the carriers that the owners would be unable to operate the mill without that particular shaft. In a now famous passage, Alderson B stated: Where two parties have made a contract which one of them has broken, the damages which the other party ought to receive in respect of such a contract should be such as may fairly and reasonably be considered as [1] either arising naturally, that is according to the usual course of things, from such breach itself, or [2] such as may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties, at the time they made the contract, as the probable result of the breach of it. Figure 16.1 Hadley Mill as an operational mill 16.2 Hadley Mill in its present form 16.3 The commemorative plaque It is sometimes said that there are two limbs to the test of remoteness in Hadley v Baxendale. The first limb, that is to say the first way in which damages will be foreseeable, is those damages which may reasonably be considered as arising naturally – those damages which arise in the ‘usual course of things’ as a probable result of the breach of contract. In South Australia Asset Management Co v York Montague Ltd [1997] AC 191 at 211 the House of Lords held that what will determine which damages arise in the usual course of things, as a probable result of breach, will depend on the degree of knowledge the parties are presumed to possess and the scope of the contractual duty. The second limb deals with the situation where there are exceptional circumstances. That is to say, if the contract is breached, then the consequences of the breach will be particularly severe because, for example, an especially lucrative opportunity will be lost. In this case, the damages will only be recoverable (that is to say, they will not be too remote) if the special circumstances are reasonably within the contemplation of the parties at the time they made the contract as likely to occur if the contract is breached. The most likely way this test will be satisfied is if the circumstances were actually communicated by one party to the other. These two limbs are not mutually exclusive (Jackson v Royal Bank of Scotland (2005)). No damages were recovered in Hadley v Baxendale. The court found that reasonable people in the position of the carriers would not think that while they had possession of the shaft the mill was idle. Rather they might reasonably expect that the mill owners might have had a spare shaft. On this basis the lost profits claimed for were not recoverable within the first limb of Hadley. Nor were they recoverable under the second limb because there was no evidence that the mill owner had actually communicated the fact that the mill was idle (a contrary suggestion in the headnote which is not repeated in the judgments in Hadley must be wrong): in the great multitude of cases of millers sending off broken shafts to third persons by a carrier under ordinary circumstances, such consequences would not, in all probability have occurred; and these special circumstances were here never communicated by the plaintiffs to the defendants. (per Alderson B at 356) page 234 University of London International Programmes While this is an apparently simple exposition of remoteness, you will see that courts have struggled to define what is within the ‘reasonable contemplation’ of the parties. See, for example: Victoria Laundry (Windsor) v Newman Industries (1949), The Heron II (1969) and H Parsons (Livestock) v Uttley Ingham (1978) (discussed in the feedback to Activity 16.8). In the Victoria Laundries case the defendant engineers failed to deliver and fit a boiler as they had contracted with a laundry to do. The laundry consequently lost income from two sources: they lost some of their normal laundering business and they also were not able to obtain some particularly lucrative dying contracts from the Ministry of Supply. It was held that the first item of loss was recoverable under the first limb of Hadley but that the second was not recoverable under either limb. In The Heron II the House of Lords addressed the difficult question of the probability of occurrence which must be foreseen. There were several formulations discussed but the greatest consensus was that for any item of loss to be recoverable as damages for breach of contract it must have been within the reasonable foresight or contemplation of the parties as a ‘not unlikely’ consequence of breach. This may not appear a generous test for recovery (and is less generous than the test applied in the tort of negligence which may permit recovery of losses which were foreseeable only as a remote consequence) but as Lord Reid explained, in contractual relations, the parties are not strangers (as is often the case with the relationship between a tortfeasor and their victim). Therefore if the promisee wants to expand the liability for breach of contract of the promisor beyond that imposed by the default rule stated in the first limb of the Hadley test the promisee may simply, at or before the time of contracting, inform the promisor of any unusual losses he, the promisee, will suffer in the event of the promisor’s breach. This communication will bring the loss within the second limb of Hadley. The reasoning of Lord Reid in The Heron II was applied by the Court of Appeal in Wellesley Partners LLP v Withers LLP [2015] EWCA Civ 1146 to hold that, where there exists concurrent negligence-based liability in contract and tort, the (less generous to recovery) contractual test will also apply to the claim in tort. This is justified because in the situation of concurrent liability, although there exists a claim in tort, it is not one between strangers. A significant problem in the application of the two-limbed test in Hadley v Baxendale is the determination of when a particular loss is within the reasonable contemplation of the parties. The uncertainty which surrounds the resolution of this problem has, in some respects, been increased by the decision of the House of Lords in Transfield Shipping Inc v Mercator Shipping Inc (The Achilleas) (2008). The House of Lords considered the two limbs of the test of remoteness and Lord Hoffmann considered that the essential question to answer was whether or not the contract breaker ought fairly to have assumed responsibility for the type of loss in question. This consideration seems to add a new test to the determination of remoteness. The matter is uncertain, however, because their Lordships gave separate concurring judgments with the result that it is difficult to extract a ratio from the case. This apparent conflict between the approaches of Hadley and The Achilleas may be resolved by a composite position where the traditional Hadley approach will apply generally but the new Achilleas approach will be used in novel or difficult cases (Supershield Ltd v Siemens Building Technologies FE Ltd (2010)). Activity 16.7 What is the policy behind the rules of remoteness? What is the link, if any, between these rules and the cost of insurance? Activity 16.8 In H Parsons (Livestock) v Uttley Ingham, was it at all probable that the pigs would die? Why should it be enough that it might be foreseen that they would become ill? How can this decision be reconciled with the distinction drawn elsewhere between ‘ordinary’ and ‘special’ business profits? Contract law 16 Damages Activity 16.9 Under the second rule in Hadley v Baxendale, is the defendant’s knowledge of the special circumstances enough to make him liable or is something more required. If so, what? Summary A claimant cannot necessarily recover all the losses flowing from a breach of contract. Those losses which are said to be too remote cannot be recovered. Those losses which ‘arise in the usual course of things’ will be recovered, but where there are special and exceptional losses, these can only be recovered when the claimant has drawn the defendant’s attention to the possibility of these losses at the time of contracting. Further reading ¢¢ Burrows, A. ‘Lord Hoffmann and remoteness in contract’ in Davies and Pila (eds) The jurisprudence of Lord Hoffmann (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2015) first edition [ISBN 9781849465915] p.251. ¢¢ Halson, Chapter 17 ‘Damages for breach of contract’, Sections ’Remoteness’, ‘Recovery for ordinary losses’ and ‘Recovery for unusual losses’. ¢¢ Wee, P.C.K. ‘Contractual Intention and Remoteness’ (2010) Lloyd’s Maritime and Commercial Law Quarterly 150. 16.6 Mitigation of damage Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 20 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 20.10 ‘Mitigation’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 9 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 7 ‘Mitigation’. Causation and remoteness are two factors which seek to limit the possible damages which can be awarded to a claimant. There is another factor which can act to limit the damages of a claimant – the so-called ‘duty to mitigate’. Claimants are said to be under a duty to mitigate their losses. There are two elements to this duty: first, to avoid increasing loss; and, secondly, to act reasonably to reduce it. The basic duty is stated by Viscount Haldane in British Westinghouse Electric Co Ltd v Underground Electric Railways Company of London Ltd (1912). The fundamental basis is thus compensation for pecuniary loss naturally flowing from the breach; but this first principle is qualified by a second, which imposes on a plaintiff the duty of taking all reasonable steps to mitigate the loss consequent on the breach, and debars him from claiming any part of the damage which is due to his neglect to take such steps. Sometimes, the duty to mitigate will require the injured party to re-contract with the party in breach on slightly different terms. See, for example, Payzu v Saunders (1919). Summary The injured party must act to limit the damages which arise on breach. Further reading ¢¢ Halson, Chapter 17 ‘Damages for breach of contract’, Section ‘Migration’. page 235 page 236 University of London International Programmes 16.7 Liquidated damages Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 22: ‘Obtaining an adequate remedy’ – Section 22.5 ‘Liquidated damages’ to Section 22.8 ‘Liquidated damages, penalty clauses and forfeitures: an assessment’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 9 ‘Damages for breach of contract’ – Section 9 ‘Agreed damages clauses’. Because the claimant has the burden of proving the amount of his loss, it is a great convenience to him if the contract can simply state a sum which will be payable by the defendant in the event of breach and the claimant can then sue for the stated sum. On the other hand, any such system is open to abuse if the sums might be set at a level far higher than the loss actually suffered. The House of Lords attempted to reconcile these arguments in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre v New Garage and Motor (1915) by confirming that a ‘liquidated damages’ clause is enforceable provided that the amount is a genuine preestimate of the damage and not unconscionable. The law relating to penalty clauses which was laid down in Dunlop was not reviewed by the House of Lords or Supreme Court for another 100 years until 2015. Cavendish Square Holdings BV v Makdessi and Parking Eye Ltd v Beavis [2015] UKSC 67 was a combined appeal heard by a seven person Supreme Court where the origins and practice of stipulated damages was extensively reviewed and significant changes introduced. The wide application of the principles to emerge from that case can be seen from the very different facts of the two combined appeals, the first concerning two clauses in a substantial commercial contract which if enforceable would reduce the consideration payable by more than $44 million; the second the enforceability of an £85 charge for ‘overstaying’ at a car park. The Cavendish case involved the sale by its founder of a major stake in a large Middle Eastern advertising and communications group under which the founder seller undertook not to compete with the business he sold. The contract further provided that if he breached the non-competition provisions he would lose any entitlement to outstanding instalments and be required to sell his retained holding without compensation for goodwill. When he breached the non-competition provisions the combined effect of the two clauses was that he would receive $44 million less for his share of the group. Parking Eye was the manager of a car park located in a retail park. Notices at the site stated that any car overstaying the two hour free parking would become liable to pay a parking charge of £85. The Supreme Court held that neither contractual provision was a penalty. In particular in the Cavendish appeal the Supreme Court recognised that a stipulated damages clause which provided for the payment of a sum greater than compensation may nonetheless be regarded as protecting a legitimate interest of the innocent party. The following points were noted by the Supreme Court (SC). uu The SC chose to restate, but not to abolish, the penalty rule. uu In a contract between ‘properly advised parties of comparable bargaining power’ there should operate a ‘strong initial presumption’ of enforceability. uu The definition of a penalty stated by Lord Dunedin in Dunlop as a clause that provided for the payment of a sum that was greater than ‘a genuine pre-estimate of loss’ will no longer apply. uu The test for a penalty is now: ‘whether the impugned provision is a secondary obligation which imposes a detriment on the contract-breaker out of all proportion to any legitimate interest of the innocent party in the enforcement of the primary obligation’. uu The SC confirmed that the penalty rule would continue to apply to clauses requiring a party to transfer assets at undervalue as much as to those requiring a payment to be made. Contract law 16 Damages uu A clause which provides that a payment (or other obligation) is to be made upon an event other than the payor’s breach of contract will not fall within the ‘penalty jurisdiction’. Some care is needed to avoid confusion over the word ‘penalty’. At one level, the term has a purely factual or descriptive meaning. In contracts which contain liquidated damages, these clauses are commonly referred to as providing for ‘penalties’ (i.e. ‘penalty clauses’). At another level, quite distinct from the use of the word ‘penalty’ by the parties to the contract, a penalty, as a matter of legal interpretation, is an invalid contractual provision. The law views a clause which provides an excessive agreed sum to the injured party as invalid because the sum is ‘penal’. There is, in other words, a difference between what the parties to a contract have called a provision (as a matter of fact) and how a court will categorise a provision (as a matter of law). See, for example, Ford v Armstrong (1915) and Bridge v Campbell Discount (1962). For a contrast, however, see Lombard North Central v Butterworth (1987). In practice, however, the importance of penalty clauses in the strict sense is much reduced by the ease with which similar results can be achieved by other (unobjectionable) devices. Three devices are outlined in McKendrick (22.6 ‘Evading the penalty clause rule’). 1. The penalty clause rule does not apply to a clause which accelerates an existing liability. 2. Because the penalty clause rule only applies to breaches of contract, the parties can legitimately stipulate that an amount shall be payable on an event which is not a breach of contract. 3. The parties can stipulate that a term is a condition which is of the essence of the contract with the effect that breach of the term allows the injured party to terminate the contract and claim damages. Note that a deposit is paid by way of security and is generally irrecoverable as long as the sum paid by way of deposit is reasonable. Further reading ¢¢ Cavendish Square Holdings BV v Makdessi and Parking Eye Ltd v Beavis [2015] UKSC 67 (the case restates the law in this area and is not yet incorporated into any textbook account but it is 120 pages long!) Examination advice A review of past examination papers reveals that questions involving damages often appear in connection with issues surrounding breach of contract. It appears that examiners are likely to want to test your understanding of the material covered in this chapter in one or both of two ways. 1. You may be asked to explain some of the general principles governing the award of damages, in particular those principles, such as the rules of ‘remoteness’, which place limits on the damages which can be recovered. 2. Issues as to damages – and other possible remedies – may be introduced as subsidiary, but nevertheless important, aspects of any problem in which a contract has, or may have, been broken. In other words, a question may require discussion both of offer and acceptance (or consideration, or frustration, or whatever) and of damages and/or restitutionary remedies. It will, therefore, be difficult, if not impossible, to do well in the examination without a thorough knowledge of remedies. A review of past examination papers reveals that questions involving restitutionary remedies have occurred in the context of questions involving other issues, such as illegality, capacity and damages. page 237 page 238 University of London International Programmes Sample examination questions Question 1 Captain Birdseye was a fisherman. The fishing industry was becoming unprofitable so he decided to go into marine salvage. Accordingly in September, he had his trawler, The Heron III, converted to undertake such operations at a cost of £20,000. Captain Birdseye was approached by Arty, a TV producer for Channel Poor, who was interested in making a documentary about marine salvage. He agreed to pay Captain Birdseye £20,000 for the exclusive right to film the salvage of a wreck, if one was located during October. On 5 October Captain Birdseye purchased the right to salvage a sunken tanker, said to be lying at a particular chart reference, from Dreadnought Co for £30,000. From the description of the tanker given him Captain Birdseye anticipated a profit of about £50,000 from the sale of salvageable metal, etc. On 10 October, Captain Birdseye steamed to the chart reference with the film crew on board and spent 21 days unsuccessfully trying to locate the wreck. In fact no sunken tanker existed at the chart reference given. Dreadnought Co had made a mistake as to the location of the wreck. It was in fact located a considerable distance away. Captain Birdseye returned to port. He was very disappointed that his first salvage operation had been a ‘flop’. He was also annoyed because the expedition had cost him £5,000 in fuel and crew’s wages and he ‘lost’ the TV contract. Captain Birdseye sues Dreadnought Co for breach of contract. This they admit. Advise Captain Birdseye as to the damages he is entitled to in respect of this breach. Question 2 L hired a band, the Fairies, to play at L’s daughter’s engagement party. The fee was agreed at £10,000. It was agreed that the Fairies would arrive at the party venue one day before the performance to ensure presence on the day. In fact, when the Fairies arrived their lead singer, Tacky, was not with them as he was performing elsewhere. On the day of the engagement party Tacky arrived one hour before their performance was scheduled to take place. Tacky was unwell because he had drunk too much the night before. L told the Fairies that they had broken their contract and would not be required. Advise L, who had engaged another band at a fee of £20,000 due to the short notice. What difference, if any, would it make to your advice if: a. L had sold tickets to the value of £100,000 and the purchasers demanded a refund, or, b. L had been unable to find an alternative band and the engagement party, which had cost £150,000, was a dreadful flop. Question 3 M and N arrange to have the electrical system in their house re-wired. Due to the extensive disturbances that this will entail, they move to temporary accommodation for one month. They inform O, the electrician, that they will have to return at the end of the month. O assures them that the work will be finished by this time. It is not. M and N are forced to live in a house without any electricity. M is forced to spend £500 on a laundry service, food delivery service and a multitude of candles. N is unable to bear the stress of living in these circumstances and suffers a nervous breakdown as a result. Advise O with regard to his liability. Question 4 ‘Damages are not an adequate remedy for a breach of contract.’ Discuss. Contract law 16 Damages Advice on answering the questions Question 1 The question is about damages only. This is indicated by the instruction at the end. Any discussion of breach or termination would therefore be irrelevant and get no credit. It is suggested that you begin an answer on damages with a general statement about the general compensatory aim of an award of damages for breach of contract such as that of Lord Bingham in The Golden Victory (2007). You should consider the expectation measure first. Remember it has been described as ‘the contractual measure’ to emphasise its primacy (Lord Nicholls in Nykredit plc v Edward Erdman). Define the expectation interest perhaps using the famous statement of Baron Parke in Robinson that: Where a party sustains a loss by reason of a breach of contract he is so far as money can do it to be placed in the same situation as if the contract had been performed. Under the expectation measure consider the following items of loss: £50,000 loss of profit Can this be proved with the required degree of certainty? The cases of McRae v CDC and Anglia Television v Reed would suggest not. £20k loss from the contract with Channel Poor This is a classic remoteness situation like that in Victoria Laundries v Newman (i.e. the breach of a contract between A (Dreadnought/Engineers in Victoria) and B (Capt Birdseye/Laundry in Victoria) causes the loss of another contract between B and a third party (Channel Poor/Ministry of Supply in Victoria)). At this point you should be able to write a substantial paragraph on the applicable test for remoteness starting with the two limbs of Hadley v Baxendale, their application in Victoria Laundries, the refinement on probability in The Heron II and then the current status of Lord Hoffmann’s comments in The Achilleas. Applying Hadley the loss of this unusual contract would not come within the first limb and there is no evidence of communication by Birdseye to Dreadnought to bring it within the second limb. Non-pecuniary loss Do not neglect to discuss whether Birdseye can recover damages for non-pecuniary loss as we are told that he was ‘disappointed’ that his venture has been unsuccessful. This contract does not come within the categories where such damages are recoverable. All those categories involve consumers and so such damages are not a feature of purely commercial contracts. Reliance measure The £5,000 spend on fuel and crew’s wages is recoverable as reliance measure damages (sometimes called damages for wasted expenditure) as in McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission and Anglia TV v Reid. The £20,000 cost of conversion is not recoverable as reliance measure damages. This expenditure is not wasted as a result of Dreadnought’s breach as Birdseye still has a trawler capable of salvage operations. Another reason this sum is not recoverable is because it was so called ‘pre-contractual reliance’ (i.e. the expenditure was made before, anticipated the contract with Dreadnought and so could not be described as money spent in reliance upon that contract). Pre-contractual reliance has only exceptionally been recovered and then only if the expenditure is necessarily wasted as a result of the breach (Anglia TV v Reid). The £30,000 purchase price for the right to salvage would be recoverable either under the reliance measure of damages or under the restitution measure if Dreadnought was regarded as having given nothing in exchange for it (i.e. there was a total failure of consideration). page 239 page 240 University of London International Programmes Question 2 This question requires you to consider issues of both breach of contract (and damages) and frustration. It is an error to consider the question as either one or the other: you need to explore both sets of issues to answer the question fully. With regard to frustration, the argument could be made that Tacky’s late appearance and his unfit state is a supervening event which radically changes the nature of the obligation (National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina (Northern) Ltd (1981)). However, this event is attributable to the default of one of the parties to the contract. The issue is then whether the Fairies have breached a condition of the contract, or a sufficiently fundamental Hong Kong term so as to allow L to rescind the contract for breach. If it is not, L is himself in breach of contract. It does seem to have been emphasised in the contract that the Fairies had to be able to perform on the day; it is likely in the circumstances that L is entitled to rescind the contract. The issue then to be considered is the appropriate measure of damages available to L. The purpose of awarding damages is to put L in the position he would have been but for the breach. Candidates are given two variants. In variant (a), L has sold tickets and will want to seek damages measured on an expectation basis – and seek to recover the profit he would have made from the performance. It may be that such a loss is too remote to recover (Hadley v Baxendale (1854)) because it was not a loss which arose naturally or was contemplated at the time of contracting. It would not normally be the case that a profit would be made by the host in connection with an engagement party. In variant (b), L may wish to seek his wasted expenditure – see Anglia Television v Reed (1972), and CCC Films v Impact Films (1984)). In both variants, it is arguable that L should recover damages for non-financial loss, namely the distress caused by the breach of a contract to provide enjoyment – see Jarvis v Swan Tours (1973), Jackson v Horizon Holidays (1975) and Farley v Skinner (2001). Question 3 This question involves two issues: is there a breach of contract and, if so, what are the damages available for the breach? Again, you need to consider both issues to answer the question. The first issue is whether or not the assurance of O that the work will be finished in a month is a term of the contract. On balance, it appears to be. If it is a term of the contract, what sort of term is it: a condition, warranty or an innominate term? In other words, does breach of the term entitle M and N to terminate the contract? On balance, the term appears to be either a condition or a sufficiently important innominate term to entitle M and N to terminate the contract. This leaves the question as to what damages are available for the breach. To what extent can M and N recover the £500 spent on laundry, meals and candles? An answer to this issue entails a consideration of whether or not the loss is too remote according to the principles established in Hadley v Baxendale (1854) and as refined and explained in successive cases. On balance, the losses do not seem too remote – they arise in the natural course of things and should have been within the reasonable contemplation of the parties at the time of contracting. More problematic is the possible recovery by N for his nervous breakdown. On the one hand, the House of Lords held in Addis v Gramophone Co Ltd (1909) that the plaintiff was not entitled to compensation for hurt feelings. On the other hand, more recent courts have moved away from an absolute rule prohibiting recovery for mental stress (see Ruxley Electronics v Forsyth (1996), Mahmud v BCCI (1998), Johnson v Unisys (1999) and – importantly – Farley v Skinner (2001)). Question 4 You need to examine the extent to which a restitutionary remedy based upon the profit of the wrongdoer would provide an adequate remedy. This would involve consideration of the House of Lords’ decision in Attorney-General v Blake (2000). A number of possible circumstances might occur. Two were suggested by the Court of Appeal in Blake’s case. One would be in the instance of a ‘skimped performance’ where Contract law 16 Damages the defendant delivers a sub-standard performance of the contract and, in so doing, saves money without causing the claimant loss. The second would be ‘where the defendant has obtained his profit by doing the very thing which he contracted not to do’. Other possibilities exist, particularly where a compensatory measure of damages results in a nominal award of damages and yet the wrongdoer has obtained a vast profit. Quick quiz Question 1 The principal purpose of an award of damages for a breach of contract is best described by which of the following statements? Choose one answer. a. To punish the defendant for their wrongful conduct. b. To put the claimant in the position they would have been but for the breach of contract. c. To put the claimant in the position they would have been had the contract been performed. d. To take from the defendant any benefit they might have obtained from the breach of contract. e. Don’t know. Question 2 How did Lord Denning, in the case of Jarvis v Swan Tours Ltd (1973), justify the extension of damages to include mental distress and anxiety? Choose one answer. a. But the rule is not absolute. Where the very object of a contract is to provide pleasure, relaxation, peace of mind or freedom from molestation, damages will be awarded if the fruit of the contract is not provided or if the contrary result is procured instead. b. It should not include any case where the object of the contract was not comfort or pleasure or the relief of discomfort, but simply carrying on a commercial contract with a view to profit. c. I think those limitations are out of date. In a proper case damages for mental distress can be recovered in contract, just as damages for shock can be recovered in tort ...If the contracting party breaks his contract, damages can be given for the disappointment, the distress, the upset and frustration caused by the breach. I know it is difficult to assess in terms of money, but it is no more difficult than the assessment which the courts have to make every day in personal injury cases for loss of amenities. d. There are many circumstances where a judge has nothing but his common sense to guide him in fixing the quantum of damages, for instance, for pain and suffering, for the loss of pleasurable activities or for inconvenience of one kind or another. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following scenarios WOULD result in damages being awarded? Choose one answer. a. A shipowner agrees to carry a cargo of sugar belonging to a sugar merchant to a specified place of delivery. The shipowner breaches the contract by late delivery and then the sugar merchant claims loss of profit for late sale. page 241 page 242 University of London International Programmes b. A mill owner engages a carrier to take a broken mill shaft to a specified place as a pattern for a new one. The carrier promises to deliver it to a different place the next day. This process of delivery is delayed due to the carrier’s negligence. The mill owner then tries to recover damages for the loss of profits stemming from the delay of delivering the broken mill shaft as no spare was available. c. A laundry order a larger boiler to expand their business. They are due to acquire a particularly lucrative laundry contract but this is not disclosed to the seller. Due to the delay of delivery the laundry wish to recover damages for losing a particularly lucrative laundry contract. d. A seller of property agreed with a buyer to sell premises in a specified place. Unknown to the sellers the buyer wished to buy the property with the purpose of converting the premises for himself. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Which statement best summarises the reason for the decision in Ruxley Electronics & Construction Ltd v Forsyth (1996)? Choose one answer. a. Damages are either calculated on the basis of difference of value or cost of cure. b. Damages will be awarded where you have entered into a bad bargain. c. Damages should be awarded on the basis of the loss suffered. d. Damages are always awarded regardless of the injured parties’ attempts to mitigate the loss. e. Don’t know. Question 5 The importance of Transfield Shipping Inc v Mercator Shipping Inc (The Achilleas) (2008) is best summarised by which of the following statements? Choose one answer. a. The court must look carefully to determine which party is most at fault in the breach of contract to determine whether or not a particular loss is too remote to recover. b. In deciding whether or not loss is recoverable one has to ask whether or not the defendant accepted responsibility for the loss in respect of which the claim has been brought. c. Damages for a breach of contract should be awarded for those losses arising naturally from such a breach or as may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties at the time they made the contract. d. Remoteness of damages is a question of law which should be determined by the consideration of whether there is an economic loss, such as a loss of profit, or whether there is an injury actually done to the person or his property. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Contract law 16 Damages Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is the aim of damages for a breach of contract? 2. Upon what principles are damages assessed? 3. How can damages be measured? 4. What are the limitations upon an assessment of damages and the circumstances in which damages are too remote to be recovered? 5. What is the nature of a restitutionary remedy and when is it available? 6. What limitations attend a restitutionary remedy? 7. What are the differences between a restitutionary measure and expectation and reliance measures of damage? 8. What does ‘mitigation of damages’ mean? 9. To what extent are damages provided for non-financial loss? 10. What is the ability of parties to stipulate their damages through the use of liquidated damages clauses? page 243 page 244 Notes University of London International Programmes Part VIII Remedies for breach of contract 17 Equitable remedies Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 246 17.1 Specific performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247 17.2 Damages in lieu of specific performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17.3 Injunctions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 250 249 Quick quiz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251 Am I ready to move on? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 252 page 246 University of London International Programmes Introduction In the common law, damages are the principal remedy for a breach of contract. Damages will, thus, be the usual remedy awarded to the injured party. The common law, through the operation of equity, possesses further remedies in addition to an award of damages at common law. These remedies seek the performance of the contract rather than damages to rectify the breach of the contract. The performance may be through an order of specific performance: that is to say, an order which compels the party in breach to perform the contract. This is a positive order – an order which compels a party to perform. Another equitable remedy available is an injunction – an order which prohibits a party from certain actions. Many contracts contain covenants which oblige a party not to do something; in some circumstances, courts will give effect to those clauses to prevent the party from doing that which they covenanted they would not do. LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter introduces the equitable remedies of specific performance and injunction to enable you to discuss and apply in problem analysis its key components (and supporting authority) including: uu The nature of an order for specific performance or an injunction. uu The availability of, and the restrictions on, an order for specific performance. uu When an injunction is available. uu The circumstances when damages might be given in lieu of an order for specific performance. Contract law 17 Equitable remedies 17.1 Specific performance Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 22 ‘Obtaining an adequate remedy’ – Section 22.9 ‘Specific performance’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 10 ‘Remedies providing for specific relief and restitutionary remedies’ – Section 2 ‘Specific performance and injunctions’. 17.1.1 An exceptional remedy An order for the specific performance of a contract is an exceptional remedy. While it appeared at one point that the use of specific performance was on the increase following the decision in Beswick v Beswick (1968), it is clear from the House of Lords’ decision in Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores (1997) that specific performance remains an exceptional remedy. In that case, the House of Lords was reluctant to extend the traditional ambit of an order for specific performance and clung rigidly to the old restrictions on its application. An order for specific performance is made when damages are an inadequate remedy. Where damages are an adequate remedy, an order for specific performance would not be made. In Behnke v Bede (1927) specific performance was granted when a ship was sold which was ‘of peculiar and practically unique value [to the claimant]’. In contrast, in Societe des Industries Metallurgiques SA v The Bronx Engineering Co Ltd (1975) specific performance was refused in respect of a contract to build a complicated piece of manufacturing machinery that weighed 220 tons and took 9–12 months to complete. It was assumed that though there would be an inevitable delay damages would be an adequate remedy because they allowed the injured party to purchase replacement goods in the market. In contrast, damages for a breach of a contract to sell land are viewed as inadequate and the usual remedy in such a case is an order for specific performance: Johnson v Agnew (1979). A number of recent cases have concerned specific performance of obligations where if such an order was not made immediately the possibility of ever doing so would be lost. In Sky Petroleum v VIP Petroleum [1974] 1 WLR 576 effective specific performance was granted to force the defendant to maintain fuel supplies to the claimant. The fuel market was in turmoil and so if this order was refused the claimant had no realistic prospect of getting a substitute supply. Similarly, in Thames Valley Power Ltd v Total Gas and Power Ltd (2005) it was said, obiter, that specific performance would be ordered to enforce a long term contract to supply gas to an airport’s power facility when the delays involved in a claim for damages would result in the insolvency of the business. Another consideration in awarding specific performance is that in some cases it may be extremely difficult or impossible to quantify the claimant’s loss: Decro-Wall International SA v Practitioners in Marketing Ltd (1971). In addition, courts have considered whether or not the defendants would be able to pay an award of damages. There are indications that where this seems unlikely, an order for specific performance may be made: Evans Marshall & Co Ltd v Bertola SA (1973). Courts will consider whether or not, in all the circumstances, an order for specific performance is just. 17.1.2 Restrictions on orders for specific performance In a number of situations, an order for specific performance will not be made. Another way of stating this is to say that certain factors prevent an order for specific performance. It is important to remember that since an order for specific performance is an equitable remedy, it is also a discretionary remedy. It does not follow as a matter of right; it is left to the discretion of the courts to decide whether or not to make the award. The court does not exercise this discretion in an arbitrary fashion but in accordance with strict page 247 page 248 University of London International Programmes rules and practices: Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores (Holdings) Ltd (1998). In the Argyll case the House of Lords held that specific performance was not available in respect of a ‘keep open’ covenant in a long lease. It is a common feature of commercial property development that certain tenancies are key to the success of the enterprise. If well known stores take key tenancies the remaining units are easier to let. The lease to a key tenant will also contain some commitment to stay open for a minimum period each week. An important ground upon which specific performance is refused is where the order would require the ‘constant supervision’ of the courts. In the Argyll case an order for specific performance was refused inter alia on this ground (also because damages were said to be an adequate remedy and that if granted the landlord would exploit the tenant by demanding a high value for the release of the obligation). In discussing these points, Lord Hoffmann was careful to point out that the problem was not that the court would have to physically supervise the order, but that continual appearances for further orders for a contempt of court would have to be made. The following restrictions apply. uu The claimant’s conduct must be beyond question. This rests upon the equitable maxim that ‘he who comes to equity must come with clean hands’. Specific performance will be refused if the party who seeks it has induced the defendant to enter into the contract with a promise which he has then failed to perform. uu Likewise, if the party claiming the order has performed the contract in an unfair manner the order will be refused. The court may refuse specific performance of a contract where the contract has been obtained by means which are unfair. It is not necessary that the unfairness amounts to grounds upon which the contract can be invalidated. uu A court will not make an order for specific performance where this would result in severe hardship to the defendant. This also includes cases where the cost to the defendant would substantially outweigh any benefit to the claimant: Tito v Waddell (No 2) (1977). uu The court will not order specific performance where it is impossible for the defendant to comply with the order. Thus, if the defendant has contracted to sell land which he does not own, a court will not make an order to compel him to sell this land. uu There must also be a mutuality of remedy. Courts will sometimes refuse to order specific performance of a contract at the request of one party if it could not order it at the request of the other party. Thus, if one party has promised to perform personal services, the court will not accede to his request for specific performance on the part of the other party as specific performance would not be ordered against him: Page One Records v Britton (1968). In this case, the first plaintiff was engaged as a manager by the defendants, a band named The Troggs. Stamp J held that as the band could not receive an order for specific performance for the plaintiff to perform his management contract, the manager could not receive an Figure 17.1 The Troggs order which obliged the defendants to keep him as their manager. This ‘lack of a mutuality of the right of enforcement’ prevented the plaintiff from receiving an interlocutory injunction preventing the band from engaging another as their manager. uu Lastly, courts will not make an order for specific performance with regard to certain kinds of contracts. The most important of these are contracts for personal services (or employment) – those contracts where one party has agreed to serve another. Contracts which involve the performance of personal services are not, on the whole, subject to an order for specific performance. Courts are strongly reluctant (although have no particular rule against it) to decree specific enforcement of an Contract law 17 Equitable remedies employment contract. It has long been thought undesirable that parties be forced into an employment relationship. In addition, there is the practical difficulty of determining whether or not there has been a proper performance. In Giles v Morris (1972), Megarry J stated: The reasons why the court is reluctant to decree specific performance of a contract for personal services (and I would regard it as a strong reluctance rather than a rule) are, I think, more complex and more firmly bottomed on human nature …who could say whether the imperfections of performance were natural or self-induced?! However, in some circumstances, a court will order that parties enter into a contract although they would not order them to perform the contract. In the decision of Giles v Morris the court drew a distinction between an order to perform a contract for services and an order to procure the execution of such a contract. The mere appearance of one provision which would not be specifically enforceable did not prevent the contract as a whole from being specifically enforced. The contract must be regarded as a whole and the desirability of specifically enforcing it outweighed the disadvantages of specifically enforcing the obligation to perform personal services. Activity 17.1 Why are damages not considered to be adequate compensation for the breach of a contract for the sale of land? Activity 17.2 Would an order for specific performance in a contract of services be tantamount to slavery? Summary In exceptional cases, an order for specific performance may be made following a breach of contract. The order is a discretionary remedy and a claimant must establish that the discretion of the court should be exercised in her favour. The court will consider the exercise of its discretion in the light of established principles and practices. Further reading ¢¢ Anson, Chapter 18 ‘Specific remedies’. 17.2 Damages in lieu of specific performance Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 21 ‘Obtaining an adequate remedy’ – Section 21.11 ‘Damages in lieu of specific performance’. The court has the power to award damages in addition to or in substitution for specific performance by reason of s.50 Senior Courts Act 1981. It applies wherever the court has the jurisdiction to entertain an application for an injunction or specific performance. It cannot make such an award where the ability to seek the specific relief has been lost (e.g. through lapse of time). Claims for damages can be combined with claims for specific performance or injunction although it is generally unnecessary to resort to the special power to award damages in lieu of these remedies (s.49 Supreme Court Act 1981). In Wroth v Tyler (1974) it was said that damages are made in substitution for specific performance and must ‘constitute a true substitute for specific performance’. The damages awarded must provide as nearly as possible what specific performance of the contract would have provided. In Johnson v Agnew (1980) the House of Lords accepted that damages must be assessed by the same principles whether claimed in law or in equity. page 249 page 250 University of London International Programmes Further reading ¢¢ Eisenberg, M.A. ‘Actual and virtual specific performance, the theory of efficient breach, and the indifference principle in contract law’ (2005) 93 California Law Review 975. 17.3 Injunctions Essential reading ¢¢ McKendrick, Chapter 22 ‘Obtaining an adequate remedy’ – Section 22.10 ‘Injunctions’. ¢¢ Poole, Chapter 10 ‘Remedies providing for specific relief and restitutionary remedies’ – Section 2 ‘Specific performance and injunctions’. So far we have dealt with orders of specific performance – that is, orders where the parties are compelled to perform positive obligations. We now turn to a consideration of negative obligations – that is to say, when a party promises not to do something or to refrain from doing something. In this case, equity offers the possibility of an injunction by the court prohibiting some form of conduct. The court is enforcing a negative stipulation. An injunction is also a discretionary remedy. However, courts will generally order it as a matter of course. They will not order it where it would cause such a particular hardship to a defendant as to be oppressive to him. See Insurance Co v Lloyd’s Syndicate [1995] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 273 at 276. It is important to consider that a court will not grant an injunction where to do so would be to indirectly order specific performance: Page One Records v Britton (1968). In many cases, however, courts have refused to recognise that the grant of an injunction preventing the party from employment with another effectively compels them to specifically perform the first contract. See, for example, Warner Bros v Nelson (1937) where the court found that the defendant was a person of ‘intelligence, capacity, and means’. The grant of an injunction preventing her from acting for anyone other than the plaintiffs would not compel her to act for the plaintiffs. That this can be an artificial distinction is, to a certain extent, recognised in later cases such as in Page One Records v Britton (1968) and Warren v Mendy (1989). Like an order for specific performance, an injunction is a discretionary remedy and a court will only order it where it is just to do so. Activity 17.3 Will an injunction be awarded if it has the same effect as an order for specific performance? Summary A breach of a negative covenant in a contract may be restrained by the grant of an injunction. An injunction is an equitable remedy; the effect of an injunction is to prohibit certain conduct. An injunction will not be granted in circumstances where it has the effect of compelling the positive covenants in a contract where an order for specific performance would not be granted. Further reading ¢¢ Treitel, Chapter 21, paras 21-052–21-060. Examination advice A review of past examination papers reveals that questions involving equitable remedies appear infrequently. When equitable remedies are involved in an examination question, they tend to appear as a part of a larger question that also involves issues of breach or damages. Contract law 17 Equitable remedies Sample examination question ‘Damages are not an adequate remedy for a breach of contract.’ Discuss. Advice on answering the question This question expects you to describe the nature of damages as a remedy for a breach of contract. A good answer will display a knowledge of the principles established in the relevant case law. To answer the question you need to analyse what a breach of contract is and to what extent damages are not an adequate remedy. In certain ways, damages are not an adequate remedy. For example, an award of damages is premised, to a certain extent, on the availability of substitutes. Where substitutes are not available, an award of damages is not an adequate remedy. Another example would be where the contract is for the performance of a unique service. It may also be that in certain circumstances the performance interest of the claimant will not be recognised in an award for damages (see, for example, Panatown v McAlpine Construction (2000)). In other cases, damages may not operate to provide a real compensation for the loss (see, for example, Ruxley Electronics and Construction v Forsyth (1996)). The question then draws you to consider other remedies available in equity – such as an injunction or an order for specific performance. You need to consider the nature of these remedies and the extent to which they can rectify the shortcomings of an award of damages. Quick quiz Question 1 Which of the following is not an equitable remedy available for a breach of contract? Choose one answer. a. Damages. b. Damages in lieu of specific performance. c. An order for specific performance. d. An injunction. e. Don’t know. Question 2 In which of the following circumstances is a court unlikely to make an order for the specific performance of a contract? Choose one answer. a. Where A has contracted to sell his house to B. b. Where A has contracted to sell his car to B. c. Where A has contracted with B to pay C an annuity. d. Where A has contracted with B to provide B with a service and A would be unable to pay an order for damages. e. Don’t know. Question 3 Which of the following is not a potential restriction courts will consider in deciding whether or not to exercise its discretion to make an order for specific performance? Choose one answer. a. The contract is for the performance of personal services. b. There must be mutuality of remedy. page 251 page 252 University of London International Programmes c. Where an order for specific performance would cause severe hardship to the defendant. d. Where an order for specific performance would cause a benefit to the defendant. e. Don’t know. Question 4 Read carefully Lord Hoffmann’s judgment in Co-operative Insurance Society v Argyll Stores (Holdings) Ltd (1998). Which of the following was not a consideration in that judgment? Choose one answer. a. When the matter came to court Argyll had already closed the Safeway supermarket in the Hillsborough Shopping Centre, which meant that it would be extremely difficult to re-open and re-fit the premises to resume business. b. To order specific performance in this case would be to involve the court in the constant supervision of the running of the business. c. It would be inappropriate to force a defendant to run an uneconomic business and determine how to run this business in light of the court’s order for specific performance. d. Orders for specific performance are enforced by making contempt orders when the court’s initial order has been breached and the nature of a contempt order makes it unsuitable to order specific performance in many instances. e. Don’t know. Question 5 Which of the following statements about injunctions is false? Choose one answer. a. An injunction is a mandatory order prohibiting the performance of a negative stipulation in a contract. b. An injunction will be granted in lieu of specific performance in circumstances where a court would not exercise its discretion to grant an order for specific performance. c. An injunction is granted at the court’s discretion and is subject to the usual equitable restrictions. d. An injunction will not be granted where to grant it would be tantamount to an order for specific performance in circumstances where the latter would be refused. e. Don’t know. Answers to these questions can be found on the VLE. Am I ready to move on? You are ready to move on to the next chapter if, without referring to the module guide or textbook, you can answer the following questions: 1. What is the nature of an order for specific performance? 2. What is the availability of, and what are the restrictions on, an order for specific performance? 3. What is an injunction and when is it available? 4. What is the difference between an order for specific performance and an injunction? 5. When may damages be given in lieu of an order for specific performance? Feedback to activities Contents Chapter 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255 Chapter 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255 Chapter 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 257 Chapter 4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 260 Chapter 5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262 Chapter 6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264 Chapter 7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267 Chapter 8 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267 Chapter 9 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271 Chapter 10 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 273 Chapter 11 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275 Chapter 12 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277 Chapter 13 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 278 Chapter 14 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279 Chapter 15 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280 Chapter 16 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 283 Chapter 17 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285 page 254 Notes University of London International Programmes Contract law Feedback to activities Chapter 1 Activity 1.1 Reflection upon this series of questions will make you aware of how much the law of contract lays behind ‘everyday life’. Perhaps you looked in a shop window or at a website, rang up a shop or business to ask about the availability of some good or service. All these actions are preparatory to entering a contract. If you purchased any good (newspaper, drink, lunch or shopping) or service (getting on a bus or train with a ticket) you will have entered a contract. Remember that contracts may be formal in the sense of a signed document or informal such as an oral agreement. If you are employed to work you will have (hopefully) performed some contractual duties yesterday. If you ‘returned’ a purchase to a shop or posted it back to an online supplier, if your contract with a mobile network supplier came to an end or you were ‘sacked’ from your employment you have participated in the termination of a contract as a result of breach of contract (returned goods and sacking) or performance (mobile phone). Activity 1.2 Most newspapers carry advertisements which aim to persuade readers to purchase goods and services. If untrue statements are made (called misrepresentations) the law of contract may provide a remedy to the disappointed purchaser. The business pages will directly discuss lucrative contracts concluded between businesses; perhaps the purchase of valuable TV broadcasting rights or the takeover (by the purchase of shares) of one company by another. Other sections of the newspaper may less obviously ‘involve’ contract law, for example, the sports pages may discuss the ‘transfer’ of football players for large sums of money. Such a transfer is of course a contract entered between (at least) the player, selling and purchasing clubs. Newspaper advertisements are often placed to stimulate sales by a business to consumers (i.e. private individuals); these are known as B2C contracts. The purchase of broadcasting rights and the takeover of companies are concluded between businesses and so are known as B2B contracts. Activity 1.3 No feedback provided. Chapter 2 Activity 2.1 The grocery shop has not made you an offer. They have made an invitation to treat. See Grainger & Son v Gough (1896) and Partridge v Crittenden (1968). The reason that they have only made an invitation to treat and not an offer is because if the statement in the leaflet is construed as an offer, then the shop would be bound to sell to everyone who presented themselves at the shop. Clearly, this is impractical and, indeed, may be impossible. Consequently, if you visit the shop, they do not need to sell you oranges at this price. The offer can be made by action or by statement. See Trentham Ltd v Archital Luxfer (1993). Activity 2.2 In Carlill’s case the advertiser was advertising the offer of a unilateral contract and not a bilateral contract. Only one party would be bound from the outset. Activity 2.3 This scenario is based upon a mistake made by the retailer Argos some years ago. Many trainee lawyers in London law firms placed orders before the mistake was corrected! On general contractual principles Argos would have entered a contract to supply goods at the mistaken price if the website constituted a contractual offer which was ‘accepted’ when the order was placed online. It will not surprise you to know that page 255 page 256 University of London International Programmes internet sellers now go to considerable lengths to expressly provide that the virtual advertisement does not constitute an offer. The current Argos conditions provide: 2.3 Acceptance of your order and the completion of the contract between you and us will take place on dispatch to you of the products ordered … www.argos.co.uk/static/staticDisplay?includeName/TermsAnd Conditions.htm Even if the website advertisement had constituted a contractual offer, under the so called doctrine of ‘snapping up’ (Hartog v Collins and Shields (1939)) the customers will not be able to accept an offer which they know (or should know: Scriven Bros v Hindley (1913)) is mistaken as to its terms. This principle was applied in the context of an internet site by the Singapore Court of Appeal in Chwee Kin Keong v Digilandmall.com Pte Ltd (2005)). Activity 2.4 If Clarke had been a widow, the case would be different for two reasons. First, Clarke would appear to be a more ‘deserving’ claimant and the court might have a harder time dismissing her claim. Such a consideration would not of itself be a sufficient reason to find in her favour. However, her claim might, as a result of her position, have been viewed sympathetically and the law applied and interpreted in this light. Second, the case, on the facts of it, appears to be much more similar to Williams v Carwardine. However, what is necessary for a contract to be formed, on the basis of the ratio of Clarke’s case, is that Clarke is assenting to the offer – that there is a ‘meeting of minds’. It is not clear that the widow is aware of the offer and that she acts to form the requisite consensus. Activity 2.5 A has offered the goods for sale – the requisite intention to be bound is present. B’s initial correspondence could be taken as a rejection – but it is more likely to be a request for information and the offer survives. B’s fax is good when it is communicated – probably instantly. The fax, however, adds a condition and the communication is therefore not an unqualified consent to A’s offer. On balance, this probably operates as a conditional offer – which has the effect of destroying the original offer. There is, thus, no contract. Even if there is a contract, the contract will not include the delivery price (unless such a term can be implied by reason of the course of dealing between these parties or by reason of the custom of this industry). Activity 2.6 A contract has been formed. See, for example, Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corporation (England) Ltd and Tekdata Interconnections Ltd v Amphenol Ltd (2009). If the seller fails to deliver the goods, they are in breach of the contract. Activity 2.7 If your ‘offer’ amounts to an offer in law according to the authorities set out in Section 2.1, there has been an acceptance of your offer. The acceptance has been by act, rather than by writing or by discussion. Your offer has been accepted by conduct. The oranges have been despatched in response to your request for them. Activity 2.8 Contrast the merits of a ‘receipt’ rule with those of a rule which, like the postal rule, stipulates an earlier time when acceptance is effective. Refer to the following matters. a. Does the sender know, or have the means of knowing, if the communication has not been received? b. How quickly will the sender know if the communication has not been received? c. Which party, if any, accepted the risk of using this form of communication? d. Has the communication been sent to arrive during normal business hours? Contract law Feedback to activities Activity 2.9 Your neighbour is free to withdraw her offer. The offer is not a contract and there is nothing which binds her to keep the offer open until Monday. Authority for this proposition can be seen in the case of Offord v Davies (1862). In this case, the defendant undertook to guarantee certain debts of another party for a period of a year. Before any bills were due, and within the year, the defendant cancelled the guarantee. The Court held that as the offer was not binding, it could be revoked at any time prior to the other party acting upon it. The time limit created no extra liabilities but merely stipulated a period at which liabilities will definitely come to an end. Special problems arise where the offeror has made an offer of a unilateral contract which is accepted through performance. Here, the revocation is more difficult. The English authorities appear divided as to whether or not this is possible. In Luxor (Eastbourne) Ltd v Cooper (1940) the House of Lords allowed an offeror to revoke its offer once the offeree had performed the act stipulated, whereas in Errington v Errington (1952) the Court of Appeal did not allow revocation. The proper reconciliation of the cases is that such revocation will only be allowed where, as in Luxor, no extra undertaking can be implied into the contract whereby the offeror can be considered to have impliedly promised not to revoke the unilateral offer after performance has started. Activity 2.10 uu June 6 – Defendant’s letter to the plaintiff offering to sell property for £1k satisfies the definition of an offer (i.e. it is a definite offer to be bound if certain conditions are met). It specifies exactly the key price term being proposed. uu June 6 – Plaintiff’s response (via an agent) offering to purchase the property for £950 is a counter offer because it is substantially different to the original offer. This has two effects: it acts as a rejection of the offer to sell for £1k and stands as a new offer to buy the property for £950. uu June 27 – The defendant’s letter saying he could not accept the plaintiff’s offer was simply a rejection. uu June 29 – The defendant’s purported acceptance of the original offer to sell the property for £1k cannot be an acceptance. An acceptance can only take effect in response to a prior and subsisting offer. The defendant’s original offer to sell for £1k came to an end (was ‘terminated’) when it was rejected. uu It is sometimes said that the law looks to the ‘substance’ not the ‘form’ of communications. The analysis of the June 29 communication illustrates this. It cannot be the acceptance it purports to be because there is no prior offer. However, it could be interpreted as an offer to purchase the property for £1k. uu However, no contract is concluded as there is no evidence of a subsequent acceptance by the defendant of the claimant’s offer to purchase the property for £1k. Chapter 3 Activity 3.1 You should have noted that cleaning the windows is a benefit to A. It is also a detriment to B (despite the fact that B will receive £30), in that B will be expending effort, and could be using the time to do other things. B’s actions are therefore clearly consideration under the Currie v Misa (1875) definition. Activity 3.2 This is the reverse of situation 1. A’s payment of the £30 is a detriment to A and a benefit to B. Again this fits with Currie v Misa. page 257 page 258 University of London International Programmes Activity 3.3 B is only in breach of contract if A provided consideration for the promise to clean the windows on Tuesday. The only possible consideration is A’s promise to pay £30. As we have seen, the courts are prepared to treat the promise to do something as consideration. By promising to pay £30, A has provided consideration for B’s promise to clean the windows. B is therefore in breach of contract. It is difficult, however, to fit this within the Currie v Misa definition of consideration and is better explained by the concept of ‘mutuality’ in exchange. You might also have noted that if the agreement between A and B was in the form of a unilateral contract with A saying: ‘If you clean my windows on Tuesday, I will pay you £30’, B would not be in breach of contract. Activity 3.4 Denning LJ found consideration in the mother’s promise to provide for the child’s upkeep. This clearly has economic value, but raises the question of whether doing something which the law already obliges you to do can ever be good consideration. This is discussed below, in the feedback to Activity 3.13. The majority of the Court of Appeal, however, seems to have found consideration in the mother’s promise to ensure that the child was happy. This does not involve anything of economic value. Can it be distinguished from White v Bluett? It is difficult to see how. This suggests that the requirement of economic value may no longer be part of the doctrine of consideration. Activity 3.5 The Court of Appeal found that the pupil did not provide consideration as regards her pupil master, but did do so as regards the chambers. This was on the basis that the chambers benefited from attracting talented pupils who might become tenants and enhance the development of the chambers. As Lord Bingham put it: ‘We take the view that pupils such as the claimant provide consideration for the offer made by chambers… by agreeing to enter into the close, important and potentially very productive relationship which pupillage involves’. The economic benefit to the chambers, if any, is therefore indirect – in that in the future the pupil may become a tenant and bring additional work to the chambers, enhancing its reputation and increasing the income of its members. Again, however, the court does not appear too concerned about the issue of ‘economic value’. This suggests, as does Ward v Byham, that this element in the definition of consideration has less importance than is sometimes alleged. You might also have noticed that the pupil could have argued that she was providing consideration through suffering at least a short-term economic detriment, in that she could have taken more secure paid employment elsewhere. This line of argument was not, however, explored by the Court of Appeal. Activity 3.6 The plaintiff in Collins v Godefroy, in giving evidence as a witness in response to a subpoena, was only doing his public duty. It is clearly undesirable for witnesses (other than expert witnesses) to be paid for giving testimony. This principle is now reflected in statutory provisions which allow police authorities to charge for ‘special services’ only that extend beyond their general obligation to prevent crime, protect property and maintain law and order. Activity 3.7 There are at least two possible answers to this question. The first is, as suggested by Lord Denning, that the performance of an existing legal obligation should be treated as good consideration, ‘so long as there is nothing in the transaction which is contrary to the public interest’ (see also Williams v Williams (1957)). The more orthodox view, which was taken by the majority in Ward v Byham was that the mother had done more than her legal duty in relation to her care for her daughter (i.e. following the same line as Glasbrook Bros Ltd v Glamorgan CC). The implication is that if the mother had done simply what the law required her to do she would not have provided good consideration. The problem with the majority view on the particular facts of the case is that, as noted in Section 3.1.2, it is difficult to see that the mother’s actions had any Contract law Feedback to activities page 259 economic value. A different approach would emphasise as consideration the mother’s preparedness to show that the child was well looked after and happy. The mother was under a statutory obligation to maintain the child but not to prove this. If this is correct, her undertaking, upon request, to demonstrate the child’s positive welfare might constitute an extra undertaking sufficient to satisfy the orthodox test. Activity 3.8 The main alternative explanation of Stilk v Myrick is that it was based on the fact that the pressure put on the captain by the crew was a kind of extortion. To that extent, the case is an early example of a type of ‘economic duress’ (see Chapter 10). This way of viewing the case has become more attractive since the Court of Appeal’s decision in Williams v Roffey, since it avoids the potential conflict between the two cases. Prior to that, however, the courts regularly treated Stilk v Myrick as being based solely upon issues of consideration.† Activity 3.9 The main basis for distinction is that in Hartley v Ponsonby the situation had become so perilous as a result of the reduction in the crew that the surviving members were, in continuing with the voyage, doing more than their original contract would have obliged them to do. The case is thus an example of the principle that doing more than your existing obligation will amount to good consideration for a fresh promise. Activity 3.10 You should have noted the speeches of Lord Selborne at p.613, Lord Blackburn at p.622 and Lord Fitzgerald at p.630. Activity 3.11 There are two main reasons which you might have identified. First, there is the problem that Foakes v Beer is a decision of the House of Lords. The doctrine of precedent does not therefore permit the Court of Appeal to overrule it. A full reconsideration of the case will therefore have to await a case which is appealed to the House. Secondly, the Court may well have been reluctant to embark on a general relaxation of the rule as to part payment of debts, because it is a situation where the debtor may often be able to put the creditor under pressure to accept such an arrangement, and such pressure may go beyond what the courts feel is acceptable. See, for example, the case of D & C Builders v Rees (1966), discussed in 3.2. It may be the case that the development of the doctrine of economic duress examined in Section 10.1 which now offers better, perhaps sufficient, protection from unfair pressure is the reason why Foakes v Beer, although not overruled, has recently been qualified by the Court of Appeal’s extension of the concept of ‘practical benefit’ in MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd (2016). Activity 3.12 The problem for the plaintiff in Re McArdle was that he acted by himself, without any request, or even approval, from the rest of the family. By contrast in Re Casey’s Patents the owners of the patents knew that the manager was doing the work. In Re McArdle it could not be said, looking at the events objectively, that all the parties anticipated that the work would be paid for, because at the time only the plaintiff knew that the work was being done. The same answer would be arrived at by applying Lord Scarman’s test in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long, since neither of the first two of his conditions would be satisfied. Activity 3.13 This is a situation where prima facie Lisa’s promise is unenforceable because Jack’s work is ‘past consideration’. Does the exception apply? Presumably the work was done at Lisa’s request, so the first of Lord Scarman’s conditions is satisfied. Was it anticipated by both parties that the work would be paid for? This is more difficult for Jack. If he has simply worked the extra hours on his own initiative, then his claim may well fall at this point. There would need to be some evidence that Lisa was aware that † For detailed discussion of this aspect of the case, and the differences between the reports of the case, see Luther, P. (1999) ‘Campbell, Espinasse and the sailors: text and context in the common law’ 19 Legal Studies 526. See also Harris v Watson (1791). page 260 University of London International Programmes he was working extra hours, and perhaps evidence of past practice in making ‘bonus’ payments in this type of situation. What about the third of Lord Scarman’s conditions? Would Lisa’s promise be enforceable if it had been made in advance of Jack’s doing the work? The only problem for Jack here is whether what he is doing is simply part of his normal obligations as an employee. If it is then he may fall foul of the rules about existing obligations discussed above. If, however, he is doing more than his contract of employment obliges him to do, there is no reason why the third condition would not be met. Activity 3.14 There are two main reasons. First, if taken at face value, the principle seems to deny the need for consideration altogether. As we shall see, however, later cases have clarified that promissory estoppel only applies in a limited range of situations. Secondly, although Denning purported to be merely building on the concept of ‘waiver’, and Hughes v Metropolitan Railway (1877) in particular, that concept had never been applied to the part payment of debts (which was effectively the situation in High Trees House). Prior to that it had always been thought that Foakes v Beer (which came after Hughes, and did not even refer to it) precluded the extension of the concept in this way. Activity 3.15 It is true that the broader view of consideration is likely to reduce the need to use promissory estoppel – though it is still not possible to be certain how far the Williams v Roffey development will be taken. The area where promissory estoppel will certainly still be required is, however, where the modification of a contract involves the promisor remitting part of a debt (as in High Trees House, in relation to the rent). As made clear by Re Selectmove, Williams v Roffey has not affected the rule in Foakes v Beer. Where a contractual modification is of this kind, therefore, it will be necessary for the promisee to provide consideration, or establish a promissory estoppel, in order to be able to enforce the promise. Chapter 4 Activity 4.1 To answer this question you need to consider the essential nature of your agreements. Activity 4.2 In Simpkins v Pays, the judge finds that there was a ‘mutuality in the agreement’ between the parties. The women entered the contest together in the expectation that, should they win, the winnings would be shared amongst them. This seems to be sufficient to establish an intention to create legal relations. In contrast, in Coward v MIB, the Court of Appeal regards the lift to work as a much more irregular occurrence: it might happen or it might not. Consequently, the agreement was regarded as too informal to demonstrate an intention to create legal relations. Activity 4.3 The leading cases which deal with agreements in the context of a family are Balfour v Balfour and Jones v Padavatton. You need to do three things here. First, you need to consider what criteria the court established in these cases to determine whether or not an intention to create legal relations is established. Second, you need to apply these criteria to the facts given. Third, you need to provide an outcome to your problem. Activity 4.4 You need to apply the same process as that set out in relation to Activity 4.3. The purpose of giving this example is for you to contrast it with the example in Activity 4.3. Applying the criteria set out above, this instance is much less likely to give rise to a contract. The requisite intention is most likely lacking at the inception of the agreement. The reason for this is that the promises from both A and B are directed Contract law Feedback to activities at the care of their children – financially and physically. This strikes at the very core of the family and, without strong evidence to the contrary, is an arrangement which is unlikely to give rise to the necessary intention. Activity 4.5 There are many reasons why a commercial party might not want an agreement to be an enforceable contract. The parties may be negotiating and wish to finalise their agreement at a later date. Or a party may wish to indicate what their present intention is, without committing themselves to a particular course of action. A representor’s statement of present intention is not as valuable to a representee as a promisor’s binding commitment to future action. This was explicitly recognised in Kleinwort Benson v Malaysia Mining (1989) where the rate of interest charged for a loan to a subsidiary company was increased when the parent company, in respect of the loan to its subsidiary, offered the creditor bank a ‘comfort letter’ instead of the contractual guarantee originally proposed. Activity 4.6 In some circumstances, particularly where the parties have relied upon an agreement, courts will more readily imply or infer a term or find that the essential terms of a contract have been concluded. This can be seen in the decisions in Hillas v Arcos (1932) and RTS Flexible Systems Ltd v Molkerei Alois Muller Gmbh & Co (2010). In both cases the agreement had been relied upon and the court was able to infer the intention of the parties based upon the terms in their agreement and the usage in the trade or partial performance. It may be that the agreement provides a mechanism, or machinery, to establish the term. In such a situation, there is certainty of terms. Thus, if interest on a loan is to be set at 1 per cent above the Bank of England’s base rate on a certain date, then this is a certain term. It cannot be stated at the outset of the contract what the interest rate is, but certainty of terms exists because, on the relevant date, the interest rate can be determined by an agreed mechanism. There is a difference between a term which is meaningless and a term which has yet to be agreed. Where the term is meaningless, it can be ignored, leaving the contract as a whole enforceable. See Nicolene Ltd v Simmonds (1953). In this case, it is likely that a court will either imply that the size of the shirt is your size or, alternatively, find that this term is meaningless. Activity 4.7 In Hillas, the agreement had already been relied upon by the parties. In addition, the wording of the agreement made it clear that the parties intended to make, and believed that they had made, a concluded bargain. Related to this is that in Scammell’s case, the uncertainty surrounded the nature of another agreement, the hire purchase agreement, which had to be entered into. It was not possible to ascertain or imply the terms of this agreement in the way that the courts could ascertain the meaning of the term in Hillas’s case. The most convincing reason for distinguishing these cases is likely that in Hillas’s case the agreement had been relied upon; this indicates that there was sufficient certainty present to perform the agreement. Activity 4.8 In this instance you need to determine whether you have an agreement to agree – that is to say you would like to buy bread and he would like to sell bread – but this may not be a contract. Are all of the terms necessary for a contract to be present? In this case, it is not certain when the bread is to be delivered. That is to say, when will the bread delivery start – right away, next week or next month? A court may be able to imply a term that the delivery will begin in the week the order is placed. A court will, however, have more trouble in establishing how frequently the bread is to be delivered. The court will not want to write the terms of the contract between you and your milkman. page 261 page 262 University of London International Programmes Activity 4.9 In this instance, you do not have to buy the house. The offer was accepted ‘subject to contract’. There has been no contract to purchase and there is, therefore, no obligation upon you to purchase. Only in the most exceptional cases will courts displace the inference that arises from the use of these or equivalent words that the parties did not at that time intend a binding contract to come into existence (RTS Flexible Systems Ltd v Molkerei Alois Muller Gmbh & Co (2010)). Activity 4.10 It is impossible to compile an exhaustive list of essential terms because what is essential will depend upon the particular case. The following are suggested by way of guidance: (a) the identity of the parties involved; (b) price or a mechanism by which price can be determined; (c) the time at which the contract is to be performed. Of these, price is the most important – probably because a bargain is the essence of a contract. Activity 4.11 You will need to come back to this area after you have reviewed the section on implied terms (Chapter 5, Section 5.2). Courts will imply terms to give a contract efficacy; that is to say, to make it work. In some instances this can be done because legislation allows it to be done (see, for example, s.8 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979). In other cases, it can be done because the parties are able to determine a mechanism established by the parties within the contract. In other instances, the contract has been executed, that is to say, the contract has been performed. See, for example, Foley v Classique Coaches Ltd (1934). Chapter 5 Activity 5.1 A purchaser will typically rely upon a seller where she has great experience of, or expertise in, a particular area: see Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon. A purchaser is also likely to rely upon a seller where the seller has knowledge of matters that it is highly unlikely the purchaser would. A seller of a car, for example, is much more likely to know how the car has been driven than the purchaser. Something to bear in mind in considering a purchaser’s reliance upon the seller is that the purchaser may be protected by legislation – particularly if the purchaser is a consumer. See, for example, the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 and the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999. Activity 5.2 Lord Denning uses the term ‘innocent of fault’ in the making of a statement as an aid to the determination of whether to impose contractual liability for the statement. The process he engages in is to determine whether the maker of the statement should have, or could have, known more about the statement. In Dick Bentley Productions v Harold Smith (Motors) (1947), the defendants could have checked the accuracy of their statement rather than simply relying upon what was obvious. Their fault becomes even more glaring because the circumstances are such that a purchaser would assume that they had checked the accuracy of the statement. ‘Fault’, however, means something in the nature of negligence rather than fraud or deception. For this reason, an inquiry into fault as such is misleading. It might be more productive to consider whether there is reliance upon the statement and the maker of the statement has assumed responsibility for the accuracy of the statement. What this examination of fault does reveal is the process by which the judges are apportioning liability when the reasonable expectations of the parties are not met. The party who is at ‘fault’ will bear the responsibility for the failure. Contract law Feedback to activities Activity 5.3 The following factors suggest that the statement would be a term: uu Between a private buyer and a private seller one would expect the seller who has had possession of the goods and associated document for some time to have greater skill and knowledge in relation to its age and model year (Dick Bentley v Harold Smith Motors (1965) cf Oscar Chess Ltd v Williams (1967)). uu A statement as to a car’s age goes directly to its value and so is important. Applying Bannerman v White this would suggest it was a term. uu It is likely that the buyer clearly relied upon the seller thereby also suggesting it was a term. All three factors point to the conclusion that the statement as to the car’s age would be regarded as a term. These are the facts of Beale v Taylor (1967) where the court reached the same conclusion in respect of the car which was an example of what has become known as a ‘cut and shut job’ where the front of a car that has had a rear end collision is welded to the back of a car that has suffered a front end crash. Half the car was in fact a 1961 Triumph Herald but the other half was not! Activity 5.4 In practice, the parol evidence rule amounts to no more than a rebuttable presumption that the written contract is the whole contract. The exceptions to the rule are so numerous that its status as a ‘rule’ is highly questionable. These exceptions include evidence to establish that a contract is void or voidable on the grounds of mistake, misrepresentation or fraud; to indicate an implied term or custom; or to prove the existence of a collateral agreement. Because the rule can be circumvented so easily, it is not really a rule. What is useful about the ‘rule’ is that it operates as a guide that the written terms of the contract are, at a minimum, the starting point for the determination of the contract’s terms. When the Law Commission in a Working Paper (No 76, 1976) examined the parol evidence rule they pointed out that one exception to the rule is wider than the rule itself, thereby negating it. The exception established in Allen v Pink (1838) was that a party can rely upon parol evidence where the written document does not record the whole of the agreement. However, the only circumstance when a party would ever want to rely upon parol evidence would be where the written document does not record the whole of the agreement, thus the exception has consumed the rule! Although the Law Commission said this reduced the rule to ‘no more than a circular statement’ in their full report (No 154, 1980) they pulled back from their earlier recommendation that the rule be abolished. Therefore, it survives as a rebuttable presumption that the terms of any written contract should not be contradicted by other evidence (HIH Casualty and General Insurance Ltd v New Hampshire Insurance Co (2001)). Its usefulness is probably confirmed by the fact that a stronger, express version, known as ‘an entire agreement clause’ is often inserted in commercial contracts (Inntrepreneur Pub Co v East Crown Ltd (2000) and Axa Sun Life Services v Campbell Martin (2011)). Activity 5.5 The main reason that this variety of implication is rejected is undoubtedly because, if terms were implied into contracts on the basis that it was reasonable to do so, the contract would, inexorably, become what the judges thought was a reasonable contract. In these circumstances, the courts are not so much interpreting the contract as creating the contract. This is a role they have consistently refused. In addition, it may often become difficult to determine what term is reasonable in the circumstances of the case. Activity 5.6 The answer to this question depends upon whether or not a term can be implied by operation of the common law. It may be possible to establish that the commercial practice in such a situation requires B to supply the gear system. A court would require convincing evidence of such an invariable practice and this may not exist. A second page 263 page 264 University of London International Programmes argument rests upon necessity – that the parties, by necessity, intended such a term to be within their contract: see MacKinnon LJ’s officious bystander. A possible weakness in such an argument is that it may be that while B is the only manufacturer of such a gearing system, B may not be the only supplier of such a system. If it can be obtained elsewhere, there may be no necessity to imply the term. Activity 5.7 The unseaworthiness of the vessel was not considered a sufficiently serious breach of an innominate term in Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd (1962) as to justify terminating the contract because the delay caused by the breakdown and the necessary repairs were not so great as to remove the commercial purpose of the charterparty. The seaworthiness of the vessel was thus not a condition of the contract. The term did not meet the test set out by Diplock LJ in that case: The test of whether an event has this effect or not has been stated in a number of metaphors all of which I think amount to the same thing: does the occurrence of the event deprive the party who has further undertakings still to perform of substantially the whole benefit which it was the intention of the parties as expressed in the contract that he should obtain as the consideration for performing those undertakings? In the case before him, there was not a substantial deprivation of benefit. In comparison, clauses dealing with time tend to be conditions – time is a particularly important factor in commercial contracts. It is often expressed that ‘time is of the essence’. See, for example, Bunge Corporation v Tradax SA (1981). Activity 5.8 The practical consequences for the owner if the time charterer is late in redelivering the ship is that he will probably be in breach of another contract with another party for the delivery of the ship. These consequences can be quite severe. Activity 5.9 The difficulty that Schuler faced was that while clause 7(b) of the agreement with Wickman stipulated that it was a ‘condition of this agreement’ that the representatives of Wickman would visit the motor manufacturers at least weekly, the court found that the parties had used the word ‘condition’ in the sense of ‘term’. Consequently, the contract could not be terminated when the weekly visits were not made on a few occasions. What Schuler could have done to ensure that the visits were genuinely a ‘condition’ of the contract (breach of which entitled Schuler to terminate the contract) was to clearly indicate in the contract that a breach of this obligation entitled Schuler to terminate the contract. See Lombard North Central plc v Butterworth (1987) where Mustill LJ discusses the ability of a party to establish as a condition a matter which, at common law, would not be considered a condition in the sense of allowing the injured party to terminate the contract because the obligation stipulated was of a minor nature. It is this point which marks the difference between the majority in Schuler (as expressed in the speech of Lord Reid) and the dissent of Lord Wilberforce. Activity 5.10 The critical difference between the decision in Schuler AG v Wickman Machine Tools Sales Ltd (1974) and Lombard North Central plc v Butterworth (1987) is that in the latter case, the contract clearly stipulated that the punctual payment was of the essence of the agreement (clause 2(a)) and that failure to make punctual payments entitled the plaintiffs to terminate the agreement (clause 5). Chapter 6 Activity 6.1 Your list might include the fact that such a clause may be unexpected; that parties should not be able to escape from obligations freely undertaken; and that consumers and other parties with weak bargaining power may be forced to accept unfair clauses. Contract law Feedback to activities All these reasons relate to the protection of parties from the abuse of a position of power by the other contracting party. As to the reasons why such exclusion might be desirable, if the parties are of equal bargaining power, a clause of this kind may simply indicate that they have thought about where the risks under the contract should lie and have made provision for that by means of an exclusion clause. If, for example, in a construction contract the owner of the land has undertaken to insure against the risk of damage to surrounding property from the work, it will be perfectly reasonable for the developer to exclude its own liability for such damage. Activity 6.2 The question is whether Marika has been given ‘reasonable notice’ of this clause. In Thompson v LMS Rly (1930), it was held that reasonable notice had been given, even though the claimant was illiterate and could not read the clause. This would suggest that, if Upton Castle have acted reasonably as regards adult entrants who understand English, then the clause will be incorporated. The answer to this question may also depend on whether the ticket is a ‘contractual document’ or a mere receipt (see Chapelton v Barry UDC (1940)). Note that if the clause is incorporated, it will need to be considered in the light of the Consumer Rights Act 2015. Activity 6.3 Generally the signing of a contract is sufficient to make the signer bound by the terms contained in it (see L’Estrange v Graucob (1934)). This would suggest that Angela is bound by the clause. The only exceptions to this are, first, where the signer can claim that the contract was a fundamentally different document from what it was thought to be – that is the plea of ‘non est factum’ dealt with in Chapter 8, Section 8.3.3. This has no application to Angela. Secondly, there is an exception where the principle applied in Curtis v Chemical Cleaning and Dyeing Co Ltd (1951) operates. Here an employee innocently misrepresented to a customer the effect of an exclusion clause in a dry-cleaning contract. It was held that the customer, who had signed the contract, could nevertheless recover for losses which fell within the actual scope of the clause, because the company was bound by their employee’s misrepresentation. Here, therefore, the answer would be likely to be that a court would hold that the clause was part of Angela’s contract, but only to the extent that it excluded liability in the situation specified by Magna’s employee. Activity 6.4 The question arises here whether David’s previous dealings (24 times in two years) have been ‘regular and consistent’. The frequency and duration of the dealings is less than in Kendall (Henry) & Sons v Lillico (William) & Sons Ltd (1969) but more than in Hollier v Rambler Motors (1972) so a firm conclusion is hard to reach. Questions are often posed which ‘sit between’ decided cases like this and your answer requires interpolation (i.e. you must decide if the hypothetical you are considering is closer to one of the decisions you refer to than the other). It is perhaps more likely here that the course of dealing would be held to resemble that in Kendall rather than that in Hollier. If David was delivering produce from his farm it is more likely that the clause would be binding on him as under British Crane Hire v Ipswich Plant Hire Ltd (1975) a lesser frequency of dealing is regarded as sufficient in so called B2B contracts Activity 6.5 a. The breach involved was not a breach of a fundamental term. The fire might have been put out quickly, in which case no serious damage would have been done. The case is similar to Harbutt’s Plasticine, in that it was the consequences of the breach which made it ‘fundamental’, rather than the nature of the obligation broken. b. As to the explanation for the parties’ agreement to this wide clause, you should have noticed that Lord Wilberforce pointed out that the rate of payment for each visit worked out at 26 pence. Photo Production were therefore getting a very cheap deal. As Lord Wilberforce concluded: ‘In these circumstances nobody could consider it unreasonable, that as between these two equal parties the risk assumed by Securicor should be a modest one, and that [Photo Production] should carry the substantial risk of damage or destruction.’ page 265 page 266 University of London International Programmes Activity 6.6 The only question here is whether the negotiation which has taken place means that the contract is not to be regarded as being on B’s ‘written standard terms’. The question is one of fact and degree, but the case of St Albans City District Council v International Computers Ltd (1996) indicates that prior negotiation will not in itself prevent s.3 from applying. Assuming that any exclusion clause in the contract between A and B is part of B’s ‘standard package’, then s.3 will apply. Activity 6.7 The fact that the contract is made by an exchange of letters suggests that it is not on ‘written standard terms’. If that is so, s.3 cannot apply. Activity 6.8 The following questions must be asked. If the answer is negative you should move on to the next question. Your written answer to a problem might include such a negative conclusion but you should be careful to do so briefly. There is a thin line between stating a negative conclusion and including irrelevant material in an answer. 1. First ignore the exemption clause! Consider what liability would arise if there were no exemption clause. If there are other express contract terms these will need to be interpreted. Do not forget the possible statutory implied terms or obligations. Be careful to consider all possible liabilities (e.g. breach of an express term or terms, breach of any implied terms or obligations and possible liability for misrepresentation). If there would be liability then: 2. Does the exemption clause form part of the contract? If it is in a signed document consider the signature rule. If it is an unsigned document or notice consider the preconditions of incorporation. If yes then: 3. Does the clause cover the breach or breaches that have occurred? This will involve the application of the principles of contractual interpretation of exclusion clauses including the contra proferentem rule and the doctrine of fundamental breach. If the clause or clauses do otherwise cover the breaches that have occurred: 4. Is the contract a B2B or B2C contract? 5. The previous answer will direct you to the correct statutory regime applicable to exclusion clauses contained in that type of contract, either: B2C CRA 2015 B2B UCTA 1977 Apply the relevant statutory provisions. Activity 6.9 The way this question is put ‘saves’ you from stage 1 and 2 above because you are told that there has been a breach of contract and from the facts we can assume that the clause is incorporated and that its wording covers the breach. It clearly falls within either s.2 or s.3 of the UCTA. The question is, is it reasonable? The test is whether it was a fair and reasonable clause to include in the contract at the time it was made – not whether it is fair and reasonable to allow Xerxes to rely on it in the circumstances which have occurred (see Stewart Gill v Horatio Meyer (1992)). If the latter was the test to be applied then, in the light of the apparently minor nature of the breach in relation to the contract as a whole, and the fact that it was not caused by negligence, it might well have been reasonable to allow exclusion. Looking at the potential scope of the clause at the time of the contract, however, it becomes much less reasonable. The burden of proof is on Xerxes to prove that it is reasonable (s.11(5) UCTA). A court would have to make a judgment taking into account all the circumstances. The breadth of the clause would suggest that it is likely to be found to be unreasonable. Xerxes would not, therefore, be able to rely on it. Contract law Feedback to activities Chapter 7 Activity 7.1 In practice, the supplier will have difficulty in establishing whether or not young Inman had sufficient clothing. It is perhaps worth noting from the decision that Buckley LJ describes the clothing as being ‘clothing of an extravagant and ridiculous style having regard to the position of the boy’. This should have been an indication that these clothes were not necessaries. In addition, it is also worth noting, on the facts of the case, that the plaintiff, a Savile Row tailor, sent his agent to call upon Inman when he was studying at Cambridge University. In the circumstances, he might have been able to note whether or not he had sufficient waistcoats. In this case the law does seem to be overly protective of young Inman. He must have known what he was doing when he ordered the clothes. He is reported as having been ‘spending freely’ and must have been aware of the debts he was incurring. Activity 7.2 The decision would not apply to an executory contract for necessary goods because s.3 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 provides that it is only where the necessaries ‘are sold and delivered to a minor’ that a reasonable price must be paid for the goods. If the contract was an executory contract, the goods would not have been delivered. In Roberts v Gray (1913), the contract had been partly executed and the infant had received some benefit from it. Consequently, the remainder of the contract was also binding upon him. Activity 7.3 The traditional explanation is to be found in Ex parte Jones (1881). The explanation is that ‘the law will not suffer him to trade, which may be his undoing’. The law is concerned that the minor may lose all his capital in trade. In contrast, it is perceived that this risk will not occur in learning a profession. In practice, it may be difficult to distinguish in some circumstances between whether the minor is trading or exercising a profession. Activity 7.4 The minor will not be able to recover his money unless he can establish that there has been a total failure of consideration (see Steinberg v Scala (Leeds) Ltd (1923)). In general terms the incapacity of a minor will act as a defence to a claim by the other party who seeks to enforce the contract rather than as the basis of a claim by the minor for the restitution of the benefit he has conferred upon the other party. Chapter 8 Activity 8.1 You must examine the underlying rationale for the decision in order to answer this question. In this case, the trial judge stated that ‘a contract cannot arise when the person seeking to enforce it has by his own negligence or by that of those for whom he is responsible caused, or contributed to cause, the mistake’. In the circumstances of Scriven, the seller was said to have contributed to the cause of the mistake. If the buyers had not contributed to the mistake, the contract would not be void and they should recover damages for non-delivery on the basis of the contract. See also the discussion in Chapter 2, Section 2.1.1. Activity 8.2 If the seller warranted that the good existed, then the warranty forms a part of the contract of sale (or a separate, collateral contract). In this case, the seller has assumed page 267 page 268 University of London International Programmes the risk that the good exists. If it does not, the seller is in breach of contract. This is one explanation of McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission (1951) (i.e. the Commission had warranted the existence of the vessel to be salvaged). Since it did not exist, the Commission had breached their contract. Activity 8.3 Yes, it is possible to regard Couturier v Hastie (1856) as a case where the seller provided no consideration. A strong argument is made by the High Court of Australia in McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission (1951) to this effect. The High Court states that the question of mistake as to the supposed existence of the subject matter of the contract never arose in Couturier v Hastie. This was only a subsequent and incorrect interpretation of the case; which, unfortunately, was codified in the Sale of Goods Act 1893. The real ground for the decision is that there was a failure of consideration and the purchaser was not bound to pay the purchase price. The purchaser would receive nothing in exchange for the purchase price. Had he paid the purchase price, he could have sued for the recovery of the money on the ground that this was money he had received. The High Court also stated that such an interpretation is supported by the observations of Lord Atkin in Bell v Lever Bros Ltd (1931). What is of central importance is the construction of the contract. If the vendor had warranted or promised that the goods were in existence at the time of the contract, then the vendor would be in breach of contract if they were not. This was a risk that the vendor had assumed. Activity 8.4 It is possible to view these as cases where the putative purchaser did not actually consent to the contract. The consent was defective in that it was based upon a mistaken assumption – that the purchaser needed to contract to acquire the right in question. However, it is also possible to see these as cases of impossibility – in which case, how would the consent of the parties be relevant? These are cases of initial impossibility because it is never possible for an owner to purchase that which he already owns. The result in the case may be explained on either basis. For a further explanation see Section 8.5.2. Activity 8.5 The most common instance of this form of impossibility is in the case of a res sua – where one party attempts to purchase that which he already owns. The case of Cooper v Phibbs is usually given as support for this proposition. Another instance occurs when the parties contract on the basis that something will be done – when in fact, that something is incapable of performance. See, for example, Sheikh Brothers v Ochsner. Yet another instance can be found in the situation where the commercial purpose of the contract can no longer be fulfilled – see Griffith v Brymer. Activity 8.6 On the one hand, performance of the contract is still possible – the hirer could still take the room on the appointed day. On the other hand, the entire purpose of the contract was for the hirer to hire a room with a view (of the coronation procession). Once the possibility of this view has gone, the commercial possibility of the contract has also disappeared. The case can be compared to Herne Bay Steamboat Co v Hutton (1903). Here the Court found that some of the commercial possibilities of the contract remained and it had not been frustrated. Activity 8.7 Steyn J (as he then was) recommended the following approach to cases of common mistake. It must be determined whether the contract, by express or implied condition, provides who bears the risk of the relevant mistake for only when the contract is silent on this point can mistake as a legal doctrine be considered. Where common law mistake has been pleaded, the court must then consider this claim and if the contract is found to be void, mistake in equity can not be considered. Contract law Feedback to activities page 269 If the contract is valid at law, it may still have to be considered as to whether or not there is a mistake in equity. (Note You should note the effect of The Great Peace upon this last point because Lord Phillips MR found that there was no such separate equitable doctrine of common mistake.) With this approach in place, Steyn J then set out the following propositions. 1. It is imperative that the law ought to uphold rather than destroy apparent contracts. 2. Common law rules on mistake are designed to cope with the impact of sudden and unexpected circumstances upon apparent contracts. 3. For a mistake to attract legal consequences it must be substantially shared by both parties at the time the contract is made. 4. The mistake must render the subject matter of the contract essentially and radically different from the subject matter which the parties believed to exist. 5. A party cannot be allowed to rely on a common mistake where the mistake consists of a belief which is entertained by him without any reasonable grounds for such belief. Activity 8.8 You need to approach this question by asking yourself if there is a contract between Ace and Crafty (Blob acts as an employee of Ace). Ace alone, through Blob, operates under a mistake. There is nothing in the problem to indicate that Crafty is mistaken about the worth of the card. If Crafty is also mistaken as to the card, then the parties share a common mistake as to a quality of the subject matter of the contract and the House of Lords’ decision in Bell v Lever Bros Ltd (1931) applies. On the prevailing interpretation of Bell, that means that it is unlikely that the court will find that the contract is void. However, if only Ace is mistaken, the contract is likely to be set aside as void. This is because Crafty is aware of Ace’s mistake and he ‘snaps’ at the offer. His conduct is unconscionable or inequitable in the sense that he enters the shop solely to take advantage of what he knows is a mistaken offer. Hartog v Colin and Shields (1939) applies to this case – there the price had always been negotiated per piece and not per pound (which resulted in a lower overall cost). What Crafty will argue in this case is that there have been no prior dealings between the parties in this instance – Ace will need to establish that the price of $20 is so inconsistent with the price offered in the trade that Crafty has indeed ‘snapped’ at the mistaken offer. (You should be aware of the possibility, without exploring it in any depth, that s.20 of the Consumer Protection Act makes it an offence for a person acting in the course of business to give a misleading indication as to price to consumers.) Activity 8.9 In a situation such as this, it is best to approach each subdivision of the question individually. You may find it useful to compare the subdivision you are discussing to another subdivision to express why one subdivision reaches a different outcome from another. a. The statement is certainly a misrepresentation (see Chapter 9), assuming it is a statement of fact, not opinion. If the statement is not a misrepresentation, it may be incorporated into the contract or form a collateral contract (a contract which is separate from the contract of sale): see Heilbut, Symons & Co v Buckleton (1913). If it is a contractual warranty, then A is liable to B for a breach of contract. If it is a misrepresentation, then A may be liable to B for damages under the Misrepresentation Act 1967, or for a fraudulent misrepresentation (Derry v Peek) or for a negligent misrepresentation (Hedley Byrne v Heller). Regardless of the type of misrepresentation, A should be able to have the contract rescinded if the misrepresentation is actionable. † b. This may be actionable under s.2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967 – does A have reasonable grounds at the time of making the statement for believing that the picture is a Carr and does he have these grounds up to the time the contract is † The elements of an actionable misrepresentation can be found in Chapter 9 of this module guide. page 270 University of London International Programmes entered into? (See Howard Marine v Ogden.) If A does not have these grounds, then he is liable to B under s.2(1). Note in this connection that A is a dealer. If A does have these grounds, then the parties are labouring under a mistake. The problem here is that this is a mistake as to a quality (who painted the painting) of the subject matter (the painting). You need to apply the decision in Bell v Lever Bros and this rarely results in an operative mistake. The principle established by Lord Atkin is: ‘Mistake as to quality of the thing contracted for raises more difficult questions. In such a case mistake will not affect assent unless it is the mistake of both parties, and is to the existence of some quality which makes the thing without the quality essentially different from the thing as it was believed to be.’ Applying this principle, it will be difficult to establish the mistake as operative. Does the mistake as to the quality ‘make the thing without the quality essentially different from the thing as it was believed to be’? It is still the same painting. It was displayed by the vendor to the purchaser – they identified it by the sight of the painting before them. The identity of the artist is simply a quality of the painting. On the other hand, there may be limited scope to assert that this quality is so important that it is the feature by which the painting is identified. (Certainly conditions in the modern art market, where buyers are more concerned with the creator of art rather than the art itself, would support such an argument.) Unless the artist can be identified as critical to this contract, the contract will not be set aside as void. c. In this instance both parties may be mistaken, but their mistake is not shared. Therefore, mutual mistake – and Bell v Lever Bros – does not apply. Is there a lack of agreement? On the one hand, they do seem to be dealing in different things. On the other hand, the painting is before them – this situation is unlike that in Raffles v Wichelhaus. The offer is to sell the painting before them; the acceptance is to buy the painting before them. The parties are not at cross purposes. What is really going on is that B thinks he is getting the better of A – and courts will not intervene to relieve a party from a bad bargain or for not receiving what he gambled upon receiving. This is, in other words, a case of caveat emptor. d. In this instance, mere knowledge on the part of A that B thinks that the painting is an original is not sufficient to render the contract void. A has to know of the mistake of B and know that it is a mistake as to the nature of the promise made by A. The principle is set out by Hannen J in Smith v Hughes: ‘In order to relieve the defendant it was necessary that the jury should find not merely that the plaintiff believed the defendant to believe that he was buying old oats, but that he believed the defendant to believe that he, the plaintiff, was contracting to sell old oats.’ There is nothing to indicate that B’s mistake is as to the nature of the promise made by A. e. In this variant, the mistake of B does seem to be with respect to the nature of the promise made by A. A knows of B’s mistake. Accordingly, the principle in Smith v Hughes (above) applies and the contract is void. Activity 8.10 Lord Nicholls and Lord Millet found commercial sense in allocating the risk of fraud to the party who chose to part with his goods on credit, rather than a third party who purchases from the rogue. In addition, technological changes in the methods of communication may render the distinction between contracts formed face-to-face and contracts formed at a distance untenable. Activity 8.11 Property in the goods will be P’s. When N supplied the goods on credit they took a commercial risk and they must bear the cost of this risk. Identity was not material to the formation of this contract because there was, in fact, no company by the name of Greenhill & Co. Because of this, this situation is distinguishable from Cundy v Lindsay (1878), where there was a reputable firm by the same name and the mistaken party thought that he was contracting with the reputable firm. See the decision in King’s Norton Metal v Edridge, Merrett (1897). Contract law Feedback to activities Activity 8.12 If the person did exist, the fact that their death was unknown to the parties should not be relevant. Applying the principle in Cundy v Lindsay, ‘there was no consensus of mind which could lead to any agreement or any contract whatsoever’ between the rogue and the innocent party. The innocent party is attempting to contract with the third party; in the absence of consensus, the contract is void. Activity 8.13 It does matter if the rogue assumes the identity of a fictitious party or a real party – but only if the identity is material to the contract. This will generally mean that the mistaken party is mistaken as to identity from the outset of the process of negotiation. If the identity only becomes relevant at the point of payment (will credit be extended or a cheque accepted) then identity will not be viewed as material and the contract will be voidable for misrepresentation. Where identity is relevant from the outset of negotiations, it does matter if the identity assumed is of a real or a fictitious person. In Cundy v Lindsay, the House of Lords found that where the rogue pretended to be a real person, the contract was void. The mistaken party had meant to deal with the reputable firm; with the rogue, there was no consensus and thus no contract. In King’s Norton Metal v Edridge, Merritt & Co (1897), in contrast, there has been no firm by the name given and there was a contract with the rogue. Activity 8.14 This mistake is probably not sufficient to avoid the contract at common law. It is a mistake as to a quality of the subject matter of the contract – but it is not sufficiently fundamental within the test established by Lord Atkin in Bell v Lever Bros (1931). The contract thus stands at law and must be considered in equity. Following the decision in The Great Peace, there is no scope for a doctrine of mistake in equity. Accordingly, Victor is bound. However, the argument can be made that the behaviour of Peter is objectionable and that he is seeking to take advantage of Victor. Peter, as an art expert, must be aware that Victor has seriously undervalued the painting and is unaware of its worth. If Victor refuses to deliver the painting, it is unlikely that a court of equity will order specific performance of the contract. Because this case involves an order for specific performance, it is possible to argue that the decision in The Great Peace (which involved the question of rescinding the contract) is not applicable to these circumstances. There is an older line of authorities dealing with the refusal to order specific performance on grounds of mistake. Nonetheless, Victor would be liable to pay damages to Peter if Peter’s claim for specific performance fails. Chapter 9 Activity 9.1 a. X’s statement appears to be an expression of opinion as to the likely future life of the tyres. The only possibility of this being a misrepresentation is, then, if X is aware that the wear on the tyres is worse than he is suggesting. His statement will then become a misrepresentation as to his state of mind, on the Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1855) principle. b. The phrase ‘trained to the highest standards’ is too vague to be treated as a representation. The statement about the length of supervised training is a statement of fact, however. Since this is untrue, it will amount to a misrepresentation. The remedies available will depend on whether the statement induced a contract, and whether the salesman was aware, or should have been aware, that the statement was untrue (see Section 9.2). c. Statements in advertising are generally treated as ‘mere puffs’, not giving rise to any legal liability. It is unlikely, therefore, that the statement on the poster would be treated as a misrepresentation, even if the statement that the CD was the ‘best’ could be treated as ‘fact’ rather than ‘opinion’. There is also the requirement that the statement is made by one contracting party to the other. Could the statement on the poster be said to be made by the shop selling the CD, rather than the company which produced it? page 271 page 272 University of London International Programmes Activity 9.2 Keith’s statement to Alpha Sports is a statement of intention. Such statements cannot usually be treated as misrepresentations. The exception is where there is evidence that the person making the statement did not genuinely have the relevant intention (as in Edgington v Fitzmaurice). In the absence of evidence that Keith had already decided to retire when he made the statement to Alpha’s representative, Alpha will not be able to take action against Keith for misrepresentation. In the alternative situation, it seems that Keith has changed his mind about his intentions between speaking to Alpha, and signing the contract. In general, keeping silent does not amount to a misrepresentation. But here Keith’s change of mind means that his statement about his intentions made to Alpha’s representative is no longer true. There is no direct authority in relation to changed intentions (as opposed to changed circumstances), but by analogy with With v O’Flanagan (1936) and Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV [2000] EWCA Civ 15, it would seem that Alpha can argue in this situation that Keith’s failure to tell them of his change of mind does constitute a misrepresentation. Activity 9.3 The main other use of the term ‘rescission’ is in relation to the power of the innocent party to terminate a contract for breach. This is discussed further in Chapter 14. The chief difference is said to be that termination for breach does not aim to undo the contract, but simply to bring it to an end for the future. In other words it is only obligations which are not yet due for performance that are ‘rescinded’ in this situation. The distinction is not clear cut, however, in that in some cases termination for breach may lead to property being handed back. If, for example, a sale of goods contract is terminated because the goods are of unsatisfactory quality, the consequence may be that the goods are returned to the seller and the purchase price is returned to the buyer. For the sake of clarity it is probably best to reserve the term ‘rescission’ for misrepresentation and to refer to ‘termination’ or ‘repudiation’ when breach is being discussed. Activity 9.4 You must remember that rescission of a contract is available even if the misrepresentation is entirely innocent. It is also a powerful remedy which, in undoing the contract, can have serious consequences. Taking these two factors together, the courts are probably right to limit the scope for rescission, leaving the situations where the misrepresentation was not innocent to be dealt with by damages under the tort of deceit (as discussed in Section 9.2.2). The gap that was left, however, was the situation where the misrepresentation was negligent. If the right to rescind was lost, the victim of a negligent misrepresentation was left without a remedy. This gap has now been filled as far as damages are concerned by both the common law and the Misrepresentation Act 1967 (again, see Section 9.2.2). It is arguable that now that the law has recognised a range of categories of misrepresentation, more flexibility should be employed in deciding whether to allow rescission. In the most recent examination of this area of law, Salt v Stratstone Specialist Ltd [2015] EWCA Civ 745, which repays reading in full the Court of Appeal, addressed various questions about the availability of remedies for misrepresentation in a holistic way that took account of the availability of remedies for breach of contract arising from the same set of facts (see especially the judgment of Roth LJ). Activity 9.5 The Court of Appeal thought that if the misrepresentation had not been made then the plaintiffs would still have bought the shares, but at a lower price. They would therefore still have suffered a loss on the resale of the shares, but a smaller one, based on the difference between the actual purchase price and the price they would have paid without the misrepresentation. The House of Lords thought that if the misrepresentation had not been made then the plaintiffs would not have bought the shares at all. They were therefore entitled to the full loss suffered on the transaction. It was irrelevant that the dramatic reduction in the value of the shares Contract law Feedback to activities was unforeseeable at the time of the initial contract. Since the misrepresentation was fraudulent, the principle in Doye v Olby meant that all direct losses were recoverable, without any consideration of ‘remoteness’. Activity 9.6 Where the fraud involves a misrepresentation by a party to a contract which has induced the other party to enter into an agreement, there seems little point in using the tort of deceit. The Misrepresentation Act 1967 has a much lighter burden of proof for the claimant, and the remedies available are just as extensive as for deceit (on the basis of Royscot v Rogerson). Do not forget, however, that the tort of deceit does not only apply to misrepresentations inducing a contract; for fraud outside the contractual area the tort of deceit may well still be a useful basis for a claim. Activity 9.7 McKendrick’s argument supports the view taken by other academic commentators, and in particular Hooley (1991), that the Court of Appeal’s decision in Royscot v Rogerson involved a misinterpretation of s.2(1) of the 1967 Act. Although the section uses the analogy of fraud, there is nothing in it which compels the court to apply the same approach to damages as is used in the tort of deceit. The current approach means that the law fails to make any distinction between the defendant who cannot prove that he or she took reasonable care and the defendant who is proved to have acted fraudulently. McKendrick suggests that the different level of culpability between the defendants would justify (or even require) a difference in the level of damages which they are required to pay. (Note that considerations of ‘culpability’ have a much stronger role in the law of tort than they normally do in contract, where the loss to the claimant, rather than the fault of the defendant, is generally the dominant consideration.) Chapter 10 Activity 10.1 Shipbuilders who were building a ship demanded (as a result of currency devaluations but with no legal entitlement) that all outstanding stage payments be increased by 10 per cent. The purchaser, who had already entered a lucrative charter for the vessel to commence immediately upon delivery, protested but reluctantly agreed to the increase. After payment and delivery of the ship the purchasers sought the return of the extra sums paid, on the basis that there was no consideration provided by the shipyard in exchange for the payments and that they were in any event obtained by duress. The appropriate test for consideration at that time was that in Stilk v Myrick (1809) as the case predated Williams v Roffey Bros and Nicholls (1991). Thus, consideration for the promise to increase outstanding instalments would need an undertaking of something beyond that which was originally promised. Consideration was found in the shipyard’s promise to amend the letter of credit to cover the increased payments (effectively a bank’s promise to return to the purchaser any payments made in the event of the shipyard having financial problems). The court further held that the extra payments were obtained by economic duress. They were made as a result of the shipyard’s threatened breach of contract. The purchaser had protested but felt compelled to agree as he had no reasonable alternative. However, the payments were not ultimately returned because although there was initial economic duress, the purchaser had affirmed the contract at a time when they were free of the economic duress. Activity 10.2 In this scenario the shipyard would be threatening to do something that it was otherwise legally entitled to do. The courts have held in Progress Bulk Carriers Ltd v Tube City IMS LLC (The Cenk Kaptanoglu) (2012) that what constituted economic duress was to be considered on a fact-specific basis and that there was no requirement that page 273 page 274 University of London International Programmes an unlawful act had been committed. An illegitimate threat may combine elements of lawfulness and unlawfulness (Borrelli v Ting (2010)). Exceptionally, a threat only to do something that was otherwise lawful might constitute economic duress if it compelled its victim to submit. According to CTN Cash and Carry v Gallaher (1994) it is less likely to amount to such when the contract is between two commercial entities. According to this case it will also be relevant to know if the party making the threat acted in good faith (i.e. believed himself to be entitled to the demand he was asking for). On this basis the threat in this example – which is basically a threat to refuse future business – is unlikely to constitute economic duress. This accords with an Australian case Smith v William Charlick Ltd (1924) where a miller’s claim for reimbursement of surcharges paid to the Wheat Harvest Board failed despite the fact that they had threatened to cut off future supplies to him if they were not paid. Activity 10.3 In Pao On v Lau Yiu Long (1980), Lord Scarman set out the following criteria as indicative of the existence of duress. 1. Did the person who was allegedly coerced protest at the time? 2. Did this person have an alternative course of action open to him – such as an adequate legal remedy? 3. Was the person independently advised? 4. Did the person take steps to avoid the contract once they had entered it? Activity 10.4 Mocatta J states that, since duress renders the contract voidable, it is for the party coerced to act to set aside the contract once the pressure has been removed. The party must also have a full knowledge of all the circumstances. The court must, on an objective view, determine whether or not the party coerced has acted to affirm or not the voidable contract. This is done by his conduct: quoting an earlier decision, Mocatta J stated that the question was ‘what would his conduct indicate to a reasonable man as to his mental state?’ In the case before him, Mocatta J noted that the party had not registered a protest once the duress had been removed, that they had made the final payments without qualification and that there was a delay between making the final payment and protesting of the duress. Activity 10.5 It is by no means certain that the case would have been decided on the same basis if Kafco were aware that Atlas had mistakenly underbid the job. Two possibilities arise in such circumstances. The first is that if Kafco had ‘snapped’ up Atlas’s mistaken offer it is possible that no contract would have arisen because of this unilateral mistake (see Chapter 8, where the topic of mistaken offers is discussed). The second is that if Kafco were aware that Atlas had underbid the job the case begins to look very similar to Williams v Roffey Bros (discussed in Chapter 3). The question might then become whether, absent duress, there was consideration in the form of a practical benefit for the new contract to pay more. Activity 10.6 There are many ways of distinguishing between commercial pressures and a ‘coercion of the will’ that constitutes duress. One difference can be seen from the speech of Lord Scarman in Pao On v Lau Yiu Long. In cases of economic duress, for duress to be present, it must be shown that ‘the payment made or the contract entered into was not a voluntary act on his part’. In contrast, normal economic pressure is not normally to remove the voluntary nature of the contractor’s act. Such an explanation ignores what has, more recently, become the focus of attention in cases of duress. The focus here is upon the illegitimate acts or pressure brought by a stronger party upon a weaker party. Such a focus is present in Universe Tankships Inc of Monrovia v International Transport Workers Federation. Thus, what is critical in the separation of duress and normal commercial pressure is the use of illegitimate force. Contract law Feedback to activities Activity 10.7 Where the bank knows of the wrongdoing of the debtor, then they will be bound by the surety’s equity to avoid the transaction: Barclays Bank v O’Brien. It would be highly unusual, however, for a bank to have actual knowledge of the debtor’s wrongdoing. Generally, the bank will be bound because it has constructive notice of the surety’s right to avoid the transaction. The bank has constructive notice when it knows of facts which should put it upon inquiry. The most common fact will be that the transaction is not, on the face of it, to the financial advantage of the wife: see Barclays Bank v O’Brien (where the transaction was not, on the face of it, to the advantage of the surety) and CIBC v Pitt (where the transaction, on the face of it, appeared to be to the advantage of the surety). See Lord Nicholls’ speech at paragraphs 38–43 of Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) in which he discusses the development of form of notice. Lord Nicholls continues to consider [at paras 44 and 47–49] when a bank is put in inquiry. Activity 10.8 The presence of disadvantage strengthens the presumption that the only reason for the transaction was the wrongdoing of the stronger party. The transaction is not otherwise readily explicable on other grounds. See Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2001), paras 21–28. Activity 10.9 The most obvious difference between the two is that economic duress is a legal doctrine, whereas undue influence is an equitable doctrine. Equity operates as a matter of discretion rather than as of right. There are, however, many similarities between what is required to establish each of them. Duress, whatever form it takes, requires actual coercion or pressure (Pao On v Lau Yiu Long). Similarly, actual undue influence consists of actual pressure brought to bear upon one party by another. The similarities between the two were noted in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) by Lord Nicholls when he described actual undue influence as ‘overt acts of improper pressure or coercion such as unlawful threats’ and then commented that ‘today there is much overlap with the principle of duress as this principle has subsequently developed’. [para 8] Similarly, Lord Hobhouse in the same decision noted that the same conduct as would constitute actual undue influence might constitute the defence of duress at law [para 108]. Chapter 11 Activity 11.1 Lord Reid stated that the agency argument might be successful if: uu the contract made it clear that the stevedores were intended to receive the protection of the exemption clause uu the contract made it clear that the carrier, in addition to contracting on his own behalf, was also contracting on behalf of the stevedores uu the carrier had authority from the stevedore to enter into the contract on his behalf (or, possibly, a later ratification of the contract by the stevedores would suffice) and any difficulties about how the stevedores would provide consideration for this contract were overcome. The agency argument was not successful in the case before Lord Reid. The stevedores were not named or described in the class of people to whom the limitation of liability was to extend nor was there any evidence that the carrier was acting on their behalf. Consequently the first two criteria were not satisfied. Activity 11.2 The principal arguments in favour of privity of contract are: uu the doctrine clearly defines the ambit and enforceability of contractual obligations uu it can ensure that courts do not create a contractual obligation page 275 page 276 University of London International Programmes uu it operates in tandem with the requirement that consideration must move from the promisee and the third party has not provided any consideration uu it would not be desirable for a promisor to face actions for breach of contract from both the promisee and the third party uu if the third party could enforce the contract, this would affect the ability of the parties to vary or rescind the contract. The point here is that Lord Reid is indicating how parties can establish a collateral contract between the owner of the goods and the stevedores in order to provide the stevedores with the benefit of the exclusion clause. Because it is a separate contract, it requires consideration. The principal arguments against privity of contract are: uu it leads to commercial inconvenience uu it can operate to create great injustices uu it defeats the intentions of the parties to the contract uu it puts English contract law in an anomalous position in that the contract law of other countries does recognise third party rights uu it creates uncertainty in contractual relationships given the number of devices which exist to circumvent the application of the doctrine. Activity 11.3 The survival of privity of contract illustrates some of the limitations of the common law. Courts were hesitant to overrule the doctrine (existing contractual relationships would be upset if the doctrine was abolished) and expressed disapproval of it. Steyn LJ, in Darlington BC v Wiltshier Northern Ltd (1995) pointed out that common law courts ‘are the hostages of the arguments deployed by counsel’ – if counsel did not seek to challenge the doctrine, it was difficult for the court to do so. Legislative action was difficult to achieve, in large part because of the difficulty in finding parliamentary time to deal with the matter. Activity 11.4 The 1999 Act preserves existing exceptions to privity (subsection 7(1)) and the Law Commission, in its report on privity, ‘Privity of Contract, Contracts for the Benefit of Third Parties’ (Law Com No. 242 Cm 3329 July 1996), expressed the hope that legislation would not hamper the further judicial development of third party rights. The result is that any situation concerning privity of contract and a third party beneficiary will fall within one of four scenarios. In the first scenario, the problem will be dealt with by the 1999 Act alone. In the second scenario, the problem will be dealt with by an existing common law device and does not fall within the 1999 Act. In the third scenario, the problem can be dealt with by both the 1999 Act and an existing common law device. In the fourth scenario, the problem does not come within either the existing common law devices or the 1999 Act. Activity 11.5 There are two opposing arguments as to the future development of a ‘performance interest’. It is possible to view cases which appear to accept such a performance interest as situations where, in the absence of such recognition, there would be no effective sanction for a breach of contract. The 1999 Act, however, provides parties with the opportunity to confer a benefit on a third party. If they have chosen not to, the court can view the lack of this conferment as indication that there is no performance interest. See, for example, the approach taken in Panatown v Alfred McAlpine Construction Ltd (2000). This may, however, cause harsh results in circumstances where the parties have not, by accident, brought themselves within the ambit of the Act. In such a circumstance, the lack of a ‘performance interest’ which entitles the promisee to substantial damages allows a promisor to breach a contract with impunity. Contract law Feedback to activities Activity 11.6 The conditions were those set out by Lord Reid in Scruttons Ltd v Midland Silicones Ltd (1962) that: a. the contract made it clear that the stevedores were intended to receive the protection of the exemption clause b. the contract made it clear that the carrier, in addition to contracting on his own behalf, was also contracting on behalf of the stevedores c. the carrier had authority from the stevedore to enter into the contract on his behalf (or, possibly, a later ratification of the contract by the stevedores would suffice), and d. any difficulties about consideration moving from the stevedores were overcome. Activity 11.7 C’s consideration was the performance of the contract with B; that is to say, the unloading of the ship. It was good consideration because their performance thus provided A with the benefit of a direct obligation which they could enforce. Activity 11.8 To answer this question, you need to consider what C’s potential liability is and what defence they could use to meet this liability. They have no contract with A and thus are not liable for a breach of contract in causing the damage. Where their liability probably arises is for the tort of negligence. The issue then becomes whether or not they have a contractual defence to this action based upon the exemption clause negotiated by B. To determine this, you need to apply the criteria (noted in Section 11.3.3) set out in The Eurymedon to see if they are met. It is likely that criteria (a), (b) and (c) are met; thus the problem is concentrated on (d). The consideration in The Eurymedon was the stevedores’ performance of the contract between the carriers and the stevedores. Here, the damage occurs before the B/C contract is performed. In the circumstances, it would appear that no consideration has been provided such that a contract of immunity can arise between A and C. If there is no such contract, then C cannot raise a contractual defence of immunity. See Raymond Burke Motors Ltd v Mersey Docks & Harbour Co [1986] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 155 for an example of this problem. Activity 11.9 No feedback provided. Chapter 12 Activity 12.1 The problem that Bertha faces is that the contract for the sale of the rat poison is tainted with illegality. The first issue to determine is whether the contract is illegal as formed or illegal as performed. In this case, it appears to be illegal as formed – the statute requires that an authorisation certificate must be produced. Here, the certificate was not genuine. Re Mahmoud & Ispahani (1921) needs to be considered; in this instance, it is probably not possible to recover damages under the illegal contract. However, it may be possible to recover the reasonable value of the goods supplied: see Mohamed v Alaga & Co (A Firm) (2000). The difficulty with this approach is that it allows a contract which cannot be enforced directly to be enforced indirectly. See, for example, Awwad v Geraghty & Co (A Firm) (2000) in which Mohamed v Alaga & Co was distinguished and the claim for the reasonable value of the services was not allowed. Activity 12.2 The difference created by this variation is that Bertha is not an innocent party to the illegality in the sense that she knows there is no certificate in existence. In the circumstances, it is unlikely that she will be able to recover anything under the contract. page 277 page 278 University of London International Programmes See, for example Parkinson v College of Ambulance Ltd & Harrison (1925), Kiriri Cotton Co Ltd v Dewani (1960) and Ashmore, Benson, Pease & Co Ltd v A v Dawson Ltd (1973). Activity 12.3 In this variation of the problem, the contract is legal as formed (Bertha is registered and the authorisation certificate is validly issued) but it is illegal as performed when Bertha’s van exceeds the speed limit. In this instance, you need to apply St John Shipping Corporation v Joseph Rank Ltd (1957). In applying the criteria set out in that case, it is unlikely that Parliament, with respect to the speeding, intended to prohibit this sort of contract. As such, Bertha’s punishment lies in the criminal law and not the civil law. This result is supported by more recent cases starting with Parkingeye Ltd v Somerfield Stores Ltd (2012) and culminating in Patel v Mirza (2016) where the courts take a more flexible approach in line with the Law Commission’s earlier recommendations (The Illegallity Defence, 2009) which seeks to balance more appropriately the interests of the parties rather than to allow an easy escape from a contractual undertaking on the basis of a peripheral illegality. Activity 12.4 In Pearce v Brooks, the sexual immorality of prostitution was sufficient to render the contract to supply the brougham to be illegal. In Tinsley v Milligan, in contrast, the fact that the pair were lovers was not considered sufficiently important to argue that it affected their contractual relations. From this we can deduce that conceptions of morality (and in the case law this is invariably sexual morality) are much more relaxed than they have been in the past. What is considered ‘immoral’ changes over time. Activity 12.5 To answer this question, you need to examine the cases. There is no scientific process employed for ascertaining the nature of public policy. Chapter 13 Activity 13.1 This question involves a restraint of trade clause in a contract of employment. You need to consider, firstly, whether or not the clause seeks to protect a legitimate interest of Plod Products. Plod will need to establish this. A weakness of their position is that they may be seeking to restrain Amanda to keep her from meeting clients of theirs – in other words, it may be to keep her from competing with them. It may be that they seek to protect clients from awareness of FabuMats paper products. Alternatively, it may be possible for Amanda to argue that the real reason they seek to restrain her is to prevent a competitor from gaining strength. Neither of these is a legitimate interest on the part of Plod: see Herbert Morris Limited v Saxelby (1916). If Plod is able to establish a legitimate interest, Plod must still establish that the clause is reasonable as to subject matter, duration and area. The difficulty they have here is that not only is Amanda dealing in a different product, but the area of the restraint is very broad: see Mason v Provident Clothing & Supply Company Ltd (1913). It is likely to be unreasonable as a result. Activity 13.2 This question involves much the same issues of restraint in a contract of employment. The same approach should be followed as to whether or not the restraint is reasonable between the parties. Unlike the scenario in Activity 13.1, it probably is. MegaPharmaceuticals has a legitimate interest to protect with regard to its highly sensitive confidential information. The restraint is very long (five years) and broad (worldwide) but Dorothy will be paid for the duration of this restraint. Where this clause differs from the previous one is that there is an obvious public interest involved here. If Dorothy is at the verge of discovering a cure for a life-taking disease, it is hard to see how the public interest is served by taking her out of circulation. Contract law Feedback to activities Activity 13.3 To answer this question, you need to consider the criteria established in Nordenfelt v Maxim Nordenfelt. Taylor Skate Ltd will need to establish that they have a legitimate interest to be protected. If they succeed in this, they then need to establish that the clause goes no further than necessary in protecting this interest – that the clause is reasonable as between the parties. See, for example, Herbert Morris Ltd v Saxelby (1916). Here, Taylor Skate Ltd will encounter problems – the clause covers the entire world, it covers any business in which Taylor Skate might undertake in the future and the time period is very long. If Taylor Skate is able to establish that this is what is adequate to protect their interest, it is then open to Mr Taylor to establish that the clause is not in the interests of the public. Activity 13.4 The courts exhibit a concern about re-writing the contract between the parties when they examine it to see if it is affected by the doctrine of restraint of trade. They recognise that it is not the role of the court to re-allocate burdens assumed by a party. However, they are also concerned with situations where one party has been disadvantaged vis à vis the other as to the terms of the contract. The example Lord Reid, in Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Harper’s Garage (Stourport) Ltd, gave was where conditions have been incorporated which were not the subject of negotiation. In A Schroeder Music Publishing Co Ltd v Macaulay, the concern with regard to one, stronger, party taking an unacceptable advantage over the other is more clearly expressed. Chapter 14 Activity 14.1 This question involves a consideration of the nature of the term in question and the standard of performance required. Terms as to time are generally construed as conditions in commercial contracts (Bunge v Tradax (1981)). In this instance it is said that ‘time is of the essence’ which has been treated as a sufficient indication that the parties intended the term to be a condition (Lombard North Central v Butterworth (1987)). Additionally, liability for performance tends to be strict. The cause of the representative’s lateness is, therefore, likely to be irrelevant. For a discussion of these matters, see Union Eagle Ltd v Golden Achievement Ltd [1997] AC 514. In the circumstances, Tighte Fist plc is entitled to terminate the contract for breach. An examination answer could also include discussion of whether the police action amounted to frustration of the contract (see generally Chapter 15). A specific issue here would arise if, having set out earlier, the delay could have been avoided. If this was the case it might be easier to argue that the risk of delay was assumed by MML and consequently that the contract was not frustrated. Activity 14.2 A party is said to affirm the contract when he elects to carry on with the contract and not to terminate it because of the breach of the other party. To affirm the contract, the party must have knowledge of the facts giving rise to the right to elect. More recent cases appear to have further required that the innocent party also be aware of the right to elect: see Peyman v Lanjani (1985) and The Kanchenjunga (1990). While, in theory, the innocent party is free to decide whether to terminate the contract or to affirm it, his decision may in some circumstances be affected by the requirement that he mitigate his damages. It may be that the only way he can mitigate, or minimise, his damages is to affirm the contract. See Payzu Ltd v Saunders (1919). See Chapter 16, Section 16.6, for a full discussion of mitigation. The innocent party must act to minimise his or her damages and not increase them. page 279 page 280 University of London International Programmes Activity 14.3 It is of critical importance for the innocent party to determine the nature of the term breached. Is the term a condition, warranty or intermediate/innominate term? If the term is a warranty, the innocent party is not entitled to terminate the contract; his remedy lies in damages. If the term is a condition, or a sufficiently serious breach of an intermediate/innominate term, then the innocent party is entitled to terminate the contract. One practical aspect of this important point is that if an innocent party ‘elects’ to terminate a contract and refuses to perform his further obligations where (because of the nature of the breach) he does not have that election, he is himself in breach of contract. See Decro-Wall S.A. v International Practitioners in Marketing (1971). Activity 14.4 Yes, this statement is correct. When an appeal is heard by several judges the ratio decidendi of the case is the principle of law applied by the majority of those judges to the material facts of the case. Lords Tucker and Hodson were part of the majority but did not mention the restrictions outlined by Lord Reid. However, two is not a majority of five (the number of judges that heard the appeal in the House of Lords, Lords Keith and Morton dissented). Therefore, the ratio decidendi is to be found in the extent to which Lord Reid agreed with Lords Tucker and Hodson (i.e. including the two restrictions). As Megarry J in Hounslow explained: without Lord Reid there was no majority for the decision of the House [of Lords]. I do not think that it can be said that a majority of a bare majority is itself a majority. Activity 14.5 The danger to the claimant with such a course of action is that he will be found to have no legitimate interest, financial or otherwise, in performing. In so doing, he would be saddling the defendant with an additional burden where there was no benefit to himself, the claimant. See the speech of Lord Reid in White and Carter (Councils) Ltd v McGregor (1962). Activity 14.6 The risk in not accepting an anticipatory repudiation is that in so doing, the innocent party may forego all opportunity to claim damages in the event that the contract is later discharged by reason of his own breach or by frustration. Chapter 15 Activity 15.1 There are close links between frustration and the type of mistake known as ‘common mistake’. For example, if A and B are contracting for the hire of a concert hall, but unknown to them at the time they make the contract the hall has just burnt down, their contract will be void for common mistake. If, on the other hand, the hall burns down the day after they make their contract, it will be frustrated. Both concepts are concerned with deciding where risks and associated losses should fall when a contract is disrupted by events outside the control of either party. The question as to which applies depends solely on whether the disrupting event takes place before or after the contract is made. (See, for example, Amalgamated Investments & Property Co Ltd v John Walker & Sons Ltd (1977).) For this reason, the area of law considered in Chapter 8 involving common (i.e. shared) mistake is sometimes called the law of initial impossibility, and the area covered by the doctrine of frustration is sometimes called the law of subsequent impossibility. It should be noted that some commentators argue that the close relationship between the doctrines of common (i.e. shared) mistake and frustration should ‘not be pressed too far’. Treitel (para 19-122) notes that: The law seems to be less ready to hold that a contract is void for mistake than discharged by frustration, perhaps because it is, in general, easier to be sure of present fact than to forsee future events. Contract law Feedback to activities Activities 15.2 and 15.3 As you will have realised, these questions are intended to focus attention on why some contracts which involve the provision of services are more likely to be frustrated than others. I suspect that you are much more likely to have said that the contract for hair styling would be frustrated than the contract for servicing the car. Why should there be such a difference? This can be explained by remembering that it is important when considering frustration to identify exactly what the contract was for. It is likely that in 15.2, the contract was simply for Nathalie’s car to be serviced. In 15.3, because Nathalie is much more likely to be concerned about who styles her hair than who services her car, it may well be that the contract is for her to have her hair styled by Jamie. Once the precise nature of the contract has been identified, then the question becomes whether the alleged frustrating event has rendered performance impossible or radically different. In 15.2, if the mechanic is not specified in the contract, then the unavailability of Jamie makes no difference to Phil’s obligation to carry out the service. In 15.3, if Jamie has been specified as the stylist, then his absence will render performance on the Friday impossible and the contract will be frustrated. You might also like to consider what the position would be if all Phil’s mechanics go on strike on Friday (see The Nema (1981)). Activity 15.4 The events which have occurred in the two alternative situations (the fire at the Hall – destruction of subject-matter, and the injury to Claudio Quays – personal incapacity) are clearly of a type capable of bringing about the frustration of a contract. The question requires you to think, however, about whether on the facts there is a sufficient effect on the particular contract for it to be frustrated. In particular, you will need to think about the case of Herne Bay Steam Boat Co v Hutton (1903), outlined above. In both the situations given, some part of the contract survives the ‘frustrating’ event. The question is whether the contract has become ‘radically different’ from what was originally intended. In (a), the answer is probably that it has. Although the tour of the grounds is still possible, two thirds of the contract cannot now take place. If it is frustrated, this will mean that Aaron will not be able to sue for breach of contract in relation to the meal and the concert, but the rules relating to the effect of frustration (discussed in Section 15.4) will apply. The answer to (b) is slightly more difficult. How important an element was the concert? The most likely answer here seems to be that the contract will not be frustrated, but that Aaron will be entitled to compensation for breach of contract, in that Highplace Hall has not provided the promised concert. All the above is on the assumption that there is nothing specific in Aaron’s contract with Highplace Hall to deal with these situations. Activity 15.5 A significant difference between The Super Servant Two and Maritime National Fish is that in the Super Servant the owner of the vessels was faced with breaking one or other of two contracts. Once the Super Servant Two had sunk it was impossible for both contracts to be performed. In contrast, in Maritime National Fish the defendants could have allocated one of the licences to the plaintiffs’ boat rather than to one of their own boats. In other words, they could have performed their contract with the plaintiffs without breaking a contract with anyone else. The Court of Appeal, however, treated the two cases as being the same, arguing that in Super Servant Two the reason for the inability to perform was not the sinking of the vessel, but the decision of the owners to allocate the Super Servant One to another contract. Thus in both cases the failure to perform resulted from a decision of one of the parties. Critics of the decision in Super Servant Two argue that the cases are not identical and that in the Super Servant Two case, the owners had no real choice, in that whichever contract they used the Super Servant One for, this would involve breaking another contract. There was therefore a much stronger case for treating the Super Servant Two as a case of frustration. Note, however, that the defendants in Super Servant Two were protected by a ‘force majeure’ clause, provided that they had not been negligent. page 281 page 282 University of London International Programmes Activity 15.6 The contract is clearly frustrated when the house is destroyed. The common law rules say that obligations which have arisen up to that point generally stand. The only exception is where there is a total failure of consideration. The obligation to pay the £1,500 arose before the destruction, but it seems that there is a total failure of consideration, in that Peter has done no work on the contract. The common law would therefore allow Sabina to recover the full £1,500. Peter has no entitlement to any payment under the contract – not even for the money spent on materials. Activity 15.7 In this case, Peter has started work. Sabina cannot argue, therefore, that there is a total failure of consideration. Because Peter has done some work, albeit very little, the common law rules say that Sabina cannot now recover any of the £1,500 which she has paid. This was the situation in Whincup v Hughes (1871) where a father apprenticed his son to a watchmaker for six years for a premium of £25. When the watchmaker died after the first year the father could not recover any part of the consideration as the failure of consideration was only partial. Activity 15.8 As in Activity 15.7, there is no total failure of consideration, so the £1,500 cannot be recovered. The obligation to pay the balance, however, does not arise until the contract has been completed. Sabina is not therefore, under the common law rules, obliged to pay anything to Peter for the work done over the previous weeks. (See, for example, the case of Appleby v Myers (1867)). Note that in practice the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943 would apply to the contract between Sabina and Peter and this would affect some of the above answers. This is dealt with further in Section 15.4.2. Activity 15.9 You will remember that under the common law rules (see Activity 15.6 above) Sabina would have recovered her full £1,500 because there was a total failure of consideration. Peter would have been entitled to nothing. Under the Act (which would apply in this situation) Sabina is still entitled to recover her payment under s.1(2). The main difference is that under the Act Peter can argue that he should be allowed to retain some of the £1,500 to cover the cost of the materials which he has bought. It is up to the court to decide what it is just for him to retain. It might be relevant, for example, whether the materials are of a kind which can be used on other jobs, or whether they were specially designed for the work to be done on Sabina’s house. Activity 15.10 Under the common law, Peter could retain the full £1,500 because there is no total failure of consideration. Under the Act, the position will be the same as the answer to Activity 15.9. In other words, under s.1(2) Sabina can recover the £1,500, subject to Peter being able to retain money to cover his expenses. These may be more than the £500 spent on materials and may include expenses relating to the day’s work which has been done (for example, wages paid to others working on the house). What do you think the position would be if Peter’s expenses totalled £2,000? What is the maximum he could receive under s.1(2)? Activity 15.11 As regards the £1,500 the position is the same as in Activity 15.10. The difference here is that Peter has almost completed the work on the house when it is destroyed. Will he be entitled to claim under s.1(3) for the value of the benefit which he has supplied by doing the work? The answer, based on BP Exploration v Hunt (1979) is that he will not be able to recover anything under this section. The benefit must be looked at in the light of the frustrating event; once the house has burnt down there is no valuable benefit to Sabina. The Act has not altered the position as it stood under the common law in Contract law Feedback to activities Appleby v Myers (1867). The position would be different if, for example, the contract was to decorate two houses and only one of them was destroyed by the fire. In that situation Peter would be able to recover under s.1(3) for the benefit represented by the work done on the surviving house. Chapter 16 Activity 16.1 You need to establish, first, that there has been a breach of contract. It would appear that there has been – the government has offered for sale something that some of its civil servants suspect does not exist. The offer implies that there exist bighorn mountain sheep to hunt. The next issue is as to the measure of damages recoverable by Damian. What amount of money will put Damian in the position he would have been in if the contract had been performed? These facts offer two possibilities: loss of profits or wasted expenditure. If the sheep are very rare, loss of profits, measured by the value of the trophy heads of the sheep, could be great. The difficulty with this measure is that Damian may well have problems proving this loss (see Anglia Television v Reed (1972)). Another way of looking at this is to say that Damian’s loss of profits is too speculative because Culloden has not promised him three sheep, but the opportunity to hunt three sheep. Hence Damian is unable to prove that there is a loss of profit and is confined to claiming his expenditures (McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission (1951) and Anglia Television v Reed (1972)). Activity 16.2 Once again, you need to establish that there has been a breach of contract. This is not difficult since Emma simply refuses to perform. The great difficulty here surrounds the assessment of damages. Fun Toys Co should be able to claim for loss of profits (the case fits ideally within Robinson v Harman); the problem is, what is the amount of the loss suffered? Their toys range in price enormously – can it be said that Emma would have chosen 10,000 of the toys priced at £200 each or 10,000 of the toys priced at £1.99 each? It is suggested that either extreme is unlikely to have actually been undertaken by Emma had the contract been performed. If she was stocking her toy shops, she would not have selected entirely from one end of the price range or the other. Instead, she would likely have selected a range of toys. Consequently, it can be argued that the damages should be assessed by reference to a selection of 10,000 toys chosen in a reasonable manner. Thus the damages are set by a ‘reasonable’ amount made with reference to the likely selections of Emma. See Paula Lee Ltd v Robert Zehil [1983] 2 All ER 390 where the court faced a similar problem. Activity 16.3 The decision in Ruxley Electronics and Construction v Forsyth is not without problems and it is these problems that McKendrick refers to in this quote. McKendrick points to the recognition of a ‘loss of amenity’ as the step forward. The step backward, however, is the apparent limitations that the decision places upon the valuation of the expectation interest with regard to the claimant’s performance interest. It will often be the case that the claimant has contracted to receive something which is really only a benefit to himself and would not provide a benefit to most people. For example, the claimant, a keen gardener, may contract to have special rails affixed to the exterior of his house to hold plants. The majority of householders would not do this and would see no value in such fixtures (and may well believe that the value of the house was diminished if the rails were in place). This means that there will be no, or only a slight, increase in value if the work is performed. Consequently, the damages will be low. Can it be said that the claimant’s performance interest is properly protected in such circumstances? Activity 16.4 No feedback provided. page 283 page 284 University of London International Programmes Activity 16.5 Judges have been reluctant for some time to award damages to compensate loss which has arisen by reason of mental distress. There are a variety of possible purposes behind this refusal. One possibility, as discussed by Cockburn J in Hobbs v London and South Western Railway Co (1875) is that such loss arising from a breach of contract is beyond the contemplation of the parties to the contract. This, however, will not hold true in all cases – it is entirely possible that such loss may be contemplated in some circumstances. In cases such as the provision of a holiday the essence of the contract is the provision of pleasure/happiness; default will then inevitably, and so foreseeably, cause displeasure or unhappiness. Another possibility is raised by Mellor J in Hobbs v London and South Western Railway Co (1875): such loss, in absence of real physical inconvenience, is ‘purely sentimental’. It is not, in other words, a loss for which contract law will provide damages as a matter of principle. This is reinforced by the decision of the House of Lords in Addis v Gramophone (1909). The problem is that modern tort law will now, in some circumstances, recognise damages for loss connected to mental distress. This anomaly was noted by Lord Denning MR in Jarvis v Swan Tours Ltd (1973) and in this case it was recognised that damages for mental distress would be allowed where the sole purpose of the contract was to provide ‘entertainment and enjoyment’. This was then modified in the important case of Farley v Skinner (2001) to a requirement that the provision of pleasure (or enjoyment and happiness) is an important, but not necessarily the main, object of the contract. A third possibility is that to allow compensation for mental distress is to award damages that are close to punitive; and damages for a breach of contract are not to be punitive. A fourth possibility is that by not allowing compensation for such loss, the law denies recovery of a form of loss which may be difficult to quantify when the contract is entered into. Activity 16.6 The two cases are very similar. In both cases, a surveyor was hired by contract to survey a residential home. In both cases, the purchasers proceeded to buy the home based on the surveyor’s report. Both reports were negligently prepared and failed to reveal important aspects of the house. In Watts v Morrow the survey failed to reveal that the property needed major repairs; in Farley v Skinner, the survey failed to reveal that the house was affected by the noise of aircraft flying overhead. In Watts v Morrow, the Court of Appeal disallowed the trial judge’s award of damages for ‘distress and inconvenience’. In Farley v Skinner, however, the House of Lords allowed damages for non-pecuniary loss. How can the two cases be distinguished? One important factual difference is that in the latter case, Farley had asked the surveyor to investigate the possibility of aircraft noise and as a result of this request, the surveyor included the element within his report. In Farley v Skinner, Lord Steyn distinguished Bingham LJ’s decision in Watts v Morrow by saying that his ‘observations’ were ‘never intended to state more than broad principles’ (see paragraphs 14 and 15). Lord Steyn stated that in Watts v Morrow, the claim was for damages for inconvenience and discomfort resulting from a breach of contract: it was not a claim for damages resulting from the breach of a specific undertaking ‘to investigate a matter important for the buyer’s peace of mind’. The House of Lords, in Farley v Skinner, was also concerned that their decision was consistent with the earlier House of Lords’ decision in Ruxley Electronics v Forsyth (1995). Activity 16.7 The policy behind the rules of remoteness is one of limiting the amount of damages that can be recovered. It enables parties to, potentially, plan for any losses which may occur as a result of breach. Thus, for example, parties are able to ensure that they have adequate insurance cover for any loss which will occur. If the loss creates exceptional damages, the party responsible for this loss will want to ensure that they have extra insurance coverage. It also allows parties to determine whether or not it is in their best interests to breach a contract. The link between these rules and the cost of insurance is that the rules give, at least in theory, the insurers the ability to assess loss and hence estimate the cost of the premiums to be paid for the insurance to cover this loss. Contract law Feedback to activities Activity 16.8 In H Parsons (Livestock) v Uttley Ingham it was unlikely that the pigs would die, although it was likely that they would suffer some form of illness as a result of the way in which the pig nuts were stored (with the lid of the hopper left closed). The majority (Orr LJ and Scarman LJ) found that it was sufficient to establish liability if there was a serious possibility that breach of contract would cause physical injury to the pigs. It did not matter that the severity of the injury could not be foreseen. Scarman LJ explains that this is sufficient because it would be too much to expect the parties to have a ‘prophetic foresight as to the exact nature of the injury that does in fact arise’. The difficulty with this decision is that it is not easy to reconcile with the cases that distinguish between ‘ordinary’ and ‘special’ business profits, such as Victoria Laundry (Windsor) Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd (1949). In this case, there had to be disclosure of a particularly lucrative contract that increased the amount of the damages. It may be possible to say that such a contract could be disclosed by the plaintiff because it was within his special knowledge, but that to foresee that the breach of contract in Parsons case would cause death was not within the particular knowledge of either party. This does, however, beg the question of how the cases can be satisfactorily resolved. It is likely that the essential difference is that in Parsons case, the court was also concerned with the concept of remoteness in tort where it is well-established that it is the category of harm resulting from the tort, not the actual extent of the harm, that must be foreseeable: Hughes v Lord Advocate (1963). Lord Denning, in Parsons case, challenged the distinction between remoteness in contract and tort. However, as Lord Reid explained in The Heron II the fact that in a contractual claim the parties are not ‘strangers’ provides a convincing rationale for the different approaches and this reasoning was recently applied by the Court of Appeal in Wellesley Partners LLP v Withers LLP [2015] EWCA Civ 1146. Activity 16.9 It is difficult to provide a satisfactory answer to this question. On the one hand, it seems to be sufficient that the defendant is aware of the exceptional circumstances: see Simpson v London and North Western Railway Co (1876) and Seven Seas Properties Ltd v Al-Esa (No 2) (1993). On the other hand, there are some indications that the defendant must also agree to accept liability for this exceptional loss: see Horne v Midland Railway (1873) and Kemp v Intasun Holidays Ltd (1987). If the defendant, aware of the special circumstances, carries on with the contract is he not impliedly accepting these losses? Chapter 17 Activity 17.1 Each piece of land is considered to be unique and, for this reason, damages are not an adequate remedy for an injured party. Damages generally follow as a matter of course in the case of a breach of contract for the sale of goods because the damages awarded allow the injured party to enter the market and purchase a similar substitute. Because each piece of land is unique, no similar substitute is available. See Johnson v Agnew (1979). Yet, this is not an entirely satisfactory answer in the modern world, where parcels of land tend to be small and many residences are similar in their construction and aspect. In these cases, it may that 125 Acacia Avenue is much the same as 123 Acacia Avenue. The real problem may be that the market of similar substitutes is so small that it is impossible in practice to purchase a substitute: people tend not to sell houses in the way that they sell, for example, cars. The real reason is, therefore, the unavailability of a substitute because the market does not provide one. Another explanation tendered for the availability of specific performance for a breach of a contract for the sale of land is that the sale of land creates an equitable proprietary interest in the purchaser’s favour. Yet, the reason that this occurs is because the law will, generally, order that such a contract be specifically performed. Thus, what may really be occurring here is that an order for specific performance is made because everyone involved expects that it will be made. In such circumstances, damages are not an adequate remedy because none of the parties ever expected such a remedy. page 285 page 286 University of London International Programmes Activity 17.2 It depends on what sort of contract the contract of services was. If the services could be performed by an agent or employee of the parties, then it is hard to see that it would be tantamount to slavery. In addition, in many cases, a modern employer will be enormous and employ vast numbers of people. In such a concern, personal elements will be more removed. In the case where the individual is required to perform their services to an individual or within a small organisation, the analogy to slavery may be more appropriate. Activity 17.3 As a general rule, an injunction will not be awarded if it has the same effect as an order for specific performance. That is to say, if the terms of the injunction are so broad that they effectively compel a positive performance of the contract, the court will not grant the injunction. See Warren v Mendy (1989) and Page One Records Ltd v Britton (1968). Thus, if Albert contracts with Beatrice not to play professional hockey for anyone else besides Beatrice’s hockey team, and not to work for anyone else in any capacity, a court is unlikely to grant an injunction enforcing such a term. This is because it effectively compels Albert to work for Beatrice – something that would be most unlikely to be the subject of an order for specific performance because it is a contract for personal services. On the other hand, if Albert was simply prohibited from playing professional hockey for anyone else besides Beatrice’s team, such an injunction would likely be granted. Although he cannot play hockey for any other team, he can do anything else necessary to earn his income. This is the underlying rationale in Warner Bros v Nelson (1937). The effect, however, can be to cause Albert to continue with Beatrice’s team. Although other employment is open to him, none is as lucrative. This was the effect in Warner Bros v Nelson (1937), where the defendant Nelson (better known as Bette Davis) returned to work for Warner Bros.