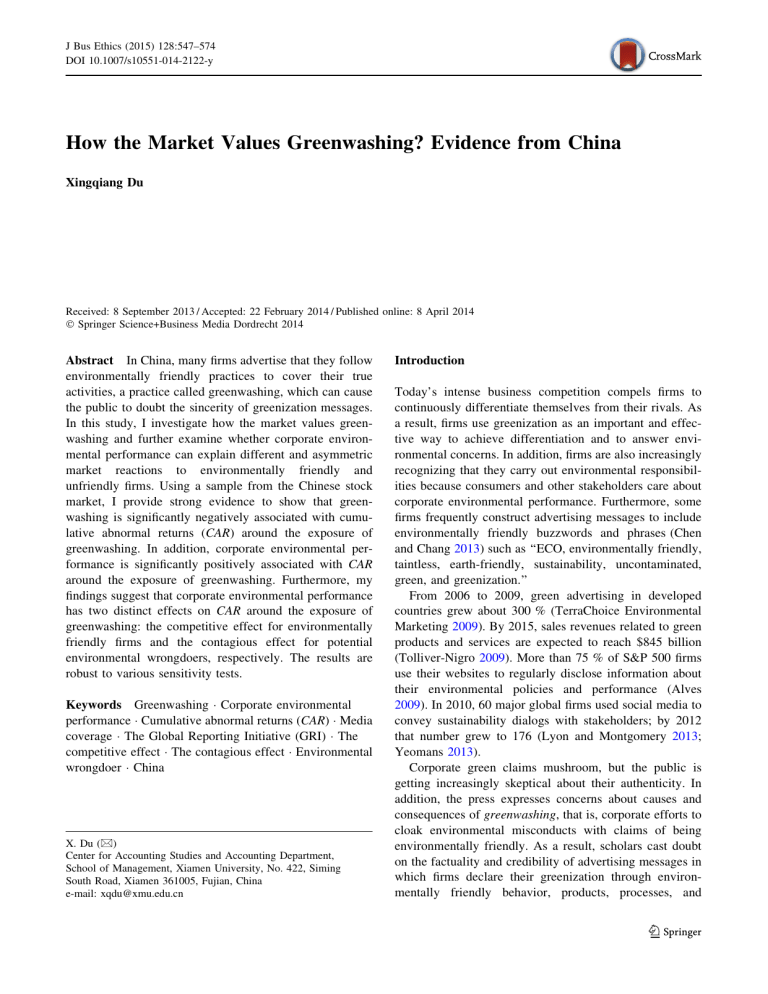

Greenwashing Valuation in China: Market Reaction & Performance

advertisement